comment sketchy eyewitness-identification ... - UW Law School

comment sketchy eyewitness-identification ... - UW Law School

comment sketchy eyewitness-identification ... - UW Law School

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

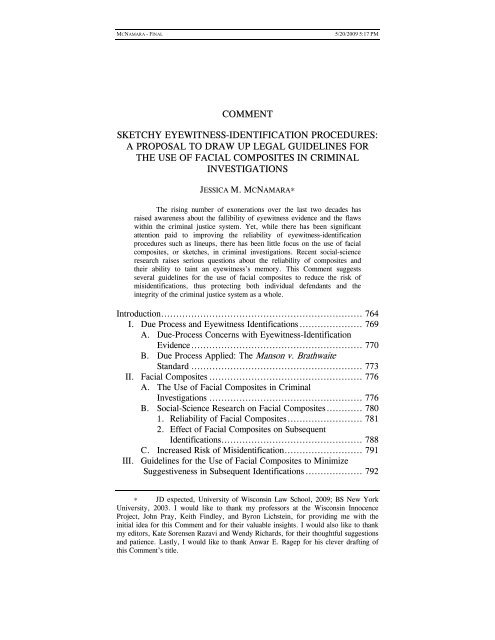

COMMENT<br />

SKETCHY EYEWITNESS-IDENTIFICATION PROCEDURES:<br />

A PROPOSAL TO DRAW UP LEGAL GUIDELINES FOR<br />

THE USE OF FACIAL COMPOSITES IN CRIMINAL<br />

INVESTIGATIONS<br />

JESSICA M. MCNAMARA∗<br />

The rising number of exonerations over the last two decades has<br />

raised awareness about the fallibility of <strong>eyewitness</strong> evidence and the flaws<br />

within the criminal justice system. Yet, while there has been significant<br />

attention paid to improving the reliability of <strong>eyewitness</strong>-<strong>identification</strong><br />

procedures such as lineups, there has been little focus on the use of facial<br />

composites, or sketches, in criminal investigations. Recent social-science<br />

research raises serious questions about the reliability of composites and<br />

their ability to taint an <strong>eyewitness</strong>’s memory. This Comment suggests<br />

several guidelines for the use of facial composites to reduce the risk of<br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>s, thus protecting both individual defendants and the<br />

integrity of the criminal justice system as a whole.<br />

Introduction ................................................................... 764<br />

I. Due Process and Eyewitness Identifications ..................... 769<br />

A. Due-Process Concerns with Eyewitness-Identification<br />

Evidence ......................................................... 770<br />

B. Due Process Applied: The Manson v. Brathwaite<br />

Standard ......................................................... 773<br />

II. Facial Composites ................................................... 776<br />

A. The Use of Facial Composites in Criminal<br />

Investigations ................................................... 776<br />

B. Social-Science Research on Facial Composites ............ 780<br />

1. Reliability of Facial Composites ......................... 781<br />

2. Effect of Facial Composites on Subsequent<br />

Identifications ............................................... 788<br />

C. Increased Risk of Mis<strong>identification</strong> .......................... 791<br />

III. Guidelines for the Use of Facial Composites to Minimize<br />

Suggestiveness in Subsequent Identifications ................... 792<br />

∗ JD expected, University of Wisconsin <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong>, 2009; BS New York<br />

University, 2003. I would like to thank my professors at the Wisconsin Innocence<br />

Project, John Pray, Keith Findley, and Byron Lichstein, for providing me with the<br />

initial idea for this Comment and for their valuable insights. I would also like to thank<br />

my editors, Kate Sorensen Razavi and Wendy Richards, for their thoughtful suggestions<br />

and patience. Lastly, I would like to thank Anwar E. Ragep for his clever drafting of<br />

this Comment’s title.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

764 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

A. Tool of Last Resort ............................................ 793<br />

B. Separating Identification Procedures Among Witnesses .. 795<br />

C. Reasonable-Suspicion Requirement.......................... 795<br />

D. Implementation of the Guidelines ............................ 797<br />

Conclusion .................................................................... 798<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

In March of 1985, Kirk Bloodsworth, a former U.S. Marine with<br />

no prior criminal record, was convicted of first-degree intentional<br />

homicide, sexual assault, and rape. 1 The victim, a nine-year-old girl,<br />

had been raped, strangled, and beaten with a rock. 2 The evidence<br />

consisted of a shoe print from the crime scene 3 and five separate<br />

<strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s. 4 Bloodsworth also had a weak alibi and made<br />

several incriminating statements. 5 Despite his insistence that he was<br />

innocent, the jury found him guilty after a short deliberation, and<br />

Bloodsworth was sentenced to death. 6<br />

Almost nine years later, in 1993, Bloodsworth became the first<br />

person exonerated from death row by DNA evidence. 7 He was released<br />

from prison after DNA testing on a small amount of semen left on the<br />

victim’s underpants excluded him as a source. 8 Ten years later, in<br />

2003, the DNA profile of the real culprit was entered into a national<br />

DNA database and matched to a man named Kimberly Shay Ruffner,<br />

who was already incarcerated for an unrelated attempted rape and<br />

1. Bloodsworth v. State, 543 A.2d 382, 384 n.1, 389 (Md. Ct. Spec. App.<br />

1988); TIM JUNKIN, BLOODSWORTH: THE TRUE STORY OF THE FIRST DEATH ROW<br />

INMATE EXONERATED BY DNA 62, 76 (2004).<br />

2. JUNKIN, supra note 1, at 31, 38.<br />

3. Although the shoe print had “limited design similarities” with a purported<br />

pair of Bloodsworth’s shoes seized from Bloodsworth’s cousin’s house, it was later<br />

discovered that the shoes were two-and-a-half sizes smaller than Bloodsworth’s shoe<br />

size. Id. at 120–21.<br />

4. Id. at 136–38.<br />

5. Id. at 70, 78–88. For example, Bloodsworth had told several people only<br />

days after the murder that he had done a “bad thing.” Id. at 70, 79. At trial, he testified<br />

he was referring to his broken promise to buy his wife a taco salad. Id. at 145.<br />

6. Id. at 156, 166.<br />

7. Id. at 258, 269–70. DNA typing compares patterns in genetic profiles<br />

from biological materials such as semen and blood. See JOHN M. BUTLER, FORENSIC<br />

DNA TYPING 2–8, 33 (2d ed. 2005). Generally, if a known sample (such as DNA of a<br />

suspect) does not match a questioned sample (such as DNA found at a crime scene), the<br />

samples originated from different sources. See id. at 7.<br />

8. JUNKIN, supra note 1, at 22.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 765<br />

murder. 9 Bloodsworth was fortunate to have had his death sentence<br />

reduced to two consecutive life sentences, but if DNA testing had not<br />

been available, Bloodsworth would likely still be in prison today for a<br />

crime he did not commit. 10<br />

Bloodsworth became a suspect only after an anonymous caller<br />

informed police that Bloodsworth looked very similar to a sketch of the<br />

culprit that had been distributed to the public. 11 The culprit was<br />

described as 6’5,’’ skinny, with curly blonde hair and a bushy<br />

mustache. 12 Bloodsworth resembled the sketch, and despite the fact that<br />

he was 6’0’’ tall with red hair and a bulky build, police placed him in a<br />

lineup where he was identified by five <strong>eyewitness</strong>es. 13 Ruffner, the real<br />

culprit, did not resemble the sketch. 14<br />

Bloodsworth’s story is not unique. Many other people who have<br />

been wrongfully convicted initially became suspects solely because of<br />

their resemblance to a facial composite. 15 This resemblance led law<br />

9. James Dao, In Same Case, DNA Clears Convict and Finds Suspect, N.Y.<br />

TIMES, Sept. 5, 2003, at A7. Bloodsworth and Ruffner had actually been acquaintances<br />

in prison; as the prison librarian, Bloodsworth often delivered books to Ruffner’s cell.<br />

Id. A DNA match is not absolute proof of guilt, due to human error in the testing<br />

process, the probability of a “match,” and the relationship of the biological material to<br />

the commission of the crime. See generally MAX M. HOUCK & JAY A. SIEGEL,<br />

FUNDAMENTALS OF FORENSIC SCIENCE 284–87 (2006) (describing the interpretation of<br />

DNA-typing results and comparison of DNA samples). For example, a match to DNA<br />

from saliva on a cigarette butt discarded next to a homicide victim may provide<br />

suspicion that the person was involved in the crime, but does not, in itself, prove guilt.<br />

