rapid assessment of the social impacts of - Philippines Development ...

rapid assessment of the social impacts of - Philippines Development ...

rapid assessment of the social impacts of - Philippines Development ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

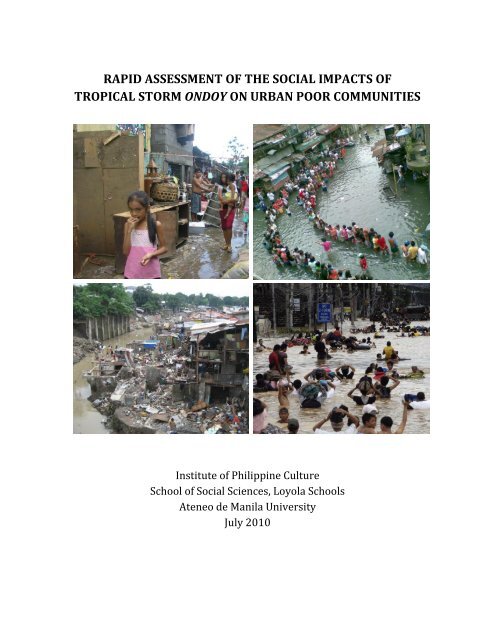

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF THE SOCIAL IMPACTS OF<br />

TROPICAL STORM ONDOY ON URBAN POOR COMMUNITIES<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Philippine Culture<br />

School <strong>of</strong> Social Sciences, Loyola Schools<br />

Ateneo de Manila University<br />

July 2010

Foreword<br />

Tropical storm Ondoy devastated communities across Metro Manila in late September,<br />

2009. Following <strong>the</strong> storm a Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) was prepared by <strong>the</strong><br />

Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Philippines</strong> in partnership with <strong>the</strong> World Bank, UN agencies, o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

international development partners and representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> private sector and civil<br />

society organizations.<br />

As part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> PDNA a <strong>rapid</strong> Social Impact Assessment (SIA) was conducted in seven urban<br />

poor communities in Metro Manila to document and analyze <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> storm. The<br />

main findings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>social</strong> impact <strong>assessment</strong> were immediately integrated in <strong>the</strong><br />

overall PDNA. (A separate <strong>assessment</strong> covering <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> typhoon Pepeng was<br />

conducted in rural areas.)<br />

The longer report presented here on <strong>the</strong> <strong>social</strong> <strong>impacts</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ondoy provides more in-depth<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>impacts</strong>, responses, and coping mechanisms used by urban poor<br />

communities as <strong>the</strong>y struggle to come to terms with <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> storm.<br />

The report also discusses <strong>the</strong> methodological approach used in <strong>the</strong> SIA, including an annex<br />

that provides details on <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> questions that were used during interviews with<br />

residents <strong>of</strong> urban poor communities, <strong>the</strong>ir local government representatives, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

stakeholders.<br />

The report stands as a testament to <strong>the</strong> resilience <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> women, men, and children who<br />

faced <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> a mighty storm and who continue <strong>the</strong>ir efforts to rebuild <strong>the</strong>ir lives and<br />

livelihoods. We can draw hope from <strong>the</strong>ir experience even as we reflect on <strong>the</strong> many<br />

remaining challenges that require urgent attention.<br />

Mary Racelis<br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Philippine Culture<br />

Ateneo de Manila University<br />

ii

Acknowledgments<br />

The research team at <strong>the</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Philippine Culture (IPC) that prepared this <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>social</strong><br />

impact <strong>assessment</strong> (SIA) was led by Angela Desiree Aguirre (Project Director) and<br />

comprised Henrietta Aguirre, Ophalle Alzona, Maria Cynthia Barriga, Dioscora Bolong, Kris<br />

Paulette Caoyonan, Ma. Lina Diona, Patrick Dominador Falguera, S.J., Marianne Angela<br />

Hermida, Bernadette Guillermo, Karen Anne Liao, Angelito Nunag, Gladys Ann Rabacal,<br />

Anchristine Ulep, Jon Michael Villaseñor and Ana Teresa Yuson. Mary Racelis and Czarina<br />

Saloma-Akpedonu participated in <strong>the</strong> study as consultants.<br />

The IPC team would like to thank all <strong>the</strong> NGO-PO partners who participated in and<br />

facilitated implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study, and especially all <strong>the</strong> community members who<br />

volunteered <strong>the</strong>ir time to share <strong>the</strong>ir experiences.<br />

The team would also like to acknowledge staff from <strong>the</strong> World Bank’s <strong>social</strong> development<br />

team in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Philippines</strong> who provided technical assistance to <strong>the</strong> research team, including<br />

Andrew Parker, Patricia Fernandes, and Maria Loreto Padua.<br />

Funding for <strong>the</strong> SIA was provided through <strong>the</strong> Global Fund for Disaster Risk Reduction as<br />

part <strong>of</strong> its support for Typhoons Ondoy and Pepeng: Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (2009),<br />

which is available for download at pdf.ph.<br />

The views and opinions expressed in <strong>the</strong> report are solely those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research team from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Institute <strong>of</strong> Philippine Culture.<br />

Front cover – photo credits (clockwise from top left): Evangeline Pe, John Paul del Rosario, Nonie<br />

Reyes, John Paul del Rosario<br />

iii

Contents<br />

Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................... ii<br />

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii<br />

Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................................. vii<br />

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 1<br />

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 3<br />

Objectives .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3<br />

Site Selection .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3<br />

Methodology .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4<br />

Data Collection Methods ....................................................................................................................................................... 4<br />

Data Collection Activities ...................................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Initial site visits ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>iling <strong>of</strong> FGD participants .............................................................................................................................................. 6<br />

Focus group discussions ....................................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Key informant interviews..................................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Feedback sessions with <strong>the</strong> community and NGO-PO research partners....................................................... 6<br />

Limitations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study ........................................................................................................................................................ 8<br />

The Research Team.................................................................................................................................................. 8<br />

The IPC Researchers ............................................................................................................................................................... 8<br />

NGO-PO Research Partners ................................................................................................................................................. 8<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Research Sites ...................................................................................................................... 8<br />

Riverine Communities ........................................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

Lakeside Communities......................................................................................................................................................... 13<br />

Control Community ............................................................................................................................................................... 14<br />

Changes in Livelihoods and Employment ................................................................................................... 15<br />

Lost livelihood and <strong>the</strong> self-employed .......................................................................................................................... 16<br />

Loss or suspension <strong>of</strong> jobs and <strong>the</strong> employed ........................................................................................................... 17<br />

New livelihood opportunities ........................................................................................................................................... 17<br />

Shifts in livelihood ................................................................................................................................................................. 18<br />

iv

Increased debt burden ......................................................................................................................................................... 18<br />

Changes in everyday life ..................................................................................................................................................... 19<br />

Responses to Changed Livelihood Outcomes............................................................................................. 19<br />

Relief assistance ..................................................................................................................................................................... 19<br />

Participating in cash for work schemes ....................................................................................................................... 20<br />

Receiving support from family and <strong>the</strong> workplace ................................................................................................. 20<br />

Borrowing ................................................................................................................................................................................. 20<br />

Saving more, consuming less ............................................................................................................................................ 21<br />

Keeping <strong>the</strong> faith .................................................................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Children and youth at work ............................................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Disruptions to Social Life and Mobilization <strong>of</strong> Social Relations ......................................................... 21<br />

