WILD YAM Dioscorea villosa L - Frostburg State University

WILD YAM Dioscorea villosa L - Frostburg State University

WILD YAM Dioscorea villosa L - Frostburg State University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>WILD</strong> <strong>YAM</strong> <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong> L.<br />

1. Taxonomy<br />

<strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong> L.<br />

<strong>Dioscorea</strong> is a widely distributed genus with well over 600 species worldwide.<br />

Family: <strong>Dioscorea</strong>ceae<br />

Common names: Wild yam, colic root, rheumatism root<br />

Synonyms: The Plant List (2010) names numerous synonyms including D. quaternata Walter<br />

and D. hirticaulis Bartlett.<br />

Other North American species include D. floridana Bartlett and D. mexicana Scheidw. D.<br />

batatas Decne. - a native of China - is occasionally found escaped from cultivation. D.<br />

quaternata was previously described as a separate species (Gleason & Cronquist 1991), however<br />

it is now regarded as synonymous with D. <strong>villosa</strong> (The Plant List, 2010).<br />

1

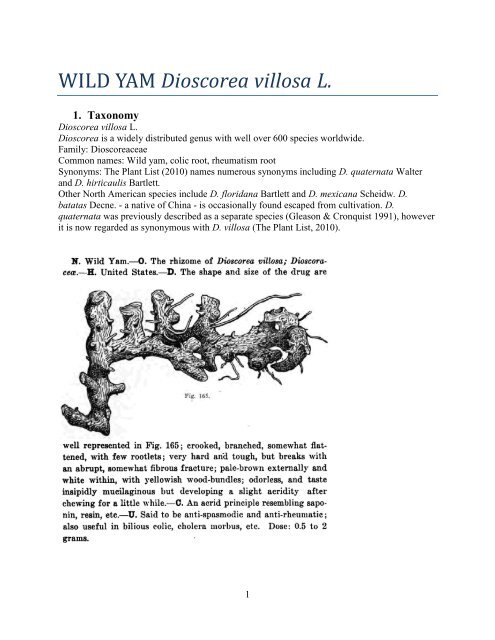

Figure 1. Image from Handbook of Pharmacognosy by Otto A. Wall 1917. C.V. Mosby Co., St.<br />

Louis.<br />

2. Botanical description and distribution<br />

D. <strong>villosa</strong> is a deciduous perennial herbaceous twiner that grows counterclockwise over small<br />

and medium-size shrubs. The upper leaves are alternate, heart-shaped and shiny with long<br />

petioles, entire margins, prominent veins and acuminated apices. The lowermost leaves are<br />

usually arranged in whorls. The plants are dioecious. Small staminate (male) flowers are white<br />

and perfumed, and arranged in panicles, while carpelate (female) plants produce small solitary<br />

flowers at the leaf nodes. The fruit is a membraneous 3-valved capsule with one or two<br />

chocolate-colored winged seeds in each locule (Albrecht, 2006). The long, cylindrical seldom<br />

branched rhizomes grow to 5-10 mm in diameter, with numerous tough, slender roots attached<br />

underneath.<br />

Distribution: Eastern USA, most common in the central and southern regions, wet woodlands<br />

from Connecticut-Tennessee, Texas-Minnesota. It prefers moist open woods, thickets and<br />

roadsides (Gleason & Cronquist, 1991).<br />

Part Used<br />

Dried rhizome and roots<br />

Note: In alignment with the traditional literature, this monograph may use the term “root” to<br />

imply both root and rhizome.<br />

3. Traditional uses<br />

Traditional uses in Appalachia<br />

D. <strong>villosa</strong> is found all over the Appalachian region, and is a popular herbal remedy for pains<br />

associated with rheumatism and arthritis, colic and intestinal cramps, proving itself a reliable<br />

antispasmodic and anti-inflammatory (Howell, 2006). Of all remedies, it is the most effective in<br />

the treatment of bilious colic, as well as being a useful treatment for rheumatism (Crellin &<br />

Philpott, 1990).<br />

Other traditional uses<br />

Native American use<br />

D. <strong>villosa</strong> was most commonly used by Native Americans to help relieve labor pains at the time<br />

of delivery (Moerman, 1998). Otherwise it was not widely used, possible as the rhizome is quite<br />

hard and unpalatable as food (Cech, 2000), unlike some other species of yam.<br />

Folklore & Home<br />

Warren (1859) encouraged the home use of D. <strong>villosa</strong> for nausea and spasms during pregnancy,<br />

as well as for the treatment of bilious colic. Gunn (1859) recommended making a decoction of<br />

one ounce of powder in one quart of boiling water to be taken every half hour in doses of “one<br />

half to a tea cup full” until intestinal cramping is relieved. He also suggests using the tincture in<br />

doses of one half to a full teaspoon, however it is implied that this is an uncommon form of use.<br />

Salter (1877) encouraged the liquid extract in doses of one teaspoon every five minutes until<br />

relaxation [of intestines] is perfect. Meader (1861) recommended the tincture of D. <strong>villosa</strong> as an<br />

2

expectorant.<br />

Physiomedical<br />

Physiomedicalist W. Cook (1869) used a warm infusion of the root of D. <strong>villosa</strong> as a relaxant to<br />

ease nervous excitement and muscular tension, relieving gas and pains of the bowels. He also<br />

used the root as a remedy for female reproductive troubles such as “painful menstruation,<br />

neuralgia of the womb, vomiting during gestation and the painful knottings of the uterus incident<br />

to the latter stages of pregnancy…as well as labor pains and after pains” (Cook, 1869).<br />

