Download it Here - Eartrip Magazine

Download it Here - Eartrip Magazine

Download it Here - Eartrip Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CONTENTS<br />

Ed<strong>it</strong>orial<br />

By David Grundy.<br />

Paul Desmond (Part Three)<br />

The tale continues, as Paul Desmond finds himself in the midst of a satanic r<strong>it</strong>ual,<br />

playing bamboo flutes in a frozen wasteland, and attempting to represent complex<br />

philosophical truths. Dr Martin Luther Blisset remains your humble narrator.<br />

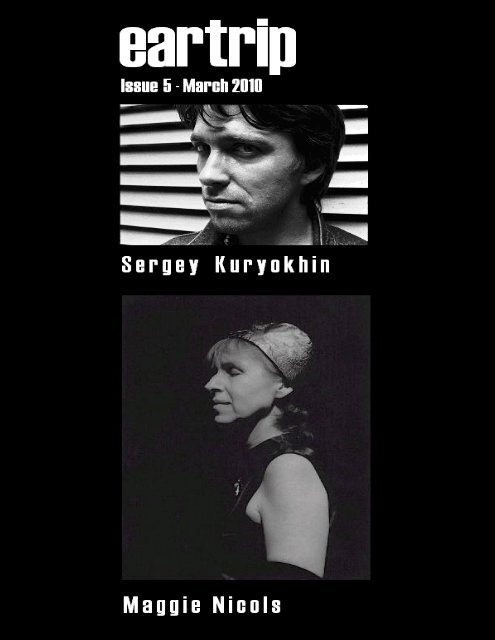

An Appreciation of Sergey Kuryokhin: On the Occasion of<br />

a Reissue of Some Combinations of Fingers and Passion<br />

“An unpredictable unfolding of contradictory states, agony, jouissance, terror, hope,<br />

dementia, insight...” By Seth Watter<br />

Gender and Music: “In Our Different Rhythms Together”<br />

“Maybe one day, there will no longer be the need for special features on gender; a post<br />

Patriarchal Cap<strong>it</strong>alist society will experience genuine divers<strong>it</strong>y & humankind's<br />

multidimensional difference will be what unifies us. Until then, I'm happy to grapple<br />

w<strong>it</strong>h the contradictions of gender & music in our time.” The complex relations between<br />

gender and free improvisation form a topic which always seems to receive less scrutiny<br />

than <strong>it</strong> should; hence Maggie Nicols’ essay, which addresses some of the issues at<br />

stake, w<strong>it</strong>h particular reference to her own career at the forefront of improvised music.<br />

You Tube Watch<br />

Videos documenting recent live performances by the Lucio Capece/Christian Kesten<br />

duo, and the trio of Tania Chen, Shabaka Hutchings and Mark Sanders, as well as a<br />

studio session featuring the great bassist Cecil McBee, and archive footage of John<br />

Klemmer in his pre-Smooth Jazz phase.<br />

CD Reviews<br />

From music for contemporary jazz big band, to new releases by established masters of<br />

free jazz and improvisation, and new experimental works for voice and electronics.<br />

Artists include Wadada Leo Sm<strong>it</strong>h, Bill Dixon, Joel Futterman, Darcy James Argue and<br />

Gigantomachia. Plus ESP-Disk re-issues of recordings by Charles Tyler, The<br />

Revolutionary Ensemble, and Sun Ra bassist Ronnie Boykins; and a re-vis<strong>it</strong>ed version<br />

of a 1970s solo recording by Byard Lancaster. Reviewed by David Grundy, Ian<br />

Thumwood and Sandy Kindness.<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Under consideration are: Martin Williams’ take on Miles Davis’ ‘Kind of Blue’; the first<br />

ever free jazz coffee-table book; and a thought-provoking collection of essays<br />

considering the relation between noise and cap<strong>it</strong>alism.<br />

Gig Reviews<br />

Gannets and Phil Waschmann blow away the cobwebs in Oxford; Sunn O))) threaten to<br />

undermine the building w<strong>it</strong>h the force of their sonic vibrations in Bristol.

PAUL DESMOND (Part Three)<br />

By Dr Martin Luther Blisset

English Winter can be Real Bad<br />

The hands of the clock run backwards. Reverse-twisted mirror<br />

above the oak beamed fireplace; A small wh<strong>it</strong>ewashed cottage, probably<br />

16 th century. Somewhere south of the river, South West of London. Thick<br />

fog outside.<br />

“Welcome, Mister Brubeck – or may we call you Dave?”<br />

“Yes, call me Dave, let’s not be formal.”<br />

“Well okay Dave, <strong>it</strong>’s lovely to have you w<strong>it</strong>h us. I’m Cleo, and of<br />

course you know my husband Johnny…”<br />

“Yes, I have long admired your work…”<br />

Blackthorn hedges obscure the remote stable-yard. As midnight<br />

approaches hooded figures assemble in a torchlight procession. Low<br />

voices chant ancient winter rhymes; the firelight sparks and throws up<br />

long shadows against the outbuildings.<br />

“Our number is complete, thirteen are assembled here…”<br />

“And call me Mom, relax…and of course we call dad ‘Father<br />

Johnny’…”<br />

Brubeck stands in the centre circle. It's freezing. This isn't<br />

California, that's for sure. And these English customs can be a l<strong>it</strong>tle<br />

strange. Old-World ways I guess... Gosh I wish they’d give me back my<br />

clothes though…<br />

Cleo steps into the firelight: “Human Beings, Mister Brubeck, are<br />

like dogs, are they not? Dogs that that have been trained to stand on<br />

their hind legs, to dance and wear skirts and dive through burning<br />

hoops, or chase hares for sport; to be rewarded or chastised according to<br />

their performance. We are no more emotionally equipped to deal w<strong>it</strong>h the<br />

lives we live than are trained poodles..."<br />

Sinister half-tone harmonies, rough voices rising in cadence.<br />

Brubeck shivers. Wh<strong>it</strong>e skin rising in gooseflesh. Johnny Dankworth,<br />

wearing a cape which seems to be made of dried fish skins and turkey<br />

feathers, begins to swing a flaming censer in a wide arc above the heads<br />

of the cowled peasants.<br />

“Cleo, Cleo!”<br />

“Yes darling what is <strong>it</strong>?”<br />

“The knife, dear, the knife.”<br />

“Ah yes, yes of course…”<br />

Cleo casts her robe aside, her proud breasts rising and falling in<br />

the firelight. In her right hand a silver dagger gleams, <strong>it</strong>s curved blade<br />

flat against her skin.<br />

Father Johnny places a bowl at Brubeck's feet.<br />

If You like Music That Doesn't Go Anywhere, Then This<br />

Could Be For You...<br />

Thatched sticks, a lattice of frozen ferns. Paul Desmond halted his

team of dogs and reached for the flask of brandy…<br />

The stone farmhouse seemed deserted. He made his way through<br />

the knee-deep snow to the wooden door.<br />

"Honey, I'm home.."<br />

there was no one. the farmhouse was deserted. he sat at the<br />

wooden table in the middle of the only room and reached into his jacket<br />

pocket. no one answered him. the old farmhouse was deserted. “where’s<br />

the. where’s the.” he reached into his inside jacket pocket, sat at the<br />

table and pulled out the kendal mint cake.<br />

“one piece. one piece now. there are no pieces. outside outside. ok<br />

doggies. ok i’m coming. the music of the night. such sweet music. you<br />

call that music.” he rested his head on the wooden table top. in the<br />

morning he was dead. there was a brubeck cd on the table in front of<br />

him. he had no idea what this object could be. <strong>it</strong> was 1963. the dogs<br />

were howling.<br />

“howling at the grave of their master. one more piece. all is in<br />

pieces. we can look inside. i am inside. paul? paul? hello, come in. this is<br />

the way step inside. the drill is in my head. i am the drill head. i am<br />

drilling. right left right left. quickmarch. slow april. the tattoo. mil<strong>it</strong>ary.<br />

they fucked him up, the army did. at heart i am a muslim. at heart i am<br />

an american.”<br />

the snow and ice opened up in front of him. the sledge moved<br />

gliding over the flat wh<strong>it</strong>e grey terrain.<br />

“mush mush. the dogs. the dogs. petties. petty concerns. out in the<br />

ice. nothing is real. only the ice. there is no real<strong>it</strong>y. only the ice knows<br />

this. the pur<strong>it</strong>y of water freezing. unconcerned. mish mash. mish mash.<br />

onward. i will play the only music. the music of bamboo. bamboo and<br />

flute. at heart i am an eskimo, an inu<strong>it</strong> person.” he looked out into the<br />

wastelands of ice and snow. he raised his head and shouted. "fuck you<br />

brubeck.there is no symmetry. who gave you this number?” their last<br />

conversation coming back at him, recurring here on the ice.<br />

“Jeez old pal come on, <strong>it</strong>’s me David for chrissakes. Come on now.<br />

