Micronutrient Interactions: Impact on Child Health and ... - Idpas.org

Micronutrient Interactions: Impact on Child Health and ... - Idpas.org

Micronutrient Interactions: Impact on Child Health and ... - Idpas.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MICRONUTRIENT<br />

INTERACTIONS<br />

IMPACT ON CHILD HEALTH AND NUTRITION<br />

WASHINGTON, DC, JULY 29–30, 1996<br />

Sp<strong>on</strong>sored by:<br />

U.S. Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development<br />

Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organizati<strong>on</strong> of the United Nati<strong>on</strong>s

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>:<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC, July 29–30, 1996<br />

Sp<strong>on</strong>sored by:<br />

U.S. Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development<br />

Food <strong>and</strong> Agiculture Organizati<strong>on</strong> of the United Nati<strong>on</strong>s

© 1998 Internati<strong>on</strong>al Life Sciences Institute<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

ii<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

No part of this publicati<strong>on</strong> may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,<br />

electr<strong>on</strong>ic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permissi<strong>on</strong> of the copyright<br />

holder. The Internati<strong>on</strong>al Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) does not claim copyright <strong>on</strong> U.S. government informati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Authorizati<strong>on</strong> to photocopy items for internal or pers<strong>on</strong>al use is granted by ILSI for libraries <strong>and</strong> other users registered with<br />

the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) Transacti<strong>on</strong>al Reporting Services, provided that $0.50 per page is paid directly to<br />

CCC, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. (508) 750-8400.<br />

The use of trade names <strong>and</strong> commercial sources in this document is for purposes of identificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly, <strong>and</strong> does not imply<br />

endorsement by ILSI. In additi<strong>on</strong>, the views expressed herein are those of the individual authors <strong>and</strong>/or their <strong>org</strong>anizati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

<strong>and</strong> do not necessarily reflect those of ILSI.<br />

Library of C<strong>on</strong>gress Catalog Number: 98-70710<br />

ILSI PRESS<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Life Sciences Institute<br />

1126 Sixteenth Street, N. W.<br />

Washingt<strong>on</strong>, D. C. 20036-4810<br />

ISBN 1-57881-007-8<br />

Printed in the United States of America

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Table of C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

Acknowledgments _________________________________________________________________ v<br />

Foreword ______________________________________________________________________ vii<br />

Opening Remarks _________________________________________________________________ 1<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> ________________________________________________________ 3<br />

Bo Lönnerdal<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>–ascorbic Acid <strong>and</strong> Ir<strong>on</strong>-calcium <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> Their<br />

Relevance in Complementary Feeding _________________________________________________ 11<br />

Lindsay H. Allen<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong> Bioavailability from Weaning foods: The Effect of Phytic Acid ___________________________ 21<br />

Lena Davidss<strong>on</strong><br />

The Influence of Vitamin A <strong>on</strong> Ir<strong>on</strong> Status <strong>and</strong> Possible C<strong>on</strong>sequences for<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> Deficiency Alleviati<strong>on</strong> Programs __________________________________________ 28<br />

Werner Schultink <strong>and</strong> Rainer Gross<br />

Effects of Riboflavin Deficiency <strong>on</strong> the H<strong>and</strong>ling of Ir<strong>on</strong> ___________________________________ 36<br />

Hilary J. Powers<br />

Effects of Food Processing Techniques <strong>on</strong> the C<strong>on</strong>tent <strong>and</strong> Bioavailability of Vitamins:<br />

A Focus <strong>on</strong> Carotenoids ___________________________________________________________ 43<br />

Alexa W. Williams <strong>and</strong> John W. Erdman, Jr.<br />

Food Processing Methods for Improving the Zinc C<strong>on</strong>tent <strong>and</strong> Bioavailability of Home-based <strong>and</strong><br />

Commercially Available Complementary Foods _________________________________________ 50<br />

Rosalind S. Gibs<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Elaine L. Fergus<strong>on</strong><br />

Effects of Cooking <strong>and</strong> Food Processing <strong>on</strong> the C<strong>on</strong>tent of Bioavailable Ir<strong>on</strong> in Foods ____________ 58<br />

Dennis D. Miller<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong>’s Experiences with Fortified Weaning Foods _____________________________________ 69<br />

Visith Chavasit <strong>and</strong> Kraisid T<strong>on</strong>tisirin<br />

High-protein-quality Vegetable Mixtures for Human Feeding _______________________________ 75<br />

Ricardo Bressani<br />

Addendum: A Summary of the Workshop Discussi<strong>on</strong> Sessi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Food Processing Interventi<strong>on</strong>s to Improve the <str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>tent of<br />

Home-based Complementary Foods _________________________________________________ 82<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in Fortified Complementary Foods <strong>and</strong> Supplements _________________________ 84<br />

Barriers to Overcome <strong>and</strong> Knowledge Needed to Implement a<br />

Successful Complementary Feeding <strong>and</strong> Supplementati<strong>on</strong> Program __________________________ 90<br />

Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s ________________________________________________________________ 92<br />

References ______________________________________________________________________ 92<br />

Appendix 1: Workshop Participants ___________________________________________________ 95<br />

Appendix 2: Workshop Agenda _____________________________________________________ 100<br />

iii

iv<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Acknowledgments<br />

The U.S. Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development (USAID) <strong>and</strong> the Opportunities for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Interventi<strong>on</strong>s (OMNI) Research program would like to thank Dr. Adrianne Bendich,<br />

Dr. S<strong>and</strong>ra Bartholmey, <strong>and</strong> Dr. David Yeung for chairing the sessi<strong>on</strong>s at the July 1996 workshop<br />

<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>. Mr. David Alnwick,<br />

Dr. Lindsay Allen, <strong>and</strong> Dr. Deddy Muchtadi facilitated three discussi<strong>on</strong> groups <strong>and</strong> we thank<br />

them for their leadership. The participati<strong>on</strong> of Dr. S<strong>and</strong>ra Huffman, Dr. Dennis Miller, <strong>and</strong><br />

Dr. Rosalind Gibs<strong>on</strong> as rapporteurs <strong>and</strong> presenters of the group discussi<strong>on</strong>s is gratefully<br />

appreciated.<br />

v

vi<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Foreword<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> deficiencies result from inadequate dietary intake, impaired absorpti<strong>on</strong>,<br />

limited bioavailability, excessive losses, increased requirements, or a combinati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

these factors. Although the functi<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>sequences of micr<strong>on</strong>utrient deficiencies are<br />

largely known, micr<strong>on</strong>utrient interacti<strong>on</strong>s at the metabolic level, as well as within the<br />

diet, are less clearly established. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> interacti<strong>on</strong>s are important because they affect<br />

the bioavailability (absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> use) of nutrients. The level of bioavailable micr<strong>on</strong>utrients<br />

can often be improved by changing the food preparati<strong>on</strong> methods used commercially<br />

<strong>and</strong> in the home. Improved processing methods, however, may not increase the level sufficiently<br />

to meet daily micr<strong>on</strong>utrient requirements. Therefore, the c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> of appropriately<br />

mixed foods, fortified complementary foods, or micr<strong>on</strong>utrient supplementati<strong>on</strong> may<br />

be necessary.<br />

On July 29–30, 1996, the workshop <str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong> was held in Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC, under the joint support of the United States<br />

Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development (USAID)/Opportunities for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> Interventi<strong>on</strong>s<br />

