Spring 2006 Sisyphus - St. Louis University High School

Spring 2006 Sisyphus - St. Louis University High School

Spring 2006 Sisyphus - St. Louis University High School

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SISYPHUS<br />

The <strong>St</strong>. <strong>Louis</strong> U. <strong>High</strong> Magazine of Literature and the Arts<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> ’06<br />

LITERARY EDITORS<br />

Tony Bertucci<br />

Ben Farley<br />

Kyle Kloster<br />

Jake Kessler<br />

Joe Milner<br />

Paul Robbins<br />

Joe Lauth<br />

Jim Santel<br />

Dave Spitz<br />

ART EDITORS<br />

Nick Jacobs<br />

Joel Westwood<br />

Tyler Pey<br />

LAYOUT EDITOR<br />

Tim Huether<br />

MODERATORS<br />

Frank Kovarik<br />

Rich Moran<br />

Manuscripts are considered anonymously.<br />

We regret that we received more<br />

fine submissions than we could publish.<br />

Thanks to all those who offered their writing<br />

and artwork for consideration.<br />

Special thanks to Joan Bugnitz, John Mueller, & Mary Whealon.

2<br />

Si s y p h u s<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> ’06<br />

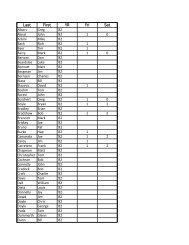

Table of Contents<br />

Cover artwork by David Rhoads, design by Joel Westwood<br />

Masthead photography by Matt Nahlik<br />

Borders artwork by Nick Jacobs<br />

3 Checkmate, poetry by Noah Mitchell<br />

4 To Suffer and Die Without Due<br />

Resurrection, prose by Tony Bell<br />

5 photography by Nick Niehaus<br />

6 At Sunrise, fiction by Alex Orf<br />

7 Ignorance is Bliss, poetry by Kingsley<br />

Uwalaka<br />

7 photography by Kevin Casey<br />

8-11 White Houses, fiction by Ben Farley<br />

8 photography by Matt Nahlik<br />

11 artwork by Peter Kidd<br />

12 From Boy to Man and Back Again, poetry<br />

by Shane Lawless<br />

13 Desert, fiction by Henry Goldkamp<br />

13 photography by Anthony Sigillito<br />

14-15 Attention, fiction by Jonathan E. D.<br />

Huelman<br />

14 photography by <strong>Louis</strong> Nahlik<br />

15 artwork by <strong>St</strong>ephen Kelley<br />

16 Response to an age that finds it pleasing<br />

to overuse “random” and to misuse<br />

“abstract,” poetry by Henry Goldkamp<br />

17-20 Just Like Old Times, fiction by Victor<br />

J. Kessler<br />

18 photography by Henry Goldkamp<br />

19 photography by Henry Goldkamp<br />

20 photography by Alex Grman<br />

21-22 Sunset, fiction by Peter Lucier<br />

22 photography by Henry Goldkamp<br />

23 Gravedigger, fiction by Kyle Kloster<br />

24-28 Metro, fiction by Tony Bertucci<br />

24 photography by <strong>Louis</strong> Monnig<br />

25 photography by <strong>Louis</strong> Nahlik<br />

26 photography by Matt Nahlik<br />

27 artwork by <strong>Louis</strong> Monnig<br />

29 Argumentum ad Sapientem, poetry by Dan<br />

Yacovino<br />

29 photography by Sean O’Neil<br />

30-31 <strong>St</strong>uck in Fast-Forward, poetry by Shane<br />

Lawless<br />

31 photography by Henry Goldkamp<br />

32 artwork by Niall Kelleher<br />

33 Fear, poetry by Timlin Glaser<br />

34-36 Late, non-fiction by Jim Santel<br />

34 photography by Kevin Casey<br />

35 photography by Sean O’Neil<br />

36 photography by Sean O’Neil<br />

37 Lost, poetry by Shane Lawless<br />

38-42 Prayer, fiction by Matt Wilmsmeyer<br />

40 photography by Tim Seltzer<br />

41 photography by Kyle Kloster<br />

43 Le Mont-Saint-Michel, poetry by Tony Bell<br />

44-45 On Mary Oliver’s “Wild Geese,” essay<br />

by Kyle Kloster<br />

45 Grass, poetry by Adam Archambeault<br />

46 <strong>Spring</strong>time, poetry by <strong>St</strong>eve Behr<br />

46 artwork by Dave Bosch<br />

47-49 Waking Up, fiction by Timo Kim<br />

49 artwork by Matt Ampleman<br />

50 Embrace, poetry by Will Turnbough<br />

50 photography by Anthony Sigillito<br />

51-54 Excerpt from The Endeavor’s Compass,<br />

fiction by David Spitz<br />

55 Being Below Zero Makes You Think,<br />

poetry by Jonathan E. D. Huelman<br />

56-58 The Damn Armrest, fiction by Connor Cole<br />

58 artwork by Tyler Pey<br />

59 Like, Poetry and <strong>St</strong>uff, poetry by<br />

Henry Goldkamp<br />

60 An Ode to My Ballpoint Pen, poetry by<br />

Thad Winker<br />

61-62 Long Dark Hallways and Cedar Closets,<br />

narrative by T. J. Keeley<br />

63 Spitting Image, poetry by Timlin Glaser<br />

63 artwork by Dom Palumbo<br />

64 The Turn, fiction by Tony Bertucci

Ch e c k m a t e<br />

Noah Mitchell<br />

Why, pawn, are you weak,<br />

so frail and disposable,<br />

exposable, expendable,<br />

a bowling pin<br />

so edible to the will<br />

of a higher, towering power?<br />

Do his orders deafen<br />

the squeaks of revolution<br />

peeping through the curved crevice<br />

on the crown to your captivity?<br />

Your goal<br />

to lose identity pinned with such brevity,<br />

3<br />

Charge, hope, hop to end…

4<br />

To Su f f e r a n d<br />

Die Wi t h o u t Du e<br />

Re s u r r e c t i o n<br />

Tony Bell<br />

Cramming into my dad’s crummy ’83 Ford<br />

Escort every morning around sunrise, that<br />

disorienting time when the sun leaves hints of<br />

itself in the sky and on the pavement, shining<br />

through the trees that canopied Francisca Lane,<br />

Jake or I would co-pilot the mumbling stick shift<br />

with Dad’s hand on top, and we’d set off for<br />

Jeff and Joe’s house. The journey was so short<br />

that, on cold winter mornings, we’d arrive in<br />

front of their sloping front yard before the heat<br />

even started to thaw our fingers. Although so<br />

near, the Marxkors’ house seemed like another<br />

world. Set up on a proud hill, its yellow siding<br />

would always beam with the coming of first<br />

light, illuminating the differences between my<br />

side street Francisca and their Lindsay Lane.<br />

They woke up to cars waiting at a stoplight<br />

and a 7-Eleven across the street. But with this<br />

lack of solitude came many great things, such<br />

as the presence of the Buddhist monk around<br />

9:00 each morning.<br />

“Boobist! Boobist! All the way from<br />

Boobistland!” we’d shout into the window pane<br />

of the front door, our noses pressed hard against its<br />

smooth but smudgy surface. He would walk with<br />

the utmost serenity, the smallest shuffling steps,<br />

to the end of Lindsay Lane, where it cornered<br />

with Shackelford, and then back again into the<br />

depths of our imaginations. Oh, the places that he<br />

came and went! We’d imagine him crossing vast<br />

oceans and massive expanses of land in his orange<br />

robes, tanning to a nice brown before getting to<br />

the corner of Lindsay Lane and Shackelford,<br />

and turning back around. Jeff, Joe and I would<br />

ponder the purpose of his journey and come to<br />

respect that cement corner as a haven for the<br />

spiritually inclined. It seemed that at this corner<br />

he received some sort of enlightenment before<br />

turning around and returning to his antipodal<br />

home.<br />

Now that I look back on it, I imagine the<br />

Marxkors’ house as my second home, the all-encompassing<br />

destination each morning when my<br />

parents went to work. John and Cheryl Marxkors<br />

were my surrogate parents. John was my soccer<br />

and baseball coach, and Cheryl looked after my<br />

brother and me, along with her own four children,<br />

Matt, Melissa, and the twinners, Jeff and Joe, my<br />

two best friends throughout all of adolescence,<br />

from 7:00 until 2:00 each day of the week except<br />

Thursday, when my mom was off work. It was in<br />

this home that I first experienced many elements<br />

of the world—death, divorce, and some sort of<br />

limbo.<br />

The weird neighbors on the corner of Lindsay<br />

Lane and Shackelford had flowers planted<br />

in potting soil in a toilet in their backyard.<br />

Daisies, I think. When I accidentally kicked<br />

our soccer ball over their fence, I’d be forced<br />

to enter this world of eerie wonder. Dropping<br />

down slyly onto the crackling summer grass,<br />

dried out and neglected, I’d carefully pass the<br />

mystical assortment of gnomes in their red hats<br />

and green shirts and enter the neighbors’ sad<br />

attempt at a garden through a creaky, rusted<br />

iron gate. It looked more like a jungle than a<br />

garden, and it was all I could do not to sweat<br />

from its tropical humidity and the anxiety that<br />

steamed up inside of me. I would quickly rummage<br />

through the weeded overgrowth with the<br />

goalie gloves I borrowed from Jeff, who usually<br />

played keeper, until I came across a fragment of<br />

shiny white plastic, a piece of a puzzle which<br />

formed our soccer ball. After quickly retrieving<br />

it from the weeds that already started to<br />

engulf it, I retraced my steps out of the garden<br />

and past the goldfish pond, saluting the hearty<br />

cluster of gnomes before climbing back over<br />

the chain-link fence.

