Trotsky - The Revolution Betrayed.pdf - Mehring Books

Trotsky - The Revolution Betrayed.pdf - Mehring Books

Trotsky - The Revolution Betrayed.pdf - Mehring Books

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

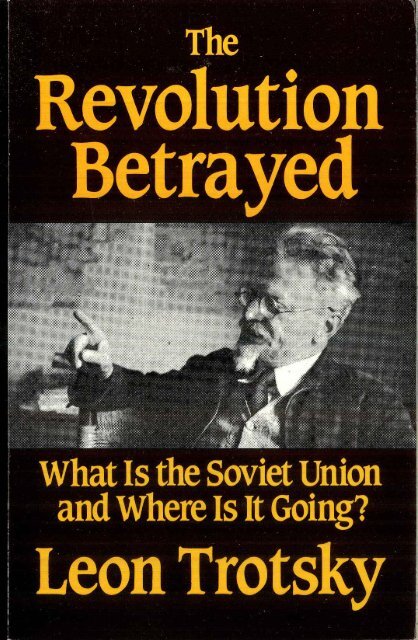

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong>

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong><br />

What Is the Soviet Union<br />

and Where Is It Going?<br />

Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong><br />

Labor Publications, Inc.<br />

Detroit

Originally published in 1937<br />

© 1991 by Labor Publications, Inc.<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

ISBN 0-929087-48-8<br />

Published by Labor Publications, Inc.<br />

PO Box 33023, Detroit, MI 48232<br />

Printed in the United States of America

Note on the Translation<br />

This edition is a revision of the excellent original translation.<br />

We have corrected a few errors, changed the transliteration<br />

of several Russian names according to more modern<br />

usage, and modified some expressions which have become<br />

outdated in the fifty years since the book appeared. In several<br />

cases we have restored paragraph breaks so that they<br />

correspond to the original Russian manuscript. Footnotes<br />

appearing at the bottom of pages are from the original<br />

translation. Additional notes prepared for this edition begin<br />

on page 265.

Contents<br />

Introduction ix<br />

Author's Introduction 1<br />

Chapter One What Has Been Achieved 5<br />

Chapter Two Economic Development and<br />

the Zigzags of the Leadership 19<br />

Chapter Three Socialism and the State 39<br />

Chapter Four <strong>The</strong> Struggle for<br />

Productivity of Labor 57<br />

Chapter Five <strong>The</strong> Soviet <strong>The</strong>rmidor 75<br />

Chapter Six <strong>The</strong> Growth of Inequality<br />

and Social Antagonisms 99<br />

Chapter Seven Family, Youth and Culture 123<br />

Chapter Eight Foreign Policy and the Army 159<br />

Chapter Nine What Is the USSR? 199<br />

Chapter Ten <strong>The</strong> USSR in the Mirror of<br />

the New Constitution 219

viii Contents<br />

Chapter Eleven Whither the Soviet Union? 233<br />

Appendix "Socialism in One Country" 249<br />

Notes 265<br />

Biographical & Historical Glossary 273<br />

Index 313

Introduction<br />

In the annals of political literature, few works have<br />

withstood the test of time so well as Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong>. More than 50 years after its initial<br />

publication, its analysis of the Soviet Union remains unsurpassed.<br />

A single reading of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> will still<br />

yield more knowledge of the structure and dynamics of Soviet<br />

society than would be acquired from a systematic review of<br />

the countless thousands of volumes which bourgeois "Sovietology"<br />

has inflicted on the public over the last few decades.<br />

<strong>The</strong> events of the last five years provide an objective means<br />

of comparing the scientific value of <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s masterpiece of<br />

Marxist analysis to the conformist and pedestrian works of<br />

innumerable stipend-laden academics and prize-winning<br />

journalists. Who among them predicted even after the<br />

accession of Gorbachev to power that the Soviet government<br />

would reject the principle of central planning, repeal all<br />

restrictions on private ownership of the means of production,<br />

proclaim the market to be the highest achievement of<br />

civilization, and seek the complete integration of the USSR<br />

into the economic and political structure of world capitalism?<br />

But as far back as 1936, writing as an isolated political exile<br />

in Norway (from which he was soon to be deported on the<br />

orders of a Social Democratic government), Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong><br />

warned that the policies of the Stalinist regime, far from<br />

having assured the triumph of socialism in the USSR, were<br />

actually preparing the ground for the restoration of capitalism.<br />

It can now be said without fear of contradiction that the<br />

course of events since the launching of perestroika in 1985<br />

ix

Introduction<br />

has to an astonishing degree validated <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s hypothetical<br />

formulation of the process through which the overturn of the<br />

nationalized property forms created on the basis of the<br />

October 1917 <strong>Revolution</strong> might be realized.<br />

<strong>The</strong> point is not merely that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> was<br />

the work of a genius. What sets this book apart from all others<br />

written about the Soviet Union is the analytical method that<br />

its author employed. <strong>Trotsky</strong> was among the greatest<br />

exponents of the materialist dialectic which was, and<br />

remains, the imperishable contribution of Marxism to the<br />

development of human thought. <strong>The</strong> aim of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

<strong>Betrayed</strong> was to uncover the internal contradictions underlying<br />

the evolution of a state that was the product of the<br />

first socialist revolution in world history. Whereas for<br />

bourgeois scholars and journalists the definition of the Soviet<br />

Union as a "socialist state" has generally been the assumed<br />

and unquestioned premise of their works, <strong>Trotsky</strong> rejected<br />

the facile use of the term "socialist" to describe the Soviet<br />

reality. <strong>The</strong> uncritical use of the term, he admonished, served<br />

to obscure rather than illuminate reality. <strong>The</strong> October<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>, he insisted, did no more than lay down the initial<br />

political foundations for the transformation of backward<br />

Russia into a socialist society. Whether or not socialism<br />

finally emerged out of those foundations, and within what<br />

span of time, depended upon a complex interaction of national<br />

and international factors. In any event, maintained <strong>Trotsky</strong>,<br />

contrary to the boasts of the Stalinist regime, socialism —<br />

using the term as it had been traditionally defined in the<br />

lexicon of Marxism — did not at all exist in the USSR.<br />

But if the Soviet Union was not socialist, could it then be<br />

defined as capitalist? <strong>Trotsky</strong> rejected this term as well, for<br />

the October <strong>Revolution</strong> had undoubtedly led to the abolition<br />

of private ownership of the means of production and placed<br />

property in the hands of the workers' state. <strong>The</strong>refore, in<br />

defining the Soviet Union <strong>Trotsky</strong> deliberately eschewed the<br />

use of finished and static categories, such as capitalism and<br />

socialism. Rather, he sought to formulate a concept of the<br />

Soviet Union which reproduced its dynamic features and<br />

indicated the possible forms of their further development.<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> concluded that the Soviet Union was a "transitional"

Introduction xi<br />

society whose character and fate had not yet been decided by<br />

history. If the working class succeeded in overthrowing the<br />

Stalinist regime and, on the basis of Soviet democracy,<br />

regained control of the state, the USSR could still evolve in<br />

the direction of socialism. But if the bureaucracy retained<br />

power and continued to stifle, in the interests of its own<br />

privileged position, the creative possibilities of the nationalized<br />

productive forces and central planning, a catastrophic<br />

relapse into capitalism, ending with the destruction of the<br />

USSR, was also possible.<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> was aware that his "hypothetical definition,"<br />

which projected two diametrically opposed variants of<br />

development for the Soviet Union, would bewilder those<br />

whose thought was guided by the precepts of formal logic.<br />

"<strong>The</strong>y would like," he noted, "categorical formulae: yes —<br />

yes, and no — no." But social reality consists of contradictions<br />

that cannot be comprehended within the rigid framework<br />

of a logical syllogism. "Sociological problems would<br />

certainly be simpler, if social phenomena had always a<br />

finished character. <strong>The</strong>re is nothing more dangerous, however,<br />

than to throw out of reality, for the sake of logical<br />

completeness, elements which today violate your scheme and<br />

tomorrow may wholly overturn it. In our analysis, we have<br />

above all avoided doing violence to a dynamic social formation<br />

which has had no precedent and knows no analogies. <strong>The</strong><br />

scientific task, as well as the political, is not to give a finished<br />

definition to an unfinished process, but to follow all its stages,<br />

separate its progressive from its reactionary tendencies,<br />

expose their mutual relations, foresee possible variants of<br />

development, and find in this foresight a basis for action"<br />

(pp. 216-17).<br />

In the course of a theoretical controversy that was to a large<br />

extent inspired by the analysis presented in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