(OMNI) Research project, <strong>and</strong> the Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organizati<strong>on</strong> (FAO). At<br />

this workshop, there were eleven presentati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> the impact of micr<strong>on</strong>utrient interacti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>on</strong> nutrient bioavailability <strong>and</strong> nutriti<strong>on</strong>al status, food processing techniques that can improve<br />

the micr<strong>on</strong>utrient c<strong>on</strong>tent <strong>and</strong> bioavailabilty in complementary foods, <strong>and</strong> past experiences<br />

with complementary feeding programs in developing countries. In additi<strong>on</strong>, 45 scientists;<br />

nutriti<strong>on</strong> program managers; <strong>and</strong> representatives of the pharmaceutical <strong>and</strong> food industry,<br />

n<strong>on</strong>governmental <strong>org</strong>anizati<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> internati<strong>on</strong>al d<strong>on</strong>or agencies met to discuss<br />

<strong>and</strong> answer the following questi<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

What food processing methods have been tried to improve the micr<strong>on</strong>utrient c<strong>on</strong>tent of<br />

home-based complementary foods? What additi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong> is needed for improving<br />

the micr<strong>on</strong>utrient c<strong>on</strong>tent of home-based complementary foods?<br />

What micr<strong>on</strong>utrient interacti<strong>on</strong>s are important in developing fortified complementary<br />

foods <strong>and</strong> supplements for infants <strong>and</strong> young children? What micr<strong>on</strong>utrients should be<br />

added to complementary foods <strong>and</strong> supplements <strong>and</strong> at what level?<br />

What are the barriers to implementing a successful complementary feeding <strong>and</strong> supplementati<strong>on</strong><br />

program in developing countries? What additi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong> or efforts<br />

are needed to promote the c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> of complementary foods <strong>and</strong> use of supplements<br />

in developing countries?<br />

USAID, through its OMNI Research project, <strong>and</strong> in cooperati<strong>on</strong> with FAO, is pleased to<br />

provide this proceedings <strong>and</strong> a summary of the discussi<strong>on</strong>s that occurred during this workshop.<br />

It is hoped that this document will help to identify <strong>and</strong> resolve issues critical to the<br />

promoti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> implementati<strong>on</strong> of complementary <strong>and</strong> supplementati<strong>on</strong> programs in developing<br />

countries.<br />

vii

viii<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Opening Remarks<br />

David Oot<br />

Office of <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, U.S. Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development, SA-18,<br />

Room 1200, Washingt<strong>on</strong>, DC 20523-1808<br />

We are all committed to bettering the<br />

lives of children, which ties us together<br />

to deliberate the questi<strong>on</strong>s before<br />

us. The U.S. Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Development (USAID)<strong>and</strong> the Food<br />

<strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organizati<strong>on</strong> of the United<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>s (FAO) are jointly sp<strong>on</strong>soring this 2day<br />

discussi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> micr<strong>on</strong>utrient interacti<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

which has immediate relevance to the lives of<br />

children throughout the world.<br />

USAID <strong>and</strong> FAO have an outst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

track record of working to improve child survival<br />

<strong>and</strong> health. These efforts are grounded<br />

in the underst<strong>and</strong>ing that breast-feeding is<br />

critical for infant health. USAID has l<strong>on</strong>g promoted<br />

breast-feeding as an essential comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

of child survival programs.<br />

Exclusive breast-feeding is the best nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

for an infant up to 6 m<strong>on</strong>ths of age. At<br />

that point, however, nutriti<strong>on</strong> science tells us<br />

that complementary foods should be added<br />

to infants’ diets to complement the nutrients<br />

received from breast milk. This is particularly<br />

important in developing countries, where the<br />

mother’s diet, <strong>and</strong> therefore her breast milk,<br />

may be less than optimal.<br />

Traditi<strong>on</strong>al infant foods are often based<br />

<strong>on</strong> unrefined cereals <strong>and</strong> legumes that are low<br />

in bioavailable micr<strong>on</strong>utrients, such as ir<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> zinc. Processing these foods can improve<br />

the bioavailability of micr<strong>on</strong>utrients. Fortificati<strong>on</strong><br />

of locally available foods can also improve<br />

the level of micr<strong>on</strong>utrients in food; however,<br />

not all c<strong>on</strong>sumers may be able to afford<br />

fortified foods. Nevertheless, fortificati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

marketed infant foods or the use of micr<strong>on</strong>utrient<br />

supplements can enhance the nutriti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

status of socioec<strong>on</strong>omically better-off children<br />

even more.<br />

Two important questi<strong>on</strong>s related to micr<strong>on</strong>utrients<br />

are: Which micr<strong>on</strong>utrients<br />

should be added to complementary foods or<br />

included in pharmaceutical supplements?<br />

What are the optimal amounts to add? To<br />

adequately answer these questi<strong>on</strong>s, we must<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> the extent <strong>and</strong> directi<strong>on</strong> of interacti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

that may occur between various micr<strong>on</strong>utrients<br />

when mixed together in a food<br />

or a supplement.<br />

Present here today are a group of experts<br />

who were selected for their knowledge of the<br />

scientific issues as well as their practical knowledge<br />

of c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s in countries where fortified<br />

foods <strong>and</strong> supplements would be beneficial to<br />

children’s health. In additi<strong>on</strong> to identifying the<br />

optimal mix of micr<strong>on</strong>utrients for complementary<br />

foods <strong>and</strong> supplement preparati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

participants have been asked to help answer<br />

several other questi<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

Which food-processing methods optimize<br />

the micr<strong>on</strong>utrient c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> of<br />

home-based <strong>and</strong> commercially available<br />

complementary foods?<br />

What barriers limit the implementati<strong>on</strong><br />

of successful complementary food programs<br />

in developing countries?<br />

What additi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong> is needed<br />

to implement successful programs designed<br />

to provide nutrient-rich complementary<br />

foods <strong>and</strong> supplements?<br />

Together we can make an important c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong><br />

that will in a very short time provide<br />

nutriti<strong>on</strong>al benefits to children around<br />

the world.<br />

1

2<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong>

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Bo Lönnerdal<br />

Program in Internati<strong>on</strong>al Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, Department of Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, University of California,<br />

Davis, CA 95616<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency is the most comm<strong>on</strong> nutrient<br />

deficiency in both less-developed <strong>and</strong><br />

industrialized countries worldwide<br />

(Lönnerdal <strong>and</strong> Dewey 1995). The c<strong>on</strong>sequences<br />

of ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency anemia are well<br />

recognized, ranging from effects <strong>on</strong> energy<br />

metabolism <strong>and</strong> immune functi<strong>on</strong> to effects<br />

<strong>on</strong> cognitive functi<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> motor development<br />

(Walter 1993, Dallman et al. 1980).<br />

Infants, children, <strong>and</strong> fertile women are particularly<br />

vulnerable populati<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> programs<br />

have been implemented to treat <strong>and</strong><br />

prevent ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency. Ir<strong>on</strong> supplements,<br />

fortificati<strong>on</strong> of comm<strong>on</strong> staple foods with<br />

ir<strong>on</strong>, <strong>and</strong> changes in food preparati<strong>on</strong> methods<br />

