May-June 2013 Issue - American College of Phlebology

May-June 2013 Issue - American College of Phlebology

May-June 2013 Issue - American College of Phlebology

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

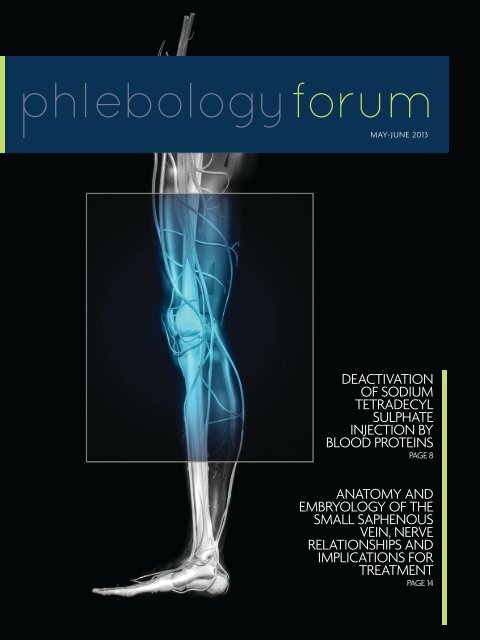

MAY-JUNE <strong>2013</strong><br />

Deactivation<br />

<strong>of</strong> sodium<br />

tetradecyl<br />

sulphate<br />

injection by<br />

blood proteins<br />

PAGE 8<br />

Anatomy and<br />

embryology <strong>of</strong> the<br />

small saphenous<br />

vein, nerve<br />

relationships and<br />

implications for<br />

treatment<br />

PAGE 14

Deactivation <strong>of</strong> sodium<br />

tetradecyl sulphate<br />

injection by blood<br />

proteins<br />

contents<br />

may-jun ‘13<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer:<br />

From the<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Dr. Nick Morrison 5<br />

Neil Sadick, MD, FACP, FACPh, FAAD, FAACS<br />

Associate Editor:<br />

Ted King MD, FAAFP, FACPh<br />

8<br />

Foot-sparing<br />

postoperative<br />

compression bandage:<br />

a possible alternative<br />

to the traditional<br />

bandage<br />

Anatomy and<br />

embryology <strong>of</strong> the<br />

small saphenous vein,<br />

nerve relationships<br />

and implications for<br />

treatment<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer:<br />

Hugo Partsch, MD<br />

Associate Editor:<br />

Mitchell Goldman, MD, FACPh<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer:<br />

Mark Isaacs, MD<br />

Associate Editor:<br />

11 14<br />

Pauline Raymond-Martimbeau, MD, FACPh<br />

Prevention <strong>of</strong> venous<br />

thromboembolism:<br />

the Seventh ACCP<br />

Conference on<br />

Antithrombotic and<br />

Thrombolytic Therapy<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer:<br />

Amjad T. AlMahameed, MD, MPH<br />

Associate Editor:<br />

Stephanie Dentoni, MD<br />

17

the world<br />

<strong>of</strong> vein care<br />

unites in Boston this September<br />

Hosted by the <strong>American</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phlebology</strong> in conjunction with the International Union <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phlebology</strong>, the XVII UIP<br />

World Meeting will bring together respected faculty, physicians and health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionals from across the globe<br />

this September 8-13 to showcase the most advanced research, technology and treatments in the field <strong>of</strong> vein care.<br />

This truly historic event will include sessions covering the wide<br />

spectrum <strong>of</strong> phlebology, including:<br />

+ More than 300 internationally recognized speakers<br />

from around the world<br />

+ Innovative and clinically relevant educational sessions<br />

+ Hands-on simulation workshops and demonstrations<br />

with international faculty<br />

+ More than 85 event exhibitors showcasing the world's<br />

most advanced products, pharmaceuticals and<br />

medical devices<br />

+ Opportunities for all levels <strong>of</strong> skill, from basic through<br />

advanced, to improve your practice and patients' care<br />

Join the ACP at the XVII UIP World Meeting in Boston, September 8-13 for this extraordinary event.<br />

UNION INTERNATIONALE DE PHLEBOLOGIE<br />

INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PHLEBOLOGY<br />

World Meeting <strong>of</strong> the International Union <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phlebology</strong><br />

