Daniel Lezama Travelers

978-3-86859-187-3

978-3-86859-187-3

- Keine Tags gefunden...

Erfolgreiche ePaper selbst erstellen

Machen Sie aus Ihren PDF Publikationen ein blätterbares Flipbook mit unserer einzigartigen Google optimierten e-Paper Software.

TRAVELERS<br />

Herausgegeben von | Edited by:<br />

Jürgen Krieger<br />

Interview von | by:<br />

Mauricio Galguera<br />

Essays von | by:<br />

Harald Kunde<br />

Erik Castillo<br />

Francesco Pellizzi<br />

Hilario Galguera<br />

DANIEL<br />

Ein besonderer Dank an Hilario und Mauricio Galguera für die Realisierung dieses Buches.<br />

A special thank to Hilario and Mauricio Galguera for the realization of this book.<br />

LEZAMA

INHALTSÜBERSICHT<br />

CONTENT<br />

12 13<br />

»MEIN HERZ SEHNT SICH IMMER NACH<br />

DEM WESENTLICHEN, nach dem Ursprünglichen,<br />

der Entstehung, natürlich nicht im Hinblick auf<br />

Annehmlichkeiten der Lebewesen, aber im Hinblick auf<br />

existenzielle und SPIRITUELLE NOTWENDIGKEITEN.<br />

Die Elemente, die Reiche, die Behausungen, der Schutz,<br />

das Verlangen, die Notwendigkeit, der Tod, die<br />

Wieder geburt: was in aller Welt könnte interessanter sein?<br />

VIELE DINGE, SAGT DIE WELT.« DANIEL LEZAMA<br />

»My heart always yearns for the essential, for the primordial,<br />

for the origin, not of course in terms of creature comforts, but<br />

in terms of existential and spiritual necessity. THE ELEMENTS,<br />

THE REALMS, DWELLING, PROTECTION, DESIRE, NECESSITY,<br />

DEATH, REBIRTH, WHAT ON EARTH COULD BE MORE<br />

INTERESTING THAN THAT? Lots of things, says the world.«<br />

DANIEL LEZAMA<br />

Mauricio Galguera<br />

Ein kurzer Gedankenaustausch mit <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> 14<br />

A brief exchange of thoughts with <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong><br />

Harald Kunde<br />

Schaubühnen der Imagination<br />

Anmerkungen zum Bildprogramm von <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> 28<br />

Stages for the imagination<br />

Notes of <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>‘s pictorial program<br />

Erik Castillo<br />

Briefe aus weiter Ferne<br />

Gemälde von <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>, 2009 – 2011 130<br />

Letters from a unfathomable distance<br />

Paintings by <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>, 2009 – 2011<br />

Francesco Pellizzi<br />

Ent-Täuschungen und Kapricen des <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> 144<br />

Ein italienischer Blickpunkt<br />

Dis-Enchantments and Caprices of <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong><br />

An Italien viewpoint<br />

Hilario Galguera<br />

Allegorien der Fahne 174<br />

Allegories of the flag<br />

Mauricio Galguera<br />

Biografie / Biography 203<br />

Hilario Galguera 204<br />

Anmerkungen zu einem kleinen Gemälde<br />

Schlusspunkt der Gemäldeserie »<strong>Travelers</strong>«<br />

Notes on a small painting<br />

The conclusion of the »<strong>Travelers</strong>« series<br />

Impressum / Imprint 208

16 17<br />

: Der Tod des Empedokles<br />

The death of Empedocles<br />

2005<br />

Oil on linen, 190 x 230 cm<br />

Colección, Monterrey, Mexico

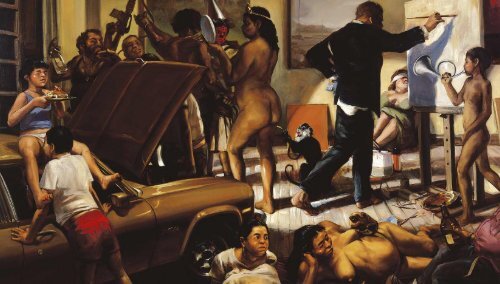

Geradezu programmatisch hat sich diese<br />

Haltung in seinem Zyklus der Traveler-Serie<br />

niedergeschlagen, den er seit einigen<br />

Jahren verfolgt und der Protagonisten<br />

namentlich des 19. Jahrhunderts gewidmet ist, deren Biografie und Denkhorizont nachhaltig<br />

durch die Begegnung mit der Neuen Welt geprägt wurde. Wissenschaftler, Künstler, Abenteurer<br />

