Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: - Geisinger Health System

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: - Geisinger Health System

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: - Geisinger Health System

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Posttraumatic</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> <strong>Disorder</strong>:<br />

Findings from War & Disaster Studies<br />

Joseph A. Boscarino, PhD, MPH<br />

Senior Investigator-II<br />

The <strong>Geisinger</strong> Center for <strong>Health</strong> Research<br />

<strong>Geisinger</strong> Clinic<br />

Danville, PA<br />

July, 2007<br />

PTSD July 2007.ppt

History of <strong>Posttraumatic</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> <strong>Disorder</strong><br />

(PTSD)<br />

• Symptoms recognized during Civil War<br />

• Shell shock in World War I<br />

• Combat fatigue in World War II<br />

• Combat neurosis in Korean War<br />

• Acute stress reaction in Vietnam War<br />

• PTSD post-Vietnam War in 1980s – DSM-III<br />

• PTSD expanded in 1990s – DSM-IV

Recognition of PTSD post-Vietnam War<br />

• Returning veterans present adjustment<br />

problems/psychopathology<br />

• Veteran advocates label “Vietnam Veteran<br />

Syndrome” (VVS)<br />

• Advocates lobby to have VVS in recognized<br />

• DSM-III committee of APA agreed but required<br />

compromise<br />

• Compromise was it would be called PTSD &<br />

also apply to rape/abuse victims and<br />

others; Incorporated in DSM-III in 1980

PTSD in US Civil War

PTSD Diagnosis in 1994 – DSM-IV<br />

• A1. Exposure to traumatic event (now broadly<br />

defined & subjective)<br />

• A2. Experienced fear, helplessness, horror<br />

• B. Re-experiences traumatic event<br />

• C. Avoid stimuli associated with event<br />

• D. Experiences hyper-arousal symptoms<br />

• E. Duration of symptoms > 1 month<br />

• F. Symptom cause distress or impairment

Prevalence of Traumatic Event Exposure<br />

• Lifetime experience of qualifying<br />

traumatic even in U.S.: 60-90% 1,2,3,4<br />

• Lifetime prevalence of crime/aggravated<br />

assault: 36% 2<br />

• Prevalence higher in recent surveys<br />

using DSM-IV criteria<br />

1. Norris, FH. 1992. J Conslt Clin Psychol, 60:409-418<br />

2. Resnick, H. 1993. J Consult Clin Psychol, 61:984-991<br />

3. Breslau, N. 1998. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 55:626-632<br />

4. Kessler, R. 1995. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 52:1048-1060

Prevalence of PTSD<br />

• General population prevalence of PTSD in<br />

U.S.: 7.8-9.2% 1,3<br />

• Women twice as likely as men to have lifetime<br />

PTSD 1<br />

• Conditional risk of PTSD after<br />

sexual/aggravated assault: 20-60% 1,2,3<br />

• Conditional risk of PTSD after community<br />

disaster: 3.7 for men and 5.4% for women 1<br />

1. Kessler, R. 1995. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 52:1048-1060<br />

2. Resnick, H. 1993. J Consult Clin Psychol, 61:984-991<br />

3. Breslau, N. 1998. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 55:626-632

PTSD <strong>Stress</strong>or Model<br />

Exposure<br />

Trauma Exposure<br />

Acute<br />

PTSD Sx Occur after Exposure<br />

Chronic<br />

Long-term Psychological Distress,<br />

PTSD, Co-morbid PTSD, etc.