/// September 8–13, <strong>2013</strong><br />

Hynes Convention Center • Boston, Massachusetts • USA<br />

HOSTED BY<br />

510.346.6800 | www.uip<strong>2013</strong>.org | www.phlebology.org<br />

advancing vein care

<strong>2013</strong> Compression Hosiery and<br />

support Wear Buyer’s Guide<br />

n Everything you need to know about over-the-counter<br />

and medical compression therapy products<br />

n Photos and detailed product information from eleven<br />

manufacturers<br />

n Compression stockings, pantyhose, thigh-highs,<br />

maternity, travel and sports socks, plus lymphedema<br />

products and armsleeves<br />

n Direct-from-the-factory discounts for individuals or<br />

medical pr<strong>of</strong>essionals<br />

www.BrightLifeDirect.com<br />

Your one-stop shop for<br />

compression therapy.<br />

to request your FREE copY<br />

or Call 1-877-545-8585<br />

6925-D Willow Street NW • Washington, DC 20012<br />

Find tREatmEnt solutions FoR<br />

Tired & Achy Legs • Varicose Veins • Vascular Disease • Swelling & Lymphedema • Ulcers • Fragile/Sensitive Skin • DVT Prevention<br />

View past issues <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phlebology</strong> Forum at<br />

www.phlebology.org

disclosure<br />

<strong>of</strong> interests<br />

Name ACP Role Date<br />

Submitted<br />

Disclosure<br />

Stephanie Dentoni, MD Recruitment & Retention (Chair) 6/25/12 Nothing to Disclose<br />

Mark Forrestal, MD, FACPh ACP 6/25/12 New Star Lasers Cooltouch: Speaker, Trainer<br />

Mitchel Goldman, MD,<br />

FACPh<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong> Forum Task Force 2/14/<strong>2013</strong> <strong>American</strong> Society for Dermatologic Surgery,<br />

President-Elect; Merz Aesthetics/Kruesler,<br />

Consultant<br />

Jean-Jerome Guex, MD,<br />

FACPh<br />

ACP BOD, Communications,<br />

Standing Committee,<br />

Leadership Development, UIP<br />

<strong>2013</strong> Task Force, AMA HOD<br />

Task Force, International Affairs<br />

(Chair),<br />

6/14/12 Kreussler: Speaker; Sigvaris: Speaker, Investigator,<br />

Consultant; Innotech: Principal Investigator; Pierre<br />

Fabre: Consultant; Boerighr Ingelheim: Consultant,<br />

Medical Writer; Servier: Investigator, Consultant,<br />

Speaker<br />

Lowell Kabnick, MD, FACS,<br />

FACPh<br />

UIP <strong>2013</strong> Task Force 7/17/12 Angiodynamics: Consultant, Shareholder, Patent;<br />

Vascular Insights: Scientific Advisory Board<br />

Neil Khilnani, MD, FACPh<br />

ACP BOD, Member Services<br />

(Chair)<br />

7/24/12 Sapheon: Data Safety Board Member<br />

Ted King, MD, FAAFP, FACPh<br />

ACP BOD, Leadership<br />

Development, PES-QM Task<br />

Force, Public Education<br />

6/14/12 BTG: Investigator; Merz: Speaker<br />

Mark Meissner, MD<br />

ACP BOD, Education Standing<br />

Committee<br />

7/13/12 Nothing to Disclose<br />

Nick Morrison, MD, FACS,<br />

FACPh<br />

UIP <strong>2013</strong> Task Force (Chair),<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong> Forum Task Force<br />

(Chair), Annual Congress<br />

Planning Committee (Chair)<br />

6/13/12 Medi: Speakers Bureau; Merz: Speakers Bureau;<br />

Sapheon: Principle Investigator; VeinX: Scientific<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Eric Mowatt-Larssen, MD ACP CME Committee 6/25/12 BTG International, Inc.: Consultant<br />

Diana Neuhardt, RVT, RPhS<br />

ACP BOD, Member Services,<br />

Audit, UIP <strong>2013</strong> Task Force,<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong> Forum Task<br />

Force, Veinline, Recruitment<br />

& Tetention, CME, Distance<br />

Learning, Public Education<br />

(Chair)<br />

6/15/12 Nothing to Disclose<br />

Pauline Raymond-<br />

Martimbeau, MD, FACPh<br />

UIP <strong>2013</strong> Task Force 6/22/12 Nothing to Disclose<br />

6

From the<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Dear Readers<br />

In this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Phlebology</strong> Forum you will find a number <strong>of</strong> topics<br />

related to deep and superficial venous problems, many <strong>of</strong> which expand<br />

our understanding <strong>of</strong> what we see and can do on a practical basis in<br />

daily work. Included are an investigation into the deactivation <strong>of</strong> STS<br />

sclerosant which may help explain the varied clinical outcomes we all see;<br />

an introduction to the vagaries <strong>of</strong> small saphenous vein and associated<br />

nerve anatomy and their clinical implication; relevant clinical information<br />

regarding post-treatment compression therapy which adds to the dogmachallenging<br />

discussion <strong>of</strong> compression; and an excellent analysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ACCP guidelines for thromboprophylaxis.<br />

And finally, I will beat the drum on behalf <strong>of</strong> the ACP and the Organizing<br />

