Social Stories - Southern Early Childhood Association

Social Stories - Southern Early Childhood Association

Social Stories - Southern Early Childhood Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Southern</strong><br />

<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong><br />

Dimensions<br />

Volume 33, Number 2 Spring/Summer 2005<br />

Inside this issue:<br />

• Family Diversity<br />

• <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Stories</strong><br />

• Leveled Texts<br />

• Curriculum Is a Verb<br />

• Children’s Insights<br />

on Diversity<br />

of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong>

Nashville, TN<br />

Join Us in Nashville, TN<br />

at Opryland for SECA 2006<br />

February 2-4, 2006<br />

Check the SECA website by September 1, 2005 to get information<br />

about housing, transportation, registration and program.<br />

Proudly Display your<br />

SECA membership<br />

with our new<br />

SECA Pin!<br />

$4.00 to<br />

members<br />

$5.00 to<br />

non-members<br />

Makes a great staff<br />

or parent gift.<br />

SECA LITERACY KITS<br />

$6.95<br />

SECA Member<br />

$8.95<br />

Non-member<br />

SECA and August House Publishers<br />

have joined together to provide you<br />

with the best in children’s literature<br />

and the “know-how” to effectively<br />

use children’s storybooks in your program.<br />

Each kit contains a storybook<br />

from August House and a teacher’s<br />

guide from SECA with ideas on<br />

extending your reading time into<br />

other areas of the curriculum.<br />

LK 100 Stone Soup<br />

LK 200 Sitting Down to Eat<br />

LK 300 Why Alligator Hates Dog<br />

LK 400 A Big Quiet House

<strong>Southern</strong><br />

<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong><br />

Editor - Janet Brown McCracken<br />

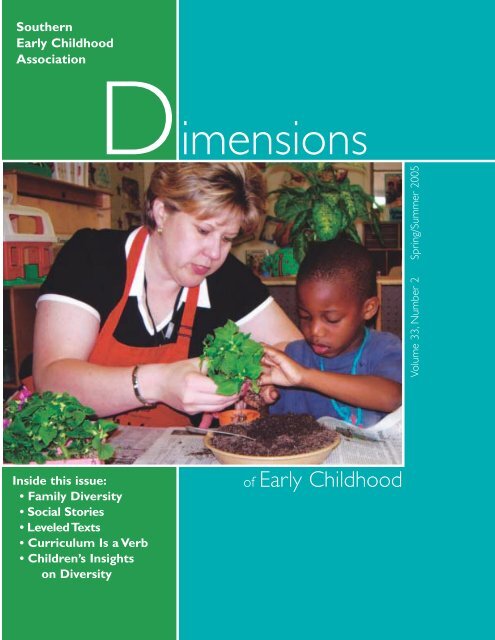

Cover photo by Elisabeth Nichols<br />

Dimensions of<br />

<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

Copyright ©2005, <strong>Southern</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong> (SECA). Permission is not<br />

required to excerpt or make copies of articles in<br />

Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> if they are distributed<br />

at no cost. Contact the Copyright Clearance<br />

Center at (978) 750-8400 or www.copyright.com<br />

for permission for academic photocopying<br />

(coursepackets, study guides, etc.).<br />

Indexes for Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> are<br />

posted on the SECA website at www.<strong>Southern</strong>-<br />

<strong>Early</strong><strong>Childhood</strong>.org. Additional copies of Dimensions<br />

of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> may be purchased from<br />

the SECA office by calling (800) 305-SECA.<br />

Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> (ISSN 1068-6177)<br />

is SECA’s journal. Third Class postage is paid at<br />

Little Rock, Arkansas. SECA does not accept<br />

responsibility for statements of facts or opinion<br />

which appear in Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong>.<br />

Authors are encouraged to ask for a copy of<br />

SECA’s manuscript guidelines. Submit manuscripts<br />

that are typed and double spaced with references<br />

in APA style. E-mail manuscripts for review to the<br />

editor at editor@southernearlychildhood.org.<br />

SECA serves the interests of early childhood<br />

educators concerned with child development,<br />

including university researchers and teacher educators;<br />

early childhood, kindergarten, and primarygrade<br />

teachers; and early childhood program administrators<br />

and proprietors.The association has affiliates<br />

in 13 <strong>Southern</strong> states. Non-affiliate memberships are<br />

available to anyone living outside the 13 affiliate<br />

states. For information about joining SECA, contact<br />

the executive offices at P.O. Box 55930, Little Rock,<br />

AR 72215-5930, (800) 305-7322. Members receive<br />

a one-year subscription to Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong><br />

