resuscitation in small animals - Maravet

resuscitation in small animals - Maravet

resuscitation in small animals - Maravet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

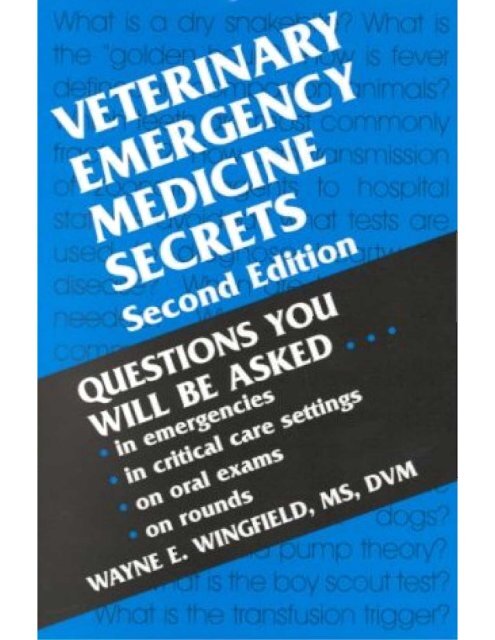

Publisher: HANLEY & BELFUS, INC.<br />

Medical Publishers<br />

An Impr<strong>in</strong>t of Elsevier<br />

210 South 13th Street<br />

Philadelphia, PA 19107<br />

(215) 546-7293; 800-962-1892<br />

FAX (215) 790-9330<br />

Web site: http://www.hanleyandbelfus.com<br />

Note to the reader: Although the <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> this book has been carefully reviewed for correctness<br />

of dosage and <strong>in</strong>dications, neither the authors nor the editor nor the publisher can<br />

accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. Neither the publisher<br />

nor the editor makes any warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material conta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

here<strong>in</strong>. Before prescrib<strong>in</strong>g any drug, the reader must review the manufacturer's current<br />

product <strong>in</strong>formation (package <strong>in</strong>serts) for accepted <strong>in</strong>dications, absolute dosage recommendations,<br />

and other <strong>in</strong>formation pert<strong>in</strong>ent to the safe and effective use of the product described.<br />

Library of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g-<strong>in</strong>-Publication Data<br />

Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e Secrets / ledited bYI Wayne E. W<strong>in</strong>gfield.<br />

p.cm - (The secrets series)<br />

Includes bibliographical references and <strong>in</strong>dex (p.).<br />

ISBN-I3: 978-1-56053-421-1 - ISBN-!O: 1-56053-421-4 Calk.paper)<br />

I. Dogs-Wounds and <strong>in</strong>juries-Treatment-Exam<strong>in</strong>ations. questions. etc. 2.<br />

Cats-Wounds and <strong>in</strong>juries-Treatment-Exam<strong>in</strong>ations. questions, etc. 3.<br />

Dogs-Diseases-Treatment-Exam<strong>in</strong>ations. questions, etc. 4.<br />

Cats-Diseases-Treatment-Exam<strong>in</strong>ations, questions, etc. 5. Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

emergencies-Exam<strong>in</strong>ations, questions, etc. 6. First aid for <strong>animals</strong>-Exam<strong>in</strong>ations,<br />

questions, etc. I. W<strong>in</strong>gfield, Wayne E. II. Series.<br />

SF991 .Y4752000<br />

636. T0896025--dc2I 00-061420<br />

ISBN-I3: 978-1-56053-421-1<br />

ISBN-!O: 1-56053-421-4<br />

VETERINARY EMERGENCY MEDICINE SECRETS. second EdItion<br />

© 200 I by Hanley & Belfus. Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,<br />

reused, republished, or transmitted <strong>in</strong> any form. or stored <strong>in</strong> a data base or retrieval system,<br />

without written permission of the publisher.<br />

Pennissions may be sought directly from Elsevier's Health Sciences Rights<br />

Department <strong>in</strong> Philadelphia, PA. USA: phone: (+1) 215 239 3804, fax: (+1) 2152393805,<br />

e-mail: healthpennissions@elsevier.com. You may also complete your request on-l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com). by select<strong>in</strong>g 'Customer Support'<br />

and then 'Obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Permissions'.<br />

Last digit is the pr<strong>in</strong>t number: 9 8 7 6 5

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Jonathan A. Abbott, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology)<br />

Associate Professor, Department of Small Animal Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia-Maryland Regional<br />

College of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Virg<strong>in</strong>ia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg,<br />

Virg<strong>in</strong>ia<br />

Andrew W. Beardow, BVMS, MRCVS, DACVIM (Cardiology)<br />

General Manager, Cardiopet, Little Falls, New Jersey<br />

Jean M. Betkowski, VMD, DACVIM<br />

Assistant Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Professor, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Tufts University, School of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e, North Grafton, Massachusetts<br />

Terri E. Bonenberger, DVM<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Fellow, University of California-Davis, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medical Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Davis,<br />

California<br />

Derek P. Burney, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e)<br />

Gulf Coast Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Specialists, Houston, Texas<br />

Leslie Carter, CVT, VTS (ECC), MS<br />

Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Supervisor, Critical Care Unit, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Colorado State University,<br />

College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Dianne Dunn<strong>in</strong>g, DVM, MS, DACVS<br />

Assistant Professor of Small Animal Surgery, Department of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Louisiana<br />

State University, School ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Baton Rouge, Louisiana<br />

Teresa Dye DVM<br />

Surgery Resident, Wheat Ridge Animal Hospital, Wheat Ridge, Colorado<br />

Denise A. EUiott, BVSc, DACVIM<br />

Hill's Fellow <strong>in</strong> Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Nutrition, Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of California<br />

Davis, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medical Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Davis, California<br />

Tam Garland, DVM, PhD<br />

Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Texas A & M University, College of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e, College Station, Texas<br />

Kristi L. Graham, DVM, MS<br />

Staff Internist, Indianapolis Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Specialists, PC, Indianapolis, Indiana<br />

Timothy B. Hackett, DVM, MS, DACVECC<br />

Assistant Professor, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Peter W. Hellyer, DVM, MS, DACVA<br />

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University,<br />

College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Orna Kristal, DVM<br />

Resident, Oncology, Department ofCl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Tufts University, School ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

North Grafton, Massachusetts<br />

Michael Steven Lagutchik, DVM, MS, DACVECC<br />

United States Army Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Corps, Fort Sam Houston, Texas<br />

India F. Lane, DVM, MS, DACVIM<br />

Assistant Professor and Internist, Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Department of Small Animal Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences,<br />

The University ofTennessee, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Knoxville, Tennessee<br />

xi

xii Contributors<br />

Michael R. Lapp<strong>in</strong>, DVM, PhD, DACVIM<br />

Professor, Small Animal Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State<br />

University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Stephanie J. Lifton, OVM, DACVIM (Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e)<br />

Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e Consultant, Antech Diagnostics, San Jose, California<br />

Catriona M. MacPhail, DVM<br />

Surgical Fellow, Small Animal Surgery and OncologylDepartment of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado<br />

State University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Dennis Macy, DVM, MS, DACVIM<br />

Professor, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Steven L. Marks, BVSc, MS, MRCVS, DACVIM<br />

Assistant Professor, Department ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Louisiana State University, School of<br />

Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Baton Rouge, Louisiana<br />

L<strong>in</strong>da G. Mart<strong>in</strong>, DVM, MS, DACVECC<br />

Staff Veter<strong>in</strong>arian, Emergency and Critical Care Medic<strong>in</strong>e Section, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Referral Center of<br />

Colorado, Englewood, Colorado<br />

Cary L. Matwichuk, DVM, MVSc<br />

Post Doctoral Research Associate, Department of Small Animal Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, The University of<br />

Tennessee, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Knoxville, Tennessee<br />

Elisa M. Mazzaferro, MS, DVM<br />

Resident, Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Critical Care, Department of Critical Care, Colorado State<br />

University, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

John J. McDonnell, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Neurology)<br />

Assistant Professor, Neurology and Neurosurgery, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Thfts University,<br />

School ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Foster Hospital for Small Animals, North Grafton, Massachusetts<br />

J. Michael McFarland, DVM<br />

Technical Services Veter<strong>in</strong>arian, Companion Animal Division, Pfizer Animal Health, Exton,<br />

Pennsylvania<br />

Chris McReynolds, DVM, DACVIM<br />

Internist, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Specialists of Southern Colorado, Colorado Spr<strong>in</strong>gs, Colorado<br />

