Untitled - Saigontre

Untitled - Saigontre

Untitled - Saigontre

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

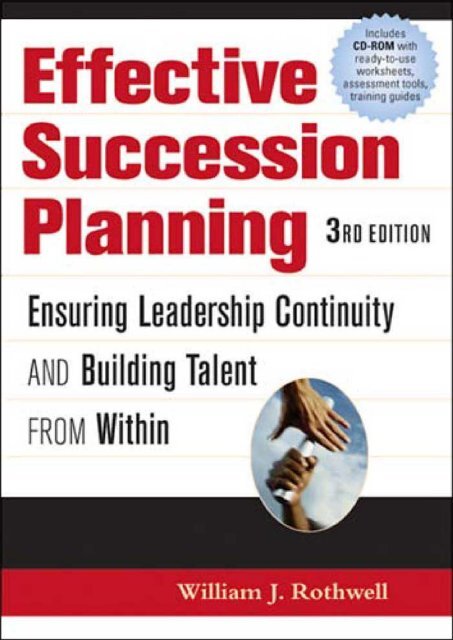

EFFECTIVE<br />

SUCCESSION<br />

PLANNING<br />

THIRD EDITION

This page intentionally left blank

EFFECTIVE<br />

SUCCESSION<br />

PLANNING<br />

THIRD EDITION<br />

Ensuring Leadership Continuity and<br />

Building Talent from Within<br />

William J. Rothwell<br />

American Management Association<br />

New York • Atlanta • Brussels • Chicago • Mexico City • San Francisco<br />

Shanghai • Tokyo • Toronto • Washington, D.C.

Special discounts on bulk quantities of AMACOM books are<br />

available to corporations, professional associations, and other<br />

organizations. For details, contact Special Sales Department,<br />

AMACOM, a division of American Management Association,<br />

1601 Broadway, New York, NY 10019.<br />

Tel.: 212-903-8316. Fax: 212-903-8083.<br />

Web site: www.amacombooks.org<br />

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative<br />

information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with<br />

the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering<br />

legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or<br />

other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent<br />

professional person should be sought.<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Rothwell, William J.<br />

Effective succession planning : ensuring leadership continuity and<br />

building talent from within / William J. Rothwell.— 3rd ed.<br />

p. cm.<br />

Includes bibliographical references and index.<br />

ISBN 0-8144-0842-7<br />

1. Leadership. 2. Executive succession—United States. 3. Executive<br />

ability. 4. Organizational effectiveness. I. Title.<br />

HD57.7.R689 2005<br />

658.4092—dc22<br />

2004024908<br />

2005 William J. Rothwell.<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Printed in the United States of America.<br />

This publication may not be reproduced,<br />

stored in a retrieval system,<br />

or transmitted in whole or in part,<br />

in any form or by any means, electronic,<br />

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,<br />

without the prior written permission of AMACOM,<br />

a division of American Management Association,<br />

1601 Broadway, New York, NY 10019.<br />

Printing number<br />

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO MY WIFE MARCELINA, MY DAUGHTER CANDICE,<br />