During winter the goldfish pond froze. No<br />

attempt was made to retrieve the three goldfish.<br />

On some of the warmer days of Christmas Break,<br />

Jeff, Joe and I would bundle up according to<br />

Cheryl’s winter regulations, and we’d stand with<br />

our mittened hands linked in the chained-link<br />

fence, lamenting the frozen goldfish. I don’t think<br />

we fully appreciated the goldfish until they were<br />

frozen. Then one day we went outside in jeans<br />

and sweatshirts, Cheryl’s lesser regulations for<br />

a coming spring, and the water bubbled with<br />

the liveliness of three goldfish. They had been<br />

resurrected, like Lazarus, we’d later learn, saved<br />

and redeemed by the grace of God.<br />

“He takes care of animals too, you know,”<br />

said Melissa, shocked by our elation over the<br />

resurrection of three goldfish. Her room was<br />

covered in Precious Moments porcelain and<br />

posters. “I knew they’d come back because I’ve<br />

seen it before,” she said, stressing the I’s in all<br />

of her wisdom and experience. She faithfully<br />

believed in the saving right hand of the Father,<br />

and we, mere first-graders, had not yet learned<br />

prayers.<br />

Four weeks later Melissa’s best friend, Megan<br />

McKeating, died on our grade school’s gym<br />

floor. Apparently the hole in her heart that was<br />

supposed to be plugged came unplugged during<br />

the sixth lap of an easy calisthenics workout, and<br />

she tumbled to the dusty floor before the blue<br />

and yellow home team benches. She never got<br />

up. Megan’s parents cursed the school, knowing<br />

it wasn’t the school’s fault, and Melissa cursed<br />

God. The next morning at the Marxkors’ house,<br />

Melissa skipped breakfast. She skipped school,<br />

and Cheryl gave her time to cope, holding Melissa<br />

preciously in her arms throughout the day<br />

while we learned to read simple subject-verb<br />

combinations and dressed down for dodge ball in<br />

gym class. When Jeff, Joe and I came home after<br />

school, Melissa was in the backyard looking at<br />

the three goldfish, teary-eyed, her delicate fingers<br />

fixed within the gaping holes of the chained-link<br />

fence. We watched from afar as she bent her<br />

head forward, touching it to the cold metal of<br />

the fence, wondering, I guess, how God could<br />

use his divine finger to warm the goldfish pond<br />

with new life but not to plug the hole in her best<br />

friend’s heart.<br />

Megan’s death cut deep gashes into the<br />

<strong>St</strong>. Ferdinand parish community. My parents<br />

sent flowers to the funeral home. It was on a<br />

Wednesday, so my mom was unable to attend.<br />

Cheryl went with Melissa, and we were watched<br />

by Matt, our school day cut short by Megan’s<br />

absence. On that warm day at the beginning of<br />

spring, Jeff, Joe and I echoed the movements<br />

Melissa made in the backyard. We curled our kid<br />

fingers through the chained-link fence, looking<br />

at each other with the kinds of faces we had seen<br />

on the Precious Moments porcelains, tight-lipped<br />

and droopy-eyed, shocked that God wouldn’t at<br />

least try to mend the holes.<br />

Halfway through that summer, the last summer<br />

that I would have to be watched over by a<br />

babysitter, Cheryl and John filed for divorce. I<br />

wasn’t there when they told the four children, but<br />

I imagine it happening in their master bedroom,<br />

where we once watched home videos of both of<br />

our families on vacation in Gulf Shores.<br />

John moved into an apartment about five<br />

minutes down Shackelford. The four children<br />

went to see him on the weekends. Sometimes<br />

when neither parent had the time to take them to<br />

or from their new home in the apartment complex,<br />

they had to ride the bus. I saw them once, on the<br />

way to my grandma’s house. Jeff and Joe waved,<br />

Melissa stared sadly ahead, indifferent to the<br />

honking or the honker, and Matt reluctantly led<br />

them on, walking to the bus stop at the corner<br />

of Shackelford and Lindsay Lane.<br />

Ni c k Ni e h a u s<br />

5

6<br />

At Su n r i s e<br />

Alex Orf<br />

On the very edge of the horizon sat the faintest<br />

hint of pink, defining the previously<br />

formless skyline. Rachel and I stared intently at<br />

it, as if believing that our collective focus would<br />

accelerate its spread. Buried under a mess of<br />

blankets, we sat huddled together, backs pressed<br />

against the gray expanse of the stone reservoir<br />

in Reservoir Park.<br />

“Won’t be long now,” Rachel muttered. She<br />

smiled at me, a bright smile that caught what little<br />

light we had at just the right angle, giving her<br />

face a warm orange glow. But soon her lip began<br />

to tremble, and she pulled a patchwork quilt up<br />

over her nose, curling into the fetal position and<br />

looking out towards the light.<br />

We discovered the reservoir—or rather we<br />

had been introduced to it—on a night that had<br />

been going nowhere. Out of feasible pursuits and<br />

desperate to find somewhere, anywhere, to waste<br />

our night, we followed a friend’s suggestion to<br />

see the view. Eight of us went that first night in<br />

February, and as we stood on the hill, backs to the<br />

reservoir to escape the wind, Rachel and I were<br />

left speechless by the brilliance of our city, neon<br />

and fluorescent and radiant. From that perch, the<br />

fast food chains and skyscrapers and dive bars<br />

all meshed into a harmony of urban beauty.<br />

“Can we keep it?” Rachel had asked hopefully,<br />

as if the skyline were a stray puppy.<br />

“Well, there’s no harm in trying,” I replied<br />

through an amused grin, and in the month since<br />

we had stolen away to visit Reservoir Park<br />

whenever we could spare a minute. It became<br />

a sanctuary, hallowed ground. Rachel said it<br />

was the location, inside the city but far enough<br />

removed to observe comfortably, and I had to<br />

agree with her. There was a balance to it; it felt<br />

right.<br />

We could see red now, with orange in tow.<br />

The buildings in the distance began to gain<br />

dimension and color. I inhaled deeply, and the<br />

sharp, frigid air scratched my throat, provoking<br />

a cough. “You had to pick the coldest damn day<br />

of the break, didn’t you? I’m going to catch my<br />

death of frostbite if we’re out here much longer,”<br />

I croaked at her mock-contemptuously.<br />

She flashed a wicked smile for a moment,<br />

then contorted her cheerful face into a stoic<br />

shell and shrugged. “I don’t see where that’s<br />

my problem,” she quipped, deadpan. “No one<br />

forced you to come. Besides, this is the clearest<br />

morning we’ve….” She trailed off when the<br />

first flicker of golden yellow slipped above the<br />

horizon and caught her eye.<br />

It started suddenly, rising up to a single<br />

point before stretching out along the horizon.<br />

When the sun broke the surface, its rich, heavy<br />

light trickled through the city streets, expanding<br />

and creeping up the skyscrapers. Rachel slid in<br />

close and fumbled under the blankets to find my<br />

hand. As the sun fought to clear the horizon, the<br />

light began advancing faster and faster until it<br />

became a veritable flood. Only moments after<br />

the sun separated itself from land the light hit<br />

us and, for that brief second, the buildings, the<br />

parks, Rachel and I—the whole city froze, gilded<br />

in shimmering red-orange. I heard Rachel take a<br />

breath, and the city slid back into its grays, tans,<br />

and reds.<br />

Resting my head against the concrete wall,<br />

I looked over at her inquisitively. She gave me<br />

a wide-eyed, almost startled look, and I couldn’t<br />

help but smile. “So,” she said softly, airily. “What<br />

should we do today?”<br />

What couldn’t we do?