PTSD and the Brain

PTSD – Potential<br />

biologic mechanisms affected<br />

<br />

Hypthalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system<br />

- e.g.,Cortisol down-regulation<br />

<br />

<br />

Sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system<br />

- e.g., Catecholamine up-regulation<br />

Autonomic nervous (AN) system:<br />

- e.g., Hyper-reactivity/startle response increased<br />

These alterations may directly/indirectly increase<br />

“allostatic” load and may lead to disease in some<br />

individuals

Findings in 2006: PTSD and health<br />

<br />

<br />

Many Populations Studied:<br />

Disaster & Terrorism Victims, Veterans,<br />

Sexual & Physical Assault Victims, POWs,<br />

Refugees, Concentration Camp Survivors<br />

Many <strong>Health</strong> Outcomes Examined:<br />

Mental <strong>Health</strong> Status, Cardiovascular Disease,<br />

Diabetes, GI Disease, CFS, Musculoskeletal<br />

Disease, Neurological <strong>Disorder</strong>s, Chronic Pain,<br />

Somatic <strong>Disorder</strong>s, Lower Functional Status,<br />

Higher <strong>Health</strong>care Use, Mortality

PTSD Consequences among War-Fighters<br />

Joseph A. Boscarino, PhD, MPH<br />

Senior Investigator-II<br />

The <strong>Geisinger</strong> Center for <strong>Health</strong> Research<br />

Danville, PA<br />

PTSD_pres 2006.ppt

Veterans Study References<br />

J.A. Boscarino, S.N. Hoffman SN. Consistent association between mixed lateral preference and<br />

PTSD: Confirmation among a national study of 2,490 US Army Vietnam veterans. Psychosomatic<br />

Medicine 69: 2007, 365-369.<br />

J.A. Boscarino. PTSD and Mortality among US Army Veterans 30 Years after Military Service,<br />

Annals of Epidemiology, 16: 2006, 248-256.<br />

J.A. Boscarino. <strong>Posttraumatic</strong> <strong>Stress</strong> <strong>Disorder</strong> and Physical Illness: Results from<br />

Clinical & Epidemiologic Studies. Annals of NY Academy of Sciences 2004; 1030: 141-153.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, J. Chang. Higher Abnormal Leukocyte and Lymphocyte Counts 20 Years after<br />

Exposure to Severe <strong>Stress</strong>: Research and Clinical Implications. Psychosomatic Medicine 61: 1999,<br />

378-386.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, J. Chang. Electrocardiogram Abnormalities among Men with <strong>Stress</strong>-Related<br />

Psychiatric <strong>Disorder</strong>s: Implications for Coronary Heart Disease and Clinical Research. Annals of<br />

Behavioral Medicine 21: 1999, 227-234.<br />

J.A. Boscarino. Diseases among Men 20 Years after Exposure to Severe <strong>Stress</strong>: Implications for<br />

Clinical Research and Medical Care. Psychosomatic Medicine 59: 1997, 605-614.<br />

J.A. Boscarino. Post-Traumatic <strong>Stress</strong> <strong>Disorder</strong>, Exposure to Combat, and Lower Plasma Cortisol<br />

among Vietnam Veterans: Findings and Clinical Implications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical<br />

Psychology 64: 1996, 191-201.<br />

J.A. Boscarino. Post-Traumatic <strong>Stress</strong> & Associated <strong>Disorder</strong>s among Vietnam Veterans: The<br />

Significance of Combat Exposure and Social Support. Journal of Traumatic <strong>Stress</strong> 8: 1995, 317-36.

Vietnam Experience Study<br />

(diseases 17 Years Post-discharge; N = 2,490)<br />

48,513 Theater<br />

and Era Veterans<br />

1985-86<br />

From 4.9 Million<br />

1985-86<br />

7,924 Theater Vets<br />

Contacted for Phone<br />

Interview (CR=87%)<br />

7,364 Era Vets<br />

Contacted for Phone<br />

Interview (CR=84%)<br />

2,490 Theater Vets<br />

Underwent Examinations<br />

and Tests (CR=75%)<br />

1,972 Era Vets<br />

Underwent Examinations<br />

and Tests (CR=63%)<br />

CR=Completion Rate

Adjusted Plasma Cortisol Concentrations among<br />

Theater Veterans by Combat Exposure (p for trend

PTSD Biology

Logistic Regression Predicting Abnormal ECG for Veterans by<br />

Current PTSD, Complex PTSD & General Anxiety (N=2,490)<br />

PTSD Complex PTSD GAD<br />

ECG Classification OR OR OR<br />

Q-Wave Infarctions (n=30) 4.6** 2.6* 1.5<br />

Arrhythmias (n=209) 1.9 2.0** 1.5<br />

AV Conduction Def. (n=78) 2.9** 1.7 0.4<br />

Any Abnormal ECG (n=365) 2.0** 1.5* 1.6**<br />

(n=) (54) (124) (123)<br />

*p< 0.10 **p< 0.05<br />

Boscarino & Chang. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 21: 1999, 227-234.