MY SON FROILAN, AND MY GRANDSON ADEN

This page intentionally left blank

CONTENTS<br />

List of Exhibits<br />

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

xiii<br />

xvii<br />

xxxi<br />

Advance Organizer for This Book 1<br />

PART I<br />

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ABOUT SUCCESSION<br />

PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT 5<br />

CHAPTER 1<br />

What Is Succession Planning and Management? 7<br />

Six Ministudies: Can You Solve These Succession Problems? 7<br />

Defining Succession Planning and Management 10<br />

Distinguishing Succession Planning and Management from<br />

Replacement Planning, Workforce Planning, Talent Management,<br />

and Human Capital Management 16<br />

Making the Business Case for Succession Planning and Management 18<br />

Reasons for a Succession Planning and Management Program 20<br />

Best Practices and Approaches 30<br />

Ensuring Leadership Continuity in Organizations 35<br />

Summary 39<br />

CHAPTER 2<br />

Trends Influencing Succession Planning and Management 41<br />

The Ten Key Trends 42<br />

What Does All This Mean for Succession Planning and Management? 54<br />

Summary 55<br />

vii

viii<br />

C ONTENTS<br />

CHAPTER 3<br />

Moving to a State-of-the-Art Approach 56<br />

Characteristics of Effective Programs 56<br />

The Life Cycle of Succession Planning and Management Programs:<br />

Five Generations 59<br />

Identifying and Solving Problems with Various Approaches 69<br />

Integrating Whole Systems Transformational Change and<br />

Appreciative Inquiry into Succession: What Are These Topics,<br />

and What Added Value Do They Bring? 76<br />

Requirements for a Fifth-Generation Approach 78<br />

Key Steps in a Fifth-Generation Approach 78<br />

Summary 81<br />

CHAPTER 4<br />

Competency Identification and Values Clarification:<br />

Keys to Succession Planning and Management 82<br />

What Are Competencies? 82<br />

How Are Competencies Used in Succession Planning and<br />

Management? 83<br />

Conducting Competency Identification Studies 84<br />

Using Competency Models 85<br />

New Developments in Competency Identification, Modeling, and<br />

Assessment 85<br />

Identifying and Using Generic and Culture-Specific Competency<br />

Development Strategies to Build Bench Strength 86<br />

What Are Values, and What Is Values Clarification? 87<br />

How Are Values Used in Succession Planning and Management? 89<br />

Conducting Values Clarification Studies 90<br />

Using Values Clarification 91<br />

Bringing It All Together: Competencies and Values 91<br />

Summary 91<br />

PART II<br />

LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR A SUCCESSION<br />

PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT PROGRAM 93<br />

CHAPTER 5<br />

Making the Case for Major Change 95<br />

Assessing Current Problems and Practices 95<br />

Demonstrating the Need 101<br />

Determining Organizational Requirements 108

Contents<br />

ix<br />

Linking Succession Planning and Management Activities to<br />

Organizational and Human Resource Strategy 108<br />

Benchmarking Best Practices and Common Business Practices in<br />

Other Organizations 113<br />

Obtaining and Building Management Commitment 114<br />

The Key Role of the CEO in the Succession Effort 120<br />

Summary 124<br />

CHAPTER 6<br />

Starting a Systematic Program 125<br />

Conducting a Risk Analysis and Building a Commitment to Change 125<br />

Clarifying Program Roles 126<br />

Formulating a Mission Statement 130<br />

Writing Policy and Procedures 136<br />

Identifying Target Groups 138<br />

Clarifying the Roles of the CEO, Senior Managers, and Others 142<br />

Setting Program Priorities 143<br />

Addressing the Legal Framework 145<br />

Establishing Strategies for Rolling Out the Program 147<br />

Summary 155<br />

CHAPTER 7<br />

Refining the Program 156<br />

Preparing a Program Action Plan 156<br />

Communicating the Action Plan 157<br />

Conducting Succession Planning and Management Meetings 160<br />

Training on Succession Planning and Management 164<br />

Counseling Managers About Succession Planning Problems in Their<br />

Areas 172<br />

Summary 174<br />

PART III<br />

ASSESSING THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE 177<br />

CHAPTER 8<br />

Assessing Present Work Requirements and Individual Job<br />

Performance 179<br />

Identifying Key Positions 180<br />

Three Approaches to Determining Work Requirements in Key<br />

Positions 184<br />

Using Full-Circle, Multirater Assessments 189

x<br />

C ONTENTS<br />

Appraising Performance and Applying Performance Management 192<br />

Creating Talent Pools: Techniques and Approaches 195<br />

Thinking Beyond Talent Pools 200<br />

Summary 202<br />

CHAPTER 9<br />

Assessing Future Work Requirements and Individual<br />

Potential 203<br />

Identifying Key Positions and Talent Requirements for the Future 203<br />

Assessing Individual Potential: The Traditional Approach 210<br />

The Growing Use of Assessment Centers and Portfolios 221<br />

Summary 224<br />

PART IV<br />

CLOSING THE ‘‘DEVELOPMENTAL GAP’’: OPERATING<br />

AND EVALUATING A SUCCESSION PLANNING AND<br />

MANAGEMENT PROGRAM 225<br />

CHAPTER 10<br />

Developing Internal Successors 227<br />

Testing Bench Strength 227<br />

Formulating Internal Promotion Policy 232<br />

Preparing Individual Development Plans 235<br />

Developing Successors Internally 242<br />

The Role of Leadership Development Programs 251<br />

The Role of Coaching 252<br />

The Role of Executive Coaching 253<br />

The Role of Mentoring 253<br />

The Role of Action Learning 255<br />

Summary 256<br />

CHAPTER 11<br />

Assessing Alternatives to Internal Development 257<br />

The Need to Manage for ‘‘Getting the Work Done’’ Rather than<br />

‘‘Managing Succession’’ 257<br />

Innovative Approaches to Tapping the Retiree Base 266<br />

Deciding What to Do 268<br />

Summary 270<br />

CHAPTER 12<br />

Using Technology to Support Succession Planning and<br />

Management Programs 271<br />

Defining Online and High-Tech Methods 271

Contents<br />

xi<br />

Where to Apply Technology Methods 276<br />

How to Evaluate and Use Technology Applications 276<br />

What Specialized Competencies Do Succession Planning and<br />

Management Coordinators Need to Use These Applications? 289<br />

Summary 290<br />

CHAPTER 13<br />

Evaluating Succession Planning and Management<br />

Programs 291<br />

What Is Evaluation? 291<br />

What Should Be Evaluated? 292<br />

How Should Evaluation Be Conducted? 295<br />

Summary 306<br />

CHAPTER 14<br />

The Future of Succession Planning and Management 307<br />

The Fifteen Predictions 308<br />

Summary 329<br />

APPENDIX I:<br />

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Succession<br />

Planning and Management 331<br />

APPENDIX II:<br />

Case Studies on Succession Planning and Management 337<br />

Case 1: How Business Plans for Succession 337<br />

Case 2: How Government Plans for Succession 341<br />

Case 3: How a Nonprofit Organization Plans for Succession 354<br />

Case 4: Small Business Case 360<br />

Case 5: Family Business Succession 362<br />

Case 6: CEO Succession Planning Case 363<br />

Notes 367<br />

What’s on the CD? 387<br />

Index 391<br />

About the Author 399

This page intentionally left blank

LIST OF EXHIBITS<br />

Exhibit P-1. Age Distribution of the U.S. Population, Selected Years,<br />

1965–2025 xx<br />

Exhibit P-2. U.S. Population by Age, 1965–2025 xxi<br />

Exhibit P-3. The Organization of the Book xxv<br />

Exhibit 1-1. How General Electric Planned the Succession 11<br />

Exhibit 1-2. The Big Mac Succession 14<br />

Exhibit 1-3. Demographic Information About Respondents to a 2004 Survey<br />

on Succession Planning and Management: Industries 21<br />

Exhibit 1-4. Demographic Information About Respondents to a 2004 Survey<br />

on Succession Planning and Management: Size 21<br />

Exhibit 1-5. Demographic Information About Respondents to a 2004 Survey<br />

on Succession Planning and Management: Job Functions of<br />

Respondents 22<br />

Exhibit 1-6. Reasons for Succession Planning and Management Programs 23<br />

Exhibit 1-7. Strategies for Reducing Turnover and Increasing Retention 26<br />

Exhibit 1-8. Workforce Reductions Among Survey Respondents 29<br />

Exhibit 1-9. A Summary of Best Practices on Succession Planning and<br />

Management from Several Research Studies 31<br />

Exhibit 2-1. An Assessment Questionnaire: How Well Is Your Organization<br />

Managing the Consequences of Trends Influencing Succession<br />

Planning and Management? 43<br />

Exhibit 2-2. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 49<br />

Exhibit 3-1. Characteristics of Effective Succession Planning and<br />

Management Programs 60<br />

Exhibit 3-2. Assessment Questionnaire for Effective Succession Planning<br />

and Management 64<br />

Exhibit 3-3. A Simple Exercise to Dramatize the Need for Succession<br />

Planning and Management 67<br />

Exhibit 3-4. The Dow Chemical Company’s Formula for Succession 70<br />

Exhibit 3-5. Chief Difficulties with Succession Planning and Management<br />

Programs 72<br />

xiii

xiv<br />

L IST OF E XHIBITS<br />

Exhibit 3-6. The Seven-Pointed Star Model for Systematic Succession<br />

Planning and Management 79<br />

Exhibit 4-1. An Interview Guide to Collect Corporate-Culture-Specific<br />

Competency Development Strategies 88<br />

Exhibit 5-1. Strategies for Handling Resistance to Implementing Succession<br />

Planning and Management 97<br />

Exhibit 5-2. The Importance of Succession Planning and Management 98<br />

Exhibit 5-3. Making Decisions About Successors (in Organizations Without<br />

Systematic Succession Planning and Management) 99<br />

Exhibit 5-4. A Questionnaire for Assessing the Status of Succession Planning<br />

and Management in an Organization 102<br />

Exhibit 5-5. A Worksheet for Demonstrating the Need for Succession<br />

Planning and Management 106<br />

Exhibit 5-6. An Interview Guide for Determining the Requirements for a<br />

Succession Planning and Management Program 109<br />

Exhibit 5-7. An Interview Guide for Benchmarking Succession Planning and<br />

Management Practices 115<br />

Exhibit 5-8. Opinions of Top Managers About Succession Planning and<br />

Management 118<br />

Exhibit 5-9. Opinions of Human Resource Professionals About Succession<br />

Planning and Management 119<br />

Exhibit 5-10. Actions to Build Management Commitment to Succession<br />

Planning and Management 121<br />

Exhibit 5-11. Rating Your CEO for His/Her Role in Succession Planning and<br />

Management 123<br />

Exhibit 6-1. A Model for Conceptualizing Role Theory 127<br />

Exhibit 6-2. Management Roles in Succession Planning and Management:<br />

A Grid 129<br />

Exhibit 6-3. A Worksheet to Formulate a Mission Statement for Succession<br />

Planning and Management 133<br />

Exhibit 6-4. A Sample Succession Planning and Management Policy 137<br />

Exhibit 6-5. Targeted Groups for Succession Planning and Management 139<br />

Exhibit 6-6. An Activity for Identifying Initial Targets for Succession<br />

Planning and Management Activities 140<br />

Exhibit 6-7. An Activity for Establishing Program Priorities in Succession<br />

Planning and Management 146<br />

Exhibit 6-8. U.S. Labor Laws 148<br />

Exhibit 7-1. A Worksheet for Preparing an Action Plan to Establish the<br />

Succession Planning and Management Program 158<br />

Exhibit 7-2. Sample Outlines for In-House Training on Succession Planning<br />

and Management 168<br />

Exhibit 8-1. A Worksheet for Writing a Key Position Description 186

List of Exhibits<br />

xv<br />

Exhibit 8-2. A Worksheet for Considering Key Issues in Full-Circle,<br />

Multirater Assessments 191<br />

Exhibit 8-3. The Relationship Between Performance Management and<br />

Performance Appraisal 194<br />

Exhibit 8-4. Approaches to Conducting Employee Performance Appraisal 197<br />

Exhibit 8-5. A Worksheet for Developing an Employee Performance<br />

Appraisal Linked to a Position Description 199<br />

Exhibit 9-1. A Worksheet for Environmental Scanning 205<br />

Exhibit 9-2. An Activity on Organizational Analysis 206<br />

Exhibit 9-3. An Activity for Preparing Realistic Scenarios to Identify Future<br />

