FINANCE FOR ALL ? - Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

FINANCE FOR ALL ? - Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

FINANCE FOR ALL ? - Frankfurt School of Finance & Management

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

No.8_1/2012<br />

<strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Finance</strong> & <strong>Management</strong><br />

Bankakademie HfB<br />

finance <strong>FOR</strong> all ?<br />

zur zukunft<br />

der mikr<strong>of</strong>inanz

EdITORIAl<br />

Wohlstand kann nicht importiert werden.<br />

Die klassische, zum größten Teil auf öffentlichen Geldern basierende Entwicklungshilfe der<br />

vergangenen Jahrzehnte ist gescheitert. Oft erreicht das Geld nicht die Menschen, für die<br />

es eigentlich bestimmt ist. Nicht-Regierungs-Organisationen und Regierungen verfolgen<br />

deshalb neue Wege zur Armutsbekämpfung. Sie diskutieren, ob Selbstlosigkeit per se moralisch<br />

gut und Egoismus immer verwerflich ist. Die traditionelle, ethnozentristische Entwicklungshilfe<br />

hat die Eigeninitiative in Entwicklungsländern gelähmt, Reformen verzögert<br />

und den Aufbau funktionierender Institutionen verhindert. Es liegt auf der Hand, dass man<br />

Menschen an Entscheidungen, die sie betreffen, aktiv beteiligen muss. Nur so werden sie<br />

die Fähigkeiten erwerben, um ihr Leben selbstständig und eigenverantwortlich in die Hand<br />

zu nehmen. Nur so wirkt eine kluge – nachhaltige – Entwicklungsarbeit, die sich auf lange<br />

Sicht selbst überflüssig macht.<br />

Laut des uNICEF-Kinderberichts aus dem Jahr 2009 sterben weltweit jeden Tag 22.000 Kinder aufgrund von<br />

Armut. Im Jahr 2011 hat der IFAD (International Fund for Agricultuaral Development) erhoben, dass 1,4 Milliarden<br />

Menschen auf der Welt täglich nur 1,25 Dollar oder noch weniger Geld zum Leben haben. Laut eines<br />

Weltbank-Berichts aus dem Jahr 2010 haben 81 Prozent aller Erwachsenen in Industrieländern Zugang zum<br />

Bank- und Finanzwesen. Hier verfügt jeder Erwachsene durchschnittlich über 3,2 Konten. In den Entwicklungsländern<br />

hingegen kommen auf jeden Erwachsenen nur 0,9 Konten und nur 28 Prozent haben Zugang zum<br />

Bank- und Finanzwesen – so der IFAD in seinem Bericht. Ich bin überzeugt, Menschen können ihre Lebensbedingungen<br />

verbessern, wenn sie Zugang zum Finanzsektor haben.<br />

Seit Friedensnobelpreisträger Muhammad yunus vor dreißig Jahren mit seiner Grameen-Bank in Bangladesch<br />

den Grundstein für Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanz legte, wurde die Idee des Kleinstkredits immer weiterentwickelt. Menschen in<br />

Entwicklungs- und Schwellenländern ohne Zugang zum Bank- und Finanzwesen stehen damit vielerorts umfangreiche<br />

Spar-, Versicherungs- und Kreditangebote zur Verfügung. Die meisten Kunden im Mikrobereich sind<br />

selbstständige unternehmer. Berater der Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitutionen begleiten sie dabei, ihr Geschäft erfolgreich<br />

zu entwickeln. Mit der Vergabe von Mikrokrediten in Höhe von 50 oder 100 Dollar – um etwa einen Gaskocher<br />

für eine Garküche anzuschaffen – ergeben sich Perspektiven aus der Armut.<br />

Wenn es heute darum geht, die wirtschaftliche und soziale Entwicklung in Entwicklungs- und Schwellenländern<br />

zu fördern, werden Mittel privater Investoren immer wichtiger. Sie ermöglichen eine neue Ära in der Entwicklungsfinanzierung.<br />

und es lohnt sich für sie, in diesen Ländern zu investieren. Sie müssen ihre ethischen Ziele<br />

nicht mit einer niedrigeren Rendite bezahlen. Mit etwa 100 Beratern und Experten engagiert sich die <strong>Frankfurt</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Finance</strong> & <strong>Management</strong> in der Entwicklungsfinanzierung. unsere Asset <strong>Management</strong>-Tochter Connective<br />

Capital verwaltet Fonds, die in Entwicklungs- und Schwellenländern investiert sind. Innovative Ansätze<br />

für die Entwicklungsarbeit entstehen an unserem Forschungscenter für Development <strong>Finance</strong>. In der Vertiefung<br />

Development <strong>Finance</strong> im Master <strong>of</strong> <strong>Finance</strong> bereiten sich junge Talente aus der ganzen Welt auf eine Zukunft<br />

in der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit vor. Sie haben exzellente Perspektiven, denn rund um den Globus werden<br />

Fach- und Führungskräfte in diesem Bereich gesucht.<br />

Wohlstand kann nicht importiert oder verschenkt werden. Er lässt sich nur vor Ort schaffen. Das ist das Leitmotiv<br />

unserer Aktivitäten. Es lohnt sich, darüber nachzudenken, unter welchen Bedingungen das am besten gelingt.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr. udo Steffens<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr. Udo Steffens ist Präsident der <strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Finance</strong> & <strong>Management</strong>. Im Rahmen der kirchlichen Entwicklungszusammenarbeit arbeitete er von<br />

1989 bis 1992 in Togo und Kamerun. Unter anderem managte er Neupositionierung und Restrukturierung eines Buchhandels-, Verlags- und Druckereiunternehmens<br />

in Togo. 1992 kam er zur <strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong>, seit 1996 ist er der Präsident der Business <strong>School</strong>. Er hat den Bereich International Advisory Services mit begründet und<br />

prägt ihn bis heute wesentlich. www.fs.de/steffens<br />

2 EDITORIAL

You can’t import prosperity.<br />

Traditional development aid as it has been practised over the past few decades – i.e. based primarily on public<br />

money – has failed. All too <strong>of</strong>ten the money doesn’t reach the people it is intended for. Hence NGOs and<br />

governments alike are seeking new ways to fight poverty. Indeed, they are debating whether altruism is always<br />

morally good per se and egotism always reprehensible. In developing countries the traditional, ethnocentric<br />

approach to development aid has paralysed initiative, delayed reforms and hindered the creation <strong>of</strong> functional<br />

institutions. It is clear that people must be actively involved in decisions that will affect them. Only thus do they<br />

acquire the skills they need to take autonomous, self-reliant control <strong>of</strong> their own lives. Only thus does an intelligent<br />

approach to development take lasting effect – by making itself superfluous in the long run.<br />

The uNICEF State <strong>of</strong> the World’s Children Report 2009 reveals that every day, 22,000 children around the<br />

world die <strong>of</strong> poverty-related causes. In 2011, a survey by the International Fund for Agricultural Development<br />

(IFAD) showed that 1.4 billion people around the world live on a daily income <strong>of</strong> 1.25 uS dollars or less. According<br />

to a 2010 report by the World Bank, 81% <strong>of</strong> all adults in the industrialised world have access to banking<br />

and financial services – in fact, each adult has 3.2 bank accounts on average. In the IFAD report we find that<br />

in the developing world, there are only 0.9 bank accounts per adult, and less than 28% <strong>of</strong> them have access<br />

to banking or financial services. I am convinced that given proper access to the financial sector, people can<br />

improve their quality <strong>of</strong> life.<br />

The microcredit concept has steadily evolved ever since Nobel peace prize winner Muhammad yunus laid the<br />

foundations <strong>of</strong> the micr<strong>of</strong>inance industry by setting up Grameen Bank in Bangladesh 30 years ago. In many<br />

places, comprehensive savings, insurance and credit plans are now available to people in developing and<br />

emerging markets who would otherwise have no access to banking or financial services. Most clients in the<br />

micr<strong>of</strong>inance sector are self-employed businesspeople: advisers from micr<strong>of</strong>inance institutions (MFIs) also help<br />

them build their businesses. A microloan <strong>of</strong> just 50 or 100 uS dollars – enough to buy a gas cooker for a food<br />

stall, for example – gives a borrower some prospect <strong>of</strong> escape from poverty.<br />

Today, as we seek for ways to stimulate economic and social development in developing and emerging markets,<br />

funding from private investors is becoming ever more important, heralding a new era in development<br />

finance. And private investors are finding it makes good sense to invest in these countries – pursuing ethical<br />

objectives does not mean accepting lower returns.<br />

With a team <strong>of</strong> some 100 consultants and experts, <strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Finance</strong> & <strong>Management</strong> is heavily committed<br />

to development finance. Our asset management subsidiary Connective Capital manages funds that<br />

are invested in developing and emerging economies. Our Development <strong>Finance</strong> research centre is working on<br />

promising new initiatives. And talented young people from all around the world studying for their Master <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Finance</strong> degrees are opting to specialise in Development <strong>Finance</strong>, in preparation for a future in international<br />

development cooperation. Their prospects are excellent – the global demand for pr<strong>of</strong>essionals and executives<br />

specialising in this area has never been higher.<br />

Prosperity is not something you can import or donate. It can only be created locally, on the spot. Our work<br />

is based on this premise. As you read this issue, I invite you to ponder: in what conditions can this best be<br />

achieved?<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr. udo Steffens<br />