Lynda Melendez, DVM, MS, DACVIM<br />

Department of Small Animal Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Boren Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Oklahoma State<br />

University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Stillwater, Oklahoma<br />

Steven Mensack, VMD<br />

Director, Emergency and Critical Care Services, VCA West 86th Street Hospital, Indianapolis, Indiana<br />

Eric P. Monnet, DVM, MS, PhD, DACVS, DECVS<br />

Assistant Professor, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Colleen Murray, DVM<br />

Dallas, Texas<br />

Maura G. O'Brien, DVM, DACVS<br />

Head, Surgery Department, VCA West Los Angeles Animal Hospital, Los Angeles, California<br />

Gregory K. Ogilvie, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Oncology)<br />

Professor and Head of Medical Oncology and the Medical Oncology Research Laboratory, Animal<br />

Cancer Center, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University, College of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado

Donald A. Ostwald, Jr., DVM<br />

Wheat Ridge, Colorado<br />

Therese O'Toole, DVM<br />

Natick, Massachusetts<br />

Contributors xiii<br />

Cynthia C. Powell, DVM, MS, DACVO<br />

Assistant Professor, Ophthalmology, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University,<br />

College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Col1<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Lisa Leigh Powell, DVM, DACVECC<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Specialist, Small Animal ICU, University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Sa<strong>in</strong>t<br />

Paul, M<strong>in</strong>nesota<br />

Adam J. Reiss, DVM<br />

Emergency and Critical Care Veter<strong>in</strong>arian, Denver Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Specialists, Wheat Ridge, Colorado<br />

Elizabeth Ann Rozanski, DVM<br />

Assistant Professor, Section of Critical Care, Tufts University, School of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e, North<br />

Grafton, Massachusetts<br />

Howard B. Seim m, DVM, DACVS<br />

Professor and Chief, Small Animal Surgery, Colorado State University, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e Teach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Hospital, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Carolyn M. Selavka, MS, VMD<br />

Department of Surgery, Rowley Memorial Animal Hospital, Spr<strong>in</strong>gfield, Massachusetts<br />

Cynthia Stubbs, DVM, MS, DACVIM<br />

Cobb Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Marietta, Georgia<br />

Nancy Taylor, DVM<br />

Chief of Staff, Puget Sound Pet Pavilion, Gig Harbor, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

Andrew J. Triolo, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Internal Medic<strong>in</strong>e)<br />

Intern Director, Staff Internist, VCA West Los Angeles Animal Hospital, Los Angeles, California<br />

Ann E. Wagner, DVM, MS, DACVA<br />

Associate Professor, Department ofCl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences, Colorado State University, College ofVeter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Biomedical Sciences, Fort Col1<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

J. Michael Walters, DVM<br />

Park Cities Animal Hospital, Dallas, Texas<br />

Ronald Walton, DVM, MS, DACVIM, DACVECC<br />

Chief, Experimental Surgery, US Army Institute of Surgical Research, Fort Sam Houston, Texas<br />

Suzanne G. W<strong>in</strong>gfield, RVT, VTS (ECC)<br />

Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Pathology, Colorado State University, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Fort<br />

Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Wayne E. W<strong>in</strong>gfield, MS, DVM, DACVECC, DACVS<br />

Professor and Chief, Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e and Critical Care, Department of Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Sciences and<br />

Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Teach<strong>in</strong>g Hospital, Colorado State University, College of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Medic<strong>in</strong>e and<br />

Biomedical Sciences, Fort Coll<strong>in</strong>s, Colorado<br />

Lori A. Wise, DVM, MS, DACVIM<br />

Staff Internist, Denver Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Specialists, Wheat Ridge, Colorado

DEDICATION<br />

To my residents <strong>in</strong> emergency and critical care medic<strong>in</strong>e I offer this contribution<br />

to your education. Let your questions never end. Let your curiosity to f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

new answers propel you to elim<strong>in</strong>ate anecdotal "facts" from the practice of medic<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

Seek the truth and you will f<strong>in</strong>d it-and don't forget to publish your results!<br />

To the nurses I have had the pleasure of work<strong>in</strong>g with-Maura, Leslie, Patti,<br />

Sandy, Cheryl, Suzanne, Scott, Rene, Coy, Christ<strong>in</strong>e, Mart<strong>in</strong>, Stephanie, Ellen,<br />

Brenda, Beth, Jean<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e, Heather B., Kimberly P., June, Sue, Terri, Melba, Vicki,<br />

Lee Ann, and Sooz-thank you for your knowledge and wonderful patient skills.<br />

To my wife, Sooz, thanks for be<strong>in</strong>g here and for teach<strong>in</strong>g me patience. To<br />

our dogs, Sage (a medical nightmare) and Loretta (a happy Sheltie) thanks for<br />

your companionship. In the mounta<strong>in</strong>s of Colorado there will always be wonderful<br />

memories of days past and years to come.<br />

WEW

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION<br />

In this second edition of Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e Secrets we have updated the chapters<br />

from the first edition and added some new chapters based on new <strong>in</strong>terests and <strong>in</strong>volvement<br />

of emergency veter<strong>in</strong>arians. This question-and-answer format cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be a useful means of<br />

offer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation about veter<strong>in</strong>ary emergency medic<strong>in</strong>e. The stimuli for new questions and<br />

answers have come from readers of the first edition, students <strong>in</strong> the arena ofemergency and critical<br />

care medic<strong>in</strong>e, veter<strong>in</strong>ary nurses and technicians, and chapter authors. We all encounter new<br />

and excit<strong>in</strong>g experiences each and every day of our professional lives. Too often we need that<br />

quick answer to one of these new experiences. Undoubtedly this process will cont<strong>in</strong>ue as our specialty<br />

matures and expands. We are <strong>in</strong> the most excit<strong>in</strong>g specialty of veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e. Where<br />

else could we be afforded the opportunity to practice emergency medic<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>in</strong>ternal medic<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

surgery, anesthesia, neurology, cardiology, and other specialties? The beauty of our specialty is<br />

the advantage of see<strong>in</strong>g a response to treatment <strong>in</strong> a short time. These are excit<strong>in</strong>g times-live<br />

them, learn from them, and publish your results!<br />

Special thanks are extended to Mr. Bill Lamsback of Hanley and Belfus. He cont<strong>in</strong>ues to<br />

produce excit<strong>in</strong>g products for the veter<strong>in</strong>ary and human medical professions. Without our dedicated,<br />

experienced, and productive authors, Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e Secrets would not<br />

be available. Thank you to all authors for the time and expertise dedicated to this endeavor.<br />

xv

I. Life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g Emergencies<br />

Section Editor: Waljne E. W<strong>in</strong>gfield, M.S., D.V.M.<br />

1. DECISION MAKING IN VETERINARY<br />

EMERGENCY MEDICINE<br />

Waljne E. W<strong>in</strong>gfield, M.S., D.v.M.<br />

1. Why is emergency medic<strong>in</strong>e so important <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e?<br />

Emergencies constitute up to 60% of hospital admissions <strong>in</strong> veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

2. How does the approach to an emergency patient differ from conventional hospital admission?<br />

A comprehensive medical history and physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation, rout<strong>in</strong>e laboratory diagnostic<br />

studies, specialized diagnostic techniques, and formulation of lists of written rule-outs often take<br />

too long. Typically, the veter<strong>in</strong>arian is faced with m<strong>in</strong>imal history and a cursory physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

that hones <strong>in</strong> on obvious <strong>in</strong>juries or illnesses and <strong>in</strong>stitutes therapy as the animal is exam<strong>in</strong>ed.<br />

3. What is an emergency?<br />

An emergency is any illness or <strong>in</strong>jury perceived by the person present<strong>in</strong>g the animal to the<br />

veter<strong>in</strong>arian as requir<strong>in</strong>g immediate attention. Not every "emergency" is life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g; thus,<br />

the most important question is, "What is the threat to the animal's life?" In an emergency, conventional<br />

approaches to diagnosis and treatment do not ensure an expeditious answer to this<br />

question. Significant time constra<strong>in</strong>ts may impede the use ofconventional methods.<br />

4. How is the life-threatened animal identified?<br />

Three components are necessary to recognize quickly the life-threatened animal:<br />