(e.g., fermentati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> germinati<strong>on</strong>)<br />

are used, with the choice of approach dependent<br />

<strong>on</strong> setting, populati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>and</strong> practical<br />

c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s. There are currently major<br />

efforts worldwide to combat ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the areas <strong>and</strong> number of people<br />

reached are rapidly increasing.<br />

The causes for ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency are wellknown.<br />

A low ir<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tent of the diet is comm<strong>on</strong><br />

as is a low bioavailability of the ir<strong>on</strong> in<br />

the diets c<strong>on</strong>sumed. This is compounded by<br />

rapid growth (<strong>and</strong> tissue synthesis) in infants<br />

<strong>and</strong> children, menstrual losses of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

in fertile women, <strong>and</strong> fetal dem<strong>and</strong>s for ir<strong>on</strong><br />

in pregnant women. The low bioavailability<br />

of dietary ir<strong>on</strong> is often caused by a high intake<br />

of phytate in cereals, rice, <strong>and</strong> legumes,<br />

which inhibits ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>, <strong>and</strong> a low<br />

proporti<strong>on</strong> of meat in the diet, which provides<br />

absorbable ir<strong>on</strong> in the form of heme<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> (Hallberg 1981). Much less recognized<br />

is that the factors limiting ir<strong>on</strong> nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

have similar effects <strong>on</strong> zinc nutriti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Infants, children, <strong>and</strong> fertile women<br />

also have high requirements for zinc, <strong>and</strong><br />

the factors inhibiting ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> often<br />

have an even more pr<strong>on</strong>ounced negative effect<br />

<strong>on</strong> zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong>. Similar to the situati<strong>on</strong><br />

for ir<strong>on</strong>, meat is the best dietary source<br />

of zinc. Because the usual meat intake of<br />

many populati<strong>on</strong>s is very low, their zinc intake<br />

is also very low. A lack of data <strong>on</strong> zinc<br />

nutriti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> the difficulties in assessing zinc<br />

status, particularly marginal zinc status,<br />

have led to zinc deficiency not being recognized<br />

as a major nutriti<strong>on</strong>al problem in lessdeveloped<br />

countries (King 1990). However,<br />

when attempts are made to assess both ir<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> zinc status, the prevalence of zinc deficiency<br />

appears to be similar to that of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

deficiency.<br />

In a recent study of pregnant women in<br />

Lima, Peru, we found that 60% of the women<br />

were anemic <strong>and</strong> about 55% had low zinc<br />

status as assessed by lower than normal serum<br />

zinc c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s (N. Zavaleta, B.<br />

Lönnerdal, K.H. Brown, unpublished observati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

1994). Further, in a study of 1year-old<br />

Swedish infants, we found that 35%<br />

had low serum ferritin c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

29% had low serum zinc c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

(L.A. Perss<strong>on</strong>, M. Lundstrom, B. Lönnerdal,<br />

3

O. Hernell, unpublished observati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

1995). These infants had a high intake of<br />

unrefined cereals, which may have affected<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> negatively. Thus,<br />

there may be good reas<strong>on</strong>s to provide zinc<br />

al<strong>on</strong>g with ir<strong>on</strong>.<br />

A potential problem of supplementing<br />

both ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc is that supplemental ir<strong>on</strong><br />

may inhibit zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong>, which then has<br />

to be taken into account when making programmatic<br />

decisi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> modality <strong>and</strong> dosages.<br />

Furthermore, ir<strong>on</strong> may affect copper<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc can inhibit copper absorpti<strong>on</strong>,<br />

making it possible that combined<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc supplementati<strong>on</strong> or fortificati<strong>on</strong><br />

may interfere with copper absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> status even if copper intake normally is<br />

not an area of c<strong>on</strong>cern. This paper will discuss<br />

the potential effects of adding ir<strong>on</strong>, zinc,<br />

or both <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong>, zinc, <strong>and</strong> copper nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> possible ways to minimize potential interacti<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Types of Trace Element<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

There are two fundamentally different types<br />

of trace element interacti<strong>on</strong>s that can occur<br />

in biological systems (Lönnerdal <strong>and</strong> Keen<br />

1983). In the first type, two (or more) trace<br />

elements share the same absorptive pathways.<br />

This means that high c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of <strong>on</strong>e element may interfere with the absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

of another element. The c<strong>on</strong>ceptual<br />

framework for this type of interacti<strong>on</strong><br />

was provided by Hill <strong>and</strong> Matr<strong>on</strong>e (1970),<br />

who postulated that elements that have a<br />

similar coordinati<strong>on</strong> number <strong>and</strong> a similar<br />

c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong> in water soluti<strong>on</strong> can compete<br />

for absorptive pathways. Through experiments<br />

in animals, they dem<strong>on</strong>strated<br />

that essential elements such as zinc <strong>and</strong> copper<br />

can interact <strong>and</strong> that an excess of <strong>on</strong>e<br />

element can induce a deficiency of the other.<br />

They also dem<strong>on</strong>strated that a toxic element<br />

4<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

like cadmium can inhibit the absorpti<strong>on</strong> of<br />

an essential element like zinc. This type of<br />

interacti<strong>on</strong> is well recognized <strong>and</strong> even used<br />

in some clinical applicati<strong>on</strong>s, such as the<br />

treatment of Wils<strong>on</strong>’s patients with high<br />

doses of zinc (Brewer et al. 1983).<br />

The sec<strong>on</strong>d type of interacti<strong>on</strong> occurs<br />

when a deficiency of <strong>on</strong>e element affects the<br />

metabolism of another element, as shown<br />

by the example of copper deficiency that<br />

causes ir<strong>on</strong>-deficiency anemia (Cohen et al.<br />

1985). Because copper is an essential comp<strong>on</strong>ent<br />

of ceruloplasmin, or as it more accurately<br />

should be called, ferroxidase I, copper<br />

deficiency causes a dramatic decrease in<br />

ferroxidase activity, which in turn prevents<br />

the mobilizati<strong>on</strong> of ir<strong>on</strong> from stores (by being<br />

oxidized from +2 to +3) <strong>and</strong> its incorporati<strong>on</strong><br />

into hemoglobin. Another example<br />

is the homeostatic up-regulati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> that occurs during ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency.<br />

This up-regulati<strong>on</strong> also dramatically<br />

increases the absorpti<strong>on</strong> both of essential<br />

elements, such as manganese, <strong>and</strong> toxic elements,<br />

such as cadmium (Flanagan et al.<br />

1980).<br />

From a programmatic viewpoint, the<br />

first type of interacti<strong>on</strong> is the most important<br />

to c<strong>on</strong>sider; that is, if supplements of<br />

<strong>on</strong>e (or several) elements are to be used, can<br />

this create adverse effects <strong>on</strong> the utilizati<strong>on</strong><br />

of other essential elements? However, the<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>d type of interacti<strong>on</strong> should also be<br />

c<strong>on</strong>sidered because a preexisting impairment<br />

in status of <strong>on</strong>e trace element (which is not<br />

being studied) may have a pr<strong>on</strong>ounced effect<br />

<strong>on</strong> the outcome of a study <strong>and</strong> therefore<br />

affect the evaluati<strong>on</strong> of outcomes.<br />

Trace Element Deficiencies in a<br />

Global Perspective<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency is comm<strong>on</strong> in most parts of<br />

the world. There are few reports <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong><br />

deficiency affecting zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> or me-

