(EL) Policy and Procedures Manual 9-6-11 Appendix Revised ... - Alex

(EL) Policy and Procedures Manual 9-6-11 Appendix Revised ... - Alex

(EL) Policy and Procedures Manual 9-6-11 Appendix Revised ... - Alex

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1 | P a g e<br />

POLICY AND PROCEDURES<br />

MANUAL APPENDIX<br />

Alabama State Department of Education<br />

Federal Programs Section<br />

Post Office Box 302101<br />

Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101<br />

(334) 353-4544<br />

1-888-725-9321

2 | P a g e<br />

ENGLISH LEARNERS (<strong>EL</strong>s)<br />

POLICY & PROCEDURES MANUAL<br />

This document, English Learners (<strong>EL</strong>s) <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Procedures</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>, is an outgrowth of the<br />

Alabama State Department of Education’s voluntary agreement with the U.S. Department of<br />

Education, Office for Civil Rights (Compliance Review #04-98-5023), for providing services to<br />

students who are English learners (<strong>EL</strong>s). It incorporates requirements <strong>and</strong> applicable references to<br />

Title III of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB). This document is intended to provide<br />

basic requirements <strong>and</strong> guidance for policies, procedures, <strong>and</strong> practices for identifying, assessing,<br />

<strong>and</strong> serving <strong>EL</strong>s. While the term limited-English proficient (LEP) is used in legal <strong>and</strong> official<br />

documents, the <strong>EL</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Procedures</strong> <strong>Manual</strong> refers to LEP students as <strong>EL</strong>s. Questions about<br />

responsibilities of local education agencies (LEAs) in providing English language services may be<br />

directed to:<br />

Dr. Tommy Bice, Deputy State Superintendent of Education tbice@alsde.edu<br />

Dr. Tammy H. Starnes, Title III/State <strong>EL</strong> Coordinator tstarnes@alsde.edu<br />

Mrs. Dely Velez Roberts, <strong>EL</strong> Specialist/Title I droberts@alsde.edu<br />

Printing costs for this document were supported by Title III.

Legal Cases Related to English Learners<br />

1964 Civil Rights Act, Title VI<br />

“No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color or national origin, be excluded from<br />

participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or<br />

activity receiving federal financial assistance.” -42 U.S.C. § 2000d.<br />

o Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects people from discrimination based on race, color or<br />

national origin in programs or activities that receive Federal financial assistance. Public institutions<br />

(like schools) must provide equal quality of educational services to everyone, including those who are<br />

Limited English Proficient (LEP). Title VI covers all educational programs <strong>and</strong> activities that receive<br />

Federal financial assistance from the United States Department of Education (ED).<br />

May 25, 1970, Memor<strong>and</strong>um<br />

“The purpose of this memor<strong>and</strong>um is to clarify policy on issues concerning the responsibility of LEAs to<br />

provide equal educational opportunity to national origin minority group children deficient in English<br />

language skills.<br />

o Where inability to speak <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the English language excludes national origin-minority group<br />

children from effective participation in the education program offered by a LEA, the LEA must take<br />

affirmative steps to rectify the language deficiency in order to open its instructional program to these<br />

students. School districts have the responsibility to notify national origin- minority group parents of<br />

school activities, which are called to the attention of other parents. Such notice in order to be adequate<br />

may have to be provided in a language other than English.<br />

Lau v. Nichols (US Supreme Court Decision 1974)<br />

“The failure of school system to provide English language instruction to approximately national origin<br />

students who do not speak English, or to provide them with other adequate instructional procedures,<br />

denies them a meaningful opportunity to participate in the public educational program, <strong>and</strong> thus<br />

violates § 601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bans discrimination based "on the ground of race,<br />

color, or national origin," in "any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance," <strong>and</strong> the<br />

implementing regulations of the Department of Health, Education, <strong>and</strong> Welfare. Pp. 414 U. S. 565-569.”<br />

o The Supreme Court stated that these students should be treated with equality among the schools.<br />

Among other things, Lau reflects the now-widely accepted view that a person's language is so closely<br />

intertwined with their national origin (the country someone or their ancestors came from) that<br />

language-based discrimination is effectively a proxy for national origin discrimination.<br />

1974– Equal Education Opportunities Act<br />

“The Equal Education Opportunities Act of 1974 states: “No state shall deny equal educational<br />

opportunity to an individual based on his or her race, color, sex, or national origin by the failure of an<br />

educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal<br />

participation by its students in its instructional programs.”<br />

o The EEOA prohibits discriminatory conduct against, including segregating students on the basis of race,<br />

color or national origin, <strong>and</strong> discrimination against faculty <strong>and</strong> staff serving these groups of individuals,<br />

as it interferes with their equal educational opportunities. Furthermore, the EEOA requires LEAs to<br />

take action to overcome students' language barriers that impede equal participation in educational<br />

programs.<br />

Plyler v. Doe (U.S. Supreme Court Decision 1982)<br />

“The illegal aliens who are plaintiffs in these cases challenging the statute may claim the benefit of the<br />

Equal Protection Clause, which provides that no State shall „deny to any person within its jurisdiction<br />

the equal protection of the laws‟ . . . The undocumented status of these children does not establish a<br />

sufficient rational basis for denying them benefits that the State affords other residents . . . No national<br />

3 | P a g e

policy is perceived that might justify the State in denying these children an elementary education.” -457<br />

U.S. 202<br />

o The right to public education for immigrant students regardless of their legal status is guaranteed.<br />

o Schools may not require proof of citizenship or legal residence to enroll or provide services to<br />

immigrant students.<br />

o Schools may not ask about the student or a parent’s immigration status.<br />

o Parents are not required to give a Social Security number.<br />

o Students are entitled to receive all school services, including the following:<br />

Free or reduced breakfast or lunch, – transportation, – educational services, <strong>and</strong> – NCLB, IDEA,<br />

etc.<br />

Presidential Executive Order 13166<br />

“Entities receiving assistance from the federal government must take reasonable steps to ensure that<br />

persons with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) have meaningful access to the programs, services, <strong>and</strong><br />

information those entities provide.”<br />

o Recipients of federal assistance are required to help students overcome language barriers by<br />

implementing consistent st<strong>and</strong>ardized language assistance programs for LEP. In addition, persons with<br />

limited English proficiency cannot be required to pay for services to ensure their meaningful <strong>and</strong><br />

equitable access to programs, services, <strong>and</strong> benefits.<br />

2001 – Title III of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001<br />

“Title III of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act requires that all English language learners (<strong>EL</strong>Ls)<br />

receive quality instruction for learning both English <strong>and</strong> grade-level academic content.<br />