– all jene, die nach den Konquistadoren, den Missionaren und Händlern kamen und in ihren jeweils<br />

verfolgten Unternehmungen trotz friedlicher Absichten immer von Gefahren, Krankheiten und<br />

anderen existenziellen Unwägbarkeiten begleitet waren – bilden dabei den illustren Reigen, den<br />

<strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> sich einverleibt und dem er sich als zeitenferner Gefährte zugesellt. In der Arbeit<br />

Selbstbildnis als J. M. Rugendas von 2008 zeigt er sich denn auch als nackter Knabe, der auf den<br />

Spuren des gebürtigen Augsburger Künstlers Johann Moritz Rugendas zum Eleven der Malerei<br />

heranreift. Der süddeutsche Landschaftsmaler, der neben einem dreijährigen Aufenthalt in Mexiko<br />

auch mehrere Jahre in Brasilien und Chile verbrachte und von Alexander von Humboldt wohlwollend<br />

gefördert wurde, galt als exquisiter Topograph, dessen vor der Natur entstandene Bleistiftzeichnungen<br />

samt präziser Farbangaben später in Ölstudien ausgeführt wurden und genauere Vorstellungen<br />

über den noch weithin als terra incognita geltenden Kontinent herausbilden halfen. Im<br />

wiedererlangten Stand dieser visuellen Unschuld des Anfangs begreift sich <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> offenbar<br />

als legitimer Nachfolger dieser konstatierenden Betrachtungsweise; eifrig und doch schutzlos steht<br />

er auf der Hochebene des Vulkanmassivs des Popocatépetl und erwartet die weiteren Weisungen<br />

des Meisters. Von dieser ostentativen Verhaltenheit ist in der nur wenig später entstandenen Arbeit<br />

Der Farbenbaum von 2010 nichts mehr zu spüren: in einer alchemistisch<br />

anmutenden Szenerie, die wie ein Albtraum vor dem nun<br />

erwachsenen, doch noch immer nackten Maler aufsteigt, vollzieht<br />

sich das Mysterium der Farbgewinnung aus zerriebenen Mineralien.<br />

In großen Schalen werden die flüssigen Primärfarben gesammelt, bevor<br />

sie in verschiedenen Abmischungen über zwei kopfüber gefesselte<br />

Gestalten – eine schwangere Frau und einen nur mühsam gebändigten<br />

Jungen – gegossen werden und hernach in feurigen Bächen den titelgebenden<br />

Farbenbaum umspülen. Das magische Gewächs, quasi ein<br />

30 This position takes on virtually programmatic proportions in his Traveler<br />

31<br />

Series cycle, which he has pursued for several years and which is<br />

specifically dedicated to protagonists of the nineteenth century whose<br />

biographies and intellectual horizons were profoundly shaped by their<br />

encounters with the New World. Scientists, artists and adventurers – all<br />

of those who arrived after the conquistadors, missionaries and merchants,<br />

and whose undertakings were always accompanied by danger, sickness<br />

and other existential imponderables despite their peaceful intentions –<br />

constitute the illustrious cast that <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> adopts and joins as a<br />

companion from another time. In Self-Portrait as J. M. Rugendas from<br />

2008, he depicts himself as a naked boy who matures into a student<br />

of painting on the heels of the Augsburg-born artist Johann Moritz<br />

Rugendas. The South-German landscape painter, who spent several<br />

years in Brazil and Chile in addition to a three-year sojourn in Mexico<br />

<strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> the metaphysical<br />

and was the beneficiary of Alexander von Humboldt’s support, was<br />

points of reference that allow him<br />

considered an exquisite topographer. His pencil drawings and precise<br />

to orient himself in the various<br />

coloring instructions were drawn from nature and later painted as oil<br />

processes of pictorial composition,<br />

studies, helping to shape more accurate ideas about a continent that<br />

and which are essential to his<br />

was still largely thought of as terra incognita. <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> evidently<br />

artistic positioning. A third<br />

considers himself a legitimate successor to this observational point of<br />

example of this latent questioning<br />

view from a position of the reclaimed visual innocence of the beginning.<br />

of his own position as an artist to<br />

Enthusiastic and defenseless, he stands on the plateau of the volcanic<br />

be found in the Traveler Series is<br />

massif of Popocatépetl and awaits further instruction from the master.<br />

Equator (new painter,<br />

None of this ostentatious reverence remains in The color tree, executed<br />

new model). Executed in 2009,<br />

shortly afterwards, in 2010. The mystery of making paint from ground<br />

it depicts in a haunting manner<br />

minerals takes place in alchemistic-looking scenery that looms like a<br />

the sudden clash of Indian and<br />

nightmare in front of the painter, who has grown up but is still nude. The<br />

European cultures. In a jungle-like<br />

liquid primary colors are collected in large bowls before they are poured<br />

thicket in which the giant trees<br />

in various combinations over two figures (a pregnant woman and an<br />

have anthropomorphic features<br />

arduously restrained boy), who have been fettered upside-down, and<br />

and function as male and female<br />

finally swirl around the eponymous color tree in fiery rivers. This magical<br />

