American Magazine April 2014

American University is located in Washington, D.C., at the top of Embassy Row. Chartered by Congress in 1893 to serve the public interest and build the nation, the university educates active citizens who apply knowledge to the most pressing concerns facing the nation and world. Students engage with leading faculty experts and world leaders, learning how to create change and address issues including the global economic crisis, health care, human rights and justice, diversity, the environment and sustainability, immigration, journalism’s transformation, corporate governance, and governmental reform.

American University is located in Washington, D.C., at the top of Embassy Row. Chartered by Congress in 1893 to serve the public interest and build the nation, the university educates active citizens who apply knowledge to the most pressing concerns facing the nation and world.

Students engage with leading faculty experts and world leaders, learning how to create change and address issues including the global economic crisis, health care, human rights and justice, diversity, the environment and sustainability, immigration, journalism’s transformation, corporate governance, and governmental reform.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

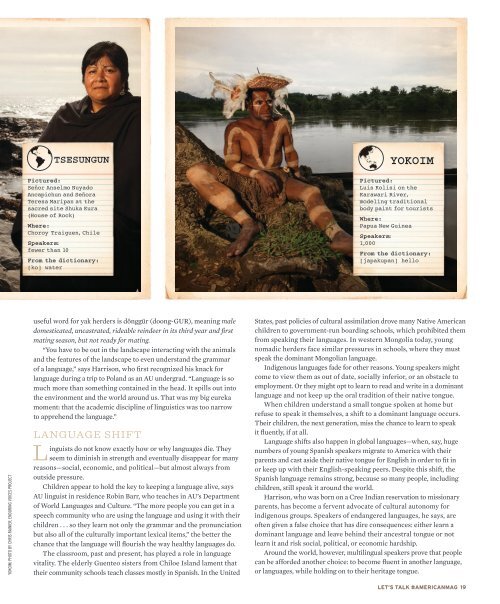

TSESUNGUN<br />

Pictured:<br />

Señor Anselmo Nuyado<br />

Ancapichun and Señora<br />

Teresa Maripan at the<br />

sacred site Shuka Kura<br />

(House of Rock)<br />

Where:<br />

Choroy Traiguen, Chile<br />

Speakers:<br />

fewer than 10<br />

From the dictionary:<br />

[ko] water<br />

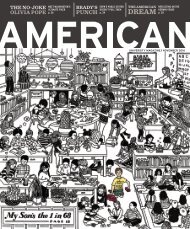

YOKOIM<br />

Pictured:<br />

Luis Kolisi on the<br />

Karawari River,<br />

modeling traditional<br />

body paint for tourists<br />

Where:<br />

Papua New Guinea<br />

Speakers:<br />

1,000<br />

From the dictionary:<br />

[japakupan] hello<br />

YOKOIM: PHOTO BY CHRIS RAINIER, ENDURING VOICES PROJECT<br />

useful word for yak herders is dönggür (doong-GUR), meaning male<br />

domesticated, uncastrated, rideable reindeer in its third year and first<br />

mating season, but not ready for mating.<br />

“You have to be out in the landscape interacting with the animals<br />

and the features of the landscape to even understand the grammar<br />

of a language,” says Harrison, who first recognized his knack for<br />

language during a trip to Poland as an AU undergrad. “Language is so<br />

much more than something contained in the head. It spills out into<br />

the environment and the world around us. That was my big eureka<br />

moment: that the academic discipline of linguistics was too narrow<br />

to apprehend the language.”<br />

LANGUAGE SHIFT<br />

Linguists do not know exactly how or why languages die. They<br />

seem to diminish in strength and eventually disappear for many<br />

reasons—social, economic, and political—but almost always from<br />

outside pressure.<br />

Children appear to hold the key to keeping a language alive, says<br />

AU linguist in residence Robin Barr, who teaches in AU’s Department<br />

of World Languages and Culture. “The more people you can get in a<br />

speech community who are using the language and using it with their<br />

children . . . so they learn not only the grammar and the pronunciation<br />

but also all of the culturally important lexical items,” the better the<br />

chance that the language will flourish the way healthy languages do.<br />

The classroom, past and present, has played a role in language<br />

vitality. The elderly Guenteo sisters from Chiloe Island lament that<br />

their community schools teach classes mostly in Spanish. In the United<br />

States, past policies of cultural assimilation drove many Native <strong>American</strong><br />

children to government-run boarding schools, which prohibited them<br />

from speaking their languages. In western Mongolia today, young<br />

nomadic herders face similar pressures in schools, where they must<br />

speak the dominant Mongolian language.<br />

Indigenous languages fade for other reasons. Young speakers might<br />

come to view them as out of date, socially inferior, or an obstacle to<br />

employment. Or they might opt to learn to read and write in a dominant<br />

language and not keep up the oral tradition of their native tongue.<br />

When children understand a small tongue spoken at home but<br />

refuse to speak it themselves, a shift to a dominant language occurs.<br />

Their children, the next generation, miss the chance to learn to speak<br />

it fluently, if at all.<br />

Language shifts also happen in global languages—when, say, huge<br />

numbers of young Spanish speakers migrate to America with their<br />

parents and cast aside their native tongue for English in order to fit in<br />

or keep up with their English-speaking peers. Despite this shift, the<br />

Spanish language remains strong, because so many people, including<br />

children, still speak it around the world.<br />

Harrison, who was born on a Cree Indian reservation to missionary<br />

parents, has become a fervent advocate of cultural autonomy for<br />

indigenous groups. Speakers of endangered languages, he says, are<br />

often given a false choice that has dire consequences: either learn a<br />

dominant language and leave behind their ancestral tongue or not<br />

learn it and risk social, political, or economic hardship.<br />

Around the world, however, multilingual speakers prove that people<br />

can be afforded another choice: to become fluent in another language,<br />

or languages, while holding on to their heritage tongue.<br />

LET’S TALK #AMERICANMAG 19