International Conference "Niccolò Paganini ... - Violin Intonation

International Conference "Niccolò Paganini ... - Violin Intonation

International Conference "Niccolò Paganini ... - Violin Intonation

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Conference</strong> "<strong>Niccolò</strong> <strong>Paganini</strong> Diabolus in Musica" 2009<br />

SDC Spezia in Festival paganiniano & Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Philippe Borer<br />

The chromatic scale in the compositions of Viotti and <strong>Paganini</strong>:<br />

A turning-point in violin playing and writing for strings 1 .<br />

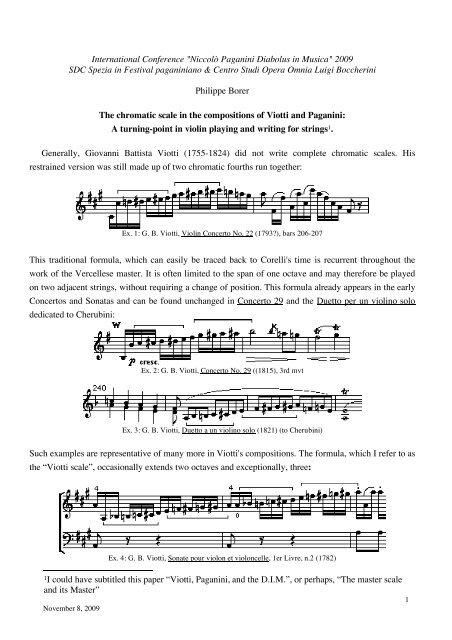

Generally, Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824) did not write complete chromatic scales. His<br />

restrained version was still made up of two chromatic fourths run together:<br />

Ex. 1: G. B. Viotti, <strong>Violin</strong> Concerto No. 22 (1793?), bars 206-207<br />

This traditional formula, which can easily be traced back to Corelli's time is recurrent throughout the<br />

work of the Vercellese master. It is often limited to the span of one octave and may therefore be played<br />

on two adjacent strings, without requiring a change of position. This formula already appears in the early<br />

Concertos and Sonatas and can be found unchanged in Concerto 29 and the Duetto per un violino solo<br />

dedicated to Cherubini:<br />

Ex. 2: G. B. Viotti, Concerto No. 29 ((1815), 3rd mvt<br />

Ex. 3: G. B. Viotti, Duetto a un violino solo (1821) (to Cherubini)<br />

Such examples are representative of many more in Viotti's compositions. The formula, which I refer to as<br />

the “Viotti scale”, occasionally extends two octaves and exceptionally, three:<br />

Ex. 4: G. B. Viotti, Sonate pour violon et violoncelle, 1er Livre, n.2 (1782)<br />

1 I could have subtitled this paper “Viotti, <strong>Paganini</strong>, and the D.I.M.”, or perhaps, “The master scale<br />

and its Master”<br />

1

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 5: G. B. Viotti, Concerto No. 2 (1783)<br />

The ascending form (anabasis) is by far the most frequent even if one can find a few examples of the<br />

descending form (e.g. Concertos 1 and 19):<br />

Ex. 6: G. B. Viotti, Concerto No. 19 (1794), Presto ma non troppo, bars 142-144<br />

Viotti's classical style was usually marked by restraint even if an atmosphere of Romanticism pervades<br />

the opening tuttis of some of the later concertos. In this respect, it would be interesting to gauge the<br />

opposing influences of his teacher Pugnani (1731-1798) and the composer Cherubini (1760-1842) 2 . Be as<br />

it may, Viotti's recurrent and predictable use of ready-made formulas such as the incomplete chromatic<br />

scale denotes a rather conservative stance. However, to most every rule there is an exception. To my<br />

knowledge, there are only two isolated cases of an infringement on Viotti's self-imposed rule (this by the<br />

way, strikes a blow to the statement in the Abstract). These isolated examples can be found in the first<br />

movement of Concerto 17, just before the cadenza, and in the Andante of Concerto 21. In both cases the<br />

orchestral accompaniment is suspended during the chromatic passage:<br />

Ex. 7: G. B. Viotti, Concerto No. 17 (1789), 1st mvt, bars 288-291<br />

Ex. 8: G. B. Viotti, Concerto No. 21 (1793), 2nd mvt, bars 24-27<br />

These two works belong to a chaotic period. Concerto 17 4 was composed in Paris at the outbreak of the<br />