guards, our attention is drawn to<br />

plant, essentially a symbol of painting, illuminates the concrete night like<br />

a bizarre scene by the camp fire:<br />

any other dramatic event: wherever it glows, it gives hope and meaning<br />

in the foreground, a naked boy<br />

Der Farbenbaum<br />

Selbstbildnis als J.M. Rugendas<br />

beyond the turmoil of bodies and the earthly bustle that takes place<br />

with painting utensils and a naked Der Äquator (neuer Maler, neues Modell)<br />

The tree of color<br />

Self-portrait as J.M. Rugendas<br />

between birth and death. The painter inhabits this scene of the existential<br />

metamorphosis like a specter. He hovers, slightly removed, above the<br />

nonplussed. Living echoes of the Seite/page 64<br />

girl stand opposite one another, The equator (new painter, new model)<br />

Seite/page 82 – 83<br />

Seite/page 36<br />

real world, establishing a connection to the sphere of a starry surface<br />

tree demons, both of them draw<br />

that unfolds in the background. In <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>’s pictorial cosmos, this<br />

attention to a painting that lies on<br />

blue drapery with gold stars always refers to a religious image revered<br />

throughout Mexico: Our Lady of Guadalupe. This object of unlimited<br />

adoration has mesmerized pilgrims for hundreds of years, and has<br />

naturally played a central role as a tangible apparition in all missionary<br />

processes in both the past and the present. Her shimmering presence<br />

corresponds to the small, illuminated tree. Both appear to represent to<br />

<br />

<br />

Symbol der Malerei, erleuchtet diese konkrete Nacht<br />

ebenso wie jedes sonstige dramatische Geschehen:<br />

Wo er aufglüht, gibt es Hoffnung und Sinn über dem<br />

Getümmel der Leiber, dem irdischen Gezappel zwischen<br />

Geburt und Erlöschen. Der Maler wohnt dieser Szene<br />

der Daseinsmetamorphose wie ein Schemen bei, der<br />

leicht entrückt über dem Boden der Tatsachen schwebt<br />

und die Verbindung zur Sphäre einer bestirnten Plane<br />

herstellt, die sich im Hintergrund ausbreitet. Dieses blaue<br />

Tuch mit goldenen Sternen verweist im Bildkosmos von<br />

<strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> immer auf ein religiöses Kultbild ganz<br />

Mexikos, nämlich auf die Jungfrau von Guadalupe, die<br />

als Objekt einer unumschränkten Adoration seit Jahrhunderten<br />

Pilger in ihren Bann zieht und die selbstredend<br />

als fassbare Erscheinung bei allen Missionierungsprozessen<br />

eine zentrale Rolle spielte und spielt. Sie korrespondiert<br />

in ihrer schirmenden Präsenz dem illuminierten<br />

Bäumchen; beide stellen offenbar für <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong><br />

die metaphysischen Bezugspunkte dar, die ihm in allen<br />

Prozessen der Bildfindung Orientierung geben können<br />

und für seine künstlerische Positionierung unabdingbar<br />

sind. Ein drittes Beispiel für diese latente Befragung des<br />

eigenen Standorts als Künstler innerhalb der Traveler-<br />

Serie ist die Arbeit Äquator (Neuer Maler, neues Modell)<br />

von 2009, die wiederum auf eindringliche Weise den<br />

unvermittelten Zusammenprall indianischer und europäischer<br />

Kulturen vor Augen führt. In dschungelartigem<br />

Dickicht, in dem die Baumriesen anthropomorphe Züge<br />

tragen und als männliche und weibliche Wächterfiguren<br />

fungieren, richtet sich der Blick auf ein merkwürdiges<br />

Geschehen am Lagerfeuer: Im Vordergrund stehen sich<br />

ein nackter Knabe mit Malutensilien und ein nacktes<br />

Mädchen fragend gegenüber – beide ein lebendiges<br />

Echo der Baumdämonen – und weisen auf ein am Boden<br />

liegendes Bild, das in dieser Umgebung völlig<br />

unpassend wirkt. Es lässt sich unschwer als eine Arbeit<br />

Lucio Fontanas identifizieren, der in seiner berühmten<br />

Serie der Concetto spaziale die zweidimensionale Leinwand<br />

aufschlitzte und ihr so in seinem Verständnis<br />

eine neue dramatische Raumtiefe verlieh. Dieser Bote<br />

der europäischen Avantgarde der 1950er Jahre schlägt<br />

in die animistische Szenerie wie ein Meteorit aus einer<br />

the ground, entirely incongruous in these surroundings. It is easily<br />

identified as a work by Lucio Fontana, who in his famous Concetto<br />

spaziale series made slits in two-dimensional canvases, thus imbuing<br />

them with a new, dramatic spatial depth in his understanding. This<br />

herald of the European avant-garde of the nineteen-fifties abruptly<br />

enters this animistic scene like a meteorite from another world. The<br />

calm that reigns in the background of the painting, with the drunk and<br />

pot-bellied white settler and sleeping Indios, is not at all disrupted by it,<br />