© JAN STRADTMANN<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Dr. Udo Steffens is President <strong>of</strong> <strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Finance</strong> & <strong>Management</strong>. Between 1989 and 1992 he worked in Togo and Cameroon as part <strong>of</strong><br />

a church-sponsored development cooperation team. Among other projects he managed the repositioning and restructuring <strong>of</strong> a bookselling, publishing<br />

and printing business in Togo. he joined <strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> in 1992 and was appointed President in 1996. he is a c<strong>of</strong>ounder <strong>of</strong> the International Advisory Services<br />

unit and continues to play a key role in its development. www.fs.de/steffens<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

3

SONNEMANN No. 8<br />

<strong>FINANCE</strong><br />

<strong>FOR</strong> <strong>ALL</strong>?<br />

zur zukunft<br />

der MIKROfinanz<br />

PERISKOP<br />

PERISCOPE<br />

6_ Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung<br />

Die sechs größten globalen Geldgeber.<br />

MICRO<strong>FINANCE</strong><br />

The world's six largest investors.<br />

FOKUS<br />

FOCUS<br />

8_ Kredit verspielt?<br />

Die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanz-Bewegung<br />

versprach, das Leben der Armen zu<br />

verbessern und hohe Gewinne für<br />

die Anbieter. Sie versprach zu viel.<br />

Warum die Idee trotzdem richtig ist.<br />

INTERVIEW<br />

INTERVIEW<br />

30_ „Ich habe selber viele<br />

Fehler gemacht.“<br />

Vijay Mahajan, Gründer der indischen<br />

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitution BASIX, über die<br />

Krise in Andhra Pradesh.<br />

“I made many<br />

mistakes myself.”<br />

Vijay Mahajan, founder <strong>of</strong> Indian<br />

micr<strong>of</strong>inance institution BASIX,<br />

talks about the industry crisis in<br />

Andhra Pradesh.<br />

KALEIDOSKOP<br />

KALEIDOSCOPE<br />

Credit gambled away?<br />

The micr<strong>of</strong>inance movement<br />

promised to alleviate poverty while<br />

generating high returns for<br />

investors. It promised too much.<br />

Here's why it's still a good idea.<br />

38_ Komplexes Wirtschaften<br />

Das Portfolio von Saiful und Nargis.<br />

A complex business<br />

The financial portfolio <strong>of</strong><br />

Saiful and Nargis.<br />

Carolyn Braun ist Partnerin des Journalistenbüros Wortlaut<br />

& Söhne. Sie schreibt über Wirtschafts- und Finanzthemen,<br />

vor allem für die ZEIT und brand eins. Für die aktuelle Sonnemann-Ausgabe<br />

reiste sie nach Indien, in die Provinz Andhra<br />

Pradesch, um dort mehr über die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzkrise auf dem<br />

Subkontinent zu erfahren.<br />

Carolyn Braun is a partner at Wortlaut & Söhne, a firm <strong>of</strong> journalists.<br />

She writes on business and financial topics, mainly<br />

for Die ZEIT and brand eins. For this issue <strong>of</strong> Sonnemann she<br />

travelled to the Indian province <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh to find out<br />

more about the subcontinent’s micr<strong>of</strong>inance crisis.<br />

4 INHALT

TANGENTEN<br />

TANGENTS<br />

CAMPUS<br />

CAMPUS<br />

Marcus Müller arbeitet als freier Journalist in Berlin, er<br />

schreibt über Themen aus Politik und Wirtschaft. Für diesen<br />

Sonnemann traf er in Berlin, Bochum und Bielefeld Menschen,<br />

die sich mit einem Mikrokredit selbstständig machten.<br />

Interessant war für ihn, dass dadurch auch angeblich Kreditunwürdige<br />

eine Chance für ihre Geschäftsidee haben.<br />

Marcus Müller works as a freelance journalist in Berlin, specialising<br />

in politics and economics. For this issue <strong>of</strong> Sonnemann<br />

he met up with people in Berlin, Bochum and Bielefeld<br />

who have taken out microloans to start their own businesses<br />

in Germany. He made an interesting discovery: even people<br />

branded as credit risks can use micr<strong>of</strong>inance to make their<br />

business ideas work.<br />

40_ PRINZIP DORFBANK<br />

Von Banken verschmäht: Immer mehr<br />

Gründer leihen sich Geld beim<br />

„Mikrokreditfonds Deutschland“.<br />

The village Bank Principle<br />

Spurned by banks, more and more<br />

startups are borrowing money<br />

from Mikrokreditfonds Deutschland.<br />

50_ Crowdfunding<br />

Sonnemann-Autoren suchen auf den<br />

Webseiten der Schwarmfinanzierer<br />

nach Menschen, denen sie ihr Geld<br />

anvertrauen würden.<br />

CROWDFUNDING<br />

Sonnemann writers comb<br />

crowdfunding websites to find<br />

borrowers they can trust with<br />

their cash.<br />

VISITE<br />

VISIT<br />

66_ INSIGHT<br />

Fatma Dirkes über die Entwicklung<br />

funktionierender Finanzsysteme.<br />

INSIGHT<br />

Fatma Dirkes on developing fully<br />

functional financial systems.<br />

71_ agenda<br />

Ernteeinsatz: Wie türkische Banken<br />

türkische Bauern beackern.<br />

Agenda<br />

Harvest time: how Turkish banks<br />

are cultivating Turkish farmers.<br />

77_ Sabine Spohn über<br />

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung im Pazifik-Raum.<br />

Sabine Spohn on micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

in the Pacific region.<br />

78_ STUDENTEN<br />

Schärfer regulieren? Studenten der<br />

<strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> kommentieren.<br />

Bill Maslen ist Geschäftsführer von The Word Gym in den<br />

schottischen Perthshire Highlands. Das Übersetzungs- und<br />

Textbüro wurde 1990 gegründet und arbeitet für renommierte<br />

Kunden im deutschsprachigen Raum, auch für die <strong>Frankfurt</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong>. Ein besonderes Faible hat er für die Sonnemann-<br />

Texte, da sie immer wieder neue Denkanstöße liefern.<br />

Bill Maslen is Managing Director <strong>of</strong> The Word Gym Ltd.,<br />

based in the Perthshire Highlands <strong>of</strong> Scotland. The Word<br />

Gym was set up in 1990, and specialises in advertising and<br />

marketing copy. Bill regularly writes and translates copy for<br />

<strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong> and a number <strong>of</strong> other prestigious clients in<br />

German-speaking countries, but particularly enjoys working<br />

on the thought-provoking topics in each issue <strong>of</strong> Sonnemann.<br />

56_ generation hörsaal<br />

Warum Studienkredite jordanische<br />

Jugendliche nicht vor Arbeitslosigkeit<br />

bewahren.<br />

lecture-theatre Generation<br />

Why student loans don't<br />

protect young people in<br />

Jordan from unemployment.<br />

STUDENTS<br />

Tougher regulation? <strong>Frankfurt</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

students express their views.<br />

80_ ALUMNI<br />

Manfred Heid –<br />

Indiana Jones aus der Eifel.<br />

ALUMNI<br />

Manfred Heid –<br />

Indiana Jones lives in the Eifel!<br />

81_ JOBS<br />

Barbara Drexler: Career Compass.<br />

.<br />

82_ veranstaltungen/kalender<br />

EVENTS/DIARY<br />

49_ IMPRESSUM<br />

MASTHEAD<br />

CONTENTS 5

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung<br />

70 Milliarden Dollar schwer ist die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzbranche. 13 Milliarden davon legten<br />

ausländische Investoren im Jahr 2010 in Entwicklungs- und Schwellenländern an, mehr als<br />

vier Mal so viel wie vier Jahre zuvor. Wir stellen die sechs größten globalen Investoren vor.<br />

Responsability AG<br />

Oikocredit<br />

Dexia Micro-Credit Fund<br />

Mit dem Global Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Fund, dem<br />

SICAV Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Leader Fund und dem<br />

SICAV Micr<strong>of</strong>inanz Fonds verwaltet die<br />

Schweizer responsAbility AG gleich drei<br />

der zehn größten Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzfonds. 647<br />

Millionen Dollar verwalten die drei Fonds<br />

(2006: 113 Millionen). Das Fondsvermögen<br />

des 2003 gegründeten Vermögensverwalters<br />

ist in 365 Unternehmen und 68 Ländern<br />

angelegt.<br />

—<br />

Swiss social investment company<br />

responsAbility AG manages three <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world’s 10 largest micr<strong>of</strong>inance funds:<br />

the Global Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Fund, SICAV<br />

Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Leader Fund and SICAV Micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

Fund. Between them the three<br />

funds manage 647 million dollars (2006:<br />

113 million). Founded in 2003, the asset<br />

management company’s financial assets<br />

are invested in 365 companies and 68<br />

countries.<br />

„In Menschen investieren“, so wirbt die internationale<br />

Entwicklungsgenossenschaft,<br />

die Mitte der siebziger Jahre auf Initiative<br />

des Ökumenischen Rates der Kirchen gegründet<br />

wurde, auf ihrer Webseite. Für<br />

200 Euro gibt es einen Genossenschaftsanteil,<br />

dafür verspricht Oikocredit „einen<br />

finanziellen und sozialen Gewinn“. Die Organisation<br />

mit Sitz im niederländischen<br />

Amersfoort ist in Asien, Afrika und Osteuropa<br />

unterwegs. Über 600 Millionen Euro<br />

hat Oikocredit eingeworben, 472 Millionen<br />

Euro sind investiert (2006: 200 Millionen).<br />

—<br />

“Investing in People” is the slogan that<br />

appears on the website <strong>of</strong> international<br />

cooperative society Oikocredit, founded in<br />

the 'Seventies at the behest <strong>of</strong> the World<br />

Council <strong>of</strong> Churches. For 200 euros you<br />

can buy a share in the cooperative; in return,<br />

Oikocredit promises a “social and financial<br />

return”. Based in Amersfoort in the<br />

Netherlands, the organisation is active in<br />

Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. Oikocredit<br />

has raised more than 600 million euros,<br />

472 million <strong>of</strong> which have been invested.<br />

In 2006 the figure was shy <strong>of</strong> 200 million.<br />

Der im September 1998 aufgelegte Fonds<br />

ist der älteste in Europa für Privatanleger.<br />

Verwaltet vom Genfer Vermögensverwalter<br />

BlueOrchard, der mit seiner Anlagestrategie<br />

eine Zielrendite von drei bis vier<br />

Prozent anstrebt, hat das Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanz-<br />

