Bova Marina Archaeological Project - Department of Archaeology

Bova Marina Archaeological Project - Department of Archaeology

Bova Marina Archaeological Project - Department of Archaeology

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong><br />

<strong>Archaeological</strong><br />

<strong>Project</strong>:<br />

Survey and<br />

Excavations<br />

at<br />

Umbro<br />

Preliminary<br />

Report,<br />

1999<br />

Season<br />

edited by John<br />

Robb<br />

with contributions by <strong>Marina</strong><br />

Ciaraldi, Lin Foxhall, Doortje<br />

Van Hove, and David Yoon<br />

<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Archaeology</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Southampton<br />

Southampton SO17 1BJ<br />

United Kingdom<br />

tel. 00-44-23-80592247<br />

fax 00-44-23-80593032<br />

email jer@soton.ac.uk

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

2<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

I would like to thank Dottoressa Elena Lattanzi, Soprintendente, and Dottoressa Emilia Andronico,<br />

Ispettrice, <strong>of</strong> the Soprintendenza Archeologica della Calabria, for their help and guidance in this research. As in<br />

past years, we are grateful to Sebastiano Stranges and to Luigi Saccà for their help, advice, and friendship; to<br />

Brian McConnell and Laura Maniscalco for archaeological advice; to our landlords, Antonino and Silvana<br />

Scordo, and to our cooks, Mariella Catalano and Annunziata Caracciolo. Mary Anne Tafuri translated the<br />

project summary and Fiona Coward helped assemble the final documentation. Finally, I would like to thank the<br />

field staff (David Yoon, Lin Foxhall, Paula Lazrus, Keri Brown and Starr Farr) and post-excavation staff and<br />

analysts (Umberto Albarella, <strong>Marina</strong> Ciaraldi, Sonia Collins, Kathryn Knowles, Doortje Van Hove, Jayne Watts,<br />

and David Williams) for their expertise, and all the crew members listed below for their hard work and<br />

enthusiasm.<br />

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the British Academy (Excavation Grant A-AN4798/APN7493<br />

Supplementary post-excavation funding), the Arts and Humanities Research Board (Research Grant AHRB/RG-<br />

AN4798/APN8592), the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Archaeology</strong>, University <strong>of</strong> Southampton, and the School <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Archaeology</strong> and Ancient History, University <strong>of</strong> Leicester.<br />

BOVA MARINA ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: CREW, 1999 SEASON<br />

Director John Robb<br />

Survey Co-Director David Yoon<br />

Survey Co-Director Lin Foxhall<br />

Field Supervisor Keri Brown<br />

Field Supervisor Paula Kay Lazrus<br />

Lab Manager Starr Farr<br />

Artist (Southampton) Kathryn Knowles<br />

Computing (Southampton) Doortje Van Hove<br />

Faunal analysis (Birmingham) Umberto Albarella<br />

Paleobotany (Birmingham) <strong>Marina</strong> Ciaraldi<br />

Cook Mariella Catalano<br />

Cook Annunziata Caracciolo<br />

Crew Members Siân Anthony<br />

Francesca Binyon<br />

Rebecca Crowson-Towers<br />

Glenn Dunaway<br />

Lauren Dumford<br />

Mark Ellis<br />

Anne Forbes<br />

Helen Forbes<br />

Janet Forbes<br />

Lucy Heaver<br />

Alex Hopson<br />

Jenny House<br />

Charlotte John<br />

Claire Rees<br />

Kathryn Simms<br />

Barney Skinner<br />

Jayne Watts<br />

Matthew Wortley<br />

Child Johanna Farr<br />

Infant Nicholas Robb

RIASSUNTO ITALIANO<br />

3<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

Nel 1999, il Progetto Archeologico <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> ha intrapreso la sua terza campagna di scavo. Le<br />

finalità principali della ricerca includevano l’attività di ricognizione di varie zone intorno al comune di <strong>Bova</strong><br />

<strong>Marina</strong> e lo scavo del sito preistorico di Umbro. Tali attività hanno avuto luogo dal 29 agosto al 26 settembre<br />

1999, con un gruppo di 25 persone. I responsabili dello scavo erano John Robb (scavo preistorico e<br />

amministrazione generale), David Yoon (ricognizione di superficie, archeologia Romana) e Lin Foxhall<br />

(ricognizione di superficie, archeologia Greca).<br />

Ricognizione di superficie<br />

Finalità e metodi. Lo scopo principale dell’attività di ricognizione era rivolto alla comprensione dello<br />

sviluppo, avvenuto nel corso della preistoria ed in epoca storica, dei modelli insediamentali legati al territorio di<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong>. Si è continuato quanto intrapreso nel 1997 e 1998. Il metodo utilizzato consiste nel systematic<br />

transect walking, mediante il quale gruppi di 4-5 persone, poste ad intervalli di 10 m., camminano su territori<br />

delimitati registrandone le caratteristiche storiche e geografiche. Nel 1999, il nostro gruppo di ricognitori ha<br />

coperto una superficie di 102 ettari, portanto l’area totale finora esplorata sistematicamente a 274 ettari. Le zone<br />

ricognite comprendono due grossi appezzamenti contigui (intorno ad Umbro e nella zona costiera di San<br />

Pasquale), e numerose porzioni di territorio sparse intorno al comune. I lavori del 1997 e 1998 si erano<br />

concentrati prevalentemente nei territori di Umbro e San Pasquale. Nel 1999, la direzione della ricerca era<br />

rivolta ad estendere la porzione di territorio ispezionato ad ambienti nuovi come colline e pianori interni.<br />

Tutti i ritrovamenti sono stati catalogati e datati per quanto possibile. E’ da tenere presente tuttavia che<br />

la sequenza cronologia della ceramica presente in questa regione è piuttosto variegata. Alcuni siti preistorici,<br />

chiaramente Neolitici, possono essere facilmente individuati grazie alle decorazioni presenti sui frammenti<br />

ceramici. Tuttavia altri periodi, quali l’Eneolitico e l’età del Bronzo, sono caratterizzati da ceramica inornata la<br />

cui identificazione si basa, per la maggior parte dei casi, sulla forma del vaso, rendendo quindi molto difficile la<br />

lettura di frammenti di piccole dimensioni. Per il periodo storico, la ceramica Greca e Romana è facilmente<br />

identificabile, tuttavia, pochi dati si posseggono sulla ceramica medievale di questa regione, forse a causa dello<br />

scarso numero di siti medievali individuati.<br />

Risultati. Fino ad oggi sono stati identificati 37 siti che variano da una piccola concentrazione di<br />

frammenti preistorici non databili a grandi villagi di epoca Greca e Romana con complessa articolazione interna.<br />

I siti sono elencati e descritti al paragrafo 2.1.4. E’ da tenere presente che tale elenco aggiorna quello<br />

precedenemente fornito in quanto alcuni siti scoperti nel passato sono stati successivamente ridatati.<br />

Nel considerare i siti in ordine cronologico, fino ad oggi, non si ha traccia di attività Paleolitica o<br />

Mesolitica. I siti di epoca Neolitica sono manifestati in una numerosa varietà che comprende terrazzi costieri,<br />

basse colline prospicenti valli fluviali e pianori interni. Non si sono evidenziati insediamenti riferibili<br />

all’Eneolitico o all’età del Bronzo (benché tracce di frequentazione di età del Bronzo sono state messe in<br />

evidenza durante gli scavi ad Umbro, cfr. più avanti); tale aspetto può essere riferibile in parte a problemi di<br />

datazione dei pezzi raccolti durante l’attività di ricognizione (vedi sopra). Le testimonianze di epoca Greca<br />

includono un grande villaggio (Mazza, cfr. più avanti), e numerosi piccoli cascinali interni (siti 18 e 33). Molti<br />

sono situati su alti terrazzi. In epoca Romana si hanno per la prima volta tracce di siti su fondo valle, che<br />

suggeriscono il passaggio a forme di agricoltura intensiva. I resti ceramici di epoca Greca e Romana mostrano<br />

due apici: uno che va dal periodo Tardo Arcaico a quello Classico (VI-V secolo a.C.) e l’altro in epoca<br />

Imperiale (III-V sec d.C.). Gli insediamenti più tardi sembrano occupare gli stessi territori, ma in minore<br />

consistenza, fino all’VIII sec. circa. L’epoca Medievale rimane oscura tuttavia nel XIX sec. si registrano di<br />

nuovo numerosi insediamenti a carattere rurale.<br />

Oltre all’attività di ricognizione sono state portate a termine numerose indagini secondarie rivolte allo<br />

studio dell’uso del territorio. Esse comprendono il riconoscimento, in ambito geologico, di quelle materie prime<br />

che possono essere state utili in epoca preistorica (da continuare nel 2000), e il GIS (Geographical Information<br />

