Check out the handout for great essay writing

Check out the handout for great essay writing

Check out the handout for great essay writing

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Essays<br />

A quick guide<br />

Essays are a part of almost every degree program. While<br />

you probably won’t write an <strong>essay</strong> when you become a<br />

professional, <strong>the</strong> skills needed in good <strong>essay</strong> <strong>writing</strong> are<br />

very relevant to o<strong>the</strong>r academic tasks. These skills—<br />

researching, analysing, applying, syn<strong>the</strong>sising and<br />

evaluating—can also be transferred to any professional<br />

situation which requires you to respond critically and<br />

creatively to a problem or issue.<br />

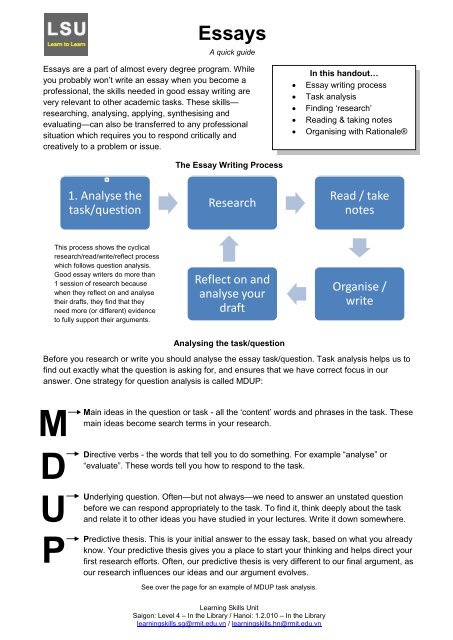

The Essay Writing Process<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

In this hand<strong>out</strong>…<br />

Essay <strong>writing</strong> process<br />

Task analysis<br />

Finding ‘research’<br />

Reading & taking notes<br />

Organising with Rationale®<br />

1. Analyse <strong>the</strong><br />

task/question<br />

Research<br />

Read / take<br />

notes<br />

This process shows <strong>the</strong> cyclical<br />

research/read/write/reflect process<br />

which follows question analysis.<br />

Good <strong>essay</strong> writers do more than<br />

1 session of research because<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y reflect on and analyse<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir drafts, <strong>the</strong>y find that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

need more (or different) evidence<br />

to fully support <strong>the</strong>ir arguments.<br />

Reflect on and<br />

analyse your<br />

draft<br />

Organise /<br />

write<br />

Analysing <strong>the</strong> task/question<br />

Be<strong>for</strong>e you research or write you should analyse <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> task/question. Task analysis helps us to<br />

find <strong>out</strong> exactly what <strong>the</strong> question is asking <strong>for</strong>, and ensures that we have correct focus in our<br />

answer. One strategy <strong>for</strong> question analysis is called MDUP:<br />

M<br />

Main ideas in <strong>the</strong> question or task - all <strong>the</strong> ‘content’ words and phrases in <strong>the</strong> task. These<br />

main ideas become search terms in your research.<br />

D<br />

Directive verbs - <strong>the</strong> words that tell you to do something. For example “analyse” or<br />

“evaluate”. These words tell you how to respond to <strong>the</strong> task.<br />

U<br />

P<br />

Underlying question. Often—but not always—we need to answer an unstated question<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e we can respond appropriately to <strong>the</strong> task. To find it, think deeply ab<strong>out</strong> <strong>the</strong> task<br />

and relate it to o<strong>the</strong>r ideas you have studied in your lectures. Write it down somewhere.<br />

Predictive <strong>the</strong>sis. This is your initial answer to <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> task, based on what you already<br />

know. Your predictive <strong>the</strong>sis gives you a place to start your thinking and helps direct your<br />

first research ef<strong>for</strong>ts. Often, our predictive <strong>the</strong>sis is very different to our final argument, as<br />

our research influences our ideas and our argument evolves.<br />

See over <strong>the</strong> page <strong>for</strong> an example of MDUP task analysis.<br />