1. Primary compla<strong>in</strong>t<br />

2. Complete and accurate set of vital signs<br />

3. Opportunity to visualize, auscultate, and touch the animal.<br />

5. Why is the primary compla<strong>in</strong>t so important?<br />

The primary compla<strong>in</strong>t helps the veter<strong>in</strong>arian to categorize the general type of problem (e.g.,<br />

respiratory, cardiovascular, traumatic, ur<strong>in</strong>ary).<br />

6. Why are vital signs so important <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial management ofan emergency?<br />

Vital signs represent the first objective data available to the veter<strong>in</strong>arian. Along with the primary<br />

compla<strong>in</strong>t, they are used to triage the vast majority of life-threatened patients.<br />

7. What vital signs are most important <strong>in</strong> the emergency patient?<br />

• Respiratory rate and character<br />

• Heart rate and rhythm<br />

• Pulse rate, rhythm, and character<br />

• Accurate core body temperature<br />

• Color of mucous membranes and capillary refill time

2 Decision Mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

8. What are the determ<strong>in</strong>ants of normal vital signs?<br />

o Age<br />

o Animal's behavior<br />

o Underly<strong>in</strong>g physical condition<br />

o Medical problems (e.g., hypertension, <strong>in</strong>creased cerebrosp<strong>in</strong>al fluid pressure)<br />

o Current medications<br />

For example, a well-conditioned, athletic, hunt<strong>in</strong>g breed dog brought to the hospital after<br />

susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a major trauma may arrive with a pulse rate of 100 beats/m<strong>in</strong>. The dog probably is <strong>in</strong><br />

shock and may have significant blood loss because the normal pulse is likely 40-50 beats/<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ute.<br />

9. Why do I need to visualize, auscultate, and touch the animal?<br />

In many <strong>in</strong>stances, these measures help to identify the threat to life (e.g., is it the upper<br />

airway, lower airway, or circulation?). Touch<strong>in</strong>g the animal helps to identify areas of tenderness.<br />

Touch<strong>in</strong>g the sk<strong>in</strong> is important to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether shock is associated with vasoconstriction<br />

(traumatic, hypovolemic, or cardiogenic) or vasodilatation (septic, neurogenic, or anaphylactic).<br />

Auscultation identifies life threats associated with the lower airway (e.g., bronchoconstriction,<br />

tension pneumothorax) or circulation (mitral valvular <strong>in</strong>sufficiency, aortic stenosis).<br />

10. Once I have identified the life threat, what do I do?<br />

Stop! Intervene to reverse the life threat. Ifthe problem is respiratory distress due to tension<br />

pneumothorax, immediate thoracocentesis is required. If the problem is blood loss, volume<br />

restoration and control of hemorrhage (when possible) are <strong>in</strong>dicated.<br />

11, Now that I have identified and reversed the life threat, what next?<br />

The veter<strong>in</strong>arian must develop a list of rule-outs, beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g with the most serious condition<br />

and work<strong>in</strong>g downward. An example is a young dog with a seriously swollen head and respiratory<br />

distress. Instead of assum<strong>in</strong>g that the condition is due to trauma, the veter<strong>in</strong>arian also must<br />

consider cellulitis, anaphylaxis, or rattlesnake envenomation. If respiratory distress has been alleviated,<br />

you have time to consider the other possibilities and take appropriate action.<br />

12. Why do rule-outs sometimes lead to problems?<br />

The tendency is to th<strong>in</strong>k of the most common or statistically most probable explanation of<br />

the animal's condition. This approach provides the correct solution <strong>in</strong> most cases, but you may<br />

overlook the most serious, albeit usually least common, problem. The practice of veter<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

emergency medic<strong>in</strong>e often requires you to react rather than contemplate the answer. Consider the<br />

most serious condition possible and, through a logical process of elim<strong>in</strong>ation, rule it out. Thus<br />

you will arrive at the correct and generally more common diagnosis.<br />

13. Is diagnosis a requirement dur<strong>in</strong>g an emergency?<br />

Ofcourse not. Sometimes it takes hours, days, weeks, or even months to make the f<strong>in</strong>al diagnosis.<br />

It is unreasonable to expect that every emergency patient should have a diagnosis. The<br />

veter<strong>in</strong>arian's role <strong>in</strong> an emergency is to rule out serious or life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g causes for the<br />

animal's immediate condition. If you are an obsessive-compulsive personality with a need for<br />

absolute certa<strong>in</strong>ty before you act to stabilize an animal, you will f<strong>in</strong>d emergencies an unhealthy<br />

area of work.<br />

14. Describe the traditional approach vs. the algorithmic approach to emergency patients,<br />

The traditional approach to an emergency is first to determ<strong>in</strong>e the diagnosis, then to provide<br />

treatment, and then to monitor the patient (Fig. I). This highly <strong>in</strong>efficient system often overlooks<br />

life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g emergencies. A more efficient system is to use def<strong>in</strong>ed algorithms <strong>in</strong> which the<br />

veter<strong>in</strong>arian takes a triage approach, <strong>in</strong>itiates treatment, and monitors the patient as problems are<br />

identified (Fig. 2).

Decision Mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Veter<strong>in</strong>ary Emergency Medic<strong>in</strong>e 3<br />

Figure 1. The traditional approach to an emergency <strong>in</strong>volves diagnosis, followed by treatment and monitor<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

This <strong>in</strong>efficient system is likely to result <strong>in</strong> delayed treatment of life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g emergencies<br />

Figure 2. The algorithmic approach to an emergency <strong>in</strong>volves a systems triage for diagnosis, treatment, and<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g. As a problem is identified, it is treated, and monitor<strong>in</strong>g is begun.<br />

15. How do I decide whether to hospitalize the animal?<br />

Tough question. Obviously several factors are important <strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g this decision:<br />

• The medicaUsurgical condition is the first factor to consider. One crucial question must be<br />

answered: "Is there a need that can be fulfilled only by hospitalization?" For example, is<br />

oxygen, special monitor<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>tensive fluid therapy, or <strong>in</strong>travenous medication required?

4 Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation<br />

• Will the animal receive proper obserVation and treatment if discharged to the owner? Does<br />

the animal even have an owner? '<br />

• Unfortunately, economics must be factored <strong>in</strong>to the decision. If the animal's owner cannot<br />

afford hospitalization, the veter<strong>in</strong>arian is faced with two important decisions: (I) Is there<br />

any way the animal can be treated at home without endanger<strong>in</strong>g survival? (2) Is the condition<br />

so severe that euthanas!a is a viable option?<br />

16. What criteria may be used for treatment of <strong>animals</strong> admitted without the owner?<br />

• Is there any way to identify the animal's owner? Check for microchips by scann<strong>in</strong>g, look<br />

for a tattoo <strong>in</strong>side the gro<strong>in</strong> or p<strong>in</strong>na, check for tags on the animal's collar, ask the person<br />

admitt<strong>in</strong>g the animal if he or she has seen the animal before, and ask the hospital staff if<br />

they recognize the animal.<br />

• Can the animal be made comfortable enough to be held for at least a part of the hold<strong>in</strong>g<br />

period required by local ord<strong>in</strong>ances?<br />

• Is the animal adoptable? Have you met a veter<strong>in</strong>arian, veter<strong>in</strong>ary technician, or student who<br />

has not adopted an ill or <strong>in</strong>jured animal? I doubt it.<br />

Remember, if the animal enters your front door, you are committed to provide at least first<br />

aid care, no matter what the resources of the person admitt<strong>in</strong>g the animal.<br />

17. When is euthanasia for humane reasons <strong>in</strong>dicated?<br />

First, you need to know local ord<strong>in</strong>ances. If the animal cannot be made comfortable, it probably<br />

should be euthanized. Make complete notes <strong>in</strong> the medical record, and focus on terms such<br />

as pa<strong>in</strong>, suffer<strong>in</strong>g, imm<strong>in</strong>ent demise, coma, severe respiratory distress, irreversible shock, uncontrollable<br />

hemorrhage, irreversible neurologic <strong>in</strong>juries, and unlikelihood of return<strong>in</strong>g the animal to<br />

a "useful purpose."<br />

18. Any last thoughts about decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> emergencies?<br />

Often the good samaritan who br<strong>in</strong>gs the animal to you <strong>in</strong> an emergency will go to great<br />

lengths to sway your judgment. He or she may even offer to pay (but rarely does so!). Consult<br />

with colleagues and professional staff, and, ultimately, do what you th<strong>in</strong>k is best for the animal.<br />

