pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

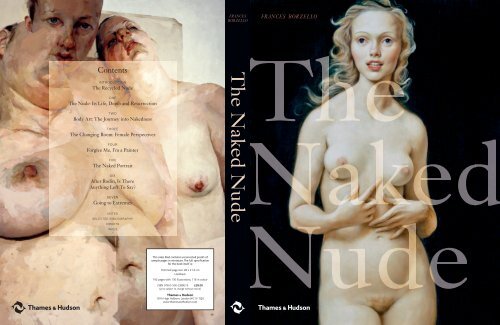

Contents<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Recycled Nude<br />

ONE<br />

The Nude: Its Life, Death and Resurrection<br />

TWO<br />

Body Art: The Journey into Nakedness<br />

THREE<br />

The Changing Room: Female Perspectives<br />

FOUR<br />

Forgive Me, I’m a Painter<br />

FIVE<br />

The Naked Portrait<br />

SIX<br />

After Rodin, Is There<br />

Anything Left To Say?<br />

SEVEN<br />

Going to Extremes<br />

NOTES<br />

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

CREDITS<br />

INDEX<br />

This sales blad contains uncorrected proofs of<br />

sample pages in miniature. The full specifi cation<br />

for the book itself is:<br />

Trimmed page size: 28 x 21.4 cm<br />

Hardback<br />

192 pages with 130 illustrations, 116 in colour<br />

ISBN 978-0-500-23892-9 £28.00<br />

(price subject to change without notice)<br />

Thames & Hudson<br />

181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX<br />

www.thamesandhudson.com<br />

FRANCES<br />

BORZELLO<br />

The Naked Nude<br />

FRANCES BORZELLO<br />

The<br />

Naked<br />

Nude

Jemima Stehli, Strip, 2001, set of ten chromogenic photographs mounted<br />

on aluminium. In the photographic Strip series, Stehli gradually removes her<br />

clothes in front of five men from the art world (representing the male gaze).<br />

She asked each to use a cable shutter-release to photograph her during her<br />

striptease. Her aim was to record the response of a male caught in a position<br />

of some vulnerability as he is looked at while he looks.<br />

50 Body Art: The Journey into Nakedness<br />

51<br />

Naked_Nudes_Blad_spreads.indd 50-51 21/02/2012 12:59<br />

62<br />

The Changing Room: Female Perspectives<br />

LEFT Paula Modersohn-<br />

Becker, Self-Portrait, 1906,<br />

oil on card. Surely art’s first<br />

naked, pregnant self-portrait,<br />

Modersohn-Becker’s painting<br />

was made, according to its<br />

inscription, on the occasion of<br />

her sixth wedding anniversary.<br />

As far as is known, she was<br />

not pregnant when she<br />

painted it, which suggests<br />

that this is a work of personal<br />

exploration as she wonders<br />

about the effect of pregnancy<br />

on her life.<br />

OPPOSITE Lotte Laserstein,<br />

Morning Toilette, 1930, oil on<br />

panel. The large feet, sensible<br />

hair cut and sturdy legs of<br />

Laserstein’s depiction of her<br />

model washing suggest<br />

strength and purpose and are<br />

far from the passive female<br />

body beloved of male artists<br />

of the past.<br />

Naked_Nudes_Blad_spreads.indd 62-63 21/02/2012 12:59<br />

masculine imaginings of a frightened girl by stressing her gawky subject’s difference<br />

from the younger adolescents that form the frieze behind her. By extending the young<br />

girl’s arms and legs, the artist emphasizes the idea of a body that runs slightly ahead of<br />

its owner. There is less stress on sexuality than in the Munch and more on the strange<br />

new body changes, which must surely stem from a female insider’s point of view.<br />

It has been assumed that in the absence of any opportunity to study the life<br />

model, something men took for granted, women in the past who were serious about<br />

their art would try to learn about the body from drawing themselves without their<br />

clothes on. Gwen John did several watercolours and drawings of herself naked in<br />

her Paris apartment. To make money to support herself in Paris, she modelled, and<br />

one of the people she modelled for was Auguste Rodin. The inevitable happened but<br />

unfortunately, as also tends to happen, her passion outlasted his. A watercolour of<br />

herself sitting on a bed naked, painted about 1908–9, is one of a fascinating group of<br />

