Superfast Broadband - Evidence - Parliament

Superfast Broadband - Evidence - Parliament

Superfast Broadband - Evidence - Parliament

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

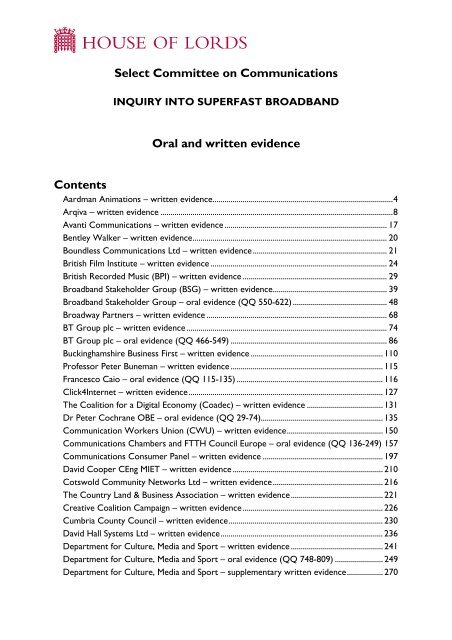

Select Committee on Communications<br />

INQUIRY INTO SUPERFAST BROADBAND<br />

Oral and written evidence<br />

Contents<br />

Aardman Animations – written evidence .......................................................................................... 4<br />

Arqiva – written evidence .................................................................................................................... 8<br />

Avanti Communications – written evidence ................................................................................. 17<br />

Bentley Walker – written evidence ................................................................................................. 20<br />

Boundless Communications Ltd – written evidence ................................................................... 21<br />

British Film Institute – written evidence ........................................................................................ 24<br />

British Recorded Music (BPI) – written evidence ........................................................................ 29<br />

<strong>Broadband</strong> Stakeholder Group (BSG) – written evidence ......................................................... 39<br />

<strong>Broadband</strong> Stakeholder Group – oral evidence (QQ 550-622) ............................................... 48<br />

Broadway Partners – written evidence .......................................................................................... 68<br />

BT Group plc – written evidence .................................................................................................... 74<br />

BT Group plc – oral evidence (QQ 466-549) .............................................................................. 86<br />

Buckinghamshire Business First – written evidence .................................................................. 110<br />

Professor Peter Buneman – written evidence ............................................................................ 115<br />

Francesco Caio – oral evidence (QQ 115-135) ......................................................................... 116<br />

Click4Internet – written evidence ................................................................................................. 127<br />

The Coalition for a Digital Economy (Coadec) – written evidence ...................................... 131<br />

Dr Peter Cochrane OBE – oral evidence (QQ 29-74)............................................................. 135<br />

Communication Workers Union (CWU) – written evidence ................................................ 150<br />

Communications Chambers and FTTH Council Europe – oral evidence (QQ 136-249) 157<br />

Communications Consumer Panel – written evidence ............................................................ 197<br />

David Cooper CEng MIET – written evidence ........................................................................... 210<br />

Cotswold Community Networks Ltd – written evidence ....................................................... 216<br />

The Country Land & Business Association – written evidence .............................................. 221<br />

Creative Coalition Campaign – written evidence ...................................................................... 226<br />

Cumbria County Council – written evidence ............................................................................. 230<br />

David Hall Systems Ltd – written evidence ................................................................................. 236<br />

Department for Culture, Media and Sport – written evidence .............................................. 241<br />

Department for Culture, Media and Sport – oral evidence (QQ 748-809) ........................ 249<br />

Department for Culture, Media and Sport – supplementary written evidence .................. 270

Digital Outreach – written evidence ............................................................................................. 271<br />

Directors UK – written evidence .................................................................................................. 275<br />

Everything Everywhere – written evidence ................................................................................. 283<br />

Everything Everywhere – supplementary written evidence ..................................................... 286<br />

Federation of Communications Services – written evidence .................................................. 288<br />

Federation of Small Businesses – written evidence ................................................................... 292<br />

Fibre GarDen (the Garsdale & Dentdale Community Fibre <strong>Broadband</strong> Initiative) – written<br />

evidence ............................................................................................................................................... 296<br />

Film Distributors Association – written evidence ..................................................................... 302<br />

Forum of Private Business – written evidence ............................................................................ 306<br />

FTTH Council Europe – written evidence .................................................................................. 307<br />

FTTH Council Europe and Communications Chambers – oral evidence (QQ 136-249) 313<br />

Fujitsu – written evidence................................................................................................................ 314<br />

Geo Networks Limited – written evidence ................................................................................ 316<br />

Dr Tehmina Goskar – written evidence ...................................................................................... 319<br />

GreySky Consulting – written evidence ....................................................................................... 321<br />

Peter Griffin - written evidence ..................................................................................................... 326<br />

Groupe Intellex – written evidence .............................................................................................. 330<br />

Mr John Howkins – written evidence ........................................................................................... 334<br />

Huawei – written evidence ............................................................................................................. 335<br />

The Independent Networks Cooperative Association (INCA) – written evidence .......... 377<br />

KCOM Group PLC – written evidence ....................................................................................... 383<br />

Robert Kenny – written evidence ................................................................................................. 387<br />

Leire Exchange <strong>Broadband</strong> Action Group – written evidence ............................................... 394<br />

The Liberal Democrats Action for Land Taxation and Economic Reform (ALTER) –<br />

written evidence ................................................................................................................................ 396<br />

Suvi Lindén – oral evidence (QQ 1-28) ........................................................................................ 397<br />

John McDonald – written evidence ............................................................................................... 410<br />

Miles Mandelson – written evidence ............................................................................................. 415<br />

Miles Mandelson and Rory Stewart MP – oral evidence (QQ 430-465) .............................. 426<br />

Dr Christopher T Marsden – written evidence ......................................................................... 444<br />

Microsoft – written evidence .......................................................................................................... 456<br />

Microsoft – oral evidence (QQ 623-649) .................................................................................... 463<br />

Microspec – written evidence ........................................................................................................ 474<br />

Dr Catherine A. Middleton – written evidence ......................................................................... 476<br />

Middleton Tyas Parish Council – written evidence ................................................................... 481<br />

Milton Keynes Council – written evidence ................................................................................. 482<br />

Tom Morris – written evidence ..................................................................................................... 485<br />

Motion Picture Association – written evidence ......................................................................... 490<br />

The National Education Network – written evidence .............................................................. 494<br />

NG Events Ltd – written evidence ................................................................................................ 510<br />

2

NICC Ethernet Working Group – written evidence ................................................................ 514<br />

Northern Fells <strong>Broadband</strong> (Cumbria) - written evidence ........................................................ 518<br />

Objective Designers – written evidence ...................................................................................... 522<br />

Objective Designers – oral evidence (QQ 75-114) ................................................................... 526<br />

Ofcom – written evidence ............................................................................................................... 543<br />

Ofcom – oral evidence (QQ 650-747) ......................................................................................... 556<br />

Chi Onwurah MP – oral evidence (QQ 250-282) ..................................................................... 580<br />

Chi Onwurah MP – supplementary written evidence ............................................................... 591<br />

<strong>Parliament</strong>ary Office of Science and Technology (POST) – written evidence .................... 594<br />