NCLB allows local flexibility for choosing programs of instruction, while dem<strong>and</strong>ing greater<br />

accountability for <strong>EL</strong>s' English language <strong>and</strong> academic progress.”<br />

o Under Title III, states are required to develop st<strong>and</strong>ards for English Language Proficiency <strong>and</strong> to link<br />

those st<strong>and</strong>ards to the state's Academic Content St<strong>and</strong>ards. Schools must make sure that <strong>EL</strong>Ls are part<br />

of their state's accountability system <strong>and</strong> that <strong>EL</strong>s' academic progress is followed over time by<br />

o establishing learning st<strong>and</strong>ards, that is, statements of what children in that state should know <strong>and</strong> be<br />

able to do in reading, math, <strong>and</strong> other subjects at various grade levels;<br />

o creating annual assessments (st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests, in most states) to measure student progress in<br />

reading <strong>and</strong> math in grades 3-8 <strong>and</strong> once in high schools;<br />

o setting a level (cut-off score) at which students are considered proficient in tested areas; <strong>and</strong><br />

o Reporting to the public on what percentages of students are proficient, with the information broken<br />

down by race, income, disability, language proficiency, <strong>and</strong> gender subgroups.<br />

Castañeda v. Pickard, [5th Cir., 1981] 648 F.2d 989 (US COURT OF APPEALS)<br />

“In 1981, in the most significant decision regarding the education of language-minority students since<br />

Lau v. Nichols, the 5th Circuit Court established a three-pronged test for evaluating programs serving<br />

English language learners. According to the Castañeda st<strong>and</strong>ard, schools must base their program on<br />

educational theory recognized as sound or considered to be a legitimate experimental strategy, –<br />

implement the program with resources <strong>and</strong> personnel necessary to put the theory into practice, <strong>and</strong> –<br />

evaluate programs <strong>and</strong> make adjustments where necessary to ensure that adequate progress is being<br />

made. [648 F. 2d 989 (5th Circuit, 1981)].”<br />

This case established a three-part test to evaluate the adequacy of a district's program for the English<br />

language learner:<br />

1. Is the program based on an educational theory recognized as sound by some experts in the field or is it<br />

considered by experts as a legitimate experimental strategy?<br />

2. Are the programs <strong>and</strong> practices, including resources <strong>and</strong> personnel, reasonably calculated to<br />

implement this theory effectively?<br />

3. Does the school district evaluate its programs <strong>and</strong> make adjustments where needed to ensure that<br />

language barriers are actually being overcome?<br />

4 | P a g e

Key Vocabulary for English Learners<br />

http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/ell/glossary.html<br />

ACCESS: is a st<strong>and</strong>ards-based, criterion referenced English language proficiency test. It<br />

assesses social <strong>and</strong> instructional English as well as the language associated with language<br />

arts, mathematics, science, <strong>and</strong> social studies within the school context across the four<br />

language domains.<br />

BICS: Basic interpersonal communication skills. The language ability required for verbal<br />

face-to-face communication.<br />

CALP: Cognitive academic language proficiency. The language ability required for<br />

academic achievement.<br />

Castañeda v. Pickard: On June 23, 1981, the Fifth Circuit Court issued a decision that is<br />

the seminal post-Lau decision concerning education of language minority students. The<br />

case established a three-part test to evaluate the adequacy of a district's program for <strong>EL</strong>L<br />

students: (1) is the program based on an educational theory recognized as sound by some<br />

experts in the field or is considered by experts as a legitimate experimental strategy; (2)<br />

are the programs <strong>and</strong> practices, including resources <strong>and</strong> personnel, reasonably calculated<br />

to implement this theory effectively; <strong>and</strong> (3) does the school district evaluate its programs<br />

<strong>and</strong> make adjustments where needed to ensure language barriers are actually being<br />

overcome? [648 F.2d 989 (5th Cir., 1981)]<br />

Content-based English as a Second Language: This approach makes use of instructional<br />

materials, learning tasks, <strong>and</strong> classroom techniques from academic content areas as the<br />

vehicle for developing language, content, cognitive <strong>and</strong> study skills. English is used as the<br />

medium of instruction.<br />

Dual Language Program: Also known as two-way or developmental, the goal of these<br />

bilingual programs is for students to develop language proficiency in two languages by<br />

receiving instruction in English <strong>and</strong> another language in a classroom that is usually<br />

comprised of half native English speakers <strong>and</strong> half native speakers of the other language.<br />

<strong>EL</strong>: English learner. A national-origin-minority student who is limited-English-proficient.<br />

This term is often preferred over limited-English-proficient (LEP) as it highlights<br />

accomplishments rather than deficits.<br />

English as a Second Language (ESL): A program of techniques, methodology <strong>and</strong> special<br />

curriculum designed to teach <strong>EL</strong>L students English language skills, which may include<br />

listening, speaking, reading, writing, study skills, content vocabulary, <strong>and</strong> cultural<br />

orientation. ESL instruction is usually in English with little use of native language.<br />

Equal Education Opportunities Act of 1974: This civil rights statute prohibits states from<br />

denying equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race,<br />

color, sex, or national origin. The statute specifically prohibits states from denying equal<br />

educational opportunity by the failure of an educational agency to take appropriate action<br />

to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its<br />

instructional programs. [20 U.S.C. §1203(f)]<br />

FLEP: Fluent (or fully) English proficient.<br />

5 | P a g e

Informed Parental Consent: The permission of a parent to enroll their child in an <strong>EL</strong><br />

program, or the refusal to allow their child to enroll in such a program, after the parent is<br />

provided effective notice of the educational options <strong>and</strong> the district's educational<br />

recommendation.<br />

Language Dominance: Refers to the measurement of the degree of bilingualism, which<br />

implies a comparison of the proficiencies in two or more languages.<br />

Language Proficiency: Refers to the degree to which the student exhibits control over the<br />

use of language, including the measurement of expressive <strong>and</strong> receptive language skills in<br />

the areas of phonology, syntax, vocabulary, <strong>and</strong> semantics <strong>and</strong> including the areas of<br />

pragmatics or language use within various domains or social circumstances. Proficiency in<br />

a language is judged independently <strong>and</strong> does not imply a lack of proficiency in another<br />

language.<br />

Lau v. Nichols: A class action suit brought by parents of non-English-proficient Chinese<br />

students against the San Francisco Unified School District. In 1974, the Supreme Court<br />

ruled that identical education does not constitute equal education under the Civil Rights<br />

Act of 1964. The court ruled that the district must take affirmative steps to overcome<br />

educational barriers faced by the non-English speaking Chinese students in the district.<br />

[414 U.S. 563 (1974)]<br />

LEP: Limited-English-proficient. (See <strong>EL</strong>L)<br />

Maintenance Bilingual Education (MBE): MBE, also referred to as late-exit bilingual<br />

education, is a program that uses two languages, the student's primary language <strong>and</strong><br />