however. <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong> must have felt something like this when he<br />

absorbed the canon of modernity, of the avant-gardes, and of post -<br />

mod ernism while he lived an everyday life that was virtually immune<br />

to such sophisms. The apparent incompatibility of disparate approaches<br />

to the world: this central theme of his work is to be found in programmatic<br />

formulations here, and becomes a leitmotif that runs through the<br />

polarities of that which is one’s own and that which is foreign, and of<br />

that which is familiar and that which is threateningly ’Other.’

42<br />

” Brief an Humboldt<br />

Letter for Humboldt<br />

2009<br />

Oil on linen, 240 x 320 cm<br />

Collection Heinz J. Angerlehner, Vienna, Austria

50<br />

” Traum und Tod Egertons<br />

Death and dream of Egerton<br />

2009<br />

Oil on linen, 240 x 320 cm<br />

Murderme Collection

58 59<br />

” Vinzenz und Paul in Amerika<br />

Vincent and Paul in America<br />

2004<br />

Oil on linen, 225 x 330 cm<br />

Collection of the artist, courtesy Galería<br />

Hilario Galguera

: Lowry<br />

Lowry<br />

2009<br />

Oil on linen, 150 x 190 cm<br />

Colección Jan Hintze, Ciudad de México<br />

75

Weitere Reiseabenteuer<br />

in Yucatán<br />

98 99

116 117<br />

: Der Warntraum des John L. Stephens<br />

Premonitory dream of John L. Stephens<br />

2011<br />

Oil on linen, 180 x 140 cm<br />

Murderme Collection

Erik Castillo<br />

BRIEFE<br />

weiter<br />

FERNE<br />

GEMÄLDE VON<br />

DANIEL LEZAMA, 2009-2011<br />

Mr. Catherwood ist gefallen, als die Sonne am höchsten<br />

stand. So zeigt ihn das Gemälde Der Sonnenstich des<br />

F. Catherwoods in Palenque. Jetzt ist er das erlöste Kind<br />

seiner selbst und sein Körper taucht in ein neues Land,<br />

wo sich sein Blick auf wieder neue Ufer richten kann.<br />

Hier ist die Todesart, die ihm das Schicksal auferlegt hat,<br />

nicht mehr das wirkliche Ertrinken in der Neuen Welt,<br />

sondern der letzte Nachhall zahlreicher Reinkarnationen.<br />

Diese Vision setzt sich fort in dem Bild Otros incidentes<br />

de viaje en Yucatán. Die Opferstätte im Hintergrund des<br />

Gemäldes zeigt die Anbetung des Himmels (Itzamná,<br />

das »Haus der Iguanas« nach den Maya), einen Kult der<br />

Eingeborenen, der mit Sicherheit eine monströse Form<br />

der Opferung einschloss. Inzwischen scheint sich Mr.<br />

Stephens damit zu beschäftigen, die reichen Gaben der<br />

Natur und die Anbetung der Raubvögel im dynamischen Flug ihres<br />

Liebesspiels rings um den Opferpfahl festzuhalten. In diesem Kult verehren<br />

die Eingeborenen den Flug des Adlers, der ihnen die Furcht vor<br />

der Mutter aller Schlangen während eines Augenblicks schwebender<br />

Vereinigung nehmen wird. Doch dieses Gefühl leidenschaftlicher<br />

Liebe, das die ganze Szene in eine ekstatische Aura taucht, ist mehr als<br />

eine individuelle Erfüllung des Begehrens; es handelt sich auch um eine<br />

erotisch aufgeladene kollektive Vereinigung, ähnlich wie sie sich Herbert<br />

Marcuse bei der Symbiose von libidinöser Phantasie und ungehemmter<br />

Sublimierung in einer technisch fortgeschrittenen Gesellschaft wünschte.<br />

Die Bestückung von Mr. Catherwoods Penis mit einer Pfauenfeder –<br />

in Wirklichkeit ein baho, der Federstock, den die Eingeborenen als<br />

rituellen Gebetsvermittler verwenden – lässt den Reisenden seinen<br />

Status verlieren und integriert ihn in eine Gesellschaft am anderen<br />

Ende der Welt. Der Iguana, der in einem doppelten Bild zu beiden<br />

Seiten des Gemäldes rechts hinein- und links wieder herausschlüpft<br />

– oh ja, wir sprechen hier von einem Gemälde – könnte durchaus<br />

den rhythmischen zyklischen Ablauf der Zeit symbolisieren, der durch<br />