Eclectic<br />

Eclectic physician John Fyfe (1909) considered D. <strong>villosa</strong> an excellent remedy for all manner of<br />

gut conditions, from the intestines to the liver to the gallbladder, claiming that it relieved<br />

“hepatic congestion”. He stated D. <strong>villosa</strong> was “directly curative” of colicky conditions, as well<br />

as useful in the treatment of gallstones and in nausea accompanying pregnancy. Ellingwood<br />

(1919) also accounted for a broad range of uses of D. <strong>villosa</strong> including treatment of both bilious<br />

colic and female reproductive disorders. He described it as an anodyne, claiming D. <strong>villosa</strong><br />

relieved spasms and pains almost immediately, and suggested that if no relief was felt within two<br />

hours that use should be discontinued. Regarding its use as a female reproductive tonic he<br />

explained, “In neuralgic dysmenorrhea, in ovarian neuralgia, in cramp like pains in the uterus at<br />

any time and in sever after pains it often acts satisfactory, quickly relieving the muscular spasm”.<br />

Moore (1930) reiterated Ellingwood‟s claims that D. <strong>villosa</strong> acted as a reproductive remedy<br />

saying that it was an excellent treatment for afterpains and spasmodic dysmenorrhea (Moore,<br />

1930).<br />

Regulars<br />

Dr. Paine (1874) related accounts of fellow practitioners and their successes and/or failures in<br />

using specific drugs. According to Paine, Henry Summers, a practicing family physician, was<br />

extremely successful in using D. <strong>villosa</strong> to address the symptoms of bilious colic and “any other<br />

portions affected by the nervous system”. The initial treatment was given to a forty-year-old<br />

woman “laboring under a severe form of affection for three days…” (Paine 1874). The second<br />

dose relieved the violence of the paroxysm and in two hours the vomiting and pain had been<br />

entirely controlled although there was gastric and enteric inflammation for several days.” Paine<br />

also stated the extract preparation was successful in treating various forms of neuralgia, spine,<br />

brain, and uterine complaints (Paine, 1874).<br />

4. Scientific Research<br />

Phytochemistry<br />

Steroidal saponins<br />

During the 1930s Japanese investigators first discovered the saponin disogenin from an oriental<br />

yam (D. tokoro) (Fujii & Matsukawa, 1936). Subsequently Russell Marker and co-workers from<br />

Pennsylvania <strong>State</strong> College conducted extensive investigations into the chemistry and<br />

biosynthesis of steroidal compounds from natural sources, in the process several saponins were<br />

isolated and identified from North American species of the Liliaceae and Dioscoraceae families<br />

(Marker, Turner, Shabica, et al., 1940), including diosgenin from D. <strong>villosa</strong> (Marker, Turner, &<br />

3

Ulshafer, 1940). Marker also described methods for conversion of diosgenin into testosterone<br />

and other steroids (Marker, 1940), ultimately leading to synthesis of cortisol and contraceptives.<br />

A major screening program revealed that well over 100 species of the <strong>Dioscorea</strong> genus contained<br />

the sapongenin diosgenin (Martin, 1969). Since then dozens of glycosides based on the steroidal<br />

aglycone structure of diosgenin have been identified, and these are classified as either<br />

furanospiral or spirostanol depending on whether the „f-ring‟ is open or closed (Sautour, Mitaine-<br />

Offer, & Lacaille-Dubois, 2007). All these saponins are hydrolyzed in vivo by intestinal bacteria,<br />

thus releasing the active constituent diosgenin.<br />

Rha<br />

Glc<br />

Rha<br />

O<br />

Dioscin from <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong><br />

O<br />

O<br />

Figure 2. Structure of dioscin, a spirostanel saponin.<br />

Figure reproduced from The Constituents of Medicinal Plants (Pengelly, 2004).<br />

Sautour and co-workers have reported six saponins for D. <strong>villosa</strong>: protodioscin, ME<br />

protodioscin, parrisaponin, dioscin, progenin III (= prosapogenin A of dioscin) and progenin II<br />

(Sautour, Miyamoto, & Lacaille-Dubois, 2006; Sautour et al., 2007). Using H, C and 2D NMR<br />

spectroscopy Hayes et al. (2007) identified four major and three minor steroidal saponins in<br />

quantitative terms. The major saponins (none of which were reported by Santora et al.) included<br />

two furanostanol types - methyl parvifloside and protodeltonin - as well as two spirostanol types<br />

– deltonin and glucosidodeltonin. The furostanol saponins were the most common constituent in<br />

autumn harvested samples whereas the spirostanol saponins were predominant in summer<br />

harvested material. The minor saponins (which were reported by Sautour) were<br />

methylprotodioscin, disoscin and prosapogenin A of diosgenin (Hayes et al 2007). Morgan<br />

(2011) notes that some commercial extracts are standardized to diosgenin rather than dioscin,<br />

and that such extracts may be derived from other species (eg Chinese yam, D. oppositifolia L.)<br />

which may lack the full chemical profile of D. <strong>villosa</strong>.<br />

Another spirostanol saponin, not previously identified in <strong>Dioscorea</strong> spp., was recently isolated<br />

using preparative HPLC (Hu, Lin, Liu, & Yang, 2007).<br />

Table 1. Classification of major diosgenin based saponins in D. <strong>villosa</strong><br />

