Collected works (pdf) - Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Collected works (pdf) - Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Collected works (pdf) - Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ALL IN A DAY’S WORK<br />

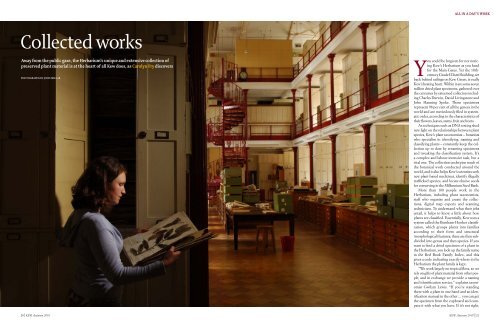

<strong>Collected</strong> <strong>works</strong><br />

Away from the public gaze, the Herbarium’s unique and extensive collection of<br />

preserved plant material is at the heart of all <strong>Kew</strong> does, as Carolyn Fry discovers<br />

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JOHN MILLAR<br />

You could be forgiven for not noticing<br />

<strong>Kew</strong>’s Herbarium as you head<br />

for the Main Gates. Yet the 18thcentury<br />

Grade II listed building, set<br />

back behind railings on <strong>Kew</strong> Green, is really<br />

<strong>Kew</strong>’s beating heart. Within it are some seven<br />

million dried plant specimens, gathered over<br />

the centuries by esteemed collectors including<br />

Charles Darwin, David Livingstone and<br />

John Hanning Speke. These specimens<br />

represent 98 per cent of all the genera in the<br />

world and are meticulously filed in systematic<br />

order, according to the characteristics of<br />

their flowers, leaves, stems, fruit and roots.<br />

As techniques such as DNA testing shed<br />

new light on the relationships between plant<br />

species, <strong>Kew</strong>’s plant taxonomists – botanists<br />

who specialise in identifying, naming and<br />

classifying plants – constantly keep the collection<br />

up to date by renaming specimens<br />

and tweaking the classification system. It’s<br />

a complex and labour-intensive task, but a<br />

vital one. The collection underpins much of<br />

the botanical work conducted around the<br />

world, and it also helps <strong>Kew</strong>’s scientists seek<br />

new plant-based medicines, identify illegally<br />

trafficked species, and locate elusive seeds<br />

for conserving in the Millennium Seed Bank.<br />

More than 100 people work in the<br />

Herbarium, including plant taxonomists,<br />

staff who organise and create the collections,<br />

digital map experts and scanning<br />

technicians. To understand what their jobs<br />

entail, it helps to know a little about how<br />

plants are classified. Essentially, <strong>Kew</strong> uses a<br />

system called the Bentham-Hooker classification,<br />

which groups plants into families<br />

according to their form and structural<br />

(morphological) features; these are then subdivided<br />

into genus and then species. If you<br />

want to find a dried specimen of a plant in<br />

the Herbarium, you look up the family name<br />

in the Red Book Family Index, and this<br />

gives a code indicating exactly where in the<br />

Herbarium the plant family is kept.<br />

“We work largely on tropical flora, so we<br />

rely on gifts of plant material from other people,<br />

and in exchange we provide a naming<br />

and identification service,” explains taxonomist<br />

Gwilym Lewis. “If you’re standing<br />

there with a plant in one hand and an identification<br />

manual in the other… you can get<br />

the specimen from the cupboard and compare<br />

it with what you have. If it’s not right,<br />

20 l KEW Autumn 2007 KEW Autumn 2007 l 21

ALL IN A DAY’S WORK<br />

ALL IN A DAY’S WORK<br />

Right and below: Emma<br />

Tredwell looks after the<br />

70,000 bottled specimens<br />

in the Spirit Collection<br />

Left: an expert in Latin<br />

American beans, Gwilym<br />

Lewis has worked in the<br />

Herbarium for 30 years<br />

Below: staff undertake<br />

family ‘sorts’ to decide<br />

which family each<br />

specimen belongs to<br />

Left and below: plant<br />

specimens are lent by<br />

or loaned out to research<br />

institutions worldwide<br />

All specimens belonging<br />

to the same plant family<br />

are stored together in<br />

adjacent cupboards<br />

Right: 98 per cent of the<br />

world’s plant genera are<br />

preserved and stored<br />

in <strong>Kew</strong>’s Herbarium<br />

The herbarium sheets<br />

displayas many aspects<br />

of the plants as possible,<br />

so they can be studied<br />

but it’s similar, in a systematically organised<br />

herbarium you just have to look at neighbouring<br />

files to find the matching specimen.”<br />

Because not all plant specimens can be<br />

pressed, the Herbarium also holds a Spirit<br />

Collection. This comprises 70,000 jars of<br />

fleshy fruits and complex flowers, such as<br />

orchids, stored in ‘<strong>Kew</strong> Mix’, a cocktail of<br />

methylated spirit, formaldehyde, glycerol<br />

and water, prepared by Spirit Collection manager<br />

