PDF: DISCONTINUOUS FILMS - Film Studies Association of Canada

PDF: DISCONTINUOUS FILMS - Film Studies Association of Canada

PDF: DISCONTINUOUS FILMS - Film Studies Association of Canada

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

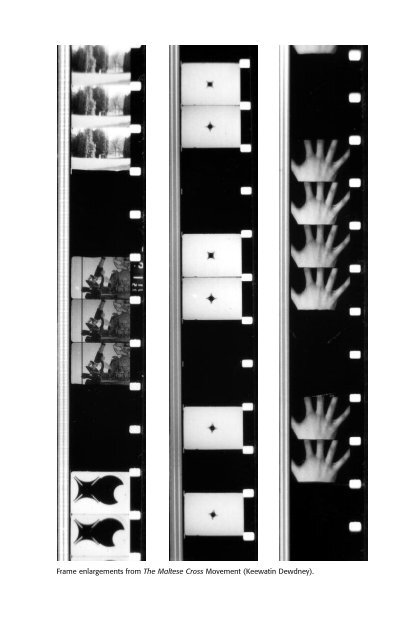

Frame enlargements from The Maltese Cross Movement (Keewatin Dewdney).

CINÉ-DOCUMENTS<br />

KEEWATIN A. DEWDNEY<br />

DISCONTI N UOUS FI LMS<br />

Résumé: Ce document inédit de 1967 reflète non seulement l’esprit novateur de<br />

l’avant-garde des années soixantes, mais fait aussi la promotion d’une nouvelle<br />

esthétique cinématographique basée sur la mécanique du projecteur.<br />

Editor’s Note: This document, which exists only in mimeographed form (and is produced<br />

here in its original form—including typographical and spelling errors), was written<br />

in 1967, while Keewatin Dewdney was a graduate student in mathematics at the<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Michigan. In the late sixties and early seventies Dewdney also made several<br />

short experimental films, three <strong>of</strong> which are still in distribution. 1 In 1968 he<br />

returned to <strong>Canada</strong> to take a position in the Computer Science Department at the<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Western Ontario, where he is now an Emeritus Pr<strong>of</strong>essor.<br />

“Discontinuous <strong>Film</strong>s” not only reflects the spirit <strong>of</strong> exploration and innovation<br />

that characterized North American experimental/avant-garde/underground film <strong>of</strong><br />

the 1960s, but also identifies a particular development in avant-garde filmmaking<br />

that was just beginning to be recognized. While clearly inspired by Tony Conrad’s The<br />

Flicker (USA, 1966), Dewdney’s essay/manifesto <strong>of</strong>fers insights and arguments that<br />

go beyond the significance <strong>of</strong> “flicker effects.” It <strong>of</strong>fers, in effect, a new aesthetics <strong>of</strong><br />

cinema based on the mechanical operation <strong>of</strong> the movie projector.<br />

Although sporadic experiments in discontinuous film appear in a few early<br />

experimental films, an identifiable “school” or “movement” <strong>of</strong> discontinuous films<br />

only emerged in the 1960s. In addition to The Flicker and Dewdney’s own masterwork,<br />

Maltese Cross Movement (USA, 1967), notable examples include Peter<br />

Kubelka’s Schwechater (Austria, 1958) and Arnulf Rainer (Austria, 1960), Robert<br />

Breer’s Blazes (USA, 1961) and Fist Fight (USA, 1964), Pierre Hébert’s Op Hop–Hop<br />

Op (<strong>Canada</strong>, NFB, 1966) and Autour de la perception (<strong>Canada</strong>, NFB, 1968), Keith<br />

Rodan’s Cinetude 2 (<strong>Canada</strong>, 1969), Beverly and Tony Conrad’s Straight and<br />

Narrow (USA, 1970), and a series <strong>of</strong> stunning flicker films by Paul Sharits: Ray Gun<br />

Virus (USA,1966), Piece Mandala/End War (USA, 1966), N:O:T:H:I:N:G (USA,1968),<br />