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

tabolism, but this issue has not been studied<br />

extensively. The effects of ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency <strong>on</strong><br />

copper absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> metabolism have not<br />

been studied extensively either, but the limited<br />

data available do not indicate a pr<strong>on</strong>ounced<br />

effect. As suggested above, zinc deficiency<br />

may be comm<strong>on</strong> in the same populati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

that are pr<strong>on</strong>e to ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency. Zinc<br />

deficiency does not appear to have any pr<strong>on</strong>ounced<br />

effect <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> or metabolism,<br />

but some reports suggest that copper<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> may increase when zinc status<br />

is impaired, even if the deficiency is <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

marginal (Polberger et al. 1996). There are<br />

limited data supporting a high prevalence<br />

of copper deficiency in less-developed countries;<br />

however, infants fed milk-based diets<br />

may have compromised copper status as a<br />

result of the low copper c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> of<br />

milk <strong>and</strong> dairy products (Levy et al. 1985).<br />

Marginal copper status can affect ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> status <strong>and</strong>, c<strong>on</strong>sequently, the<br />

outcome of ir<strong>on</strong> supplementati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> fortificati<strong>on</strong><br />

programs. Less is known about the<br />

effects of low copper status <strong>on</strong> zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> status.<br />

Trace Element Ratios<br />

Because high c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>on</strong>e element<br />

may interfere with the absorpti<strong>on</strong> of another<br />

element, it is important to c<strong>on</strong>sider<br />

the ratios between trace elements. For example,<br />

breast milk c<strong>on</strong>tains ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc at<br />

a ratio of approximately 1:4 whereas ir<strong>on</strong>fortified<br />

milk (or formula) may have a ratio<br />

of 12:1 (Lönnerdal et al. 1983). When c<strong>on</strong>sidering<br />

competiti<strong>on</strong> for absorptive pathways,<br />

it should be recognized that the ir<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> of the diet in fortificati<strong>on</strong><br />

programs may be increased 50–60 times (or<br />

more) while the zinc c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> remains<br />

unchanged.<br />

Although not as pr<strong>on</strong>ounced, the ratio<br />

of zinc to copper can also be raised c<strong>on</strong>sid-<br />

erably by zinc fortificati<strong>on</strong>. To date, this is<br />

largely c<strong>on</strong>fined to infant formulas, in which<br />

the zinc-copper ratio can be as high as 70:1<br />

whereas this ratio is approximately 5:1 in<br />

breast milk (Lönnerdal et al. 1983). It can<br />

be expected that zinc supplements will become<br />

more comm<strong>on</strong>ly used <strong>and</strong> that more<br />

diets will be fortified with zinc. Thus, it is<br />

evident that zinc nutriture should be m<strong>on</strong>itored<br />

when ir<strong>on</strong> is added to the diet <strong>and</strong> that<br />

copper nutriture should be m<strong>on</strong>itored<br />

when ir<strong>on</strong> or zinc is added to the diet.<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Although ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc do not form similar<br />

coordinati<strong>on</strong> complexes in water soluti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> were not believed to directly compete<br />

for absorptive sites, Solom<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Jacob<br />

(1981) showed that high levels of ir<strong>on</strong> can<br />

interfere with zinc uptake as measured by<br />

changes in serum zinc after dosing (area<br />

under the curve). The postpr<strong>and</strong>ial rise in<br />

serum zinc after an oral dose of 25 mg zinc<br />

in water soluti<strong>on</strong> was given to fasting subjects<br />

was lower when 25 mg of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

(ir<strong>on</strong>:zinc, 1:1) was given with the zinc dose<br />

than when zinc was given al<strong>on</strong>e. Increasing<br />

the ir<strong>on</strong> dose to 50 (2:1 ratio) <strong>and</strong> 75 mg<br />

(3:1 ratio) reduced zinc uptake even further.<br />

The dose of zinc given was high so that a<br />

measurable increase in plasma zinc would<br />

occur, <strong>and</strong> it has been argued that pharmacological<br />

amounts of zinc <strong>and</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> were<br />

used. However, when supplements of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> zinc are given to treat deficiencies, the<br />

doses used are not very different from those<br />

used by Solom<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Jacob (1981). In a<br />

subsequent study we used a lower amount<br />

of zinc, which was more similar to the zinc<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tent of a regular meal (2.6 mg), <strong>and</strong> zinc<br />

radioisotope <strong>and</strong> whole-body counting to<br />

measure zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> (S<strong>and</strong>ström et al.<br />

1985). At this zinc level, there was no difference<br />

in zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> when the ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc<br />

5

atio was changed from 1:1 to 2.5:1; whereas<br />

zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> decreased from 60% to 38%<br />

when a molar ratio of 25:1 was used. It is not<br />

yet known whether the difference in results<br />

between our study <strong>and</strong> the <strong>on</strong>e by Solom<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> Jacob is due to the lower amounts of<br />

zinc <strong>and</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> used or whether plasma zinc<br />

uptake yields different results from wholebody<br />

counting.<br />

The interacti<strong>on</strong> between ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc<br />

in water soluti<strong>on</strong> is relevant to the situati<strong>on</strong><br />

when combined ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc supplements<br />

are given in a fasting state. To explore<br />

whether the same interacti<strong>on</strong> occurs when<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> is given with meals, either as a supplement<br />

or as ir<strong>on</strong>-fortified food, we gave human<br />

subjects the same quantities of ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

zinc as described above in the form of a single<br />

meal (S<strong>and</strong>ström et al. 1985). There were<br />

no significant differences am<strong>on</strong>g groups<br />

when ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc molar ratios of 1:1, 2.5:1,<br />

<strong>and</strong> 25:1 were used. Thus, there appears to<br />

be no interacti<strong>on</strong> between these two elements<br />

when they are given in a meal. To investigate<br />

whether the difference in results between giving<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc in a water soluti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> in<br />

a meal is due to the absence or presence of<br />

lig<strong>and</strong>s binding zinc or ir<strong>on</strong>, we added histidine<br />

to the water soluti<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>taining ir<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> zinc. In the presence of histidine, there<br />

were no significant differences observed in<br />

zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g groups receiving<br />

ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc ratios of 1:1, 2.5:1, <strong>and</strong> 25:1. We<br />

therefore suggest that when a dietary lig<strong>and</strong><br />

that can chelate zinc (e.g., histidine) is<br />

present, zinc will be absorbed via a pathway<br />

that is not affected by the ir<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong><br />

in the gut. However, when no dietary<br />

lig<strong>and</strong>s are present, ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc may compete<br />

for comm<strong>on</strong> binding sites at the mucosal<br />

surface, <strong>and</strong> a high level of <strong>on</strong>e element<br />

interferes with the uptake of the other. This<br />

is c<strong>on</strong>sistent with our earlier observati<strong>on</strong><br />

that infants given daily ir<strong>on</strong> drops (30 mg)<br />

had zinc status (as assessed by plasma zinc)<br />

after 3 m<strong>on</strong>ths of treatment similar to that<br />

of infants given placebo (Yip et al. 1985).<br />

6<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

The ir<strong>on</strong> was given apart from meals <strong>and</strong> no<br />

interacti<strong>on</strong> between ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc could occur.<br />

That the interacti<strong>on</strong> is likely to occur at<br />

the level of absorpti<strong>on</strong> is supported by our<br />

observati<strong>on</strong> that prior ir<strong>on</strong>-loading of human<br />

subjects with 50 mg/day for 2 weeks had<br />

no effect <strong>on</strong> zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> (S<strong>and</strong>ström et<br />

al. 1985). Supporting this observati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