Specific Autoimmune Diseases among<br />

Theater Veterans by Complex PTSD (N=2490)<br />

AD Type<br />

Adjusted*<br />

O.R. (O.R. 95% C.I.) p-value<br />

Rheum. Arthritis 5.2 (2.3-11.9)

Logistic Regression: PTSD and Mixed Handedness<br />

plus High Combat Exposure (N=2490)<br />

Adjusted*<br />

Mixed + High Combat O.R. (O.R. 95% C.I.) p-value<br />

Edinburgh +/- 70 2.5 (1.6-3.7)

PTSD Symptoms by Combat Exposure & Handedness

Clinical Profile of PTSD Cases (n=124)<br />

among Vietnam Veteran Cohort (N=2490)<br />

• T-lymphocytes counts above normal range (p

PTSD, Inflammation & Disease: Pathogenesis of RA

Trauma and <strong>Health</strong>: Cardiovascular Disease<br />

Vietnam Veterans: Population Study (Boscarino & Chang, 1999)<br />

- Increase abnormal 12-lead ECGs (e.g., Q-wave infarcts)<br />

WW II & Korean Vets: Population Study (Schnurr et al. (2000)<br />

- Increase in physician-diagnosed arterial disease<br />

• Dutch Resistance Vets: Population Study (Falger et al. 1992)<br />

- Increase in reported angina pectoris<br />

• Ex-POWs: Clinical Study (Corovic et al. 2000)<br />

- Increase in abnormal 12-lead ECGs (e.g., Q-wave infarcts)<br />

• Beirut Civil War Civilians: Clinical Study (Sibai et al. 1989)<br />

- Increase in arteriographic coronary artery disease<br />

Chernobyl Disaster: Population Study (Cwikel et al. 1997)<br />

- Increase in reported heart disease<br />

Childhood Trauma: Population Study (Felitti et al., 1998)<br />

- Increase in adult ischemic heart disease based on exam<br />

• Sexual Assault History: Population Study (Golding 1994)<br />

- Increase in cardiovascular disease symptoms

Vietnam Experience Study<br />

(Deaths 30 Years Post-discharge; N = 15,288)<br />

1985-86<br />

2000<br />

7,924 Theater Vets<br />

Contacted for Phone<br />

Interview (CR=87%)<br />

7,924 Theater Vets<br />

Vital Status Determined<br />

(CR > 95%)<br />

48,513 Theater<br />

and Era Veterans<br />

From 4.9 Million<br />

7,364 Era Vets<br />

Contacted for Phone<br />

Interview (CR=84%)<br />

7,364 Era Vets<br />

Vital Status Determined<br />

(CR > 95%)<br />

1985-86<br />

2000<br />

CR=Completion Rate

Profile of Vietnam Theater vs. Era Veterans<br />

(N=15,288)<br />

Variables Theater Era P-value*<br />

PTSD at interview 10.6 2.9

Profile of PTSD Positive vs. PTSD Negative Veterans<br />

(N=15,288)<br />

Variables Negative Positive P-value<br />

Dead at 2000 at follow-up 4.9 11.8

Cox Regression: Mortality among all Veterans<br />

by PTSD Status (Person-years at risk =229,565)<br />

(N=15,288)<br />

Cause of Death<br />

Adjusted*<br />

H.R. (H.R. 95% C.I.) p-value<br />

All cause (n=820) 2.1 (1.7-2.6)