English, as a means of instruction. The instruction builds upon the student's primary<br />

language skills <strong>and</strong> develops <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>s the English language skills of each student to<br />

enable him or her to achieve proficiency in both languages, while providing access to the<br />

content areas.<br />

May 25 Memor<strong>and</strong>um: To clarify a school district's responsibilities with respect to<br />

national-origin-minority children, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, <strong>and</strong> Welfare,<br />

on May 25, 1970, issued a policy statement stating, in part, that "where inability to speak<br />

<strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the English language excludes national-origin-minority group children<br />

from effective participation in the educational program offered by a school district, the<br />

district must take affirmative steps to rectify the language deficiency in order to open the<br />

instructional program to the students."<br />

NEP: Non-English-proficient.<br />

Newcomer Program: Newcomer pro-grams are separate, relatively self-contained<br />

educational interventions designed to meet the academic <strong>and</strong> transitional needs of newly<br />

arrived immigrants. Typically, students attend these programs before they enter more<br />

traditional interventions (e.g., English language development programs or mainstream<br />

classrooms with supplemental ESL instruction).<br />

Sheltered English Instruction: An instructional approach used to make academic<br />

instruction in English underst<strong>and</strong>able to <strong>EL</strong>L students. In the sheltered classroom, teachers<br />

use physical activities, visual aids, <strong>and</strong> the environment to teach vocabulary for concept<br />

development in mathematics, science, social studies, <strong>and</strong> other subjects.<br />

6 | P a g e

Structured English Immersion Program: The goal of this program is acquisition of<br />

English language skills so that the <strong>EL</strong>L student can succeed in an English-only mainstream<br />

classroom. All instruction in an immersion strategy program is in English. Teachers have<br />

specialized training in meeting the needs of <strong>EL</strong>L students, possessing either a bilingual<br />

education or ESL teaching credential <strong>and</strong>/or training, <strong>and</strong> strong receptive skills in the<br />

students' primary language.<br />

Submersion Program: A submersion program places <strong>EL</strong>L students in a regular Englishonly<br />

program with little or no support services on the theory that they will pick up English<br />

naturally. This program should not be confused with a structured English immersion<br />

program.<br />

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964: Title VI prohibits discrimination on the grounds of<br />

race, color, or national origin by recipients of federal financial assistance. The Title VI<br />

regulatory requirements have been interpreted to prohibit denial of equal access to<br />

education because of a language minority student's limited proficiency in English.<br />

Title VII of the Elementary <strong>and</strong> Secondary Education Act: The Bilingual Education Act,<br />

Title VII of the Elementary <strong>and</strong> Secondary Education Act (ESEA), recognizes the unique<br />

educational disadvantages faced by non-English speaking students. Enacted in 1968, the<br />

Bilingual Education Act established a federal policy to assist educational agencies to serve<br />

students with limited-English-proficiency by authorizing funding to support those efforts. In<br />

addition to providing funds to support services to limited-English-proficient students, Title<br />

VII also supports professional development <strong>and</strong> research activities. Reauthorized in 1994<br />

as part of the Improving America's Schools Act, Title VII was restructured to provide for<br />

an increased state role <strong>and</strong> give priority to applicants seeking to develop bilingual<br />

proficiency. The Improving America's Schools Act also modified eligibility requirements<br />

for services under Title I so that limited-English-proficient students are eligible for services<br />

under that program on the same basis as other students.<br />

Transitional Bilingual Education Program: This program, also known as early-exit<br />

bilingual education, utilizes a student's primary language in instruction. The program<br />

maintains <strong>and</strong> develops skills in the primary language <strong>and</strong> culture while introducing,<br />

maintaining, <strong>and</strong> developing skills in English. The primary purpose of a TBE program is to<br />

facilitate the <strong>EL</strong>L student's transition to an all English instructional program while<br />

receiving academic subject instruction in the native language to the extent necessary.<br />

World Class Instructional Design <strong>and</strong> Assessment (WIDA): Alabama is a part of the<br />

WIDA consortium <strong>and</strong> adopted the WIDA Consortium's <strong>EL</strong>P St<strong>and</strong>ards for Pre-<br />

Kindergarten–Grade 12 encompass:<br />

7 | P a g e<br />

o Social <strong>and</strong> Instructional language<br />

o Language of Language Arts<br />

o Language of Mathematics<br />

o Language of Science<br />

o Language of Social Studies

8 | P a g e<br />

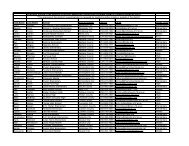

SCHOOL YEAR _____________<br />

<strong>EL</strong>L STUDENT REFERRAL AND PLACEMENT FORM<br />

PART I To be completed by ESL teacher upon notification of potential English Language Learner.<br />

Student ___________________________,_________________________ I.D. # ________________________<br />

Last First<br />

Male Female Date of Birth _____/_____/_______ U.S. Entry Date: _____/_____/______<br />

Shelby County Entry Date: _____/_____/______<br />

Country of Birth: __________________________________ School: _________________________________ Grade: _________<br />

Teacher: ________________________ Home Language: _______________________ ESL Teacher: _______________________<br />

School Student Will Attend for ESL Program Placement: __________________________________________________________<br />

Home Language Survey Completed Yes No Date _____/_____/_______<br />

DAte<br />

PART II To be completed by ESL teacher.<br />

Test Results:<br />

W-APT WIDA/ACCESS Other Assessments:____________________<br />

Speaking ________ Listening _________ DIB<strong>EL</strong>S:________________________________________<br />

Listening _________ Speaking________ ARMT : Reading:__________ Math:__________<br />

Reading __________ Reading___________ SAT 10:______________________________________________<br />

Writing __________ Writing__________ ADAW:_______________________________________________<br />

Composite______________ Comprehension_________ AHSGE: Rdg / Lang. / Math / Sc / SS<br />

Composite___________ (circle sections passed)<br />

Other Evaluative Data:____________________________________<br />

Additional support services are recommended for this student in the area of:<br />

Reading Speech/Pronunciation Writing Math Other ______________________<br />

Comments: ____________________________________________________________________________________________<br />

ESL Teacher Signature ______________________________________ Date _____/_____/_______<br />

PART III Within ten (10) days <strong>EL</strong>L Committee must complete this section.<br />

<strong>EL</strong>L Committee Comments:<br />

Not Highly<br />

PROGRAM ENTRY Recommended Recommended Recommended<br />

(Circle One) 1 2 3 4 5 6<br />

The parental signature below indicates permission for student participation in the English<br />

Language Acquisition program, unless otherwise indicated in the summary section.<br />