System) computer modelling volto alla ricostruzione delle antiche dinamiche di sfruttamento del territorio in<br />

termini di esigenze relative ai diversi modelli economici preistorici.<br />

Raccolta di superficie intensiva dal sito di Mazza. Si è intrapresa una raccolta di superficie intensiva<br />

sul sito Greco di Mazza. Questo ampio villaggio ha finora restituito le uniche ceramice Greche di imporazione<br />

del periodo arcaico/classico, un possibile frammento Attico ed un possibile frammento Laconico. Le finalità<br />

della raccolta intensiva erano di determinare i limiti geografici, l’intervallo cronologico e la distribuzione<br />

spaziale interna del sito. Come prima cosa è stata stabilita una griglia di punti di riferimento su tutto il sito e<br />

sono stati collocati punti di raccolta ogni 30 metri all’interno della stessa. Si è poi proceduto alla raccolta di tutti<br />

i manufatti presenti in un’area di 10 metri quadrati per ogni punto di raccolta. I risultati potranno essere

4<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

analizzati quantitativamente. L’analisi dei dati provenienti dal sito di Mazza è ancora in corso, tuttavia alcune<br />

considerazioni sono già possibili. Il sito sembra possedere una componente Romana preponderante che si<br />

aggiunge alle evidenze di epoca Greca. Un considerevole numero di tegole di epoca Romana, insieme a tegole di<br />

epoca Greca, è stato ritrovato nella parte alta del sito. Tegole di epoca Greca sono state ritrovate in piccole<br />

quantità sul resto della zona superiore del sito e sul fianco sud-est della collina. La ceramica fine Greca<br />

comprende una considerevole quantità di tazze di fattura locale e forme a cratere. Gli affioramenti rocciosi<br />

presenti nella parte centrale del sito somigliano a quelli utilizzati nelle fondazioni di Locri Epizephyrii, e<br />

possono essere aver avuto lo stesso scopo. L’insediamento si estende con minore densità su tutto il pianoro di<br />

Mazza. Il limite meridionale del sito potrebbe essere stato, in antico, una zona industriale, come testimonia l’alta<br />

concentrazione di resti di fusione e lavorazione dei metalli. Resti di concotto e scorie di fornace sono stati<br />

raccolti e sono attualmente in corso di analisi presso l’Univesità di Leicester.<br />

Il sito di Mazza è stato abitato lungo un ampio arco cronologico durante il periodo classico. I materiali<br />

raccolti hanno indicato la presenza sia di abitazioni che di attività industrali nonché di un probabile grande<br />

edificio in prossimità della sommità del sito. Si è accertata inoltre la presenza di ceramica preistorica. Studi<br />

futuri sul sito si concentreranno sulla relazione tra lo stesso e le città di Reggio e Locri Epizephyrii e sulle<br />

problematiche relative all’occupazione indigena della zona. L’individuazione, nell’area studiata, di una serie di<br />

piccoli insediamenti rurali Greci e la considerevole distanza da qualsiasi città Greca rappresentano un<br />

interessante aspetto da analizzare nella comprensione della colonizzazione Greca e dell’occupazione di territori<br />

rurali a scopo coloniale. In genere, gli studi sulla colonizzazione Greca si sono concentrati su informazioni<br />

provenienti da siti urbani come Locri e dalle zone circostanti come Metaponto. Le datazioni antiche di alcuni siti<br />

provenienti dalla ricognizione di <strong>Bova</strong> sono sorprendenti, esse potrebbero indicare che l’insediamento Greco si<br />

sia diffuso ampiamente sul territorio coloniale nell’arco di poche generazioni, o che le popolazioni indigene si<br />

siano, almeno in parte, ellenizzate piuttosto rapidamente. La funzione di questi siti, e la loro relazione con le<br />

città Greche rimane piuttosto incerta, non si hanno inoltre informazioni circa una occupazione autoctona che sia<br />

essa contemporanea o leggermente più antica. Lo scavo di un insediamento Greco di piccole dimensioni come il<br />

sito 18 (Umbro) potrebbe fornire dati da mettere in relazione con siti urbani come Locri o ‘cascinali’ presenti su<br />

territorio Greco, allo scopo di risolvere alcune questioni.<br />

Note su siti soggetti a minaccia. Benché numerosi degli insediamenti presenti nel comune di <strong>Bova</strong><br />

<strong>Marina</strong> siano stati danneggiati dall’erosione o da processi geomorfologici, alcuni dei siti osservati sono risultati<br />

soggetti ad azioni distruttive provocate dall’uomo quali, ad esempio, l’attività edilizia. Tutti i siti minacciati sono<br />

a conoscenza della Soprintendenza; questi includono principalmente la villa Romana o cascinale di Panaghia,<br />

San Pasquale, in corso di danneggiamento da attività di costruzione e attualmente vincolato, e la villa Romana o<br />

insediamento urbano di Torrente Siderone (Amigdala), sotto la SS 106 presso la città moderna di <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong>,<br />

attualmente in corso di scavo da parte della Soprintendenza.<br />

Scavi ad Umbro<br />

Umbro appare come un complesso sito a più fasi, posto a circa 4 km nell’entroterra, in prossimità<br />

dell’antico confine tra i comuni di <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> e <strong>Bova</strong> Superiore. Scoperto nel 1990 da S. Stranges e L. Saccà,<br />

il sito è stato soggetto a ripetute attività di raccolta di superficie e, nel 1998, ad una nostra prima campagna di<br />

scavo. Lo scavo del 1998 stabilì che l’insediamento consisteva di una piccola area, alla base di un dirupo<br />

intensamente occupato durante il Neolitico, e di numerose concentrazioni di materiale, alla sommità dello stesso,<br />

probabilmente di età del Bronzo. L’insediamento Neolitico principale ha restituito una datazione al<br />

radiocarbonio che va dalla metà del VI millennio BC alla metà del V millennio BC (Stentinello). E’ inoltre<br />

attestata l’occupazione durante la facies di Diana e, probabilmente in maniera sporadica, durante l’età del Rame.<br />

Nel 1999, i lavori si sono concentrati in tre trincee: la Trincea 1, la Trincea 6 e la Trincea 7.<br />

Trincea 1: l’area Neolitica. Tale trincea fu iniziata sott<strong>of</strong>orma di sondaggio stratigrafico nel 1998 ed<br />

esteso allo scopo di comprendere la zona centrale del sito di epoca Neolitica posto alla base del dirupo. Essa<br />

comprendeva una trincea di un metro per sei metri, con una piccola estensione laterale al centro. Gli scavi sono<br />

proceduti in aree di un metro quadrato con tagli arbitrari di 10 cm.; il terreno rimosso è stato setacciato in griglie<br />

di 5 mm. Gli scavi sono proceduti fino ad arrivare alla base rocciosa nella parte meridionale della trincea; nel<br />

margine settentrionale della stessa lo scavo si è interrotto ad 1,5 m. dal piano di calpestio; il materiale antropico<br />

presente a questa pr<strong>of</strong>ondità era considerevolmente diminuito.<br />

La Trincea 1 ha restituito numerosi manufatti Neolitici, ma nessuna evidenza di strutture abitative quali<br />

capanne. E’ evidente che il sito consisteva in un’area ristretta (con uno spazio abitativo di forse 20 metri<br />

quadrati), occupata da piccoli gruppi di persone lungo il corso di diversi millenni. Tutti i manufatti erano<br />

considerevolmente frammentati. Sono stati identificati in tutto cinque strati. Lo Strato I consisteva di 5-10 cm. di<br />

terreno di superficie inquinato. Lo Strato II era formato da uno spesso livello di sedimento bruno chiaro con

5<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

abbondante presenza di materiale roccioso di crollo, probabilmente disturbato sian in epoca recente che in<br />

antico. Gli Strati I e II contenevano manufatti di tutti i periodi. Lo Strato III, di sedimento chiaro giallognolo,<br />

conteneva materiale roccioso di crollo di diverse dimensioni e una serie di lenti sabbiose apparentemente<br />

derivate dal disgregamento dei frammenti rocciosi. Il materiale ceramico presente è riferibile alle facies di<br />