diese in Trance befindlichen Nomaden in Bewegung gesetzt wird.<br />

Denn die Eingeborenenvölker glaubten an eine regelmäßige Abfolge<br />

Ride the snake<br />

To the lake<br />

The ancient lake, baby<br />

The snake is long<br />

Seven miles<br />

Ride the snake<br />

He’s old<br />

And his skin is cold<br />

The West is the best<br />

Get here and we’ll do the rest<br />

The blue bus<br />

Is calling us<br />

Driver, where are you taking us?<br />

Father<br />

Yes, son?<br />

I want to kill you<br />

Mother, I want to…<br />

The Doors, The End.<br />

LETTERS FROM AN<br />

UNFATHOMABLE DISTANCE.<br />

PAINTINGS BY<br />

DANIEL LEZAMA, 2009-2011<br />

Erik Castillo<br />

Mr. Catherwood has fallen at high noon. He is now<br />

the redeemed child of himself, his body sinking in a<br />

new land from which his vision can grow once again;<br />

but this manner of death that destiny has brought<br />

him (no longer his actual drowning in Terranova) is<br />

the final echo of many reincarnations. The adoration<br />

of the heavens (Itzamná, »The House of Iguanas«<br />

of Mayan lore) practiced by the native peoples who<br />

are the backdrop of this vision, certainly involved a<br />

monstruous form of sacrality: the intuition of such<br />

plenitude is only possible if each and every day is<br />

accepted as an immaculate era in itself. Meanwhile,<br />

Mr. Stephens seems to be engrossed in a form of<br />

non-textual writing, involving the reception and<br />

amassment of the offerings of abundant life and<br />

the consecration of the fury of winged lovers: they<br />

worship the flight of the eagle, that will conceal the<br />

fear created by the mother of all serpents during a<br />

moment of weightless communion. Yet, this ardour<br />

of love which gives an essential patina to the entire<br />

von Zerstörung und Wiedererschaffung der Welt, die sich innerhalb eines bestimmten Zeitzyklus, nicht im linearen Zeitablauf,<br />

abspielte, und die eine Zeit der Erlösung und des Vergessens mit sich brachte. Man hielt also die Transformation des Bestehenden,<br />

nicht die Kreation aus dem Nichts, für den Ursprung der Dinge und des Lebens. Nach einem ersten Blick auf das Gemälde<br />

beschwören all die Praktiken, die hier vor Augen geführt werden, im Geist des Betrachters die reichen Möglichkeiten einer<br />

offenen, nicht allein materiellen, Lebenskraft herauf: die mögliche Akzeptanz der verschlungenen Wege des Schicksals.<br />

Die eigenartig simultane Inszenierung der Ereignisse, die sich dem Blick des Betrachters in <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>s Weitere Reiseerlebnisse<br />

in Yucatán bieten, entfalten die Rhetorik einer syntaktischen Erzählung – eine Gattung der Bildgestaltung, die in der Malerei der<br />

Renaissance üblich war (vgl. Boticellis Begebenheiten aus dem Leben des Mose in der Sixtina oder Die Befreiung Petri aus dem<br />

Kerker von Raffael in der Stanza di Eliodoro im Vatikan). In diesen Darstellungen werden<br />

die Hauptpersonen in verschiedenen Momenten oder Phasen ihres Lebens und<br />

in verschiedenen Tätigkeiten an ein und demselben Schauplatz wiedergegeben. Hier<br />

sehen wir die Forscher Catherwood und Stephens jeweils in doppelter Erscheinung<br />

in ein und derselben tropischen Landschaft. Gehalt und Verlauf ihrer Tätigkeiten können<br />

nur im Kontext der Ereignisse verstanden werden, die nach unserer Meinung an<br />

einem geheiligten Schauplatz der Weihe und Initiation in der heidnischen Welt<br />

stattfanden, an einem Ort ähnlich dem Mysterientempel Telesterion von Eleusis oder<br />

dem Apollotempel in Delphi. Leben und Tod des englischen Zeichners und eine Episode<br />

aus den Abenteuern des nordamerikanischen Schriftstellers – die beide ab 1839<br />

Mexiko bereisten – sind von <strong>Lezama</strong> in ein und dasselbe malerische Kontinuum von<br />

