- Page 1 and 2: Priscila Lena Farias / Anna Calvera

- Page 3 and 4: Design Frontiers: Territories, Conc

- Page 5 and 6: The following chapter contains 28 p

- Page 7 and 8: 68 The Information Department at th

- Page 9 and 10: 179 Political Toys: Perón’s gift

- Page 11 and 12: 285 Design promotion in Belgium in

- Page 13 and 14: 396 Graphic innovations implemented

- Page 15 and 16: 502 The graphic translation by the

- Page 17 and 18: 612 About the editors / 613 About I

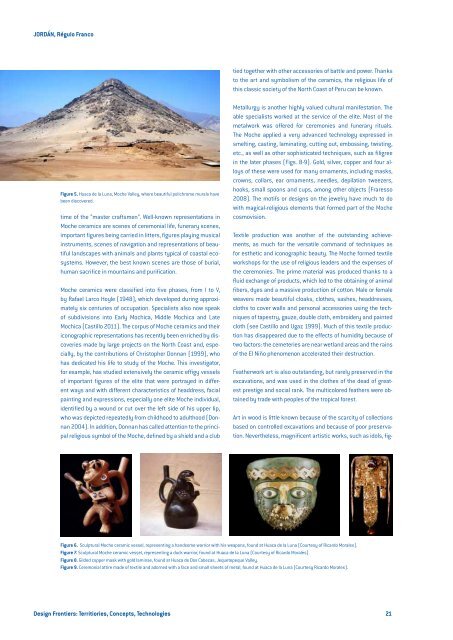

- Page 19: Art, symbolism and power in Moche S

- Page 23 and 24: JORDÁN, Régulo Franco Figure 14.

- Page 25 and 26: Pioneers of Brazilian Design CUNHA

- Page 27 and 28: CUNHA LIMA, Guilherme Janeiro. In t

- Page 29 and 30: Traditions, archaeologies and genea

- Page 31 and 32: Traditions, archaeologies and genea

- Page 33 and 34: History of design education Haruhik

- Page 35 and 36: Academies of Art and schools of Des

- Page 37 and 38: Academies of Art and schools of Des

- Page 39 and 40: A fruitless misunderstanding: the h

- Page 41 and 42: Japanese industrial design concepts

- Page 43 and 44: AMAGAI, Yoshinori design new Japane

- Page 45 and 46: Best Maugard, Elena Izcue and Theod

- Page 47 and 48: BARBOSA, Ana Mae Figure 2. Surface

- Page 49 and 50: BARBOSA, Ana Mae lic education. Mas

- Page 51 and 52: Design history: from service subjec

- Page 53 and 54: Design history: from service subjec

- Page 55 and 56: Pevsner on Design education: meetin

- Page 57 and 58: Pevsner on Design education: meetin

- Page 59 and 60: Antipodean Design Science: applied

- Page 61 and 62: WAITE, Noel nificant sea-change in

- Page 63 and 64: Bauhaus pedagogy and digital design

- Page 65 and 66: ANAY, Hakan / ÖZTEN, Ülkü concep

- Page 67 and 68: ANAY, Hakan / ÖZTEN, Ülkü Ülkü

- Page 69 and 70: The Information Department at the U

- Page 71 and 72:

The Information Department at the U

- Page 73 and 74:

Search for meaning: a study on the

- Page 75 and 76:

CAMARGO, Iara Pierro de / VELLOSO,

- Page 77 and 78:

CAMARGO, Iara Pierro de / VELLOSO,

- Page 79 and 80:

(not)Solving (non)problems: Design

- Page 81 and 82:

(not)Solving (non)problems: Design

- Page 83 and 84:

The role of typeface categorization

- Page 85 and 86:

The role of typeface categorization

- Page 87 and 88:

The role of typeface categorization

- Page 89 and 90:

A sparkle in people’s eyes PACHEC

- Page 91 and 92:

PACHECO, Heliana Soneghet / TOLEDO,

- Page 93 and 94:

Past, present and future of designe

- Page 95 and 96:

LIMA, Ana Gabriela Godinho / STEFAN

- Page 97 and 98:

John Ross’ pioneering role and co

- Page 99 and 100:

RYU, Hyun-guk The author(s) of this

- Page 101 and 102:

RYU, Hyun-guk The author(s) of this

- Page 103 and 104:

Teaching arts and crafts or the tec

- Page 105 and 106:

Teaching arts and crafts or the tec

- Page 107 and 108:

Design in Brazil: which revolution?