Stentinello e Diana, e sembra essere riferibile a fasi di Diana con presenza di intrusioni di epoche precedenti; ciò<br />

non sorprende visto che l’area Neolitica è posta sul fondo di un bacino roccioso. Lo Strato IV consiste di un<br />

terreno più denso e compatto di colore bruno. Esso contiene prevalentemente ceramica di tipo Stentinello ed è<br />

databile al V millennio BC. In ultimo, lo Strato V è alla base dell’area scavata e contiene terreno argilloso di<br />

colore bruno scruro con presenza di ceramica Stentinello databile al VI millennio BC. I manufatti Neolitici<br />

raccolti comprendono ceramica tipica degli stili di Stentinello e Diana, alcuni esempi di ceramia Neolitica di<br />

altro tipo, quali ceramica a pittura rossa, ed alcuni probabili frammenti di epoca Eneolitica (prevalentemente<br />

dagli Strati II e III). L’industria litica era ricca di ossidiana ed includeva numerose piccole schegge e lamelle.<br />

Sono state ritrovate un’ascia in anfibolite ed una piccola riproduzione di ascia in fillite, si è attestata inoltre la<br />

presenza di numerosi ciottoli in pietra metamorfica di importazione, alcune macine e alcuni frammenti di<br />

concotto e di ocra rossa. I resti faunistici non sono ancora stati studiati, tuttavia è già evidente la preponderanza<br />

degli ovini e dei caprini, con presenza di maiale; i bovini sono scarsamente rappesentati e l’itti<strong>of</strong>auna è assente.<br />

Sono stati conservati campioni di flottazione provenienti da ogni Strato. L’analisi dei semi e dei resti vegetali<br />

carbonizzati mostrano che la coltura di alcune specie era praticata; i resti vegetali includono la veccia, il<br />

Triticum aestivum s.l., il Triticum dicoccum, e l’orzo.<br />

La Trincea 6: l’area di età del Bronzo. Nel 1999 si iniziata la pulitura del pr<strong>of</strong>ilo della rupe dal quale la<br />

ceramica dilavava dal bordo accanto alla strada che attraversa il sito. Dal fianco del dirupo è emerso un vaso<br />

intero, si è così deciso di aprire una trincea per effettuare ulteriori indagini. Nel complesso si è messa in<br />

evidenza la deposizione di un gruppo di tre vasi comprendenti due tazzine attingitoio con ansa soprelevata ed<br />

una grande olla dotata di tre anse orizzontali poste vicino all’orlo. I vasi erano affiancati e posti su uno stesso<br />

piano di calpestio distinguibile da quella di riempimento sopra per la grandezza e l’orientamento delle pietre. Si<br />

è attestata la presenza di piccoli frammenti di concotto e carbone. Subito sotto il gruppo di vasi è stato ritrovato<br />

un inusuale frammento di corno fittile. Sulla superficie del battuto si è attestata la presenza di un crollo con<br />

pietre di medie e grandi dimensioni (fino a 30 cm. ca.). Il crollo sembrava di maggiore volume ed intensità ad est<br />

del gruppo di vasi. Non è chiaramente comprensibile se ci si trovi di fronte ad un fenomeno erosivo naturale o al<br />

crollo di qualche strutture abitativa. In termini di datazione, i vasi sono chiaramente riferibile al Bronzo Antico<br />

ed il corno fittile è tipico dello stile Rodì-Tindari-Vallelunga. In stretto accordo con quanto suggerito dallo stile<br />

ceramico, la datazione al radiocarbonio, fornita da un frammento di carbone proveniente dal piano di posa del<br />

gruppo dei vasi, è riferibile al 1720-1580 BC (cal.)(intervallo 2-sigma).<br />

Il gruppo ceramico della Trincea 6 potrebbe rappresentare quanto rimane del crollo di una capanna,<br />

benchè sono scarsi i resti di frequentazione domestica all’interno della trincea e segni di strutture tipiche dell’età<br />

del Bronzo quali capanne con soglie in pietra. Una seconda possibilità potrebbe essere rituale: i vasi potrebbero<br />

rappresentare una qualche deposizione rituale idiosincratica. Una terza possibilità è rappresentata da una<br />

eventuale deposizione funeraria. Confronti effettuati con contesti della Sicilia orientale hanno messo in evidenza<br />

la presenza ricorrente, durante il Bronzo Antico, di sepolture situate lungo margini scoscesi di pietra calcarea o<br />

di altro tipo, così come appare essere Umbro. Si tratta in genere di piccole camere artificiali raramente più<br />

grandi dei di 2 metri di diametro e 1,5 metri di altezza, spesso raggiungibili attraverso uno stretto passaggio. In<br />

diversi casi, inoltre, gli archeologi hanno messo in luce aree livellate o piattaforme che contenevano gruppi di<br />

vasi rappresentanti il corredo funerario volontariamente posto all’esterno della tomba piuttosto che all’interno di<br />

essa (es. Santa Febronia, Maniscalco, 1996).<br />

Trincea 7. La Trincea 7 consiste di un piccolo (un metro per un metro) pozzetto scavato<br />

immediatamento al di sotto del margine del dirupo, lungo il limite meridionale del bacino che racchiude il sito<br />

Neolitico. Si è sperato di recuperare in questa area materiale di epoca preistorica. Tuttavia, pochi resti sono stati<br />

ritrovati, e ad una pr<strong>of</strong>ondità di 1,5 metri lo scavo della trincea è risultato impraticabile.<br />

Sondaggi di Scavo a San Pasquale<br />

Nel 1999 è stato sondato il sito Neolitico di San Pasqule, situato su di un basso terrazzo lungo il<br />

margine orientale della valle di S. Pasquale. Si è sperato di verificare la presenza di un “villaggio” Neolitico, per<br />

il quale la zona <strong>of</strong>friva le caratteritiche tipiche. Due pozzetti di un metro per un metro sono stati scavati in una<br />

zona situata lungo il margine occidentale del sito, dove in superficie emergevano frammenti di ceramica<br />

preistorica. I risultati si sono rivelati piuttosto scoraggianti. Entrambi i sondaggi hanno evidenziato che non<br />

esistevano depositi archeologici al di sotto dello strato superficiale; il terreno si è rapidamente trasformato in uno<br />

strato di sabbia sterile. Appare evidente che il materiale ceramico di epoca preistorica proviente dal “sito” deriva

6<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

dal dilavamento della collina posta a nord-est di esso, in parte coltivata ed in parte coperta da una fitta macchia<br />

mediterranea. Indagini future potrebbero concentrarsi sull’individuazione del sito originario.<br />

Indagini Future<br />

La campagna di scavo del 1999 ha aperto la strada a nuove prospettive di ricerca.<br />

Ricognizione. Nelle campagne future, speriamo di poter continuare ed incrementare l’attività di<br />

ricognizione, che stà fornendo nuove informazioni sull’utilizzazione del territorio. Allo stesso tempo speriamo di<br />

indagare due problemi metodologici.<br />

Ricognizioni di altura a <strong>Bova</strong> Superiore. Sia le indagini storiche che la nostra ricostruzione informatica<br />

al GIS hanno dimostrato l’importanza, in diversi periodi, degli insediamenti d’altura in zone interne. Un<br />

sondaggio basato solo sull’indagine di zone costiere sarebbe inevitabilmente incompleto e non potrebbe fornire<br />

l’intera consistenza e l’evoluzione delle dinamiche insediamentali del territorio di <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong>; questo potrebbe<br />

spiegare inoltre la scarsa presenza di siti di età del Ferro o di epoca Medievale. Nel continuare i sondaggi a <strong>Bova</strong><br />

<strong>Marina</strong>, speriamo inoltre di poterci estendere al comune di <strong>Bova</strong> Superiore e di completare il quadro delle<br />

conoscenze sulle strategie insediamentali antiche, investigando un completa serie di diversi ambienti.<br />

Sondaggi di scavo in siti di superficie non datati. Sono inoltre stati ritrovati una serie di siti non datati<br />

che potrebbero rappresentare i nosti “periodi mancanti”. L’unico modo per indagare gli stessi consiste nello<br />

scavo programmato di sondaggi di un metro quadrato, in grado di fornire materiale datante meno danneggiato,<br />

campioni per datazioni assolute al radiocarbonio, ed informazioni sullo stato di conservazione del sito.<br />

Nell’immediato futuro ci auguriamo di poter sondare due aree entro un raggio di 200-300 metri dallo scavo di<br />

Umbro: Limaca, dove una concentrazione di materiale potrebbe rappresentare una successiva occupazione di età<br />

del Bronzo (si è ottenuto un permesso nel 1999 che è però arrivato troppo tardi perché si potesse praticamente<br />

procedere allo scavo); e una zona a circa 200 metri a sud-ovest di Umbro dove due concentrazioni di frammenti<br />

di epoca preistorica sono visibili in superficie. Quest’ultima potrebbe rappresentare un villaggio Neolitico<br />

all’aperto; si considera critica una eventuale verifica che possa permettere di comprendere le dinamiche<br />

insediamentali del territorio di Umbro.<br />

Lo scavo ad Umbro: Ci auguriamo di poter continuare gli scavi sia del sito Neolitico che di quello di<br />

età del Bronzo dell’area di Umbro. Gli scavi saranno limitati nelle finalità e si concentreranno sulla<br />

individuazione della base della stratigrafia, sulla verifica dell’esistenza di eventuali frequentazioni pre-<br />