Revolution (July 1789) and Concerto 21, with its lyrical Andante, was premiered in London (7 February<br />

1793) just two weeks after the execution of King Louis XVI (1754-†21.01.1793). Viotti had fled the<br />

Reign of Terror in July of 1792, just in time to find refuge in England. Interestingly enough, the breach<br />

2 I would risk speculating on Cherubini's intervention, from about 1789, in the orchestration and in the harmonic<br />

realization of the opening tuttis of Viotti's concertos. Between the two friends there existed a mutual esteem and a<br />

genuine sharing of interest since Cherubini was acting as Viotti's publisher.<br />

3 One could consider that transgression is not entirely achieved or at least weakened by the<br />

reinstatement of the tonic.<br />

4 Both <strong>Paganini</strong> and Wieniawski had included this Concerto in their concert repertories.<br />

3<br />

2

of compositional rules coincided with these events. In his later compositions, including Concertos 22 to<br />

29, Viotti returned to the old formula.<br />

In contrast with Viotti, <strong>Niccolò</strong> <strong>Paganini</strong> (1782-1840) frequently used the complete succession of twelve<br />

pitches and did not hesitate to cover the entire register of the violin:<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 9: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Scala di <strong>Paganini</strong>, Breslau 1829<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong> noted this scale on an album leaf. The document, entitled Scala di <strong>Paganini</strong>, and dated Breslau<br />

1829, resembles a composer's manifesto. Since <strong>Paganini</strong> wanted to associate his name with this scale, it is<br />

clear that it was of special significance for him. Several other documents exist which bear witness to<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong>'s preoccupation with the chromatic scale. Here, for example, is a chromatic scale for piano that<br />

he wrote in Clara Wieck's album:<br />

Ex. 10: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Scala per Clara (1829)<br />

In the same vein are the Gamme chromatique et contraire (Paris 1837), and the astonishing Largo con<br />

forte espressione, e sempre crescendo, dedicated to Jean-Pierre Dantan (Paris 1837):<br />

3

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 11: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Autograph scale (Prince Wielhorski's Album, 1837)<br />

Ex. 12: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Autograph scale (J.-P. Dantan's Album, 1837)<br />

In the Caprices and in the Concertos, <strong>Paganini</strong> used the descending form (catabasis) much more :<br />

Ex. 13: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Concerto No. 4 [M.S. 60]<br />

Ex. 14: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Caprice 17 [M.S. 25], bar 7<br />

4

The descending scales "with one and the same finger" call to mind the coloraturas of virtuoso singers.<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong> transferred this vocal technique to the violin, inspired notably by the great soprano Angelica<br />

Catalani (1780-1849): 5<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 15: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Concerto No.1 [M.S. 21]<br />

Ex. 16: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Caprice 21, as notated and fingered by Carl Guhr (transcribed by ear)<br />

The term glissando associated with such passages can be misleading. It is rather a superarticulated legato.<br />

Camillo Sivori called it a glissando à crans ('notch glissando'). 7 The clear enunciation of each separate<br />

note involves a left-hand staccato. Later on,Wieniawski carefully notated a similar passage as follows:<br />

Ex. 17: H. Wieniawski, Concerto No. 2, bars 207-208<br />

(If one uses a finger glissando, then the articulation is made by the bow (ricochet bowing)<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong> used the ascending form of his scale in expressive contexts such as interrogatio or ascensio.<br />