<strong>Betrayed</strong>, James Burnham argued that materialist dialectics<br />

was not a scientific method of historical and social investigation,<br />

but only a literary device that <strong>Trotsky</strong> employed in the<br />

formulation of striking metaphors. 1<br />

A serious examination of<br />

1 James Burnham (1905-1987), who eventually achieved a degree of<br />

political renown in the United States as an ideological leader of the American

X<br />

Introduction<br />

has to an astonishing degree validated <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s hypothetical<br />

formulation of the process through which the overturn of the<br />

nationalized property forms created on the basis of the<br />

October 1917 <strong>Revolution</strong> might be realized.<br />

<strong>The</strong> point is not merely that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> was<br />

the work of a genius. What sets this book apart from all others<br />

written about the Soviet Union is the analytical method that<br />

its author employed. <strong>Trotsky</strong> was among the greatest<br />

exponents of the materialist dialectic which was, and<br />

remains, the imperishable contribution of Marxism to the<br />

development of human thought. <strong>The</strong> aim of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

<strong>Betrayed</strong> was to uncover the internal contradictions underlying<br />

the evolution of a state that was the product of the<br />

first socialist revolution in world history. Whereas for<br />

bourgeois scholars and journalists the definition of the Soviet<br />

Union as a "socialist state" has generally been the assumed<br />

and unquestioned premise of their works, <strong>Trotsky</strong> rejected<br />

the facile use of the term "socialist" to describe the Soviet<br />

reality. <strong>The</strong> uncritical use of the term, he admonished, served<br />

to obscure rather than illuminate reality. <strong>The</strong> October<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>, he insisted, did no more than lay down the initial<br />

political foundations for the transformation of backward<br />

Russia into a socialist society Whether or not socialism<br />

finally emerged out of those foundations, and within what<br />

span of time, depended upon a complex interaction of national<br />

and international factors. In any event, maintained <strong>Trotsky</strong>,<br />

contrary to the boasts of the Stalinist regime, socialism —<br />

using the term as it had been traditionally defined in the<br />

lexicon of Marxism — did not at all exist in the USSR.<br />

But if the Soviet Union was not socialist, could it then be<br />

defined as capitalist? <strong>Trotsky</strong> rejected this term as well, for<br />

the October <strong>Revolution</strong> had undoubtedly led to the abolition<br />

of private ownership of the means of production and placed<br />

property in the hands of the workers' state. <strong>The</strong>refore, in<br />

defining the Soviet Union <strong>Trotsky</strong> deliberately eschewed the<br />

use of finished and static categories, such as capitalism and<br />

socialism. Rather, he sought to formulate a concept of the<br />

Soviet Union which reproduced its dynamic features and<br />

indicated the possible forms of their further development.<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> concluded that the Soviet Union was a "transitional"

Introduction xi<br />

society whose character and fate had not yet been decided by<br />

history. If the working class succeeded in overthrowing the<br />

Stalinist regime and, on the basis of Soviet democracy,<br />

regained control of the state, the USSR could still evolve in<br />

the direction of socialism. But if the bureaucracy retained<br />

power and continued to stifle, in the interests of its own<br />

privileged position, the creative possibilities of the nationalized<br />

productive forces and central planning, a catastrophic<br />

relapse into capitalism, ending with the destruction of the<br />

USSR, was also possible.<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> was aware that his "hypothetical definition,"<br />

which projected two diametrically opposed variants of<br />

development for the Soviet Union, would bewilder those<br />

whose thought was guided by the precepts of formal logic.<br />

"<strong>The</strong>y would like," he noted, "categorical formulae: yes —<br />

yes, and no — no." But social reality consists of contradictions<br />

that cannot be comprehended within the rigid framework<br />

of a logical syllogism. "Sociological problems would<br />

certainly be simpler, if social phenomena had always a<br />

finished character. <strong>The</strong>re is nothing more dangerous, however,<br />

than to throw out of reality, for the sake of logical<br />

completeness, elements which today violate your scheme and<br />

tomorrow may wholly overturn it. In our analysis, we have<br />

above all avoided doing violence to a dynamic social formation<br />

which has had no precedent and knows no analogies. <strong>The</strong><br />

scientific task, as well as the political, is not to give a finished<br />

definition to an unfinished process, but to follow all its stages,<br />

separate its progressive from its reactionary tendencies,<br />

expose their mutual relations, foresee possible variants of<br />

development, and find in this foresight a basis for action"<br />

(pp. 216-17).<br />

In the course of a theoretical controversy that was to a large<br />

extent inspired by the analysis presented in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

<strong>Betrayed</strong>, James Burnham argued that materialist dialectics<br />

was not a scientific method of historical and social investigation,<br />

but only a literary device that <strong>Trotsky</strong> employed in the<br />

formulation of striking metaphors. 1<br />

A serious examination of<br />

1. James Burnham (1905-1987), who eventually achieved a degree of<br />

political renown in the United States as an ideological leader of the American

xii Introduction<br />

the structure of <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s analysis is sufficient to expose the<br />

shallowness of this criticism. Dialectical logic is not a form of<br />

clever argumentation employed by those who possess a talent<br />

for inventing brilliant, but contrived, paradoxes; it is, rather,<br />

the generalized expression in the domain of thought of the<br />

contradictions which lie at the base of all natural and social<br />

phenomena. <strong>Trotsky</strong> set out to lay bare the antagonistic and<br />

at the same time interdependent economic, social and<br />

political tendencies which determined the movement of Soviet<br />

society.<br />

<strong>The</strong> October <strong>Revolution</strong> was itself the product of the<br />

greatest of all historical paradoxes. <strong>The</strong> first socialist<br />

revolution began in 1917 not in one of the economically<br />

advanced countries of Western Europe and North America,<br />

but in the most backward of the major capitalist countries of<br />

the period — Russia. Within the space of eight astonishing<br />

months, from February to October, the Russian masses<br />

shattered the decrepit feudal institutions of the Romanov<br />

dynasty and, led by the most revolutionary party the world<br />

had ever seen, created a new state form, based on workers'<br />

councils (soviets).<br />

Contrary to the claims of the liberal opponents of Marxism,<br />

the inability of the bourgeoisie to create a viable political<br />

alternative to the tsarist regime stemmed not from the evil<br />

right wing and advocate of a "preemptive" nuclear war against the Soviet<br />

Union, was a socialist in the 1930s and, during the latter half of that decade,<br />

a leading member of the <strong>Trotsky</strong>ist movement As a professor of philosophy<br />

at New York University, his views on logic were greatly influenced by Sidney<br />

Hook For a time Burnham attempted to reconcile his political sympathy for<br />

the views of <strong>Trotsky</strong> with his increasingly hostile attitude toward the<br />

philosophical validity of dialectical materialism But in May 1940, after a<br />

protracted polemical struggle inside the Socialist Workers Party, Burnham<br />

announced his break with Marxism In 1942, he published <strong>The</strong> Managerial<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>, a volume which was greatly acclaimed even though its thesis<br />

was plagiarized from <strong>The</strong> Bureaucratization of the World, a work written by<br />

Bruno Rizzi a decade earlier Burnham moved rapidly to the extreme right<br />

and soon became a political adviser of William Buckley's National Review<br />

Shortly before his death, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by Ronald<br />

Reagan Bumham's political evolution vindicated the warning which he<br />

received from <strong>Trotsky</strong> during the polemic of 1939-40: "Anyone acquainted<br />

with the history of the struggles of tendencies within workers' parties knows<br />

that desertions to the camp of opportunism and even to the camp of bourgeois<br />

reaction began not infrequently with rejection of the dialectic."