John Peart – written evidence ........................................................................................................ 598<br />

Mike Phillips – written evidence ..................................................................................................... 600<br />

Simon Pike – written evidence ....................................................................................................... 602<br />

Pitchup.com – written evidence ..................................................................................................... 608<br />

Prospect – written evidence ........................................................................................................... 610<br />

The Publishers Association – written evidence .......................................................................... 621<br />

Steve Robertson – oral evidence (QQ 320-353) ....................................................................... 625<br />

Les Savill – written evidence ........................................................................................................... 639<br />

South West Internet CIC – written evidence ............................................................................ 640<br />

SSE plc – written evidence............................................................................................................... 643<br />

SSE plc - oral evidence (QQ 379-407) .......................................................................................... 649<br />

SSE plc – supplementary written evidence .................................................................................. 660<br />

Rory Stewart MP and Miles Mandelson – oral evidence (QQ 430-465) .............................. 670<br />

Sunderland Software City – written evidence ............................................................................ 671<br />

TalkTalk Group – written evidence .............................................................................................. 673<br />

TalkTalk Group – oral evidence (QQ 408-429)......................................................................... 679<br />

TalkTalk Group – supplementary written evidence .................................................................. 688<br />

TalkTalk Group – further supplementary written evidence .................................................... 690<br />

Taxpayers’ Alliance – written evidence ........................................................................................ 693<br />

Three – written evidence ................................................................................................................ 698<br />

Three and Vodafone – oral evidence (QQ 354-378) ................................................................ 702<br />

UCL Centre for Digital Humanities – written evidence ........................................................... 715<br />

Upper Deverills <strong>Broadband</strong> Action Group (BAG) – written evidence ................................. 717<br />

Virgin Media – written evidence .................................................................................................... 720<br />

Virgin Media – oral evidence (QQ 283-319) ............................................................................... 729<br />

Vodafone – written evidence .......................................................................................................... 744<br />

Vodafone and Three – oral evidence (QQ 354-378) ................................................................ 748<br />

Vtesse Networks – written evidence ........................................................................................... 749<br />

Wispa Limited – written evidence ................................................................................................. 750<br />

3

Aardman Animations – written evidence<br />

Aardman Animations – written evidence<br />

Summary<br />

1. I am making this submission as Head of IT for Aardman Animations based in Bristol.<br />

2. Aardman are a typical creative company living in the digital age. We are in the happy<br />

position of needing to push material out for many different types of clients and this<br />

gives us a great deal of industrial experience. Most companies don’t cover quite as<br />

many bases as we do, although their data needs may actually be higher. So what’s<br />

good for us will definitely be good for the industry as a whole.<br />

3. The submission is based around comments on the list of questions in the ‘Will<br />

superfast broadband meet the needs of our “bandwidth hungry” nation?’ call for<br />

evidence document; the original question is prefixed with (Q) and is in red text.<br />

Response<br />

4. (Q) What is being done to prevent a greater digital divide occurring between people who<br />

can access superfast broadband and people in areas where the roll-out of superfast<br />

broadband may not be commercially attractive? How does the UK communications market<br />

vary regionally and what is the best way to connect the areas that the market alone cannot<br />

reach? Is a universal service obligation necessary to avoid widening the digital divide?<br />

5. A universal service obligation is needed, this would expand the ability of companies<br />

to utilise home working in particular which would have a significant green advantage<br />

whilst reducing company costs, many workers commute from poorly serviced areas,<br />

so it is these areas that could see serious advantages from improved broadband, it<br />

would also enable people with commitments to family at home or disabled people to<br />

be able to engage with the workplace from a home office opening up work<br />

opportunities that are difficult currently for many people.<br />

We need to ensure that rural communities are not penalised due to the far greater<br />

cost of rolling out the infrastructure for remote communities and seeing<br />

disproportionate charges etc. for the service.<br />

(Q) Will the Government’s targets be met and are they ambitious enough? What speed of<br />

broadband do we need and what drives demand for superfast broadband?<br />

6. History of government projects tends to show that targets won’t be met and will fall<br />

short of what is expects, whilst costing far more than originally projected.<br />

7. The digital world is moving forward at a huge pace, with broadband there is a focus<br />

on the download speed but never on the upload speed or contention, to succeed in a<br />

4

Aardman Animations – written evidence<br />

digital era we need to see a much greater upload speed and low contention, for<br />

every download there has to have been an upload that is actually the important bit if<br />

you are producing content.<br />

8. In my opinion we need to see faster download but more importantly we need to see<br />

upload speeds matching download speeds or it will not be of any use to people<br />

needing to work in the digital space, contention needs to be lower to give a more<br />

predictable performance.<br />

As an example, a typical production size on completion is 624 Gigabytes (Shaun the<br />

Sheep as an example) with the best business broadband speeds this would take about<br />

6 days to upload and over a day to download… assuming you see no service<br />

interruption.<br />

9. I would say we need synchronous speeds in excess of 100Mb to ensure we can be<br />

competitive in the large content production and distribution space, content is going<br />

to continue to increase in size and complexity (>high def, 3d etc.) so bandwidth will<br />

need to be regularly reviewed and improved.<br />

10. (Q) In fact, are there other targets the Government should set; are there other indicators<br />

which should be used to monitor the health of the digital economy? What communications<br />

infrastructure does the UK ultimately need to remain competitive and meet consumer<br />

demand over the next 20 years?<br />

11. You need to ensure that the back end infrastructure can cope with any increase of<br />

consumer broadband speeds; if this is neglected we will see contention at the backend<br />

that will negate any benefits at the client side. This will present itself as erratic<br />

performance, which is not good for business working in this space.<br />

12. We need low contention high speed (>100Mb) synchronous bandwidth to remain<br />

competitive.<br />

13. A number of possible metrics could be used here which could include the uptake of<br />

broadband based digital media technologies such as TV and Film services, the uptake<br />

of Internet TV’s and growth of smartphone and tablet sales.<br />

14. (Q) How will individuals and companies use cloud services for distributed storage and<br />

computation? What network properties are required to enable efficient provision and use of<br />

such services?<br />

15. Cloud Services are being pushed heavily by the cloud companies, but this sort of<br />

service is completely reliant on a fast upload speed, which current high speed<br />

broadband just does not deliver, and this is not understood by many SME’s. We<br />

5

Aardman Animations – written evidence<br />

regularly see data changes internally of greater than 1 Terabyte, such data flows<br />

would need serious uplink speeds to ensure those changes successfully reached a<br />

backup/archive containment in any business acceptable time frame.<br />

16. What also needs to be considered with cloud services is resilience of your network;<br />

this is something that is also not properly understood. If a company moves key<br />

business activity into the cloud they need to be very sure they have a faster and fully<br />

resilient network link to the internet than they had previously , because if they lose<br />

any of these links the business is at risk of not being able to function until the link is<br />

restored. Network links are currently too expensive to make this viable to many<br />

SME’s and hence I suspect they just take the risk of non-resilient slower links putting<br />

their business at risk of failure.<br />

17. (Q) To what extent will the advent of superfast broadband affect the ways in which people<br />

view, listen to and use media content? Will the broadband networks have the capacity to<br />

meet demand for new media services such as interactive TV, HD TV and 3D content? How<br />

will superfast broadband change e-commerce and the provision of Government services?<br />

