Eswaran -Judgment CDJ 2010 MHC 6929.pdf - People's watch

Eswaran -Judgment CDJ 2010 MHC 6929.pdf - People's watch

Eswaran -Judgment CDJ 2010 MHC 6929.pdf - People's watch

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>CDJ</strong> <strong>2010</strong> <strong>MHC</strong> 6929<br />

Court : Before the Madurai Bench of Madras High Court<br />

Case No : W.P.(MD)No.6825 of 2006 & M.P.(MD).Nos.1 & 2 of 2006<br />

Judges: THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE S. MANIKUMAR<br />

Parties : Priya Versus The State of Tamil Nadu & Others<br />

Appearing Advocates : For the Petitioner: R. Karunanidhi for Henri Tiphagne, Advocates.<br />

For the Respondents: Pala. Ramasamy, Special Government Pleader.<br />

Date of <strong>Judgment</strong> : 24-08-<strong>2010</strong><br />

Head Note :-<br />

Constitution of India - Article 226 –<br />

Criminal Procedure Code - Section 174 –<br />

Indian Penal Code - Sections 366, 506(i) & 376 –<br />

TNPSS (D&A) Rules 1955 - Rule 3(b) -<br />

<strong>Judgment</strong> :-<br />

(PRAYER: Petition filed under Article 226 of the Constitution of India for the issuance of a<br />

Writ of Mandamus, directing the respondents 1 to 8 to pay to the petitioner, compensation of<br />

a sum of Rs.5,00,000/- to prosecute the delinquent police officials on the basis of a fair an<br />

impartial investigation and to take disciplinary action against the police personnel and others<br />

responsible for the wrongful confinement, torture and the murder of the petitioner's<br />

husband.)<br />

1. Wife of one Kutitiappan @ Bhoominathan, alleged to have been taken into custody by the<br />

police officials, Palam Police Station, Tirunelveli, and tortured to death, has filed the writ<br />

petition for a mandamus directing the respondents 1 to 7 to pay compensation of<br />

Rs.5,00,000/- and for a further direction to prosecute the officials responsible for her<br />

husband's death on the basis of a fair and impartial investigation and also for a direction to<br />

take disciplinary action against the police personnel and others, responsible for wrongful<br />

confinement, torture and death of her husband.<br />

2. It is the case of the petitioner that one Mr.Muthumaalai, paternal uncle of the deceased<br />

Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan, was residing at Abishekpatti, with his family. His son santhosh<br />

fell in love with Maria Sujatha, daughter of Chellaiah, a police constable, working in traffic<br />

division, at Palayamkottai. Both belong to Scheduled Caste Arundhathiyar Community. The

said santhosh and Maria Sujatha got their marriage registered on 05.06.2003 at<br />

Palayamkottai. The Police Constable Chellaiah, preferred a complaint to Palayamkottai<br />

Police Station alleging that santhosh had kidnapped Sujatha. He has also made a<br />

representation to the then Commissioner of Police, who in turn entrusted the same to the<br />

Inspector of Police, Palam Police Station.<br />

3. The petitioner has further submitted that one Arumuga Nainar, maternal uncle of the<br />

abovesaid santhosh runs a grocery shop at Manimoortheeswaram. On 14.06.2003, about<br />

10.30 p.m., when he was closing the shop, a police jeep came there with 8 constables of<br />

Palam Police Station, Tirunelveli, and asked him to take them to Kuttiappan @<br />

Bhoominathan's house. The Police Constables were not in uniform. When the said Arumuga<br />

Nainar, took the police to Manimoorthieeswaram, a village meeting was going on. The<br />

deceased Bhoominathan was also present. When the police wanted to take him, the<br />

villagers told the constables that they would bring both santhosh and Kuttiappan @<br />

Bhoominathan on the next day morning. However, the said Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan<br />

was taken by the police in the jeep.<br />

4. The petitioner has further submitted that on the next day morning ie. on 15.06.2003,<br />

about 9.00 a.m., Arumuga Nainar along with one Baliah went to the police station and they<br />

saw the said Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan, in a weak condition. On seeing them, Kuttiappan<br />

@ Bhoominathan told them that policemen had beaten him up. On the same day, about<br />

1.00 p.m., the constables whispered among themselves that santhosh and the girl had<br />

surrendered themselves in Palayamkottai Police Station and thereafter, the constables told<br />

that all of them can go home and sent accordingly them back.<br />

5. The petitioner has further stated that when she enquired Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan as<br />

to why he appeared to be so weak, he told that the policemen of Palam Police Station, hit<br />

him with lathis on his thigh, chest and stamped him on the groin. There was a blood clot in<br />

his left chest region and scratches on his thigh region. On the next day morning i.e. on<br />

16.06.2003 by 6.00 a.m., the petitioner tried to wake up Kuttiappan, but he did not wake up.<br />

Immediately, the neighbours came there and hired an auto rickshaw and took him to<br />

Subramanian Hospital, Tirunelveli Junction. The doctor, who examined him told them take<br />

him to Government hospital. Thereafter, he was taken to Tirunelveli Government Hospital,<br />

where he was declared as dead.

6. The petitioner has further submitted that on 16.09.2003, '<strong>People's</strong> Watch – Tamil Nadu', a<br />

human rights organisation sent complaints to National Human Rights Commission, State<br />

Human Rights Commission, Director of National Commission for SC/ST at Chennai, Director<br />

of Adi Dravida Welfare Department, Chennai and the District Collector of Tirunelvei.<br />

Mr.Lakshmanan, father of the deceased Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan sent an intimation to<br />

the National Commission on Human Rights on 16.06.2003 and gave a petition to the District<br />

Judge, on 26.08.2004. The Commission by its order dated 15.07.2003, directed the Director<br />

General of Police, Chennai, to collect the reports from the concerned authorities and seek<br />

explanation as to why intimation about the custodial death was not given in time. But no final<br />

order was passed so far.<br />

7. The petitioner has further submitted that the deceased was only the breadwinner of the<br />

family and the deceased used to get an income of Rs.4,000/- per month by doing painting<br />

work. In these circumstances, the petitioner has filed the present writ petition for the relief,<br />

as stated above.<br />

8. The Commissioner of Police, Tirunelveli, the 8th respondent herein, has filed a counter<br />

affidavit on behalf of other respondents and denied the contention that Kuttiappan @<br />

Bhoominathan died due to torture by certain police officials of Palayam Police Station,<br />

Tirunelveli. He has further stated that Thiru Chelliah, Head Constable No.571 of<br />

Palayamkottai Traffic, preferred a complaint at Palayamkottai Police station on 05.06.2003<br />

that santhosh, S/o.Muthumalai had kidnapped his daughter Maria Sujatha on 04.06.2003.<br />

The said Chellaiah, submitted a petition to the Commissioner of Police, Tirunelveli City and<br />

the same was endorsed to the Inspector, Thachanallur, for enquiry in<br />

C.No.43/COP/Tin.City/2003. One Thiru A.Sankaralingam the incharge Inspector of Police,<br />

Thachanallur Police Station on 14.06.2003, has deputed HC 282 Ponniah, HC 481<br />

Karuthiah, HC 343 Ponnulingam and HC 897 Sudalaikannu, to summon Santhosh for<br />

enquiry. Since Santhosh had absconded, the police party brought Kuttiappan @<br />

Bhoominathan and his maternal uncle Nainar and searched for Santhosh on 14.06.2003<br />

night, at Abishekapatti, Palayamkottai and other places and sent the police team back to<br />

Manimoortheeswaram on 15.06.2003 early morning. Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan was<br />

halting in his house for a day on 15.06.2003 and on 16.06.2003 morning, Kuttiappan @<br />

Bhoominathan suffered illness and was admitted in T.V.M.C. Hospital, Palayamkottai at<br />

06.55 hrs. by his father Lakshmanan and the Medical Officer declared him dead.

