Available as a PDF download - Gibraltar Ornithological & Natural ...

Available as a PDF download - Gibraltar Ornithological & Natural ...

Available as a PDF download - Gibraltar Ornithological & Natural ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

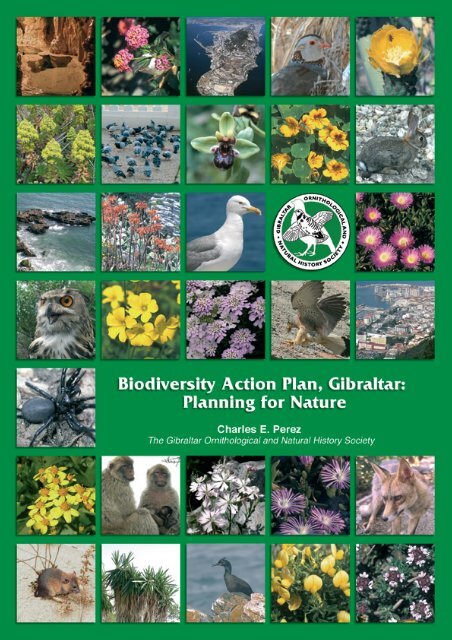

Biodiversity<br />

Action Plan,<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong>:<br />

Planning<br />

for Nature<br />

Charles E. Perez<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong><br />

and <strong>Natural</strong> History Society

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

Copyright © 2006 The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society<br />

Jews’ Gate, Upper Rock Nature Reserve, P.O.Box 843, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

Citation: Perez, C.E. (2006). Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature.<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society. <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

Published by the <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society.<br />

Research and publication funded by the Overse<strong>as</strong> Territories Environment Programme (OTEP)<br />

of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office of Her Majesty’s Government.<br />

Printed and bound by Roca Graphics Ltd.<br />

Tuckey’s Lane, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>. Tel. +(350) 59755 - From Spain: (9567) 59755

Contents<br />

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

1) Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9<br />

What is Biodiversity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9<br />

The Biodiversity Convention . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12<br />

The Significance of Biodiversity. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13<br />

Threats to Biodiversity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Action Plan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16<br />

2) The International Context. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19<br />

EU Birds Directive. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20<br />

The Bonn Convention . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24<br />

EUROBATS.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27<br />

ACCOBAMS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27<br />

Bern Convention . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28<br />

CITES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30<br />

World Heritage Convention . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30<br />

EC Habitats Directive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30<br />

The Natura 2000 Network.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31<br />

Convention on Biological Diversity . . . . . . . . . . . .32<br />

Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33<br />

Alien Species. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33<br />

Biodiversity and Tourism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .34<br />

Climate Change and Biodiversity . . . . . . . . . . . . . .34<br />

Ecosystem Approach. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .34<br />

Global Strategy for Plant Conservation.. . . . . . . . .35<br />

Global Taxonomy Initiative.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .35<br />

Impact Assessment, Liability and Redress. . . . . . .35<br />

Indicators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .36<br />

Protected Are<strong>as</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .36<br />

Public Awareness and Education.. . . . . . . . . . . . .36<br />

Sustainable use of Biodiversity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37<br />

2010 Biodiversity Target . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37<br />

3) Key Species & Habitats. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41<br />

4) Habitats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51<br />

Terrestrial Habitats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .52<br />

1 Upper Rock Nature Reserve.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .52<br />

2 Cliffs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55<br />

3 Lower Slopes and Buffer Zone.. . . . . . . . . . . . .59<br />

4 Talus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62<br />

5 Great Sand Slopes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .66<br />

6 The Isthmus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .72<br />

7 South District . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .74<br />

8 Urban Green Are<strong>as</strong>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .81<br />

9 Urban Are<strong>as</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84<br />

10 Caves. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .89<br />

Marine Habitats . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .93<br />

11 Intertidal Zone . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .96<br />

12 Artificial Reefs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .99<br />

13 Reefs & Inshore rocky outcrops . . . . . . . . . .101<br />

13 Sand.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .103<br />

14 Marl . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .105<br />

15 Rock . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .106<br />

5) Species Action Plans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..109<br />

Birds . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .110<br />

Mediterranean Shag . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .110<br />

Lesser Kestrel.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .112<br />

Peregrine Falcon. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .113<br />

Barbary Partridge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .115<br />

Eur<strong>as</strong>ian Eagle Owl. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .116<br />

Mammals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .118<br />

All Cetaceans.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .118<br />

Barbary Macaque . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .120<br />

Red Fox . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .122<br />

European Rabbit. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .123<br />

Soprano Pipistrelle.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .124<br />

Schreiber’s Bat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125<br />

Flowering Plants. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .126<br />

All Orchids.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .126<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Chickweed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .128<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Campion.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .129<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Thyme . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .130<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Restharrow.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .131<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Sea Lavender.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .132<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Candytuft. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .134<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Saxifrage. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .135<br />

Sweet Bay or Laurel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .136<br />

Narrow-leaved Ash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .137<br />

Buprestis (Yamina) sanguinea ssp. calpetana . .138<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Funnel-web Spider . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .139<br />

Acicula norrisi.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .140<br />

Oestophora calpeana. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .141<br />

Mediterranean Ribbed Limpet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .142<br />

6) Alien, Inv<strong>as</strong>ive & Pest Species. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .145<br />

Alien Inv<strong>as</strong>ive Flora . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .148<br />

Rooikrans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .149<br />

Orange or Golden Wreath Wattle . . . . . . . . . . . .151<br />

Pinwheel & Tree Houseleek . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .152<br />

Century Plants. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .153<br />

Tree of Heaven . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .155<br />

Tree Aloe & Soapy Aloe. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .156<br />

Hottentot Fig . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .158<br />

African Cornflag. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .161<br />

Purple Dewplant. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .162<br />

Bush Lantana or Shrub Verbena . . . . . . . . . . . . .163<br />

Shrub Tobacco . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .164<br />

Prickly Pear . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .165<br />

Bermuda Buttercup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .168<br />

Cape Wattle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .169<br />

Kikuyu Gr<strong>as</strong>s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .171<br />

Cape Ivy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .172<br />

N<strong>as</strong>turtium. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .174<br />

Spineless Yucca . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .175<br />

Pest Species. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .176<br />

Bear’s Breech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .176<br />

Black Rat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .177<br />

Feral Cat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .179<br />

Goat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .180<br />

Feral Pigeon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .182<br />

Yellow-legged Gull.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .184<br />

7) References & Glossary<br />

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .189<br />

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .192<br />

Contents<br />

- 3 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 4 -<br />

Foreword<br />

The variety of plants and animals with which we share <strong>Gibraltar</strong> is truly remarkable. More and more<br />

people are aware of this, but somehow I get the feeling that fewer and fewer get to experience it for themselves.<br />

This is a problem. Lack of familiarity with the actual plants and animals that live around us means that<br />

decision makers – from the developer and planner who formulates a project, or the politician who approves<br />

it, to the builders who cut down the bush or disturb the nest – need to be constantly reminded of th consequence<br />

of their actions, when really they should be so aware of these that their decisions will be strongly<br />

influenced accordingly.<br />

Having experts at hand is not good enough. They may forget to consult them, or decide, whether they<br />

admit or not, to act regardless of advice. The only real way to ensure that the diversity of living things persists<br />

and flourishes is for those on the front line to wish this to be so. And for that they need the knowledge.<br />

Armed with that, it’s not so difficult. Often slight changes in plan will have the desired effect. At other<br />

times ide<strong>as</strong> that seemed good may have to be significantly changed, or even abandoned.<br />

