Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

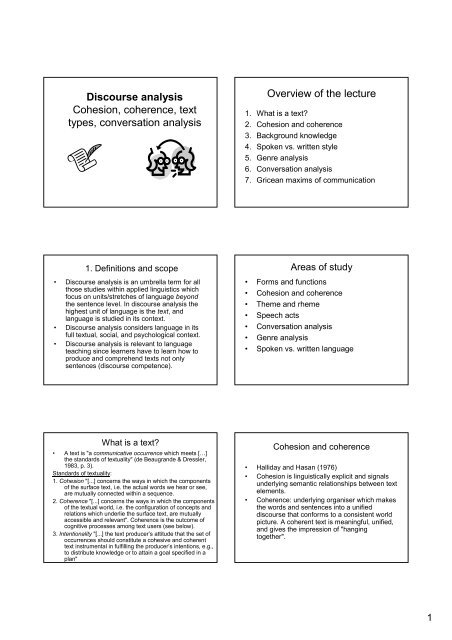

Discourse analysis<br />

Cohesion, coherence, text<br />

types, conversation analysis<br />

1. Definitions and scope<br />

• Discourse analysis is an umbrella term for all<br />

those studies within applied linguistics which<br />

focus on units/stretches of language beyond<br />

the sentence level. In discourse analysis the<br />

highest unit of language is the text, and<br />

language is studied in its context.<br />

• Discourse analysis considers language in its<br />

full textual, social, and psychological context.<br />

• Discourse analysis is relevant to language<br />

teaching since learners have to learn how to<br />

produce and comprehend texts not only<br />

sentences (discourse competence).<br />

What is a text?<br />

• A text is "a communicative occurrence which meets […]<br />

the standards of textuality" (de Beaugrande & Dressler,<br />

1983, p. 3).<br />

Standards of textuality:<br />

1. Cohesion "[...] concerns the ways in which the components<br />

of the surface text, i.e. the actual words we hear or see,<br />

are mutually connected within a sequence.<br />

2. Coherence "[...] concerns the ways in which the components<br />

of the textual world, i.e. the configuration of concepts and<br />

relations which underlie the surface text, are mutually<br />

accessible and relevant". Coherence is the outcome of<br />

cognitive processes among text users (see below).<br />

3. Intentionality "[...] the text producer’s attitude that the set of<br />

occurrences should constitute a cohesive and coherent<br />

text instrumental in fulfilling the producer’s intentions, e.g.,<br />

to distribute knowledge or to attain a goal specified in a<br />

plan"<br />

Overview of the lecture<br />

1. What is a text?<br />

2. Cohesion and coherence<br />

3. Background knowledge<br />

4. Spoken vs. written style<br />

5. Genre analysis<br />

6. Conversation analysis<br />

7. Gricean maxims of communication<br />

Areas of study<br />

• Forms and functions<br />

• Cohesion and coherence<br />

• Theme and rheme<br />

• Speech acts<br />

• Conversation analysis<br />

• Genre analysis<br />

• Spoken vs. written language<br />

Cohesion and coherence<br />

• Halliday and Hasan (1976)<br />

• Cohesion is linguistically explicit and signals<br />

underlying semantic relationships between text<br />

elements.<br />

• Coherence: underlying organiser which makes<br />

the words and sentences into a unified<br />

discourse that conforms to a consistent world<br />

picture. A coherent text is meaningful, unified,<br />

and gives the impression of "hanging<br />

together".<br />

1

Categories of discourse cohesion<br />

Grammatical<br />

Lexicogrammatical<br />

Lexical<br />

Reference<br />

Arthur's very proud of his Chihuahuas. I don't<br />

like them.<br />

Substitution<br />

Tell a story. – I don't know one.<br />

Ellipsis<br />

How did you enjoy the paintings? – A lot (of the<br />

paintings) were very good but not all (the<br />

paintings).<br />

Conjunction<br />

They thought he didn't believe them. And this<br />

was true.<br />

Lexical cohesion<br />

He met an old lady. The lady was looking at<br />

him for a while...<br />

Relationship between cohesion and<br />

coherence<br />

• Cohesion and coherence are related notions, but they<br />

are clearly distinct. There are two types of views<br />

concerning their relationship.<br />

A) Cohesion is neither necessary nor sufficient to account<br />

for coherence.<br />

A: That's the telephone.<br />

B: I'm in the bath.<br />

A: O.K.<br />

(Widdowson, 1978, p. 12)<br />

B) Cohesion is necessary, though not sufficient in the<br />

creation of coherent texts. In other words, cohesion is<br />

a crucial though not exclusive factor contributing to<br />

coherence, since it facilitates the comprehension of<br />

underlying semantic relations.<br />

Some areas of investigation<br />

• How does cohesion contribute to coherence in native<br />

speech/writing?<br />

• How does cohesion contribute to coherence in non-native<br />

speech/writing?<br />

• Comparison of cohesion in native and non-native<br />

speech/writing;<br />

• Comparing cohesion in different genres (newspaper<br />

articles, novels, informal letters, informal dialogues, etc.);<br />

• Cohesion in child language and adult language;<br />