Neolitiche e sul recupero di un maggior numero di campioni per analisi, per esempio, di tipo paleobotanico.<br />

Nell’area di età del Bronzo Antico (Trincea 6), speriamo di poter verificare la natura del gruppo ceramico,<br />

ovvero se formi o meno parte di una sepoltura.<br />

Altre attività di scavo: Come già accennato, l’area di Umbro è ricca di piccole concentrazioni di<br />

materiale archeologico. In alcune di esse ci auguriamo di poter effettuare dei sondaggi esplorativi (vedi sopra).<br />

Un ulteriore sito da indagare è rappresentato dal piccolo insediamento Greco posto a circa 200 meri a sud di<br />

Umbro. La presenza di piccoli insediamenti interni di epoca greca, come il cascinale di Umbro, si sono rivelati<br />

una scoperta sorprendente e potrebbero risultare di notevole importanza nella comprensione del processo di<br />

colonizzazione di questa zona.<br />

Note sull’organizzazione della documentazione<br />

La documentazione relativa alla campagna del 1999 risulta divisa in due parti. La prima parte (questo<br />

volume) consiste in un rapporto descrittivo illustrato. La seconda parte è formata dalla compilazione di dati di<br />

appendice per il progetto e per gli archivi della Soprintendenza. Sono inclusi cataloghi degli oggetti suddivisi<br />

per provenienza e categoria di oggetto, disegni di tutti i frammenti diagnostici, il giornale di scavo e schede<br />

standard per siti, unità stratigrafiche e frammenti ceramici.

CONTENTS<br />

7<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

Riassunto Italiano 3<br />

1. Introduction 8<br />

2. Field Survey and Landscape Studies 9<br />

2.1. Field Survey (David Yoon) 9<br />

2.2. Intensive collections at Mazza (Lin Foxhall) 19<br />

2.3. Geological reconnaissance 20<br />

2.4. GIS analysis <strong>of</strong> land use (Doortje Van Hove) 21<br />

3. The Excavations at Umbro 24<br />

3.1. Introduction: previous work, goals and methods for this season 24<br />

3.2. Description <strong>of</strong> 1999 Trenches 25<br />

3.3. Other areas explored 30<br />

4. Umbro Excavations: Description <strong>of</strong> Finds 32<br />

4.1. Ceramics 32<br />

4.2. Lithics 34<br />

4.3. Other Artifacts: daub, worked shell and bone, ground and polished stone, and ochre 35<br />

4.4. Faunal Remains and Human Remains 37<br />

4.5. Paleobotanical Remains (<strong>Marina</strong> Ciaraldi) 38<br />

5. Test Excavations at San Pasquale 41<br />

6. Conclusions and Future Research Directions 43<br />

6.1. Umbro: dating, stratigraphy, and site function 43<br />

6.2. The Landscape <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> from Neolithic through Recent Times 43<br />

6.3. Future Work 43<br />

Bibliography 45<br />

Figures and Tables 47<br />

NOTE ON THE ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> the 1999 field season is presented in two parts. This report, which comprises the first part,<br />

presents a self-contained, synthetic description <strong>of</strong> the survey, excavations and finds. The second part presents<br />

detailed records <strong>of</strong> various kinds for archive purposes: catalogs <strong>of</strong> finds inventoried within each artifact bag and<br />

listed by kind <strong>of</strong> artifact, ceramic inventories and drawings <strong>of</strong> all diagnostic sherds, the excavation diary, and so<br />

on.

1999 was the third year <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bova</strong><br />

<strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong>. In 1997, a small<br />

crew <strong>of</strong> 5 Southampton students led by John Robb<br />

carried out field survey in the comune <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bova</strong><br />

<strong>Marina</strong>. In 1998, a larger crew <strong>of</strong> 10 Southampton<br />

students and about 5 staff, directed by John Robb<br />

and David Yoon, surveyed further areas, and<br />

excavated numerous exploratory trenches at the<br />

Neolithic site <strong>of</strong> Umbro.<br />

These campaigns are described in the<br />

1997 and 1998 preliminary reports (Robb 1997;<br />

1998), which also detail the circumstances in which<br />

fieldwork was carried out and the geography,<br />

geology, and archaeology <strong>of</strong> the region. To avoid<br />

repetition, these topics will not be extensively<br />

described here.<br />

In 1999, we had the largest field season to<br />

date, with 18 (10 from Southampton and 8 from<br />

Leicester) crew members and 10 staff or<br />

contributing specialists, directed by John Robb,<br />

David Yoon and Lin Foxhall. We worked in <strong>Bova</strong><br />

<strong>Marina</strong> from August 29 through September 25. The<br />

season had three major goals:<br />

(1) to carry out extensive excavations in<br />

the Neolithic area <strong>of</strong> Umbro, with particular<br />

attention to economic and contextual information<br />

about the Neolithic habitation there;<br />

1. INTRODUCTION<br />

8<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

(2) to carry out test excavations in the<br />

Neolithic site <strong>of</strong> San Pasquale, in order to assess its<br />

potential for large-scale excavations;<br />

(3) to continue the field survey, extending<br />

it to new areas, particularly inland; the overall<br />

survey goal is to understand the evolution <strong>of</strong><br />

settlement in the area <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> throughout<br />

both prehistoric and historic times.<br />

In addition, we aimed to carry out a number <strong>of</strong><br />

complementary minor projects such as GIS<br />

environmental modelling, geological raw materials<br />

survey, and intensive gridded collection at the<br />

Greek site <strong>of</strong> Mazza with the goal <strong>of</strong> clarifying its<br />

internal organization and evolution.<br />

The 1999 field season ran smoothly, with<br />

no major hitches, and these goals were<br />

accomplished. In some cases the results were<br />

disappointing, as in the San Pasquale test<br />

excavations, but in other cases surprises emerged,<br />

as in the Bronze Age ritual deposition discovered at<br />

Umbro. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this report is to describe the<br />

methods and results <strong>of</strong> this field season in detail,<br />

and to interpret their significance for both the<br />

archaeology <strong>of</strong> the region and the development <strong>of</strong><br />

future fieldwork.

2.1. Field Survey (David Yoon)<br />

2.1.1. Background<br />

The overall goal <strong>of</strong> the BMAP field survey<br />

is to understand how people used different areas <strong>of</strong><br />

the Calabrian landscape for various purposes such<br />

as habitation, farming, herding, foraging,<br />

specialized production, and so on, in all periods<br />

from the Paleolithic through modern times. As<br />

detailed in previous reports, the local landscape is<br />

both very rugged, with very little level ground, and<br />

highly varied, with very diverse environments<br />

located close to each other. The contrast between<br />

narrow coastal strips and valley bottoms and<br />

mountainous interior is especially marked.<br />

Historically, there appear to have been oscillations<br />

between coast-oriented settlement such as in<br />

Roman times and inland settlement as in medieval<br />

times. As also detailed previously, a number <strong>of</strong><br />

landscape features make archaeological field survey<br />

challenging and its results sometimes problematic.<br />

These include heavy erosion on slopes and deep<br />

alluviation on valley bottoms, intensive and<br />

destructive historical land use, the rapid<br />

proliferation <strong>of</strong> fenced-in non-surveyable areas, and<br />

the fact that pottery fragments from many periods<br />

are not particularly diagnostic.<br />

In 1997, a strategy <strong>of</strong> visiting previously<br />

known sites and systematically walking a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

small areas provided an efficient introduction to the<br />

local archaeological sequence and also provided<br />

useful experience for adapting survey methods to<br />

local conditions. In 1998, the same survey strategy<br />

was continued, together with an effort to assemble<br />

larger contiguous tracts <strong>of</strong> systematically surveyed<br />

territory, especially around Umbro and San<br />

Pasquale.<br />

The work in 1997 and 1998 raised a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> questions which we hoped to address in<br />