Cox Regression: Mortality among Era Veterans<br />

by PTSD Status (Person-years at risk = 110,553)<br />

(N=7,364)<br />

Cause of Death<br />

Adjusted*<br />

H.R. (H.R. 95% C.I.) p-value<br />

All cause 2.0 (1.3-3.0) 0.001<br />

CVD 1.2 (0.4-3.4) 0.69<br />

Cancer 0.9 (0.3-3.1) 0.92<br />

External** 2.2 (0.9-5.2) 0.073<br />

*Adjusted for race, age, IQ, military history, smoking history.<br />

** External cause = homicide, suicide, drug overdose,<br />

accidents of undermined intent, etc.<br />

Boscarino. Annals of Epidemiology, 16: 2006, 248-256.

Cox Regression: Mortality among Theater Veterans<br />

by PTSD Status (Person-years at risk = 119,453)<br />

(N=7,364)<br />

Cause of Death<br />

Adjusted*<br />

H.R. (H.R. 95% C.I.) p-value<br />

All cause 2.2 (1.7-2.7)

Veteran study conclusions<br />

• Veterans with current PTSD had for years - since acquired<br />

(mostly) from Vietnam combat - hence, could be causative<br />

for in disease<br />

• Vets were “disease free” at service induction and disease<br />

onset was post service, thus causal ordering correct<br />

• Current lymphocyte, cortisol, hormonal & DTH findings<br />

support the presence of “inflammatory” diseases among<br />

the veterans<br />

• Given above & the controls for bias & confounding, is<br />

plausible PTSD-related stress may cause disease among<br />

veterans<br />

• PTSD-behavioral psychopathogenesis is likely an<br />

additional factor for disease burden & cause of death

World Trade Center Disaster Study

Study Contributors<br />

• Joseph Boscarino, PhD, MPH – Study Director<br />

• Richard Adams, PhD<br />

• Charles Figley, PhD<br />

• Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH<br />

• Heidi Resnick, PhD<br />

• Edna Foa, PhD<br />

• Joel Gold, MD<br />

• Michael Bucuvalas, PhD<br />

• David Vlahov, PhD

WTCD Study References<br />

J.A. Boscarino, RE Adams, CR Figley, S Galea, EB Foa. Fear of Terrorism and Preparedness in New York<br />

City 2 Years after the Attacks: Implications for Disaster Planning and Research. J Pubic <strong>Health</strong> Manag. &<br />

Practice. 12: 2006, 501-509.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, R.E. Adams, C.R. Figley. Worker Productivity and Outpatient Service Use after the September<br />

11 th Attacks. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 49: 2006.<br />

R.E Adams, J.A. Boscarino. Predictors of PTSD and Delayed-PTSD after Disaster: The Impact of Exposure<br />

and Psychological Resources. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194: 2006 485-493.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, R.E. Adams, E. Foa, P. Landrigan. A Propensity Score Analysis of Brief Worksite Crisis<br />

Interventions after the World Trade Center Disaster. Medical Care 44: 2006, 454-462.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, R.E. Adams, S. Galea. Alcohol use in New York after the Terrorist Attacks: A Study of the<br />

Effects of Psychological Trauma on Drinking Behavior. Addictive Behaviors 31: 2006, 606-621.<br />

R.E. Adams, J.A. Boscarino, S. Galea. Social and Psychological Resources and <strong>Health</strong> Outcomes after a<br />

Community Disaster. Social Science and Medicine 60: 2006, 176-188.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, RE Adams. Disparities in Mental <strong>Health</strong> Treatment following the World Trade Center Disaster:<br />

Implication for Mental <strong>Health</strong> Care and Services Research. J Traumatic <strong>Stress</strong> 18: 2005, 287-97.<br />

R.E. Adams, J.A. Boscarino. Differences in Mental <strong>Health</strong> Outcomes among Whites, African Americans, and<br />

Hispanics Following a Community Disaster. Psychiatry 68: 2005, 250-265.<br />

R.E. Adams, JA. Boscarino. <strong>Stress</strong> and Well-being in the Aftermath of the World Trade Center Attack: The<br />

Continuing Effects of Community-wide Disaster. Journal of Community Psychology 32: 2005, 175-190.