In child-sexual-assault cases, however, a match to DNA from semen taken from inside<br />

the child is generally regarded as the most conclusive evidence available. There are<br />

few, if any, plausible explanations for why the semen would be in the child unless an<br />

assault had occurred. Therefore, the DNA match between Ruffner and the semen on the<br />

victim’s underpants is the most realistically conclusive proof possible of his guilt and<br />

Bloodsworth’s innocence.<br />

10. In 1986, a year after his original conviction, an appellate court granted<br />

Bloodsworth a new trial. JUNKIN, supra note 1, at 193–94. He was convicted again, but<br />

this time sentenced to two consecutive life sentences instead of death. Id. at 220, 227.<br />

At that time, absent other compelling new evidence of his innocence, he had exhausted<br />

all of his appeals. Id. at 4, 8–11. DNA testing only later provided the compelling<br />

evidence necessary for his exoneration.<br />

11. Id. at 49, 75.<br />

12. Id. at 44–46.<br />

13. Id. at 66, 91, 98–101. See infra Part I.A for a discussion of possible<br />

reasons why the <strong>eyewitness</strong>es made erroneous <strong>identification</strong>s.<br />

14. See JUNKIN, supra note 1, at 46, 102; Gary L. Wells & Lisa E. Hasel,<br />

Facial Composite Production by Eyewitnesses, 16 CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOL.<br />

SCI. 6, 6 (2007).<br />

15. Facial composite is a general term that refers to an image of a culprit<br />

produced by law enforcement with the help of <strong>eyewitness</strong>es. There are several methods<br />

of producing the images, leading to a variety of terms to describe them, including<br />

sketch, composite sketch, police composite, forensic sketch, etc.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

766 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

enforcement to place them in a lineup 16 where they were misidentified<br />

by <strong>eyewitness</strong>es, and ultimately convicted of crimes they did not<br />

commit. 17<br />

Because of the potential for mistaken <strong>identification</strong>s based on<br />

unreliable <strong>eyewitness</strong> evidence, and the considerable weight usually<br />

given by juries to <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s when identity is at issue,<br />

courts have realized the need to lend protection to defendants<br />

confronted with <strong>eyewitness</strong> evidence. In United States v. Wade, 18 the<br />

Supreme Court of the United States first expressed concern about<br />

16. The term lineup can refer to a live lineup or a photographic lineup, also<br />

known as a photo array or photo spread.<br />

17. The only data on exonerees who initially became suspects because of a<br />

resemblance to a facial composite exists anecdotally, although there are at least twentythree.<br />

See, e.g., TARYN SIMON, INNOCENCE PROJECT, THE INNOCENTS 24, 42, 56, 80<br />

(2003) (detailing the story of Ronald Cotton, Edward Honaker, Neil Miller, James<br />

O’Donnell); SURVIVING JUSTICE: AMERICA’S WRONGFULLY CONVICTED AND<br />

EXONERATED 115–46, 365–93 (Lola Vollen & Dave Eggers eds., 2005) (detailing the<br />

story of James Newsome, Peter Rose); Keith A. Findley & Michael S. Scott, The<br />

Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision in Criminal Cases, 2006 WIS. L. REV. 291, 299–<br />

304 (detailing the story of Steven Avery); Tammy Fonce-Olivas, Juror Says Scientist<br />

Influenced Moon Case Rape Verdict, EL PASO TIMES (Tex.), Dec. 23, 2004, at 1A<br />

(detailing the story of Brandon Moon); Innocenceproject.org, Know the Cases: Browse<br />

the Profiles, http://www.innocenceproject.org/know/Browse-Profiles.php (last visited<br />

Mar. 16, 2009) (detailing the story of Antonio Beaver, Jimmy Ray Bromgard, Ronnie<br />

Bullock, Dean Cage, Bruce Godschalk, Donald Wayne Good, Anthony Hicks, Marcus<br />

Lyons, Jerry Miller, Marlon Pendleton, Lafonso Rollins, John Jerome White, Willie<br />

Williams, and Kenneth Wyniemko); <strong>Law</strong>.northwestern.edu, Meet the Exonerated:<br />

Michael Evans, http://www.law.northwestern.edu/wrongfulconvictions/exonerations/<br />

ilEvansTerrySummary.html (last visited Mar. 16, 2009) (Paul Terry). At least eleven<br />

others may have initially become suspects for independent reasons, but facial<br />

composites played a significant role in their wrongful convictions. See, e.g., Brief of<br />

Petitioner at 12–13, Arizona v. Youngblood, No. 86-1904 (U.S. Oct., 1986) (detailing<br />

the story of Larry Youngblood); STANLEY COHEN, THE WRONG MEN: AMERICA’S<br />

EPIDEMIC OF WRONGFUL DEATH ROW CONVICTIONS 3–11, 20–23 (2003) (detailing the<br />

story of Gary Dotson, Frank Lee Smith); KAREN T. TAYLOR, FORENSIC ART AND<br />

ILLUSTRATION 31 (2001) (detailing the story of Neil Ferber); Michael Hall, Why Can’t<br />

Steven Phillips Get a DNA Test?, TEX. MONTHLY, Jan. 2006, at 128 (detailing the<br />

story of Steven Phillips); William C. Lhotka, Wrongly Convicted Man Is Set Free, ST.<br />

LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, July 20, 2006, at A1 (detailing the story of Johnny Briscoe);<br />

Shelley Smithson, The Price of Innocence: Larry Johnson Wants Big Bucks for a Crime<br />

He Never Committed, RIVERFRONT TIMES (St. Louis), Aug. 18, 2004 (detailing the<br />

story of Larry Johnson); Innocenceproject.org, supra (detailing the story of Leonard<br />

Callace, Carlos Lavernia); Ip-no.org, Innocence Project New Orleans, Cases: Allen<br />

Coco, http://www.ip-no.org/AllenCoco.htm (last visited Mar. 16, 2009) (detailing the<br />

story of Allen Coco); AFTER INNOCENCE (Showtime Independent Films 2005) (detailing<br />

the story of Wilton Dedge). All of the above were exonerated with DNA evidence (with<br />

the exceptions of James Newsome who was exonerated by fingerprint evidence, and<br />

Neil Ferber who was exonerated after a jailhouse snitch recanted), and in several cases<br />

the real culprits were identified.<br />

18. 388 U.S. 218 (1967).

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 767<br />

suggestive <strong>identification</strong> procedures. 19 A decade later, constitutional<br />

protections based on fairness as required by the Due Process Clause<br />

were established in Manson v. Brathwaite, 20 providing for the exclusion<br />

of <strong>eyewitness</strong> evidence that is so suggestive as to “g[i]ve rise to a very<br />

substantial likelihood of irreparable mis<strong>identification</strong>.” 21 Recognizing<br />

the danger of keeping reliable evidence from the jury, and thereby<br />

allowing a guilty person to go free, the Court limited the holding by<br />

concluding that, despite the suggestiveness of any procedure,<br />

“reliability is the linchpin in determining the admissibility of<br />

<strong>identification</strong> testimony.” 22<br />

The Brathwaite protections are not only limited by the reliability<br />

determination, but also by the narrow focus on the procedures used<br />

once a suspect has been identified, such as lineups. 23 The procedures<br />

19. Id. at 228–29.<br />

20. 432 U.S. 98 (1977).<br />

21. Id. at 107, 113. It is unclear whether the proper standard in Brathwaite is<br />

unnecessarily suggestive, impermissibly suggestive, or whether there is a distinction<br />

between the two. See id. at 99, 104, 107, 110, 112–13. Throughout the opinion, the<br />

Court uses both terms when referring to the suggestiveness of <strong>eyewitness</strong>-<strong>identification</strong><br />

procedures. Id. Lower courts have largely either failed to distinguish the two terms or<br />

have treated them interchangeably. See, e.g., United States v. Bautista, 23 F.3d 726,<br />

729–30 (2d Cir. 1994) (stating that the terms unnecessary and impermissibly are<br />

synonymous in the context of suggestive <strong>eyewitness</strong>-<strong>identification</strong> procedures); United<br />

States v. Stevens, 935 F.2d 1380, 1389 (3d Cir. 1991) (stating that the standard is<br />

either unnecessarily or impermissibly suggestive, yet expressing preference for<br />

unnecessarily); Green v. Loggins, 614 F.2d 219, 223 (9th Cir. 1980) (stating that the<br />

standard in Brathwaite is either unnecessarily or impermissibly suggestive); United<br />