18. Without doubt broadband is going to increasingly be used for all types of high<br />

bandwidth content as we have seen in recent years. Nearly all consumption of<br />

content in the home will be via broadband in coming years. Unless the infrastructure<br />

is dramatically improved it will be a miserable experience for many users and<br />

businesses.<br />

19. These technologies are already being pushed at national level but in reality it is only<br />

achievable in useable form in cities and large towns. Attention also has to be paid to<br />

back end infrastructure as that risks being the bottleneck as more and more of these<br />

client services come online. Has anyone computed the real likely costs of the<br />

necessary infrastructure and the impact these costs may have on SME overhead, or<br />

indeed Government services?<br />

20. (Q) Will the UK's infrastructure provide effective, affordable access to the 'internet of things',<br />

and what new opportunities could this enable?<br />

21. This will only happen if significant investment is made and in all areas of the country.<br />

If done correctly it will empower small businesses to spring up outside of the big<br />

cities, reduce the need to travel to work and give opportunities to people who find<br />

mobility for work difficult. It could also revolutionize communications by enabling<br />

useable personal video conferencing capabilities etc. See above regarding costs.<br />

22. (Q) What role could or should the different methods of delivery play in ensuring the<br />

superfast broadband network is fit for purpose and is as widely available as possible? How<br />

6

Aardman Animations – written evidence<br />

does the expected demand for superfast broadband influence investment to enhance the<br />

capacity of the broadband network?<br />

23. Multiple delivery methods definitely need to be part of the plan to ensure a broad<br />

reach for the service in all areas.<br />

24. If investment does not run ahead of demand we will see an appalling service that<br />

hinders rather than helps the consumer.<br />

25. (Q) What impact will enhanced broadband provision have on the media and creative<br />

industries in the UK, not least in light of the increased danger of online piracy? What is the<br />

role of the Government in assuring internet security, and how should intellectual property<br />

(IP) best be protected, taking into account the benefits of openness and security?<br />

26. Enhanced broadband opens opportunities for media and creative companies to reach<br />

many more consumers in new and innovative ways. This does of course increase the<br />

risk of piracy and hacking etc. so all companies need to pay much more attention to<br />

security and data protection.<br />

27. The government needs to put more funding and greater priority on internet security,<br />

making companies far more aware of the risks they encounter when working in<br />

cyber-space, possibly using legislation to ensure this happens, as in the finance<br />

industries etc.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

28. In my humble opinion the High speed broadband that is currently being proposed will<br />

fall short of the requirements needed for a competitive digital economy. We need to<br />

be looking at low contention synchronous bandwidth with speeds of 100Mb<br />

minimum and 1Gb requirements will not be many years behind this.<br />

29. We also need to improve the delivery times for high speed infrastructure as this can<br />

be appalling and very expensive; even in supposedly highly connected cities. Councils<br />

need to work closer with the data companies to smooth the way here.<br />

4 March 2012<br />

7

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

Summary of Key Points and Recommendations:<br />

• Arqiva welcomes the opportunity to respond to the House of Lords Communications<br />

Committee’s timely new Inquiry into The Government’s <strong>Superfast</strong> <strong>Broadband</strong> Strategy.<br />

• The Committee are quite right to begin this Inquiry by focusing on the risk of a ‘digital<br />

divide’. Arqiva strongly believes that the real gain for UK plc is to achieve universal<br />

access to broadband - not to push fibre to a little over 90% penetration and then stop.<br />

We believe there would be a considerable opportunity cost (both economically and<br />

socially) if, come 2015, consumers who already have access to broadband were “superserved”<br />

with fibre… while millions who currently have little, or no, broadband provision<br />

remain under-served, forgotten or left behind.<br />

• Arqiva strongly welcomes the £530 million of public investment in broadband being<br />

managed by DCMS. Yet, it appears that the current broadband procurements by the<br />

Devolved Bodies and Local Authorities in the English Counties will still leave some<br />

consumers without access to broadband by the Government’s target of 2015. The<br />

emphasis placed on making superfast broadband (essentially fibre) as widely available as<br />

possible is a laudable aim - but there are insufficient funds to offer superfast to all. Some<br />

funding must be targeted at other solutions for those who will not be offered fibre.<br />

• Only by investing in wireless/mobile broadband alongside fibre can we ensure that the<br />

final 6-8% or so of homes can also have access to a minimum 2 Mbps service.<br />

• Arqiva welcomes Ofcom recent revised proposal to increase the coverage obligation<br />

from 95% of the UK population to 98% in the auction of 4G licences. This is positive<br />

news – however, by setting a UK-wide obligation, rather than measuring this obligation<br />

by Nation separately, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland may not benefit<br />

equally.<br />

• Arqiva also strongly welcomes the initiative by the Chancellor of the Exchequer to invest<br />

£150 million in improving rural mobile phone coverage. Although principally envisaged to<br />

address mobile voice “not spots”, it would be a missed opportunity if this Mobile<br />

Infrastructure Project (MIP) failed to secure 4G mobile broadband for affected<br />

consumers, as a complement to the 4G coverage obligation, not least since many of<br />

them would have no reliable fixed line broadband alternative. To maximise the<br />

effectiveness with which the £150 million in invested, shared infrastructure with shared<br />

backhaul should be procured by BDUK.<br />

• An essential element of the UK’s digital communications infrastructure needs to be<br />

consideration of how far the UK has managed to deliver pervasive mobile broadband and<br />

Wi-Fi – including on the London Underground and major train lines where coverage is<br />

currently either non-existent or, at best, patchy. Given that Transport for London and<br />

Network Rail are both public sector bodies there is a clear role for Government in<br />

addressing this.<br />

8

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

About Arqiva<br />

Arqiva is a media infrastructure and technology company operating at the heart of the<br />

broadcast and mobile communications industry and at the forefront of network<br />

solutions and services in an increasingly digital world. Arqiva provides much of the<br />

infrastructure behind television, radio and wireless communications in the UK and has<br />

a growing presence in Ireland, mainland Europe and the USA.<br />

Arqiva is implementing UK Digital ‘Switch-Over’ from analogue television to Freeview<br />

– a huge logistical exercise which touches every <strong>Parliament</strong>ary constituency, requiring<br />

an investment by Arqiva of some £630m and which is successfully being delivered to<br />

time and budget.<br />

Arqiva is also founder member and Shareholder of Freeview (Arqiva broadcasts all six<br />

Freeview multiplexes and is the licensed operator of two of them) and was a key<br />

launch technology partner for Freesat. Arqiva is also the licensed operator of the<br />

