2001 Newsletter - The Peregrine Fund

2001 Newsletter - The Peregrine Fund

2001 Newsletter - The Peregrine Fund

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

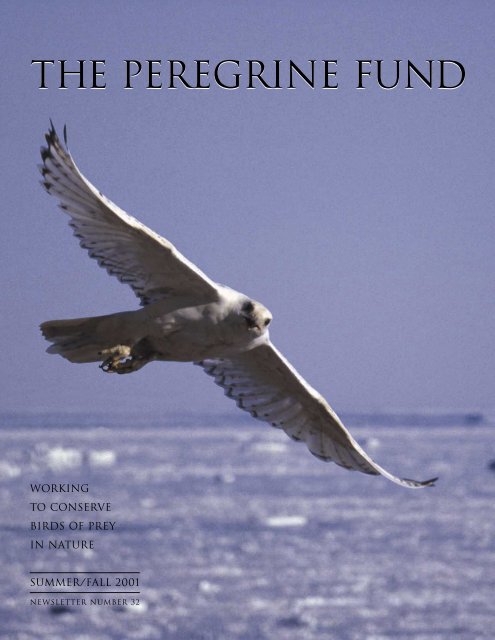

THE PEREGRINE FUND<br />

working<br />

to conserve<br />

birds of prey<br />

in nature<br />

summer/fall <strong>2001</strong><br />

newsletter number 32

Imagine a world<br />

without…<br />

…the next generation.<br />

Photo by Bill Burnham<br />

One Hundred Percent of All Donations Go Directly to Programs!<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> is working to conserve birds of prey around the world. All of our programs<br />

are dependent upon contributions. Help preserve future generations of birds of prey. Make a<br />

tax-deductible contribution to <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> today. To learn more, visit our web site.<br />

www.peregrinefund.org

Business Office (208)362-3716<br />

Fax (208)362-2376<br />

Interpretive Center (208)362-8687<br />

tpf@peregrinefund.org<br />

http://www.peregrinefund.org<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> will soon be constructing a new<br />

collections building at our location in Boise, Idaho.<br />

With the addition of this new building our mailing<br />

address is changing. Our new mailing address is<br />

5668 West Flying Hawk Lane, Boise, Idaho 83709.<br />

THE PEREGRINE FUND STAFF<br />

United States<br />

Linda Behrman<br />

Roy Britton<br />

Bill Burnham<br />

Kurt K. Burnham<br />

Pat Burnham<br />

Jack Cafferty<br />

Jeff Cilek<br />

MaryAnn Edson<br />

Nancy Freutel<br />

Bill Heinrich<br />

Grainger Hunt<br />

J. Peter Jenny<br />

Russ Jones<br />

Lloyd Kiff<br />

Paul Malone<br />

Kim Middleton<br />

Angel Montoya<br />

Amel Mustic<br />

Brian Mutch<br />

Trish Nixon<br />

Shaun Olmstead<br />

Nedim Omerbegovic<br />

Sophie Osborn<br />

Chris Parish<br />

Carol Pettersen<br />

Dalibor Pongs<br />

Rob Rose<br />

Cal Sandfort<br />

Randy Stevens<br />

Russell Thorstrom<br />

Randy Townsend<br />

Rick Watson<br />

Dave Whitacre<br />

Chris Woods<br />

Archivist<br />

S. Kent Carnie<br />

OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS<br />

D. James Nelson<br />

Chairman of the Board<br />

President, Nelson<br />

Construction Company<br />

Paxson H. Offield<br />

Vice Chairman of the<br />

Board<br />

President and CEO,<br />

Santa Catalina Island<br />

Company<br />

William A. Burnham,<br />

Ph.D.<br />

President<br />

J. Peter Jenny<br />

Vice President<br />

Jeffrey R. Cilek<br />

Vice President<br />

Karen J. Hixon<br />

Treasurer<br />

Conservationist<br />

Ronald C. Yanke<br />

Secretary<br />

President, Yanke<br />

Machine Shop, Inc.<br />

International<br />

Aristide Andrianarimisa<br />

Francisco Barrios<br />

Adrien Batou<br />

Be Berthin<br />

Noel Augustin Bonhomme<br />

Eloi (Lala) Fanameha<br />

Martin Gilbert<br />

Noel Guerra<br />

Ron Hartley<br />

Kathia Herrera<br />

Mia Jessen<br />

Herman A. Jordan<br />

Loukman Kalavaha<br />

Eugéne Ladoany<br />

Magaly Linares<br />

Jose Lopez<br />

Jules Mampiandra<br />

Moise<br />

Angel Muela<br />

Charles Rabearivelo (Vola)<br />

Berthine Rafarasoa<br />

Norbert Rajaonarivelo<br />

Jeannette Rajesy<br />

Gérard Rakotondravao<br />

Yves Rakotonirina<br />

Norbert Rajaonarivelo<br />

Gaston Raoelison<br />

Christophe<br />

Razafimahatratra<br />

Lova Jacquot Razanakoto<br />

Lily-Arison Rene<br />

de Roland<br />

Leonardo Salas<br />

Simon Thomsett<br />

Gilbert Tohaky<br />

Ursula Valdez<br />

Jose Vargas<br />

Munir Virani<br />

Zarasoa<br />

Tom J. Cade, Ph.D.<br />

Founding Chairman<br />

Professor Emeritus of<br />

Ornithology, Cornell<br />

University<br />

Roy E. Disney<br />

Chairman of the Board,<br />

Emeritus<br />

Vice Chairman, <strong>The</strong><br />

Walt Disney Company<br />

Chairman of the Board,<br />

Shamrock Holdings, Inc.<br />

Henry M. Paulson, Jr.<br />

Chairman of the Board,<br />

Emeritus<br />

Chairman and Chief<br />

Executive Officer, <strong>The</strong><br />

Goldman Sachs Group,<br />

Inc.<br />

Julie A. Wrigley<br />

Chairman of the Board,<br />

Emeritus<br />

Chairman and CEO,<br />

Wrigley Investments LLC<br />

THE PEREGRINE FUND<br />

NEWSLETTER NO. 32 • SUMMER/FALL <strong>2001</strong><br />

Letters<br />

Our colleagues around the world respond to the tragedy of September 11 . . . . . . . . .2<br />

Aplomado Falcon Recovery<br />

Captive-bred falcons get some extra protection from predators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3<br />

California Condor Restoration<br />

Released California Condors officially “come of age” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4<br />

Greenland Project<br />

Satellite tracking reveals the range of the incredible Gyrfalcon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6<br />

Harpy Eagles<br />

New facility in Panama provides tropical environment for captive breeding . . . . . . .8<br />

Madagascar<br />

Local people assume protection of natural resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9<br />

Cape Verde Kite<br />

Capturing one of these rare raptors puts our biologists to the test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10<br />

Zimbabwe Falconers Club<br />

How a falconers club assists in shaping national conservation strategies . . . . . . . . .13<br />

Notes from the Field<br />

From Peru to Pakistan, our researchers share their triumphs and worries . . . . . . . .15<br />

Development<br />

Our future is in your hands! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23<br />

Education<br />

Up-close encounters with birds of prey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24<br />

Lee M. Bass<br />

President, Lee M. Bass,<br />

Inc.<br />

Robert B. Berry<br />

Trustee, Wolf Creek<br />

Charitable Trust,<br />

Falcon Breeder, and<br />

Conservationist<br />

Harry L. Bettis<br />

Rancher<br />

P. Dee Boersma,<br />

Ph.D.<br />

Professor, University of<br />

Washington<br />

Frank M. Bond<br />

Attorney at Law and<br />

Rancher<br />

Robert S. Comstock<br />

President and CEO,<br />

Robert Comstock<br />

Company<br />

Derek J. Craighead<br />

Ecologist<br />

© <strong>2001</strong> • Edited by Bill Burnham • Design © <strong>2001</strong> by Amy Siedenstrang<br />

BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF THE PEREGRINE FUND<br />

DIRECTORS<br />

Scott A. Crozier<br />

Senior Vice President<br />

and General Counsel<br />

PETsMART, INC<br />

T. Halter<br />

Cunningham<br />

Business Executive/<br />

Investor<br />

Patricia A. Disney<br />

Vice Chairman,<br />

Shamrock Holdings,<br />

Inc.<br />

James H. Enderson,<br />

Ph.D.<br />

Professor of Biology<br />

<strong>The</strong> Colorado College<br />

Caroline A. Forgason<br />

Partner,<br />

Groves/Alexander<br />

Michael R. Gleason<br />

Investor, Culmen<br />

Group, L.P.<br />

Z. Wayne Griffin, Jr.<br />

Developer, G&N<br />

Management, Inc.<br />

Jacobo Lacs<br />

International<br />

Businessman and<br />

Conservationist<br />

Patricia B. Manigault<br />

Conservationist and<br />

Rancher<br />

Velma V. Morrison<br />

President, Harry W.<br />

Morrison Foundation<br />

Ruth O. Mutch<br />

Investor<br />

Morlan W. Nelson<br />

Naturalist,<br />

Hydrologist, and<br />

Cinematographer<br />

Ian Newton,<br />

D.Phil., D.Sc.<br />

Senior<br />

Ornithologist (Ret.)<br />

Natural Environment<br />

Research Council<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Thomas T. Nicholson<br />