Signatures Position Date<br />

______________________________ Parent _________<br />

______________________________ _______________________ _________<br />

______________________________ _______________________ _________<br />

______________________________ ________________________ _________<br />

______________________________ ________________________ _________<br />

_____________________________ ________________________ _________<br />

SUMMARY<br />

<strong>EL</strong>L Committee Recommendations:<br />

(Circle CHOICES)<br />

A. Assign to ESL ________________<br />

hours weekly - Pullout or Inclusion<br />

B. Accommodations (circle appropriate<br />

assessment) ACCESS for <strong>EL</strong>Ls /<br />

DIB<strong>EL</strong>S / SAT-10/ARMT /<br />

ADAW / AHSGE<br />

C. Exempt from semester exams<br />

D. Regular Classroom with<br />

Accommodations<br />

E. Exit Date_______________________<br />

F. FLEP Status: M Yr 1 / M Yr 2 /FLEP<br />

G. Exempt from ESL (NOMPHLOTE)<br />

H. Exempt from ESL (FLEP)<br />

I. Grading _______________________<br />

J. Denial of Participation<br />

K. Other _________________________<br />

______________________________<br />

_______________________________<br />

__________________________________

Place completed form in student's cumulative file <strong>and</strong> <strong>EL</strong>L folders <strong>and</strong> send a copy to Leah Dobbs Black, ESL Program Area Specialist, at SCISC.<br />

9 | P a g e<br />

Accommodations Recommended for Use in Regular Classroom<br />

(To be completed by <strong>EL</strong>L Committee - Circle all that apply)<br />

Student Name ____________________________________Grade<br />

___________________________________<br />

Teacher_________________________________________ School<br />

___________________________________<br />

1. Provide oral tests<br />

2. Give modified tests / alternative assessment<br />

3. Provide highlighted texts, materials, etc.<br />

4. Use visual aids<br />

5. Provide additional instructions<br />

6. Provide outlines<br />

7. Extend time for assignment completion<br />

8. Shorten assignments<br />

9. Utilize assignment notebooks <strong>and</strong> prompts<br />

10. Teach in small group<br />

<strong>11</strong>. Provide repeated reviews <strong>and</strong> drills<br />

12. Allow for peer teaching<br />

13. Reduce paper/pencil tasks<br />

14. Provide manipulatives<br />

15. Seat at the front of the classroom with minimal visual <strong>and</strong><br />

auditory distractions<br />

16. Help student build a card file of vocabulary words<br />

17. Read to the student<br />

18. Encourage students to underline key words or important<br />

facts<br />

19. Allow students an opportunity to express key concepts in<br />

their<br />

own words<br />

20. Permit the use of picture or bilingual dictionaries or<br />

electronic translating devices<br />

21. Provide photocopied notes or outlines<br />

22. Give alternative homework or class work assignments<br />

suitable for the student’s linguistic ability for activities<br />

<strong>and</strong> assessments<br />

23. For textbook or teacher made questions, add page<br />

numbers for<br />

answer location<br />

24. For worksheets with reading assignments, color code question in<br />

conjunction with the reading segment<br />

25. Substitute a h<strong>and</strong>s-on activity or use of different media in<br />

projects for written activity<br />

26. Design bonus work or projects for student that require reduced<br />

sentence or paragraph composition<br />

27. Give student a daily or weekly syllabus of class <strong>and</strong> homework<br />

assignments<br />

28. Consider informal observations of performance <strong>and</strong> classroom<br />

participation as a percentage of the overall evaluation<br />

29. Substitute an alternate reading assignment more appropriate in<br />

length <strong>and</strong> reading level. Where possible, use material<br />

specifically designed for LEP students<br />

30. Disregard misspelled words when grading or underline key<br />

words that were misspelled <strong>and</strong> give the student a chance to<br />

correct them before grading<br />

31. Accept correct answers on tests or worksheets in any written<br />

form such as lists or phrases<br />

32. Incorporate group work into the assessment process<br />

33. Create modified quiz or test in simple language instead of using<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests/shorter tests rather than chapter exams/use<br />

matching columns <strong>and</strong>/or word banks colum<br />

34. Provide an opportunity for the student to take the test<br />

individually with the instructor or provide a reader for the<br />

student during the test<br />

35. Other _________________________________________________<br />

______________________________________________________<br />

______________________________________________________<br />

Additional Accommodations:_______________________________________________________<br />

Comments: _____________________________________________________________________

10 | P a g e<br />

EQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR LIMITED-<br />

ENGLISH PROFICIENT STUDENTS<br />

DISTRICT ASSESSMENT GUIDE 1<br />

This Guide is designed to assist District staff in obtaining a comprehensive overview of the<br />

District’s practices <strong>and</strong> procedures with regard to equal educational opportunities for limited-<br />

English proficient students. Office for Civil Rights (OCR) staff will also review responses to the<br />

Guide as part of its partnership review process. Please circle the answer under each statement that<br />

best responds to the statement, indicating in the Comments if a statement does not apply. Other<br />

comments may also be provided to explain an answer. OCR anticipates that the Guide will be<br />

completed by a team of individuals in each school that OCR schedules to visit. Team members<br />

should be individuals who are most knowledgeable of the District’s policies <strong>and</strong> procedures<br />

relative to the issue being reviewed by OCR. This would include administrators, teachers, <strong>and</strong><br />

paraprofessionals. The schools that OCR will visit will be identified in follow-up telephone<br />

discussions between District officials school is welcome to complete the Guide. The questions in<br />

the Guide should be answered as related to the particular school, not to the District as a whole,<br />

except where specifically noted. A copy of the completed guides are to be returned to OCR, along<br />

with responses to the Profile Data Request, within the timeframe agreed to between OCR <strong>and</strong><br />

District officials.<br />

IDENTIFICATION<br />

Limited-English proficient (LEP) students are students who speak or were influenced by a<br />

language other than English, <strong>and</strong> who are unable to participate meaningfully in the regular<br />

educational program because of their inability to speak <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> English. The first step<br />

most districts follow in determining which students are LEP is to determine which students have a<br />

primary or home language other than English (PHLOTE). PHLOTE students may or may not be<br />

LEP.<br />

1. Are the school’s procedures effective in identifying all students who have a primary or home<br />

language other than English?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

1 This Assessment Guide is to assist school systems to voluntarily comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of<br />

1964 regarding equal educational opportunities for national origin minority students who are limited-English<br />

proficient. Responses to questions also may be used by the Office for Civil Rights in conducting compliance reviews<br />

on this issue. The Guide is part of an OCR program to encourage partnership approaches to civil rights compliance.<br />

School systems are not required to provide data to OCR in this format.

