Final SACOG Phase 1 Goods Movement Report

Final SACOG Phase 1 Goods Movement Report

Final SACOG Phase 1 Goods Movement Report

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

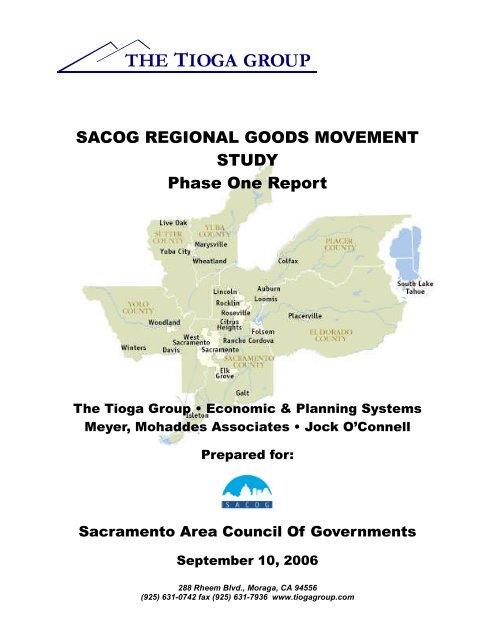

THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

<strong>SACOG</strong> REGIONAL GOODS MOVEMENT<br />

STUDY<br />

<strong>Phase</strong> One <strong>Report</strong><br />

The Tioga Group•Economic & Planning Systems<br />

Meyer, Mohaddes Associates• Jock O’Connel<br />

Prepared for:<br />

Sacramento Area Council Of Governments<br />

September 10, 2006<br />

288 Rheem Blvd., Moraga, CA 94556<br />

(925) 631-0742 fax (925) 631-7936 www.tiogagroup.com

THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Jason Crow<br />

Senior Planner<br />

Sacramento Area Council of Governments<br />

1415 L Street, Suite 300<br />

Sacramento, CA 95814<br />

Dear Mr. Crow:<br />

September 10, 2006<br />

We appreciate the opportunity to submit this <strong>Final</strong> <strong>Report</strong> for <strong>Phase</strong> One of the <strong>SACOG</strong> Regional <strong>Goods</strong><br />

<strong>Movement</strong> Study. For this project, the Tioga Group was joined by Economic & Planning Systems,<br />

Meyer, Mohaddes Associates, and Jock O’Connel.<br />

The report follows the original Scope of Work closely, reorganized somewhat to make the material flow<br />

more smoothly and to reflect emerging priorities. As this is the first study of a multi-phase program, we<br />

have incorporated a fair amount of background information on the goods movement industry and how it<br />

operates in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region.<br />

We are grateful <strong>SACOG</strong>’s asistance in gathering and transmiting comments from Caltrans, the Port of<br />

Sacramento, the Sacramento County Airport System, Investnet, and other parties as well as the <strong>SACOG</strong><br />

staff. The study team has reviewed these comments and made numerous changes in the draft report.<br />

We are committed to meeting and exceeding <strong>SACOG</strong>’s expectations for this project, and look forward to<br />

working on <strong>Phase</strong> two.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Daniel Smith, Principal and Project Manager<br />

288 Rheem Blvd., Moraga, CA 94556<br />

(925) 631-0742 fax (925) 631-7936 www.tiogagroup.com

Contents<br />

I. INTRODUCTION 7<br />

II. HIGHWAYS AND TRUCKING 13<br />

III. RAILROADS 39<br />

IV. AIRPORTS 53<br />

V. PORT OF SACRAMENTO 59<br />

VI. FREIGHT AND DISTRIBUTION FACILITIES 69<br />

VII. GOODS MOVEMENT DATA AND GAP ANALYSIS 85<br />

VIII. GOODS MOVEMENT DECISION FACTORS 117<br />

IX. LOGISTICS TRENDS 127<br />

X. REGIONAL GOODS MOVEMENT ISSUES & NEEDS 131<br />

XI. GOODS MOVEMENT ECONOMIC IMPACTS 181<br />

XII. LAND USE AND REAL ESTATE ISSUES 197<br />

XIII. GOODS MOVEMENT LAND USE IMPLICATIONS 203<br />

XIV. NEXT STEPS 215<br />

APPENDIX A: GOODS MOVEMENT STAKEHOLDERS 217<br />

APPENDIX B: JURISDICTIONS SURVEY 233<br />

APPENDIX C: CASE STUDIES 239<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page i

Exhibits<br />

Exhibit 1: Freight Transportation Participants 8<br />

Exhibit 2: <strong>SACOG</strong> Regional <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> Network 9<br />

Exhibit 3: <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong>s To, From, and Within the <strong>SACOG</strong> Region 10<br />

Exhibit 4: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region as Crossroads 11<br />

Exhibit 5: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region as Hub 12<br />

Exhibit 6: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region Highways 13<br />

Exhibit 7: Truck Percentages on Sacramento (City) Freeways 14<br />

Exhibit 8: Trucking Industry Structure. 16<br />

Exhibit 9: Dedicated and Contract Carriage 17<br />

Exhibit 10: For-Hire Carrier Revenue 17<br />

Exhibit 11: Four Prevalent Vehicles and Combinations 18<br />

Exhibit 12: Straight Truck 18<br />

Exhibit 13: Tractor 19<br />

Exhibit 14: Trailer 19<br />

Exhibit 15: Semi-trailer 20<br />

Exhibit 16: Converter Gear or “Doly” 20<br />

Exhibit 17: Tractor/Semi-trailer 21<br />

Exhibit 18: Western Doubles 21<br />

Exhibit 19: Truck and Trailer 22<br />

Exhibit 20: California Truck Fleet Composition 22<br />

Exhibit 21: Class 1-8 Gross Vehicle Weight Classifications 23<br />

Exhibit 22: California Truck Classifications 23<br />

Exhibit 23: Medium-duty Truck Body Type Examples 24<br />

Exhibit 24: Heavy-duty (Class 6-7) Truck Body Type Examples 25<br />

Exhibit 25: Tractor and 28-foot “Pup” Trailer 25<br />

Exhibit 26: Class 8 Tractors & Semi-Trailers 26<br />

Exhibit 27: Truck Types and Applications 27<br />

Exhibit 28: Heavy Duty Truck Uses - 1997 27<br />

Exhibit 29: Private and For-Hire Length of Haul 28<br />

Exhibit 30: Truck Payloads (Fresno COG Model) 29<br />

Exhibit 31: Generalized Truck Trip Patterns 30<br />

Exhibit 32: Trucking Industry Composite Expense Shares 32<br />

Exhibit 33: <strong>SACOG</strong> Truck “Terminal” Locations 34<br />

Exhibit 34: Yuba City-Marysville Regional Cluster 34<br />

Exhibit 35: West Sacramento Trucking Cluster 35<br />

Exhibit 36: West Sacramento Aerial Photo 35<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page ii

Exhibit 37: Woodland Trucking Cluster 36<br />

Exhibit 38: MISTER Terminal Data by City 36<br />

Exhibit 39: MISTER Terminal Data by County 37<br />

Exhibit 40: Sacramento Area Rail Lines 39<br />

Exhibit 41: Sacramento Area Rail Connections 40<br />

Exhibit 42: Mechanized Intermodal Lift Equipment 41<br />

Exhibit 43: Typical Intermodal Terminal–BNSF Stockton 41<br />

Exhibit 44: Northern California/ Nevada Rail Intermodal Terminals 42<br />

Exhibit 45: Rail Auto Loading Facility (Richmond) 42<br />

Exhibit 46: Northern California Rail Auto Terminals 43<br />

Exhibit 47: California Rail Network 44<br />

Exhibit 48: Elvas Junction 45<br />

Exhibit 49: Double-stack Train on UP Canyon Subdivision 47<br />

Exhibit 50: Haggin Junction 48<br />

Exhibit 51: BNSF Train Operating Over Canyon Subdivision via Trackage Rights 49<br />

