FREE LAW JOURNAL Volume 1, Number 2 (October 18, 2005)

FREE LAW JOURNAL Volume 1, Number 2 (October 18, 2005)

FREE LAW JOURNAL Volume 1, Number 2 (October 18, 2005)

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

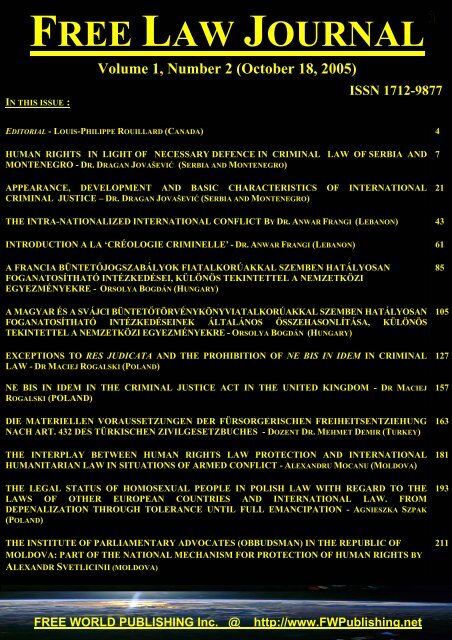

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong><br />

IN THIS ISSUE :<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 1, <strong>Number</strong> 2 (<strong>October</strong> <strong>18</strong>, <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

ISSN 1712-9877<br />

EDITORIAL - LOUIS-PHILIPPE ROUILLARD (CANADA)<br />

HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND<br />

MONTENEGRO - DR. DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ (SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO)<br />

APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL<br />

CRIMINAL JUSTICE – DR. DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ (SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO)<br />

THE INTRA-NATIONALIZED INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT BY DR. ANWAR FRANGI (LEBANON)<br />

INTRODUCTION A LA ‘CRÉOLOGIE CRIMINELLE’ - DR. ANWAR FRANGI (LEBANON)<br />

A FRANCIA BÜNTETŐJOGSZABÁLYOK FIATALKORÚAKKAL SZEMBEN HATÁLYOSAN<br />

FOGANATOSÍTHATÓ INTÉZKEDÉSEI, KÜLÖNÖS TEKINTETTEL A NEMZETKÖZI<br />

EGYEZMÉNYEKRE - ORSOLYA BOGDÁN (HUNGARY)<br />

A MAGYAR ÉS A SVÁJCI BÜNTETŐTÖRVÉNYKÖNYVIATALKORÚAKKAL SZEMBEN HATÁLYOSAN<br />

FOGANATOSÍTHATÓ INTÉZKEDÉSEINEK ÁLTALÁNOS ÖSSZEHASONLÍTÁSA, KÜLÖNÖS<br />

TEKINTETTEL A NEMZETKÖZI EGYEZMÉNYEKRE - ORSOLYA BOGDÁN (HUNGARY)<br />

EXCEPTIONS TO RES JUDICATA AND THE PROHIBITION OF NE BIS IN IDEM IN CRIMINAL<br />

<strong>LAW</strong> - DR MACIEJ ROGALSKI (POLAND)<br />

NE BIS IN IDEM IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE ACT IN THE UNITED KINGDOM - DR MACIEJ<br />

ROGALSKI (POLAND)<br />

DIE MATERIELLEN VORAUSSETZUNGEN DER FÜRSORGERISCHEN FREIHEITSENTZIEHUNG<br />

NACH ART. 432 DES TÜRKISCHEN ZIVILGESETZBUCHES - DOZENT DR. MEHMET DEMIR (TURKEY)<br />

THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN HUMAN RIGHTS <strong>LAW</strong> PROTECTION AND INTERNATIONAL<br />

HUMANITARIAN <strong>LAW</strong> IN SITUATIONS OF ARMED CONFLICT - ALEXANDRU MOCANU (MOLDOVA)<br />

THE LEGAL STATUS OF HOMOSEXUAL PEOPLE IN POLISH <strong>LAW</strong> WITH REGARD TO THE<br />

<strong>LAW</strong>S OF OTHER EUROPEAN COUNTRIES AND INTERNATIONAL <strong>LAW</strong>. FROM<br />

DEPENALIZATION THROUGH TOLERANCE UNTIL FULL EMANCIPATION - AGNIESZKA SZPAK<br />

(POLAND)<br />

THE INSTITUTE OF PARLIAMENTARY ADVOCATES (OBBUDSMAN) IN THE REPUBLIC OF<br />

MOLDOVA: PART OF THE NATIONAL MECHANISM FOR PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS BY<br />

ALEXANDR SVETLICINII (MOLDOVA)<br />

<strong>FREE</strong> WORLD PUBLISHING Inc. @ http://www.FWPublishing.net<br />

4<br />

7<br />

21<br />

43<br />

61<br />

85<br />

105<br />

127<br />

157<br />

163<br />

<strong>18</strong>1<br />

193<br />

211

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

The Free Law Journal results of a merger with the Eastern European Law Journals. It builds<br />

upon this previous success and aims at providing the freedom of publishing juridical research<br />

from everywhere and on all subjects of law. Its goal is to promote respect of the rule of law and<br />

the fair application of justice by sharing juridical research in its pages.<br />

Academics, post-graduate students and practitioners of law are welcome to submit in the<br />

academic section their articles, notes, book reviews or comments on any legal subject, while<br />

undergraduate students are welcome to publish in our student section. The list of fields of law<br />

addressed in these pages is ever-expanding and non-restrictive, as needs and interests arise. If a<br />

field is not listed, the author simply needs to propose the article and the field believed of law<br />

applicable; we will insure to create and list it.<br />

We accept articles in English, French, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Finnish, German,<br />

Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Innuktikut, Italian, Latin, Polish, Portugese (both Brazilian and<br />

European), Romanian, Russian, Serb (both Latin and Cyrillic), Slovenian,Spanish and Turkish.<br />

Articles not in English are provided with a synopsis to explain their content. Articles of<br />

exceptional quality, or requested to be, can be translated into English and/or French. All of this<br />

is the measure of freedom we provide.<br />

The material submitted for publication remains copyrighted to the author. If the author has<br />

interest in publishing elsewhere after having published in our pages, no permission to do so will<br />

be necessary. The author remains in full control of his or her writings. Articles of superior value<br />

will be considered for incorporation in collective works for publishing.<br />

We always accept submissions. To submit, please read the submission guidelines or ask us any<br />

question at : FLJ@FWPublishing.net .<br />

List of subject addressed (as it currently stands - subject to modifications as need arise)<br />

Administrative Law<br />

Admiralty law<br />

Antitrust law<br />

Alternative dispute resolution<br />

Anti-Terrorism<br />

Bankruptcy<br />

Business Law<br />

Canon Law<br />

Civil Law<br />

Common Law<br />

Comparative Law<br />

Constitutional Law<br />

Contract Law<br />

(Consuetudinary law)<br />

Obligations<br />

Quasi-contract<br />

Corporations law<br />

Criminal Law<br />

Organised Crime<br />

Criminal Procedure<br />

Cyber Crime Law<br />

Penal law<br />

Cyber law<br />

Election law<br />

Environmental law<br />

European Law<br />

Evidence Law<br />

Family law<br />

History of Law<br />

Human Rights Law<br />

Immigration Law<br />

Intellectual Property Law<br />

International trade law<br />

Patent<br />

Trademark Law<br />

International Humanitarian<br />

Rights Law<br />

Laws of Armed Conflicts<br />

Laws of war<br />

War Crimes Law (Belgium)<br />

International Law (Public)<br />

Diplomatic Relations<br />

Jus Gentium<br />

Treaties Law<br />

Labor law<br />

Law and economics<br />

Law and literature<br />

Medical Law<br />

Public Health Law<br />

Public Law<br />

Malpractice<br />

Mental health law<br />

Military law<br />

National Legal Systems -<br />

(Laws of any national legal<br />

system that is not of a<br />

precise category)<br />

Nationality and naturalisation<br />

Laws<br />

Natural law<br />

Philosophy of Law<br />

2<br />

Private International Law<br />

Private law<br />

Procedural law<br />

Property law (Public)<br />

International Law (See<br />

International Law (Public))<br />

Refugee Law<br />

Religious law<br />

Islamic Law (Sharia)<br />

Qur'an<br />

Sharia<br />

Jewish law (Halakha)<br />

Hebrew law (Mishpat Ivri)<br />

Talmud<br />

Taqlid<br />

Christian (other than Canon<br />

Law)<br />

Twelve Tables<br />

Roman Law<br />

Sacred text<br />

State of Emergencies Laws<br />

Space law<br />

Tax law<br />

Technology law<br />

Torts Law<br />

Quasi-delict<br />

Trusts and estates Law<br />

Liens<br />

Water law<br />

Zoning

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Free World Publishing is a partner of the Free European Collegium, provider of web-based, elearning<br />