By all means, keep good records.<br />

2. CARDIOPULMONARY ARREST AND<br />

RESUSCITATION IN SMALL ANIMALS<br />

Wayne E. W<strong>in</strong>gfield. M.S.. D.v.M.<br />

1. Derme cardiopulmonary arrest and list the three phases of <strong>resuscitation</strong>.<br />

Cardiopulmonary arrest is def<strong>in</strong>ed as the abrupt, unexpected cessation of spontaneous and<br />

effective ventilation and systemic perfusion (circulation). Cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong> (CPR)<br />

provides artificial ventilation and circulation until advanced life support can be provided and<br />

spontaneous circulation and ventilation can be restored. CPR is divided <strong>in</strong>to three support stages:<br />

• Basic life support<br />

• Advanced life support<br />

• Prolonged life support<br />

2. Which <strong>animals</strong> are at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest? What are the predispos<strong>in</strong>g factors?<br />

Cardiopulmonary arrest usually results from cardiac dysrhythmia. It may be due to primary cardiac<br />

disease or diseases that affect other organs. In most <strong>animals</strong>, arrest is associated with diseases of<br />

the respiratory system (pneumonia, laryngeal paralysis, neoplasia, thoracic effusions, and aspira-

4 Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation<br />

• Will the animal receive proper obserVation and treatment if discharged to the owner? Does<br />

the animal even have an owner? '<br />

• Unfortunately, economics must be factored <strong>in</strong>to the decision. If the animal's owner cannot<br />

afford hospitalization, the veter<strong>in</strong>arian is faced with two important decisions: (I) Is there<br />

any way the animal can be treated at home without endanger<strong>in</strong>g survival? (2) Is the condition<br />

so severe that euthanas!a is a viable option?<br />

16. What criteria may be used for treatment of <strong>animals</strong> admitted without the owner?<br />

• Is there any way to identify the animal's owner? Check for microchips by scann<strong>in</strong>g, look<br />

for a tattoo <strong>in</strong>side the gro<strong>in</strong> or p<strong>in</strong>na, check for tags on the animal's collar, ask the person<br />

admitt<strong>in</strong>g the animal if he or she has seen the animal before, and ask the hospital staff if<br />

they recognize the animal.<br />

• Can the animal be made comfortable enough to be held for at least a part of the hold<strong>in</strong>g<br />

period required by local ord<strong>in</strong>ances?<br />

• Is the animal adoptable? Have you met a veter<strong>in</strong>arian, veter<strong>in</strong>ary technician, or student who<br />

has not adopted an ill or <strong>in</strong>jured animal? I doubt it.<br />

Remember, if the animal enters your front door, you are committed to provide at least first<br />

aid care, no matter what the resources of the person admitt<strong>in</strong>g the animal.<br />

17. When is euthanasia for humane reasons <strong>in</strong>dicated?<br />

First, you need to know local ord<strong>in</strong>ances. If the animal cannot be made comfortable, it probably<br />

should be euthanized. Make complete notes <strong>in</strong> the medical record, and focus on terms such<br />

as pa<strong>in</strong>, suffer<strong>in</strong>g, imm<strong>in</strong>ent demise, coma, severe respiratory distress, irreversible shock, uncontrollable<br />

hemorrhage, irreversible neurologic <strong>in</strong>juries, and unlikelihood of return<strong>in</strong>g the animal to<br />

a "useful purpose."<br />

18. Any last thoughts about decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> emergencies?<br />

Often the good samaritan who br<strong>in</strong>gs the animal to you <strong>in</strong> an emergency will go to great<br />

lengths to sway your judgment. He or she may even offer to pay (but rarely does so!). Consult<br />

with colleagues and professional staff, and, ultimately, do what you th<strong>in</strong>k is best for the animal.<br />

By all means, keep good records.<br />

2. CARDIOPULMONARY ARREST AND<br />

RESUSCITATION IN SMALL ANIMALS<br />

Wayne E. W<strong>in</strong>gfield. M.S.. D.v.M.<br />

1. Derme cardiopulmonary arrest and list the three phases of <strong>resuscitation</strong>.<br />

Cardiopulmonary arrest is def<strong>in</strong>ed as the abrupt, unexpected cessation of spontaneous and<br />

effective ventilation and systemic perfusion (circulation). Cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong> (CPR)<br />

provides artificial ventilation and circulation until advanced life support can be provided and<br />

spontaneous circulation and ventilation can be restored. CPR is divided <strong>in</strong>to three support stages:<br />

• Basic life support<br />

• Advanced life support<br />

• Prolonged life support<br />

2. Which <strong>animals</strong> are at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest? What are the predispos<strong>in</strong>g factors?<br />

Cardiopulmonary arrest usually results from cardiac dysrhythmia. It may be due to primary cardiac<br />

disease or diseases that affect other organs. In most <strong>animals</strong>, arrest is associated with diseases of<br />

the respiratory system (pneumonia, laryngeal paralysis, neoplasia, thoracic effusions, and aspira-

6 Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation<br />

animal <strong>in</strong> ventral recumbency <strong>in</strong> preparation for <strong>in</strong>tubation with an endotracheal tube. Place the<br />

endotracheal tube accurately by utiliz<strong>in</strong>g a laryngoscope.<br />

9. How do we breathe for the animal?<br />

First, ensure that the animal is apneic and requires assisted ventilation. Once you have seen<br />

that there is no movement to the chest wall, beg<strong>in</strong> to ventilate the animal with two long breaths<br />

(1.5-2.0 seconds each). If the animal does not beg<strong>in</strong> to breathe with<strong>in</strong> 5-7 seconds, beg<strong>in</strong> to ventilate<br />

at a rate of 12-20 times/m<strong>in</strong>ute.<br />

Use of acupuncture to stimulate respirations has been reported. Plac<strong>in</strong>g a needle <strong>in</strong> acupuncture<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t Jen Chung (GV26) may reverse respiratory arrest under cl<strong>in</strong>ical conditions. The technique<br />

<strong>in</strong>volves us<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>small</strong> (22-28 gauge, 1-1.5 <strong>in</strong>ch) needle <strong>in</strong> the nasal philtrum at the ventral<br />

limit of the nares. The needle is twirled strongly and moved up and down while improvement <strong>in</strong><br />

respiration is monitored. This simple technique can be used quickly. This technique will not work<br />

<strong>in</strong> every case, nor will it work if a narcotic antagonist, such as naloxone, has been given before<br />

<strong>in</strong>sertion of the acupuncture needle.<br />

10. How is circulation supported dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR?<br />

Assessment is necessary to determ<strong>in</strong>e the pulselessness of the animal before <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g external<br />

cardiac compression. Currently there are two theories to expla<strong>in</strong> the mechanism of forward<br />

blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR: (I) cardiac pump theory and (2) thoracic pump theory. The cardiac pump<br />

theory is probably more important <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>er <strong>animals</strong> « 7 kg) and the thoracic pump <strong>in</strong> larger <strong>animals</strong><br />

(> 7 kg). It is believed that the cardiac and thoracic pumps are <strong>in</strong>teractive; each contributes<br />

to the pressure gradients responsible for blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR.<br />

11. What is the cardiac pump theory?<br />

The orig<strong>in</strong>al hypothesis suggests that blood flow to the periphery dur<strong>in</strong>g external cardiac<br />

compression of the heart results from direct compression of the heart between the sternum and<br />

vertebrae (dorsal recumbency) or between the right and left thoracic wall (lateral recumbency) of<br />

the dog and cat. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to this concept, thoracic compression (artificial systole) is similar to<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal cardiac massage and results <strong>in</strong> squeez<strong>in</strong>g of blood from both ventricles <strong>in</strong>to the pulmonary<br />

arteries and aorta as the pulmonary and aortic valves open. Retrograde flow of blood is<br />

prevented by closure of the left and right atrioventricular valves. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the relaxation phase of<br />

thoracic compression (artificial diastole), the ventricles recoil to their orig<strong>in</strong>al shape and fill by a<br />

suction effect, while elevated arterial pressure closes the aortic and pulmonic valves.<br />

