George Kozmetsky: American Innovator - University of Washington ...

George Kozmetsky: American Innovator - University of Washington ...

George Kozmetsky: American Innovator - University of Washington ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>George</strong> <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>:<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Innovator</strong><br />

A LIFE AT THE INTERSECTION OF TECHNOLOGY AND IDEOLOGY<br />

By Kenneth D. Walters<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Business, UW Bothell; Research Fellow, IC 2 Institute, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Texas, Austin<br />

12 UW BUSINESS<br />

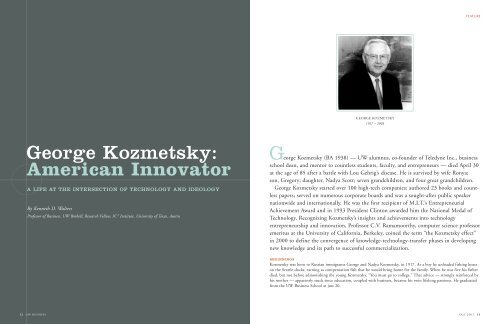

GEORGE KOZMETSKY<br />

1917 – 2003<br />

FEATURE<br />

<strong>George</strong> <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> (BA 1938) — UW alumnus, co-founder <strong>of</strong> Teledyne Inc., business<br />

school dean, and mentor to countless students, faculty, and entrepreneurs — died April 30<br />

at the age <strong>of</strong> 85 after a battle with Lou Gehrig’s disease. He is survived by wife Ronya;<br />

son, Gregory; daughter, Nadya Scott; seven grandchildren, and four great grandchildren.<br />

<strong>George</strong> <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> started over 100 high-tech companies; authored 23 books and countless<br />

papers; served on numerous corporate boards and was a sought-after public speaker<br />

nationwide and internationally. He was the first recipient <strong>of</strong> M.I.T.’s Entrepreneurial<br />

Achievement Award and in 1993 President Clinton awarded him the National Medal <strong>of</strong><br />

Technology. Recognizing <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>’s insights and achievements into technology<br />

entrepreneurship and innovation, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor C.V. Ramamoorthy, computer science pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

emeritus at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California, Berkeley, coined the term “the <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> effect”<br />

in 2000 to define the convergence <strong>of</strong> knowledge-technology-transfer phases in developing<br />

new knowledge and its path to successful commercialization.<br />

BEGINNINGS<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> was born to Russian immigrants <strong>George</strong> and Nadya <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>, in 1917. As a boy he unloaded fishing boats<br />

on the Seattle docks, earning as compensation fish that he would bring home for the family. When he was five his father<br />

died, but not before admonishing the young <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>, “You must go to college.” That advice — strongly reinforced by<br />

his mother — apparently stuck since education, coupled with business, became his twin lifelong passions. He graduated<br />

from the UW Business School at just 20.<br />

FALL 2003 13

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor C.V. Ramamoorthy, computer science pr<strong>of</strong>essor emeritus<br />

at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California, Berkeley, coined the term<br />

“the <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> effect” in 2000 to define the convergence<br />

<strong>of</strong> knowledge-technology-transfer phases in developing new<br />

knowledge and its path to successful commercialization.<br />

It was at the UW that <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> found a true mentor<br />

in the form <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Grant Butterbaugh. Butterbaugh<br />

recognized <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>’s special gifts and took a strong<br />

interest not only in his education but also in his personal<br />

and cultural development, introducing the eager young<br />

man to ideas and experiences outside the formal business<br />

curriculum.<br />

“Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Butterbaugh gave me my first piece <strong>of</strong> art,”<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> recalled in 2001. In appreciation for<br />

Butterbaugh’s mentorship, <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> endowed the Grant<br />

I. Butterbaugh Pr<strong>of</strong>essorship at the UW Business School<br />

in 1968. <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>’s own prolific mentorship was a way<br />