Fairweather-Tait et al. (1995) recently reported<br />

that ir<strong>on</strong>-fortified foods had no effects<br />

<strong>on</strong> zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> in infants, <strong>and</strong> similar<br />

obervati<strong>on</strong>s were made by Davidss<strong>on</strong> et<br />

al. (1995) in adults.<br />

To investigate whether high levels of zinc<br />

can interfere with ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>, we gave<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc at different levels, in either<br />

water soluti<strong>on</strong> or part of a meal, to human<br />

subjects <strong>and</strong> measured ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> by a<br />

radioisotope method (Ross<strong>and</strong>er-Hulthén<br />

et al. 1991). No effect <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

was found for either method of administrati<strong>on</strong><br />

even when a 300:1 molar excess of zinc<br />

to ir<strong>on</strong> was used. Thus, it appears that ir<strong>on</strong><br />

uptake is not affected by excess zinc whereas<br />

excess ir<strong>on</strong> can affect zinc uptake when ir<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> zinc are given together in a water soluti<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> in a fasting state.<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

An interacti<strong>on</strong> between ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> copper is<br />

usually believed to occur by the mechanism<br />

described above, that is, by copper deficiency<br />

causing low ferroxidase activity <strong>and</strong><br />

inducing ir<strong>on</strong>-deficiency anemia. There is<br />

little support for copper deficiency being a<br />

comm<strong>on</strong> nutriti<strong>on</strong>al problem in less-developed<br />

countries. However, this may be due<br />

to a lack of data rather than to studies dem<strong>on</strong>strating<br />

an absence of impaired copper<br />

nutriti<strong>on</strong>. Infants <strong>and</strong> children c<strong>on</strong>suming<br />

predominantly milk-based diets may have<br />

marginal copper status even if the impairment<br />

in copper status is not severe enough<br />

to cause anemia. Another c<strong>on</strong>cern is that

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

high ir<strong>on</strong> intakes may interfere with copper<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

In a balance study, infants fed formula<br />

having a low ir<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> (2.5 mg/L)<br />

were shown to have higher copper absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

than infants fed the same formula but<br />

with a higher ir<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> (10.2 mg/<br />

L) (Haschke et al. 1986). In additi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

Barclay et al. (1991) found lower copper status<br />

(as measured by red cell superoxide<br />

dismutase) in premature infants given ir<strong>on</strong><br />

supplements. We subsequently showed that<br />

infants fed a formula c<strong>on</strong>taining 7 mg ir<strong>on</strong>/<br />

L had a lower serum copper c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong><br />

than did infants fed the same formula c<strong>on</strong>taining<br />

4 mg ir<strong>on</strong>/L (Lönnerdal <strong>and</strong> Hernell<br />

1994). Ir<strong>on</strong>-deficient children given ir<strong>on</strong><br />

supplements for 2 weeks were reported to<br />

have decreased serum copper <strong>and</strong> ceruloplasmin<br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s (Morais et al. 1994).<br />

In the last two studies, serum copper c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

were still within the normal<br />

range. Thus, it appears that the level of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

intake affects copper absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> status<br />

even when the differences in ir<strong>on</strong>-copper<br />

ratios are relatively small.<br />

Similar to what was described above for<br />

the interacti<strong>on</strong> between ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc, it is<br />

likely that ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> copper need to be ingested<br />

together for an effect to occur. In our<br />

study <strong>on</strong> infants given daily ir<strong>on</strong> drops apart<br />

from meals for 3 m<strong>on</strong>ths (Yip et al. 1985),<br />

we found no adverse effects <strong>on</strong> copper status<br />

as assessed by serum copper c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

Zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

A negative effect of high c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of<br />

zinc <strong>on</strong> the copper status of experimental<br />

animals was described by Hill <strong>and</strong> Matr<strong>on</strong>e<br />

(1970). High c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of zinc had been<br />

thought to induce synthesis of metallothi<strong>on</strong>ein,<br />

a protein that has a high capacity to<br />

bind copper as well as zinc (Hall et al. 1979).<br />

Thus, a so-called mucosal block for copper<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> was created. Recent work, however,<br />

indicates that the level of zinc required<br />

to induce metallothi<strong>on</strong>ein is very high <strong>and</strong><br />

may be c<strong>on</strong>sidered unphysiological<br />

(Oestreicher <strong>and</strong> Cousins 1985). Therefore,<br />

this inducti<strong>on</strong> may not occur at the normal<br />

range of zinc intakes even if zinc supplements<br />

are given. It is obvious, however, that high<br />

levels of zinc interfere with copper absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

in the small intestine.<br />

In a study by Wapnir <strong>and</strong> Lee (1993),<br />

the removal rate of copper from perfused<br />

rat jejunum was significantly lower than<br />

normal when dietary zinc amounts were high<br />

<strong>and</strong> even lower when the zinc was given together<br />

with histidine, a chelator of zinc<br />

known to enhance its absorpti<strong>on</strong>. The pr<strong>on</strong>ounced<br />

negative effect of high c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of zinc <strong>on</strong> copper absorpti<strong>on</strong> has been<br />

recognized in human subjects <strong>and</strong> is used in<br />

the treatment of Wils<strong>on</strong>’s disease, a genetic<br />

disorder of abnormally high copper absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

(Brewer et al. 1983).<br />

Modest increases in zinc intake may affect<br />

copper absorpti<strong>on</strong> in humans. The two<br />

elements are likely to be, at least in part,<br />

transported by the same pathway in the<br />

enterocyte, <strong>and</strong> although metallothi<strong>on</strong>ein<br />

may not be induced, they may compete for<br />

a comm<strong>on</strong> carrier. In a study in which infant<br />

rhesus m<strong>on</strong>keys were fed formula with<br />

two different c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s of zinc (1 <strong>and</strong><br />

4 mg/L), m<strong>on</strong>keys with a lower zinc intake<br />

had a significantly higher plasma copper<br />

c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> (Polberger et al. 1996).<br />

Plasma copper c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s were, however,<br />

within the normal range in both<br />

groups, <strong>and</strong> animals with a lower zinc intake<br />

may have had enhanced copper absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

rather than those with the higher level<br />

having had decreasing copper absorpti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

In any case, the results dem<strong>on</strong>strate that zinc<br />

<strong>and</strong> copper interact, even at fairly small<br />

changes in their ratio.<br />

In a recent study of infant rhesus m<strong>on</strong>keys<br />

fed soy formula, we found that when<br />

7

the phytate c<strong>on</strong>tent of the formula was reduced,<br />

zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> increased significantly<br />

whereas serum copper decreased<br />

(Lönnerdal et al. 1996). Although serum<br />

copper did not decrease precipitously in our<br />

infant m<strong>on</strong>key model, it should be recognized<br />

that marginal copper deficiency does<br />

not have a pr<strong>on</strong>ounced effect <strong>on</strong> serum copper<br />

or other indices (Turnlund et al. 1990).<br />

Thus, the relatively minor but significant<br />

decrease in serum copper may indicate a<br />

more severe depleti<strong>on</strong> of copper at the tissue<br />

level. It is evident that more sensitive indicators<br />

of copper deficiency are needed.<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