- Page 109 and 110:

NOBRE, Ana Luiza Nations Economic C

- Page 111 and 112:

The historical trajectory of the pi

- Page 113 and 114:

The historical trajectory of the pi

- Page 115 and 116:

Educational practice discourse on t

- Page 117 and 118:

OLIVEIRA, Izabel Maria de / COUTO,

- Page 119 and 120:

Identities and territories Oscar Sa

- Page 121 and 122:

The island of Italian Design? Some

- Page 123 and 124:

The island of Italian Design? Some

- Page 125 and 126:

Design without borders: the nomadic

- Page 127 and 128:

BARBOSA, Lara Leite be made with in

- Page 129 and 130:

BARBOSA, Lara Leite goods. A better

- Page 131 and 132:

Redesigning Turkish cult objects: f

- Page 133 and 134:

Redesigning turkish cult objects: f

- Page 135 and 136:

Incubation in isolation: how distan

- Page 137 and 138:

SMYTHE, Michael Figure 3. from left

- Page 139 and 140:

SMYTHE, Michael Figure 7. from left

- Page 141 and 142:

SMYTHE, Michael Figure 11. from lef

- Page 143 and 144:

Design Promises: the case study of

- Page 145 and 146:

BOONLAOR, Nanthana / CHUENRUDEEMOL,

- Page 147 and 148:

BOONLAOR, Nanthana / CHUENRUDEEMOL,

- Page 149 and 150:

Who’s who in brazilian design? No

- Page 151 and 152:

SOUZA LEITE, João de vironments. 4

- Page 153 and 154:

Territories of practice: convergenc

- Page 155 and 156:

TEASLEY, Sarah The author(s) of thi

- Page 157 and 158:

TEASLEY, Sarah The author(s) of thi

- Page 159 and 160:

Paradise identity, between projecti

- Page 161 and 162:

Paradise identity, between projecti

- Page 163 and 164:

Politics of fragility in Catalonia:

- Page 165 and 166:

MITRANI, Alex whether on a table to

- Page 167 and 168:

Designing ‘The House of Man’: F

- Page 169 and 170:

MEKINDA, Jonathan solini’s regime

- Page 171 and 172:

‘Swedish Modern’ meets internat

- Page 173 and 174:

HAGSTRÖMER, Denise specially commi

- Page 175 and 176:

Imported design ideas and its sprea

- Page 177 and 178:

CORTÉS, Dannae / CRUZ, Aura / GALL

- Page 179 and 180:

Political Toys: Perón’s gifts fo

- Page 181 and 182:

BENDESKY, Mora Figure 2. Mundo Pero

- Page 183 and 184:

The identity and design of the mode

- Page 185 and 186:

YOSHIMURA, Noriko cles were adopted

- Page 187 and 188:

Lira Popular, chilean broadsheets f

- Page 189 and 190:

MALACCHINI, Simoné pages had been

- Page 191 and 192:

MALACCHINI, Simoné Acknowledgment

- Page 193 and 194:

The signature of Portuguese posters

- Page 195 and 196:

The signature of Portuguese posters

- Page 197 and 198:

From the improvisation to the solut

- Page 199 and 200:

SILVA, Camila Assis Peres / LIMA, G

- Page 201 and 202:

Design of dissent: the multimodal d

- Page 203 and 204:

Figure 6/7/8/9. Glaser: 1997, Olive

- Page 205 and 206:

Design and the street GEIGER, Noni

- Page 207 and 208:

GEIGER, Noni Figure 2. Some spreads

- Page 209 and 210:

GEIGER, Noni Latour, B. 2008. “A

- Page 211 and 212:

Designing new tattoos technology. T

- Page 213 and 214:

Designing new tattoos 5. Conclusion

- Page 215 and 216:

Outside looking in: foreign percept

- Page 217 and 218:

Outside looking in: foreign percept

- Page 219 and 220:

Corporate identity in a global mark

- Page 221 and 222:

SKJERVEN, Astrid of the UK protecto

- Page 223 and 224:

Mapping and analysis possibilities

- Page 225 and 226:

PEREIRA, Fabiano Encourage recognit

- Page 227 and 228:

PEREIRA, Fabiano Figure 8. Filezim

- Page 229 and 230:

Graphic narratives of the domestic

- Page 231 and 232:

SOLóRZANO, Augusto / CORREA-ORTIZ,

- Page 233 and 234:

SOLóRZANO, Augusto / CORREA-ORTIZ,

- Page 235 and 236:

Place branding: graphic design’s

- Page 237 and 238:

CARDOSO, Helder / PERASSI, Richard

- Page 239 and 240:

CARDOSO, Helder / PERASSI, Richard

- Page 241 and 242:

Public information: Design, visibil

- Page 243 and 244:

Here we don’t speak, here we whis

- Page 245 and 246:

MATOS, Sónia interactive phenomena

- Page 247 and 248:

MATOS, Sónia Noë, A. 2004. Experi

- Page 249 and 250:

Modernity boundaries in the process

- Page 251 and 252:

Modernity boundaries in the process

- Page 253 and 254:

Packaging design in Portugal during

- Page 255 and 256:

Packaging design in Portugal during

- Page 257 and 258:

Ocuppy Design: São Paulo and New Y

- Page 259 and 260:

Ocuppy Design: São Paulo and New Y

- Page 261 and 262:

A practical experience on acting lo

- Page 263 and 264:

A practical experience on acting lo

- Page 265 and 266:

The doctrines of Good Taste BÁRTOL

- Page 267 and 268:

BÁRTOLO, Carlos the designed purpo

- Page 269 and 270:

BÁRTOLO, Carlos Rivero, Á. 2010.

- Page 271 and 272:

Between art and Industry The Factor

- Page 273 and 274:

Between art and Industry file of th

- Page 275 and 276:

Transforming territories and forgin

- Page 277 and 278:

Transforming territories and forgin

- Page 279 and 280:

The Belgian participation in the Mi

- Page 281 and 282:

Furnishing the street HERRING, Elli

- Page 283 and 284:

HERRING, Ellie 1963 onwards. There

- Page 285 and 286:

Design promotion in Belgium in the

- Page 287 and 288:

SERULUS, Katarina More concretely,

- Page 289 and 290:

SERULUS, Katarina 1954-1958. Brusse

- Page 291 and 292:

Carmen Miranda, Marca Brasil (Brazi

- Page 293 and 294:

Carmen Miranda, Marca Brasil (Brazi

- Page 295 and 296:

Sweden designed by Ikea ally clear,

- Page 297 and 298:

Sweden designed by Ikea ducers of h

- Page 299 and 300:

Opportunities and challenges for th

- Page 301 and 302:

Opportunities and challenges for th

- Page 303 and 304:

Design as strategy to improve woode

- Page 305 and 306:

NUNES, Viviane / ZURLO, Francesco P

- Page 307 and 308:

The Italian public system supportin

- Page 309 and 310:

MORTATI, Marzia / SIMONELLI, Giulia

- Page 311 and 312:

MORTATI, Marzia / SIMONELLI, Giulia

- Page 313 and 314:

Contributions of design: a tool to

- Page 315 and 316:

Contributions of design: a tool to

- Page 317 and 318:

Contributions of design: a tool to

- Page 319 and 320:

Contributions of design: a tool to

- Page 321 and 322:

Techniques and technologies Paul At

- Page 323 and 324:

A survey on low-income housing rese

- Page 325 and 326:

A survey on low-income housing rese

- Page 327 and 328:

Design of elastic form with paramet

- Page 329 and 330:

LARA, Arthur H. / MAGRI, Paulo H. G

- Page 331 and 332:

LARA, Arthur H. / MAGRI, Paulo H. G

- Page 333 and 334:

Digital personal fabrication: socia

- Page 335 and 336:

Living system design Studio: from d

- Page 337 and 338:

PAIO, Alexandra / OLIVEIRA, Maria J

- Page 339 and 340:

PAIO, Alexandra / OLIVEIRA, Maria J

- Page 341 and 342:

The evolving terrain of the book: A

- Page 343 and 344:

The evolving terrain of the book: A

- Page 345 and 346:

Joining Up: evaluating technologica

- Page 347 and 348:

Joining Up: evaluating technologica

- Page 349 and 350:

Making Space: the future places, to

- Page 351 and 352:

Making Space: the future places, to

- Page 353 and 354:

Designing through the loop: program

- Page 355 and 356:

SILVA-JETTER, Jorge The following e

- Page 357 and 358:

SILVA-JETTER, Jorge importance to n

- Page 359 and 360:

Sewn or Simulated: transformational

- Page 361 and 362:

Sewn or Simulated: transformational

- Page 363 and 364:

The use of ceramics within the sign

- Page 365 and 366:

FERRAZ, Nicoli / ALVAREZ, Cristina

- Page 367 and 368:

FERRAZ, Nicoli / ALVAREZ, Cristina

- Page 369 and 370:

History, Design and technology in t

- Page 371 and 372:

History, Design and technology in t

- Page 373 and 374:

Design for glass: a study of the hi

- Page 375 and 376:

Design for glass: a study of the hi

- Page 377 and 378:

How to supply designers effectively

- Page 379 and 380:

ZITKUS, Emilene / LANGDON, Patrick

- Page 381 and 382:

ZITKUS, Emilene / LANGDON, Patrick

- Page 383 and 384:

Online platforms for the co-Design

- Page 385 and 386:

Online platforms for the co-Design

- Page 387 and 388:

Relationships between Neuroscience

- Page 389 and 390:

Relationships between Neuroscience

- Page 391 and 392:

The voices of the users: how techno

- Page 393 and 394:

ESSI, Kuure / LINDSTRÖM, Antti tec

- Page 395 and 396:

ESSI, Kuure / LINDSTRÖM, Antti Enc

- Page 397 and 398:

Graphic innovations implemented in

- Page 399 and 400:

Graphic innovations implemented in

- Page 401 and 402:

Firebird: Alex Steinweiss’ 78rpm

- Page 403 and 404:

Firebird: Alex Steinweiss’ 78rpm

- Page 405 and 406:

The presence of the autotype techni

- Page 407 and 408:

The presence of the autotype techni

- Page 409 and 410:

The presence of the autotype techni

- Page 411 and 412:

Dutch maps of Pernambuco from the s

- Page 413 and 414:

Dutch maps of Pernambuco from the s

- Page 415 and 416:

Co-ordinated design policy and the

- Page 417 and 418:

PRESTON, David Henrion and Parkin

- Page 419 and 420:

From ‘Do it yourself’ to ‘Ope

- Page 421 and 422:

MALDINI, Irene the stages of creati

- Page 423 and 424:

Contributions of improvisation tech

- Page 425 and 426:

MASSARA, Bruno Based on a deleuzian

- Page 427 and 428:

Human development design centered:

- Page 429 and 430:

FLORES MAGóN Y JIMÉNEZ, Héctor /

- Page 431 and 432:

FLORES MAGóN Y JIMÉNEZ, Héctor /

- Page 433 and 434:

Identity across boundaries. A study

- Page 435 and 436:

Identity across boundaries. A study

- Page 437 and 438:

Digital clothing manufacture: digit

- Page 439 and 440:

Digital clothing manufacture: digit

- Page 441 and 442:

How to go from the file to the fact

- Page 443 and 444:

BARBOSA, Wilson / CELANI, Gabriela

- Page 445 and 446:

Space, information and cosmology in

- Page 447 and 448:

BOECHAT, Marina Pantoja tween ‘ph

- Page 449 and 450:

The new imperialism: the internatio

- Page 451 and 452:

Frontiers of looking past: a Nietzs

- Page 453 and 454:

Frontiers of looking past: a Nietzs

- Page 455 and 456:

Design, histories, empires and peri

- Page 457 and 458:

Design, histories, empires and peri

- Page 459 and 460:

Mythification of national discourse

- Page 461 and 462:

Mythification of National Discourse

- Page 463 and 464:

Mythification of National Discourse

- Page 465 and 466:

Towards a digital batavia: resonanc

- Page 467 and 468:

Towards a Digital Batavia: Resonanc

- Page 469 and 470:

Questionable translatability: theco

- Page 471 and 472:

Questionable translatability: theco

- Page 473 and 474:

Eastern craft in Orientalism and Mo

- Page 475 and 476:

Eastern craft in Orientalism and Mo

- Page 477 and 478:

Mapping Cup & Saucer Design in the

- Page 479 and 480:

Mapping Cup & Saucer Design in the

- Page 481 and 482:

Mappin tells the history of graphic

- Page 483 and 484:

Mappin tells the history of graphic

- Page 485 and 486:

Mappin tells the history of graphic

- Page 487 and 488:

“Go you too to Amazonia”: analy

- Page 489 and 490:

“Go you too to Amazonia”: analy

- Page 491 and 492:

Organic Design, MoMA 1940: the brea

- Page 493 and 494:

Organic Design, MoMA 1940: the brea

- Page 495 and 496:

Modern design meets Latin America:

- Page 497 and 498:

Modern design meets Latin America:

- Page 499 and 500:

Lina Bo Bardi and Aloisio Magalhãe

- Page 501 and 502:

Lina Bo Bardi and Aloisio Magalhãe

- Page 503 and 504:

The graphic translation by the desi

- Page 505 and 506:

The Graphic Translation by the Desi

- Page 507 and 508:

The design of Manoel Bandeira: a hi

- Page 509 and 510:

The design of Manoel Bandeira: a hi

- Page 511 and 512:

Open strand Victor Margolin / Chair

- Page 513 and 514:

Brazilian Graphic Design in the ‘

- Page 515 and 516:

Brazilian Graphic Design in the ‘

- Page 517 and 518:

The Design of book bovers in Brazil

- Page 519 and 520:

The Design of book bovers in Brazil

- Page 521 and 522:

The design of Fred Jordan With his

- Page 523 and 524:

The design of Fred Jordan Figure 2.

- Page 525 and 526:

Domestic technologies and moderniza

- Page 527 and 528:

Domestic technologies and moderniza

- Page 529 and 530:

la escuela de Artes y Oficios de sa

- Page 531 and 532:

CAsTillO, eduardo The author(s) of

- Page 533 and 534:

Itineraries for a Design Culture in

- Page 535 and 536:

FARKAS, Mónica / STERLA, Mauricio

- Page 537 and 538:

Sertanejo Art Deco: an inspiration

- Page 539 and 540:

SOUZA, José Marconi B. de / ROSSI,

- Page 541 and 542:

SOUZA, José Marconi B. de / ROSSI,

- Page 543 and 544:

Souza, José Marconi B. de / Rossi,

- Page 545 and 546:

Architectural lettering: from infor

- Page 547 and 548:

Architectural lettering: from infor

- Page 549 and 550:

A dialogue between art and city thr

- Page 551 and 552:

HANNS, Daniela Kutschat / DE MARCHI

- Page 553 and 554:

Vernacular design: a discussion on

- Page 555 and 556:

Vernacular design: A discussion on

- Page 557 and 558:

Italian Radicals and Dutch conceptu

- Page 559 and 560:

Italian Radicals and Dutch Conceptu

- Page 561 and 562:

Italian Radicals and Dutch Conceptu

- Page 563 and 564:

Art criticism and the semantic cons

- Page 565 and 566:

Art criticism and the semantic cons

- Page 567 and 568:

Interieur Kortrijk, an edu-commerci

- Page 569 and 570:

Interieur Kortrijk, an edu-commerci

- Page 571 and 572:

The story of convertible Sofa-Bed:

- Page 573 and 574:

MERZALI CELIKOGLU, Ozge / ER, Alpay

- Page 575 and 576:

MERZALI CELIKOGLU, Ozge / ER, Alpay

- Page 577 and 578:

Vapourware and the agency of ideas

- Page 579 and 580:

Vapourware and the Agency of Ideas

- Page 581 and 582:

Pre-Columbian Asceticism: the Tuza-

- Page 583 and 584:

Pre-Columbian Asceticism. The Tuza-

- Page 585 and 586:

The collection of textbooks “Tape

- Page 587 and 588:

RAMIL, Chris standards for the layo

- Page 589 and 590:

“Their pen draws everything, as i

- Page 591 and 592:

Diniz, Kollontai The author(s) of t

- Page 593 and 594:

Diniz, Kollontai The author(s) of t

- Page 595 and 596:

Cruzeiro Novo Project: Design and t

- Page 597 and 598:

Cruzeiro Novo Project: Design and t

- Page 599 and 600:

Design for a sustainable culture Fi

- Page 601 and 602:

Design for a sustainable culture th

- Page 603 and 604:

Design for a sustainable culture al

- Page 605 and 606:

Design and biodiversity: the produc

- Page 607 and 608:

Design and biodiversity: the produc

- Page 609 and 610:

Lightness and beauty in furniture d

- Page 611 and 612:

Lightness and beauty in furniture d

- Page 613 and 614:

About ICDHS / The International Com

- Page 615 and 616:

Emmanuel Ruffo / Institute for Arch