WTCD Study References<br />

J.A. Boscarino, R.E. Adams, C.R. Figley. Mental <strong>Health</strong> Service Use 1-Year after the World Trade<br />

Center Disaster: Implications for Medical Care. General Hospital Psychiatry 26: 2004, 346-358.<br />

D. Vlahov, S. Galea, H. Resnick, J. Ahern, J.A. Boscarino, M. Bucuvalas, J. Gold, D. Kilpatrick.<br />

Increased use of Cigarettes, Alcohol, and Marijuana among Manhattan residents after the<br />

September 11 th Terrorists Attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology 155: 2002, 988-996.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, C.R. Figley, R.E. Adams, S. Galea, H. Resnick, A.R. Fleischman, M. Bucuvalas, J.<br />

Gold. Adverse Reactions of Study Persons recently Exposed to Mass Urban Disaster. Journal<br />

of Nervous and Mental Disease 192: 2004, 515-524.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, S. Galea, R.E. Adams, J. Ahern, H. Resnick, D. Vlahov. Mental <strong>Health</strong> Service and<br />

Psychiatric Medication Use in New York City after the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attack.<br />

Psychiatric Services 55: 2004, 274-283.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, C.R. Figley, R.E. Adams. Fear of Terrorism in NY after the September 11 Attacks:<br />

Implications for Emergency Mental <strong>Health</strong> and Preparedness. International Journal of<br />

Emergency Mental <strong>Health</strong> 5: 2003, 199-209.<br />

J.A. Boscarino, S. Galea, J. Ahern, H. Resnick, D. Vlahov. Psychiatric Medication Use among<br />

Manhattan Residents following the World Trade Center Disaster. Journal of Traumatic <strong>Stress</strong><br />

16: 2003, 301-306.

Previous studies of<br />

persons after disasters<br />

• Most research focused on persons directly<br />

affected<br />

• Few studies examined outcomes in a<br />

large-scale population study<br />

• Major Research Question in Our Study:<br />

Were post-disaster interventions<br />

beneficial?

Study design<br />

• Wave 1 Random-digit-dial phone surveys 1-year<br />

after (N=2,368) –> adults only<br />

• Over-sample of persons who had treatment after<br />

WTC disaster (~ 80%)<br />

• 45-minute mental health/trauma survey used<br />

• Wave 2 phone survey 1-year after W1 (2 years<br />

post-disaster)<br />

• Re-interviewed 71% of W1 respondents in W2<br />

• Wave 1 + Wave 2 longitudinal data = 1,681<br />

persons

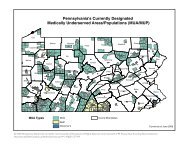

Study sampling frame – 5 NYC boroughs<br />

sampled probability proportionate to size<br />

(N = 2,368)

Study measures<br />

• Main Dx and service measures from<br />

National Co-morbidity Study*<br />

• Intervention exposure assessed<br />

‣Determined if respondent attended intervention<br />

after WTC disaster<br />

‣Where sessions were conducted<br />

‣Number of sessions attended<br />

‣Clinical focus of sessions<br />

‣Perceptions of how helpful sessions were<br />

*RC Kessler, et al. The Epidemiology of Major Depression. JAMA 2003;<br />

289: 3095-3105.

Study outcomes measures<br />

• Outcomes assessed:<br />

‣ PTSD past year (DSM-IV)<br />

‣ Depression past year (DSM-IV)<br />

‣ Binge Drinking past year (6+ drinks)<br />

‣ Alcohol Dependency past year (CAGE)<br />

‣ SF-12 functional status<br />

‣ BSI-18: Somatization, Global Severity Index<br />

‣ Worker Productivity<br />

‣ Outpatient mental & health services use<br />

‣ Non-traditional services use.