Committees for the UIP XVII World Congress in Boston, and I can promise<br />

this meeting will be one <strong>of</strong> the best “vein” meetings you have ever<br />

attended and will greatly exceed your expectations. The countdown is<br />

now less than 3 months and I have only three other things to say about<br />

the meeting: BOSTON! BOSTON! BOSTON!<br />

Nick Morrison, MD<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong> Forum<br />

7

Deactivation <strong>of</strong> sodium<br />

tetradecyl sulphate<br />

injection by blood proteins<br />

Watkins MR.<br />

Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011 Apr;41(4):521-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.12.012. Epub 2011 Jan 22.<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer: Neil Sadick, MD, FACP, FACPh, FAAD, FAACS<br />

Associate Editor: Ted King MD, FAAFP, FACPh

COMMENTARY<br />

The clinical phlebologist is well aware that<br />

sclerosants act at limited areas <strong>of</strong> clinical activity<br />

from the point where they are injected. In the past,<br />

it was felt that this clinical observation was related<br />

to the dilution <strong>of</strong> the sclerosant and its subsequent<br />

decreased potency in this regard, based solely upon<br />

concentration/sclerosant endothelial interaction<br />

kinetically.<br />

in practical use, it<br />

would take less than<br />

0.5% ml <strong>of</strong> whole<br />

blood to deactivate<br />

1 ml <strong>of</strong> 3% STS<br />

In addition, a commonly known observation is that foam sclerosants manifest greater potency and also have more significant<br />

distal watershed-type effect. With these tenets in mind, the article entitled “Deactivation <strong>of</strong> sodium tetradecyl sulphate<br />

injection by blood protein” brings new insight and rationale into the actual pathophysiologic mechanisms <strong>of</strong> this clinical<br />

observation.<br />

The present study looked at the volume <strong>of</strong> blood required to inactivate 1ml <strong>of</strong> 3% sodium tetradecyl sulphate. This was<br />

accomplished by measuring the concentration <strong>of</strong> sodium tetradecyl sulphate (STS) remaining in the active state in an in-vitro<br />

stock solution after adding increasing volumes <strong>of</strong> solution containing either bovine serum albumin or red blood cells or a<br />

mixture <strong>of</strong> both components. The two methodologies utilized to assess the results included autotritation and colorimetry.<br />

Results <strong>of</strong> the aforementioned study showed that STS is deactivated by blood proteins in a linear fashion. The protein<br />

solution utilized seemed to make little difference, with approximately 2 ml <strong>of</strong> 4% protein solution deactivating 1 ml <strong>of</strong> a 3%<br />

STS solution.<br />

The authors hypothesized that titration measured the free STS remaining in solution after the addition <strong>of</strong> blood proteins<br />

which would bind and deactivate the STS and this correlates with clinical activity. These results suggest that in practical<br />

use, it would take less than 0.5% ml <strong>of</strong> whole blood to deactivate 1 ml <strong>of</strong> 3% STS which would explain why an empty vein<br />

technique is important when injecting liquid sclerosant in the varicose veins, a concept that is well-documented in clinical<br />

practice since its description by Orbach. 1<br />

This would explain the noted limited distance <strong>of</strong> clinical efficacy <strong>of</strong> injected liquid sclerosants.<br />

Limitation <strong>of</strong> this study would include its in-vitro design and qualitative visual assessment as related to the colorimetric<br />

assay employed in the study design. The authors also confirm that it was difficult to visually determine the end point <strong>of</strong><br />

titration with increasing volumes <strong>of</strong> blood proteins, which is why the average <strong>of</strong> up to four individual readings was utilized.<br />

1 Orbach EJ. Sclerotherapy <strong>of</strong> varicose veins—utilization <strong>of</strong> an intravenous air block. Am J Surg 1944;LXVI(3):362–6.<br />

9

Therefore, the results should be interpreted as a guide rather than an exact figure.<br />

The aforementioned article is <strong>of</strong> great clinical importance to the practicing phlebologist although it is not without<br />

limitations in terms <strong>of</strong> its design. This is one <strong>of</strong> the few articles in the literature which would attempt to understand<br />

physiologic interactions between liquid sclerosants and blood vessels and helps to explain many <strong>of</strong> the clinical observations<br />

noted by the practicing phlebologist.<br />

The characteristics <strong>of</strong> sclerosants that the practicing phlebologist considers in choosing an agent for daily clinical practice<br />

include efficacy, which is <strong>of</strong>ten dependent upon its strength and thus the ability to induce pan endothelial destruction and<br />

its distal downstream clinical efficacy from the site <strong>of</strong> initial injection. 2 Other considerations include its minimal sclerosant<br />

concentration, which will achieve pan endothelial destruction. 3 Allergenicity and side effect pr<strong>of</strong>iles are important<br />

considerations in this regard. 4<br />

Other investigators have utilized cell lysis and human blood plasma looking at the lytic effect <strong>of</strong> STS on red blood cells,<br />

platelets and cultured endothelial cells. 5 The main difference between the other studies and this work is that in other studies<br />

the lytic effects <strong>of</strong> the sclerosants on blood and endothelial cells in the presence <strong>of</strong> blood proteins were measured, whereas<br />

the present study quantifies the residual STS remaining after the addition <strong>of</strong> protein in a standard STS solution. However,<br />

with analysis <strong>of</strong> both sets <strong>of</strong> results it is clear that a low volume <strong>of</strong> blood (0.50 ml) is enough to neutralize 1 ml <strong>of</strong> 3% STS.<br />