Rancher and<br />

Landowner<br />

Lucia L. Severinghaus,<br />

Ph.D.<br />

Research Fellow<br />

Institute of Zoology,<br />

Academia Sinica<br />

Taiwan<br />

R. Beauregard Turner<br />

Fish and Wildlife<br />

Manager, Turner<br />

Enterprises<br />

William E. Wade, Jr.<br />

President (Ret.),<br />

Atlantic Richfield<br />

Company<br />

James D. Weaver<br />

Past President, North<br />

American Falconers’<br />

Association,<br />

and Raptor Biologist<br />

P.A.B. Widener, Jr.<br />

Rancher and Investor<br />

1

Nature Makes the Whole World Kin<br />

– Shakespeare<br />

During the week of 11<br />

September <strong>2001</strong> we were<br />

holding our annual planning<br />

meeting. <strong>The</strong>re were staff<br />

members and cooperators from<br />

many countries, cultures, and religions<br />

gathered at the World<br />

Center for Birds of Prey to present<br />

programmatic results from the<br />

past year and to make plans for<br />

what we hope to achieve in the<br />

following five years. <strong>The</strong> first<br />

news of the terrorist attack came<br />

via the Philippines when the<br />

President of the Philippine Eagle<br />

Foundation called. For the next<br />

two hours we sat and watched in<br />

horror and disbelief as the events<br />

were reported and displayed on a<br />

television in our meeting room.<br />

As we sat there the sadness and<br />

rage were no less or more for<br />

those of us from the United States<br />

than those from Europe, Africa,<br />

Asia, or Latin America. <strong>The</strong> attack<br />

was not just on and about the<br />

United States, but directed at the<br />

world’s humanity and the very<br />

core of civilization and human<br />

freedoms.<br />

Over the next few days we<br />

received a stream of messages,<br />

some of which are shared here.<br />

Receiving these messages it was<br />

increasingly obvious that<br />

although “we work to conserve<br />

birds of prey in nature,” the effect<br />

is far greater than just on raptors,<br />

or even nature conservation. We<br />

have found a common interest<br />

and bond on which relationships<br />

and understanding are established<br />

and nurtured, helping bridge cultures,<br />

nations, and peoples of the<br />

world. As we learned in uniting<br />

the vast diversity of people and<br />

organizations to restore the<br />

<strong>Peregrine</strong> Falcon, it is seldom possible<br />

to agree on everything, but if<br />

we can find something in<br />

common on which to agree, many<br />

of the other problems can eventually<br />

be resolved through understanding<br />

and finally trust.<br />

“Allow me to share my outrage at<br />

the cowardly assault on your<br />

country. At the same time, my<br />

family joins me in prayer for the<br />

thousands of lives that have been<br />

lost and affected by these terrorists.<br />

I wish I could be of some<br />

help in any way. Please let me<br />

know.” Philippines<br />

“We are shocked to learn about<br />

the recent tragedy in the US. We<br />

share with you all the grief and<br />

sorrow. We strongly condemn<br />

and resent this act of terrorism.<br />

We take it as crime not against<br />

the American government or<br />

American people, but against<br />

humanity. We wish that we<br />

could have been with you at this<br />

sad and evil event.” Pakistan<br />

“We are deeply shocked with the<br />

terrorism act in the US. We join<br />

all of Malagasy people and<br />

nation to condemn such act. We<br />

hope the US government will<br />

2<br />

We have found a common interest<br />

… helping bridge cultures, nations,<br />

and peoples of the world.<br />

find quickly those responsible for<br />

this act and punish them severely<br />

to let the liberty, freedom, and<br />

peace settle forever.”<br />

Madagascar<br />

“From me personally and from<br />

my country and the whole of<br />

Europe I send you my deepest<br />

sympathy. I do not know what to<br />

say. We all support you.”<br />

Denmark<br />

“On rare occasion, even fanatical<br />

raptor conservationists can be<br />

diverted from their cause. This is<br />

one such occasion. No words can<br />

express the level of revulsion that<br />

these unjustifiable acts have generated<br />

around the world. Our<br />

thoughts are with our American<br />

friends and colleagues at this<br />

tragic time. Let us hope that this<br />

despicable attack only serves to<br />

unite every civilized individual of<br />

all nations to eradicate this evil<br />

from our world. This is a shockingly<br />

terrible day in the history of<br />

mankind.” United Kingdom<br />

“I express my deepest condolences<br />

of my heart to all Americans who<br />

have lost their relatives in today’s<br />

terrorist attack. I know there is<br />

little comfort in words, but I do<br />

want to express how deeply we<br />

all feel for you. We are shocked,<br />

horrified, and saddened. God<br />

bless all Americans and us.”<br />

Mongolia<br />

“Please accept my (and all or our<br />

staff’s) sympathies to the attacks<br />

of terrorists!”<br />

Hungary<br />

“I think all of us in Europe are<br />

deeply shocked and saddened by<br />

the terrible events of yesterday. I<br />

personally feel deeply for all of<br />

you who are friends across the<br />

Atlantic. I grieve for the thousands<br />

so callously slain. It is a<br />

joint tragedy and shame to whole<br />

humankind that soil our planet.”<br />

Estonia

Aplomado Falcon Recovery:<br />

Dealing with Other Predators<br />

This year our biologists<br />

were able to locate 33<br />

by J. Peter Jenny pairs of Aplomado<br />

Falcons in South Texas, and although<br />

some of these pairs were immature, 22<br />

(66%) attempted to breed. Perhaps<br />

most encouraging was that the number<br />

of young to successfully fledge from<br />

these nests more than tripled from last<br />

year. Only eight young were able to<br />

fledge from nests last year as a result of<br />

predation by raccoons, coyotes, and<br />

Great Horned Owls. This season breeding<br />

pairs successfully fledged at least<br />

29 young.<br />

We experimented with several proactive<br />

management techniques in an<br />

effort to reduce predation from ground<br />

predators at nests. When our biologists<br />

located an active nest they circled it<br />

with a single strand of portable electrical<br />

fence. Next, small sticks were<br />

treated with “Renardine,” which was<br />

developed in Great Britain to protect<br />

ground nesting birds from foxes. A few<br />

of the sticks were placed directly under<br />

the nest, and others were placed in a<br />

30-yard circle around the nest.<br />

Although some losses still occurred, we<br />

found that predation by raccoons and<br />

coyotes at nests receiving these management<br />

techniques was significantly<br />

reduced.<br />

We are also developing artificial<br />

nesting structures designed to make it<br />

more difficult for predators to gain<br />

access to the falcon’s eggs or their<br />

young. <strong>The</strong> Great Horned Owl remains<br />

the most difficult predator for us to<br />

manage, and in some areas of south<br />

Texas the species may ultimately limit<br />

the recovery of the Aplomado Falcon.<br />

<strong>The</strong> interaction of species in nature<br />

is one of the many challenges encountered<br />

in restoration biology. Although<br />

the effects of these interactions are<br />

often extremely frustrating, they are, in<br />

the end, one of the aspects of working<br />

with nature that makes our work so<br />

very interesting.<br />

From top: Adult Aplomado Falcon above<br />

nest.<br />

Photo © W.S. Clark<br />

Photo by Amy Nicholas<br />

<strong>The</strong> interaction<br />

of species in<br />

nature is one<br />

of the many<br />

challenges<br />

encountered in<br />

restoration<br />

biology.<br />

Photo by Brian Mutch<br />

Aplomado Falcon eggs in White-tailed<br />

Hawk nest. Aplomados and other falcons do<br />

not build their own nests, and may use<br />

nests constructed by other birds.<br />

Biologists place electric wire around base of<br />

nest tree.<br />

3

Major Milestone Achieved for<br />

25 March <strong>2001</strong><br />

Photo by Chris Parish<br />

Adult Condor<br />

soars at the edge<br />

of the Grand<br />

Canyon.<br />

…the object<br />

he was pushing<br />

around<br />

was large and<br />

smooth and<br />

elliptical and<br />

looked exactly<br />

like – an<br />

EGG!!<br />

For those of us who have worked<br />

with the condors and those of you<br />

by Sophie Osborn who have watched them at the<br />

Vermilion Cliffs and Grand Canyon or read of their<br />

trials and tribulations in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong>’s home<br />

page field notes (www.peregrinefund.org), the<br />

thrilling discovery on 25 March was deeply moving.<br />

It will forever mark an unforgettable milestone in<br />

our efforts to restore the condor.<br />

Sunday, 25 March <strong>2001</strong>, started out in the same<br />

way as almost every other day in March, with the<br />

various crew members headed out early to the<br />

release site and the Colorado River corridor to track<br />

and monitor Arizona’s 25 free-flying condors. I<br />

headed out to the river to observe our “trio,” male<br />

Condor 123 and female Condors 119 and 127, and<br />

to monitor a newly released juvenile, Condor 198,<br />

who had left the Vermilion Cliffs a mere six days<br />

after his release (more on him later!). Perched on<br />

the cliff edge, I watched Condor 119 fly over to the<br />

cave the trio had been investigating on and off for<br />

several weeks, and disappear inside at 1020 hours.<br />

Condors 123 and 127 were content to perch on a<br />

nearby ledge. Much to my surprise, an hour and a<br />

quarter later, Condor 198 appeared, flying down a<br />

side canyon and heading straight for the cave and<br />

the lounging adults. After several days perched<br />

alone on cliffs overlooking the town of Marble<br />

Canyon, he had finally found his way to the river<br />

and found some companions!<br />

Dodging the pesky <strong>Peregrine</strong> Falcon that was<br />

relentlessly pursuing him, Condor 198 landed by<br />

the cave next to Condors 123 and 127. <strong>The</strong> adults,<br />

however, did not appear to appreciate their space<br />

being invaded by an intruder. Chaos erupted!<br />

Condor 119 emerged from her cave and, surprisingly,<br />

was promptly attacked by her mate, Condor<br />

123, while Condor 127 began attacking Condor<br />

198. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> wisely retreated! As Condor 119<br />

dropped off the ledge, she turned her attentions to<br />

pursuing Condor 198. Condors 123 and 127<br />

quickly joined in the chase. A few minutes later<br />

Condor 198 circled and landed by the cave and the<br />

three adults settled nearby. Perhaps the adults’<br />

aggression would have abated had Condor 198 not<br />

decided to fly again and land even closer to the cave<br />

entrance. No sooner had he landed than the adults<br />

attacked again. Finally, Condor 123 escorted the<br />

young bird out of the territory.<br />

Upon his return, Condor 123 flew to the cave<br />

and walked part way in. Nine minutes later, he was<br />

in full view in the cave entrance and was pushing<br />

something around with his bill. Such behavior was<br />

not unusual, since these three adults have been<br />

engaging in frequent nest grooming behavior where<br />

they push pebbles and debris around the “nest”<br />

cave and ledge with their bills. But as Condor 123<br />

stepped back, I saw that the object he was pushing<br />

around was large and smooth and elliptical and<br />

looked exactly like—an EGG!! A condor egg!! I<br />

don’t know if I breathed. Time seemed suspended.<br />

Frantically I tried to focus my scope for a closer<br />

look, but it was already zoomed in as far as it would<br />

go! I stared and stared. Could this in fact be the<br />

first condor egg laid in the wild since 1986?!? Or<br />

was it just a large, oval rock? Frantically, I searched<br />

my memory. Had I noticed a smooth white rock in<br />

the cave entrance earlier? Surely, I would have<br />

noted it if I had. I struggled to contain my excitement.<br />

As an emotional person, caught up in my<br />

affection for the condors and the ever-unfolding<br />

drama of the efforts to recover them, I wanted to<br />

jump and shout, to rush off to tell the world what<br />

an amazing thing these incredible birds had done!<br />

But the biologist in me won out. I needed to be<br />

absolutely 100% sure of what I was seeing. I could<br />

not afford to be wrong about this. Motionless, I<br />

continued staring through the scope. Calmly, I<br />

described what I was seeing in my field notes. For<br />

almost an hour I stared at the beautifully smooth<br />

4

California Condor Restoration<br />

object, pausing only to call Chris<br />

Parish, our project manager, on<br />

the cell phone to let him know<br />

that I might be looking at a<br />

condor egg!<br />

While I watched, Condor 119<br />

left the area and Condor 123 went<br />

into the cave for several minutes,<br />

then perched by the entrance. At<br />

1236 hours, Condor 127 walked<br />

up to the cave entrance and<br />

stopped by the possible egg.<br />

Reaching down, she placed her bill<br />

inside its hollowed-out back end.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n I knew. I was elated ... and,<br />

for a brief moment, crushed. It was<br />

indeed an egg! No rock could be<br />

so smooth, elliptical, white, eggshell<br />

thin, and hollow to boot!<br />

But it was broken. Still, none of us<br />

had realistically expected the birds<br />

to successfully hatch an egg this<br />

year. Condors do not usually<br />

manage to hatch an egg on their<br />

first attempt. Typically, the egg gets<br />

broken or is infertile. <strong>The</strong> fact that<br />

this egg was broken in no way<br />

diminishes the fact that these birds<br />

who had been released as two-year<br />

olds in 1997 and faced extraordinary<br />

odds over the ensuing years,<br />

including almost being killed by<br />

lead poisoning in the summer of<br />

2000, had found themselves a nest<br />

cave and laid their first egg!!! I<br />

felt overwhelmed by the enormity<br />

of the moment. Although dozens<br />

of people had contributed infinitely<br />

more to the release effort<br />

than I had, I happened to be the<br />

lucky person in the right spot at<br />

the right time to see the first egg<br />

laid by free-flying condors in 15<br />

years! It gave me a surge of hope<br />

that despite the infinite obstacles<br />

these magnificent birds face, they<br />

will succeed.<br />

Photo by Chris Parish<br />

5

Female Gyrfalcon at her<br />

eyrie after being tracked<br />

by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong><br />

for nearly a year. Note<br />

satellite-monitored<br />

transmitter antenna<br />

extending from her<br />

back.<br />

Gyrfalcon<br />

Tracking Provides<br />

Valuable Information<br />

Photo by Alberto Palleroni<br />

Gyrfalcon<br />

with satellite<br />

transmitter.<br />

Photo by Alberto Palleroni<br />

Gyrfalcons are the largest of all<br />

species of falcons. <strong>The</strong>y breed<br />

by Kurt K. Burnham in the arctic regions of the<br />

world, feeding on ptarmigan and many other kinds<br />

of birds as well as Arctic Hare and small mammals.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir prey varies from location to location, and<br />