SPIROSTANOL<br />

Dioscin<br />

Parrisaponin<br />

4

Prosapogenin A of dioscin (progenin III)<br />

progenin II<br />

Deltonin<br />

Glucosidodeltonin (Zingiberensis I)<br />

FURANOSTANOL<br />

Protodioscin<br />

Methyl protodioscin<br />

Methyl parvifloside<br />

Methyl protodeltonin<br />

Flavonoids<br />

Two flavan-3-ol glycosides have been isolated from D. <strong>villosa</strong> (Sautour, Miyamoto, Lacaille-<br />

Dubois, 2006)<br />

Other constituents<br />

Other constituents identified include phytosterols (sitosterol, stigmasterol, taraxerol), the alkaloid<br />

dioscorine, tannins, starch, vitamins b and c, beta carotene and minerals (Braun & Cohen, 2010).<br />

Pharmacology<br />

Hormonal effects<br />

Most of the biomedical research associated with the species is based on the activity of dioscin<br />

and diosgenin. Despite the fact that the molecule can be converted to hormones such as<br />

progesterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) by several enzymatic steps in the laboratory,<br />

there is conflicting evidence as to whether diosgenin has prostergenic activity in itself, and<br />

attempts to market it as such have been dubbed by some “the wild yam scam” (Foster &<br />

Johnson, 2006). However, estrogenic action on the mammary epithelium of ovariectomized mice<br />

has been reported (Aradhana, Rao, & Kale, 1992), while other studies have provided mixed<br />

results (Zava, Dollbaum, & Blen, 1998). In one study diosgenin was able to protect the kidneys<br />

of rats from morphological changes associated with ovariectomy, posited as occurring due to<br />

conversion of diosgenin to progesterone in vivo (Tucci & Benghuzzi, 2003). However any direct<br />

hormonal effect that can be attributed to D. <strong>villosa</strong> is in fact estrogenic (Morgan, 2011).<br />

When postmenopausal women were given diosgenin-containing edible yam (D. alata) as 30% of<br />

their diet for 30 days they had increases in serum estrogens and decreases in serum androgen<br />

levels (Wu, Liu, Chung, Jou, & Wang, 2005). A couple of recent studies focusing on<br />

5

osteoporosis and bone formation have investigated the possible interrelationship between<br />

diosgenin and steroid hormones.<br />

Osteogenesis<br />

Studies based on ovariectomized rat models compared treatments between diosgenin and DHEA<br />

and found they behaved in a similar fashion (Scott, Higdon, et al., 2000). In ovariectomyinduced<br />

osteoporosis, diosgenin along with DHEA and estrogen were all found to reduce bone<br />

loss in the rats (Higdon, Scott, et al., 2001). In an in vitro study, diosgenin upregulated the<br />

growth-factor VEGF-A, and promoted angiogenesis through activation of the protein HIF-1 via<br />

estrogen-dependent signaling pathways (Yen et al., 2005). Subsequently the osteogenic (as<br />

distinct from “estrogenic”) effect of diosgenin has been linked to enhancement of Type 1<br />

collagen, alkaline phosphatase and other bone marker proteins in osteoblastic cells (Alcantara et<br />

al., 2011.)<br />

Antiproliferative effects<br />

Numerous studies have demonstrated some cytotoxic activity by diosgenin and its glycosides<br />

(Hu, Lin, Liu, & Yang, 2007; Sautour et al., 2007). In cell culture studies diosgenin<br />

demonstrated antiproliferative effects through cell cycle arrest, apoptosis induction via<br />

mechanisms that appear to involve nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) induction and prostaglandin E2<br />

synthesis (Moalic et al., 2001). Subsequent studies showed that diosgenin inhibited<br />

osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of NF-κB regulated gene expression, while potentiating<br />

apoptosis induced both by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and two chemotherapy drugs (Shishodia<br />

& Aggarwal, 2005). Diosgenin also inhibited growth of human colon carcinoma cells in dose<br />

dependent manner, via a mechanism involving suppression of HMG-CoA reductase enzyme<br />

associated with cholesterol biosynthesis (Raju & Bird, 2007). In a recent anti-cancer screening<br />

program using malignant neuroblastoma cells, D. <strong>villosa</strong> extract was found to have the strongest<br />

tumoricidal activity of 374 herbal extracts tested (Mazzio & Soliman, 2009).<br />

Heptatoprotective and Cardiovascular Effects<br />

An in vivo study on rat models showed that supplementation with 0.5% diosgenin while on a<br />

high cholesterol diet provided a hepatoprotective effect on the high oxidative stress of the diet,<br />

and also an elevated HDL cholesterol level by 1.5 times compared with the control group (Son et<br />

al., 2007). A significantly lower liver cholesterol level was observed with a 7 fold increase in<br />

biliary cholesterol secretion, suggesting that diosgenin may be a promising treatment for<br />

reducing the progression of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease (Son et al., 2007).<br />

Antifungal effects<br />

Steroidal saponins are considered to be an important source of antifungal agents, and numerous<br />

glycosides of diosgenin – including three spirostane saponins found in D. <strong>villosa</strong> – actively<br />

inhibit Candida albicans and other human pathogenic yeasts in vitro (Sautour et al., 2007).<br />

Anti-inflammatory activity<br />

Few studies are available, however there is evidence of lipoxygenase inhibition in vitro (Nappez,<br />

Liagre, & Beneytout, 1995) and some reported regulation of cyclooxygenase expression (Moalic<br />

et al., 2001).<br />

6

Clinical studies<br />

In a double blind cross-over study of 23 women with „troublesome‟ menopausal sysmptoms,<br />

there was no difference in symptoms between the group using a wild yam cream based on D.<br />