<strong>Childhood</strong> and discounts on SECA publications and<br />

conference registration fees.<br />

<strong>Southern</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

P.O. Box 55930<br />

Little Rock, AR 72215-5930<br />

(800) 305-7322<br />

e-mail: editor@southernearlychildhood.org<br />

Web: www.southernearlychildhood.org<br />

Dimensions<br />

of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

Volume 33, Number 2 Spring/Summer 2005<br />

—Refereed Articles—<br />

3<br />

Curriculum Is a Verb, Not a Noun<br />

Barbara Sorrels, Deborah Norris, and Linda Sheeran<br />

11<br />

Drawings on the Wall: Children’s Insights for Defining Diversity<br />

Diana Nabors and Cynthia G. Simpson<br />

18<br />

Enhancing Literacy With Leveled Texts: One School’s Experience<br />

Anita McLeod and Kathryn Parmer<br />

24<br />

R-E-S-P-E-C-T for Family Diversity<br />

Sabrina A. Brinson<br />

32<br />

<strong>Social</strong> <strong>Stories</strong>: Tools to Teach Positive Behaviors<br />

Sharon A. Lynch and Cynthia G. Simpson<br />

—Departments—<br />

2<br />

President’s Message<br />

Beverly Oglesby<br />

37<br />

Strategies to Support Children—<br />

Summer Carnival:“We did it ourselves!”<br />

Nancy P. Alexander<br />

39<br />

Book Reviews—Books for <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Educators<br />