• Cohesion at the different levels of language proficiency;<br />

• Cohesion in different languages;<br />

• Cohesion in disordered vs. normal talk;<br />

• Cohesion in translations;<br />

• Teaching cohesion to non-native speakers.<br />

Reference<br />

• Anaphoric reference: referring<br />

backwards E.g. I can see a bird. It is<br />

singing. (It refers backwards to bird.)<br />

• Cataphoric reference: referring forward.<br />

E.g. When they arrived at the house, all<br />

the participants were very tired. (They<br />

refers forward to participants).<br />

Background knowledge (schemata)<br />

• Frames: data structures that represent stereotypical<br />

situations.<br />

• Scripts: contain information on event sequences.<br />

Scripts may include scenes, roles and props.<br />

• Scripts help explain that expectations play an<br />

important role in understanding discourse. When we<br />

hear a situation being described, we expect that<br />

certain events take place.<br />

• Schema/schemata: high-level complex knowledge<br />

structures (van Dijk, 1977) that help the organisation<br />

and interpretation of one's experience. "Schemata lead<br />

us to expect or predict aspects in our interpretation of<br />

discourse" (Brown & Yule, 1983, p. 248). Schemata<br />

help explain why a text is understood easier and faster<br />

if a title is provided.<br />

• Schemata can also be culture-specific; for example the<br />

schema of a wedding ceremony varies culture by<br />

culture.<br />

Text types: Comparing written and<br />

spoken texts<br />

1. Written language<br />

Functions of written language:<br />

• action: e.g. public signs, product labels and instructions,<br />

recipes, maps, TV-guides, bills, menus, telephone<br />

directories.;<br />

• social contact: e.g. letters, postcards, greeting cards;<br />

• information: e.g. newspapers, magazines, non-fiction<br />

books, textbooks, advertisements, reports, guidebooks;<br />

• entertainment: e.g. light magazines, fiction books,<br />

poetry, drama, film subtitles, games.<br />

2

Spoken language<br />

• Intonation expresses grammatical, attitudinal, and<br />

discourse meaning.<br />

• Tone (melody): fall, rise-fall, rise, fall-rise, level<br />

• Prominence<br />

• It was INteresting.<br />

• It WAS interesting.<br />

• Functions of spoken language:<br />

• action: guidelines or directions given, teacher<br />

instructions;<br />

• social contact: telephone conversations, chats;<br />

• information: lecture, presentation, political speech;<br />

• entertainment: jokes, radio programs<br />

Genre analysis<br />

All text-types have their own system of linguistic, rhetorical<br />

and organisational characteristics. Therefore, genre<br />

analysts set out to investigate what makes a letter a<br />

letter, or what makes a radio announcement a radio<br />

announcement.<br />

"A genre comprises a class of communicative events the<br />

members of which share some set of communicative<br />

purposes. These purposes are recognized by the expert<br />

members of the parent discourse community, and<br />

thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. This<br />

rationale shapes the schematic structure of the<br />

discourse and influences and constrains choice of<br />

content and style. … Exemplars of a genre exhibit<br />

various patterns of similarity in terms of structure, style,<br />

content and intended audience. If all high probability<br />

expectations are realized, the exemplar will be viewed as<br />

prototypical by the parent discourse community"<br />

(Swales, 1990, p. 58).<br />

Conversation analysis<br />

Conversation has been considered as the most<br />

fundamental means of conducting human affairs since<br />

this is the prototypical kind of language usage.<br />

Purposes of conversation:<br />

• Exchange of information<br />

• Creating and maintaining social relationships (e.g.<br />

friendships)<br />

• Negotiation of status and social roles<br />

• Deciding on and carrying out joint actions (co-operation)<br />

The primary and overriding function of conversation is<br />

clearly the social function, i.e. the maintenance of social<br />

relationships.<br />

Spoken language<br />

Shared situation<br />

On-line interaction<br />

(two-way)<br />

Verbal and non-verbal<br />

means<br />

No careful editing<br />

Time pressure<br />

Written language<br />