Sample characteristics of w1 & w2<br />

compared to 2000 U.S. Census for NYC<br />

Characteristics US Census % Weighted W1<br />

Sample %<br />

Age<br />

18-24<br />

13.2<br />

15.2<br />

25-34<br />

22.5<br />

24.0<br />

35-44<br />

20.8<br />

22.2<br />

45-54<br />

16.7<br />

18.7<br />

55-64<br />

11.3<br />

10.0<br />

65+<br />

15.5<br />

9.8<br />

Weighted W2<br />

Sample %<br />

12.7<br />

21.3<br />

22.1<br />

20.3<br />

12.0<br />

11.7<br />

Race<br />

White<br />

African American<br />

Asian<br />

Hispanic<br />

Other<br />

38.7<br />

23.0<br />

10.1<br />

24.7<br />

3.6<br />

39.2<br />

26.3<br />

5.2<br />

25.7<br />

3.5<br />

43.0<br />

26.0<br />

4.6<br />

24.1<br />

2.4

Prevalence of PTSD and Depression in NYC<br />

4 and 12 months after September 11<br />

PTSD/Depression 4 Months (Sx) 12 Months (Dx)<br />

PTSD Ever 15.3 8.2<br />

PTSD Since 9/11 9.1 5.3<br />

PTSD Past 6 months -- 3.4<br />

Depression Since 9/11 7.8 8.2<br />

Peri-Event Panic Attack 16.7 10.8

Mental health service use 1-year before vs.<br />

1-year after disaster in NYC (N=2,368)<br />

Percent<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

Pre-Disaster<br />

Post-Disaster<br />

0<br />

Pysch.<br />

Psychiat.<br />

Other MD<br />

MH Counsel.<br />

Soc. Wrk.<br />

Minister<br />

Self-Help<br />

Boscarino, et al. General Hospital Psychiatry 26: 2004, 346-358.<br />

Any Visits

WTC disaster event exposure<br />

assessment<br />

Rescue Effort<br />

Saw Inperson<br />

Fear of Injury/Death<br />

Relative/Friend Killed<br />

Lost Possessions<br />

Lost Job<br />

8.3%<br />

7.8%<br />

3.2%<br />

33.4%<br />

35.6%<br />

40.7%<br />

JA Boscarino et al. Mental <strong>Health</strong> Service Use 1-Year after the World Trade Center<br />

Disaster: Implications for Medical Care. General Hospital Psychiatry 26: 2004, 346-358.

Exposure to WTC disaster and<br />

mental health visits/medication use – W1<br />

(all comparisons significant at p

Prevalence of PTSD and depression by<br />

Exposure to WTC disaster - wave 1 (N=2,368)<br />

Percent<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

PTDS Past Year<br />

4.9<br />

3.8<br />

Low<br />

Exposure<br />

6.6<br />

4.3<br />

Moderate<br />

Exposure<br />

Depression Past Year<br />

10.9<br />

6.0<br />

High<br />

Exposure<br />

18.4<br />

12.6<br />

(both p

% Increased Drinking by Exposure<br />

to WTC Disaster Events<br />

Increase 2+ Drinks/Day<br />

Increase 2+ Days Drinking<br />

25<br />

20<br />

Increased drinks/day p0.05<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Low<br />

Exposure<br />

Moderate<br />

Exposure<br />

High<br />

Exposure<br />

Very High<br />

Exposure<br />

Boscarino et al. Alcohol use in NY after the terrorist attack. Addictive Behaviors 2006;31:606-621.