E. Anne Eddowes, Editor<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 1

BOARD OF DIRECTORS<br />

Beverly Oglesby<br />

President<br />

3138 Rhone Drive<br />

Jacksonville, FL 32208<br />

Terry Green<br />

President-Elect<br />

302 Clay Street<br />

Henderson, KY, 42420<br />

AFFILIATE REPRESENTATIVES<br />

Kathi Bush<br />

-Alabama- Jefferson State Community College<br />

2601 Carson Rd.<br />

Birmingham, AL 35215-3098<br />

Diana Courson<br />

-Arkansas-<br />

2 Woodlawn<br />

Magnolia, AR 71753<br />

Nancy Fraser Williams<br />

-Florida- 2430 NW 38th St.<br />

Gainesville, FL 32605<br />

Beth Parr<br />

Methodist Homes for Children<br />

-Georgia- 15 Jameswood Avenue<br />

Savannah, GA 31406<br />

Kathy Attaway<br />

-Kentucky- 401 Persimmon Ridge Drive<br />

Louisville, KY 40245<br />

Susan Noel<br />

-Louisiana- 211 Maureen Drive<br />

Youngsville, LA 70592<br />

Capucine Robinson<br />

-Mississippi- Jackson Public School District<br />

662 S President St.<br />

Jackson, MS 39201<br />

Georgia Lamirand<br />

-Oklahoma- 2013 Rocky Point Drive<br />

Edmond, OK 73003<br />

Judy Whitesell<br />

-South Carolina- 309 Moss Creek Dr.<br />

Cayce, SC 29033<br />

Nancy James<br />

-Tennessee- 7520 Cainsville Rd.<br />

Lebanon, TN 37090<br />

Judy Carnahan-Webb<br />

-Texas-<br />

11927 Waldeman<br />

Houston, TX 77077<br />

Steven Fairchild<br />

-Virginia- James Madison University<br />

MSC 1904<br />

Harrisonburg, VA 22807<br />

Nancy Cheshire<br />

-West Virginia- 270 W. Philadelphia<br />

Bridgeport, WV 26330<br />

Sandra Hutson<br />

1010 St. Peter St.<br />

New Iberia, LA 70560<br />

MEMBERS AT LARGE<br />

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE<br />

Janie Humphries<br />

Louisiana Tech University<br />

Gloria Foreman McGee<br />

Tennessee Technological<br />

University<br />

Ollie Davis<br />

Houston Independent<br />

School District<br />

STAFF<br />

Glenda Bean<br />

Executive Director<br />

Lourdes Milan<br />

19019 Portofino Drive<br />

Tampa, FL 33647-3088<br />

Stephen Graves<br />

University of South Florida<br />

Peggy Jessee<br />

University of Alabama<br />

Nancy Mundorf<br />

Florida<br />

PRESIDENT’S<br />

MESSAGE<br />

As I take pen in hand to compose this President’s<br />

Message, I think about two things: the completion<br />

of a school year and the 56th annual conference of the Beverly Oglesby<br />

<strong>Southern</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

The school year has ended and teachers often say to ourselves,<br />

“Where did the year go?” We look back at how it started and how we<br />

faced the challenges and enjoyed the rewards. We think about whether<br />

or not we achieved all of the learning standards and we know that children<br />

learned and enjoyed that learning. The students passed that test<br />

that we were required to give even though we knew it wasn’t best practice.<br />

We faced the challenge of working with parents who wanted us to<br />

focus only on their child and helped them to learn that their child was<br />

one in a community of learners.<br />

We think about the little stars that came to us at the very beginning.<br />

Some were very shiny and others needed a little more polishing. Daily,<br />

we watched as they grew and as we helped polish. Helping children to<br />

grow and meet their potential is the biggest reward in working in the<br />

early childhood field.<br />

SECA celebrated early childhood professionals at the 56th annual<br />

conference held in Dallas, Texas, in March. Our theme was “Hitch Your<br />

Wagon to a Star” and SECA became that “star” for many who attended.<br />

Your SECA Board of Directors hosted this conference under the<br />

leadership of our awesome Executive Director, Glenda Bean.<br />

Although I was not able to attend due to a family crisis, Nancy<br />

Cheshire, SECA Vice-President, and Terry Green, President-Elect,<br />

made sure that the conference ran smoothly. The feedback I’ve received<br />

is that the conference was very professionally done, from the pre-conference<br />

sessions to the keynote speakers to the interest sessions. I would<br />

like to thank the SECA Board of Directors for taking on the extra challenge<br />

in my absence and making this conference a wonderful experience<br />

for everyone involved.<br />

This year, SECA financially supported its state affiliates in bringing<br />

their Presidents and another leader to the first SECA Leadership Summit.<br />

The Summit was designed to give the Board of Directors insight and<br />

input from the state affiliates. I want to thank all of the state leaders who<br />

attended and for your input on how to take SECA forward into the<br />

future. It takes both new and experienced leaders to guide an organization<br />

and we want to say a special “thank you” to the Fossils for sharing their<br />

wisdom and knowledge to help us keep our focus on SECA’s mission.<br />

SECA is truly a “Voice for <strong>Southern</strong> Children” and we have a bright<br />

future ahead!<br />

2 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

Is curriculum something to be bought and taught? Or a dynamic process that is<br />

constantly changing? This article invites teachers to take a look at assumptions<br />

about children, teachers’ roles, and the continuous process of curriculuming.<br />