Ig n o r a n c e is Bl i s s<br />

Kingsley Uwalaka<br />

It’s hard to notice.<br />

It’s very subtle.<br />

But it’s there…<br />

The glow in a child’s eyes,<br />

The glow of naivety,<br />

The glow of curiosity for the world around him.<br />

I want it back.<br />

I want to go back.<br />

I want to feel again.<br />

I want to swim upstream again,<br />

Not worrying about river-born germs,<br />

How stupid I must look,<br />

Or that I’m getting nowhere.<br />

I just want to enjoy the water again.<br />

Ke v i n Ca s e y<br />

7

8<br />

Wh i t e Ho u s e s<br />

Ben Farley<br />

hopped out the side door and onto the concrete<br />

steps of my house. The damp humidity<br />

I<br />

and glaring sun reminded me: It’s July in <strong>St</strong>.<br />

<strong>Louis</strong>. <strong>St</strong>aring straight ahead, I looked longingly<br />

across Bryncastle Place to the open field<br />

spread across three backyards in my South<br />

County neighborhood. Manicured Scottsdale<br />

grass sloped gently downward across the field.<br />

To my right, Castlegate <strong>St</strong>reet led down a dark<br />

alley, scarred with many potholes and black tar<br />

streaks over the many years since it had been<br />

built in the 1950s. On both sides of the road,<br />

dark-brick homes stuck out of the ground, surrounded<br />

by gnarling, twisting trees.<br />

The “old neighborhood” frightened me with<br />

its lonely darkness. I never saw any of the houses<br />

of the old neighborhood up close. Once, when I<br />

was five, I walked across the street and snuck up<br />

to the building closest to my house. I never saw<br />

much of the building, nor any of the other ones,<br />

because of the high wooden fences that encased<br />

them. They must have been hiding something,<br />

which is why I walked over that one day. But<br />

before I could come close to the truth, a dog began<br />

roaring from behind the fence. I jumped away<br />

from the lamp post I had hidden behind and ran<br />

back home, crouching underneath the slide in my<br />

backyard. Today, the old neighborhood looked<br />

particularly evil, with long shadows underneath<br />

the dense trees.<br />

To the left of my house, Bryncastle continued<br />

and made a right angle turn away from me. Down<br />

there, the “new neighborhood,” barely ten years<br />

old, began. The shiny aluminum-sided homes,<br />

white-washed and perfectly square, arose from<br />

the ground. The roofs, gray as dark rain clouds,<br />

rose to the majestic peaks that make suburbanites<br />

feel superior to flat-roofed apartment dwellers.<br />

I envied all the rich kids, wearing Nike shoes<br />

and Abercrombie shirts, who lived in those pure<br />

white houses. I still wore the same Sambas my<br />

mom bought me three years ago. We lived in<br />

a house awkwardly placed at the corner of the<br />

intersection of Castlegate and Bryncastle—added<br />

in the seventies and different from all the others.<br />

That pretty much summed up my existence. I<br />

stuck out of any group like a bruised apple. My<br />

love of National Geographic and inability to<br />

talk about pop culture made me awkward even<br />

around the small group of friends I had. Not many<br />

nine-year-olds are interested in Grant’s improbable<br />

victory over the Rebels at Chattanooga. I<br />

knew about Alexander’s victory at Guagamela,<br />

Bismarck’s realpolitik philosophy, and Keynesian<br />

economics. To be short, I was Ted Koppel<br />

in a ten-year-old’s body. The one normal thing<br />

in life was soccer. I walked down my driveway<br />

and towards the open field.<br />

The field formed a long rectangle, perfect<br />

for a soccer game. Almost everyday during the<br />

summer, I would walk in the late afternoon, along<br />

with my little brother who skipped and pestered<br />

me along the way. On this day, I could see a whole<br />

group forming. Kevin, a year older than me, with<br />

a shock of reddish-blonde hair and a tall, athletic<br />

build, was the leader. He always captained a<br />

team, usually leading the league in scoring. The<br />

Rozencrantz twins, two years younger than me,<br />

also ran to join the games. The Guild boys also<br />

played. Kevin told me the oldest, Shawn, had a<br />

crush on Jennifer. I didn’t understand why he<br />

wanted to crush her, but I kept watch on him<br />

in case he tried. Jennifer, my cousin two years<br />

older than me, was the greatest person I’d ever<br />

met. Unencumbered by life’s pains, she walked<br />

through life confident, sure of herself.<br />

“Countdown.... Ten...nine...eight...!” Jennifer<br />

began the infamous countdown preceding<br />

her booming penalty kicks. In front of the goal<br />

stood my team, all of us holding our sweaty<br />

hands over our crotches. Jennifer would launch<br />

those missiles towards us and we’d dive out of<br />

the way, unwilling to stand against her shot...<br />

against her.<br />

“...two...one...blast off!” I felt the rush of

warm air as the ball whizzed by, inches from my<br />

bulky hearing aid, and into the shredded net. We<br />

all picked ourselves up, incredulous about what<br />

we saw now for the 197th time, and set the ball<br />

up at half-line. I never felt better than when I<br />

played soccer. I was part of something, with other<br />

people. I dissolved into the collective identity of<br />

the team, losing my own personality. But after<br />

the game, I had to return to my personality—who<br />

I really was.<br />

Don’t feel different; feel special,” Jennifer<br />

“ gently whispered as she glided her hand<br />

through my mangy hair as we sat in the family<br />

room after that Saturday’s game.<br />

“That’s crap,”<br />

I replied with the<br />

new word I heard<br />

Dad yell as he<br />

missed the nail<br />

with his hammer<br />

last week.<br />

“Don’t say<br />

that!”<br />

“Well it’s<br />

true, it’s crap...<br />

crap, crap, crap,<br />

crap! “<br />

“Why do you<br />

say that?”<br />

“’Cause life<br />

sucks!”<br />

“No, it doesn’t...”<br />

“YES, IT DOES!” Now the whimpering tears<br />

came. “I don’t have...friends and...I...I’m…different<br />

and...I hate myself.”<br />

“Why?”<br />

“Everyone else goes and plays and has fun.<br />

Why can’t I do that? I want to be normal. I’d<br />

give up this stupid ‘gifted brain’ just to be like<br />

everyone else.” I sighed, finally able to admit<br />

the hopelessness of my life.<br />

“Holden, come with me.”<br />

She pulled my sullen body off the couch and<br />

we walked across the plush carpet of her living<br />

room. The sun burned my eyes as we stepped<br />

out of her white house and onto Bryncastle. We<br />

walked down the street, completely abandoned<br />

except for the Rozencrantz twins racing each<br />

other on rollerblades. They sailed right by us<br />

in a whirling cloud of fumes. Down the street,<br />

Tim knocked his twin, Tom, to the ground and<br />

grabbed hold of the finish line, the half knocked<br />

over “25 MPH” sign. He jumped furiously in joy,<br />

as Tom cried for Mommy near the sewer. Tim’s<br />

skates slid out from under and his ass hit the<br />

ground. He sat dumbfounded for a second, then<br />

joined in his brother’s cries for Mommy. Good, at<br />

least some things are fair. Jennifer and I walked<br />

down the street and turned left onto the soccer<br />

Mat t Na h l i k<br />

field. I instantly<br />

took my shoes<br />

and socks off,<br />

wanting to feel<br />

the tingly green<br />

grass between<br />

my toes. I forgot<br />

all my problems,<br />

even why<br />

we were there.<br />

I was happy...<br />

smiling...unscarred.<br />

“Holden,”<br />

she gently spoke<br />

as we stood in<br />

the middle of<br />

the field, “look at those houses.” I stared at the<br />

backs of all the white houses. I could see hers<br />

down the block.<br />

“That’s you, Holden. Or at least that’s where<br />

you’ll be. Someday, that brain of yours is going<br />

to make you great and rich. People will love you.<br />

You won’t have any worries. Just white walls<br />

and big screen TV’s.”<br />

I almost said “That’s crap,” but there was<br />

something about her, about her voice, her confidence,<br />

that cajoled me into believing. Plus, I<br />

thought she had grown sick of the incessant flowing<br />

of “crap” from my mouth. Everyone told me<br />

9

10<br />

I had a bright future. I guess that’s what happens<br />

when you can recite all the presidents in order<br />

and name the atomic number of plutonium. But<br />

I never felt like the white houses, except now,<br />

with Jennifer.<br />

“Now look at those houses.” She pointed<br />

toward the row of houses in the old neighborhood.<br />

“They’re all ugly and beat up. That’s what<br />

you’re doin’ to yourself. Don’t end up like one<br />

of those homes. You’ve got a future of white<br />

homes, stick to it.”<br />