Zeit und Raum gesetzt worden.<br />

Das panoramische Szenario dieser Allegorie ist <strong>Lezama</strong>s Paraphrase einer berühmten<br />

Ansicht, die Catherwood für sein Album mit Zeichnungen der Mayaruinen festgehalten<br />

hatte. Die gesamte Atmosphäre der Szene vermittelt den Eindruck eines außergewöhnlichen<br />

Geschehens und das Gefühl absurden Tuns: die Wahl der Ruinen von<br />

Uxmal als Bühne beschränkt sich nicht nur auf die Beschreibung eines Mayatempels,<br />

sondern bietet <strong>Lezama</strong> die Möglichkeit, seine Phantasie mit all den indianischen<br />

Ruinen und Bauwerken spielen zu lassen, die uns entweder von der ethnologischen<br />

oder der archäologischen Forschung überliefert wurden. Er tut dies mit Vorliebe<br />

dann, wenn seine Protagonisten durch die Kraft visionärer Spiritualität tief bewegt<br />

worden sind oder ihr Leben sich durch den Einfluss des Sexualtriebs zutiefst veränderte,<br />

ja, eine Umwälzung erfuhr, in beiden Fällen eine Folge der Notwendigkeit zur Erneuerung.<br />

Auch repräsentieren die Eingeborenen um die beiden berühmten Reisenden<br />

in dem Gemälde, die mit ihnen interagieren, keineswegs eine bestimmte Ethnie, sie<br />

könnten Angehörige irgendeines die Jahrhunderte überdauernden Stammes oder<br />

Dorfes sein. Darüber hinaus ist es klar, dass für die Eingeborenen in dem Gemälde<br />

die Ruinen der Bauwerke Strukturen einer vergangenen Epoche verkörpern: sie sind<br />

selbst Reisende, durch die Schicksalsschläge ihrer Geschichte in die Gegenwart geworfen,<br />

und Wächter eines Prinzips, das weit über die ursprüngliche Bedeutung der Tempel<br />

und der Religionen hinausweist, die von einer gesellschaftlich hierarchisch aufgebauten<br />

Pyramide getragen werden.<br />

Die ethnografische Aura dieses Gemäldes, das wie in einer Art Chronik die Kräfte<br />

des kollektiven Unbewussten vor Augen führt, erinnert an den beeindruckenden<br />

Reise bericht, den der deutsche Forscher Aby Warburg, der Begründer der ikonologischen<br />

Forschung, nach seinem Aufenthalt in der Psychiatrischen Klinik Bellevue<br />

scene, is more than the individual fulfillment of the tapestry of desire;<br />

it is also about a collective reconcilement laden with Eros, not unlike the<br />

one Herbert Marcuse wished for in the symbiosis of libidinal fantasy<br />

and non-repressive sublimation in a technically advanced society. The<br />

pro pitiation of Mr. Catherwood’s penis with a peacock feather –an actual<br />

baho, the feather duster used by North American natives as ritual gobetween–<br />

makes the traveler lose his standing as such, and guides him<br />

to his integration in a socius located the antipodes of his own world.<br />

The iguana that comes and goes through the hat of the explorer in the<br />

double image at both sides of the painting oh, yes, we are talking about<br />

a painting here might well embody the rythmic, circular mode of time<br />

set in motion by these nomads in a trance, a time involving salvation and<br />

oblivion. At first take, all the practices described in this canvas evoke in<br />

the imagination of the audience a wealth of possibilites of vital aperture,<br />

amounting to an acceptance of the meandering chords of the song of fate.<br />

The strangely simultaneous staging of events in <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>’s Other<br />

incidents of travel in Yucatan, involves the rhetoric of syntactical narrative,<br />

a mode of iconographic arrangement common in Renaissance painting<br />

(i.e., Boticelli’s Tribulations of Moses in the Sistine Chapel, or the Liberation<br />

of St. Peter by Rafael in the Vatican Stanza Eliodoro) where the main<br />

characters are depicted in various moments of an action in the same<br />

visual forum: here, explorers Catherwood and Stephens are depicted twice<br />

each in the same tropical landscape. The script of their actions can only<br />

be understood in the context of the events that we believe took place in<br />

the theaters of consecration and initiation of pagan antiquity, such as<br />

the Thelesterion of Eleusis or the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. The life and<br />

death of the English draughtsman and an episode of the adventures of<br />

the North American writer –who began their travels in Mexico in 1839– are<br />

placed by the artist in a same painterly continuum of time and space.<br />

The panoramic view that provides the scenario for this allegory is <strong>Lezama</strong>’s<br />