Introduction xiii<br />

machinations of the Bolsheviks, but from the historically<br />

belated development of capitalism in Russia. In the "classic"<br />

democratic revolutions of England and France, the bourgeoisie<br />

established its political hegemony in the struggle against<br />

feudalism and for national unification under conditions in<br />

which a proletariat, in the modern sense of the term, either<br />

did not exist or was only in the formative stages of its<br />

development as a distinct social class. In Russia, however, the<br />

democratic struggle unfolded when the social and political<br />

development of the proletariat, created by the rapid growth<br />

of industry in the final decades of the nineteenth century,<br />

already outstripped that of the native bourgeoisie. <strong>The</strong> 1905<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong>, the great "dress rehearsal" for the October<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> twelve years later, saw the eruption of insurrectionary<br />

mass strikes and the emergence of a great soviet in<br />

St. Petersburg (whose chairman was Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>), and<br />

confirmed the dominant role of the working class in the<br />

struggle against the autocracy. <strong>The</strong> upheavals of 1905<br />

convinced the Russian bourgeoisie that it faced in the form<br />

of the socialist proletariat a far more dangerous enemy than<br />

the tsarist autocracy. <strong>The</strong> more the bourgeoisie recognized its<br />

own inability to politically dominate the working class, the<br />

less willing it became to utilize the methods of revolutionary<br />

mass struggle, with its uncertain consequences, against the<br />

old regime.<br />

<strong>The</strong> events of 1917 quickly exposed the political paralysis<br />

of the bourgeoisie. Having played virtually no role in the<br />

downfall of the tsar, the bourgeoisie set up a Provisional<br />

Government that was incapable of implementing a single<br />

radical initiative that would satisfy the demands of the<br />

multimillioned peasantry, let alone the urban proletariat<br />

Moreover, hemmed in by its economic dependence upon the<br />

great imperialist powers and determined to satisfy the<br />

unscrupulous territorial ambitions of the Russian bourgeoisie,<br />

the Provisional Government was committed to<br />

continuing Russia's participation in World War I. This set it<br />

on a collision course with the masses, who were demanding<br />

both an end to the war and the complete destruction of the<br />

feudal legacy in the countryside. <strong>The</strong>se demands were<br />

ultimately realized through the victory of the proletarian

xiv<br />

Introduction<br />

revolution in October under the leadership of the Bolshevik<br />

Party. This paradoxical historical outcome — the consummation<br />

of the democratic revolution through the conquest<br />

of state power by the working class — could not but have the<br />

most far-reaching and unprecedented consequences. Led by<br />

the proletariat, the democratic revolution inevitably assumed<br />

a socialist character: that is, the wiping out of all remnants<br />

of feudalism in the countryside was accompanied by deep<br />

inroads into bourgeois property forms and the socialization<br />

of the means of production.<br />

But there was a heavy price to be paid for the tremendous<br />

historical leap of 1917. <strong>The</strong> circumstances which had<br />

facilitated the conquest of power by the Russian proletariat<br />

created staggering obstacles to the process of socialist<br />

construction in the newly established workers' state. A regime<br />

which had been established on the basis of the most advanced<br />

social program had at its disposal only the most meager<br />

economic resources. Furthermore, the extreme backwardness<br />

of Russian society — the legacy inherited by the Bolshevik<br />

regime from the tsarist past — was compounded by the<br />

economic devastation produced first by the world war and<br />

then by the civil war which erupted in 1918. If considered<br />

only from the standpoint of the situation existing in Russia,<br />

the Bolshevik conquest of power might have appeared to be<br />

a wild and foolhardy adventure. But the calculations of Lenin<br />

and <strong>Trotsky</strong> were based primarily on international, rather<br />

than national, factors. This was noted approvingly by their<br />

greatest contemporary, Rosa Luxemburg, who, despite her<br />

own critical attitude toward certain aspects of their policies,<br />

wrote in 1918: "<strong>The</strong> fate of the revolution in Russia depended<br />

fully upon international events. That the Bolsheviks have<br />

based their policy entirely upon the world proletarian<br />

revolution is the clearest proof of their political farsightedness<br />

and firmness of principle and of the bold scope of their<br />

policies" (Rosa Luxemburg, <strong>The</strong> Russian <strong>Revolution</strong> [Ann<br />

Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961], p. 28). 2<br />

2 <strong>The</strong>re have been countless attempts to counterpose Luxemburg to the<br />

Bolsheviks, tearing her critical observations out of their proper political and<br />

historical context. Permit us, by way of tribute to the memory of this great

Introduction xv<br />

Just as international conditions underlay the eruption of<br />

the Russian <strong>Revolution</strong> and compelled the Bolsheviks to take<br />

power, 3<br />

the potential for socialist construction in Soviet<br />

Russia was inextricably linked to the international class<br />

struggle. Only the victory of the working class in one of the<br />

European centers of world capitalism — Bolshevik hopes<br />

were centered on events in Germany — would place at the<br />

disposal of backward Russia the highly developed economic<br />

and technological resources upon which socialism depends.<br />

For Lenin and <strong>Trotsky</strong>, the Bolshevik conquest of power was<br />

revolutionist, to recall her final judgment on the historical significance of<br />

Bolshevism:<br />

"What is in order is to distinguish the essential from the non-essential, the<br />

kernel from the accidental excrescences in the policies of the Bolsheviks. In<br />

the present period, when we face decisive final struggles in all the world, the<br />

most important problem of socialism was and is the burning question of our<br />

time. It is not a matter of this or that secondary question of tactics, but of the<br />

capacity for action of the proletariat, the strength to act, the will to power of<br />

socialism as such. In this, Lenin and <strong>Trotsky</strong> and their friends were the first,<br />

those who went ahead as an example to the proletariat of the world; they are<br />

still the only ones up to now who can cry with Hutten: 'I have dared!'<br />

"This is the essential and enduring in Bolshevik policy. In this sense theirs<br />

is the immortal historical service of having marched at the head of the<br />

international proletariat with the conquest of political power and the<br />

practical placing of the problem of the realization of socialism, and of having<br />

advanced mightily the settlement of the score between capital and labor in<br />

the entire world. In Russia the problem could only be posed. It could not be<br />

solved in Russia. And in this sense, the future everywhere belongs to<br />

'Bolshevism' " (Luxemburg, <strong>The</strong> Russian <strong>Revolution</strong>, p. 80).<br />

3. That the choice confronting Russia in 1917 was between a proletarian<br />

revolution and a liberal democratic regime modeled on Britain, France or the<br />

United States is a political fantasy. Had the Bolsheviks failed to seize power<br />

in October, the events of 1917 would have in all likelihood concluded with a<br />

successful replay of the counterrevolution which General Kornilov had<br />

attempted in August. <strong>The</strong> survival of capitalism would have been guaranteed,<br />

at least for a period, on the basis of a military dictatorship that would have<br />

smashed the workers' movement. Not only the socialist revolution but the<br />

democratic struggle would have been aborted Russia would have been picked<br />

apart by the imperialist powers upon the conclusion of the world war and<br />

reduced to a state of semicolonial dependency. Its level of economic, social<br />

and cultural development would today resemble that of India, where<br />

hundreds of millions of peasants remain illiterate and exist on the brink of<br />

starvation. We might add that if Lenin and <strong>Trotsky</strong> had behaved in 1917 as<br />