education in matters related to the European Union.<br />

All material published are available for free on Free World Publishing Inc. web site at<br />

http://www.FWPublishing.net and can be used freely for research purposes, as long as the<br />

authors’ sources are acknowledged in keeping with national standards and laws regarding<br />

copyrights.<br />

All mail correspondence can be made with the editorial board at Karikas Frigyes u.11, 2/1, XIII<br />

kerulet, 1138 Budapest, Republic of Hungary, while electronic correspondence can be made<br />

through FLJ@FWPublishing.net .<br />

The views and opinions expressed in these pages are solely those of the authors and not<br />

necessarily those of the editors, Free World Publishing Inc. or that of the Free European<br />

Collegium Inc.<br />

Cited as (<strong>2005</strong>) 1(2) Free L. J.<br />

ISSN 1712-9877<br />

3

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Free Law Journal Submission Guidelines<br />

Important. The following is not meant to discourage from submitting; only to ensure quality. If<br />

your article conforms to your own national standard of writings, we accept all and any format as<br />

long as arguments are justified by footnotes or endnotes. Never hesitate to submit an article : if<br />

there is a need for improvement, we will inform you and we will always remain open for resubmissions.<br />

1. Academics, Post-Graduate Students and Practitioners of law are all welcomed to publish their<br />

book reviews, comments, notes and articles.<br />

2. All legal subjects are considered for publication, regardless of the legal tradition, national or<br />

international field of expertise. The only limit to the extend of our publishing would be content<br />

that is illegal in national legislation (i.e. enticement to hatred) or against international norms (i.e.<br />

promoting genocide).<br />

3. Articles are welcomed in English, French, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Finnish,<br />

German, Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Innuktikut, Italian, Latin, Polish, Portugese (both<br />

Brazilian and European), Romanian, Russian, Serb (both Latin and Cyrillic), Slovenian as well<br />

as Spanish. Note that our staff is limited and therefore we use "Word Recognition<br />

Processors" to communicate in some languages. Nonetheless, this does not prevent<br />

understanding articles submitted in these language and we are not interested in measuring every<br />

word of your article : simply in publishing your writings. Therefore, we will review the general<br />

content, but leave with you the precise sense and meaning that you want to convey in your own<br />

language. If translation is desired by the author, we then submit it for translation to a translator.<br />

4. Their is no defined system of reference (footnotes or endnotes) demanded. As long as you<br />

justify your argument through references (author and work), we accept all writings respecting<br />

your own national standards. Exceptions : For Canadians, the Canadian Legal Guide to Citation<br />

is recommended but not mandatory. For Americans, referencing is expected to be in accordance<br />

with Harvard University's The Bluebook, A Uniform System of Citation. Any breach of<br />

copyrights is the sole responsibility of the author.<br />

5. The author retains the copyrights to his or her writings. As articles are unpaid for, ownership<br />

remains within your hands. We act as publishers and caretaker. Nothing prevents you from<br />

publishing elsewhere. You may even decide to have the article taken off this site if another<br />

publisher desires to buy the rights to your article.<br />

6. We reserve ourselves the right to edit the content or length of the article, if at all necessary.<br />

7. We do not discriminate in any way. Our aim is to bring under one roof perspectives from<br />

everywhere and everyone. Never hesitate to submit.<br />

8. If you desire information or desire to submit, do not hesitate to contact us at :<br />

FLJ@FWPublishing.net.<br />

4

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

EDITORIAL<br />

Welcome to the second issue of the Free Law Journal, a print and electronic journal aiming at<br />

promoting respect of the rule of law and the fair application of justice everywhere through the sharing<br />

of juridical research.<br />

The Free Law Journal’s first issue was a definitive success in terms of scope and reach, registering a<br />

very high volume of consultation on the web and orders of paper copies. This signals a definitive<br />

interest in getting to know the legal research produced everywhere and to share this knowledge.<br />

As such, this permits us to reach our first and foremost objective to promote the rule of law.<br />

Knowledge is definitely part of the application of this objective and we see a clear desire from people<br />

all over the world to gain access to this knowledge in order to foster the fair application of justice for<br />

all.<br />

Therefore, welcome to our second issue and we hope that our contributions to legal research and<br />

knowledge will expand through your witten contributions.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Louis-Philippe F. Rouillard<br />

Editor-in-Chief, Free World Publishing Inc.<br />

5

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

6

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY<br />

DEFENCE IN CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF<br />

SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO<br />

BY DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ*<br />

Introductory remarks<br />

All men in the world have the use of many natural, universal rights who<br />

names are human rights. These rights have general law protection. The<br />

attack to these rights many criminal codes has prescribed as criminal<br />

acts. Lack of any of general, basic elements of the definition of the<br />

criminal act in criminal code, of objective or subjective character,<br />

exempts that act (that is, the act committed by a person, with resulting<br />

consequences) from the character of criminal act 1 . It is regarded to the<br />

circumstances which an act of a man exempts from either social danger<br />

or illegality, or of both elements 2 .<br />

Namely, the exclusion of these elements exists when the act, which is<br />

otherwise regulated by law as a criminal act, is considered as excusable,<br />

according to some special provision. Provisions which allow this<br />

otherwise “forbidden” act in a specific case exclude illegality, so that<br />

there is no criminal act in that case.<br />

There are two bases for the exclusion of the criminal act in the criminal<br />

law of Serbia and Montenegro. They are:<br />

1) general bases (which are specifically provided by law and may be<br />

found in any criminal act or for any perpetrator) and<br />

* Dragan Jovašević PhD, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law in Nis, Serbia<br />

and Montenegro.<br />

1<br />

Ljubiša Jovanović, Dragan Jovašević, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Nomos,<br />

Beograd, 2002.p.72<br />

2<br />

Borislav Petrović- Dragan Jovašević, Kazneno pravo Bosne i Hercegovine,<br />

Opći dio, Pravni fakultet, Sarajevo, <strong>2005</strong>. godine, p. 34-41<br />

7<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

2) special bases ( which are not specifically provided by law and could<br />

not be found in any criminal act or for any perpetrator) 3 .<br />

General bases 4 in the criminal law of the Republic of Serbia (according<br />

to the provisions of the General criminal law) are: 1) insignificant social<br />

danger (article 8. paragraph 2. Basic Criminal Code former Criminal<br />

code of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 5 from July 1976.), 2)<br />

necessary defence (article 9. paragraph 2. Basic Criminal Code) and 3)<br />

extreme necessity (article 10. paragraph 2. Basic Criminal Code).<br />

In the Criminal code of the Republic of Montenegro 6 from December<br />

2003. there is also a number of bases for the exclusion of the criminal<br />

act. They are: 1) an act of little significance (article 9. ), 2) necessary<br />

defence (article 10. ), 3) extreme necessity (article 11. ) and 4) force and<br />

threat (article 12. ).<br />

Special bases for the exclusion of the criminal act are not specifically<br />

provided by law. They present a creation of the law theory and court<br />

practice (but some of them are seen in the foreign legislations in specific<br />

cases). Specific bases usually include: 1) assent of the inflicted, 2) selfinfliction,<br />