<strong>villosa</strong> and the placebo group following three months of treatment ( Komesaroff, Black, Cable,<br />

& Sudhir, 2009).<br />

5. Modern Phytotherapy<br />

Modern therapeutic use of D. <strong>villosa</strong> reflects pharmacological research and traditional<br />

indications. Naturopathic uses include spasmodic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract and<br />

associated colicky pain as well as the spasmodic pain of dysmenorrhea (Kuts-Cheraux, 1953).<br />

Volume two of the British Herbal Compendium (2006) lists similar indications but also<br />

emphasizes an anti-inflammatory action beneficial in acute phases of rheumatoid arthritis as well<br />

as musculoskeletal disorders in general. Some respected practitioners suggest there is a hormonal<br />

effect that can be helpful in promoting conception and modulating perimenopausal symptoms<br />

(Mills & Bone, 2000). Other practitioners dispute any significant hormonal activity (Romm,<br />

2010). Modern midwives continue to use it for the nausea and vomiting of pregnancy as well as<br />

threatened miscarriage and for ineffective, hypertonic uterine contractions during labor (Romm,<br />

2010).<br />

Table 2: Modern phytotherapeutic uses of D. <strong>villosa</strong><br />

ACTIONS<br />

Spasmolytic Nervine<br />

Anti-inflammatory Mild diaphoretic<br />

Cholagogue<br />

THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS<br />

Bilious colic, cholecystitis, spasmodic griping pain in stomach and<br />

bowels<br />

Spasmodic dysmenorrhea, uterine cramps, ovarian neuralgia,<br />

salpingitis<br />

Dyspepsia, morning sickness, chronic flatulence, diverticulitis<br />

Acute phase of rheumatoid arthritis, gout, neuralgia<br />

Menopausal symptoms, false labour pains<br />

Leg cramps, intermittent claudication<br />

7

(Priest & Priest, 1982; British Herbal Medicine Association, 1983; Mills & Bone, 2000; Braun<br />

& Cohen 2010)<br />

Specific Indications<br />

Bilious colic, acute phase of rheumatoid arthritis (British Herbal Medicine Association, 1983)<br />

Combinations: with Echinacea angustifolia DC. and Hydrastis canadensis L. in salpingitis<br />

With Sambucus nigra L. and Althaea officinalis L. for appendicitis and diverticulitis (British<br />

Herbal Medicine Association, 1983)<br />

Preparations and dosage<br />

Decoction of dried root, 2-4g three times daily<br />

Tincture: 2-10 mL three times daily<br />

Fluid extract (1:1) 2-4mL/ three times daily (British Herbal Medicine Association, 1983)<br />

Toxicity and contrindications<br />

The Botanical Safety Handbook lists D.<strong>villosa</strong> as Class 1: “Herbs that can be used safely when<br />

used appropriately” (McGuffin, Hobbs, Upton, & Goldberg, 1997).<br />

D. <strong>villosa</strong> is deemed to be safe for use in cosmetic studies based on short-term toxicity, dermal<br />

irritation, sensitization and genotoxicity tests (Braun & Cohen, 2010).<br />

Based on a single report on a product based on D. opposita found in the Australian Drug<br />

Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC) database, a study was conducted to determine whether<br />

giving rats D. <strong>villosa</strong> extracts for four weeks (0.79 g/kg/d) posed a potential risk to renal and<br />

hepatic health (Wojcikowski, Wohlmuth, Johnson, & Gobe, 2008). Although the study revealed<br />

an increase in collagen formation, growth factors and other markers of renal fibrosis, along with<br />

pro-inflammatory markers in the liver, there were no signs of acute renal or hepatotoxicity.<br />

Based on these findings the authors recommended that D. <strong>villosa</strong> not be taken for extended<br />

periods of time or when pre-existing kidney damage exists (Wojcikowski et al., 2008).<br />

D. <strong>villosa</strong> is regulated in the USA as a dietary supplement.<br />

6. Sustainability considerations<br />

Currently found in over two-thirds of the United <strong>State</strong>s (USDA, 2011), D. <strong>villosa</strong> is listed as "at<br />

risk" by the United Plant Savers (2011) due to habitat loss and over-harvesting. While there are<br />

many different species from the US, Canada, Puerto Rico and South America the phytochemical<br />

properties and percentage composition varies widely, however most do contain diosgenin<br />

(Burnham, 2006; Chu, & Figueiredo-Ribeiro, 1991). Therefore, brokers and direct buyers are<br />

more concerned with diosgenin levels than the specificity of the species (Greenfield & Davis,<br />

2004). Because some medicinal species of <strong>Dioscorea</strong> are fairly abundant, the sustainability of<br />

other less abundant or rare species may be jeopardized as a result of indiscriminate collecting<br />

practices. The impact on the most abundant species is initially buffered, but will gradually<br />

increase as other species decline.<br />

D. quaternata, previously called D. <strong>villosa</strong> v. glabra, may have been used as a substitute for D.<br />

8

<strong>villosa</strong> since the 1850s (Cech, 2000), however this is no longer considered to be a separate<br />

species (The Plant List, 2010). D. hirticaulis, another synonym for D. <strong>villosa</strong>, is listed as rare and<br />

vulnerable globally and historic in Maryland while D. <strong>villosa</strong> is considered globally secure and is<br />

not listed as endangered, threatened or rare.<br />

Note: D. bulbifera is a non-native to the Southern coastal states and is considered a noxious<br />

weed.<br />

Harvesting & Collection regulations<br />

There are no known restrictions for collecting or harvesting wild yam at this time.<br />