"respectable" social democrats, collaborated with the Provisional Government,<br />

cleared the way for Kornilov's victory and then perished in a fascist<br />

debacle, liberal historians today would no doubt write of them as<br />

sympathetically as they do of Salvador Allende.

xvi<br />

Introduction<br />

only the beginning of the world socialist revolution. Its further<br />

development and completion depended upon the efforts of the<br />

world proletariat. <strong>The</strong> Communist International, in whose<br />

founding the Bolsheviks played the decisive role, was to serve<br />

as the strategical high command of the world struggle against<br />

capitalism.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Bolshevik victory was, indeed, the beginning of a<br />

massive international upsurge of the working class. But in<br />

no other country did there exist a leadership whose political<br />

qualities approached those of the Bolshevik Party. <strong>The</strong> party<br />

of Lenin was the product of years of irreconcilable theoretical<br />

struggle against every current of opportunism in the Russian<br />

workers' movement. <strong>The</strong> significance of the political divisions<br />

within the socialist tendencies existing in Russia and<br />

internationally in 1917 would not have been so clearly defined<br />

had it not been for Lenin's previous labors. <strong>The</strong> split between<br />

Bolshevism and Menshevism in 1903 anticipated by more<br />

than a decade the split in the Second International produced<br />

by the outbreak of the world war in 1914. Lenin's differentiation<br />

between Marxism and all forms of petty-bourgeois<br />

opportunism made possible the fruitful political struggle<br />

waged by the Bolsheviks in 1917 against the reformist<br />

(Menshevik) allies of the bourgeois Provisional Government.<br />

Even in Germany, no such preparation had preceded the<br />

outbreak of revolutionary struggles. <strong>The</strong>re, the decisive<br />

organizational break with the opportunists and the founding<br />

of the Communist Party took place some six weeks after the<br />

outbreak of the November 1918 revolution. And only two<br />

weeks later, on January 15, 1919, the murder of Luxemburg<br />

and Liebknecht, with the behind-the-scene approval of the<br />

Social Democratic government, deprived the German working<br />

class of its finest leaders. Between 1919 and 1923, the<br />

working class suffered a series of major defeats — in<br />

Hungary, Italy, Estonia, Bulgaria and, worst of all, in<br />

Germany. In each case the cause of the defeat lay in the<br />

treachery of the old Social Democratic parties, which still<br />

commanded the support of a significant section of the working<br />

class, and the political immaturity of the new Communist<br />

organizations.

Introduction xvii<br />

<strong>The</strong> prolongation of the political and economic isolation of<br />

the Soviet Union was to have unforeseen and tragic<br />

consequences. Though the state created by the first workers'<br />

revolution did not collapse, it began to degenerate. While the<br />

belated development of capitalism in Russia had made<br />

possible the creation of the Soviet state, the unexpected delay<br />

in the victorious development of the world socialist revolution<br />

was the principal cause of its degeneration. <strong>The</strong> form assumed<br />

by that degeneration was the massive growth of the<br />

bureaucracy in the apparatus of the Soviet state and the<br />

Bolshevik Party and the extraordinary concentration of power<br />

in its hands.<br />

Disdaining historical subjectivism, which replaces the<br />

analysis of social processes with speculation about personal<br />

and psychological motivations, <strong>Trotsky</strong> demonstrated that<br />

the malignant growth of bureaucracy, culminating in the<br />

totalitarian regime of Stalin, was rooted in material contradictions<br />

specific to a workers' state established in a backward<br />

country. From the standpoint of its property forms, the Soviet<br />

state was socialist. But the full and equal satisfaction of the<br />

material needs of all members of society could not even be<br />

contemplated in the backward, impoverished and faminestricken<br />

conditions of Soviet Russia. <strong>The</strong> distribution of goods,<br />

under the supervision of the state, continued to be carried<br />

out with a capitalist measure of value and therefore<br />

unequally. That this inequality — or, what is the same thing,<br />

privileges for a minority — was, at least initially, necessary<br />

for the functioning of the state-controlled economy did not<br />

alter the fact that this mode of distribution remained<br />

bourgeois in character.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Soviet regime expressed the tension between these two<br />

antagonistic functions of the workers' state: defending social<br />

property in the means of production while at the same time<br />

supervising bourgeois methods of distribution and therefore<br />

defending the privileges of a minority. <strong>The</strong> bureaucracy arose<br />

on the basis of this contradiction: "If for the defense of<br />

socialized property against bourgeois counterrevolution a<br />

'state of armed workers' was fully adequate, it was a very<br />

different matter to regulate inequalities in the sphere of<br />

consumption. Those deprived of privileges are not inclined to

xviii<br />

Introduction<br />

create and defend them. <strong>The</strong> majority cannot concern itself<br />

with the privileges of the minority. For the defense of<br />

Tbourgeois law* the workers' state was compelled to create a<br />

'bourgeois' type of instrument, that is, the same old gendarme,<br />

although in a new uniform" (p. 47).<br />

<strong>The</strong> bureaucracy, <strong>Trotsky</strong> explained, functioned as a social<br />

"gendarme," the policeman of inequality:<br />

"We have thus taken the first step toward understanding<br />

the fundamental contradiction between Bolshevik program<br />

and Soviet reality. If the state does not die away, but grows<br />

more and more despotic, if the plenipotentiaries of the<br />

working class become bureaucratized, and the bureaucracy<br />

rises above the new society, this is not for some secondary<br />

reasons like the psychological relics of the past, etc., but is a<br />

result of the iron necessity to give birth to and support a<br />

privileged minority so long as it is impossible to guarantee<br />

genuine equality" (p. 47).<br />

<strong>The</strong> bureaucracy arose out of the contradictions of a<br />

backward and impoverished workers' state isolated by the<br />

defeats of the proletarian revolution. But it should not be<br />

imagined that the force of objective contradictions translated<br />

itself immediately and directly into the monstrosities of the<br />

Stalinist regime. <strong>The</strong> signals emitted from the economic base,<br />

however powerful their source, are received at the outer<br />

layers of the political superstructure and recorded in the form<br />

of program and policy only after they have been mediated by<br />

the contradictory influences of historical tradition, culture,<br />

ideology and even individual psychology. <strong>The</strong> crystallization<br />

of the bureaucratic strata into a definite political tendency<br />

which ultimately destroyed the Bolshevik Party was a<br />

complex, bitter and protracted process. It would be a mistake<br />

to believe that those who became the representatives of the<br />

bureaucratic faction started out with the aim of betraying and<br />

destroying the work of the Russian <strong>Revolution</strong>. Certainly, at<br />

the outset of the political struggle within the Bolshevik Party,<br />

Stalin and his supporters did not see themselves as the<br />

defenders of privilege and inequality, i.e., of the bourgeois<br />

function of the workers' state. Stalin's narrow empiricism —<br />

his inability to analyze day-to-day events in relation to more<br />

profound social processes or to follow the trajectory of class

Introduction xix<br />

forces — permitted him to become the leader of the<br />

bureaucracy without being able to foresee the long-term<br />

consequences of his struggle against the Left Opposition. As<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> explained:<br />