<strong>of</strong> saying thanks to people like Butterbaugh.<br />

Among his many protégés was Michael Dell, chairman<br />

and chief executive <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> Dell. “It was a stroke <strong>of</strong> great<br />

fortune to have Dr. <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> on our team,” said Dell.<br />

“There’s no question that his guidance was instrumental<br />

in our early success.”<br />

MILITARY SERVICE<br />

At UW he enrolled in the Reserve Officers Training<br />

Corps, and quickly enlisted in the Army after the<br />

bombing <strong>of</strong> Pearl Harbor in 1941, where he was assigned<br />

to the Army Medical Corps. After D-Day in June 1944,<br />

he was sent to the front lines in France. Though he rarely<br />

spoke <strong>of</strong> those experiences, he earned a Bronze Star with<br />

an Oak Leaf Cluster, a Silver Star, and a Purple Heart for<br />

assisting injured soldiers and conducting surgery on the<br />

front lines.<br />

After World War II, <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> enrolled at Harvard<br />

Business School, earning his MBA and later a doctorate.<br />

After teaching at Harvard and Radcliffe he became a<br />

member <strong>of</strong> the founding faculty <strong>of</strong> the new Graduate<br />

School <strong>of</strong> Industrial Administration at Carnegie Tech<br />

(later Carnegie-Mellon) where he published important<br />

works with Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon.<br />

PARTNERSHIP WITH RONYA<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> insisted that no proper account <strong>of</strong> his business<br />

and academic success could overstate the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

his wife Ronya, whom he married in 1943 just before his<br />

battalion was shipped to Europe. Together they raised<br />

three children and authored the popular book “Making It<br />

Together: A Survival Manual for the Executive Family.”<br />

He believed it was their duty to inspire young men and<br />

women to face the future with confidence and to embrace<br />

leadership positions in business and society. Their commitment<br />

to this principle was indefatigable. They served<br />

on advisory boards at schools throughout the country,<br />

spoke to student groups, worked for curricular innovation,<br />

sponsored leadership conferences, and supported innovative<br />

faculty research through the family’s RGK Foundation.<br />

PROFESSOR TURNS ENTREPRENEUR<br />

Despite young <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>’s academic prowess, the<br />

burgeoning world <strong>of</strong> high-tech business beckoned. He<br />

joined Hughes Aircraft Company as assistant controller<br />

in 1951, leaving three years later to join Litton Industries.<br />

In 1960 he and Litton colleague Henry Singleton<br />

founded Teledyne Inc., taking the company from startup<br />

to a Fortune 500 powerhouse, encompassing 130 operating<br />

companies spanning the world <strong>of</strong> high-tech in aerospace,<br />

electronics, consumer products, and insurance, in a<br />

mere six years. At Teledyne, <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> and Singleton<br />

were integral in creating the fast-paced, technology-driven<br />

environment that characterized the Los Angeles aerospace<br />

and defense industries in the 1950s and 1960s.<br />

Indeed, <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>’s enthrallment with all forms <strong>of</strong><br />

research and development never abated. “The world is<br />

driven by two forces — technology and ideology,” he said.<br />

“Regions have a choice <strong>of</strong> getting smaller, getting poorer,<br />

or getting smarter.”<br />

FROM ENTREPRENEUR TO DEAN<br />

Following his spectacular business success in California,<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> took his vision <strong>of</strong> high-tech economic development<br />

to Texas, a state built on agriculture and oil.<br />

Son Greg <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> says his father left Teledyne<br />

because “he felt it was time to bring academia and the<br />

corporate world closer together,” a conviction that<br />

His goal was to build a “think tank/do tank” to study<br />

complex problems, improve capitalism, and to actually design<br />

and build new programs and institutions to accelerate the<br />

transfer <strong>of</strong> innovations to the marketplace and society.<br />

endured throughout his life. “You can’t have a government<br />

that doesn’t trust business, you can’t have business that<br />

doesn’t trust government, and academia can’t proceed on a<br />

tangent that has no reference to business or government,”<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> said.<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong>’s leadership as dean <strong>of</strong> The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Texas at Austin’s College <strong>of</strong> Business Administration<br />