Displacement and disruptions in <strong>social</strong> life ............................................................................................................... 21<br />

Gender and intergenerational relations ...................................................................................................................... 22<br />

Social support networks ..................................................................................................................................................... 24<br />

Cracks in <strong>the</strong> collective conscience ................................................................................................................................ 25<br />

Local Governance and Institutional Responses to <strong>the</strong> Calamity ........................................................ 25<br />

Rescue and Evacuation ........................................................................................................................................................ 25<br />

Relief Management ................................................................................................................................................................ 26<br />

Recovery .................................................................................................................................................................................... 33<br />

Resettlement ............................................................................................................................................................................ 34<br />

Conclusions and Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 34<br />

Insights and Recommendations from Communities .............................................................................................. 36<br />

Summary Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................ 39<br />

References ................................................................................................................................................................ 41<br />

Notes ........................................................................................................................................................................... 42<br />

Annex A - NGO-PO Research Partners .......................................................................................................... 44<br />

Annex B – Research Tools .................................................................................................................................. 45<br />

v

List <strong>of</strong> Tables, Boxes and Figures<br />

Tables<br />

Table 1 Research sites, by location and organizational arrangement ................................................................... 4<br />

Table 2: Fieldwork schedule..................................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Table 3: Selected features <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research sites a ........................................................................................................... 10<br />

Table 4: Changes observed in <strong>the</strong> employment/livelihood activities in KV1 ................................................... 17<br />

Table 5: Key lending features ................................................................................................................................................. 18<br />

Table 6: Forms <strong>of</strong> assistance provided by community groups and individuals .............................................. 27<br />

Table 7: Forms <strong>of</strong> government assistance ........................................................................................................................ 30<br />

Table 8: Community recommendations for disaster preparedness and prevention .................................... 36<br />

Table 9: Community recommendations to improve relief operations <strong>of</strong> various groups........................... 39<br />

Boxes<br />

Box 1 Local History <strong>of</strong> Flooding .............................................................................................................................................. 8<br />

Box 2: Daily living .......................................................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

Box 3: Vending as a livelihood ............................................................................................................................................... 16<br />

Box 4: Trauma from Ondoy ..................................................................................................................................................... 17<br />

Box 5: Selling purified water .................................................................................................................................................. 18<br />

Box 6: Taking out loans ............................................................................................................................................................. 18<br />

Box 7: Relief Assistance in Camacho Phase II ................................................................................................................. 20<br />

Box 8: Relief Assistance in Kasiglahan Village 1 ............................................................................................................ 20<br />

Box 9: High prices <strong>of</strong> food ........................................................................................................................................................ 21<br />

Box 10: Daily living at <strong>the</strong> evacuation center .................................................................................................................. 22<br />

Box 11: Studying at <strong>the</strong> evacuation center ....................................................................................................................... 22<br />

Box 12: Women to <strong>the</strong> rescue ................................................................................................................................................ 23<br />

Box 13: Men doing domestic tasks ...................................................................................................................................... 24<br />

Box 15: Neighbors embrace each o<strong>the</strong>r............................................................................................................................. 24<br />

Box 15: Offering dry clo<strong>the</strong>s ................................................................................................................................................... 24<br />

Box 16: Seeking shelter during Ondoy ............................................................................................................................... 26<br />

Box 17: The Filipino as aid recipient .................................................................................................................................. 29<br />

Box 18: Arlene’s request for help ......................................................................................................................................... 38<br />

Figures<br />

Figure 1: Location <strong>of</strong> Research Sites ..................................................................................................................................... 4<br />

vi

Acronyms<br />

ADMU Ateneo de Manila University<br />

BHW Barangay Health Worker<br />

CARD Center for Agriculture and <strong>Development</strong><br />

CFC Couples for Christ<br />

CFC-GK Couples for Christ-Gawad Kalinga<br />

CIDSS Comprehensive and Integrated Delivery <strong>of</strong> Social Services<br />

CO Community organization<br />

COM Community Organizers Multiversity<br />

CP2HOA Camacho Phase II Homeowners’ Association<br />

CSO Civil Society Organization<br />

CWL Catholic Women’s League<br />

DILG Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Interior and Local Government<br />

DLSU De La Salle University<br />

DOH Department <strong>of</strong> Health<br />

DSWD Department <strong>of</strong> Social Welfare and <strong>Development</strong><br />

FGD Focus Group Discussion<br />

GK Gawad Kalinga<br />

GO Government Organization<br />

GRDC Goldenville Realty and <strong>Development</strong> Corporation<br />

HH Household<br />

HOA Homeowners’ Association<br />

HUDCC Housing and Urban <strong>Development</strong> Coordinating Council<br />

HVG Highly Vulnerable Group<br />

ICSI Institute on Church and Social Issues<br />

INC Iglesia ni Cristo<br />

IPC Institute <strong>of</strong> Philippine Culture<br />

KAAKAP Kapatiran Asosasyon sa Kapiligan<br />

KAHA Kapiligan Homeowners Association<br />

KII key Informant Interview<br />

KMBI Kabalikat para sa Maunlad na Buhay, Inc.<br />

KMNA Kasiglahan Muslim Neighbors Association<br />

KUMRA Kasiglahan United Muslim Resettlement Association<br />

KV1 Kasiglahan Village 1<br />

LCE Local Chief Executive<br />

LGU Local Government Unit<br />

MFI Micr<strong>of</strong>inance Institution<br />

MCNA Marikina Couples Neighborhood Association<br />

MLA Montalban Ladies Association<br />

MLCE Municipal local Chief Executive<br />

MMDA Metro Manila <strong>Development</strong> Authority<br />

MMHA Mejia-Molave Homeowners Association<br />

MRB Medium-Rise Building<br />

MSO Marikina Settlements Office<br />

NGA National Government Agency<br />

NGO Non Governmental Organization<br />

NHA National Housing Authority<br />

NNA Nawasa Neighborhood Association<br />

NOKRAI North Kapiligan Riverside Association Inc.<br />

Pag-IBIG Pagtutulungan sa kinabukasan: Ikaw, Bangko, Industriya at Gobyerno<br />

vii

PDNA Post-Disaster Needs Assessment<br />

PHA Pasig Health Aides<br />

PhilSSA Partnership <strong>of</strong> Philippine Support Service Agencies, Inc.<br />

PO People’s Organization<br />

PSG Pasig Security Guards<br />

PTA Parents-Teachers Association<br />

PUJ Public Utility Jeepney<br />

RASYC Riverside Association <strong>of</strong> Senior and Youth Corporation<br />

RIBANA Riverbanks Neighborhood Association<br />

RTU Rizal Technological University<br />

SAMAKAPA Samahang Maralita at Kapit-bisig sa Floodway, Maybunga, Pasig<br />

SIA Social impact <strong>assessment</strong><br />

SK Sangguniang Kabataan<br />

SNHA Samahang Nagkakaisang-Hanay Association<br />

SNKF Samahan ng Kababaihan sa Floodway, Maybunga<br />

SV 4 Southville 4<br />

TESDA Technical Education and Skills <strong>Development</strong> Authority<br />

TSPI Tulay sa Pag-unlad Inc.<br />

TUPAD Tulong sa Panghanap-buhay sa Ating Disadvantaged Workers<br />

UERMMMC University <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> East Ramon Magsaysay Memorial Medical Center<br />