9. The Commissioner of Police, Tirunelveli City, has further submitted that on the complaint<br />

of Lakshmanan, father of the deceased, a case in Thachanallur Police Station in Cr.No.882<br />

of 2003 under Section 174 of Cr.P.C. was registered on 16.06.2003 and that the same was<br />

investigated by the Revenue Divisional Officer, Tirunelveli. Postmortem examination was<br />

conducted over the dead body. At the time of filing of the counter affidavit, the enquiry report<br />

of the Revenue Divisional Officer, Tirunelveli, was awaited. According to the 8th respondent,<br />

in the meantime Maria Sujatha escaped from the illegal custody of Santhosh, from the<br />

house of one Mr.Daniel, a friend of Santhosh and she preferred a complaint to<br />

Palayamkottai Police Station on 15.06.2003 that she was kidnapped and by threat and<br />

force, she was raped by Santhosh at Madurai. On the basis of her complaint, a case in<br />

Crime No.1562 of 2003 under Sections 366, 506(i) and 376 IPC was registered on the file of<br />

Palayamkottai Police Station and that the case is pending trial.<br />

10. The 8th respondent has further submitted that Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan and Nainar<br />

accompanied the police party for the purpose of identifying and to show the hideouts of the<br />

absconding person Santhosh and the deceased was never tortured by the police. According<br />

to him, the deceased was not in wrongful confinement, tortured, harassed or illtreated and<br />

both the deceased and the said Nainar, only accompanied the police party to identify and<br />

point out the probable hideouts of the absconding Santhosh. As the investigation into the<br />

death of Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan in Crime No.882 of 2003 on the file of Thachanallur<br />

Police Station and the enquiry under P.S.O.145 (New Edition PSO 151) was pending at the<br />

time of filing of the counter affidavit, with Government, the 8th respondent has submitted<br />

that the writ petition is premature and therefore, prayed for dismissal.<br />

11. Heard the learned counsel appearing for the parties and perused the materials available<br />

on record.<br />

12. The counter affidavit of the incharge of Commissioner of Police, Tirunelveli City, has<br />

been filed in the year 2006, before the order of the Government in G.O.Ms.No.1400, Public<br />

(Law and Order-E) Department, dated 30.11.2006, wherein, the Government after<br />

considering the enquiry report under P.S.O.145 (New Order P.S.O.151) have found that the<br />

deceased had been taken to the police station on 14.06.2003 and contrary to the Rules,<br />

detained in Palam Police Station throughout the night.<br />

13. On perusal of the statements of the police officials and the documents, the Government

have also categorically found that the contention of the police officials that the said<br />

Bhoominathan was not detained on the night of 14.06.2003 in the police station, was false<br />

and as the enquiry conducted by the Revenue Divisional Officer, Tirunelveli, has<br />

categorically proved that the police personnel PC 892 Sudalaikannu; PC 283 Ponnaiah; PC<br />

481 Karuthaiah and PC 343 Ponnurangam had unlawfully detained the deceased person in<br />

the police station and therefore, the Government have issued orders directing prosecution<br />

against those policemen for the criminal acts. In respect of acts, which do not fall under the<br />

penal laws, disciplinary action has also been directed to be taken against the said<br />

policemen.<br />

14. While taking disciplinary action, the Director General of Police, Chennai, was further<br />

directed to follow the guidelines given in Government Letter No.1118/Ser.No/87/P&AR<br />

Department, dated 22.12.1987. In response to the said Government Letter, the Director<br />

General of Police, Tamil Nadu, Chennai, in his Memorandum Rc.No.258171/Con.III(3)/06,<br />

dated 28.12.2006, has directed the Deputy Inspector General of Police, Tirunelveli Range to<br />

initiate departmental action under Rule 3(b) of TNPSS (D&A) Rules 1955, against the<br />

abovesaid policemen and nominate the Additional Superintendent of Police, Tirunelveli<br />

District, as the enquiry officer to conduct the above PRs.<br />

15. In yet another Memorandum in Rc.No.258171/Con.III(3)/06, dated 14.02.2007, the<br />

Director General of Police, Chennai, has directed the Commissioner of Police, Tirunelveli, to<br />

take immediate disciplinary action against the abovesaid policemen and to collect the<br />

G.O.Ms.No.1400, Public (L&O.E) Department, dated 30.11.2006 and the enquiry report of<br />

RDO, Tirunelveli and other connected records from the Deputy Inspector General of Police,<br />

Tirunelveli Range and take action and send the report to Chief Office immediately, as<br />

directed by his earlier letter dated 28.12.2006.<br />

16. Perusal of the copy of the files shows that pursuant to above departmental action has<br />

been taken against the above said police personnels in P.R.Nos.50/07 to 53/07. The<br />

charges levelled against the policemen are one and the same and the same is extracted<br />

hereunder:-<br />

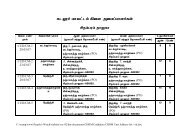

“ TAMIL"<br />

17. Perusal of the files further disclose that the Government in Letter No.3021/L&O-E/2009-

2, dated 04.02.<strong>2010</strong>, have decided to accept the proved minute drawn up by the department<br />

enquiry officer and a punishment of “Postponement of increment for a period of two years<br />

without cumulative effect has been awarded to them, as adequate.<br />

18. Files also disclose that as against the policemen, who were involved in the death of<br />

Kuttiappan @ Bhoominathan, prosecution has been launched in Crime No.691 of 2004<br />

under Sections 304, 342 and 331 of IPC and that the same is pending before the learned<br />

Chief Judicial Magistrate, Tirunelveli.<br />

19. The counter affidavit of the Commissioner of Police, Tirunelveli, praying for dismissal of<br />

the writ petition, filed before the issuance of G.O.Ms.No.1400, Public (Law and Order-E)<br />

Department, dated 30.11.2006, is liable to be rejected, in view of the subsequent<br />

development that the Government in the above referred Government Order, have ordered to<br />

initiate both criminal prosecution and departmental action against the policemen, in<br />

connection with the torture and involvement in the death of the deceased Kuttiappan @<br />

Bhoominathan, on 16.06.2003. The only question 2006, the prayer sought for in the writ<br />

petition to issue a mandamus to prosecute the said officials and to take disciplinary action,<br />

who were responsible for wrongful confinement and torture.<br />

20. The only question, which remains to be considered as to whether the petitioner is<br />

entitled to compensation of Rs.5,00,000/- from the respondents 1 to 8.<br />

21. In this context, it is useful to refer G.O.Ms.No.1401, Public (Law and Order-E)<br />

Department, 30.11.2006, wherein, after considering the representation of the writ petitioner,<br />

for compensation of Rs.5,00,000/- and for employment assistance, and having regard to the<br />

procedure to be followed in existing G.O.Ms.No.153, Public (Law and Order-B) Department,<br />

dated 31.01.1998, the Government have awarded a sum of Rs.1,00,000/- to the writ<br />

petitioner holding that the petitioner's husband died due to the torture and harassment and<br />

in the custody of the police.<br />

22. On the question of payment of compensation to the victims of torture, physical assault,<br />

humiliation, rape, custodial death and where there is an infringement of constitutional right<br />

to life and liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, the Hon'ble Supreme Court<br />

has ordered compensation in cases where investigation is pending and also in cases, after<br />

the conclusion of the proceedings, taken against the police officials involved.