Portfolio des Fonds aktuell ein Volumen<br />

von 438 Millionen Dollar (2006: 108 Millionen<br />

Dollar). Das Geld haben die Verwalter<br />

in über 100 Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitutionen<br />

(MFIs) investiert.<br />

—<br />

Set up in September 1998, this is the oldest<br />

fund in Europe catering for private<br />

investors. Managed by BlueOrchard, an<br />

asset management company in Geneva,<br />

with an investment strategy aiming for<br />

a 3-4% return, the fund’s micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

portfolio totalled 438 million dollars as<br />

at year-end 2011 (2006: 108 million dollars).<br />

The fund managers have invested the<br />

money in more than 100 micr<strong>of</strong>inance institutions<br />

(MFIs).<br />

No. None whatsoever.<br />

And I don’t have to give you any security?<br />

6 PERISKOP

MICRO<strong>FINANCE</strong><br />

The micr<strong>of</strong>inance sector is currently worth 70 billion dollars. In 2010, 13 billion dollars were<br />

invested in developing and emerging economies by overseas institutions – more than four<br />

times as much as four years earlier. Here we introduce the six largest global investors.<br />

SNS Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Fund<br />

MEF<br />

ASN-Novib Fund<br />

Die zwei in den Jahren 2007 und 2008<br />

aufgelegten Fonds kommen zusammen<br />

auf ein Vermögen von 388 Millionen Dollar.<br />

348 Millionen davon haben die Fondsmanager<br />

der niederländischen SNS Asset<br />

<strong>Management</strong> weltweit in 149 MFIs investiert,<br />

sowohl als Eigen- als auch als Fremdkapital.<br />

Beide Fonds richten sich ausschließlich<br />

an holländische Investoren.<br />

—<br />

The two funds, set up in 2007 and 2008<br />

respectively, represent combined assets <strong>of</strong><br />

388 million dollars, 348 million <strong>of</strong> which<br />

have been invested by the fund managers<br />

<strong>of</strong> Netherlands-based SNS Asset <strong>Management</strong><br />

in 149 MFIs worldwide, in the form<br />

<strong>of</strong> equity and loan capital. Both funds are<br />

intended exclusively for Dutch investors.<br />

Anfang 2009 hat die KfW Entwicklungsbank<br />

zusammen mit der Bundesregierung<br />

und der International <strong>Finance</strong> Corporation<br />

(IFC) den neuen globalen Refinanzierungspool<br />

Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Enhancement Facility<br />

(MEF) gegründet. Ziel des Fonds ist<br />

es, die Zurückhaltung privater Investoren<br />

und den geringeren Zufluss von Spareinlagen<br />

infolge der Finanzkrise auszugleichen.<br />

Bislang hat die MEF knapp 170 Millionen<br />

Dollar weltweit in MFIs investiert und erreicht<br />

damit laut eigenen Angaben 60 Millionen<br />

Kleinstunternehmer.<br />

—<br />

In partnership with the German Federal<br />

Government and International <strong>Finance</strong><br />

Corporation (IFC), KfW development bank<br />

set up new global funding pool Micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

Enhancement Facility (MEF) in early<br />

2009. The fund aims to make up for the<br />

financial crisis-induced reticence <strong>of</strong> private<br />

investors and reduced inflow <strong>of</strong> savings.<br />

To date MEF has invested just under 170<br />

million dollars in MFIs around the world,<br />

funding that according to its own figures<br />

supports 60 million micro-businesses.<br />

Den ältesten Fonds für Privatanleger der<br />

Niederlande hat die ASN Bank gemeinsam<br />

mit Oxfam im Jahr 1999 aufgelegt.<br />

Das Fondsvermögen in Höhe von 178 Millionen<br />

Euro (2006: 46 Millionen Euro) verwaltet<br />

die Firma Triple Jump, die davon<br />

120 Millionen über 68 MFIs vor allem in<br />

Mikroentrepreneure in Entwicklungs- und<br />

Schwellenländern investiert hat.<br />

—<br />

The Netherlands’ oldest fund for private investors<br />

was set up jointly by ASN Bank and<br />

Oxfam in 1999. The fund’s assets amount<br />

to 178 million euros (2006: 46 million euros)<br />

and are managed by Triple Jump, an<br />

asset manager which has invested 120 million<br />

euros primarily in microbusinesses in<br />

developing and emerging markets worldwide<br />

via 68 MFIs.<br />

Quelle /Source: CGAP – www.cgap.org<br />

Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Information Exchange – www.mixmarket.org<br />

So I have to take him back home with me again?<br />

PERISCOPE<br />

7

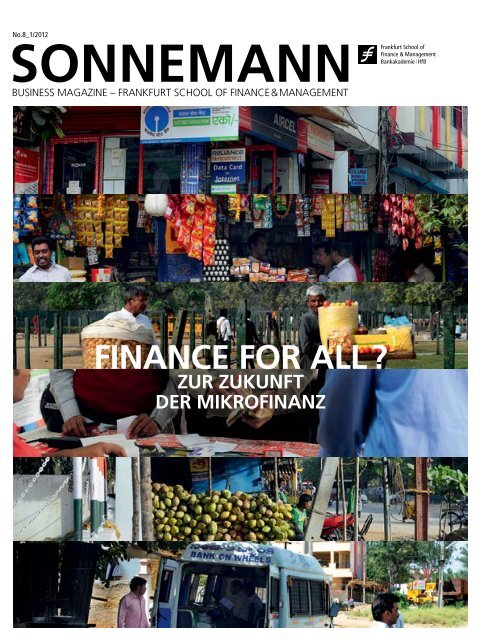

Das indische Dorf Nagarkurnool hat keine Bank. Aber einen Bus mit einem vergitterten<br />

Das indische Dorf Nagarkurnool hat keine Bank. Aber einen Bus mit einem vergitterten<br />

Schalter, der jeden Dienstag und Freitag im Dorf hält- die Bank on wheels.<br />

Schalter, der jeden Dienstag und Freitag im Dorf hält – die Bank on wheels.<br />

The Indian village <strong>of</strong> Nagarkurnool doesn’t have a bank – but it does have a bus with barred<br />

The Indian village <strong>of</strong> Nagarkurnool doesn’t have a bank – but it does have a bus with barred<br />

windows that stops in the village every Tuesday and Friday: the “Bank on Wheels”.<br />

windows that stops in the village every Tuesday and Friday: the “Bank on Wheels”.<br />

© JAN stradtmann

Kredit<br />

verspielt?<br />

20 MIN<br />

Die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanz-Bewegung versprach, das<br />

Leben der Armen zu verbessern. Und<br />

hohe Gewinne für die Anbieter.<br />

Im Boom-Markt Indien ist das gründlich<br />

schief gelaufen. Warum die Idee rotzdem<br />

richtig ist.<br />

E<br />

s gehört sich eigentlich, diese Geschichte mit jemandem<br />

wie Janaki Ramulu zu beginnen. An diesem<br />

Morgen im November ist er früh aufgestanden,<br />

hat gemeinsam mit Anjanaiah, seinem Nachbarn<br />

und Freund aus Kindertagen, das M<strong>of</strong>a bestiegen<br />

und ist die 40 Kilometer aus seinem Heimatdorf Tirmalapur<br />

nach Nagarkurnool, im Bezirk Mahabubnagar des indischen Bundesstaats<br />

Andhra Pradesh, gefahren. Zur „Bank on Wheels“, die<br />

dort wie jeden Dienstag und Freitag Station macht. Auf den weißen<br />

Plastikstühlen am Straßenrand warten bereits 14 Landarbeiter<br />

darauf, über ihren Kreditantrag sprechen zu dürfen. Vor ihren<br />

Füßen schnüffelt ein Ferkel im Abfall herum. Ramulu hat den Kreditantrag<br />

der KBS Bank bereits ausgefüllt, Anjanaiah bürgt für ihn:<br />

Zahlt der 31-jährige Kleinstbauer nicht pünktlich, muss der Freund<br />

für seine Schulden einstehen. Nachdem ihn ein Bankangestellter<br />

noch einmal über seine Rechte und Pflichten aufgeklärt hat, ist<br />

es endlich so weit: Ramulu darf sein Konto eröffnen. Ein breites<br />

Lächeln erhellt sein dunkles Gesicht, als ihm der Schalterbeamte<br />

20.000 Rupien durch das vergitterte Fenster des Mercedes-Busses<br />

reicht, das sind etwa 285 Euro. Von dem Geld will Ramulu Saatgut<br />

kaufen, für Tomaten und Okraschoten: „Die tragen das ganze Jahr<br />

über Früchte.“ Mit dem Ertrag will er seine Familie ernähren. Und<br />

natürlich seinen Kredit in monatlichen Raten im Laufe des nächsten<br />

Jahres zurückzahlen.<br />

Die meisten Geschichten über die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzbranche fangen<br />

mit Menschen wie Janaki Ramulu an. Sie leben irgendwo in einem<br />

Schwellenland und sind sehr arm, sie beantragen einen Kredit,<br />

Credit gambled<br />

away?<br />

The micr<strong>of</strong>inance movement promised to<br />

improve the lives <strong>of</strong> people living in poverty.<br />

And yield high returns for investors. In India’s<br />

booming market, it all went horribly wrong.<br />

Here’s why the idea is still a good one.<br />

I<br />

n actual fact, it’s quite right to start this story with<br />

someone like Janaki Ramulu. Up bright and early<br />

this November morning, he climbs onto his moped<br />

accompanied by Anjanaiah – his friend and neighbour<br />

since childhood – and drives 25 miles (40 km)<br />

from his home village <strong>of</strong> Tirmalapur to Nagarkurnool in the Mahabubnagar<br />

district <strong>of</strong> the Indian federal state <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh.<br />