2. Have staff who administer the school’s identification procedures received special training on<br />

these procedures?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

3. Are school staff knowledgeable of the procedures for identifying students who have a primary<br />

or home language other than English?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

4. Do the school’s procedures for initially identifying students who have a primary or home<br />

language other than English determine:<br />

a. Whether the student speaks a language other than English?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

b. Whether the student underst<strong>and</strong>s a language other than English?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

c. Whether the student’s language skills have been influenced by a language other that English<br />

spoken by someone else, such as a gr<strong>and</strong>parent, babysitter or another adult?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

<strong>11</strong> | P a g e

5. Do staff who work directly with parents <strong>and</strong> students in the identification of students who have<br />

a primary or home language other than English speak <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> the appropriate<br />

language(s)?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

6. Is documentation regarding each student’s primary or home language maintained in the<br />

student’s files, including special education files?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

ASSESSMENT<br />

1. Does the school assess the English language proficiency of all students identified as<br />

having a primary or home language other than English?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

2. Are students who have a primary or home language other than English assessed for oral<br />

language, reading <strong>and</strong> writing proficiency, <strong>and</strong> English comprehension?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

_______________________________________________________________<br />

3. If the school conducts proficiency assessments for students who have a primary or<br />

home language other than English, are these assessments:<br />

a. formal assessments (e.g., tests)?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

12 | P a g e

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

b. informal assessments (e.g., teacher interviews, observations)?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

4. Has the district or school trained the staff who administer, evaluate, <strong>and</strong> interpret the<br />

results of the assessment methods used?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

5. Has the school determined a specific level of English-language proficiency at which students<br />

are considered LEP <strong>and</strong> eligible for alternative language services?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:______________________________________________________________________<br />

ALTERNATIVE LANGUAGE PROGRAM (e.g., ESL, Bilingual, Structured Immersion)<br />

1. Are there alternative language programs available for LEP students at each grade level?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

2. Are there substantial delays (e.g., more than 30 days) in placing LEP students into an alternative<br />

language program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

13 | P a g e

3. Are parents involved in making the final determination of whether an LEP student is placed in the<br />

ESL program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

4. Is there coordination between teachers in the school’s alternative program for LEP students <strong>and</strong><br />

teachers n the regular classroom?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

5. If the high school has an alternative program for LEP students, can students in the program earn<br />

credits toward graduation?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

6. Are instructional materials adequate to meet the English language <strong>and</strong> academic needs of LEP<br />

students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

STAFF<br />

1. Has the District or school established special qualifications for teachers who teach in alternative<br />

language programs?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

14 | P a g e

2. Does the school have sufficient numbers of qualified teachers to teach LEP students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

3. If the school does not have sufficient numbers of qualified teachers to teach LEP students, has it<br />

made special efforts to recruit qualified teachers?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

4. Do teacher aides teach in alternative language programs without direct supervision by a qualified<br />

teacher?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

5. Does the District or school provide regular training for teachers <strong>and</strong> aides who teach LEP students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

EXIT CRITERIA<br />

1. Has the school established criteria to determine when an LEP student qualifies to exit an alternative<br />

language program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

15 | P a g e

2. Do the exit criteria ensure that (former) LEP students can speak, read, write, <strong>and</strong> comprehend<br />

English sufficiently well to participate meaningfully in the District’s regular educational program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

3. Are the school’s criteria for exiting LEP students from alternative language programs based on<br />

objective st<strong>and</strong>ards that ensure the student will be able to participate meaningfully in the District’s<br />

regular educational program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

4. Does the school monitor the academic progress of LEP students who have exited the alternative<br />

language program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

__________________________________________________________________<br />

5. Does the school determine whether former LEP students are performing at a level comparable to<br />

their non-LEP peers?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

6. Has the school established procedures for responding to deficient academic performance of former<br />

LEP students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

16 | P a g e

7. Do former LEP students have access to the full school curriculum once they have exited the<br />

alternative language program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

8. Are achievements, honors, awards, or other special recognition rates of former LEP students similar<br />

to those of their peers?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

PROGRAM EVALUATION<br />

1. Does the District or school conduct a formal evaluation of its alternative language program to<br />

determine its effectiveness?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

2. Has the District of school determined that its alternative language program, or parts of it, are not<br />

achieving its goals for LEP students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

3. Does the District or school modify its alternative language program to make it more effective?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

17 | P a g e

4. Has the alternative language program(s) been evaluated by <strong>and</strong> outside source?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

5. Has the District or school developed statistics to compare grade retention, graduation, <strong>and</strong> drop-out<br />

rates of former LEP students to those of their peers?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

NOTICE TO PARENTS<br />

1. Does the school communicate with parents of students with a primary home language other than<br />

English <strong>and</strong> LEP students in a language the parents underst<strong>and</strong>?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

2. Does the school use interpreters or translators to assist in communicating with parents who do not<br />

speak English?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

SEGREGATION<br />

1. Are the quality of facilities <strong>and</strong> services available to LEP students comparable to those available to<br />

non-LEP students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

18 | P a g e

2. Are the quality <strong>and</strong> quantity of instructional materials in the alternative language program<br />

comparable to the instructional materials provided to non-LEP students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

3. Do LEP <strong>and</strong> non-LEP students participate together in classes, activities, <strong>and</strong> assemblies?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

4. Do LEP students have access to the full school curriculum (both required <strong>and</strong> elective courses,<br />

including vocational education) while they are participating in an alternative language program?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

5. Are the counseling services provided to LEP students comparable to those available to non-LEP<br />

students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

SPECIAL OPPORTUNITY PROGRAMS (e.g., Gifted <strong>and</strong> Talented, Advanced Classes)<br />

1. Do LEP students have opportunities for full participation in special opportunity programs?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

19 | P a g e

2. Is the assessment for participation in special opportunity programs similar for LEP <strong>and</strong> non-LEP<br />

students?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

3. Are English-only tests used to assess LEP <strong>and</strong> non-LEP students who may need special education<br />

services?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:________________________________________________________________________<br />

SPECIAL EDUCATION<br />

1. Does the school utilize special procedures for identifying <strong>and</strong> assessing LEP students who many<br />

need special education services?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

2. Do the school’s procedures for identifying <strong>and</strong> assessing LEP students for special education take<br />

into account language <strong>and</strong> cultural differences?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

3. Are persons who administer special education assessment tests to LEP students especially trained<br />

in administering the tests?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

20 | P a g e

4. Has the school assured itself that LEP students are being placed in the special education program<br />

because of actual qualifying condition, <strong>and</strong> not simply because of cultural differences or a lack of<br />

English-language skills?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

5. Does the instructional program for LEP students in special education take into account their<br />

language needs?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

6. Does the school ensure coordination between the regular <strong>and</strong> the special education programs in<br />

meeting the particular needs of LEP students who are in special education?<br />

5 4 3 2 1<br />

Always Never<br />

Comments:_________________________________________________________________________<br />

21 | P a g e

22 | P a g e<br />

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNER IDENTIFICATION,<br />

PLACEMENT, AND ASSESSMENT FLOWCHART<br />

NOMPHLOTE<br />

(students do not<br />

require services)<br />

Struggling <strong>EL</strong><br />

students<br />

may be<br />

rescreened for<br />

ESL services after<br />

an appropriate<br />

time in the<br />

mainstream.<br />

Administer the Home<br />

Language Survey<br />

Language Other<br />

Than English?<br />

YES<br />

Screen with<br />

WAPT<br />

Place in ESL Program<br />

LEP Year 1 (1 st year<br />

in U.S. school)<br />

or LEP Year 2 or<br />

more<br />

EXIT Status<br />

FLEP Monitoring<br />

Year 1<br />

EXIT Status<br />

FLEP Monitoring<br />

Year 2<br />

Language Other<br />

Than English?<br />

NO<br />

General<br />

Education<br />

LEP-W<br />

Waived Title III<br />

Supplemental<br />

Services<br />

FLEP*<br />

ACRONYMS<br />

WAPT: WIDA ACCESS for <strong>EL</strong>Ls Placement Test<br />

NOMPHLOTE: National Origin Minority whose Primary Home Language is Other Than English<br />

LEP-W: Limited English Proficient – Waived Title III Supplementary Services<br />

LEP: Limited English Proficient<br />

FLEP: Former Limited English Proficient<br />

*Students who transfer from a different district or state <strong>and</strong> have already exited from an ESL<br />

program are not NOMPHLOTES; rather, they are Former Limited English Proficient (FLEP).