even time of year, as they take advantage of changes<br />

in abundance and seasonal availability. Plumage<br />

also varies, but not seasonally, as they molt only<br />

once annually. Gyrfalcons nesting in the northern<br />

arctic frequently have light-colored plumage and<br />

some are near white, while those in the more southern<br />

arctic are mostly gray in color. <strong>The</strong>ir plumage<br />

color may offer them an advantage when hunting<br />

prey as more snow and ice occur in the northern<br />

arctic than in the southern.<br />

To breed and survive in the severe arctic conditions,<br />

Gyrfalcons have special adaptations beyond<br />

plumage color. <strong>The</strong>ir legs are covered with feathers<br />

and they have very dense plumage with thick down,<br />

all to hold in body heat. During long arctic storms<br />

they may have to go for days without feeding, and<br />

conservation of energy is important. In the early<br />

spring, and particularly during incubation, temperatures<br />

may be well below zero Fahrenheit.<br />

6

Four nearly fledged<br />

young produced by<br />

tracked Gyrfalcon.<br />

Photo by Alberto Palleroni<br />

Rock-climbing:<br />

one of the many<br />

challenges of<br />

studying the<br />

Gyrfalcon.<br />

Gyrfalcons have held great fascination for some<br />

biologists and for centuries have been highly<br />

regarded by falconers; however, very little is actually<br />

known about them in parts of their range, and in<br />

particular in Greenland. We are trying to answer<br />

many questions about this species in Greenland,<br />

including their seasonal movements. Using transmitters<br />

monitored by satellite (PTTs) is providing<br />

detailed information.<br />

On 13 October 2000, we placed a PTT on a<br />

female Gyrfalcon at a fall trapping station near the<br />

Arctic Circle on the west coast of Greenland. <strong>The</strong><br />

data gained from this transmitter allowed us to track<br />

her for the entire winter and into the following<br />

spring and summer. After we attached the PTT to<br />

her, she proceeded about 480 miles (800 km) down<br />

the west coast of Greenland and spent the winter<br />

months in southern Greenland. In mid-March she<br />

began to migrate back up the west coast and settled<br />

into an area northwest of Kangerlussuaq, most likely<br />

her breeding territory. In June, using the best locations<br />

we had received from her PTT, we were able to<br />

find her, and shortly afterwards her nest. Her nest<br />

contained four 30+ day old young and was tucked<br />

into a cliff above a high mountain lake surrounded<br />

by snowcapped peaks. <strong>The</strong> valley contained willowchoked<br />

gullies, excellent ptarmigan habitat that<br />

was most likely one of the reasons she chose to<br />

breed at this location. After several attempts at capturing<br />

her we finally were successful and replaced<br />

her current PTT with a new unit that will last until<br />

the summer of 2002.<br />

With the information gained from this Gyrfalcon<br />

and additional falcons carrying satellite-monitored<br />

transmitters, we are gaining important new information<br />

for the conservation of Gyrfalcons. This<br />

research will continue for several more years with<br />

between 15 and 25 Gyrfalcons being tracked annually.<br />

To obtain more information on our work in<br />

Greenland and Gyrfalcons, please visit our home<br />

page at www.peregrinefund.org.<br />

Photo by Bill Burnham<br />

Her nest<br />

contained four<br />

30+ day old<br />

young and was<br />

tucked into a<br />

cliff above a<br />

high mountain<br />

lake surrounded<br />

by snowcapped<br />

peaks.<br />

7

Harpy Eagle.<br />

Photo by Alberto Palleroni<br />

Harpy Eagles Arrive at Neotropical<br />

Raptor Center, Panama<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are now five pairs of Harpy<br />

Eagles at the Neotropical Raptor<br />

Center, located a short distance<br />

from Panama City within the former<br />

U. S. Fort Clayton, renamed the City of<br />

Knowledge. This new entity was created<br />

by an Act of the Panamanian<br />

Congress to establish a center of excellence<br />

for intellectual, business, and<br />

environmental activities in Panama.<br />

<strong>Fund</strong>o Peregrino—Panama (<strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong>—Panama) has offices,<br />

staff housing, and the Neotropical<br />

Raptor Center there. We were one of<br />

the first organizations to become a resident.<br />

With the completion of six large<br />

steel and chain-link breeding chambers,<br />

Harpy Eagles from the World<br />

Center for Birds of Prey in Idaho were<br />

moved to the Neotropical Raptor<br />

Center in October <strong>2001</strong>. Each chamber<br />

was constructed within the forest and<br />

visually separated from other chambers<br />

and any human activity, creating as<br />

natural an environment as possible for<br />

captive breeding. Although Harpy<br />

Eagles were successfully bred and many<br />

8<br />

young raised at our World Center’s<br />

Gerald D. and Kathryn Swim Herrick<br />

Tropical Raptor Building in Idaho, we<br />

could not achieve the desired rate of<br />

reproduction nor plumage and condition<br />

of the eagles. It was simply impossible<br />

for us to duplicate a tropical environment<br />

indoors for such large eagles.<br />

Our Panamanian cooperators were<br />

excited by the arrival of the eagles. Of<br />

special interest was the repatriation of<br />

Ancon, a male Harpy Eagle formally<br />

loaned to <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> in 1991<br />

by Panama. Ancon hatched in the<br />

wilds of Panama in 1985 and was illegally<br />

captured. He was rescued by a<br />

premier Panamanian environmental<br />

organization, “ANCON,” thus his<br />

name. With that organization’s assistance<br />

the eagle was transferred to <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong>. Soon after his arrival<br />

at the World Center for Birds of Prey<br />

he was paired with a young female and<br />

over the years they produced eight<br />

young Harpy Eagles, including three<br />

previously returned and released in<br />

Panama.<br />

International Conference<br />

on Neotropical Raptors<br />

and Harpy Eagle<br />

Symposium<br />

❖<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong><br />

Fondo Peregrino – Panama<br />

❖<br />

Panama City, Panama<br />

24 - 27 October 2002<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> and Fondo<br />

Peregrino – Panama invite you<br />

to join scientists, conservationists,<br />

resource managers, falconers,<br />

representatives of zoos, government<br />

and non-governmental organizations,<br />

and other persons and institutions<br />

with an interest in research<br />

and/or conservation of birds of<br />

prey in Latin America and the<br />

Caribbean to participate in a meeting<br />

to share knowledge, interests,<br />

and concerns and help develop a<br />

network of practitioners in the fields<br />

of raptor conservation, research,<br />

captive-breeding, and falconry.<br />

For further information, contact:<br />

Neotropical Raptor Conference<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong><br />

5668 West Flying Hawk Lane<br />

Boise, Idaho 83709<br />

United States of America<br />

Tel: 208-362-3717<br />

Fax: 208-362-2376<br />

E-mail: tpf@peregrinefund.org<br />

Details and registration forms are<br />

also available on <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong><br />

<strong>Fund</strong>’s web site at:<br />

www.peregrinefund.org/<br />

nrconference.html

Natural Resource Management<br />

Transferred to Local Population<br />

Madagascar is<br />

the fourth<br />

by Russell Thorstrom largest island<br />

in the world and is inhabited by some<br />

of the most unusual and unique plants<br />

and animals in the world. <strong>The</strong> are 24<br />

species of birds of prey in Madagascar<br />

of which 14 occur only on the island.<br />

Due to its uniqueness, number of<br />

endemic animals and plants, and loss<br />

of primary vegetation, Madagascar has<br />

become one of the primary hotspots in<br />

the world for conservation. <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong>’s interest<br />

in Madagascar began Madagascar<br />

many years ago with Fish Eagle.<br />

research and conservation<br />

of the critically<br />

endangered endemic<br />

Madagascar Fish Eagle<br />

and Madagascar Serpent-<br />

Eagle. In Madagascar,<br />

both wetlands and<br />

forested habitat continue<br />

to be lost at an<br />

alarming rate and conservation<br />

remains critical.<br />

Wetlands are extremely threatened<br />

due to the dependency of the Malagasy<br />

people on them for cultivating rice,<br />

their staple food.<br />

We began research work on the<br />

endangered Madagascar Fish Eagle in<br />

the wetlands of central western<br />

Madagascar in 1991. Our work has<br />

been focused at Lakes Soamalipo,<br />

Befotaka, and Ankerika on what we<br />

estimate to be 10% of the entire breeding<br />

fish eagle population. <strong>The</strong>se three<br />

lakes also support an abundant fisheries<br />

resource. In the early 1990s there<br />

was an increasing number of seasonal<br />

migrant fishermen coming to these<br />

lakes to catch fish to sell. This increased<br />

pressure conflicted with the needs of<br />

the local people and their laws, and<br />

eventually reduced fish stocks.<br />

In 1993, we proposed the idea of a<br />

community-based conservation project<br />

to protect the wetlands and natural<br />

resources shared by the local people<br />

and fish eagles. By 1996, the government<br />

of Madagascar created and<br />

encouraged empowerment of local<br />

communities to control and manage<br />

their natural resources (Law Project<br />

No. 17/96). We then began working<br />

with the local people around the three<br />

lakes to help achieve local control. In<br />

1997, with our support and aid, the<br />

people around Lakes Soamalipo and<br />

Befotaka formed a chartered association<br />

for managing<br />

their resources of the<br />

lakes and surrounding<br />

forest. Two years later<br />

the people on Lake<br />

Ankerika did likewise.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong><br />