There are several clinical implications that can be taken from these studies. First, displacement <strong>of</strong> blood prior to treating a<br />

vein (Empty Vein Technique) may improve clinical efficacy. Second, foam sclerotherapy, which displaces more blood than<br />

liquid sclerosants, may explain its greater efficacy. However, this is less obvious with larger vessels where more treatment<br />

may be necessary because foam is less efficient at displacing blood as veins get larger.<br />

Finally, repeated puncture instillations at frequent intervals may be more effective in treating larger veins because <strong>of</strong> the<br />

displacement <strong>of</strong> blood, and the practitioner may even consider utilizing tumescent techniques to decrease red blood cell<br />

volume as an additional augmenting maneuver. 6<br />

In summary, it appears from this and other published studies and clinical experience that it is a combination <strong>of</strong> chemical<br />

interactions and host factors that determine clinical outcomes with regard to the utilization <strong>of</strong> liquid sclerosants.<br />

2 Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Zumaeta-Garcia M, Elamin MB, Duggirala MK, Erwin PJ, Montouri VM, Gloviczki P. A Systematic review and meta-analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

the treatments <strong>of</strong> varicose veins. J. Vasc Surg. 2011; 53(5 Suppl): 495-655.<br />

3 Sadick NS, Choosing the appropriate sclerosant concentration for vessel diameter. Dermatol Surg 2010;36 Suppl 2976-981.<br />

4 Cavezzi A, Parsi K. Complications <strong>of</strong> foam sclerotherapy. <strong>Phlebology</strong> 2012; 27 Suppl 146-51.<br />

5 Parsi K, Exner R, Conner DE, Herbert A, Ma DDF, Joseph JE. The lytic effects <strong>of</strong> detergent sclerosants on erythrocytes, platelets, endothelial cells and<br />

microparticles are attenuated by albumin and other plasma components in vitro. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008; 36(2): 216-223.<br />

6 Ramelet A-A. Sclerotherapy in tumescent anesthesia <strong>of</strong> reticular veins and telangiectasia’s. Dermatol Surg 2012; 38(5): 748-751.<br />

10

Foot-sparing postoperative<br />

compression bandage:<br />

a possible alternative to the<br />

traditional bandage<br />

Author: Ricci S, Moro L, Trillo L, Incalzi RA.<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong>. <strong>2013</strong> Feb;28(1):47-50.<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer: Hugo Partsch, MD<br />

Associate Editor: Mitchell Goldman, MD, FACPh<br />

11

Abstract<br />

Objectives: the aim <strong>of</strong> this study was to evaluate the<br />

efficacy and tolerability <strong>of</strong> foot sparing bandages after<br />

varicose vein surgery performed in CEAP C2 patients.<br />

Methods: 90 consecutive lower extremities in 129<br />

patients, for whom different kinds <strong>of</strong> varicose vein<br />

surgery were performed, received inelastic footsparing<br />

bandages for one week. The bandages consist<br />

<strong>of</strong> thin polyurethane under- wraps, cotton pads<br />

selectively placed over operated tracks and <strong>of</strong> 10 cm<br />

wide adhesive bandages (Fortelast® Lohmann). In order<br />

to prevent slippage acrylic glue wraps are attached<br />

to the skin at the proximal end <strong>of</strong> the bandages.<br />

Patient’s satisfaction, efficacy and local effects were<br />

systematically documented.<br />

Results: High satisfaction was achieved. Measurement<br />

<strong>of</strong> the bandage pressures showed mean values <strong>of</strong> 25<br />

foot-sparing<br />

inelastic bandages<br />

after varicose<br />

vein surgery are<br />

effective, cheap<br />

and well tolerated<br />

at least in a large<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong><br />

mobile and active<br />

patients<br />

mmHg are reported in the supine position, 30 mmHg<br />

in standing and 35 mmHg during walking. Four <strong>of</strong> the<br />

first 20 cases experienced a slight morning oedema <strong>of</strong> the foot, which disappeared while walking. Therefore, in the remaining<br />

cases the foot and distal limb were covered with a custom short tubular-shaped ‘sock’ providing 10 mmHg compression, only<br />

during the first 24 hours.<br />

Conclusion: The described foot-sparing inelastic bandages after varicose vein surgery are effective, cheap and well tolerated<br />

at least in a large proportion <strong>of</strong> mobile and active patients who do not show skin changes in the gaiter area.<br />