Emma Tredwell. “The formaldehyde<br />

fixes the plants as they are, the alcohol stops<br />

fungus and mould attacking the sample, and<br />

the glycerol prevents it going brittle,” explains<br />

Emma. “These samples are cross-referenced<br />

to the Dried Collection.” Stored in an array<br />

of boxes, the Dried Collection comprises<br />

plant parts that are too big or awkwardly<br />

shaped to be pressed and mounted, such as<br />

large fruits or long palm fronds.<br />

Around half of the Herbarium staff are<br />

expert plant taxonomists who constantly<br />

hone the filing system by identifying and<br />

classifying new plant material and updating<br />

existing records. In addition to staff who<br />

specialise in monocot or dicot plants (those<br />

with one seed leaf or two), there are five<br />

regional teams that study the floras of dry<br />

Africa, wet Africa, South America, temperate<br />

regions and South-east Asia. Between<br />

them, these groups curate, name and<br />

update plant specimens stored in all corners<br />

of the Herbarium.<br />

Gwilym, who has worked at <strong>Kew</strong> for<br />

30 years, heads up the Leguminosae team.<br />

“I specialise in the peas and beans of Latin<br />

America,” he explains. “My main fieldwork<br />

patch has been Brazil. I manage a small<br />

team of people and conduct research on the<br />

economically important bean family, which<br />

mainly involves finding and describing new<br />

plants and getting them next to their brothers<br />

and sisters in the big system that is the<br />

tree of life. Then I write scientific papers<br />

and books to distribute that information to<br />

as wide an interested audience as possible.<br />

I do a little television and radio too. It’s very<br />

eclectic work and very interesting – there’s<br />

never a dull day.”<br />

Gwilym is just one of about 50 scientists<br />

who work at the Herbarium and in other<br />

countries from Madagascar to Peru. Added<br />

to this, regular visits by students and expert<br />

botanists from around the world means<br />

there is a constant flow of people passing<br />

through the building, from both the UK<br />

and worldwide, searching for and exchanging<br />

plant information.<br />

Sitting among the potted palms on the<br />

Herbarium’s top-floor verandah, watching<br />

the Thames below, Gwilym tells a story<br />

from the late 1980s that demonstrates the<br />

relevance of the work of <strong>Kew</strong>’s Herbarium.<br />

The HIV virus had just emerged, and scientists<br />

were keen to seek out plants<br />

containing anti-viral drugs. They found a<br />

promising chemical in Castanospermum<br />

australe, a tree endemic to eastern Australia.<br />

It only existed in small populations,<br />

so the researchers approached the Herbarium<br />

to see if it had a close relative that<br />

would yield the same or a similar drug. After<br />

much systematic detective work, scientists<br />

at <strong>Kew</strong> found exactly the same chemical in<br />

a group of plants in South America, and<br />

with permission collected samples of one<br />

species in the Amazon rainforest. “Only<br />

someone who identifies and classifies plants<br />

could have pointed researchers in the right<br />

direction, because without that knowledge<br />

you would never have thought to look in<br />

South America,” says Gwilym.<br />

“There’s a perception that a lot of woolly<br />

minded, grey-haired, eccentric hobbyists<br />

sit in the Herbarium fiddling about with<br />

whichever plant group interests them and<br />

that it doesn’t matter to anyone else,” he<br />

continues, “but the Herbarium, its collections<br />

and specialist taxonomists are central<br />

to all botanical research.”<br />

Anyone studying a particular plant<br />

group and the relationships between different<br />

species within it will generally need to<br />

look at many different specimens. So every<br />

day <strong>Kew</strong>’s staff borrow specimens or accept<br />

gifts of material from herbaria around the<br />

world, and send out samples to scientists<br />

working in other countries. Imports of<br />

material are not allowed to enter the<br />

Herbarium building until they have been<br />

frozen for three days at -35°C. This ensures<br />

that any pests that might eat the specimens,<br />

such as herbarium beetles, don’t make it<br />

into the collection.<br />

Once the specimens have been given the<br />

all clear, they are taken to the Collections<br />

Management Unit. Here, piles of specimens,<br />

all sandwiched between sheets of<br />

ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPH: ANDREW McROBB/RBG KEW<br />