The possible loss of biological diversity is one of the greatest environmental problems facing <strong>Gibraltar</strong>,<br />

together, of course, with the problem of incre<strong>as</strong>ing demands on energy.<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society (GONHS) h<strong>as</strong> since its beginnings thirty years<br />

ago, been at the helm of enjoying our biodiversity (well before we called it that) and protecting and enhancing<br />

it.<br />

It w<strong>as</strong> therefore logical that now, at this point in <strong>Gibraltar</strong>’s journey through its history, it should synthesise<br />

the wealth of knowledge it h<strong>as</strong> accrued and provide a Plan that will serve to achieve these aims. We<br />

produce this on the year of our 30 th Anniversary, in <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Biodiversity Year, a year too with other, political<br />

landmarks. Political and constitutional progress, which is occurring in <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>as</strong> I write, h<strong>as</strong> to go<br />

hand in hand with <strong>as</strong>suming responsibility for international obligations, with includes obligations to the environment<br />

in general and biodiversity in particular.<br />

Biodiversity Conservation is also incre<strong>as</strong>ingly a theme and an aim for organisations around the world,<br />

not le<strong>as</strong>t the UK’s Overse<strong>as</strong> Territories and other small are<strong>as</strong> or regions.<br />

Charlie Perez’s work sets out the b<strong>as</strong>is for biodiversity conservation in <strong>Gibraltar</strong>, giving its background,<br />

its international context, and then, while including a wealth of information, succinctly states what h<strong>as</strong> to be<br />

done.<br />

While GONHS will continue to work to ensure that these principles find their way into action, much of<br />

our collective work h<strong>as</strong> been done. We present the Biodiversity Action Plan, providing the b<strong>as</strong>is and throwing<br />

down the challenge to those who now need to put it into effect.<br />

John Cortes<br />

General Secretary<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society<br />

2006

Acknowledgements<br />

The author would like to thank the GONHS Biodiversity Team members Mr Leslie Linares, Mr Keith<br />

Bensusan and Dr. John Cortes for their <strong>as</strong>sistance in the many surveys of the different habitats that were<br />

undertaken during the initial research period. To Dr Eric Shaw and Mr Steven Warr for their useful comments<br />

on the Marine Habitats, to Mr Alex Menez for providing data and useful comments on the action<br />

plans on the terrestrial molluscs, to Dr Darren Fa and Dr Terence Ocaña for providing data and useful comments<br />

on the Mediterranean Ribbed Limpet.<br />

The author is in debt to Mr Keith Bensusan for his invaluable contribution in the analysis of the status<br />

of species in chapter 3 ‘Key Species and Habitats’ and to Mr Leslie Linares for his important contribution to<br />

the knowledge of the flora of <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

The author would also like to thank the Chief Fire Officer, Mr Louis C<strong>as</strong>ciaro for providing information<br />

on fire incidents, to the Committee of the <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Branch of the European Federation of Sea Anglers<br />

(EFSA) for their useful comments on the marine environment and fish species, and to the photographers<br />

Mr Leslie Linares, Mr Eric Shaw, Mrs Yvonne Benting, Dr John Cortes, Mr Albert Yome, Mr Julien Martinez,<br />

Miss Torborg Berge, Mr Bob Wheeler and the <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Tourist Board for the use of their photographs and<br />

to Miss Salli Menez for her fine drawings of the terrestrial molluscs. Distribution maps were produced using<br />

DMAP for windows version 7.1f by Alan Morton.<br />

Special thanks go to Wildlife (<strong>Gibraltar</strong>) for providing the office and equipment within the <strong>Gibraltar</strong><br />

Botanic Gardens at the Alameda to enable the production of the report.<br />

The work involved in the production of this report w<strong>as</strong> funded by the Overse<strong>as</strong> Territories Environment<br />

Programme (OTEP) of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Thanks go to Denise Dudgeon and Rebecca<br />

Claxton for their help and support in the administration of the Programme.<br />

Thanks are also due to Dr Mike Pienkowski and to Frances Marks of the United Kingdom Overse<strong>as</strong><br />

Territories Conservation Forum for their encouragement and support.<br />

Finally the author would like to express his gratitude to Mr Keith Bensusan, Dr. John Cortes, Dr. Ernest<br />

Garcia and Mr Leslie Linares for their invaluable help in checking the manuscript.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

- 5 -

1. Introduction

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 8 -

1. Introduction<br />

The ‘Convention on Biological Diversity’ w<strong>as</strong> signed in 1993 and ratified by forty-three countries, including<br />

the United Kingdom. <strong>Gibraltar</strong>, <strong>as</strong> part of this member state, w<strong>as</strong> obliged to adopt this, but initially did<br />

not take an active part in the implementation of the objectives of the Convention. In 2003, the <strong>Gibraltar</strong><br />

<strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society, realising the need to address some of these objectives, and with<br />

an active b<strong>as</strong>e of naturalists and scientists and knowledge of the requirements, launched an initiative to catalogue<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong>’s wildlife at a taxonomic level. The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Biodiversity Project w<strong>as</strong> launched by GONHS<br />

on 28 th January 2004, and formed the initial step in bridging the gaps in our knowledge of the Biodiversity<br />

of our territory. As part of this initiative, a proposal for funding w<strong>as</strong> submitted to the UK Overse<strong>as</strong> Territories<br />

Environment Programme of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office for the preparation of a Biodiversity<br />

Action Plan for <strong>Gibraltar</strong>. This would encomp<strong>as</strong>s, not only the ongoing taxonomic <strong>as</strong>sessments of the<br />

Biodiversity of the territory, but also the need to identify are<strong>as</strong> at risk, encourage alternative sustainable use<br />

and development, and more importantly create public awareness and participation, at all levels, on the significance<br />

of Biodiversity <strong>as</strong> a strategic tool in the field of conservation. The bid w<strong>as</strong> successful, and the<br />

author of this report w<strong>as</strong> engaged in August 2004 to prepare such a Plan.<br />

This document is b<strong>as</strong>ed on the UK’s Biodiversity Action Plan that w<strong>as</strong> produced in 1995 under the headings<br />

‘Biodiversity: The UK Steering Group Report. Volume I: Meeting the Rio Challenge’ and ‘Volume II:<br />

Action Plans’ (HMSO 1995).<br />

The Plan provides the background to the meaning and importance of Biodiversity at a global scale and,<br />

using the UK Biodiversity Action Plan <strong>as</strong> a b<strong>as</strong>is, translates this to the territory of <strong>Gibraltar</strong> and puts into<br />

perspective the objectives and the requirements for making this Biodiversity Action Plan an operational success.<br />

The report analyses historical accounts of <strong>Gibraltar</strong>’s environment and diversity of wildlife, and<br />

describes the ‘progress’ and expansion of the human population and urbanisation through the centuries.<br />

The ‘Habitats’ chapter covers our two main ecosystems - the terrestrial and the marine - both of which<br />

are divided into distinct sites and habitat types, each with its unique species <strong>as</strong>sociations. Each h<strong>as</strong> its own<br />

action plan that describes the current status of the habitat and factors affecting its welfare, including existing<br />

and potential threats, and the action required to remedy them. Another section stresses the need for<br />

public awareness and involvement in Biodiversity Conservation at all levels, from an educational standpoint<br />

to all other sectors of the community.<br />

The ‘<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Biodiversity Project’ aims to catalogue <strong>as</strong> much of the flora and fauna of <strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>as</strong> possible,<br />

in order to be able to <strong>as</strong>sess the conservation requirements of species and habitats accurately. This<br />

document emph<strong>as</strong>ises the need for constant monitoring and research and invites public participation in the<br />

‘<strong>Gibraltar</strong> Biodiversity Project’. It contains species lists for some of our flora and fauna and categorises<br />

those species according to their conservation status and requirements. The document lists the serious<br />

threats to our Biodiversity and addresses these in the Action Plan, where each particular problem is<br />

addressed and remedial proposals, recommendations and targets are presented.<br />

What is Biodiversity?<br />

In the l<strong>as</strong>t quarter of the 20 th century, scientists were extremely worried at the rate of deforestation that w<strong>as</strong><br />

taking place on a global scale, particularly in tropical regions. The tropical rainforests were known to hold the<br />

highest number of species per unit area in the world but, with the continual loss of habitat, a great many were<br />

being lost even before they could be described. There w<strong>as</strong> a need to quantify the total number of species of<br />

plants and animals in every region of the world, at local, regional and global levels. An <strong>as</strong>sessment of Global<br />