Commentary<br />

In the last few years the value <strong>of</strong> compression after varicose vein procedures has been questioned by several investigators<br />

who used compression hosiery. Even TED stockings were applied which are definitely too weak to reduce the venous diameter<br />

<strong>of</strong> disconnected superficial veins in the upright position. 1 On the other hand strongly applied conventional bandages<br />

1 Partsch H, Mosti G, Uhl JF. Unexpected venous diameter reduction by compression stocking <strong>of</strong> deep, but not <strong>of</strong> superficial veins. Veins and Lymphatics<br />

2012; 1:e3 online.<br />

12

in addition to the application <strong>of</strong> local pads over the treated areas were shown to have considerable benefits concerning a<br />

reduction <strong>of</strong> pain and hematoma formation. 2 , 3<br />

The reported method <strong>of</strong> applying bandages starting above the ankle and sparing the foot <strong>of</strong>fers especially the advantages<br />

that the movement <strong>of</strong> the ankle joint remains unimpeded and that patients are able to put on and to wear their normal<br />

shoes. Slight edema distal to the bandage may occur after rest but disappears quickly as soon as the patient starts walking.<br />

As the authors have shown this swelling may be prevented by light compression socks.<br />

Using inelastic compression material <strong>of</strong>fers the advantage <strong>of</strong> achieving higher pressures in the upright position and during<br />

walking while the resting pressure stays in a comfortable range.<br />

We use foot-sparing compression bandages mainly after (foam-) sclerotherapy <strong>of</strong> large tributaries and after phlebectomy in<br />

the same way as the authors, just with higher pressures.<br />

The positive experience <strong>of</strong> the authors challenge the dogma that leg compression needs to provide a pressure gradient and<br />

shows that in mobile patients, even without any compression <strong>of</strong> the gaiter area, no adverse “strangulation effects” occur.<br />

It has been demonstrated that compression pressure which is higher at calf than at gaiter level is also more effective in<br />

enhancing venous pump function 4 .<br />

We are grateful to the authors for reminding us <strong>of</strong> this very efficient way <strong>of</strong> compression which can be used in a large<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> patients after venous stripping, phlebectomy and endovenous procedures.<br />

2 Lugli M, Cogo A, Guerzoni S, Petti A, Maleti O. Effects <strong>of</strong> eccentric<br />

compression by a crossed-tape technique after endovenous laser ablation <strong>of</strong> the great saphenous vein: a randomized study. <strong>Phlebology</strong>. 2009<br />

Aug;24(4):151-6.<br />

3 Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Arleo S, Partsch H. Thigh compression after great saphenous surgery is more effective with high pressure. Int Angiol. 2009<br />

Aug;28(4):274-80.<br />

4 Mosti G, Partsch H. High compression pressure over the calf is more effective than graduated compression in enhancing venous pump function. Eur J Vasc<br />

Endovasc Surg. 2012 Sep;44(3):332-6.<br />

13

Anatomy and embryology <strong>of</strong> the small<br />

saphenous vein, nerve relationships<br />

and implications for treatment<br />

Author: Uhl JF, Gillot C<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong> <strong>2013</strong>;28:4-15<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer: Mark Isaacs, MD<br />

Associate Editor: Pauline Raymond-Martimbeau, MD, FACPh<br />

14

COMMENTARY<br />

Treatment <strong>of</strong> the small saphenous vein is known to be challenging, both because <strong>of</strong> the highly variable anatomy <strong>of</strong><br />

the vein and because <strong>of</strong> vulnerability <strong>of</strong> adjacent nerves and arteries to injury. Sural nerve injury and post operative<br />

paresthesia are two <strong>of</strong> the most common complications <strong>of</strong> treatment. 1 , 2 Surgeons traditionally have limited excision<br />

<strong>of</strong> the vein to a proximal segment and rarely if ever attempt to fully expose the popliteal vein in an effort to prevent<br />