22 l KEW Autumn 2007 KEW Autumn 2007 l 23

ALL IN A DAY’S WORK<br />

ALL IN A DAY’S WORK<br />

Right: the digital maps<br />

made in the GIS Unit<br />

are a valuable aid to<br />

conservation work<br />

Left and below: the<br />

collection is a vital<br />

resource for <strong>Kew</strong>’s palm<br />

expert Bill Baker<br />

Right: the herbarium<br />

sheets are being scanned<br />

so they can be made<br />

available online<br />

Left: with 30,000 new<br />

additions each year, space<br />

is rapidly running out, so<br />

a new wing is being built<br />

Above: whenever DNA<br />

research uncovers new<br />

plant relationships, the<br />

records must be updated<br />

Plant parts that are too<br />

awkwardly shaped to be<br />

pressed are instead dried<br />

and stored in boxes<br />

Above: pheromone traps<br />

are used to help protect<br />

the collection from pests<br />

such as cigarette beetle<br />

More than 100 staff<br />

work in the Herbarium,<br />

from plant scientists to<br />

digital map experts<br />

acid-free card, cover a large desk and fill<br />

walls of wooden pigeonholes and metal<br />

shelves. This incoming material is carefully<br />

labelled, then awaits collection by the<br />

botanist who requested it. Outgoing material<br />

is placed in mailboxes according to their<br />

destination – usually universities or other<br />

herbaria. As backup to the military-precise<br />

operation, all material is entered into a<br />

computer system, so each plant specimen’s<br />

journey around the world can be traced at<br />

the click of a mouse.<br />

Computers are also proving their worth<br />

in other areas of the building. As part of<br />

<strong>Kew</strong>’s remit to make its collections more<br />

widely available, it has begun digitising and<br />

barcoding some of the Herbarium specimens.<br />

Each day, a dedicated team inputs<br />

information about when and where a plant<br />

was collected, together with its present<br />

name and any past variations, to a database<br />

called HerbCat (not to be confused with<br />

the Herbarium cat, a black and white stray<br />

called Fluff!). This information is accessible<br />

over the internet. By June 2007, the<br />

Digitisation Department had catalogued<br />

more than 250,000 specimens.<br />

Meanwhile, the GIS Unit (Geographic<br />

Information System) is dedicated to producing<br />

digital maps. By inputting environmental<br />

data such as altitude, soil type and annual<br />

rainfall, the team can show botanists where<br />

they’re most likely to find certain species.<br />

Or they can use information from herbarium<br />

specimens to plot maps showing where<br />

certain rare species are concentrated. “We<br />

are about to finish a vegetation map of<br />

Madagascar,” says spatial information scientist<br />

Susana Baena. “In Madagascar, the<br />

authorities are trying to increase the amount<br />

of land that is set aside for reserves. They’ll<br />

be able to use the vegetation map to decide<br />

which areas are the best ones to protect.”<br />

Politicians around the world can make conservation<br />

decisions based on the work of<br />

<strong>Kew</strong>’s GIS Unit.<br />

Today, next door to the present site,<br />

a new £15 million additional building is<br />

under construction. This will enable the<br />

Herbarium collection to grow by some two<br />

million specimens, so at its present rate<br />

of 30,000 new additions a year it won’t be<br />

full for a good few decades. Solving the<br />

problem of storage has created a new<br />

conundrum for the Herbarium staff, however<br />

– whether to do away with the old<br />

Bentham-Hooker system of classification in<br />

favour of a more up-to-date filing system<br />

based on recent molecular studies. Some<br />

botanists have suggested switching to an<br />

entirely new filing system based on DNA<br />

sequencing. Botany students now learn<br />

this method of classification, so in many<br />

ways it makes sense to switch, but changing<br />

to the new system represents a massive<br />

upheaval for staff in the Herbarium and<br />

across the <strong>Gardens</strong>. It’s just one of the many<br />

important dialogues that engage the Herbarium<br />

staff every day.<br />

Whichever classification <strong>Kew</strong> opts for,<br />

the plants will still be professionally curated<br />

and readily accessible for generations<br />

to come. This is what makes the Herbarium<br />

and its experts such a valuable resource.<br />

“A herbarium with specimens organised<br />

systematically underpins all other branches<br />

of botanical science,” asserts Gwilym. “The<br />

study of plant diversity cannot progress and<br />

has no working hypothesis without us.”<br />

The Herbarium might not be the focus<br />

of most visitors as they approach the<br />

<strong>Gardens</strong>’ Main Gates, but within its rabbitwarren<br />

of corridors and cubby holes, <strong>Kew</strong>’s<br />

experts are daily boosting our understanding<br />

of the world’s flora and disseminating<br />

that knowledge to help preserve plant biodiversity<br />

for the future.<br />

n<br />

Carolyn Fry is a freelance science writer and<br />

author of the BBC book The World of <strong>Kew</strong><br />

ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPH: RBG KEW<br />

24 l KEW Autumn 2007 KEW Autumn 2007 l 25