Exhibit 52: 2005 McClellan Transloading Carload Volume 50<br />

Exhibit 53: Sacramento Air Cargo Activity (Metric Tons) 55<br />

Exhibit 54: Port of Sacramento Facilities 59<br />

Exhibit 55: Port of Sacramento Tonnage 1990 - 2004 60<br />

Exhibit 56: Port of Sacramento Cargoes 60<br />

Exhibit 57: Port of Sacramento Area 61<br />

Exhibit 58: Port of Sacramento Hinterland 62<br />

Exhibit 59: Port of Sacramento General Cargo Wharf 6 66<br />

Exhibit 60: Central Freight Lines Terminal 70<br />

Exhibit 61: Con-Way Express Terminal 70<br />

Exhibit 62: FedEx Freight West Terminal 71<br />

Exhibit 63: Oak Harbor Freight lines Terminal 71<br />

Exhibit 64: Old Dominion Terminal 72<br />

Exhibit 65: Overnite & Other Terminals 72<br />

Exhibit 66: Roadway Terminal 73<br />

Exhibit 67: Watkins Freight Terminal 73<br />

Exhibit 68: Yellow Freight Terminal 74<br />

Exhibit 69: UPS Terminal 74<br />

Exhibit 70: Yellow Freight LTL Terminal Outside Tracy 75<br />

Exhibit 71: LTL and Parcel Terminal Locations 76<br />

Exhibit 72: 49er Travel Plaza 77<br />

Exhibit 73: Truck Scales 78<br />

Exhibit 74: Commercial Card Lock Fueling Sites 79<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page iii

Exhibit 75: Truck Stop Fueling 80<br />

Exhibit 76: JR Davis Yard at Roseville 81<br />

Exhibit 77: Simple Supply Chain 82<br />

Exhibit 78: Woodland Distribution Center 82<br />

Exhibit 79: Sierra Northern Transloading at McClellan 84<br />

Exhibit 80: Sacramento Area Freight O/D Summary (2002) 87<br />

Exhibit 81: Major Commodity Flow Shares 88<br />

Exhibit 82: Destinations of Outbound Commodity Flows 88<br />

Exhibit 83: Origins of Inbound Commodity Flows 89<br />

Exhibit 84: Outbound Commodity Shares - 2002 90<br />

Exhibit 85: Inbound Commodity Shares–2002 91<br />

Exhibit 86: Local Commodity Shares - 2002 92<br />

Exhibit 87: Estimated Through vs. Local Freight Flows -2002 93<br />

Exhibit 88: Estimated Through Tonnage by Commodity - 2002 94<br />

Exhibit 89: Average Daily 3-5 Axle Trucks on Major <strong>SACOG</strong> Routes in 2004 95<br />

Exhibit 90: Average Daily 2004 3-5 Axle Trucks on Highways 5, 50, 70 96<br />

Exhibit 91: Average Daily 2004 3-5 Axle Trucks on Highways 80, 99, 113, 505 97<br />

Exhibit 92: Truck Count “Taper” on US Highway 50 (West to East) 98<br />

Exhibit 93: Truck Count “Taper” on US Highway 990 (South to North) 98<br />

Exhibit 94: California State Truck Flows - 1998 99<br />

Exhibit 95: Total Sacramento BEA Rail Tonnage -2003 100<br />

Exhibit 96: Outbound Rail <strong>Movement</strong>s–2003 to 2020 100<br />

Exhibit 97: Inbound Rail <strong>Movement</strong>s–2003 to 2020 101<br />

Exhibit 98: Local Rail <strong>Movement</strong>s–2003 to 2020 101<br />

Exhibit 99: Projected Bay Area Train Counts 102<br />

Exhibit 100: 1999-2004 USACE SF Bay Tonnage Data 102<br />

Exhibit 101: USACE Port Data (000 short tons) 103<br />

Exhibit 102: Air Cargo at SMF and MHR–Metric Tons 104<br />

Exhibit 103: Carrier Shares of Sacramento Area Air Cargo 105<br />

Exhibit 104: SMF Actual vs. Master Plan Forecasts, Metric Tons 109<br />

Exhibit 105: MHR Actual vs. Master Plan Forecasts, Metric Tons 110<br />

Exhibit 106: International Air Cargo at SFO, Metric Tons 112<br />

Exhibit 107: Domestic Air Cargo at SFO, Metric Tons 113<br />

Exhibit 108: Supply Chain Schematic 118<br />

Exhibit 109: Cola Supply Chain Example 119<br />

Exhibit 110: Conceptual Modal Tradeoffs 121<br />

Exhibit 111: Mode Selection 122<br />

Exhibit 112: Unit Cost vs. Length of Haul 123<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page iv

Exhibit 113: 100-ton Capacity Rail Car 125<br />

Exhibit 114: Logistics Costs as a Percent of GDP 128<br />

Exhibit 115: Supply Chain and Inventory Relationships 129<br />

Exhibit 116: Jurisdiction Survey Issue Ranking 132<br />

Exhibit 117: <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> Study Survey Results 133<br />

Exhibit 118: California State Truck Route Types 142<br />

Exhibit 119: Sacramento County Truck Routes 144<br />

Exhibit 120: Yolo County Truck Routes 145<br />

Exhibit 121: Yuba County Truck Routes 146<br />

Exhibit 122: Sutter County Truck Routes 147<br />

Exhibit 123: Placer County Truck Routes 148<br />

Exhibit 124: El Dorado County Truck Routes 149<br />

Exhibit 125: City of Roseville Truck Routes 150<br />

Exhibit 126: City of Woodland Truck Routes 151<br />

Exhibit 127: Sacramento Metro Area Truck Routes 153<br />

Exhibit 128: Sacramento Area STAA Map 154<br />

Exhibit 129: Sacramento City Truck Routes 155<br />

Exhibit 130: Parking Location Issues - Conceptual 157<br />

Exhibit 131: Truck Parking in Residential Areas 158<br />

Exhibit 132: On-Street Truck Parking 159<br />

Exhibit 133: Trailer Drop Lot 160<br />

Exhibit 134: UC Riverside HHDDT Road Test Results 161<br />

Exhibit 135: American River Crossings 162<br />

Exhibit 136: El Dorado County Truck-Involved Collisions 168<br />

Exhibit 137: Placer County Truck-Involved Collisions 169<br />

Exhibit 138: Sacramento County Truck-Involved Collisions 170<br />

Exhibit 139: Sutter County Truck-Involved Collisions 171<br />

Exhibit 140: Yolo County Truck-Involved Collisions 172<br />

Exhibit 141: Yuba County Truck-Involved Collisions 173<br />

Exhibit 142: <strong>Report</strong>ed Truck Traffic Generators 174<br />

Exhibit 143: Employment Growth Projections by Area 182<br />

Exhibit 144: <strong>SACOG</strong> Total Employment by Sector 183<br />

Exhibit 145: Total Employment by <strong>SACOG</strong> County and Sector, 2004 185<br />

Exhibit 146: Projected Employment by Industry (2004-2030) 186<br />

Exhibit 147: Projected Employment by Industry (2004-2030) 187<br />

Exhibit 148: Industry Employment as Percentage of Total Employment 187<br />

Exhibit 149: Logistics Sector Employment by County, 2004 189<br />

Exhibit 150: Logistics Sector Employment, 2004 190<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page v

Exhibit 151: County Shares of Logistics Employment 191<br />

Exhibit 152: Average Annual Payroll in Logistics Sectors, 2004 191<br />

Exhibit 153: Regional Employment, Weekly Salary, and Annual Salary, 2004 192<br />

Exhibit 154: Logistics Sector Average Annual Wages, 2004 193<br />

Exhibit 155: Employment in Selected Sectors, Sacramento Region: 1990–2003 194<br />

Exhibit 156: Clusters of Opportunity by Employment Concentration 195<br />

Exhibit 157: SCAOG Region Leading Agricultural Commodities 195<br />

Exhibit 158: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region Manufacturing Employment, Payroll, Value Added 196<br />

Exhibit 159: Net Rentable Industrial Square Feet (in 1,000's 197<br />

Exhibit 160: Industrial Vacancy Rates by Submarket 198<br />

Exhibit 161: Industrial Net Absorption (in 1,000 square feet) 198<br />

Exhibit 162: Sacramento Region Trends 199<br />

Exhibit 163: IKEA Distribution Center Example 200<br />

Exhibit 164: West Sacramento Distribution Centers 200<br />

Exhibit 165: Estimated Space Demand 2004-2030: Warehouse/Distribution 201<br />

Exhibit 166: Industrial Lease Rates by Submarket 201<br />

Exhibit 167: Bay Area Warehouse Market Summary, 1Q06 202<br />

Exhibit 168: Narrower Streets 206<br />

Exhibit 169: Riverside Gateway Opportunity Site 206<br />

Exhibit 170: Opportunity Site Development Scenarios 207<br />

Exhibit 171: Alley Access to Older Buildings 208<br />

Exhibit 172: Mixed Use Developments 208<br />

Exhibit 173: Supporting Land Uses for Transit-Oriented Development 209<br />

Exhibit 174: I80 Trucking Cluster 213<br />

Exhibit 175: US50 Trucking Cluster 214<br />

Exhibit 176: Partial List of <strong>SACOG</strong> Region Trucking Firms 217<br />

