Heritage 0308_Bushfire.pdf - Australian Heritage Magazine

Heritage 0308_Bushfire.pdf - Australian Heritage Magazine

Heritage 0308_Bushfire.pdf - Australian Heritage Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

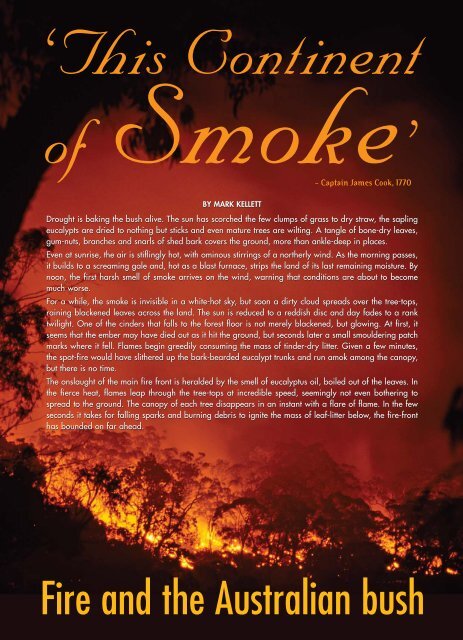

‘This Continent<br />

of Smoke’<br />

- Captain James Cook, 1770<br />

BY MARK KELLETT<br />

Drought is baking the bush alive. The sun has scorched the few clumps of grass to dry straw, the sapling<br />

eucalypts are dried to nothing but sticks and even mature trees are wilting. A tangle of bone-dry leaves,<br />

gum-nuts, branches and snarls of shed bark covers the ground, more than ankle-deep in places.<br />

Even at sunrise, the air is stiflingly hot, with ominous stirrings of a northerly wind. As the morning passes,<br />

it builds to a screaming gale and, hot as a blast furnace, strips the land of its last remaining moisture. By<br />

noon, the first harsh smell of smoke arrives on the wind, warning that conditions are about to become<br />

much worse.<br />

For a while, the smoke is invisible in a white-hot sky, but soon a dirty cloud spreads over the tree-tops,<br />

raining blackened leaves across the land. The sun is reduced to a reddish disc and day fades to a rank<br />

twilight. One of the cinders that falls to the forest floor is not merely blackened, but glowing. At first, it<br />

seems that the ember may have died out as it hit the ground, but seconds later a small smouldering patch<br />

marks where it fell. Flames begin greedily consuming the mass of tinder-dry litter. Given a few minutes,<br />

the spot-fire would have slithered up the bark-bearded eucalypt trunks and run amok among the canopy,<br />

but there is no time.<br />

The onslaught of the main fire front is heralded by the smell of eucalyptus oil, boiled out of the leaves. In<br />

the fierce heat, flames leap through the tree-tops at incredible speed, seemingly not even bothering to<br />

spread to the ground. The canopy of each tree disappears in an instant with a flare of flame. In the few<br />

seconds it takes for falling sparks and burning debris to ignite the mass of leaf-litter below, the fire-front<br />

has bounded on far ahead.<br />

Fire and the <strong>Australian</strong> bush

FOR MANY AUSTRALIANS,<br />

both past and present, this<br />

terrifying scenario is all too<br />

familiar. Like red-back spiders<br />

and tiger snakes, fire is a constant<br />

threat for those who live in the bush.<br />

The intensity of <strong>Australian</strong> bushfire<br />

is a natural consequence of the forest<br />

that fuels it, but fire in the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