"It would be naive to imagine that Stalin, previously<br />

unknown to the masses, suddenly issued from the wings fully<br />

armed with a complete strategical plan. No indeed. Before<br />

he felt out his own course, the bureaucracy felt out Stalin<br />

himself. He brought it all the necessary guarantees: the<br />

prestige of an Old Bolshevik, a strong character, narrow<br />

vision, and close bonds with the political machine as the sole<br />

source of his influence. <strong>The</strong> success which fell upon him was<br />

a surprise to Stalin himself. It was the friendly welcome of<br />

the new ruling group, trying to free itself from the old<br />

principles and from the control of the masses, and having<br />

need of a reliable arbiter in its inner affairs. A secondary<br />

figure before the masses and in the events of the revolution,<br />

Stalin revealed himself as the indubitable leader of the<br />

<strong>The</strong>rmidorian bureaucracy, as first in its midst" (pp. 80-81).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> was the culmination of the<br />

theoretical and political struggle against the bureaucracy<br />

that <strong>Trotsky</strong> had initiated in 1923. In the autumn of that<br />

year, <strong>Trotsky</strong> had written a series of articles, published under<br />

the title <strong>The</strong> New Course, in which he noted with alarm the<br />

growth of bureaucratic tendencies in the bloated apparatuses<br />

of the Soviet state and Bolshevik Party. He saw the<br />

suffocation of inner-party democracy as a symptom of the<br />

increasingly independent authority of the bureaucracy over<br />

all spheres of Soviet life.<br />

When this struggle began, <strong>Trotsky</strong> still enjoyed immense<br />

prestige within the Bolshevik Party and among the Soviet<br />

masses. He was, alongside the ailing Lenin, the most<br />

authoritative leader of the October <strong>Revolution</strong> and the new<br />

Soviet state. His criticisms found broad support within the<br />

Bolshevik Party — especially among those layers which had<br />

played the most outstanding role in the period of the<br />

revolution and civil war. <strong>The</strong> New Course provided the initial<br />

platform for the creation of the Left Opposition, which sought<br />

to counter the growing influence of the bureaucracy. <strong>The</strong><br />

vitriolic response which <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s articles provoked was itself

XX Introduction<br />

an indication that the bureaucracy had already become a<br />

social force that was sufficiently aware of its interests to<br />

defend itself against Marxist criticism.<br />

Lenin died on January 21, 1924. 4<br />

By the autumn of that<br />

year, the divergence between the interests of the Soviet<br />

working class and the increasingly self-conscious bureaucracy<br />

found its expression in the formulation of a political line<br />

which was diametrically opposed to the internationalist<br />

program and perspectives upon which the Bolshevik Party<br />

had been based since its origin. That the development of<br />

socialism in the Soviet Union depended ultimately upon the<br />

victory of the socialist revolution in the advanced European<br />

centers of world capitalism had always been, as we have<br />

already noted, an unquestioned premise of the Bolshevik, i.e.,<br />

Marxist, perspective. As long as Lenin was alive, no one in<br />

the leadership of the Bolshevik Party had ever suggested<br />

that the resources of the Soviet Union were sufficient for the<br />

creation of a self-contained socialist society. In fact, Marxist<br />

theory did not even attribute such possibilities to an advanced<br />

capitalist country. From the writing of the Communist<br />

Manifesto in 1847 to the victory of the October <strong>Revolution</strong> 70<br />

years later, the guiding principle of the Marxist movement<br />

had been its unshakeable conviction that the achievement of<br />

socialism depended upon the unified international efforts of<br />

the workers of all countries and their victory over world<br />

capitalism.<br />

Thus, when Stalin proclaimed, with the encouragement of<br />

Bukharin, that it was possible to build socialism in one<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> Soviet historian Roy Medvedev cites evidence that suggests that<br />

Lenin's fatal stroke was brought on by his anguish over the increasingly<br />

ferocious attacks being directed against <strong>Trotsky</strong> inside the party<br />

"Krupskaya [Lenin's widow] tells us," Medvedev writes, "that on 19 and<br />

20 January 1924 she read out to Lenin the resolutions of the Thirteenth Party<br />

Conference which had just been published, summing up the results of the<br />

debate with <strong>Trotsky</strong>. Listening to the resolutions — so harshly formulated<br />

and unjust in their conclusions — Lenin again became intensely agitated<br />

Hoping that it would have a calming effect, Krupskaya told him that the<br />

resolutions had been approved unanimously by the Party Conference<br />

However, this was hardly reassuring for Lenin, whose worst fears as<br />

expressed in his Testament were beginning to come true. In the event, it was<br />

on the next day, and in a state of extreme distress, that Lenin died" (On<br />

Stalin and Stalinism [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979], p 32).

Introduction xxi<br />

country, his declaration represented more than a basic<br />

revision of Marxist theory. Though he did not realize this<br />

himself, Stalin was articulating the views of an expanding<br />

bureaucracy which saw the Soviet state not as the bastion<br />

and staging ground of world socialist revolution, but as the<br />

national foundation upon which its revenues and privileges<br />

were based.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Stalinist faction did not all at once renounce the goal<br />

of world revolution; rather, it indignantly protested the<br />

accusations of the Left Opposition. Nevertheless, the propagation<br />

of the theory of "socialism in one country" signalled<br />

a profound shift in the direction of the international policy of<br />

the Soviet regime and in the role of the Comintern. 5<br />

<strong>The</strong><br />

Stalinists asserted that the USSR could arrive at socialism<br />

if only it was not thrown back by the intervention of<br />

imperialist armies. From this it followed that the realization<br />

of Soviet socialism required not the overthrow of world<br />

imperialism, but its neutralization through diplomatic means.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Left Opposition did not object in principle to diplomatic<br />

agreements between the Soviet Union and capitalist states.<br />

At the height of <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s political influence, the Soviet Union<br />

had scored triumphs in the sphere of diplomacy, most notably<br />

the successful outcome of the negotiations at Rapallo in 1922.<br />

However, these agreements were frankly characterized as<br />

tactical maneuvers by Soviet Russia, aimed at stabilizing its<br />

position until the international proletariat came directly to<br />

its rescue. It was understood as a matter of course that the<br />

fate of the workers' state was inextricably linked to that of<br />

international socialism. Moreover, the diplomatic initiatives<br />

of the Soviet Union imposed no obligations upon the local<br />

Communist parties, whose main concern had to be the<br />

maximum development of the independent revolutionary<br />

activity of the working class.<br />

But under the influence of the Soviet bureaucracy, the role<br />

of the Comintern was transformed. <strong>The</strong> new theory of<br />

"national socialism" soon began to affect the strategy and<br />

tactics of the Communist International. <strong>The</strong> opportunist<br />

5. Comintern was the name by which the Third, or Communist,<br />

International was commonly known

xxii Introduction<br />

alliance formed in 1925 between the inexperienced British<br />

Communist Party and the trade union bureaucrats who<br />

participated in the Anglo-Russian Committee was encouraged<br />

by the Stalinists in the hope that the sympathy of these<br />

influential officials would weaken the anti-Soviet policy of the<br />

British government. Similar considerations provided at least<br />

part of the motivation for Stalin's insistence between 1925<br />

and 1927 that the Chinese Communist Party subordinate<br />

itself to the bourgeois nationalist government of Chiang<br />

Kai-shek. In both cases, the attempts to cultivate friends<br />

overseas at the expense of the political independence of the<br />

working class led to disaster: the British Communist Party's<br />

glorification of the trade union leaders facilitated the betrayal<br />

of the 1926 General Strike; the Chinese Communist Party's<br />

submission to the leadership of the bourgeois Kuomintang led<br />

to the physical annihilation of its cadre by Chiang's army in<br />

1927.<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> never claimed that the defeats in Britain and<br />