Come back why dontcha. We been working on some new tunes.<br />

Symmetrical scales man. Morello met this guy, Lacy, soprano player?<br />

Anyways this guys been showing Morello, the banjo player, been showing<br />

him these scales. What you do see, is you spl<strong>it</strong> the octave down the<br />

middle. So, take say, C ok, F sharp’s the middle note. And then you put<br />

notes in around that symmetrically. C then E. F sharp and then G.’<br />

“who gave you this number? this number is ex-directory. how did<br />

you get this number?”<br />

“Come on pal. Hey you know what? We’ve done some tunes, back<br />

to the old whole tone scale. Four four time. There’s only two whole tone<br />

scales. So you always know you’re e<strong>it</strong>her in one or the other. Sh<strong>it</strong>, what<br />

d’you say. Come on back Paul, we need you.”

he held the receiver out and looked at <strong>it</strong>. black plastic against the<br />

wh<strong>it</strong>e and grey landscape, the wind in his ears. his beard freezing.<br />

“no,this is plastic. there is no plastic in real<strong>it</strong>y.” he caught himself<br />

thinking wrong. “there is nothing. all is not. nothing is not. everything is<br />

nothing.” he knew only the ice could know. he threw away the telephone.<br />

“there is no plastic in the allness.” he threw his head back. was he<br />

moving? did he really just holler?<br />

“no scales in the oneness. only the sound of the chimes. the<br />

bamboo and the flute. the ice. water. the music of night. such sweet<br />

songs. i too have. i too have loved. i too have loved. puppies. puppies.<br />

mish mash mish mash. hoykee carokee. the chimes.”<br />

he patted the tarpaulin bundle in front of him on the sledge. “the<br />

chimes. everything is in the bamboo. nothing is real. this is the way step<br />

inside. i am outside. outside of society, of real<strong>it</strong>y. are we moving. the<br />

mint cake. the mint cake.”<br />

hours later he came to. the sledge was still. “the wind, the wind is<br />

howling, through the graves the wind <strong>it</strong> howled. puppies. i will have to<br />

eat the dogs. godawful. dogs shaped like a sausage hot doggedy dawg.<br />

ketchup. gotta catch up. brubeck will beat me to <strong>it</strong>. play his awful music<br />

to the frozen wastes. a waste of fuckin space. space monkey. i will eat<br />

them or they will eat me. are we moving?”<br />

hours later he reached the bamboo chimes from their tarpaulin<br />

wrapping. “frozen to themselves. the wind howls through my thermal<br />

longjohns. no sound. only the ice and my flute.” his grass skirt was solid,<br />

stuck to <strong>it</strong>self. “ there is no symmetry, only the ice. the water of<br />

everything. nothing. all is illusion. i am gone. i am not.<br />

minutes later he came to on all fours. “no scales in infin<strong>it</strong>y dave.<br />

no scales in infin<strong>it</strong>y. i will listen to the ice. my flute will join the music of<br />

all that is.” he put his ear to the ice. there was an almighty silence. the<br />

cold filled his ear and then <strong>it</strong> filled his brain. then he was dead.<br />

hours later he was one w<strong>it</strong>h the ice. his flute stood up erect from<br />

the ice. he was dead.<br />

One minute later, four big tyres, supporting a large land rover,<br />

pulled up on the ice, alongside his head. "Ok you guys, you know the<br />

drill. Put him in the trunk." Footsteps on the snowy ice.<br />

"Goddam, boss this stuff's slippery."<br />

"Boss, think you better come look at this."<br />

"What? What's to see? Just get him up off the ground and into the<br />

trunk."<br />

He had a new tune going round his head. He wrote the chords down on a<br />

match box. "Sh<strong>it</strong>, yeah, I think this one's in one hundred and sixty four<br />

eleven time." He chuckles to himself. "Hot damn. The good old days are<br />

coming back."<br />

"Boss?"<br />

"Ok. Ok."

"It's his head. His face. It's stuck to the ice."<br />

"What's w<strong>it</strong>h you guys. We've planned for this. You know we have.<br />

Get the goddam primus stove out. Hot water is what we need. We'll have<br />

some coffee while we're at <strong>it</strong>. Jeez this place is the end. Cold, or what?"<br />

As the strong dark espresso eased his troubled mind, he whistled<br />

Bridge over Troubled Water to himself. "I kept telling you to step on the<br />

gas Morelloid."<br />

"Yeah sure boss, and you also kept telling me to play fuckin riffs<br />

on my goddam tenor, while I was tryna drive. And I'm pretty sure, even<br />

out here, that aint strictly legal. I coulda lost points off my license pal."<br />

They pour hot water over his Paul's frozen face, till eventually<br />

there's a thaw between him and the ice. Dave shoots each of the dogs in<br />

the head to accompanying yelps. They dump him in the trunk and drive<br />

off.<br />

"Hey Paul, yeah, <strong>it</strong>'s Braxton here, yeah. Listen man there's this<br />

guy over in England they reckon plays even more anodyne tone than you<br />

man, more bland even, like he's the fucken total BLANDMEISTER or<br />

somethin'"<br />

"Sorry, are you chewing something Anthony? I can't make out what<br />

you're saying."<br />

"There's this guy in England man, alto player who I think you<br />

should hear. A real SLIGHT kinda tone, almost nothing there you dig?<br />

Name's Dank-somethin'. Some kinda dank name y'know. Mystical cat<br />

too, does the Wh<strong>it</strong>e Voodoo apparently. Married to a black chick. Well,<br />

kinda black i guess."<br />

"You still fooling around w<strong>it</strong>h the flute?"<br />

"Yeah man, 'Fool's Bamboo' as they say. I gotta try & learn <strong>it</strong><br />

though, for this thing w<strong>it</strong>h Marilyn. Got this booking at a pasta joint up<br />

in Vancouver.”<br />

Later, after Braxton was gone off the phone & everything had fallen<br />

back into stillness, Paul Desmond lay awake staring at the clapboard<br />

ceiling. This Dankworth business was beginning to disturb him. This<br />

wasn't the first time someone had tried to hip him to this English guy.<br />

Saxophone tone like milk in water. Plays w<strong>it</strong>h almost no attack, no<br />

inflection. Nothing there behind the sound. Almost no sound at all, if<br />

reports were true. Nothing there man, no feeling, no soul.<br />

Shadows run towards you. The night pulls you into <strong>it</strong>s vortex.<br />

Flicker of stars. Naked skin in firelight. The distorted faces of the<br />

dancers. Blood. Feathers. A black cockerel. Unspeakable r<strong>it</strong>es hidden,<br />

veiled. The low throb of drums always there in the distance. Ghost<br />

trains passing in his sleep.<br />

"Paul, Paul, wake the fuck up! You were screaming."<br />

Lauretta stands in the doorway in laddered stockings. Moonlight<br />

silvering the edge of her hair. Smoking a goddamn cigarette & breath<br />

loaded w<strong>it</strong>h Jim Beam. Or Wild Turkey...Too late to tell anyway, the

ottle comes flying right at him, shattering in the corner. Broken glass<br />

raining down like falling stars.<br />

"okay, that's <strong>it</strong> you goddam unreasonable fuckin whore." He picked<br />

up the broken bottle got out of bed and walked towards her, her drunken<br />

face in the centre of his radar scanner.<br />

“Oh jeez, I'm so scared. Is he back in his goddam jesus mood<br />

again?" She started to smile but the broken glass interrupted the<br />

movement of muscle. Her skin broke. His fist came in behind the bottle.<br />

"All you ever fuckin do is swear and cuss me, you fucking b<strong>it</strong>ch."<br />

Over and over he stabs her, in the neck, the chest, her hands as they try<br />

to defend herself, her stomach.<br />

When <strong>it</strong>'s all over he looks at the blood dripping from the bamboo<br />

chimes. This is the only tragedy he sees; that his chimes are sullied. He<br />

is glad he's finally smashed the sh<strong>it</strong>ty life out of her. He asks himself how<br />

long he's been enduring this wreck of a woman thrashing around in his<br />

space, contaminating the air, the peace, the acoustic.<br />

Taking the smallest of the flutes in his shaking, bloodsoaked hand<br />

he puts <strong>it</strong> into a backpack and starts to pack. "Think <strong>it</strong>'s time to head<br />

north. No more commerce and trade and too much brute ugliness. Gotta<br />

go." He is whispering. "Gotta go." He is whimpering. He is softly crying.<br />

Like he used to in the cupboard, under the stairs when he was a boy,<br />

listening for the creak of footsteps that preceded his release. He used to<br />

whisper to himself "<strong>it</strong>'ll all be okay." Over and over. "It'll all be okay.<br />