Biodiversity also had to take into account natural communities and habitats, since these are crucial to the<br />

preservation of Biodiversity and serve <strong>as</strong> indicators of ecological change. The b<strong>as</strong>ic requirement to identify<br />

and catalogue species within particular habitats and ecosystems, to <strong>as</strong>sess species richness and diversity and<br />

identify this diversity within natural communities, gave form to the term ‘Biological Diversity’, or <strong>as</strong> we now<br />

know it ‘Biodiversity’.<br />

The Oxford Dictionary of Ecology (Allaby, 1998) gives the meaning of Biodiversity <strong>as</strong> ‘A portmanteau<br />

term, which gained popularity in the late 1980s, used to describe all <strong>as</strong>pects of biological diversity, especially<br />

including species richness, ecosystem complexity, and genetic variation’. The meaning of<br />

Biodiversity, given in A Dictionary of Entomology (2001) is ‘The condition of being different biologically‘. It<br />

also quotes several definitions for this term from different scientists and organisations, which are repro-<br />

Introduction<br />

- 9 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 10 -<br />

duced here to enable a clearer understanding of the term.<br />

1. ‘…the variety of the world’s organisms, including their<br />

genetic diversity and the <strong>as</strong>semblages they form. A blanket<br />

term for the natural biological wealth that undergirds human life<br />

and well-being. The breadth of the concept reflects the interrelatedness<br />

of genes, species and ecosystems.’ (Reid & Miller<br />

1989).<br />

2. ‘The variety of living organisms considered at all levels,<br />

from genetics through species, to higher taxonomic levels, and<br />

including the variety of habitats and ecosystems’ (Meffe &<br />

Carroll).<br />

3. ‘…the variety and variability of living organisms and the<br />

ecological complexes in which they occur.’ OTA.<br />

Yet another definition that serves to clarify the complexities of biodiversity can be found in Reaka-Kudla<br />

et al. (1997):<br />

‘Biodiversity is defined <strong>as</strong> all heredity-b<strong>as</strong>ed variation at all<br />

levels of organisation, from the genes within a single population<br />

or species, to the species composing all or part of a local community,<br />

and finally to the communities themselves that compose<br />

the living parts of the multifarious ecosystems of the world.’<br />

We can see from the various meanings and interpretations that the key elements of Biodiversity are<br />

species richness, ecosystems and genetic variability. These three elements are therefore the b<strong>as</strong>is for<br />

much of the coordinated work of scientists around the world to establish the biological wealth within ecosystems<br />

and thereby consolidate conservation efforts aimed, not only at protecting the natural environment but<br />

also at making its sustainable use possible. Our long-term survival depends on it.<br />

Nevertheless the number of species that exists globally is unknown. Some estimate the total number<br />

of species at between 5 and 30 million (HMSO 1995), while others believe it to be between 10 and100 million<br />

(Reaka-Kudla et al. 1997). We can see from these figures a remarkable disparity, which emph<strong>as</strong>ises<br />

the level of our current knowledge.<br />

1,6%<br />

2,4%<br />

1,6%<br />

0,4%<br />

6,7%<br />

7,7%<br />

3,2%<br />

4,0%<br />

64,4%<br />

Bacteria<br />

Virsus<br />

Insects<br />

Protozoa<br />

Algae<br />

Plants<br />

Vertebrates<br />

Other invertebrates<br />

Other arthropods<br />

Figure 1. Estimated percentage of species from different groups of organisms thought to exist, <strong>as</strong><br />

a proportion of the global total. (Source: ‘Biodiversity: The UK Steering Group Report’. (1995)).

Notwithstanding this, some countries have achieved substantial progress in cataloguing their<br />

Biodiversity. This is particularly useful when applying these same findings towards Biodiversity action<br />

plans. In the United Kingdom, <strong>as</strong> elsewhere, microbial organisms such <strong>as</strong> bacteria and protozoa are less<br />

well known than invertebrates. However, the larger, more visible and attractive taxonomic groups, such <strong>as</strong><br />

flowering plants and vertebrates have been intensively studied and have received more attention. Many<br />

British invertebrate groupings have also been studied intensively but every taxonomic group deserves<br />

equal attention.<br />

A sound knowledge of local faun<strong>as</strong> is essential for conserving native species. Some require monitoring<br />

to <strong>as</strong>sess their specific requirements, establish their populations and determine their status at local and<br />

national levels. This can only be done by identifying which habitats they occupy and the threats that these<br />

are subject to, which can then be addressed.<br />

Table 1: Numbers of terrestrial and freshwater species in the UK compared<br />

with recent global estimates of described species in major groups.<br />

Group British species World species<br />

Bacteria Unknown >4,000<br />

Viruses Unknown >5,000<br />

Protozoa >20,000 >40,000<br />

Algae >20,000 >40,000<br />

Fungi >15,000 >70,000<br />

Ferns 80 >12,000<br />

Bryophytes 1,000 >14,000<br />

Lichens 1,500 >17,000<br />

Flowering Plants 1,500 >250,000<br />

Non-arthropod invertebrates >4,000 >90,000<br />

Insects 22,500 >1,000,000<br />

Arthropods other than insects >3,500 >190,000<br />

Freshwater fish 38 >8,500<br />

Amphibians 6 >4,000<br />

Reptiles 6 >6,500<br />

Breeding birds 210 9,881<br />

Wintering birds 180 n/a<br />

Mammals 48 4,327<br />

Total c.88,000 c.1,770,000<br />

Source: - ‘Biodiversity: The UK Steering Group Report’. (1995).<br />

It is necessary to realise that Biodiversity, although <strong>as</strong>sociated with species diversity to a great degree,<br />

also encomp<strong>as</strong>ses the interrelationship between species and their habitat. This link is of vital importance<br />

since it is what h<strong>as</strong> promoted the gradual evolution through time of new varieties and species. So far, this<br />

natural process h<strong>as</strong> only been disrupted occ<strong>as</strong>ionally through abrupt but natural climatic changes, some of<br />

them resulting from cat<strong>as</strong>trophic events such <strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong>teroid impacts. However, we are now aware that today,<br />

global Biodiversity is gravely threatened by human activity.<br />

The realisation that biodiversity is declining, noted by scientists all around the world, prompted many<br />

countries to take action. This led to the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992, where the Convention<br />

on Biodiversity w<strong>as</strong> established.<br />

The Biodiversity Convention.<br />

The term ‘BioDiversity’, <strong>as</strong> it w<strong>as</strong> initially written, w<strong>as</strong> first used during the ‘National Forum on<br />

BioDiversity’, held in W<strong>as</strong>hington during September 1986, under the auspices of the National Academy of<br />

Sciences and the Smithsonian Institution (Reaka-Kudla et al. 1997). In 1992, at the Earth Summit in Rio<br />

de Janeiro, 167 countries became signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity, and by 1993, 41<br />

countries had ratified it. This w<strong>as</strong> the first time that a large majority of the world’s states had come togeth-<br />

Introduction<br />

- 11 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 12 -<br />

er and agreed on a legal instrument that would commit them to using biological resources sustainably and<br />

conserving biodiversity. This Convention had global perspectives. All the states realised that the problems<br />

that affect the global environment have to be addressed by all countries of the world for the benefit, and<br />

indeed survival, of mankind.<br />

The three main objectives of the Convention are in Article 1:<br />

• the conservation of biodiversity at the genetic, species and ecosystem levels.<br />

• the sustainable use of its components; and<br />

• the fair and equitable sharing of benefits derived from the use of genetic<br />

resources.<br />

The United Kingdom w<strong>as</strong> a signatory of the Convention on Biological Diversity and <strong>Gibraltar</strong>, <strong>as</strong> a territory<br />

of the UK, is obliged to adopt the Convention and comply with and enforce its goals and objectives.<br />

The United Kingdom launched ‘Biodiversity: The UK Action Plan’ in January 1994, and established representatives<br />

for a Biodiversity Steering Group from key sectors chaired by the Department of the Environment<br />

who would oversee the following t<strong>as</strong>ks: -<br />

• Developing costed targets for key species and habitats.<br />

• Suggesting ways of improving the accessibility and coordination of information on<br />

Biodiversity.<br />

• Recommending ways of incre<strong>as</strong>ing public awareness and involvement in conserving<br />

Biodiversity.<br />

• Recommending ways of ensuring that commitments in the plan were properly<br />

monitored and carried out; and<br />

• Publishing findings before the end of 1995.<br />

The Group w<strong>as</strong> selected to represent regional and local Government from private and public sectors,<br />

academic bodies, collections, business, agriculture, landowners, and conservation NGOs. Primarily in an<br />

advisory capacity, the proposals contained within the report were then submitted to Government for action<br />

(HMSO 1995).<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

The United Kingdom, with responsibility for <strong>Gibraltar</strong>, published these findings in their ‘Biodiversity: The<br />

UK Steering Group Report’ Volumes I and II (HMSO 1995), where they refer to <strong>Gibraltar</strong> in ‘Annex B’ under<br />

the ‘Dependent Territories Progress Report’.<br />

Figure 2: <strong>Gibraltar</strong> viewed from the south. Courtesy <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Tourist Board.