Digital One national commercial DAB digital radio multiplex.<br />

Arqiva operates five international satellite teleports, over 70 other staffed locations,<br />

and around 9000 shared radio sites throughout the UK and Ireland including masts,<br />

towers and rooftops from under 30 to over 300 metres tall.<br />

In addition for broadcasters, media companies and corporate enterprises Arqiva<br />

provides end-to-end capability ranging from –<br />

• outside broadcasts (10 trucks including HD, used for such popular programmes<br />

as Question Time and Antiques Roadshow);<br />

• satellite newsgathering (30 international broadcast trucks);<br />

• 10 TV studios (including the National Lottery Live)<br />

• spectrum for Programme-Making & Special Events (PMSE) 1 ;<br />

• playout (capacity to play out over 70 channels including HD); to<br />

• satellite distribution (over 1200 services delivered).<br />

Elsewhere in the communications sector, the company supports cellular, wireless<br />

broadband, video, voice and data solutions for the mobile phone, public safety, public<br />

sector, public space and transport markets.<br />

Arqiva’s major customers include the BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Five, BSkyB, Classic FM, the<br />

four UK mobile operators, Metropolitan Police and the RNLI.<br />

Arqiva welcomes the opportunity to respond to the House of Lords Communications<br />

Committee’s new Inquiry into The Government’s <strong>Superfast</strong> <strong>Broadband</strong> Strategy.<br />

1<br />

Such as the wireless cameras operated by the BBC and Sky News, and the radio microphones used in virtually all<br />

television production and many West End shows.<br />

9

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

The Questions<br />

What is being done to prevent a greater digital divide occurring between<br />

people who can access superfast broadband and people in areas where the<br />

roll-out of superfast broadband may not be commercially attractive? How<br />

does the UK communications market vary regionally and what is the best<br />

way to connect the areas that the market alone cannot reach? Is a universal<br />

service obligation necessary to avoid widening the digital divide?<br />

1. Arqiva welcomes the opportunity to respond to the House of Lords<br />

Communications Committee’s timely new Inquiry into The Government’s <strong>Superfast</strong><br />

<strong>Broadband</strong> Strategy.<br />

2. The Committee are quite right to begin this Inquiry by focusing on the risk of a<br />

‘digital divide’. Arqiva strongly believes that the real gain for UK plc is to achieve<br />

universal access to broadband - not to push fibre to a little over 90% penetration and<br />

then stop. We believe there would be a considerable opportunity cost (both<br />

economically and socially) if, come 2015, consumers who already have access to<br />

broadband were “super-served” with fibre… while millions who currently have little,<br />

or no, broadband provision remain under-served, forgotten or left behind. Indeed,<br />

there is an ever-greater social and economic cost to each person who falls, or is left<br />

behind on the wrong side of this divide. Indeed, 2009 studies undertaken by<br />

McKinsey, Allen, OECD and the World Bank showed that a 10% increase in<br />

broadband penetration results in a 1% increase in the rate of growth of GDP. Now,<br />

more than ever, the UK needs growth.<br />

3. <strong>Broadband</strong> penetration varies considerably by area, as does its speed and reliability<br />

for consumers who can access it. Sadly, the actual take-up in some areas falls far<br />

short of potential access. Digital inclusion cannot be overlooked.<br />

4. Arqiva, therefore, strongly welcomes the £530 million of public investment in<br />

broadband being managed by DCMS. Yet, it appears that the current broadband<br />

procurements by the Devolved Bodies and Local Authorities in the English Counties<br />

will still leave some consumers without access to broadband by the Government’s<br />

target of 2015. The emphasis placed on making superfast broadband (essentially fibre)<br />

as widely available as possible is a laudable aim - but there are insufficient funds to<br />

offer superfast to all. Some funding must be targeted at other solutions for those<br />

who will not be offered fibre.<br />

5. There needs to be a mixed solution: fibre where it makes most sense to deploy it;<br />

wireless/mobile broadband for the remainder - except for the most remote locations<br />

which could only practically be offered satellite broadband.<br />

6. Only by investing in wireless/mobile broadband alongside fibre can we ensure that<br />

the final 6-8% or so of homes can also have access to a minimum 2 Mbps service.<br />

7. To that end, Arqiva welcomes Ofcom recent revised proposal to increase the<br />

coverage obligation from 95% of the UK population to 98% in the auction of 4G<br />

10

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

licences. This is positive news – however, by setting a UK-wide obligation, rather<br />

than measuring this obligation by Nation separately, England, Scotland, Wales and<br />

Northern Ireland may not benefit equally.<br />

8. Arqiva also strongly welcomes the initiative by the Chancellor of the Exchequer to<br />

invest £150 million in improving rural mobile phone coverage. Although principally<br />

envisaged to address mobile voice “not spots”, it would be a missed opportunity if<br />

this Mobile Infrastructure Project (MIP) failed to secure 4G mobile broadband for<br />

affected consumers, as a complement to the 4G coverage obligation, not least since<br />

many of them would have no reliable fixed line broadband alternative. To maximise<br />

the effectiveness with which the £150 million in invested, shared infrastructure with<br />

shared backhaul should be procured by BDUK.<br />

The Government have committed £530 million to help stimulate private<br />

investment – is this enough and is it being effectively applied to develop<br />

maximum social and economic benefit?<br />

9. Arqiva welcomes the £530 million intervention – but the emphasis appears to be on<br />

enabling the market to deliver superfast to 90% of households by 2015 – rather than<br />

ensuring that all households have reliable access to broadband of at least 2Mbps (fast<br />

enough for iPlayer). We also note that at the time of writing not one single contract<br />

has been placed – so it is too early to tell whether the amount is being effectively<br />

applied.<br />

10. Developing ‘maximum social and economic benefit’ requires more than just<br />

maximising access to broadband, it also requires:<br />

• Competition amongst service providers, where the terms of access to<br />

BT’s infrastructure and services is a factor (we also note that Ofcom<br />

currently proposes to apply the 4G coverage obligation to only one<br />

mobile operator)<br />

• Lowering prices to ensure all households are able to afford access (if<br />

superfast is offered at a premium price to “fast enough” broadband, then<br />

many consumers won’t take it).<br />

• An effective strategy for digital inclusion.<br />

11. However, Arqiva believes the debate about ‘superfast’ broadband is not just about<br />

installing the infrastructure, it’s about the uses to which it is put and what we can<br />

achieve with it. We note that the Government has ambitious plans to move to<br />

digitised public services, which should i) deliver better public services for lower cost;<br />

and ii) create a new dialogue between citizens and public service providers. We<br />

recognise there is also a broad consensus that a programme to address digital<br />

inclusion is essential, not just to ensure that the expected efficiency savings from<br />

digitising public services are achieved, but as an instrument of real social change:<br />

• Improving the life chances for the unemployed.<br />

• Widening access to online educational materials and resources and<br />

ultimately raising children’s grades and life chances.<br />

11

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

• Enabling the financially-disadvantaged and less knowledgeable, or media<br />

literate, to pay the same discounted prices for commercial products and<br />

services as the technology-savvy (who, ironically, are usually better able to<br />

pay more).<br />

12. In addition, there is a risk that the much-heralded huge cost savings from slimming<br />

down “offline” Whitehall will not be realised - until access to digitised public services<br />

becomes universal.<br />

Will the Government’s targets be met and are they ambitious enough? What<br />

speed of broadband do we need and what drives demand for superfast<br />

broadband?<br />

13. The government target of having the “best broadband in Europe” in 2015 is very<br />

challenging, and Arqiva believes this will be difficult to meet within the current<br />

funding if it is interpreted as meaning that there will be universal access to the best<br />

broadband in Europe.<br />

14. Arqiva is concerned, as outlined above, that there remains a risk that not everyone<br />

will get something by 2015. We believe that all households should receive a minimum<br />

of 2 Mbps of reliable broadband which is sufficient to watch BBC iPlayer, and file tax<br />

returns etc. True, consumer demands may exceed this in the future – not least<br />

where demand for faster speed is driven predominantly by ‘multiple-user’<br />

households. However, there is currently no clear legal driver at present for<br />