Their destination: the “Bank on Wheels” that stops there every<br />

Tuesday and Friday. 14 farm workers are already seated on white<br />

plastic chairs at the edge <strong>of</strong> the road, waiting to discuss their loan<br />

applications. A piglet roots through the litter around their feet.<br />

Ramulu has already filled out the application form for a KBS Bank<br />

loan, with Anjanaiah as his guarantor: if the smallholder doesn’t<br />

pay up on time, his friend will have to settle his debt instead.<br />

The “Bank” arrives, and a bank employee – yet again – explains<br />

his rights and obligations. All is well: Ramulu is allowed to open<br />

an account. A broad smile lights up his dark face as the bank<br />

clerk passes him 20,000 rupees through the barred window <strong>of</strong><br />

the Mercedes bus. That’s about 285 euros! Ramulu is hoping to<br />

buy seeds with the money, so he can plant tomatoes and okra:<br />

“they fruit all year round.” With the income, he’ll be able to feed<br />

his family. And <strong>of</strong> course pay back his loan in monthly instalments<br />

over the next year.<br />

Most stories about the micr<strong>of</strong>inance industry start with people<br />

like Janaki Ramulu. They live somewhere in a developing coun-<br />

FOCUS<br />

9

10 FOKUS

20.000 Rupien für Okraschoten und Tomaten<br />

20,000 RUPEES <strong>FOR</strong> OKRA AND TOMATOES<br />

Ohne die Bürgschaft von Anjanaiah (Foto links, r.) hätte Janaki Ramulu (l.) seinen Kredit<br />

nicht bekommen. Anjanaiah hat s<strong>of</strong>ort zugestimmt, sagt er, schließlich kennt er Janaki von<br />

Kindesbeinen an und ist sich sicher, dass er niemals für ihn einspringen muss. Dass er aber im<br />

Ernstfall haftet, hat ihm KBS-Mitarbeiter Senthosh Kumar (Foto S. 10) noch mal ausführlich<br />

erklärt, er ist der Chef dieser Bankniederlassung auf vier Rädern. Zwei seiner Kollegen haben<br />

zuvor Ramulus Kreditwürdigkeit überprüft: Bharu Prasad hat sich in Ramulus Heimatdorf Tirmalapur<br />

bei Freunden und Verwandten über ihn erkundigt („Schwiegereltern sind besonders<br />

ergiebig“, sagt er.), und Arul Kumar hat alle Angaben noch einmal nach dem Vier-Augen-Prinzip<br />

überprüft. Erst danach hält Ramulu das Geld in seinen Händen.<br />

Without Anjanaiah as his guarantor (photo left, r.), Janaki Ramulu (l.) wouldn't have got<br />

his loan. Anjanaiah agreed immediately, he tells us: he’s known Janaki since they were both<br />

children and is quite sure he won’t have to bail him out. But if the worst comes to the worst,<br />

he will be liable, as KBS employee Senthosh Kumar (far left) carefully explains. Senthosh is the<br />

manager <strong>of</strong> this branch <strong>of</strong>fice on four wheels. Two <strong>of</strong> his colleagues have already checked out<br />

Janaki’s creditworthiness: Bharu Prasad asked friends and relatives in Janaki’s home village <strong>of</strong><br />

Tirmalapur about him (“Parents-in-law are especially forthcoming,” he says), and Arul Kumar<br />

re-checked all his details, following the “two heads are better than one” principle. Only after<br />

all these checks have been made does Janaki get his hands on the cash.<br />

© JAN stradtmann<br />

FOCUS<br />

11

investieren das Geld in winziges Wachstum und zahlen davon das<br />

Geld alsbald zurück.<br />

Seltsam eigentlich. Welcher Artikel über den Lebensmittelkonzern<br />

Nestlé beginnt mit einem Kind, das voller Vorfreude in einen<br />

Schokoriegel beißt? Aber die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzbranche ist nun mal<br />

keine Branche wie jede andere. Sie verspricht nicht wie Nahrungsmittelkonzerne<br />

oder Kosmetikhersteller kurzfristige Konsumfreude,<br />

die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanciers bekämpfen die Armut dieser Welt. Populär<br />

gemacht von Friedensnobelpreisträger Muhammad Yunus und<br />

seiner Grameen-Bank und in den siebziger und achtziger Jahren<br />

zunächst dominiert von wohltätigen, gemeinnützigen Nichtregierungsorganisationen<br />

(Non Governmental Organisations, NGOs) ist<br />

das Geschäft mit den Mikrokrediten längst zu einer Milliardenindustrie<br />

gewachsen.<br />

Arme führen ein<br />

komplexes Finanzleben.<br />

2,7 Milliarden Menschen auf der Erde, das ist die Hälfte der<br />

arbeitenden Weltbevölkerung, leben von weniger als zwei Dollar<br />

am Tag. Im Durchschnitt wohlgemerkt: An vielen Tagen haben sie<br />

also weniger oder auch gar nichts, um ihren Lebensunterhalt zu<br />

bestreiten. Sie können es sich nicht leisten, von der Hand in den<br />

Mund zu leben. Sie müssen sorgsamer haushalten als Menschen<br />

mit einem höheren und vor allem regelmäßigen Einkommen. Für<br />

das Buch „Portfolios <strong>of</strong> the Poor“ haben Wissenschaftler Tagebücher<br />

über die Finanzen armer Menschen geführt. Damit belegen<br />

sie, wie komplex diese wirtschaften: Um für Notfälle vorzubeugen,<br />

sparen sie: Sie legen ihr Geld in den Schrank oder vertrauen<br />

es der Nachbarin an. Und sie haben meist gleich mehrere Kredite<br />

aufgenommen, um in schlechten Zeiten flüssig zu sein. Diese<br />

Darlehen kommen von Freunden, Nachbarn oder vom örtlichen<br />

Geldverleiher, der geharnischte Zinsen verlangt – nicht von Banken<br />

oder Versicherungen.<br />

Der Mikrokredit schien aus dieser Misere einen Ausweg zu<br />

ebnen, die Ärmsten der Armen an ein formalisiertes Finanzsystem<br />

anzudocken und so ihr Leben sicherer zu machen. Menschen<br />

wie Janaki Ramulu hatten plötzlich einen geordneten Zugang zu<br />

monetären Ressourcen, mussten sich nicht länger als Almosenempfänger<br />

der globalen Spendenindustrie fühlen. Ursprünglich<br />

für Gruppen von Frauen gedacht, die als zuverlässige Schuldner<br />

gelten, revolutionierte er die Entwicklungshilfephilosophie. Mikrokredite<br />

erfüllten das Postulat der Nachhaltigkeit, die Empfänger<br />

zahlten sie doch nebst Zinsen zurück, um sich alsbald den nächsten<br />

Kredit auszahlen zu lassen. Weil das Geschäft so Gewinne versprach,<br />

zog es nicht die üblichen verdächtigen Gutmenschen an,<br />

sondern auch kommerzielle Anbieter. Der Mikrokredit hilft den<br />

Armen, sich selbst zu helfen, und verspricht auch noch Pr<strong>of</strong>it für<br />

die Kapitalgeber. Das klingt fast zu schön, um wahr zu sein – dabei<br />

sind Kredite nicht das Einzige, was diese Menschen brauchen.<br />

try and are very poor; they apply for a loan, invest the money in a<br />

tiny growth scheme, and pay it back straight away.<br />

Poor people lead<br />

complex financial lives.<br />

Funny, isn’t it? How many articles about food giant Nestlé begin<br />

by telling you about a child, face shining in anticipation, biting into<br />

a chocolate bar? But the micr<strong>of</strong>inance industry isn’t like other industries.<br />

Unlike food or cosmetics manufacturers, it doesn’t promise<br />

short-term consumer gratification: micr<strong>of</strong>inanciers are combating<br />

global poverty. Made popular by Nobel peace prize winner<br />

Muhammad Yunus and his Grameen Bank, and then dominated<br />

throughout the ’70s and ’80s by philanthropic, not-for-pr<strong>of</strong>it nongovernmental<br />

organizations (NGOs), the microcredit business has<br />

grown into an industry worth billions.<br />

2.7 billion people on Earth – half <strong>of</strong> the world’s working population<br />

– live on less than two dollars a day. And that’s on average:<br />

many days they’ll be forced to earn a living on less – or even on<br />

nothing at all. They can’t afford to live hand to mouth: they husband<br />

their money much more carefully than people on higher –<br />

and above all, more regular – incomes. The scientists who wrote<br />

the book ‘Portfolios <strong>of</strong> the Poor’ kept diaries on poor people’s finances.<br />