3) performing the official duty, 4) superior’s order, 5) the<br />

right for disciplinary or corrective punishment and 6) allowed risk.<br />

According to the fact that these special bases are not specifically<br />

provided by law, their effect and applicability are of controversial<br />

matter 7 .<br />

3 Dragan Jovašević, Leksikon krivičnog prava, Službeni list , Beograd, 2002.p.<br />

376<br />

4 Bogdan Zlatarić- Mirjan Damaška ,Rječnik krivičnog prava i postupka,<br />

Informator, Zagreb,1960.p.193<br />

5 Dragan Jovašević, Komentar Krivičnog zakona SR Jugoslavije, Službeni<br />

glasnik, Beograd, 2002.p.26-29<br />

6 Službeni list Republike Crne Gore, Podgorica, No. 70/2003 ; Ljubiša Lazarević-<br />

Branko Vučković- Vesna Vučković, Komentar Krivičnog zakonika Republike<br />

Crne Gore, Obod, Cetinje, 2004.p.142<br />

7<br />

Zoran Stojanović, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Službeni glasnik, Beograd,<br />

2000.p.148<br />

8<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

The notion of necessary defence<br />

According to provision article 9. paragraph 2. Basic Criminal Code<br />

(with aplication in Republic of Serbia) , and article 10. paragraph 2.<br />

Criminal code of the Republic of Montenegro , necessary defence is<br />

defence which is necessary for a perpetrator in order to protect himself<br />

or other person from an imminent illegal attack 8 . An act committed in<br />

necessary defence is excusable because the legislator himself considers<br />

that the perpetrator of such act is authorised for commission of that act 9 .<br />

From this definition 10 , it results that necessary defence, in the sense of<br />

institute of criminal law, has to fulfil two conditions-the existence of<br />

attack and protection from such attack. But not every attack gives the<br />

right for necessary defence, nor every protection from attack is<br />

necessary defence. Attack, as well as protection from attack, has to fulfil<br />

conditions cumulatively provided by law.<br />

Conditions for the existence of attack<br />

Attack is every act aimed towards violating or endangering legal<br />

property or legal interest of a person 11 . It is most often undertaken by<br />

action, and sometimes by inaction. In order for an act to be relevant<br />

with the view to institute of necessary defence, it has to fulfil certain<br />

conditions, which are: attack has to be undertaken by man; attack has to<br />

be aimed against any legal property or legal interest of a person; attack<br />

has to be illegal; and attack has to be real.<br />

This solution are providing many modern criminal codes as : article 19.<br />

of Criminal code of the Republic of Albania 12 , article 3 of the Criminal<br />

8 H.H. Jescheck, Lehrbuch des Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Berlin,1972.p.251<br />

9 Vojislav Đurđić- Dragan Jovašević - Ljubiša Zdravković, Nužna odbrana u<br />

krivičnom pravu, Niš, 2004.p. 42-53<br />

10 Dragan Jovašević, Tarik Hašimbegović, Osnovi isključenja krivičnog dela,<br />

Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, Beograd, 2001. p. 78-93<br />

11 Josip Šilović, Nužna odbrana, Zagreb, 1910.p.97<br />

12<br />

The Criminal code of the Republic of Albania, Offialia text, Tirana, 2000.<br />

9<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

code of the Republic of Osterrei 13 , article 13. of the Criminal code of<br />

the Republic of Belarus 14 , article 12. of the Criminal code of<br />

theRepublic of Bulgaria 15 , article 6. of the Criminal code of the<br />

Republic of Finland 16 , article 122-5 of Criminal code of the Republic of<br />

France 17 , article 22. of the Greek criminal law <strong>18</strong> , article 11. of Criminal<br />

code of the Republic of Slovenia 19 , article 9. of the Criminal code of the<br />

Republic of Macedonia 20 , article 29. of the Criminal code of the<br />

Republic of Croatia 21 , article 52. of the Criminal code of the Republic of<br />

Italy 22 , article 22. of the Criminal code of the Republic of Israel 23 , article<br />

20. of the Criminal code of the Peoples Republic of China 24 , articles 32.<br />

and 33. of the Criminal cdoe of the Federal Republic of Germany 25 ,<br />

article 37. of the Criminal code of the Russian federation 26 , article 33. of<br />

the Criminal code of the Swiss federation 27 , article 15. of the Republic<br />

of Ukraine 28 etc.<br />

1) Attack can only be undertaken by man.-If an act is not undertaken by<br />

13<br />

Otto Trifterer, Osterreischesches Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Wien, New<br />

York, 1994.<br />

14<br />

The Suprime Soviet of the BSSR, Criminal code of the Republic of Belarus,<br />

Official text, Minsk, 2001.<br />

15<br />

I. Nenov, Nakazatelno pravo, Obša čast, Sofia, 1993.<br />

16<br />

Finnish Penal code, Finnish Ministry of Justice, Helsinky, 1996.<br />

17<br />

G. Stefani, G. Levasseur, B. Bulock, Droit penal general, Paris, 1994.<br />

<strong>18</strong><br />

N.B.Lolis, G. Mangakis, The Greek penal code, London, 1973.<br />

19<br />

B.Penko, K. Strog, Kazenski zakonik z uvodnimi pojasnili, Ljubljana, 1999.<br />

20<br />

Gorgi Marjanovik, Krivično pravo, Opšt del, Skoplje, 1998.<br />

21<br />

Željko Horvatić, Miroslav Šeparović, Novo hrvatsko kazneno pravo, Zagreb,<br />

1997. ; Željko Horvatić, Petar Novoselec, Kazneno pravo, Opći dio, zagreb,<br />

2001.<br />

22<br />

Compendio di diritto penale, Parte generale e speciale, Simone, Napoli, 2004.<br />

23<br />

Laws of the State of the Israel, Special volume, Penal law, Jerusalem, 1977.<br />

24<br />

C.D. Pagle, Criminal law of the People’s Republic of China, Peking, 1997.<br />

25<br />

W.Gropp, Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 1998. ;<br />

U: Ebert, Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Heidelberg, 1993.<br />