LOCAL EDUCATION AGENCY REQUIREMENT CHECKLIST FOR<br />

SERVING ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS<br />

The SDE has established Alabama’s requirements for programs <strong>and</strong> services for students who are<br />

English language learners. The requirements, restated <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ed herein, were disseminated to<br />

local education agency superintendents in a letter dated January 21, 1999, from the State<br />

Superintendent of Education.<br />

Each local education agency (LEA) superintendent or designee shall:<br />

1. Develop <strong>and</strong> implement a comprehensive English Language Learners (<strong>EL</strong>L) Plan.<br />

2. Identify <strong>and</strong> provide resources to serve language-minority <strong>and</strong> English language learners.<br />

3. Coordinate programs <strong>and</strong> services to language-minority <strong>and</strong> English language learners <strong>and</strong><br />

their parents at the local school level.<br />

4. Report annually to the State Department of Education (SDE) information concerning the<br />

identification, placement, <strong>and</strong> educational progress of language-minority <strong>and</strong> English<br />

language learners.<br />

5. Report annually to the SDE information relating to the number of students who are English<br />

language learners <strong>and</strong> services rendered.<br />

6. Administer a Home Language Survey to every student at the time of enrollment <strong>and</strong> shall<br />

ensure that surveys are maintained in each individual student’s permanent record.<br />

7. Administer the state-adopted World-Class Instructional Design <strong>and</strong> Assessment (WIDA) -<br />

ACCESS Placement Test (W-APT) language proficiency test to any <strong>and</strong> all students whose<br />

Home Language Survey indicates a language other than English. The W-APT is used for<br />

diagnostic <strong>and</strong> placement purposes. The LEA shall provide appropriate <strong>and</strong> sufficient training<br />

for designated staff who administer this test.<br />

8. Establish program entrance criteria for students who are assessed to have limited English<br />

language proficiency. Non-English language background students who test fluent on the<br />

English language proficiency assessment will not be eligible for English language<br />

development services.<br />

9. Establish <strong>and</strong> implement a system so that every limited-English proficient student has a<br />

student support team (<strong>EL</strong>L Committee) to analyze information gathered from the student<br />

enrollment process <strong>and</strong> English language proficiency assessment. The team shall make<br />

decisions about the types of instructional <strong>and</strong> support services that are needed. At a<br />

minimum, information from the Home Language Survey, the language proficiency test, the<br />

student’s home <strong>and</strong> educational background, <strong>and</strong> the student’s content knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills<br />

as demonstrated in the classroom shall be considered in decisions about programs <strong>and</strong><br />

services to be provided. Although there is nothing to prohibit members from the Building-<br />

23 | P a g e

Based Student Support Teams participating on <strong>EL</strong>L Committees, these committees serve very<br />

different purposes.<br />

10. Ensure that every English language learner has equal access to instructional support,<br />

extracurricular programs, services, <strong>and</strong> activities.<br />

<strong>11</strong>. Develop <strong>and</strong> implement an English language instruction educational program that provides<br />

English language learners productive <strong>and</strong> practical opportunities to develop English<br />

proficiency. In addition, the program should provide support to <strong>EL</strong>Ls in achieving the state’s<br />

content <strong>and</strong> student performance st<strong>and</strong>ards that are expected of all students. The program<br />

must employ scientifically based research (SBR) curricula, instructional materials, <strong>and</strong><br />

methodologies designed for teaching English language learners <strong>and</strong> immigrant children <strong>and</strong><br />

youth.<br />

12. Employ multiple <strong>and</strong> appropriate assessment measures to evaluate the academic progress of<br />

English language learners. Accommodations must be appropriate <strong>and</strong> enable <strong>EL</strong>Ls to<br />

demonstrate what they know <strong>and</strong> are able to do (See Part II, page<br />

27–28, of the <strong>EL</strong>L <strong>Policy</strong> & <strong>Procedures</strong> <strong>Manual</strong> for Grading <strong>and</strong> Retention Guidelines; Part<br />

III, page 32, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Appendix</strong> A, Online Resources, Item 4, for the Special Populations Bulletin<br />

Accommodations Checklist). These assessment measures shall include annual English<br />

language proficiency test scores, as well as a variety of formal <strong>and</strong> informal classroom content<br />

assessments. English language learners must be appropriately accommodated in the content<br />

classroom.<br />

13. Follow program exit criteria established by the State so that a student is not maintained in an<br />

English language instruction educational program longer than is necessary (See page 36 for<br />

State established ESL program exit requirements). No student shall be exited from an English<br />

language instruction educational program, until the program exit criteria have been met.<br />

14. Establish procedures for addressing parent refusal of Title III services. Documentation should<br />

be retained for any eligible student whose parent declines or withdraws participation in<br />

supplemental Title III instruction. Students whose parents/guardians refuse Title III services<br />

are still required by federal law to participate in the annual state-adopted English language<br />

proficiency test.<br />

15. Monitor the English language <strong>and</strong> academic progress of each exited student for a minimum of<br />

two academic years. Students that demonstrate academic or other difficulties while being<br />

monitored shall be provided supplemental support <strong>and</strong> instruction <strong>and</strong>/or be readmitted to an<br />

English language instruction educational program. (See page 37 for ESL Program Exit<br />

Requirements <strong>and</strong> Monitoring of <strong>EL</strong>Ls.)<br />

16. Ensure that English language learners participate in the state’s student assessments in<br />

accordance with current SDE <strong>and</strong> federal policies <strong>and</strong> procedures (See <strong>Appendix</strong> A, Online<br />

Resources, Item 4, Alabama Student Assessment Program Policies <strong>and</strong> <strong>Procedures</strong> for<br />

Students of Special Populations <strong>and</strong> Part III, page 31, of the <strong>EL</strong>L <strong>Policy</strong> & <strong>Procedures</strong><br />