paraphrase of a famous view drawn from life by Catherwood for his<br />

album of Mayan ruins. And the overall mood of the scene is precisely<br />

that of an extraordinary event that begets a sensation of productive<br />

absurdity: the election of the ruins of Uxmal as a stage not only proposes<br />

the description of one Mayan temple, but offers <strong>Lezama</strong> the opportunity<br />

to fantasize with all the native ruins and dwellings consigned by either<br />

ethnologic or archeological research, as long as the characters involved<br />

have been deeply moved by the strength of spiritual reverie or their life<br />

transfigured by sexual impulse, in both cases urged by the need of<br />

renewal. Neither are the natives who surround, and interact with, both<br />

famous travelers in the canvas merely a representation of a specific cultural<br />

background they could pertain to any tribe or community sidelined by<br />

passing centuries. It is very clear that even for the native characters, the<br />

ruins of past monuments are structures from a previous era they are<br />

themselves travelers brought to the present day by the vicissitudes of<br />

history, and guardians of a meaning that trascends the original purpose<br />

of temples and religions supported on a pyramid of social hierarchy.<br />

131

Die verschwenderische Mutter<br />

The prodigal mother<br />

2008<br />

Oil on linen, 640 x 240 cm<br />

The Hermes Trust Collection, New York

: <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>:<br />

Der Traum vom 16. September<br />

The dream of September 16th<br />

2001<br />

Oil on linen, 145 x 195 cm<br />

Private collection, Monterrey, Mexico<br />

157

Pose erinnert an ein Bild von Mantegna, das von Caravaggio neu gemalt wurde. Die<br />

exponierten Genitalien der Leiche und des Jungen befinden sich auf derselben<br />

Achse, fast in Opposition (oder komplementär) zueinander. Der Titel des Gemäldes<br />

mit seinem Reigen von semantisch kontrastierenden Begriffen: Tod / Tiger, Tiger /<br />

Heiliger, Julia / Tod bezieht sich auf ein tatsächliches Ereignis und der Künstler<br />

spricht ausführlich über den Veränderungsprozess, der im kollektiven Gedächtnis<br />

des Volkes die wahre Erinnerung an diesen Fall überlagert hat: »Der Tiger von Santa<br />

Julia war ein bekannter und blutdürstiger Bandit der postrevolutionären Ära um 1920<br />

in Mexico City. Erst nachdem die Polizei in einer langwierigen Operation das Domizil<br />

seiner Geliebten ausspioniert und umstellt und gewartet hatte, bis er die Nacht dort<br />

verbrachte, war es möglich, seiner habhaft zu werden. Als er in der Morgendämmerung<br />

herauskam, um im Patio seinen Darm zu entleeren, wurde er am Boden hockend festgenommen,<br />

während seine Waffe neben ihm lag. Einige Zeit später wurde er nach<br />

einem Gerichtsverfahren exekutiert und sein Schädel im Naturwissenschaftlichen<br />

Museum der Nationalen Universität ausgestellt. Das Gemälde illustriert perfekt Mircea<br />

Eliades Theorie über die Entstehung von Mythen: Die Menschen kennen die wahre<br />

Geschichte, glauben aber, dass der Mann beim Kacken erschossen wurde. In der<br />

kollektiven Erinnerung wird die prosaische Geschichte durch das spektakuläre Bild<br />

überlagert und niemand glaubt mehr an die wirkliche und dokumentierte Version.<br />

Ich gab der Geschichte eine weitere Wendung. Der Tiger war der letzte Bandit des<br />

›Wilden Mexiko‹, und seine Hinrichtung stand am Beginn des Weges zu einer modernen<br />

City, die frei von schießwütigen Revolverhelden war. In meinem Bild wird er mit<br />

heruntergelassener Hose von seinem Teenagersohn getötet, den darauf die Konkubine<br />

des Vaters liebevoll wäscht. Er hat den<br />

Vater getötet, um seinen Platz einzunehmen,<br />

eine Metapher für die gewalttätige<br />

Geburt des modernen Mexiko.«<br />

Die von <strong>Lezama</strong> im magischen Kreis der<br />

vier Personen dieses Bildes heraufbeschwo<br />

rene Spannung ist so intensiv, dass<br />

man kaum beachtet, dass an den Rändern<br />

der Darstellung auch ein Publikum gezeigt<br />

wird: einem Chor ähnlich, wie in vielen<br />

Szenen Tiepolos oder sogar in Manets<br />

Die Erschießung Kaiser Maximilians von<br />

Mexiko, einem Bild, das wiederum von<br />

Goyas Die Erschießung der Aufständischen<br />

am 3. Mai 1808 in Madrid inspiriert worden<br />

war. Die ästhetische und symbolische Rolle<br />

dieses Chores ist es, Zeuge des vertrauten<br />

und zugleich geheimen Ereignisses<br />

zu sein. In Der Besuch, 2002, und<br />

bereits in Das blaue Zimmer, 2001, haben<br />

wir es zwar mit einem privaten Ritual zu<br />

tun, das sich vor dem Hintergrund des<br />

: <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>:<br />

Der Tod des Tigers von Santa Julia<br />

The death of the Santa Julia Tiger<br />

2000<br />

Oil on canvas, 270 x 195 cm<br />

Colección INBA, Acervo del Museo de Arte Moderno,<br />

Ciudad de México<br />

In his own words: »The Santa Julia Tiger was a well-known and bloodthirsty bandit of<br />