26<br />

J.I. Skuratov, V.M.Lebedov, Kommentarii k Ugolovnomu kodeksu v<br />

Rossijskoj federacii, Norma, Moskva, 1996.<br />

27<br />

Schweiserisches Strafgesetzbuch, Stand Am 1. April 1996., Bern, 1997.<br />

28<br />

M.I.Koržanskij, Popularnij kommentar Kriminolnogu kodeksu Ukrajini,<br />

NAUkova dumka, Kiev, 1997.<br />

10<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

man but by an animal or by a force of nature, then there is the existence<br />

of danger as an element of extreme necessity, but not as well necessary<br />

defence. However, if a person directed a force of nature (torrent,<br />

rockslide) in order to endanger other person or his legal property, or if<br />

an animal (a dangerous dog or a horse) is used as means for<br />

endangering protected property, than these cases are also considered as<br />

necessary defence. Attack could be undertaken by any person, no matter<br />

of the age, accountability or guilt. It could be undertaken by any action<br />

or inaction, as well as using any means which is suitable for violation or<br />

endangering some legal property 29 .<br />

Therefore, necessary defence is excusable in case of an actual attack<br />

(instantaneous or present), as well as in case of imminent attack.<br />

Whether the attack is imminent, is a question which is determined by<br />

court in each particular case, judging all the circumstances of the<br />

committed act and the perpetrator. The attack is imminent when there is<br />

a possibility (in time and place) of the close carrying out an attack 30 .<br />

But, it does not mean that necessary defence is excusable against future,<br />

undetermined in place and time, but indicated attacks. Measures of<br />

precaution and preventive protection against indicated or expected<br />

attacks are excusable only if they do not go over the limits of necessary<br />

measures for that specific moment.<br />

2) Attack has to be aimed against a person, his legal property or legal<br />

interest.-Attacked or endangered properties, in the sense of necessary<br />

defence, could be different. Most often, life and physical integrity is<br />

being attacked, but sometimes it can be property, honour, reputation,<br />

dignity, moral. The object of attack could be any legal property or legal<br />

interest. Law does not explicitly state which are those goods that can be<br />

the objects of attack in the sense of necessary defence. Attack can be<br />

aimed against any legal property of the attacked person, but also against<br />

any legal property of some other physical or legal person. In that way,<br />

29<br />

Petar Novoselec, Krivično pravo, Krivično delo i njegovi elementi, Osijek,<br />

1990.p.35-36<br />

30<br />

Toma Živanović, Krivično pravo Kraljevine Jugoslavije, Opšti deo, Beograd,<br />

1935.p.231<br />

11<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

attack can be aimed at violating the property of a corporation, facility or<br />

some other organization, but also against state security and its<br />

constitution.<br />

Therefore, necessary defence exists not only in case of protecting from<br />

the attack on a legal property, but also in case of protecting from the<br />

attack on any property of other person (physical or legal) if that person<br />

is not capable of protecting himself from such attack. There are theories<br />

in criminal law 31 , according to which some cases of protecting from the<br />

attack are not considered to be necessary defence, but called “necessary<br />

help”. In any case, the scope and necessity of defence depend in the first<br />

place on the nature of legal property which is attacked or endangered.<br />

3) Attack has to be illegal.-Attack is illegal when it is not based on some<br />

legal regulation and when it is not undertaken on the bases of some<br />

legal authorisation. Therefore, attack which is undertaken during<br />

exercising duty according to some legal authorisation, is not illegal and<br />

necessary defence in that case is not excusable. However, if an<br />

authorised person oversteps the limits of legal authorisation, then such<br />

situation is changed into illegal attack against which necessary defence<br />

is allowed. On the other hand, violation of necessary defence also<br />

changes into illegal attack, in which case the attacker has the right for<br />

defence (because in this case he is in the state of necessary defence).<br />

The right for necessary defence exists no matter if the attacker is<br />

conscious of illegality of his attack or not. Namely, it is enough that the<br />

attacked person objectively realises the attack. It is of no significance<br />

whether the attacker is guilty or not, as well as whether his act is<br />

punishable. Illegal attack could be undertaken by a child or by a<br />

mentally incompetent person. That means that necessary defence on<br />

necessary defence is not excusable. But, different situations in life can<br />

happen, when the attacked person anticipates the possibility of being<br />

attacked in certain place and time because of his relationship with some<br />

person. If in such situations anticipated attack is undertaken, it is<br />

31<br />

Vojislav Đurđić - Dragan Jovašević, Praktikum za krivično pravo, Knjiga<br />

prva, Opšti deo, Službeni glasnik, Beograd,2003.p.26-32<br />

12<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

considered as illegal.<br />

Even more controversial situation is when a person provokes attack.<br />

There is no dilemma if the attacked person had previously endangered<br />

someone’s integrity or property. The problem arises if such attack is<br />

manifested verbally or only with concluding acts which irritate, provoke<br />

or underestimate the attacker. Social component of the institute of<br />

necessary defence should be considered in such situations. Namely,<br />

necessary defence stands for protecting the rights from illegality, and<br />

because of that abuse of this institute is not excusable. If the attacked<br />

person had deliberately provoked the attack, so as to use it and violate<br />

the attacker or his property, than the attacked person has no right on<br />

necessary defence. Such cases are known as feign necessary defence 32 .<br />

4) Attack has to be real.-Namely, it has to exist really in the outside<br />

world. It means that it is necessary that the attack has already started or<br />

it is imminent. Whether an attack exists or not, is a factual question<br />

which is being solved by court in each specific case. Typical example of<br />

real attack is endangering life or making physical injuries to a person. If<br />

there is no real attack, but the attacked person had a wrong or<br />

incomplete impression or illusion of its existence, there is no basis for<br />

necessary defence. In such case there is putative, imaginable or<br />

ostensible necessary defence. This defence does not exclude the<br />

existence of a criminal act, but it could be a ground for exclusion of the<br />

guilt 33 .<br />

Therefore, putative necessary defence represents, in fact, the lack of<br />

conscience of the attacked person about some real circumstance of the<br />

attack. That is, in fact, wrong impression and conviction that the attack<br />

aimed at violation of some property is real. This mistake could be<br />

related to the conscience about the illegality of the attack (when there is<br />

legal mistake). In other words, putative necessary defence is reduced to<br />

32<br />

Ljubo Bavcon, Alenka Šelih, Kazensko pravo, Splošni del,<br />

Ljubljana,1987.p.151<br />

33<br />

Zoran Stojanović, Komentar Krivičnog zakona SR Jugoslavije, Službeni list,<br />

Beograd, 1999.p.22-24<br />

13<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

unavoidable mistake, in broader or narrower sense that the attacked<br />

person is in a condition of real and objectively needed necessary<br />

defence. When judging the existence of necessary defence or its<br />

violation, an act has to be seen on the whole, which means that it cannot<br />

be reduced and limited to only what had happened between the<br />

defendant and late (that is, the one who has suffered loss) immediately<br />

before the gun shot 34 .<br />

Conditions for the existence of defence<br />

Defence or protection from the attack is every action of the attacked<br />

person aimed at eliminating, preventing or protecting from the attack.<br />

By protection from the attack, the attacked person himself violates or<br />

endangers some legal property of the attacker. This violation or<br />

endangerment represents, in essence, formal characteristics of some<br />

criminal act from the federal or republic law (most often it is about a<br />

criminal act against life or physical integrity).<br />

Only in case when the attacked person, during the protection from<br />

attack, violates some property of the attacker, the existence of the<br />

institute of necessary defence is possible 35 . Necessary defence is not<br />

only the defence from the attack which endangers security of life of the<br />

attacked person, but every defence from present and illegal attack, if<br />

such defence was necessary for protection from the attack 36 .<br />

For the definition of needed defence, in the sense of penal law, it is<br />

absolutely necessary that the illegal attack is protected from by a<br />

punishable act towards the attacker. If such protection would not be<br />

considered as a punishable act, then it would be a situation beyond the<br />

area of penal law 37 .<br />

34 presuda Vrhovnog suda Srbije Kž. 474/91<br />

35 Gorgi Marjanovik, Krivično pravo, Opšt del, Prosvetno<br />

delo,Skopje,1998.p.<strong>18</strong>3<br />

36 presuda Vrhovnog suda Srbije Kž. 260/70<br />

37<br />

Đorđe Avakumović, Teorija kaznenog prava, Beograd, <strong>18</strong>87-<strong>18</strong>89,p.279<br />