Don't worry." Then he'd make up tunes, silently, in his mind.<br />

Slinging his backpack over his shoulder her steps over her body.<br />

Something wheezes. Air or a fart, or something coming out of her. "Head<br />

for the snow, buddy. Head for the snow. There's nothing and no one here<br />

for you."<br />

King Of Dogsh<strong>it</strong> & Twigs<br />

“All contemporary musical life is dominated by the commod<strong>it</strong>y form…”<br />

“Yeah, maybe, but listen to this…”<br />

A familiar hellish skronking noise, BBBBAaaauugggghh!!!, spl<strong>it</strong> notes,<br />

reedsequeak…<br />

“Beautiful, man, just beautiful"

The language of music is qu<strong>it</strong>e different from the language of<br />

intentional<strong>it</strong>y. It contains a theological dimension. What <strong>it</strong> has to say is<br />

simultaneously revealed and concealed. Its Idea is the divine Name which<br />

has been given shape. It is demythologized prayer, rid of efficacious<br />

magic. It is the human attempt, doomed as ever, to name the Name, not<br />

to communicate meanings.<br />

Who could have foretold this New Orleans revival, nearly twentyfive<br />

years after Bunk Johnson acquired his new teeth?<br />

"Listen man, I'll tell you a l<strong>it</strong>tle secret: The most drastic example of<br />

standardization of presumably individualized features is to be found in<br />

so-called improvisations. Even though jazz musicians still improvise in<br />

practice, their improvisations have become so "normalized" as to enable a<br />

whole terminology to be developed to express the standard devices of<br />

individualization: a terminology which in turn is ballyhooed by jazz<br />

public<strong>it</strong>y agents to foster the myth of pioneer artisanship and at the<br />

same time flatter the fans by apparently allowing them to peep behind<br />

the curtain and get the inside story. This pseudo-individualization is<br />

prescribed by the standardization of the framework. The latter is so rigid<br />

that the freedom <strong>it</strong> allows for any sort of improvisation is severely<br />

delim<strong>it</strong>ed. Improvisations — passages where spontaneous action of<br />

individuals is perm<strong>it</strong>ted ("Swing <strong>it</strong> boys") — are confined w<strong>it</strong>hin the walls<br />

of the harmonic and metric scheme. In a great many cases, such as the<br />

"break" of pre-swing jazz, the musical function of the improvised detail is<br />

determined completely by the scheme: the break can be nothing other<br />

than a disguised cadence. <strong>Here</strong>, very few possibil<strong>it</strong>ies for actual<br />

improvisation remain, due to the necess<strong>it</strong>y of merely melodically<br />

circumscribing the same underlying harmonic functions. Since these<br />

possibil<strong>it</strong>ies were very quickly exhausted, stereotyping of improvisatory<br />

details speedily occurred. Thus, standardization of the norm enhances in<br />

a purely technical way standardization of <strong>it</strong>s own deviation — pseudoindividualization.<br />

"This subservience of improvisation to standardization explains<br />

two main socio-psychological qual<strong>it</strong>ies of popular music. One is the fact<br />

that the detail remains openly connected w<strong>it</strong>h the underlying scheme so<br />

that the listener always feels on safe ground. The choice in individual<br />

alterations is so small that the perpetual recurrence of the same<br />

variations is a reassuring signpost of the identical behind them. The<br />

other is the function of "subst<strong>it</strong>ution" — the improvisatory features forbid<br />

their being grasped as musical events in themselves. They can be<br />

received only as embellishments. It is a well-known fact that in daring<br />

jazz arrangements worried notes, dirty notes, in other words, false notes,<br />

play a conspicuous role. They are apperceived as exc<strong>it</strong>ing stimuli only<br />

because they are corrected by the ear to the right note. This, however, is<br />

only an extreme instance of what happens less conspicuously in all<br />

individualization in popular music. Any harmonic boldness, any chord

which does not fall strictly w<strong>it</strong>hin the simplest harmonic scheme<br />

demands being apperceived as "false", that is, as a stimulus which<br />

carries w<strong>it</strong>h <strong>it</strong> the unambiguous prescription to subst<strong>it</strong>ute for <strong>it</strong> the right<br />

detail, or rather the naked scheme. Understanding popular music means<br />

obeying such commands for listening. Popular music commands <strong>it</strong>s own<br />

listening hab<strong>it</strong>s... dig?"<br />

Cool Burnin' W<strong>it</strong>h The Chet Baker Quintet (1965)<br />

The dry nylon landscape stretches out, an orange and purple blur.<br />

Air crackles w<strong>it</strong>h atatic. Hairball tumbleweeds. Nail clippings, some sort<br />

of fur...Brown bottles, cottonballs, a blackened spoon.<br />

Scrape of eyeball on motel carpet. Brown afternoon light. Light<br />

sucked from the room, out through dust-colored curtains...<br />

The dry tongue searches for moisture. Skull a pulse of hard pain.<br />

The sink, get to the fucken sink... Scudding water into his gaping mouth<br />

triggers splintering teeth... ACHE…Water that tastes like chalk, like<br />

blood…<br />

"Aw, sh<strong>it</strong>, fuck sh<strong>it</strong>..."<br />

Chet Baker clicks the overhead light, shaves w<strong>it</strong>h trembling longfingered<br />

hands, squinting into the foxed mirror. Ravines run vertically<br />

down the ruined cliff of his face. 'Craggy good looks' - ahem yes, takes<br />

some fuckin' maintenance these days...<br />

A stay-pressed button-down shirt from the cardboard su<strong>it</strong>case.<br />

Pomade for the unwashed hair. Good as fuckin' new.<br />

Now, just a quick l<strong>it</strong>tle taste while stocks last, then maybe have me<br />

a good look thru the old address book...<br />

"To absent friends..."<br />

* * *<br />

The puppies thrashed and yelped w<strong>it</strong>h exc<strong>it</strong>ement. YAP YAP YAP<br />

YAP! Their l<strong>it</strong>tle bellies slapping and sk<strong>it</strong>tering on the parquet floor. Paws<br />

slipping out from under them as they scurried towards the telephone<br />

table, where they clamboured ontop of eachother, wheezing and panting<br />

and yelping until Mrs. Desmond lifted the receiver.<br />

"Hello, Desmond residence..."<br />

A voice like desert wind, husks of breath almost devoid of life, a<br />

dry sucking sound came from the earpiece. A vampyric rustling, almost a<br />

death rattle...but urgent and alive w<strong>it</strong>h suppressed need. She almost had<br />

to hold the phone at arms length w<strong>it</strong>h revulsion.<br />

"No, Mister Baker, I'm afraid Paul isn't here right now. No, I don't<br />

know when he will be back, he's out on tour at the moment. Yes, I'll be<br />

sure he gets your message..."

Not given to strong drink, she nevertheless had to pour herself a<br />

gin & tonic and sat hugging herself by the dogbasket until long after the<br />

dachshund pups had fallen back to sleep.<br />

Chet Baker: Hauntingly beautiful, perpetually troubled. Baker<br />

wore his dark su<strong>it</strong>s and wh<strong>it</strong>e shirts w<strong>it</strong>h an insouciance only a jazz<br />

legend could muster.<br />

1941 Martin trumpet.<br />

“Basically, all the great trumpet players, Miles, Chet, all played a<br />

particular brand of trumpet called a Martin, made in Wisconsin.”<br />

Now that we are going on a trip...<br />

“If my decomposing carcass helps nourish the roots of a juniper<br />

tree or the wings of a vulture – that is immortal<strong>it</strong>y enough for me. And as<br />

much as anyone deserves.”<br />

He simply fell out of the window…<br />

An automobile is just a tool<br />

Chet Baker like a shadow passing through the bright afternoon.<br />

Yellow flowers by the roadside. Haze of dust. Elbowing aside the<br />

Mexicans as he moves through the market stalls. Finally selecting a large<br />

& already battered-looking straw hat. A few scattered pesos, eyes<br />

invisible behind shades.<br />

“YOU ARE NOW LEAVING NEW MEXICO – ‘LAND OF<br />

ENCHANTMENT’ ”<br />

Dead roadsigns l<strong>it</strong>ter the desert. Cracked lips whistling an old<br />

tune: “Where The Columbines Grow…”<br />

Yeah, I'll remember that one, maybe we can work up a head<br />

arrangement. These old frontier songs go down real good w<strong>it</strong>h the<br />

social<strong>it</strong>es. Desmond'll play <strong>it</strong> real purty.<br />

H<strong>it</strong> the interstate up into Colorado, route 25 all the way passing<br />

thru all these dead joints, vultures, buzzards... billboards &<br />

truckstops...whenever he saw a billboard he wanted to tear the son of a<br />

b<strong>it</strong>ch down - specially when <strong>it</strong> had his own face on <strong>it</strong>...<br />

Friday, February 11, 2005<br />

Dear Mr. Braxton,<br />

I have had the good fortune to chance upon your web-log, and<br />

would like to take this opportun<strong>it</strong>y to share w<strong>it</strong>h your readers some<br />

reminiscences of my own.<br />

In the summer of 1958 I found myself in the strange pos<strong>it</strong>ion of<br />

being Tour-Manager to a group of vis<strong>it</strong>ing American jazzmen, a job for<br />

which I was not remotely qualified. It happened that my dear friend Max<br />

Harrison, the noted jazz cr<strong>it</strong>ic, was to have chaperoned the entourage,<br />

but was taken rather ill at the last moment.