the post-Revolutionary era (ca. 1920) in Mexico City. The police operation that led to his<br />

capture involved spying on and surrounding the home of his girlfriend, until he spent the<br />

night there. When he came out at dawn to defecate in the patio he was captured, squatting<br />

down and with his weapon on the ground next to him. Some time later, he was executed<br />

after a judicial process, and his skull is on display at the Museum of Sciences of the National<br />

University. The interesting part is that it illustrates perfectly the theory of creation of myth<br />

by Mircea Eliade: people know his legendary story, but they believe he was shot to death<br />

while defecating. In the collective imaginary, the prosaic story is overshadowed by the<br />

specta cular image, and no one believes now in the real and documented version. I gave the<br />

story a further twist. The Tiger was the last bandit of the »Wild Mexico« and his execution<br />

inaugurated the modern city, free of trigger-happy gunmen. In my image, his teenage son<br />

kills him with his pants down and is then lovingly washed by the concubine. He has killed<br />

him to take his place, a metaphor of the birth of modern Mexico.«<br />

The tension recreated by <strong>Lezama</strong> in the magic circle of the four cha racters in this picture<br />

is so intense, as in many other cases, that it is easy to forget that there is also an audience<br />

depicted in the fringes of this re presentation: a choir, so to speak (as in many scenes by<br />

Tiepolo, or even in The execution of Maximilian of Manet, in turn inspired by Goya’s 5th of<br />

May), whose aesthetic and symbolic role is essential: to bear witness of the particular,<br />

familiar and secret event (or even its official version), in order to confer the historic and<br />

mythological transcendence that makes it part of a tradition and a culture (as Jorge Luis<br />

Borges well knew). In The visit, 2002, and already in The blue room, 2001, we are dealing<br />

with a private ritual, against the background of the fluorescent blue light of a motel (as in<br />

Faun and witch, Fright night, and The new discovery of Pulque, all three from 2002 as<br />

well, and maybe in The triumph of racial integration, and The drunks, both from 2001,<br />

or in The family bath from 1999), yet there are almost always witnesses –an imperative for<br />

every initiation and every sacrifice–. We have already seen that in <strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>’s world,<br />

at once imaginary and hyperreal, this role is parallel and coexistent with the one played<br />

by a woman that is a somewhat aggressive initiator herself, not unlike an avatar of the<br />

muse-sorceress that is determined to carry along to its conclusion (but not without infinite<br />

tests) the poetic destiny of the artist (this is abundantly clear in, for example, The painting<br />

Class, 2002, The dream of Juan Diego and Allegory of Guelatao, both from 2004, The plain<br />

in flames, 2005, and The sowing, 2005). Likewise, the ‘adolescent-painter’ i.e., he whom is<br />

in a quest for, or is a prisoner of, his artistic education is also present in the aforementioned<br />

<br />

<strong>Daniel</strong> <strong>Lezama</strong>:<br />

Der Triumph der Verschmelzung der Rassen<br />

The triumph of the amalgamation of the races<br />

2001<br />

Oil on linen, 225 x 225 cm<br />

Collection of the artist,<br />

courtesy Galería Hilario Galguera<br />

<br />

Édouard Manet:<br />

Die Erschießung Kaiser Maximilians von<br />

Mexico<br />

The execution of emperor Maximilian<br />

1868 – 69<br />

Oil on canvas, 252 x 305 cm<br />

Kunsthalle Mannheim<br />

165

172 173<br />

Die große mexikanische Nacht<br />

The big Mexican night<br />

2005<br />

Oil on linen, 240 x 300 cm<br />

Colección Günther Rohde, Atlixco, Puebla

: Der blinde Adler<br />

Blind eagle<br />

2008<br />

Oil on linen, 170 x 130 cm<br />

Private Collection<br />

Monterrey, Mexico<br />

Die Verkündigung<br />

Annunciation<br />

2008<br />

Oil on linen, 170 x 130 cm<br />

Colección Jan Hintze,<br />

Ciudad de México

198 199