Exhibit 177: <strong>SACOG</strong> Area LTL Truck Terminals 226<br />

Exhibit 178: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region Truck Stops (Partial Listing) 226<br />

Exhibit 179: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region “Card Lock” Truck Fueling Stations 226<br />

Exhibit 180: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region Truck Repair and Services 227<br />

Exhibit 181: Firms Described as Warehouses or Distribution Centers 228<br />

Exhibit 182: Air Cargo & Air Freight Forwarders 229<br />

Exhibit 183: Moving and Storage Companies 230<br />

Exhibit 184: Private Sector <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> Advisory Group Attendees 231<br />

Exhibit 185: Public Sector <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> Advisory Group Attendees 232<br />

Exhibit 186: Daily Deliveries at Whole Foods Market 251<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page vi

I. Introduction<br />

Background<br />

The Sacramento Area Council of Governments (<strong>SACOG</strong>) and other agencies are confronting serious<br />

long-term freight mobility issues in California. Straightforward capacity increases that<br />

worked in the past–more highways, larger airports–are not enough for the future. Moreover,<br />

capacity increases that compromise the environment, tax the budget, and impinge on sensitive<br />

communities may no longer be possible or desirable.<br />

As both the regional Metropolitan Planning Organization and the Regional Transportation Planning<br />

Agency, <strong>SACOG</strong> has multiple freight transportation responsibilities. Regional policy makers<br />

need better information on goods movement:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

to understand the role freight transportation and distribution plays in the broader<br />

economic development of the <strong>SACOG</strong> region and the surrounding portions of<br />

northern California;<br />

to recognize planning and policy decisions with implications for freight transportation,<br />

and recognize freight transportation trends with implications for public policy<br />

and planning; and<br />

to make the well-informed trade-offs that are an inescapable part of planning in a<br />

complex urban environment.<br />

The recent development of the State <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> Action Plan and the enormous funding<br />

commitment that it contemplates underscores the need for reliable, comprehensive goods movement<br />

information and insights.<br />

<strong>SACOG</strong> intends to develop a regional freight action plan that will be completed in three phases.<br />

<strong>Phase</strong> One of this effort, the subject of this report, begins this process by assessing current conditions<br />

in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region. The freight action plan is to be linked with the <strong>SACOG</strong>/Valley Vision<br />

Blueprint transportation and land use study, which will in turn serve as a key input to the<br />

2030 Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP) and Metropolitan Transportation Improvement<br />

Plan (MTIP). This <strong>Phase</strong> One study wil thus serve as a building block of <strong>SACOG</strong>’s freight<br />

transportation policy and programming for years to come.<br />

This report addresses goods movement activities in the six-county <strong>SACOG</strong> region including<br />

highway, railroad, marine, and air cargo transportation. Warehouse and distribution centers,<br />

transloading facilities, and truck stop facilities are also discussed.<br />

A key objective of <strong>Phase</strong> One was to develop a well-organized body of data and information on<br />

goods movement in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region. This report, with its appendices, should provide planners<br />

and oficials with the “big picture” on freight transportation and distribution functions in the<br />

region and a firm basis for choosing where and when more detailed subsequent inquiry may be<br />

required in <strong>Phase</strong> Two. Economic and other factors influencing current goods movement deci-<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 7

sions in the region were incorporated in a trend analysis covering the next 10-20 years. <strong>Final</strong>ly,<br />

this report preliminarily identifies the land use implications of goods movement in the region.<br />

Regional Freight <strong>Movement</strong>s<br />

There can be numerous parties involved in seemingly simple freight movement, as shown in<br />

Exhibit 1 and listed below.<br />

Exhibit 1: Freight Transportation Participants<br />

SHIPPER -<br />

PREPARES AND<br />

ORGINATES THE<br />

MOVEMENT AT<br />

ORIGIN<br />

CARRIER–<br />

MOVES THE FREIGHT<br />

CONSIGNEE<br />

(RECEIVER) -<br />

RECEIVES THE<br />

FREIGHT AT<br />

DESTINATION<br />

INTERMEDIARY<br />

(OR THIRD PARTY) –<br />

ARRANGES TRANSPORTATION<br />

FOR OTHERS<br />

FLEET OPERATOR –<br />

OPERATES (AND MAY<br />

OWN) THE VEHICLES<br />

BENFICIAL OWNER –<br />

ACTUALLY OWNS THE GOODS<br />

(AND MAY BE THE SHIPPER OR<br />

THE CONSIGNEE)<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Shippers (typically manufacturers or other producers and distributors) prepare<br />

freight for transport and originate the movement.<br />

Consignees or receivers (typically customers of the shippers) receive the freight at<br />

the destination.<br />

The shipper or receiver may or may not actually own the goods. The party who<br />

owns the goods being shipped is the beneficial owner.<br />

Carriers (transportation service providers) are firms that move freight by one or<br />

more mode. The direct customer of a freight carrier may be a shipper, a consignee,<br />

a beneficial owner, an intermediary, or even another carrier.<br />

Fleet operators operate (and may also own and maintain) the vehicles used to<br />

move freight. Fleet operators include both for-hire carriers (that transport freight<br />

for customers as the primary business) and private operators (that transport their<br />

own freight, usually for final delivery to customers).<br />

Intermediaries or third parties (including freight forwarders, shipper’s agents, third<br />

party logistics managers, and brokers) arrange transportation on behalf of shippers<br />

or receivers.<br />

There are three basic goods movement patterns corresponding to the triple role of the <strong>SACOG</strong><br />

Region.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 8

Regional Network<br />

Exhibit 2 shows the complete <strong>SACOG</strong> region goods movement network, a complex of highways,<br />

rail lines, streets, waterways, and airports. Besides the overall complexity, this exhibit clearly<br />

illustrates the convergence of the network in Sacramento.<br />

Exhibit 2: <strong>SACOG</strong> Regional <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> Network<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 9

Regional Production and Consumption: Local <strong>Movement</strong>s<br />

The region produces and consumes goods as a function of its population, resources, and economic<br />

activity. Production and consumption results in goods movements to, from, and within the<br />

region (Exhibit 3).<br />

Exhibit 3: <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong>s To, From, and Within the <strong>SACOG</strong> Region<br />

REGIONAL PRODUCTION &<br />

CONSUMPTION:<br />

MOVEMENTS TO, FROM,<br />

AND WITHIN<br />

These movements are predominantly truck trips but also include air cargo (with pickup and delivery<br />

by truck), waterborne shipments (with inland transport by truck or rail), and rail carload<br />

service (direct or transloaded).<br />

Crossroads: Through <strong>Movement</strong>s<br />

The highways and rail lines converging and radiating in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region make it a crossroads<br />

for goods movements between other regions (Exhibit 3).<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 10

Exhibit 4: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region as Crossroads<br />

REGIONAL CROSSROADS:<br />

THROUGH MOVEMENTS<br />

The through movements are again mostly truck trips but also include substantial volumes of carload<br />

and intermodal rail trafic. There is no through maritime trafic and “through” air trafic<br />

does not affect the region.<br />

Regional Hub<br />

The confluence of the rivers and valleys and its central location have made the Sacramento area a<br />

regional hub for more than a century, since the establishment of Suter’s Fort. Its role as a hub<br />

results in consolidation, distribution, and transloading movements ( Exhibit 5).<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 11

Exhibit 5: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region as Hub<br />

REGIONAL HUB:<br />

CONSOLIDATION, DISTRIBUTION, &<br />

TRANSLOADING MOVEMENTS<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 12

II. Highways and Trucking<br />

Highways<br />

The highway network in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region has multiple layers.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

The Interstate highway system is a federally-funded backbone for regional and interregional<br />

movement. As shown in Exhibit 6, the <strong>SACOG</strong> region is served by Interstate<br />

5 running north-south, Interstate 80 running east-west, Business 80 running<br />

through Sacramento, and Interstate 505 connecting them through Winters.<br />

The California State highway system (US50 and US99, Exhibit 6) predate the Interstate<br />

system. Now, they provide access to portions of the region off the Interstates.<br />