<strong>Manual</strong>).<br />

24 | P a g e

17. Provide ongoing scientifically based research (SBR) professional development for all<br />

personnel responsible for supporting <strong>EL</strong>Ls.<br />

18. Coordinate services, to the extent needed <strong>and</strong> practicable, with those available through local<br />

agencies <strong>and</strong> institutions to maximize adequate <strong>and</strong> efficient delivery of services to English<br />

language learners <strong>and</strong> their parents.<br />

19. Make reasonable, meaningful, <strong>and</strong> sufficient efforts to involve parents/guardians of students<br />

who are English language learners in the student’s overall educational program. Notifications<br />

of LEA <strong>and</strong> school policies <strong>and</strong> procedures, school activities, academic <strong>and</strong> behavioral<br />

expectations, available alternative language <strong>and</strong> support services, <strong>and</strong> student academic<br />

progress shall be made to parents/guardians in a uniform format <strong>and</strong>, to the extent practicable,<br />

in a language that they can underst<strong>and</strong>.<br />

20. Establish, implement, <strong>and</strong> communicate to language-minority parents/guardians, community<br />

groups, <strong>and</strong> other interested parties reasonable, meaningful, <strong>and</strong> sufficient methods for them<br />

to express ideas <strong>and</strong> concerns regarding the provision of services to LEP students.<br />

21. Report annually to its constituents, by means of the Annual LEA Report Card, information,<br />

including student demographics, program participation rates, English proficiency acquisition<br />

rates, <strong>and</strong> student achievement results, as applicable <strong>and</strong> appropriate for English language<br />

instruction educational programs <strong>and</strong> English language learners. ACCESS for <strong>EL</strong>Ls test data<br />

will be reported by school districts on the SDE’s webpage.<br />

22. Submit to the SDE, upon request, data <strong>and</strong> other information to reflect participation <strong>and</strong><br />

progress of <strong>EL</strong>Ls in all areas of the English language instruction educational program.<br />

Each LEA may consider joint or consortium agreements between <strong>and</strong> among LEAs to provide<br />

academic <strong>and</strong> support programs to English language learners. The consortium members will<br />

designate a lead to the consortium. Therefore, Annual Measurable Achievement Objective<br />

(AMAO) results will be derived from a composite of all students in the consortium, which will<br />

determine AMAO status for all consortium member LEAs. (See Part III of the <strong>EL</strong>L <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Procedures</strong> <strong>Manual</strong>, pages 31–37, AMAOs overview).<br />

25 | P a g e

<strong>Policy</strong> Update on Schools' Obligations Toward National Origin Minority Students With Limited-English<br />

Proficiency<br />

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION<br />

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20202<br />

MEMORANDUM<br />

SEP 27 1991<br />

TO: OCR Senior Staff<br />

FROM: Michael L. Williams, Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights<br />

SUBJECT: <strong>Policy</strong> Update on Schools' Obligations Toward National Origin Minority Students With Limited-English Proficiency (LEP students)<br />

This policy update is primarily designed for use in conducting Lau [1] compliance reviews -- that is, compliance reviews designed to determine<br />

whether schools are complying with their obligation under the regulation implementing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to provide any<br />

alternative language programs necessary to ensure that national origin minority students with limited-English proficiency (LEP students) have<br />

meaningful access to the schools' programs. The policy update adheres to OCR's past determination that Title VI does not m<strong>and</strong>ate any particular<br />

program of instruction for LEP students. In determining whether the recipient is operating a program for LEP students that meets Title VI<br />

requirements, OCR will consider whether: (1) the program the recipient chooses is recognized as sound by some experts in the field or is considered<br />

a legitimate experimental strategy; (2) the programs <strong>and</strong> practices used by the school system are reasonably calculated to implement effectively the<br />

educational theory adopted by the school; <strong>and</strong> (3) the program succeeds, after a legitimate trial, in producing results indicating that students'<br />

language barriers are actually being overcome. The policy update also discusses some difficult issues that frequently arise in Lau investigations. An<br />

appendix to the policy discusses the continuing validity of OCR's use of the Castaneda [2] st<strong>and</strong>ard to determine compliance with the Title VI<br />

regulation.<br />

This document should be read in conjunction with the December 3, 1985, guidance document entitled, "The Office for Civil Rights' Title VI<br />

Language Minority Compliance <strong>Procedures</strong>," <strong>and</strong> the May 1970 memor<strong>and</strong>um to school districts entitled, "Identification of Discrimination <strong>and</strong><br />

Denial of Services on the Basis of National origin," 35 Fed. Reg. <strong>11</strong>595 (May 1970 Memor<strong>and</strong>um). It does not supersede either document. [3] These<br />

two documents are attached for your convenience.<br />

Part I of the policy update provides additional guidance for applying the May 1970 <strong>and</strong> December 1985 memor<strong>and</strong>a that describe OCR's Title VI<br />

Lau policy. In Part I, more specific st<strong>and</strong>ards are enunciated for staffing requirements, exit criteria <strong>and</strong> program evaluation. <strong>Policy</strong> issues related to<br />

special education programs, gifted/talented programs, <strong>and</strong> other special programs are also discussed. Part II of the policy update describes OCR's<br />

policy with regard to segregation of LEP students.<br />

The appendix to this policy update discusses the use of the Castaneda st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong> the way in which Federal courts have viewed the relationship<br />

between Title VI <strong>and</strong> the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974.<br />

With the possible exception of Castaneda, which provides a common sense analytical framework for analyzing a district's program for LEP students<br />

that has been adopted by OCR, <strong>and</strong> Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, which applied the Castaneda principles to the Denver Public Schools, most court<br />

decisions in this area stop short of providing OCR <strong>and</strong> recipient institutions with specific guidance. The policy st<strong>and</strong>ards enunciated in this<br />

document attempt to combine the most definitive court guidance with OCR's practical legal <strong>and</strong> policy experience in the field. In that regard, the<br />

issues discussed herein, <strong>and</strong> the policy decisions reached, reflect a careful <strong>and</strong> thorough examination of Lau case investigations carried out by OCR's<br />

regional offices over the past few years, comments from the regional offices on a draft version of the policy, <strong>and</strong> lengthy discussions on the issues<br />

with some of OCR's most experienced investigators. Specific recommendations from participants at the Investigative Strategies Workshop have<br />

also been considered <strong>and</strong> incorporated where appropriate.<br />

I. Additional guidance for applying the May 1970 <strong>and</strong> December 1985 memor<strong>and</strong>a.<br />

The December 1985 memor<strong>and</strong>um listed two areas to be examined in determining whether a recipient was in compliance with Title VI: (1) the need<br />

for an alternative language program for LEP students; <strong>and</strong> (2) the adequacy of the program chosen by the recipient. Issues related to the adequacy of<br />

the program chosen by the recipient will be discussed first, as they arise more often in Lau investigations. Of course, the determination of whether a<br />

recipient is in violation of Title VI will require a finding that language minority students are in need of an alternative language program in order to<br />

participate effectively in the recipient's educational program.<br />

A. Adequacy of Program<br />

This section of the memor<strong>and</strong>um provides additional guidance for applying the three-pronged Castaneda approach as a st<strong>and</strong>ard for determining the<br />

adequacy of a recipient's efforts to provide equal educational opportunities for LEP students.<br />