‘superfast’ broadband.<br />

In fact, are there other targets the Government should set; are there other<br />

indicators which should be used to monitor the health of the digital economy?<br />

What communications infrastructure does the UK ultimately need to remain<br />

competitive and meet consumer demand over the next 20 years?<br />

15. As well as coverage and availability, Government should measure both take-up and<br />

usage. At the moment there is little data captured regarding how services are used,<br />

although we note that the UK is the European leader in e-commerce use.<br />

16. The competitive market is delivering the infrastructure that it thinks consumers will<br />

need and which can be provided at a price that they will pay (which is where<br />

commercial provision in many rural areas is so challenging); it remains the best<br />

arbiter for investing in communications infrastructure. However, in order to ensure<br />

industry continues to invest in the future, both government and Ofcom must ensure<br />

that the levels of competition in the market are maintained and/or strengthened.<br />

12

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

17. In addition, Arqiva believes that as video is the principal driver of consumer-demand<br />

for data (and fast access to it), government needs to also have regard for content<br />

delivery networks and UK-based data centres.<br />

How will individuals and companies use cloud services for distributed<br />

storage and computation? What network properties are required to enable<br />

efficient provision and use of such services?<br />

18. Cloud computing offers flexibility to the Enterprise market, enabling SMEs to access<br />

the computing power previously enjoyed only by much larger competitors. For<br />

consumers, access to cloud services enables content and other data to be shared<br />

between devices so that, for example, phone contacts need no longer be specific to<br />

their current handset, and books and films can be “bookmarked” to enable later<br />

continuation from the same point on a different device.<br />

19. Demand for Data Centres will expand as market demand for digital content and<br />

services grows. As facilities grow in size and number, the associated increase in<br />

power consumption will require far greater efficiency in terms of the facility power<br />

utilisation and within IT server / storage equipment. The growth in HD video and<br />

content distribution networks will require a wider geographical distribution of Data<br />

Centre facilities and require higher capacity connectivity.<br />

To what extent will the advent of superfast broadband affect the ways in<br />

which people view, listen to and use media content? Will the broadband<br />

networks have the capacity to meet demand for new media services such as<br />

interactive TV, HD TV and 3D content? How will superfast broadband<br />

change e-commerce and the provision of Government services?<br />

20. Arqiva maintains that some broadband is better than nothing – and that the faster the<br />

broadband the better the experience. However, the way that audiences are<br />

consuming media content has changed significantly over the past decade. New<br />

platforms, services, applications and devices will continue to shift consumer<br />

behaviour.<br />

21. Consumers are demanding “catch up” content from BBC iPlayer, ITV Player, 4oD<br />

and similar applications in ever greater numbers. Although this is overwhelmingly<br />

additional, rather than substitutional, to consumption of traditional linear television.<br />

Audiences are increasingly irritated by problems like ‘buffering’ from poor broadband<br />

connections. With such applications being rolled out to tablets and other mobile<br />

devices, we are witnessing a shift in consumer demand to more data being consumed<br />

outside the home or office and ‘on the go’.<br />

22. An essential element of the UK’s digital communications infrastructure therefore<br />

needs to be consideration of how far the UK has managed to deliver pervasive<br />

mobile broadband and Wi-Fi – including on the London Underground and major train<br />

13

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

lines where coverage is currently either non-existent or, at best, patchy. Given that<br />

Transport for London and Network Rail are both public sector bodies there is a<br />

clear role for Government in addressing this.<br />

Will the UK's infrastructure provide effective, affordable access to the<br />

'internet of things', and what new opportunities could this enable?<br />

23. The “Internet of Things” is a reference to pervasive “machine-to-machine”<br />

communications, where devices such as energy smart meters, connected TVs,<br />

connected fridges and connected cars unilaterally access the internet to communicate<br />

data about their performance, location, consumer usage data etc. Machine-tomachine<br />

communications is expected to grow exponentially, so that there will be<br />

many more devices connected to the internet than people, although the absolute<br />

amount of data generated may be relatively small.<br />

24. If the UK’s infrastructure is to enable effective access to such communications, then<br />

it needs to be recognised that the “last hop” will almost always be wireless, so both<br />

availability of suitable spectrum and associated infrastructure where demand is likely<br />

to be generated are key considerations.<br />

25. Access could not be regarded as effective if machine-to-machine communications<br />

were essentially precluded from the London Underground, major train lines or major<br />

roads (in that latter case, Intelligent Transport Systems are expected to be a major<br />

growth area where the UK should be positioning itself as Europe’s lead). To that end<br />

public sector bodies such as Network Rail, Highways Agency and Transport for<br />

London will have a role to play.<br />

How might superfast broadband change the relationship between providers<br />

and consumers in other sectors such as content? What aspects of this<br />

relationship are key to enabling future innovations that will benefit society?<br />

26. It is too early to say with any certainty how superfast broadband will change<br />

relationships between providers and consumers in other sectors such as content.<br />

Arqiva notes that during the last decade the digital consumption of music and, for<br />

that matter books, has posed serious questions and challenges for the long-term<br />

future health of the music and book publishing world. The online legal purchase of<br />

music through iTunes and Amazon etc – as well as the ongoing challenges of illegal<br />

downloading has posed questions for producers, and rights-holders as well as the<br />

business models of traditional retailers including HMV, WH Smith and the defunct<br />

Woolworths. <strong>Superfast</strong> broadband may similarly pose challenges for linear<br />

broadcasting and the traditional public service broadcasters, with significant<br />

implications for investment in UK-originated content. However assuming that<br />

consumers will continue to overwhelmingly demand content of UK origin, then<br />

universal access to broadband will offer new routes to market for UK content<br />

producers outside of their traditional relationship with broadcasters.<br />

27. Faster broadband will clearly be beneficial for households likely to demand<br />

simultaneous HD content, but in the medium term ensuring universal access to<br />

14

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

broadband may prove to be a bigger enabler of new content opportunities than<br />

superfast. Whether broadband does change the relationship between content<br />

providers and consumers will also be influenced by ‘data caps’, where even in<br />

Standard Definition a single one hour programme could comprise 1GB of data.<br />

28. For this reason, in addition to its universality, Freeview will continue to offer a more<br />

efficient means of offering a range of (increasingly HD) content to all consumers.<br />

What role could or should the different methods of delivery play in ensuring<br />

the superfast broadband network is fit for purpose and is as widely available<br />

as possible? How does the expected demand for superfast broadband<br />

influence investment to enhance the capacity of the broadband network?<br />

29. Public investment will maximise the number of consumers who will be offered<br />

superfast broadband, where the vast majority will be offered a service based on<br />