was challenged with<br />

convincing the local<br />

people of the need to<br />

group together, how to<br />

improve their existing<br />

traditional laws and<br />

sanctions, the importance<br />

of managing their resources sustainably,<br />

and thinking in terms of their<br />

future. We have been helping these two<br />

associations to reach their objective of<br />

controlling their natural resources.<br />

Finally, in 2000 these associations<br />

requested the transfer of the resource<br />

management from the government of<br />

Madagascar to them. After five long<br />

years it became a reality on 29<br />

September <strong>2001</strong>.<br />

For the next three years, during a<br />

probationary period, the local organizations<br />

will be required to demonstrate<br />

adequate care and management practices<br />

over their resources. Upon the<br />

completion of the probationary period,<br />

the review process will be extended by<br />

the government of Madagascar to every<br />

10 years. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> will continue<br />

to be a resource for the sake of<br />

the eagles.<br />

Photo by Russell Thorstrom<br />

Photo by Russell Thorstrom<br />

Natural<br />

resources:<br />

canoe<br />

made<br />

from a<br />

nearby<br />

tree and<br />

fish from<br />

the wetlands.<br />

Presentation ceremony transfers natural<br />

resource management to local people.<br />

Photo by Lily-Arison Rene de Roland<br />

9

Cape Verde Kites<br />

Boavista<br />

A<br />

F<br />

Cape Verde<br />

Kites are<br />

known to<br />

survive only<br />

in these<br />

islands off<br />

the coast of<br />

Africa.<br />

R<br />

I<br />

C A<br />

by Rick Watson<br />

Endangered species conservation<br />

always presents challenges.<br />

Some are easier to<br />

deal with than others; some are predictable<br />

bureaucratic challenges that just take time<br />

and endless patience; others are of “cuttingedge<br />

science” in nature; and yet others relate<br />

to unexpected behavior of the animals themselves.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Cape Verde Kite project has had<br />

its fair share of all these!<br />

Scientifically, the Cape Verde Kite presents<br />

an interesting dilemma to conservation<br />

biologists. It was only recently proposed as a<br />

distinct species, Milvus fasciicauda, despite<br />

the fact that its nearest relative, the<br />

European Red Kite, Milvus milvus, was found<br />

over 1,800 miles (3,000 km) away. Of this<br />

substantial distance, at least 400 miles<br />

(645 km) is over the Atlantic Ocean.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Cape Verde Kite is geographically<br />

isolated from its nearest relatives, but<br />

since when, and how they got there, we<br />

do not know. Like other island species<br />

(e.g., Darwin’s finches in the<br />

Galapagos) once isolated, these kites<br />

probably followed their own evolutionary<br />

path as the species adapted to local<br />

conditions. New information collected<br />

in the mid-1990s on the behavior and<br />

morphology of the Cape Verde Kite is<br />

consistent with this theory. This new<br />

evidence, combined with conservation<br />

biologists’ revised understanding of what defines a<br />

“species” for the purpose of conservation (based on<br />

acceptance of populations with a different evolutionary<br />

history being the basic currency for conservation),<br />

we now recognize the Cape Verde Kite as<br />

unique and different from its European relative, and<br />

worthy of conservation in its own right. <strong>The</strong> tragedy<br />

of this new understanding is that many species may<br />

have already gone extinct because they were not previously<br />

recognized as worthy of the time, effort, and<br />

substantial cost of conservation. This may have been<br />

the fate of the Cape Verde Kite, except <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong><br />

<strong>Fund</strong> went to work “just in time”—we hope!<br />

When we began this project over a year ago, there<br />

was a possibility the species may have become extinct<br />

One call produced<br />

the hint of a kite,<br />

so Sabine spent<br />

her last dollars on<br />

a flight to the<br />

island of Boavista.<br />

European Red<br />

Kite, closest<br />

relative of the<br />

Cape Verde<br />

Kite.<br />

in the previous few months. Only two<br />

widely separated individuals had been seen<br />

in the species “stronghold” in 1999 on the<br />

island of Santa Antão, and two were<br />

reported from neighboring São Vicente island in<br />

2000. In October 2000 we recruited Sabine Hille, a<br />

German biologist studying kestrels on the Cape Verde<br />

islands and then finishing her PhD at the Konrad-<br />

Lorenz Institute in Vienna, to mount a search for the<br />

Cape Verde Kite to establish whether or not the<br />

species survived. If found, we proposed to capture the<br />

last remaining birds for captive breeding. This, we<br />

felt, was another Mauritius Kestrel, a species so decimated<br />

by human activities that only captive breeding<br />

could save it from extinction. In captivity, the chances<br />

of the adult birds surviving are much higher than in<br />

the wild. We can control and optimize their diet for<br />

breeding and we can manage the breeding to increase<br />

Photo by Sabine Hille<br />

10

Found<br />

the number of eggs laid and hatched, increasing survivorship<br />

of nestlings. Put together, this kind of<br />

intensive hands-on management can greatly improve<br />

the chances of species survival when only a few individuals<br />

remain.<br />

Sabine immediately went to work organizing a<br />

team of volunteers to help her scale the rugged<br />

mountains of Santa Antão and São Vicente islands<br />

in search of kites. <strong>The</strong> Cape Verde islands are literally<br />

“desert islands,” not the Robinson Crusoe-like<br />

(or “Cast Away-like”!) “deserted islands” rich in<br />

tropical vegetation. <strong>The</strong>y are volcanic, dry islands<br />

that rise from the sea to over 3,000 feet (900 m) to<br />

where scarce moisture allows vegetation to hold on<br />

to a precarious life, or they surface to only a few<br />

hundred feet where only drought-hardy plants<br />

manage to dot the barren landscape.<br />

Survey work began in May this year and by late<br />

June the team of 10 sadly concluded the Cape Verde<br />

Kite was now extinct. <strong>The</strong>re were none to be found<br />

in its “last stronghold” on Santa Antão or neighboring<br />

São Vicente Islands. Five days before her scheduled<br />

departure, Sabine called around to friends and<br />

biologists working on other islands “just in case”<br />

someone had seen something like a kite on another<br />

island where they had not been recorded in<br />

decades. One call produced the hint of a kite, so<br />

Sabine spent her last dollars on a flight to the island<br />

of Boavista. Two days later I received an excited<br />

phone call, “<strong>The</strong>y’re here! Four kites, Cape Verde<br />

Kites,” yelled Sabine’s elated voice over a crackling<br />

phone line from a mid-Atlantic desert island. Her<br />

last few days were spent in intensive study of the<br />

birds’ hunting behavior, daily routine, and habitat<br />

preferences. Armed with this information she<br />

returned to Austria to plan for the capture and<br />

translocation of the birds, while her local friends<br />

began “training” the birds to come to a predictable<br />

food station.<br />

A month later, our field team flew in to Cape<br />

Verde, arriving in Sal Island’s international airport in<br />

the early morning hours. Sabine was joined by longtime<br />

friend of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong> Jim Willmarth and<br />