Learning Skills Unit<br />

Saigon: Level 4 – In <strong>the</strong> Library / Hanoi: 1.2.010 – In <strong>the</strong> Library<br />

learningskills.sg@rmit.edu.vn / learningskills.hn@rmit.edu.vn

Main Ideas: legally binding<br />

contracts, mere agreements, legal<br />

consequences, case illustrations,<br />

distinguish (differentiate)<br />

MDUP task analysis in action…<br />

Example <strong>essay</strong> task: Using case<br />

illustrations, explain how legally binding<br />

contracts are distinguished from mere<br />

agreements which have no legal<br />

consequences.<br />

Predictive <strong>the</strong>sis: Contracts are<br />

written, agreements are spoken. To<br />

protect <strong>the</strong>mselves, businesses<br />

should use contracts.<br />

Directive Words: explain… how<br />

= describe <strong>the</strong> process; using =<br />

apply cases to description;<br />

distinguish(ed) = show <strong>the</strong><br />

difference between<br />

Underlying question: What’s <strong>the</strong><br />

difference between contracts and<br />

agreements? What are <strong>the</strong><br />

implications of this <strong>for</strong> businesses?<br />

Researching<br />

The main ideas you identify in task analysis should guide your research. Of course books in <strong>the</strong><br />

library will be useful, but academic databases (Proquest, Emerald, Eric etc.) are <strong>great</strong> <strong>for</strong> finding <strong>the</strong><br />

most up-to-date, reliable and sophisticated in<strong>for</strong>mation relevant to your <strong>essay</strong> topics. You can find<br />

<strong>the</strong>se databases on <strong>the</strong> RMIT online library. Use <strong>the</strong> basic tips below to get started on <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Reading & Taking Notes<br />

Once you have books/articles/websites related to you <strong>essay</strong> topic, <strong>the</strong> challenge is to read those<br />

sources efficiently and effectively – you should find <strong>the</strong> most useful in<strong>for</strong>mation in <strong>the</strong> least amount<br />

of time. Follow <strong>the</strong> process below (Boddington & Clanchy 1999) <strong>for</strong> each source you’ve found.<br />

•Look at <strong>the</strong> title, sub<br />

titles, headings and<br />

contents pages<br />

•Find <strong>the</strong> most relevant<br />

sections<br />

1. Search<br />

2. Skim<br />

• Choose <strong>the</strong> paragraphs<br />

•Once you've found <strong>the</strong><br />

most relevant sections,<br />

skim over <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

focussing on <strong>the</strong><br />

introduction and topic<br />

sentences of paragraphs<br />

that provide <strong>the</strong><br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation you need<br />

3. Select<br />

4. Study<br />

•Read those paragraphs<br />

carefully and critically<br />

and take notes relevant<br />

to <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> topic.<br />

• Try to paraphrase<br />

Learning Skills Unit<br />

Saigon: Level 4 – In <strong>the</strong> Library / Hanoi: 1.2.010 – In <strong>the</strong> Library<br />

learningskills.sg@rmit.edu.vn / learningskills.hn@rmit.edu.vn

Organising <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> using Rationale® software<br />

This is <strong>the</strong> most important part of <strong>the</strong> process – it’s where you combine ideas from your research<br />

into a structured, logical and persuasive response to <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> task. Because those ideas in you’re<br />

your research can be complex, it’s often a good idea to organise <strong>the</strong>m visually so that <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between <strong>the</strong>m can be easier to find. One very powerful way of organising your ideas<br />

visually is to use <strong>the</strong> Rationale® argument mapping software, which is now available on <strong>the</strong> LSU<br />

computers. This easy-to-use software allows you to build a ‘tree’ of your answer—having a ‘picture’<br />

of <strong>the</strong> arguments and reasons can help you focus on <strong>the</strong> logic of your answer, which is <strong>the</strong> most<br />

important aspect of <strong>essay</strong> <strong>writing</strong>. The very basic argument map below gives an example of what<br />

Rationale® can do <strong>for</strong> you.<br />

‘because’ links ‘reasons’ and ‘support <strong>for</strong> reasons’,<br />

‘but’ links objections. Organisation at this level<br />

shows ideas to support or object to <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis<br />

statement. These can be seen as ‘main points’.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> map is <strong>the</strong><br />

‘contention’ – in an <strong>essay</strong>, this is<br />

called <strong>the</strong> ‘<strong>the</strong>sis statement’.<br />

Ideas at this level are more<br />

specific, and are used to support<br />

or object to <strong>the</strong> more general ideas<br />

above <strong>the</strong>m. Ideas here can be<br />

seen as ‘evidence’.<br />

Generating an argument map using Rationale® is surprisingly easy, and <strong>the</strong> Learning Skills<br />