ULAP Ugnayang Lakas ng mga Apektadong Pamilya<br />

UN United Nations<br />

UP University <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Philippines</strong><br />

WB World Bank<br />

WFM West Bank, Floodway, Maybunga<br />

WFMNAI West Bank Floodway Maybunga Neighborhood Association, Inc.<br />

YFC Youth for Christ<br />

viii

Executive Summary<br />

Immediately after tropical storm Ondoy flooded large sections <strong>of</strong> Metro Manila and nearby<br />

areas in September 2009, <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Philippines</strong> carried out a Post-Disaster Needs<br />

Assessment (PDNA) with <strong>the</strong> support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery<br />

(GFDRR), World Bank, UN agencies, numerous civil society organizations and academic<br />

institutions. The PDNA included a <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> <strong>of</strong> seven poor urban settlements in Metro<br />

Manila, Laguna, and Rizal, which focused on <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> Ondoy on <strong>the</strong> urban poor’s livelihoods<br />

and employment, <strong>social</strong> relations, and on local governance. The study chose four riverine and<br />

two lakeside communities that exemplified <strong>the</strong> situation in urban poor settlements affected by<br />

Ondoy. Of <strong>the</strong> six, three were relocation sites (national government or local government<br />

supported) while <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r three were informal communities. In addition, a control site, not<br />

directly affected by Ondoy (Marikina Heights), served as a reference point to enable <strong>the</strong> team to<br />

better understand what <strong>social</strong> changes observed were more directly linked to <strong>the</strong> disaster. The<br />

selection criteria tested <strong>the</strong> premise that among urban poor communities equally affected by<br />

<strong>the</strong> storm, those having closer ties with government were more likely to have access to<br />

resources to address <strong>the</strong>ir immediate welfare needs and advocate for <strong>the</strong>ir long-term interests.<br />

The research employed qualitative research methods, primarily focus group discussions with<br />

diverse groups <strong>of</strong> residents and key informant interviews with community leaders and highly<br />

vulnerable individuals (including <strong>the</strong> elderly and <strong>the</strong> sick). These were supplemented by <strong>the</strong><br />

collection <strong>of</strong> secondary data, participant observation, and community walkthroughs. The initial<br />

findings were validated through feedback sessions with <strong>the</strong> residents and NGO-PO research<br />

partners.<br />

A diverse mix <strong>of</strong> income-generating activities was observed in <strong>the</strong> research sites. Small<br />

businesses and home-based livelihoods, particularly in <strong>the</strong> two lakeside communities (e.g.,<br />

shoemaking, vegetable farming, fishing) suffered <strong>the</strong> most significant losses as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

Ondoy. Salaried workers, particularly those who were able to keep <strong>the</strong>ir jobs after Ondoy, were<br />

<strong>the</strong> least affected as <strong>the</strong>y are assured regular wages. The aftermath <strong>of</strong> Ondoy saw increased<br />

employment opportunities for men in construction and automotive repair, as demand increased<br />

associated with immediate recovery and reconstruction efforts.<br />

Ondoy not only brought economic disruption but also changes in residents’ quality <strong>of</strong> life.<br />

Purchasing power was reduced. This resulted in limited food availability at <strong>the</strong> household level<br />

and in <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> adequate nutrition. Some households coped with help from <strong>the</strong>ir immediate<br />

family and from relatives living in <strong>the</strong> provinces or abroad. Some children and youth engaged in<br />

pangangalakal (“buy and sell” <strong>of</strong> junk goods) or in scavenging for scrap materials. This was<br />

described as a means <strong>of</strong> helping <strong>the</strong>ir households to cope with reduced income. Some, usually<br />

women, resorted to borrowing fur<strong>the</strong>r from both formal and informal lending sources.<br />

However, instead <strong>of</strong> financing productive activities, loans were diverted to cover basic<br />

household needs, such as food, medicine, water, electricity, and school allowances.<br />

The nature <strong>of</strong> livelihood challenges in <strong>the</strong> affected communities did not differ significantly from<br />

<strong>the</strong> one prevailing in <strong>the</strong> control site. This trend reflects <strong>the</strong> precarious nature <strong>of</strong> livelihoods in<br />

poor urban areas. Irrespective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> Ondoy, poor communities face serious economic<br />

difficulties. The disaster was found to exacerbate <strong>the</strong>se significantly. The coping strategies<br />

observed, however, are those usually resorted to by <strong>the</strong> urban poor. These included reducing<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> basic items including food, taking on additional work where available, and<br />

1

having more members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> household (including children) working, as well as incurring<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r debt and relying on financial support from immediate family members.<br />

Ondoy caught <strong>the</strong> communities in <strong>the</strong> sites visited unprepared. During <strong>the</strong> storm, residents<br />

relied on <strong>the</strong>ir own families and relatives, friends, and neighbors for help with rescue. Residents<br />

whose houses were flooded sought temporary shelter at evacuation centers <strong>of</strong>ten ill equipped<br />

to handle large groups. Overcrowding, lack <strong>of</strong> electricity and water, locked washrooms, and<br />

inadequate food were some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> complaints reported. Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong>re were a number <strong>of</strong><br />

instances observed <strong>of</strong> community solidarity and collaborative behavior as a result <strong>of</strong> Ondoy. For<br />

example, youth (although unorganized) embraced new <strong>social</strong> responsibilities, helping to<br />

remove debris, collect garbage, and repack and distribute relief goods.<br />

Civil society mobilization and intra-community relationships were vital during <strong>the</strong> rescue<br />

phase, and <strong>the</strong> immediate aftermath <strong>of</strong> Ondoy. Participants in <strong>the</strong> discussions reported that<br />

Barangay <strong>of</strong>ficials were <strong>of</strong>ten unable to respond to community needs largely because <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

attending to <strong>the</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own families. In addition, <strong>of</strong>ficials reportedly did not receive<br />

adequate training in disaster response. Barangays and to some extent <strong>the</strong> national authorities<br />

were, however, active in <strong>the</strong> relief and early recovery phase that followed. In <strong>the</strong> communities<br />

visited, <strong>the</strong>re appeared to be no plans to provide longer-term assistance to affected families.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> residents participating in <strong>the</strong> discussions indicated no interest in leaving <strong>the</strong>ir present<br />

locations as <strong>the</strong>y did not want to be displaced from <strong>the</strong>ir sources <strong>of</strong> livelihood and employment<br />

and <strong>the</strong> <strong>social</strong> networks <strong>the</strong>y established over <strong>the</strong> course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir stay in <strong>the</strong> community. A<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> organizational factors (e.g., existence <strong>of</strong> well-organized groups within <strong>the</strong><br />

community) and geographical location (e.g., accessibility <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> community to organizations<br />

providing assistance) enabled riverine communities to cope better with <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> Ondoy<br />

than those in lakeside areas.<br />

Residents attributed <strong>the</strong> flooding caused by Ondoy to a variety <strong>of</strong> factors, including <strong>the</strong> release<br />

<strong>of</strong> water from dams, poor garbage management, inadequate drainage systems, poor<br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> zoning and building laws, and <strong>the</strong> continued cutting <strong>of</strong> trees and reclaiming<br />