It is evident from the discussi<strong>on</strong> above that<br />

both ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc may be chosen for micr<strong>on</strong>utrient<br />

interventi<strong>on</strong>s, either as a supplement<br />

or a fortificant. It can also be envisi<strong>on</strong>ed<br />

that in many locati<strong>on</strong>s the provisi<strong>on</strong><br />

of ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc will allow for the treatment<br />

of existing deficiencies <strong>and</strong> not <strong>on</strong>ly be a preventive<br />

measure. Therefore, relatively generous<br />

doses of ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc may be used.<br />

For infants, ir<strong>on</strong> is often given at a dosage of<br />

5 mg/kg/day <strong>and</strong> zinc at about 10–15 mg/<br />

day. A 6-kg infant for example may c<strong>on</strong>sequently<br />

receive 45 mg of ir<strong>on</strong> plus zinc, which<br />

is c<strong>on</strong>siderably higher than the customary<br />

copper intake of 0.5–1 mg/day (or less) at<br />

this age. This dramatic change in the ratio<br />

of ir<strong>on</strong> plus zinc to copper may have a detrimental<br />

effect <strong>on</strong> copper absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> status.<br />

Few studies have evaluated the effects<br />

of combined ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc supplements <strong>on</strong><br />

copper nutriti<strong>on</strong> in humans. However, <strong>on</strong>e<br />

report <strong>on</strong> adult women given 50 mg of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> 50 mg of zinc daily for 10 weeks showed<br />

decreased red cell superoxide dismutase activities,<br />

suggesting that this interacti<strong>on</strong><br />

should be studied further (Yadrick et al.<br />

1989).<br />

8<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

The three essential trace elements ir<strong>on</strong>, zinc,<br />

<strong>and</strong> copper are known to interact with each<br />

other. However, most studies have been performed<br />

in rodent models, have used pr<strong>on</strong>ounced<br />

differences in element ratios for the<br />

different test groups, <strong>and</strong> have been of relatively<br />

short durati<strong>on</strong>. From a programmatic<br />

view it is more relevant to evaluate the effects<br />

of moderately increased intakes of these<br />

elements for extended time periods in vulnerable<br />

groups. Although interacti<strong>on</strong>s are<br />

more likely to occur when the elements are<br />

given as a supplement, the modality (i.e.,<br />

giving them with a meal or between meals)<br />

may affect outcome drastically. Although<br />

somewhat more difficult from a practical<br />

point of view (compliance, toxicity risk,<br />

etc.), giving the elements alternating days<br />

(e.g., <strong>on</strong>e weekly vs. the other daily) needs<br />

to be explored in various settings.<br />

Providing ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> zinc to vulnerable<br />

groups can have pr<strong>on</strong>ounced positive effects<br />

<strong>on</strong> several outcomes, but this should not<br />

overshadow the potential negative effects <strong>on</strong><br />

other outcomes. This is particularly important<br />

when it comes to morbidity; giving<br />

modest amounts of zinc may have a positive<br />

effect <strong>on</strong> immune functi<strong>on</strong> (Schlesinger et<br />

al. 1992) whereas somewhat higher amounts<br />

may interfere with copper <strong>and</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>,<br />

creating suboptimal copper <strong>and</strong> ir<strong>on</strong><br />

status, which in turn may have a negative<br />

effect <strong>on</strong> immune functi<strong>on</strong> (S<strong>and</strong>ström et<br />

al. 1994). Thus, the apparent lack of effect of<br />

zinc <strong>on</strong> morbidity may discourage efforts to<br />

provide zinc to groups that do need it.<br />

A careful approach with graded dosages<br />

of micr<strong>on</strong>utrients provided al<strong>on</strong>e or in<br />

combinati<strong>on</strong>, as supplements or food<br />

fortificants, <strong>and</strong> with careful m<strong>on</strong>itoring of<br />

not just the micr<strong>on</strong>utrient being studied is<br />

necessary to avoid misinterpretati<strong>on</strong>s that

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

could have l<strong>on</strong>g-ranging negative impact <strong>on</strong><br />

programs worldwide.<br />

References<br />

Barclay SM, Aggett PJ, Lloyd DJ, Duffty P (1991) Reduced<br />

erythrocyte superoxide dismutase activity in<br />

low birth weight infants given ir<strong>on</strong> supplements.<br />

Pediatr Res 29:297-301<br />

Brewer GJ, Hill GM, Prasad AS, et al (1983) Oral zinc<br />

therapy for Wils<strong>on</strong>’s disease. Ann Intern Med<br />

99:314–20<br />

Cohen NL, Keen CL, Lönnerdal B, Hurley LS (1985)<br />

Effects of varying dietary ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the expressi<strong>on</strong> of<br />

copper deficiency in the growing rat: anemia,<br />

ferroxidase I <strong>and</strong> II, tissue trace elements, ascorbic<br />

acid, <strong>and</strong> xanthine dehydrogenase. J Nutr 115:633–<br />

649<br />

Dallman PR, Siimes MA, Stekel A (1980) Ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency<br />

in infancy <strong>and</strong> childhood. Am J Clin Nutr<br />

33:86–118<br />

Davidss<strong>on</strong> L, Almgren A, S<strong>and</strong>ström B, Hurrell RF<br />

(1995) Zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong> in adult humans: the effect<br />

of ir<strong>on</strong> fortificati<strong>on</strong>. Br J Nutr 74:417–425<br />

Fairweather-Tait SJ, Wharf SG, Fox TE (1995) Zinc<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> in infants fed ir<strong>on</strong>-fortified weaning food.<br />

Am J Clin Nutr 62:785–789<br />

Flanagan PR, Haist J, Valberg LS (1980) Comparative<br />

effects of ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency induced by bleeding <strong>and</strong> a<br />

low-ir<strong>on</strong> diet <strong>on</strong> the intestinal absorptive interacti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of ir<strong>on</strong>, cobalt, manganese, zinc, lead <strong>and</strong><br />

cadmium. J Nutr 110:1754–1763<br />

Hall AC, Young BW, Bremner I (1979) Intestinal<br />

metallothi<strong>on</strong>ein <strong>and</strong> the mutual antag<strong>on</strong>ism between<br />

copper <strong>and</strong> zinc in the rat. J In<strong>org</strong> Biochem 11:66–<br />

67<br />

Hallberg L (1981) Bioavailability of dietary ir<strong>on</strong> in<br />

man. Annu Rev Nutr 1:123–147<br />

Haschke F, Ziegler EE, Edwards BB, Fom<strong>on</strong> SJ (1986)<br />

Effect of ir<strong>on</strong> fortificati<strong>on</strong> of infant formula <strong>on</strong> trace<br />

mineral absorpti<strong>on</strong>. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr<br />

5:768–773<br />

Hill CH, Matr<strong>on</strong>e G (1970) Chemical parameters in<br />

the study of in vivo <strong>and</strong> in vitro interacti<strong>on</strong>s of transiti<strong>on</strong><br />

elements. Fed Proc 29:1474–1481<br />

King JC (1990) Assessment of zinc status. J Nutr<br />

120:1474–1479<br />

Levy Y, Zeharia A, Grunebaum M, (1985) Copper<br />

deficiency in infants fed cow milk. J Pediatr<br />

1985;106:786-788<br />

Lönnerdal B, Dewey KG (1995) Epidemiology of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

deficiency in infants <strong>and</strong> children. Ann Nestlé 53:11–<br />

17<br />

Lönnerdal B, Hernell O (1994) Ir<strong>on</strong>, zinc, copper <strong>and</strong><br />

selenium status of breast-fed infants <strong>and</strong> infants fed<br />

trace element fortified milk-based infant formula.<br />

Acta Paediatr 83:367–373<br />

Lönnerdal B, Keen CL (1983) Trace element absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

in infants: potentials <strong>and</strong> limitati<strong>on</strong>s. In Clarks<strong>on</strong><br />