26 | P a g e

1. Soundness of educational approach<br />

Castaneda requires districts to use educational theories that are recognized as sound by some experts in the field, or at least theories that are<br />

recognized as legitimate educational strategies. 648 F. 2d at 1009. Some approaches that fall under this category include transitional bilingual<br />

education, bilingual/bicultural education, structured immersion, developmental bilingual education, <strong>and</strong> English as a Second Language (ESL). A<br />

district that is using any of these approaches has complied with the first requirement of Castaneda. If a district is using a different approach, it is in<br />

compliance with Castaneda if it can show that the approach is considered sound by some experts in the field or that it is considered a legitimate<br />

experimental strategy.<br />

2. Proper Implementation<br />

Castaneda requires that "the programs <strong>and</strong> practices actually used by a school system [be] reasonably calculated to implement effectively the<br />

educational theory adopted by the school." 648 F. 2d at 1010. Some problematic implementation issues have included staffing requirements for<br />

programs, exit criteria, <strong>and</strong> access to programs such as gifted/talented programs. These issues are discussed below.<br />

Staffing requirements<br />

Districts have an obligation to provide the staff necessary to implement their chosen program properly within a<br />

reasonable period of time. Many states <strong>and</strong> school districts have established formal qualifications for teachers<br />

working in a program for limited-English-proficient students. When formal qualifications have been established, <strong>and</strong><br />

when a district generally requires its teachers in other subjects to meet formal requirements, a recipient must either<br />

hire formally qualified teachers for LEP students or require that teachers already on staff work toward attaining those<br />

formal qualifications. See Castaneda, 648 F. 2d at 1013. A recipient may not in effect relegate LEP students to<br />

second-class status by indefinitely allowing teachers without formal qualifications to teach them while requiring<br />

teachers of non-LEP students to meet formal qualifications. See 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(ii). [4]<br />

Whether the district's teachers have met any applicable qualifications established by the state or district does not conclusively show that they are<br />

qualified to teach in an alternative language program. Some states have no requirements beyond requiring that a teacher generally be certified, <strong>and</strong><br />

some states have established requirements that are not rigorous enough to ensure that their teachers have the skills necessary to carry out the<br />

district's chosen educational program. [5] Discussed below are some minimum qualifications for teachers in alternative language programs.<br />

If a recipient selects a bilingual program for its LEP students, at a minimum, teachers of bilingual classes should be able to speak, read, <strong>and</strong> write<br />

both languages, <strong>and</strong> should have received adequate instruction in the methods of bilingual education. In addition, the recipient should be able to<br />

show that it has determined that its bilingual teachers have these skills. See Keyes, 576 F. Supp. at 1516-17 (criticizing district for designating<br />

teachers as bilingual based on an oral interview <strong>and</strong> for not using st<strong>and</strong>ardized tests to determine whether bilingual teachers could speak <strong>and</strong> write<br />

both languages); cf. Castaneda, 648 F. 2d at 1013 ("A bilingual education program, however sound in theory, is clearly unlikely to have a significant<br />

impact on the language barriers confronting limited English speaking school children, if the teachers charged with the day-to-day responsibility for<br />

educating these children are termed 'qualified' despite the fact that they operate in the classroom under their own unremedied language disability").<br />

In addition, bilingual teachers should be fully qualified to teach their subject.<br />

If a recipient uses a method other than bilingual education (such as ESL or structured immersion), the recipient should have ascertained that teachers<br />

who use those methods have been adequately trained in them. This training can take the form of in?service training, formal college coursework, or a<br />

combination of the two. In addition, as with bilingual teachers, a recipient should be able to show that it has determined that its teachers have<br />

mastered the skills necessary to teach effectively in a program for LEP students. In making this determination, the recipient should use validated<br />

evaluative instruments -- that is, tests that have been shown to accurately measure the skills in question. The recipient should also have the teacher's<br />

classroom performance evaluated by someone familiar with the method being used.<br />

ESL teachers need not be bilingual if the evidence shows that they can teach effectively without bilingual skills. Compare Teresa P., 724 F. Supp. at<br />

709 (finding that LEP students can be taught English effectively by monolingual teachers), with Keyes, 576 F. Supp. at 1517 ("The record shows<br />

that in the secondary schools there are designated ESL teachers who have no second language capability. There is no basis for assuming that the<br />

policy objectives of the [transitional bilingual education] program are being met in such schools").<br />

To the extent that the recipient's chosen educational theory requires native language support, <strong>and</strong> if the program relies on bilingual aides to provide<br />

such support, the recipient should be able to demonstrate that it has determined that its aides have the appropriate level of skill in speaking, reading,<br />

<strong>and</strong> writing both languages. [6] In addition, the bilingual aides should be working under the direct supervision of certificated classroom teachers.<br />

Students should not be getting instruction from aides rather than teachers. 34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(1)(ii); see Castaneda, 648 F.2d at 1013 ("The use of<br />

Spanish speaking aides may be an appropriate interim measure, but such aides cannot. . .take the place of qualified bilingual teachers").<br />

Recipients frequently assert that their teachers are unqualified because qualified teachers are not available. If a recipient has shown that it has<br />

unsuccessfully tried to hire qualified teachers, it must provide adequate training to teachers already on staff to comply with the Title VI regulation.<br />

See Castaneda, 648 F. 2d at 1013. Such training must take place as soon as possible. For example, recipients sometimes require teachers to work<br />

toward obtaining a credential as a condition of employment in a program for limited-English-proficient students. This requirement is not, in itself,<br />

sufficient to meet the recipient's obligations under the Title VI regulation. To ensure that LEP students have access to the recipient's programs while<br />

teachers are completing their formal training, the recipient must ensure that those teachers receive sufficient interim training to enable them to<br />

function adequately in the classroom, as well as any assistance from bilingual aides that may be necessary to carry out the recipient's interim<br />

program.<br />

27 | P a g e

Exit Criteria for Language Minority LEP Students<br />

Once students have been placed in an alternative language program, they must be provided with services until they<br />

are proficient enough in English to participate meaningfully in the regular educational program. Some factors to<br />

examine in determining whether formerly LEP students are able to participate meaningfully in the regular educational<br />

program include: (1) whether they are able to keep up with their non-LEP peers in the regular educational program;<br />

(2) whether they are able to participate successfully in essentially all aspects of the school's curriculum without the<br />

use of simplified English materials; <strong>and</strong> (3) whether their retention in-grade <strong>and</strong> dropout rates are similar to those of<br />

their non-LEP peers.<br />