Differences in receiving crisis<br />

interventions at work by demographics<br />

Characteristic<br />

Gender<br />

Male<br />

Female<br />

Race<br />

White<br />

African American<br />

Hispanic<br />

Other<br />

(N=180)<br />

Received<br />

Intervention<br />

(p = ns)<br />

37.7<br />

62.3<br />

(p = ns)<br />

45.7<br />

20.1<br />

27.0<br />

7.2<br />

Boscarino, et al. Medical Care, 2006;44:454-462.<br />

(N=1,501)<br />

No<br />

Intervention<br />

46.8<br />

53.2<br />

42.7<br />

26.4<br />

23.9<br />

7.0

Percent<br />

% Received crisis intervention at<br />

work by exposure to WTC disaster<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

10% NYC adults had postdisaster<br />

crisis interventions<br />

- 7% had at worksite<br />

1.5<br />

Low<br />

Exposure<br />

Received Intervention<br />

5.4<br />

Moderate<br />

Exposure<br />

11.6<br />

High<br />

Exposure<br />

(p

Number of crisis sessions<br />

received at work – wave 1 (n=180)<br />

17%<br />

44%<br />

One<br />

Two to<br />

Three<br />

Four or<br />

More<br />

39%<br />

Boscarino, et al.<br />

Medical Care 2006;44:454-462.

Log-odds ratio showing positive effect<br />

of counseling at follow-up – covariate adjusted<br />

0.5<br />

Log odds ratios<br />

0<br />

-0.5<br />

-1<br />

-1.5<br />

-2<br />

-2.5<br />

Binge<br />

Alc Dep<br />

Partial PTSD<br />

Depression<br />

Somatization<br />

Anxiety<br />

Global Impair<br />

One<br />

2 to 3<br />

No sessions = reference category<br />

Boscarino, et al. Medical Care 2006;44:454-462.

Delayed PTSD post-WTCD and Percent experiencing 2+<br />

stressful life events in past 2 years<br />

80%<br />

78% 79%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

44%<br />

54%<br />

39%<br />

58%<br />

Year 1<br />

Year 2<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

14%<br />

18%<br />

10%<br />

Resilient<br />

n=1494<br />

Remitters<br />

n=92<br />

Delayed<br />

n=66<br />

Acute<br />

n=28<br />

Adams, Boscarino. Predictors of PTSD & delayed-PTSD after disaster. J Nervous and Mental Disease 2006;194:485-93.`

Delayed PTSD post-WTCD and percent experiencing<br />

Low self-esteem in past 2 years<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

64%<br />

71%<br />

78%<br />

71%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

47%<br />

54%<br />

Year 1<br />

Year 2<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

Resilient<br />

Remitters<br />

Delayed<br />

Acute<br />

n=1495<br />

n=92<br />

n=66<br />

n=28<br />

Adams, Boscarino. Predictors of PTSD & delayed-PTSD after disaster. J Nervous and Mental Disease 2006;194:485-93.

PTSD and Genetics

Search for Genetics of PTSD

Genetic basis of PTSD<br />

• One-third of PTSD variation due to genetics:<br />

• Serotonin transporter gene (SCL6A4)<br />

• Dopamine transporter & D 2 D 4 receptor genes<br />

• Monamine Oxidase A (MAOA) gene<br />

• Norepinephrine gene<br />

• Neuropeptide Y & Substance P genes<br />

• Neurobiologic factors associated w/ PTSD:<br />

• Mixed lateral handedness<br />

• Lower Intelligence<br />

• ADHD<br />

• NSS

Results of allelic variations for serotonin<br />

transporter gene (SLC6A4) x environmental exposure<br />

(A. Caspi, et al. Science 2003; 301: 386-391)

Current status of PTSD research<br />

• Search for PTSD genes underway<br />

• Advances in PTSD measures being made<br />

• Psychobiology of PTSD emerging<br />

• Impact of PTSD involves other major<br />

psychopathology<br />

• Studies of effectiveness of brief treatments<br />

• Treat PTSD early & prevent disease/death?

Multifactoral PTSD Outcome Model:<br />

Potential Causal Pathways to Disease Outcomes<br />

Heredity & Shared<br />

Environment<br />

Implications<br />

• Multi-level Analyses<br />

• Longitudinal Framework<br />

• Biologic Factors<br />

• Behavioral Analyses<br />

Psych Trauma<br />

Exposure<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Status<br />

Behavior<br />

Biological<br />

Alterations<br />

PTSD