12. What is the thoracic pump theory?<br />

As pressure is applied to the animal's thorax, there is a correlation between the rise <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>trathoracic<br />

pressure dur<strong>in</strong>g compression and the apparent magnitude of carotid artery blood flow<br />

and pressure. For bra<strong>in</strong> blood flow to occur dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>resuscitation</strong>, a carotid arterial-to-jugular pressure<br />

gradient must be present dur<strong>in</strong>g chest compression. Experimental studies <strong>in</strong> large dogs have<br />

shown that thoracic compression dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR results <strong>in</strong> an essentially equal rise <strong>in</strong> central venous,<br />

right atrial, pulmonary artery, aortic, esophageal, and lateral pleural space pressures with no transcardiac<br />

gradient. Aortic pressure is efficiently transmitted to the carotid arteries, but retrograde<br />

transmission of <strong>in</strong>trathoracic venous pressure <strong>in</strong>to the jugular ve<strong>in</strong>s is prevented by valves at the<br />

thoracic <strong>in</strong>let and possibly by venous collapse. Thus, dur<strong>in</strong>g artificial systole a peripheral arterial<br />

venous pressure gradient appears, and blood flow results from this gradient. In such a system,<br />

there is no pressure gradient across the heart; thus, the heart acts merely as a passive conduit.<br />

C<strong>in</strong>eangiographic studies <strong>in</strong> large dogs confirm these observations by demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g partial right<br />

atrioventricular valve closure, collapse of the venae cavae, and open<strong>in</strong>g of the pulmonary, left atrioventricular,<br />

and aortic valves dur<strong>in</strong>g thoracic compression. When thoracic compression is released<br />

(artificial diastole), <strong>in</strong>trathoracic pressures fall toward zero, and venous flow to the right<br />

heart and lungs occurs. Dur<strong>in</strong>g artificial diastole, a modest gradient also develops between the <strong>in</strong>trathoracic<br />

aorta and the right atrium, provid<strong>in</strong>g coronary (myocardial) perfusion.

Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation 7<br />

In <strong>small</strong> dogs receiv<strong>in</strong>g vigorous chest compressions, <strong>in</strong>trathoracic vascular pressures are<br />

much higher than recorded pleural pressures. The rise <strong>in</strong> vascular pressures probably results from<br />

compression of the heart dur<strong>in</strong>g chest compression and not from ris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>trathoracic pressure.<br />

13. What are the determ<strong>in</strong>ants of vital organ perfusion dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR?<br />

Cerebral blood flow depends on the gradient between the carotid artery and <strong>in</strong>tracranial pressure<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g systole (thoracic compression). Myocardial blood flow depends on the gradient between<br />

the aorta and right atrium dur<strong>in</strong>g diastole (release phase of thoracic compression). Dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

conventional CPR, cerebral and myocardial blood flow is less than 5% ofprearrest values. Below<br />

the diaphragm, renal and hepatic blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR is 1-5% of prearrest values.<br />

14. What are the determ<strong>in</strong>ants of improved vital organ perfusion dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR?<br />

Force, rate, and duration of chest compression dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR determ<strong>in</strong>e the effectiveness of<br />

organ perfusion. Regardless of the mechanism of forward blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

force of chest compressions <strong>in</strong>creases arterial pressures. At pressures> 400 newtons (about 40<br />

kg), bone and tissue trauma are more likely. Increas<strong>in</strong>g the rate of chest compressions significantly<br />

<strong>in</strong>creases the arterial pressure.<br />

GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR CPR IN ANIMALS<br />

15. What is the optimal position for maximiz<strong>in</strong>g blood flow?<br />

Lateral recumbency (the sternum must be kept parallel to the table top by either plac<strong>in</strong>g a fist<br />

under the chest wall or us<strong>in</strong>g a sand bag to hold the sternum off the table top) is used for <strong>animals</strong><br />

< 7 kg and, ideally, dorsal recumbency for <strong>animals</strong>> 7 kg. It is extremely difficult to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a<br />

dog <strong>in</strong> dorsal recumbency without special V-shaped troughs or other techniques. However, dorsal<br />

recumbency provides maximal changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>trathoracic pressure and thus forward blood flow.<br />

When no peripheral pulse is felt dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR, consider chang<strong>in</strong>g the animal's position and CPR<br />

technique.<br />

16. What is the optimal compression/relaxation ratio for adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g external cardiac<br />

compression?<br />

Studies have shown the best ratio of cardiac compression to ventilation is I:I (simultaneous<br />

compression-ventilation) <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. You breathe for the animal each time you compress the thoracic<br />

wall.<br />

17. At what rate should you compress and ventilate when two persons are available to do<br />

CPR?<br />

In <strong>animals</strong> weigh<strong>in</strong>g < 7 kg, the recommended rate of ventilation and compression is 120<br />

times/m<strong>in</strong>ute. In <strong>animals</strong> weigh<strong>in</strong>g> 7 kg, the rate of compression and ventilation is 80-100<br />

times/m<strong>in</strong>ute.<br />

18. What is <strong>in</strong>terposed abdom<strong>in</strong>al compression?<br />

To improve venous return and to decrease arterial run-off dur<strong>in</strong>g external thoracic compression,<br />

have one person press on the cranial abdomen between each compression of the chest. In<br />

humans, this technique improves hospital discharge rates as much as 33%. No comparable studies<br />

are yet available <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>.<br />

19. What if only one person is available to do CPR?<br />

One-person CPR <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong> is highly <strong>in</strong>effective. The ratio of ventilation to chest compression<br />

is 15:2. Give IS chest compressions and then 2 long ventilations. Use a rate of 120 chest<br />

compressions/m<strong>in</strong>ute when the animal weighs < 7 kg and 80-100 times/m<strong>in</strong>ute when the animal<br />

weighs> 7 kg.

8 Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation<br />

A recent report <strong>in</strong> experimentally <strong>in</strong>duced CPR <strong>in</strong> sw<strong>in</strong>e has shown an excellent <strong>resuscitation</strong><br />

rate through provid<strong>in</strong>g only cardiac compression. In fact, the researchers were unable<br />

to detect a difference <strong>in</strong> hemodynamics, 48-hour survival, or neurologic outcome when CPR<br />

was applied with or without ventilatory support. With this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, if <strong>in</strong>adequate numbers of<br />

professional staff are available, apply only cardiac compression if cardiopulmonary arrest is<br />

present.<br />

20. When should I open the chest and do CPR?<br />

Chest compressions raise the venous (right atrial) pressure peaks almost as high as arterial<br />

pressure peaks and <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>tracranial pressure, thus caus<strong>in</strong>g low cerebral and myocardial perfusion<br />

pressures. Open-chest CPR does not raise atrial pressures and provides better cerebral and<br />

coronary perfusion pressures and flows than external CPR <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. When applied promptly <strong>in</strong><br />

operat<strong>in</strong>g room arrests, open-chest CPR, which was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> the l880s, yields good cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

results <strong>in</strong> people. The switch from external to open-chest CPR has not yet improved outcome <strong>in</strong><br />

humans, probably because its <strong>in</strong>itiation is too late. No comparable studies are available for cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

open-chest CPR <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. Currently, open-chest CPR should be restricted to the operat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

room and <strong>in</strong> selected <strong>in</strong>stances of penetrat<strong>in</strong>g thoracic <strong>in</strong>jury.<br />

21. How can I monitor the effectiveness of external thoracic compressions?<br />

Traditionally, the presence of a pulse dur<strong>in</strong>g thoracic compression has been the hallmark of<br />

effective compression. More recently, monitor<strong>in</strong>g of peripheral pulses with quantitative Doppler<br />

techniques has shown that the pulse generated dur<strong>in</strong>g compression is <strong>in</strong> fact from venous and not<br />

arterial flow. In veter<strong>in</strong>ary medic<strong>in</strong>e, monitor<strong>in</strong>g the pulse is the most common technique of monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

effectiveness.<br />

Pulse oximetry provides <strong>in</strong>formation about hemoglob<strong>in</strong> saturation. Dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR you should<br />

see an improvement <strong>in</strong> oximetry values and mucous membrane color. End-tidal carbon dioxide<br />

(COz) monitor<strong>in</strong>g has proved to be the most effective means of measur<strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness of<br />

CPR. This device fits <strong>in</strong>-l<strong>in</strong>e with the endotracheal tube and measures COzlevels. With effective<br />

CPR you should see an <strong>in</strong>creased end-tidal COz.<br />

22. What can I do if there is no pulse or change <strong>in</strong> oximetry or end-tidal CO 2?<br />

Consider chang<strong>in</strong>g the position of the animal and the force or rate of thoracic compression.<br />

23. How can I tra<strong>in</strong> my staff <strong>in</strong> CPR?<br />

Periodic tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sessions <strong>in</strong> basic life support should be conducted <strong>in</strong> every veter<strong>in</strong>ary practice.<br />