These can be considered as written illustrations of suonare parlante (‘playing that speaks’):<br />

Ex. 18: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Concerto No.1 [M.S. 21]<br />

5 “Fa delle mezze voci per in su e per in giù, e tutto quello che fa con gran forza lo può fare con gran<br />

dolcezza, e pianissimo; ed ecco dove scaturisce tutto il magico effetto” (Letter to Germi of 18 June<br />

1823) [PE 63]<br />

6 The treble clef in mirror image indicates the scordatura<br />

7 See Herwegh (>Sivori), p.7 [like a cogwheel movement]<br />

6<br />

5

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 19: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Gran Sonata per chitarra e violino [M.S.3]<br />

Ex. 20: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Cantabile per violino e pianoforte [M.S. 109]<br />

I will now move on to a brief analysis of <strong>Paganini</strong>'s scale, starting with the notation and continuing with<br />

the implicit intervallic structure. - Contrary to common use that derives from equal temperament,<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong> adopted the same notation when ascending and descending. The result is a collection of twelve<br />

notes which he replicates in four successive octaves. 8 The harmonic relations may be depicted in the<br />

following manner:<br />

Close harmonic relations are represented by short distances and distant harmonic relations by longer<br />

distances. This harmonic network was devised by Leonhard Euler in 1774. He called it Speculum<br />

Musicum. The fifths are arranged horizontally and the thirds, vertically. The numbers indicate the rank of each<br />

note in the order of their harmonic generation (power of 3 for the fifths and power of 5 for the thirds). The slashes ( and )<br />

indicate the subtraction or the addition of one syntonic comma 80/81.<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong>'s key signature (F#, C#, G#) indicates that the major mode gives its basic structure to the scale:<br />

8L'ambito di quattro ottave è quello tradizionalmente concesso al violino, come codificato nel 1650<br />

dal Padre Kircher. Cfr. ATHANASIUS KIRCHER, Musurgia Universalis sive Ars Magna Consoni et<br />

Dissoni, Roma, Corbelletti, 1650, RHildesheim, Olms,1970, tomo I, p. 486 [«Chelys minor nobile<br />

Instrumentum, & ad harmonicarum diminutionum varietatem aptissimum. 4. ut plurimum chordis<br />

constat, quibus tamen ad 4 octavas usquè ascendunt»].<br />

6

As can be inferred from the prelude and postlude in Caprice 5, <strong>Paganini</strong>'s scale may be used both in<br />

major and minor. Therefore, it contains the notes of the two modes:<br />

On the Speculum Musicum, the two remaining notes ( and ) are diagonally opposite. Brought back<br />

into the same octave a-a', they form the interval of an augmented third 512/675:<br />

Regrettably, the current terminology does not reflect the true nature of things. The so-called "flattened<br />

second degree" is indeed the generator of the entire scale as it appears on the Speculum Musicum. In this<br />

light, the sounding of this degree (notably the Neapolitan chord) may be seen as a backward glance, as an<br />

inflection back to the origin. This explain its melancholy undertones: 9<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 21: F. Schubert, An Mignon Ex. 22: N. <strong>Paganini</strong>, Caprice 4, bars 14-16<br />

Let us now examine the relative distances between semitones and the ratios of string lengths:<br />

The ratios between notes are not constant. There are actually four different numerical ratios: 15:16,<br />

128:135, 24:25, 25:27. This means that the "semitones" are of four different sizes. We are indeed a long<br />

9 (strongly reminiscent of Schubert) Etim. dolore del ritorno (gr. nóstos+algia). Secondo la<br />

tradizione della musica pathetica tramandata da Kircher, era il numerus harmonicus ad influenzare<br />

l'ascoltatore sotto un punto di vista psichico e fisiologico.<br />

7

way from the uniformity of the tempered scale. <strong>Paganini</strong>'s scale is also known as the harmonic chromatic<br />

scale or the syntonic chromatic scale. It is basically a composer's master scale containing all the essential<br />

tone relations. This particular arranging of tones fits within the concept of melody as ‘harmony in<br />

succession’ defined by Tartini and Vallotti. Such a notion, almost completely ignored today, was still<br />

relevant to <strong>Paganini</strong> and to those violinists who had trained in the grand tradition of Corelli and Tartini<br />