Fibre-To-The-Cabinet (FTTC) rather than Fibre-To-The-Premise. But even FTTC<br />

would be prohibitively expensive to provide for many rural consumers, including<br />

many of the 30% of SMEs in rural areas which would be too small to justify their own<br />

dedicated Ethernet line, so would need consumer or small business ISPs for<br />

connectivity.<br />

30. As we contend above, wireless/mobile broadband must complement fixed provision<br />

to ensure that broadband is as widely available as possible. Unlike fixed solutions, no<br />

roads need to be dug up and no ducts shared (not that there are many in rural areas<br />

anyway), so wireless broadband could be deployed quickly.<br />

31. As already stated, given the limited commercial appeal to the market of offering<br />

broadband to the last 5% or so of the population, both Ofcom’s proposed 4G<br />

coverage obligation and the MIP are essential elements in ensuring that those<br />

consumers who won’t be offered superfast are still offered broadband of at least 2<br />

Mbps.<br />

32. There will still be some consumers for whom even wireless broadband would not be<br />

the most cost-effective solution. Where population density falls below 15 houses per<br />

km 2 , satellite is likely to be the cheapest broadband solution. However the level of<br />

monthly subscriptions and associated speed and data caps, latency, and even “rain<br />

fade” are issues with satellite broadband.<br />

Does the UK, for example, have a properly competitive market in<br />

wholesale fibre connectivity? What benefits could such a market provide,<br />

and what actions could the Government take to ensure such a market?<br />

33. Ofcom must remain vigilant that the competition remedies in place continue to<br />

deliver the benefits that we have seen over the last decade, and explore alternative<br />

remedies in the future should existing remedies fail to sustain the level of<br />

competition that the market is capable of supporting.<br />

15

Arqiva – written evidence<br />

What impact will enhanced broadband provision have on the media and<br />

creative industries in the UK, not least in light of the increased danger of<br />

online piracy? What is the role of the Government in assuring internet<br />

security, and how should intellectual property (IP) best be protected, taking<br />

into account the benefits of openness and security?<br />

34. As already argued, universal and (on average) faster broadband connections have the<br />

potential to offer new ways for content producers to reach consumers. Faster<br />

speeds enable simultaneous consumption of HD content and should particularly<br />

provide new opportunities for the UK’s innovative games industry to extend<br />

successful franchises such as Grand Theft Auto to a real-time multi-player service.<br />

35. It is not clear what the relationship might be between piracy and superfast<br />

broadband; one view is that improved infrastructure may better support attractive<br />

legal services that would entice the consumer away from illegal services; another is<br />

that more bandwidth will support more piracy. In any event it is probably not helpful<br />

to link the two issues too closely and instead focus on the current remedies being<br />

pursued now in relation to the protection of IP online. In addition, a move to cloud<br />

services and initiatives such as UltraViolet may help to reduce online piracy.<br />

13 March 2012<br />

16

Avanti Communications – written evidence<br />

Avanti Communications – written evidence<br />

What is being done to prevent a greater digital divide occurring between people who can access<br />

superfast broadband and people in areas where the roll-out of superfast broadband may not be<br />

commercially attractive?<br />

ANSWER<br />

The phrase super fast broadband is misleading. No government report has adequately<br />

explained why 24Mb is necessary. Fibre provides this kind of peak speed, but only in urban<br />

areas, so why promote this as a national target?<br />

But one could alternatively choose to prioritise a technology which provides 100%<br />

geographic coverage at 10Mb as satellite does. The <strong>Broadband</strong> Stakeholder Group, in its<br />

work leading up to the Carter Report did NOT recommend a 24mb standard. We believe<br />

that government has got carried away promoting a technical standard which is unnecessary,<br />

impractical and not at all analysed or clearly understood. 24Mb would only be necessary if<br />

multiple occupants of a dwelling were simultaneously watching streaming high definition<br />

television. Is this an objective worthy of government subsidy, when HD television is<br />

universally available at lower cost with BSkyB?<br />

The provision of fibre on a universal, national basis is a preposterous notion which ignores<br />

fundamental economics. If the £530m is spent on fibre, it will either:<br />

A) subsidise investments which would have been made anyway in densely populated areas,<br />

or<br />

B) fund pilot projects which are not economically viable and will end when the subsidy ends.<br />

Government objectives should instead by re-prioritised to make sure that every family in the<br />

country has a minimum 2mb broadband service. Satellite can provide 10Mb universally and<br />

should therefore be the technology of choice.<br />

How does the UK communications market vary regionally and what is the best way to connect the<br />

areas that the market alone cannot reach? Is a universal service obligation necessary to avoid<br />

widening the digital divide?<br />

ANSWER<br />

There is no such thing as a region that the market cannot reach. Satellite can provide 10Mb<br />

everywhere. The installation costs of up to £400 can be a barrier for some families or their<br />

service providers but are VASTLY lower than the enormous cost of laying fibre outside<br />

cities.<br />

The Government have committed £530 million to help stimulate private investment – is this enough<br />

and is it being effectively applied to develop maximum social and economic benefit?<br />

17

Avanti Communications – written evidence<br />

ANSWER<br />

No, it should be target first at Universal service.<br />

Will the Government’s targets be met and are they ambitious enough? What speed of broadband<br />

do we need and what drives demand for superfast broadband?<br />

ANSWER<br />

The government will fail to ensure that every family has broadband because it is wasting<br />

money on unnecessary pilots with the wrong technology. Every child should have access to<br />

broadband regardless of family income, and every job seeker should have the same access to<br />

information.<br />

In fact, are there other targets the Government should set; are there other indicators which<br />

should be used to monitor the health of the digital economy? What communications infrastructure<br />

does the UK ultimately need to remain competitive and meet consumer demand over the next 20<br />

years?<br />

ANSWER<br />

Universal Service should be mandatory.<br />

How will individuals and companies use cloud services for distributed storage and computation?<br />

What network properties are required to enable efficient provision and use of such services?<br />

No comment<br />

To what extent will the advent of superfast broadband affect the ways in which people view, listen to<br />

and use media content? Will the broadband networks have the capacity to meet demand for new<br />

media services such as interactive TV, HD TV and 3D content? How will superfast broadband<br />

change e-commerce and the provision of Government services?<br />

ANSWER<br />

The highest profile media will remain broadcast because it is time sensitive, and this is<br />

overwhelmingly more efficient using broadcast technology rather than unicast. Time shifted<br />

download content will grow, but it will not dominate, and the costs of using it will moderate<br />

consumer behavior.<br />

Will the UK's infrastructure provide effective, affordable access to the 'internet of things', and what<br />

new opportunities could this enable?<br />

ANSWER<br />

The market will provide adequate service; the question which remains is about affordability<br />

to the poorest families.<br />

18

Avanti Communications – written evidence<br />

How might superfast broadband change the relationship between providers and consumers in other<br />

sectors such as content? What aspects of this relationship are key to enabling future innovations<br />

that will benefit society?<br />

What role could or should the different methods of delivery play in ensuring the superfast<br />

broadband network is fit for purpose and is as widely available as possible? How does the expected<br />

demand for superfast broadband influence investment to enhance the capacity of the broadband<br />

network?<br />

ANSWER<br />

Money wasted on fibre subsidy is crowding out the benefits of Universal Service.<br />