This is not a time-consum<strong>in</strong>g activity, and the benefits are tremendous when the staff can respond<br />

quickly and efficiently. An effective means to provide tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is to develop an <strong>in</strong>expensive<br />

CPR animal. Such teach<strong>in</strong>g aids were developed by tak<strong>in</strong>g old corrugated anesthetic tub<strong>in</strong>g (trachea),<br />

an anesthetic Y-piece (tracheal bifurcation), two anesthetic rebreath<strong>in</strong>g bags (lungs), and<br />

implant<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> the chest ofa stuffed animal. These devices can be used to practice CPR techniques<br />

with your staff. One can place foreign materials <strong>in</strong> the mouth, practice Jen Chung maneuvers,<br />

palpate for pulses, see the thorax expand with each breath, and feel the expand<strong>in</strong>g lungs as<br />

you apply chest compression. Practice sessions can be called at any time to simulate a sudden,<br />

unexpected arrest.<br />

ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT<br />

24. Which drugs should I have available <strong>in</strong> the "crash cart"?<br />

Drugs considered necessary for cardiopulmonary arrest are (1) ep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e, (2) atrop<strong>in</strong>e, (3)<br />

magnesium chloride, (4) naloxone, (5) lidoca<strong>in</strong>e, (6) sodium bicarbonate, (7) methoxam<strong>in</strong>e, and<br />

(8) bretylium tosylate.

Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation 9<br />

25. What other drugs should I have available?<br />

Drugs that are important <strong>in</strong> the post<strong>resuscitation</strong> phase of CPR <strong>in</strong>clude (1) dobutam<strong>in</strong>e, (2)<br />

mannitol, (3) furosemide, (4) lidoca<strong>in</strong>e, (5) verapamii, (6) sodium bicarbonate, (7) dopam<strong>in</strong>e,<br />

and (8) <strong>in</strong>travenous fluids.<br />

26. What are the <strong>in</strong>dications for emergency drug use dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR?<br />

1. To <strong>in</strong>itiate electrical activity<br />

2. To <strong>in</strong>crease heart rate<br />

3. To improve myocardial oxygenation<br />

4. To control life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g dysrhythmias<br />

27. What is the best route for adm<strong>in</strong>istration of drugs dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR?<br />

Each of the four commonly used routes for drug adm<strong>in</strong>istration dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR has its advantages<br />

and disadvantages.<br />

1. Intravenous (IV). The preferred route for drug adm<strong>in</strong>istration dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR is the IV<br />

route. With central venous catheters, drugs can be rapidly delivered to their site of action via the<br />

coronary arteries. In giv<strong>in</strong>g IV drugs dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR, it is important to follow each drug with a<br />

bolus of sal<strong>in</strong>e or water for <strong>in</strong>jection to encourage the transport of the drug toward the heart because<br />

cardiopulmonary arrest usually results <strong>in</strong> hypotension, vasoconstriction, and hypovolemia.<br />

At present no conclusive data support the use ofa central venous rather than a peripheral<br />

venous route.<br />

2. Intratracheal (IT). The IT route has the advantages of accessibility, close proximity to<br />

the left side of the heart via the pulmonary ve<strong>in</strong>s, and a large surface area for drug absorption.<br />

The disadvantages are the <strong>in</strong>creased dosage required for many drugs (often 10 times the dosage<br />

given IV), decreased efficacy <strong>in</strong> the presence of pulmonary disease, and the fact that some drugs<br />

cannot be given IT (Le., sodium bicarbonate).<br />

3. Intraosseous (10) or <strong>in</strong>tramedullary. The bone marrow cavity provides extensive<br />

venous access to the cardiovascular system. Drugs normally given via the IV route may be given<br />

via the bone marrow cavity. The bone marrow cavity is most commonly accessed either through<br />

the trochanteric fossa of the femur or the distal cranial femur dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR.<br />

4. Intracardiac (IC). Drugs can be delivered directly to the heart via the <strong>in</strong>tracardiac route.<br />

The difficulty of us<strong>in</strong>g the IC route comes with the <strong>in</strong>ability of personnel to <strong>in</strong>ject drugs <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

heart. Without the apex beat normally present, many f<strong>in</strong>d this technique to be most difficult <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>.<br />

In addition there are problems with the delivery of drugs <strong>in</strong>to the myocardium <strong>in</strong>stead of<br />

the ventricular chambers. Delivery <strong>in</strong>to the myocardium may result <strong>in</strong> dysrhythmias and laceration<br />

ofcoronary arteries, and requires discont<strong>in</strong>uance of basic life support while IC <strong>in</strong>jections are<br />

attempted.<br />

28. What are the common cardiac rhythms of cardiopulmonary arrest?<br />

The only way to dist<strong>in</strong>guish the various dysrhythmias of arrest is an electrocardiogram.<br />

I. Ventricular asystole is characterized by absence of both mechanical and electrical activity<br />

on the electrocardiogram (see figure below).<br />

Treatment: ep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e, atrop<strong>in</strong>e.

Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation II<br />

Curves show<strong>in</strong>g estimated sources of defibrillation vs. delivered energy after 1,5, and 9 m<strong>in</strong>utes of fibrillation<br />

<strong>in</strong> dogs receiv<strong>in</strong>g closed-chest cardiac massage and artificial ventilation with ep<strong>in</strong>ephr<strong>in</strong>e. (From Yakaitis<br />

RW, Ewy GA, Otto GW, et al: Influence of time and therapy on VF <strong>in</strong> dogs. Crit Care Med 8: 157, 1980; with<br />

permission.)<br />

29. In us<strong>in</strong>g an electrical defibrillator, what important po<strong>in</strong>ts should be kept <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d?<br />

The electrical defibrillator is the treatment of choice for ventricular fibrillation. It is also a<br />

dangerous <strong>in</strong>strument that can cause <strong>in</strong>jury to the patient and death to the veter<strong>in</strong>arian if improperly<br />

used. The optimal delivered energy to the myocardium is roughly 2-4 joules/kg. In deliver<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this countershock to the myocardium, it is necessary to "hit" only about 28% of the<br />

myocardial cells to defibrillate. Thus. paddle position is not as important as once believed. One<br />

should make every effort to reduce transthoracic impedance dur<strong>in</strong>g electrical defibrillation. The<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g factors <strong>in</strong>fluence impedance:<br />

I. Use large surface area paddles.<br />

2. Countershocks applied close together may be most effective.<br />

3. Use an electrode-sk<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terface material such as electrolyte paste or gel. Do not use alcohol.<br />

4. Apply pressure to the electrodes.<br />

5. Defibrillate dur<strong>in</strong>g expiration.<br />

Be careful! Always announce "all clear!," and look around to be sure that nobody is <strong>in</strong> contact<br />

with the animal, table, or <strong>in</strong>struments.<br />

30. What is the difference between a cat and dog <strong>in</strong> ventricular fibrillation?<br />

In normal cats, the heart is generally <strong>small</strong> enough that it may spontaneously convert from<br />

ventricular fibrillation to s<strong>in</strong>us rhythm. Unfortunately, sick cats also may have enlarged hearts. In<br />

such cases, electrical defibrillation should be attempted.<br />

31. Which drugs should be used with caution dur<strong>in</strong>g advanced life support?<br />

1. Calcium enhances ventricular excitability (thus <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g myocardial oxygen requirements);<br />

it decreases s<strong>in</strong>us nodal impulse formation, reduces blood flow to the bra<strong>in</strong> to nearly zero<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR, causes coronary artery vasospasm, and is an important mediator <strong>in</strong> the formation of

Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation 13<br />

Cardiopulmonary arrest <strong>in</strong> dogs. (From W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE, Van Pelt DR: Respiratory and cardiopulmonary arrest<br />

<strong>in</strong> dogs and cats: 265 cases (1986-1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 200:1993-1996,1992; with permission.)<br />

34. What cerebral complications may be expected after cardiac arrest?<br />

In normal bra<strong>in</strong>, autoregulation ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s a global cerebral bra<strong>in</strong> flow of about 50 ml/IOO<br />

gm bra<strong>in</strong>/m<strong>in</strong>ute despite cerebral perfusion pressures (CPP) (Le., mean arterial pressure<br />

m<strong>in</strong>us <strong>in</strong>tracranial pressure) between 50 and 150 mmHg. When CPP drops below 50 mmHg,<br />

cerebral blood flow decreases, and the viability of normal neurons seems threatened by CPP<br />