States v. Patterson, No. 00-10226-GAO, 2001 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 18232, *6–7 (D.<br />

Mass. Sept. 10, 2001) (reasoning that if a procedure is unnecessarily suggestive, it is<br />

impermissible); Hanks v. Jackson, 123 F. Supp. 2d 1061, 1071 (E.D. Mich. 2000)<br />

(treating unnecessarily and impermissibly suggestive as equally unconstitutional). The<br />

Supreme Court has used both unnecessarily, Moore v. Illinois, 434 U.S. 220, 227 n.3<br />

(1977), and impermissibly, Watkins v. Sowders, 449 U.S. 341, 344 (1981), when<br />

discussing admissibility of <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s. The Wisconsin Supreme Court,<br />

relying largely on a law-review article, posited that following Brathwaite, the test for<br />

<strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s “evolved from an inquiry into unnecessary suggestiveness to<br />

an inquiry of impermissible suggestiveness,” and that “[s]ubstitution of the word<br />

‘permissible’ for ‘unnecessarily’ creates the impression that what may be ‘unnecessary’<br />

could still be ‘permissible.’” State v. Dubose, 2000 WI 126, 22, 31, 285 Wis. 2d<br />

143, 699 N.W.2d 582 (quoting in part David E. Paseltiner, Twenty-Years of<br />

Diminishing Protection: A Proposal to Return to the Wade Trilogy’s Standards, 15<br />

HOFSTRA L. REV. 583, 589 (1987)). Regardless of any potential distinction, this<br />

Comment concludes that the Brathwaite standard should apply to the use of facial<br />

composites in criminal investigations because of the likelihood of mis<strong>identification</strong><br />

stemming from their use.<br />

22. Brathwaite, 432 U.S. at 114. The Court went on to list several factors to<br />

determine the reliability of <strong>identification</strong>s to be weighed against the suggestiveness of<br />

the <strong>identification</strong>. See infra note 69.<br />

23. See supra Part II.C.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

768 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

that lead to choosing suspects, such as the production of a facial<br />

composite, have been given less attention. 24 This is partly a result of<br />

focus on lineups as the main event of an <strong>identification</strong>, and partly<br />

because protections for suspects before an <strong>identification</strong> are minimal. 25<br />

Facial composites have been a long-time tool of law enforcement<br />

to create a likeness of an unknown culprit. 26 Eyewitnesses choose from<br />

hundreds and sometimes thousands of different facial features (eyes,<br />

noses, lips, etc.) which are copied or assembled by a forensic artist or<br />

computer to create a composite image that is distributed to the public. 27<br />

<strong>Law</strong> enforcement rely on tips based on composites to generate leads for<br />

suspects, such as the anonymous tip that led to the arrest of<br />

Bloodsworth. 28 Once law enforcement has identified a suspect who<br />

resembles a composite, there is risk that a process described as “tunnel<br />

vision” will begin, in which police tend to focus on inculpatory<br />

evidence and ignore exculpatory evidence in a quest to successfully<br />

solve a case. 29<br />

A growing body of social-science research now shows numerous<br />

problems with the effectiveness and reliability of facial composites.<br />

Questions about the reliability of <strong>identification</strong>s stemming from a facial<br />

composite are particularly relevant, given the significant number of<br />

wrongful convictions resulting from mistaken <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s<br />

that began with a facial composite. 30 Given the inherent risk of being<br />

placed in a lineup, even if all recommended procedures are followed,<br />

the problems inherent with facial composites still create an unnecessary<br />

and impermissible risk of mis<strong>identification</strong>. Applying protections to<br />

only the second half of <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s, namely the<br />

24. See generally Andrew Roberts, Towards a Broader Perspective on the<br />

Problem of Mistaken Identification: Police Decision-Making and Identification<br />

Procedures, in 9 LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY: CURRENT LEGAL ISSUES 2006, at 182 (Belinda<br />

Brooks-Gordon & Michael Freeman eds., 2006) (advocating for less focus on<br />

improving <strong>identification</strong> procedures themselves, and more focus on the decision-making<br />

process of whether to conduct <strong>identification</strong> procedures in the first place).<br />

25. See Brathwaite, 432 U.S. at 110.<br />

26. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 11–42.<br />

27. Id. at 223–32 (describing the FBI Facial Identification Catalog used by<br />

forensic artists to create hand-drawn composites); Margaret Bull Kovera et al.,<br />

Identification of Computer-Generated Facial Composites, 82 J. APPLIED PSYCHOL. 235,<br />

235 (1997) (describing facial-composite-production systems used by artists or officers<br />

to create a composite from preprinted images); Robin Brown, Delaware Police Put Best<br />

Face Forward, NEWS J. (Wilmington, Del.), Nov. 20, 2007, at A1 (describing FACES,<br />

a computer program that creates composites from thousands of facial images).<br />

28. JUNKIN, supra note 1, at 75–77.<br />

29. Findley & Scott, supra note 17, at 292.<br />

30. See supra note 17 and accompanying text.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 769<br />

<strong>identification</strong> of a suspect in a lineup, does not provide enough<br />

protection to suspects.<br />

This Comment will focus on due-process requirements as they<br />

apply to the process of using facial composites in the investigation and<br />

<strong>identification</strong> of suspects. Part I of this Comment provides an overview<br />

of due-process concerns with <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s and the<br />

admissibility standard set forth in Manson v. Brathwaite. Part II<br />

reviews the current use of facial composites in criminal investigations,<br />

along with social-science research on the reliability of facial composites<br />

and their effect on subsequent <strong>identification</strong>s. Part II also explains how<br />

the use of facial composites increases the risk of mistaken <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

<strong>identification</strong>s, and argues that facial composites should be subject to<br />

the Brathwaite standard. Part III proposes new guidelines to decrease<br />

the suggestiveness of facial composites in criminal investigations to<br />

comply with the Brathwaite standard and reduce the risk of<br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>s.<br />

This Comment concludes that the current use of facial composites<br />

in criminal investigations is unnecessarily and impermissibly<br />

suggestive, and the admission of subsequent <strong>identification</strong>s as evidence<br />

violates the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth<br />

Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. To ensure fairness and to avoid<br />

mistaken <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s, courts should expand the<br />

application of the Manson v. Brathwaite standard to the use of facial<br />

composites. This does not mean that <strong>identification</strong>s resulting from facial<br />

composites should be inadmissible per se. Rather, the procedures<br />

involving facial composites should be scrutinized in the same way as<br />

other <strong>identification</strong> procedures to determine whether they are so<br />

suggestive as to give rise to a substantial likelihood of irreparable<br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>.<br />

I. DUE PROCESS AND EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATIONS<br />

The Due Process Clauses in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments<br />

to the Constitution require that defendants be afforded a trial that<br />

comports with “fundamental conceptions of justice which lie at the base<br />

of our civil and political institutions.” 31 This notion of fairness demands<br />

that defendants be protected against evidence, such as <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

<strong>identification</strong>s, that may jeopardize a fair trial. Recognizing these<br />

dangers, the Supreme Court established protections against unfair<br />

<strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s in Manson v. Brathwaite.<br />

31. Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 103, 112 (1935).

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

770 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

A. Due-Process Concerns with Eyewitness-Identification Evidence<br />

Since 1989, over two hundred people have been exonerated by<br />

DNA evidence in the United States. 32 The number of exonerations<br />

climbs even higher when considering other types of evidence. 33 The<br />

single greatest cause of wrongful convictions is <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>, accounting for more wrongful convictions than any<br />

other factor. 34 Mistaken <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s have been attributed<br />

largely to the inherent unreliability of human perception and memory<br />

and susceptibility to contamination, in addition to suggestive<br />

<strong>identification</strong> procedures used by law enforcement. 35 Compounding the<br />

problem is the tendency of jurors to treat <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s as<br />

highly persuasive evidence because of their lack of understanding of<br />

factors that affect the reliability of such <strong>identification</strong>s. 36<br />

A common misconception is that the human mind works like a<br />

video recorder, passively recording all available information and<br />

storing it for future retrieval. 37 Social-science research has shown that<br />

not only is our ability to accurately perceive events limited, but<br />

32. Innocenceproject.org, News and Information: Fact Sheets,<br />

http://www.innocenceproject.org/Content/351.php (last visited Mar. 16, 2009). Given<br />

that DNA evidence exists in only a small percentage of cases, and that it is preserved<br />

for testing in even fewer, this data likely underestimates the true number of wrongful<br />

convictions. Samuel R. Gross et al., Exonerations in the United States, 1989 Through<br />