neurological or arterial complications. This anatomical<br />

review by Uhl and Gillot is fascinating in its detail<br />

and highly relevant to the surgeon or nonsurgeon<br />

phlebologist approaching treatment <strong>of</strong> the small<br />

saphenous vein. The authors are to be commended for<br />

providing such an enlightening treatise on the known<br />

embryology and anatomy <strong>of</strong> the vein, with clearly<br />

delineated correlations between the described anatomy<br />

and possible treatment complications.<br />

Going beyond the usual text descriptions, the<br />

authors make liberal use <strong>of</strong> diagrams and well labeled<br />

anatomical dissections to illustrate “high risk zones”:<br />

the ankle, the “apex <strong>of</strong> the calf” 3 , and the popliteal<br />

fossa. For example, at its termination the arch <strong>of</strong> the<br />

small saphenous vein crosses close to the tibial and<br />

medial gastrocnemius nerves. The sural nerve and two<br />

“companion” vessels are shown to be in close proximity<br />

...a thorough<br />

knowledge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

small saphenous vein<br />

and it’s surrounding<br />

structures remains<br />

mandatory. This<br />

paper should have<br />

a prominent place<br />

in the library <strong>of</strong> all<br />

physicians treating<br />

small saphenous<br />

venous insufficiency<br />

to the small saphenous vein below the calf muscles. In<br />

the ankle the origin <strong>of</strong> the vein is deep below the fascia<br />

and plexiform, with the nerve once again very closely associated.<br />

The authors, however, go beyond their anatomical descriptions to draw conclusions about clinical practice. They state,<br />

for example, that the possible existence <strong>of</strong> a short saphenous artery poses a “high risk for injection <strong>of</strong> a sclerosing<br />

1 Van Groenendael L, et al. Conventional surgery and endovenous laser ablation <strong>of</strong> recurrent varicose veins <strong>of</strong> the small saphenous vein: a retrospective<br />

clinical comparison <strong>of</strong> assessment <strong>of</strong> patient satisfaction. Plebology 2010;25:151-157<br />

2 Gibson K, et al. Endovenous laser treatment <strong>of</strong> the short saphenous vein: Efficacy and complications. J Vasc Surg April 2007 45;4:795-800<br />

3 In order to prevent confusion amongst English language readers it should be noted that “the apex <strong>of</strong> the calf” is an anatomical term used in several<br />

places in this paper by Gillot to refer to the location <strong>of</strong> the junction between the muscle <strong>of</strong> the calf and the Achille’s tendon, not the highest point <strong>of</strong><br />

the calf.<br />

15

agent”, that “a good rule for endovenous laser treatment is to remain at least 4 cm below the popliteal crease to<br />

avoid a thermal injury <strong>of</strong> the nerves” and that a detailed “triple check” by duplex ultrasound <strong>of</strong> venous flow and<br />

nearby nerves and arteries is the “best way to reduce the risk <strong>of</strong> severe arterial or nerve complications.” While such<br />

conjecture is very reasonable and intuitively appealing given the anatomical relationships so carefully delineated in the<br />

article, there is a lack <strong>of</strong> documentation to support these conclusions. Regarding the recommendation for the type <strong>of</strong><br />

duplex examination they describe, the scarcity <strong>of</strong> ultrasonographers adequately trained and skilled enough to identify<br />

not only superficial veins and tributaries but nearby nerves and small arteries makes following their recommendations<br />

utopian. As one author put it, nerves in the area <strong>of</strong> the popliteal fossa are, “always visible, never seen”. 4<br />

While good comparative studies are lacking, a recent review <strong>of</strong> the literature on treatment <strong>of</strong> the small saphenous<br />

vein would appear to confirm that endovenous treatment techniques including radi<strong>of</strong>requency heat ablation, laser<br />

ablation and ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy carry less risk <strong>of</strong> complications than surgery with better treatment<br />

outcomes. 5 One prominent surgeon has gone so far as to declare surgery for small saphenous reflux to be obsolete! 6<br />

The explanation may lie not only with the lack <strong>of</strong> perivenous trauma but also with the use <strong>of</strong> tumescent anesthesia.<br />

We know that the advent <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> tumescent anesthesia prior to endovenous catheter heat ablation treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> the great saphenous vein resulted in a drop in neurological complications, presumably because properly injected<br />

tumescent fluid not only provides anesthesia, vein compression and a fluid heat “sink” but possibly also because it<br />

peels adjacent nerves and arteries away from the wall <strong>of</strong> the target vein. One might legitimately question whether<br />

the authors’ clinical guidelines are completely justified when tumescent anesthesia is properly administered prior to<br />

treatment. Certainly it is better to err on the side <strong>of</strong> caution, however, by keeping in mind the authors’ high risk zones<br />

even when liberal tumescent anesthesia has been used.<br />

Unfortunately, there are many surgeons who have adopted endovenous treatment techniques but are unwilling or<br />

unable to wean themselves from the operating room and general anesthesia. Likewise, proper administration <strong>of</strong><br />

tumescent anesthesia under ultrasound guidance is a challenging skill to learn even for those motivated to adopt it,<br />

and heat ablation done under tumescent anesthesia is far from risk free. Some practitioners do not use direct real-time<br />

ultrasound guidance during their procedures. For these reasons amongst others a thorough knowledge <strong>of</strong> the small<br />

saphenous vein and its surrounding structures remains mandatory. This paper should have a prominent place in the<br />

library <strong>of</strong> all physicians treating small saphenous vein insufficiency.<br />

4 Ricci S. Ultrasound Observation <strong>of</strong> the Sciatic Nerve and Its Branches at the Popliteal Fossa: Always Visible, Never Seen. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg<br />