our Project Manager from Kenya, Simon Thomsett,<br />

both experts in the capture and translocation of birds<br />

of prey. But that is a story I will let Jim tell.<br />

Kite Capture Depends<br />

on Patience, Timing,<br />

and Technology<br />

by Jim Willmarth<br />

After meeting Sabine Hille, I was shepherded<br />

through customs and experienced the unusually<br />

complicated process of flying from one<br />

island to another in Cape Verde. Sabine speaks Crioulo, a mixture<br />

of Portuguese and various West African languages, as well as<br />

the official language of Portuguese. She has worked in Cape<br />

Verde for years so everywhere we went we were greeted by smiling<br />

acquaintances. Arriving in Boavista Island after a night of<br />

limited sleep on the airport floor at Sal Island, we hitched a ride<br />

and stowed our gear with friends. We then<br />

went directly to the site where Sabine’s friends<br />

I had the<br />

uncanny<br />

feeling they<br />

were waiting<br />

for us.<br />

had been leaving food for the kites every five<br />

days. To my amazement, as soon as we turned<br />

off the cobblestone main road onto the dirt<br />

track leading to the feeding spot, there they<br />

were. All four kites were sitting together on the<br />

phone lines about 100 yards from us. I had the<br />

uncanny feeling they were waiting for us.<br />

As soon as we left food at the feeding site<br />

and backed off a few hundred yards, the kites<br />

flew in to inspect the food from a cautious distance.<br />

Ravens came first and began to take a<br />

few morsels and immediately the kites all came, chased them off,<br />

and began to carry off small bits of food.<br />

As the days passed it became clear that these four kites had<br />

two ravens that they were associated with on a daily basis. If the<br />

ravens did not go to a source of food first, the kites would not<br />

approach it. Often we watched as the kites found a new meal<br />

and waited for the ravens to come and do a security check. If the<br />

ravens found the offered meal suspicious, they would jump up<br />

and down and cry loudly, making such a fuss that the kites<br />

would fly off.<br />

About this time we caught up with Simon Thomsett, the third<br />

member of our party. We knew Simon was on his way but we<br />

were not sure of the exact day or time of his arrival. We had all<br />

been communicating by e-mail but as Simon explained to us, he<br />

lives miles outside of Nairobi, Kenya, at a place with no phone<br />

or electricity. For him to get a message involved the reception of<br />

the e-mail in Nairobi that was copied onto a floppy disc and<br />

(continued on page 12)<br />

11

12<br />

Kite Capture (continued from page 11)<br />

“placed in the end of a cleft stick and<br />

given to a runner who proceeded on<br />

foot to Simon’s house in the traditional<br />

manner of local mail delivery.”<br />

Simon then put the floppy in his<br />

portable computer to read the message.<br />

He said this whole procedure<br />

“took a bit of the convenience out of<br />

e-mail communication” for him!<br />

Drawing on Simon’s experience of<br />

capturing Black Kites in Africa, we<br />

decided to make a blind so we could<br />

be closer to the birds when we caught<br />

them and to aid our observations. At<br />

mid-day when the birds went off to<br />

soar they were often gone for hours.<br />

One day, when I thought the kites<br />

were out for the afternoon, I took a<br />

small shovel and started to make a<br />

place where we could hide. I scraped a<br />

shallow depression in the ground and<br />

started to pile some large rocks around<br />

the perimeter. I noticed the shadow of<br />

a bird move by me. Looking up, I saw<br />

two of the kites only about 40 yards<br />

above. <strong>The</strong>y were watching with great<br />

interest. I walked away feeling foolish.<br />

That evening all four of the kites came<br />

and perched near the aborted hiding<br />

place. <strong>The</strong> ravens came, and upon<br />

seeing the depression and out of place<br />

rocks, they jumped up and down and<br />

cursed the place so loudly that the<br />

kites flew away without even inspecting<br />

the nearby food we had left for<br />

them.<br />

We discussed what we had learned<br />

so far and between us tried to come up<br />

with a solution for catching these<br />

birds. If we could get them all at once<br />

to feed within a few feet of each other,<br />

we would have a chance of capturing<br />

them all with a bow net. A bow net is<br />

a circular net with a ridged frame that<br />

can be placed flat on the ground and<br />

pulled over whatever is within its<br />

perimeter. We soon found we could get<br />

the kites to feed together, but only<br />

once every four or five days.<br />

We set up the bow net and tested it<br />

several times in a place hidden from<br />

the kites’ usual haunts. Each time it<br />

took almost four hours to set up so<br />

that is was hidden from the critical<br />

eyes of the ravens by carefully sprinkling<br />

it with a fine layer of sand. Once<br />

satisfied that the trap worked perfectly,<br />

we set it up one final time, and even<br />

brushed our tracks from the sand as<br />

we retreated 300 yards to our observation<br />

spot. It was days later before the<br />

Cape Verde Kite habitat<br />

on Boavista Island.<br />

ravens, and then the kites, found the<br />

bait. <strong>The</strong> ravens came in first. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

walked around and around the carcass,<br />

calling softly to each other. After about<br />

10 minutes they moved in very close<br />

and began tentatively pecking at it.<br />

Finally, they started to eat. Our careful<br />

preparations had succeeded in deceiving<br />

even the smart ravens!<br />

<strong>The</strong>n the kites arrived, all at once.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y sat about 50 yards away and<br />

watched suspiciously. <strong>The</strong>n they began<br />

to walk in, slowly at first, stopping and<br />

going, waiting for the ones behind to<br />

catch up. As they got closer, they<br />

seemed more excited; their pace quickened<br />

until they began to run, stopping<br />

only for a second or two in their rush.<br />

Finally, one ran straight in with wings<br />

slightly spread in a threatening posture.<br />

Reluctantly, the ravens flew off a<br />

short distance. Now, suddenly, all the<br />

kites were on the carcass. <strong>The</strong>y looked<br />

around and began to feed.<br />

After weeks of patient learning<br />

through observation and trial and<br />

error, we had all four kites together<br />

and within the perimeter of our trap.<br />

Success seemed to be at hand! We<br />

looked at each other with wide eyes.<br />

Anticipating the sprint to the net to<br />

retrieve the captured kites, we grabbed<br />

the transmitter that triggers the trap<br />

and pushed the release lever.<br />

Nothing happened. We passed the<br />

transmitter from hand to hand, pushing<br />

more and more vigorously on the<br />

lever. A good number of technical<br />

expressions were uttered in several different<br />

languages. But it did not help.<br />

Simon even crept in closer to the trap<br />

to see if perhaps reducing the distance<br />

to the receiver on the trap would help.<br />

But to no avail.<br />

Later, as we inspected the failed<br />

trap, we realized that over the days of<br />

patient waiting, sand had gradually<br />

trickled into the trap’s mechanism and<br />

packed tightly around the bow so that<br />

it was effectively jammed tight in the<br />

ground. We tried a variety of solutions,<br />

but with very limited materials available<br />

to work with, none were reliable<br />

Photo by Jim Willmarth

enough to work consistently. We<br />

tried other methods like various<br />

noose traps and others, but by now<br />

the kites had a new and abundant<br />

source of food—locusts that grew<br />

larger by the day. <strong>The</strong>y were maturing<br />

at about five to six inches in<br />

length and had started to breed,<br />

which made them very easy prey.<br />

<strong>The</strong> kites would<br />

catch them two<br />

at a time by<br />

I noticed the<br />

shadow of a bird<br />

move by me.<br />

Looking up, I<br />

saw two of the<br />

kites only about<br />

40 yards above.<br />

simply sailing<br />

over the acacia<br />

trees and plucking<br />

them off the<br />

top branches<br />

like ripe fruit<br />

until they were<br />

full. <strong>The</strong> kites<br />

lost interest in<br />

other food completely<br />

and<br />

stopped coming<br />

to our suspicious<br />

offerings.<br />

We have<br />

hopes of returning<br />

with traps<br />

built specifically<br />

for the difficult conditions on the<br />

islands. <strong>The</strong> locusts should be gone<br />

by then and the birds should be<br />

more interested in the food we<br />

offer them.<br />

Cape Verde is a very unique<br />

country culturally, geographically,<br />

and biologically. I feel honored to<br />

have taken away this small experience<br />

of it. <strong>The</strong> kites are not the only<br />

endangered endemic on this special<br />

group of islands, but I try not to<br />

think of that. It is worrisome<br />

enough when I think of the four<br />

birds on Boavista Island preening in<br />

the morning sun, soaring over their<br />

high rocky ridge, inspecting every<br />

new thing they come across with<br />

curiosity, completely unaware of<br />

how small their tribe has become. I<br />

worry about them and hope that we<br />

will meet again.<br />

Raptor Conservation and Research in Zimbabwe<br />

Falconers<br />

Lead the Way<br />

<strong>The</strong> stimulating part of<br />

heading up the<br />

by Ron Hartley Zimbabwe Falconers<br />

Club (ZFC) is the variety of work<br />

required. With some 66 species of<br />

diurnal raptors and 12 of owls, it is<br />

vital that we prioritize our efforts.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is just one full-time professional<br />