“Where are you, Jennifer?”<br />

She shrugged without<br />

care. “Oh, I’m already at<br />

those white houses. Never<br />

had to deal with anything<br />

bad or nothing. You don’t<br />

have to either. All you have<br />

to do is stay up, don’t worry.<br />

It’ll all work out.”<br />

Well, now I felt better.<br />

Jennifer always made me<br />

feel better. Nothing ever<br />

bothered her. She never<br />

cried or whined about anything.<br />

She avoided anything<br />

bad and upsetting. I wondered<br />

if that’s what it felt<br />

like to live in one of those<br />

white houses—no worries<br />

or problems. Jennifer had it easy.<br />

What’s leukemia?” I asked my mom, tears<br />

rising from the bottom of her eyes.<br />

“ “It’s a cancer.”<br />

“But Jennifer can’t have cancer, she’s not<br />

old!”<br />

The only people I ever saw with cancer<br />

were old aunts and uncles. My uncle Fenton<br />

had died when I was five. My parents told me<br />

he had stomach cancer. I wondered why he had<br />

swallowed a can. This was a time before I knew<br />

the reality of cells slaughtering themselves in a<br />

senseless war. I stood in the parlor (why do old<br />

people always have parlors?) in a starchy white<br />

shirt as the tall man in the same starchy white shirt<br />

pronounced my uncle dead. I asked if I could ride<br />

in the ambulance, since I wanted to be a doctor.<br />

For some reason, the paramedic picked me up<br />

and took me into the ambulance. I was so excited<br />

to be in there, since I had never heard of anyone<br />

else riding in an ambulance. He showed me all<br />

the machines and tools inside the ambulance.<br />

He walked to the front to talk to the driver for a<br />

Pe t e r Ki d d<br />

second, and that’s when I<br />

lifted up the sheet covering<br />

my Uncle Fenton. I stood<br />

there, staring into the calm,<br />

cold face of this old man I<br />

barely knew. Suddenly, an<br />

image of Jennifer with a<br />

cold, dead face now flew<br />

into my imagination and<br />

froze there like a movie on<br />

pause. I cried and bawled<br />

as my mother, hiding her<br />

own grief, gently rocked<br />

me back and forth.<br />

The next day, I stood<br />

outside Jennifer’s massive<br />

white house, a building<br />

cold and imposing. I saw<br />

my Uncle Fenton’s face on<br />

the aluminum siding, and<br />

rushed towards the porch.<br />

The doorbell rang, one of those artificial bells<br />

meant to convey warmth, failing miserably.<br />

“Oh, hi, Holden,” my aunt, gaunt and pale,<br />

asked without any force. She stood lifeless for a<br />

while, not looking at me, but through me. I stood,<br />

slightly trembling, unsure of what to do.<br />

“Is Jennifer...is she...can I see Jennifer?” I<br />

haltingly asked.<br />

“I’m not sure she wants to see anyone,<br />

Holden. She’s not feelin’ good. I just...”<br />

I snuck past her and walked across the plush<br />

carpet and upstairs. I walked gingerly, not wanting<br />

to disturb the deadly silence in the building.

I walked up to her door, scarred with the white<br />

streaks left behind by a torn off Madonna poster,<br />

and knocked. No answer. I knocked again.<br />

“Jennifer, are you in there?”<br />

“Whaddya want?”<br />

I just wanted to see how you’re doing?”<br />

“FINE!” followed by painful coughs.<br />

“I was just wondering... maybe you could<br />

come outside?”<br />

“No.”<br />

“But Jennifer...”<br />

“No! OK, No! I don’t want to. Why should<br />

I? I don’t have a life anymore. Or did you not<br />

hear...I got leukemia.” I could hear the sobs<br />

through the thin wooden door. “Just leave me<br />

alone, I don’t want to be near anyone.”<br />

I ran down the stairs, banging my knee off<br />

the post at the top of the stairs, and ran outside. I<br />

ran past the Rozencrantz boys ding-dong-ditching<br />

the neighbors, and collapsed on the soccer<br />

field.<br />

I cried. I screamed at God, the old man<br />

with a beard who always answered our prayers<br />

if we tried hard enough, or at least that’s what<br />

Aunt Mary said. I looked over to the ugly brick<br />

houses, tears flowing down my face. Somewhere<br />

in my psyche, I blamed those buildings. I saw<br />

the house, the one that scared me when I was<br />

five. I wasn’t scared now, just angry. I hated the<br />

darkness of the house, the loneliness that I felt<br />

once again. Now that darkness had overtaken<br />

Erin. The high, wooden fence rose up, not allowing<br />

any healing light into the darkness. I hated<br />

the house, the darkness, the loneliness, myself.<br />

I couldn’t handle it anymore.<br />

I lifted my body off the sod and ran towards<br />

the fence like a bull towards a matador. I stepped<br />

on my ankle as I charged forward, but ignored the<br />

pain. I leapt up off my left foot and slammed my<br />

right leg, followed by the left, into the surprisingly<br />

strong wooden fence. I fit the fence line<br />

under my arms and awkwardly pinned myself<br />

against the barrier, ready to curse at the evil that<br />

the house was. I breathed in a mighty breath...<br />

and saw a girl in a pink dress playing near a<br />

revered oak tree. <strong>St</strong>artled, she looked up at me<br />

with a terrified face that quickly dissolved into<br />

a bright, toothy smile. Her puffy cheeks rose up<br />

and turned crimson with happiness. She began to<br />

giggle and flail her arms in the way that toddlers<br />

do.<br />

I just hung there, stupefied while I watched<br />

this beautiful girl playing with a Tickle-Me-Elmo<br />

doll at the bottom of a wooden, hand-made playground.<br />

She cooed and laughed at me, showing<br />

the hope of a new life. After a few minutes, she<br />

rose up haltingly, gathered up her treasures, and<br />

walked toward the closed-in patio. As I lifted my<br />

eyes following her, the sun’s fading orange rays<br />

bounced off some beautiful, metal wind chimes.<br />

The sun slowly sank behind the distant church<br />

spire, and I saw beyond the brick houses a wide<br />

green field that flowed right up to the horizon.<br />

After what felt like a day, I remembered I<br />

was hanging on a wooden fence and the wood<br />

was digging into my underarms. I hopped down,<br />

landing on my twisted ankle, and sat against<br />

the fence. My brain churned with thoughts and<br />

images that I couldn’t describe. There actually<br />

was beauty in that house. Beyond it, the sun<br />

looked brighter and warmer than I ever thought.<br />

So, there’s actually hope there. Not even the old<br />

neighborhood is hopeless. What does that mean?<br />

What do I do? All that time I limped back towards<br />

the white houses. My self-absorbed anger slipped<br />

away and the real world, filled with all its pain<br />

and joy, rushed back. Looking at one of the<br />

white houses, I noticed the paint had begun to<br />

chip off the lower sidings. I looked over at the<br />

pre-assembled plastic playground and felt empty.<br />

The pure white houses, with all the nice-looking<br />

but soulless accessories, no longer seemed real<br />

to me. I looked back at the open field, the old<br />

neighborhood, the setting sun, and now knew<br />

what to do.<br />

“Jennifer,” I yelled as I hobbled along, “guess<br />

what I saw!”<br />

11

Fr o m Bo y t o Ma n a n d Ba c k Ag a i n<br />

Shane Lawless<br />

I climbed atop the mountain till I reached the peak<br />

Hoping the higher altitude would give me clear vision<br />

If I raised myself above the throngs.<br />

But all I did was lose my head in the clouds, clouding my vision.<br />

I clothed myself in the glorious sun, shining for all to see,<br />

Hoping the light would destroy any blemish on me.<br />

But all it did was blind me with brilliance while<br />

Allowing others to see my faults.<br />

12<br />

I hid my countenance behind a porcelain mask,<br />

Hoping all would admire my divine perfection.<br />

But all I did was lose my place in the crowd among other masks,<br />

Fading into the fog of obscurity.<br />

I picked up the megaphone, raising it to my mouth. I spoke,<br />

Hoping to share my inspired words with the world.<br />

But all I did was let everyone know in an echoing voice<br />

That I had nothing to say.<br />

(It’s easy for a boy to learn to be a man)<br />

Climbing down that mountain, I gazed at its majestic beauty.<br />

Tossing aside my blanket of light, I find comfort cloaked in shadows.<br />

Removing my mask, I see my imperfections as testaments to my humanity.<br />

Turning off the megaphone, I learn to find wisdom in my own silence.<br />

By descending from my lofty perch, I could see beyond the horizon.<br />

By dwelling in shadows, I outshined the sun.<br />

By displaying my disfigurements, I made myself beautiful.<br />

By discussing in whispers, I heard those secrets whispered to me.<br />

(Much harder for a man to relearn to be a boy)