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> figures in the UK Steering Group Report <strong>as</strong> ecologically significant and sensitive, stemming<br />

from its location on a major migration route, with very substantial flora for its area and important marine biological<br />

<strong>as</strong>sets, but vulnerable because of its small area with a high population. The Steering Group recognised<br />

the sound, scientifically b<strong>as</strong>ed work that h<strong>as</strong> been carried out in <strong>Gibraltar</strong> over a number of years and<br />

they welcome the implementation of the ‘Nature Protection Ordinance, 1991’ and the creation of the Upper<br />

Rock Nature Reserve, together with transposition of EU directives. They also state that <strong>Gibraltar</strong> h<strong>as</strong> implemented<br />

the Habitats Directive (the Directive h<strong>as</strong> been transposed into the laws of <strong>Gibraltar</strong> (Part II A, LN<br />

118 of 1995), but the designation of Natura 2000 sites is pending).<br />

The report recognises the excellent human resources backing the conservation efforts in the form of the<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> <strong>Ornithological</strong> & <strong>Natural</strong> History Society and the partnership that exists between this organisation<br />

and the <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Government, providing expert advice and preparing reports. It also mentions that<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> w<strong>as</strong> being considered <strong>as</strong> a location for one of the global Geographical Observatories under a programme<br />

initiated by the Royal Geographical Society, and refers to lack of funding for biodiversity conservation<br />

<strong>as</strong> the main problem facing <strong>Gibraltar</strong> in this context.<br />

The Significance of Biodiversity.<br />

We have discussed the meaning of Biodiversity and how numerous countries worldwide are now committed<br />

to improving the quality and quantity of their fauna and flora, in order to ensure that future generations<br />

will be able to inherit a healthy environment. However, during the recent history of mankind the uncontrolled<br />

use, and in many c<strong>as</strong>es the abuse of the Earth’s ecosystems, have led to a degradation of the land,<br />

the se<strong>as</strong> and the air. Species-loss h<strong>as</strong> been severe and irreversible in every part of the globe, and mankind<br />

h<strong>as</strong> largely ignored the interdependency of living organisms, leading to a collapse in the balance of nature<br />

and an impoverishment of biological resources for the future.<br />

The use and abuse of unsustainable resources h<strong>as</strong> resulted in many natural cat<strong>as</strong>trophes around the<br />

world including incre<strong>as</strong>ed desertification in many are<strong>as</strong> and the depletion of the ozone layer over both<br />

poles. It h<strong>as</strong> also led to the realisation that mankind is affecting the weather systems through climatic<br />

change, including global warming, leading to sudden short term alterations in ecosystems that are too rapid<br />

for evolutionary adjustments to keep up. If such climate change is allowed to continue, this will eventually<br />

result in dramatic loss of biodiversity.<br />

Humans are dependent on the terrestrial and marine environments for all our requirements. However,<br />

the incre<strong>as</strong>ing demands placed on these ecosystems and the continued growth of the human population<br />

h<strong>as</strong> placed incre<strong>as</strong>ed pressures to augment the rate of production of commodities. This h<strong>as</strong> resulted in the<br />

loss of much of our natural environment, and h<strong>as</strong> brought about the realisation by many that if we do not<br />

conserve our Biodiversity, the long-term future of the human species will be in doubt.<br />

So why conserve Biodiversity?<br />

1) Primarily we have an obligation to future generations. We have created most of the recent<br />

dramatic changes in our ecosystems and, <strong>as</strong> custodians, are responsible for ensuring that<br />

these same ecosystems do not suffer continual degradation and that the biodiversity of these<br />

systems is conserved.<br />

2) There are also ethical and aesthetic implications. The environment, together with its habitats<br />

and species living within the same, enriches our lives in a variety of ways. We have all<br />

heard our older relatives say at one time or another, “I remember how beautiful this place<br />

used to look like, before it …”<br />

3) Each species h<strong>as</strong> a particular value and plays a particular role in nature. Many animals and<br />

plants are directly useful to us and ever more beneficial species are steadily being discovered.<br />

Crop plants and domestic animals are the most obvious examples. In addition, there<br />

are those which rid us of pests that would otherwise eat our crops or spread dise<strong>as</strong>e. Others<br />

provide us with medicinal remedies for a multitude of ailments. Still more provide building<br />

material, act <strong>as</strong> water filters or prevent erosion. A whole range of bacteria and plant species<br />

are vital to the nutrient cycles, such <strong>as</strong> the circulation of nitrogen, which make any life on<br />

earth possible. Green plants provide us with the very oxygen we breathe.<br />

Introduction<br />

- 13 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 14 -<br />

4) Biodiversity h<strong>as</strong> direct economic value. The development of national Parks and nature<br />

reserves around the world and incre<strong>as</strong>ing interest in the wildlife h<strong>as</strong> generated the industry<br />

of Ecotourism, which is bringing great economic benefits to many countries.<br />

Threats to Biodiversity<br />

Many major threats worldwide affect Biodiversity. The most important ones include:<br />

• Overpopulation: leading to ever-incre<strong>as</strong>ing demands for food, water and living space, and<br />

incre<strong>as</strong>ed pollution, all at the expense of natural environments.<br />

• Habitat destruction, especially deforestation<br />

• Greenhouse g<strong>as</strong> emission: of carbon dioxide and methane, potentially contributing to global<br />

warming including climate change.<br />

• Over-harvesting of potentially sustainable resources: over-fishing especially.<br />

• Urbanisation of natural habitats<br />

• Non-sustainable use of water.<br />

• Loss of genetic diversity among crop plants and animals.<br />

• Impacts of alien species on indigenous communities: the extinction of island bird communities<br />

by introduced rats and snakes is a prime example.<br />

• Trade in endangered species: such <strong>as</strong> tigers and rhinoceroses, and in their products: such<br />

<strong>as</strong> ivory and whale-meat.<br />

The two most notable are habitat loss and pollution. These issues are most frequently <strong>as</strong>sociated with<br />

the felling and burning of tropical forests and the emission of greenhouse g<strong>as</strong>es into the atmosphere.<br />

These two account for the most significant changes that have occurred recently. The results of the<br />

g<strong>as</strong>es and the depletion of the large m<strong>as</strong>ses of oxygen-producing forests have resulted in a slight but significant<br />

incre<strong>as</strong>e in the temperature of the planet. This h<strong>as</strong> led to substantial changes in some ecosystems.<br />