Does the UK, for example, have a properly competitive market in wholesale fibre connectivity? What<br />

benefits could such a market provide, and what actions could the Government take to ensure such a<br />

market?<br />

No comment<br />

What impact will enhanced broadband provision have on the media and creative industries in the<br />

UK, not least in light of the increased danger of online piracy? What is the role of the<br />

Government in assuring internet security, and how should intellectual property (IP) best be<br />

protected, taking into account the benefits of openness and security?<br />

No comment<br />

12 March 2012<br />

19

Bentley Walker – written evidence<br />

Bentley Walker – written evidence<br />

May I present the following remarks/responses to points raised in respect to broadband<br />

delivery throughout the UK.<br />

Digital Britain target is questionable!<br />

The delivery through fibre optic service suppliers has a major part to play and one would<br />

imagine a significant target to achieve. The costs associated are obviously significant and<br />

the time to complete the infrastructure completion is upon us. I readily except that Fibre<br />

Optic services for broadband are suitably justified throughout urbanised areas but to what<br />

expense elsewhere. I just feel that we have been ignored to some degree as a satellite<br />

internet service provider, currently delivering systems to many homes through the UK,<br />

providing speeds up to 10mgbts/sec. If you map out the not spots and allocate satellite<br />

broadband services to these locations then the job to achieve Digital Britain becomes easier<br />

to achieve. We could work together with these fibre optic service providers to deliver the<br />

satellite broadband solution where the infrastructure becomes unfeasible, this would make<br />

some sense. We could actively complete 1,000s of installations throughout the UK within<br />

weeks; it is purely a case of working out our position and objectives adding a government<br />

supportive marketing statement explaining our position in respect to the delivery of<br />

broadband to these rural communities/villages.<br />

Please examine our pricing and proposal based on a method to achieve the Digital Britain<br />

target in conjunction to Fibre Optic services which means a subscription from the second<br />

month is the only payment required by the customer cost.<br />

Customer requires hardware & installation plus a service speed of 6mgbts/sec download and<br />

is a (light user) £214.99 hardware cost and completed installation which includes the first<br />

month subscription @ £24.99 /month. (All prices inc vat.)<br />

With a grant of £250.00 by allocation we can then actively market the services to these<br />

locations with the supportive statement outlining our position in providing internet<br />

connection at these locations. The problems with current grant arrangements it is left to the<br />

customer to become aware of the offer which leads to low up takes and the service<br />

provider to not market the product effectively.<br />

17 February 2012<br />

20

Boundless Communications Ltd – written evidence<br />

Boundless Communications Ltd – written evidence<br />

Questions the Committee will consider: Response Name/Status Response on behalf of Boundless Communications<br />

What is being done to prevent a greater<br />

digital divide occurring between people<br />

who can access superfast broadband and<br />

people in areas where the roll-out of<br />

superfast broadband may not be<br />

commercially attractive? How does the<br />

UK communications market vary<br />

regionally and what is the best way to<br />

connect the areas that the market alone<br />

cannot reach? Is a universal service<br />

obligation necessary to avoid widening<br />

the digital divide?<br />

1 Andy Wilson, Chief<br />

Executive<br />

Boundless Communications<br />

21<br />

There has been and continues to be a great deal of coverage<br />

about bridging the digital divide with many private and<br />

Government initiatives aimed at delivering a uniformly high speed<br />

service. It is our view that although these initiatives are well<br />

intentioned most seem to start from the premise that the only<br />

way forward is “Fibre”. Although this is an ideal solution for<br />

many premises (business and residential) it is not a cost effective<br />

solution for many in rural communities and some business parks,<br />

located on the outskirts of many towns. As a consequence the<br />

strategy of ”upgrading exchanges and certain cabinets with fibre”<br />

will actually widen the digital gap by delivering higher and higher<br />

speeds to the people that currently receive acceptable<br />

broadband whilst leaving many people with the same or even<br />

lower speeds.<br />

For example it is estimated that this type of policy would address<br />

95 -97% of the population in Lancashire; Lancashire County<br />

Council estimates, January 2012.<br />

It is our view that the 3-5% not covered will probably account<br />

for over 10% of the rural community; the very communities<br />

these initiatives are aimed at.<br />

This does not have to be the case. It is possible to deliver a<br />

super-fast service at speeds of up to 100Mbps into virtually all<br />

community groups and businesses now. To do this government<br />

strategy needs to change from a technology, grant funding and<br />

partnership perspective to achieve it.

Boundless Communications Ltd – written evidence<br />

The Government have committed<br />

£530 million to help stimulate private<br />

investment – is this enough and is it<br />

being effectively applied to develop<br />

maximum social and economic benefit?<br />

Will the Government’s targets be met<br />

and are they ambitious enough? What<br />

speed of broadband do we need and<br />

what drives demand for superfast<br />

broadband?<br />

In fact, are there other targets the<br />

Government should set; are there other<br />

2 Andy Wilson, Chief<br />

Executive<br />

Boundless Communications<br />

3 Andy Wilson, Chief<br />

Executive<br />

Boundless Communications<br />

4 Andy Wilson, Chief<br />

Executive<br />

22<br />

By adopting a blend of FTTC (Fibre To The Cabinet) and FTTM<br />

(Fibre To The Mast) coupled with high speed radio delivery to<br />

the premises that cannot be reached easily with fibre it is<br />

possible to deliver 100Mbps broadband to virtually everyone<br />

now.<br />

Grant funded FTTC schemes will not address the demand or the<br />

population fully in Rural areas. A “Universal Service Obligation”<br />

is a must along with the recognition that large Tier 1 providers<br />

will not deliver without partnerships with other smaller rural<br />

providers.<br />

The £530M is a welcome addition to help bridge the “Digital<br />

Divide”. However, many organisations ideally suited to deliver<br />

maximum benefit to rural communities are prohibited from<br />

bidding because of the selection criteria used. It appears to be<br />

geared towards large Tier 1 providers. Adopting a more flexible<br />

approach would allow other companies to participate delivering<br />

greater penetration and a faster roll out at a much lower price<br />

point.<br />

Targets will always be achieved if the criteria used for defining<br />

them are not tight enough. For example “97% of the population<br />

will receive superfast broadband” is a great headline figure and<br />

technically true. However if you are in the 3%, which may<br />

actually equate to 10 or 20% of the rural population in<br />

geographic terms, it is a failure. Care should be taken to ensure<br />

any targets will directly drive benefits to the communities in real<br />

need. It is possible with a blend of technology to deliver high<br />

speeds to the majority of communities providing coverage close<br />

to 100%.<br />

See (1 & 3) above however more specific measurements<br />

focussed directly at the target communities and groups should be

Boundless Communications Ltd – written evidence<br />

indicators which should be used to<br />

monitor the health of the digital<br />

economy? What communications<br />

infrastructure does the UK ultimately<br />

need to remain competitive and meet<br />

consumer demand over the next 20<br />

years?<br />

What role could or should the different<br />

methods of delivery play in ensuring the<br />

superfast broadband network is fit for<br />

purpose and is as widely available as<br />

possible? How does the expected<br />

demand for superfast broadband<br />

influence investment to enhance the<br />

capacity of the broadband network?<br />

Does the UK, for example, have a<br />

properly competitive market in<br />

wholesale fibre connectivity? What<br />

benefits could such a market provide,<br />

and what actions could the Government<br />

take to ensure such a market?<br />

March 2012<br />

Boundless Communications implemented. For example tighter geographic speed targets<br />