China had been consciously desired by the Soviet bureaucracy.<br />

He maintained, rather, that the catastrophic international<br />

setbacks — like the results of so many of his policies<br />

— took Stalin by surprise. But these and other defeats for<br />

which the political line of the Stalinists was responsible had<br />

an objective impact upon class relations within the Soviet<br />

Union. <strong>The</strong> defeats suffered by the international working<br />

class discouraged the Soviet workers, undermined their<br />

confidence in the perspectives and prospects of world<br />

socialism, and, therefore, strengthened the bureaucracy. It<br />

was by no means accidental that the annihilation of the<br />

Chinese Communist Party in May 1927, which had been<br />

clearly foreseen by <strong>Trotsky</strong>, set the stage for the political<br />

defeat and expulsion of the Left Opposition from the Soviet<br />

Communist Party. This was followed within a few months by<br />

the arrest of the leaders of the Opposition and their exile to<br />

the distant reaches of the USSR. <strong>Trotsky</strong> was transported to<br />

Alma-Ata near the border of China. One year later, in<br />

January 1929, <strong>Trotsky</strong> was expelled from the Soviet Union<br />

to the island of Prinkipo off the Turkish coast.<br />

Stalin had hoped that the expulsion of <strong>Trotsky</strong> would<br />

deprive him of the possibility of developing the activity of the

Introduction xxiii<br />

Opposition in the Soviet Union. But he had underestimated<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong>'s ability to command the attention of a world<br />

audience. Though deprived of the trappings of power, <strong>Trotsky</strong><br />

was the intellectual and moral embodiment of the greatest<br />

revolution in world history. In contrast to Stalin, who<br />

represented a bureaucratic machine and was dependent upon<br />

it, <strong>Trotsky</strong> personified a world-historic idea which found<br />

through his writings its most brilliant and cultured expression.<br />

Even within the Soviet Union, it was not always possible<br />

for the Stalinist regime to prevent <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s words from<br />

penetrating the sealed borders and evoking an impassioned<br />

response. 6<br />

Despite the hardships of exile, the endless stream<br />

of political analysis that flowed from <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s pen, combined<br />

with a voluminous correspondence, transformed the Left<br />

Opposition into an international movement.<br />

In the first years of <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s exile, the International Left<br />

Opposition considered itself a faction, albeit, an illegal one,<br />

inside the Communist International. It did not call for the<br />

formation of a new International, but fought for the reform<br />

of the Comintern and its national sections. <strong>Trotsky</strong> refused<br />

to abandon prematurely the possibility of returning the<br />

Communist parties, which remained the political home of the<br />

most class-conscious sections of the working class, to a<br />

Marxist program. <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s writings were specifically directed<br />

to the hundreds of thousands of workers who had<br />

joined the Communist International because they believed<br />

that it was the instrument of socialist revolution.<br />

<strong>The</strong> struggle of the International Left Opposition to reform<br />

the Comintern assumed the greatest political urgency in<br />

Germany, where the working class was confronted with the<br />

menace of fascism. Despite the vast potential power of the<br />

German working class, it was disoriented and paralyzed by<br />

6. For example, a young Chinese student who was won to <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s views<br />

while studying in Moscow described the impact of an open letter to the Soviet<br />

workers that <strong>Trotsky</strong> wrote in 1929 to refute the slanders of the regime: "His<br />

open letter was widely circulated among the masses, and was warmly<br />

received as it was brilliantly written and full of passion I translated it into<br />

Chinese, and although it lost much of its original fire and beauty in the<br />

process, it still greatly charmed and moved our Chinese comrades, some of<br />

whom began to cry as they read it" (Wang Fan-hsi, Chinese <strong>Revolution</strong>ary<br />

[Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980], p 93)

xxiv<br />

Introduction<br />

the policies of its mass organizations. While the Social<br />

Democrats pathetically depended upon the bourgeois state<br />

and its Weimar Constitution to save them from the Nazis, the<br />

Stalinists refused to fight for the unity of all working class<br />

organizations in the struggle against fascism. With the<br />

encouragement of Stalin, the German Communist Party<br />

asserted with criminal light-mindedness that there existed<br />

no essential difference between Social Democracy and the<br />

Nazi Party, and that the former were, in fact, "social<br />

fascists." <strong>The</strong>refore, the Stalinists claimed, it was impermissible<br />

for the Communist Party to enter into a "united<br />

front" with the Social Democracy in order to conduct a<br />

common defense of the workers' movement against the fascist<br />

hordes. From Prinkipo <strong>Trotsky</strong> addressed fiery appeals to the<br />

ranks of the German Communist Party, calling upon them<br />

to prevent a catastrophe by reversing the policies of their<br />

leaders and implementing a united front of the entire<br />

workers' movement against the Nazis.<br />

"Worker-Communists," he wrote, "you are hundreds of<br />

thousands, millions; you cannot leave for any place; there are<br />

not enough passports for you. Should Fascism come to power,<br />

it will ride over your skulls and spines like a terrific tank.<br />

Your salvation lies in merciless struggle. And only a fighting<br />

unity with the Social-Democratic workers can bring victory.<br />

Make haste, worker-Communists, you have very little time<br />

left!" (Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>, Germany: 1931-32 [London: New Park<br />

Publications, 1970], p. 38).<br />

<strong>The</strong> German Communist Party refused to change its policy<br />

and direct a unified struggle against the Nazi advance. Thus,<br />

on January 31, 1933 Hitler came to power without a shot<br />

being fired. Within a few months all the trade union and<br />

political organizations of what had been the largest and most<br />

powerful labor movement in Europe were declared illegal and<br />

destroyed. In the face of this unprecedented disaster, the<br />

Communist International issued a statement endorsing the<br />

policies which it had pursued and absolved itself of any<br />

responsibility for the defeat. For <strong>Trotsky</strong>, the defeat of the<br />

German working class was an event of world-historical<br />

magnitude. As the vote of the Social Democrats for war credits<br />

at the start of World War I in 1914 signified the collapse of

Introduction XXV<br />

the Second International, the Stalinists' complicity in the<br />

tragic debacle of the German workers' movement meant the<br />

collapse of the Third. In the face of the catastrophic defeat of<br />

, t n e German working class, to which the Communist International<br />

responded by voting itself congratulations for the<br />

policies which enabled Hitler to take power, it was impossible<br />

to speak any longer of reforming the Stalinist parties. It was<br />

necessary to begin the work of constructing a new, Fourth<br />

International.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Moscow leadership has not only proclaimed as<br />

infallible the policy which guaranteed victory to Hitler, but<br />

has also prohibited all discussion of what had occurred. And<br />

this shameful interdiction was not violated or overthrown.<br />

No national congresses; no international congress, no discussions<br />

at party meetings; no discussion in the press! An<br />

organization which was not roused by the thunder of fascism<br />

and which submits docilely to such outrageous acts of the<br />

bureaucracy demonstrates thereby that it is dead and that<br />

nothing can ever revive it. To say this openly and publicly is<br />

our direct duty toward the proletariat and its future. In all<br />

our subsequent work it is necessary to take as our point of<br />

departure the historical collapse of the official Communist<br />

International" (Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>, Writings of Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong><br />

[1932-33] [New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972] pp. 304-5).<br />

Of all the decisions taken by <strong>Trotsky</strong> in the course of his<br />

life, none was more irrevocable, controversial, profound and<br />

farsighted than the founding of the Fourth International. <strong>The</strong><br />