TW, Nordberg GF, Sager PR (eds), Reproductive <strong>and</strong><br />

developmental toxicity of metals. Plenum Press, New<br />

York, pp 759–776<br />

Lönnerdal B, Jayawickrama L, Lien EL (1996) Effect of<br />

low phytate soy formula <strong>on</strong> zinc <strong>and</strong> copper absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

[abstract]. FASEB J 10:A818<br />

Lönnerdal B, Keen CL, Ohtake M, Tamura T (1983)<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>, zinc, copper, <strong>and</strong> manganese in infant formulas.<br />

Am J Dis <strong>Child</strong> 137:433-437<br />

Morais MB, Fisberg M, Suzuki HU, et al (1994) Effects<br />

of oral ir<strong>on</strong> therapy <strong>on</strong> serum copper <strong>and</strong> serum<br />

ceruloplasmin in children. J Trop Pediatr 40:51-52<br />

Oestreicher P, Cousins RJ (1985) Copper <strong>and</strong> zinc<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> in the rat: mechanism of mutual antag<strong>on</strong>ism.<br />

J Nutr 115:159–166<br />

Polberger S, Fletcher MP, Graham TW, et al (1996)<br />

Effect of infant formula zinc <strong>and</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> level <strong>on</strong> zinc<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong>, zinc status, <strong>and</strong> immune functi<strong>on</strong> in infant<br />

rhesus m<strong>on</strong>keys. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr<br />

22:134–143<br />

Ross<strong>and</strong>er-Hulthén L, Brune M, S<strong>and</strong>ström B, et al<br />

(1991) Competitive inhibiti<strong>on</strong> of ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

by manganese <strong>and</strong> zinc in humans. Am J Clin Nutr<br />

54:152–156<br />

S<strong>and</strong>ström B, Davidss<strong>on</strong> L, Cederblad Å, Lönnerdal B<br />

(1985) Oral ir<strong>on</strong>, dietary lig<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> zinc absorpti<strong>on</strong>.<br />

J Nutr 115:411–414<br />

S<strong>and</strong>ström B, Cederblad Å, Lindblad B, Lönnerdal B<br />

(1994) Acrodermatitis enteropathica, zinc metabolism,<br />

copper status <strong>and</strong> immune functi<strong>on</strong>. Arch<br />

Pediatr Adolesc Med 148:980–985<br />

Schlesinger L, Arevalo M, Arred<strong>on</strong>do S, et al (1992)<br />

Effect of a zinc-fortified formula <strong>on</strong> immunocompetence<br />

<strong>and</strong> growth of malnourished infants. Am J<br />

Clin Nutr 56:491–498<br />

Solom<strong>on</strong>s NW, Jacob RA (1981) Studies <strong>on</strong> the<br />

bioavailability of zinc in humans: effect of heme<br />

<strong>and</strong> n<strong>on</strong>heme ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> the absorpti<strong>on</strong> of zinc. Am J<br />

Clin Nutr 34:475–482<br />

Turnlund JR, Keen CL, Smith RG (1990) Copper status<br />

<strong>and</strong> urinary <strong>and</strong> salivary copper in young men at<br />

three levels of dietary copper. Am J Clin Nutr<br />

51:658–664.<br />

Walter T (1993) <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> of ir<strong>on</strong> deficiency <strong>on</strong> cogniti<strong>on</strong><br />

in infancy <strong>and</strong> childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr<br />

47:307–316<br />

Wapnir RA, Lee SY (1993) Dietary regulati<strong>on</strong> of copper<br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> storage in rats: effects of sodium,<br />

zinc <strong>and</strong> histidine-zinc. J Am Coll Nutr<br />

12:714-719<br />

9

Yadrick MK, Kenney MA, Winterfeldt EA (1989) Ir<strong>on</strong>,<br />

copper, <strong>and</strong> zinc status: resp<strong>on</strong>se to supplementati<strong>on</strong><br />

with zinc or zinc <strong>and</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> in adult females. Am<br />

J Clin Nutr 49:145–150<br />

10<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

Yip R, Reeves JD, Lönnerdal B, et al (1985) Does ir<strong>on</strong><br />

supplementati<strong>on</strong> compromise zinc nutriti<strong>on</strong> in<br />

healthy infants? Am J Clin Nutr 42:683–687

Ir<strong>on</strong>-zinc-copper <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ir<strong>on</strong>–ascorbic Acid <strong>and</strong> Ir<strong>on</strong>-calcium<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> Their Relevance in<br />

Complementary Feeding<br />

Lindsay H. Allen<br />

Department of Nutriti<strong>on</strong>, University of California, Davis, CA 95616<br />

Ascorbic acid <strong>and</strong> calcium have opposite<br />

effects <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>; ascorbic acid<br />

improves the absorpti<strong>on</strong> of naturally<br />

occurring or fortificant n<strong>on</strong>heme ir<strong>on</strong><br />

in foods whereas calcium inhibits the absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

of both heme <strong>and</strong> n<strong>on</strong>heme ir<strong>on</strong>. The<br />

effects of ascorbic acid <strong>and</strong> calcium <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong><br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> will be c<strong>on</strong>sidered separately,<br />

followed by a discussi<strong>on</strong> of the practical implicati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

of these interacti<strong>on</strong>s for complementary<br />

feeding.<br />

Ir<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Ascorbic Acid<br />

Ascorbic acid is a str<strong>on</strong>g enhancer of n<strong>on</strong>heme-ir<strong>on</strong><br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong>. The mechanisms for<br />

this absorpti<strong>on</strong> enhancement include the<br />

reducti<strong>on</strong> of dietary ferric ir<strong>on</strong> to its betterabsorbed<br />

ferrous form <strong>and</strong> the formati<strong>on</strong><br />

of an ir<strong>on</strong>–ascorbic acid chelate in the acid<br />

milieu of the stomach. The chelate is formed<br />

at a lower pH than that at which ir<strong>on</strong> complexes<br />

with phytate, tannins, <strong>and</strong> other inhibitors<br />

of ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>. Thus, ferrous<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> is preferentially bound to ascorbic acid<br />

in the stomach <strong>and</strong> remains in this complex<br />

even in the more alkaline pH of the intestine.<br />

The overall effect is to reduce the influence<br />

of inhibitory lig<strong>and</strong>s that would otherwise<br />

bind ir<strong>on</strong> in the duodenum (Hurrell<br />

1984). Although ascorbic acid does not enhance<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> from most ferrous<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> supplements in the absence of meals, it<br />

increases the bioavailability of ferrous ir<strong>on</strong><br />

added as a fortificant to foods, especially<br />

when those foods c<strong>on</strong>tain a large amount of<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> inhibitors. This is true<br />

whether the fortificant ir<strong>on</strong> is a simple ferrous<br />

salt or a chelate such as NaFeEDTA.<br />

Even less-bioavailable ir<strong>on</strong> salts, such as ferric<br />

orthophosphate <strong>and</strong> ferric pyrophosphate,<br />

are reas<strong>on</strong>ably well-absorbed in the<br />

presence of ascorbic acid.<br />

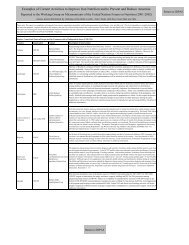

We recently reviewed studies in which<br />

ascorbic acid was added to meals based <strong>on</strong><br />

maize, wheat, <strong>and</strong> rice (Allen <strong>and</strong> Ahluwahlia<br />