So <strong>it</strong> was, then, one warm July evening that I found myself on the<br />

quayside at Harwich wa<strong>it</strong>ing to meet the boat from Holland.<br />

As the vessel hove into sight through the gathering mist, I felt a<br />

sudden and unseasonal chill which penetrated to my very core. But even<br />

at that early hour of the night, the sound of merriment and the tinkling<br />

of glasses preceded the boat across the water.<br />

Soon my charges were assembled in the terminal, and a hearty<br />

band of fellows they seemed to me. Eugene Wright, dwarfed by his<br />

double bass; Morello, the jester of the bunch w<strong>it</strong>h a team of porters to<br />

carry his jumble of percussion <strong>it</strong>ems to the charabanc; Mr. Brubeck and<br />

Mr Desmond, both the very ep<strong>it</strong>ome of elegance and New World charm,<br />

although I found the bright check of their matching sports-jackets to be<br />

rather dazzling in the low sun. Cordial introductions were made all<br />

around, and we presently were on our way.<br />

It is not necessary here to give full details of our journey from<br />

Harwich, except to say that for one reason or another we were obliged to<br />

make many unscheduled stops, and by the time we approached the<br />

outskirts of London the hour was qu<strong>it</strong>e late. In view of this <strong>it</strong> was decided<br />

that I should put the band up for the night, rather than navigate through<br />

the infernal London traffic in search of a su<strong>it</strong>able hotel.<br />

When we reached Ponders End, my dear wife Edna was at the door<br />

to greet us and the fine aroma of trad<strong>it</strong>ional English Hot-Pot wafted on<br />

the honeysuckled air.<br />

After some confusion during which Mr.Morello managed to inhale<br />

part of the repast, our guests were shown to the spare room where they<br />

were to spend the night.<br />

I do not care to know what went on behind that door, but I dare<br />

say strong liquor and tobacco were taken in some quant<strong>it</strong>y.<br />

home is the hunter...<br />

'Honey, I'm Home'.<br />

He lugged the su<strong>it</strong>case up the wooden porch steps, brushing aside<br />

the yelping dachshunds, and banging his shin hard on the old rocking<br />

chair.<br />

Inside the k<strong>it</strong>chen the fresh smell of floor polish hung in the air.<br />

The gingham checked curtains fluttered gently. The sun was still high<br />

and a warm golden light spilled through the clean sparkling window<br />

pane.<br />

Mrs. Desmond dropped the bright yellow duster when she saw him<br />

there. 'Paul, Paul, where on earth have you been, I've been so worried.<br />

Heavens Honey, I must have called Mister Brubeck a hundred times, and<br />

you know how he hates to be disturbed at home..'<br />

A slight spark of static from her nylons. Tic-tac of heels on the<br />

parquet floor as she crossed to the icebox.

'Yeah, that motherfucker's worse than a goddam priest…’<br />

She chose to ignore this uncharacteristic outburst. Two dry<br />

martinis appeared on the green formica table.<br />

Paul Desmond eased off his brogues & flexed his toes inside his<br />

argyle socks. A runty sausage dog nuzzled up against his feet. Yeah, I'm<br />

home...<br />

That night they lay in their twin beds in the moonl<strong>it</strong> room, unused<br />

to each-other's company: 'Paul, I'm worried about that smell, <strong>it</strong>'s getting<br />

worse...'<br />

In the k<strong>it</strong>chen the dogs kept sniffing around the su<strong>it</strong>case,<br />

whimpering and scrabbling at the corners.<br />

He was awake before dawn, dragging the goddam case in a trail of<br />

slime and gore out thru the back door, trying not to bump too loudly on<br />

the wooden steps. Okay, get the sonofab<strong>it</strong>ch into the garage.<br />

He took the yard rake and covered his tracks. In the house the<br />

dogs were already licking at the bloody seepage. The floor would have to<br />

be washed and polished again, that's for sure.<br />

they attempt to represent complex philosophical truths<br />

“These our actors,<br />

As I foretold you, were all spir<strong>it</strong>s and<br />

Are melted into air, into thin air:<br />

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,<br />

The cloud-capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces,<br />

The solemn temples, the great globe <strong>it</strong>self,<br />

Yea, all which <strong>it</strong> inher<strong>it</strong>, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,<br />

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff<br />

As dreams are made on, and our l<strong>it</strong>tle life<br />

Is rounded w<strong>it</strong>h a sleep.”<br />

'VIDEO CAMERAS ARE IN OPERATION IN THIS AREA'<br />

||¬|`\`_---------_*<br />

ARCHIVE MATERIAL, source unknown<br />

they have never once met. they were once at the same party. at<br />

this point they both had moustaches. miles davis was cajoling cecil<br />

saying "you're a wh<strong>it</strong>e motherflipper cecil, all you play is goddam<br />

motherflippin wh<strong>it</strong>e classical crap. you says <strong>it</strong>'s the blues but <strong>it</strong> ain't."<br />

apparently cecil got on the piano and was joined by mary lou williams<br />

and they played some very down home church music. paul desmond who<br />

was there having just given anthony braxton some saxophone playing<br />

tips jumped up all exc<strong>it</strong>ed and challenged cecil to play some monk. cecil<br />

taylor got very enthused, started sayin "if i'm gonna play monk the<br />

goddam piano has to be jammed in the k<strong>it</strong>chen doorway." so they all<br />

start humping this grand piano out of the study into the k<strong>it</strong>chen doorway<br />

and indeed cecil did do some very nice rend<strong>it</strong>ions of monk tunes. then he<br />

gets up, and climbs out the window, and down the fire escape just as<br />

ornette walks in the front door. this is the closest these two out cats ever<br />

came to meeting. also out of this party came a life long friendship<br />

between braxton and desmond, both of whom, as <strong>it</strong> happens, shared a<br />

love for sausage dogs. and of course the cecil mary lou duet album. but<br />

what did ornette get out of the whole thing? "sweet f.a. man. story of my<br />

goddam life." were ornette's words.

An Appreciation of Sergey Kuryokhin: On the<br />

Occasion of a Reissue of Some Combinations<br />

of Fingers and Passion<br />

By Seth Watter<br />

The philosopher Didi-Huberman wr<strong>it</strong>es of hysteria that <strong>it</strong> is “a<br />

thousand forms, in none.” All the attempts of Professor Charcot and his<br />

colleagues at the Salpêtrière to photograph hysterical women, in the<br />

name of objective science, were doomed to fail; because a still image of a<br />

hysteric is essentially only the picture of an interm<strong>it</strong>tence, a gap between<br />

the phases of a hysterical attack. The actual phenomenon is an<br />

unpredictable unfolding of contradictory states, agony, jouissance, terror,<br />

hope, dementia, insight...<br />

So <strong>it</strong> is w<strong>it</strong>h the work of Sergey Kuryokhin, whose music flirts w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

hysteria. And so <strong>it</strong> is w<strong>it</strong>h the wr<strong>it</strong>er who attempts to describe this<br />

music, condemned to record in words only interm<strong>it</strong>tences: for the real<br />

substance of Kuryokhin’s art is the trans<strong>it</strong>ion from one mode to another,<br />

each style in isolation telling us nothing. What is being told is the story<br />

of an instrument, the piano, and <strong>it</strong>s circu<strong>it</strong>ous route between past and<br />

future.<br />

The distant past (the 19 th century)—an illustrious history of<br />

composers, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, all bourgeois,

aristocrats, relics of feudalism. The recent past (the revolution, Stalin,<br />

the Cold War)—a Soviet campaign to renew interest in popular folk<br />

forms, music of the rural poor, a proletarian music. The present, the<br />

time of Kuryokhin’s matur<strong>it</strong>y (1981-1996)—Glasnost, Perestroika, the<br />

loosening of cultural oppression and renewed trade w<strong>it</strong>h the Western<br />

world, the rapid deterioration of the USSR as a world power; which also<br />

meant a renewed interest in jazz, a music suppressed by government on<br />

and off since <strong>it</strong>s formative years. The future—a reconciliation of the<br />

different phases of Russian art, a music both national and international,<br />

structured and improvised, populist and avant-garde, a music recklessly<br />

tossed into the arena of world culture.<br />

Some Combinations of Fingers and Passion (1991) reflects<br />

something of this matrix. How much, I am unsure; but certainly <strong>it</strong> is one<br />

of the late Soviet Union’s greatest achievements. And <strong>it</strong> emerged, joyous,<br />

exuberant, august and consummative, at the same historical moment <strong>it</strong>s<br />

motherland was on the precipice of a great collapse and dissolution. “A<br />

poet’s speech begins a great way off… The eclipses of poets are not<br />

foretold in the calendar” (Tsvetaeva). What seems inopportune may be<br />

the blessing of foresight.<br />

In a recent article (Signal to Noise, no. 56), I wrote the following:<br />

***<br />

Contradiction is at the heart of Kuryokhin’s career; <strong>it</strong> is one of the<br />

hallmarks of his genius. Crudely speaking, these contradictions number<br />

among themselves several binaries: constraint/freedom,<br />

trad<strong>it</strong>ion/progress, affectation/spontane<strong>it</strong>y, perhaps even—a<br />

mythological conception of East/West. No musician before or since has<br />

so fully embodied the contradictions of the Soviet Union while making<br />

music that so gloriously transcends them, making each pair of<br />

oppos<strong>it</strong>ions fissure in every direction until they explode into pure force.<br />