Curriculum Is a Verb, Not a Noun<br />

Barbara Sorrels, Deborah Norris, and Linda Sheeran<br />

The word curriculum brings to mind different definitions<br />

for teachers, administrators, and families. For<br />

many educators, the word evokes images of glossy packaged<br />

materials with “fool-proof” teachers’ guides. Thick,<br />

spiral-bound manuals provide detailed scripts and stepby-step<br />

instructions for the entire school day. The content<br />

is artificially compartmentalized into disconnected<br />

subject areas, each with its own script and prescribed<br />

activities. It is typically a “one size fits all” approach<br />

(Ohanian, 1999). All children are expected to learn the<br />

same content, perform the same tasks, and achieve the<br />

same results.<br />

This view of curriculum is based on<br />

traditional behaviorist theory that<br />

learning is a transactional process. Children<br />

are seen as empty vessels into<br />

which the all-knowing teacher pours<br />

knowledge and information outlined in<br />

a textbook. The content of this type of<br />

curriculum is to be “covered” and “taught” (Anderson,<br />

2000). The teacher’s primary role is to “deliver” curriculum<br />

rather than to create curriculum (Meyer, 2002).<br />

According to this view, curriculum is a product that<br />

can be bought and sold. Packaged curriculums are often<br />

marketed by publishers who are quick to embrace the<br />

most recent news of doom and gloom about the poor<br />

job that schools are doing as reflected in standardized<br />

test scores. They make grandiose promises to teachers<br />

and school district personnel that their particular product<br />

is the panacea for their educational ailments. In<br />

order to appeal to the broadest possible market, and to<br />

make the biggest profit, breadth rather than depth is the<br />

primary concern.<br />

<strong>Early</strong> childhood faculty and staff at Oklahoma State<br />

University (and many other high-quality universities and<br />

schools) believe that such a simplistic approach to curriculum<br />

undermines professional wisdom and teacher<br />

Curriculuming<br />

begins with<br />

careful observation<br />

of children.<br />

knowledge. In addition, it fails to effectively meet the<br />

needs of individual children.<br />

Informed by constructivist theory and the Reggio<br />

approach (Hendrick, 1997), most early childhood educators<br />

have come to view curriculum as a complex,<br />

dynamic process. This process is seen as constantly<br />

evolving and changing as teachers, children, the environment,<br />

and the community inform and interact with<br />

each other. Children’s learning is not something that can<br />

be bought and sold. Rather, children primarily learn<br />

through actions that take place over time. Curriculum is<br />

a verb, not a noun.<br />

The act of “curriculuming” is much<br />

like conducting a symphony. Just as the<br />

symphony conductor must balance the<br />

sounds of many different instruments to<br />

form beautiful, harmonious music, so<br />

too must teachers maintain a delicate<br />

balance between their own professional<br />

wisdom; the characteristics, interests, and needs of children;<br />

local, state, and national standards; and family<br />

and community resources and expectations.<br />

A symphony has many layers of textures and instrumentation.<br />

The curriculuming process is also multi-lay-<br />

Barbara Sorrels, Ed.D., is Assistant Professor of <strong>Early</strong><br />

<strong>Childhood</strong> Education, Oklahoma State University-Tulsa.<br />

Deborah Norris, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of <strong>Early</strong><br />

<strong>Childhood</strong> Education, Oklahoma State University-Stillwater.<br />

Linda Sheeran, Ed.D., is Visiting Professor of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

Education, Oklahoma State University-Stillwater.<br />

All three authors are instructors of the undergraduate<br />

integrated curriculum course. Each one has more than<br />

20 years of teaching and administrative experience with<br />

young children.<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 3

ered, with thematic units, individual<br />

and group projects, skill-driven<br />

activities, and incidental learning<br />

opportunities working in harmony<br />

with one another.<br />

Recurring motifs and themes wax<br />

and wane throughout a musical production.<br />

In a similar way, different<br />

emphases wax and wane throughout<br />

the curriculuming process in<br />

response to the needs and interests<br />

of children, community events, and<br />

available resources. Effective teachers<br />

become adept at balancing these<br />

many facets to create curricula that<br />

meet the needs of children both<br />

individually and collectively, satisfy<br />

community and family expectations,<br />

and meet state requirements<br />

for accountability.<br />

Effective “curriculuming” is a<br />

challenging task built upon several<br />

assumptions about children, the role<br />

of the teacher, and the process itself.<br />

Assumptions About<br />

Children<br />

Children Are Curious<br />

Curriculuming is born out of<br />

curiosity. Young children are by<br />

nature very curious about the world<br />

and how it works (Perry, 2004).<br />

Curiosity drives children to ask<br />

questions, to wonder, and to explore<br />

the environment. Curriculuming<br />

begins with careful observation of<br />

children in order to discern those<br />

things that spark their curiosity and<br />

evoke questions. Curiosity, not<br />

teachers’ guides, leads teachers to<br />

choose those things that genuinely<br />

engage children’s interests and<br />

inform curriculum content.<br />

Recognition of the curious nature<br />

of children implies that children do<br />

not have to be coerced to learn—they<br />

are enthusiastic learners by nature.<br />

Curiosity is not something that must<br />

be stirred up in children—but something<br />

that teachers must be careful<br />

not to snuff out or extinguish<br />

through didactic, authoritarian, textand<br />

test-driven instruction and<br />

teaching (Anderson, 2000).<br />

The goal for many early childhood<br />

educators today is to avoid<br />

squeezing the curiosity out of children.<br />

Education has traditionally<br />

begun with content. Students are<br />

presented with definitions, facts,<br />

and dates to memorize with the goal<br />

of producing right answers. However,<br />

well-informed educators now<br />

advocate an approach to curriculuming<br />

that centers on encouraging<br />

children to ask the right questions<br />

rather than get the right answers.<br />

Starting with the questions that<br />

children think and wonder about<br />

keeps their curiosity (and their<br />

teachers’ curiosity) alive.<br />

Nancy P. Alexander<br />

Teachers maintain a delicate balance between their own professional wisdom; the<br />

characteristics, interests, and needs of children; local, state, and national standards;<br />