US99, in particular, serves the population centers of the Sacramento and San Joaquin<br />

Valleys that Interstate 5 bypasses.<br />

Surface streets and roads are a mixed city and county system. For the purposes of<br />

goods movement, they provide access to most actual origins and destinations.<br />

Exhibit 6: <strong>SACOG</strong> Region Highways<br />

Interstate 5, Interstate 80, SR99, SR70, and US50 all converge in Sacramento. The percentage of<br />

truck traffic on freeways in the City of Sacramento is summarized in Exhibit 7. I5 through downtown<br />

Sacramento has the highest truck percentage (9.6 percent), while US50 has the lowest percentage<br />

of trucks (3.4 percent).<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 13

Exhibit 7: Truck Percentages on Sacramento (City) Freeways<br />

Interstate/Highway<br />

Vehicle<br />

Percentage of<br />

1 Truck AADT1<br />

AADT Trucks<br />

I5 at I Street 170,000 16,320 9.6%<br />

I80 east of Jct. I5 143,000 8,190 5.7%<br />

US50 east of Jct. SR 99 221,000 7,450 3.4%<br />

SR99 south of Jct. US50 216,000 9,740 4.5%<br />

Bus. 80 north of Jct. US 50 163,000 8,150 5.0%<br />

1 AADT = Average annual daily traffic volumes. Volumes reflect freeway segments closest to downtown Sacramento<br />

for comparison purposes. Source: Caltrans, 2004; City of Sacramento<br />

The I80 bypass keeps east-west I80 traffic out of downtown Sacramento, but does not help US50<br />

traffic. The rapid residential and commercial development east of Sacramento to Placerville and<br />

the comparable growth in the Carson Valley south of Reno, however, has greatly increased the<br />

demand for trucking on US50. Interstate 505 provides a bypass between I5 and I80 (and SR113<br />

between Woodland and Davis provides an alternate bypass). North-south traffic on I5 itself,<br />

however, must still pass through the western edge of downtown Sacramento. SR99 and SR70<br />

merge north of Sacramento and merge with I5 east of the Sacramento airport. To continue on<br />

SR99, trucks must jog 2 miles east through congested urban traffic in Sacramento.<br />

Usage of Freeways and Highways<br />

Truck drivers and dispatchers view the highway network from a different perspective than auto<br />

drivers. The general comments below reflect common industry experience.<br />

Interstate 80<br />

Interstate 80 is the only practical route to/from the Bay Area and it is used for multiple purposes.<br />

One is for distribution of finished goods into the population and manufacturing located in the<br />

Bay Area. Another is for trips to the Port of Oakland for export of agricultural products from the<br />

<strong>SACOG</strong> region. Imports to the <strong>SACOG</strong> region and northern Nevada coming into the Ports of<br />

Benicia (autos) and Oakland (containers) also use this route. This route and I80 east are also<br />

used by trucks between California and points east of the Sierra Nevada for all purposes. <strong>Final</strong>ly,<br />

it is the only route for the long haul trucks using I80 to/from points east of Sacramento to get<br />

to/from the Bay Area. This is the primary route for goods consumed in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region coming<br />

from the east, and the route for distribution of finished goods originating or rehandled in the<br />

<strong>SACOG</strong> region and distributed to the east (e.g. Reno/Sparks). This is also the route for trucks<br />

that transit the <strong>SACOG</strong> region to/from points west (Bay Area), south (Central Valley), and to an<br />

extent north (Sacramento Valley).<br />

Interstate 80 is subject to heavy, recurring congestion all the way to Oakland and lacks rest areas<br />

and truck parking closer to the Bay Area. To the east this route may have insufficient capacity<br />

for growing trucking operations as lane reductions occur too soon. Safety can be compromised<br />

when truckers have to move one lane to the left as lanes are dropped. Drivers find it difficult to<br />

cross oncoming traffic entering at Business I80 to get to the right hand lanes and sightlines approaching<br />

the junction where Business I80 merges from the right are also a source of problems.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 14

Interstate 5<br />

Truckers use I5 to access local customers, West Sacramento industry, and trucking domiciles. I5<br />

is the primary route to from Northern California and Pacific Northwest. There are relatively few<br />

customers south on I5 so truckers use it primarily as a through route to/from San Joaquin County<br />

and points south. Truckers have difficulty with the frequency of interchanges and entering lanes<br />

on I5. I5 is perceived as lacking capacity, with too many entrances and exits north of Meadowview.<br />

US50<br />

Truckers use US50 to access local customers all the way to South Tahoe. Truck drivers avoid it<br />

on weekends and holidays because of the vacation traffic. US50 is not a high-capacity highway,<br />

especially east of Placerville.<br />

US99<br />

Truckers use US99 to access local customers and trucking terminals that are mostly bypassed by<br />

I5, so US99 is the primary route for trips to Central Valley points as far as Bakersfield. This is<br />

the “trucker’s aley”.US99 was built to older designs, with awkward entrances and exits in some<br />

areas. There are few rest stops. Where US99 still has intersections with surface streets truckers<br />

would prefer limited access.<br />

SR65/70<br />

State highways 65 and 70 are used to access local customers. Truckers also use SR65 connecting<br />

to SR20 as a “cut-of” between I80 and I5. These routes suffer from lack of capacity, rough<br />

pavement, and heavy side traffic.<br />

Howe-Power Inn/ Watt Ave/Grant Line-Sunrise/Hazel-Sierra College<br />

These surface routes are used for local service and to bypass US99/Business I80 during periods<br />

of congestion. The “funnel efect” geting acros the American River creates its own congestion.<br />

SR12<br />

SR12 is used for local service and as a cut-off between Napa, Sonoma, Solano, and Central Valley<br />

areas. SR12 is becoming a major trucking route to bypass Sacramento. This route requires<br />

special mention because so little of it is within the <strong>SACOG</strong> territory.<br />

Trucking Industry Structure<br />

In the context of freight movement, the “trucking industry” is usualy taken to include commercial,<br />

private, and owner-operators of trucks carrying goods.The concept of “carying goods” becomes<br />

complex when the “goods” can include new equipment being delivered to the buyer, the<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 15

same equipment being moved the next day to a job site, or a combination of the same equipment,<br />

supplies, and personnel.<br />

There are many diferent definitions of the “trucking industry” and many diferent estimates of<br />

its size. In March 2000 there were reportedly more than 500,000 motor carriers in the U.S. As<br />

of 1998, about 9.7 million people were employed in logistics, of which about 30 percent were<br />

truck drivers. The chart in Exhibit 8 provides an overall perspective on the trucking industry for<br />

fleets larger than 10 vehicles.<br />

Exhibit 8: Trucking Industry Structure.<br />

Total<br />

84,872 Fleets<br />

12,383,061 Vehicles<br />

For-Hire<br />

28,448 Fleets<br />

6,357,021 Vehicles<br />

Private<br />

37,975 Fleets<br />

3,092, 720 Vehicles<br />

Private-Type<br />

18,449 Fleets<br />

2,933,320 Vehicles<br />

Common Carriers<br />

25,534 Fleets<br />

4,890,771 Vehicles<br />

Lease/Rental<br />

2,914 Fleets<br />

1,466,250 Vehicles<br />

Retail & Wholesale<br />

Delivery<br />

7,605 Fleets<br />

628,024 Vehicles<br />

Government<br />

9,544 Fleets<br />

1,982,801 Vehicles<br />

Schools<br />

3,744 Fleets<br />

298,592 Vehicles<br />

Public Utility<br />

3,842 Fleets<br />

486,237 Vehicles<br />

Buses<br />

1,319 Fleets<br />

165,690 Vehicles<br />

Interstate<br />

Local<br />

Intrastate<br />

Full-Service Lease<br />

Finance Lease<br />

Rental<br />

Food<br />

Distribution<br />

7,159 Fleets<br />

761,766 Vehicles<br />

Construction<br />

& Mining<br />

11,386 Fleets<br />

616,061 Vehicles<br />

Federal<br />

Municipal<br />

State<br />

County<br />

School District<br />

Private Contractors<br />

Telephone<br />

Electric<br />

Gas<br />

Interstate<br />

Local<br />

Intrastate<br />

Manufacturing<br />

& Distribution<br />

5,870 Fleets<br />

430,165 Vehicles<br />

Petroleum<br />

3,100 Fleets<br />

183,572 Vehicles<br />

Sanitation<br />

& Refuse<br />

1,307 Fleets<br />

94,564 Vehicles<br />

Other Services<br />

1,548 Fleets<br />

378,568 Vehicles<br />

For-Hire vs. Private Fleets. Commercial carriers are companies where trucking is the primary<br />

business. At private carriers, trucking is not the primary business, but is conducted in support of<br />

the primary business (e.g., sale of goods). Owner-operators can be commercial carriers, but most<br />

often provide capacity to either commercial or private carriers under contract.<br />