1999. Some periods (Paleolithic, Copper Age, Iron<br />

Age, Medieval) were absent or nearly absent from<br />

our collections. Does this represent an actual<br />

scarcity <strong>of</strong> occupation in those periods or did it<br />

instead reflect poor recognition <strong>of</strong> artifacts by us or<br />

poor choice <strong>of</strong> survey areas? The recognition <strong>of</strong><br />

several small Greek sites <strong>of</strong> early date raised many<br />

questions about the process <strong>of</strong> Greek colonization<br />

in the region, and how pre-existing native<br />

communities interacted with the Greek presence.<br />

The differences observed so far in Greek and<br />

Roman site locations (Greek sites on hills, Roman<br />

sites in valleys), despite similarities <strong>of</strong> technology<br />

and social organization, should be associated with<br />

2. FIELD SURVEY AND LANDSCAPE STUDIES<br />

9<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

important differences in land use and economic<br />

organization.<br />

In the 1999 survey, co-directed by David<br />

Yoon and Lin Foxhall, we therefore sought in 1999<br />

to improve the quality <strong>of</strong> our evidence as it relates<br />

to these questions, by:<br />

• doing more survey <strong>of</strong> hilltops and highelevation<br />

areas<br />

• continuing to build up larger blocks <strong>of</strong><br />

completely surveyed territory<br />

• obtaining more detailed information about the<br />

locations and internal organization <strong>of</strong> Greek<br />

and Roman sites<br />

Survey <strong>of</strong> hilltops and high-elevation areas was<br />

intended to improve the representation <strong>of</strong> these in<br />

our sample, and particularly to see whether the<br />

missing time periods would be located in these<br />

places. Larger contiguous blocks <strong>of</strong> surveyed<br />

territory enable better understanding <strong>of</strong> the relative<br />

placement <strong>of</strong> contemporary sites, which is<br />

important for interpreting the organization <strong>of</strong> local<br />

communities <strong>of</strong> any period. Because Greek and<br />

Roman village sites are relatively large and<br />

complex, they are difficult to interpret through<br />

ordinary fieldwalking methods. The controlled<br />

surface collections at Deri (Site 9, San Pasquale) in<br />

1997 provided some information on the internal<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> one large Roman site. We decided in<br />

1999 to do similar controlled surface collections at<br />

Mazza, the largest known Greek site in the study<br />

area, to get comparable information for that period.<br />

2.1.2. Procedures<br />

The methods used in 1999 were essentially<br />

the same as in previous years. We worked in crews<br />

consisting either <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the co-directors and<br />

three to four students or (more rarely) both codirectors<br />

and six to eight students. All survey was<br />

carried out within defined “areas,” zones .1-2 ha in<br />

size whose boundaries, location, and geology and<br />

land use were recorded systematically, All areas<br />

without previously identified sites were walked in<br />

parallel transects with the crew members spaced 10<br />

meters apart (in some locations, where it was<br />

difficult to maintain this interval due to steep slopes<br />

or thick vegetation, we were able only to<br />

approximate it). Previously identified sites were<br />

collected more intensively, using either a systematic<br />

grid <strong>of</strong> 10 m 2 collection areas or nonsystematic<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> any artifacts observed on the site. In<br />

1997 and 1998 some areas with previously reported

sites were surveyed less systematically, but we<br />

attempted for the sake <strong>of</strong> comparability to use<br />

systematic methods for all areas in 1999.<br />

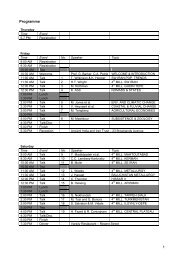

The 1999 survey was conducted from 29<br />

August to 17 September. This included 2 days <strong>of</strong><br />

fieldwalking with two crews, 5 days <strong>of</strong> fieldwalking<br />

with one crew, 0.5 days <strong>of</strong> fieldwalking with a<br />

double-size crew, and 3.5 days <strong>of</strong> intensive surface<br />

collection with a large crew at Mazza. In all this<br />

represents 73 person-days <strong>of</strong> work, <strong>of</strong> which 45.5<br />

were used for fieldwalking and 27.5 for intensive<br />

collection at Mazza.<br />

The fieldwalking survey in 1999 covered a<br />

total <strong>of</strong> 102.0 ha, <strong>of</strong> which 5.8 ha had been<br />

surveyed in previous years and 96.2 ha were new.<br />

In all, excluding repeat visits to the same area, we<br />

have surveyed a total <strong>of</strong> 274.5 ha in the three years<br />

<strong>of</strong> the project so far. We defined 53 new survey<br />

areas in 1999, numbered 102 through 154. Some <strong>of</strong><br />

these (Areas 102, 103, 130, 131, 133, and 134) may<br />

overlap to some degree with areas from previous<br />

years. All new areas were surveyed using<br />

systematic transect walking except Areas 150<br />

through 154, which were areas at Mazza surveyed<br />

using a systematic grid <strong>of</strong> collection areas instead<br />

(see below).<br />

The survey work <strong>of</strong> the past three years<br />

has been concentrated in several locations. The two<br />

largest clusters are around Umbro (Figure 1, Figure<br />

2) and in the lower part <strong>of</strong> the San Pasquale valley.<br />

In each <strong>of</strong> these places numerous survey areas make<br />

up almost a square kilometer <strong>of</strong> contiguous<br />

coverage. Most <strong>of</strong> this was done in 1997 and 1998,<br />

but a few areas were added at Umbro in 1999,<br />

especially to the northeast. A third cluster <strong>of</strong> survey<br />

areas is located in the middle part <strong>of</strong> the San<br />

Pasquale valley, but in this case it consists <strong>of</strong><br />

several disconnected fragments, due to difficulties<br />

<strong>of</strong> access. A few <strong>of</strong> these areas were done in 1997<br />

and 1998, but most were done in 1999. Several<br />

smaller clusters have been selected to represent<br />

particular types <strong>of</strong> location: Mazza (Figure 3) and<br />

Capo Crisafi for coastal hills (1997, plus the<br />

controlled collections in 1999), M. Rotonda and M.<br />

Vunemo for high inland hills (both newly done in<br />

1999), and M. Silipone to compare the valley <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Torrente Sideroni with the San Pasquale valley<br />

(mostly done in 1998, plus two small areas in<br />

1999). Several small isolated patches occur as well,<br />

mostly to investigate known sites or to survey small<br />

patches <strong>of</strong> accessible land near the modern town <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong>; a few <strong>of</strong> these have been done each<br />

year.<br />

10<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

2.1.3. Ceramics and chronology<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the biggest problems for survey in<br />

the past was the lack <strong>of</strong> a well-defined local<br />

ceramic sequence which would be used to date sites<br />

found on survey. During 1999, considerable<br />

progress was made at identification <strong>of</strong> the pottery<br />

from the survey. We were able to work several days<br />

in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Reggio di<br />

Calabria before the field season, restudying some <strong>of</strong><br />

our 1997 and 1998 collections and also comparing<br />

them to excavated materials from the Roman site at<br />

San Pasquale (Deri). We are grateful to Dssa.<br />

Emilia Andronico and the staff <strong>of</strong> the museum for<br />

their assistance with this work.<br />

Based on this research, a new provisional<br />

ceramic classification was set up before the field<br />

season (and modified slightly during the field<br />

season), which was used for classification <strong>of</strong> the<br />

1999 survey finds. This system will require<br />

additional modification as our knowledge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

regional pottery improves, but it has improved our<br />

ability to recognize chronological information in<br />

our surface collections, by enabling us to associate<br />

the better-known wares with changes in the local<br />

productions.<br />

Of the remaining problems in this ceramic<br />

chronology, the most important is the prehistoric<br />

period. Prehistoric pottery can usually be<br />

distinguished from that <strong>of</strong> later periods, but that is<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten the limit <strong>of</strong> our resolution so far. The standard<br />

chronological types for prehistoric pottery in<br />

southern Italy, based on whole vessels from burials,<br />

make use <strong>of</strong> both form and decoration. For some<br />

periods, such as the Neolithic, surface decoration is<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten useful, but after the Neolithic, most vessels<br />

were probably undecorated and vessel form is the<br />

most distinctive criterion. Unfortunately, the small<br />

eroded fragments in our surface collections have<br />

little evidence for either, but especially for vessel<br />

form. Traces <strong>of</strong> impressed decoration sometimes<br />

survive, making the Neolithic period more visible<br />

than other portions <strong>of</strong> prehistory, while post-<br />

Neolithic periods are far less easy to identify. It is<br />

likely that some very broad divisions should be<br />

possible on the basis <strong>of</strong> fabric and surface<br />

treatment, although these are not likely to be as<br />

precise as the existing categories. Of our prehistoric<br />

sites, some have been dated by chance survival <strong>of</strong> a<br />

diagnostic element or two, some have a suggested<br />

date based on a subjective assessment <strong>of</strong> similarity<br />

to the excavated assemblage from Umbro, and<br />

some remain undated.<br />

The chronology <strong>of</strong> the Greek period is<br />

founded on the black-gloss finewares which,<br />

although mostly <strong>of</strong> regional manufacture, reflect<br />

stylistic trends common throughout the Greek<br />

world. These are associated with reddish brown

sandy coarseware, beige plainwares, large and<br />

coarse storage jars, and sandy beige transport<br />

amphoras <strong>of</strong> Greek-derived form. Ro<strong>of</strong> tile appears<br />