That was in reference to a concert of 1988 (the recently issued Absolutely<br />

Great!). I think, three years later, the description does not hold qu<strong>it</strong>e so<br />

much water, if only because these heterodox influences on the musician<br />

have finally been condensed into a form so polished as to veil the<br />

workmanship from which <strong>it</strong> was painstakingly crafted. The pianist does<br />

not want postmodern distanciation à la John Zorn; he has become tired<br />

of these myriad forms that do not congeal in the work of art so much as<br />

s<strong>it</strong> side by side under the arb<strong>it</strong>rary banner of the ‘artwork’. There are no<br />

longer abrupt shifts from jazz to opera, from rock to waltz; that sort of<br />

aesthetic violence went out w<strong>it</strong>h the bathwater somewhere en route from<br />

The Ways of Freedom (1981) to Some Combinations; or perhaps <strong>it</strong> was<br />

merely shouldered onto Kuryokhin’s other longterm project, Orkestra<br />

Pop-Mekanika, the multi-media ensemble (music, film, performance,<br />

dance, zoology) which I called “a tireless effort to keep the state of Soviet

culture in a permanent state of carnival.” Some Combinations of Fingers<br />

and Passion is the result of a great purification: not of Kuryokhin’s<br />

prodigious musical vocabulary, but of the antagonisms which previously<br />

gave <strong>it</strong> voice.<br />

Speaking of The Ways of Freedom.—A wonderful first recording,<br />

completely anarcho-destructive of <strong>it</strong>s idiom(s) used as cannon fodder for<br />

blunderbusses of improvised runs, manic tw<strong>it</strong>tering like a possessed<br />

pianola (unclear whether the speed of the recording was changed, the<br />

keys sound so tinny and unreal), supremely gestural, each line a<br />

percussive blow (aimed at who?), the instrument opened up for<br />

dissection and vivisection—l<strong>it</strong>erally!—slapping and bruising the insides,<br />

playing all <strong>it</strong>s hammers, rollers, strings, springs—pounding away in the<br />

very joy of destruction! (Joe Milazzo of One Final Note: “the sound of a<br />

young man, reared in a very particular trad<strong>it</strong>ion of instrumental<br />

virtuos<strong>it</strong>y, discovering and delighting in his powers of musical<br />

subversion.”) The music was considered so repugnant to official taste<br />

that <strong>it</strong> was secretly recorded and smuggled to England as the inaugural<br />

release of producer Leo Feigin’s eponymous label.<br />

Is <strong>it</strong> jazz? Underneath all the obfuscating factors, something of<br />

that art form remains. It is not often that jazz shows <strong>it</strong>self naked and<br />

unabashed in Kuryokhin’s music (though he did briefly tackle Joplin’s<br />

“Maple Leaf Rag” in 1984). It bears repeating, though, that anyone<br />

playing jazz in Russia would be implicated in a complicated legacy. “The<br />

Music of the Gross” (Gorky, 1928):<br />

In the deep stillness resounds the dry knocking of an idiotic hammer.<br />

One, two, three, ten, twenty strokes, and after them, like a mud ball<br />

splashing into clear water, a wild whistle screeches; and then there are<br />

rumblings, wails and howls like the smarting of a metal pig, the shriek of<br />

a donkey, or the amorous croaking of a monstrous frog. This insulting<br />

chaos of insan<strong>it</strong>y pulses to a throbbing rhythm. Listening for a few<br />

minutes to these wails, one involuntarily imagines an orchestra of<br />

sexually driven madmen conducted by a man-stallion brandishing a<br />

huge gen<strong>it</strong>al member.<br />

(A film made around this time, Taxi Blues [Lungin, 1990], helped cement<br />

this association of jazz w<strong>it</strong>h Western decadence; a cab driver who<br />

despises his saxophone-playing neighbor is unashamed to say he misses<br />

the guidance of strong centralized government.)<br />

I think there is reticence in the early Kuryokhin to let jazz be jazz.<br />

Thus he made his music distinctly inhuman, certainly asexual, and<br />

buried his Willie “The Lion” riffs beneath a torrent of atonal thrashingabout<br />

and pointillist abstraction—at loggerheads w<strong>it</strong>h his muse.<br />

***

No such shame on Fingers and Passion; <strong>it</strong> is a sustained<br />

med<strong>it</strong>ation on jazz, not just the harmonics of jazz but the swing and the<br />

feel of jazz. Of course, he couldn’t entirely throw off the her<strong>it</strong>age of<br />

virtuosic Russian artistry, beautiful and baroque; I would say Kuryokhin<br />

never got qu<strong>it</strong>e as earthy as his famous contemporaries, the Ganelin Trio.<br />

But “A Combination of Power and Passion” is one of the few occasions I<br />

know of when he really dug deep into post-war American jazz,<br />

particularly Dave Brubeck’s music—the song’s subt<strong>it</strong>le, after all, is “Blue<br />

Rondo a la Russ”. The West Coast master’s rhythmic innovations must<br />

have left their imprint on Kuryokhin, who had l<strong>it</strong>tle to no respect for<br />

standard jazz time signatures. If on previous recordings the Russian<br />

pianist let his hands compartmentalize the keyboard, ag<strong>it</strong>ating each<br />

other, creating a fractured-hysteric aesthetic, here they work together<br />

w<strong>it</strong>h interlocking melodies and rhythmic counterpoint. All the effort of<br />

moving between styles is so gradual and mellifluous, the listener is<br />

generally unable to pinpoint the decisive moment of transformation. By<br />

varying the pace and delivery of Brubeck’s central theme, gaining<br />

momentum w<strong>it</strong>h a sportsman’s fervor or slowing down in a staccato<br />

articulation, he allows room for new aspects to emerge, aspects which<br />

derail the music and force <strong>it</strong> to ceaselessly evolve. As soon as one has<br />

grasped the theme of a cluster of repet<strong>it</strong>ions, already the music seems<br />

elsewhere. The most sublime improvisations operate in this manner, like

the churning factory of the unconscious, bringing b<strong>it</strong>s and fragments of<br />

memory-experience to light before burying them beneath revisions,<br />

detours, reversals and variations.<br />

The verdict is still out on whether or not God exists; but if he did,<br />

Sergey Kuryokhin would have been his gift to the piano. The half-hour<br />

“Combination of Passion and Feelings” which begins the album is the<br />

kind of declamation orators only dream of, a tour-de-force as muscular<br />

as a Cossack, delicate and pastoral like a wheat field. There is love,<br />

terror, sentiment, festiv<strong>it</strong>y, vertigo, a whole spectrum of emotions on<br />

display w<strong>it</strong>hin this performance. Yet to isolate <strong>it</strong>s phases, to hold them<br />

up as illustrations of a musical lexicon, would destroy what makes <strong>it</strong> so<br />

fascinating, which is the dissolving of one into the other: the process, the<br />

passing-through.<br />

“A Combination of Hands and Feet” betrays the artist’s penchant<br />

for humor. He had a b<strong>it</strong>ing w<strong>it</strong>, but is mostly remembered for a playful<br />

jackdaw mental<strong>it</strong>y. The brand of slobbery he kept in abeyance w<strong>it</strong>h his<br />

hands more often than not came to fru<strong>it</strong>ion through the voice. Not that<br />

the pianist sings: one is more likely to distinguish gurgles, cries,<br />

squawks or whistles. The absurd<strong>it</strong>y of matching such serious music<br />

w<strong>it</strong>h these shrill aleatorics is not unlike the solemn<strong>it</strong>y of Wile E. Coyote<br />

crushed beneath another russet-colored boulder. “Hands and Feet”,<br />

part-ballad, part-waltz, is the closest he comes to genuine tenderness—<br />

which is never w<strong>it</strong>hout a wink.<br />

“A Combination of Boogie and Woogie” is the most straightforward<br />

piece Kuryokhin ever performed as a solo artist, playing in the two-beat<br />

style of American piano giants James P. Johnson, Luckey Roberts and<br />

Meade Lewis. It’s close to gutbucket, but specifically Russian w<strong>it</strong>h <strong>it</strong>s<br />

sense of high drama and capac<strong>it</strong>y for florid embellishment. Even if <strong>it</strong><br />

isn’t qu<strong>it</strong>e the barrelhouse, <strong>it</strong> makes good on the promise of <strong>it</strong>s t<strong>it</strong>le; for<br />

once, there is reverence on the performer’s part for the standard beat,<br />

and as anyone who likes a good boogie-woogie knows, that striding<br />

rhythm is simply unstoppable.<br />

Poets inv<strong>it</strong>e us to dream, wr<strong>it</strong>es Bachelard. One says there are<br />

moonbeams in the linen closet; Reason sees through this logical aporia,<br />

but the imagination continues to be stimulated, carried aloft to new<br />

heights. Kuryokhin’s reverie was one in which East and West were not<br />

only un<strong>it</strong>ed, but had lost all meaning: a daydream of a distant future, or<br />

a distant impossible.