Key Positions 208<br />

Exhibit 9-4. An Activity for Preparing Future-Oriented Key Position<br />

Descriptions 209<br />

Exhibit 9-5. Steps in Conducting Future-Oriented ‘‘Rapid Results<br />

Assessment’’ 211<br />

Exhibit 9-6. How to Classify Individuals by Performance and Potential 214<br />

Exhibit 9-7. A Worksheet for Making Global Assessments 216<br />

Exhibit 9-8. A Worksheet to Identify Success Factors 217<br />

Exhibit 9-9. An Individual Potential Assessment Form 218<br />

Exhibit 10-1. A Sample Replacement Chart Format: Typical Succession<br />

Planning and Management Inventory for the Organization 229<br />

Exhibit 10-2. Succession Planning and Management Inventory by Position 230<br />

Exhibit 10-3. Talent Shows: What Happens? 233<br />

Exhibit 10-4. A Simplified Model of Steps in Preparing Individual<br />

Development Plans (IDPs) 237<br />

Exhibit 10-5. A Worksheet for Preparing Learning Objectives Based on<br />

Individual Development Needs 239<br />

Exhibit 10-6. A Worksheet for Identifying the Resources Necessary to<br />

Support Developmental Experiences 241<br />

Exhibit 10-7. A Sample Individual Development Plan 243<br />

Exhibit 10-8. Methods of Grooming Individuals for Advancement 245<br />

Exhibit 10-9. Key Strategies for Internal Development 247<br />

Exhibit 11-1. Deciding When Replacing a Key Job Incumbent Is Unnecessary:<br />

A Flowchart 259<br />

Exhibit 11-2. A Worksheet for Identifying Alternatives to the Traditional<br />

Approach to Succession Planning and Management 267<br />

Exhibit 11-3. A Tool for Contemplating Ten Ways to Tap the Retiree Base 269<br />

Exhibit 12-1. Continua of Online and High-Tech Approaches 272<br />

Exhibit 12-2. A Starting Point for a Rating Sheet to Assess Vendors for<br />

Succession Planning and Management Software 273

xvi<br />

L IST OF E XHIBITS<br />

Exhibit 12-3. A Hierarchy of Online and High-Tech Applications for<br />

Succession Planning and Management 277<br />

Exhibit 12-4. A Worksheet for Brainstorming When and How to Use Online<br />

and High-Tech Methods 280<br />

Exhibit 13-1. The Hierarchy of Succession Planning and Management<br />

Evaluation 294<br />

Exhibit 13-2. Guidelines for Evaluating the Succession Planning and<br />

Management Program 296<br />

Exhibit 13-3. A Worksheet for Identifying Appropriate Ways to Evaluate<br />

Succession Planning and Management in an Organization 298<br />

Exhibit 13-4. A Sample ‘‘Incident Report’’ for Succession Planning and<br />

Management 299<br />

Exhibit 13-5. Steps for Completing a Program Evaluation of a Succession<br />

Planning and Management Program 301<br />

Exhibit 13-6. A Checksheet for Conducting a Program Evaluation for the<br />

Succession Planning and Management Program 303<br />

Exhibit 14-1. A Worksheet to Structure Your Thinking About Predictions for<br />

Succession Planning and Management in the Future 309<br />

Exhibit 14-2. A Worksheet to Structure Your Thinking About Alternative<br />

Approaches to Meeting Succession Needs 314<br />

Exhibit 14-3. Age Distribution of the U.S. Population in 2025 317<br />

Exhibit 14-4. Age Distribution of the Chinese Population in 2025 318<br />

Exhibit 14-5. Age Distribution of the Population in the United Kingdom<br />

in 2025 318<br />

Exhibit 14-6. Age Distribution of the French Population in 2025 319<br />

Exhibit 14-7. Important Characteristics of Career Planning and Management<br />

Programs 323<br />

Exhibit 14-8. An Assessment Sheet for Integrating Career Planning and<br />

Management Programs with Succession Planning and<br />

Management Programs 325

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION<br />

A colleague told me over the phone the other day that ‘‘there have been no<br />

new developments in succession planning for decades.’’ My response was,<br />

‘‘Au contraire. There have been many changes. Perhaps you are simply not<br />

conversant with how the playing field has changed.’’ I pointed out to him that,<br />

since the second edition of this book was published, there have been many<br />

changes in the world and in succession planning. Allow me a moment to list a<br />

few:<br />

Changes in the World<br />

▲ The Aftereffects of 9/11. When the World Trade Center was destroyed,<br />

172 corporate vice presidents lost their lives. That tragic event reinforced the<br />

message, earlier foreshadowed by the tragic loss of life in Oklahoma City, that<br />

life is fragile and talent at all levels is increasingly at risk in a world where<br />

disaster can strike unexpectedly. In a move that would have been unthinkable<br />

ten years ago, some organizations are examining their bench strength in locations<br />

other than their headquarters in New York City, Washington, or other<br />

cities that might be prone to attack if terrorists should wipe out a whole city<br />

through use of a dirty nuclear weapon or other chemical or biological agent.<br />

Could the organization pick up the pieces and continue functioning without<br />

headquarters? That awful, but necessary, question is on the minds of some<br />

corporate and government leaders today. (In fact, one client of mine has set a<br />

goal of making a European capital the alternative corporate headquarters, with<br />

a view toward having headquarters completely re-established in Europe within<br />

24 hours of the total loss of the New York City headquarters, if disaster should<br />

strike.)<br />

▲ The Aftereffects of Many Corporate Scandals. Ethics, morality, and values<br />

have never been more prominent than they are today. In the wake of<br />

the scandals affecting Enron, Global Crossing, WorldCom, and many other<br />

corporations—and the incredible departure of Arthur Andersen from the corporate<br />

world—many leaders have recognized that ethics, morality, and values<br />

do matter. Corporate boards have gotten more involved in succession planxvii

xviii<br />

P REFACE TO THE THIRD E DITION<br />

ning and management owing, in part, to the requirements of the Sarbanes-<br />

Oxley Act. And corporate leaders, thinking about succession, realize that future<br />

leaders must model the behaviors they want others to exhibit and must avoid<br />

practices that give even the mere appearance of impropriety.<br />

▲ Growing Recognition of the Aging Workforce. Everyone is now talking<br />

about the demographic changes sweeping the working world in the United<br />

States and in the other nations of the G-8. Some organizations have already<br />

felt the effects of talent loss resulting from retirements of experienced workers.<br />

▲ Growing Awareness that Succession Issues Amount to More Than Finding<br />

Replacements. When experienced people leave organizations, they take<br />

with them not only the capacity to do the work but also the accumulated<br />

wisdom they have acquired. That happens at all levels and in all functional<br />

areas. Succession involves more than merely planning for replacements at the<br />

top. It also involves thinking through what to do when the most experienced<br />

people at all levels depart—and take valuable institutional memory with them.<br />

Changes in Succession Planning<br />

▲ The Emergence of ‘‘Talent Management’’ and ‘‘Talent Development.’’<br />

As is true in so many areas of management, these terms may well be in search<br />

of meanings. They have more than one meaning. But, in many cases, talent<br />

management refers to the efforts taken to attract, develop, and retain best-inclass<br />

employees—dubbed high performers (or HiPers) and high potentials (or<br />

HiPos) by some. Talent development may refer to efforts to groom HiPers or<br />

HiPos for the future. Think of it as selective attention paid to the top performing<br />

10 percent of employees—that’s one way it is thought of.<br />

▲ The Emergence of ‘‘Workforce Planning.’’ While some people think that<br />

succession planning is limited to the top of the organization chart—which I<br />

do not believe, by the way—others regard comprehensive planning for the<br />

future staffing needs of the organization as workforce planning. It is also a<br />

popular term for succession planning in government, rivaling the term human<br />

capital management in that venue.<br />

▲ Growing Awareness of Succession Planning. More decision-makers are<br />

becoming aware of the need for succession planning as they scurry to find<br />

replacements for a pending tidal wave of retirements in the wake of years of<br />

downsizing, rightsizing, and smartsizing.<br />

▲ The Recognition that Succession Planning Is Only One of Many Solutions.<br />

When managers hear that they are losing a valuable—and experienced—<br />

worker, their first inclination is to clutch their hearts and say ‘‘Oh, my heavens,<br />

I have only two ways to deal with the problem—promote from inside or hire<br />

from outside. The work is too specialized to hire from outside, and the organization<br />

has such weak bench strength that it is not possible to promote from<br />

within. Therefore, we should get busy and build a succession program.’’ Of

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

xix<br />

course, that is much too limited a view. The goal is to get the work done and<br />

not replace people. There are many ways to get the work done.<br />

▲ Growing Awareness of Technical Succession Planning. While succession<br />

planning is typically associated with preparing people to make vertical<br />

moves on the organization chart, it is also possible to think about individuals<br />

such as engineers, lawyers, research scientists, MIS professionals, and other<br />

professional or technical workers who possess specialized knowledge. When<br />

they leave the organization, they may take critically important, and proprietary,<br />

knowledge with them. Hence, growing awareness exists for the need to do<br />

technical succession planning, which focuses on the horizontal level of the<br />

organization chart and involves broadening and deepening professional<br />

knowledge and preserving it for the organization’s continued use in the future.<br />