De s e rt<br />

Henry Goldkamp<br />

The burning heat of the sun cascades down his<br />

weathered face, waking the sleepy drifter<br />

from his uncomfortable bed of dirt. Drenched in<br />

sweat, his tearing eyes and chafed lips burn. He<br />

can taste the salt on his tongue. Scorpion tracks<br />

surround the makeshift camp, reminding him of<br />

his first trial with the serpent. And even though<br />

he is starving, he knows he must not give into<br />

temptation for his Father’s sake. His mind starts<br />

to wander and comes to the conclusion lizards<br />

would probably not taste that bad after all, as<br />

long as they were cooked. The morning sun<br />

brings him back to reality, which, even hotter<br />

in the afternoon, is starting to beat down on his<br />

already burnt body. The exhausted man begins<br />

the daily routine of meditation and prayer to ease<br />

his weary mind, to aid his spiritual recovery.<br />

He looks towards the horizon, searching for<br />

any sign of life, any sign of shade from the<br />

blistering heat. He discovers a slightly darker<br />

spot silhouetted against the bright, blinding<br />

dirt reflecting the sunlight off in the distance.<br />

Could this be an oasis? He runs to the figure<br />

as quickly as his calloused feet can take him<br />

there. Snake skins strewn across the desert are<br />

picked up by the wind, crossing the hopeful<br />

vagabond’s path.<br />

He reaches the destination only to be disappointed—it<br />

is nothing but the corpse of a dead<br />

camel. He prays for the strength in the upcoming<br />

temptations he must face. He knows what he<br />

must do, but he also knows it will be hard. He<br />

wonders when the serpent will next challenge<br />

him again. What will the temptation be? Vultures<br />

soar overhead, thinking this man is weak and will<br />

soon be nothing more than dead flesh to prey<br />

upon. The desert breeze runs through his long<br />

brown hair, matted with sweat and dirt. Soon<br />

the wind is blowing all around him, picking up<br />

the dirt along with it, and a thick cloud of dust<br />

surrounds him. The wind suddenly stops, and<br />

all is numbingly quiet. As the dust settles, a<br />

black snake appears hissing at his feet. Its cold,<br />

unforgiving eyes peer up at him, the sense of<br />

confidence glistening in its coiled posture. With<br />

a sigh and a deep, sinking feeling in his stomach,<br />

the spiritual exile confronts the serpent.<br />

13<br />

An t h o n y Sigillito

14<br />

At t e n t i o n<br />

Jonathan E. D. Huelman<br />

It was because it was standing up so straight<br />

that he noticed it. There were many other<br />

things about an unlabeled, shining, silver aerosol<br />

can sitting conspicuously in the middle of<br />

a parking lot downtown that could have been<br />

noticed by an average middle-age, middle-class<br />

white male stepping out of his Corolla towards<br />

his miserable job in an equally miserable office<br />

complex, but he noticed it because of how it<br />

stood: nice and straight, instead of rolled over<br />

on its side as<br />

if it had fallen<br />

off a delivery<br />

truck. Defiant<br />

and gleaming<br />

in the morning<br />

sun, this nondescript<br />

can of<br />

whatever had<br />

reached out<br />

and grabbed<br />

him simply<br />

by being<br />

there. At that<br />

instant, with<br />

the door to his<br />

car hanging<br />

open and his<br />

casual-Friday-attired leg still on the floor near<br />

the pedals, he felt something that he longed to<br />

make others feel. This paltry can had done in<br />

ten milliseconds what he had been striving to<br />

do for ten years, so he took it with him.<br />

He got to his cubicle and set the can down<br />

and began to work. Work was work, and that was<br />

it. His boss was bossy, and his co-workers were<br />

really just mechanized drones fueled by coffee<br />

and chitchat. He strongly believed that nothing<br />

short of the Apocalypse would stir these simpletons’<br />

souls, not even for a moment. Nothing<br />

had ever excited them and nothing ever would,<br />

Lo u i s Na h l i k<br />

and they were fine with that. But he wasn’t fine<br />

with it; he wasn’t fine with anything about his<br />

workplace. But instead of taking drastic measures<br />

and burning the place down, he just sat there and<br />

watched as nothing happened all around him.<br />

He spent most of the morning down in the<br />

mail room laboring through the confusion of a<br />

delivery mix-up. At lunch, he took the elevator<br />

back up to his floor, and there it was. That same<br />

can was still sitting on his desk in his cubicle,<br />

staring at him. He stared back, bewildered that<br />

such a simple human creation could mock him so<br />

maliciously. He sat down facing it with his brown<br />

paper lunch sack at rest in his lap. Feeling undermined,<br />

he<br />

hunched over<br />

and demanded<br />

that the can<br />

stop. More<br />

than anything,<br />

he wanted to<br />

stop this can<br />

from unsettling<br />

his mind. He<br />

turned away<br />

in his standardissue<br />

swivel<br />

chair, laid his<br />

lunch on some<br />

open space on<br />

his desk, and<br />

began to eat,<br />

ignoring the can. As he slowly chewed his cold<br />

store-bought sandwich, he felt it boring into the<br />

back of his skull, working its way into the deepest<br />

curves of his mind. He stopped chewing to<br />

take a sip of the grape soda that would have been<br />

coffee if it weren’t for his co-workers’ need for<br />

every drop of hazelnut-flavored caffeine. As he<br />

sipped, he abruptly became disgusted with the<br />

undistinguished way he was drinking and suddenly<br />

tilted the can vertically, letting the soda<br />

cascade past his taste buds and into his throat,<br />

with some of it splashing free onto his white<br />

casual-Friday shirt.