<strong>of</strong> land to make way for subdivisions. Research participants across sites <strong>of</strong>fered similar<br />

proposals to prepare for and mitigate <strong>the</strong> possible impact <strong>of</strong> similar storms in <strong>the</strong> future. Most<br />

recommendations focused on introducing and/or implementing policies and programs on land<br />

use and housing, protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> environment, and disaster prevention, rescue, relief and<br />

rehabilitation, and improving <strong>the</strong> capacities <strong>of</strong> local communities to respond to disasters.<br />

2

Introduction<br />

Immediately after Ondoy flooded large sections <strong>of</strong> Metro Manila and nearby areas in September<br />

2009, a Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) was carried out in partnership with<br />

government institutions, <strong>the</strong> Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), <strong>the</strong><br />

World Bank, <strong>the</strong> United Nations, civil society and academic institutions. In this context, <strong>the</strong><br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Philippine Culture (IPC) <strong>of</strong> Ateneo de Manila University was asked to design and<br />

implement a <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> <strong>of</strong> seven urban poor settlements in Metro Manila, Laguna, and<br />

Rizal. The study aimed to collect qualitative data on <strong>the</strong> <strong>social</strong> dimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tropical<br />

storm’s impact on <strong>the</strong> urban poor that would complement <strong>the</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> <strong>of</strong> economic damages<br />

and losses.<br />

This report, presenting <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong>, consists <strong>of</strong> five sections. The first<br />

outlines <strong>the</strong> objectives and methodology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study. The second section presents <strong>the</strong><br />

situational pr<strong>of</strong>iles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research sites which are categorized into formal and informal<br />

settlements. The third section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> report examines <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> tropical storm Ondoy on <strong>the</strong><br />

livelihoods and employment, <strong>social</strong> relations, and local governance structures in urban poor<br />

communities. Recommendations and proposals from <strong>the</strong> communities for disaster<br />

preparedness and relief management comprise <strong>the</strong> fourth section. The report <strong>the</strong>n concludes<br />

with <strong>the</strong> summary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study’s main findings and a presentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> researchers’ insights.<br />

Objectives<br />

The <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> aimed to determine <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> Ondoy on <strong>the</strong> everyday lives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

urban poor in Metro Manila and surrounding areas. It focused on livelihoods and employment,<br />

<strong>social</strong> relations, and local governance. Eliciting and listening to <strong>the</strong> views and feelings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

urban poor, as well as <strong>the</strong>ir recommendations on how best to address <strong>the</strong>ir present situation<br />

were crucial to achieving this objective. On <strong>the</strong> one hand, <strong>the</strong> data pertained to losses incurred<br />

by communities. This included <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> houses and belongings, loss <strong>of</strong> employment,<br />

livelihood, and o<strong>the</strong>r assets, deaths, disabilities, illnesses, trauma, and disruption <strong>of</strong> <strong>social</strong><br />

bonds. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong> appraisal assessed how existing <strong>social</strong> structures worked during<br />

<strong>the</strong> disaster and how resilient communities were. The ensuing resolve <strong>of</strong> various sectors to be<br />

better prepared for <strong>the</strong> next calamity <strong>of</strong>fered a narrow window <strong>of</strong> opportunity to set in motion<br />

processes toward recovery, rehabilitation, and development that recognize and consider <strong>the</strong><br />

voices <strong>of</strong> urban poor communities.<br />

Site Selection<br />

The World Bank and <strong>the</strong> IPC collaborated with <strong>the</strong> Community Organizers Multiversity (COM),<br />

<strong>the</strong> Partnership <strong>of</strong> Philippine Support Service Agencies, Inc. (PhilSSA) and <strong>the</strong> Institute on<br />

Church and Social Issues (ICSI) to identify <strong>the</strong> study sites. The following were <strong>the</strong> site selection<br />

criteria followed: (1) riverbank settlements; (2) Laguna Lake communities; (3) formal<br />

(government-organized settlement/relocation communities) and informal settlements in <strong>the</strong><br />

locations mentioned above; and (4) a community that was not directly affected by Ondoy as <strong>the</strong><br />

control site (Table 1).<br />

The selection criteria recognized that among urban poor communities, those directly located<br />

along <strong>the</strong> shores <strong>of</strong> Laguna Lake and along <strong>the</strong> main rivers <strong>of</strong> Metro Manila and Rizal were <strong>the</strong><br />

most vulnerable to flooding. The selection criteria also tested <strong>the</strong> hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that among urban<br />

poor communities equally affected by <strong>the</strong> storm, those having close ties with local governments<br />

or civil society organizations were more likely to have access to resources to address <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

3

immediate welfare needs and to be better able to advocate for <strong>the</strong>ir long-term interests. The<br />

control site served as a reference point to help identify <strong>the</strong> <strong>social</strong> changes in <strong>the</strong> six affected<br />

communities that might directly be associated with Ondoy.<br />

Location<br />

Table 1: Research sites, by location and organizational arrangement<br />

Riverine Kasiglahan Village 1 in Barangay San<br />

Jose, Montalban a<br />

Organizational arrangements<br />

Formal Informal<br />

Gawad Kalinga Camacho Phase II in<br />

Barangay Nangka, Marikina City b<br />

Lakeside Southville 4 in Barangay Caingin and<br />

Barangay Pooc, City <strong>of</strong> Sta. Rosa,<br />

Laguna a<br />

Non-flooded area Barangay Marikina Heights, Marikina (Control Group) c<br />

4<br />

Barangay Doña Imelda, Quezon City<br />

Barangay Maybunga, Pasig<br />

Barangay Malaban, Biñan, Laguna<br />

a National government resettlement site, b Local government and private sector initiative resettlement site.<br />

c A mix <strong>of</strong> formal and informal settlers.<br />

The study chose four riverine and two lakeside communities that exemplified <strong>the</strong> situation in<br />

urban poor settlements affected by Ondoy (Figure 1). Of <strong>the</strong> six, three were relocation sites<br />

(supported by national government or local government) while <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r three were informal<br />

communities. The first group, referred to in this study as formal communities, consisted <strong>of</strong><br />

Kasiglahan Village 1 or KV1 (Barangay San Jose, Rodriguez, Rizal), Southville 4 or SV4<br />

(Barangay Pooc and Barangay Caingin, Sta. Rosa City, Laguna), and Gawad Kalinga (GK) 1<br />

Camacho Phase II (Barangay Nangka, Marikina City). Barangay Doña Imelda in Quezon City,<br />

Barangay Maybunga in Pasig City (West Bank, Floodway, Manggahan or WFM), and Barangay<br />

Malaban in Biñan, Laguna comprised <strong>the</strong> informal settlements. The control community,<br />

Barangay Marikina Heights in Marikina City, is a mix <strong>of</strong> formal and informal settlements<br />

unaffected by Ondoy.<br />

Methodology<br />

The research team designed a qualitative study to ascertain <strong>the</strong> urban poor’s understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir experiences <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disaster. The study recognizes that <strong>the</strong> responses and <strong>the</strong> consequences<br />

<strong>of</strong> disaster on vulnerable individuals and groups will vary according to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>social</strong> locations and<br />

positions. It created an opportunity for <strong>the</strong>se vulnerable groups to voice <strong>the</strong>ir own perspectives<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> event. Perceived by <strong>the</strong> community as timely and relevant, <strong>the</strong> study drew much interest<br />

and cooperation from <strong>the</strong> residents who were still trying to make sense <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir situation.<br />