23. In Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar, reported in (1983) 4 SCC 141, the Apex Court held as<br />

follows:<br />

“....But we have no doubt that if the petitioner files a suit to recover damages for his illegal<br />

detention, a decree for damages would have to be passed in that suit, though it is not<br />

possible to predicate, in the absence of evidence, the precise amount which would be<br />

decreed in his favour. In these circumstances, the refusal of this Court to pass an order of<br />

compensation in favour of the petitioner will be doing mere lip-service to his fundamental<br />

right to liberty which the State Government has so grossly violated. Article 21 which<br />

guarantees the right to life and liberty will be denuded of its significant content if the power<br />

of this Court were limited to passing orders of release from illegal detention. One of the<br />

telling ways in which the violation of that right can reasonably be prevented and due<br />

compliance with the mandate of Article 21 secured, is to mulct its violators in the payment of<br />

monetary compensation. Administrative sclerosis leading to flagrant infringements of<br />

fundamental rights cannot be corrected by any other method open to the judiciary to adopt.<br />

The right to compensation is some palliative for the unlawful acts of instrumentalities which<br />

act in the name of public interest and which present for their protection the powers of the<br />

State as a shield. If civilisation is not to perish in this country as it has perished in some<br />

others too well known to suffer mention, it is necessary to educate ourselves into accepting<br />

that, respect for the rights of individuals is the true bastion of democracy. Therefore, the<br />

State must repair the damage done by its officers to the petitioner’s rights. It may have<br />

recourse against those officers.<br />

24. In Sebastian M.Hongroy Vs. Union of India reported in AIR 1984 SC 1026 : (1984 Cri LJ<br />

830), the Apex Court ordered payment of compensation to the wife of the victim who<br />

suffered torture, agony and mental oppression and in Bhim Singh Vs. State of Jammu &<br />

Kashmir [1985 (4) SCC 677], the Apex Court held as follows:<br />

“We do not have the slightest hesitation in holding that Shri Bhim Singh was not produced<br />

before the Executive Magistrate First Class on llth and was not produced before the Sub-<br />

Judge on 13th. Orders of remand were obtained from the Executive Magistrate and the Sub-<br />

Judge on the applications of the police officers without the production of Shri Bhim Singh<br />

before them. The manner in which the orders were obtained i.e. at the residence of the<br />

Magistrate and the Sub-Judge after office hours, indicates the surreptitious nature of the

conduct of the police. The Executive Magistrate and the Sub-Judge do not at all seem to<br />

have been concerned that the person whom they were remanding to custody had not been<br />

produced before them. They acted in a very casual way and we consider it a great pity that<br />

they acted without any sense of responsibility or genuine concern for the liberty of the<br />

subject. The police officers, of course, acted deliberately and mala fide and the Magistrate<br />

and the Sub-Judge aided them either by colluding with them or by their casual attitude. We<br />

do not have any doubt that Shri Bhim Singh was not produced either before the Magistrate<br />

on 11th or before the Sub-Judge on 13th, though he was arrested in the early hours of the<br />

morning of 10th. There certainly was a gross violation of Shri Bhim Singh’s constitutional<br />

rights under Articles 21 and 22(2).<br />

We can only say that the police officers acted in a most high-handed way. We do not wish to<br />

use stronger words to condemn the authoritarian acts of the police. If the personal liberty of<br />

a Member of the Legislative Assembly is to be played with in this fashion, one can only<br />

wonder what may happen to lesser mortals Police officers who are the custodians of law<br />

and order should have the greatest respect for the personal liberty of citizens and should not<br />

flout the laws by stooping to such bizarre acts of lawlessness. Custodians of law and order<br />

should not become depredators of civil liberties. Their duty is to protect and not to abduct.<br />

However the two police officers, the one who arrested him and the one who obtained the<br />

orders of remand, are but minions, in the lower rungs of the ladder. We do not have the<br />

slightest doubt that the responsibility lies elsewhere and with the higher echelons of the<br />

Government of Jammu and Kashmir but it is not possible to say precisely where and with<br />

whom, on the material now before us. We have no doubt that the constitutional rights of Shri<br />

Bhim Singh were violated with impunity. Since he is now not in detention, there is no need to<br />

make any order to set him at liberty, but suitably and adequately compensated, he must be.<br />

Any order to set him at liberty, but suitably and adequately compensated, he must be. That<br />

we have the right to award monetary compensation by way of exemplary costs or otherwise<br />

is now established by the decisions of this Court in Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar, reported in<br />

(1983) 4 SCC 141 and Sebastian M.Hongroy Vs. Union of India reported in AIR 1984 SC<br />

1026 : (1984 Cri LJ 830). When a person comes to us with the complaint that he has been<br />

arrested and imprisoned with mischievous or malicious intent and that his constitutional and<br />

legal rights were invaded, the mischief or malice and the invasion may not be washed away<br />

or wished away by his being set free. In appropriate cases we have the jurisdiction to<br />

compensate the victim by awarding suitable monetary compensation. We consider this an<br />

appropriate case. We direct the first respondent, the State of Jammu and Kashmir to pay to

Shri Bhim Singh a sum of Rs 50,000 within two months from today. The amount will be<br />

deposited with the Registrar of this Court and paid to Shri Bhim Singh”.<br />

25. In M.C. Mehta v. Union of India reported in A.I.R. 1987, S.C. 1086, dealing with a writ<br />

petition filed for closure of certain units, the Supreme Court observed that when violations of<br />

fundamental right is brought to the notice of the Court, then hypertechnical approach should<br />

not be avoided, to meet the ends of justice. The Apex Court has observed as follows:<br />

“Where during the pendency of a writ petition filed by Legal Aid and Advice Board and Bar<br />

Association for Closure of certain units of a company on ground of health hazard, there was<br />

leakage of oleum gas, the Supreme Court could entertain applications for compensation for<br />

damage even though the writ petition did not amend the writ petition to include the claim for<br />

compensation. The applications for compensation are for enforcement of the fundamental<br />

right to life enshrined in Art 21 of the Constitution and while dealing with such applications, a<br />

hyper-technical approach which would defeat the ends of justice could not be adopted. If the<br />

Court is prepared to accept a letter complaining of violation of the fundamental right of an<br />

individual or a class of individuals who cannot approach the Court for Justice, there is no<br />

reason why the applications for compensation which have been made for enforcement of<br />

the fundamental right of the persons affected by the oleum gas leak under Art. 21 should not<br />

be entertained. The Court while dealing with an application for enforcement of a<br />

fundamental right must look at the substance and not the form”.<br />

26. In <strong>People's</strong> Union for Democratic Rights v. Police Commr., reported in (1989) 4 SCC<br />

730, there was report by the Deputy Commissioner, accepting the atrocities committed by<br />

the police officers and that the matter was investigated for criminal prosecution. In the above<br />

said circumstances, the Apex Court directed a sum of Rs.50,000/- to be paid to the family of<br />

the deceased, as compensation which would be invested in a proper manner so that the<br />

destitute's family might get some amount every month towards their expenses. The relevant<br />

paragraphs are extracted hereunder:<br />

“4. Under the above circumstances we direct that the family of Ram Swaroop who is dead<br />

will be paid Rs 50,000 as compensation, which will be invested in some scheme under the<br />

Life Insurance Corporation, so that the destitute family may get some amount monthly and<br />

the money may also be kept secured. It is also directed that Petitioner 2 Patasi who was<br />

stripped of her clothes at the police station, shall be paid Rs 500 as compensation and the 8

other persons namely (1) Dandwa (2) Ram Prasad (3) Jaipal (4) Mahavir (5) Kannu (6)<br />

Munsjia (7) Hukka and (8) Pratap, who were taken in the police station without being paid<br />

for their work, will be paid Rs 25 each. It is directed that after investigation and inquiry<br />

officers who are found guilty, the amount paid as compensation or part thereof may be<br />

recovered from these persons out of their salaries after giving them opportunity to show<br />

cause.<br />

5. This order will not prevent any lawful action for compensation. But in case some<br />

compensation is ordered by a competent court, this will be given credit to.<br />

27. In the above reported case, though the District Collector had recommended only<br />

department action against the erring officials namely, the Inspector of Police, the Sub<br />

Inspector of Police, the Government took a decision to prosecute the officials. As stated<br />

supra, though this Court has already dismissed the writ petition, challenging the<br />

Government Order in G.O.Ms.No.1094, Public (Law and Order-A) Department, dated<br />

26.09.2008, the above reported judgment would fortify the views of this Court that the<br />

Government, the ultimate authority can disagree with the opinion/recommendation of the<br />

District Collector and order for prosecution in addition to departmental action.<br />

28. In Saheli v. Commr. of Police, reported in (1990) 1 SCC 422, dealing with custodial<br />

death and compensation, the Hon'ble Supreme Court held as follows:<br />

“10. It is now apparent from the report dated December 5, 1987 of the Inspector of the<br />