Determination has a funny way of messing<br />

with time. This time, to his delight, it caused<br />

the clock to fly forward, making hours flash by<br />

in minutes. Since his mind was already back in<br />

his house plotting, it made sense that his body<br />

would feel an irrepressible desire to catch up to<br />

it. And so he sat in his mismatched, arid kitchen,<br />

with the can standing on his counter top. He had<br />

already planned what to do, and was now planning<br />

how to do it: when and where. His mind<br />

almost couldn’t see it coming, he was thinking<br />

so far ahead. At night, when the last neighbor’s<br />

lights had been snuffed out and the last stray dog<br />

had whined its goodnight to the bleak city moon,<br />

he would set upon the northern wall of his sad<br />

house on a deserted corner. This was the solid<br />

brick wall which would tomorrow morning face<br />

the world with the acrimonious message:<br />

s tay t u n e d f o r m o r e c o r r u p t i o n<br />

The word choice, he thought, was important.<br />

Since he was a good citizen who always voted<br />

and never spoke out, the neighbors whom the<br />

policemen would question around 9 a.m. would<br />

never suspect him of writing such an obviously<br />

political message. The blame would fall squarely<br />

on some unnamed and unnoticed emotionally<br />

challenged youth who would escape unpunished.<br />

They would never notice the commanding nature<br />

of the graffiti, and they would never even notice<br />

that they hadn’t noticed. Whether he had taken<br />

up the burden of some forgotten man or that of<br />

his own selfish desires would never be noticed,<br />

either. His anonymous handiwork, not only a<br />

smack in the face to an age-old enemy of his,<br />

but also a tip of the hat to a newfound psychosis<br />

driven by the need to stand up straight, was in<br />

fact all just a product of a universal accident:<br />

the dropping of an unlabeled aerosol can in the<br />

middle of a parking lot downtown.<br />

15<br />

<strong>St</strong> e p h e n Ke l l e y

Response t o a n a g e t h at f i n d s it p l e a s i n g t o<br />

o v e r u s e “r a n d o m ” a n d t o misuse “a b s t r ac t”<br />

Henry Goldkamp<br />

You’re so random! That was random.... RANDOM<br />

PIX!@#$@$!@!!89~~@! I

Ju s t Li k e Ol d Ti m e s<br />

Jake Kessler<br />

The sky was a cold, cloudy grey, and it<br />

started to rain.<br />

“Shit.”<br />

We had been standing out in the alley behind<br />

the building for twenty minutes now, waiting for<br />

Rick to pull around in the van. Eddie pulled his<br />

suit jacket more tightly around him and shuddered.<br />

“Cold out here.” He shuddered again.<br />

“Shoulda worn a coat,” I said.<br />

“Didn’t think we’d be out here so long,” he<br />

replied. “What’s takin’ him so long anyway?”<br />

“Hell if I know.”<br />

“Well, what do you think he’s doin’ in there,<br />

anyway?”<br />

“Eddie, I’ve still got no idea. I didn’t know<br />

when you asked me five minutes ago, I didn’t<br />

know when you asked me five seconds ago, and<br />

chances are that I still won’t know if you ask me<br />

five minutes from now, which I know you will<br />

because you can’t keep your damn mouth shut<br />

long enough to keep the food from fallin’ out of<br />

it.”<br />

“Christ Almighty, I was just tryin’ to make<br />

some conversation.”<br />

“Yeah, well, it’s not helping.”<br />

“He’s just been in there so long, I don’t<br />

know what he could be doin’.” He walked over<br />

to an old torn-up sofa someone had pitched out<br />

into the alley, started to sit down, then changed<br />

his mind and shuffled back over to the loading<br />

dock. “’Sides,” he went on, “It’s goddamn cold<br />

out here.”<br />

Rick turned away and drifted out of the<br />

office, past the smiling receptionist, and<br />

into the hall.<br />

We had always been buddies, Rick and I. I<br />

was the smart, quiet kid who lived down<br />

the street; he was the unruly rich kid with an<br />

affinity for chaos. God only knows when we<br />

first met, but in my earliest memory of him we<br />

couldn’t have been older than nine or ten. It<br />

was hot and sticky that summer, and I know it<br />

must have been Tuesday when Rick and I stole<br />

the bus. I know it was a Tuesday because on<br />

Tuesdays Rick’s father always went down to<br />

Vince’s place to count the money people had<br />

blown at the track and the bar over the weekend.<br />

Vince had made a small fortune pandering to the<br />

more unsavory elements in the neighborhood,<br />

and while nothing he did was illegal, it wasn’t<br />

anything you’d brag about to your mother either.<br />

Rick’s dad kept the books because it made<br />

the C.P.A. feel like he was living on the edge.<br />

Compared to most accountants, he was.<br />

Anyway, with Rick’s dad down at Vince’s<br />

and my parents at a funeral in Texas, we were<br />

left completely unsupervised. Leaving two bored<br />

kids to their own devices on a hot summer day<br />

is a lot like driving past a gas station during a<br />

dry spell and throwing a lit cigarette out of the<br />

window. By the time you realize what you’ve<br />

just done, you don’t know whether it would be<br />

better to go back to put out the fire or to floor it<br />

and drive far, far away, but you know either way<br />

something bad is going to happen to someone.<br />

That day, nobody bothered to put out the fire.<br />

The rain was coming down harder now, and<br />

I could see my breath dense as the soot<br />

pouring out of the stacks of the car factory a few<br />

blocks away. The neighborhood, usually filled<br />

with blaring car horns and colorful obscenities,<br />

had all of the eerie silence of a funeral parlor<br />

without any of the bad music or tasteless decorations.<br />

Thick, white steam poured out of the<br />

gutters and manholes, covering the ground in the<br />

same kind of fog that was always rolling around<br />

graveyards in horror movies. Eddie sidled up to<br />

Peter and put his hand on his shoulder.<br />

“Hey, buddy, how’s it goin’?”<br />

Peter remained motionless, staring out into<br />

the rain.<br />

“Buddy?”<br />

17

18<br />

He looked as if he were just part of the<br />

landscape, just another fixture poking up out of<br />

the broken asphalt, immutable.<br />

“C’mon, buddy, say somethin’, would<br />

ya?”<br />

Peter did not move.<br />

“Fine, be like that.” Eddie shuffled back<br />

over to the loading dock. “Whaddya suppose<br />

he’s doin’ in there, anyway?”<br />

The corridor was endless, an infinite progression<br />

of sickly pale fluorescent light bulbs<br />

flickering towards the vanishing point where<br />

they met<br />

the dirty<br />

l i n o l e u m<br />

tiles and<br />

the bare,<br />

stained drywall.<br />

A red<br />

exit sign<br />

promised<br />

an escape<br />

ahead, but<br />

he saw it<br />

as no more<br />

than a hollow<br />

mockery.<br />

He realized<br />

now<br />

that nothing out there was really any different<br />

than things were in here, and that no change of<br />

venue could erase that horrific revelation. Two<br />

security guards sprinted towards him, but he<br />

drifted on, impervious to their searching eyes,<br />

their questioning minds. He passed through<br />

untouched as they ran by him, back towards<br />

the dingy office. He drifted on, impervious,<br />

untouched.<br />

As usual, Rick came up with the plan. The<br />

bus stopped at the end of the block three<br />

times every weekday. His dad got on in the<br />

morning and off on the 4:30, leaving us with<br />

the 11:20. Every day, without fail, the heavyset<br />

He n ry Go l d k a m p<br />

woman who drove the bus pulled up to the stop<br />

then got out and went into the convenience store<br />

on the corner, where she deliberated for twenty,<br />

sometimes even thirty minutes on whether she<br />

would prefer to eat herself to death with a Ho-<br />

Ho and a Big Gulp or a pound of beef jerky and<br />

a few donuts. The plan was simple: bus lady<br />

comes out, we go in. Foolproof.<br />

The bus pulled up right on time. It was<br />

completely empty except for the driver and a<br />

tattered-looking old man asleep in the back row.<br />

The driver stood up, sweat literally dripping from<br />

her formless pink face and splattering on her uniform,<br />

leaving<br />

black<br />

s t a i n s<br />

on whatever<br />

they<br />

t o u c h e d .<br />

She walked<br />

inside.<br />

We sprang<br />

from our<br />

h i d i n g<br />

place behind<br />

a gas<br />

pump and<br />

sprinted towards<br />

the<br />

bus like it<br />

was Christmas morning. I did an overly theatrical<br />

dive into the open door, sliding under the wheel<br />

to take my designated place at the pedals. Rick<br />

took the wheel. Since neither of us had any idea<br />

of what to do next, we emulated the only driving<br />

instructor we had: television. “Floor it,” Rick<br />

yelled, attracting the attention of the bus driver,<br />

who was filling out her Lotto slip at the counter.<br />

I pressed down hard on the smaller of the two<br />

huge pedals with my hand and the bus jerked<br />

forward. We didn’t make it far, of course, only<br />

a block and a half until we had a run-in with a<br />

phone pole, and then everything came apart with<br />

a sickening crunch.