and family and community resources and expectations.<br />

Children Are Theory Builders<br />

As children act upon and interact<br />

with people and objects in their<br />

environment, they are constantly<br />

building and refining theories about<br />

the world and how it works<br />

(Chaille, 2003). Their quest to<br />

make sense and meaning of their<br />

world is evidenced by their drive to<br />

form connections, establish relationships,<br />

and recognize patterns.<br />

A contemporary approach to<br />

curriculuming respects the role of<br />

children as serious theory builders.<br />

Children are provided with<br />

authentic experiences that are rich<br />

in content. They encounter many<br />

opportunities for critical thinking<br />

and inquiry.<br />

Traditional approaches to early<br />

childhood curriculum often focus<br />

on activities that are cute and<br />

charming, but offer little in the way<br />

4 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

of substance and meaning. For<br />

example, thematic units focusing<br />

on bears is a popular topic in many<br />

early childhood classrooms. Pictures<br />

of bears dressed in cute clothing<br />

adorn the walls. Favorite teddy<br />

bears are brought from home to<br />

participate in a “Teddy Bear’s Picnic.”<br />

Bear-shaped cookies are served<br />

for snack.<br />

Although these opportunities are<br />

often amusing, they provide very little<br />

in the way of meaningful content<br />

and opportunities for intellectual<br />

engagement. Cutesy activities insult<br />

children’s intelligence. They often<br />

undermine children’s theory-building<br />

process by providing inaccurate<br />

and misleading information (Sussna,<br />

2000). When do children see<br />

bears dressed in human clothing?<br />

Instead, investigating the habitats of<br />

bears around the world, their sleeping<br />

habits, diets, and playful behaviors<br />

are content-rich topics that<br />

enhance children’s knowledge and<br />

understanding of the world.<br />

Children are<br />

enthusiastic<br />

learners by nature.<br />

Children Are Driven to Connect<br />

With Others<br />

A well-informed curriculuming<br />

process recognizes the highly social<br />

nature of children and their desire<br />

and drive to connect with others.<br />

Interpersonal relationships not only<br />

meet important social and emotional<br />

needs of young children but also<br />

make an important contribution to<br />

their learning.<br />

Cooperation, rather than competition,<br />

is fostered and encouraged in<br />

high-quality programs. As children<br />

are confronted with differing perspectives<br />

and ways of solving problems,<br />

they must naturally negotiate<br />

and renegotiate their own theories<br />

and understandings about the world.<br />

Curriculuming, therefore, provides<br />

a balance between large- and<br />

small-group activities as well as individual<br />

learning experiences to meet<br />

each child’s needs. Throughout the<br />

day children are given the opportunity<br />

to interact with peers and<br />

adults in a variety of settings as well<br />

as have spaces and opportunities for<br />

solitude and reflection.<br />

Children Are Active Physically as<br />

Well as Mentally<br />

The fact that children are physically<br />

active is obvious even to an<br />

untrained observer. The curriculuming<br />

process recognizes that more<br />

than children’s minds come to<br />

school, so it seeks to provide opportunities<br />

and experiences that enable<br />

children to touch, feel, taste, run,<br />

jump, sing, dance, draw, and paint<br />

their way into learning.<br />

Authentic learning does not happen<br />

while children are quietly sitting<br />

at desks with pencils in hand, but<br />

takes place as children move about,<br />

acting upon their environment.<br />

Authentic learning is sometimes a<br />

noisy and messy process.<br />

Children’s Emotional Natures<br />

Affect Curriculuming<br />

Young children are highly emotional<br />

beings. Intense moments of<br />

joy, anger, sadness, frustration, and<br />

satisfaction ebb and flow throughout<br />

the day. Curriculuming<br />

acknowledges the impact that emotions<br />

have on the learning process<br />

and seeks to create an environment<br />

that is responsive and supportive of<br />

children’s feelings.<br />

Fear is one of the most detrimental<br />

emotions to learning. Brain research<br />

has shown that perceived threat,<br />

either physical or emotional, causes<br />

the brain’s energy to become concentrated<br />

in the brainstem, shutting<br />

down a child’s ability to engage in<br />

higher-order thinking (Bruer, 1999).<br />

<strong>Early</strong> childhood educators therefore<br />

advocate an approach to curriculuming<br />

that takes place in the<br />

context of an emotionally safe environment<br />

that is free of threat and<br />

fear. This requires that teachers be<br />

attuned to children’s emotional<br />

states. Adults constantly monitor<br />

children’s intensity of activity, the<br />

level of fear and frustration, and the<br />

degree of pleasure and excitement.<br />

Careful listening and observation<br />

of children’s emotions inform<br />

the curriculuming process about<br />

the kinds of experiences and opportunities<br />

that motivate and engage<br />

children’s minds, and those that<br />

frustrate and discourage them.<br />

Becoming attuned to a group’s<br />

emotional states can be a challenging<br />

task for any teacher. Children’s<br />

faces are usually accurate barometers<br />

of their emotional states.<br />

Teachers must become adept at<br />

reading this non-verbal, but very<br />

powerful, form of communication.<br />

Cutesy activities<br />

insult children’s<br />

intelligence.<br />

Roles of Teachers<br />

Teachers Facilitate Learning<br />

The teacher, not any textbook or<br />

collection of worksheets, is the agent<br />

of the curriculuming process. Cur-<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 5