Crime Branch, Delhi as well as the counter-affidavit of the Deputy Commissioner of Police,<br />

Delhi on behalf of the Commissioner of Police, Delhi and also from the fact that the<br />

prosecution has been launched in connection with the death of Naresh, son of Kamlesh<br />

Kumari showing that Naresh was done to death on account of the beating and assault by<br />

the agency of the sovereign power acting in violation and excess of the power vested in<br />

such agency. The mother of the child, Kamlesh Kumari, in our considered opinion, is so<br />

entitled to get compensation for the death of her son from respondent 2, Delhi<br />

Administration.<br />

11. An action for damages lies for bodily harm which includes battery, assault, false<br />

imprisonment, physical injuries and death. In case of assault, battery and false<br />

imprisonment the damages are at large and represent a solatium for the mental pain,

distress, indignity, loss of liberty and death. As we have held hereinbefore that the son of<br />

Kamlesh Kumari aged 9 years died due to beating and assault by the SHO, Lal Singh and<br />

as such she is entitled to get the damages for the death of her son. It is well settled now that<br />

the State is responsible for the tortious acts of its employees. Respondent 2, Delhi<br />

Administration is liable for payment of compensation to Smt. Kamlesh Kumari for the death<br />

of her son due to beating by the SHO of Anand Parbat Police Station, Shri Lal Singh.<br />

12. It is convenient to refer in this connection the decision in Joginder Kaur v. Punjab State<br />

reported in 1969 ACJ 28 (P & H) wherein it has been observed that:<br />

“In the matter of liability of the State for the torts committed by its employees, it is now the<br />

settled law that the State is liable for tortious acts committed by its employees in the course<br />

of their employment.”<br />

13. In State of Rajasthan v. Vidhyawati reported in 1962 Supp (2) SCR 989, it has been held<br />

that:<br />

“Viewing the case from the point of view of first principles, there should be no difficulty in<br />

holding that the State should be as much liable for tort in respect of a tortious act committed<br />

by its servant within the scope of his employment and functioning as such as any other<br />

employer. The immunity of the Crown in the United Kingdom, was based on the old<br />

feudalistic notions of justice, namely, that the King was incapable of doing a wrong, and,<br />

therefore, of authorising or instigating one, and that he could not be sued in his own courts.<br />

In India, ever since the time of the East India Company, the sovereign has been held liable<br />

to be sued in tort or in contract, and the Common Law immunity never operated in India.”<br />

14. In Peoples’ Union for Democratic Rights v. Police Commissioner, Delhi Police<br />

Headquarters [1989 (4) SCC 730] one of the labourers who was taken to the police station<br />

for doing some work and on demand for wages was severely beaten and ultimately<br />

succumbed to the injuries. It was held that the State was liable to pay compensation and<br />

accordingly directed that the family of the deceased labourer will be paid Rs 75,000 as<br />

compensation.<br />

15. On a conspectus of these decisions we deem it just and proper to direct the Delhi<br />

Administration, respondent 2 to pay compensation to Kamlesh Kumari, mother of the

deceased, Naresh a sum of Rs 75,000 within a period of four weeks from the date of this<br />

judgment. The Delhi Administration may take appropriate steps for recovery of the amount<br />

paid as compensation or part thereof from the officers who will be found responsible, if they<br />

are so advised. As the police officers are not parties before us, we state that any<br />

observation made by us in justification of this order shall not have any bearing in any<br />

proceedings specially criminal prosecution pending against the police officials in connection<br />

with the death of Naresh. The writ petitions are disposed of accordingly.<br />

29. In Re : Death of Sawinder Singh Grover, reported in 1992 (6) JT (SC) 271, the Supreme<br />

Court has ordered for compensation in a case where the facts and circumstances created a<br />

prima facie case for investigation and prosecution. In this case, the investigation was yet to<br />

be completed.<br />

“It is not disputed that the matter has not as yet been finally investigated. The learned<br />

Attorney-General assisting us in this case states that he does not accept the findings of the<br />

report and he reserves his right to challenge the same at the appropriate stage. We are of<br />

the view that the facts and circumstances which have now come to light create a prima facie<br />

case for investigation and prosecution. We, therefore, direct that all the persons named in<br />

the report of the learned Additional District Judge and others who are accused as a result of<br />

the investigation, be prosecuted for the appropriate offences under the law by the Central<br />

Bureau of Investigation. We direct the CBI to ensure that an FIR is registered on the facts as<br />

emanate from our order and the report of the learned Additional District Judge. A copy of the<br />

report along with all the annexures be sent to the Central Bureau of Investigation. As an<br />

interim measure by way of ex gratia payment, we direct that a sum of Rs 2,00,000 (two<br />

lakhs) shall be paid by the Union of India/Directorate of Enforcement to the widow of the<br />

deceased-Sawinder Singh. In the event a suit being filed for compensation, appropriate<br />

compensation may be determined in accordance with law after hearing the parties. The<br />

contentions of the learned Attorney-General which he wishes to place before us at this<br />

stage, should be reserved by him for an appropriate stage. In the event a decree to be<br />

passed, the sum of Rs 2,00,000 to be paid ex gratia, shall not be taken into account. The<br />

payment of rupees two lakhs shall be made within three months from today. The amount<br />

shall be deposited in the Registry of this Court and the widow of deceased-Sawinder Singh<br />

shall be at liberty to withdraw the entire amount on the identification to the satisfaction of the<br />

Registrar (Admn.). Any observation made by us in this order will not affect the investigation,<br />

prosecution and the trial. Notice is disposed of by us”.

30. In Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa, reported in (1993) 2 SCC 746, regarding the<br />

powers of the Court to grant compensation for deprivation of fundamental right, the Hon'ble<br />

Supreme Court held as follows:<br />

11. In Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar [(1983) 4 SCC 141], it was held that in a petition under<br />

Article 32 of the Constitution, this Court can grant compensation for deprivation of a<br />

fundamental right. That was a case of violation of the petitioner’s right to personal liberty<br />

under Article 21 of the Constitution. Chandrachud, CJ., dealing with this aspect, stated as<br />

under: (paras 9 and 10)<br />

“It is true that Article 32 cannot be used as a substitute for the enforcement of rights and<br />

obligations which can be enforced efficaciously through the ordinary processes of courts,<br />

civil and criminal. A money claim has therefore to be agitated in and adjudicated upon in a<br />

suit instituted in a court of lowest grade competent to try it. But the important question for<br />

our consideration is whether in the exercise of its jurisdiction under Article 32, this Court can<br />

pass an order for the payment of money if such an order is in the nature of compensation<br />

consequential upon the deprivation of a fundamental right. The instant case is illustrative of<br />

such cases ....<br />

... The petitioner could have been relegated to the ordinary remedy of a suit if his claim to<br />

compensation was factually controversial, in the sense that a civil court may or may not<br />

have upheld his claim. But we have no doubt that if the petitioner files a suit to recover<br />

damages for his illegal detention, a decree for damages would have to be passed in that<br />

suit, though it is not possible to predicate, in the absence of evidence, the precise amount<br />

which would be decreed in his favour. In these circumstances, the refusal of this Court to<br />

pass an order of compensation in favour of the petitioner will be doing mere lip-service to his<br />

fundamental right to liberty which the State Government has so grossly violated. Article 21<br />

which guarantees the right to life and liberty will be denuded of its significant content if the<br />

power of this Court were limited to passing orders to release from illegal detention. One of<br />

the telling ways in which the violation of that right can reasonably be prevented and due<br />

compliance with the mandate of Article 21 secured, is to mulct its violators in the payment of<br />

monetary compensation. Administrative sclerosis leading to flagrant infringements of<br />

fundamental rights cannot be corrected by any other method open to the judiciary to adopt.<br />

The right to compensation is some palliative for the unlawful acts of instrumentalities which

act in the name of public interest and which present for their protection the powers of the<br />

State as a shield. If civilisation is not to perish in this country as it has perished in some<br />

others too well known to suffer mention, it is necessary to educate ourselves into accepting<br />

that, respect for the rights of individuals is the true bastion of democracy. Therefore, the<br />