(Geminiani,Galeazzi,...). Here I would like to insist on a point which is generally omitted or even banned<br />

from theory books: the inclusion of the final chromatic element, the tritone 32/45 or ), leads to the<br />

making of a new interval, the augmented third (and its complement, the diminished sixth). Striking<br />

examples can be found in Mozart, <strong>Paganini</strong>, Schubert, Chopin, and Delius 10 - in spite of the theoretician's<br />

reluctance:<br />

Ex. 23: <strong>Paganini</strong>, Caprice 14, bar 16 Ex. 24: <strong>Paganini</strong>, Caprice 7, bars 33-34<br />

Traditionally, the chromatic scale had only been used in fragments, because its constitutive element, the<br />

semitone, creates a strong expressive tension. This tension was synonymous with a lament when<br />

descending, and with making an effort when ascending. In principle, the filling out of the chromatic<br />

octave was prohibited. The tritone, or Diabolus in Musica in medieval terminology, was central to the<br />

problem. Since it divides the octave into equal halves, the tritone was seen as the intruder that destroyed<br />

the natural balance of the scale. Within a tonal context, it represented the antipodes of the tonic, a kind<br />

of point of no return in the cycle of fifths. In fact the problem can be traced back to Greek music theory<br />

and its philosophy of proportions (derived from the Tetraktys ) 11 . Here is the formula that defined the<br />

fixed tones of ancient Greek music:<br />

This can be expressed in integers as 6:8:9:12 and represents what Aristotle called the "Framework of<br />

Harmony". These numbers work in reciprocal ways (i.e. string length or frequency) and therefore apply<br />

to both rising and falling pitch sequences. For instance, in the octave on C, F and G reverse their role as<br />

arithmetic and harmonic means:<br />

10 Mozart (Symphony 40), <strong>Paganini</strong> (Caprice 7) Schubert (Impromptu G flat, Op. 90), Chopin<br />

(Étude Op. 6, N. 10) Delius (violin concerto)<br />

11 cf. Plato's Epinomis and Aristotle's "Framework of Harmony"<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

8

The ties with ancient tradition can also be felt in the terminology still in use well into the eighteenth<br />

century in Italy. For example, the letters designating notes (C, D, E, etc.) were followed by specific<br />

syllables as shown below:<br />

The syllables after the letters indicated the relation with the tones forming the “Framework of Harmony”.<br />

In other words, each note was measured from the fundamental (UT), the harmonic mean (F), and the<br />

arithmetic mean (G). Such terminology was still taught by Carlo Gervasoni in his La Scuola della<br />

Musica, published in 1800. One can find traces of it in <strong>Paganini</strong>'s correspondence and in the Elenco de<br />

pezzi di musica da stamparsi (e.g."Terzo Concerto in Elamì”).<br />

My research began with a presupposition: Viotti, as most composers since the time of Corelli, did not<br />

write complete chromatic scales for the violin. Originally, the scope of my study was limited to<br />

identifying the advent of the complete, twelve-pitch chromatic scale for the violin. I found the earliest in<br />

Mozart's work, notably in the Andante of the "Prague" Symphony 12 of 1787 and the Divertimento for<br />

<strong>Violin</strong>, Viola & Cello in E flat of 1788. 13 :<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 25: Mozart, Symphony No.38 in D major ("Prague") [K. 504]<br />

Ex. 26: Mozart, Divertimento in E flat [K. 563], Adagio<br />

This was no surprise, in view of Mozart's liking for chromatic scales and extended chromatic runs in<br />

piano compositions. Nevertheless, in earlier works for strings, such as the violin concertos and the<br />