2003, 95 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 523, 529 (2005).<br />

33. Although there is no consensus about the exact number of total<br />

exonerations in the United States (which is partially a result of how exoneration is<br />

defined), a recent study estimated that there were 340 total exonerations between 1989<br />

and 2003. Gross et al., supra note 32, at 523–24. This included both DNA exonerations<br />

and exonerations based on other evidence such as non-DNA forensic science,<br />

recantations, and confessions. Id. at 524.<br />

34. Eyewitness mis<strong>identification</strong> played a role in more than 75 percent of<br />

DNA exonerations, Innocenceproject.org, Understand the Causes: Eyewitness<br />

Mis<strong>identification</strong>, http://www.innocenceproject.org/understand/Eyewitness-Misidentific<br />

ation.php (last visited Mar. 16, 2009), and in 88 percent of exonerations in rape cases<br />

between 1989 and 2003. Gross et al., supra note 32, at 544. Other causes of wrongful<br />

convictions include false confessions, faulty forensic science (“junk science”), jailhouse<br />

snitches or informants, false witness testimony, police and prosecutorial misconduct,<br />

and bad lawyering. Innocenceproject.org, supra.<br />

35. Fredric D. Woocher, Note, Did Your Eyes Deceive You? Expert<br />

Psychological Testimony on the Unreliability of Eyewitness Identification, 29 STAN. L.<br />

REV. 969, 970 (1977).<br />

36. Melissa Boyce et al., Belief of Eyewitness Identification Evidence, in 2<br />

HANDBOOK OF EYEWITNESS PSYCHOLOGY: MEMORY FOR PEOPLE 501, 501–02 (Rod<br />

C.L. Lindsay et al. eds., 2007).<br />

37. Woocher, supra note 35, at 975–76.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 771<br />

memories change and degrade over time. 38 Perception is affected by the<br />

natural limitations of the human brain, 39 poor observation conditions, 40<br />

the stressful nature of the event, 41 the race of the viewer, 42 and the<br />

expectations and personal biases of the viewer. 43 These factors cause<br />

<strong>eyewitness</strong>es both to perceive details that did not exist and to fail to<br />

perceive details that did exist. 44 In the process of encoding, storing, and<br />

retrieving memories, details are unconsciously added, altered, or<br />

forgotten, and are vulnerable to even subtle suggestions, such as<br />

leading questions or alternate descriptions. 45 Memory accuracy is<br />

partially a function of time, such that the longer the span between the<br />

original observation and the retrieval of the memory, the less accurate<br />

the memory. 46 Human perception and memory affect not only the<br />

viewing of a crime and later <strong>identification</strong>, but also the moments in<br />

between, when a witness may be asked to produce a composite or view<br />

a composite produced by another witness.<br />

In addition to the fallibility of the human memory, <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>s are also the result of suggestive <strong>identification</strong><br />

procedures used by law enforcement. Unlike the inherent limitations of<br />

perception and memory, these procedures are within the control of the<br />

38. See Elizabeth F. Loftus et al., The Psychology of Eyewitness Testimony,<br />

in PSYCHOLOGICAL METHODS IN CRIMINAL INVESTIGATIONS AND EVIDENCE 3, 25–34<br />

(David C. Raskin ed., 1989); Christian A. Meissner et al., Person Descriptions as<br />

Eyewitness Evidence, in 2 HANDBOOK OF EYEWITNESS PSYCHOLOGY: MEMORY FOR<br />

PEOPLE, supra note 36, at 3, 11–12 ; Woocher, supra note 35, at 982–85.<br />

39. Because people can only perceive a limited number of stimuli at any given<br />

time, they engage in perceptual selectivity, concentrating their attention on “the most<br />

necessary and useful details,” leading to inaccurate perceptions. Woocher, supra note<br />

35, at 976–77. Because <strong>eyewitness</strong>es are often unaware that they are witnessing a crime<br />

until after the event has passed, they are less likely to selectively perceive those details<br />

necessary for accurate <strong>identification</strong>s. Id. at 977.<br />

40. These include, among others, the duration and distance of the observation<br />

and the lighting conditions. Id. at 978.<br />

41. Research shows that stressful situations decrease perception abilities. Id.<br />

at 979. In particular, the presence of a weapon has been found to reduce the reliability<br />

of later <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s. Gary L. Wells & Elizabeth A. Olson, Eyewitness<br />

Testimony, 54 ANN. REV. PSYCHOL. 277, 282 (2003).<br />

42. Research shows that people are less able to identify people of other races,<br />

regardless of increased contact with other people of that race. Christian A. Meissner et<br />

al., Person Descriptions as Eyewitness Evidence, in 2 HANDBOOK OF EYEWITNESS<br />

PSYCHOLOGY: MEMORY FOR PEOPLE, supra note 36, at 3, 15; Woocher, supra note 35,<br />

at 982.<br />

43. Encouraged by law enforcement to give a detailed description of a culprit,<br />

<strong>eyewitness</strong>es tend to believe they perceived more than they did. Woocher, supra note<br />

35, at 981.<br />

44. Id. at 976–77.<br />

45. Id. at 983–84.<br />

46. See id. at 982.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

772 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

criminal justice system, and have been the focus of reforms across the<br />

country. 47 These reforms have included avoiding multiple <strong>identification</strong><br />

procedures with the same suspect; 48 instructing <strong>eyewitness</strong>es prior to a<br />

lineup that the real culprit may or may not be present; 49 using doubleblind<br />

lineups in which the administrator is unaware of the identity of<br />

the suspect; 50 using sequential lineups, in which the participants are<br />

shown to the <strong>eyewitness</strong> one at a time, as opposed to simultaneous<br />

lineups, in which all participants are shown to the <strong>eyewitness</strong> at the<br />

same time; 51 and not giving feedback to <strong>eyewitness</strong>es after they make a<br />

selection. 52 So far, reforms have focused largely on the <strong>identification</strong><br />

itself, rather than procedures leading up to the <strong>identification</strong>, such as<br />

the development of suspects through the use of facial composites. 53<br />

The factors that affect the reliability of <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s<br />

are not always intuitive, and are often counterintuitive. 54 Studies show<br />

47. See, e.g., Gary L. Wells, Eyewitness Identification: Systemic Reforms,<br />

2006 WIS. L. REV. 615, 616 n.9, 634–35, 641–43 [hereinafter Wells, Systemic<br />

Reforms ] (describing <strong>eyewitness</strong>-<strong>identification</strong> reforms in California, Iowa,<br />

Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, North Carolina, Virginia, and Wisconsin);<br />

Gary L. Wells et al., From the Lab to the Police Station: A Successful Application of<br />

Eyewitness Research, 55 AM. PSYCHOLOGIST 581, 589–95 (2000) (describing the U.S.<br />

Department of Justice’s development of national guidelines for the collection and<br />

preservation of <strong>eyewitness</strong> evidence in response to the role of mistaken <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

<strong>identification</strong>s in wrongful convictions).<br />

48. See OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GEN., WIS. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, MODEL<br />

POLICY AND PROCEDURE FOR EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION 6 (2005). Witnesses who may<br />

recognize a suspect they have seen in another procedure believe that it suggests the<br />

suspect is the culprit, or the witness may unconsciously recognize the suspect from the<br />

earlier procedure rather than the original event. Id.<br />

49. Wells & Olson, supra note 41, at 286. Studies show that when witnesses<br />

are given this instruction there is a considerable reduction in mistaken <strong>identification</strong>s<br />

and little effect on accurate <strong>identification</strong>s. Id.<br />

50. Id. at 289. Lineup administrators who are unaware of the identity of the<br />

suspect are unable to provide clues, whether consciously or not, to the <strong>eyewitness</strong>. Id.<br />

51. Id. at 288. Sequential lineups discourage witnesses from engaging in<br />

relative judgment, a process in which people select the participant who most resembles<br />

their memory of the culprit. Id. at 286. Simultaneous lineups are particularly dangerous<br />

when the nonsuspect participants in the lineup, known as fillers, differ from the written<br />

description of the culprit because they can be easily eliminated, particularly if the<br />

suspect is the only participant with a poignant detail, such as a scar or facial hair. See<br />