Market data - harvesting impact, tonnage surveys<br />

According to Greenfield & Davis (2004) demand currently exceeds supply; increased<br />

applications as dietary supplements in European, North and South American markets may<br />

continue to increase marketability. Albrecht (2006) felt that overall, specific demand for D.<br />

<strong>villosa</strong> was relatively low, a claim supported by Greenfield & Davis (2004), who noted that<br />

general brokers are more concerned about the diosgenin levels than the specificity of the species.<br />

Rather than increasing production of <strong>Dioscorea</strong> plants, industry has been researching ways to<br />

increase diosgenin production in vitro or by chemically converting steroids from other plants<br />

such as fenugreek (Trigonella spp.) (Nagata & Ebizuka, 2002). While this may impact the mass<br />

market nutraceuticals, there will still be a demand for D. <strong>villosa</strong> roots for organic or value-added<br />

companies. Of the major companies selling wild yam products in North America and Europe, at<br />

least 21% had products containing D. <strong>villosa</strong> alone; 35% had a combination of mixed<br />

supplements and stand-alone products (Greenfield & Davis, 2004).<br />

Buyers purchasing wild yam roots look for diosgenin levels over 5%, but because wild yam<br />

deteriorates rapidly after harvesting, collection has primarily been limited to low-volume<br />

collectors who are capable of supplying small amounts of roots in a fresh state (Greenfield &<br />

Davis, 2004).<br />

Once collected, any unused roots must be discarded due to deterioration of the bioactive<br />

components, which becomes an economic factor for the grower and collector (Greenfield &<br />

Davis, 2004).<br />

Cultivation<br />

Habitat<br />

Soil requirements for D. <strong>villosa</strong> cover a fairly wide range of pH and soil environments from part<br />

shade to high light, from hardwood forest to sandy or heavy clay (Filyaw, 2006; PFAF, 2010;<br />

Harding, 1908). The two requirements for growing or cultivating wild yam are moist soils with<br />

good drainage and sunlight to light shade (PFAF, 2010; Burnham, 2006). Mayapples<br />

(Podophyllum peltatum) and black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) are often found growing with D.<br />

<strong>villosa</strong> (Greenfield & Davis, 2004).<br />

If open fields are used, structures to provide light shade and support for the climbing vines<br />

(Cech, 2002) should be provided. Greenfield and Davis (2004) suggest that shade be seven feet<br />

tall and open to the prevailing winds.<br />

9

Propagation<br />

Wild yam has been propagated easily by both seed and root division (Atkinson, n.d.). Field<br />

plants should be spaced about 12-18" apart (Greenfield & Davis, 2004; Cech 2002).<br />

Seed propagation<br />

Both male and female plants must be grown if seed is desired (PFAF, 2010). Filyaw (2006)<br />

suggests that night insects might be responsible for pollination. Seeds are ripe around<br />

Sepetember (Filyaw, 2006), these should be collected and separated from the capsules anytime<br />

after the first frost (Atkinson, 2010). For wild, woods or garden cultivation Atkinson (2010)<br />

suggests that seed can be scattered over the bare ground and sprinkled with garden soil but<br />

should be protected with screening or chicken wire to protect from squirrels or seed eating<br />

animals. If seeds are to be stored, do not let them dry out (Greenfield & Davis, 2004).<br />

For field or controlled propagation, seed should be sown inside in early spring (March-April) and<br />

barely cover, germination takes 1-3 weeks (Fern, 2010). Greenfield and Davis (2004) and<br />

Albrecht (2004) both suggest at least 4 weeks cold stratification, which may not be needed if<br />

seed is gathered in early winter. For greenhouse or seedbed propagation, prick the seedlings as<br />

soon as they have their first true leaves and maintain them the first year, then plant them out the<br />

following spring (Fern, 2010).<br />

Vegetative propagation<br />

Fern (2010) suggests that wild yam can be propagated by basal cuttings during the summer or by<br />

root division once the plants have gone dormant. Root cuttings may produce more than one<br />

shoot, which can be cut about 2-3 inches below the shoot keeping fibrous roots attached and<br />

planted separately (Cech, 2002; Fern, 2010), the remaining tuber may be used in medicine.<br />

Propagation from rhizome division can produce harvestable roots in 2-3 years (Greenfield &<br />

Davis, 2004). Note, some sources suggest using bulbils formed in the leaf axils of wild yam for<br />

propagation, however, D. <strong>villosa</strong> does not produce bulbils (Albrecht, 2004) a fact which can be<br />

used for identification.<br />

Harvest<br />

According to Greenfield and Davis (2004) plants should be at least four years old before<br />

harvesting. Roots are harvested in the fall, after the aerial parts die back, for optimum<br />

concentration of the medically active ingredients (Atkinson, n.d.). Harvested roots should be<br />

cleaned and washed using a mesh and hose; moldy or discolored areas should be removed and<br />

roots can be cut into smaller pieces for drying (Cech, 2002; Greenfield & Davis, 2004; Albrecht,<br />

2006). Dry these at 70 degrees F for one day, then at 110 degrees F. for two or more days, until<br />

they snap when broken (Cech, 2002; Greenfield & Davis, 2004).<br />

Dried roots can be stored in moisture and light proof bags for up to one year after which they<br />

begin to lose their medicinal value.<br />

Pests<br />

Besides being browsed by wildlife, some plants have been recorded with leaf spot, but overall<br />

there are few reported problems with cultivated D. <strong>villosa</strong> (Greenfield & Davis, 2004).<br />