▲ Continuing Problems with HR Systems. HR systems are still not up to<br />

snuff. As I consult in this field, I see too little staffing in HR departments,<br />

poorly skilled HR workers, voodoo competency modeling efforts, insufficient<br />

technology to support robust applications like succession, and many other<br />

problems with the HR function itself, including timid HR people who are unwilling<br />

to stand up to the CEO or their operating peers and exert true leadership<br />

about what accountability systems are needed to make sure that managers<br />

do their jobs to groom talent at the same time that they struggle to get today’s<br />

work out the door.<br />

Still, my professional colleague was right in the sense that the world continues<br />

to face the crisis of leadership that was described in the preface to the<br />

first and second editions of this book. Indeed, ‘‘a chronic crisis of governance—that<br />

is, the pervasive incapacity of organizations to cope with the expectations<br />

of their constituents—is now an overwhelming factor worldwide.’’ 1<br />

That statement is as true today as it was when this book was first published in<br />

1994. Evidence can still be found in many settings: Citizens continue to lose<br />

faith in their elected officials to address problems at the national, regional, and<br />

local levels; the religious continue to lose faith in high-profile church leaders<br />

who have been stricken with sensationalized scandals; and consumers continue<br />

to lose faith in business leaders to act responsibly and ethically. 2 Add to<br />

those problems some others: people have lost faith that the media like newspapers<br />

or television stations, now owned by enormous corporations, tell them<br />

the truth—or that reporters have even bothered to check the facts; and patients<br />

have lost faith that doctors, many of whom are now employed by large<br />

profit-making HMOs, are really working to ‘‘do no harm.’’<br />

A crisis of governance is also widespread inside organizations. Employees<br />

wonder what kind of employment they can maintain when a new employment<br />

contract has changed the relationship between workers and their organizations.<br />

Employee loyalty is a relic of the past, 3 a victim of the downsizing craze

xx<br />

P REFACE TO THE THIRD E DITION<br />

so popular in the 1990s and that persists in some organizations to the present<br />

day. Changing demographics makes the identification of successors key to the<br />

future of many organizations when the legacy of the cutbacks in the middlemanagement<br />

ranks, traditional training ground for senior executive positions,<br />

has begun to be felt. If that is hard to believe, consider that 20 percent of the<br />

best-known companies in the United States may lose 40 percent of their senior<br />

executives to retirement at any time. 4 Demographics tell the story: The U.S.<br />

population is aging, and that could mean many retirements soon. (See Exhibits<br />

P-1 and P-2.)<br />

Amid the twofold pressures of pending retirements in senior executive<br />

ranks and the increasing value of intellectual capital and knowledge management,<br />

it is more necessary than ever for organizations to plan for leadership<br />

continuity and employee advancement at all levels. But that is easier said than<br />

done. It is not consistent with longstanding tradition, which favors quick-fix<br />

solutions to succession planning and management (SP&M) issues. Nor is it<br />

consistent with the continuing, current trends favoring slimmed-down<br />

staffing, outsourcing, and the use of contingent workers, which often create a<br />

shallow talent pool from which to choose future leaders.<br />

In previous decades, labor in the United States was plentiful and taken for<br />

Exhibit P-1. Age Distribution of the U.S. Population, Selected Years,<br />

1965–2025<br />

Population (thousands)<br />

25,000<br />

20,000<br />

15,000<br />

10,000<br />

5,000<br />

1965<br />

2015<br />

1995<br />

0<br />

16–19<br />

20–24<br />

25–29<br />

30–34<br />

35–39<br />

40–44<br />

45–49<br />

Age<br />

50–54<br />

55–59<br />

60–64<br />

65–69<br />

70–74<br />

75–79<br />

80+<br />

Source: Stacy Poulos and Demetra S. Nightengale, ‘‘The Aging Baby Boom: Implications for Employment and Training Programs.’’<br />

Presented at http://www.urban.org/aging/abb/agingbaby.html. This report was prepared by the U.S. Department of Labor under<br />

Contract No. F-5532-5-00-80-30.

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

xxi<br />

Exhibit P-2. U.S. Population by Age, 1965–2025<br />

100000<br />

90000<br />

80000<br />

70000<br />

16–24 yr olds<br />

25–34 yr olds<br />

35–44 yr olds<br />

45–54 yr olds<br />

55 & older<br />

60000<br />

50000<br />

40000<br />

30000<br />

20000<br />

10000<br />

1965 1975<br />

1985<br />

1995<br />

2005<br />

2015<br />

2025<br />

Year<br />

Source: Stacy Poulos and Demetra S. Nightengale, ‘‘The Aging Baby Boom: Implications for Employment and Training Programs.’’<br />

Presented at http://www.urban.org/aging/abb/agingbaby.html. This report was prepared by the U.S. Department of Labor under<br />

Contract No. F-5532-5-00-80-30.<br />

granted. Managers had the leisure to groom employees for advancement over<br />

long time spans and to overstaff as insurance against turnover in key positions.<br />

That was as true for management as for nonmanagement employees. Most<br />

jobs did not require extensive prequalification. Seniority (sometimes called<br />

job tenure), as measured by time with an organization or in an industry, was<br />

sufficient to ensure advancement.<br />

Succession planning and management activities properly focused on leaders<br />

at the peak of tall organizational hierarchies because organizations were<br />

controlled from the top down and were thus heavily dependent on the knowledge,<br />

skills, and attitudes of top management leaders. But times have changed.<br />

Few organizations have the luxury to overstaff in the face of fierce competition<br />

from low-cost labor abroad and economic restructuring efforts. That is particu-

xxii<br />

P REFACE TO THE THIRD E DITION<br />

larly true in high-technology companies where several months’ experience<br />

may be the equivalent of one year’s work in a traditional organization.<br />

At the same time, products, markets, and management activities have<br />

grown more complex. Many jobs now require extensive prequalification, both<br />

inside and outside organizations. A track record of demonstrated and successful<br />

work performance, more than mere time in position, and leadership competency<br />

have become key considerations as fewer employees compete for<br />

diminishing advancement opportunities. As employee empowerment has<br />

broadened the ranks of decision-makers, leadership influence can be exerted<br />

at all hierarchical levels rather than limited to those few granted authority by<br />

virtue of their lofty titles and management positions.<br />

For these reasons, organizations must take proactive steps to plan for future<br />

talent needs at all levels and implement programs designed to ensure that<br />

the right people are available for the right jobs in the right places and at the<br />

right times to meet organizational requirements. Much is at stake in this process:<br />

‘‘The continuity of the organization over time requires a succession of<br />

persons to fill key positions.’’ 5 There are important social implications as well.<br />

As management guru Peter Drucker explained in words as true today as when<br />

they were written 6 :<br />

The question of tomorrow’s management is,<br />

above all, a concern of our society. Let me put<br />

it bluntly—we have reached a point where we<br />

simply will not be able to tolerate as a country,<br />

as a society, as a government, the danger<br />

that any one of our major companies will<br />

decline or collapse because it has not made<br />

adequate provisions for management succession.<br />

[emphasis added]<br />

Research adds weight to the argument favoring SP&M. First, it has been<br />

shown that firms in which the CEO has a specific successor in mind are more<br />

profitable than those in which no specific successor has been identified. A<br />

possible reason is that selecting a successor ‘‘could be viewed as a favorable<br />

general signal about the presence and development of high-quality top management.’’<br />