Glaciers have retreated and in some places disappeared altogether. The ice-sheets around the poles have<br />

been gradually thinning and shrinking. Temperatures in the waters of the e<strong>as</strong>t Pacific show an incre<strong>as</strong>e<br />

that affects the fluctuations that give rise to the phenomena called ‘El Niño’ and ‘La Niña’. Their power<br />

appears to have intensified <strong>as</strong> a result of this incre<strong>as</strong>e, and this h<strong>as</strong> been the cause of torrential rains in<br />

co<strong>as</strong>tal South America, while at the same time causing the failure of the monsoon rains in the Indian subcontinent,<br />

and extensive droughts in e<strong>as</strong>tern Australia triggering immense forest fires. Temperature<br />

incre<strong>as</strong>es in the mid Atlantic have spawned larger, more frequent and more ferocious hurricanes affecting<br />

the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and the southern states of the United States. Likewise there h<strong>as</strong> been<br />

an incre<strong>as</strong>e in the quantity and ferocity of typhoons affecting the e<strong>as</strong>tern seaboard of Asia (IPCC 2001).<br />

These are some of the major ‘natural cat<strong>as</strong>trophes’ that make the headlines. Each causes human<br />

tragedies, destruction, homelessness, strife, starvation, dise<strong>as</strong>es and general despair. It is usually me<strong>as</strong>ured<br />

in countless millions of dollars, but that only quantifies the human losses. What about the irreparable<br />

losses to habitats and the deaths of whole communities of plants and animals? These never make the<br />

headlines, but the tragedy is just <strong>as</strong> serious and in many c<strong>as</strong>es worse. Agricultural and farming practices<br />

rely on ecological conditions, and these may be affected by a loss of habitats and biodiversity.<br />

This is the time for mankind to wake up and realise that we are not alone on this planet. That the planet<br />

is not endowed with an infinite supply of raw materials and that our actions have far more long-term<br />

effects than we ever realised.<br />

It is only in the l<strong>as</strong>t 30 years that we have begun to realise that the continual harvesting of certain commodities<br />

h<strong>as</strong> exceeded the natural regeneration rate. This h<strong>as</strong> resulted in the depletion of certain species,<br />

one of which led to the infamous ‘Cod Crisis’ in North Atlantic waters in the 1970’s and the establishment<br />

of a quota system, which h<strong>as</strong> nevertheless been unsuccessful, due to unscrupulous fishing practices and<br />

quota byp<strong>as</strong>sing elements (Nielsen & Mathiesen 2003). Another example is the uncontrolled felling of hardwood<br />

timber and the establishment of import bans which many countries do not apply or enforce, while others<br />

turn a blind eye, and encourage the countries of origin to part with their rich tropical forests. These are<br />

just some examples that have driven major countries to adopt a policy of sustainability, in which stocks of<br />

certain commodities will only be harvested on the b<strong>as</strong>is that there will always be sufficient left to ensure that<br />

future stocks are <strong>as</strong>sured.<br />

There are also the threats to habitats, where building pressures for development and the expansion of

major towns and cities have sown the destruction of many of our green are<strong>as</strong> and wetland habitats. If we<br />

take into account that during the early part of the l<strong>as</strong>t millennium most of the transport system consisted of<br />

either horse-drawn carriage or waterborne vessels, and this l<strong>as</strong>t method w<strong>as</strong> the most efficient, it is then<br />

not surprising that most towns and cities were located on major waterways and co<strong>as</strong>tal locations. The<br />

rivers acted not only <strong>as</strong> navigational routes but also for the provision of water and the disposal of effluent.<br />

Over the centuries these cities have grown, taking in the flat terrain of the riversides and floodplains to<br />

expand. Cities like London have taken up an enormous area of the Thames valley and with it industrial<br />

sites have benefited from the proximity to rivers, initially to run machinery and dump w<strong>as</strong>te but mainly <strong>as</strong> a<br />

transport waterway. These rivers have been polluted to a great extent, diminishing the wildlife of these wetland<br />

ecosystems. Marshes have been drained, peat bogs have been cleared and estuaries have been<br />

reclaimed and their rivers channelled. There h<strong>as</strong> been a dr<strong>as</strong>tic reduction of wetlands in the northern hemisphere<br />

in the l<strong>as</strong>t 200 years, with a large percentage of these extremely diverse habitats disappearing in<br />

recent times, to be turned over to agriculture.<br />

Unsound agricultural practices, with mounting pressures to incre<strong>as</strong>e demand for an expanding population<br />

have resulted in rampant deforestation and destruction of natural habitats. In many are<strong>as</strong>, only small<br />

pockets of isolated natural are<strong>as</strong> that are unsuitable for farming remain. These are insufficient to contain a<br />

viable thriving community of plants and animals, and studies have shown that small, isolated populations<br />

do not survive for very long. Monoculture techniques over large are<strong>as</strong> have also limited the variability of<br />

species and have opened up a niche for pest species to target. Ironically, this h<strong>as</strong> led to unnatural control<br />

with pesticides and herbicides that have wiped out not only the pest species, but other beneficial species<br />

that could have been used <strong>as</strong> a natural control. Here again we see the destruction of Biodiversity at the<br />

level of habitats and species without consideration for the future exploitation of these resources, and carried<br />

out in a totally unsustainable manner.<br />

There is also the use of unsustainable energy sources in the form of fossil fuels, which are extracted<br />

from the mantle of the planet, leaving behind profound scars in the landscape and contaminating everything<br />

it comes into contact with. The extraction of coal in the early 20 th century gave way to oil when it<br />

became apparent that resources of the latter were uneconomical to extract and running low. The industrial<br />

revolution in the 1800’s spurred the need for unlimited supplies of fuel, which in turn produced the smogladen<br />

air of that time and initiated the contamination of the earth’s atmosphere. When oil replaced coal,<br />

industry had already evolved at a relentless pace, and with the invention of the combustion engine, oil and<br />

its derivatives became the answer to the world’s energy problems.<br />

Although essential at the time for the modernisation of society, the unrelenting use of unsustainable<br />

energy resources h<strong>as</strong> invariably affected Biodiversity through contamination and pollution of many natural<br />

ecosystems. It is time for mankind to seek more environmentally stable and sustainable renewable forms<br />

of energy to redress this loss.<br />

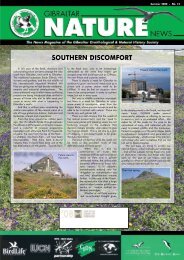

Figure 3: Atmospheric pollution from the Spanish Refinery to the north of <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

Introduction<br />

- 15 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 16 -<br />

The introduction of alien and/or inv<strong>as</strong>ive species is another <strong>as</strong>pect that h<strong>as</strong> seriously affected the<br />

Biodiversity of our planet. In the age of discovery, when adventurers set sail to discover new lands, they<br />

took with them cats to control vermin, namely the black rat, Rattus rattus, that regularly travelled on these<br />

ships. Both these species were to find their way onto dry land, in are<strong>as</strong> of the world that were b<strong>as</strong>ically virgin<br />

territory to these two species. Here, without any natural controlling factors, the two proliferated and<br />

preyed on or excluded the native species. In many parts of the world these two species have exterminated<br />

and caused the extinction of the most number of species, other than man. In New Zealand, where there<br />

w<strong>as</strong> a rich native population of flightless birds, cats and rats took an immense toll on the avifauna, completely<br />

exterminating many species. Even today there are certain islands in the Pacific Ocean where there<br />

is a current extermination programme of cats and rats, in order to save the native population of seabirds.<br />

There are many other similar examples.<br />

We can see the damage done to ecosystems when there are no natural predators to control animals,<br />

but what can one do when the alien species is not an animal but a plant? Few people realise the problems<br />

that an inv<strong>as</strong>ive plant can cause, yet the introduction of plant species in an area where there again is no<br />

natural controlling factor, is a recipe for dis<strong>as</strong>ter. It w<strong>as</strong> common practise for the sailors returning from exotic<br />

locations to bring back colourful and exotic plants and flowers. Many did not survive the harsh northern<br />

European climate except in greenhouses, under artificial conditions. Yet some fared better and proliferated<br />

escaping through wind blown seed and other means into the wild, where they established successful<br />

colonies and pushed out native species. An example can be found in the UK where the Rhododendron,<br />

Rhododendron ponticum h<strong>as</strong> invaded and become a pest species.<br />