for the first time in the Greek period as well,<br />

predominantly in a sandy, light-colored fabric and<br />

taking the form <strong>of</strong> flat tile (tegula) with wide<br />

flanges and cover tile (imbrex) with a flat top and<br />

angular sides.<br />

The assemblages <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Hellenistic/Republican and early Imperial periods<br />

remain ill-defined, because very few imports <strong>of</strong><br />

well-dated types have been found to confirm dates<br />

in this range. The assemblages <strong>of</strong> local<br />

commonwares seem to show a gradual changing<br />

mixture, however, <strong>of</strong> the sandy brown cooking ware<br />

and fine plainware <strong>of</strong> the Greek period and the<br />

gritty light-colored wares <strong>of</strong> the later Roman<br />

period. An orange variant <strong>of</strong> the Greek cooking<br />

ware is likely to belong to this period.<br />

The late Roman period is well defined by<br />

the presence <strong>of</strong> imports, including African Red Slip<br />

ware, plainwares, and amphoras from North Africa,<br />

as well as small quantities <strong>of</strong> Late Roman C ware<br />

and Late Roman amphoras from the eastern<br />

Mediterranean. The types and quantities found in<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> suggest a peak <strong>of</strong> imports between the<br />

late 2nd or early 3rd and late 5th centuries AD. The<br />

associated local wares include light-colored<br />

coarseware and amphoras tempered with wellsorted<br />

grit (around 1 mm in size) and light-colored<br />

fine plainware. Roman ro<strong>of</strong> tile, compared to<br />

Greek, tends to be in grittier fabrics and to have<br />

slightly different forms, with thinner flanges on the<br />

tegulae and a curved shape to the imbrices.<br />

Probably at the later end <strong>of</strong> the sequence <strong>of</strong> Roman<br />

coarsewares is a brown fabric tempered with<br />

abundant grit, mica, and sometimes chunks <strong>of</strong><br />

schist. The precision <strong>of</strong> dates within the Roman<br />

period is limited so far, however, because the sites<br />

appear in most cases to have been occupied for<br />

quite long periods, several centuries in the case <strong>of</strong><br />

Sites 9 and 22.<br />

There is a large, ill-defined gap between<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the Roman period and the recent<br />

assemblage associated with farmhouses <strong>of</strong> the 19th<br />

and 20th centuries. It is not clear how much <strong>of</strong> this<br />

results from an actual scarcity <strong>of</strong> settlement and<br />

how much from poor recognition <strong>of</strong> the pottery <strong>of</strong><br />

those periods. Judging from the few available<br />

reports, from the 9th to 11th centuries, ceramic<br />

assemblages in Calabria seem to consist <strong>of</strong> coarse<br />

cooking wares, semi-fine or finely sandy wares with<br />

red painted decoration, and Italian-Byzantine<br />

amphoras. All <strong>of</strong> these are continuations from Late<br />

Antiquity, although the details may vary. In<br />

addition, occasional lead-glazed pottery begins by<br />

the 9th century, either with a thick green glaze or<br />

11<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

with a sparse glaze overall but large patches and<br />

streaks <strong>of</strong> thick glaze. In the 11th century the first<br />

tin-glazed wares with green and brown decoration<br />

appear. Very little has been published on late<br />

medieval pottery in Calabria, but based on other<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> southern Italy one would expect tin-glazed<br />

protomaiolica decorated in various colors, sgraffito<br />

wares, lead-glazed cooking wares, and unglazed<br />

semi-fine wares with red painted decoration<br />

(narrower, finer painting than on the early medieval<br />

version). Until a better sense <strong>of</strong> the local<br />

productions can be obtained, it may be possible for<br />

early medieval pottery to be mistaken for late<br />

ancient, and for late medieval pottery to be<br />

mistaken for early modern.<br />

There is a clearly modern assemblage,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten associated with abandoned farmhouses,<br />

including large beige water jars, red casseroles with<br />

a very thin green glaze, beige plates, bowls, and<br />

jars with a thin greenish or brownish glaze,<br />

earthenwares with decorated opaque glazes, and<br />

hard, well-fired, usually dark red curved ro<strong>of</strong> tiles.<br />

This assemblage probably dates to the late 19th and<br />

20th centuries. Some <strong>of</strong> our collections resemble<br />

this assemblage in some respects but also differ<br />

substantially. These collections may be associated<br />

with visible ruins, as at Site 10 (Torre Crisafi), but<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten are not. Characteristics include red casseroles<br />

decorated with white slip under a yellow glaze, jars<br />

in a hard, finely granular reddish fabric, and curved<br />

ro<strong>of</strong> tile in a s<strong>of</strong>t brown fabric containing large<br />

chunks <strong>of</strong> gneiss and schist. In some cases, such as<br />

Torre Crisafi, there is good reason to assign this<br />

material to the early modern period, but in most<br />

cases there is no evidence for an absolute date, and<br />

some <strong>of</strong> it may extend back to the late Middle<br />

Ages. Comparison with better-dated assemblages<br />

from elsewhere will therefore be important for<br />

establishing the chronological ranges <strong>of</strong> these types.<br />

2.1.4. Results to date: sites found<br />

We assigned eight new site numbers in<br />

1999, bringing the total to 37 (Figure 1). We<br />

recognize, however, that not all <strong>of</strong> these site<br />

numbers represent comparable entities. They range<br />

from a few scattered artifacts in a field all the way<br />

to a large and dense concentration <strong>of</strong> finds such as<br />

Mazza (Site 12). The issue is further complicated<br />

by the different levels <strong>of</strong> material culture typical <strong>of</strong><br />

different periods: a thin scatter <strong>of</strong> artifacts which<br />

would define a full-fledged prehistoric site might be<br />

less than the general <strong>of</strong>f-site “background” scatter<br />

<strong>of</strong> artifacts in areas <strong>of</strong> intensive Roman land use.<br />

As a first approximation toward a more<br />

useful classification, we have divided them into two<br />

categories: "sites", meaning locations where the

artifact concentration is sufficiently obvious that<br />

one can define its extent, and "scatters", meaning<br />

areas or locations where artifacts are more<br />

abundant than usual, but not abundant enough to<br />

form a definite concentration.<br />

The list here reviews all 37 locations to<br />

which we have given site numbers so far. Note that,<br />

for the sites defined in 1997 and 1998, it<br />

incorporates updated information where available<br />

from revisiting the location or restudying the<br />

collections. Some sites have been redated or<br />

reinterpreted, and hence this information<br />

supersedes earlier descriptions.<br />

Site 1 (Canturatta A, Area 2). Site, ca. 1<br />

ha? Neolithic. This site, reported to us by S.<br />

Stranges and L. Saccà , is located on the eastern<br />

edge <strong>of</strong> the S. Pasquale valley, on the slopes just<br />

below a steep ridge. It is in a field with some vines<br />

and almond trees, and evidence for more extensive<br />

vine cultivation in the past. The 1997 collections<br />

from this area produced one Impressed Ware or<br />

Stentinello sherd, and Stranges reports having<br />

found several Stentinello sherds there. Test<br />

excavations in 1999, described in detail elsewhere<br />

in this report, failed to demonstrate the existence <strong>of</strong><br />

significant subsurface archaeological deposits.<br />

Site 2 (Canturatta B, Areas 2, 50). Site, ca.<br />

2 ha? Roman. This site is located on the mild slopes<br />

on the eastern edge <strong>of</strong> the lower S. Pasquale valley,<br />

just below a steep ridge. Abundant fragments <strong>of</strong><br />

Roman commonwares and tile were found,<br />

especially in the northeastern corner <strong>of</strong> Area 50.<br />

The collections need to be reexamined, but no<br />

clearly datable diagnostics have been noted so far.<br />

Site 3 (Pisciotta A, Area 5). Site, ca. 0.5<br />

ha. Bronze Age. This site consists <strong>of</strong> a scatter <strong>of</strong><br />

impasto sherds found on a steep rocky hillside at<br />

the eastern edge <strong>of</strong> the S. Pasquale valley. The<br />

artifacts appear to be associated with a particular<br />

level near the base <strong>of</strong> the hillside, are highly<br />

localized, and include fairly large pieces <strong>of</strong> vessels.<br />

This implies that the site is located on the slope<br />

itself rather than consisting <strong>of</strong> slopewash from<br />

above. The pottery includes pieces with carination,<br />

high raised strap handles, or horizontal lug handles,<br />

suggesting a Bronze Age date.<br />

Site 4 (Pisciotta B, Area 6). Scatter.<br />

Roman? This area is located near the southern end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the top <strong>of</strong> the ridge overlooking the eastern side<br />