Soviet regime and its international apparatus of toadies<br />

responded with hysterical denunciations that found within a<br />

few years their finished expression in the Moscow Trial<br />

indictments and the assassinations carried out by the<br />

GPU-NKVD, both within and beyond the borders of the Soviet<br />

Union. But even among many who considered themselves<br />

sympathetic to <strong>Trotsky</strong>, his call for the Fourth International<br />

seemed premature, ill-advised and even rash. <strong>The</strong>se criticisms<br />

were generally based on the apparent "realities" of the<br />

political situation: <strong>Trotsky</strong> was too isolated to build an<br />

International, his call would go unnoticed, the prestige of the<br />

Comintern was still too great within the international<br />

workers' movement, a new International could only be built

xxvi<br />

Introduction<br />

on the basis of a victorious revolution, etc. But such "realism"<br />

— which amounted to little more than an empirical listing of<br />

conjunctural difficulties — was of a rather superficial<br />

character.<br />

For <strong>Trotsky</strong>, the criterion of political realism was the<br />

correspondence of program and policy to the essential and<br />

law-governed development of the class struggle. He perceived<br />

that the role played by the Soviet bureaucracy in the defeat<br />

of the German working class and its reaction to this<br />

catastrophe marked a turning point in the political and social<br />

evolution — or, let us say, degeneration — of the Stalinist<br />

regime. <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s call for the Fourth International was not<br />

intended as punishment for the latest and most terrible crime<br />

of the bureaucracy and the Comintern; it was, rather, the<br />

necessary political response to the fact that the Stalinist<br />

regime and the prostituted Comintern were beyond reform.<br />

By giving its assent to the policies which had led to the<br />

destruction of the German workers' movement, the Comintern<br />

demonstrated that it no longer served, even in the most<br />

tenuous manner, the cause of international socialism. <strong>The</strong><br />

leaders of the Communist parties affiliated to the Comintern<br />

were hired flunkeys of the GPU-NKVD, prepared to carry out<br />

whatever instructions they received from the Kremlin. <strong>The</strong><br />

revival of international Marxism could not be achieved<br />

through the reform of the Comintern, but only in a ruthless<br />

struggle against it. Thus, the only "realistic" course of action<br />

open to those who remained devoted to the cause of world<br />

socialism was to build a new, Fourth, International.<br />

If the old International was beyond reform, so too was the<br />

regime whose orders it obediently executed. In the Soviet<br />

Union, where the Communist Party held state power, the<br />

Fourth International raised the banner of political revolution<br />

against the ruling bureaucracy. <strong>The</strong> revolutionary overthrow<br />

of the Stalinist regime was necessary because the material<br />

interests of the bureaucracy as a distinct social stratum had<br />

become so profoundly estranged from those of the working<br />

class that its domination of Soviet society was incompatible<br />

with the survival of the USSR as a workers' state.<br />

<strong>The</strong> political conclusions upon which <strong>Trotsky</strong> based his call<br />

for the founding of the Fourth International were theoreti-

Introduction xxvii<br />

cally substantiated and given a finished programmatic form<br />

with the writing of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong>. Herein lies the<br />

essential significance of this work: As Lenin's Imperialism<br />

had demonstrated in 1916 that the betrayal of Social<br />

Democracy was the political expression of its social evolution<br />

into an agency of international capital in the workers'<br />

movement, <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> revealed the<br />

social relations and material interests of which the crimes of<br />

the Stalinist regime were the necessary expression. Like<br />

Social Democracy, Stalinism could not be "reformed," i.e.,<br />

made to serve the interests of the working class, because its<br />

own interests were tied to those of imperialism and hostile<br />

to the Soviet and international proletariat.<br />

It was not long before <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s assessment was confirmed<br />

by events. In the aftermath of Hitler's victory, the Stalinist<br />

regime and the Communist International lunged to the right.<br />

<strong>The</strong> reaction of the Soviet bureaucracy to the fascist triumph<br />

was to seek membership in the League of Nations, which<br />

Lenin had characterized as a "thieves' kitchen." This decision<br />

was symbolic of the transformation of the Soviet bureaucracy<br />

into a political agency of imperialism in the international<br />

workers' movement. From 1933 on, the essential link between<br />

the defense of the USSR and the cause of world socialist<br />

revolution was repudiated. Instead, with ever greater cynicism,<br />

the Stalinist regime based the defense of the Soviet<br />

Union upon the preservation of the imperialist world order.<br />

Confronted with a fascist regime in Germany, whose existence<br />

was the product of the criminal policies of the Kremlin,<br />

the Stalinist bureaucracy sought salvation through the<br />

promotion of Soviet-imperialist "collective security." <strong>The</strong><br />

Communist International was transformed into a direct<br />

instrument of Soviet foreign policy, offering to protect<br />

bourgeois regimes against the threat of an insurgent proletariat<br />

in return for diplomatic agreements with the Kremlin.<br />

This was the essential purpose of the "popular front"<br />

policy introduced by the Communist International in 1935.<br />

Bourgeois governments which professed friendly intentions<br />

toward the USSR and supposedly shared its hostility to Nazi<br />

Germany were to receive political support from the local<br />

Communist parties. All the fundamental Marxist criteria

xxviii Introduction<br />

which traditionally had determined the attitude of the<br />

revolutionary workers' movement to bourgeois parties and<br />

regimes were cast aside. Parties and states were no longer<br />

evaluated on the basis of the class interests and property<br />

forms they defended; instead, the scientific terminology of<br />

Marxism was replaced with deceptive and empty adjectives<br />

like "peace-loving" and "antifascist." <strong>The</strong> local Communist<br />

parties assumed on behalf of the Kremlin responsibility for<br />

suppressing the struggle of the working class against<br />

governments which were so designated. Seeking alliances<br />

with the "democratic" imperialists — a designation which<br />

turned a blind eye to the plight of the colonial slaves of Britain,<br />

France, Belgium, Holland, etc. — the Soviet bureaucracy did<br />

everything it could to demonstrate that it was committed to the<br />

defense of the imperialist status quo. In an attempt to assuage<br />

the lingering concerns of the imperialists, Stalin told the<br />

Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, in a celebrated interview<br />

conducted on March 1,1936, that fears about the international<br />

revolutionary aims of the Soviet regime were a "tragicomic<br />

misunderstanding." 7<br />

<strong>The</strong> Soviet bureaucracy's sabotage of<br />

the revolutionary struggles of the international proletariat<br />

found its most complete and bloody expression in Spain,<br />

where the Communist Party aborted the struggle against the<br />

fascists in the interests of defending bourgeois property. With<br />

the aid of the GPU, the bourgeois-liberal government<br />

suppressed the May 1937 uprising of the Catalonian working<br />

class and thereby guaranteed the ultimate victory of Franco.<br />

7 Commenting on this interview, <strong>Trotsky</strong> suggested that if Stalin had<br />

been able to speak completely openly, without having to take into account<br />

the impact of his words among the more conscious sections of the<br />

international working class, he might have said: " Tn the eyes of Lenin the<br />

League of Nations was an organization for the bloody suppression of the<br />

toilers But we see in it — an instrument of peace. Lenin spoke of the<br />

inevitability of revolutionary wars But we consider the export of revolution<br />

— nonsense. Lenin branded the alliance between the proletariat and the<br />

national bourgeoisie as a betrayal. But we are doing all in our power to drive<br />

the French proletariat onto this road. Lenin lashed the slogan of<br />

disarmament under capitalism as an infamous swindle of the toilers But<br />

we have built our entire policy upon this slogan Your comical misunderstanding'<br />

— that is how Stalin could have concluded — 'consists of the fact that<br />

you take us for the continuators of Bolshevism, whereas we are its<br />

gravediggers' " (Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>, Writings of Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong> [1935-36] [New<br />

York: Pathfinder Press, 1970] p 277)

Introduction xxix<br />

<strong>The</strong> turn by the USSR toward direct collaboration with the<br />

international bourgeoisie was complemented by the intensification<br />

of state repression within the borders of the degenerated<br />

workers' state. <strong>The</strong> inner connection between these<br />

parallel processes is generally ignored by bourgeois historians<br />

who find it politically inconvenient to examine why the<br />

heyday of popular frontism — when Stalinism was being feted<br />

in the salons of the intellectual trend-setters — coincided<br />

with the wholesale extermination within the USSR of<br />

virtually all those who had played a leading role in the<br />

October <strong>Revolution</strong> and the civil war. <strong>The</strong> blood purges which<br />

were launched with the opening of the first round of the<br />

Moscow Trials in August 1936 were intended not only to<br />

eradicate all those who might become the focus of revolutionary<br />

opposition to the bureaucracy, but also to demonstrate<br />

to the world bourgeoisie that the Stalinist regime had broken<br />

irrevocably with the heritage of 1917. A river of blood now<br />

divided Stalinism from Bolshevism.<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong>, living in Norway, completed the introduction of<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> and sent the final portions of the<br />

manuscript to the publishers barely two weeks before the<br />

beginning of the trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev in Moscow.<br />