These are some of the major threats that affect our Biodiversity. Some are spurred on by necessity, for<br />

want of a mouthful today, others through greed. Nevertheless many threats occur through ignorance: ignorance<br />

of the fact that what we do <strong>as</strong> an individual will not affect all of us on this planet. Yet we are all linked<br />

together in one way or another, from the smallest virus and bacterium to the largest animals. We humans<br />

often believe that we are leaders in the evolutionary ladder. But a leader h<strong>as</strong> responsibilities, and since we<br />

have created most of the dramatic changes that have taken place on our planet we have a moral obligation<br />

to put this right.<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Action Plan<br />

This Plan highlights the importance of biodiversity in <strong>Gibraltar</strong> and aims to provide specific habitat and<br />

species action plans that will address the overall goal for <strong>Gibraltar</strong>’s Biodiversity requirements. This is:<br />

“To conserve and enhance biological diversity within<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong> and to contribute to the conservation of global<br />

biodiversity through all appropriate mechanisms.”<br />

The objectives of the Biodiversity Action Plan, within both our terrestrial and marine ecosystems, are<br />

therefore:<br />

• To sustain the existing biodiversity of natural and semi-natural habitats where<br />

this h<strong>as</strong> been declining.<br />

• To conserve internationally important, threatened and vulnerable species and habitats.<br />

• To sustain the populations and distribution of native species.<br />

• To conserve and improve the quality of natural habitats.<br />

• To incre<strong>as</strong>e total biodiversity, by reintroducing locally extinct species.<br />

• To restore natural habitats by controlling and eradicating alien species.<br />

The <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Biodiversity Project will establish and identify key species and habitats and will<br />

provide the b<strong>as</strong>es for the necessary nature conservation programmes and t<strong>as</strong>ks. These will<br />

need to be tackled by the <strong>Gibraltar</strong> Government and their agencies, in consultation and in partnership<br />

with existing environmental NGO’s and will require the collaboration of developers and<br />

other stakeholders.<br />

The programmes will require costed targets for threatened species and habitats that will include research<br />

and monitoring, incre<strong>as</strong>ing public awareness and involving other key sectors.<br />

Such programmes will address the requirements for conserving the biodiversity of <strong>Gibraltar</strong> and will<br />

reveal what is required to tackle other important environmental issues.

2. The International Context

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 18 -

2. The International Context<br />

The survival of much of Europe’s natural environment, its fauna, flora and habitats were under unremitting<br />

and incre<strong>as</strong>ing threats and all had deteriorated substantially by the mid to late 1900’s. One of the<br />

European Union’s primary t<strong>as</strong>ks w<strong>as</strong> to halt the incre<strong>as</strong>ing threats to habitats, prevent species loss, and<br />

protect and conserve Europe’s biodiversity. Through a continuous process of developing environmental legislation,<br />

with the application of European Directives addressing threatened species and habitats, and the<br />

establishment of networks of protected are<strong>as</strong>, the European Union and its Member States have come a<br />

long way in the process of achieving these objectives. Nevertheless this is an ongoing process that<br />

requires continual monitoring, evaluation and reporting, and one that benefits from public participation.<br />

Organisations such <strong>as</strong> the World Conservation Union (IUCN) are continually monitoring wildlife and have<br />

also <strong>as</strong>sessed the need to protect species at a global level and published the IUCN Red List Criteria. They<br />

have also made recommendations that have led to international agreements such <strong>as</strong> CITES (the<br />

Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species) that have been ratified by the United<br />

Kingdom and apply to <strong>Gibraltar</strong>. Birdlife International is another organisation that h<strong>as</strong> also <strong>as</strong>sessed the status<br />

of Europe’s avifauna in their publications Birds in Europe I (Tucker & Heath 1994) and Birds in Europe II<br />

and established two Important Bird Are<strong>as</strong> (IBAs) for <strong>Gibraltar</strong> (Birdlife International 2004). Their <strong>as</strong>sessment,<br />

and those of IUCN and other organisations dealing with the protection of wildlife on a global scale,<br />

complements EU Regulations and Directives by providing the mechanisms for the establishment of protected<br />

are<strong>as</strong> and the conservation of the habitats of endangered species.<br />

<strong>Gibraltar</strong>, <strong>as</strong> a European Territory of the Member State (the United Kingdom) which h<strong>as</strong> ratified these<br />

Conventions, Directives and Agreements, is obliged to conserve and protect its unique wildlife and habitats,<br />

and to implement the above me<strong>as</strong>ures.<br />

Several international instruments apply in part or in full to the Territory of <strong>Gibraltar</strong>. Some deal specifically<br />

with certain groups of animals: for example, the EU Wild Birds Directive, the Convention on Migratory<br />

Species (CMS) and EUROBAT that aims to protect all European bat species. Others incorporate the protection<br />

of habitats <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> defining priority species in need of conservation, and have given rise to a<br />

series of environmentally important are<strong>as</strong> within Member States that form or will form networks of protected<br />

are<strong>as</strong> under the name of ‘Natura 2000 Network’ or ‘The Emerald Network’. One particular agreement:<br />

‘ACCOBAMS’, which deals only with the conservation of cetaceans within the Black and Mediterranean<br />

se<strong>as</strong> and the adjacent part of the Atlantic Ocean, w<strong>as</strong> ratified by the United Kingdom in view of <strong>Gibraltar</strong>’s<br />

location and h<strong>as</strong> no direct relevance to the British Isles.<br />

This chapter explains the main provisions and objectives that deal with species and their habitat requirements<br />

within these Conventions and Directives and sets out how the relevant me<strong>as</strong>ures apply to <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

Table 1 lists the Conventions and agreements that have been ratified by the United Kingdom and that<br />

apply to <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

The International Context<br />

- 19 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 20 -<br />

Table 1: Main Environmental Conventions, Directives and Agreements<br />

dealing with wildlife that apply or have been transposed in <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

EU Birds Directive The Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds 79/409/EEC<br />

Bonn Convention Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of<br />

Wild Animals 82/461/EEC<br />

Bonn Convention Agreement on the Conservation of Populations of European Bats<br />

- EUROBATS<br />

ACCOBAMS Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black<br />

Sea, Mediterranean Sea and contiguous Atlantic area<br />

CITES The Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of<br />

Wild Flora and Fauna<br />

World Heritage The Convention concerning the Protection of the<br />

Convention World Cultural and <strong>Natural</strong> Heritage<br />

EC Habitats Directive The Conservation of <strong>Natural</strong> Habitats and Wild Fauna<br />

and Flora 92/43/EEC<br />

Natura 2000 Network A network of protected are<strong>as</strong> set up under the Birds and<br />

Habitats Directives<br />

Biodiversity Convention The Rio de Janeiro Convention on Biological Diversity<br />

93/626/EEC<br />

EU Birds Directive<br />

The European Unions’ Birds Directive came into force on 2 April 1979. It w<strong>as</strong> incorporated into the<br />

United Kingdoms Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 <strong>as</strong> the principle vehicle in implementing this Directive.<br />

The Directive is divided into two main parts: habitat conservation and species protection. For rare and<br />

endangered species the Directive recommends the creation of protected are<strong>as</strong> by the implementation of<br />

Special Are<strong>as</strong> of Protection (SPAs), with the appropriate management and the creation of new habitats and<br />

restoration of existing habitats.<br />

It also requests Member States to prohibit the deliberate killing of wild birds, damage to their nests or<br />

eggs, the taking or keeping of eggs of wild birds, and the keeping of wild birds and deliberate disturbance<br />

in their habitats especially during the breeding se<strong>as</strong>on.<br />

Box 1 lists the main provisions that deal specifically with the protection of birds and their habitats.<br />

1. Strictly for European wild birds and their habitats. Adapted from Birds in Europe (2004).<br />

EU Wild Birds Directive (79/409/EEC)<br />

• Article 1……. reports on the conservation of wild species of birds found naturally in the<br />

European territory of the Member States, and this applies to birds and includes their eggs, nests<br />

and their habitats.<br />

• Article 2……... calls for the Member State take adequate me<strong>as</strong>ures to maintain the stable population<br />

of the species referred to in Article 1 to a degree that incorporates the scientific, cultural<br />

and ecological requirements whilst taking into account economic and recreational requirements,<br />

or adapt the population of these species to that level.