Data Collection Methods<br />

The research employed qualitative research methods, primarily Focus Group Discussions (FGD)<br />

with different groups from <strong>the</strong> community and key informant interviews (KII) with community<br />

leaders and highly vulnerable individuals (including <strong>the</strong> elderly and <strong>the</strong> sick). Data from <strong>the</strong><br />

FGDs and KIIs were supplemented by <strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> secondary data, observation, and<br />

community walkthroughs. The initial findings were validated during feedback sessions with <strong>the</strong><br />

residents and NGO-PO research partners (Annex A). Within <strong>the</strong> project’s limited preparation<br />

time, a set <strong>of</strong> research instruments consisting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> FGD guide, KII guide, community pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

checklist, and FGD participant pr<strong>of</strong>iling tool was developed. 2 The pre-test <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> FGD guide<br />

which was held in Barangay Payatas, Quezon City highlighted <strong>the</strong> need to prioritize topics

according to <strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong> FGD group. Key data sets that cut across topics could only be collected if<br />

permitted by time during <strong>the</strong> two-hour FGD session. Thus, <strong>the</strong> FGD with individuals from<br />

different occupational groups focused on collecting data on livelihoods and socioeconomic<br />

adaptations. Assuming <strong>the</strong>re was still enough time left, <strong>the</strong> researchers guided <strong>the</strong> FGD to a<br />

discussion on <strong>social</strong> support networks (for <strong>the</strong> topic on <strong>social</strong> relations and cohesion) and relief<br />

and recovery response from government, <strong>the</strong> community, and civil society (for <strong>the</strong> topic on<br />

local governance). With community leaders, <strong>the</strong> FGD focused on local governance, followed by<br />

questions on <strong>social</strong> support networks and life at <strong>the</strong> evacuation center, community<br />

participation, and <strong>social</strong> accountability (for <strong>the</strong> topic on <strong>social</strong> relations and cohesion) and<br />

coping strategies (for <strong>the</strong> topic on livelihoods and socioeconomic adaptations).<br />

Figure 1: Location <strong>of</strong> Research Sites<br />

5

Data Collection Activities<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> need to generate results for inclusion in <strong>the</strong> PDNA report issued in mid-November<br />

2009, <strong>the</strong> research team followed a very tight fieldwork schedule based on consultations with<br />

partner-PO leaders and barangay <strong>of</strong>ficials (Table 2). Data collection was limited to one week,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> researchers facilitating two FGD sessions in a day. In each site, four FGD sessions and<br />

at least three key informant interviews were conducted. A community feedback session marked<br />

<strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> data collection in each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> areas visited.<br />

Initial site visits<br />

Initial visits to <strong>the</strong> sites enabled <strong>the</strong> researchers and <strong>the</strong>ir PO partners to orient barangay<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials and PO leaders about <strong>the</strong> study, finalize <strong>the</strong> research schedule, conduct informal<br />

interviews with barangay and PO leaders, and ga<strong>the</strong>r secondary data (e.g., barangay pr<strong>of</strong>ile, PO<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile). Community walkthroughs which allowed <strong>the</strong> researchers to observe everyday life in<br />

<strong>the</strong> community and to take note <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> community’s physical conditions were also conducted<br />

during <strong>the</strong> initial phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>iling <strong>of</strong> FGD participants<br />

The selection <strong>of</strong> FGD participants was aided by <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> a pr<strong>of</strong>iling tool which provided <strong>the</strong><br />

researcher with basic information on potential participants, including name, age, sex, education,<br />

address, religion, number <strong>of</strong> children, source <strong>of</strong> family/household income, membership in any<br />

community or barangay association, position or designation in <strong>the</strong> community or barangay<br />

association. A primary consideration in making <strong>the</strong> final selection <strong>of</strong> participants was<br />

representation from male and female community members across age groups, occupations, and<br />

across all residential clusters (near and far from <strong>the</strong> community center). Care was also taken to<br />

make sure that persons with disabilities were represented.<br />

Focus group discussions<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> twenty-eight FGD sessions, or four in each site were held, with four different groups<br />

representing various livelihoods, women, youth, and community leaders. Discussions had an<br />

average <strong>of</strong> seven participants, with women greatly outnumbering men. Inviting male<br />

participants proved difficult given <strong>the</strong> timing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sessions.<br />

Key informant interviews<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> twenty-five face-to-face interviews were conducted with representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

barangay local government unit (LGU), community associations, and highly vulnerable groups<br />

(as determined by <strong>the</strong> community) to provide depth to <strong>the</strong> FGD data. Among those who agreed<br />

to be interviewed were barangay captains and kagawad (council members), and PO leaders.<br />

Feedback sessions with <strong>the</strong> community and NGO-PO research partners<br />

To validate <strong>the</strong> initial conclusions, <strong>the</strong> researchers facilitated on-site feedback sessions before<br />

leaving <strong>the</strong> communities. Attendance ranged from 34 (Doña Imelda) to 310 (Malaban)<br />

participants. Sessions in non-Metro Manila sites registered a relatively higher attendance<br />

(average <strong>of</strong> 237) than those Metro Manila sites (average <strong>of</strong> 49). The IPC also shared <strong>the</strong> initial<br />

findings with its major research partner, COM, a month after <strong>the</strong>ir first meeting and shortly<br />

before <strong>the</strong> submission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> final report. The meeting was attended by a CO trainer, two<br />

community organizers, and thirteen PO leaders. The group confirmed <strong>the</strong> communities’<br />

observations and recommendations and provided additional information.<br />

6

Research<br />

site<br />

Government relocation site<br />

Camacho<br />

Phase II,<br />

Nangka,<br />

Marikina<br />

City<br />

KV1, San<br />

Jose,<br />

Rodriguez<br />

Caingin,<br />

Santa Rosa<br />

Informal settlement<br />

Maybunga,<br />

Pasig City<br />

Doña<br />

Imelda,<br />

Quezon City<br />

Malaban,<br />

Biñan<br />

Oct 29 to Nov 4 Nov 5<br />

Courtesy calls to<br />

municipal/city<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials, initial<br />

interviews with<br />

barangay and<br />

community leaders,<br />

selection/invitation/<br />

confirmation <strong>of</strong> FGD<br />

participants,<br />

collection <strong>of</strong><br />

secondary data,<br />

research logistics,<br />

some KIIs (BC in<br />

Caingin; community<br />

leader and HVI in<br />

Camacho Phase II)<br />

Courtesy calls to<br />

municipal/city<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials, initial<br />

interviews with<br />

barangay and<br />

community leaders,<br />

selection/invitation/<br />

confirmation <strong>of</strong> FGD<br />

participants,<br />

collection <strong>of</strong><br />

secondary data,<br />

research logistics,<br />

some KIIs (BC in<br />

Maybunga)<br />

Mix <strong>of</strong> formal and informal settlers<br />

Marikina<br />

Heights,<br />

Marikina<br />

City<br />

Courtesy calls to<br />

municipal/city<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials, initial<br />