It was getting late. I couldn’t see the smoke<br />

from the factory anymore, and the soft patter<br />

of raindrops on the cheap tin sheet over the loading<br />

dock was giving way to the sharp, insistent<br />

pounding of hail. Peter still stood rock steady in<br />

the alley, while Eddie sat huddled up against the<br />

wall, shivering in earnest now. His teeth knocked<br />

against each other as he spoke. “I just wanna<br />

know what we’re doin’ here, is all.”<br />

I sighed. “I’m here ’cause Rick happens to be<br />

a friend of mine, and he asked me to come along<br />

’cause he’s in trouble. You’re here ’cause you<br />

insisted on tagging along like you always do, and<br />

Pete over there<br />

is here ’cause<br />

he’s Peter, an’<br />

that’s what he<br />

does. For the last<br />

goddamn time, I<br />

don’t know why<br />

Rick is takin’<br />

so long, but I’d<br />

expect he’ll be<br />

more than happy<br />

to tell you all<br />

about it when he<br />

comes out.”<br />

“What’s the<br />

deal with that<br />

guy, anyway?”<br />

“Rick?”<br />

“Nah, the other guy.”<br />

“Like I said, Peter is Peter. I dunno; he’s<br />

always been quiet ever since I met him years<br />

ago. Me, him, and Richie go way back.”<br />

“Uh hunh.” Eddie nods, but I can tell he<br />

isn’t really paying attention. He pulls out a pack<br />

of cigarettes and lights one up.<br />

“Those things kill, you know.”<br />

Peter came to us one stormy night straight<br />

from the Old Testament. A fight had broken<br />

out in the bar between one of the regulars, Eddie,<br />

and some big shot from Manhattan who he<br />

owed money. Eddie proceeded to make references<br />

to his creditor’s mother, at which point<br />

the brawl broke out. I was trying to pry apart a<br />

German immigrant from a Texan Communist<br />

when I noticed Peter’s massive form blocking<br />

the doorway. Without a word, he marched into<br />

the room, grabbed the Manhattanite by the collar,<br />

and stared at him. Without a word, Peter<br />

let go of him and watched as he fled the room.<br />

We’ve been close ever since.<br />

He had always said that he’d rather believe<br />

in God and be wrong than believe in nothing<br />

and be right, but now Rick knew better.<br />

He smiled for<br />

He n ry Go l d k a m p<br />

the first time<br />

in days, maybe<br />

for the first time<br />

since that summer<br />

so long ago.<br />

He’d just have<br />

to let him figure<br />

it out for<br />

himself.<br />

They found<br />

me where<br />

I had left off,<br />

curled up under<br />

the wheel. I was<br />

a mess: broken arm, three cracked ribs, blood<br />

everywhere. Rick was even worse off, but neither<br />

of us could compare to the old man who<br />

had been sleeping in the back. He must have<br />

been getting up to shout at us when we collided<br />

with the pole. His body was thrown clear of<br />

the bus, straight through the back door, and he<br />

catapulted through the empty space until he<br />

made contact headfirst with an unyielding wall.<br />

I was out cold, but Rick saw the whole thing.<br />

He didn’t speak again for seven years.<br />

W<br />

“ e’re going to be late, aren’t we?”<br />

Eddie looked absolutely miserable. His<br />

thin hair was plastered to his head, his dress shirt<br />

had gone transparent, and his skin had the same<br />

19

20<br />

scaly texture as a football. He rocked back and<br />

forth, legs hugged close to save what warmth<br />

he could. The smoke from his cigarette was indistinguishable<br />

from the steam that poured from<br />

his mouth and nose, and his voice was drowned<br />

out by the crash of ice on metal.<br />

“Would you really want to show up to a<br />

classy affair lookin’ like that, anyway?”<br />

He sighed this time. “Nah, I guess not. I just<br />

want to get outta here.”<br />

“Really?”<br />

He stared at me. A faint metallic click, and<br />

then the door opened.<br />

After he started talking again, Rick fell in<br />

with what my mother called “the wrong<br />

crowd,” and I always felt obligated to keep an<br />

eye on him. He would go missing for weeks at<br />

a time, only showing up again when he needed<br />

money or a place to hide. Took a toll on his old<br />

man and his heart condition more than anyone.<br />

After his father died, he got a job collecting<br />

for Vinny, who I had been working for since<br />

graduation. The work seemed to help. Rick<br />

was never happy in the traditional sense of the<br />

word, but he came as close to it as I had seen<br />

since the accident. His absences grew shorter<br />

and shorter until they eventually stopped. Vinny<br />

treated him like a son, and when he passed away<br />

it was Rick he left the business to.<br />

The end of his journey in sight, Rick darts<br />

out into the alley, positively gleeful now.<br />

The loudmouth from the bar sits curled up in<br />

a corner while he leans against a pole, a stark<br />

black silhouette against the icy curtain.<br />

The crack of Peter’s .45 is lost in the infernal<br />

din of the hailstorm, as are the next two<br />

shots. The hail comes to a stop and the corner<br />

of his mouth imperceptibly moves up a fraction<br />

of an inch as he walks towards the van.<br />

Al e x Gr m a n

Su n s e t<br />

Peter Lucier<br />

As I walk home from work, the world slides<br />

through my vision like the opening screen<br />

shot of some chick flick. I’d stare at my shoes,<br />

but every time my head drops I get a whiff of<br />

the store, and I’m pretty sick of smelling like<br />

that shithole. The sun is down just enough to<br />

sparkle red and gold across the tops of the<br />

trees, the oppressive heat of mid-day gone,<br />

leaving just the sinking warmth that gets deep<br />

inside you. Walking home was feeling pretty<br />

good, (better than being home), so I reminded<br />

myself not to walk so fast. Where was I rushing<br />

to anyway?<br />

The comforts of home. All those folksy singers<br />

always sang about wanting to come home,<br />

“Ho-omeward bound, I wish I wa-as.” Was no<br />

one ever content to sit out on the range and watch<br />

the sun go down?<br />

Looking up through the trees, the sky breaks<br />

into soft-edged pieces like stained glass through<br />

the overhanging branches, a swirl of blue and<br />

purple.<br />

Home, where it’s shit and sympathy that get<br />

piled up in front of you, a whole warm homemade,<br />

artery-clogging apple pie of lies that you<br />

get your face shoved into, so that after a week<br />

of it you just want to stand up in the middle of<br />

church and scream at the pastor, who insists that<br />

you patiently take the troubles of this world, week<br />

in and week out.<br />

Out there, in the real world, you get reality<br />

shoved in your face, and the truth hurts, at least<br />

I’m told. But at least it’s the truth… doesn’t that<br />

count for something?<br />

Laughing, I wonder what someone would<br />

think about this little conversation I’m having<br />

with myself. “What’s the matter, boy, don’t you<br />

love America? Eat it up with a spoon… or else.<br />

Or else all the good ol’ boys’ll call ya homasexchual,<br />

or a crazy, or a commie.”<br />

I’ve stopped walking. I’ve stopped really<br />

paying attention to what I’m looking at.<br />

The whole world is just a snapshot. Drag your<br />

sagging, overweight, white-collar ass to work<br />

everyday, so you can go home at night and be<br />

greeted with a botox smile from your third wife<br />

and two step-kids. “Send me to war,” I think,<br />

“cause, and pardon my French, ‘Eff that.’” Who<br />

wants that anyway? If you’re average, school<br />

scares you out of your pants for fear of failing,<br />

and if you’re smart, they dangle a carrot in front<br />

of you, promising… what? A two car garage,<br />

in the ‘burbs, monogrammed wine glasses, his<br />

and her towels, and cable TV? What they’re<br />

really advertising is safety. All the rest is just<br />

a bunch of crap to keep us from thinking about<br />

our MIND-NUMBINGLY BORING LIVES.<br />

Safety’s what’s offered, safety from “all them<br />

scary colored people running around at night<br />

with guns, and…God forbid…drugs!” Is that<br />

what we’ve traded our lives for?<br />

All the rhetorical diarrhea I’ve been spewing<br />

floats away like a bad dream when I catch sight<br />

of this angel, rocking in a porch swing in front<br />

of a white two-story across the street.<br />

Holy…Christ, she’s pretty. She’s got this<br />

little book in her lap, and her face all scrunched<br />

up, staring at the pages. Oblivious to this crippled<br />

skeleton of humanity staring at her, she’s patiently<br />

catching the last bit of sunlight on the<br />

pages. There she is, just a-sittin’, so pretty as you<br />

please, a couple wisps of her golden brown hair<br />

hanging over her face, slipped out of the rubber<br />

band which holds the rest back in a tight pony<br />

tail. She’s got on those short-shorts that always<br />

come out in the summer, and her legs are pulled<br />

up on the swing, and all I can see is the golden<br />

smooth skin, real soft in the light. The sun’s barely<br />

pushing a few gold and orange beams through<br />

the trees now, and there’s this smell, like summer<br />

in the air, warm dirt and old peanut shells…<br />

I’m almost drunk off it. Christ I’m right about<br />

to go over there, to this girl I don’t even know,<br />

because I just got to tell her how pretty she is, I<br />

don’t know, but something about walking over<br />

there seems like just the right thing to do….<br />

21

Before my feet can carry me though, I<br />

remember that I’m still wearing my uniform—<br />

scuffy brown dress shoes and thick knee-length<br />