ornithologist in the country, Peter<br />

Mundy, who represents the<br />

Department of National Parks and<br />

Wild Life Management. Fortunately he<br />

has always been forward looking and<br />

part of his responsibilities has been to<br />

facilitate the conservation policies of<br />

non-governmental organizations like<br />

the ZFC. Having worked closely<br />

together for nearly 20 years, we have<br />

structured a policy which focuses on<br />

the biology of the birds, their conservation<br />

needs, and developing public<br />

awareness through a two-pronged educational<br />

program. This policy is also<br />

formally recognized by way of the government<br />

policy toward falconry. Peter<br />

Mundy looks to me and the ZFC program<br />

for key input on the national<br />

strategy for raptor biology and conservation.<br />

Our approach has been supported<br />

and refined by our association<br />

with <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong> <strong>Fund</strong>, which goes<br />

back even further to the late 1970s.<br />

Getting the right people involved is<br />

always the key to a successful operation.<br />

Falconers are hands-on operators<br />

and they are passionate about their<br />

sport and the raptors and prey that<br />

they use. Our program is based on this<br />

passion. Falconers are encouraged to<br />

make use of the wild resource. In<br />

return they are expected to contribute<br />

to the research program by sharing<br />

information on the raptors they<br />

Young Teita<br />

Falcons at<br />

the eyrie.<br />

encounter. Many contribute as volunteers<br />

to the research program and they<br />

include doctors, veterinary surgeons,<br />

farmers, hunters, businessmen, and<br />

tradesmen. Access to such a wide range<br />

of skills has proved most helpful in the<br />

program. My job is to help design and<br />

direct the projects, and to encourage<br />

participation from the volunteers. I<br />

also lead several of the key projects<br />

and get involved in all of the fieldwork<br />

and much of the writing up.<br />

Operating from an idyllic base in<br />

the bushveld at Falcon College in rural<br />

Matabeleland, I have also run the high<br />

school’s falconry club and natural history<br />

unit for nearly 20 years. Students<br />

range from 14 to 18 years of age, and<br />

several graduates now form an important<br />

part of the national research program.<br />

<strong>The</strong> college is surrounded by an<br />

extensive area of wild lands, including<br />

the eastern edge of the famed Matobo<br />

Photo by Ron Hartley<br />

(continued on page 14)<br />

13

Zimbabwe Falconers (continued from page 13)<br />

Photo by Ron Hartley<br />

…students learn<br />

first-hand the habits<br />

of breeding birds,<br />

sometimes climbing<br />

to nests, banding<br />

chicks, and collecting<br />

prey remains.<br />

Hills which hosts one of the richest<br />

arrays of birds of prey in Africa. Species<br />

studied in detail include Crowned,<br />

Martial, African Hawk, Tawny, and<br />

Wahlberg’s Eagles, Black, Ovambo, and<br />

Little Sparrowhawks, and Gabar<br />

Goshawk. Students have been involved<br />

in long-term studies of raptor communities<br />

in this area. Some students also<br />

accompany me on expeditions into<br />

study areas at Batoka Gorge, Chizarira,<br />

Chirisa, Siabuwa, Save Valley, and<br />

David Maritz, a former student at Falcon<br />

College, searches for raptors at Batoka<br />

Gorge.<br />

Bubiana Conservancies, and<br />

Malilangwe. <strong>The</strong>se are all wonderful<br />

wilderness areas with abundant<br />

wildlife, including big game such as<br />

elephants. In the field the students<br />

learn first-hand the habits of breeding<br />

birds, sometimes climbing to nests,<br />

banding chicks, and collecting prey<br />

remains. Some students have done<br />

research projects, which I have helped<br />

stimulate, plan, and supervise. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

projects are also published and the<br />

unit has an enviable publication<br />

record.<br />

As one of our unique attributes is<br />

the hands-on approach, an important<br />

focus has been on the biology of littleknown<br />

species such as Teita Falcons<br />

and African <strong>Peregrine</strong> Falcons, Ayres’<br />

Eagle, and Bat Hawk. We have produced<br />

some useful new information<br />

on all of these species. I have been fortunate<br />

to handle all of these species<br />

and study them also in the wild.<br />

Watching a pair of Teita Falcons tending<br />

young at the nest is most exciting,<br />

not the least because nests are invariably<br />

located in pristine wilderness<br />

areas. Feeling the tree shake as an adult<br />

Martial Eagle alights near the hide and<br />

then drops onto the nest, its baleful<br />

yellow eyes gazing suspiciously, while I<br />

hardly breathe as I will it to settle is<br />

another golden moment. Spotting a<br />

dark nondescript raptor wrench off a<br />

stick and then follow the raptor to find<br />

that it is the elusive and enigmatic Bat<br />

Hawk busy building its nest is equally<br />

captivating. Being able to share such<br />

experiences with like-minded colleagues<br />

is both fun and inspirational.<br />

Not all of our activities involve<br />

such appealing and ground-breaking<br />

biological work. Human impacts are a<br />

constant factor, requiring basic and<br />

sometimes innovative approaches. <strong>The</strong><br />

growing environmental catastrophe<br />

from the widespread and chaotic land<br />

invasions in Zimbabwe, with attendant<br />

deforestation and poaching, threaten<br />

one of the country’s most valuable<br />

assets—its wild land. When Peter<br />

Mundy, Warren Goodwin, and I spent<br />

a weekend at Wabai Hill on Debshan<br />

Ranch early this year we observed over<br />

50 newly built huts below the feature,<br />

an important bird area. Wabai Hill<br />

hosts the northern-most colony of the<br />

Cape Vulture in an area with a rich<br />

variety of other raptors and wildlife. It<br />

was an appropriate venue for our<br />

meeting to contribute to a new threatened<br />

and endangered species list for<br />

Zimbabwe, as our deliberations were<br />

made right on the hard edge of human<br />

pressure. As we cooked dinner in the<br />

bush, we heard a dozen rifle shots in<br />

this erstwhile pristine and protected<br />

area. <strong>The</strong> following day some of the<br />

invaders boasted how they had shot<br />

(illegally) some antelope on the open<br />

plains. We have some daunting challenges<br />

and times ahead.<br />

14

Notes<br />

theField Field<br />

from<br />

Isidor’s Eagle.<br />

Isidor’s Eagles:<br />

Owners of the<br />

Cloud Forest<br />

© Heinz Plenge<br />

It was about 11 years ago when I<br />

saw an Isidor’s Eagle for the first<br />

by Ursula Valdez time. I was crossing the cloud forest<br />

on my way to Amazonian lowlands in Peru. From<br />

a comfortable tourist truck that was giving me a<br />

ride, I could see a fantastic scene. A few meters<br />

from the road there was a mossy tree emerging<br />

from the steep slope and on the top of it there<br />

was a nest with an Isidor’s Eagle and a nestling. I<br />

remember jumping from the truck and staying<br />

while the tourists were heading to a lodge not far<br />

down the road. I stayed there for three hours just<br />

watching the eagles, and I was fascinated with the<br />

(continued on page 16)<br />

15

...we went through a mysterious<br />

A treacherous one-lane mountain<br />

road provides access to the study<br />

area on alternating days.<br />

16<br />

<strong>The</strong> author<br />

builds a<br />

trap.<br />

Photo by Ursula Valdez<br />

Photo by Ursula Valdez<br />

Isidor’s Eagle (continued from page 15)<br />

experience. By that time I was a newly graduated<br />

biologist looking for a direction for my career and<br />

my interest in birds, and especially raptors, was<br />

starting to grow. Sadly, years later I found out that<br />

the eagles were not nesting there anymore. A man<br />

had cut down the tree and since then there was not<br />

evidence of any nesting activity around. During the<br />

next years, however, I had the chance to pass by that<br />

road several times and some of those I still was<br />

lucky to see an Isidor’s Eagle flying along or across<br />

the valley.<br />

By July of 2000, I was hired by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong><br />