2005;30:659-663<br />

5 Tellings SS, Ceulen PPM, Sommer A. Surgery and endovenous techniques for the treatment <strong>of</strong> small saphenous varicose veins: a review <strong>of</strong> the literature,<br />

<strong>Phlebology</strong> 2011;26:179-184<br />

6 Myers K. Surgery for small saphenous reflux is obsolete! Venous Digest 2005, modified from the ANZ J <strong>Phlebology</strong><br />

16

Prevention <strong>of</strong> venous<br />

thromboembolism:<br />

the Seventh ACCP Conference<br />

on Antithrombotic and<br />

Thrombolytic Therapy<br />

Author: Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al.<br />

Chest. 2004;126(suppl):338S-400S.<br />

Contributing Editor/Reviewer: Amjad T. AlMahameed, MD, MPH<br />

Associate Editor: Stephanie Dentoni, MD<br />

17

COMMENTARY<br />

The 9th <strong>American</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chest Physicians (ACCP)<br />

guidelines for prevention <strong>of</strong> venous thromboembolic<br />

disease (VTE) noted a major shift in the methodology<br />

used by the authors. They discarded surrogate endpoints<br />

(asymptomatic venographically-evident VTE) and elevated<br />

death and symptomatic VTE as the only reliable outcome<br />

measures. They also advocate incorporating bleeding risk<br />

alongside thrombotic risk assessment when deciding on<br />

pharmacoprophylaxis. Lastly, they recommend against the<br />

application <strong>of</strong> performance measures in medical patients<br />

that promote universal VTE prophylaxis regardless <strong>of</strong> risk.<br />

In the present viewpoint, I also review the events that<br />

led to mandating performance measures that, despite<br />

best intensions, may have promoted unforeseen risks.<br />

While I disagree with discarding a large body <strong>of</strong> evidence<br />

that links asymptomatic VTE to clinically relevant major<br />

adverse events, including death, I agree with the final<br />

(VTE) remains...<br />

the most<br />

common cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> preventable<br />

hospital death,<br />

and a primary<br />

contributor<br />

to 10% <strong>of</strong> all<br />

hospital deaths.<br />

recommendations to use thromboprophylaxis based on<br />

individualized risk-benefit assessment.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) remains a major cause <strong>of</strong> morbidity and mortality, the most common cause <strong>of</strong><br />

preventable hospital death, and a primary contributor to 10% <strong>of</strong> all hospital deaths. 1 , 2 Overall, VTE may affect 10-40%<br />

<strong>of</strong> “at-risk” hospitalized patients who do not receive proper thromboprophylaxis. 1,3 In fact, the thrombotic risk extends<br />

well beyond discharge from the index hospitalization in both surgical and non-surgical patients. In one population-based<br />

retrospective study, the average annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence <strong>of</strong> in-hospital VTE was more than 100 times<br />

greater than the incidence among community residents. 4<br />

1 Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention <strong>of</strong> venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic<br />

Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(suppl):338S-400S.<br />

2 Sandler DA, Martin JF. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med.<br />

1989;82(4):203–205.<br />

3 Hillen HF. Thrombosis in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(suppl 3):273-276.<br />

4 Heit JA, Melton LJ 3rd, Lohse CM. Incidence <strong>of</strong> venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients vs community residents. <strong>May</strong>o Clin Proc 2001;76:1102

How Did Thromboprophylaxis Become “Universal”?<br />

Several factors have led to adopting near universal thromboprophylaxis to hospitalized patients. These include the<br />

markedly increased VTE prevalence in this at-risk group, serious adverse consequences <strong>of</strong> VTE (death, pulmonary<br />

embolism [PE], chronic post-thrombotic pulmonary hypertension and post-phlebetic syndrome) and the proven efficacy,<br />

safety and cost-effectiveness <strong>of</strong> thromboprophylaxis. Other important factors that fostered the generalization <strong>of</strong> these<br />

universal thromboprophylaxis recommendations include: 1) Absence <strong>of</strong> discrete prodromal phase: most VTEs noted in<br />

thromboprophylactic trials are subclinical (asymptomatic). Even in patients that were eventually labeled as having had<br />

symptomatic VTE, their initial signs and symptoms are common in this population and non-specific. 2) Absence <strong>of</strong> reliable<br />

screening test: venography, the gold standard used in thromboprophylactic trials, is highly accurate. Nonetheless, it is an<br />

impractical, invasive, expensive, and potentially thrombogenic test. Venous duplex ultrasonography is expensive and not<br />

all that sensitive in a large portion <strong>of</strong> hospitalized patients.<br />