• Article 4.1…… calls for the Member State to take special me<strong>as</strong>ures in habitat conservation to<br />

ensure the survival and reproduction of species listed in Annex I that are (a) in danger of extinction;<br />

(b) vulnerable to specific changes in their habitat; (c) considered rare, because of small<br />

populations or restricted local range; or (d) in need of particular attention, due to their specific<br />

requirement and nature of their habitat.<br />

• Member States are required to cl<strong>as</strong>sify suitable are<strong>as</strong> in number and size <strong>as</strong> ‘Special Protection<br />

Are<strong>as</strong>’ or SPAs, for the conservation of these species <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> regularly occurring migratory<br />

species, (covered in Article 4.2), taking into account their protection requirements in the terrestrial<br />

and marine are<strong>as</strong> where the Directive applies.<br />

• Monitoring the changes in trends and population levels are also required by the Directive for the<br />

purpose of evaluating the conservation of species within the Member States<br />

The Directive lists the 181 wild bird species that are cl<strong>as</strong>sified <strong>as</strong> in need of protection under Annex I.<br />

Annex I species of the Directive are the subject of special conservation me<strong>as</strong>ures to ensure their survival<br />

and reproduction in their are<strong>as</strong> of distribution. Member States also require to consider similar me<strong>as</strong>ures<br />

for regularly occurring migratory species not listed in Annex I, bearing in mind their need for protection in<br />

the geographical sea and land area where this Directive applies, <strong>as</strong> regards their breeding, moulting and<br />

wintering are<strong>as</strong> and staging posts along their migration routes.<br />

In <strong>Gibraltar</strong>, the Birds Directive w<strong>as</strong> incorporated under the Nature Protection Ordinance1991 (LN 11 of<br />

1991), which affords protection to all species of wild birds. Some of the wild birds that have been recorded<br />

in <strong>Gibraltar</strong>, <strong>as</strong> resident, summer or winter visitors, or on migration, include 88 species that are included in<br />

the Birds Directive under Annex I and these are the subject of European special conservation me<strong>as</strong>ures.<br />

They represent 48.6% of the bird species in Annex I. <strong>Gibraltar</strong> bird species that figure in Annex 1 are listed<br />

in Table 2.<br />

Table 2: Local status of bird species listed in Annex I of<br />

Council Directive 79/409/EEC that have been recorded in <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

Population<br />

Migratory<br />

Name Resident Breed Winter Stage<br />

Aegypius monachus 1-5i<br />

Alcedo atthis 1-5i 1-5i<br />

Alectoris barbara 50p<br />

Anthus campestris 11-50i<br />

Bubo bubo 1p<br />

Calandrella brachydactyla 1-5i<br />

Calonectris diomedea >10000i<br />

Caprimulgus europaeus 6-10i<br />

Chlidoni<strong>as</strong> niger 101-250i<br />

Ciconia ciconia 251-500i<br />

Ciconia nigra 11-50i<br />

Circaetus gallicus 251-500i<br />

Circus aeruginosus 101-250i<br />

Circus cyaneus 1-5i<br />

Circus pygargus 101-250i<br />

Emberiza hortulana 11-50i<br />

Falco columbarius 1-5i<br />

Falco eleonorae 6-10i<br />

Falco naumanni 11-15p 11-50i<br />

Falco peregrinus 6-10p<br />

Falco tinnunculus 5p 51-100i<br />

Gelochelidon nilotica 1-5i<br />

Gyps fulvus 51-100i<br />

Hieraaetus f<strong>as</strong>ciatus 1-5i<br />

Hieraaetus pennatus 1-5i 251-500i<br />

Larus audounii 51-100i 1001-10000i<br />

Larus melanocephala 11-50i 501-1000i<br />

Lullula arborea 1-5i<br />

Luscinia svecica 1-5i<br />

Melanitta nigra 11-50i<br />

Milvus migrans >10000i<br />

Neophron percnopterus 51-100i<br />

Oceanodroma leucorhoa 11-50i 51-100i<br />

Pandion haliaetus 11-50i<br />

i = individuals; p = pairs.<br />

The International Context<br />

- 21 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 22 -<br />

Population<br />

Migratory<br />

Name Resident Breed Winter Stage<br />

Pernis apivorus >10000i<br />

Ph. aristotelis desmaresti 5p<br />

Ph. carbo sinensis 1-5i<br />

Puffinus mauretanicus 11-50i 1001-10000i<br />

Sterna albifrons 6-10i<br />

Sterna c<strong>as</strong>pia 1-5i<br />

Sterna hirundo 11-50i<br />

Sterna sandvicensis 11-50i 251-500i<br />

Sylvia undata 11-50i 11-501<br />

i = individuals; p = pairs.<br />

Table 3: Bird Species listed in Annex I of the Birds Directive 79/409/EEC<br />

that have been recorded in <strong>Gibraltar</strong>.<br />

Latin name Species<br />

Gavia stellata Red-throated Diver<br />

Gavia immer Great Northern Diver<br />

Calonectris diomedea Cory's Shearwater<br />

Puffinus mauretanicus Balearic Shearwater<br />

Puffinus <strong>as</strong>similis Little Shearwater<br />

Hydrobates pelagicus Storm Petrel<br />

Oceanodroma leucorhoa Leach's Storm-petrel<br />

Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii Shag (Mediterranean sub-species)<br />