7 In other words, superior-performing CEOs make SP&M and leadership<br />

continuity top priorities. Succession planning and management has<br />

even been credited with driving a plant turnaround by linking the organization’s<br />

continuous improvement philosophy to individual development. 8<br />

But ensuring leadership continuity can be a daunting undertaking. The<br />

rules, procedures, and techniques used in the past appear to be growing increasingly<br />

outmoded and inappropriate. It is time to revisit, rethink, and even<br />

reengineer SP&M. That is especially true because, in the words of one observer<br />

of the contemporary management scene, ‘‘below many a corporation’s top

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

xxiii<br />

two or three positions, succession planning [for talent] is often an informal,<br />

haphazard exercise where longevity, luck, and being in the proverbial right<br />

place at the right time determines lines of succession.’’ 9 A haphazard approach<br />

to SP&M bodes ill for organizations in which leadership talent is diffused—and<br />

correspondingly important—at all hierarchical levels and yet the need exists<br />

to scramble organizational resources quickly to take advantage of business<br />

opportunities or deal with crises.<br />

The Purpose of This Book<br />

Succession planning and management and leadership development figure<br />

prominently on the agenda of many top managers. Yet, despite senior management<br />

interest, the task often falls to human resource management (HRM) and<br />

workplace learning and performance (WLP) professionals to spearhead and<br />

coordinate efforts to establish and operate planned succession programs and<br />

avert succession crises. In that way, they fill an important, proactive role demanded<br />

of them by top managers, and they ensure that SP&M issues are not<br />

lost in the shuffle of fighting daily fires.<br />

But SP&M is rarely, if ever, treated in most undergraduate or graduate<br />

college degree programs—even in those specifically tailored to preparing HRM<br />

and WLP professionals. For this reason, HRM and WLP professionals often<br />

need assistance when they coordinate, establish, operate, or evaluate SP&M<br />

programs. This book is intended to provide that help. It offers practical,<br />

how-to-do-it advice on SP&M. The book’s scope is deliberately broad. It encompasses<br />

more than management succession planning, which is the most<br />

frequently discussed topic by writers and consultants in the field. Stated succinctly,<br />

the purpose of this book is to reassess SP&M and offer a current, fresh<br />

but practical approach to ensuring leadership continuity in key positions and<br />

building leadership talent from within.<br />

Succession planning and management should support strategic planning<br />

and strategic thinking and should provide an essential starting point for management<br />

and employee development programs. Without it, organizations will<br />

have difficulty maintaining leadership continuity—or identifying appropriate<br />

leaders when a change in business strategy is necessary. While many large<br />

blue-chip corporations operate best-practice SP&M programs, small and medium-sized<br />

businesses also need them. In fact, inadequate succession plans<br />

are a common cause of small business failure as founding entrepreneurs fade<br />

from the scene, leaving no one to continue their legacy, 10 and as tax laws exert<br />

an impact on the legacy of those founders as they pass away. Additionally,<br />

nonprofit enterprises and government agencies need to give thought to planning<br />

for future talent.<br />

Whatever an organization’s size or your job responsibilities, then, this<br />

book should provide useful information on establishing, managing, operating,<br />

and evaluating SP&M programs.

xxiv<br />

P REFACE TO THE THIRD E DITION<br />

Sources of Information<br />

As I began writing this book I decided to explore state-of-the-art succession<br />

planning and management practices. I consulted several major sources of information:<br />

1. A Tailor-Made Survey. In 2004 I surveyed over 500 HRM professionals<br />

about SP&M practices in their organizations. Selected survey results,<br />

which were compiled in June 2004, are published in this book for the<br />

first time. This survey was an update of earlier surveys conducted for<br />

the first edition (1994) and second edition (2000) of this book. While<br />

the response rate to this survey was disappointing, the results do provide<br />

interesting information.<br />

2. Phone Surveys and Informal Benchmarking. I spoke by phone and in<br />

person with vendors of specialized succession planning software and<br />

discussed SP&M with workplace learning and performance professionals<br />

in major corporations.<br />

3. Other Surveys. I researched other surveys that have been conducted on<br />

SP&M in recent years and, giving proper credit when due, I summarize<br />

key findings of those surveys at appropriate points in the book.<br />

4. Web Searches. I examined what resources could be found on the World<br />

Wide Web relating to important topics in this book.<br />

5. A Literature Search. I conducted an exhaustive literature review on<br />

SP&M—with special emphasis on what has been written on the subject<br />

since the last edition of this book. I also looked for case-study descriptions<br />

of what real organizations have been doing.<br />

6. Firsthand In-House Work Experience. Before entering the academic<br />

world, I was responsible for a comprehensive management development<br />

(MD) program in a major corporation. As part of that role I coordinated<br />

management SP&M. My experiences are reflected in this book.<br />

7. Extensive External Consulting and Public Speaking. Since entering academe,<br />

I have also done extensive consulting and public speaking on the<br />

topic of SP&M. I spoke about succession planning to sixty-four CEOs of<br />

the largest corporations in Singapore; conducted training on succession<br />

in Asia and in Europe; keynoted several conferences on succession<br />

and spoke on the topic at many conferences; and provided guidance<br />

for a major research study of best practices on the topic in large corporations.<br />

Most recently, I have focused attention on best practices in government<br />

succession at all levels—local, state, federal, and international.<br />

The aim of these sources is to ensure that this book will provide a comprehensive<br />

and up-to-date treatment of typical and best-in-class SP&M practices<br />

in organizations of various sizes and types operating in different industries.

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

xxv<br />

The Scheme of This Book<br />

Effective Succession Planning: Ensuring Leadership Continuity and Building<br />

Talent from Within, Third Edition, is written for those wishing to establish,<br />

revitalize, or review an SP&M program within their organizations. It is geared<br />

to meet the needs of HRM and WLP executives, managers, and professionals.<br />

It also contains useful information for chief executive officers, chief operating<br />

officers, general managers, university faculty members who do consulting,<br />

management development specialists who are looking for a detailed treatment<br />

of the subject as a foundation for their own efforts, SP&M program coordinators,<br />

and others bearing major responsibilities for developing management,<br />

professional, technical, sales, or other employees.<br />

The book is organized in four parts. (See Exhibit P-3.) Part I sets the stage.<br />

Chapter 1 opens with dramatic vignettes illustrating typical—and a few rivet-<br />

Exhibit P-3. The Organization of the Book<br />

Part I<br />

Background Information About<br />

Succession Planning and Management<br />

Part IV<br />

Closing the “Developmental Gap”:<br />

Operating and Evaluating a Succession<br />

Planning and Management Program<br />

Part II<br />

Laying the Foundation for a<br />

Succession Planning and<br />

Management Program<br />

Part III<br />

Assessing the Present and the Future

xxvi<br />

P REFACE TO THE THIRD E DITION<br />

ingly atypical—problems in SP&M. The chapter also defines succession planning<br />

and management. It also distinguishes it from replacement planning,<br />

workforce planning, talent management, and human capital management.<br />

Then the chapter goes on to emphasize its importance, explain why organizations<br />

sponsor such programs, and describe different approaches to succession<br />

planning and management.<br />

Chapter 2 describes key trends influencing succession planning and management.<br />

Those trends are: (1) the need for speed; (2) a seller’s market for<br />

skills; (3) reduced loyalty among employers and workers; (4) the importance<br />

of intellectual capital and knowledge management; (5) the key importance of<br />

values and competencies; (6) more software available to support succession;<br />

(7) the growing activism of boards of directors; (8) growing awareness of similarities<br />

and differences in succession issues globally; (9) growing awareness of<br />

similarities and differences of succession programs in special venues: government,<br />

nonprofit, education, small business, and family business; and (10)<br />

managing a special issue: CEO succession. The chapter clarifies what these<br />

trends mean for SP&M efforts.<br />

Chapter 3 summarizes the characteristics of effective SP&M programs, describes<br />

the life cycle of SP&M programs, identifies and solves common problems<br />

with various approaches to SP&M, describes the requirements and key<br />

steps in a fifth-generation approach to SP&M, and explains how new approaches<br />

to organizational change may be adapted for use with SP&M.<br />

Chapter 4 defines competencies, explains how they are used in SP&M,<br />

summarizes how to conduct competency studies for SP&M and use the results,<br />

explains how organizational leaders can ‘‘build’’ competencies using development<br />

strategies, defines values, and explains how values and values clarification<br />

can guide SP&M efforts.<br />

Part II consists of Chapters 5 through 7. It lays the foundation for an effective<br />

SP&M program. Chapter 5 describes how to make the case for change,<br />

often a necessary first step before any change effort can be successful. The<br />

chapter reviews such important steps in this process as assessing current<br />

SP&M practices, demonstrating business need, determining program requirements,<br />

linking SP&M to strategic planning and human resource planning,<br />

benchmarking SP&M practices in other organizations, and securing management<br />

commitment. It also emphasizes the critical importance of the CEO’s<br />

role in SP&M in businesses.<br />

Building on the previous chapter, Chapter 6 explains how to clarify roles<br />

in an SP&M program; formulate the program’s mission, policy, and procedure<br />

statements; identify target groups; and set program priorities. It also addresses<br />

the legal framework in SP&M and provides advice about strategies for rolling<br />

out an SP&M program.<br />

Chapter 7 rounds out Part II. It offers advice on preparing a program action<br />

plan, communicating the action plan, conducting SP&M meetings, designing<br />

and delivering training to support SP&M, and counseling managers about<br />

SP&M problems uniquely affecting them and their areas of responsibility.