Sinfonia Concertante, Mozart still applied the old rule and used the traditional, 'tritone-free' formula.<br />

12Mozart's Symphony 38 in D major ("Prague"), K. 504. Premiered in Prague on January 19, 1787.<br />

13 The chromatic scales in Haydn's Seven Last Words are not complete. To be considered as<br />

complete, the scale must contain the twelve notes enounced in their natural succession.<br />

9

During the detailed review of Viotti's work, I found confirmation that the restriction concerned the string<br />

instruments and in particular, the violin. In the piano version of Viotti's Concerto 19 14 , there are several<br />

complete chromatic scales that do not appear in the violin version:<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 27: G. B. Viotti, Concerto No. 19, (piano version) (1792-94) [G. 92]<br />

Writing just any consecutive notes for the piano has no impact on intonation. This is certainly not the<br />

case with vocal compositions. The precise rendering of a chromatic scale is a challenge for every singer.<br />

<strong>Paganini</strong>'s fascination for Angelica Catalani' was mentioned previously. Here is an example of how she<br />

sang the complete chromatic scale. This may well have been an unwritten tradition among virtuoso<br />

singers long before:<br />

Ex. 28: ‘Al Dolce Canto’ (Air with variations), tr. from Rode's original variations for <strong>Violin</strong><br />

The comparison with the original version shows that Rode used the old formula instead:<br />

Ex. 29: Pierre Rode, Air varié, Op.10 (Var. IV)<br />

14In the edition Naderman one can read "Ce concerto a été composé pour le piano-forte et non pour<br />

le violon". The dedicatee was probably Hélène de Montgéroult.<br />

10

<strong>Paganini</strong> does not appear to have ever performed the Beethoven Concerto in public. However he was<br />

familiar with it and played it at least once for a selected group of persons. 15 . Beethoven's chromatic scales<br />

in the first movement 16 surely caught all <strong>Paganini</strong>'s attention:<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 30: Beethoven, <strong>Violin</strong> Concerto, Op.61 (1806), 1st mvt., bars 473-475<br />

In the matter of advanced chromaticism the true predecessors of Mozart, Beethoven, <strong>Paganini</strong>, Spohr and<br />

Liszt are, surprisingly perhaps, the virtuosi and madrigalists of the later 16th century such as Gesualdo or<br />

Luca Marenzio (1553-1599). For Marenzio in particular, the chromaticism was not just a form of<br />

experimentation but the expression of passion and pain as in the emblematic beginning of Solo e<br />

pensoso, a madrigal based on Petrarch:<br />

Ex. 31: Luca Marenzio, Solo e pensoso (1599) bars 1-12 (Curva passionis)<br />

It is logical to assume that <strong>Paganini</strong>, himself an admirer of Petrarch and lover of vocal music knew this<br />

work. Another source may have been the music of the Genoese organist and virtuoso violinist<br />

Michelangelo Rossi (>Frescobaldi) (1601-1656). In Rossi, nicknamed ‘the Michel Angelo of the violin’,<br />

we find <strong>Paganini</strong>'s kindred spirit. Unfortunately, there are no extant violin compositions by Rossi. Here is<br />

the extraordinary conclusion of his Toccata 7:<br />

15Cox, J. E., Musical Recollections of the Last Half Century, 2 vols. (London: Tinsley, 1872) (vol.<br />

I, p. 199)<br />

16See also: Romance 1 in G major, Op 40 (1798); Romance 2 in F major, Op. 50 (1802)<br />

11

November 8, 2009<br />

Ex. 32: Michelangelo Rossi, Toccata No. 7 (c. 1640)<br />

As with all original thinkers, <strong>Paganini</strong> demonstrated the capacity to acquire, absorb, and assimilate<br />

knowledge, and to use this knowledge as a trigger, a necessary stepping stone to discovery. Repectful of<br />

earlier achievements, he was relentless in his eagerness to go beyond. <strong>Paganini</strong>'s exploration and use of<br />

the chromatic scale can be seen as a glance back and as an innovation, similar to his inspiration from<br />