State must repair the damage done by its officers to the petitioner’s rights. It may have<br />

recourse against those officers.”<br />

15. The decision of Privy Council in Maharaj v. Attorney-General of Trinidad and Tobago<br />

(No. 2) [(1978) 2 All.ER 670] is useful in this context. That case related to Section 6 of the<br />

Constitution of Trinidad and Tobago 1962, in the chapter pertaining to human rights and<br />

fundamental freedoms, wherein Section 6 provided for an application to the High Court for<br />

redress. The question was, whether the provision permitted an order for monetary<br />

compensation. The contention of the Attorney General therein, that an order for payment of<br />

compensation did not amount to the enforcement of the rights that had been contravened,<br />

was expressly rejected. It was held, that an order for payment of compensation, when a right<br />

protected had been contravened, is clearly a form of ‘redress’ which a person is entitled to<br />

claim under Section 6, and may well be ‘the only practicable form of redress’. Lord Diplock<br />

who delivered the majority opinion, at page 679, stated:<br />

“It was argued on behalf of the Attorney General that Section 6(2) does not permit of an<br />

order for monetary compensation despite the fact that this kind of redress was ordered in<br />

Jaundoo v. Attorney General of Guyana [(1971) AC 972 : (1971) 3 WLR 13]. Reliance was<br />

placed on the reference in the sub-section to ‘enforcing, or securing the enforcement of, any<br />

of the provisions of the said foregoing sections’ as the purpose for which orders etc. could<br />

be made. An order for payment of compensation, it was submitted, did not amount to the<br />

enforcement of the rights that had been contravened. In their Lordships’ view an order for<br />

payment of compensation when a right protected under Section 1 ‘has been’ contravened is<br />

clearly a form of ‘redress’ which a person is entitled to claim under Section 6(1) and may<br />

well be the only practicable form of redress, as by now it is in the instant case. The<br />

jurisdiction to make such an order is conferred on the High Court by para (a) of Section 6(2),<br />

viz. jurisdiction ‘to hear and determine any application made by any person in pursuance of<br />

sub-section (1) of this section’. The very wide powers to make orders, issue writs and give<br />

directions are ancillary to this.”<br />

Lord Diplock further stated at page 680, as under:

“Finally, their Lordships would say something about the measure of monetary compensation<br />

recoverable under Section 6 where the contravention of the claimant’s constitutional rights<br />

consists of deprivation of liberty otherwise than by due process of law. The claim is not a<br />

claim in private law for damages for the tort of false imprisonment, under which the<br />

damages recoverable are at large and would include damages for loss of reputation. It is a<br />

claim in public law for compensation for deprivation of liberty alone.”<br />

20. We respectfully concur with the view that the court is not helpless and the wide powers<br />

given to this Court by Article 32, which itself is a fundamental right, imposes a constitutional<br />

obligation on this Court to forge such new tools, which may be necessary for doing complete<br />

justice and enforcing the fundamental rights guaranteed in the Constitution, which enable<br />

the award of monetary compensation in appropriate cases, where that is the only mode of<br />

redress available. The power available to this Court under Article 142 is also an enabling<br />

provision in this behalf. The contrary view would not merely render the court powerless and<br />

the constitutional guarantee a mirage, but may, in certain situations, be an incentive to<br />

extinguish life, if for the extreme contravention the court is powerless to grant any relief<br />

against the State, except by punishment of the wrongdoer for the resulting offence, and<br />

recovery of damages under private law, by the ordinary process. If the guarantee that<br />

deprivation of life and personal liberty cannot be made except in accordance with law, is to<br />

be real, the enforcement of the right in case of every contravention must also be possible in<br />

the constitutional scheme, the mode of redress being that which is appropriate in the facts of<br />

each case. This remedy in public law has to be more readily available when invoked by the<br />

have-nots, who are not possessed of the wherewithal for enforcement of their rights in<br />

private law, even though its exercise is to be tempered by judicial restraint to avoid<br />

circumvention of private law remedies, where more appropriate.<br />

29. Verma, J., while dealing with the first question i.e. whether it was a case of custodial<br />

death, has referred to the evidence and the circumstances of the case as also the stand<br />

taken by the State about the manner in which injuries were caused and has come to the<br />

conclusion that the case put up by the police of the alleged escape of Suman Behera from<br />

police custody and his sustaining the injuries in a train accident was not acceptable. I<br />

respectfully agree. A strenuous effort was made by the learned Additional Solicitor General<br />

by reference to the injuries on the head and the face of the deceased to urge that those<br />

injuries could not be possible by the alleged police torture and the finding recorded by the

District Judge in his report to the contrary was erroneous. It was urged on behalf of the State<br />

that the medical evidence did establish that the injuries had been caused to the deceased<br />

by lathi blows but it was asserted that the nature of injuries on the face and left temporal<br />

region could not have been caused by the lathis and, therefore, the death had occurred in<br />

the manner suggested by the police in a train accident and that it was not caused by the<br />

police while the deceased was in their custody. In this connection, it would suffice to notice<br />

that the doctor, who conducted the post-mortem examination, excluded the possibility of the<br />

injuries to Suman Behera being caused in a train accident. The injuries on the face and the<br />

left temporal region were found to be post-mortem injuries while the rest were ante-mortem.<br />

This aspect of the medical evidence would go to show that after inflicting other injuries,<br />

which resulted in the death of Suman Behera, the police with a view to cover up their crime<br />

threw the body on the rail-track and the injuries on the face and left temporal region were<br />

received by the deceased after he had died. This aspect further exposes not only the<br />

barbaric attitude of the police but also its crude attempt to fabricate false clues and create<br />

false evidence with a view to screen its offence. The falsity of the claim of escape stands<br />

also exposed by the report from the Regional Forensic Science Laboratory dated March 11,<br />

1988 (Annexure R-8) which mentions that the two pieces of rope sent for examination to it,<br />

did not tally in respect of physical appearance, thereby belying the police case that the<br />

deceased escaped from the police custody by chewing the rope. The theory of escape has,<br />

thus, been rightly disbelieved and I agree with the view of Brother Verma, J. that the death<br />

of Suman Behera was caused while he was in custody of the police by police torture. A<br />

custodial death is perhaps one of the worst crimes in a civilised society governed by the rule<br />

of law. It is not our concern at this stage, however, to determine as to which police officer or<br />

officers were responsible for the torture and ultimately the death of Suman Behera. That is a<br />

matter which shall have to be decided by the competent court. I respectfully agree with the<br />

directions given to the State by Brother Verma,J in this behalf.<br />

30. On basis of the above conclusion, we have now to examine whether to seek the right of<br />

redressal under Article 32 of the Constitution, which is without prejudice to any other action<br />

with respect to the same matter which may be lawfully available, extends merely to a<br />

declaration that there has been contravention and infringement of the guaranteed<br />

fundamental rights and rest content at that by relegating the party to seek relief through civil<br />

and criminal proceedings or can it go further and grant redress also by the only practicable<br />

form of redress — by awarding monetary damages for the infraction of the right to life.