< 30 mmHg, global cerebral blood flow < 15 mlllOO gmlm<strong>in</strong>ute, or cerebral venous oxygen<br />

partial pressures (P0 2 ) < 20 mmHg. Dur<strong>in</strong>g complete cerebral ischemia, calcium shifts, bra<strong>in</strong><br />

tissue lactic acidosis, and <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> the bra<strong>in</strong> free acids, osmolality and extracellular concentration<br />

of excitatory am<strong>in</strong>o acids (particularly glutamate and aspartate) set the stage for reoxygenation<br />

<strong>in</strong>jury.<br />

35. What is the pathophysiology ofthe cerebral <strong>in</strong>jury after <strong>resuscitation</strong>?<br />

Perfusion failure (i.e., <strong>in</strong>adequate oxygen delivery) seems to progress through four stages:<br />

1. Multifocal no reflow occurs immediately and seems to be readily overcome by normotensive<br />

or hypertensive reperfusion.<br />

2. Transient global "reactive" hyperemia lasts 15-30 m<strong>in</strong>utes.<br />

3. Delayed, prolonged global and multifocal hypoperfusion occurs about 2-12 hours after<br />

arrest; global cerebral blood flow is reduced to about 50% of basel<strong>in</strong>e, whereas global oxygen<br />

uptake returns to or above basel<strong>in</strong>e levels and cerebral venous P0 2 decreases to < 20 mmHg, reflect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mismatch<strong>in</strong>g of oxygen delivery to oxygen uptake.<br />

4. After 20 hours, either normal global cerebral blood flow and global oxygen uptake are restored,<br />

both rema<strong>in</strong> low (with coma), or secondary hyperemia develops (postulated to be associated<br />

with reduced oxygen uptake), followed by bra<strong>in</strong> death.<br />

Reoxygenation, although essential, also may provide chemical cascades (<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g free<br />

iron, free radical, calcium shifts, acidosis, excitatory am<strong>in</strong>o acids, and catecholam<strong>in</strong>es) that result<br />

<strong>in</strong> lipid peroxidation of membranes.<br />

Extracerebral derangements, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>toxication from postanoxic viscera, can worsen<br />

cerebral outcome. Studies <strong>in</strong> dogs have shown a delayed reduction <strong>in</strong> cardiac output follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cardiac arrest despite controlled normotension. Pulmonary edema can be prevented by prolonged<br />

controlled ventilation.<br />

Blood derangements due to stasis <strong>in</strong>clude aggregates of polymorphonuclear leukocytes<br />

and macrophages that may obstruct capillaries, release free radicals, and damage endothelium.

14 Cardiopulmonary Arrest and Resuscitation<br />

36. How do we manage the post<strong>resuscitation</strong> patient to reduce the adverse complications of<br />

CPR?<br />

Careful monitor<strong>in</strong>g is most important dur<strong>in</strong>g the first 4 hours after arrest. AlI patients require<br />

oxygen adm<strong>in</strong>istered via oxygen cage, nasal <strong>in</strong>sufflation, or facemask. If CPR was successful,<br />

one needs to support the heart dur<strong>in</strong>g the post<strong>resuscitation</strong> phase. This support is directed to <strong>in</strong>otropic<br />

support (dobutam<strong>in</strong>e or dopam<strong>in</strong>e), possibly us<strong>in</strong>g vasodilator drugs (sodium nitroprusside),<br />

and antiarrhythmic drugs (lidoca<strong>in</strong>e). These drugs help to reduce the pulmonary edema<br />

usualIy seen after arrest. In addition, furosemide is usually adm<strong>in</strong>istered to reduce pulmonary<br />

edema. Cerebral hypoxia and ischemia result dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR. The end result is cerebral edema.<br />

Treatment for cerebral edema <strong>in</strong>cludes mannitol and usually corticosteroids. Additional drugs<br />

that may improve cerebral <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong>clude the follow<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

• Calcium channel blockers reverse cerebral vasospasm and prevent lethal <strong>in</strong>tracelIular calcium<br />

<strong>in</strong>flux.<br />

• Barbiturates, which are mild calcium antagonists, decrease arachidonic acid and free fatty<br />

acid levels <strong>in</strong> neurons as welI as metabolic demands of the bra<strong>in</strong>. To date, no conclusive evidence<br />

supports the use of barbiturates. In addition, the sedation that results makes sequential<br />

neurologic assessment impossible.<br />

• Iron-chelat<strong>in</strong>g drugs and free radical scavengers. Although experimental at this po<strong>in</strong>t, results<br />

are promis<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

37. How do you know the cerebral outcome of the patient after CPR?<br />

One should always be concerned about irreversible cerebral <strong>in</strong>jury after arrest. Daily neurologic<br />

evaluations and assessment are required. Record f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs each day to note the patient's<br />

progress. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical features to observe after arrest <strong>in</strong>clude the folIow<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

• Reactivity of the pupils • Motor responses<br />

• Increased responsiveness • Motor postures<br />

• Breath<strong>in</strong>g patterns<br />

38. Are certa<strong>in</strong> patients unlikely to be resuscitated?<br />

No studies are currently available <strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>, but studies <strong>in</strong> humans <strong>in</strong>dicate that certa<strong>in</strong><br />

groups of patients do not survive-patients with oliguria, metastatic cancer, sepsis, pneumonia,<br />

and acute stroke. Probably <strong>animals</strong> with these conditions also will not survive.<br />

39. When do we use do-not-resuscitate orders?<br />

Do-not-resuscitate orders must be <strong>in</strong>itiated by the owner. Good client communications are<br />

useful whenever an animal is hospitalized. It is probably wise to advise owners that arrest occurs<br />

suddenly and unexpectantly. Ask the owner how far you should go if the pet arrests. Record the<br />

response, and abide by the owner's wishes.<br />

The decision to stop CPR must be tempered with common sense, client communication, and<br />

experience of the resuscitators. Our experience suggests that the mean duration of CPR is generally<br />

about 20 m<strong>in</strong>utes.<br />

After more than 30 years of widespread use of CPR, reevaluation of its benefits <strong>in</strong> terms of<br />

survival and quality of life shows it to be a desperate effort that helps only a limited number of<br />

patients. For most, CPR is unsuccessful.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

I. Babbs CF: Interposed abdom<strong>in</strong>al compression-CPR: A case study <strong>in</strong> cardiac arrest research. Ann Emerg<br />

Med 22:24-32. 1993.<br />

2. Babbs CF: New versus old theories of blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR. Crit Care Med 8:191-196.1980.<br />

3. Babbs CF: Effect of thoracic vent<strong>in</strong>g on arterial pressure, and flow dur<strong>in</strong>g external cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. Crit Care Med 9:785-788. 1981.<br />

4. Berg RA, Wilcoxson D, Hilwig RW, et a1: The need for ventilatory support dur<strong>in</strong>g bystander CPR. Ann<br />

Emerg Med 26:342-350. 1995.<br />

5. Berg RA, Kern KB, Hilwig RW, et al: Assisted ventilation does not improve outcome <strong>in</strong> a porc<strong>in</strong>e model<br />

for s<strong>in</strong>gle-rescuer bystander cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>. Circulation 95: I635-1641. 1997.