Locatelli and the development of instrumental techniques. Significantly, all the musical illustrations<br />

contained in Liszt's letter, written just after a concert that <strong>Paganini</strong> had given at the Paris Opera, were<br />

chromatic formulas that the great pianist adopted and incorporated in his works. My conclusion agrees<br />

with Jeffrey Perry, who has observed that (quote) “<strong>Paganini</strong> the serious composer and student of new<br />

developments in music proves to have been more than a performing curiosity, indeed, he must be<br />

regarded as one of the essential masters of early Romanticism”. (unquote)<br />

-Thanks for your attention-<br />

As the time is limited I can only skim over the material I have gathered.<br />

After an outline of the xxxxx I shall propose to examine some musical examples with<br />

-1:2, a ratio of one to two<br />

Corelli (1653-1713)<br />

Tartini (1692-1770)<br />

12

<strong>Paganini</strong>'s instrumental and musical background. It has often been claimed that <strong>Paganini</strong> was self-taught. However, evidence<br />

of his all-important early training in violin and composition makes him the true heir of the old Italian masters, representing<br />

at the same time a vital milestone for subsequent development of instrumental and compositional techniques. <strong>Paganini</strong> can<br />

thus be seen as representing a link between the classico-romantic and modern attitudes to instrumental writing reaching well<br />

into the twentieth century.<br />

In Chapter IV, some aspects of <strong>Paganini</strong>'s compositional and performing styles are examined. A striking interpretative<br />

concept (the "suonare parlante") is discussed.<br />

“The <strong>Paganini</strong> of the Caprices, although already known for flamboyance and extravagant virtuosity, is a serious composer and<br />

a student of contemporary developments in music ”(Perry)<br />

As with all original thinkers, <strong>Paganini</strong> offers evidence of a capacity not only to acquire, absorb, and assimilate knowledge, but<br />

also to use that knowledge as a point of departure, a necessary stepping stone to discovery. Whilst repectful of earlier<br />

achievements, he was relentless in his consideration of what might be possible. Jeffrey Perry observed that “by<br />

introducing a dichotomy between lyrical melody and a new, unstable element that draws its energy from<br />

new understanding of register, phrase structure, motivic content (and one could add timbre and<br />

articulation in the case of <strong>Paganini</strong>), composers of the early nineteenth century expanded the expressive<br />

range of Western art music and fundamentally changed its expressive essence. The <strong>Paganini</strong> Caprices<br />

present one of the earliest and most compelling examples of this transformation, proving the Genoese<br />

master to have been more than a performing curiosity, indeed, he must be regarded as one of the essential<br />

masters of early Romanticism”<br />

These formulas deserve to be carefully studied particularly in terms of intonation.<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

13

The eleven-pitch scale with its two disjointed chromatic fourth is a closed system whereas the twelve-<br />

pitch scale with the tritone as both its divisor and pivot becomes a open system.<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

Fig. 1 “For artists of the early nineteenth century, Romanticism is the aesthetic of distance”<br />

This twelve-tone two-dimensional array, or map, is but a sample of the greater constellation of tones. It<br />

can be extended indefinitely in each of the four directions.<br />

.<br />

“The <strong>Paganini</strong> of the Caprices, although already known for flamboyance and extravagant virtuosity, is a serious composer and<br />

a student of contemporary developments in music ”(Perry)<br />

the chromatic scale's "missing tone".<br />

The exception which proves the rule.<br />

Joseph Haydn: his three violin concertos were written before 1770<br />

Mozart: he wrote his five violin concertos in 1775<br />

-polarità di spiriti classici e di presagi romantici<br />

polarity of classical spirit and romantic presages/premonitions//foreshadow//399.2<br />