iculuming challenges and changes<br />

traditional teacher roles. The traditional<br />

approach to education views<br />

learning as a transactional process,<br />

much like depositing money in a<br />

bank account. The (non-existent)<br />

all-knowing teacher deposits knowledge<br />

into the minds of children as<br />

an even exchange.<br />

Anderson (2000) refers to this<br />

view as the “mug and jug” approach<br />

to education. The teacher pours<br />

from the jug of knowledge into children’s<br />

empty minds, represented by<br />

the mug. Teaching as the simple act<br />

of imparting of knowledge might<br />

seem to make sense in an unchanging<br />

world and this has been an<br />

unquestioned role for centuries.<br />

However, if there is one truth<br />

today, it is that the world is constantly<br />

changing (Rogers &<br />

Freiberg, 1994). The teacher’s role<br />

as depositor of knowledge must be<br />

abandoned, so that professionals can<br />

become facilitators of learning.<br />

Teachers’ roles switch from content<br />

transmitters to process managers.<br />

“Getting rewards from controlling<br />

students is replaced by getting<br />

rewards from releasing students”<br />

(Musinski, 1999, p. 25).<br />

The primary responsibility of<br />

teacher as facilitator is to create an<br />

emotionally and physically safe<br />

environment that ignites children’s<br />

curiosity and engages their interests.<br />

A facilitator has no preconceived<br />

agenda and is less likely to<br />

take ownership of a project away<br />

from children who are in the cycle<br />

of learning.<br />

Teachers effectively manage time,<br />

space, materials, and relationships as<br />

they prepare this type of learning<br />

environment. Routines and transitions<br />

are carefully orchestrated so<br />

that the bulk of children’s time is<br />

Subjects & Predicates<br />

Curriculuming begins with careful observation of children in order to discern those<br />

things that spark their curiosity and evoke questions. Curiosity, not teachers’ guides,<br />

leads teachers to choose those things that genuinely engage children’s interests and<br />