14<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Defence, as an element of necessary defence, as well, has to fulfil<br />

certain conditions in order to be of criminal legal relevance. These<br />

conditions are: defence consists of protection from the attack; defence<br />

has to be aimed against the property of the attacker; defence has to be<br />

simultaneous with the attack, and defence has to be necessary for the<br />

protection from attack.<br />

1) Defence has to be consisted of protection from the attack.-If defence<br />

is not aimed at protection or prevention of attack, than it is not an<br />

element of necessary defence. Defence, in fact, depends on the existence<br />

of attack. The kind of defence has to be according to the attack.<br />

Attacked person is not obliged to retreat before the attacker. On the<br />

contrary, he is authorised to frustrate and disable the real illegal attack,<br />

in the aim of defence of legal property, by simultaneous legal attack on<br />

the attacker’s legal property 38 .<br />

2) Defence has to be aimed against the attacker and against any of his<br />

legal property or legal interest.-These properties could be various, like:<br />

life, body, estate, honour, reputation, human dignity, though most often<br />

situation is when life of the attacker is violated. But, there are situations<br />

in life, when it is about the violation or endangering legal property and<br />

the attacker, as well as some other person.<br />

Then, in relation to the property of the attacker, the attacked person acts<br />

in necessary defence, and in relation to the violation of property of some<br />

other person, he acts in extreme necessity (if all the conditions provided<br />

by law are fulfilled). That means that the attacked person, in order to<br />

protect his property, cannot put to extreme risk legal properties of other<br />

people. But, if the attacker had used properties of other person while<br />

committing an illegal attack as means of that attack, then, in case of<br />

violation those properties, there is necessary defence 39 .<br />

3) Defence has to be simultaneous with attack.-Defence is simultaneous<br />

38<br />

presuda Vrhovnog suda Srbije Kž. 1355/94<br />

39<br />

Draan Jovašević, Tarik Hašimbegović, Osnovi isključenja krivičnog dela,<br />

Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, Beograd, 2001.p.50<br />

15<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

if it was undertaken at time when attack has been imminent or when it<br />

began, but only up to the moment when it ceased. Attack is imminent<br />

when, from all the circumstances, it could be concluded that it was<br />

about to start, and when there was such danger that violation of legal<br />

property would occur in the next moment. The beginning of an act<br />

which could have direct consequences (death, physical injury, taking<br />

away, destroying or damaging property) is not crucial for beginning of<br />

the attack. Undertaken action which objectively represents imminent<br />

source of danger is essential.<br />

Whether an attack is imminent or not is a factual question which is<br />

being solved by court in each particular case. Only threat of imminent<br />

attack, without undertaking previous actions from which it can be<br />

concluded that the attack was imminent, could not be the reason for<br />

undertaking the act of defence. Defence of future attack is not excusable<br />

either, but still undertaking of some measures of precaution and some<br />

protective measures which start to work automatically in the moment<br />

when the attack starts (like various alarm systems connected with<br />

electrical circuit) is allowed.<br />

When the attack has started, defence could begin in the same moment.<br />

But, it often happens that the attacked person is not in position to react<br />

at the same time when the attack starts. In that case defence could be<br />

undertaken at any time during the attack. Continuity of defence has to<br />

coincide with the continuity of attack. When the attack has stopped, the<br />

right of the attacked on necessary defence stops, too. An attack was<br />

ended if legal property of the attacked person has been violated and<br />

when danger has been caused (as a kind of consequence in cases of<br />

criminal acts of endangering), and when the attacker has committed the<br />

action of attack, but due to accidental circumstances there was no<br />

violation of property of the attacked person.<br />

The right for necessary defence stops if the attack has finally and<br />

definitely ceased, but not in case when the attack was only temporarily<br />

ceased. Whether an attack has ceased or only temporarily ceased is a<br />

factual question which is being solved by court in each particular case.<br />

Attack has temporarily ceased if there is a possibility that it could be<br />

16<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

continued any moment.<br />

4) Defence has to be necessary for protection from attack.-It is the<br />

defence which exists in case when attack cannot be prevented from in<br />

any other way except for violating the attacker’s property. This means<br />

that violation of attacker’s property has to be necessary, unavoidable in<br />

order to protect from the attack, so the intensity of defence is<br />

correspondent to the intensity of the attack and the manner and means<br />

which were used by attacker. When judging this necessity of defence,<br />

the equivalence between intensity of attack and intensity of defence in<br />

each particular case should be taken into consideration. On the other<br />

hand, this proportion means that violation of the attacker’s property is<br />

proportional with value of the property of the attacked person which<br />

was saved in this way.<br />

Violation of necessary defence<br />

If an attacked person, during the protection from attack on his or<br />

someone else’s legal property, oversteps the limits of defence which is<br />

necessary for protection from that attack, there is violation or excerpt of<br />

necessary defence has prescribed in article 9. paragraph 3. Basic<br />

Criminal Code and article 10. paragraph 3. Criminal code of the<br />

Republic of Montenegro.<br />

This violation, according to intensity, exists when violated property of<br />

the attacker is of greater value then the property saved in this way.<br />

Another kind of violation of necessary defence, according to broadness,<br />

exists in case when the attacked person returns an attack which hasn’t<br />

even started or hasn’t been imminent, or if he/she continues violating<br />

the attacked property after the attack has finally and definitely stopped.<br />

In these cases court is authorised to mitigate the sentence for a<br />

perpetrator of criminal act in violation of necessary defence. In case<br />

when violation of necessary defence was due to strong irritation or<br />

freight of the attacked person, court is authorised to release a perpetrator<br />

of such criminal act from the legal sentence.<br />

17<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

BASIC LITERATURE<br />

Avakumović Djordje, Teorija kaznenog prava, Beograd, <strong>18</strong>87-<strong>18</strong>89.<br />

Babić Miloš, Krivični zakonik Republike Srpske, Banja Luka, 2001.<br />

Babić Miloš, Komentari krivičnih zakona u Bosni i Hercegovini,<br />

Sarajevo, <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

Bačić Franjo, Komentar Kaznenog zakonika Republike Hrvatske,<br />

Zagreb, <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

Bavcon Ljubo – Šelih Alenka, Kazensko pravo, Splošnij del, Ljubljana,<br />

1987.<br />

Compendio di diritto penale, Parte generale e speciale, Milano, 2004.<br />

Đurđić Vojislav – Jovašević Dragan, Međunarodno krivično pravo,<br />

Nomos, Beograd, 2003.<br />

Đurđić Vojislav – Jovašević Dragan, Praktikum za krivično pravo, Prva<br />

knjiga, Opšti deo, Službeni glasnik, Beograd, 2003.<br />

Đurđić Vojislav – Jovašević Dragan – Zdravković Ljubiša, Nužna<br />

odbrana u krivičnom pravu, Niš, 2004.<br />

Ebert Udo, Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Heidelberg, 1993.<br />

Foregger Eugen- Serini Egmont, Strafecht, Gesetzbuch, Wien, 1989.<br />

Gropp Walter, Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Berlin, Heidelberg, New<br />

York, 1998.<br />

Horvatić Željko- Šeparović Miroslav, Novo hrvatsko kazneno pravo,<br />

Informator, Zagreb, 1997.<br />

Horvatić Željko – Novoselac Petar, Kazneno pravo, Opći dio, Zagreb,<br />

2001.<br />

Jescheck H.H., Lehrbuch des Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Berlin, 1972.<br />

Jovanović Ljubiša – Jovašević Dragan, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo,<br />

Nomos, Beograd, 2002.<br />

Jovašević Dragan , Leksikon krivičnog prava, Službeni list, Beograd,<br />

2002.<br />

Jovašević Dragan, Komentar Krivičnog zakona SR Jugoslavije,<br />

Službeni glasnik, Beograd, 2002.<br />

Jovašević Dragan – Hašimbegović Tarik, Osnovi isključenja krivičnog<br />

dela, Institut za kriminološka i sociološka istraživanja, Beograd, 2001.<br />

Kambovski Vlado, Krivičen zakonik so kratok objasnuvanja i registar<br />

na poini, Skoplje, 1996.<br />

Kambovski Vlado, Krivično pravo, Opšt del, Skoplje, <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