Wells, Systemic Reforms, supra note 47, at 623–24.<br />

52. See Wells, Systemic Reforms, supra note 47, at 621. Feedback can inflate<br />

a witness’s confidence in his or her selection. Id.<br />

53. See Roberts, supra note 24.<br />

54. Tanja Rapus Benton et al., Has Eyewitness Testimony Research<br />

Penetrated the American Legal System? A Synthesis of Case History, Juror<br />

Knowledge, and Expert Testimony, in 2 HANDBOOK OF EYEWITNESS PSYCHOLOGY:<br />

MEMORY FOR PEOPLE, supra note 36, at 453, 475–85 (concluding that many <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

issues are not common sense to jurors, despite widespread belief that they are); James

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 773<br />

that jurors, and to a lesser extent judges, tend to place undue reliance<br />

on the ability of <strong>eyewitness</strong>es to accurately perceive and retain<br />

memories. 55 In particular, jurors tend to place considerable reliance on<br />

the confidence of an <strong>eyewitness</strong>, which has little or no correlation to<br />

accuracy. 56 Alternatively, jurors tend to underestimate the value of<br />

recent <strong>identification</strong> reforms, such as the administration of the lineup<br />

and selection of lineup fillers. 57 Even if experts testify about indicators<br />

of reliability, jurors may still believe <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s over<br />

convincing alibis. 58<br />

B. Due Process Applied: The Manson v. Brathwaite Standard<br />

Due-process concerns with reliability of <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s<br />

began in the 1960s, when the rights of defendants gained considerable<br />

attention in the courts—years before DNA testing was available. 59 In<br />

United States v. Wade, 60 the Supreme Court first expressed concern<br />

M. Doyle, Legal Issues in Eyewitness Evidence, in PSYCHOLOGICAL METHODS IN<br />

CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION AND EVIDENCE, supra note 38, at 125, 127 (“[C]ommonsense<br />

principles, such as confidence means accuracy or stress enhances alertness [are<br />

questioned by research.]”).<br />

55. Benton et al., supra note 54, at 484–87 (stating that laypeople have an<br />

underlying belief that <strong>eyewitness</strong>es in general tend to be accurate, even when they are<br />

inaccurate).<br />

56. Boyce et al., supra note 36, at 510; Brian R. Clifford & Graham Davies,<br />

Procedures for Obtaining Identification Evidence, in PSYCHOLOGICAL METHODS IN<br />

CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION AND EVIDENCE, supra note 38, at 47, 80 (noting that some<br />

studies have found that confidence is correlated to accuracy, although the correlation is<br />

low).<br />

57. Boyce et al., supra note 36, at 514–15. This may be because the public is<br />

generally unaware of the research on the importance of police procedures on reducing<br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>s. Id. at 516.<br />

58. See Woocher, supra note 35, at 970. Steven Avery, convicted of sexual<br />

assault, had sixteen alibi witnesses testify that he was pouring concrete when the crime<br />

occurred. Penny Beerntsen, Speech at the Benjamin N. Cardozo <strong>School</strong> of <strong>Law</strong><br />

Symposium: Reforming Eyewitness Identification: Convicting the Guilty, Protecting the<br />

Innocent (Sept. 12–13, 2004), in 4 CARDOZO PUB. L. POL’Y & ETHICS J. 239, 245<br />

(2006). The victim positively identified Avery, and he was sentenced to thirty-two<br />

years in prison. Id. Wilton Dedge, convicted of sexual assault, had six alibi witnesses<br />

testify that he was in another city at the time of the crime. AFTER INNOCENCE<br />

(Showtime Independent Films 2005). The victim positively identified Dedge, and he<br />

was sentenced to two concurrent life sentences. Id. Tim Durham, convicted of rape and<br />

robbery, had eleven upstanding alibi witnesses testify that he was participating with his<br />

father in a skeet-shooting contest 250 miles away in another state. SIMON, supra note<br />

17, at 32. The victim positively identified Durham, and he was sentenced to 3220 years<br />

in prison. Id. Avery, Dedge, and Durham were all exonerated by DNA testing.<br />

Innocenceproject.org, supra note 17.<br />

59. See Doyle, supra note 54, at 133.<br />

60. 388 U.S. 218 (1967).

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

774 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

with reliability of <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s, noting that “<strong>identification</strong><br />

evidence is peculiarly riddled with innumerable dangers and variable<br />

factors which might seriously, even crucially, derogate from a fair<br />

trial.” 61 The Court went on to acknowledge that one of the causes of<br />

mistaken <strong>identification</strong>s is “the degree of suggestion inherent in the<br />

manner in which the prosecution presents the suspect to witnesses for<br />

pretrial investigation.” 62 Defendants have traditionally relied on crossexamination<br />

to challenge <strong>eyewitness</strong>es and protect themselves against<br />

the risks of mistaken <strong>identification</strong>s. 63 Although cross-examination is a<br />

very important feature of a trial, it alone does not assure accuracy and<br />

reliability. 64 On the basis of these concerns, the Supreme Court<br />

provided preventative rules to minimize the risk of mistaken <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

<strong>identification</strong>s based on guarantees of due process provided by the Fifth<br />

and Fourteenth Amendments. 65<br />

As set forth in Brathwaite, suggestive <strong>identification</strong> procedures<br />

violate a defendant’s guarantee of due process when there is a<br />

substantial likelihood of irreparable mis<strong>identification</strong>. 66 The remedy is<br />

the exclusion of the evidence at trial. 67 This protection embraces all<br />

forms of <strong>identification</strong> procedures, including show-ups, lineups<br />

(including both photographic and live), and in-court <strong>identification</strong>s,<br />

regardless when they occur. 68<br />

In balancing the protection of suspects with the administration of<br />

justice, Brathwaite established that <strong>identification</strong>s arising from<br />

suggestive procedures are still admissible if they are reliable in light of<br />

61. Id. at 228.<br />

62. Id.<br />

63. See Doyle, supra note 54, at 127.<br />

64. Wade, 388 U.S. at 235.<br />

65. See, e.g., Neil v. Biggers, 409 U.S. 188 (1972) (concluding that<br />

unnecessarily suggestive <strong>identification</strong>s violate due process unless found to be reliable<br />

under the totality of all the circumstances); Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377<br />

(1968) (holding that convictions based on in-court <strong>identification</strong>s must be set aside if<br />

based on impermissibly suggestive out-of-court procedures that give rise to a very<br />

substantial likelihood of irreparable mis<strong>identification</strong>); Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293<br />

(1967) (finding that unnecessarily suggestive <strong>eyewitness</strong> procedures conducive to<br />

irreparable mistaken <strong>identification</strong> violate due process of law). The protections in Wade<br />

were based on the Sixth Amendment right to counsel. 388 U.S. at 224. A later ruling<br />

holding that the Sixth Amendment applies only to postindictment procedures, and not to<br />

those occurring before formal charging, Kirby v. Illinois, 406 U.S. 682 (1972), leaves<br />

many <strong>identification</strong> procedures subject only to due-process protections. See Doyle,<br />

supra note 54, at 133–34. Almost all facial composites, show-ups, and photographic<br />

and live lineups are conducted before the defendant is formally charged, leaving them<br />

without the protection of the Sixth Amendment. Id.<br />

66. See 432 U.S. 98, 106 (1977).<br />

67. Id. at 110.<br />

68. Doyle, supra note 54, at 135.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 775<br />

the totality of the circumstances. 69 The Supreme Court reasoned that<br />

this approach would still deter law enforcement from using suggestive<br />

procedures out of fear that <strong>identification</strong>s might be excluded as<br />

unreliable. 70 Additionally, the Court also emphasized the importance of<br />

admitting reliable evidence that might have otherwise been excluded to<br />

both protect the innocent from being wrongfully convicted and keeping<br />

the guilty from going free. 71<br />

Courts and scholars are beginning to challenge Brathwaite;<br />

however, the criticism is largely directed toward the reliability test, and<br />

not the suggestiveness standard. 72 Most criticism directed toward the<br />

suggestiveness standard emphasizes only that it has not been sufficiently<br />

applied, or that the standard needs to be strengthened to protect the<br />

original concern of providing defendants with a fair trial when<br />

confronted with <strong>eyewitness</strong> <strong>identification</strong>s. 73<br />

69. Brathwaite, 432 U.S. at 114. The factors used to determine reliability<br />

include the opportunity of the witness to view the criminal at the time of the crime, the<br />

witness’s degree of attention, the accuracy of prior descriptions, the witness’s level of<br />

certainty, and the time between the crime and the <strong>identification</strong>. Id. These factors must<br />

be weighed against the suggestiveness of the <strong>identification</strong>. Id.<br />

70. Id. at 112.<br />

71. Id.<br />

72. The challenges to Brathwaite are arising in light of the number of<br />

wrongful convictions stemming from mis<strong>identification</strong>s. See, e.g., Commonwealth v.<br />