<strong>Fund</strong> as a research biologist and I was assigned to<br />

find breeding pairs of Isidor’s Eagles in South<br />

America. After a talk with Rick Watson where I told<br />

him about my sightings in Peru, we decided to<br />

search for the eagles on the cloud forest of the<br />

Cosñipata Valley. As a Peruvian biologist I considered<br />

this a great opportunity to conduct research in<br />

my own country and with raptors that have became<br />

my passion. But I was also excited about going in<br />

search of those enigmatic eagles that years ago fascinated<br />

me and that inhabit the pristine cloud forest<br />

of the southeastern Andean slopes of Peru.<br />

After some paperwork and lots of bureaucracy in<br />

Lima (capital of Peru), I departed to Cuzco, a small<br />

city high in the Andes, which became our contact<br />

with civilization and source of supplies. In mid-July,<br />

after getting food supplies and all we might need<br />

for the following weeks, my assistant, Cynthia King,<br />

and I left Cuzco towards our field site. A dirt road<br />

that joins Cuzco and the Pilcopata Valley took us to<br />

the cloud forest inside of Manu Biosphere Reserve,<br />

the largest and most famous protected area in Peru.<br />

Since the very first field trip, each journey has<br />

been an adventure—breakdowns, flat tires, landslides<br />

and waiting, sometimes days, for huge earthmovers<br />

to clear them, a truck jammed against a cliff<br />

after a misjudged corner, gruesome accidents at the<br />

bottom of the precipice, and more. <strong>The</strong> mountain<br />

road itself shows one of the most peculiar (and<br />

scary) transit systems. <strong>The</strong> road is so narrow and

and magic cloud forest...<br />

with deep precipices that traffic going down to the<br />

lowlands is allowed only three days a week<br />

(Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays), while traffic<br />

going up goes on the rest of the days. On Sundays<br />

when there is not much traffic, vehicles are allowed<br />

to go in both directions—at one’s own risk. Of<br />

course, more than once we found a truck coming in<br />

our opposite direction. I swear, every time we had<br />

checked carefully which day to depart.<br />

In many places along the road we saw crosses<br />

with flowers and some inscriptions marking the<br />

location of accidents and deaths, as a reminder of<br />

how careful you need to be when driving this road.<br />

However, every trip was a fantastic journey going<br />

across the high Andes, contemplating the high and<br />

vast mountains and going through passes to the eastern<br />

slopes that go down to the Amazonian rainforest.<br />

On the highest location of the road<br />

we stopped the vehicle to look at the<br />

fantastic scenery. A green carpet-like<br />

vegetation covered the slopes below<br />

and then far in the horizon we could<br />

see the Amazonian plain.<br />

When we arrived in our study area,<br />

Cynthia and I explored for several<br />

days, walking up and down many<br />

hours along the road. We camped in<br />

wet forests where mornings and nights<br />

were in fact wet and cold. <strong>The</strong>n we<br />

went through a mysterious and magic<br />

cloud forest, in which we walked<br />

under the rain or through dense fog.<br />

But we did not complain. We also had<br />

magnificent sunny and blue-sky days.<br />

During the walks, I stopped every birdwatcher<br />

we found along the road (not many) and<br />

asked if they had seen the eagle. Several times I just<br />

had a sympathetic smile for an answer as most of<br />

them consider the Isidor’s Eagle one of the hardest<br />

species to see. But finally, by mid-August our efforts<br />

were rewarded with the sighting of our first Isidor`s<br />

Eagle high in the sky. Despite our exhaustion we<br />

jumped and celebrated with hugs and dances. For a<br />

couple of days we were able to see the eagle around<br />

...we saw the adult pair<br />

displaying to each other,<br />

grappling talons in midair<br />

and cartwheeling<br />

from the sky toward the<br />

forest canopy<br />

the same area. On the same field trip, we found<br />

another Isidor’s Eagle flying in a higher elevation<br />

locality. We were so excited. Our first goal was<br />

achieved: we confirmed that Isidor’s eagles were<br />

living in our study area. <strong>The</strong> next step was to find<br />

more individuals and nesting sites.<br />

For the next three months my colleague, Sophie<br />

Osborn, gathered information on more individuals<br />

of Isidor’s Eagle and their behavior, and the areas<br />

they frequently visited. In January <strong>2001</strong>, during the<br />

visit of Rick Watson to our study area, we decided to<br />

put all of our efforts into finding a nest of Isidor’s<br />

Eagles and in trapping an individual so we could<br />

radio track it. More challenges, but we took them<br />

again with my new and determined crew (Bryan<br />

Evans, Jose Campoy, and Daniel Huáman as my<br />

field assistants).<br />

During the next five months we<br />

had one of the most fascinating experiences<br />

watching these eagles and<br />

observing their behavior. We will<br />

hardly forget the day we witnessed,<br />

not far from us, a young individual<br />

flying with its parents. Or when we<br />

saw the adult pair displaying to each<br />

other, grappling talons in mid-air and<br />

cartwheeling from the sky toward the<br />

forest canopy, and minutes later,<br />

mating. I observed in awe as an adult<br />

Isidor’s Eagle captured a woolly<br />

monkey. Unfortunately, we haven’t<br />

found a nest yet, but we found certain<br />

evidences of nesting activity. Our trapping<br />

attempts were unsuccessful as<br />

well. However, so far we have gathered<br />

information on the behavior and important<br />

aspects of the biology of the Isidor’s Eagle.<br />

No matter how much longer we want to keep<br />

searching for eagles’ nests or how many more long<br />

days we want to walk, we want to know more about<br />

Isidor’s Eagles. We know, though, that Isidor’s Eagles<br />

are the lords in the cloud forest and we hope they<br />

remain like that for a long time.<br />

17

Experiences of an Aplomado Falcon<br />

Hack Site Attendant<br />

Aplomado Falcon<br />

hack site.<br />

It is a struggle for me to<br />

awake at 5:30 a.m. <strong>The</strong><br />

by Swathi Sridharan 20-minute drive to<br />

work is different every morning,<br />

enthralling in the way of slowly<br />

revealed secrets: deer, vultures swooping<br />

on road kill, snakes, and an eastern<br />

sky that shines gently some mornings<br />

and burns fiercely on others.<br />

At around 8:00 am the first of the<br />

Aplomado Falcons makes its way to the<br />

tower, its black and gold form outlined<br />

clearly in my scope. Beautiful in their<br />

vivid colors and playful soaring flights,<br />

these birds have the ability to look like<br />

a fat pigeon one minute and like royalty<br />

the next. For the brief time that<br />

they are present, the tower is alive. <strong>The</strong><br />

falcons eat the quail with small, rapid<br />

bites, often ripping feathers to get to<br />

the unexposed flesh.<br />

<strong>The</strong> tower becomes still again after<br />

the birds have fed and they huddle<br />

together on the far side in the shade.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y scatter, screaming abuses when I<br />

approach at 11:30 to remove the bones,<br />

feathers, and any other remnants of<br />

their breakfast.<br />

Besides feeding and identifying the<br />

birds, my job also includes scaring off<br />

any approaching vultures that are interested<br />

in the quail on the tower. To do<br />

this I run out of the blind and wave my<br />

arms in silent protest until the vulture,<br />

feigning indifference, shifts direction<br />

with a lazy beat of its wings.<br />

At about one month of age, the falcons<br />

are flown in from <strong>The</strong> <strong>Peregrine</strong><br />

<strong>Fund</strong>’s headquarters, the World Center<br />

for Birds of Prey, in Boise, Idaho, and<br />

are delivered to us in specially<br />

designed carriers by one of the four<br />

supervisors stationed in Texas. Each<br />

release site usually receives two sets of<br />

birds, sometimes even three. <strong>The</strong><br />

young birds scream, bite, and scratch<br />

vehemently in protest at being moved<br />

18<br />

into the large wooden box on top of<br />

the tower where they will stay for<br />

about a week. This is one of the few<br />

times that the Aplomados are handled.<br />

I have transferred two females, Blue P8<br />