These categories overlap, as do the purposes of their truck trips. For example:<br />

<br />

<br />

Commercial contract carriers may operate as a private fleet while in the service of a<br />

major customer.<br />

Owner-operators commonly drive for either a commercial trucking firms or for a<br />

private fleet, supplying a tractor and occasionally a trailer.<br />

In common public parlance, “trucker” refers to for-hire carriers. There are two types:<br />

<br />

Common carriers. Common carriers are those that offer services to anyone with<br />

freight to move. In practice, common carriers typically specialize by commodity or<br />

region. Most trucking firms familiar to the general public are common carriers.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 16

Dedicated carriers. For-hire motor carriers include companies that operate on a dedicated<br />

basis under contract to a shipper or receiver of the goods (also sometimes called<br />

contract carriers). Some carriers are exclusively common or dedicated carriers while others<br />

offer both common and dedicated service.<br />

It is often hard to distinguish between dedicated and private fleets. In Exhibit 9, the Pepsi truck<br />

has a tractor with the Pepsi logo. Pepsi-Cola contracted out with a truckload carrier to provide<br />

dedicated service, and the dedicated tractors used for Pepsi shipments carry the Pepsi logo. In<br />

the other picture, DuPont owns both the tank truck and the tractor, while the driver is hired on a<br />

contract basis. DuPont is a private fleet operator while Pepsi-Cola is not.<br />

Exhibit 9: Dedicated and Contract Carriage<br />

The for-hire carrier sector can be split out by revenue, as shown in Exhibit 10. Typical closedvan<br />

truckload business accounts for about 29% of the revenue, but all kinds of truckload business<br />

together accounts for almost 60%. Less-than-truckload (LTL) carriage accounts for much more<br />

of the revenue than of the vehicles or miles, because the revenue per ton is much higher (as is the<br />

cost).<br />

Exhibit 10: For-Hire Carrier Revenue<br />

Household <strong>Goods</strong><br />

5%<br />

Tank<br />

6%<br />

Bulk<br />

2%<br />

Refrigerated<br />

7% Other<br />

9%<br />

Less Than<br />

Truckload<br />

42%<br />

Truckload<br />

29%<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 17

Truck Types and Uses<br />

“Trucks” and combination vehicles vary in their configuration. Four types of commercial vehicles<br />

and combinations are common in California (Exhibit 11).<br />

Exhibit 11: Four Prevalent Vehicles and Combinations<br />

Straight truck<br />

3 axle tractor with tandem axle<br />

semi-trailer (“semi”)<br />

2 axle tractor with two<br />

single axle semitrailers<br />

(“doubles”)<br />

Three axle straight truck<br />

coupled to a two axle full<br />

(pull) trailer<br />

These and all truck combinations all are made up of one or more basic units defined below.<br />

A truck (Exhibit 12) is a single powered unit with both the steering axle and the drive axle(s) on<br />

a single chassis, and a provision for mounting a body on the top of the chassis. Trucks are often<br />

caled “straight trucks” to distinguish them from tractor-trailers. The majority of trucks are<br />

straight trucks, especially the smaller types used in local goods movement and service delivery.<br />

Exhibit 12: Straight Truck<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 18

A tractor (Exhibit 13) is a single powered unit with a steering axle and drive axle(s), with a device<br />

caled a “fifth wheel” that alows the tractor to be coupled to a semi-trailer.<br />

Exhibit 13: Tractor<br />

A trailer (Exhibit 14) is a non-powered, stand-alone cargo-carrying unit that can be pulled by a<br />

truck or another powered unit. True trailers are self-supporting.<br />

Exhibit 14: Trailer<br />

A semi-trailer (Exhibit 15) is an unpowered unit with a kingpin mounted in an upper coupler at<br />

the nose suitable for connecting to the fifth wheel on a tractor. A semi-trailer has axles only at<br />

the rear and must be connected and pulled via the fifth wheel.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 19

Exhibit 15: Semi-trailer<br />

A “converter gear” or “doly” (Exhibit 16) can be used under the front of a semi-trailer, effectively<br />

converting the semi-trailer into a true trailer. Thus converted, a semi-trailer can be hitched<br />

to another semi-trailer to create “doubles” or “triples”, or puled behind a straight truck.<br />

Exhibit 16: Converter Gear or “Doly”<br />

Tractor/semi-trailer. (Exhibit 17) A tandem axle tractor pulling a tandem axle semi-trailer usualy<br />

40’ to 53’ long. The combination usualy has an overal length of 65-75’.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 20

Exhibit 17: Tractor/Semi-trailer<br />

Western doubles. (Exhibit 18) A single axle tractor puling two single axle trailers (usualy 28’)<br />

connected to each other with a converter gear. The combination has an overall length of 65-75’.<br />

Exhibit 18: Western Doubles<br />

Truck and trailer. (Exhibit 19) A tandem axle straight truck pulling a full trailer. The combination<br />

usualy has an overal length of 50’-75’ depending on the spacing between the axles.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 21

Exhibit 19: Truck and Trailer<br />

Truck Classifications<br />

Trucks may be classified in many different ways but the most common method uses gross vehicle<br />

weight. Manufacturers are required by law and industry standards to provide GVWR (gross<br />

vehicle weight rating) for every vehicle, divided into eight classes. The Vehicle Inventory and<br />

Use Survey (VIUS) provides fleet composition data for California (Exhibit 20).<br />

Exhibit 20: California Truck Fleet Composition<br />

Class GVWR Vehicles<br />

% of Total<br />

Vehicles<br />

Annual Miles<br />

% of Total<br />

Miles<br />

Avg. Miles<br />

1 6,000 lb or less 5,749,109 67.6% 77,953,261,227 67.1% 13,559<br />

2 6,001 to 10,000 lb 2,293,163 27.0% 27,067,965,325 23.3% 11,804<br />

3 10,001 to 14,000 lb 46,897 0.6% 742,912,501 0.6% 15,841<br />

4 14,001 to 16,000 lb 25,135 0.3% 414,865,297 0.4% 16,505<br />

5 16,001 to 19,500 lb 5,144 0.1% 41,011,297 0.0% 7,973<br />

6 19,501 to 26,000 lb 182,826 2.1% 2,349,220,285 2.0% 12,849<br />

7 26,001 to 33,000 lb 32,270 0.4% 1,260,160,254 1.1% 39,051<br />

8 33,001 lb and greater 170,149 2.0% 6,321,962,604 5.4% 37,155<br />

Total 8,504,693 100.0% 116,151,358,790 100.0% 13,657<br />

Source: Vehicle Inventory and User Survey Data (VIUS), U.S. Census Bureau<br />

The silhouette drawings (Exhibit 21) suggest the variety of body types and applications within<br />

each weight classification.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 22

Exhibit 21: Class 1-8 Gross Vehicle Weight Classifications<br />

The number of Clas 1 and 2 light trucks overwhelms the “truck” population (Exhibit 22), as<br />

these include vans, SUVs, and pickups used for personal transportation and incidental service or<br />

goods movement trips. These two clases represent over 90% of the California “trucks” in use.<br />

Exhibit 22: California Truck Classifications<br />

T r u c k s<br />

7 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

6 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

5 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

4 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

3 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

L IG H T<br />

T R U C K S<br />

2 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

1 ,0 0 0 ,0 0 0<br />

M E D IU M<br />

T R U C K S<br />

H E A V Y<br />

T R U C K S<br />

-<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8<br />

V e h ic le C la s s<br />

Source: Source: Vehicle Inventory and User Survey Data (VIUS), U.S. Census Bureau<br />

Class 3-5 Trucks<br />

By many definitions, “trucks” start at Clas 3. The population of Classes 3 through 5 is definitely<br />

a minority of the total count. (Exhibit 20) These light-to-medium duty trucks are heavily concentrated<br />

in private fleets for local goods movement and services. In recent years, the number and<br />

proportion of Class 3–5 trucks has been increasing. The growing demand for more vehicles of<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 23

this size is related to increasing population in metropolitan centers, changes in inventory practices,<br />

greater demand for expedited services, greater demand for parcel and express services, and<br />

the growth of the service industry.<br />

Exhibit 23 illustrates the wide variety of body types within the medium-duty group, in this case<br />