31. It is axiomatic that convicts, prisoners or undertrials are not denuded of their<br />

fundamental rights under Article 21 and it is only such restrictions, as are permitted by law,<br />

which can be imposed on the enjoyment of the fundamental right by such persons. It is an<br />

obligation of the State to ensure that there is no infringement of the indefeasible rights of a<br />

citizen to life, except in accordance with law, while the citizen is in its custody. The precious<br />

right guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution of India cannot be denied to convicts,<br />

undertrials or other prisoners in custody, except according to procedure established by law.<br />

There is a great responsibility on the police or prison authorities to ensure that the citizen in<br />

its custody is not deprived of his right to life. His liberty is in the very nature of things<br />

circumscribed by the very fact of his confinement and therefore his interest in the limited<br />

liberty left to him is rather precious. The duty of care on the part of the State is strict and<br />

admits of no exceptions. The wrongdoer is accountable and the State is responsible if the<br />

person in custody of the police is deprived of his life except according to the procedure<br />

established by law. I agree with Brother Verma, J. that the defence of “sovereign immunity”<br />

in such cases is not available to the State and in fairness to Mr Altaf Ahmed it may be<br />

recorded that he raised no such defence either.<br />

32. Adverting to the grant of relief to the heirs of a victim of custodial death for the infraction<br />

or invasion of his rights guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, it is not<br />

always enough to relegate him to the ordinary remedy of a civil suit to claim damages for the<br />

tortious act of the State as that remedy in private law indeed is available to the aggrieved<br />

party. The citizen complaining of the infringement of the indefeasible right under Article 21 of<br />

the Constitution cannot be told that for the established violation of the fundamental right to<br />

life, he cannot get any relief under the public law by the courts exercising writ jurisdiction.<br />

The primary source of the public law proceedings stems from the prerogative writs and the<br />

courts have, therefore, to evolve ‘new tools’ to give relief in public law by moulding it<br />

according to the situation with a view to preserve and protect the Rule of Law. While<br />

concluding his first Hamlyn Lecture in 1949 under the title “Freedom under the Law” Lord<br />

Denning in his own style warned:<br />

“No one can suppose that the executive will never be guilty of the sins that are common to<br />

all of us. You may be sure that they will sometimes do things which they ought not to do:<br />

and will not do things that they ought to do. But if and when wrongs are thereby suffered by<br />

any of us what is the remedy? Our procedure for securing our personal freedom is efficient,<br />

our procedure for preventing the abuse of power is not. Just as the pick and shovel is no

longer suitable for the winning of coal, so also the procedure of mandamus, certiorari, and<br />

actions on the case are not suitable for the winning of freedom in the new age. They must<br />

be replaced by new and up-to date machinery, by declarations, injunctions and actions for<br />

negligence.... This is not the task for Parliament ... the courts must do this. Of all the great<br />

tasks that lie ahead this is the greatest. Properly exercised the new powers of the executive<br />

lead to the welfare state; but abused they lead to a totalitarian state. None such must ever<br />

be allowed in this country.”<br />

33. The old doctrine of only relegating the aggrieved to the remedies available in civil law<br />

limits the role of the courts too much as protector and guarantor of the indefeasible rights of<br />

the citizens. The courts have the obligation to satisfy the social aspirations of the citizens<br />

because the courts and the law are for the people and expected to respond to their<br />

aspirations.<br />

34. The public law proceedings serve a different purpose than the private law proceedings.<br />

The relief of monetary compensation, as exemplary damages, in proceedings under Article<br />

32 by this Court or under Article 226 by the High Courts, for established infringement of the<br />

indefeasible right guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution is a remedy available in<br />

public law and is based on the strict liability for contravention of the guaranteed basic and<br />

indefeasible rights of the citizen. The purpose of public law is not only to civilize public<br />

power but also to assure the citizen that they live under a legal system which aims to protect<br />

their interests and preserve their rights. Therefore, when the court moulds the relief by<br />

granting “compensation” in proceedings under Article 32 or 226 of the Constitution seeking<br />

enforcement or protection of fundamental rights, it does so under the public law by way of<br />

penalising the wrongdoer and fixing the liability for the public wrong on the State which has<br />

failed in its public duty to protect the fundamental rights of the citizen. The payment of<br />

compensation in such cases is not to be understood, as it is generally understood in a civil<br />

action for damages under the private law but in the broader sense of providing relief by an<br />

order of making ‘monetary amends’ under the public law for the wrong done due to breach<br />

of public duty, of not protecting the fundamental rights of the citizen. The compensation is in<br />

the nature of ‘exemplary damages’ awarded against the wrongdoer for the breach of its<br />

public law duty and is independent of the rights available to the aggrieved party to claim<br />

compensation under the private law in an action based on tort, through a suit instituted in a<br />

court of competent jurisdiction or/and prosecute the offender under the penal law.

35. This Court and the High Courts, being the protectors of the civil liberties of the citizen,<br />

have not only the power and jurisdiction but also an obligation to grant relief in exercise of<br />

its jurisdiction under Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution to the victim or the heir of the<br />

victim whose fundamental rights under Article 21 of the Constitution of India are established<br />

to have been flagrantly infringed by calling upon the State to repair the damage done by its<br />

officers to the fundamental rights of the citizen, notwithstanding the right of the citizen to the<br />

remedy by way of a civil suit or criminal proceedings. The State, of course has the right to<br />

be indemnified by and take such action as may be available to it against the wrongdoer in<br />

accordance with law — through appropriate proceedings. Of course, relief in exercise of the<br />

power under Article 32 or 226 would be granted only once it is established that there has<br />

been an infringement of the fundamental rights of the citizen and no other form of<br />

appropriate redressal by the court in the facts and circumstances of the case, is possible.<br />

The decisions of this Court in the line of cases starting with Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar,<br />

reported in (1983) 4 SCC 141 granted monetary relief to the victims for deprivation of their<br />

fundamental rights in proceedings through petitions filed under Article 32 or 226 of the<br />

Constitution of India, notwithstanding the rights available under the civil law to the aggrieved<br />

party where the courts found that grant of such relief was warranted. It is a sound policy to<br />

punish the wrongdoer and it is in that spirit that the courts have moulded the relief by<br />

granting compensation to the victims in exercise of their writ jurisdiction. In doing so the<br />

courts take into account not only the interest of the applicant and the respondent but also<br />

the interests of the public as a whole with a view to ensure that public bodies or officials do<br />

not act unlawfully and do perform their public duties properly particularly where the<br />

fundamental right of a citizen under Article 21 is concerned. Law is in the process of<br />

development and the process necessitates developing separate public law procedures as<br />

also public law principles. It may be necessary to identify the situations to which separate<br />

proceedings and principles apply and the courts have to act firmly but with certain amount of<br />

circumspection and self-restraint, lest proceedings under Article 32 or 226 are misused as a<br />

disguised substitute for civil action in private law. Some of those situations have been<br />

identified by this Court in the cases referred to by Brother Verma, J”.<br />

31. In R.Parvathi, v. State of Tamil Nadu reported in (ILR. (1994) 3 Madras, 813), the<br />

petitioner therein sought for compensation of Rs.5 Lakhs for the death of her husband, at<br />

the hands of the Police. The Court at paragraph 17 held as follows:<br />

“Petitioner herein has asked for compensation for herself in a sum of Rs. 5 Lakhs for what

she has been made to suffer, the sufferings of her husband her two sons and her brother-inlaw.<br />

Instead of the body of the petitioner's husband alive, brought before the Court, the<br />

information received is that he has been done to death by the fourth respondent and his<br />

men. In Padmini's case (1993) Writ L.R. 798) the Court has gone into the circumstances<br />

under which the Court exercises power under Article 226 of the Constitution and grants<br />

compensation subject to the right of the person aggrieved to seek further compensation in a<br />

properly constituted suit. After the <strong>Judgment</strong> in Padmini's Case, the Supreme Court has<br />

stated in the case of custodial death in Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa (A.I.R. 1993 S.C.<br />

1960) that when a claim for monetary compensation is made, the Court has an obligation to<br />

grant the relief and defence of sovereign immunity is not available to the State Agency. In<br />

the words of the Supreme Court,<br />

“A claim in public law for compensation for contravention of human rights and fundamental<br />

freedoms the protection of which is guaranteed in the Constitution is an acknowledged<br />

remedy for enforcement and protection of such rights, and such a claim based on strict<br />

liability made by resorting to a Constitutional remedy provided for the enforcement of a<br />

fundamental right is distinct from and in addition to, the remedy in private law for damages<br />

for the tort resulting from the contravention of the fundamental right”.<br />

The Power under Articles 32 and 226 is exercised not as a remedy available only in cases<br />

of damages that affect any individual but of damages which cause serious injury to the<br />

society and when policemen are found to have acted in contravention of law, their offence is<br />

more serious than that of any layman”.<br />

32. In Inder Singh Vs. State of Punjab and others reported in 1995 (3) SCC 702, the<br />

Supreme Court while considering the violation of human rights, abduction and elimination of<br />

seven persons, by a police party led by Deputy Superintendent of Police, held as follows:<br />