and T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (USA,1968). 2<br />

CANADIAN JOURNAL OF FILM STUDIES • REVUE CANADIENNE D’ÉTUDES CINÉMATOGRAPHIQUES<br />

VOLUME 10 NO. 1 • SPRING • PRINTEMPS 2001 • pp 96-105

98 Volume 10 No. 1<br />

<strong>DISCONTINUOUS</strong> <strong>FILMS</strong><br />

1. The Flicker<br />

Tony Conrad’s The Flicker is a raw, archetypal<br />

statement about the nature <strong>of</strong> film, a<br />

statement which few understood. The Flicker<br />

revealed at one stroke that the projector, not<br />

the camera, is the film-maker’s true medium.<br />

This is not to say film-makers are unaware <strong>of</strong><br />

the projector and screen, the movie-house environment<br />

(they must learn to visualize a screen<br />

in the viewfinder <strong>of</strong> their camera). But this<br />

does say that the very use <strong>of</strong> the camera as a<br />

film-making tool has imposed the assumption <strong>of</strong><br />

continuity on film, an assumption entirely foreign<br />

to the projector. Yet continuity has hypnotized<br />

both Hollywood and the experimental<br />

almost equally.<br />

For some reason, we are now released from<br />

continuity. Warhol fulfills a very important<br />

satiric function in pushing the continuous scene<br />

to its outer limits. This is why his films possess<br />

a drollity beyond their subject matter.<br />

It’s like saying “Here’s continuity, Jack!”<br />

Camera Vs. Projector<br />

During the 18 th and 19 th centuries, a great<br />

deal <strong>of</strong> energy was expanded in a search for<br />

“moving pictures”. Some <strong>of</strong> these were: phantasmagorias,<br />

peepshows, dioramas, magic lantern<br />

shows, phenakisticopes, viviscopes, chronophotographs,<br />

kinetoscopes, etc. The great majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> these devices sought a direct translation <strong>of</strong><br />

some image or series <strong>of</strong> images into a moving<br />

picture. The emphasis was clearly on the theatrical<br />

environment, the release <strong>of</strong> light. With<br />

Marey’s Rifle-Camera (1882) we have the true

precursor <strong>of</strong> the modern movie camera and the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> a great split in the capture <strong>of</strong><br />

light (camera) and its release (projector). With<br />

photography it had become possible to make<br />

instant pictures and only a few more instants<br />

would be required to make a continuous run <strong>of</strong><br />

pictures. It was in building the projector that<br />

the late 19 th and early 20 th Century built better<br />

than it knew. For, ideally suited as it is to<br />

the projection <strong>of</strong> whatever the motion picture<br />

camera photographs, the projector is a MACHINE<br />

CAPABLE OF PROJECTING TWENTY FOUR TRANSPARENCIES<br />

IN SEQUENCE EVERY SECOND.<br />

The motion picture camera is quite limited<br />

in function. Generally speaking, it gathers<br />

light onto a sequence <strong>of</strong> frames in rapid order;<br />

it manufactures only continuous scenes; it will<br />

display whatever is put into it and is completely<br />

unlimited in the environment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

frame.<br />

We are now in the process <strong>of</strong> being released<br />

from the assumption <strong>of</strong> continuity and the cinematic<br />

schools this assumption has imposed.<br />

Delightful as it has been, continuity has given<br />

us little more than a visual re-hash <strong>of</strong> the literary<br />

experience (poems included). Anyone<br />

objecting violently to this statement surely has<br />

a big stake in continuous cinema. The same person<br />

will feel enormously threatened by discontinuous<br />

film. At the Fourth Ann Arbor <strong>Film</strong><br />

Festival last year, many in the auditorium<br />

groaned during The Flicker, not bored but<br />

frightened.<br />

An Experiment<br />

The sort <strong>of</strong> Insight provided by William M.<br />

Ivins and Marshall McLuhan is particularly valu-<br />

CJFS • RCEC 99

able when applied to the projector’s environment.<br />

For example, Ivins, by isolating a sense<br />

in Art and Geometry is able to make the most<br />

obvious statements about touch and yet draw the<br />

most amazing conclusions from them. (Greek temples<br />

look the way they do because they are<br />

appreciated by the ‘hand’ and not the ‘eye’.)<br />

In a room is a projector and screen. People<br />

who have never seen a projector (or camera)<br />

before are brought into the room, given cans <strong>of</strong><br />

clear and dark leader, editing tools, paint,<br />

bleach, whatever one may think <strong>of</strong>. They are told<br />

only that in a years time we want to see some<br />

interesting films.<br />

After projecting the various kinds <strong>of</strong> leader,<br />

our people become bored. To be less bored they<br />

would begin to make marks on the leader. Yes,<br />

much better. They would not be very likely to<br />

animate because animation grows out <strong>of</strong> a consciousness<br />

<strong>of</strong> the camera. This means a rapid<br />

appearance on the screen <strong>of</strong> designs flashing by<br />

at subliminal speeds. If our people were all<br />

intelligent, creative, etc., one would see at<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the year a more exciting collection<br />