Ixobrychus minutus Little Bittern<br />

Nycticorax nycticorax Night Heron<br />

Ardeola ralloides Squacco Heron<br />

Egretta garzetta Little Egret<br />

Ardea purpurea Purple Heron<br />

Ciconia nigra Black Stork<br />

Ciconia ciconia White Stork<br />

Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis<br />

Platalea leucorodia Spoonbill<br />

Phoenicopterus roseus Greater Flamingo<br />

Pernis apivorus Honey Buzzard<br />

Elanus caeruleus Black-shouldered Kite<br />

Milvus migrans Black Kite<br />

Milvus milvus Red Kite<br />

Gypaetus barbatus Bearded Vulture<br />

Neophron percnopterus Egyptian Vulture<br />

Gyps fulvus Griffon Vulture<br />

Aegypius monachus Black Vulture<br />

Circaetus gallicus Short-toed Eagle<br />

Circus aeruginosus Marsh Harrier<br />

Circus cyaneus Hen Harrier<br />

Circus macrourus Pallid Harrier<br />

Circus pygargus Montagu's Harrier<br />

Buteo rufinus Long-legged Buzzard<br />

Aquila pomarina Lesser Spotted Eagle<br />

Aquila clanga Greater Spotted Eagle<br />

Aquila adalberti Spanish Imperial Eagle<br />

Aquila chrysaetos Golden Eagle<br />

Hieraaetus pennatus Booted Eagle<br />

Hieraaetus f<strong>as</strong>ciatus Bonelli's Eagle<br />

Pandion haliaetus Osprey<br />

Falco naumanni Lesser Kestrel<br />

Falco columbarius Merlin<br />

Falco eleonorae Eleonora's Falcon<br />

Falco biarmicus Lanner Falcon<br />

Falco peregrinus Peregrine<br />

Latin name Species<br />

Alectoris barbara Barbary Partridge<br />

Porphyrio porphyrio Purple Gallinule<br />

Grus grus Crane<br />

Otis tarda Great Bustard<br />

Himantopus himantopus Black-winged Stilt<br />

Recurvirostra avosetta Avocet<br />

Burhinus oedicnemus Stone Curlew<br />

Glareola pratincola Collared Pratincole<br />

Pluvialis apricaria Golden Plover<br />

Limosa lapponica Bar-tailed Godwit<br />

Larus melanocephalus Mediterranean Gull<br />

Larus genei Slender-billed Gull<br />

Larus audouinii Audouin's Gull<br />

Gelochelidon nilotica Gull-billed Tern<br />

Sterna c<strong>as</strong>pia C<strong>as</strong>pian Tern<br />

Sterna sandvicensis Sandwich Tern<br />

Sterna dougallii Roseate Tern<br />

Sterna hirundo Common Tern<br />

Sterna paradisaea Arctic Tern<br />

Sterna albifrons Little Tern<br />

Chlidoni<strong>as</strong> hybridus Whiskered Tern<br />

Chlidoni<strong>as</strong> niger Black Tern<br />

Pterocles alchata Pin-tailed Sandgrouse<br />

Bubo bubo Eagle Owl<br />

Asio flammeus Short-eared Owl<br />

Caprimulgus europaeus Nightjar<br />

Apus caffer White-rumped Swift<br />

Alcedo atthis Kingfisher<br />

Coraci<strong>as</strong> garrulus Roller<br />

Melanocorypha calandra Calandra Lark<br />

Calandrella brachydactyla Short-toed Lark<br />

Galerida theklae Thekla Lark<br />

Lullula arborea Woodlark<br />

Anthus campestris Tawny Pipit<br />

Luscinia svecica Bluethroat<br />

Oenanthe leucura Black Wheatear<br />

Sylvia sarda Marmora's Warbler<br />

Sylvia undata Dartford Warbler<br />

Ficedula parva Red-bre<strong>as</strong>ted Flycatcher<br />

Lanius collurio Red-backed Shrike<br />

Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Chough<br />

Bucanetes githagineus Trumpeter Finch<br />

Emberiza hortulana Ortolan Bunting

Table 4: Local status of regularly occurring migratory<br />

birds not listed in Annex I of the Birds Directive.<br />

Population<br />

Migratory<br />

Name Resident Breed Winter Stage<br />

Accipiter nisus 101-250i<br />

Anthus pratensis 51-100i 501-1000i<br />

Anthus trivialis 50-100i<br />

Alca torda 11-50i 1001-10000i<br />

Apus apus 2000p >10000i<br />

Apus melba 25p 251-500i<br />

Apus pallidus 2000p 1001-10000i<br />

Buteo buteo 1-5i 251-500i<br />

Calandrella rufescens 11-50i<br />

Caprimulgus ruficollis 6-10i<br />

Carduelis cannabina 11-50i 1001-10000i<br />

Carduelis carduelis 51-100i 1001-10000i<br />

Carduelis chloris 15p 51-100i 1001-10000i<br />

Carduelis spinus 11-50i 251-500i<br />

Catharacta skua 6-10i 101-250i<br />

Cercotrichi<strong>as</strong> galactotes 1-5i<br />

Certhia brachydactyla 6-10i<br />

Cisticola juncidis 1-5p 11-50i 101-50i<br />

Coturnix coturnix 11-50i<br />

Cuculus canorus 6-10i<br />

Delichon urbica 6-10p 1001-10000i<br />

Erithracus rubercula 1-5p 251-500i 1001-10000i<br />

Falco subbuteo 11-50i<br />

Ficedula hypoleuca 251-500i<br />

Fratercula arctica 1001-10000i<br />

Fringilla coelebs 1-5p 101-250i 1001-10000i<br />

Galerida cristata 1-5i 11-50i<br />

Hippolais pallida 1-5i<br />

Hippolais polyglotta 1001-10000i<br />

Hirundo daurica 51-100i<br />

Hirundo rustica 1001-10000i<br />

Jynx torquilla 1-5i 51-100i<br />

Lanius excubitor 1-5i<br />

Lanius senator 101-250i<br />

Larus fuscus 51-100i 1001-10000i<br />

Larus ridibundus 251-500i 1001-10000i<br />

Locustella naevia 11-50i<br />

Luscinia megarhynchos 1001-10000i<br />

Merops api<strong>as</strong>ter 1001-10000i<br />

Miliaria calandra 1-5i 51-100i<br />

Motacilla alba 101-250i 501-1000i<br />

Motacilla cinerea 11-50i 501-1000i<br />

Motacilla flava 501-1000i<br />

Muscicapa striata 501-1000i<br />

Oenanthe hispanica 251-1000i<br />

Oenanthe oenanthe 251-1000i<br />

Oriolus oriolus 11-50i<br />

Otus scops 6-10i<br />

Phoenicurus ochrurus 501-1000i 1001-10000i<br />

Phoenicurus phoenicurus 1001-10000i<br />

Phylloscopus bonelli 1001-10000i<br />

Phylloscopus collybita 501-1000i 1001-10000i<br />

Phylloscopus trochilus 1001-10000i<br />

Prunella collaris 11-50i<br />

Prunella modularis 11-50i<br />

Ptyonoprogne ruprestis 251-500i 1001-10000i<br />

Puffinus gravis 1-5p<br />

Puffinus griseus 6-10i<br />

Regulus ignicapillus 11-50i<br />

Riparia riparia 51-100i<br />

Saxicola rubetra 51-100i<br />

Saxicola torquata 11-50i 101-250i<br />

Scolopax rusticola 1-5i 1-5i<br />

i = individuals; p = pairs.<br />

The International Context<br />

- 23 -

Biodiversity Action Plan, <strong>Gibraltar</strong>: Planning for Nature<br />

- 24 -<br />

Population<br />

Migratory<br />

Name Resident Breed Winter Stage<br />

Serinus serinus 1-5p 11-50i 251-500i<br />

Stercorarius par<strong>as</strong>iticus 6-10i<br />

Stercorarius pomarinus 1-5i<br />

Sterna bengalensis 1-5i<br />

Sterna maxima 1-5i<br />

Sturnus vulgaris 1001-10000i P<br />

Sylvia atricapilla 251-500p 501-1000i 1001-10000i<br />

Sylvia borin 501-1000i<br />

Sylvia cantillans 101-250i<br />

Sylvia communis 101-250i<br />

Sylvia conspicillata 6-10i<br />

Sylvia hortensis 51-100i<br />

Sylvia melanocephala 251-500p P<br />

Sula b<strong>as</strong>sana 101-250i 1001-10000i<br />

Turdus iliacus 11-50i<br />

Turdus merula 251-500p<br />

Turdus philomelos 51-100i 501-1000i<br />

Turdus torquatus 11-50i<br />

Turdus viscivorus 1-5i 1-5i<br />

Upupa epops 51-100i<br />

i = individuals; p = pairs.<br />

Regularly occurring migratory species not listed in Annex I of the Birds Directive require the Member<br />

States to adopt similar me<strong>as</strong>ures to Annex I species, bearing in mind the need for protection in the geographical<br />

maritime and terrestrial area where this Directive applies, <strong>as</strong> regards their breeding, wintering and<br />

moulting are<strong>as</strong>, and staging posts along their migratory routes.<br />

The Bonn Convention.<br />

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species.<br />

The Bonn Convention, also known <strong>as</strong> the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild<br />

Animals (or CMS) aims to conserve terrestrial, marine and avian migratory species throughout their range.<br />

It w<strong>as</strong> concluded on the 1 November 1983 under the auspices of the United Nations Environment<br />

Programme, and is concerned with the conservation of wildlife and habitats on a global scale.<br />

The objective of this Convention is the conservation of migratory species of wildlife worldwide. The parties<br />

to the Convention are required to pay special attention to species whose conservation status is<br />

unfavourable, and h<strong>as</strong> to endeavour to apply the following main provisions.<br />

The Bonn Convention or The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of<br />

Wild Animals (CMS). Main provisions.<br />

• to promote, cooperate in or support research relating to migratory species.<br />

• to provide immediate protection to migratory species included in Appendix I<br />

• to conclude agreements covering the conservation and management of migratory<br />

species listed in Appendix II<br />

• to conserve or restore the habitats of endangered species.<br />

• to prevent, remove, compensate for or minimise the adverse effects of activities or obstacles<br />

that impede the migration of the species.<br />

• to the extent fe<strong>as</strong>ible and appropriate, to prevent, reduce or control factors that are<br />

endangering or are likely to further endanger the species.

Appendix I of the Convention includes a list of Migratory species which are endangered in Europe.<br />

Appendix 2 lists migratory species which have an unfavourable conservation status and which require international<br />

agreements for their conservation and management, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> those which have a conservation<br />