Class 5 vehicles of 16,001-19,500 lbs GVWR. In particular, the medium duty trucks are well<br />

suited for service applications that require truck-mounted equipment such as utilities, landscaping,<br />

and towing. Medium duty chassis are also used for motor homes, shuttle buses, and other<br />

passenger and recreational applications.<br />

Exhibit 23: Medium-duty Truck Body Type Examples<br />

School Bus Cube Ambulance<br />

Shuttle Bus Motor Home Rolloff<br />

Service Snow Removal Landscaping Dump<br />

Flatbed Utility Stake<br />

Class 6-8 Trucks<br />

Class 6 trucks are sometimes classified as medium-duty, while Class 7 trucks are usually classified<br />

as heavy-duty. The differences can be minimal. Some chassis are sold as either Class 6 or<br />

Class 7 depending on the engine and running gear installed.<br />

Clas 7 and Clas 8 vehicles include the “18 wheelers” and dominate the intercity activity on the<br />

major highways. In an urban area, Class 7 and Class 8 vehicles are also prominent, but the reason<br />

is a combination of factors. First, there are the intercity vehicles that happen to be in the urban<br />

area at the time of picking up, delivering or transiting goods. Second, there are the local<br />

trucks that do not leave the area. Local sub-sectors of the trucking industry such as dump trucks<br />

hauling aggregates, tank trailer haulers, and intermodal trucking use Class 8 tractors but operate<br />

within a given metropolitan area.<br />

The body types in Exhibit 24 illustrate the variety of Class 6 and Class 7 applications. These<br />

units are also configured as tractors for short-haul use with semi-trailers, particularly in urban<br />

areas for local pickup and delivery, as shown in Exhibit 25.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 24

Exhibit 24: Heavy-duty (Class 6-7) Truck Body Type Examples<br />

Exhibit 25: Tractor and 28-foot “Pup” Trailer<br />

Source: Tioga Group photo<br />

Class 8 trucks (33,000 lbs. and over) are heavy-duty vehicles by any definition. Class 8 includes<br />

both straight trucks and tractors for use with semi-trailers. Exhibit 26 shows Class 8 tractors in<br />

semi-trailer applications.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 25

Exhibit 26: Class 8 Tractors & Semi-Trailers<br />

By some estimates, there are roughly 20 million trucks in the United States of which a little more<br />

than 10% are the Clas 8 heavy duty vehicles, or “big rigs,” commonly asociated with “trucking”.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

39% of the vehicles are in common carrier fleets such as Con-Way West or Roadway.<br />

25% of the vehicles are in private fleets that serve commercial businesses, particularly<br />

wholesale and retail delivery, construction, and mining.<br />

24% are in private-like fleets, mostly government, such as PG&E, telephone companies,<br />

or Caltrans.<br />

12% are in lease/rental fleets such as Penske or Ryder Truck Rental, which in operation<br />

would be divided primarily between the commercial carriers and the private<br />

business fleets.<br />

Truck Type Applications<br />

Exhibit 27 shows, in the shaded entries, the GVWR classes typically used in three kinds of trucking.<br />

As the diagram suggests, service providers make much more use of light GVWR Class 1<br />

and Class 2 vehicles than freight haulers on either the long-haul or local levels. The major area<br />

of overlap in light-duty trucks is likely to be in Class 2, which includes some parcel delivery vehicles,<br />

and Class 3, which includes a broader array of parcel, delivery and other light freighthauling<br />

trucks.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 26

Exhibit 27: Truck Types and Applications<br />

Over-the<br />

–Road<br />

Point-to-<br />

Point<br />

Autos,<br />

SUVs,<br />

Minivans<br />

Pickups,<br />

Vans<br />

Utility<br />

Light<br />

Trucks<br />

10,000+<br />

lb<br />

GVWR<br />

Class 1 Class 2 Class 3<br />

Class<br />

4<br />

Medium Trucks<br />

14,000+ lb GVWR<br />

Class<br />

5<br />

Class<br />

6<br />

Heavy Trucks<br />

26,000+ lb<br />

GVWR<br />

Class<br />

7<br />

Class<br />

8<br />

Pickup &<br />

Delivery<br />

Local<br />

Networks<br />

Class 1 Class 2 Class 3<br />

Class<br />

4<br />

Class<br />

5<br />

Class<br />

6<br />

Class<br />

7<br />

Class<br />

8<br />

Service,<br />

Diffuse<br />

Networks<br />

Class 1 Class 2 Class 3<br />

Class<br />

4<br />

Class<br />

5<br />

Class<br />

6<br />

Class<br />

7<br />

Class<br />

8<br />

Exhibit 28 shows the uses of heavy duty trucks, the classes that are most visible to the public as<br />

“trucks”.<br />

<br />

<br />

Only about a third of the heavy-duty trucks are used in for-hire trucking (e.g. hauling<br />

other people’s goods for pay).<br />

Two-thirds of the heavy-duty trucks are used by private firms (hauling their own<br />

goods), service industries, or government<br />

Exhibit 28: Heavy Duty Truck Uses - 1997<br />

8%<br />

For Hire<br />

15%<br />

32%<br />

Construction<br />

M ining<br />

Utilities<br />

Forestry<br />

8%<br />

M anufacturing<br />

Retail<br />

6%<br />

6%<br />

3%<br />

2%2%<br />

18%<br />

Service<br />

Agriculture<br />

Wholesale<br />

Private fleets are overwhelmingly used in local and regional business. (Exhibit 29) A very large<br />

part of the total trucking activity is therefore carried out by local and regional carriers, contrac-<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 27

tors, and fleet operators whose names are not familiar to the general public. This perspective<br />

contrasts with a common asociation of “trucking” with large semi-trailers bearing prominent<br />

trucking company names moving over long distances.<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

Exhibit 29: Private and For-Hire Length of Haul<br />

1997 California Shipments: Truck LOH Distribution<br />

70%<br />

Sh 60%<br />

are<br />

of<br />

50%<br />

To<br />

ns<br />

40%<br />

For-Hire Truck<br />

Private Truck<br />

Parcel & USPS<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Exhibit 30: Truck Payloads (Fresno COG Model)<br />

MHDT Payload<br />

HHDT Payload<br />

Commodity Description<br />

Long-<br />

Long-<br />

Local<br />

Local<br />

Distance<br />

Distance<br />

Farm Products 4.8 7.2 11.5 13.9<br />

Forest Products 1.1 13.3 3.0 15.6<br />

Fresh fish or other marine products 3.3 8.8 6.3 12.2<br />

Metallic Ores 7.0 8.8 7.0 5.9<br />

Coal 7.0 8.8 7.0 5.9<br />

Crude Petroleum, natural gas or gasoline 2.6 14.1 3.9 13.1<br />

Nonmetallic minerals 7.0 14.1 7.0 5.9<br />

Ordinance or accessories 3.4 4.9 8.2 10.1<br />

Food and kindred products 3.3 8.8 6.3 12.2<br />

Tobacco products 4.8 7.2 12.6 14.2<br />

Textile mill products 1.5 3.5 6.4 10.8<br />

Apparel or other finished textile products 1.5 3.5 6.4 10.8<br />

Lumber or wood products 2.5 10.2 9.0 12.1<br />

Furniture or fixtures 0.8 0.9 3.5 9.4<br />

Pulp, paper or allied products 3.2 19.1 7.1 13.9<br />

Printed matter 3.2 19.1 7.1 13.9<br />

Chemicals or allied products 8.3 12.2 3.7 12.1<br />

Petroleum or coal products 2.6 14.1 3.9 13.1<br />

Rubber or miscellaneous plastic products 0.5 6.7 3.8 10.7<br />

Leather or leather products 1.5 3.5 6.4 10.8<br />

Clay, concrete, glass or stone products 2.6 10.1 9.5 10.8<br />

Primary metal products 1.4 5.4 6.1 9.3<br />

Fabricated metal products 1.4 1.9 6.9 8.0<br />

Machinery excluding electrical 2.2 8.0 4.2 11.0<br />

Electrical machinery, equipment or supplies 2.2 8.0 4.2 11.0<br />

Transportation equipment 1.2 1.3 4.2 10.5<br />

Instruments, photographic goods, optical goods 1.5 6.1 3.4 12.0<br />

Miscellaneous products of manufacturing 2.2 6.1 8.6 10.0<br />

Miscellaneous mixed freight 3.4 4.9 8.2 10.1<br />

Hazardous waste or materials 3.4 13.6 4.0 10.2<br />

Unweighted Average 3.0 8.5 6.3 11.0<br />

Although the experience of individual truck fleet operators and customers may vary widely, the<br />

numbers reveal some instructive tendencies.<br />

<br />

<br />

Local movements are significantly lighter than long-distance moves. In fact, the local<br />

average shown are only half the long-distance averages. This is consistent with<br />

the tendency to make more partially loaded trips in local service. In particular,<br />

trucks making a series of calls on a local route will usually be only partly filled at<br />

any given time.<br />

Few trucks are loaded to their full weight capacity. The heaviest average weights<br />

are shown for forest products (e.g. logs or wood chips, not finished lumber). While<br />

a Class 8 tractor and semi trailer may technically be able to carry twenty tons or<br />

more, the average of the weights shown for long-haul, heavy duty trucks is just 11<br />

tons and the range is 5.9 to 15.6 tons.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 29