The past 10 years witnessed the introduction <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> VTE prevention initiatives. Among these, several stand out<br />

as landmark documents: In 2006, The Joint Commission/National Quality Forum 17 performance measures (which was<br />

revised in 2008 to include 6 additional measures) were published. 5 , 6 In 2008, The ACCP evidence-based clinical practice<br />

guidelines on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy included an expanded section on VTE prevention. It strongly<br />

emphasized that hospitals should consider developing strategies to consistently identify hospitalized patients at risk for<br />

VTE and actively seek to prevent VTE occurrence and recurrence. 7 Soon thereafter, the US Surgeon General released a<br />

“Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism” that urged a coordinated, multifaceted plan<br />

to reduce the VTE incidence nationwide. 8 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) contributed to the<br />

“Call to Action” with the release <strong>of</strong> two new guides: one for patients and another for health care providers, counseling<br />

both to participate in disseminating VTE prevention recommendations. 9<br />

These successive initiatives, along with well-publicized campaigns that followed, led to the rapid dissemination <strong>of</strong> these<br />

recommendations. Quickly, hospital administration became engaged and decided to support VTE prevention programs.<br />

As front-line clinicians embraced the recommendations, VTE prophylaxis practices became “standard <strong>of</strong> care” and<br />

5 http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Prevention_and_Care_<strong>of</strong>_Venous_<br />

Thromboembolism__Policy,_Preferred_Practices,_and_Initial_Performance_Measures.aspx<br />

6 http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2008/10/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Prevention_and_Care_<strong>of</strong>_Venous_<br />

Thromboembolism__Additional_Performance_Measures.aspx<br />

7 Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al., <strong>American</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chest Physicians. Prevention <strong>of</strong> venous thromboembolism: <strong>American</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chest<br />

Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008; 133:381S–453S.<br />

8 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/deepvein/index.html<br />

9 http://www.ahrq.gov/pr<strong>of</strong>essionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/vtguide/vtguide.pdf<br />

19

“clinical practice pathways”; while “computerized electronic alerts” as well as “algorithm-based” strategies were widely<br />

developed to ensure continued compliance.<br />

Another important, yet unspoken, factor that may have augmented this response was the federal government’s Centers for Medicare<br />

and Medicaid Services (CMS) threat to deny reimbursement for hospital-acquired VTE as it considered it a “preventable medical<br />

error”. Compliance with these guidelines (which the CMS presumed would eliminate such “preventable medical errors”) was therefore<br />

viewed as an important means towards improving patients’ outcomes, decreasing “preventable medical errors” and avoiding potential<br />

penalties. Such eagerness for “perfect compliance” was fostered and patrolled by hospital administrators and quality control medical<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers. One wonders if this could have led to a speedy generalization <strong>of</strong> the recommendations to include some patients that may<br />

have been at extraordinarily low risk for VTE or unusually high risk for bleeding complications. Therefore, the “Sentinel Event Alert”<br />

released by The Joint Commission entitled “Preventing Errors Relating to Commonly Used Anticoagulants”) in late 2008 came as no<br />

surprise to us.<br />

Reconciling the Newly Adopted ACCP Outcome Measures with<br />

Daily Practice<br />

The ACCP methodologists attempted to weigh the evidence for and against thromboprophylaxis using prevention <strong>of</strong> fatal<br />

PE and “symptomatic” VTE (which they presumed to be synonymous with “clinically relevant” VTE) as the primary goal <strong>of</strong><br />

this treatment, while at the same time integrating serious bleeding complications into the final outcome. Interestingly,<br />

in order to justify this “new” endpoint, they considered asymptomatic, venographically-confirmed VTE to be clinically<br />

irrelevant and, therefore, could be discounted from the evidence. Needless to say, the arguments against using the<br />

disputed terms symptomatic/clinically relevant and asymptomatic/clinically irrelevant interchangeably are obvious to<br />

every practicing clinician and well summarized in the paper by Bounameaux and Agnelli.<br />

In my opinion, the advantages <strong>of</strong> advancing the discussion about VTE prophylaxis practices as universal recommendation<br />

are many. It certainly highlights the importance <strong>of</strong> thoughtfully considering the risks and benefits <strong>of</strong> pharmacoprophylaxis<br />

in every hospitalized patient and removing the automation from the process. The limitations inherent in the historical<br />

studies used by the authors as basis for their recommendation (whether supporting “symptomatic” or disputing<br />

“asymptomatic” events) call for expanding funding for larger, well conducted prospective studies that address these issues<br />

directly. Further research focused on improving clinically-accepted means <strong>of</strong> enhanced pr<strong>of</strong>iling <strong>of</strong> thrombotic as well as<br />

bleeding risks in pr<strong>of</strong>iling <strong>of</strong> hospitalized patients are also needed.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Clinical guidelines are meant to raise awareness and highlight the public health impact as well as establish a framework<br />

for approaching a specific clinical problem. Clinical judgment and individualized risk assessment remain the most critical<br />

component <strong>of</strong> decision making, and this is particularly true when it comes to VTE prophylaxis.