Johnson, 650 N.E.2d 1257, 1261 (Mass. 1995); State v. Dubose, 2005 WI 126, 31,<br />

286 Wis. 2d 143, 699 N.W.2d 582; Timothy P. O’Toole & Giovanna Shay, Manson v.<br />

Brathwaite Revisited: Towards a New Rule of Decision for Due Process Challenges to<br />

Eyewitness Identification Procedures, 41 VAL. U. L. REV. 109 (2006); Calvin TerBeek,<br />

A Call for Precedential Heads: Why the Supreme Court’s Eyewitness Identification<br />

Jurisprudence Is Anachronistic and Out-of-Step with the Empirical Reality, 31 LAW &<br />

PSYCHOL. REV. 21, 22 (2007); Ruth Yacona, Manson v. Brathwaite: The Supreme<br />

Court’s Misunderstanding of Eyewitness Identification, 39 J. MARSHALL L. REV. 539,<br />

541–42 (2006). The reliability test in particular is being challenged in light of socialscience<br />

research findings that the reliability factors are not actually indicative of<br />

whether or not an <strong>identification</strong> is reliable. See Gary L. Wells & Deah S. Quinlivan,<br />

Suggestive Eyewitness Identification Procedures and the Supreme Court’s Reliability<br />

Test in Light of Eyewitness Science: 30 Years Later, 33 LAW & HUM. BEHAV. 1, 9<br />

(2009). This Comment argues that even if the reliability test were eliminated, thus<br />

allowing sufficiently suggestive procedures to be inadmissible, Brathwaite’s narrow<br />

focus on lineup procedures would still not adequately protect suspects from<br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>s if facial composites played a role in the <strong>identification</strong>s.<br />

73. See Doyle, supra note 54, at 136–38. Brathwaite has never been expanded<br />

beyond procedures of actual <strong>identification</strong>s to include procedures involving the use of<br />

facial composites, which lead to <strong>identification</strong>s. Applying Brathwaite to the use of facial<br />

composites would help to strengthen the standard by providing more protection against<br />

unreliable <strong>identification</strong>s.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

776 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

II. FACIAL COMPOSITES<br />

Police use facial composites as an investigative tool to help identify<br />

an unknown culprit. Although composites have been used in criminal<br />

investigations for decades, only recently have they become the subject<br />

of social-science research. The results have established that not only are<br />

the current methods of building facial composites unreliable, but they<br />

also have an effect on the reliability of subsequent <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

<strong>identification</strong>s. To protect against mis<strong>identification</strong>s stemming from the<br />

use of facial composites, the protections of Brathwaite should be<br />

expanded to apply not just to procedures in which an <strong>eyewitness</strong><br />

identifies a suspect, but also to the procedures that label individuals as<br />

suspects in the first place.<br />

A. The Use of Facial Composites in Criminal Investigations<br />

For over a century, law-enforcement agencies have sought to<br />

create images of unknown culprits to help identify potential suspects. 74<br />

The resulting image, known as a facial composite, 75 has a variety of<br />

uses within a criminal investigation. Facial composites may be<br />

distributed to the public to generate leads 76 or used solely as a tool to<br />

confirm or eliminate suspects gathered through other means. 77<br />

74. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 11–42.<br />

75. A facial composite is the composite drawing of a face “made up from the<br />

combination of individually described component parts.” TAYLOR, supra note 17, at<br />

197. A facial composite may be a freehand drawing, or may be developed from a handassembled<br />

or computer-generated system. Id. at 197–98.<br />

76. Gary L. Wells et al., Building Face Composites Can Harm Lineup<br />

Identification Performance, 11 J. OF EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOL.: APPLIED 147, 147<br />

(2005).<br />

77. Stephen MacDonald, ‘Wanted’ Art: Meet a Man Who Draws Shady<br />

Characters, WALL ST. J., Aug. 2, 1984. In the United Kingdom, only 10 percent of<br />

facial composites are released to the media; the others are used for internal inquiries.<br />

Graham M. Davies & Tim Valentine, Facial Composites: Forensic Utility and<br />

Psychological Research, in 2 HANDBOOK OF EYEWITNESS PSYCHOLOGY: MEMORY FOR<br />

PEOPLE, supra note 36, at 59. By contrast, in a recent study of facial composites in the<br />

United States, 68 percent of respondents from law-enforcement agencies reported that<br />

they release composites to the news media. Dawn McQuiston-Surrett et al., Use of<br />

Facial Composite Systems in U.S. <strong>Law</strong> Enforcement Agencies, 12 PSYCHOL., CRIME &<br />

LAW 505, 511 (2006). Facial composites can also be used as a “poor man’s lie detector”<br />

to determine whether a witness is being truthful. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 187<br />

(“Some people describe a face that is totally fictitious, making it up as they go along,<br />

while others describe a face that actually exists, which they have predetermined to<br />

focus upon mentally.”); Ben Penserga, Sketch Artists, DAILY TIMES (Salisbury, Md.),<br />

Oct. 20, 2003, at 1.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 777<br />

The method of creating a likeness has changed with technology<br />

over the years. 78 Traditionally, facial composites were hand-drawn<br />

sketches, prepared by either a freelance artist or an officer who had a<br />

natural talent for drawing. 79 Yet, despite the artistic skills of forensic<br />

artists, most have little formal training in forensic art and there is little<br />

to no standardization within the field. 80<br />

Police artists stress that the purpose of drawing a composite is not<br />

to create a photographic image of the person, but rather to create a<br />

likeness. 81 As one forensic artists explains, “When you see a<br />

photograph, it points to a real-life face we’re looking for. What we’re<br />

saying with a pencil sketch is that the statement is broad—anybody this<br />

face reminds you of, let us know.” 82 The process begins by<br />

interviewing an <strong>eyewitness</strong> to obtain a description of the culprit. 83<br />

Given this initial information, the artist should sketch the basic<br />

proportions of the face and establish the basic facial character, rather<br />

than focusing on individual features. 84 This is because humans<br />

remember faces holistically, not feature-by-feature, focusing on the<br />

spatial relationships of the face. 85 The artist should follow by asking<br />

78. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 11–42.<br />

79. Id. at 8.<br />

80. As recently as the 1980s, most forensic artists received no special training<br />

and there was no standardization within the field. Frank Domingo, Composite Art: A<br />

Need for Standardization, IDENTIFICATION NEWS, June 1984, at 7. As one police artist<br />

noted, “There are no rules. Nobody teaches it, and everyone who does it has to figure<br />

out his own way of working.” MacDonald, supra note 77. The International<br />

Identification Association now offers certifications in composite art, requiring 120<br />

hours of education from approved schools, two years’ experience of full-time work,<br />

fifteen completed composites, and two letters of recommendation. TheIAI.org, Forensic<br />

Artist Certification Process, http://www.theiai.org/certifications/artist/index.php (last<br />

visited Mar. 16, 2009). However, there is still an overall lack of standardization<br />

nationally. Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 51.<br />

81. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 166; Graham Davies, Capturing Likeness<br />

in Eyewitness Composites: The Police Artist and His Rivals, 26 MED. SCI. & LAW 283,<br />

284 (1986).<br />

82. Robert Christgau, First an Artist, Then a Cop, 6 SOC. ACTION & LAW 41,<br />

41 (1980).<br />

83. Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 48–52. To avoid suggestion,<br />

witnesses should be encouraged to begin a free recall of the culprit, with the artist<br />

guiding the conversation with open-ended questions. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at<br />

168.<br />

84. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 143–45, 168–69. Other methods differ in that<br />

they allow witnesses to view photographic references before a preliminary sketch. See<br />

Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 52. The danger in this is that the witness’s<br />

memory may be contaminated by the visual image. See infra note 91 and accompanying<br />

text.<br />

85. See John W. Sheperd & Hayden D. Ellis, Face Recall—Methods and<br />

Problems, in PSYCHOLOGICAL ISSUES IN EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION 87, 88 (Siegfried