<strong>18</strong><br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Koržanskij M.I., Popularnij komentar Kriminolnogu kodeksu, Naukova<br />

dumka, Kiev, 1997.<br />

Lazarević Ljubiša, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Savremena<br />

administracija, Beograd, 2003.<br />

Lazarević Ljubiša- Vučković Branko- Vučković Vesna, Komentar<br />

Krivič nogzakonika Republike Crne Gore, Cetinje, 2004.<br />

Lolis Nicholas – Mangakis Georgis, The Greek penal code, London,<br />

1973.<br />

Marjanovik Gorgi, Krivično pravo, opšt del, Skoplje, 1998.<br />

Nenov Ivan, Nakazateljno pravo, Obša čast, Paralaks, Norma, Sofija,<br />

1993.<br />

Novoselec Petar, Krivično pravo, Krivično djelo i njegovi elementi,<br />

Osijek, 1990.<br />

Pagle C.D., Criminal lae of the People's Republic of China, Peking,<br />

1997.<br />

Pavišić Berislav, Komentar Kaznenog zakonika Republike Hrvatske ,<br />

Rijeka, 2003.<br />

Petrović Borislav – Jovašević Dragan, Krivično (kazneno) pravo Bosne<br />

i Hercegovine, Opći dio, Sarajevo, <strong>2005</strong>.<br />

Roxin Claus, Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Band 1, Munchen, 1997.<br />

Schweiserisches Strafgesetzbuch, Stand Am 1. April 1996., Bern, 1997.<br />

Skuratov J.I.- Lebedov V.M., Kommentarii k Ugolovnomu kodeksu v<br />

Rossijskoj federacii, Norma, Moskva, 1996.<br />

Stefani G., Levasseur G., Bouloc B., Droit penal general, Pars, 1994.<br />

Stojanović Zoran, Krivično pravo, Opšti deo, Službeni glasnik,<br />

Beograd, 2000.<br />

Stojanović Zoran , Komentar Krivičnog zakona SR Jugoslavije,<br />

Beograd, 1999.<br />

Šilović Josip, Nužna odbrana, Zagreb, 1910.<br />

Trifterer Otto, Ostereischisches Strafrecht, Allgemeiner teil, Wien,<br />

Berlin, New York, 1994.<br />

Zlatarić Bogdan, Krivični zakonik u praktičnoj primjeni, Opći dio, Prvi<br />

svezak, Zagreb, 1958.<br />

Zlatarić Bogdan – Damaška Mirjan, Rječnik krivičnog prava i postupka,<br />

Zagreb, 1960.<br />

Živanović Toma, Krivično pravo Kraljevine Jugoslavije, Beograd,<br />

1935.<br />

19<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

20<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - HUMAN RIGHTS IN LIGHT OF NECESSARY DEFENCE IN<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> OF SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND<br />

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS OF<br />

INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE<br />

BY DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ*<br />

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS<br />

When the Roman Statute of permanent International Criminal Court<br />

came into force in the middle of 2002, international criminal law and<br />

international criminal justice – have finally been constituted. It is in the<br />

beginning on XXI century. It is a system of legal regulations contained<br />

within the documents of the international community and national<br />

criminal legislations which determine the concept and characteristics of<br />

international criminal offences, the system of criminal responsibility<br />

and punishments , as well as the bodies and procedures to pronounce<br />

penalties to perpetrators of the most serious crimes against humanity,<br />

peace and international security. This finally brings into life centuries<br />

long idea of establishing universal criminal justice, or justice superior to<br />

national ones, which would pronounce penalties for breaches of<br />

international rules of conduct of states and individuals.<br />

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF INTERNATIONAL<br />

CRIMINAL <strong>LAW</strong> AND JUSTICE<br />

The appearance and development of international criminal law and<br />

international criminal justice in the recent history can be devided into<br />

three periods : 1) up to the First World War, 2) between the two World<br />

Wars and 3) after the Second World War to today 1 .<br />

* Dragan Jovašević PhD, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law in Nis,<br />

Serbia and Montenegro.<br />

1<br />

Đurđić V., Jovašević D., Medjunarodno krivično pravo,Nomos, Beograd,<br />

2003.p.25-35<br />

21<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

In the first period, the appearance and the development of the<br />

international criminal law was tightly connected with international laws<br />

of war – a special branch of the law that regulates relations between<br />

states, separately belligerents and establishes concrete legal rules of how<br />

a war is started and ended and procedure against civil people, war<br />

prisoners and wounded 2 .<br />

The sources of international criminal law of that time can be found in<br />

the significant codification documents of international laws of war such<br />

as : 1) the Paris Declaration of <strong>18</strong>56. (which provides the principles<br />

according to which goods of neutral countries can’t be seized in<br />

maritime conflicts and piracy is prohibited), 2) the Geneva Convention<br />

of <strong>18</strong>64.(which regulates the position and prohibition of the wounded in<br />

land conflicts), 3) the Petrograd Convention of <strong>18</strong>68. (which prohibits<br />

the usage of explosive grains that weigh less than 400 gr) and 4) the<br />

Hague Conventions of <strong>18</strong>99. and 1907. (which regulate the position and<br />

prohibition of the wounded and civilian in war). It is beginning of new<br />

branch of penal law in XIX century 3 .<br />

In the second period, the period between the two World Wars, following<br />

up the above mentioned legal sources, a number of important<br />

international legal documents were adopted : 1) the Geneva<br />

Conventions of 1919. (which regulate the position and prohibition of the<br />

wounded, sick men and war prisoner), 2) the Geneva Protocol of 1925.<br />

(which prohibits the usage of poison gas and bacteriological means), 3)<br />

the Paris or Briand-Kellog Pact of 1928. (which prohibition a war as<br />

instrument of international politics) and 4) the London Protocol of 1936.<br />

(which regulate the rules of submarine war) 4 .<br />

Besides these normative activities, that under the strong impression of<br />

the previous war, the issue of concrete individual criminal responsibility<br />

was raised for the first time in the international legal system. Pursuant to<br />

2<br />

Radojković M., Rat i medjunarodno pravo,Beograd, 1947.p.12-31<br />

3<br />

Schwarzenberger G. , The Law of the Armed Conflict,London, 1968.<br />

4<br />

More : Lopičić J., Ratni zločin protiv ratnih zarobljenika, Naša knjiga, Beograd,<br />

<strong>2005</strong>.p.13-42<br />

22<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

articles 227. and 230. of the Versailles Peace Treaty from 1919., the<br />

question of the criminal responsibility of German Emperor William II<br />

Hohenzollern, for ‘’a supreme offence against international morality and<br />

the sanctity of treaties has been raised’’. These articles also have<br />

stipulated the constitution of a special ad hoc tribunal to try the accused<br />

highest german state officials upon very serious charges for committing<br />

an act in violation of the laws and customs of war and high principles of<br />

humanity 5 . However, the justice was not served because the former<br />

german emperor was given asylum in the Netherlands which rejected<br />

the request for fih extradiction 6 .<br />

The third period of historical development of international criminal law<br />

is the period after Second World War. This period is marked by the<br />

most virgorous activity and development of this the most joungest<br />

branches of the modern penal law – international criminal law in<br />

therecent history. This is understandable keeping in mind that the world<br />

was faced with more informations about many millions of innocent<br />

victims and invaluable material damage. The knowlwdgw of<br />

individuals, organizations and countries that led to such tragical<br />

consequences had a significant impact on the final decision to raise the<br />

question of criminal responsibility in a proper manner 7 .<br />

Starting from principles of the protection of universal human values and<br />

general interests and then the principle that violations of international<br />

public law have to be sanctioned and that responsibility is not only<br />

historical, morarly and political question or a question of civil law, the<br />

international responsibility of states and the individual (and command)<br />

criminal responsibility have come to the forefront. The changed<br />

approach to the issue of responsibility was founded on the theory to<br />

application the principle of territory, universal values and protection 8 .<br />

In this period , the most important codification of international criminal<br />

5<br />

Lopičić J., Ratni zločin protiv civilnog stanovništva,Beograd, 1999.p.19-27<br />