went from 1966-1982, a 16 year tenure during which he<br />

catapulted the regional business school into a national<br />

powerhouse.<br />

AMERICAN VISIONARY<br />

During the 1970s <strong>Kozmetsky</strong> became concerned that<br />

<strong>American</strong> capitalism was stagnating. In 1977 he founded<br />

the IC 2 Institute (for Innovation, Creativity, and Capital),<br />

devoted to research and innovation on the intersection <strong>of</strong><br />

business, government, and academe. His goal was to build<br />

a “think tank/do tank” to study complex problems,<br />

improve capitalism, and to actually design and build new<br />

programs and institutions to accelerate the transfer <strong>of</strong><br />

innovations to the marketplace and society.<br />

The experiments launched by IC 2 were ambitious,<br />

starting with scores <strong>of</strong> conferences, books, and research<br />

projects on a wide range <strong>of</strong> complex problems in business<br />

and society. In the 1980s these expanded to include<br />

specific initiatives: an incubator, an angel capital network,<br />

research parks, a graduate degree program in technology<br />

commercialization (delivered over the internet), research<br />

centers, mergers-and-acquisitions activities, IPOs,<br />

and a host <strong>of</strong> startups spawned in Austin and later<br />

brought in from around the world. The cumulative<br />

impact has been transformational. Austin has become a<br />

“technopolis,” a high-tech center <strong>of</strong> research and new<br />

business development.<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> was not provincial or proprietary with his<br />

ideas. He took IC 2 successes and research findings to the<br />

world, spreading a message <strong>of</strong> innovation and technology<br />

entrepreneurship to everyone, including, at the end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Cold War, nascent and emerging market economies such<br />

as Russia and China. Ambitious partnerships were started<br />

in Mexico and the Caribbean. When the NASA-AMES<br />

laboratory, located in the heart <strong>of</strong> Silicon Valley, wanted to<br />

start a business incubator to commercialize NASA research<br />

they looked to IC 2 for a partner and for guidance.<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> was also particularly enthusiastic about<br />

following spinout companies from <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Washington</strong> research. He received continual updates on<br />

new UW-related ventures and new developments in UW<br />

technology transfer. He was especially pleased to see that<br />

his vision <strong>of</strong> the research university as a central factor in<br />

economic development in the “technopolis” was being<br />

implemented in his hometown.<br />

THE 21st CENTURY<br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> saw the future and, while he knew the<br />

importance <strong>of</strong> specialization in a high-tech world, fought<br />

for trans-disciplinary approaches and collaborations.<br />

Recently he wanted to know why business schools<br />

weren’t teaching courses on nanotechnology, genomics,<br />

biotechnology, advanced materials, and all the new<br />

telecommunications technologies. Like all great teachers,<br />

he kept discovering, learning, and experimenting. Failure<br />

was no sin; stagnation and self-satisfaction were.<br />

Visionaries sometimes become discouraged, but not<br />

<strong>George</strong> <strong>Kozmetsky</strong>. His overriding perspectives were<br />

persistence and optimism. His expressed belief in young<br />

people and fundamental brightness about the future set<br />

him apart from those experts who foresee a dark future<br />

for America.<br />

“Today’s generation must understand that its legacy is<br />

to chart its own course. This generation must understand<br />

and accept that there is no existing road map for its<br />

future — and embrace the responsibility to develop its<br />

own. The generational resource is science and technology,<br />

which needs to be nurtured and better understood,”<br />

he admonished.<br />

For some, it is enough to say they have seen the advent<br />

<strong>of</strong> space travel, the creation <strong>of</strong> the Internet. <strong>George</strong><br />

<strong>Kozmetsky</strong> more than existed in history’s most innovative<br />

era, he lived at the intersection <strong>of</strong> technology and ideology.<br />

Adapted with permission, Northwest Science & Technology Magazine,<br />

Autumn 2003, pp. 45-47<br />

14 UW BUSINESS FALL 2003 15