Respiratory Distress 15<br />

6. Blumenthal SU, Voorhees WD. The relationship of carbon dioxide excretion dur<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong><br />

to regional blood flow and survival. Resuscitation. 35:135, 1997.<br />

7. Brown SA, Hall ED: Role of oxygen-derived free radicals <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis of shock and trauma, with<br />

focus on central nervous system <strong>in</strong>juries. J Am Vet Med Assoc 200:1849-1858,1992.<br />

8. Chandra NC: Mechanisms of blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR. Ann Emerg Med 22:281-288,1993.<br />

9. DeBehnke DJ: Effects of vagal tone on <strong>resuscitation</strong> from experimental electromechanical dissociation.<br />

Ann Emerg Med 22:1789-1794,1993.<br />

10. Gonzales ER: Pharmacologic controversies <strong>in</strong> CPR. Ann Emerg Med 22:317-323, 1993.<br />

II. Hallstrom A, Cobb L, Johnson E, et al: Cardipulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong> by chest compression alone or with<br />

mouth-to-mouth <strong>resuscitation</strong>. N Engl J Med 342:1546-1553, 2000.<br />

12. Hask<strong>in</strong>s SC: Internal cardiac compression. J Am Vet MedAssoc 200:1945-1946,1992.<br />

13. Henik RA: Basic life support and external cardiac compression <strong>in</strong> dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc<br />

200: 1925-1930, 1992.<br />

14. Idris AH: Reassess<strong>in</strong>g the need for ventilation dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR. Ann Emerg Moo 27:569-575,1996.<br />

15. Kass PH, Hask<strong>in</strong>s SC: Survival follow<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg<br />

Crit Care 2:57-65, 1993.<br />

16. Neimann JT, Rosborough JP, Hausknecht M, et al: Pressure synchronized c<strong>in</strong>eangiography dur<strong>in</strong>g experimental<br />

cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>. Circulation 64:985, 198 I.<br />

17. Neimann JT: Cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>. N Engl J Med 327:1075-1080,1992.<br />

18. Noc M, Weil MH, Tang W, et al: Mechanical ventilation may not be essential for <strong>in</strong>itial cardiopulmonary<br />

<strong>resuscitation</strong>. Chest 108:821-827, 1995.<br />

19. Pepe PE, Abramson NS, Brown CG: ACLS-Does it really work? Ann Emer Med 23: 1037-1041, 1994.<br />

20. RudikoffMT, Maughan WL, Effron M, et al: Mechanisms offlow dur<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>.<br />

Circulation 61 :345-351, 1980.<br />

21. Safer P: Cerebral <strong>resuscitation</strong> after cardiac arrest: Research <strong>in</strong>itiatives and future directions. Ann Emerg<br />

Med 22:324-349, 1993.<br />

22. Shapiro BA: Should the ABCs ofbasic CPR become CABs? Crit Care Moo 26:214-215, 1998.<br />

23. Van Pelt DR, W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE: Controversial issues <strong>in</strong> drug treatment dur<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>.<br />

J Am Vet MedAssoc 200:1938-1944,1992.<br />

24. Ward KR. Sullivan RJ, Zelenak RR, et al: A comparison of <strong>in</strong>terposed abdom<strong>in</strong>al compression CPR and<br />

standard CPR by monitor<strong>in</strong>g end-tidal CO 2 . Ann Emerg Med 18:831-837, 1989.<br />

25. W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE, Van Pelt DR: Respiratory and cardiopulmonary arrest <strong>in</strong> dogs and cats: 265 cases (1986<br />

1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 200: 1993-1996, 1992.<br />

26. W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE: Cardiopulmonary arrest and <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. Part I: Basic life support.<br />

Emerg Sci TechnoI2:21-26, 1996.<br />

27. W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE: Cardiopulmonary arrest and <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. Part II: Advanced and prolonged<br />

life support. Emerg Sci TechnoI2:21-3I, 1996.<br />

28. Yakaitis RW, Ewy GA, Olto CW, et al: Influence of time and therapy on VF <strong>in</strong> dogs. Crit Care Med<br />

8: 157, 1980.<br />

3. RESPIRATORY DISTRESS<br />

Michael S. Lagutchik, D.v.M., M.S.<br />

1. Def<strong>in</strong>e respiratory distress, dyspnea, tachypnea, orthopnea, hyperventilation, hypoventilation,<br />

and apnea.<br />

Respiratory distress is outwardly evident, physically labored respiratory effort that denotes<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ically evident <strong>in</strong>ability to ventilate and/or oxygenate adequately. This is currently the preferred<br />

term for veter<strong>in</strong>ary patients who present with severe respiratory difficulty.<br />

Dyspnea is the conscious perception of"air hunger" or a sense of"shortness ofbreath." This<br />

term is subjective <strong>in</strong> nature and is not ideal to use <strong>in</strong> reference to veter<strong>in</strong>ary patients, because they<br />

cannot relay the perception of respiratory difficulty.<br />

Tachypnea is a respiratory rate that is greater than normal.<br />

Orthopnea is an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> respiratory distress when a patient is ly<strong>in</strong>g down or the chest is<br />

compressed.

Respiratory Distress 15<br />

6. Blumenthal SU, Voorhees WD. The relationship of carbon dioxide excretion dur<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong><br />

to regional blood flow and survival. Resuscitation. 35:135, 1997.<br />

7. Brown SA, Hall ED: Role of oxygen-derived free radicals <strong>in</strong> the pathogenesis of shock and trauma, with<br />

focus on central nervous system <strong>in</strong>juries. J Am Vet Med Assoc 200:1849-1858,1992.<br />

8. Chandra NC: Mechanisms of blood flow dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR. Ann Emerg Med 22:281-288,1993.<br />

9. DeBehnke DJ: Effects of vagal tone on <strong>resuscitation</strong> from experimental electromechanical dissociation.<br />

Ann Emerg Med 22:1789-1794,1993.<br />

10. Gonzales ER: Pharmacologic controversies <strong>in</strong> CPR. Ann Emerg Med 22:317-323, 1993.<br />

II. Hallstrom A, Cobb L, Johnson E, et al: Cardipulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong> by chest compression alone or with<br />

mouth-to-mouth <strong>resuscitation</strong>. N Engl J Med 342:1546-1553, 2000.<br />

12. Hask<strong>in</strong>s SC: Internal cardiac compression. J Am Vet MedAssoc 200:1945-1946,1992.<br />

13. Henik RA: Basic life support and external cardiac compression <strong>in</strong> dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc<br />

200: 1925-1930, 1992.<br />

14. Idris AH: Reassess<strong>in</strong>g the need for ventilation dur<strong>in</strong>g CPR. Ann Emerg Moo 27:569-575,1996.<br />

15. Kass PH, Hask<strong>in</strong>s SC: Survival follow<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg<br />

Crit Care 2:57-65, 1993.<br />

16. Neimann JT, Rosborough JP, Hausknecht M, et al: Pressure synchronized c<strong>in</strong>eangiography dur<strong>in</strong>g experimental<br />

cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>. Circulation 64:985, 198 I.<br />

17. Neimann JT: Cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>. N Engl J Med 327:1075-1080,1992.<br />

18. Noc M, Weil MH, Tang W, et al: Mechanical ventilation may not be essential for <strong>in</strong>itial cardiopulmonary<br />

<strong>resuscitation</strong>. Chest 108:821-827, 1995.<br />

19. Pepe PE, Abramson NS, Brown CG: ACLS-Does it really work? Ann Emer Med 23: 1037-1041, 1994.<br />

20. RudikoffMT, Maughan WL, Effron M, et al: Mechanisms offlow dur<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>.<br />

Circulation 61 :345-351, 1980.<br />

21. Safer P: Cerebral <strong>resuscitation</strong> after cardiac arrest: Research <strong>in</strong>itiatives and future directions. Ann Emerg<br />

Med 22:324-349, 1993.<br />

22. Shapiro BA: Should the ABCs ofbasic CPR become CABs? Crit Care Moo 26:214-215, 1998.<br />

23. Van Pelt DR, W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE: Controversial issues <strong>in</strong> drug treatment dur<strong>in</strong>g cardiopulmonary <strong>resuscitation</strong>.<br />

J Am Vet MedAssoc 200:1938-1944,1992.<br />

24. Ward KR. Sullivan RJ, Zelenak RR, et al: A comparison of <strong>in</strong>terposed abdom<strong>in</strong>al compression CPR and<br />

standard CPR by monitor<strong>in</strong>g end-tidal CO 2 . Ann Emerg Med 18:831-837, 1989.<br />

25. W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE, Van Pelt DR: Respiratory and cardiopulmonary arrest <strong>in</strong> dogs and cats: 265 cases (1986<br />

1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 200: 1993-1996, 1992.<br />

26. W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE: Cardiopulmonary arrest and <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. Part I: Basic life support.<br />

Emerg Sci TechnoI2:21-26, 1996.<br />

27. W<strong>in</strong>gfield WE: Cardiopulmonary arrest and <strong>resuscitation</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong> <strong>animals</strong>. Part II: Advanced and prolonged<br />

life support. Emerg Sci TechnoI2:21-3I, 1996.<br />

28. Yakaitis RW, Ewy GA, Olto CW, et al: Influence of time and therapy on VF <strong>in</strong> dogs. Crit Care Med<br />

8: 157, 1980.<br />

3. RESPIRATORY DISTRESS<br />

Michael S. Lagutchik, D.v.M., M.S.<br />

1. Def<strong>in</strong>e respiratory distress, dyspnea, tachypnea, orthopnea, hyperventilation, hypoventilation,<br />