<strong>of</strong> the S. Pasquale valley. A scatter <strong>of</strong> ancient tile<br />

and pottery fragments, possibly Roman, was found<br />

in this area, in contrast to adjoining areas, but the<br />

quantity <strong>of</strong> material found is small enough that it<br />

may be background scatter associated with a site<br />

elsewhere.<br />

12<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

Site 5 (Pisciotta C, Area 7). Site, 0.4 ha.<br />

Bronze Age? This site, reported to us by S.<br />

Stranges and L. Saccà, is located on a rocky hill<br />

along the ridge to the east <strong>of</strong> the S. Pasquale valley.<br />

A scatter <strong>of</strong> prehistoric pottery was found on the<br />

peak <strong>of</strong> the hill and just below it on the western<br />

side. Most <strong>of</strong> this pottery was nondiagnostic, but<br />

one rim would be compatible with a Bronze Age or<br />

Iron Age date, and previous collections described<br />

by Saccà would support a Bronze Age date. If so,<br />

like Site 3, it may be worth further investigation to<br />

see how similar it is to recently discovered BA<br />

deposits at the base <strong>of</strong> a rocky bank at Umbro (see<br />

below).<br />

Site 6 (Deri A, Areas 9, 10, 83). Site, ca. 4<br />

ha. Roman. This site is just above the east bank <strong>of</strong><br />

the Fiumara di S. Pasquale near the sea. A rescue<br />

excavation in advance <strong>of</strong> partially completed<br />

highway construction several years ago found a<br />

Late Roman synagogue as well as other structures<br />

and some burials (Costamagna 1991). The principal<br />

data from our survey consist <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> 15<br />

irregularly placed 10 m 2 collection units in the field<br />

just north <strong>of</strong> the intended highway bridge (Area 10)<br />

as well as collections from transect-walking in<br />

adjoining areas. In addition, a few diagnostic pieces<br />

were selected from the disturbed area around the<br />

construction. There is at least a thin scatter <strong>of</strong><br />

artifactual material throughout the entire field, but a<br />

dense concentration only in the southwestern half<br />

<strong>of</strong> Area 10. The pottery appears to cover a time<br />

range at least from the 1st century BC to the 5th<br />

century AD. Dated sherds include two rims <strong>of</strong> a<br />

form resembling Campana A Lamboglia 36 with a<br />

grayish brown slip (2nd to 1st century BC), a<br />

fragment <strong>of</strong> a thin-walled cup decorated with<br />

barbotine dots (late 1st century BC to early 2nd<br />

century AD), Eastern Sigillata B Hayes 60 (80-150<br />

AD), African Red Slip (ARS) Hayes 8A (75/90-<br />

180/200 AD), ARS cookware Hayes 23B (150-220<br />

AD), African amphora Keay 27B (300-450 AD),<br />

ARS Hayes 50B (350-400+ AD), ARS Hayes 67<br />

(350-450 AD), and ARS Hayes 84 small (440-500<br />

AD). Additional finds include Campanian (black<br />

sand) amphora, Late Roman Amphora 2, and a<br />

marble mosaic tessera.<br />

Site 7 (Deri B, Areas 9, 84). Site, ca. 1 ha.<br />

Prehistoric. This site, which overlaps the northern<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the Roman site at Deri, is a sparse scatter <strong>of</strong><br />

prehistoric artifacts in a cultivated field in the<br />

bottom <strong>of</strong> the S. Pasquale valley. The finds include<br />

a small amount <strong>of</strong> prehistoric impasto, and one<br />

fragment <strong>of</strong> obsidian. There was also a piece <strong>of</strong><br />

worked flint nearby in Area 10. The only diagnostic<br />

artifact was a horizontal lug handle. This site is<br />

noteworthy for being a prehistoric site in a valley<br />

bottom location, suggesting that landscape<br />

alteration in the valleys has not been so total as to

preclude all possibility <strong>of</strong> finding sites. It may be<br />

the one erroneously called “Torre Varata” in Tinè<br />

(1992).<br />

Site 8 (Pisciotta D, Area 13). Scatter.<br />

Historic. This is a sparse scatter <strong>of</strong> pottery found in<br />

a small area about 30 meters in diameter on a<br />

recently reforested slope. The artifacts are not<br />

prehistoric, but have yet to be reexamined to<br />

determine their date.<br />

Site 9 (Umbro A, Area 16; Figure 2)).<br />

Site, < 0.1 ha. Neolithic, Copper Age?, Bronze<br />

Age, Roman. This site has been the principal focus<br />

<strong>of</strong> the excavations in 1998 and 1999 and is<br />

discussed in detail in elsewhere in this report. To<br />

summarize briefly, this site, previously explored by<br />

S. Stranges and briefly examined by Tinè (1992),<br />

is located on a plateau near the border between<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> and <strong>Bova</strong> Superiore, where the<br />

bedrock <strong>of</strong> calcareous sandstone projects out to<br />

form steep cliffs. At the foot <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the cliffs was<br />

found a dense scatter <strong>of</strong> Neolithic pottery and<br />

obsidian; this area was excavated in both 1998 and<br />

1999. Two areas on top <strong>of</strong> this same cliff where<br />

undated prehistoric pottery had been found on the<br />

surface were also excavated, one in 1998 yielding a<br />

poorly dated assemblage, possibly post-Neolithic,<br />

and the other in 1999 yielding an assemblage<br />

including parts <strong>of</strong> some Early Bronze Age whole<br />

vessels. Abundant small pieces <strong>of</strong> human bone were<br />

found partway up the cliff; although associated with<br />

Neolithic pottery and obsidian, these were<br />

subsequently dated by radiocarbon to the late<br />

Roman period. The presence <strong>of</strong> Roman burials at<br />

this location is somewhat enigmatic, because the<br />

nearest site found as yet which may possibly have<br />

Roman occupation is Site 33, about half a kilometer<br />

away. However, Area 130, located about 250<br />

meters to the southwest, yielded one fragment <strong>of</strong><br />

Italian sigillata, so there is some other evidence for<br />

Roman activity in the area.<br />

Site 10 (Torre Crisafi, Area 26). Site, ca.<br />

0.5 ha. Modern. This site occupies the peak <strong>of</strong> the<br />

promontory above Capo S. Giovanni. The central<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the peak is now occupied by the shrine <strong>of</strong><br />

the Madonna del Mare. However, around the edges<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peak and around the ruined coastal<br />

watchtower, abundant pottery and tile fragments<br />

were collected. Although this site was originally<br />

considered both Classical and medieval in date,<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the collection was reexamined in 1999 and<br />

the site has been redated. It appears to be modern,<br />

but probably earlier than the assemblage associated<br />

with recent abandoned farms in <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong>. It<br />

might be useful to compare this assemblage with<br />

late medieval pottery as well. It is worth noting that<br />

the tower at this point dates to the 16 th -17 th<br />

centuries.<br />

13<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

Site 11 (Cimitero, Areas 28, 29). Site?<br />

Historic. A large amount <strong>of</strong> pottery was found on<br />

the slope west <strong>of</strong> the modern Cimitero S. Pietro,<br />

overlooking the modern town <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong>. A<br />

small amount was also found at the top <strong>of</strong> the hill.<br />

The artifacts are not prehistoric, but have yet to be<br />

reexamined to determine their date.<br />

Site 12 (Mazza, Areas 30-37, 102, 103,<br />

150-153; Figure 3)). Site, ca. 8 ha. This site,<br />

reported to us by S. Stranges and L. Saccà and the<br />

location several years ago <strong>of</strong> a small test excavation<br />

by L. Costamagna for the Soprintendenza<br />

Archeologica della Calabria, was partially surveyed<br />

in 1997. At that time the presence <strong>of</strong> a substantial<br />

Greek site, presumably a village, was confirmed.<br />

Restudy <strong>of</strong> the collections in 1999 showed the<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> prehistoric and Late Roman pottery in<br />

addition to a wide range <strong>of</strong> Greek pottery, from<br />

early Archaic to Hellenistic. Greek pottery included<br />

the base <strong>of</strong> an early Archaic cup with bichrome<br />

decoration, numerous cup and krater pieces <strong>of</strong> the<br />

6th to 5th centuries BC, Italiote transport amphoras<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 5th to 4th centuries BC, and a possible<br />