inform curriculum content.<br />

spent in meaningful learning activities.<br />

Teachers also balance time spent<br />

in large and small groups, indoor<br />

and outdoor play, and in structured<br />

and unstructured activities.<br />

Another consideration is length<br />

of time for children’s learning<br />

experiences. Creativity and complex<br />

engagement require unhurried<br />

time for maximum involvement.<br />

6 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

Authentic learning is<br />

sometimes a noisy<br />

and messy process.<br />

The facilitator must carefully monitor<br />

the level of engagement to discern<br />

when it is time to change<br />

activities and when it is time to<br />

allow children to continue to pursue<br />

their activity.<br />

When managing space, attention<br />

must be given to safety, access,<br />

and efficiency (Bredekamp &<br />

Rosegrant, 1992). Physical space<br />

communicates messages that affect<br />

children’s behavior. Wide-open<br />

areas and long hallways beckon<br />

children to run and play. Space is<br />

therefore arranged to accommodate<br />

large groups, small groups,<br />

and individual activities.<br />

Quiet, cozy places are provided<br />

for those moments when children<br />

need to pull away from the noise<br />

and activity of the classroom to find<br />

a place of solitude. Traffic patterns<br />

are carefully planned to minimize<br />

congestion and reduce the likelihood<br />

of injury. If the classroom has<br />

children with special mobility<br />

needs, space is arranged so that children<br />

with wheelchairs, walkers, and<br />

crutches can safely maneuver their<br />

way around.<br />

Effective facilitators of learning<br />

manage materials to provoke wonder,<br />

curiosity, and intellectual<br />

engagement (Curtis & Carter,<br />

2003). Open-ended materials with a<br />

variety of textures, colors, and functions<br />

are beacons to create, invent,<br />

and experiment.<br />

Wise facilitators carefully monitor<br />

children’s use of materials to discern<br />

when they have maximized<br />

their engagement and other materials<br />

need to be added or changed.<br />

Materials are also organized to promote<br />

children’s independence.<br />

When children follow procedures<br />

for the use and care of materials,<br />

teachers are free to spend the bulk<br />

of their energy and time focusing on<br />

the curriculuming process.<br />

Learning takes place in the context<br />

of relationships and, as a result,<br />

teachers are often called upon to<br />

facilitate conflict resolution and<br />

problem solving among the children.<br />

The relational aspect of the<br />

classroom is as much a part of the<br />

curriculuming process as the content<br />

that is learned. Facilitating<br />

interpersonal relationships requires<br />

a great deal of patience and insight.<br />

The wise teacher knows when to<br />

intervene and when to let children<br />

work things out on their own.<br />

Teachers Are Provocateurs<br />

During the process of curriculuming,<br />

effective teachers seek to challenge<br />

children to think in new and<br />

different ways. This often begins by<br />

stimulating children to think about<br />

what they already know. Teachers<br />

build upon prior knowledge to lead<br />

children into more complex and creative<br />

ways of thinking. Asking<br />

provocative questions challenge<br />

children’s current ways of thinking<br />

and cause them to think more<br />

deeply or differently about a given<br />

topic. Effective provocateurs are<br />

masters at asking divergent questions—those<br />

that have no right or<br />

wrong answers and require children<br />

to answer with more than a yes or<br />

no answer.<br />

The Oklahoma State model of<br />

curriculuming envisions that teachers<br />

spend much of their time supporting<br />

children’s investigations. As children<br />

act upon and interact with the world<br />

around them, questions are generated<br />

about how the world works.<br />

Wise teachers avoid giving pat<br />

answers and skillfully respond with<br />

further questions that guide children<br />

to think in new ways. Sometimes,<br />

the teacher introduces situations<br />

that create “cognitive dissonance,”<br />

in which incomplete ideas<br />

about the world and how it works<br />

are challenged by new information<br />

and experiences. Together, they<br />

solve problems and dilemmas that<br />

are encountered.<br />

For example, one afternoon<br />

Arturo was at the easel painting fall<br />

leaves. He painted a large yellow leaf<br />

on his paper and then proceeded to<br />

paint a red leaf above the first. Streaks<br />

of red paint ran down the paper and<br />

through the yellow leaf below.<br />

A look of shock appeared on<br />

Arturo’s face as he watched orange<br />

streaks appear on his yellow leaf. He<br />

quickly dabbed at the orange with<br />

his red paintbrush, trying to make<br />

the orange disappear. As he mixed<br />

more red paint with the yellow, he<br />

created even more orange. He was<br />

experiencing cognitive dissonance<br />

because the paint was not conforming<br />

to his mental construct about<br />

how paint works.<br />

The wise teacher<br />

knows when to let<br />

children work things<br />

out on their own.<br />

Teachers Are Diagnosticians<br />

Because curriculuming is viewed<br />

as a dynamic process that grows out<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 7

Nancy P. Alexander<br />

Careful listening and observation of children’s emotions inform the curriculuming process about the kinds of experiences and<br />

opportunities that motivate and engage children’s minds, and those that frustrate and discourage them.<br />