<strong>of</strong> films than at Cannes, New York, Ann Arbor or<br />

anywhere. If they ultimately invented a camera,<br />

continuous run would be regarded as a ‘gimic’ on<br />

theirs, just as single frame is on ours.<br />

Hopefully, this conceptual experiment has<br />

placed the reader outside his familiar film<br />

environment long enough to realize the tyrrany<br />

<strong>of</strong> the motion picture camera.<br />

The logical result <strong>of</strong> using a camera in filming<br />

is the use <strong>of</strong> the splicer. Splices used to<br />

bother a good many people, that is, not the<br />

appearance <strong>of</strong> splice-bars on the screen but the<br />

100 Volume 10 No. 1

sudden cut from one continuous scene to the<br />

next. It bothered people because here, for one<br />

fraction <strong>of</strong> a second, the true power <strong>of</strong> the projector<br />

was revealed. The cuts were bandaged with<br />

dissolves. Considering how much more expensive a<br />

dissolve is, it really is amazing that filmmakers<br />

(including Hollywood) ever used them, the<br />

conventions that came to be associated with dissolvers<br />

(time passing, place changing) have<br />

nothing to do with their true function. Splices<br />

do not bother people like Conrad who spend most<br />

<strong>of</strong> a year doing them for The Flicker or Brakhage<br />

who admits “one whale <strong>of</strong> an aesthetic involvement<br />

in The Splice”. 3 This shows a healthy attitude<br />

toward the motion picture camera, described<br />

by Brakhage as a light-gathering instrument.<br />

Conrad could really have done without it entirely<br />

(like our people in the room). For if continuity<br />

is a corollary to the camera, an aesthetic<br />

use <strong>of</strong> splices is far removed from the continuous<br />

scene mentality.<br />

The Flicker is the <strong>Film</strong><br />

Many film-makers have begun to show a healthy<br />

interest in discontinuity, even though sometimes<br />

more than degree (namely insight) separates a<br />

film like Vanderbeek’s Breathdeath from The<br />

Flicker. Breathdeath, in no detectable rhythm,<br />

lays down an exciting barrage <strong>of</strong> visuals. Some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the scenes probably get down to 6 frames or<br />

so, though prolongued use <strong>of</strong> shorter scenes is<br />

certainly lacking. Bienstock, last year, with<br />

Nothing Happened This Morning used a series <strong>of</strong><br />

very rapid zooms from many angles at once on a<br />

single action, giving one a sense <strong>of</strong> simultaneity<br />

and seeing the action (in this case, a young<br />

man punching out an alarm clack) from all directions<br />

at once. This year with Brummer’s he is<br />

clearly on the trail <strong>of</strong> the discontinuous cine-<br />

CJFS • RCEC 101

ma. In a restaurant a couple converse while the<br />

camera on a trip <strong>of</strong> its own, explores them and<br />

the restaurant interior with very fast, sharp<br />

scenes, none <strong>of</strong> them subliminal but all contributing<br />

to a sense <strong>of</strong> hurried excitement about<br />

the restaurant. Bang bang bang. The NFB’s Norman<br />

McLaren and Arthur Lipsett, though from quite<br />

different traditions, show an awareness <strong>of</strong> discontinuous<br />

film. McLaren in Blankety Blank, a<br />

somewhat older production than these others,<br />

uses a very short subliminal sequence and hues<br />

from frame to frame, giving one a floating sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> ‘lost’ beauty. Arthur Lipsett’s Free Fall and<br />

Very Nice Very Nice are clean, documentary versions<br />

<strong>of</strong> Breathdeath from the point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong><br />

scene length and content.<br />

A changing sense <strong>of</strong> the function <strong>of</strong> the camera<br />

can be attributed to Fat Feet by Red Grooms<br />

and others, in which, against a pasteboard<br />

facade <strong>of</strong> city, people act out stock roles as<br />

drunks, firemen, prostitutes, etc., all <strong>of</strong> them<br />

wearing enormous cardboard shoes. The technique<br />

is stop-motion and the jerky, uneven movements<br />

<strong>of</strong> the actors give the picture a nervous, hysterical<br />

quality. One hopes that a great talent<br />

like Larry Jordan will begin to explore discontinuity<br />

because he is naturally equipped, as an<br />

animator, to do it. 4<br />

To postulate the existence <strong>of</strong> a kind <strong>of</strong> film<br />

which as yet publicly exists in one example<br />

alone would seem foolish were it not for the<br />

very clearly detectable trend toward shorter and<br />

shorter scenes, more and more discontinuous. For<br />

convenience we will call this kind <strong>of</strong> film, a<br />

Flicker <strong>Film</strong>, recalling that during the 20’s<br />

films did flicker, and that in one sense at<br />

least, the flicker is more important than the<br />

film.<br />

102 Volume 10 No. 1

Description and Techniques<br />

The discontinuous or flicker film will<br />

replace Conrad’s blacks and whites with dark and<br />

light images. Subliminal runs (lengths <strong>of</strong> film<br />

in which the image changes entirely from frame<br />

to frame (will come into their own as an<br />

aesthetic device. A kind <strong>of</strong> visual (or even<br />

audiovisual) grammar will be built up within<br />

each film. Hypermontage. Sound will take on an<br />

entirely new dimension – no longer a slave to<br />

the continuous scene, it will cease to act as a<br />

radio or phonograph and mesh with the visual<br />

component <strong>of</strong> the film in a way never before<br />

imagined.<br />

As an example <strong>of</strong> this kind <strong>of</strong> film, Gerard<br />