No shared situation<br />

Delayed interaction<br />

(one-way)<br />

Verbal means<br />

Revising, editing<br />

possible<br />

No time pressure<br />

Linguistic analyses of various genres<br />

Linguistic phenomenon<br />

lexical density: ratio of<br />

grammatical (function) words<br />

and lexical (content) words<br />

nominalization: number of<br />

nouns<br />

type/token ratio: number of<br />

newly introduced lexical<br />

items<br />

repetition: number of<br />

repeated lexical items<br />

personal pronouns (1st and<br />

2nd person)<br />

Frequency<br />

Formal (informational<br />

genres) informal genres<br />

Formal (informational<br />

genres) informal genres<br />

Formal (informational<br />

genres) informal genres<br />

Formal (informational<br />

genres) informal genres<br />

Formal (informational<br />

genres) informal genres<br />

Conversational rules and structure<br />

• Openings: There are conventional routines for openings.<br />

E.g.: greetings, introduction, opening questions.<br />

• Closings: Intentions to close a conversation are usually<br />

expressed with closing signals such as 'well', 'so', 'okay'<br />

used with falling intonation.<br />

• Turn-taking mechanisms: intention to let the<br />

conversational partner speak is signalled with low voice,<br />

slowing down, putting a question, body movement. In<br />

smooth communication less than five per cent is<br />

delivered in overlap.<br />

• Adjacency pairs: utterances which require an immediate<br />

response or reaction from the partner (greeting-greeting,<br />

offer-accept, compliment-thank, question-answer); there<br />

are always preferred and non-preferred answers, and it<br />

is difficult for learners to distinguish between them<br />

• Back-channelling: signals that show the speaker that<br />

his/her message is understood and listened to.<br />

Examples: Uhhuh, yeah, right.<br />

3

Gricean maxims of communication<br />

Grice (1975) proposed four criteria for co-operative<br />

communication:<br />

A) Maxim of relevance: In communication, each person's<br />

contribution has to be relevant to the topic. For<br />

example in the following exchange this maxim is not<br />

observed:<br />

A: Would you like some coffee?<br />

B: I disagree with this solution.<br />

B) Maxim of truthfulness: Contributions in conversations<br />

should be truthful (exceptions are jokes, deliberate<br />

lies).<br />

c) Maxim of quantity: In conversations, talking time should<br />

be fairly divided between interlocutors, and one should<br />

strive for brevity (this maxim is often not observed).<br />

D) Maxim of clarity: Messages conveyed should not be<br />

obscure or ambiguous.<br />

Overview<br />

• What is cohesion and what is coherence?<br />

• What is the relationship between cohesion and<br />

coherence?<br />

• What are the categories of discourse cohesion in<br />

English? Illustrate each category with an example.<br />

• How do frames, scripts and schemata help understand<br />

discourse?What are the differences between spoken<br />

and written language?<br />

• List examples for the functions of spoken and written<br />

language.<br />

• List some aspects of comparison in genre analysis.<br />

• How do formal genres differ from informal genres?<br />

• List the four main purposes of conversation.<br />

• What characterises conversations?<br />

• List some elements of conversation and give an<br />

example for each.<br />

• List and explain Grice's (1975) four maxims.<br />

Non-observance of maxims<br />

Flouting a maxim: the speaker blatantly fails to observe<br />

the maxim, because he wants to the hearer to find<br />

additional meaning to the one expressed. This is called<br />

conversational implicature. For example:<br />

• How are you getting there?<br />

• We are getting there by car (meaning you are not<br />

coming with us – maxim of quantity flouted because it<br />

would have been enough to say by car).<br />

Violating a maxim – speaker wants to mislead the listener<br />

intentionally.<br />

Infringing a maxim – not observing the maxim because of<br />

lack of linguistic knowledge (e.g. L2 learners).<br />

Opting out of a maxim – the speaker is unwilling to abide<br />

by the maxims (e.g. withholding information).<br />

Suspending a maxim – in certain situations it is not<br />

necessary to observe the maxims (e.g. poetry).<br />

4