10

7. Summary – some possibilities moving forward<br />

A significant body of experimental data relating to the biological effects of diosgenin has<br />

been acquired over the last 60-70 years, much of which is not specific to D. <strong>villosa</strong>. While<br />

these findings may help validate some traditional uses associated with the species,<br />

comprehensive investigations into the activity of D. <strong>villosa</strong> extracts via the oral route are<br />

long overdue. Further safety data is required to pave the way for future clinical studies.<br />

Clinical investigators would be well served to include one or more certified herbal<br />

practitioners in their research teams. This would help direct the focus away from trendy<br />

products such as the “natural progesterone” creams towards specific clinical applications, as<br />

expounded in the Traditional Use and Modern Phytotherapy sections of this monograph.<br />

8. References.<br />

AHPA (2007) Tonnage Survey of select North American Wild-Harvested plants 2004-2005<br />

American Herbal Products Association. Accessed online at<br />

http://www.ahpa.org/Portals/0/members/04-05_AHPATonnageReport.pdf<br />

Albrecht, M.A. (2006). Reproductive biology of medicinal woodland herbs indigenous to the<br />

Appalachians. PhD Thesis. College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio <strong>University</strong>. Accessed<br />

online at http://etd.ohiolink.edu/view.cgi/Albrecht%20Matthew.pdf?ohiou1163427974.<br />

June 1 st , 2011<br />

Alcantara, E. H., Shin, M.-Y., Sohn, H.-Y., Park, Y.-M., Kim, T., Lim, J.-H., Jeong, H.-J., et al.<br />

(n.d.). Diosgenin stimulates osteogenic activity by increasing bone matrix protein<br />

synthesis and bone-specific transcription factor Runx2 in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells.<br />

The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, In Press, Corrected Proof.<br />

Aradhana, Rao, A. R., & Kale, R. K. (1992). Diosgenin--a growth stimulator of mammary gland<br />

of ovariectomized mouse. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology, 30(5), 367-70.<br />

Atkinson, T. (n.d. ) <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong>, wild yam - 5 (4). North American Native Plant Society.<br />

http://www.nanps.org/index.php/resources/native-plants-to-know/122-dioscorea-<strong>villosa</strong>wild-yam-5-4<br />

Bartlett, H. (1910) The source of the drug <strong>Dioscorea</strong>, with a consideration of the Dioscoeae<br />

found in the United <strong>State</strong>s. Bureau of Plant Industry Bulletin, 189. Washington, DC:<br />

Government Printing Office.<br />

Braun, L. & Cohen, M. (2010). Herbs and natural supplements. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone.<br />

British Herbal Medicine Association (1983). British herbal pharmacopoeia. Bournemouth U.K.:<br />

B.H.M.A.<br />

British Herbal medicine Association. (2006). British Herbal Compendium, v.2: A handbook of<br />

scientific information on widely used plant drugs. P.R. Bradley (Ed.). Bournemouth, UK:<br />

British Herbal Medicine Association.<br />

11

Brinker, F. (2008). Wild yam – sorting out the species. J American Herbalists Guild 8 (2), 3-13.<br />

Burnham, R. (2006) Disocorea <strong>villosa</strong> L. Plant Diversity Website, <strong>University</strong> of Michigan<br />

accessed at http://wwwpersonal.umich.edu/~rburnham/SpeciesAccountspdfs/DiosvillDIOSFINAL.pdf<br />

Cech, R. (2000). The medicinal herb grower volume 1 Williams, OR: Horizon Herbs<br />

Cech, R. (2002) Growing At-risk Medicinal Herbs: Cultivation, Conservation, and Ecology.<br />

Williams, OR: Horizon Herbs.<br />

Chu, E. & Figueiredo-Ribeiro (1991) Native and exotic species of <strong>Dioscorea</strong> used as food in<br />

Brazil. Eonomic Botany, 45, 4, 467-479.<br />

Cook, W. (1869). The physiomedical dispensatory: A treatise on therapeutics, materia<br />

medica and pharmacy. Cincinnati OH. Pub. by the author.<br />

Crellin, J.K., & Philpott, J. (1990). A reference guide to medicinal plants. Durham, NC: Duke<br />

<strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Duke, J. ( 2002 ) Handbook of medicinal herbs. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press<br />

Ellingwood, F. (1919). American material medica, therapeutics and pharmacognosy. Chicago,<br />

IL. Evanston III.<br />

Fern, K. (2011) <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong> sp. Global species. Plants for the Future Published by Myers<br />

EnterprisesII and accessed at http://www.globalspecies.org/ntaxa/1174578<br />

Filyaw, T. (2006) <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong>. Plants to watch: Non-timber products from Appalachian<br />

forest and field. Accessed online at<br />

hhttp://www.appalachianforest.org/ptw_wild_yam.html<br />

Foster, S. & Johnson, R.L. (2006). Desk reference to nature’s medicine. Washington D.C.:<br />

National Geographic.<br />

Fujii, K. & Matsukawa, T. (1936). Saponins and Sterols. 8. Saponin of <strong>Dioscorea</strong> tokoro<br />

Makino. Journal of Pharmaceutical Society of Japan, 56, 408-414.<br />

Fyfe, J. (1909). Specific diagnosis and specific medications; Together with abstracts from the<br />

writings of John Scudder and other leading authors. Cincinnati, OH. The Scudder<br />