down to post code sector (incode) level rather than high level<br />

percentage statements. This would focus any funding to areas of<br />

real need rather than “easy wins”. This approach would<br />

maximise the benefit into areas either poorly or not served at all.<br />

5 Andy Wilson, Chief<br />

Executive<br />

Boundless Communications<br />

6 Andy Wilson, Chief<br />

Executive<br />

Boundless Communications<br />

23<br />

See (1) above. It is essential if we are to achieve a near universal<br />

superfast service to use a variety of delivery methods. FTTC and<br />

fibre to the home is not a cost effective or practical solution for<br />

many rural properties. A combination of 4G, FTTC, FTTM and<br />

either fibre to the home or high speed radio links will allow the<br />

government to exceed its superfast broadband goals. A pure<br />

fibre strategy will fail and prove to be prohibitively expensive. A<br />

typical radio link from an FTTM mast can be delivered for less<br />

£300 per property. The equivalent fibre delivery in hard to<br />

reach communities would typically run into the thousands or<br />

even tens of thousands per property.<br />

YES in major towns and cities however NO in rural areas. A<br />

scheme that would allow rural broadband projects either<br />

managed by the community or speculative ventures by business<br />

to receive subsidised super high speed fibre backhaul, Gbps<br />

speeds, would massively reduce the delivery costs for these<br />

projects. This would allow smaller more agile<br />

organisations/communities to offer competitive superfast<br />

services in areas that would not be cost effective otherwise.<br />

Local connectivity is a must but this must be coupled with high<br />

speed backhaul to ensure the digital gap is bridged.

British Film Institute – written evidence<br />

British Film Institute – written evidence<br />

Introduction<br />

1. The British Film Institute (BFI) is today the lead organisation for film in the UK.<br />

Founded in 1933, it has always been a champion of film culture in the UK but in its<br />

new wider role, it has the additional purpose of supporting and helping to develop<br />

the entire film sector. Its Royal Charter emphasises its responsibilities to develop the<br />

arts of film, television, and the moving image. Its new role as a Government armslength<br />

body and distributor of Lottery funds, widens the BFI’s strategic focus and<br />

increases its potential impact, both culturally and industrially.<br />

The BFI welcomes the opportunity to respond to the House of Lords Select<br />

Committee on Communications’ Call for <strong>Evidence</strong> in relation to its inquiry into the<br />

Government’s superfast broadband strategy.<br />

2. The Government’s broadband strategy has important implications for the film<br />

industry in general, and for film culture and the BFI’s public policy goals in particular.<br />

As with other content industries, the internet is transforming the ways in which films<br />

are delivered and consumed, both legally and illegally. As with other forms of<br />

content, there are both opportunities and threats.<br />

3. The greatest opportunity comes from the growing availability of video-on-demand<br />

(VOD) services, which allow potentially limitless libraries of films to be offered to<br />

people wherever they live. Films and other forms of audiovisual content are being<br />

consumed in greater amounts on smart-phones and tablet devices. And as take-up of<br />

connected TVs grows, VOD services will migrate over time from PCs to TV sets,<br />

allowing families and friends to watch films together on large screens in their living<br />

rooms.<br />

4. The BFI especially welcomes the access VOD services can potentially provide to<br />

contemporary and classic British and international films that have historically been<br />

difficult to see, especially for people who live a distance from their nearest<br />

independent cinemas (which are typically located in the main metropolitan areas). As<br />

well as allowing films themselves to be distributed, new digital services offer a wide<br />

range of information on films – such as film-related news and blogs, previews and<br />

clips, and reviews – enabling communities of fans to engage more deeply with the<br />

films that they love.<br />

5. As DVD sales fall, it is important for film rights-holders to be able to develop new<br />

business models that generate sufficient income from the exploitation of films via<br />

online services. Alongside the difficulty in establishing viable business models, one of<br />

the biggest threats to the film industry comes from copyright theft and infringement,<br />

given the ease with which it is possible to make perfect digital copies of films and<br />

distribute them illegally around the world.<br />

6. The Call for <strong>Evidence</strong> asks if superfast broadband will meet the needs of our<br />

“bandwidth hungry” nation. More than any other popular form of content, film is<br />

highly reliant on fast and reliable broadband services to enable online distribution,<br />

given the large data requirements: it is audiovisual in nature, feature-length films often<br />

24

British Film Institute – written evidence<br />

run to more than two hours in duration, and consumer expectations of high picture<br />

and sound quality are typically higher than for other forms of audiovisual content<br />

(such as TV programmes). Our understanding is that minimum bandwidth<br />

requirements of 3Mb/s are needed to provide DVD-quality pictures. The<br />

requirements for HD video are higher (in the region of 5-10Mb/s) and much higher<br />

still to match the quality of Blu-ray discs (50-100 Mb/s).<br />

7. For these reasons, the rollout of superfast broadband in the UK will have a significant<br />

effect on the film sector. This brief submission responds to the issues raised by the<br />

Call for <strong>Evidence</strong> that are of greatest concern to the BFI. We would be pleased to<br />

provide further information to the Select Committee on any of the matters<br />

discussed, on request.<br />

Responses to individual questions<br />

Overall communications infrastructure<br />

1. What communications infrastructure does the UK ultimately need to remain<br />

competitive and meet consumer demand over the next 20 years?<br />

The BFI believes that the UK needs a broadband infrastructure that is (a) universally<br />

available, and (b) sufficiently fast to provide the full range of digital media services that<br />

people will demand. We discuss these points in relation to other questions in greater<br />

detail below.<br />

2. To what extent will the advent of superfast broadband affect the ways in<br />

which people view, listen to and use media content? Will the broadband<br />

networks have the capacity to meet demand for new media services such as<br />

interactive TV, HD TV and 3D content?<br />

For films, in particular, the availability and quality of superfast broadband services will<br />

have a significant impact on levels of consumption in the home. The success of DVDs<br />

relative to their predecessors, VHS cassettes, indicates how much consumers value<br />

superior picture and sound quality, and how this can drive levels of consumption.<br />

The growth in demand for large flat-screen HD TV sets in people’s homes has led to<br />

the increased popularity of Blu-ray discs in recent years, offering even higher levels of<br />

quality, including the ability to offer films in 3D (this also requires special TV sets and<br />

glasses, although glasses-free 3D technologies are expected to come to market in the<br />

near future). Audiences increasingly want to watch feature films at home with the<br />

highest levels of picture and sound quality. New VOD services linked to connected<br />

TVs can potentially bring vast libraries of films to people’s living rooms. But such<br />

services can only deliver HD-level (or higher) sound and vision with superfast<br />

broadband. Reliability of service is also very important. At peak times of day,<br />

delivered broadband speeds can be substantially less than advertised rates. This has a<br />

disproportionate impact on video streaming services. As with other utilities, fit-forpurpose<br />

broadband networks need sufficient capacity to be able to meet demand at<br />

all times of day.<br />

More generally, superfast broadband opens up the potential for a broader range of<br />