GENDER & MUSIC: 'IN OUR DIFFERENT<br />

RHYTHMS TOGETHER'<br />

By Maggie Nicols<br />

Maybe one day, there will no longer be the need for special features<br />

on gender; a post Patriarchal Cap<strong>it</strong>alist society will experience genuine<br />

divers<strong>it</strong>y & humankind's multidimensional difference will be what unifies<br />

us. Until then, I'm happy to grapple w<strong>it</strong>h the contradictions of gender &<br />

music in our time.<br />

Is there such a thing, outside cultural cond<strong>it</strong>ioning, as feminine or<br />

masculine music? I can only wr<strong>it</strong>e from the lim<strong>it</strong>ed perspective of history,<br />

personal pol<strong>it</strong>ical experience & the times we live in now.<br />

So many of my most precious musical moments are shared w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

other women now that sometimes I forget what <strong>it</strong> was like before the<br />

women's liberation movement, when meaning & value was defined<br />

predominantly by men. L<strong>it</strong>erature, music, religion, pol<strong>it</strong>ics, you name <strong>it</strong>;<br />

men battled ideas amongst themselves & women were mainly their<br />

muses, an influence behind the scenes: “behind every great man,” etc.<br />

When I first started listening to jazz, I naively believed that men<br />

were more biologically su<strong>it</strong>ed to playing instruments. It was what I saw;<br />

female singers & male instrumentalists. The pop music I listened &<br />

danced to; soul, rock 'n roll, all the same. Of course there were also male<br />

singers in all those musics but very few female instrumentalists. It was a<br />

few years before I saw saxophonist Vi Redd down Ronnie Scott's jazz club<br />

in Gerard Street. Even then, <strong>it</strong> was said she played like a man.<br />

I yearned to be part of the wonderful music I heard. I was in love<br />

w<strong>it</strong>h music of all kinds but particularly jazz. Unfortunately many male<br />

musicians mistook my love of music for a willingness to be manipulated<br />

or even coerced into giving them sexual favours. Male acceptance &<br />

approval was everything to me which left me vulnerable to my own<br />

romantic notions about their beautiful souls & a prey to casual sexism. I<br />

was sweet sixteen & hungry to be a musician, which, given what I knew,<br />

meant being a singer. I got my first break singing in a strip club & later<br />

was taken under the wing of the brilliant pioneer of bebop in Br<strong>it</strong>ain,<br />

trumpeter & pianist Dennis Rose, who played in North London pubs.<br />

In the jazz world there was an ambivalence if not downright dislike<br />

towards all but the most established female singers ; an assumption that<br />

they would be rubbish & / or a resentment of their place at the centre of<br />

the audience's attention. However, male front line instrumentalists rarely

came in for the same hostil<strong>it</strong>y even though some of them were perfectly<br />

capable of completely ignoring their supporting rhythm sections when<br />

they took a solo.<br />

My need to be accepted as a bona fide pract<strong>it</strong>ioner of a music that<br />

moved & inspired me so profoundly was probably one of the major if<br />

unconscious driving forces behind my developing my voice as an<br />

instrument. It was also intensive listening to a huge divers<strong>it</strong>y of<br />

brilliantly expressive instrumentalists even if they were all male.<br />

Dennis started me on the road to leg<strong>it</strong>imacy as a musician.<br />

Through my work w<strong>it</strong>h him I got to sing w<strong>it</strong>h other musicians & then<br />

there came a time when I basked in their praise & approval. I was better<br />

than those other 'chick singers'; my low self esteem fed a feeling of false<br />

superior<strong>it</strong>y to my singing sisters.<br />

Later, as I grew in confidence, I occasionally took delight in going<br />

along to jam sessions where I wasn't known & seeing the conspiratorial<br />

rolled eyes & the low expectations of a female singer turn to respect &<br />

amazement once I started singing.<br />

Confidence is the operative word here cos even now w<strong>it</strong>h all my<br />

experience, I can suddenly feel like I don't deserve to be in the hallowed<br />

company of 'real musicians' (men); can doubt my musicianship & feel<br />

shriveled up & small, especially around musicians who knew me a long<br />

time ago. It doesn't happen so often now but enough to want to do all I<br />

can to support other women starting out. I'm saddened to hear that so<br />

many are still getting a hard time.<br />

There was another man that I learnt a lot from & started singing<br />

w<strong>it</strong>h in 1968 when I was twenty. Drummer & free improvisation<br />

innovator & enabler John Stevens honoured & adored the female voice.<br />

He was one of the first musicians I knew to fully integrate the human<br />

voice into his ensembles; we weren't just occasionally decorative or<br />

floating ethereally on top. We were another equal but distinctive colour in<br />

the overall sound like the difference between a trombone & a trumpet or<br />

gu<strong>it</strong>ar. Even in free improvisation this was radical stuff.<br />

John turned everything upside down for everyone, women & men<br />

alike. He was a pioneer of a collective approach to music which also<br />

liberated individual<strong>it</strong>y. Even in the midst of a profoundly sexist music<br />

scene I have to give cred<strong>it</strong> to those men whose human<strong>it</strong>y sometimes<br />

managed to transcend gender stereotypes and oppression. There were &<br />

are many men who I consider as part of the wonderful extended family of<br />

musicians that I am so blessed to be a part of but for a while, as the only

woman, I had a period where I became 'one of the boys'. Like many other<br />

female musicians, before we met each other, I did a pretty good job of <strong>it</strong>,<br />

raving w<strong>it</strong>h the best of them, & <strong>it</strong> was great cos at least I was respected<br />

as a 'fellow' musician. I still needed that male approval.<br />

Apart from w<strong>it</strong>h singer Julie Tippetts one of my dearest musical<br />

soul mates, & in the revelatory voice workshops I started running in<br />

1969, most of my intimate musical experiences had been w<strong>it</strong>h men. Then<br />

came my exposure to the women's liberation movement in the mid<br />

seventies & everything changed again! After mainly being the only<br />

woman in all male ensembles, I was now immersed in an all female<br />

world. I fell in love w<strong>it</strong>h women. I started to understand that what had<br />

happened to me wasn't just personal, <strong>it</strong> was pol<strong>it</strong>ical. I came out as a<br />

lesbian & I wanted to sing w<strong>it</strong>h other female musicians. The Feminist<br />

Improvising Group was born & although we're in danger of being wr<strong>it</strong>ten<br />

out of history, we had a huge impact on the improvised music scene. We<br />

were loved & hated. We were provocative & perversely diverse in class,<br />

sexual<strong>it</strong>y, race, disabil<strong>it</strong>y & musical background & technique. It was my<br />

first experience of singing w<strong>it</strong>h women instrumentalists & <strong>it</strong> was<br />

wonderful.<br />

We didn't set out to call ourselves FIG but when I got us our first<br />

gig at a 'Music for Socialism' event, as the Women's Improvising Group,<br />

the leaflets came out w<strong>it</strong>h the 'F' word & we took that name on board &<br />

really ran w<strong>it</strong>h <strong>it</strong>! I don't think the organisers realised what they'd<br />

unleashed. We rose to the occasion in ways which both delighted &<br />

threatened.