They show just how complex their financial lives are. Just<br />

in case <strong>of</strong> emergencies, they save, stashing their money away in<br />

cupboards or entrusting it to neighbours. And most <strong>of</strong> them are<br />

also running multiple loans, so they can stay solvent through difficult<br />

times. These loans come from friends, neighbours or local<br />

moneylenders, who charge extortionate interest rates. Not from<br />

banks or insurance companies.<br />

Microcredit appeared to <strong>of</strong>fer a way out <strong>of</strong> this misery – a way<br />

to connect the poorest <strong>of</strong> the poor with a structured financial system<br />

and thus make their lives more secure. People like Janaki Ramulu<br />

suddenly had proper access to monetary resources; they no<br />

longer had to feel like charity cases, totally reliant on the global<br />

fund-raising industry. Originally conceived for groups <strong>of</strong> women –<br />

widely regarded as reliable debtors – the model revolutionised the<br />

philosophy <strong>of</strong> development aid. Microcredit satisfied the postulate<br />

<strong>of</strong> sustainability – debtors paid back their loans plus interest so<br />

they could immediately apply for new loans. Because the business<br />

promised to be pr<strong>of</strong>itable, it didn’t just attract the usual dubious<br />

do-gooders – it also attracted commercial providers. Microcredit<br />

helps poor people to help themselves, while promising pr<strong>of</strong>its to<br />

lenders. That sounds almost too good to be true – and yet loans<br />

aren’t the only thing poor people need.<br />

Which is why it’s no longer true – at least where Janaki Ramulu<br />

lives. His bank is one <strong>of</strong> the last commercial providers <strong>of</strong> microcredit<br />

in Andhra Pradesh. For a wide variety <strong>of</strong> reasons the micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

institutions (MFIs) that lived so well <strong>of</strong>f their dealings<br />

12 FOKUS

Anteil der Haushalte mit einem Konto bei einer Finanzinstitution /<br />

Fractions <strong>of</strong> households with an account in a financial institution<br />

> 80<br />

60-80<br />

40-60<br />

20-40<br />

< 20<br />

Quelle /Source: World Bank: <strong>Finance</strong> for All? 2008<br />

Deshalb ist es in Janaki Ramulus Heimat heute nicht mehr wahr.<br />

Seine Gläubigerbank ist einer der letzten kommerziellen Anbieter<br />

von Mikrokrediten in Andhra Pradesh. Die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitutionen<br />

(MFIs), die bis vor anderthalb Jahren sehr gut vom Geschäft<br />

mit den Armen gelebt haben, ringen heute allesamt mit der Pleite<br />

– aus verschiedenen Gründen. Nur wenige davon haben mit Menschen<br />

wie Janaki Ramulu zu tun. Obwohl sich doch eigentlich alles<br />

um sie drehen sollte.<br />

with the poor up until 18 months ago are now all struggling with<br />

bankruptcy. Very few <strong>of</strong> them have anything to do with people<br />

like Janaki Ramulu. But in fact, people like him are precisely what<br />

it should be about.<br />

Critics <strong>of</strong>ten confuse microcredit<br />

with micr<strong>of</strong>inance.<br />

Kritiker verwechseln Mikrokredite<br />

mit Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzen.<br />

Die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzkrise in Andhra Pradesh schien als Blaupause<br />

zu taugen für eine Geschichte, wie sie die Medien lieben. Eine<br />

Geschichte von Aufstieg und Absturz. Erst wurde der Mikrokredit<br />

hochgeschrieben, um dann seinen Fall zu beschwören – der<br />

Mikrokredit in Misskredit. Die einfache Version geht so: Die indischen<br />

Mikrokreditgeber hatten jedes Maß verloren, sie verliehen<br />

exzessiv Geld, gerne auch mehrere Kredite an einen Kunden.<br />

Dem Wachstum schienen keine Grenzen gesetzt. Die Leidtragenden<br />

dieses Pr<strong>of</strong>itstrebens waren die Kunden, die sie in die Überschuldung<br />

trieben, zumeist Frauen mit niedrigem Einkommen. Im<br />

Jahr 2010 schockten die Zeitungen mit Berichten von Selbstmorden<br />

Verzweifelter, das Geschäftsmodell der Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitute<br />

brach zusammen. Und diese regionale Krise in einem indischen<br />

The micr<strong>of</strong>inance crisis in Andhra Pradesh would appear to be<br />

the perfect blueprint for a story with instant media appeal – a<br />

classic rise followed by a dramatic fall. First microcredit is talked<br />

up, almost in anticipation <strong>of</strong> its subsequent plunge into disfavour:<br />

microcredit = discredit. The simple version goes as follows: Indian<br />

microlenders lose all sense <strong>of</strong> proportion – they lend too much<br />

money, happily making multiple loans to a single client, and business<br />

just keeps on growing. The victims <strong>of</strong> their pr<strong>of</strong>it drive are<br />

their massively indebted clients, most <strong>of</strong> them women on low incomes.<br />

In 2010 newspapers shock readers with reports <strong>of</strong> suicides<br />

by despairing debtors – and the MFI business model collapses. A<br />

regional crisis in one Indian federal state is enough to bring about<br />

the demise <strong>of</strong> the micr<strong>of</strong>inance concept.<br />

But in fact, the story isn’t so simple. It equates microcredit with<br />

micr<strong>of</strong>inance, assumes all MFIs are the same, and denies us the<br />

opportunity to learn from past mistakes. A good idea appears<br />

FOCUS<br />

13

„Manchmal überwog die gute PR.“<br />

”SOMETIMES THE Rhetoric OUTWEIGHED THE Reality.“<br />

Herr Ehrbeck, was kann die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzindustrie<br />

aus der Indien-Krise lernen?<br />

Die Fehler nicht zu wiederholen, die<br />

dort gemacht worden sind: Kurzfristige<br />

Kredite als einziges Produkt, sehr schnelles<br />

Wachstum, die mangelhafte Infrastruktur<br />

der Branche, die Überschätzung der Nachfrage<br />

für ein spezielles Produkt, für jene<br />

„Short Term Working Capital“-Kredite.<br />

sich das ändern muss, darüber sind sich Politik<br />

und Entscheidungsträger weltweit einig.<br />

Die G20 haben erst kürzlich fünf spezifische<br />

Empfehlungen dazu akzeptiert, auch wenn<br />

das wegen der Schuldenkrise keine Schlagzeilen<br />

macht. International gibt es einen<br />

Konsens und ein Momentum, die auch die<br />

Krise in Andhra Pradesh nicht stoppt. ‹<br />

CGAP plädiert dafür, unter Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzen<br />

nicht nur Mikrokredite zu verstehen.<br />

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzen gehen weit über den Mikrokredit<br />

hinaus. Aber weil beides <strong>of</strong>t verwechselt<br />

wird, sprechen wir inzwischen<br />

<strong>of</strong>t von „Zugang zu Finanzdienstleistungen“<br />

oder von „financial inclusion“ – der<br />

finanziellen Einbeziehung der Armen.<br />

Und selbst bei den Mikrokrediten geht<br />

es längst nicht mehr nur um Mikro-Unternehmer,<br />

sondern auch um die Bedürfnisse<br />

von normalen Haushalten. Die brauchen<br />

andere Dienstleistungen, mittel- und<br />

langfristige Kredite oder auch Konsumentenkredite.<br />

Die notwendige Diversifikation<br />

des Angebots gilt umso mehr für andere<br />

Dienstleistungen: Sparen, Geldtransfer,<br />

Versicherungen. Damit muss sich auch die<br />

Anbieterstruktur verändern. Für den Bereich<br />

Versicherungen zum Beispiel brauchen<br />

wir große, finanzstarke, geografisch<br />

diversifizierte Anbieter, die etwa eine<br />

Dürre in einer bestimmten Region nicht<br />

gleich in die Pleite treibt. Und wir brauchen<br />

neue, günstigere Geschäftsmodelle,<br />

die wie Mobilfunk-basierte Vertriebskanäle<br />

die Transaktionskosten dramatisch<br />

senken.<br />

Hat die Branche zu viel versprochen?<br />

Wenn man will, dass die Menschen einen<br />

lustig finden, reicht es nicht zu beteuern,<br />

man sei lustig. Man muss schon einen guten<br />

Witz erzählen. Bei Mikrokrediten überwog<br />

manchmal die gute PR. Wir müssen sicherstellen,<br />

dass Zugang zu Finanzdienstleistungen<br />

armen Familien in Entwicklungsländern<br />

auch wirklich hilft. Wie wichtig das ist, ist <strong>of</strong>fensichtlich,<br />

wenn man sich die Makro-Zahlen<br />

anschaut: Mehr als die Hälfte der arbeitenden<br />

Weltbevölkerung ist von formellen<br />

Finanzdienstleistungen abgeschnitten. Dass<br />

Mr Ehrbeck, what lessons can the micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

sector learn from the crisis in India?<br />

Not to repeat the mistakes that were<br />

made there – i.e. short-term lending as sole<br />

product, very rapid growth, inadequate industry<br />

infrastructure, and overestimating<br />

the demand for a specific product – those<br />

“short-term working capital” loans.<br />

For years CGAP has argued that “micr<strong>of</strong>inance”<br />

doesn’t equate to “microcredit”…<br />

Micr<strong>of</strong>inance represents much more<br />

than microlending. But because the<br />

two concepts are so <strong>of</strong>ten confused, we<br />

now <strong>of</strong>ten talk about “access to financial<br />

services” or “financial inclusion” – meaning<br />

financial inclusion <strong>of</strong> the poor – rather<br />

than micr<strong>of</strong>inance. We need to recognize<br />

that even microloans don’t just cater<br />

to micro-businesses, but also to ordinary<br />

households, which need other services like<br />

medium- and long-term loans or consumer<br />

credit. Diversification is even more important<br />

for other products such as savings,<br />

money-transfer schemes and insurance.<br />

Which means the supplier structure needs<br />

to change. In insurance, for example, we<br />

need large, well-financed, geographically<br />

diversified providers who aren’t immediately<br />

bankrupted when a particular region<br />

has a drought. And we need new, more<br />

affordable business models that can slash<br />

transaction costs, such as “mobile money”<br />

and distribution channels based on mobile<br />

telephony.<br />

Has the industry overpromised?<br />

If you want people to think you’re<br />

funny, it’s no good simply telling them<br />

you’re funny – you have to tell them a<br />

really good joke. Sometimes, the rhetoric<br />

in the microlending industry outweighed<br />

the reality. We need to make sure that<br />

Vita<br />

TILMAN EHRBECK ist seit Oktober 2010 CEO des internationalen<br />

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzforums CGAP unter dem Dach der Weltbank.<br />