crew socks, soaking my feet in sweat. My shirt<br />

still smells like the store, ammonia and bleach<br />

and that sawdust that janitors throw on little<br />

kids’ puke. Somehow my trance is broken. That<br />

feeling of “rightness” abandoned me about three<br />

steps towards her. I’m just disgusted all over<br />

again. What exactly was I going to do anyway,<br />

just walk up and say, “hey!” like some doofus?<br />

“You crazy old loon,” I think to myself, “you<br />

thought you’d found something?” Nervously<br />

glancing around to see if anyone’s watching<br />

me, I wonder how out of place I must look. If<br />

you’ve never used your feet to get around in<br />

your life, here’s an interesting truth for you: if<br />

you’re moving, no one notices you, you’re just<br />

another commuter with someplace to go, but the<br />

second you stop, you’re a sore thumb sticking<br />

out. Everybody’s so damn set on getting where<br />

they need to go, eyes on the road or their feet,<br />

that there is something about someone taking a<br />

break that seems almost...diseased.<br />

My feet are walking again, and looking back<br />

over my shoulder, she slowly pans out of view<br />

like some bad romance flick. I look down at my<br />

shoes and get a whiff of that shithole. I need a<br />

shower.<br />

22<br />

He n ry Go l d k a m p

Gr av e d i g g e r<br />

Kyle Kloster<br />

Driving home that night, I clicked my<br />

headlights on and off, watching the world<br />

disappear for an instant and then return safely,<br />

the same as before. After the last turn before<br />

my neighborhood I flicked them off again, and<br />

when the revealing lights flashed back on, the<br />

wide eyes of a doe glinted back from the sidewalk<br />

fifty feet in front of me. I jumped a little,<br />

involuntarily, and coasted the last leg home<br />

through the fog of a dazed mind, my thoughts<br />

slow with shock and wonder. Who would hit<br />

a deer and then leave the animal’s body right<br />

on a sidewalk corner, right next to someone’s<br />

home—where children, who may not have even<br />

seen any relatives die yet, live?<br />

The dead animal was only a quarter-mile<br />

from my house, the closest I’ve ever seen road<br />

kill to my home (they seem to get closer every<br />

time). Before I pulled into my garage, I resolved<br />

to go back with a shovel, dig a hole not far from<br />

the road, and bury the poor creature to protect<br />

its corpse and the people who drove by, those<br />

who saw but forgot seconds later the lonely and<br />

cruel demise of something more innocent than<br />

any of us.<br />

I parked down the street from it and zipped<br />

up my coat after getting out of the car—it was<br />

the coldest night of the month, but I was warm<br />

inside two coats and a pair of gloves. I walked<br />

with purpose in each step, holding a shovel and<br />

a trash bag in my hands. As I approached it, I<br />

could see the doe’s entire body intact, and it<br />

looked as if it was napping with open eyes. I<br />

stopped several feet from it, bewildered at how<br />

different it looked from every stuffed deer, lawn<br />

ornament, or picture I had ever seen. This was<br />

the closest I had ever looked at life.<br />

A pair of halogen eyes flashed from down<br />

the road, and as they neared me they slowed<br />

down as though to stop and stare. I felt almost<br />

embarrassed standing next to this dead deer. A few<br />

smears of blood gleamed on the street, invisible<br />

until I crouched down for examination. I found<br />

no breaks in the animal’s hide or wet patches of<br />

fur. Its legs looked locked, frozen at attention to<br />

whatever harsh superior commanded her now,<br />

and its face held fast in confused awareness,<br />

eyes open with the hopeless awe and despair<br />

of having spied from afar the human world of<br />

daunting unfamiliarity. I took off a glove and<br />

sneaked a pet, amazed at the yielding flesh and<br />

soft, cold fur. Another car revved a ways down<br />

the road, and I shot up, still embarrassed by my<br />

position. After it passed, I threw the trash bag<br />

around my arms, guarding myself from blood<br />

and other impurities of dead things, and bent<br />

down to pick up the body. I tugged, but gave up<br />

instantly, shocked at the sandbag weight of the<br />

carcass and its statuesque inflexibility. It was<br />

smaller than grown humans I had given piggy<br />

back rides, but I could not lift it.<br />

Headlights blinked closer through trees not<br />

far down the road, and I moved away a few feet,<br />

ashamed. Alone again, I quickly fit the trash bag<br />

over my hands and dragged it across the pavement<br />

by its hooves, aiming for a ditch on the<br />

other side where the body would at least keep<br />

out of sight and reach of neighborhood kids. I<br />

frantically heaved the doe, like a mulch sack, to<br />

the ground there, too scared to dig a hole, and<br />

sprinted back to the comfort of my car. It was<br />

all I had the courage to do.<br />

23

24<br />

Me t r o<br />

Tony Bertucci<br />

Metropolitan Deed Recording, Incorporated.<br />

That’s what it’s called. But don’t<br />

let the name fool you, it’s not exactly a bastion<br />

of corporate standards as the title might suggest.<br />

It’s not even that metropolitan if you ask me.<br />

It’s a weed in the rich industrial lawn off Page,<br />

a crack in the pavement. A person’s liable to<br />

drive right by it if they didn’t know any better,<br />

and if I could give that person some advice, I’d<br />

tell them to quit looking for it and go home—it’s<br />

probably not worth the time.<br />

I worked<br />

there last summer.<br />

The name<br />

f o o l e d m e .<br />

I could just<br />

imagine writing<br />

those four<br />

sophisticated<br />

words on a job<br />

resume, and<br />

I had always<br />

wanted to be<br />

“incorporated”<br />

in something<br />

anyway. My<br />

first day, the<br />

boss explained<br />

to me just exactly<br />

“what we do” here at the Metropolitan<br />

Deed Recording, Incorporated. “What we do”<br />

involved processing every single record of land<br />

distribution or exchange that occurred in <strong>St</strong>.<br />

<strong>Louis</strong>. I was an integral part of the “Hub of the<br />

American Dream,” and I would be going down<br />

in the basement with Neil to get “oriented to the<br />

system.” Getting “oriented” with creepy Neil<br />

down in the dark under-dwellings of the office<br />

brought a number of scenarios to mind, many<br />

of them disturbing, but I suppressed my urge to<br />

flee and gave myself up in hopes that the walls<br />

would be thin enough that the others could hear<br />

my screams.<br />

We descended the stairs. The “Hub of the<br />

American Dream” turned out to be a sordid array<br />

of congruent cubicles juxtaposed throughout the<br />

dimly lit, cheaply carpeted basement.<br />

“I’m gonna show you how to make some<br />

copies,” Neil yawned. “I just started working<br />

here a couple weeks ago, so I probably won’t<br />

be too much help. It’s like the blind leadin’ the<br />

blind.”<br />

I let out a very thin and awkward chuckle,<br />

hoping creepy Neil couldn’t see through my shallow<br />

gestures of pitiful friendliness. I saw a head<br />

Lo u i s Mo n n i g<br />

pop up from a<br />

nearby cubicle<br />

from the corner<br />

of my eye, but<br />

when I looked<br />

over they had<br />

vanished. I was<br />

being watched<br />

and I knew it.<br />

The basement<br />

dwellers were<br />

peering through<br />

their cubicles<br />

like suspicious<br />

natives as I<br />

marched by, trying<br />

my best to<br />

seem oblivious<br />

to their scrutiny.<br />

“It’s really not hard at all,” said Neil. I stared<br />

through the steam rising from Neil’s coffee cup at<br />

the blurry, horribly mundane images of computer<br />

monitors and paper trays. It was making my head<br />

spin, but I looked on nonetheless in captivated<br />

silence.<br />

“What are you lookin’ at, kid?” Neil broke<br />

my trance. “You’re creepin’ me out a little,” he<br />

giggled—a weird, raspy, grizzled giggle. Though<br />

I had imagined it an impossible task, I had evi-

dently managed to creep out creepy Neil, the<br />

connoisseur of creepy basement orientation.<br />

By the next week I had become quite unpleasantly<br />

oriented to the basement workings.<br />

The squeamish mole-people of the cubicles<br />

began to venture out and talk to me, showing<br />

their broadly weird idiosyncrasies. They told<br />

stories of the world up above, where it was still<br />

light and warm. Even the coffee tasted better,<br />

they said as they mulled around and tried to act<br />

as busy as possible. Todd told me stories of his<br />

days traveling with the national Judo team. Bill<br />

told me stories of Todd’s mental instability. I<br />

became addicted to coffee and developed an<br />

odd affinity for<br />

rubber bands. I<br />

was reluctantly<br />

being assimilated<br />

into the<br />

family.<br />

In a couple<br />

of months I<br />

would be heading<br />

off to college,<br />

starting<br />

a new chapter,<br />

opening new<br />

doors, and all<br />

the rest of those<br />

cheesy slogans<br />

on the pamphlets<br />

they send<br />

out. I had gotten in to the college I wanted to go<br />

to, or at least where I thought I wanted to go. My<br />

last semester of high school had whirred by in a<br />

complacent lump of uneasiness, the byproduct<br />

of a relatively passive college selection process.<br />

I knew where I wanted to go to only by lack of<br />

preference. It’s not that I didn’t care, I just lacked<br />

the prerequisites to make an informed decision<br />

about what will ultimately dominate the rest of<br />