Above: Photograph by Valerie Wilmer of the first ever gig by The Feminist Improvising<br />

Group, at a ‘Music For Socialism’ event. Corine Liensol, trumpet, Lindsay Cooper bassoon/<br />

saxes, Nicols in the wig, Georgie Born cello & Cathy Williams piano.<br />

The difference that our gender made to me was in the intimacy we<br />

shared before & after as well as during the music. It was in the heady<br />

early days of sisterhood before the inev<strong>it</strong>able realisation that ident<strong>it</strong>y also<br />

contains difference. We were discovering our shared experience of<br />

isolation & discrimination as women in a male dominated world. We were<br />

anarchic & unapologetic about overturning many of the assumptions<br />

about technique. In the beginning <strong>it</strong> was an open pool of improvisers<br />

open to all women, mixed abil<strong>it</strong>y in the conventional sense but each<br />

woman crucial to the overall social virtuos<strong>it</strong>y that our performances<br />

expressed. It was truly liberating to stop worrying, for a while at least,<br />

about what men thought of us. We laughed when over & over we were<br />

asked 'why only women'? as if <strong>it</strong> had escaped the notice of the various<br />

questioners that the major<strong>it</strong>y of ensembles were all male. The listening,<br />

the interaction, the humour, the pol<strong>it</strong>ics, the hanging out. I was finally<br />

one of the women not one of the boys.<br />

FIG opened the door into a whole new world of creative<br />

empowerment & many of us went on to play w<strong>it</strong>h each other in different<br />

combinations & still do to this day. Corine Liensol & I started<br />

'Contradictions' w<strong>it</strong>h Irene Schweizer & dancer Roberta Garrison which I<br />

later developed as an open women's workshop performance group,<br />

involving both improvised & wr<strong>it</strong>ten music, theatre, visuals & dance.<br />

Irene Schweizer founded E.W.I.G (European Women's Group) which<br />

brought in new women like bassist Joelle Leandre & singer Annick<br />

Nozati. One of my favour<strong>it</strong>e group experiences was the first women's<br />

improvised music festival 'Canaille' organised by Dutch trombonist Anne<br />

Marie Roelofs (also an ex FIG member) in Frankfurt. We played in<br />

different combinations & the enthusiasm for each group as we cheered<br />

each other proudly from the side of the stage, was totally uplifting &<br />

everyone excelled even more because of <strong>it</strong>; great music & inspired<br />

performances.<br />

Women playing together & promoting each other against all the<br />

odds brought on the era of more mixed gender groups. I remember cellist<br />

Martin Altena saying how much he preferred playing in groups that were<br />

not exclusively male. The joy I experience when surrendering to the Muse<br />

& trusting myself, the music, the other musicians & each unfolding<br />

moment, happens w<strong>it</strong>h men too but <strong>it</strong> happens more often w<strong>it</strong>h women<br />

or when there are other women present (Maybe my gender influences the<br />

music even when I'm the only woman in the group).

I have just come back from a wonderful experience singing w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

trombonist Gail Brand & a Belgian pianist Marjolaine Charbin that Gail<br />

& I had never met before. We did two gigs - the first one was sheer magic,<br />

a multiplic<strong>it</strong>y of twists & turns. There was a free flow of different &<br />

sometimes simultaneously different dynamics a kind of musical multi<br />

orgasmic multi- tasking. A singer called Martha in the audience said<br />

listening to us as women was different to listening to men, not better,<br />

different.<br />

The second gig was harder because of a grim venue l<strong>it</strong>erally divided<br />

in two by a concrete wall. The music was still strong but constructed<br />

more of struggle rather than trust & <strong>it</strong> was great to be able to share our<br />

feelings about the challenging personal processes we'd just gone<br />

through; less analytical than some discussions I've had or read about the<br />

music but no less insightful & certainly less divisive.<br />

There is a deliriously divine combination of sens<strong>it</strong>iv<strong>it</strong>y & anarchic<br />

wildness I experience w<strong>it</strong>h women when we let ourselves be fearless & let<br />

go of needing to prove ourselves in a still predominantly male music<br />

scene. Is <strong>it</strong> a socialised abil<strong>it</strong>y to surrender to flow & wander & meander<br />

that is harder for men who are maybe more socialised to stay in control?<br />

I cannot generalise too much about gender & music though<br />

because there are men who can be possessed by the music & women<br />

who put up barriers, but in my experience those multidimensional<br />

moods that I love so much in free improvisation are something I<br />

associate most w<strong>it</strong>h all the wonderful women I work w<strong>it</strong>h. Even in bands<br />

where we play tunes, there is a particular dynamic in rehearsals that<br />

makes me feel easier in my skin when I work w<strong>it</strong>h women or at least w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

men that love & respect women's presence & musicianship.<br />

There was one group of male musicians however where I found a<br />

similar openness & freshness; the improvisers I met in the former DDR<br />

(East Germany). They hadn't been overdosed w<strong>it</strong>h the Western stimuli<br />

that had made many of our male artists jaded & cynical & striving to<br />

come up w<strong>it</strong>h ever cleverer concepts. Although due to different<br />

circumstances, the East German musicians, like women, had not been a<br />

major part of the Western music scene, so shared a similar sense of<br />

adventure & exploring new terr<strong>it</strong>ory that can come from being excluded.<br />

When I heard gu<strong>it</strong>arist Joe Sachse & trombonist Hanes Bauer for the<br />

first time I felt like I was enjoying a thriller. I was on the edge of my seat.<br />

It was not stylistic, <strong>it</strong> could go anywhere.<br />

I've noticed that certain male musicians & some of the female<br />

musicians who associate w<strong>it</strong>h them often identify themselves w<strong>it</strong>h one

particular concept or approach –minimalism, deliberately contrasting, etc<br />

– whereas women de-ideologised go where they please. Both have their<br />

strengths & weaknesses but I prefer the open ended approach unless <strong>it</strong>'s<br />

a workshop or I'm exploring freedom through specific pieces which<br />

in<strong>it</strong>ially lim<strong>it</strong> or focus the attention in a particular direction like some of<br />

John Stevens' pieces do.<br />

Women are known for multi-tasking, men for single-minded focus.<br />

Are both genders capable of e<strong>it</strong>her? Yes, surely in the music we can all<br />

shape shift & focus. In the end, let <strong>it</strong> be down to preference rather than<br />

gender.<br />

For me, free improvisation still promises the most freedom from<br />

gender biased lim<strong>it</strong>ations; women lead & focus as well as follow &<br />

surrender & vice versa for men, but no-one is a permanent leader or<br />

follower. This is certainly the case w<strong>it</strong>h the Gathering which I started<br />

hosting twenty years ago. It meets weekly in London & monthly in West<br />

Wales & has recently started in Liverpool.<br />

“The Gathering is a space, place and time where we can build up<br />

confidence in our creativ<strong>it</strong>y; where we can s<strong>it</strong> in silence, sing, play an<br />

instrument, draw, be poetic; prophetic; we could talk in tongues, talk to<br />

each other, to ourselves, talk to voices. We can listen, make sounds;<br />

melodies and noise, soft and loud; leave space, fill <strong>it</strong> up; explore rhythm<br />

and time, chaos and rhyme; lullabies and laments; shyly and boldly be in<br />

our different rhythms together.” 1<br />

I believe that men who associate w<strong>it</strong>h & are willing to learn from women<br />

as we have from men for so long, are discovering new ways to express<br />

their creativ<strong>it</strong>y. Ultimately, the mix of gender, culture, race, class, age &<br />

different abil<strong>it</strong>ies can enthrall & liberate us all.<br />

1 http://www.maggienicols.com/id13.html

YOUTUBE WATCH<br />

Tania Chen/ Shabaka Hutchings/ Mark Sanders<br />

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hmdotrl7AWM<br />

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8zeOe9hDs-I<br />

This performance was filmed live by Helen Petts at one of John<br />

Russell’s monthly Mopomoso nights at The Vortex in London (see<br />

www.mopomoso.com and http://www.youtube.com/user/helentonic).<br />

Shabaka Hutchings (pictured above), a truly fine player who was briefly<br />

name-checked in the previous issue of this magazine, is here paired w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

pianist Tania Chen (a classically-trained interpreter of Cage and<br />

Feldman, who has studied w<strong>it</strong>h John Tilbury) and veteran drummer<br />

Mark Sanders. The music begins quietly, gradually swelling from the<br />

silence as the trio feel their way, cautiously echoing each-other’s<br />

instrumental lines. At 6:41, when some melodic agreement/ concord/<br />

coming-together is reached between Chen and Hutchings, the silence is<br />

not allowed to roll to cessation, to applause and the appearance of a false<br />