Zuvor war er Partner der Unternehmensberatung<br />

McKinsey. Er hat in Afrika, Asien, Europa und Nordamerika<br />

gearbeitet und war zwischen 2005 bis 2009 Teil der Führungsebene<br />

für die Indienaktivitäten des Unternehmens.<br />

Tilman Ehrbeck, formerly a partner at consultancy firm<br />

McKinsey, has been CEO <strong>of</strong> international micr<strong>of</strong>inance forum<br />

CGAP, housed at the World Bank, since October 2010. He has<br />

worked in Africa, Asia, Europe and North America, and between<br />

2005 and 2009 was part <strong>of</strong> the senior management<br />

team in charge <strong>of</strong> the organisation’s Indian activities.<br />

products meet the true, underlying household<br />

needs and that access to financial<br />

services actually improves family welfare.<br />

Even so, if you look at the bigger picture,<br />

it’s obvious how important it is to move<br />

things forward: over half <strong>of</strong> the world’s<br />

working population has no access to formal<br />

financial services. This has to change<br />

– something that policymakers worldwide<br />

are mostly agreed on. Recently, the<br />

G20 accepted five specific recommendations<br />

on this issue, although it didn’t make<br />

the headlines because <strong>of</strong> the debt crisis.<br />

There is a consensus and momentum in<br />

the broader financial inclusion space that<br />

goes beyond microcredit and that the crisis<br />

in Andhra Pradesh is not going to stop. ‹<br />

© CGAP<br />

14 FOKUS

Bundesstaat musste dafür herhalten, den Niedergang der Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzidee<br />

zu bezeugen.<br />

Doch diese Erzählung greift zu kurz. Sie verwechselt Mikrokredit<br />

mit Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzen, sie wirft alle MFIs in einen Topf, und sie verweigert<br />

die Chance, aus der Vergangenheit zu lernen. Eine gute<br />

Idee schien vorschnell abgeschrieben, paradoxerweise in einer<br />

Phase, in der die Branche endlich genügend Kapital angezogen<br />

hatte, um tatsächlich die Welt zu verändern. Dabei sollte es jetzt<br />

doch vor allem darum gehen, herauszufinden, ob und wo die Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzbewegung<br />

vom Weg abgekommen ist. Und ob ihnen<br />

neue Technologien helfen könnten, wieder auf den rechten Weg<br />

zurückzufinden. Die indischen MFIs sind dabei, ihren Weg zu suchen.<br />

Nicht jede wählt denselben.<br />

Gefangen im Dilemma zwischen<br />

Unternehmer- und Gutmenschentum.<br />

Deshalb hätte diese Geschichte vielleicht besser mit Männern<br />

im mittleren Alter beginnen sollen, Männer in Hemden und Anzügen,<br />

an Schreibtischen und in Konferenzräumen. Männer wie Nitin<br />

Agrawal. Agrawal ist der Strategiechef von Spandana Sphoorty,<br />

eine der größten kommerziellen MFIs Indiens. Spandana hat seine<br />

Firmenzentrale an einer Ausfallstraße der Landeshauptstadt Hyderabad<br />

hochgezogen. Nach indischen Maßstäben ein Prachtbau<br />

aus Glas und Stein; der europäische Blick sieht eine fast niedliche<br />

Miniatur eines westlichen Banken-Headquarters. Spandana – 34,4<br />

Milliarden Rupien Kreditportfolio, 5,2 Millionen Kunden – wollte<br />

eigentlich an die Börse, im Windschatten der ebenfalls aus Andhra<br />

Pradesh operierenden SKS Micr<strong>of</strong>inance. Fünf der größten<br />

MFIs Indiens haben in diesem Bundesstaat ihren Sitz. Jedenfalls<br />

galt das so bis vor einem Jahr. Heute, sagt Agrawal, zahlt nicht mal<br />

jeder 20. Kunde seinen Kredit zurück, früher protzte die Branche<br />

mit Rückzahlungsraten von 99 Prozent und mehr. Umzukehren sei<br />

das nicht mehr, glaubt Agrawal. Das sei, als wenn man Menschen,<br />

denen man jahrelang eingebläut habe, sie dürften Gott nicht anlügen,<br />

auf einmal erkläre, das sei schon in Ordnung.<br />

Nitin Agrawal hat sich dafür entschieden, sich vom Ballast der<br />

Weltveränderungsversprechen und damit von Verantwortung loszusagen.<br />

Er sagt an dem Intarsien-verzierten Konferenztisch in<br />

der Firmenzentrale: „Unser Geschäft ist nicht der Kampf gegen<br />

Armut. Wenn unsere Kredite die Lebensumstände der Leute verbessern,<br />

ist das Zufall.“ Ein seltsamer Zufall ist es allerdings, dass<br />

Spandanas Webseite diese vermeintlich klare Botschaft dann doch<br />

lieber nicht kommuniziert und stattdessen mit einer Bilderflut<br />

glücklicher Armer für sich wirbt: Auch Spandana bleibt im Dilemma<br />

zwischen Unternehmer- und Gutmenschentum gefangen.<br />

In Indien leben über eine Milliarde Menschen, 70 Prozent davon<br />

in ländlichen oder semiurbanen Gegenden, 260 Millionen unter<br />

der Armutsgrenze, das Land ist ein perfekter Nährboden für<br />

to have been dismissed prematurely – paradoxically at a time<br />

when the industry has finally attracted enough capital to bring<br />

about real change. And yet the main issue is surely to establish<br />

whether – and whither – the micr<strong>of</strong>inance movement lost its way,<br />

and whether new technologies could help give it back its sense <strong>of</strong><br />

direction. MFIs in India are searching for the right way to go: not<br />

all <strong>of</strong> them are making the same choices.<br />

Caught in the dilemma between<br />

entrepreneurialism and idealism.<br />

So perhaps the story should have started with middle-aged<br />

men in elegant suits and ties sitting at <strong>of</strong>fice desks or in meeting<br />

rooms. Men like Nitin Agrawal. Agrawal is head strategist at Spandana<br />

Sphoorty, one <strong>of</strong> India’s largest commercial MFIs, with its<br />

head <strong>of</strong>fice next to one <strong>of</strong> the arterial roads in the state capital <strong>of</strong><br />

Hyderabad. By Indian standards, it’s a magnificent steel-and-glass<br />

building – to European eyes it looks rather like a charmingly miniaturised<br />

version <strong>of</strong> the headquarters <strong>of</strong> some Western bank. Spandana<br />

– with a loan portfolio worth 34.4 billion rupees and 5.2<br />

million clients – was hoping to go public in the wake <strong>of</strong> SKS Micr<strong>of</strong>inance,<br />

which also operates out <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh. Five <strong>of</strong> India’s<br />

biggest MFIs are based in the state – or at least, they were up to a<br />

year ago. Nowadays, says Agrawal, not even one in 20 clients pay<br />

back their loan, whereas earlier the industry boasted repayment<br />

rates <strong>of</strong> 99% or more. In Agrawal’s view, the change is irreversible.<br />

It’s as if you suddenly told people who for years had firmly<br />

believed you should never lie to God that, actually, it’s okay to lie.<br />

Nitin Agrawal has decided to liberate himself from the burden<br />

<strong>of</strong> world-changing idealism, hence from the associated responsibility.<br />

Sitting at the inlaid conference table in the company’s head<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice, he states: “we’re not in the business <strong>of</strong> fighting poverty. If<br />

our loans improve people’s living conditions, it’s purely accidental.”<br />

Perhaps it's also accidental that Spandana's website prefers<br />

not to communicate this apparently unambiguous message. Instead,<br />

the MFI's services are promoted by a mass <strong>of</strong> photos showing<br />

happy, smiling borrowers. Even Spandana is still caught in the<br />

dilemma between entrepreneurialism and idealism.<br />

There are over one billion people living in India, 70% <strong>of</strong> them in<br />

rural or semiurban areas, 260 million below the poverty line: the<br />

country is the perfect breeding ground for a booming microcredit<br />

industry. With microloans, even the poorest can enjoy the economic<br />

upswing with which India’s emerging economy has been impressing<br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> the world for the last few years. For economic<br />

growth and societal development don’t necessarily happen in parallel,<br />

as made clear in an article published recently by Nobel economics<br />

laureate Amartya Sen working with Jean Dreze. Yes, India’s<br />

economy is one <strong>of</strong> the fastest-growing in the world after China.<br />

Between 1990 and 2010 per-capita income grew at an average annual<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> almost 5%. But at the same time, according to the<br />