“9. The Punjab Police would appear to have forgotten that it was a police force and that the<br />

primary duty of those in uniform is to uphold law and order and protect the citizen. If<br />

members of a police force resort to illegal abduction and assassination, if other members of<br />

that police force do not record and investigate complaints in this behalf for long periods of<br />

time, if those who had been abducted are found to have been unlawfully detained in police<br />

stations in the State concerned prior to their probable assassination, the case is not one of<br />

errant behaviour by a few members of that police force. We do not see that “constitutional<br />

culture” as Mr Tulsi put it, had percolated to the Punjab Police. On the contrary it betrays

scant respect for the life and liberty of innocent citizens and exposes the willingness of<br />

others in uniform to lend a helping hand to one who wreaks private vengeance on mere<br />

suspicion.<br />

10. This Court has in recent times come across far too many instances where the police<br />

have acted not to uphold the law and protect the citizen but in aid of a private cause and to<br />

oppress the citizen. It is a trend that bodes ill for the country and it must be promptly<br />

checked. We would expect the DGP, Punjab, to take a serious view in such cases if he is<br />

minded to protect the image of the police force which he is heading. He can ill-afford to shut<br />

his eyes to the nose-dive that it is taking with such ghastly incidents surfacing at regular<br />

intervals. Nor can the Home Department of the Central Government afford to appear to be a<br />

helpless silent spectator”.<br />

33. In State of M.P Vs. Shyamsunder Trivedi reported in 1995 (4) SCC 262, the Hon'ble<br />

Supreme Court considered the case of custodial death or police torture, the availability of<br />

direct ocular evidence of the complicity of the police personnel and the ground reality in<br />

such matters where the police personnel, would remain silent and more often than not even<br />

pervert the truth to save their colleagues and at paragraph Nos.16 and 17 observed as<br />

follows:<br />

“16. Indeed, there is no evidence to show that after Ganniuddin, Respondent 5, who along<br />

with Rajaram, Respondent 4, had brought the deceased to the police station for<br />

interrogation, had at any time left the police station on the fateful night. In the face of the<br />

unimpeachable evidence of PW 4 and PW 8, we fail to understand how the learned Judges<br />

of the High Court could opine that there was no definite evidence to show the complicity of<br />

Ram Naresh Shukla, Respondent 3, Rajaram and Ganniuddin, Respondents 4 and 5<br />

respectively in the crime along with SI Trivedi, Respondent 1. The observations of the High<br />

Court that the presence and participation of these respondents in the crime is doubtful are<br />

not borne out from the evidence on the record and appear to be an unrealistic over<br />

simplification of the tell-tale circumstances established by the prosecution. The following<br />

pieces of circumstantial evidence apart from the other evidence on record, viz., (i) that the<br />

deceased had been brought alive to the police station and was last seen alive there on 13-<br />

10-1981; (ii) that the dead body of the deceased was taken out of the police station on 14-<br />

10-1981 at about 2 p.m. for being removed to the hospital; (iii) that the deceased had died<br />

as a result of the receipt of extensive injuries while he was at the police station; (iv) that SI

Trivedi, Respondent 1, Ram Naresh Shukla, Respondent 3, Rajaram, Respondent 4 and<br />

Ganniuddin, Respondent 5 were present at the police station and had all joined hands to<br />

dispose of the dead body of Nathu Banjara; (v) that SI Trivedi, Respondent 1 created false<br />

evidence and fabricated false clues in the shape of documentary evidence with a view to<br />

screen the offence and for that matter, the offender; (vi) SI Trivedi — respondent in<br />

connivance with some of his subordinates, respondents herein had taken steps to cremate<br />

the dead body in hot haste describing the deceased as a ‘lavaris’; (vii) Rajaram and<br />

Ganniuddin — respondents, had brought the deceased to the police station from his village,<br />

and (viii) that police record did not show that either Rajaram or Ganniuddin had left the<br />

police station, till the dead body was removed to the hospital in the jeep, unerringly point<br />

towards the guilt of the accused and the established circumstances coupled with the direct<br />

evidence of PWs 1, 3, 4, 8 and 18 are consistent only with the hypothesis of the guilt of the<br />

respondents and are inconsistent with their innocence. So far as Respondent 2, Ram Partap<br />

Mishra is concerned, however, no clinching or satisfactory evidence is available on the<br />

record to establish his presence at the police station when Nathu deceased was being<br />

subjected to extensive beating or of his participation in the commission of the crime. The<br />

High Court erroneously overlooked the ground reality that rarely in cases of police torture or<br />

custodial death, direct ocular evidence of the complicity of the police personnel would be<br />

available, when it observed that ‘direct’ evidence about the complicity of these respondents<br />

was not available. Generally speaking, it would be police officials alone who can only<br />

explain the circumstances in which a person in their custody had died. Bound as they are by<br />

the ties of brotherhood, it is not unknown that the police personnel prefer to remain silent<br />

and more often than not even pervert the truth to save their colleagues, and the present<br />

case is an apt illustration, as to how one after the other police witnesses feigned ignorance<br />

about the whole matter.<br />

17. From our independent analysis of the materials on the record, we are satisfied that<br />

Respondents 1 and 3 to 5 were definitely present at the police station and were directly or<br />

indirectly involved in the torture of Nathu Banjara and his subsequent death while in the<br />

police custody as also in making attempts to screen the offence to enable the guilty to<br />

escape punishment. The trial court and the High Court, if we may say so with respect,<br />

exhibited a total lack of sensitivity and a “could not care less” attitude in appreciating the<br />

evidence on the record and thereby condoning the barbarous third degree methods which<br />

are still being used at some police stations, despite being illegal. The exaggerated<br />

adherence to and insistence upon the establishment of proof beyond every reasonable

doubt, by the prosecution, ignoring the ground realities, the fact-situations and the peculiar<br />

circumstances of a given case, as in the present case, often results in miscarriage of justice<br />

and makes the justice delivery system a suspect. In the ultimate analysis the society suffers<br />

and a criminal gets encouraged. Tortures in police custody, which of late are on the<br />

increase, receive encouragement by this type of an unrealistic approach of the courts<br />

because it reinforces the belief in the mind of the police that no harm would come to them, if<br />

an odd prisoner dies in the lock-up, because there would hardly be any evidence available<br />

to the prosecution to directly implicate them with the torture. The courts must not lose sight<br />

of the fact that death in police custody is perhaps one of the worst kind of crimes in a<br />

civilised society, governed by the rule of law and poses a serious threat to an orderly<br />

civilised society. Torture in custody flouts the basic rights of the citizens recognised by the<br />

Indian Constitution and is an affront to human dignity. Police excesses and the maltreatment<br />

of detainees/undertrial prisoners or suspects tarnishes the image of any civilised nation and<br />

encourages the men in ‘Khaki’ to consider themselves to be above the law and sometimes<br />

even to become law unto themselves. Unless stern measures are taken to check the<br />

malady, the foundations of the criminal justice delivery system would be shaken and the<br />

civilization itself would risk the consequence of heading towards perishing. The courts must,<br />

therefore, deal with such cases in a realistic manner and with the sensitivity which they<br />

deserve, otherwise the common man may lose faith in the judiciary itself, which will be a sad<br />

day.<br />

34. In a decision of Punjab & Haryana High Court Bar Association v. State of Punjab and<br />

others reported in 1996 (4) SCC 741, an advocate, his wife and minor child were abducted<br />

and murdered. It was alleged that certain police officials were involved in that crime. The<br />

Supreme Court directed the Central Bureau of Investigation to investigate into the<br />

mysterious, abduction and alleged murder of Kulwant Singh, Advocate, his wife and their<br />

two years old child. The CBI submitted their final report. The Supreme Court, after<br />

considering the record, found that there was sufficient material to prosecute the police<br />

officers for abduction and murder of the abovesaid persons and accordingly, directed the<br />

Home Secretary, State of Punjab to take appropriate action. On the question of awarding<br />

compensation, following the <strong>Judgment</strong> in Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa reported in 1993<br />

(2) SCC 746, the Supreme Court directed the Punjab Government through Secretary to the<br />

Government, Home Department to pay a sum of Rs.10,00,000/- (ten lakhs) to the parents<br />

(father and mother) of the claimant, as compensation within two months from the date of<br />

receipt of a copy of that order.