Advisers in LSU can help you with it. Simply book a consultation and let us know that you want to<br />

map your argument with Rationale®. We’ll show how to do it, and we’ll help you reflect on <strong>the</strong> quality<br />

of your argument.<br />

Writing <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong><br />

Essays have 4 essential sections: <strong>the</strong> introduction, body, conclusion and reference list. After you<br />

know what your <strong>the</strong>sis statement is, try to write <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> in this order:<br />

First: Write <strong>the</strong> body, focussing on one paragraph at a time<br />

Second: Write <strong>the</strong> conclusion<br />

Last: Write <strong>the</strong> introduction, complete <strong>the</strong> reference list and proofread!<br />

Importantly, you should attend very carefully to in-text referencing in <strong>the</strong> first drafts of your <strong>essay</strong>s. If<br />

you don’t, it is possible that you will <strong>for</strong>get to correctly cite some ideas, and this could lead to<br />

concerns ab<strong>out</strong> plagiarism.<br />

Learning Skills Unit<br />

Saigon: Level 4 – In <strong>the</strong> Library / Hanoi: 1.2.010 – In <strong>the</strong> Library<br />

learningskills.sg@rmit.edu.vn / learningskills.hn@rmit.edu.vn

I. INTRODUCTION<br />

Sections of an <strong>essay</strong><br />

General statements - introduce <strong>the</strong> topic, <strong>the</strong> context and <strong>the</strong><br />

question/ issue/problem that <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> addresses<br />

Thesis statement – your 1- or 2-sentence argument in response<br />

<strong>the</strong> questions/issue/problem above<br />

Signpost – briefly describe how <strong>the</strong> body of <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> is<br />

organised<br />

The introduction should be one<br />

paragraph only, approximately<br />

10% of <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong>’s word limit.<br />

Avoid using expressions such<br />

as ‘nowadays’ and ‘all over <strong>the</strong><br />

world’, as <strong>the</strong>se are over used<br />

and lack sophistication.<br />

II. BODY<br />

Topic Sentence<br />

i. Support<br />

ii. Support<br />

iii. Support<br />

Link / summary sentence<br />

Topic Sentence<br />

i. Support<br />

ii. Support<br />

iii. Support<br />

Link / summary sentence<br />

Topic Sentence<br />

i. Support<br />

ii. Support<br />

iii. Support<br />

The number of body paragraphs<br />

is determined by <strong>the</strong> structure of<br />

your argument. Avoid very<br />

lengthy or very short paragraphs<br />

– try to keep each paragraph<br />

ab<strong>out</strong> <strong>the</strong> same length.<br />

The organisation of paragraphs<br />

in <strong>the</strong> body should show <strong>the</strong><br />

reader your analysis and<br />

reasoning. Your analysis breaks<br />

<strong>the</strong> main topic into smaller<br />

ideas, and your reasoning<br />

shows a logical relationship<br />

between <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Link / summary sentence<br />

etc.<br />

III. CONCLUSION<br />

Summarise main points / restate <strong>the</strong>sis statement<br />

Final comment – relate <strong>the</strong>sis statement to <strong>the</strong> wider context<br />

The conclusion is approximately<br />

5-10% of <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong>’s word limit.<br />

This is a place to restate your<br />

argument and main points. To<br />

create a good final comment,<br />

answer this question: “What are<br />

<strong>the</strong> implications of your<br />

argument being valid?”<br />

Summary<br />

Try not to think of <strong>essay</strong>s as something you simply ‘write’. Instead, try to see <strong>essay</strong>s as complex<br />

puzzles that take a lot of analysis, research, reading and thinking to respond to effectively. When<br />

generating and expressing your answer to <strong>the</strong> issue/question/problem in <strong>the</strong> <strong>essay</strong> task, always<br />

keep <strong>the</strong> audience (probably your lecturer) in my mind. If you can see your own <strong>essay</strong> from his or<br />

her perspective, you’ll be more able to meet <strong>the</strong>ir needs and expectations and more likely to do well.<br />

Learning Skills Unit<br />

Saigon: Level 4 – In <strong>the</strong> Library / Hanoi: 1.2.010 – In <strong>the</strong> Library<br />

learningskills.sg@rmit.edu.vn / learningskills.hn@rmit.edu.vn