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

778 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

more structured, open-ended questions about particular features of the<br />

face, or by offering multiple-choice-style questions. 86<br />

Many artists choose to selectively show the witness photographic<br />

references from facial-<strong>identification</strong> catalogs, mug shots, or magazines<br />

to fine-tune the drawing. 87 Facial-<strong>identification</strong> catalogs consist of pages<br />

filled with photographs of faces, in which most of the face is blocked<br />

out except one individual feature. 88 For example, a page marked<br />

“Bulging Eyes” from the FBI Facial Identification Catalog portrays<br />

sixteen photographs of male faces with gray boxes placed over the<br />

lower portion of the face covering the nose and mouth, focusing the<br />

reader on the eyes. 89 If a witness described a culprit as having bulging<br />

eyes, an artist would be able to more accurately depict the eyes by<br />

looking at a visual reference selected by the witness, rather than the<br />

witness’s verbal description alone. 90 Although photographic references<br />

are useful to draw features not easily described by words, they should<br />

be used with care to avoid contamination of the witnesses’ memories. 91<br />

After the completion of a sketch, witnesses should be allowed to view<br />

the image, make final suggestions, and evaluate the quality of the<br />

sketch. 92<br />

In the 1950s, mechanical systems composed of clear sheets printed<br />

with various individual facial features were developed as an alternative<br />

to hand-drawn composites. 93 Although features could be altered with a<br />

Ludwig Sporer et al. eds., 1996). Because untrained artists tend to focus more on<br />

features, rather than proportions, composites tend to be inaccurate likenesses. TAYLOR,<br />

supra note 17, at 95; see infra Part II.B.1.<br />

86. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 169. Open-ended and multiple-choice forms of<br />

questioning avoid the potential for suggestion and ensure the witness is not<br />

subconsciously altering his or her memory based on new information. Id. at 191. For<br />

example, “Tell me about his eyes?” or, “Would you describe his eyes as wide open and<br />

large, average in size, or small and narrowed?” are more appropriate than, “Were his<br />

eyes brown or hazel?” Id.<br />

87. Id. at 223–27.<br />

88. LOIS GIBSON, FORENSIC ART ESSENTIALS: A MANUAL FOR LAW<br />

ENFORCEMENT ARTISTS 15–18 (2007).<br />

89. Id. at 15.<br />

90. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 222.<br />

91. See id. at 146–48, 169–71, 191–92, 222; see also infra Part I.A. One<br />

indicator that a witness’s mind has been contaminated by other images is whether or not<br />

the sketch deviates from the original description. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 171.<br />

92. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 171, 232. Some witnesses might enhance their<br />

confidence of the sketch at a later point, so it is important to record their confidence<br />

when the composite is first produced.<br />

93. Id. at 21–22. Depending on the type of system, the features were either<br />

stacked on top of each other or arranged together to create a facial composite. Id. at 22,<br />

202–03.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 779<br />

wax pencil, 94 they inherently provided witnesses with a more limited<br />

selection of features. Additionally, since law-enforcement agencies<br />

usually relied on mechanical systems because they could not afford or<br />

did not have access to trained composite artists, 95 the systems were<br />

generally operated by officers with little or no training. 96<br />

This combination of few options and untrained operators can have<br />

disastrous results. The facial composite that led to the <strong>identification</strong> of<br />

Bloodsworth was produced with a mechanical composite system by an<br />

officer with no artistic skills and only three days of training at a<br />

seminar ten years earlier. 97 When the witness, a young boy, asked if the<br />

mustache could be thickened, the officer refused. 98 The only other<br />

mustaches resembled Fu Manchu mustaches, and the officer did not<br />

want to waste time calling in a freelance artist. 99 The young boy was<br />

also unsatisfied with the hair and eyes, but was limited to the options<br />

offered by the system. 100 Despite these misgivings, the police<br />

distributed the sketch to the public. 101<br />

Although mechanical systems are still in use, law-enforcement<br />

agencies in the United States briefly reverted to hand-drawn composites<br />

in the 1970s until the development of computer systems in the 1980s. 102<br />

Given the scarcity and high cost of forensic artists, many lawenforcement<br />

agencies have chosen to rely on computer systems<br />

instead. 103 Although they provide ease of use, they contain the same<br />

94. Id. at 203.<br />

95. See Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 52; Davies, supra note 81, at 289<br />

(“Police artists are a precious and expensive commodity which is only ever likely to be<br />

available to the largest of police departments. To distil the essence of their skills into a<br />

cheap and easily-operated package suitable for a standard microcomputer is an obvious<br />

next step in the development of the composite.”).<br />

96. Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 55. Not only were most operators<br />

unable to alter features accurately, but because they were not artists, they also tended to<br />

know little about the importance of proportion. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 95. Even if a<br />

witness accurately selected individual features, incorrect positioning of the features<br />

caused by unskilled operators or the natural limitations of the system could result in a<br />

likeness drastically different from the culprit. Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 60.<br />

97. JUNKIN, supra note 1, at 44–45.<br />

98. Id. at 46.<br />

99. Id.<br />

100. Id. at 45–46.<br />

101. Id. at 47.<br />

102. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 26–36. The computer systems are based on the<br />

mechanical systems of assemblage. Id. at 36.<br />

103. See Laura Kuhn, High-Tech Sketch Program Helps Police Catch Crooks,<br />

DAILY ILLINI (Champaign, Ill.), Apr. 23, 1999; Penserga, supra note 77. In a recent<br />

survey, 80 percent of law-enforcement respondents reported using a computer system to<br />

create a composite. See McQuiston-Surrett et al., supra note 77, at 509.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

780 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

problems as their predecessors: limited features with limited ability to<br />

modify the images. 104<br />

The effectiveness of facial composites in identifying suspects is<br />

difficult to measure. <strong>Law</strong>-enforcement agencies typically do not keep<br />

records of facial composites that led to arrests, or records showing how<br />

accurately the composites resembled those eventually convicted. 105<br />

Furthermore, witnesses’ memories are subject to contamination by<br />

subtle suggestions in descriptions of the culprit or photographs they<br />

view while producing the composite. 106 For example, some victims<br />

unknowingly describe a police officer who appeared at the scene or<br />

someone in the ambulance. 107<br />

Facial composites can also be so generic that they resemble many<br />

people. 108 While this may result in additional leads, it creates<br />

unwarranted suspicion of those who are innocent. 109 Despite all the<br />

good-faith efforts of forensic artists, most composites do not accurately<br />

resemble the culprits (or are so generic they resemble everyone). 110<br />

Additionally, they have the ability to taint the memory of the witnesses<br />

who help prepare them, twice furthering the risk of a later<br />

mis<strong>identification</strong>. 111 Recently, the varied uses of facial composites in<br />

criminal investigations have been the subject of psychological research;<br />

this research has undermined the reliability of facial composites and<br />

their effectiveness in criminal investigations.<br />

B. Social-Science Research on Facial Composites<br />

A growing body of social-science research has revealed that the<br />

current methods of creating facial composites are unable to produce<br />

reliably accurate likenesses of suspects. Additionally, studies have also<br />

found that <strong>eyewitness</strong>es who help build facial composites are less likely<br />

104. See TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 203–04. Computer systems often lack<br />

sufficient female features and features of certain racial and ethnic groups. Id. at 204.<br />

They are also limited in their ability to add specific details, such as hats, jewelry, or<br />

unique hairstyles. Id.<br />

105. Clifford & Davies, supra note 56, at 52.<br />

106. See supra notes 43, 91, and accompanying text.<br />

107. TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 190.<br />

108. See Kuhn, supra note 103 (“[P]ictures produced by using [E-FIT, a<br />

computer composite system] tend to be extremely general in appearance and prompt<br />

people to see their neighbors and classmates in the pictures . . . . [T]he vagueness of<br />

the pictures was a problem with the Identi-Kit as well.”).<br />

109. One artist insists that “[c]omposites do not get innocent people in<br />

trouble.” TAYLOR, supra note 17, at 167. However, the lengthy list of names supra<br />

note 17 suggests the opposite.<br />

110. See infra Part II.B.1.<br />

111. See infra Part II.B.2.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 781<br />

to accurately identify suspects in subsequent <strong>identification</strong>s. These two<br />

findings highlight the dangers of using facial composites and the<br />

potential for mistaken <strong>identification</strong>s.<br />

1. RELIABILITY OF FACIAL COMPOSITES<br />

Social-science studies have consistently shown that all methods<br />

used by law enforcement to produce facial composites are generally<br />

unreliable. 112 The various methods, including hand-drawn sketches and<br />

composites created from mechanical or computerized systems, are often<br />

unable to produce a recognizable image of the person being<br />

described. 113 According to psychologist Charlie Frowd, composites only<br />

112. See generally OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GEN., supra note 48, at 26<br />

(“Research tends to show that none of the existing methods can reliably produce<br />

recognizable composites in real-world settings.”); McQuiston-Surrett et al., supra note<br />