Trucking <strong>Movement</strong> Patterns<br />

Local trucking movements include pickups (gathering or assembly), delivery (distribution),<br />

empty movement (repositioning or stem miles), and an endless variety of combinations. Residential<br />

customers of United Parcel Service, FedEx Express and other parcel carriers tend to view<br />

them as delivery services, while commercial customers see them as both delivery and pickup<br />

services.<br />

In contrast, inter-regional truckload trips typically enter the region to deliver an inbound load at a<br />

local destination, reposition the empty trailer to another shipper to pick up an outbound load, and<br />

then depart the region. The empty repositioning move may originate and terminate in the local<br />

area, but is treated as part of the inter-regional freight movement. A more perplexing case is<br />

when a “long-haul” truckload carier takes a local load in the course of repositioning for a longhaul<br />

assignment.<br />

The “goods” or “freight” being picked up and delivered in local trucking can include waste, returned<br />

goods, recyclables, etc. Examples of such movements include the following:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Garbage and recycling pickups.<br />

Hazardous and biohazard materials pickups for disposal.<br />

Empty pallets, bins, and other shipping containers being returned empty.<br />

Construction debris or excavation spoils.<br />

Used equipment, vehicles and goods of all kinds<br />

Historically, commercial trucking services were divided into those with fixed, repetitive routes<br />

and “iregular route” cariers whose origins and destination varied with the shipment. Deregulation<br />

and other changes have erased the official designations, but there are still only a few basic<br />

trucking patterns (Exhibit 31).<br />

Exhibit 31: Generalized Truck Trip Patterns<br />

(Repeats on itself)<br />

Hub and spoke<br />

Irregular route<br />

Fixed route<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 30

Hub and Spoke. These are long haul, multi-national, inter-city networks operated<br />

by commercial LTL and parcel carriers. Typically the carrier gathers small shipments<br />

at multiple local terminals, shuttles them to regional hubs, where shipments<br />

are consolidated into larger trucks for over-the-highway (OTR) movement to local<br />

terminals for intra-city operations. At destination, the shipments are sorted and<br />

transferred into smaller trucks for local delivery. UPS, USPS, FedEx Ground,<br />

FedEx Freight, Yellow Roadway, Conway and other nationally known parcel and<br />

LTL carriers operate this way.<br />

Irregular Route. Truckload shipments usually move directly from origin to destination.<br />

If the shipment is local and repetitive, the truck may return to origin empty.<br />

However, for regional and long haul movements the truck must be “repositioned”<br />

empty to its next load. Trucks and drivers move from assignment to assignment,<br />

and may never follow the same pattern twice.<br />

Fixed Route. The archetypical pattern for local trucking is delivery of small shipments<br />

along a fixed route within a given city. Mail delivery is a familiar example.<br />

The actual route may be fixed, as in mail delivery, or may vary within a territory, as<br />

in UPS or FedEx Ground parcel service. The patern can apply to “descending”<br />

loads (the truck starts out ful and ends up empty after making deliveries), “ascending”<br />

loads (the truck starts out empty and ends up ful after making pickups), or a<br />

combination (which usually is the case with mail).<br />

There are common variations on each of the above.<br />

The “spoke” portion of intercity hub and spoke networks is typicaly some variation<br />

on fixed routes but not necessarily daily.<br />

Some intercity routes can have very fixed patterns in terms of timing and locations.<br />

Some intra-city routes can be very irregular when responding to demand that is<br />

placed with very short notice such as emergency shipments.<br />

These general transportation patterns apply to both freight movement and service delivery and<br />

each can be observed in endless variations and combinations. The rail, air, marine, and pipeline<br />

modes do not have the pickup and delivery flexibility of trucks and operate almost exclusively in<br />

hub-and-spoke patterns.<br />

Trucking Cost Structure<br />

Commercial trucking is a highly competitive, low-margin business that is easy to enter. An operator<br />

can start a busines with a commercial driver’s license, a cel phone, and a one-month<br />

rental payment on a used tractor. A broker only needs the cell phone. There is very little difference<br />

in the services offered by the thousands of interstate truckload carriers vying for business<br />

from customers negotiating for lowest price. These factors drive down profit margin, and force<br />

successful truckers to pay close attention to cost control.<br />

Each part of the trucking industry has a distinctive breakdown of cost categories. There is a particular<br />

difference in the amount of transportation service that is purchased from others, princi-<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 31

pally from owner-operators who supply themselves as drivers of their own tractors pulling trucking<br />

company or private fleet loads.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Less-Than-Truckload (LTL) firms rarely purchase transportation, and typically<br />

have employee drivers.<br />

Truckload (TL) firms typically spend about 20% of the their total expenses on purchased<br />

transportation, some are 100% purchased transportation meaning they use<br />

no company employees as drivers<br />

Private fleet operators are predominately company employees; use of owneroperators<br />

does occur but often with the owner-operator as a contract motor carrier.<br />

Owner-Operators, by definition, do not purchase transportation from others, but<br />

rather sell capacity to fleet operators.<br />

Exhibit 32 estimates the amount of total expense devoted to for purchased transportation and reports<br />

that figure as the total “sales” for owner-operators. The breakdown for owner-operators is<br />

then used to allocate this total between labor (themselves), fuel, and equipment.<br />

Exhibit 32: Trucking Industry Composite Expense Shares<br />

Equipment &<br />

Maintenance<br />

18%<br />

Insurance<br />

4%<br />

Administration<br />

4%<br />

Fuel<br />

24%<br />

Compensation<br />

& Benefits<br />

(labor)<br />

50%<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

About half of all trucking costs are labor–direct compensation and benefits–<br />

which are paid locally.<br />

Fuel is about one-quarter of the total cost. Most of the firms headquartered or located<br />

in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region are regional or local truckers, rather than the long-haul<br />

specialists headquartered in the Midwest and elsewhere.<br />

Equipment–buying or leasing trucks and maintaining them–is about 18%, or<br />

nearly one-fifth the total. The equipment may be sourced in the region or nationally,<br />

but virtually all maintenance labor, replacement parts, and tire purchases are local.<br />

The “overhead” categories of administration and insurance each account for about<br />

5% of the total and are local expenditures for compensation, fees, rents, communications,<br />

etc.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 32

Private fleets account for more than half of the total expenditures, and those firms are probably<br />

drastically under-represented in the databases.<br />

Truck Fleet Locations<br />

Trucking fleets are based in many locations in the study area but they tend to cluster near heavy<br />

industrial areas, low rent commercial areas, freeways, or customers. Some trucking facilities are<br />

multi-user sites where one party owns or leases the site and act as a landlord to other trucking<br />

companies. All trucking facility sites tend to have basic provisions for security, auto parking,<br />

finished surfaces, and access to main roadways.<br />

Due to high land costs in metropolitan areas in California, businesses such as trucking are often<br />

forced to relocate to rural areas along major highways. Relocation from urban service territories<br />

can increase VMT, aggravate peak travel hours and direction, and emit more pollutants than if<br />

the business could remain at its original location.<br />

Exhibit 33 displays the enormous number of locations in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region from which at least<br />

one commercial truck is operated. The listings include trucks used for goods movement as well<br />

as to provide services.<br />

For this <strong>Phase</strong> 1 report the project team assembled truck fleet locations from two sources:<br />