FOCUS<br />

15

Indien – Land der Kontraste<br />

India – country <strong>of</strong> contrasts<br />

Zwischen Reich und Arm klafft eine Schere auf dem Subkontinent, der rasante Aufschwung<br />

der vergangenen 20 Jahren hat die Armen des Landes nicht erreicht. Zwischen 2002<br />

und 2007 wuchs das indische Bruttoinlandsprodukt um durchschnittlich 7,8 Prozent, zwischen<br />

2007 und 2012 vermutlich um acht Prozent. Und dennoch: Den “World Development Indicators<br />

2011” zufolge gibt es nur 16 nicht-afrikanische Länder, die ein niedrigeres Bruttonationaleinkommen<br />

pro Kopf hatten als Indien.<br />

The gulf between rich and poor yawns wider than ever on the subcontinent: the rapid<br />

growth <strong>of</strong> the past 20 years has failed to reach the country’s poor. Between 2002 and 2007 India’s<br />

GDP grew by 7.8% a year on average – between 2007 and 2012 the figure was probably<br />

closer to 8%. And yet according to ‘World Development Indicators 2011’ there are only 16 non-<br />

African countries with a lower gross national income per capita than India.<br />

16 FOKUS

© JAN stradtmann<br />

Indien im Vergleich mit Seinen Nachbarn<br />

HOW INDIA RANKS IN SOUTH ASIA<br />

IN<br />

1990<br />

AROUND /<br />

UM 2009<br />

Pro-Kopf-Bruttonationaleinkommen / GNI per capita 4 3<br />

Lebenserwartung / Life expectancy 3 6<br />

Kindersterblichkeit / Infant mortality rate 2 5<br />

Müttersterblichkeit / Maternal mortality rate 3 3<br />

Indiens Rang innerhalb von sechs asiatischen Ländern /<br />

India's rank among six South Asian countries (Bangladesh,<br />

Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka). Top =1, Bottom=6.<br />

a=uneindeutiges Ranking aufgrund fehlender Daten aus<br />

Bhutan (oder Nepal im Falle untergewichtiger Kinder) /<br />

ambiguous ranking due to missing data from Bhutan (or<br />

Nepal in the case <strong>of</strong> "underweight children").<br />

Geburtenrate / Total fertility rate 2 4<br />

Sanitäre Verhältnisse / Access to improved sanitation 4-5a 5-6a<br />

Kinder-Impfrate (DPT) / Child immunisation (DPT) 4 6<br />

Kinder-Impfrate (Masern) / Child immunisation (measles) 6 6<br />

Dauer der Schulbildung / Mean years <strong>of</strong> schooling 2-3a 4-5a<br />

Alphabetisierte Frauen, 15-24 Jahre / Female literacy rate, 15-24 2-3a 4<br />

Untergewicht bei Kindern / Proportion <strong>of</strong> underweight children 4-5a 6<br />

Quelle /Source: Jean Drèze , Amartya Sen: Putting Growth In Its Place. Outlook India Magazine. 14. November 2011<br />

FOCUS<br />

17

den Boom des Mikrokredits. Mit den Minidarlehen sollten auch die<br />

Ärmsten der Armen am wirtschaftlichen Aufschwung teilhaben,<br />

mit dem das Schwellenland seit Jahren beeindruckt. Wirtschaftswachstum<br />

und Entwicklung müssen nicht Hand in Hand gehen,<br />

das zeigt ein kürzlich veröffentlichter Artikel, den Wirtschaftsnobelpreisträger<br />

Amartya Sen zusammen mit Jean Drèze verfasst<br />

hat. Zwar wächst die indische Wirtschaft nach China am schnellsten.<br />

Das Pro-Kopf-Einkommen ist zwischen 1990 und 2010 jährlich<br />

um durchschnittlich fast fünf Prozent gestiegen. Gleichzeitig<br />

aber haben der Weltbank zufolge nur fünf Länder außerhalb Afrikas<br />

einen höheren Anteil an jungen Analphabetinnen, nur vier<br />

eine höhere Kindersterblichkeitsrate, und kein einziges, auch kein<br />

afrikanisches, hat einen höheren Prozentsatz untergewichtiger<br />

Kinder. 20 Jahre rasanten Wachstums lassen leicht vergessen, dass<br />

Indien immer noch eines der ärmsten Länder der Welt ist. Der Aufschwung<br />

hat große Teile des Volkes zurückgelassen.<br />

Den Armen geht es nicht<br />

um die Kreditkosten.<br />

„Financial Inclusion“, also den Armen Zugang zu Finanzdienstleistungen<br />

zu verschaffen, bedeutet weit mehr, als ein Land oder<br />

eine Region mit Mikrokrediten zuzuschütten. Doch in Indien und<br />

vor allem in Andhra Pradesh reduzierte sich das Konzept nur auf<br />

dieses eine Produkt. Die meisten kommerziellen Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitute<br />

Indiens sind rechtlich so genannte NBFCs, „non banking<br />

financial companies“. Sie sind weniger reguliert als gewöhnliche<br />

Banken und dürfen deshalb ausschließlich Kredite vergeben<br />

– das Geschäft mit Spareinlagen untersagt ihnen der Gesetzgeber.<br />

Um der ländlichen Bevölkerung Zugang zu Finanzdienstleistungen<br />

zu ermöglichen, hatte die Regierung verfügt, dass von<br />

World Bank, only five countries outside Africa have a higher level <strong>of</strong><br />

youth illiteracy; only four have a higher infant mortality rate; and no<br />

other country – not even in Africa – has a higher percentage <strong>of</strong> underweight<br />

children. 20 years <strong>of</strong> rapid growth make it easy to forget<br />

that India is still one <strong>of</strong> the poorest countries in the world. The upswing<br />

has left large parts <strong>of</strong> the population behind.<br />

Poor people don’t worry<br />

about the cost <strong>of</strong> a loan.<br />

“Financial inclusion” – that is, including the poor in a formal financial<br />

services structure – means much more than simply handing<br />

out microloans. But in India, and above all, in the state <strong>of</strong><br />

Andhra Pradesh, the micr<strong>of</strong>inance concept was narrowed down<br />

to a single product: microcredit. Most commercial MFIs in India<br />

take the legal form <strong>of</strong> NBFCs (non-banking financial companies).<br />

They are not as heavily regulated as conventional banks, hence<br />

may only issue loans – the law forbids them to handle savings<br />

deposits.<br />

To help the rural population gain access to financial services,<br />

the Government decreed that 40 out <strong>of</strong> every 100 rupees lent by<br />

normal commercial banks should go to small businesses in rural<br />

areas or in farming. The banks themselves were reluctant to spend<br />

money on extending their distribution networks into the remotest<br />

corners <strong>of</strong> India in order to reach rural populations: they much<br />

preferred to lend their money to MFIs at interest rates <strong>of</strong> 11-12%.<br />

In turn, the MFIs charged their clients interest rates <strong>of</strong> 30% or<br />

more. “Poor people don’t worry about the cost <strong>of</strong> a loan – they<br />

worry about having access to money,” remarks Indian journalist<br />

Tamal Bandyopadhyay, who has been observing the industry<br />

Vergleich des WirtschaftswachstumS Indiens mit der Welt seit 1970<br />

Comparative growth <strong>of</strong> India’s GDP vs. global GDP since 1970<br />

10,0<br />

7,5<br />

5,0<br />

2,5<br />

0,0<br />

-2,5<br />

-5,0<br />

World<br />

India<br />

1970<br />

1980 1990 2000 2010<br />

Quelle /Source: World Bank<br />

18 FOKUS

„Ein Sparkonto schützt auch vor Termiten.“<br />

”A SAVINGS ACCOUNT EVEN PROTECTS AGAINST TERMITES.“<br />

Herr Adler, welche Zukunft hat der Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzsektor?<br />

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung hat sich weltweit als<br />

Erfolgsgeschichte bestätigt, auch in Krisenzeiten<br />

– die nach wie vor guten Rückzahlungsquoten<br />

belegen dies. Millionen<br />

von armen Menschen werden nachhaltig<br />

mit angepassten Finanzdienstleistungen<br />

wie Kredit, Sparen, Zahlungsverkehr und<br />

Versicherungen versorgt. Gleichwohl gilt<br />

es, Fehlentwicklungen vorzubeugen, um<br />

den nach wie vor hohen Bedarf an Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung<br />

zu decken. Die Krise in Andhra<br />

Pradesh darf man dabei zwar nicht<br />

überschätzen, da nicht nur die Auswirkungen<br />

weltweit, sondern sogar die auf das<br />

restliche Indien beschränkt waren. Aber<br />

daraus konnte man wieder einmal lernen,<br />

dass die Bemühungen um angemessene<br />

Kreditvergabestandards von größter<br />

Bedeutung sind. Und wir haben gesehen,<br />

dass eher solche Institutionen verwundbar<br />

sind, die nur Mikrokredite anbieten und<br />

nicht ein breiteres Spektrum an Finanzprodukten,<br />

wie etwa Ersparnismobilisierung.<br />

Warum ist das so wichtig?<br />

Menschen, die von zwei Dollar am Tag<br />

leben, haben neben Krediten noch andere<br />

Bedürfnisse. Da tut sich auch eine Menge:<br />

Mikroversicherungen etwa stecken zwar<br />

noch in den Kinderschuhen, entwickeln<br />

sich aber dynamisch. Darüber hinaus sehe<br />

ich beim „Mobile Banking“ eine noch stärkere<br />

Dynamik, da es die Chance birgt, kostengünstig<br />

arme Menschen auf dem Land<br />

zu erreichen. Mikrosparen ist eine besondere<br />

Herausforderung. Wir brauchen<br />

dafür unbedingt stabile, gut regulierte Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzinstitutionen.<br />