6<br />

Perazić G., Medjunarodno ratno pravo, Beograd, 1986.p.16-19<br />

7<br />

Avramov S., Kreća M., Medjunarodno javno pravo,Beograd, 1981.p.14-23<br />

8<br />

Leon F., The Law of War, New York, 1972.p.56<br />

23<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

law included the famous Nuremberg Principles ( which were contain in<br />

the Nuremberg judgment from 1948.). Also, this judgment has definited<br />

of new international criminal offences. Pursuant to the United Nations<br />

Security Council Resolution from 1946. the Commission for the<br />

Codification of International law was founded with the purpose of<br />

establishing new principles of international criminal law and of drafting<br />

a new International criminal code.<br />

The draft Code of Crimes against Peace and Security of Mankind was<br />

published in 1954. and it was composed of thirteen articles with<br />

concrete international criminal offences 9 . The work was followed up by<br />

the United Nations International Law Commission which among other<br />

things, was the first to discuss the foundation of a special international<br />

criminal court. Such an approach was supported by the United Nations<br />

Security Council Resolution from 1968. by which the UN Convention<br />

on Unexpirability of International criminal offences ( genocide, was<br />

crimes , crimes against peace and crimes against humanity) was<br />

adapted. In the period from 1980. till July 1998.(Roma Statute), that<br />

Commission has kept on working, specially on the draft Statute of the<br />

permanent International criminal court 10 .<br />

ESTABLISMENT OF AD HOC MILITARY TRIBUNALS<br />

After the victory ver fascism, the question of individual criminal<br />

responsibility for committed crimes war raised again. The legal bases<br />

were the Declaration Concering Atrocities and conclusions of the<br />

Moscow Conference of the Allies from <strong>October</strong> 1943. and the London<br />

Agreement from August 1945. on the established of the International ad<br />

hoc Military Tribunal and on the punishment of war criminals. the<br />

constituent part of this legal document were the Agreement of the Allies<br />

to Try and Punish Major War Criminals of the European Axis and the<br />

Statute of the Military tribunal.<br />

9<br />

V. Vasilijević, Medjunarodni krivični sud, Beograd, 1961.p.34-52<br />

10<br />

Brownlie J., Basic Documents in International Law,Oxford, 2002<br />

24<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Military tribunal in Nuremberg tried the highest military and political<br />

officials of the Third Reich who were accused of initiating the<br />

aggressive war, suffering, atrocities, destructions, crimes against<br />

humanity and war crimes. The criminal trial has started on November<br />

20,1945. and lasted more than two hundred days and the Prosecution<br />

entered indictments against twenty one major war criminals. The<br />

verdicts were announced on <strong>October</strong> 1, 1946 : eleven sentences to death<br />

hanging , three sentences to life imprisonment, four sentences to longer<br />

terms and three acquittals. The verdicts of guilty were handed down on<br />

the leadership and the organizations of the SS, NSDAP, SD and the<br />

Gestapo and these organizations were declared criminal. This is s first<br />

judgment which the legal entities has proclaimed criminal responsibility<br />

because committing war crimes.<br />

The real jurisdiction of this international military tribunal was<br />

determined by article 6. of the Statute (in London Agreement) pursuant<br />

to which international criminal offences were classified into three<br />

categories : 1) crimes against peace, 2) war crimes and 3) crimes<br />

against humanity. The territorial jurisdiction of the tribunal included<br />

implicitly the prosecution of the Second World War war criminals<br />

‘’whose criminal offences do not have some specific geographical<br />

commitment, regardless the fact whether they will be accused<br />

individually or as members of an organization or a group or in both<br />

capacities’’.<br />

Second military ad hoc tribunal 11 was established in Tokyo pursuant to<br />

the Declaration of the military commander, american general Daghlas<br />

Macarthur of allies January 16. 1946. with the purpose of trying<br />

japanese war criminals for war crimes committed in the Far East. The<br />

process in Tokyo has started on April 29. 1946. and lasted till<br />

November 12. 1948. with the result that twenty eight persons were<br />

pronounced guilty for committing war crimes (specialy war crimes<br />

against war prisoners). During the proccedings four perons died, one<br />

was pronounced insane and the criminal proccedings against him was<br />

stayed. The Tokyo military tribunal passed the following sentences :<br />

11<br />

Josipović I., Haško implenetacijsko kazneno pravo,Zagreb, 2000. p.45-62<br />

25<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

seven dealth penalties, fourteen life imprisonment sentences and two<br />

persons were sentenced to prison with various terms 12 .<br />

In short, legal proccedings before ad hoc tribunals in Nuremberg and<br />

Tokyo contrinuted significantly to the afirmation of principles of<br />

individual criminal responsibility, command responsibility (in Tokyo<br />

judgement), system international criminal offences, and to the<br />

development of international criminal law and especially to the<br />

institutionalization of the idea of international criminal justice 13 . The<br />

end XX century give first permanent international (Roma) criminal<br />

court in Hague 14 .<br />

HAGUE TRIBUNAL (ICTY) FOR FORMER<br />

SFR YUGOSLAVIA<br />

The international tribunal for criminal procesution of persons<br />

responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law<br />

committed in the teritory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991.<br />

(International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia – ICTY) is one<br />

of ad hoc tribunals established after strong indications of war crimes or<br />

crimes against humanity committed in war conflicts in the territory of<br />

the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). This<br />

tribunal was established by the United Nations Security Council<br />

Resolution No. 827/93 from May 25,1993. and accordance with the<br />

previous acts issued by the same body – Resolution No. 780/92 from<br />

<strong>October</strong> 6. 1992 and Resolution No. 808/93 from February 22. 1993. In<br />

the material legal sense of meaning, this international ad hoc tribunal is<br />

authorized to investigate alleged war crimes belonging to the group of<br />

legal principles of the Nuremberg (1946.) and Tokyo (1948.)<br />

Tribunales Judgements and Code of the crimes against peace and safety<br />

of Mankind and to establish cempetenlty the individual responsibility<br />

12<br />

Perazić G., Međunarodno ratno pravo,Beograd, 1986. p.14-31<br />

13<br />

C.Van den Wyngaert, International criminal law, Kluwer, Hague, London,<br />

Boston, 2001.p.12-34<br />

14<br />

UN. Doc. A/Conf. <strong>18</strong>3/9, International Legal Materials, 1999.<br />

26<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

for concrete international criminal acts 15 .<br />

Similar ad hoc tribunales with similar jurisdiction, system international<br />

criminal offences and rules about criminal responsibility and<br />

punishments have established United Nations Security Council as : 1)<br />

International criminal tribunal for Rwanda which established of Security<br />

Council Resolution No.955/94 from November 8. 1994 16 , 2) Special<br />

court for Sierra Leone which established of Security Council<br />

Resolution No 1315/2000 from August 14, 2000 and 3) Iraqi special<br />

tribunal which established of the Statute of the Iraqi special tribunal<br />

from December 10. 2003 17 .<br />

The establishment of the Hague tribunal attracted large attention of the<br />

whole world, especially of expert circles in Serbia and Montenegro and<br />

abroad. The first remark is deal with statutory questions. Legal<br />

representatives and the accused raised most often the question of the<br />

legality of the establishment, existence and functioning of ad hoc<br />

tribunals <strong>18</strong> .<br />

The second remark is deal with the defense of the accused. Some legal<br />

representatives of the Defense have pointed out that they do not have<br />

the same effective abilities as the Prosecution, especially in the very<br />

important phase of evidence collection and finding witnesses 19 . Defense<br />

are significantly of the protected witness because the identity of the<br />

witness is not revealed till the trial and it is not possible to contact that<br />

group of persons till the very moment of having the main hearings 20 .<br />

Third remark is deal with the tribulal procedure and the trial in absentia.<br />