-Louis XVI (1754-† 21.01.1793) -Marie-Antoinette (1755-† 16.10.1793)<br />

-One should bear in mind that by the time Mozart had already written his five violin concertos, young<br />

Viotti was still playing in the second violin section in the orchestra of the Teatro Regio of Turin and had<br />

not yet officially received a contract. He therefore had every opportunity to familiarize ihmself with the<br />

works of the Austrian musician before starting to write his own concerti (Viotti's first violin concerto is<br />

dated 17..)<br />

-It was in 1789, in the middle of the Revolution that Viotti wrote his seventeenth Concerto. It took some<br />

time before the work was premiered by Rode in 1792 at the concerts of Rue Feydeau. As Dellaborra<br />

observes (p.74) Concerto 17 shares a affinity with Mozart, whose intensely expressive d minor piano<br />

concerto of 1785 was a premonition of profound changes and turmoil. While Mozart's influence could<br />

already be felt in Viotti's early compositions it was on a rather superficial level of formulation and<br />

thematic quotation. As regards Concerto 17, particularly the first movement, deeper affinities can be<br />

discerned, in particular the denser harmonic texture and the remarkable chromatic episode in the solo<br />

violin part, which, to my knowledge has no counterpart in Viotti's entire production. [In addition to<br />

Mozart's influence, I would risk speculating on Cherubini's intervention in the orchestration and in the<br />

harmonic realization of the opening tutti. It is not surprising that both <strong>Paganini</strong> and Wieniawski had<br />

included the first movement of this concerto in their repertoire (Wieniawski even wrote a cadenza to it).<br />

The importance of chromatic passages, particularly bars 288-289, did not escape Wieniawski's attention,<br />

as we can infer from Leopold Lichtenberg's careful editing of the passage:<br />

14

As the time is limited I can only skim over the material I have gathered.<br />

After an outline of the xxxxx I shall propose to examine some musical examples with short<br />

comments.<br />

SLIDES<br />

Viotti's impact on the upcoming generation of violinists and composers proved to be considerable.<br />

However Viotti's stature as a violinist and composer has perhaps been appreciated on the grounds of his<br />

overarching influence in his roles as a musician, concert manager, opera administrator, and freemason.<br />

The official view of Viotti as//the «father of modern violin playing» 17 should be re-examined not only<br />

with reference to Moser's dismissal but also in the light of musicológical study. Viotti exerted a lasting<br />

musical influence through his pupil Pierre Rode who perpetuated his compositional style. Rode indeed<br />

modelled his violin concertos after those of Viotti, faithfully following the instructions laid down by his<br />

teacher, including elements such as the eleven-pitch chromatic scale which I shall refer to as the “Viotti<br />

scale”.<br />

With the establishment of such distant relations of tone.<br />

This paper aims to shed light on the transition from the traditional formula used by Viotti to the<br />

systemátic utilisation of twelve-pitch 'chromatic' scales and extended chromatic runs in violin music.<br />

The source material includes several violin methods which appeared between 1750 and 1850, some of<br />

the theoretical writings of Giuseppe Tartini, as well as more informal dócuments such as letters and<br />

reviews. Special émphasis is placed on relevant passages from the compositions/works of Giornovichi,<br />

Mozart, Kreutzer, Beethoven, Rode, Bohrer, and Spohr. ...<br />

"Le Tutti du 18e fut applaudi comme une des belles symphonies de Haydn" (Baillot)<br />

'<strong>Paganini</strong>'s scale' fails to conform with the current New Grove definition: «In melodic and harmonic analysis the term<br />

'chromatic' id generally applied to notes marked with accidentals foreign to the scale of the key in which the passage is<br />

written» 18<br />

(While Viotti preferred the ascending form of his scale, <strong>Paganini</strong> had a strong inclination for the descending one)<br />

.<br />

17 Perhaps a Baillot's edict/decree?<br />

18 See The Empirical Music Review<br />

November 8, 2009<br />

15