interviews with<br />

barangay and<br />

community leaders,<br />

selection/invitation/<br />

confirmation <strong>of</strong> FGD<br />

participants,<br />

collection <strong>of</strong><br />

secondary data,<br />

research logistics<br />

Table 2: Fieldwork schedule<br />

7<br />

Nov 6<br />

KII BC FGD (Livelihoods,<br />

Women)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>iling and<br />

invitation <strong>of</strong><br />

FGD<br />

participants<br />

FGD (Leaders,<br />

Livelihoods,)<br />

Women<br />

FGD (Leaders,<br />

Livelihoods)<br />

KII (PO, HVG)<br />

FGD (Women,<br />

Youth)<br />

FGD (Women,<br />

Youth)<br />

FGD (Leaders,<br />

Women)<br />

FGD (Livelihoods<br />

KII (HVG, BC)<br />

Nov 7<br />

FGD<br />

(Leaders,<br />

Youth)<br />

FGD<br />

(Women,<br />

Youth)<br />

KII (HVG,PO, CO) FGD<br />

(Youth)<br />

FGD (Women,<br />

Youth)<br />

KII (HVG, Barangay<br />

kagawad council<br />

members)<br />

FGD (Livelihood,<br />

Leaders)<br />

FGD (Livelihood,<br />

Leaders)<br />

KII (HVG,BC)<br />

FGD (Livelihoods)<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

KII (HGV,<br />

PO, BC)<br />

KII (PO,<br />

BC)<br />

FGD<br />

(Youth)<br />

KII (PO)<br />

Nov 8<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

KII (PO)<br />

FGD<br />

(Leaders)<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

KII (HVG)<br />

Community<br />

feedback<br />

FGD - focus group discussion; KII - key informant interview; HVG - highly vulnerable group (individual);<br />

BC - barangay captain; PO - people’s organization; CO - community organization; GO - government; KV1 -<br />

Kasiglahan Village 1.

Limitations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> time limitations and its nature as a qualitative study, <strong>the</strong> <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> does not<br />

provide estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affected population in terms <strong>of</strong> age, sex, or geographic cluster/area. It<br />

is also unable provide data on <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> households or families temporarily or<br />

permanently displaced, staying in o<strong>the</strong>r locations, or still in flooded areas, as no such data were<br />

collected or made available by <strong>the</strong> relevant organizations (e.g., barangay LGU, NGOs).<br />

The Research Team<br />

The IPC Researchers<br />

The research team was composed <strong>of</strong> seven field teams, each with a researcher and a<br />

documenter, to cover <strong>the</strong> seven study sites. The researchers served as key informant<br />

interviewers and FGD facilitators. They also analyzed <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> FGDs, key informant<br />

interviews, and observation notes, and prepared <strong>the</strong> site reports. The documenters prepared<br />

<strong>the</strong> notes and <strong>the</strong> full transcript <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> FGDs. 3<br />

NGO-PO Research Partners<br />

An important element <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> was <strong>the</strong> IPC’s collaboration with NGO and PO<br />

partners which provided <strong>the</strong> necessary links and facilitated <strong>the</strong> activities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research teams<br />

in <strong>the</strong> communities. In five <strong>of</strong> seven sites, COM 2<br />

provided assistance to <strong>the</strong> research team. An initial<br />

Box 1: Local History <strong>of</strong> Flooding<br />

Barangay Caingin, Barangay Pooc<br />

According to people from Caingin and Pooc, <strong>the</strong><br />

location <strong>of</strong> Southville gets flooded almost every<br />

six years during <strong>the</strong> months <strong>of</strong> September to<br />

November. The first flooding <strong>the</strong>y could<br />

remember was in 1972, with Typhoon Dading.<br />

The flood was chest-high near <strong>the</strong> lake and<br />

head-high in <strong>the</strong> rice field, where Southville 4 is<br />

now located. Floodwaters remained for two<br />

months and people used boats to move around.<br />

Succeeding floods have occurred every decade<br />

since <strong>the</strong> 1970s. At present, flooding occurs not<br />

only because <strong>of</strong> typhoons but also due to<br />

monsoon rains.<br />

Barangay San Jose, Montalban<br />

In 1929, Wawa Dam broke and water swelled in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Marikina River, leaving San Jose<br />

depopulated. Flooding occurred again in 1934<br />

and 2004. In 1934, residents transferred to<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r areas. Despite <strong>the</strong>se previous<br />

experiences, community leaders and residents<br />

did not take precaution. Unprepared, more than<br />

two thousand families in KVI were affected<br />

during Ondoy’s onslaught.<br />

meeting which was attended by a CO trainer, three<br />

COM community organizers, and twelve PO leaders<br />

representing <strong>the</strong> study sites allowed <strong>the</strong> partners<br />

to discuss <strong>the</strong> research design, plan initial site<br />

visits, and agree on a schedule for data collection. 3<br />

During data ga<strong>the</strong>ring, <strong>the</strong> researchers received<br />

support from Homeowners’ Association (HOA)<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials, mostly women, who guided <strong>the</strong>m during<br />

walkthroughs, helped identify FGD participants,<br />

and served as respondents <strong>the</strong>mselves. The NGO-<br />

PO research partners, in addition to providing field<br />

support, commented on <strong>the</strong> draft report at a<br />

meeting convened by <strong>the</strong> IPC on 28 November<br />

2009. Findings were validated, analyses refined,<br />

and recommendations streng<strong>the</strong>ned through this<br />

discussion.<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Research Sites<br />

The pr<strong>of</strong>iles below selected physical, demographic,<br />

economic and organizational features <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

research sites that would help explain why <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are similarities and differences in how Ondoy<br />

affected urban poor communities (Table 3). Of <strong>the</strong><br />

six affected communities, four have a history <strong>of</strong><br />

flooding (Box 1).<br />

8

Riverine Communities<br />

West Bank, Floodway, Barangay Maybunga, Pasig City. Barangay Maybunga is home to<br />

many informal settlements along <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Manggahan Floodway. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se is West<br />

Bank, Floodway, Manggahan (WFM), which has an estimated population <strong>of</strong> 23,000 or around<br />

4,400 families. Some 2,011 families among <strong>the</strong>m were still in flooded locations when <strong>the</strong><br />

appraisal was conducted.<br />

Even prior to Ondoy, limited livelihood and income generating opportunities were key issues<br />

for <strong>the</strong> community. The men were employed mainly as wage workers in construction projects<br />

and manufacturing companies in <strong>the</strong> metropolis. Some were engaged in ambulant vending and<br />

driving public vehicles, such as tricycles and jeepneys. Whe<strong>the</strong>r formally employed or working<br />

from home, many women take on part-time employment at manufacturing firms, tending <strong>of</strong><br />

sari-sari (variety) stores, food vending, “buying and selling” schemes, dress and crafts making,<br />

and micro-lending. Although regarded as a secondary source <strong>of</strong> income, what <strong>the</strong>y earn from<br />

informal work augments <strong>the</strong> household income significantly.<br />

There is a prevailing divide among <strong>the</strong> various POs in WFM and <strong>the</strong> LGU in <strong>the</strong>ir position on <strong>the</strong><br />

issue security <strong>of</strong> tenure. The Samahang Maralita at Kapit-bisig sa Floodway, Maybunga, Pasig<br />

(SAMAKAPA), which is allied with <strong>the</strong> Pasig LGU, is amenable to relocation, specifically to a<br />

medium-rise building (MRB) complex in Maybunga. In contrast, <strong>the</strong> West Bank Floodway<br />