15<br />

Vasilijević V., Međunarodni krivični sud,Beograd, 1961.p. 64-68<br />

16<br />

Blakesley Ch., Definition and Triggering Mechanism, The International<br />

criminal court, AIDP,1997.<br />

17<br />

www. cpa-iraq.org/human _rights/statute.htm<br />

<strong>18</strong><br />

Josipović I., Haško implementacijsko kazneno pravo, Zagreb, 2000.p. 124-141<br />

19<br />

Đurđić V., Jovašević D., Međunarodno krivično pravo, Beograd, 2003. p. 33-<br />

34<br />

20<br />

More about remarks against Hague Tribunal in theory criminal law in Serbia<br />

and Montenegro : Stojanović Z., Međunarodno krivično pravo, Beograd, 2002.<br />

27<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Pursuant article 61. of the Statuet of Hague Criminal Tribunale (ICTY)<br />

there is a possibility to initiate proceedings against a person who<br />

currently can’t be accessed by the Tribunal in Hague under the<br />

condition that the indictment against the person has already been raised<br />

and the procedure of brining evidence has been initiated. Here again, the<br />

Hague Tribunal has wide authorities and a possibility to initiate the<br />

proceedings to rewiev and reconfirm the indictment, to declare<br />

internationally a wanted person and to make all countries collaboration.<br />

The participation of the Defense attorneys at this stage is not permitted<br />

and it is conditioned by the first appearance of the accused before the<br />

Tribual 21 . Up to that moment, the Defense attorneys may participate in<br />

the process only as spectators.<br />

REWIEV ON COLLABORATION BETWEEN SERBIA AND<br />

MONTENEGRO AND HAGUE TRIBUNAL<br />

The Dayton-Paris Peace Agreement that was signed in the end of 1995.<br />

(which finnished civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina) established a<br />

whole range of obligations assigned to all signatories.Among other<br />

things, by singing the agreement the signatories undoubtedly<br />

acknowledged and accepted the existence and activity of the Hague<br />

Tribunal (ICTY) and have undertaken upon themselves the international<br />

legal obligation to collaboration with this Tribunale in Hague. As a<br />

signatory, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (today Serbia and<br />

Montenegro from February 4. 2003 22 .) similarly has undertaken this<br />

and other international obligations, keeping in mind that the same issue<br />

was regulated directly or indirectly by the internal legislation and<br />

numerous previously enacted international documents (as United<br />

Nations Security Council resolutions, conventions, agreements etc).<br />

The collaboration between a government in Belgrade and the Hague<br />

Tribunal evolved in several periods between from 1995. to <strong>2005</strong>. In the<br />

21<br />

Đurđić V., Jovašević D., Međunarodno krivično pravo, Beograd, 2003. p. 117-<br />

1<strong>18</strong><br />

22<br />

Official Gazette of Serbia and Montenegro No. 1/2003<br />

28<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

first period (1995.-2000), the relationship between the FR Yugoslavia<br />

and the Hague Tribunal was hampered with political antagonism,<br />

general lack of trust, politics of the international community that was<br />

expressed by making conditions and putting pressure. The official<br />

bodies of government in Belgrad ( competent organs of the Federal<br />

Republic of Yugoslavia or competent organs of the Republic of Serbia)<br />

at the time did not manage to harmonize their relations with other<br />

relevant key players of the international relations (in international<br />

community) above all the United States or their European allies.<br />

After the change power in FR Yugoslavia (after presidental elections in<br />

Octobar 2000.) aarived the second period in relationship and<br />

collaboration between FR Yugoslavia and Hague tribunal. This<br />

collaboration has have a many remarks and stoppages. From the point of<br />

view of internal law system, the legal situation was somewhat unclear<br />

and that led to delay in concrete forms of collaboration with the Hague<br />

Tribunal . First of all, this may be applied to the requests made by the<br />

Hague Tribunal to the FR Yugoslavia to extradite its citizens suspected<br />

of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity who are in the<br />

territory of our country. The dilemma about the collaboration with the<br />

Hague Tribunal appeared because of constitutional, political, legal and<br />

other reasons.<br />

Legal dilemmas appeared above all because of normative solutions of<br />

the Yugoslav Constitution (from 1992.) and Constitution of Republic of<br />

Serbia (from 1990.) and Code about Criminal Proceedings 23 (from 1976.<br />

with more novels) and especially because of the provision dealing with<br />

the extradition of Yugoslav citizens to foreign courts. In the legal<br />

vacuum, the Federal Government have tried to find legal form that<br />

would enable the protection of our national interest and to avoid the<br />

introduction of new sanctions of international community and fulfil the<br />

requests made by the Hague Tribunal. Till the federal law was enacted,<br />

the Federal Government as a temporary solution has adopted the<br />

Provision on the Collaboration Procedures with the International<br />

23<br />

Jekić Z., Krivično procesno pravo,Beograd, 1992.p.347-351 ; Đurđić V.,<br />

Krivično procesno pravo, Niš, 1998.p. 269-272<br />

29<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Criminal Tribunal 24 (2001.). According to this legal act, the rules<br />

dealing with the jurisdiction of the Hague Tribunal to undertake<br />

investigations in the FR Yugoslavia, the yielding of criminal<br />

proceedings led before Yugoslav courts, the appropriate application of<br />

the Code about Criminal Proceedings provisions, the issue of leagl<br />

assistance, the execution of the verdicts in the territory of the FR<br />

Yugoslavia etc. were established.<br />

The Federal Government of FR Yugoslavia has given priority to<br />

international law and direct application of the Statute of the Hague<br />

Tribunal, starting from the view that the Tribunal is as international<br />

institution and that the FR Yugoslavia has to respect all internationally<br />

undertaken obligations and norms of international public law and<br />

international criminal law. But, the Federal Constitution Court has<br />

passed the decision that this Provision does not comply with the<br />

Yugoslav Constitution and Code about Criminal Proceedings 25 . In its<br />

legal explanation, the Federal Constitution Court started from the<br />

opposite opinion in comparision to the Federal Government’s opinion,<br />

giving priority to the internal legal order.<br />

Starting from these facts, the government of the Republic of Serbia<br />

adopted a similar by law a special Provision on the Collaboration with<br />

the International Criminal Tribunal 26 (2002.). The enactment of the<br />

Republic act ‘’solved’’ the problem of collaboration with the Hague<br />

Tribunal for a very short period of time because internally there were<br />

still political disputes and no consensus in that respect. The adoption of<br />

the legal acts of a higher hierarchy was an imperative and more serious<br />

considerations started especially because of the international factor.<br />

Finally, the Federal Assembly of FR Yugoslavia adopted in 2002.the<br />

Code on the Collaboration of the FR Yugoslavia with the International<br />

Tribunal for criminal procesution of persons responsible for serious<br />

violations of international humanitarian law in territory of former<br />

24 Official Gazette of the FR Yugoslavia, No. 30/2001<br />

25 Official Gazette of FR Yugoslavia, No. 70/2001<br />

26<br />

Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 14/2002<br />

30<br />

DRAGAN JOVAŠEVIĆ - APPEARANCE, DEVELOPMENT AND BASIC<br />

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE

<strong>FREE</strong> <strong>LAW</strong> <strong>JOURNAL</strong> - VOLUME 1, NUMBER 2 (<strong>18</strong> OCTOBER <strong>2005</strong>)<br />

Yugoslavia from 1991 27 . This Code is short legal act and it has 41<br />

articles in total, classified in seven chapters that cover : 1) general<br />

provisions, 2) the authorities of the Tribunal to conduct investigation in<br />

the territory of the FR Yugoslavia, 3) the yielding of cases led before<br />

local courts, 4) the extradition of the accused, 5) legal help to the<br />

Tribunal, 6) the execution of the verdicts made by the Tribunal in the<br />

territory of the FR Yugoslavia and 7) other provosions 28 .<br />

In material-legal sense f meaning, the nature of this Code iz lex<br />

specialis in this matter. In the general provisions, special emphasis has<br />

been given to the principle of priority of international obligations<br />