<br />

<br />

The California Highway Patrol Management Information System for Terminals<br />

(MISTER), which lists the location at which a truck should be available for inspection<br />

(red truck icons on the maps, about 3,500 records).<br />

The Yahoo! Yellow Pages which accept paid, self-descriptive listing (blue truck<br />

icons on the maps, about 400 records).<br />

The two sources result in roughly 3,900 truck terminal or company listings with valid, mapable<br />

street addresses. (Another 300–400 listings have post office boxes or non-mapable addresses.)<br />

The obvious observation from Exhibit 33 is that the trucks follow the people and the highways.<br />

The “people” provide both the owner/driverand the customers, while the highways provide the<br />

access.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 33

Exhibit 33: <strong>SACOG</strong>Truck “Terminal” Locations<br />

Besides the major concentration in the Sacramento metropolitan area there are clusters of trucking<br />

activity at other confluences of people and highways.<br />

Exhibit 34 shows a cluster of truck locations in the Yuba City/Marysville area, with most locations<br />

on the west side of the river.<br />

Exhibit 34: Yuba City-Marysville Regional Cluster<br />

Exhibit 35 shows a cluster of trucking locations in West Sacramento. A comparison of the map<br />

in Exhibit 35 with the aerial photo in Exhibit 36 reveals that the truck locations correspond to a<br />

mix of industrial, commercial, and residential areas. Residential “terminal” or trucking company<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 34

locations result from owner-operators or small businesses operating trucks from their home, or<br />

drivers and tradesmen taking commercial trucks home at night.<br />

Exhibit 35: West Sacramento Trucking Cluster<br />

Exhibit 36: West Sacramento Aerial Photo<br />

Exhibit 37 shows another cluster of trucking addresses in and near Woodland, again in a mix of<br />

industrial, commercial, and residential locations.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 35

Exhibit 37: Woodland Trucking Cluster<br />

Within the region, truck “terminals” as reflected in the MISTER database are heavily concentrated<br />

in Sacramento itself (Exhibit 38) and in Sacramento County (Exhibit 39).<br />

CITY<br />

Exhibit 38: MISTER Terminal Data by City<br />

COUNTY<br />

TRUCKS<br />

OWNED<br />

SHARE<br />

CUMULATIVE<br />

SHARE<br />

SACRAMENTO SACRAMENTO 6,050 38% 38%<br />

WEST SACRAMENTO YOLO 1,360 9% 47%<br />

WOODLAND YOLO 1,010 6% 54%<br />

YUBA CITY SUTTER 911 6% 59%<br />

MARYSVILLE YUBA 466 3% 62%<br />

ELK GROVE SACRAMENTO 451 3% 65%<br />

RANCHO CORDOVA SACRAMENTO 377 2% 68%<br />

NORTH HIGHLANDS SACRAMENTO 345 2% 70%<br />

ROSEVILLE PLACER 327 2% 72%<br />

FOLSOM SACRAMENTO 327 2% 74%<br />

AUBURN PLACER 307 2% 76%<br />

ROCKLIN PLACER 298 2% 78%<br />

GALT SACRAMENTO 296 2% 80%<br />

ALL OTHERS 3,205 20% 20%<br />

<strong>SACOG</strong> TOTAL 15,730 100% 100%<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 36

Exhibit 39: MISTER Terminal Data by County<br />

603<br />

1,668<br />

1,300<br />

2,701<br />

794<br />

8,664<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 37

III. Railroads<br />

Rail Network<br />

The rail system serving the <strong>SACOG</strong> region (Exhibit 40) is a legacy of multiple rail mergers. The<br />

lines were originally built by the Southern Pacific (SP), the Western Pacific (WP), and the Sacramento<br />

Northern (SN, a Western Pacific subsidiary).<br />

Exhibit 40: Sacramento Area Rail Lines<br />

UP Valley Subdivision<br />

to Oregon<br />

UP Canyon Subdivision<br />

to Feather River<br />

Canyon<br />

Binney<br />

Junction<br />

UP Roseville<br />

Subdivision to<br />

Donner Pass<br />

Sierra Northern at<br />

Port of Sacramento<br />

Sierra Northern at<br />

McClellan<br />

UP Martinez<br />

Subdivision to<br />

Oakland<br />

Dormant CCT<br />

Line to Lodi<br />

UP Sacramento<br />

& Fresno Subdivisions<br />

to Stockton<br />

Exhibit 41 shows how these legacy routes converge and connect in the <strong>SACOG</strong> area. The key<br />

junctions are:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Haggin, where the north-south former WP route passes under the former east-west<br />

SP route. The two routes are connected by tracks that climb from the WP route to<br />

the SP route.<br />

Elvas, where the former SP lines from the Bay Area, Fresno, and Roseville meet.<br />

Binney Junction, (off the map) north of Yuba City/Marysville, where the former SP<br />

and WP lines meet.<br />

Winnemucca, NV (off the map) where the former SP Donner Pass and WP Feather<br />

River Canyon routes meet.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 39

Exhibit 41: Sacramento Area Rail Connections<br />

HAGGIN<br />

ELVAS<br />

Railroad Facilities<br />

The railroads have several types of facilities serving the <strong>SACOG</strong> region:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

trackage and right-of-way, including line-haul routes to, from, and through the region,<br />

and a network of local trackage serving industrial customers;<br />

classification yards, where line-haul trains are made up and broken down, freight<br />

cars are classified into groups, and local trains arrive and depart;<br />

local or industrial yards, serving similar functions as classification yards but on a<br />

smaller scale;<br />

transload facilities where bulk or other commodities are transferred between freight<br />

cars and trucks, and may also be stored or processed; and<br />

maintenance facilities, where locomotives and freight cars are serviced and maintained,<br />

and light repairs are made.<br />

There are two other kinds of railroad facilities that are not present in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region: intermodal<br />

terminals, and auto loading terminals.<br />

Intermodal terminals (also caled “intermodal ramps”, “piggyback ramps”, or just “ramps”) are<br />

facilities where containers or trailers are transferred between rail and truck modes. Virtually all<br />

such terminals use mechanized lift equipment to make the transfer (Exhibit 42).<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 40

Exhibit 42: Mechanized Intermodal Lift Equipment<br />

Trailers or containers on chassis are parked awaiting either outbound loading or inbound pickups<br />

by local truckers. Most of the land occupied by intermodal terminals is parking (Exhibit 43).<br />

Exhibit 43: Typical Intermodal Terminal–BNSF Stockton<br />

The <strong>SACOG</strong> region does not have an intermodal terminal, but is served from major regional<br />

terminals in Oakland, Richmond, North Richmond (dedicated to UPS), Stockton, Lathrop, or<br />

Sparks. Exhibit 44 shows the terminal locations and 75-mile local trucking zones around each.<br />

As indicated, most of the <strong>SACOG</strong> region is covered from existing terminals.<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 41

Exhibit 44: Northern California/ Nevada Rail Intermodal Terminals<br />

Intermodal operations have strong scale effects in both economics and service. Railroads are<br />

very reluctant to establish new terminals in markets that can be served from existing locations.<br />

An intermodal terminal in the <strong>SACOG</strong> region is therefore both unlikely and unnecessary for the<br />

near future.<br />

Auto loading facilities (“auto ramps”) are locations where autos and light trucks are transferred<br />

between specialized rail cars (“Auto racks”) and equaly specialized trucks. (Exhibit 45) At origins,<br />

typically ports or assembly plants, autos are loaded onto rail cars for national distribution.<br />

At destinations, autos are unloaded from rail cars for regional distribution by truck.<br />

Exhibit 45: Rail Auto Loading Facility (Richmond)<br />

090906 <strong>Final</strong> <strong>SACOG</strong> <strong>Phase</strong> 1 <strong>Goods</strong> <strong>Movement</strong> <strong>Report</strong> THE TIOGA GROUP<br />

Page 42

Some facilities, such as the ones at the Port of Benicia (Exhibit 46), are both origins and destinations.<br />

At the Port of Benicia one facility receives imported Toyotas by ship and transfers them to<br />

rail cars for national distribution and to trucks for local distribution. At the other Benicia terminal,<br />

domestic autos are received by rail and shipped out by truck.<br />

Exhibit 46: Northern California Rail Auto Terminals<br />

Facilities at the Port of Richmond and the adjacent BNSF terminal (Exhibit 45) can likewise<br />