77, at 506 (“[R]eliance on forensic artists for this purpose has largely been replaced by<br />

facial composite ‘systems’ . . . . Yet decades of empirical studies have demonstrated<br />

that there were difficulties with both traditional composite systems and newer<br />

computer-based technologies in their ability to accurately depict an individual . . . .”);<br />

Wells et al., supra note 76, at 147 (“Research has consistently shown that various facial<br />

composite systems yield hit rates on the original faces that are barely above chance<br />

levels of performance.”).<br />

113. See, e.g., Davies & Valentine, supra note 77, at 71 (describing a 1999<br />

study in which only 10 percent of E-FIT composites made from views of famous faces<br />

were named, and only 6 percent of composites were made from memory; also reporting<br />

a 25 percent overall false-naming rate); Graham Davies & Melissa Little, Drawing on<br />

Memory: Exploring the Expertise of a Police Artist, 30 MED. SCI. & LAW 345, 352<br />

(1990) (finding the feature-by-feature approach employed by mechanical systems<br />

produces poor likeness); Graham Davies et al., Facial Composite Production: A<br />

Comparison of Mechanical and Computer-Driven Systems, 85 J. APPLIED PSYCHOL.<br />

119, 123 (2000) (stating that witnesses cannot build a reliable likeness on a computer<br />

system relying on memory alone); Hadyn Ellis et al., An Investigation of the Use of the<br />

Photo-fit Technique for Recalling Faces, 66 BRIT. J. PSYCHOL. 29, 34–35 (1975) (noting<br />

that the accuracy rate of choosing the correct target from several faces based on a<br />

composite created by Photo-FIT was only 12.5 percent); Charlie D. Frowd et al.,<br />

Contemporary Composite Techniques: The Impact of a Forensically-Relevant Target<br />

Delay, 10 LEGAL & CRIMINOLOGICAL PSYCHOL. 63, 75 (2005) (finding that participants<br />

were only able to correctly identify images of famous faces produced by sketch artists 8<br />

percent of the time, and 3 percent of the time for computerized systems); Debra L.<br />

Green & R. Edward Geiselman, Building Composite Facial Images: Effects of Feature<br />

Saliency and Delay of Construction, 74 J. APPLIED PSYCHOL. 714, 717 (1989)<br />

(discussing the <strong>identification</strong> accuracy of faces with salient features based on Identi-Kit<br />

composites at chance levels); Christine E. Koehn & Ronald P. Fisher, Constructing<br />

Facial Composites with the Mac-a-Mug Pro System, 3 PSYCHOL. CRIME & LAW 209,<br />

215 (1997) (stating that ratings of likeness of composites created on Mac-a-Mug<br />

compared to photographs were “not even remotely similar,” and only 4 percent of<br />

<strong>identification</strong>s were accurate lineups); Kenneth R. Laughery & Richard H. Fowler,<br />

Sketch Artist and Identi-Kit Procedures for Recalling Faces, 65 J. APPLIED PSYCHOL.<br />

307, 313–15 (1980) (noting that Identi-Kit composites rated poorer than artists’ sketches

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

782 WISCONSIN LAW REVIEW<br />

have an accuracy rate of about 20 percent whether created by a<br />

composite artist or a computerized system. 114 That rate drops into the<br />

single digits if the witness waits for a few days to a week before<br />

preparing the composite, which is typical in a criminal investigation. 115<br />

If an <strong>eyewitness</strong> to a crime is asked to produce a facial composite,<br />

research shows that the result will likely be an image that does not<br />

resemble the culprit, making it less likely that the culprit will be<br />

identified and more likely that innocent people who resemble the sketch<br />

will become suspects. 116<br />

Mechanical composite systems, particularly Identi-Kit and Photo-<br />

FIT have been the focus of numerous psychological studies that show<br />

an inability to accurately capture the likeness of a culprit. 117 An initial<br />

study of Photo-FIT illustrated its inability to create accurate<br />

likenesses. 118 Participants were only able to correctly match one in eight<br />

of the composites with the photographs they were supposed to<br />

represent, even when looking at the photographs. 119 Additional studies<br />

for likeness; all images, including those produced by artists, were generally regarded as<br />

poor quality).<br />

114. Mark Roth, Why Police Composites Don’t Always Hit Mark, PITTSBURGH<br />

POST-GAZETTE, Mar. 25, 2007, at A1.<br />

115. Id.<br />

116. Despite the fact that composite artists and law enforcement often insist that<br />

resemblance to a composite is not a positive <strong>identification</strong> of the culprit or evidence of<br />

guilt by itself, in reality that is not always the case. Even after DNA tests excluded<br />

Wilton Dedge as the donor of two pubic hairs found on a rape victim’s bed sheets—<br />

hairs that were used as evidence of Dedge’s guilt at trial—the prosecutor refused to<br />

accept that Dredge could be innocent, arguing that the strong resemblance between<br />

Dedge and the composite sketch of the rapist established his guilt. AFTER INNOCENCE<br />

(Showtime Independent Films 2005). In another case, James O’Donnell was arrested<br />

for a sexual assault after an anonymous caller alerted the authorities that O’Donnell<br />

resembled a composite sketch. SIMON, supra note 17, at 80. Before placing him in a<br />

lineup, an officer pulled back O’Donnell’s hair and slicked down the sides so that he<br />

would more closely resemble the sketch; the victim identified O’Donnell in the lineup<br />

and he was later convicted. Id. As Jennifer Thompson identified Ronald Cotton in a<br />

lineup, she thought to herself, “You were the closest likeness of the drawing. You had<br />

become my rapist.” AFTER INNOCENCE (Showtime Independent Films 2005). The<br />

significant weight placed on a composite by the prosecutor in Dedge’s case, an officer<br />

in O’Donnell’s case, and the victim in Cotton’s case portrays the power of a composite<br />

throughout the levels of the criminal justice system to convey guilt, despite a lack of<br />

independent evidence. Dedge, O’Donnell, and Cotton were all eventually exonerated<br />

after DNA testing conclusively proved their innocence. Innocenceproject.org, supra<br />

note 17.<br />

117. Frowd et al., supra note 113, at 64.<br />

118. Ellis et al., supra note 113, at 34–35.<br />

119. Id.

MCNAMARA - FINAL 5/20/2009 5:17 PM<br />

2009:763 Eyewitness-Identification Procedures 783<br />

confirmed the poor quality of likeness produced by composites, with<br />

researchers concluding that the system itself was inadequate. 120<br />

Breaking down the assumption that a picture is worth a thousand<br />

words, a surprising study found that the verbal descriptions were<br />

significantly superior to Photo-FIT composites as guides to likeness;<br />

judges were more likely to identify a target upon reading a verbal<br />

description than viewing a composite. 121 Research on Identi-Kit showed<br />

similar, unfavorable results. Hand-drawn composites produced by an<br />

artist were rated as superior representation to those produced using<br />

Identi-Kit, including both composites made from memory and those<br />

made with a photograph in view. 122<br />

Supporting the findings made within the confines of a laboratory,<br />

studies of the operational effectiveness of mechanical composite<br />

systems reveal disappointing results. 123 According to officers in the<br />

United Kingdom, Photo-FIT was only responsible for solving 5 percent<br />

of cases, and was considered not very useful or not useful at all in 45<br />

percent of cases. 124 In Israel, roughly 25 percent of cases using Identi-<br />

Kit led to convictions, but only 2 percent were significantly aided by<br />

the composite. 125 These results are significant given that roughly 22<br />

percent of police officers in the United States report relying upon<br />

mechanical systems to create composites. 126<br />

Despite the enhanced offerings of computerized systems, such as a<br />

more expansive selection of facial features and accessories and greater<br />

ability to modify the images, they may be as unreliable as mechanical<br />

systems. 127 Initial research of one program found that the system was<br />

120. Graham Davies et al., Face Identification: The Influence of Delay upon<br />

Accuracy of Photofit Construction, 6 J. POLICE SCI. & ADMIN. 35, 42 (1978); Hadyn D.<br />

Ellis et al., A Critical Examination of the Photofit System for Recalling Faces, 21<br />

ERGONOMICS 297, 306 (1978) (“The results of the experiments reported here . . .<br />

suggest that there are severe limitations to the usefulness of the Photofit system as a<br />

method for enabling people to recall faces.”).<br />

121. Donald F. M. Christie & Hadyn D. Ellis, Photofit Constructions Versus<br />

Verbal Descriptions of Faces, 66 J. APPLIED PSYCHOL. 358, 362 (1981). Additionally,<br />