landscape has also been greatly<br />

influenced by people and the changes<br />

they have wrought in the<br />

environment.<br />

Many plants of the <strong>Australian</strong> bush<br />

– in particular, those of the dry<br />

sclerophyll forests and woodlands, and<br />

the semi-arid and desert areas – are<br />

adapted to cope with periods<br />

of drought and the nutrientdeficient<br />

soils of our ancient<br />

continent. Their leaves are<br />

toughened and have relatively<br />

small surfaces to prevent<br />

wilting in dry conditions, and<br />

they are retained for as long<br />

as possible to optimise the<br />

plant’s use of scarce nutrients.<br />

To protect them from<br />

browsing animals, the leaves<br />

are often endowed with<br />

various combinations of tough<br />

surfaces, spikes and<br />

unpalatable chemicals.<br />

A consequence of these<br />

adaptations, however, seems<br />

to be an increase in the frequency of<br />

fire. The same adaptations that<br />

protect the leaves against herbivores,<br />

together with the lack of water, act to<br />

greatly slow down the processes of<br />

decay. Hence when the leaves are<br />

finally shed, they build up along with<br />

branches and bark into a deep mass of<br />

dry litter which is a prime fuel. On<br />

top of this, the chemicals used for<br />

defence by some species of sclerophyll<br />

plant – particularly the eucalypts –<br />

are highly flammable.<br />

With large amounts of fuel on the<br />

forest floor and a canopy stocked with<br />

flammable chemicals above, the bush<br />

needs just a single spark in dry<br />

conditions to become an inferno.<br />

Litter like this shed eucalyptus bark is prime fire fuel.<br />

In response, many bush plants have<br />

evolved ways of surviving fire. Many<br />

eucalypts, for example, can survive<br />

burning and regrow lost foliage from<br />

protected buds. In most species, these<br />

buds sprout from the trunk and<br />

branches, giving the trees a somewhat<br />

fluffy look in the few years after fire.<br />

Others, like mallees and snow gums,<br />

have buds that lie beneath the<br />

ground, and new growth shoots from<br />

the base of seemingly dead trees.<br />

Perennial herbs that form the<br />

understorey of the bush survive fire by<br />

avoidance. They grow during the<br />

cooler and wetter seasons, and die<br />

back in the summer, when fires are<br />

most likely. Their dead stems and<br />

leaves will burn, but the living<br />

underground bulb or tuberous<br />

root mass of the plant survives<br />

to grow again next year.<br />

Many wattles are killed by<br />

fire, but they have a strategy<br />

to survive as a species. Their<br />

seeds, shed in vast numbers<br />

from pods, are induced to<br />

germinate by the heat of fire,<br />

and they then enjoy the<br />

additional benefit of a rich<br />

ashy compost to nourish their<br />

growth.<br />

Plants like the grass trees<br />

(Xanthorrhoea) have a method<br />

of dealing with fire that<br />

combines aspects of those used<br />

64 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>

y eucalypts and wattles. Though their<br />

foliage burns readily, their trunk is able to<br />

survive most fires. Afterwards, they not<br />

only regrow their lost leaves but are<br />

stimulated to flower, so that their seeds<br />

will be set in the nutrient-rich ash.<br />

Though many plants of the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

bush have these superb adaptations to<br />

fire, there are indications that fire was<br />

not always so prevalent in the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

landscape.<br />

For much of Australia’s history, native<br />

conifers like bunya pines (Araucaria),<br />

were common in the northern areas,<br />

while the south was dominated by the<br />

southern beech (Nothofagus). Dry<br />

sclerophyll forests, made up of she-oaks<br />

(Casuarina), eucalypts and wattles<br />

(Acacia), appeared as the continent<br />

become cooler and drier, but ancient and<br />

modern habitats were able to exist in<br />

uneasy equilibrium. Roughly 45,000 years<br />

ago, this balance was upset. The dry<br />

sclerophyll bush lost most of its she-oaks<br />

and expanded dramatically, pushing the<br />

southern beech and native conifers into a<br />

few tiny pockets.<br />

Examination of sediment from many<br />

parts of Australia shows that this<br />

coincided with an increase in the<br />

frequency of fire. Fire certainly has the<br />

potential to contribute to such a change,<br />

for, unlike eucalypts and wattles, native<br />

conifers and southern beech are very<br />

vulnerable to fire and some dry<br />

sclerophyll plants like she-oaks and some<br />

banksias can have difficulty regenerating<br />

if repeatedly burnt.<br />

However, several other aspects of the<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> ecology also changed radically<br />

at about this time, any or all of which<br />

could also have contributed to the<br />

reduction in the ancient flora. The<br />

climate became more variable, possibly as<br />

a result of a change in El Niño and La<br />

Niña weather patterns. The giant animals<br />

known as megafauna, many of which<br />

browsed on shrubs and trees, had by this<br />

time become extinct in some parts of<br />

Australia and rare in others. Finally, the<br />

first humans – the Aboriginal people –<br />

had arrived.<br />

By the time Europeans were becoming<br />

aware of Australia, the Aboriginal people<br />

TOP RIGHT: The dry leaves and resin of grass<br />

trees burn readily during fire.<br />

BOTTOM: After being burnt, grass trees sprout<br />

new leaves and eventually flower.<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> 65