Brothers co.<br />

Gleason, H.A., & Cronquist, A. (1991). Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United<br />

<strong>State</strong>s and Adjacent Canada. Bronx, NY: New York Botanical Garden Press.<br />

Greenfield, J. & Davis, J. (2004) Medicinal herb production guide. North Carolina Consortium<br />

12

on Natural Medicines and Public Health accessed online (2011) at<br />

http://www.naturalmedicinesofnc.org/Growers%20Guides/WildYam-gg.pdf<br />

Gunn, J. (1859). Gunn’s new domestic physician: or Home-book of health. Cincinnati,<br />

OH.Moore, Wilstach, Keys & co.<br />

Harding, A. (1908) Ginseng and other medicinal plants. Posted online at Project Gutenberg on<br />

December 5, 2010 at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34570/34570.txt<br />

Hayes, P. Y., Lambert, L. K., Lehmann, R., Penman, K., Kitching, W., & De Voss, J. J. (2007).<br />

Complete (1)H and (13)C assignments of the four major saponins from <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong><br />

(wild yam). Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry: MRC, 45(11), 1001-1005.<br />

Higdon, K., Scott, A., Tucci, M, Benghuzzi, H, Tsao, A., Puckett, A., Cason, Z., et al. (2001).<br />

The use of estrogen, DHEA, and diosgenin in a sustained delivery setting as a novel<br />

treatment approach for osteoporosis in the ovariectomized adult rat model. Biomedical<br />

Sciences Instrumentation, 37, 281-286.<br />

Howell, P. (2006). Medicinal plants of the southern Appalachians. Mountain City, GA:<br />

BotanoLogos Books.<br />

Hu, C., Lin, J., Liu, S., & Yang, D., (2007). A spirostanel glycoside from wild yam (<strong>Dioscorea</strong><br />

<strong>villosa</strong>) extract and its cytostatic activity on three cancer cells. J Food and Drug Analysis,<br />

15 (3), 310-315.<br />

Komesaroff, P.A., Black, C.V.S., Cable, v. & Sudhir, K. (2009). Effects of wild yam extract on<br />

menopausal symptoms, lipids and sex hormones in healthy menopausal women,<br />

Climacteria 4, 144-150.<br />

Kuts-Cheraux, A.W. (1953). Naturae medicina and naturopathic dispensatory. Chattanooga,<br />

TN: American Naturopathic Physicians and Surgeons Association.<br />

Marker, R. E. (1940). Sterols. CVIII. The preparation of dihydroandosterone and related<br />

compounds from diosgenin and tigogenin. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 62(10), 2621-2625.<br />

Marker, R. E., Turner, D. L., Shabica, A. C., Jones, E. M., Krueger, J., & Surmatis, J. D. (1940).<br />

Sterols. CVII. Steroidal Sapogenins of Aletris, Asparagus and Lilium*. Journal of the<br />

American Chemical Society, 62(10), 2620-2621. doi:10.1021/ja01867a011<br />

Marker, R. E., Turner, D. L., & Ulshafer, P. R. (1940). Sterols. CIV. Diosgenin from certain<br />

American plants. Journal of American Chemical Society, 62(9), 2542-2543.<br />

Martin, F. W. (1969). The Species of <strong>Dioscorea</strong> Containing Sapogenin. Economic Botany, 23(4),<br />

373-379.<br />

13

Mazzio, E. A., & Soliman, K. F. A. (2009). In Vitro Screening for the tumoricidal properties of<br />

international medicinal herbs. Phytotherapy research, 23(3), 385-398.<br />

doi:10.1002/ptr.2636<br />

McGuffin, M., Hobbs, C., Upton, R., & Goldberg, A. (1997). Botanical safety handbook. Boca<br />

Raton: CRC Press.<br />

Meader, L. (1861). The people’s medical companion and family guide, in the preparation of<br />

medicine for the sock and afflicted. Cincinnati, OH. Pub. by the author.<br />

Mills, S.Y., & Bone, K. (2000). Principles and practice of phytotherapy: modern herbal<br />

medicine. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone.<br />

Moalic, S., Liagre, Bertrand, Corbière, C., Bianchi, A., Dauça, M., Bordji, K., & Beneytout, Jean<br />

L. (2001). A plant steroid, diosgenin, induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and COX<br />

activity in osteosarcoma cells. FEBS Letters, 506(3), 225-230.<br />

Moerman, D.E. (1998). Native American ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press.<br />

Moore, E. (1930). Direct therapeutics. Pittsburg, PA. Pub. by author.<br />

Morgan, M. (2011). Herbs for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. A Phytotherapist’s<br />

Perspective, 45 (May), 1-3. Accessed online July 27 th 2011 at<br />

http://www.mediherb.com/pdf/6080.pdf<br />

Nagata, T. & Ebizuka, Y. (eds.) (2002) Medicinal and Aromatic plants, vol 12. Berlin, Germany:<br />

Springer-Verlag<br />

Nappez, C., Liagre, B., & Beneytout, J. L. (1995). Changes in lipoxygenase activities in human<br />

erythroleukemia (HEL) cells during diosgenin-induced differentiation. Cancer Letters,<br />

96(1), 133-140.<br />

Paine, W. (1874). New school remedies, and their application to the cure of diseases, including<br />

those of women, children and surgery. Philadelphia, PA.: Claxton, Remsen &<br />

Haffelfinger.<br />

Pengelly, A. (2004). The constituents of medicinal plants. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.<br />