35. In P.Amaravathy Vs. The Government of Tamil Nadu & 10 others reported in 1996 (2)<br />

CTC 478, where the petitioner's husband died in police custody. She sought for a<br />

Mandamus directing the official respondents therein, to register a case against private<br />

respondents 5 to 10 and hand over the investigation to CBI and also for a direction to the<br />

first respondent therein, to pay a sum of Rs.20 lakhs, by way of compensation, for the<br />

custodial death of her husband. Taking note of the circumstances of the case, this Court<br />

ordered compensation of Rs.1,00,000/- by way of interim compensation to be adjusted at a<br />

later stage when regular compensation is claimed.<br />

36. In the historical judgment of D.K.Basu v. State of West Bengal reported in AIR 1997<br />

SCW 610, after enumerating the rights of an accused/detenue and on the aspect of dealing<br />

with custodial death, the Supreme Court, at paragraphs 22, 36, 37 and 39 has held as<br />

follows:<br />

"22. Custodial death is perhaps one of the worst crimes in a civilised society governed by<br />

the rule of law. The rights inherent in Articles 21 and 22(1) of the Constitution require to be<br />

jealously and scrupulously protected. We cannot wish away the problem. Any form of torture<br />

or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment would fall within the inhibition of Article 21 of the<br />

Constitution, whether it occurs during investigation, interrogation or otherwise. If the<br />

functionaries of the Government become law-breakers, it is bound to breed contempt for law<br />

and would encourage lawlessness and every man would have the tendency to become law<br />

unto himself thereby leading to anarchanism. No civilised nation can permit that to happen.<br />

Does a citizen shed off his fundamental right to life, the moment a policeman arrests him?<br />

Can the right to life of a citizen be put in abeyance on his arrest? These questions touch the<br />

spinal cord of human rights’ jurisprudence. The answer, indeed, has to be an emphatic “No”.<br />

The precious right guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution of India cannot be denied to<br />

convicts, undertrials, detenus and other prisoners in custody, except according to the<br />

procedure established by law by placing such reasonable restrictions as are permitted by<br />

law.<br />

36. Failure to comply with the requirements hereinabove mentioned shall apart from<br />

rendering the official concerned liable for departmental action, also render him liable to be<br />

punished for contempt of court and the proceedings for contempt of court may be instituted<br />

in any High Court of the country, having territorial jurisdiction over the matter.

37. The requirements, referred to above flow from Articles 21 and 22(1) of the Constitution<br />

and need to be strictly followed. These would apply with equal force to the other<br />

governmental agencies also to which a reference has been made earlier.<br />

39. The requirements mentioned above shall be forwarded to the Director General of Police<br />

and the Home Secretary of every State/Union Territory and it shall be their obligation to<br />

circulate the same to every police station under their charge and get the same notified at<br />

every police station at a conspicuous place. It would also be useful and serve larger interest<br />

to broadcast the requirements on All India Radio besides being shown on the National<br />

Network of Doordarshan any by publishing and distributing pamphlets in the local language<br />

containing these requirements for information of the general public. Creating awareness<br />

about the rights of the arrestee would in our opinion be a step in the right direction to<br />

combat the evil of custodial crime and bring in transparency and accountability. It is hoped<br />

that these requirements would help to curb, if not totally eliminate, the use of questionable<br />

methods during interrogation and investigation leading to custodial commission of crimes.”<br />

37. In a decision of Murti Devi v. State of Delhi and others reported in JT 1998 (9) SC 48 =<br />

1998 (9) SCC 604, a compensation was claimed for the death of an undertrial prisoner, who<br />

was kept in judicial custody in Tihar jail and seriously assaulted inside the jail and on<br />

account of the injuries, he died after being admitted in Delhi hospital. Holding that it was the<br />

bounden duty of the jail authorities to protect the life of an undertrial prisoner lodged in the<br />

jail, the Supreme Court directed the respondents therein to pay a sum of Rs.2,50,000/- to<br />

the writ petitioner therein and further directed that out of the said sum Rs.2,00,000/- should<br />

be made in Fixed Deposit in the name of the claimant in a Nationalised Bank for a period of<br />

five years and the balance sum of Rs.50,000/- should be handed over to the claimant.<br />

38. In Chairman, Rly. Board v. Chandrima Das, reported in (2000) 2 SCC 465, the Hon'ble<br />

Apex Court considered a Public Interest Litigation by an advocate seeking compensation to<br />

a foreigner who was gang raped by railway employees. While answering the maintainability<br />

of the writ petition seeking compensation and upholding that the right to life is available not<br />

only to every citizen of this country, but also to a person, who is not a citizen, the Hon'ble<br />

Supreme Court held as follows:<br />

“9. Various aspects of the public law field were considered. It was found that though initially

a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution relating to contractual matters was held not to<br />

lie, the law underwent a change by subsequent decisions and it was noticed that even<br />

though the petition may relate essentially to a contractual matter, it would still be amenable<br />

to the writ jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226. The public law remedies have<br />

also been extended to the realm of tort. This Court, in its various decisions, has entertained<br />

petitions under Article 32 of the Constitution on a number of occasions and has awarded<br />

compensation to the petitioners who had suffered personal injuries at the hands of the<br />

officers of the Government. The causing of injuries, which amounted to tortious act, was<br />

compensated by this Court in many of its decisions beginning from Rudul Sah v. State of<br />

Bihar [(1983) 4 SCC 141] (See also Bhim Singh v. State of J&K [1985 (4) SCC 577],<br />

Peoples’ Union for Democratic Rights v. State of Bihar [1987 (1) SCC 265], Peoples’ Union<br />

for Democratic Rights v. Police Commr., Delhi Police Headquarters [1989 (4) SCC 730],<br />

Saheli, A Women’s Resources Centre v. Commr. of Police [1990 (1) SCC 422], Arvinder<br />

Singh Bagga v. State of U.P [1994 (6) SCC 565], P. Rathinam v. Union of India [1989 Supp.<br />

(2) SCC 716], Death of Sawinder Singh Grower In re [1995 Supp. (4) SCC 450], Inder Singh<br />

v. State of Punjab [1995 (3) SCC 702 and D.K. Basu v. State of W.B. [1997 (6) SCC 370])<br />

10. In cases relating to custodial deaths and those relating to medical negligence, this Court<br />

awarded compensation under the public law domain in Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa<br />

[1993 (2) SCC 746], State of M.P. v. Shyamsunder Trivedi [1995 (4) SCC 262], People’s<br />

Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India [1997 (3) SCC 433] and Kaushalya v. State of<br />

Punjab [1999 (6) SCC 754], Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee v. State of Bihar [1991 (3)<br />

SCC 482], Jacob George (Dr) v. State of Kerala[1994 (3) SCC 430], Paschim Banga Khet<br />

Mazdoor Samity v. State of W.B. [1996 (4) SCC 37] and Manju Bhatia v. New Delhi<br />

Municipal Council [1997 (6) SCC 370].<br />

11. Having regard to what has been stated above, the contention that Smt Hanuffa Khatoon<br />

should have approached the civil court for damages and the matter should not have been<br />

considered in a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution, cannot be accepted. Where<br />

public functionaries are involved and the matter relates to the violation of fundamental rights<br />

or the enforcement of public duties, the remedy would still be available under the public law<br />

notwithstanding that a suit could be filed for damages under private law.<br />

12. In the instant case, it is not a mere matter of violation of an ordinary right of a person but<br />

the violation of fundamental rights which is involved. Smt Hanuffa Khatoon was a victim of

ape. This Court in Bodhisattwa Gautam v. Subhra Chakraborty [1996 (1) SCC 490] has<br />