Maybunga Neighborhood Association, Inc. (WFMNAI), which is affiliated with COM, favors onsite<br />

development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir existing community.<br />

Barangay Doña Imelda, Quezon City. Part <strong>of</strong> District IV<br />

in Quezon City, Barangay Doña Imelda, occupies <strong>the</strong> land<br />

that stretches from Eulogio Rodriguez Avenue to Aurora<br />

Boulevard. It is a community <strong>of</strong> 17,647 residents whose<br />

informal housing structures are located on <strong>the</strong> riverbank<br />

along Rodriguez Avenue, an area vulnerable to flooding<br />

(Box 2). It contrasts sharply from <strong>the</strong> remaining parts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> district and <strong>the</strong>ir more affluent households.<br />

The informal settlers in <strong>the</strong> San Juan River vicinity are<br />

found in eight areas, namely, 29 Kapiligan, 42 Kapiligan,<br />

48 Kapiligan, 81 Kapiligan, 100 Kapiligan, 164 Kapiligan,<br />

186 Kapiligan, and Araneta Extension. In each area, a<br />

neighborhood association, also regarded as a homeowners’ association, is formed to fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

interests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> residents. They work in close collaboration with <strong>the</strong> barangay, city government,<br />

non-governmental and civil society organizations with regard livelihoods and issues such as<br />

security <strong>of</strong> tenure and eviction.<br />

Men in <strong>the</strong> community, whe<strong>the</strong>r adult or young, are generally employed as security guards,<br />

janitors, construction workers, masons, helpers, carpenters, drivers, bartenders, and sales staff.<br />

Women are generally engaged in small businesses <strong>of</strong>ten owning kiosks that are located ei<strong>the</strong>r in<br />

<strong>the</strong> first floor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir houses or along <strong>the</strong> sidewalks. Here, a variety <strong>of</strong> goods are sold from<br />

candies and toiletries to rice, cooked meals, barbecued meat, bibingka (rice cake) and<br />

bananacue (skewered bananas coated in caramelized sugar). O<strong>the</strong>r residents peddle pirated<br />

DVDs and cigarettes while some, especially younger women, work as salespeople in <strong>the</strong> nearby<br />

malls.<br />

9<br />

Box 2: Daily living<br />

Ang baha dito sa amin ay normal na.<br />

Karaniwan na ‘yung mababa sa tuhod<br />

ang tubig-baha. Tumaas lang ng konti<br />

ang tubig sa ilog dahil high tide, lubog na<br />

rin kaagad ang bahay namin. (Flooding<br />

has become normal here. Flood that is<br />

below <strong>the</strong> knee is a common sight. If <strong>the</strong><br />

water in <strong>the</strong> river rises because <strong>of</strong> high<br />

tides, our house immediately gets<br />

flooded, too.) – GINA, 40 YEARS OLD, LIVES UNDER<br />

THE BRIDGE

Barangay Sources <strong>of</strong> income<br />

Riverine Formal Settlements<br />

San Jose, Rodriguez,<br />

Rizal (Phases 1C and<br />

1D, KV1) b, c<br />

Nangka, Marikina<br />

City d (Gawad Kalinga<br />

[GK] Camacho Phase<br />

II)<br />

Riverine Informal settlements<br />

Doña Imelda, Quezon<br />

City<br />

(29 Kapiligan,<br />

42 Kapiligan,<br />

48 Kapiligan,<br />

81 Kapiligan,<br />

100 Kapiligan,<br />

164 Kapiligan,<br />

186 Kapiligan,<br />

Araneta Extension)<br />

Maybunga, Pasig City<br />

(West Bank,<br />

Floodway,<br />

Manggahan or WFM)<br />

Table 3: Selected features <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> research sites a<br />