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

xxvii<br />

Part III comprises Chapters 8 and 9. It focuses on assessing present work<br />

requirements in key positions, present individual performance, future work<br />

requirements, and future individual potential. Crucial to an effective SP&M<br />

program, these activities are the basis for subsequent individual development<br />

planning.<br />

Chapter 8 examines the present situation. It addresses the following questions:<br />

▲ How are key positions identified?<br />

▲ What three approaches can be used to determining work requirements<br />

in key positions?<br />

▲ How can full-circle, multirater assessment be used in SP&M?<br />

▲ How is performance appraised?<br />

▲ What techniques and approaches can be used in creating talent pools?<br />

Chapter 9 examines the future. Related to Chapter 8, it focuses on these<br />

questions:<br />

▲ What key positions are likely to emerge in the future?<br />

▲ What will be the work requirements in those positions?<br />

▲ What is individual potential assessment, and how can it be carried out?<br />

Part IV consists of Chapters 10 through 14. Chapters in this part focus on<br />

closing the developmental gap by operating and evaluating an SP&M program.<br />

Chapter 10 offers advice for testing the organization’s overall bench strength,<br />

explains why an internal promotion policy is important, defines the term individual<br />

development plan (IDP), describes how to prepare and use an IDP<br />

to guide individual development, and reviews important methods to support<br />

internal development.<br />

Chapter 11 moves beyond the traditional approach to SP&M. It offers alternatives<br />

to internal development as the means by which to meet replacement<br />

needs. The basic idea of the chapter is that underlying a replacement need is<br />

a work need that must be satisfied. There are, of course, other ways to meet<br />

work needs than by replacing a key position incumbent. The chapter provides<br />

a decision model to distinguish between situations when replacing a key position<br />

incumbent is—and is not—warranted.<br />

Chapter 12 examines how to apply online and high-tech approaches to<br />

SP&M programs. The chapter addresses four major questions: (1) How are<br />

online and high-tech methods defined? (2) In what areas of SP&M can online<br />

and high-tech methods be applied? (3) How are online and high-tech applications<br />

used? and (4) What specialized competencies are required by succession<br />

planning coordinators to use these applications?<br />

Chapter 13 is about evaluation, and it examines possible answers to three

xxviii<br />

P REFACE TO THE THIRD E DITION<br />

simple questions: (1) What is evaluation? (2) What should be evaluated in<br />

SP&M? and (3) How should an SP&M program be evaluated?<br />

Chapter 14 concludes the book. It offers eight predictions about SP&M.<br />

More specifically, I end the book by predicting that SP&M will: (1) prompt<br />

efforts by decision-makers to find flexible strategies to address future organizational<br />

talent needs; (2) lead to integrated retention policies and procedures<br />

that are intended to identify high-potential talent earlier, retain that talent,<br />

and preserve older high-potential workers; (3) have a global impact; (4) be<br />

influenced increasingly by real-time technological innovations; (5) become an<br />

issue in government agencies, academic institutions, and nonprofit enterprises<br />

in a way never before seen; (6) lead to increasing organizational openness<br />

about possible successors; (7) increasingly be integrated with career development<br />

issues; and (8) be heavily influenced in the future by concerns about<br />

work/family balance and spirituality.<br />

The book ends with two appendices. Appendix I addresses frequently<br />

asked questions (FAQs) about succession planning and management. Appendix<br />

II provides a range of case studies about succession planning and management<br />

that describe how it is applied in various settings.<br />

One last thing. You may be asking yourself: ‘‘How is the third edition of<br />

this classic book different from the second edition?’’ While I did not add or<br />

drop chapters, I did make many changes to this book. Allow me to list just a<br />

few:<br />

▲ The book opens with an Advance Organizer, a new feature that allows<br />

you to assess the need for an effective SP&M program in your organization<br />

and to go immediately to chapters that address special needs.<br />

▲ The survey research cited in this book is new, conducted in year 2004.<br />

▲ The literature cited in the book has been expanded and updated.<br />

▲ New sections in one chapter have been added on specialized topics<br />

within succession, including: (1) CEO succession; (2) succession in government;<br />

(3) succession in small business; (4) succession in family business;<br />

and (5) succession in international settings.<br />

▲ A new section has been added on using assessment centers and work<br />

portfolios in potential assessment.<br />

▲ A new section has been added on the use of psychological assessments<br />

in succession, a topic of growing interest.<br />

▲ The section on competency identification, modeling, and assessment<br />

has been updated.<br />

▲ A new section has been added on planning developmental strategies.<br />

▲ A new section has been added on the CEO’s role in succession.<br />

▲ The book closes with a selection of frequently asked questions (FAQs)<br />

about succession planning and management, which is new.

Preface to the Third Edition<br />

xxix<br />

▲ A CD-ROM has been added to the book—a major addition in its own<br />

right—and it contains reproducible copies of all assessment instruments<br />

and worksheets that appear in the book as well as three separate<br />

briefings/workshops: one on mentoring, one as an executive briefing on<br />

succession, and one on the manager’s role in succession. (The table of<br />

contents for the CD is found at the back of this book.)<br />

All these changes reflect the many changes that have occurred in the succession<br />

planning and management field within the last few years and since the<br />

last edition was published.<br />

William J. Rothwell<br />

University Park, Pennsylvania<br />

January 2005

This page intentionally left blank

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Writing a book resembles taking a long journey. The researching, drafting, and<br />

repeated revising requires more time, effort, patience, and self-discipline than<br />

most authors care to admit or have the dedication to pursue. Yet no book is<br />

written in isolation. Completing such a journey requires any author to seek<br />

help from many people, who provide advice—and directions—along the way.<br />

This is my opportunity to thank those who have helped me. I would therefore<br />

like to extend my sincere appreciation to my graduate research assistants,<br />

Ms. Wang Wei and Ms. Yeonsoo Kim, for their excellent and able assistance in<br />

helping me to send out and analyze the survey results, and for helping me to<br />

track down and secure necessary copyright permissions.<br />

I would also like to thank Adrienne Hickey and other staff members at<br />

AMACOM, who offered numerous useful ideas on the project while demonstrating<br />

enormous patience with me and my busy schedule in consulting and<br />

presenting around the world.<br />

xxxi

This page intentionally left blank

ADVANCE ORGANIZER<br />

FOR THIS BOOK<br />

Complete the following assessment before you read this book. Use it to help<br />

you assess the need for an effective succession planning and management<br />

(SP&M) program in your organization. You may also use it to refer directly to<br />

topics in the book that are of special importance to you now.<br />

Directions: Read each item below. Circle Y (yes), N/A (not applicable), or<br />

N (no) in the left column next to each item. Spend about 15 minutes on this.<br />