had been regularly burning dry<br />

sclerophyll forest for thousands of<br />

years. Though fire was very common,<br />

leading Captain James Cook to<br />

poetically describe Australia as “this<br />

continent of smoke”, it was not<br />

capriciously started by the<br />

Aboriginals. It was part of a system<br />

termed ‘fire-stick farming’, where the<br />

timing, extent and location of burns<br />

were carefully controlled, usually by<br />

tribal elders. In middle to late<br />

summer, a small area that had been<br />

left to grow for between three to five<br />

years was burnt under close<br />

supervision, as John Lort Stokes<br />

observed during the Beagle’s survey of<br />

the <strong>Australian</strong> coast between 1837<br />

and 1843.<br />

On our way we met a party of natives<br />

engaged in burning the bush, which<br />

they do in sections every year. The<br />

dexterity with which they manage so<br />

proverbially dangerous agent as fire is<br />

indeed astonishing. Those to whom<br />

this duty is especially entrusted, and<br />

who guide or stop the running flame,<br />

are armed with large green boughs,<br />

with which, if it moves in the wrong<br />

direction, they beat it out.<br />

It used to be thought that fire-stick<br />

farming was employed principally as a<br />

means of flushing game towards<br />

hunters. Though doubtless fire was<br />

used for this purpose, regularly<br />

burning the bush had other, longerterm<br />

benefits for the Aboriginal<br />

people.<br />

By opening the bush canopy and<br />

returning the nutrients trapped in<br />

leaf litter to the soil, fires encouraged<br />

the growth of plants which<br />

Aboriginal people liked to eat,<br />

particularly the perennial herbs<br />

whose bulbs and tubers formed an<br />

important part of their diet. Burning<br />

also made hunting easier, both by<br />

promoting the grasses that their game<br />

ate and by keeping the forest open,<br />

which gave a hunter a clearer shot<br />

with his spear.<br />

The general effect of Aboriginal<br />

fire-stick farming was to create a<br />

patchwork forest made up of areas at<br />

various stages of recovery from fire.<br />

Leaf litter was never allowed to build<br />

up, so the fires were low enough in<br />

intensity for established trees to<br />

survive, though young saplings were<br />

often killed. As a result of the grazing<br />

provided by the understorey of herbs<br />

and grasses and control through<br />

regular hunting, many animals had<br />

relatively small, but stable,<br />

populations.<br />

Captain Cook said more than he<br />

knew when he compared the<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> bush to “plantations in a<br />

gentleman’s park”, for it was no more<br />

natural than a plantation or an<br />

orchard. Like those European<br />

artificial habitats, if the management<br />

system was removed, the bush would<br />

rapidly fall to weeds. This is exactly<br />

what happened in uncleared areas<br />

when Aboriginal people were<br />

displaced and no longer exerted their<br />

influence on the forests.<br />

As the seedlings of trees and bushes<br />

were left to reach maturity, the open<br />

forest gradually closed, and<br />

understorey plants were deprived of<br />

light and drowned under a sea of leaflitter.<br />

In some places she-oaks were<br />

Continued on page 68<br />

66 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>

ABOVE: Black Thursday, February 6th 1851, William Strutt, 1825–1915, painting: oil on canvas; 106.5 x 343.0 cm. State Library of Victoria,<br />

Image number H28049.<br />

BLACK THURSDAY<br />

The summer of 1851 had been hot and long, and the country had the appearance of a vast hay-field, blanched by the scorching sun, and<br />

inflammable as tinder. One of the main fires originated at Bullock Creek, near the present Bendigo Diggings, where a scrubby district had<br />

been fired by a shepherd with a view to clear it; the north wind when it rose fanned the kindling flames, and bore them on till they were far<br />

beyond all control. Other fires in no ways connected with that which commenced at Bullock Creek broke out in different directions, and swept<br />

as rapidly onwards.<br />

So frightful was the celerity with which the fire travelled, that the swiftest horse could barely gallop away from it. Mile after mile was traversed<br />

by the flames, and was left a smoking wilderness, with only smouldering ashes to mark the site of once peaceful homesteads. On the great<br />

plains many flocks of sheep fell a prey to the devouring element, and drays that had been left standing, some perhaps with their helpless teams<br />

still yoked, were totally consumed, and only the iron work left remaining.<br />

The mighty sheets of fire hurried on, gaining force and fierceness as they advanced, darting out in long tongues over the parched flats, and<br />

licking up the grass; as they reached the forests the flames curled round the ancient stems, and creeping to the top of the trees flew on from<br />

one tree-top to another, while through the tangled undergrowth below roared a sea of fire. The flakes of burning matter were hurled aloft by<br />

the wind, and borne across creeks and gullies, from one hill-top to another, and lodged on the house-roofs or hay-stacks of the settlers, finding<br />

fresh fuel everywhere.<br />

The heat of the air, which seemed all alight with sparks, became intense, nor was it cooled by the clouds of smoke and cinders that gradually<br />

obscured the brightness of day, and converted it into a lurid and awful twilight. It was not surprising that many anxious persons, who saw<br />

themselves surrounded with fire and smoke on all sides, and knew not whither to fly, gave themselves up for lost, and waited in trembling for<br />

the sound of the last trump.<br />

Extract from Glimpses of Life in Victoria, by ‘A Resident’, John Hunter Kerr, first published in 1876.<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> 67