Small-scale business<br />

Transport services<br />

(jeepneys, tricycles,<br />

pedicab)<br />

Aircon repair/<br />

maintenance, automotive<br />

Laundry services<br />

Work in beauty parlors<br />

Government/ LGU<br />

employment (utility<br />

workers, street cleaners,<br />

security guards)<br />

Private sector<br />

employment (factory<br />

workers, househelp)<br />

Sari-sari store<br />

Construction work<br />

Private sector<br />

employment (factory<br />

workers [shoemakers],<br />

gasoline station<br />

attendants)<br />

Selling food and non-food<br />

items, direct selling<br />

Scavenging, construction<br />

work (unskilled/semi<br />

skilled laborers, masons,<br />

carpenters), employment<br />

as domestic helpers,<br />

drivers,<br />

Bartending, LGU<br />

employment (street<br />

cleaners), private sector<br />

employment (salesladies,<br />

security guards, janitors)<br />

Ambulant vending, buy<br />

and sell<br />

Dress and crafts making<br />

Direct selling<br />

Micro lending<br />

Transport services<br />

(jeepneys and tricycles)<br />

Wage workers in<br />

construction projects<br />

Employees in<br />

manufacturing companies<br />

(full/part time)<br />

Community<br />

organizations<br />

Action Group HOAs<br />

(in all seven<br />

phases)<br />

KMNA<br />

Citizens Crime<br />

Watch<br />

PTA<br />

Parish Social<br />

Services<br />

Montalban Ladies<br />

Association<br />

NNA<br />

CP2CHOA<br />

HOA in each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

eight areas<br />

ULAP<br />

SAMAKAPA<br />

WFMNAI<br />

SNKF<br />

10<br />

Demographics<br />

280,786 residents<br />

287 families in GK<br />

Camacho Phase II<br />

17,647 residents<br />

Four to five<br />

families in a<br />

household<br />

Average <strong>of</strong> four<br />

persons per family<br />

16-20 occupants<br />

per shanty or<br />

dwelling unit<br />

23,000 or around<br />

4,400 families in<br />

WFM<br />

Functional<br />

disaster,<br />

emergency, or<br />

rescue programs<br />

or teams<br />

Barangay<br />

emergency/ rescue<br />

team<br />

Barangay disaster<br />

and management<br />

program and<br />

brigade<br />

No disaster<br />

response team in<br />

place, in <strong>the</strong><br />

recollection <strong>of</strong><br />

residents<br />

Fire and rescue<br />

response team

Barangay Sources <strong>of</strong> income<br />

Lakeside Formal Settlements<br />

Pooc and Caingin, City<br />

<strong>of</strong> Santa Rosa c (SV4)<br />

Lakeside Informal Settlements<br />

Malaban, Biñan,<br />

Laguna (Barangay<br />

Malaban)<br />

Control Site (Riverine)<br />

Marikina Heights,<br />

Marikina City c<br />

Laundry services<br />

Transport services<br />

(including trolley, a form<br />

<strong>of</strong> rail transport)<br />

Vending<br />

Pataya sa jueteng<br />

(informal lottery)<br />

Farming and fishing<br />

Collecting junk<br />

Employment in<br />

government and private<br />

sector (e.g., factory in<br />

Techno Park)<br />

Shoemaking<br />

Transport services<br />

(tricycles and jeepneys)<br />

Market labourers<br />

Vending<br />

Fishing (fish pen<br />

operators or small<br />

fishermen)<br />

Vegetable farming<br />

Food vending (barbecue,<br />

packed snacks; sari-sari<br />

stores<br />

Laundry services<br />

Regular or contractual<br />

employment (drivers,<br />

laboratory workers,<br />

construction workers)<br />

Community<br />

organizations<br />

HOA<br />

Angat Kababaihan<br />

Anak ng Sta. Rosa<br />

Sulong Kababaihan<br />

ng Malaban,<br />

Malayang Samahan<br />

Kagawad Biñan,<br />

Batang<br />

Manggagawa ng<br />

Malaban<br />

PTA<br />

CWL<br />

FOCC<br />

48 HOAs, including<br />

<strong>the</strong> following three<br />

HOAs in <strong>the</strong> focus<br />

areas:<br />

Mejia-Molave<br />

Homeowners’<br />

Association,<br />

Samahang<br />

Nagkakaisang-<br />

Hanay Association<br />

Marikina Couples<br />

Neighbourhood<br />

Association<br />

11<br />

Demographics<br />

4,686 families in<br />

SV4<br />

As <strong>of</strong> 2008:<br />

41, 404 residents<br />

8,281 households<br />

with an average <strong>of</strong><br />

5 to 6 members<br />

3-4 families<br />

comprising a<br />

household, in<br />

some cases<br />

440 to 450 people<br />

in 92 households<br />

in <strong>the</strong> three HOAs<br />

200 people in 40<br />

households<br />

200 people in 42<br />

households<br />

4 to 5 members in<br />

each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 10<br />

households<br />

Functional<br />

disaster,<br />

emergency, or<br />

rescue programs<br />

or teams<br />

No data<br />

No functional<br />

barangay<br />

emergency or<br />

rescue team in<br />

place, in <strong>the</strong><br />

recollection <strong>of</strong><br />

residents<br />

No data<br />

a Data largely obtained from <strong>the</strong> individual site reports.<br />

b Items in paren<strong>the</strong>ses refer to <strong>the</strong> focus area or site <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>rapid</strong> <strong>assessment</strong> in <strong>the</strong> barangay.<br />

c National government resettlement site.<br />

d Local government resettlement site.

A number <strong>of</strong> residents are also involved in direct selling <strong>of</strong> cosmetic products (e.g., Avon and<br />

Natasha products). Sewing rugs and dolls, or scavenging (for scrap material) within <strong>the</strong><br />

community and nearby areas are o<strong>the</strong>r common occupations. Inhabitants <strong>of</strong>ten turn to formal<br />

lending agencies such as ASA Foundation, Pag-asa, and Tulay sa Pag-unlad Inc. (TSPI); informal<br />

lenders, and relatives from <strong>the</strong> province and abroad for financial assistance in paying debts,<br />

meeting everyday household needs and financing small businesses (such as kiosks). It is very<br />

unlikely to see someone here who has not incurred any debt.<br />

Kasiglahan Village 1, San Jose, Rodríguez, Rizal. San Jose has a long history <strong>of</strong> flooding.<br />

Kasiglahan Village 1, popularly known as KV1, was unprepared for Ondoy with more than 2,000<br />

families affected by <strong>the</strong> tropical storm. KV1 is a resettlement project <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Philippine<br />

government’s National Housing Authority (NHA). It was initially intended for families affected<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Pasig River Rehabilitation Program. Over time, however, it also served as a resettlement<br />

site for <strong>the</strong> families displaced by fire, trash slides, 4 and government infrastructure projects. Only<br />

less than half (40 percent) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> households originally relocated remain in <strong>the</strong> area. A greater<br />

number have sold <strong>the</strong>ir property or property rights, rented out <strong>the</strong>ir units, or transferred to<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r places. Because <strong>of</strong> its distant location from <strong>the</strong> barangay center, a barangay extension<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice known as Barangay Annex B was set up in KV1. O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong>fices set up by <strong>the</strong> barangay in <strong>the</strong><br />

area are <strong>the</strong> emergency rescue team, waste management <strong>of</strong>fice, and an ecological solid<br />

management committee.<br />

Community-based organizations and local associations present in <strong>the</strong> area include <strong>the</strong> Action<br />

Group, 5 Homeowners’ Associations (HOAs) in its seven phases, Kasiglahan Muslim Neighbors<br />

Association (KMNA), Citizens Crime Watch, Parents-Teachers Association, and Parish Social<br />

Services. Except for <strong>the</strong> Parish Social Services, <strong>the</strong>se local organizations coordinate with <strong>the</strong><br />

barangay. A majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> barangay <strong>of</strong>ficials and staff belong to <strong>the</strong>se groups.<br />

The residents derive <strong>the</strong>ir income from various sources, including working for <strong>the</strong> municipal<br />

and barangay government and <strong>the</strong> private sector within or outside Rodriguez, engaging in<br />

small-scale business (e.g., sari-sari stores), selling perishable and non-perishable items, driving<br />

transport vehicles (e.g., pedicab/padyak [foot-pedaled tricycles], tricycles, public utility<br />

jeepneys, taxis), and providing services such as appliance repair and maintenance, automotive<br />

repair, running beauty parlours, and doing <strong>the</strong> laundry for o<strong>the</strong>r households.<br />

Camacho Phase II, Nangka, Marikina City. Camacho Phase II, located just beside <strong>the</strong> Nangka<br />

River, is in Barangay Nangka in <strong>the</strong> City <strong>of</strong> Marikina. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inhabitants reside in row <strong>of</strong><br />

two-story houses divided by concrete pavements. The settlement began as a housing project <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Marikina Settlements Office (MSO) in 2001. Under <strong>the</strong> supervision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MSO, informal<br />

settlers in <strong>the</strong> barangays <strong>of</strong> Calumpang, San Roque, Sto. Niño, and Parang were organized and<br />

resettled in Balubad. Balubad has been <strong>the</strong> main contributing factor in Nangka’s changing<br />

demographics. It was designated by <strong>the</strong> city government, through <strong>the</strong> MSO, as <strong>the</strong> formal<br />

relocation site for its evicted informal settlers. 6 The resettled communities became known as<br />

NHA Balubad, New Balubad Settlement Site, Camacho, and Bayabas. This was part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mr.<br />

Bayani Fernando’s vision <strong>of</strong> Marikina as a “squatter-free city” when he became mayor in <strong>the</strong><br />

early 1990s. At present, <strong>the</strong> Balubad population (3,014 families) comprises a third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

barangay’s total population, according to <strong>the</strong> latest data from <strong>the</strong> Barangay Office. This number<br />

includes <strong>the</strong> 287 families (mostly relocated from Tañong, Sto. Niño, Marikina Heights, and<br />

Parang) that comprise Camacho Phase-II.<br />

Gawad Kalinga adopted Camacho Phase II in 2004, when forty families from an informal<br />

settlement in Provident Village in Tañong, Marikina relocated to Camacho. Organized under <strong>the</strong><br />

12

Nawasa Neighborhood Association (NNA), <strong>the</strong>se families sought <strong>the</strong> help <strong>of</strong> GK for <strong>the</strong>ir housing<br />

needs. Since 2005, GK has facilitated <strong>the</strong> building <strong>of</strong> two-story houses for about sixty<br />

households, which include not only <strong>the</strong> forty NNA families but also about twenty o<strong>the</strong>r families.<br />

GK, under its sweat equity program, plans to help continue this initiative <strong>of</strong> building and<br />