Think of succession planning and management in your organization as you<br />

believe it is—not as you think it should be. When you finish, score and interpret<br />

the results using the instructions appearing at the end of this Advance<br />

Organizer. Then be prepared to share your responses with others in your organization<br />

as a starting point for planning. If you would like to learn more about<br />

one item below, refer to the number in the right column to find the chapter in<br />

this book in which the subject is discussed.<br />

Circle your response in the left-hand column for each response below.<br />

Has your organization:<br />

Chapter<br />

Y N/A N 1. Clearly defined the need for succession 1<br />

planning and management (SP&M)?<br />

Y N/A N 2. Distinguished succession planning and 1<br />

management from replacement, workforce<br />

planning, talent management, and human<br />

capital management?<br />

Y N/A N 3. Made the business case by showing the im- 1<br />

portance of succession planning and management?<br />

Y N/A N 4. Clarified the reasons (goals) for the succes- 1<br />

sion planning and management program?<br />

Y N/A N 5. Investigated best practices and approaches 1<br />

to succession planning and management?<br />

Y N/A N 6. Considered the drivers of change and the 2<br />

trends that may influence succession planning<br />

and management?<br />

1

2 E FFECTIVE S UCCESSION P LANNING<br />

Y N/A N 7. Clarified how trends, as they unfold, may 2<br />

influence succession planning and management<br />

in your organization?<br />

Y N/A N 8. Investigated the characteristics of effective 3<br />

succession planning and management programs?<br />

Y N/A N 9. Thought about how to roll out a succes- 3<br />

sion planning and management program?<br />

Y N/A N 10. Set out to identify, and try to avoid, com- 3<br />

mon problems with succession planning<br />

and management?<br />

Y N/A N 11. Considered integrating whole-systems 3<br />

transformational change into the succession<br />

planning and management program?<br />

Y N/A N 12. Considered integrating appreciative in- 3<br />

quiry into the succession planning and<br />

management program?<br />

Y N/A N 13. Planned for what might be required to es- 3<br />

tablish a state-of-the-art approach to the<br />

succession planning and management program?<br />

Y N/A N 14. Defined competencies as they might be 4<br />

used in your organization?<br />

Y N/A N 15. Considered how competency models 4<br />

might be used for your succession planning<br />

and management program?<br />

Y N/A N 16. Explored new developments in compe- 4<br />

tency identification, modeling, and assessment<br />

for the succession planning and<br />

management program?<br />

Y N/A N 17. Identified competency development strat- 4<br />

egies to build bench strength?<br />

Y N/A N 18. Specifically considered how values might 4<br />

impact the succession planning and management<br />

program?<br />

Y N/A N 19. Determined organizational requirements 5<br />

for the succession planning and management<br />

program?<br />

Y N/A N 20. Linked succession planning and manage- 5<br />

ment activities to organizational and<br />

human resource strategy?<br />

Y N/A N 21. Benchmarked best practices and common 5<br />

business practices in succession planning<br />

and management practices in other organizations?

Advance Organizer for This Book<br />

3<br />

Y N/A N 22. Obtained and built management commit- 5<br />

ment to systematic succession planning<br />

and management?<br />

Y N/A N 23. Clarified the key role to be played by the 5<br />

CEO in the succession effort?<br />

Y N/A N 24. Conducted a risk analysis? 6<br />

Y N/A N 25. Formulated a mission statement for the 6<br />

succession effort?<br />

Y N/A N 26. Written policy and procedures to guide the 6<br />

succession effort?<br />

Y N/A N 27. Identified target groups for the succession 6<br />

effort?<br />

Y N/A N 28. Set program priorities? 6<br />

Y N/A N 29. Addressed the legal framework affecting 6<br />

the the succession planning and management<br />

program?<br />

Y N/A N 30. Established strategies for rolling out the 6<br />

program?<br />

Y N/A N 31. Prepared a program action plan? 7<br />

Y N/A N 32. Communicated the action plan? 7<br />

Y N/A N 33. Conducted succession planning and man- 7<br />

agement meetings?<br />

Y N/A N 34. Trained on succession planning and man- 7<br />

agement?<br />

Y N/A N 35. Counseled managers about succession 7<br />

planning problems in their areas?<br />

Y N/A N 36. Identified key positions? 8<br />

Y N/A N 37. Appraised performance and applied per- 8<br />

formance management?<br />

Y N/A N 38. Considered creating talent pools? 8<br />

Y N/A N 39. Thought of possibilities beyond talent 8<br />

pools?<br />

Y N/A N 40. Identified key positions for the future? 9<br />

Y N/A N 41. Assessed individual potential for promot- 9<br />

ability on some systematic basis?<br />

Y N/A N 42. Considered using assessment centers? 9<br />

Y N/A N 43. Considered using work portfolios to assess 9<br />

individual potential?<br />

Y N/A N 44. Tested bench strength? 10<br />

Y N/A N 45. Formulated internal promotion policy? 10<br />

Y N/A N 46. Prepared individual development plans? 10<br />

Y N/A N 47. Developed successors internally? 10<br />

Y N/A N 48. Considered using leadership development 10<br />

programs in succession planning?

4 E FFECTIVE S UCCESSION P LANNING<br />

Y N/A N 49. Considered using executive coaching in 10<br />

succession planning?<br />

Y N/A N 50. Considered using mentoring in succession 10<br />

planning?<br />

Y N/A N 51. Considered using action learning in suc- 10<br />

cession planning?<br />

Y N/A N 52. Explored alternative ways to get the work 11<br />

done beyond succession?<br />

Y N/A N 53. Explored innovative approaches to tap- 11<br />

ping the retiree base?<br />

Y N/A N 54. Investigated how online and high-tech 12<br />

methods be applied?<br />

Y N/A N 55. Decided what should be evaluated? 13<br />

Y N/A N 56. Decided how the program can be evalu- 13<br />

ated?<br />

Y N/A N 57. Considered how changing conditions may 14<br />

affect the succession planning and management<br />

program?<br />

Scoring and Interpreting the Advance Organizer<br />

Give your organization one point for each Y and zero for each N or N/A. Total<br />

the number of Ts, and place the sum in the line next to the word TOTAL.<br />

Then interpret your score as follows:<br />

50 or more Your organization is apparently using effective succession planning<br />

and management practices.<br />

40 to 49 Improvements could be made to succession planning and management<br />

practices. On the whole, however, the organization is<br />

proceeding on the right track.<br />

30 to 39 Succession planning and management practices in your organization<br />

do not appear to be as effective as they should be. Significant<br />

improvements should be made.<br />

28 or less Succession planning and management practices are ineffective<br />

in your organization. They are probably a source of costly mistakes,<br />

productivity losses, and unnecessary employee turnover.<br />

Take immediate corrective action.

PART<br />

I<br />

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ABOUT<br />

SUCCESSION PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT<br />

Part I<br />

Background Information About<br />

Succession Planning and Management<br />

Part IV<br />

Closing the “Developmental Gap”:<br />

Operating and Evaluating a Succession<br />

Planning and Management Program<br />

Part II<br />

Laying the Foundation for a<br />

Succession Planning and<br />

Management Program<br />

Part III<br />

Assessing the Present and the Future<br />

•Defines SP&M.<br />

•Distinguishes SP&M from replacement planning.<br />

•Describes the importance of SP&M.<br />

•Lists reasons for an SP&M program.<br />

•Reviews approaches to SP&M.<br />

•Reviews key trends influencing SP&M and explains their implications.<br />

•Lists key characteristics of effective SP&M programs.<br />

•Describes the life cycle of SP&M programs.<br />

•Explains how to identify and solve problems with various approaches to SP&M.<br />

•Lists the requirements and key steps for a fifth-generation approach to SP&M.<br />

•Defines competencies and explains how they are used in SP&M.<br />

•Describes how to conduct and use competency identification studies for SP&M.