1996). Figure 1 presents, for each<br />

study, the mean ratio of ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> in<br />

the presence vs absence of ascorbic acid at<br />

each c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong> of ascorbic acid. Absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

of the reference dose of ir<strong>on</strong> in each<br />

study was used to correct for differences in<br />

the efficiency of ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> caused by<br />

differences in ir<strong>on</strong> status am<strong>on</strong>g subjects. It<br />

is evident from Figure 1 that ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

from meals approximately doubles<br />

when 25 mg ascorbic acid is added <strong>and</strong> increases<br />

three- to sixfold when 50 mg is added.<br />

The relati<strong>on</strong> between ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

ascorbic acid appears to be linear up to at<br />

least 100 mg ascorbic acid per meal.<br />

11

Figure 1. Effect of ascorbic<br />

acid <strong>on</strong> n<strong>on</strong>heme ir<strong>on</strong><br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> from cereal<br />

based diets. rice,<br />

wheat, maize.<br />

Abs Ratio (with/without)<br />

Because ascorbic acid releases n<strong>on</strong>heme<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> bound to inhibitors, the most marked<br />

effects are seen when it is added to foods with<br />

a high c<strong>on</strong>tent of phytates, such as maize,<br />

whole wheat, <strong>and</strong> soya, or to foods high in<br />

polyphenols such as tannic acid (Siegenberg<br />

et al. 1991, Derman et al. 1977). This relati<strong>on</strong><br />

was illustrated for a variety of diets by<br />

Hallberg et al. (1986). The stimulatory effect<br />

of 50 mg ascorbic acid was less when the<br />

ascorbic acid was added to a breakfast<br />

(wheat roll, cheese, <strong>and</strong> coffee) or a hamburger<br />

meal, intermediate when it was added<br />

to a Thai rice meal, <strong>and</strong> highest when it was<br />

added to a Latin American meal (high in<br />

phytate from maize <strong>and</strong> polyphenols from<br />

beans). However, even though the enhancing<br />

effect of ascorbic acid <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

is relatively greater in the presence of<br />

inhibitors, as the c<strong>on</strong>tent of inhibitors increases,<br />

more ascorbic acid is needed to overcome<br />

the inhibitory effects.<br />

Protein from meat, fish, <strong>and</strong> poultry<br />

also enhances ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>. In general, 1<br />

mg ascorbic acid is equivalent to about 1–<br />

1.5 g meat in its ability to enhance n<strong>on</strong>heme<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> (Hallberg <strong>and</strong> Ross<strong>and</strong>er<br />

1984). The stimulatory effect of the natural<br />

ascorbic acid in foods is similar to that of<br />

synthetic ascorbic acid. For example, when<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Micr<strong>on</strong>utrient</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g>: <str<strong>on</strong>g>Impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Child</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong> Nutriti<strong>on</strong><br />

0<br />

10 100 1000<br />

Ascorbic Acid (mg)<br />

ascorbic acid was added in the form of vegetable<br />

salad, cauliflower, or orange juice to<br />

a hamburger meal, the relative increase in<br />

ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> was very similar to that<br />

caused by c<strong>on</strong>suming 25–500 mg synthetic<br />

ascorbic acid per meal (Hallberg et al. 1986).<br />

Effects of L<strong>on</strong>g-term Ascorbic Acid<br />

Supplementati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Body Ir<strong>on</strong> Stores<br />

Most investigators have measured the effect<br />

of ascorbic acid <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> from<br />

single meals. Fewer, less-c<strong>on</strong>clusive data exist<br />

<strong>on</strong> the effect of a l<strong>on</strong>ger-term higher ascorbic<br />

acid intake <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> status. It is generally<br />

believed that c<strong>on</strong>stant ingesti<strong>on</strong> of ascorbic<br />

acid will have less effect <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong><br />

than would be predicted from studies <strong>on</strong><br />

meals. For example, Cook et al. (1984) gave<br />

2 g ascorbic acid per day with self-selected<br />

meals c<strong>on</strong>sumed by 17 adult volunteers for<br />

4 m<strong>on</strong>ths. Mean serum ferritin values were<br />

46 <strong>and</strong> 43 µg/L before <strong>and</strong> after the study,<br />

respectively. The study was c<strong>on</strong>tinued for an<br />

additi<strong>on</strong>al 20 m<strong>on</strong>ths in 4 ir<strong>on</strong>-deficient <strong>and</strong><br />

5 ir<strong>on</strong>-replete subjects. There was a significant<br />

increase in serum ferritin <strong>on</strong>ly in the<br />

ir<strong>on</strong>-deficient subjects, from a mean of 6 µg/<br />

L initially to 35 µg/L after 2 years, although<br />

the size of the resp<strong>on</strong>se differed greatly<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g the subjects.

Ir<strong>on</strong>–ascerbic Acid <strong>and</strong> Ir<strong>on</strong>–calcium <str<strong>on</strong>g>Interacti<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> Their Relevance in Complementary Feeding<br />

In other l<strong>on</strong>ger-term trials, 300 mg<br />

ascorbic acid daily distributed am<strong>on</strong>g meals<br />

for 2 m<strong>on</strong>ths failed to increase serum ferritin<br />

(Mal<strong>on</strong>e et al. 1986). Similarly, Hunt<br />

et al. (1994) provided 1500 mg ascorbic acid<br />

daily with meals for 5 weeks <strong>and</strong> noted no<br />

increase in ferritin even though the subjects<br />

had initially low serum ferritin values (3.5–<br />

17.7 µg/L). Thus, although the lack of l<strong>on</strong>gterm<br />

improvement in some of these studies<br />

may have been partly due to the inclusi<strong>on</strong> of<br />

ir<strong>on</strong>-replete subjects whose efficiency of ir<strong>on</strong><br />

absorpti<strong>on</strong> was relatively low, this does not<br />

seem to be the whole explanati<strong>on</strong>. Another<br />

possibility is that the diets c<strong>on</strong>tained relatively<br />

low amounts of ir<strong>on</strong>-absorpti<strong>on</strong> inhibitors<br />

<strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tained meat so that the additi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

enhancing effect of ascorbic acid<br />

would have been relatively low. It was also<br />

dem<strong>on</strong>strated that ascorbic acid supplementati<strong>on</strong><br />

has less effect <strong>on</strong> ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong> when<br />

measured over 2 weeks than when measured<br />

after a single meal (Cook et al. 1991a). Additi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

research is needed <strong>on</strong> the l<strong>on</strong>gerterm<br />

benefits of habitually increasing the<br />

ascorbic acid intake of ir<strong>on</strong>-deficient individuals<br />

who c<strong>on</strong>sume meals that usually c<strong>on</strong>tain<br />

large amounts of inhibitors of ir<strong>on</strong> absorpti<strong>on</strong>.<br />