‘conclusion’. Rather, Chen launches into a monologue – solo<br />

extrapolations on the melodic essence of the previous section – to which<br />

Sanders’ bells impart a further med<strong>it</strong>ative air. Hutchings builds circles

on a recurring pattern, spinning out and out in questioning webs;<br />

threads and journeys, quick forays, a rumbling panic-stricken march<br />

from Sanders’ rumblings and Chen’s lower-keyboard spikiness. When<br />

they reach another silence three minutes into the second clip a similar<br />

transformation could occur – but the applause cuts in and Chen shifts in<br />

her chair, smiling, in some way even embarrassed.<br />

Given the way things start off on the second piece, the direction<br />

seems inev<strong>it</strong>able: Hutchings’ clarinet sets out a kind of off-kilter motorrhythm<br />

momentum into which Chen and Sanders could easily slot. But<br />

when they don’t wholeheartedly join, the turn to quietness is both<br />

unexpected and completely convincing – a hush built from Hutchings’<br />

willingness to gauge the s<strong>it</strong>uation and to respond appropriately, Chen’s<br />

refusal to play except when necessary, and Sanders’ refusal to be the<br />

'up-front' drummer.<br />

Improvisations by one-off groups such as this one may develop in<br />

different ways to those by regular ensembles, which is part of the<br />

exc<strong>it</strong>ement of something like Mopomoso: the necess<strong>it</strong>y of developing new<br />

approaches, of finding ways of working together, leads to a greater sense<br />

of risk, which can spur the musicians on to move outside their comfort<br />

zones. On the other hand, such risk can also generate a tendency<br />

towards pol<strong>it</strong>eness, a laudable desire not to assert oneself over others<br />

creating music that is, in the end, perhaps overly tentative in <strong>it</strong>s<br />

approach. Such p<strong>it</strong>-falls are avoided here, for, while the three musicians<br />

are certainly respectful, paying careful attention to what their trio<br />

partners are doing at any particular moment, they are not afraid to take<br />

their improvisations in unexpected directions, yielding some fine results.<br />

All About Cecil McBee<br />

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=slJX2-cyegQ<br />

The name of bassist Cecil McBee may have inadvertently become<br />

associated w<strong>it</strong>h a leading clothing store in Japan, 1 but <strong>it</strong> seems that his<br />

work as a bassist is still too often unacknowledged by both cr<strong>it</strong>ics and<br />

public. That’s a real shame, because his work on Pharoah Sanders’ early<br />

1970s albums for Impulse Records contains a textural richness and an<br />

emotional depth rarely matched in the more one-dimensional role which<br />

the instrument has had to play in much jazz music, perhaps the finest<br />

instance being his solo feature on ‘Let Us Go Into the House of the Lord’,<br />

from Sanders’ ‘Summun Bukmun Umyun.’ The Sanders recordings also<br />

demonstrated that McBee was perfectly capable of playing in a more<br />

conventional, groove-based role, as attested by the hypnotic rhythmic<br />

interplay w<strong>it</strong>h Stanley Clarke on ‘Black Un<strong>it</strong>y’ and ‘Live at the East.’<br />

1<br />

http://www.audiocasefiles.com/ acf_cases/ 10125-mcbee-v-delica-co-

Continuing to work in the ‘spir<strong>it</strong>ual jazz’ vein that characterized Sanders’<br />

output at this time, he recorded as leader for Strata-East: the varied<br />

‘Mutima’ contained ensemble pieces w<strong>it</strong>h the singer Dee Dee<br />

Bridgewater, as well as a feature for two basses played at once.<br />

The more recent video featured here is a podcast made by the ‘Jazz<br />

Video Guy,’ Bret Primack (http://planetbret.com/): <strong>it</strong> documents the<br />

recording sessions for the album ‘Seraphic Light’ by Coltrane tribute<br />

band Saxophone Summ<strong>it</strong> (Joe Lovano and Dave Liebman, joined by Ravi<br />

Coltrane, who replaces the late Michael Brecker). Focusing on McBee, <strong>it</strong><br />

mixes footage of the group laying down one of his compos<strong>it</strong>ions w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

‘talking-heads’ interviews featuring the other musicians (including fellow<br />

veteran Billy Hart). Perhaps one day someone will make a full-length<br />

feature on McBee: for now, this short video provides an intriguing look at<br />

some of his working methods.<br />

John Klemmer – 20 th Century Blues/Late Evening Prayer<br />

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDTFbG7dHWs<br />

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jxUa5XcwQbU&feature=related<br />

The work for which John Klemmer has become known is not<br />

exactly my cup of tea – he’s one of the principle culpr<strong>it</strong>s responsible for<br />

the growth of the smooth jazz movement – but, like fellow culpr<strong>it</strong> Grover

Washington Jr., he was actually capable of playing some very fine jazz<br />

saxophone when he felt like <strong>it</strong>. He might never have become an<br />

absolutely top-rank musician anyway, but, by lim<strong>it</strong>ing himself to the<br />

unchallenging world of commercial smooth jazz, he ensured that he<br />

wouldn’t even stand the ghost of a chance. Signed up to Impulse Records<br />

in the mid-70s as one of the new wave of young jazzers, he was seen at<br />

once as a firebrand in the Gato Barbieri/post-Coltrane vein, an<br />

experimental musician (through his use of Echoplex – which, ironically<br />

enough, was the tool which turned him to commercialism), and someone<br />

able to connect w<strong>it</strong>h more popular musical trad<strong>it</strong>ions (his very fine, non-<br />

Impulse record ‘Blowin’ Gold’, which features Pete Cosey as a sideman,<br />

contained a cover of Hendrix’ ‘Third Stone from the Sun’). His tone is<br />

hard and steely, and he has a penchant for building his solos up to<br />

passionate squawks – <strong>it</strong>’s a very direct approach, if not as out-there as<br />

Barbieri’s, and you can see why Impulse had high hopes for Klemmer.<br />

Ne<strong>it</strong>her the image nor the picture qual<strong>it</strong>y on these two videos,<br />

recorded at the 1976 Montreux Jazz Festival, is very good (<strong>it</strong>’s clearly<br />

been transferred from an old VHS), but Klemmer has a solid band to<br />

back him up as he opens w<strong>it</strong>h a solo echoplex ballad feature, which<br />

segues into a driving blues built around the dug-in bass-lines and<br />

comping of Cecil McBee, pianist Tom Canning, and drummer Alphone<br />

Mouzon, best known himself for his fusion work. The second clip is a<br />

vamp-oriented track which contains the same exuberant skronking as<br />

‘Blowin’ Gold’, as well as an enthusiastic Mouzon solo.<br />

Lucio Capece and Christian Kesten<br />

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WHg663iQIsc

This is footage of what looks to have been a very focused small<br />

gathering at Labor Sonor, Kule, Berlin, back in December 2006, w<strong>it</strong>h the<br />

musicians s<strong>it</strong>ting in a space that’s barely separate from the audience,<br />

who are w<strong>it</strong>hin touching distance. The atmosphere is one of respectful<br />

openness, and the music <strong>it</strong>self has a similar sense of space w<strong>it</strong>hin <strong>it</strong>,<br />

opening up vistas of silence while at the same time being very intense,<br />

focused, even constricted, claustrophobic in <strong>it</strong>s lim<strong>it</strong>ation of the sound<br />

field to extremely quiet ‘extended techniques.’ In such a context, playing<br />

a conventionally blown note or a recongisable harmonic progression<br />

would come as the biggest shock of all, and <strong>it</strong>’s admirable that such a<br />

radically comm<strong>it</strong>ted approach exists at all, an approach which provides<br />

an intensely absorbing experience. On one level, what we have here is in<br />

some way not ‘real<strong>it</strong>y’ – <strong>it</strong> must take place behind closed doors, in<br />

chambers of quiet – yet at the same time <strong>it</strong> forces a concentration on the<br />

closest details and mechanics of bodily performance and of s<strong>it</strong>uation of<br />

sound, event and gesture in space: in other words, some fundamental<br />

aspects of the human experience.<br />

What does this actually mean in terms of what we can see and<br />

hear in the video clips? Three minutes have gone by and hardly anything<br />

has happened (someone’s mobile phone has unexpectedly gone off, the<br />

loudest sound we’ve heard so far). Capece starts to rotate a violin bow<br />

around the surface of his saxophone bell in a kind of machine rhythm.<br />

Kesten’s hands are clasped between his legs, almost in an att<strong>it</strong>ude of<br />

prayer. He doesn’t sing, he simply breathes audibly. Capece swings a<br />

cardboard tube in circles to make music from the air. Kesten picks up<br />

some tiny plant pots from the floor and rubs them together.<br />

But to go on describing the music in this way wouldn’t do <strong>it</strong><br />

justice, for <strong>it</strong>’s not really concerned w<strong>it</strong>h presenting a narrative sequence<br />

of sound events – at least, not in any developmental sense; although,<br />

given the long periods of silence, even the smallest gesture can assume<br />

great drama, and the music necessarily unfolds along a linear axis,<br />

necessarily exists in unfolding time. Low-qual<strong>it</strong>y video is hardly a<br />

subst<strong>it</strong>ute for being in the same room as the musicians, especially w<strong>it</strong>h<br />

this kind of improvisation, but <strong>it</strong>’s nice to get an extended glimpse at<br />

such an occasion. Just remember to use headphones…

CD REVIEWS INDEX<br />

“Cr<strong>it</strong>icism is always the easiest art.”<br />

- Cornelius Cardew<br />

• AIDA SEVERO – Aida Severo<br />

• ALLEN, CORY – The Fourth Way<br />

• ARGUE, DARCY JAMES – Infernal Machines<br />

• BARNACLED – Charles<br />

• CÔTÉ, MICHEL F./ DONTIGNY, A_ – La Notte Fa<br />

• DIXON, BILL – Tapestries for Small Orchestra<br />