American Magazine, Nov. 2013

The flagship publication of American University. This magazine offers a lively look at what AU was and is, and where it's going. It's a forum where alumni and friends can connect and engage with the university.

The flagship publication of American University. This magazine offers a lively look at what AU was and is, and where it's going. It's a forum where alumni and friends can connect and engage with the university.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

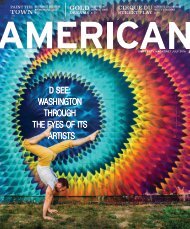

By Lee Fleming<br />

She had artist Claes Oldenburg<br />

as a temporary tenant in her<br />

basement. She turned a derelict<br />

opera house in downtown<br />

D.C. into a mecca for artists,<br />

curators, and collectors from<br />

around the world. And in the<br />

process, she almost single-handedly created a<br />

contemporary art scene in the nation’s capital.<br />

At 91, Alice Denney, the pint-sized powerhouse<br />

whom many call the doyenne of Washington<br />

art, remains a force to be reckoned with.<br />

Distinguished by signature giant sunglasses<br />

and striking headpieces—from a striped<br />

Cat in the Hat–inspired creation by couture<br />

milliner Philip Treacy to a crocheted beer-can<br />

number—Denney is still scouring galleries,<br />

museum exhibitions, performance spaces, art<br />

fairs, and artists’ studios in search of the new<br />

and the provocative.<br />

“I just liked talking to the artists,” she says<br />

about how and why she got into the art world.<br />

“That got me interested in doing things.”<br />

Denney has never been one to hesitate to<br />

engage people or experiences. Even as a child<br />

in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, she would enlist<br />

available talent to her projects. Gene Kelly was<br />

an 18-year-old counselor at the camp near her<br />

family’s summer cabin when Denney, then 12,<br />

saw him dance. “He was good, so I asked if he’d<br />

like to be in one of my shows”—referring to the<br />

productions she would mount with local kids.<br />

“He said yes, and he came to our house and had<br />

a great time, so he kept coming back.”<br />

While a student at Duke, Denney took<br />

art history courses, which she loved. But her<br />

passion really developed when, as a young<br />

bride, she and friends would visit New York<br />

galleries and hang out at the fabled Cedar<br />

Tavern in Greenwich Village, where Willem<br />

de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, and<br />

other abstract expressionist artists held court.<br />

“It was so exciting hearing them talk about<br />

their ideas,” she says. By the time Denney and<br />

her late husband George moved to Washington<br />

in the 1950s, she was hooked on the New<br />

York movements that were transforming<br />

contemporary art.<br />

Denney’s<br />

experiences<br />

with the AU fine<br />

arts faculty<br />

had a major<br />

impact on her<br />

earliest efforts<br />

George had been recruited to work for<br />

then secretary of state Dean Acheson. That<br />

left Denney with time on her hands to explore<br />

the D.C. art scene. “There really was<br />

nothing,” she says. Culture, as it existed in<br />

Washington, consisted of staid museums<br />

whose collections stopped dead at the<br />

postwar period, a few music societies, and<br />

the mainstream Broadway shows that came<br />

through the old National Theatre. “We may<br />

as well have been in a time capsule,”<br />

says Denney.<br />

She set out to change all that. Along the way,<br />

she developed a reputation for her ability to<br />

recognize talent in emerging artists and her<br />

fearlessness to promote the new, the different,<br />

and the challenging. The late Walter Hopps,<br />

founding director of Houston’s Menil<br />

Collection and former curator of twentiethcentury<br />

<strong>American</strong> art at Washington’s National<br />

Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian<br />

<strong>American</strong> Art Museum), and himself no slouch<br />

when it came to discovering new talent, once<br />

called her “the best eye in the business.”<br />

Jack Rasmussen, director of the <strong>American</strong><br />

University Museum at the Katzen Arts<br />

Center, counts Denney among his earliest<br />

art world mentors. “She told me, ‘Look<br />

for artists you don’t understand. If art by<br />

definition is something that didn’t exist<br />

before, then if you immediately get something,<br />

it probably isn’t art.’”<br />

Denney’s experiences with the fine arts<br />

faculty at AU had a major impact on her early<br />

efforts. Their work on exhibit at the Corcoran<br />

Biennial and at Franz Bader Bookstore and<br />

Gallery sparked her interest in what was<br />

happening at the university. In 1955 she signed<br />

up for a life drawing course taught by Ben “Joe”<br />

Summerford. “The course put me in touch<br />

with artists like Alma Thomas [noted African<br />

<strong>American</strong> abstractionist] and especially the AU<br />

faculty, who were really serious and trying new<br />

things,” she says.<br />

It became clear that Washington artists<br />

needed a place devoted to showing their art.<br />

“They wanted a professional gallery. So I said,<br />

why not start one?”<br />

Let’s talk #americanmag 19