Priest, A.W. & Priest, L.R.1982. Herbal Medication. London: L.N.Fowler & co.<br />

Raju, J., & Bird, R. (2007). Diosgenin, a naturally occurring furostanol saponin suppresses 3hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl<br />

CoA reductase expression and induces apoptosis in HCT-116<br />

human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Letters, 255(2), 194-204.<br />

Romm, A. 2010. Botanical medicine for women’s health. St. Louis, MO: Churchill Livingstone<br />

Elsevier.<br />

14

Royal Botanic Gardens (2011) <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong>. Kew world checklist of selected plant families.<br />

Kew, England: accessed at<br />

http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=8101<br />

22<br />

Salter, S. (1877). The American practice of domestic medicine. Atlants, GA. J.P. Harrison & co.<br />

Sautour, M., Miyamoto, T., Lacaille-Dubois, M. A. (2006). Steroidal saponins and flavan-3-ol<br />

glycosides from <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong>. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 34(1), 60-63.<br />

Sautour, M., Mitaine-Offer, A.-C., & Lacaille-Dubois, M.-A. (2007). The <strong>Dioscorea</strong> genus: a<br />

review of bioactive steroid saponins. Journal of Natural Medicines, 61(2), 91-101.<br />

Scott, A., Higdon, K., Benghuzzi, H, Tucci, M, Cason, Z., England, B., Tsao, A., et al. (2000).<br />

TCPL drug delivery system: the effects of synthetic DHEA and Diosgenin using an<br />

ovariectomized rat model. Biomedical Sciences Instrumentation, 36, 171-176.<br />

Sievers, A.F. 1930. The Herb Hunters Guide. Misc. Publ. No. 77. USDA, Washington DC.<br />

Updated version (1998) accessed online at Purdue <strong>University</strong> Center for New Crops and<br />

Plant Products at http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/herbhunters/yam.html<br />

Shishodia, S., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2005). Diosgenin inhibits osteoclastogenesis, invasion, and<br />

proliferation through the downregulation of Akt, I[kappa]B kinase activation and NF-<br />

[kappa]B-regulated gene expression. Oncogene, 25(10), 1463-1473.<br />

Son, S., Kim, J. H., Sohn, H. Y., Kun, H. S., Kim, J.-S., & Kwon, C.-S. (2007). Antioxidative<br />

and Hypolipidemic Effects of Diosgenin, a Steroidal Saponin of Yam (<strong>Dioscorea</strong> spp.),<br />

on High-Cholesterol Fed Rats. Biosc. Biotechnol. Biochem., 71(12), 3063-3071.<br />

The Plant List (2010). Version 1. Published on the Internet; http://www.theplantlist.org/<br />

(accessed June 22 nd , 2011).<br />

Tucci, Michelle, & Benghuzzi, Hamed. (2003). Structural changes in the kidney associated with<br />

ovariectomy and diosgenin replacement therapy in adult female rats. Biomedical Sciences<br />

Instrumentation, 39, 341-346.<br />

United Plant Savers (2011) Species at risk. Accessed online at<br />

http://www.unitedplantsavers.org/content.php?121-species-atrisk&s=d421705b10d67550588182495d68f58f<br />

USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. (2011) Germplasm Resources Information<br />

Network - (GRIN. Beltsville, MD: National Germplasm Resources Laboratory. Accessed<br />

at<br />

URL: http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?14267<br />

15

USDA, NRCS. 2006. The Plants Database, Version 3.5 (http://plants.usda.gov). Data compiled<br />

from various sources by Mark W. Skinner. Baton Rouge, LA: National Plant Data Center.<br />

Wall, O.A. (1917). Handbook of pharmacognosy. Lane Medical Library. Digitized by Google;<br />

retrieved from:<br />

http://books.google.com/books?id=oEGpexesWYQC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_<br />

ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false<br />

Warren, I. (1859). The household physician; For the use of families, planters, seamen and<br />

travelers. Boston, MA. Higgins, Bradley & Dayton co.<br />

Wojcikowski, K., Wohlmuth, H., Johnson, D., & Gobe, G. (2008). <strong>Dioscorea</strong> <strong>villosa</strong> (wild yam)<br />

induces chronic kidney injury via pro-fibrotic pathways. Food and Chemical Toxicology,<br />

46(9), 3122-3131<br />

Wu, W.-H., Liu, L.-Y., Chung, C.-J., Jou, H.-J., & Wang, T.-A. (2005). Estrogenic Effect of<br />

Yam Ingestion in Healthy Postmenopausal Women. Journal of the American College of<br />

Nutrition, 24(4), 235 -243.<br />

Yen, M. L., Su, J. L., Chien, C. L., Tseng, K. W., Yang, C. Y., Chen, W. F., Chang, C. C., et al.<br />

(2005). Diosgenin Induces Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Activation and Angiogenesis<br />

through Estrogen Receptor-Related Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and p38 Mitogen-<br />

Activated Protein Kinase Pathways in Osteoblasts. Molecular Pharmacology, 68(4), 1061<br />

-1073.<br />

Zava, D.T., Dollbaum, C.M., & Blen, M., 1998. Estrogen and progestin bioactivity of foods,<br />

herbs, and spices. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med., 217 (3), 369-78.<br />

Appendix I. Voucher specimen lodged at the Claude E. Phillips Herbarium, Delaware <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong>. Specimen collected at Ohio Botanic Sanctuary, via Rutledge, OH. May 2011.<br />

16