Bush fire in Australia, Samuel Calvert, 1828–1913, print: col. wood engraving; 32.8 x 45.3 cm. National Library of Australia, nla.pic-an8927792.<br />

able to re-establish themselves, and at<br />

least hold their own against the<br />

eucalypts and wattles. Major Thomas<br />

Mitchell described the change in the<br />

area around Sydney as early as 1838:<br />

Kangaroos are no longer seen there;<br />

the grass is choked by underwood;<br />

neither are there natives to burn the<br />

grass... ...the omission of the annual<br />

periodical burning by natives, of the<br />

grass and young saplings, has already<br />

produced in the open forests nearest<br />

to Sydney, thick forests of young<br />

trees, where, formerly, a man might<br />

gallop without impediment, and see<br />

whole miles before him.<br />

This new, neglected bush was prime<br />

fire territory, and bushfire rapidly<br />

became a frightening part of the<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> experience. Lightning and<br />

desperate attempts by Aboriginal<br />

people to retain the fire-stick system<br />

or to burn out the invaders were<br />

frequent causes of fire, but so was<br />

European ‘burning off’, used to clear<br />

farmland, improve grazing and reveal<br />

hidden mineral deposits, along with<br />

carelessness with fire and arson.<br />

Outlying farms, where Europeans<br />

coexisted with bush to some degree,<br />

were particularly vulnerable, as blazes<br />

from the unmanaged bush outside<br />

could easily spread into farmland in<br />

periods of drought, as David Collins<br />

noted in his Journal in 1792.<br />

At Parramatta and Toongabbe also<br />

the heat was extreme; the country<br />

there too was everywhere in flames.<br />

Mr Arndell was a great sufferer by it.<br />

The fire had spread to his farm, but<br />

by the efforts of his own people and<br />

neighbouring settlers it was got under,<br />

and its progress supposed to be<br />

eventually checked, when an unlucky<br />

spark from a tree, which had been on<br />

fire to the topmost branch, flying on<br />

the thatch of the hut where his<br />

people lived, it blazed out; the hut<br />

with all the outbuildings, and thirty<br />

bushels of wheat just got into a stack,<br />

were in a few minutes destroyed.<br />

In 1838, the assigned convict,<br />

Joseph Mason, noted that farmers had<br />

learned to take precautions to protect<br />

their precious wheat crops: “Most of<br />

the settlers do not sow the headlands<br />

of their fields but leave a border all<br />

around which they plough up & suffer<br />

to remain bare so that the fire may<br />

not run in upon the wheat”.<br />

Fires of this type were a severe<br />

threat to the new <strong>Australian</strong>s and<br />

their property but with a concerted<br />

effort by neighbouring farmers they<br />

were usually contained. However,<br />

after periods of prolonged drought, a<br />

particularly hot day with high winds<br />

could nurture a hellish inferno.<br />

One of the most disastrous of these<br />

firestorms broke out on the 6th of<br />

February, 1851; later dubbed Black<br />

Thursday. Numerous independent<br />

fires, probably started by humans,<br />

raged out of control in many places,<br />

killing ten people and burning up to a<br />

quarter of what would soon after<br />

become the colony of Victoria.<br />

Black Thursday was the first of a<br />

series of firestorms that burned their<br />

way into <strong>Australian</strong> history. Notable<br />

among them are Red Tuesday<br />

(1/2/1898) in which much of<br />

Gippsland was incinerated, killing 12<br />

people and destroying more than<br />

2,000 buildings; Black Sunday<br />

68 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>

(14/2/1926) where fires again hit<br />

Gippsland and southern NSW, and<br />

swept through the Dandenong Ranges<br />

in Victoria, taking 31 lives; the truly<br />

appalling Black Friday fires<br />

(13/1/1939), that burnt a swathe<br />

through Victoria and New South<br />

Wales, killing 71 people; Black<br />

Tuesday (7/2/1967) in which the<br />

whole of Tasmania seemed to catch<br />

fire, taking 62 lives and doing<br />

significant damage to Hobart; the Ash<br />

Wednesday fires (16/2/1983) that<br />

burnt vast areas of Victoria and South<br />

Australia, killing 75 people; and more<br />

recently, the fires of January 18, 2003<br />

that ripped through Canberra and<br />

surrounding areas, killing four people<br />

and destroying more than 500 homes,<br />

and the fires of January 11, 2005 on<br />

the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia<br />