Das ist nicht nur eine Frage der Regulierung,<br />

sondern auch des Kapitals.<br />

Richtig, man braucht Kapitalgeber, um<br />

diese Entwicklung zu unterstützen. Deshalb<br />

ist es wichtig, auch Anreize für die<br />

Privatwirtschaft zu schaffen. Spareinlagen<br />

bedeuten auch eine Chance für die MFIs.<br />

Zurzeit sind sie auf Banken angewiesen,<br />

auf externe Finanziers wie die KfW. Diese<br />

bieten zwar Refinanzierungsmöglichkeiten<br />

an, aber meist nicht in Rupien – oder Pesos<br />

oder Taka –, sondern in Dollar oder Euro.<br />

Wegen des Wechselkursrisikos ist diese externe<br />

Refinanzierung mitunter teurer als<br />

lokale Ersparnisse anzunehmen. Und aus<br />

Sicht der Armen ist Sparen selbst dann<br />

sinnvoll, wenn der Habenzins negativ ist.<br />

Denn auf dem Bankkonto ist das Geld sicher<br />

– vor Diebstahl, vor Verwandten oder<br />

auch vor Termitenbefall. ‹<br />

What future does the micr<strong>of</strong>inance sector<br />

have?<br />

Even in times <strong>of</strong> crisis, it is clear that micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

really does work, on a global<br />

scale – as shown by repayment rates,<br />

which are still good. Millions <strong>of</strong> poor people<br />

are sustainably provided with appropriate<br />

financial services such as loans, savings<br />

accounts, payment transactions and insurance.<br />

Nonetheless, it is important to obviate<br />

inappropriate developments so we can<br />

meet the ongoing high demand for micr<strong>of</strong>inance.<br />

Of course we shouldn’t overrate<br />

the crisis in Andhra Pradesh, because<br />

globally – and even in the rest <strong>of</strong> India –<br />

the crisis only had a limited impact. But it<br />

did teach us, once again, that our efforts<br />

to establish suitable lending standards are<br />

vitally important. And we’ve clearly seen<br />

how vulnerable institutions can be if they<br />

only <strong>of</strong>fer microloans and don’t <strong>of</strong>fer a<br />

broader range <strong>of</strong> financial products – by<br />

encouraging people to save, for example.<br />

Why is that so important?<br />

People living on two dollars a day need<br />

more than just loans. There’s plenty going<br />

on, I’m glad to say: microinsurance has<br />

only just started to take <strong>of</strong>f, but is developing<br />

fast. In my view, the progress in mobile<br />

banking is even more impressive, because<br />

it represents a great opportunity to reach<br />

poor people in rural areas cost-effectively.<br />

Microsaving is a particular challenge –<br />

for that to work, we really do need stable,<br />

well-regulated micr<strong>of</strong>inance institutions.<br />

It’s not just a question <strong>of</strong> regulation, but<br />

<strong>of</strong> capital, too.<br />

Quite right, you need investors to support<br />

this development. That’s why it’s<br />

Vita<br />

Matthias Adler begleitet seit mehreren Jahren bei der<br />

KfW Entwicklungsbank das Thema Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung. Er ist<br />

Mitglied im Executive Committee des internationalen Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzforums<br />

CGAP und wirkt als Aufsichtsratsmitglied in<br />

Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanz-Holdings an der Umsetzung verantwortungsvoller<br />

Praktiken im Bereich Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzierung mit.<br />

Matthias Adler has been working on micr<strong>of</strong>inance issues<br />

at KfW development bank for many years. He’s a member <strong>of</strong><br />

the Executive Committee <strong>of</strong> international micr<strong>of</strong>inance forum<br />

CGAP, and as a member <strong>of</strong> the supervisory boards <strong>of</strong> several<br />

micr<strong>of</strong>inance holding companies, is instrumental in introducing<br />

responsible practices into the micr<strong>of</strong>inance sector.<br />

important to provide incentives for the<br />

private sector. Savings deposits also represent<br />

an opportunity for micr<strong>of</strong>inance<br />

institutes. At present they have to rely<br />

on banks – on external financiers such as<br />

KfW. While they do <strong>of</strong>fer various funding<br />

options, they don’t usually <strong>of</strong>fer them in<br />

rupees (or pesos or taka), but in dollars<br />

or euros. Because <strong>of</strong> exchange rate risks,<br />

it’s usually more expensive to take on this<br />

external funding than local savings. And<br />

from the viewpoint <strong>of</strong> poor borrowers,<br />

it makes sense to save even if the credit<br />

interest is negative, simply because their<br />

money is much safer in a bank account –<br />

from theft, from relatives, even from termite<br />

infestations! ‹<br />

© KFW<br />

FOCUS<br />

19

DER LOBBYIST<br />

the LOBBYIST<br />

DER BERATER<br />

THE CONSULTANT<br />

„Indien ist ein schwieriger Markt“, sagt Manoj Sharma. Er hat 20 Jahre Erfahrung in der<br />

Entwicklungsfinanzierung. Wir treffen den gut informierten und freundlichen Experten auf der<br />

Durchreise am Flughafen Delhi, er ist auf dem Weg zur Microsave-Zentrale in Lucknow, von wo<br />

aus er die indischen Aktivitäten des Beratungsunternehmens koordiniert, das auch in Kenia,<br />

Uganda, Argentinien und auf den Philippinen Hauptquartiere aufgeschlagen hat. Dass den<br />

NBFCs – „non banking financial companies“ – Spareinlagen verboten seien, kann Sharma nachvollziehen,<br />

nachdem eine Reihe von ihnen in den Neunzigern das Geld ihrer Kunden verloren<br />

hatten. Dass die Regierung nun versucht, die regulären Geschäftsbanken aufs Land zu schicken,<br />

etwa durch Business Correspondents, hält er für richtig – im Gegensatz zu den zahlreichen kleinen<br />

MFIs seien sie leichter zu überwachen. Und das schütze die Kunden.<br />

Alok Prasad hat früher für die Citigroup und für die Reserve Bank <strong>of</strong> India gearbeitet.<br />

Seinen Job als CEO des erst gut zwei Jahre alten NBFC-Netzwerks MFIN (Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Institutions<br />

Network) hat er nur wenige Monate vor dem Ausbruch der Krise angetreten. Viele Fehler<br />

seien gemacht worden, glaubt er. Eben erst hat der Verband deshalb einen neuen Code <strong>of</strong> Conduct<br />

verfasst. Bei den Verhandlungen mit der Landesregierung von Andhra Pradesh ist MFIN<br />

hingegen bisher nicht weit gekommen: Im Austausch für eine NBFC-freundlichere Gesetzgebung<br />

bot er vergeblich eine Umschuldung der Kunden an. Nun warnt Prasad davor, dass die<br />

säumigen Schuldner auf die schwarze Liste des kürzlich gegründeten National Credit Bureau<br />

– einer Art Schufa – geraten. Ob dieses Credit Bureau allerdings heute schon effektiv arbeitet,<br />

bezweifeln viele Brancheninsider.<br />

Earlier in his career, Alok Prasad worked for Citigroup and the Reserve Bank <strong>of</strong> India.<br />

He started his job as CEO <strong>of</strong> Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Institutions Network MFIN – an NBFC network that<br />

only recently celebrated its second birthday – just a few months before the micr<strong>of</strong>inance crisis.<br />

He believes many mistakes were made, which is why the association has just drawn up<br />

a new code <strong>of</strong> conduct. Negotiations with the state government <strong>of</strong> Andhra Pradesh, on the<br />

other hand, have not made much progress: in vain did he <strong>of</strong>fer to restructure clients’ debts<br />

in exchange for legislation that’s friendlier to NBFCs. Now Prasad is warning that defaulting<br />

debtors are being blacklisted by the recently founded National Credit Bureau, a credit protection<br />

association along the lines <strong>of</strong> Germany’s SCHUFA. However, many industry insiders doubt<br />

that the credit bureau is working effectively just yet.<br />

“India is a difficult market,” asserts Manoj Sharma: he’s been working in development finance<br />

for 20 years. We meet the amiable and well-informed expert at Delhi airport, as he pauses<br />

on his journey to Microsave’s head <strong>of</strong>fice in Lucknow, where he coordinates the consultancy’s<br />

activities in India (the firm also has head <strong>of</strong>fices in Kenya, Uganda, Argentina and the Philippines).<br />

Sharma can understand why NBFCs (non-banking financial companies) were forbidden<br />

from handling savings deposits, after a whole row <strong>of</strong> them lost their clients’ money back in the<br />

’90s. He also thinks it’s right that the Government is now trying to link up conventional commercial<br />

banks with rural clients, for example through the Business Correspondence initiative: unlike<br />

the many small MFIs, ordinary banks are easier to supervise, which helps protect their clients.<br />

20 FOKUS

DER INVESTOR<br />

the investor<br />

DER BANKDIREKTOR<br />

THE BANK DIRECTOR<br />

„Wir sind nicht nur eine Bank, wir wollen die Lebensumstände der Landbevölkerung verbessern.“<br />

Vijay Nadkarni ist der Chef einer kleinen und besonderen Bank, der 2001 gegründeten<br />

Local Area Bank KBS. Die einzige Mikr<strong>of</strong>inanzbank Indiens agiert nur in vier Distrikten.<br />

Sie gehört zum Unternehmenskonglomerat BASIX, das Vijay Mahajan (siehe Interview S. 30)<br />