Corinthian “frying pan” <strong>of</strong> the Hellenistic period.<br />

Late Roman material identified in the 1997<br />

collections includes ARS Hayes 91C/D (6th to 7th<br />

century AD), ARS Hayes 105 (late 6th to 7th<br />

century AD), and Late Roman C Hayes 3C/D (late<br />

5th century AD). In 1999, we did a small amount <strong>of</strong><br />

new fieldwalking (Areas 102 and 103) and<br />

conducted intensive surface collections on a regular<br />

grid over all the parts <strong>of</strong> the site to which we could<br />

obtain access. These intensive collections are<br />

reported in detail below. It should also be noted<br />

that the site probably continues to the east, and<br />

possibly to the north as well, but that access to that<br />

area was blocked by fences in both 1997 and 1999.<br />

Site 13 (Pisciotta E, Area 47). Site, ca. 0.5<br />

ha. Roman. This site was reported to us as a<br />

possible Roman kiln site by S. Stranges and L.<br />

Saccà . It is located in a small ravine cut into a<br />

slope on the eastern edge <strong>of</strong> the S. Pasquale valley.<br />

On the slope north <strong>of</strong> the ravine, abundant tile and<br />

commonware sherds were found. A drystone wall<br />

foundation, possibly <strong>of</strong> a small rectangular<br />

building, was observed in the eroding hillside. Two<br />

rounded depressions in the bottom <strong>of</strong> the ravine<br />

may be the features suggested to have been kilns.<br />

Full reexamination <strong>of</strong> the collection remains to be<br />

done, but a brief inspection showed a small but<br />

diverse assemblage <strong>of</strong> Roman (and possibly also<br />

Greek or medieval) commonwares, including a<br />

fragment <strong>of</strong> African amphora. Surface collections<br />

contain no evidence <strong>of</strong> pottery production such as<br />

misfired wasters or a predominance <strong>of</strong> one or two<br />

fabrics. Thus, it may be best interpreted as a typical<br />

small Roman site, probably a farm. The round

features <strong>of</strong> unknown date and function may or may<br />

not be associated.<br />

Site 14 (Panaghia A, Areas 51, 55). Site,<br />

ca. 0.5 ha? Roman. This site, reported to us by S.<br />

Stranges and L. Saccà , is located on the western<br />

side <strong>of</strong> the middle part <strong>of</strong> the San Pasquale valley.<br />

Collections from Area 51, done in 1997, include a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> Roman commonwares and tile, probably<br />

predominantly early imperial, and a fragment <strong>of</strong> a<br />

fineware with a bright orange slip (possibly either<br />

ARS chiara A or Eastern Sigillata B). When the<br />

site was revisited in 1998, a trench had been dug in<br />

the site, apparently for construction, which had cut<br />

through a Roman structure with tile ro<strong>of</strong>, brick<br />

walls, and opus signinum (cocciopesto) floor before<br />

being halted. In the disturbed ground around this<br />

trench we collected more Roman artifacts,<br />

including the base <strong>of</strong> an ARS bowl (chiara D<br />

fabric) with feather-rouletting on the interior, dating<br />

to the 5th or 6th century AD. We made a series <strong>of</strong><br />

controlled collections in the field extending north<br />

<strong>of</strong> this trench (Area 55). For the most part these<br />

collections produced little or no Roman material,<br />

except for a low-density scatter about 100 meters<br />

away from the structure. Thus, the site is apparently<br />

fairly small, probably a single farm. The area to the<br />

east is inaccessible, being fenced-<strong>of</strong>f orange groves,<br />

but it may be worthwhile to investigate how far the<br />

artifact scatter extends to the southwest.<br />

Site 15 (Agrillei, Area 52). Site, < 1 ha.<br />

Prehistoric. This site is located on a small<br />

promontory at the southern end <strong>of</strong> the Agrillei ridge<br />

near the border between <strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> and Palizzi<br />

<strong>Marina</strong>, overlooking the sea. The presence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

prehistoric site here was reported to us by L. Saccà.<br />

Collections in 1997 and 1998 produced a<br />

significant quantity <strong>of</strong> prehistoric impasto sherds,<br />

mostly from the southern face <strong>of</strong> the hill, just below<br />

the crest. None <strong>of</strong> the fragments appear to be useful<br />

chronological indicators. The presence <strong>of</strong> a flat area<br />

at the summit and buried terrace walls eroding out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the slope suggests modern earth-moving, so the<br />

finds may not be in their original context. Several<br />

probably Greek or Roman sherds indicate the<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> a Greek or Roman component as well,<br />

but the quantity is not enough to rule out their being<br />

background scatter.<br />

Site 16 (Umbro B, Area 58). Site, ca. 0.4<br />

ha. Prehistoric. This site is on a hill about 150<br />

meters north <strong>of</strong> Site 9 at Umbro. The main<br />

concentration <strong>of</strong> artifacts is on a small saddle <strong>of</strong><br />

land along the top <strong>of</strong> the hill and along the upper<br />

northern face <strong>of</strong> the hill. Collections in 1998<br />

produced a large quantity <strong>of</strong> prehistoric impasto;<br />

the assemblage differs somewhat from the Neolithic<br />

pottery at Site 9, particularly in the presence <strong>of</strong> a<br />

slip on many fragments, but no obvious<br />

14<br />

<strong>Bova</strong> <strong>Marina</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Project</strong> 1999<br />

chronological diagnostics were found. It is likely<br />

that the assemblage is post-Neolithic, but<br />

excavation may be needed to determine a more<br />

specific date.<br />

Site 17 (Limaca, Area 66). Scatter.<br />

Prehistoric. On the northern slope <strong>of</strong> a rounded hill<br />

east <strong>of</strong> Umbro we collected one impasto sherd and<br />

one piece <strong>of</strong> worked flint. The quantity is too small<br />

to demonstrate the existence <strong>of</strong> any concentration<br />

that could be called a site, but ground visibility was<br />

poor, so it may be that additional items were<br />

missed.<br />

Site 18 (Umbro C, Areas 24, 68, 130).<br />

Site, 0.2 ha. Greek. The main concentration <strong>of</strong> finds<br />

is in Area 24, which is the sloping top <strong>of</strong> a small<br />

rocky outcrop. A less dense scatter <strong>of</strong> artifacts<br />

occurs also in the adjoining areas. The finds include<br />

black-gloss pottery, probably <strong>of</strong> the late 6th to early<br />

5th century BC, as well as Greek commonwares<br />

and tile. The small but fairly dense sherd scatter<br />

suggests something like a small single farm site. A<br />

few Roman sherds have been found in nearby areas<br />

as well; it is not clear whether these relate to reuse<br />

<strong>of</strong> this location or to some other, as yet unidentified<br />

site.<br />

Site 19 (Penitenzeria, Area 72). Scatter.<br />

Prehistoric?, Greek. This area is a large, gently<br />

sloping field on the large plateau extending west<br />

and south from the rock outcrops at Umbro. A<br />

small scatter <strong>of</strong> artifacts was collected from the<br />

southern edge <strong>of</strong> Area 72. This included four<br />

probable fragments <strong>of</strong> prehistoric impasto, all<br />

nondiagnostic, as well as a fragment <strong>of</strong> Greek<br />

black-gloss and some Greek or Roman<br />

commonwares. This location should be revisited to<br />

assess whether there is a significant artifact<br />

concentration, and if so to determine its extent and<br />

obtain more evidence <strong>of</strong> its date.<br />

Site 20 (Buccisa A, Area 76). Scatter.<br />

Greek/Roman? This area is an olive grove on the<br />

south face <strong>of</strong> M. Buccisa. At the southern edge, a<br />

dense concentration <strong>of</strong> Greek or Roman tile was<br />

found. No definitely ancient pottery was found in<br />

association with this tile. Thus, it is uncertain<br />

whether this tile scatter is the result <strong>of</strong> an ancient<br />

structure in this location or <strong>of</strong> reuse for building<br />

modern terrace walls. Even in the latter case,<br />

however, it is likely that the site the tile came from<br />

should be nearby.<br />

Site 21 (Buccisa B, Area 79). Scatter.<br />

Prehistoric. In a small, level area at the foot <strong>of</strong> the<br />

southwest end <strong>of</strong> M. Buccisa, a small scatter <strong>of</strong><br />

pottery was found in a cultivated field. Most was<br />

modern, but three fragments <strong>of</strong> prehistoric impasto,<br />

all nondiagnostic, were also present. This is unusual<br />

for such a small area, and although this small

quantity could be background scatter, it is also<br />

possible that there is a prehistoric site in this<br />

location or nearby.<br />

Site 22 (Sideroni/Amigdala, Areas 88, 89).<br />

Site, > 1.5 ha. Prehistoric?, Roman, Medieval. The<br />

site is located on the eastern bank <strong>of</strong> the Torrente<br />

Sideroni, amidst the built-up area <strong>of</strong> modern <strong>Bova</strong><br />