in which nine lives were lost.<br />

The early great fires were the trigger<br />

for the development of Australia’s fire<br />

control organisations. Fire brigades<br />

were established, initially as locally<br />

based voluntary groups, and today<br />

these operate as state authorities<br />

backed by armies of volunteers. Firefighting<br />

is their central role, but<br />

strategies of land and fire<br />

management, including the use of fire<br />

to control fire, are equally important.<br />

Incorporating fire into the firecontrol<br />

system has proved to be a<br />

complex issue. One approach favoured<br />

legislation and fire-fighting forces to<br />

totally suppress fire in the bush.<br />

Though this strategy certainly reduced<br />

the incidence of local fires, the buildup<br />

of litter would eventually fuel<br />

particularly destructive firestorms.<br />

Another system advocated regular<br />

burning as the Aboriginal ‘fire-stick<br />

farmers’ had done. Though this does<br />

serve to reduce the intensity of fires,<br />

the results are unsightly and a<br />

controlled fire can easily become an<br />

uncontrolled one. Further, the process<br />

is damaging when applied to firesensitive<br />

or degraded habitats.<br />

<strong>Bushfire</strong> is inevitable in Australia,<br />

but the question is: are big fires<br />

inevitable or can we learn how to<br />

control them in different types of<br />

landscape? Today, the management of<br />

bushfire in our various landscapes –<br />

from southern forests to the savannas<br />

of the north – is the subject of a great<br />

deal of research. The <strong>Bushfire</strong><br />

Cooperative Research Centre,<br />

established in 2003, has brought<br />

together scientists, fire authorities,<br />

land-management groups and<br />

FIRE IN WET SCLEROPHYLL FORESTS<br />

As its name suggests, wet sclerophyll forest grows in wetter and often cooler areas than its dry counterpart. Though eucalypts dominate this forest,<br />

the milder conditions promote an understorey of many kinds of ferns.<br />

These forests grow in a climate that usually does not encourage fire, and there is no indication that Aboriginal people used their system of firestick<br />

farming in them. However, after periods of prolonged drought, wet sclerophyll will burn readily. Several of the truly devastating fires in<br />

Australia’s history, notably the Red Tuesday and Black Friday fires, have involved bushfire entering wet sclerophyll forest.<br />

Due to the relative rarity of fires, wet sclerophyll plants have different responses to being burnt. The mountain ash, the tallest of the eucalypts, is<br />

killed by fire. However, its gum-nuts are opened by the flames, and take root in the soil almost immediately afterwards. For this reason, most<br />

stands of mountain ash are all of the same size, all having taken root after the same fire.<br />

Though rare and destructive, firestorms are an important factor in shaping the character of wet sclerophyll forests, which, in the absence of fire,<br />

would be displaced by fire-intolerant temperate rainforest.<br />

The wet sclerophyll eucalypt pictured above has been struck by lightning. Unless the land is in drought, the fire has little chance of spreading far.<br />

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong> 69

Though the bush appears devastated after fire<br />

(above), many plant species can recover quite<br />

quickly (right).<br />

emergency services from around the<br />

country to improve our understanding<br />

of fire and to develop environmentally<br />

sustainable fire and land-management<br />

strategies.<br />

One thing is clear: fire has played a<br />

major role in creating the <strong>Australian</strong><br />

landscape for a very long time and, if<br />

the predictions about climate change<br />

are correct, bushfires are likely to<br />

become more frequent and more<br />

intense. Without doubt, improving<br />

our knowledge of the relationship<br />

between fire and our environment will<br />

be the key to learning how to live<br />

with the danger of bushfire.<br />

The Author<br />

Dr Mark Kellett is a biologist and<br />

freelance science writer.<br />

Further Reading<br />

Australia Burning: Fire Ecology, Policy and<br />

Management Issues edited by Geoffrey<br />

Cary, David Lindenmayer and Stephen<br />

Dovers, CSIRO Publishing, 2003.<br />

The Future Eaters by Tim Flannery, Reed<br />

Books, 1994.<br />

Burning Bush: A Fire History of Australia by<br />

Stephen J. Pyne, Allen & Unwin,<br />

1992. ◆<br />

70 <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Heritage</strong>