This page intentionally left blank

C H A P T E R 1<br />

WHAT IS SUCCESSION PLANNING<br />

AND MANAGEMENT?<br />

Six Ministudies: Can You Solve These Succession Problems?<br />

How is your organization handling succession planning and management<br />

(SP&M)? Read the following vignettes and, on a separate sheet, describe how<br />

your organization would solve the problem presented in each. If you can offer<br />

an effective solution to all the problems in the vignettes, then your organization<br />

may already have an effective SP&M program in place; if not, your organization<br />

may have an urgent need to devote more attention to the problem of<br />

succession.<br />

Vignette 1<br />

An airplane crashes in the desert, killing all on board. Among the passengers<br />

are top managers of Acme Engineering, a successful consulting firm. When the<br />

vice president of human resources at Acme is summoned to the phone to<br />

receive the news, she gasps, turns pale, looks blankly at her secretary, and<br />

breathlessly voices the first question that enters her mind: ‘‘Now who’s in<br />

charge?’’<br />

Vignette 2<br />

On the way to a business meeting in Bogota, Colombia, the CEO of Normal<br />

Fixtures (maker of ceramic bathroom fixtures) is seized and is being held for<br />

ransom by freedom fighters. They demand 1 million U.S. dollars in exchange<br />

for his life, or they will kill him within 72 hours. Members of the corporate<br />

board are beside themselves with concern.<br />

Vignette 3<br />

Georgina Myers, supervisor of a key assembly line, has just called in sick after<br />

two years of perfect attendance. She personally handles all purchasing and<br />

7

8 B ACKGROUND I NFORMATION A BOUT S UCCESSION PLANNING AND M ANAGEMENT<br />

production scheduling in the small plant, as well as overseeing the assembly<br />

line. The production manager, Mary Rawlings, does not know how the plant<br />

will function in the absence of this key employee, who carries in her head<br />

essential, and proprietary, knowledge of production operations. She is sure<br />

that production will be lost today because Georgina has no trained backup.<br />

Vignette 4<br />

Marietta Diaz was not promoted to supervisor. She is convinced that she is a<br />

victim of racial and sexual discrimination. Her manager, Wilson Smith, assures<br />

her that that is not the case. As he explains to her, ‘‘You just don’t have the<br />

skills and experience to do the work. Gordon Hague, who was promoted,<br />

already possesses those skills. The decision was based strictly on individual<br />

merit and supervisory job requirements.’’ But Marietta remains troubled. How,<br />

she wonders, could Gordon have acquired those skills in his previous nonsupervisory<br />

job?<br />

Vignette 5<br />

Morton Wile is about to retire as CEO of Multiplex Systems. For several years<br />

he has been grooming L. Carson Adams as his successor. Adams has held the<br />

posts of executive vice president and chief operating officer, and his performance<br />

has been exemplary in those positions. Wile has long been convinced<br />

that Adams will make an excellent CEO. But, as his retirement date approaches,<br />

Wile has recently been hearing questions about his choice. Several<br />

division vice presidents and members of the board of directors have asked him<br />

privately how wise it is to allow Adams to take over, since (it is whispered) he<br />

has long had a high-profile extramarital affair with his secretary and is rumored<br />

to be an alcoholic. How, they wonder, can he be chosen to assume the top<br />

leadership position when he carries such personal baggage? Wile is loathe to<br />

talk to Adams about these matters because he does not want to police anyone’s<br />

personal life. But he is sufficiently troubled to think about initiating an executive<br />

search for a CEO candidate from outside the company.<br />

Vignette 6<br />

Linda Childress is general manager of a large consumer products plant in the<br />

Midwest. She has helped her plant weather many storms. The first was a corporate-sponsored<br />

voluntary early retirement program, which began eight years<br />

ago. In that program Linda lost her most experienced workers, and among its<br />

effects in the plant were costly work redistribution, retraining, retooling, and

What Is Succession Planning and Management?<br />

9<br />

automation. The second storm was a forced layoff that occurred five years ago.<br />

It was driven by fierce foreign competition in consumer products manufacture.<br />

The layoff cost Linda fully one-fourth of her most recently hired workers<br />

and many middle managers, professionals, and technical employees. It also<br />

led to a net loss of protected labor groups in the plant’s workforce to a level<br />

well below what had taken the company ten years of ambitious efforts to<br />

achieve. Other consequences were increasingly aggressive union action in the<br />

plant; isolated incidents of violence against management personnel by disgruntled<br />

workers; growing evidence of theft, pilferage, and employee sabotage;<br />

and skyrocketing absenteeism and turnover rates.<br />

The third storm swept the plant on the heels of the layoff. Just three years<br />

ago corporate headquarters announced a company-wide Business Process Reengineering<br />

program. Its aims were to improve product quality and customer<br />

service, build worker involvement and empowerment, reduce scrap rates, and<br />

meet competition from abroad. While the goals were laudable, the program<br />

was greeted with skepticism because it was introduced so soon after the layoff.<br />

Many employees—and supervisors—voiced the opinion that ‘‘corporate headquarters<br />

is using Business Process Reengineering to clean up the mess they<br />

created by chopping heads first and asking questions about work reallocation<br />

later.’’ However, since job security is an issue of paramount importance to<br />

everyone at the plant, the external consultant sent by corporate headquarters<br />

to introduce Business Process Reengineering received grudging cooperation.<br />

But the Business Process Reengineering initiative has created side effects of its<br />

own. One is that executives, middle managers, and supervisors are uncertain<br />

about their roles and the results expected of them. Another is that employees,<br />

pressured to do better work with fewer resources, are complaining bitterly<br />

about compensation or other reward practices that they feel do not reflect<br />

their increased responsibilities, efforts, or productivity. And a fourth storm<br />

is brewing. Corporate executives, it is rumored, are considering moving all<br />

production facilities offshore to take advantage of reduced labor and employee<br />

health-care insurance costs. Many employees are worried that this is really not<br />

a rumor but is, instead, a fact.<br />

Against this backdrop, Linda has noticed that it is becoming more difficult<br />

to find backups for hourly workers and ensure leadership continuity in the<br />

plant’s middle and top management ranks. Although the company has long<br />

conducted an annual ‘‘succession planning and management’’ ritual in which<br />

standardized forms, supplied by corporate headquarters, are sent out to managers<br />

by the plant’s human resources department, Linda cannot remember<br />

when the forms were actually used during a talent search. The major reason,<br />

Linda believes, is that managers and employees have rarely followed through<br />

on the Individual Development Plans (IDPs) established to prepare people for<br />

advancement opportunities.

10 B ACKGROUND I NFORMATION A BOUT S UCCESSION PLANNING AND M ANAGEMENT<br />

Defining Succession Planning and Management<br />

As the vignettes above illustrate, organizations need to plan for talent to assume<br />

key leadership positions or backup positions on a temporary or permanent<br />

basis. Real-world cases have figured prominently in the business press in<br />

recent years. (See Exhibits 1-1 and 1-2.)<br />

Among the first writers to recognize that universal organizational need was<br />

Henri Fayol (1841–1925). Fayol’s classic fourteen points of management, first<br />

enunciated early in the twentieth century and still widely regarded today, indicate<br />

that management has a responsibility to ensure the ‘‘stability of tenure of<br />

personnel.’’ 1 If that need is ignored, Fayol believed, key positions would end<br />

up being filled by ill-prepared people.<br />

Succession planning and management (SP&M) is the process that helps<br />

ensure the stability of the tenure of personnel. It is perhaps best understood<br />

as any effort designed to ensure the continued effective performance of an<br />

organization, division, department, or work group by making provision for the<br />

development, replacement, and strategic application of key people over time.<br />

Succession planning has been defined as:<br />

a means of identifying critical management<br />

positions, starting at the levels of project manager<br />

and supervisor and extending up to the<br />

highest position in the organization. Succession<br />

planning also describes management<br />

positions to provide maximum flexibility in<br />

lateral management moves and to ensure that<br />

as individuals achieve greater seniority, their<br />

management skills will broaden and become<br />

more generalized in relation to total organizational<br />

objectives rather than to purely departmental<br />

objectives. 2<br />

Succession planning should not stand alone. It should be paired with succession<br />

management, which assumes a more dynamic business environment.<br />

It recognizes the ramifications of the new employment contract, whereby corporations<br />

no longer (implicitly) assure anyone continued employment, even<br />

if he or she is doing a good job. 3<br />

An SP&M program is thus a deliberate and systematic effort by an organization<br />

to ensure leadership continuity in key positions, retain and develop intellectual<br />

and knowledge capital for the future, and encourage individual<br />

advancement. Systematic ‘‘succession planning occurs when an organization<br />

adapts specific procedures to insure the identification, development, and longterm<br />

retention of talented individuals.’’ 4<br />

Succession planning and management need not be limited solely to man-

What Is Succession Planning and Management?<br />

11<br />

Exhibit 1-1. How General Electric Planned the Succession<br />

Good news, bad news.<br />