<strong>The</strong> timing was fortuitous: One day after the trial's conclusion<br />

and the execution of the 16 defendants, the Norwegian Social<br />

Democratic government, submitting to pressure from the<br />

Kremlin, demanded that <strong>Trotsky</strong> renounce the right to<br />

publicly comment on contemporary political events, i.e., on<br />

the Moscow frame-up trial. When <strong>Trotsky</strong> indignantly<br />

refused, the Norwegian Social Democrats issued orders for<br />

his arrest and internment. <strong>The</strong> police denied <strong>Trotsky</strong> direct<br />

contact with his political associates, stopped his correspondence,<br />

confiscated his manuscripts and even limited the hours<br />

he was permitted to exercise outdoors. <strong>The</strong>se restrictions had<br />

their intended effect: for four crucial months, <strong>Trotsky</strong> was<br />

blocked from publicly answering the monstrous charges made<br />

against him by the Stalinist regime. 8<br />

8. With <strong>Trotsky</strong> interned and unable to reply to his accusers, the<br />

responsibility for exposing the Moscow Trials fell to his son, Leon Sedov.<br />

Within a few weeks, he succeeded in publishing <strong>The</strong> Red Book on the Moscow<br />

Trials, which tore the indictment to shreds Later, after Sedov's death in

XXX Introduction<br />

<strong>The</strong> behavior of the Norwegian government was made all<br />

the more scandalous by the way it proceeded to organize the<br />

deportation of <strong>Trotsky</strong> from the country. Earlier in August,<br />

supporters of Quisling, the leader of the Norwegian fascist<br />

organization, attempted unsuccessfully to burglarize <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s<br />

residence. After they were apprehended, the burglars claimed<br />

that they had discovered material proving that <strong>Trotsky</strong> had<br />

violated the terms of his Norwegian exile. <strong>The</strong> police initially<br />

dismissed their outlandish claims. But, responding to pressure<br />

exerted by the Kremlin in the aftermath of the trial of<br />

Zinoviev and Kamenev, the Norwegian government decided<br />

to make opportune use of the lies of the fascist burglars.<br />

When <strong>Trotsky</strong> appeared to give evidence at a hearing<br />

supposedly called to investigate the burglary, he found<br />

himself instead the subject of an intense interrogation aimed<br />

at proving that he had abused the "hospitality" of Norwegian<br />

democracy. Standing in the Ministry of Justice before Trygve<br />

Lie (the future United Nations Secretary-General) and his<br />

associates, <strong>Trotsky</strong> confronted the frightened Social Democratic<br />

officials who were using the testimony of fascist<br />

hoodlums as a legal pretext for his deportation from Norway.<br />

"At this point," according to an account based on the<br />

recollection of witnesses to the proceedings and their ironic<br />

aftermath, "<strong>Trotsky</strong> raised his voice so that it resounded<br />

through the halls and corridors of the Ministry: "This is your<br />

first act of surrender to Nazism in your own country. You<br />

will pay for this. You think yourselves secure and free to deal<br />

with a political exile as you please. But the day is near —<br />

remember this! — the day is near when the Nazis will drive<br />

you from your country, all of you together with your<br />

Pantofj'el-Minister-President.' Trygve Lie shrugged at this odd<br />

February 1938 at the hands of Stalinist assassins, <strong>Trotsky</strong> recalled his joy<br />

as he read through a copy of <strong>The</strong> Red Book: "What a priceless gift to us, under<br />

these conditions, was Leon's book, the first crushing reply to the Kremlin<br />

falsifiers. <strong>The</strong> first few pages, I recall, seemed to me pale That was because<br />

they only restated a political appraisal, which had already been made, of the<br />

general condition of the USSR. But from the moment the author undertook<br />

an independent analysis of the trial, I became completely engrossed Each<br />

succeeding chapter seemed to me better than the last 'Good boy, Levusyatka!'<br />

my wife and I said *We have a defender!' " (Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>, Leon Sedov: Son,<br />

Friend, Fighter [New York: Labor Publications, 1977], pp 21-22).

Introduction<br />

xxxi<br />

piece of soothsaying. Yet after less than four years the same<br />

government had indeed to flee from Norway before the Nazi<br />

invasion; and as the Ministers and their aged King Haakon<br />

stood on the coast, huddled together and waiting anxiously<br />

for a boat that was to take them to England, they recalled<br />

with awe <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s words as a prophet's curse come true"<br />

(Isaac Deutscher, <strong>The</strong> Prophet Outcast: <strong>Trotsky</strong> 1929-40 [New<br />

York: Vintage <strong>Books</strong>, 1963], pp. 341-42).<br />

After his deportation from Norway in December 1936,<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong> did not conceal his disgust with the cowardice of the<br />

Norwegian Social Democrats: "When I look back today on<br />

this period of internment, I must say that never, anywhere,<br />

in the course of my entire life — and I have lived through<br />

many things — was I persecuted with as much miserable<br />

cynicism as I was by the Norwegian 'Socialist' government.<br />

For four months these ministers, dripping with democratic<br />

hypocrisy, gripped me in a stranglehold to prevent me from<br />

protesting the greatest crime history may ever know" (Leon<br />

<strong>Trotsky</strong>, Writings of Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong> [1936-37] [New York:<br />

Pathfinder Press, 1970], p. 36).<br />

Even if one does not consider the conditions under which<br />

it was written, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>Betrayed</strong> must be judged an<br />

astonishing literary and intellectual achievement. Living in<br />

a remote village in already remote Norway, cut off from all<br />

direct contact with Soviet citizens, compelled to follow events<br />

as best he could through the press, <strong>Trotsky</strong> nevertheless<br />

succeeded in producing an amazingly detailed, comprehensive,<br />

and enduring analysis of the Soviet Union. A<br />

profound and critical sense of realism animated <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s<br />

work, which sought to uncover and explain the problems of a<br />

backward country which, on the basis of a proletarian<br />

revolution, set out to construct socialism, but without the<br />

necessary economic, technical and cultural resources. In<br />

opposition to the anticommunist literature, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

<strong>Betrayed</strong> carefully outlined the genuine and, in many areas,<br />

staggering advances realized by the Soviet state within less<br />

than two decades of its creation. <strong>The</strong>se advances, <strong>Trotsky</strong><br />

insisted, demonstrated the creative possibilities of the<br />

proletarian revolution and the vast progressive potential<br />

inherent in the principle of central planning. However, and

xxxii Introduction<br />

here he was answering the numerous intellectual sycophants<br />

of the Kremlin, the policies of the Stalinist regime, despite<br />

the short-term successes, were intensifying the contradictions<br />

of the Soviet state and leading toward its destruction.<br />

Today, the desperate crisis of the Stalinist regime has been<br />

seized upon by the bourgeoisie as final and conclusive proof<br />

that "socialism has failed." However, the value of these<br />

pronouncements may best be judged not by what they say as<br />

by what they leave out It is virtually impossible to find in<br />

either the capitalist press or "respectable" academic treatises<br />

any reference to the <strong>Trotsky</strong>ist, i.e., Marxist, critique of<br />

the Stalinist sabotage of the Soviet economy. Yet <strong>Trotsky</strong>'s<br />

observations were astonishingly prescient. He anticipated<br />

virtually all the problems which have now assumed a<br />