Malanga was recently filmed both reading poetry<br />

and dancing. 5 The sounds (reading and music)<br />

were recorded on 1/4” tape and transferred to 16<br />

m.m. sound stock. Both the reading and dancing<br />

scenes lasted 2 1/2 minutes (one hundred feet <strong>of</strong><br />

film each) and the original film was painted<br />

with black acetate ink on the base side in the<br />

follownng manner. First, 24 frames reading, then<br />

24 frames black, 23 frames reading, 23 frames<br />

black, down to a frame <strong>of</strong> each. Alternate frames<br />

were blackened for nearly a full minute after<br />

this, after which the blackened frames occurred<br />

in twos, then in threes, various distances<br />

apart. The other film (dancing) was painted in<br />

complementary fashion so that when the two films<br />

were A and B rolled onto one print, one simply<br />

had an alternation from one scene to the other,<br />

an alternation whose speed was governed by how<br />

close together blackened frames were put in the<br />

original. The 16 m.m. sound track was cut so<br />

that sounds would confirm to action right down<br />

to the frame. The result was a highly interesting<br />

study <strong>of</strong> simultaneity. The effect one might<br />

CJFS • RCEC 103

think, would be <strong>of</strong> double exposure, but it does<br />

not work this way at all. A powerful technique.<br />

Since disparate images being flashed 24 per<br />

second on a screen are almost entirely lost on<br />

the viewer in his normal conscious state, it<br />

would certainly help if they had been seen<br />

before. This means starting such a film with one<br />

or more key images which by the increasing complexity<br />

<strong>of</strong> their context as the film progresses,<br />

heighten the value <strong>of</strong> the image. Somewhere after<br />

this, (one should pay close attention to the<br />

build up <strong>of</strong> pace in The Flicker) we begin subliminal<br />

runs which to someone just walking into<br />

the theatre may be meaningless but which to the<br />

clued-in audience are working a special magic<br />

all their own. Sound, working with image, does<br />

not merely “fill-in” the ear, but links it to<br />

the eye to an almost sensuous extent.<br />

Persistence <strong>of</strong> Vision.<br />

104 Volume 10 No. 1<br />

Keewatin Dewdney<br />

(1967)

NOTES<br />

Many thanks to Keewatin Dewdney for permitting this document to be published here, and<br />

for providing some background information. Thanks, too, to Scott MacKenzie who suggested<br />

that Dewdney’s essay be published as a “ciné-document.”<br />

1. The Canadian <strong>Film</strong>makers Distribution Centre distributes Dewdney’s films, Sissors (USA,<br />

1966), The Maltese Cross Movement (USA, 1967), and Wildwood Flower (<strong>Canada</strong>,<br />

1971).<br />

2. For a more extensive discussion <strong>of</strong> Maltese Cross Movement and some other examples<br />

<strong>of</strong> discontinuous film see, William C. Wees, “The Apparatus and the Avant-Garde,” in<br />

<strong>Film</strong> and the Future, special supplement to Cinema <strong>Canada</strong> 97 (June 1983): 41-46.<br />

3. Stan Brakhage, “Letter from Brakhage: On Splicing,” <strong>Film</strong> Culture 35 (Winter 1964-65):<br />

36; reprinted in Stan Brakhage, The Moving Picture Giving and Taking Book (West<br />

Newbury, MA: Frontier Press, 1971), 23-40, and Stan Brakhage, Brakhage Scrapbook:<br />

Collected Writings (New Palz, NY: Documentext,1982), 62-68.<br />

4. By the time “Discontinuous <strong>Film</strong>s” was written, the American experimental filmmaker,<br />

Larry Jordan, had made several cut-out/collage animation films including, Duo<br />

Concertantes (1964), Gymnopedies (1965), and Hamfat Asar (1965). More were to follow,<br />

but that they satisfy Dewdney’s criteria for discontinuous films is debatable.<br />

5. Dewdney is referring to his own film, Malanga (1967), no longer in circulation.<br />

FILMOGRAPHY<br />

Blinkety Blank (<strong>Canada</strong>, NFB, 1955, Norman McLaren)<br />

Breathdeath (USA, 1964, San Vanderbeek)<br />

Brummer’s (USA, 1967, David Bienstock)<br />

Fat Feet (USA, 1966, Red Grooms)<br />

The Flicker (USA, 1966, Tony Conrad)<br />

Free Fall (<strong>Canada</strong>, NFB, 1964, Arthur Lipsett)<br />

Nothing Happened This Morning (USA, 1965, David Bienstock)<br />

Very Nice, Very Nice (<strong>Canada</strong>, NFB, 1961, Arthur Lipsett)<br />

CJFS • RCEC 105

106 Volume 10 No. 1