LEFT Edvard Munch,<br />

Puberty, 1894–5, oil on<br />

canvas.<br />

FAR LEFT Elena Luksch-<br />

Makowsky, Adolescentia,<br />

1903, oil on canvas.<br />

Munch seems to emphasize<br />

the sexual terrors of the young<br />

girl sitting self-protectively on<br />

the bed. In contrast, Elena<br />

Luksch-Makowsky<br />

concentrates on the physical<br />

gawkiness of the young<br />

woman’s arms and legs,<br />

which seem to be growing<br />

rapidly away from her.<br />

Gwen John, Self-Portrait<br />

Sitting Naked on Her Bed,<br />

c. 1908–9, gouache and<br />

pencil on paper. Gwen John’s<br />

watercolours and drawings of<br />

herself reveal her confidence<br />

in the body that had been<br />

brought to life by her lover,<br />

the sculptor Rodin.<br />

60 The Changing Room: Female Perspectives<br />

61<br />

Naked_Nudes_Blad_spreads.indd 60-61 21/02/2012 12:59<br />

bodily appearance and the historical one of idealization.’ However, his way of doing so<br />

is extremely singular for an artist. He has no desire for the casts of his body to carry any<br />

aesthetic value or interest in their own right. Instead, their value lies in the uses to which<br />

he puts them. ‘I think of the work as a catalyst or resonator whose value or significance is<br />

not intrinsic but is generated in relation to the viewer and to its context.’ 5<br />

Since 1997 Gormley has been populating a series of landscapes with iron casts<br />

of his own body. Among the most ambitious of Gormley’s sited sculptures is Horizon<br />

Field, situated high in the Austrian Alps and composed of a hundred iron bodies spread<br />

over seven valleys with all of the sculptures positioned at a height of 2,039 metres to<br />

create an artistic field that makes its own horizon. He says such works represent his<br />

attempts to ask a simple question in material terms: Where does the human being fit<br />

in the scheme of things? ‘Sculpture doesn’t need a roof or a label. You don’t need to<br />

pass over the threshold of an institution in order to experience something that engages<br />

your imagination and, with luck, your body. When placed in the outdoors in rain and<br />

sunshine, in summer and winter, in daylight and moonlight, sculpture, in my view,<br />

begins to live and its silence becomes a potent marker in time and space. People may<br />

well ask “What the hell is this thing doing here?” and the work returns that question and<br />

it responds reflexively “What the hell are you doing here?”.’ 6<br />

Despite Gormley’s denial of the usefulness of the art of the past, it is hard to<br />

divorce his nudes from it, even if just as a point of comparison. There is something of<br />

Ron Mueck, Dead Dad,<br />

1996–7, mixed media.<br />

Everything about this work<br />

operates in opposition to the<br />

notion of the ideal nude.<br />

Instead of generalized<br />

perfection, Mueck<br />

reproduces every wrinkle, hair<br />

and vein in his detailed<br />

portrait of his father’s body.<br />

the Renaissance about his goal of using his body as a kind of surrogate for us to view<br />

the world. Is that so very different from the miraculous one-point perspective of<br />

the 15th century, which offered an optimum spot from which the viewer could see a<br />

painting in its full three-dimensional glory? A journalist once put this link to humanity<br />

and to the sculptural tradition in a less elevated manner: ‘Some lonely art lovers have<br />

probably spent more time scrutinizing his rough-cast bottoms than they have a living<br />

human’s. In the world of sculpture only Michelangelo’s David and the Venus de Milo<br />

are more gawped at.’ 7 In 2011 Gormley faced up to his sculptural heritage – literally.<br />

Invited to show at the Hermitage in St Petersburg, he ‘deplinthed’ a group of classical<br />

sculptures by sinking them into a false floor, enabling visitors to come face to face with<br />

these personified icons of human character at its best. For the adjoining courtyard, he<br />

constructed a group of pixelated, blocky humanoids, crumbling and wavering in the<br />

confusions caused by life today. His aim was to present a modern dystopian contrast to<br />

the classical confidence of the perfect body.<br />

Hyperrealism and change of scale are the tools of Australian sculptor Ron<br />

Mueck, who has taken great pains to leave behind the traditional materials of sculpture<br />

and to choose as subjects any body other than the ideal. His sculptures seem closer<br />

to the art of making waxworks than to the bronzes and marbles of high art. Mueck is<br />

Ron Mueck, Mother and<br />

Child, 2001, mixed media.<br />

A first in the history of art is<br />

this larger-than-life sculpture<br />

of a mother and newborn<br />

child with attached umbilical<br />

cord. Its replacement of the<br />

classical ideal of exterior<br />

perfection with the interior<br />

functions of the body makes<br />

this indisputably a nude for<br />

our time.<br />

148 After Rodin, Is There Anything Left to Say?<br />

149<br />

Naked_Nudes_Blad_spreads.indd 148-149 21/02/2012 12:59

![01 -[BE/INT-2] 2 KOL +UITGEV+ - exhibitions international](https://img.yumpu.com/19621858/1/184x260/01-be-int-2-2-kol-uitgev-exhibitions-international.jpg?quality=85)