of the nature and needs of children,<br />

early childhood teachers<br />

must be diagnosticians who constantly<br />

assess strengths and weaknesses,<br />

staying close to and documenting<br />

students’ learning in<br />

order to inform the design of new<br />

learning experiences to come<br />

(Turner & Krechevsky, 2003). No<br />

textbook publisher or curriculum<br />

guide will ever know the strengths,<br />

weaknesses, and interests of young<br />

children as well as their teachers<br />

(Lederhouse, 2003).<br />

When teachers observe a lack of<br />

engagement or learning, the diagnosing<br />

begins with an inward<br />

look—“What am I doing that may<br />

be contributing to the situation?”<br />

Perhaps unrealistic expectations are<br />

the issue, or perhaps the adults have<br />

failed to develop authentic relationships<br />

with one or more children.<br />

After honest self-examinations,<br />

teachers begin to ask some hard<br />

questions about pedagogy: “Is the<br />

content appropriate for this particular<br />

child/group?” “Is there something<br />

in the environment that needs<br />

to be changed?” “Are the methods<br />

and strategies developmentally and<br />

culturally appropriate?” Perhaps a<br />

child lacks the background knowledge<br />

necessary to grasp new concepts<br />

and skills. Perhaps cultural<br />

issues affect a child’s learning.<br />

After introspective questions have<br />

been answered fully and honestly,<br />

attention can be turned to each<br />

child to determine if there are physical,<br />

emotional, or cognitive challenges<br />

that interfere with learning.<br />

Careful observation of each child is<br />

necessary to document any aspects<br />

of development that may be atypical.<br />

At this point it is often appropriate<br />

to enlist the aid of others with<br />

specific professional expertise.<br />

8 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

Teachers Are Reflective<br />

Practitioners<br />

The curriculuming process also<br />

hinges on every teacher’s ability and<br />

willingness to consistently reflect<br />

upon his/her own practice and the<br />

learning processes of the children<br />

(van Manen, 1995).<br />

Reflective practitioners have a conscious<br />

awareness of the underlying<br />

belief system that provides the foundation<br />

for their practice. Many times<br />

innovations are not put into practice<br />

because they conflict with deeply held<br />

internal images of how the world<br />

works, images that limit teachers to<br />

familiar ways of thinking and acting<br />

(Senge & Lannon-Kim, 1991).<br />

Reflective teachers strive to bring<br />

those internal images into conscious<br />

awareness so they can be openly examined.<br />

As the curriculuming process<br />

unfolds, reflective teachers continually<br />

ask two questions, “Why am I doing<br />

what I am doing? Is my practice congruent<br />

with my beliefs?” When inconsistencies<br />

between belief and practice<br />

are realized, adjustments must be<br />

made to bring them into alignment.<br />

Not only do implicit and explicit<br />

belief systems impact the curriculuming<br />

process, but personal emotions<br />

and values do so as well. For<br />

example, a teacher may have had<br />

very negative experiences with science.<br />

As a result, the curriculuming<br />

process is approached with an aversion<br />

to or fear of bringing science<br />

experiences into the classroom.<br />

On the other hand, a teacher<br />

may be determined that children in<br />

his or her care will have a very different<br />

experience and therefore<br />

strive to make science experiences<br />

the primary focus. Professionals at<br />

all levels examine the “baggage” they<br />

bring to the process and consciously<br />

choose the best course to follow.<br />

Teachers Are Learners<br />

The curriculuming process<br />

requires that teachers are also learners.<br />

Not only do teachers learn from<br />

children and from their questions<br />

and explorations, they learn from<br />

children’s families as well. To do so<br />

requires a great deal of humility. Parents<br />

are a source of valuable insights<br />

into individual children that inform<br />

the curriculuming process.<br />

Parents are seen as partners in the<br />

learning process, not just spectators.<br />

In a diverse society, teachers can no<br />

longer assume that children share<br />

the same culture, experiences, and<br />

values. Today, teachers take the time<br />

to understand the goals and values<br />

that parents hold for their children.<br />

They learn about the culture that<br />

has informed children’s views of the<br />

world and of school. Such information<br />

informs the content of the curriculuming<br />

process.<br />

Teachers are also learners.<br />

Assumptions About the<br />

Curriculuming Process<br />

Curriculum Is a Recursive,<br />

Spiraling Process<br />

Curriculuming is never fixed, linear,<br />

and unchanging. It is constantly<br />

emerging out of children’s needs and<br />

interests, embracing new ideas and<br />

directions, and letting go of those<br />

things that are no longer useful. It<br />

cannot be duplicated year after year,<br />

it is not something that can be put<br />

on a shelf and stored, but is created<br />

in response to the particular dynamics<br />

of a specific group of children. It<br />

is a process that is constantly inventing<br />

and reinventing itself.<br />

Ask divergent questions.<br />

Curriculum Relies on Assessment<br />

Teachers who curriculum begin<br />

by assessing children’s strengths and<br />

weaknesses, their prior knowledge<br />

and experiences, their needs and<br />

interests, and their ethnic and cultural<br />

backgrounds. Formal and<br />

informal assessment help answer<br />

the question, “Where do we go<br />

from here?”<br />

Oklahoma State’s curriculuming<br />

model is built on the assumption that<br />

teachers who are trained in child<br />

development and developmentally<br />

appropriate practice are crucial to the<br />

assessment process. Teacher assessment<br />

of authentic symbolic representations<br />

of learning and teacher observations<br />

drive curriculuming as well as<br />

the learning process.<br />

Curriculuming continues with<br />

assessment as teachers identify gaps<br />

in children’s knowledge, development,<br />

and understanding, and<br />

determine whether or not local,<br />

state, and national standards have<br />

been met. And the curriculuming<br />

process continues.<br />

Curriculuming Presumes<br />

an Underlying Confidence<br />

in Children<br />

A foundational principle of the<br />

curriculuming process is the belief<br />

that children tell astute observers<br />

what they need to learn. They speak<br />

to teachers through the gleams in<br />

their eyes as they strive and successfully<br />

complete a task. They speak<br />

through the slump of their shoulders<br />

as they struggle to master concepts<br />

for which they have no prior<br />

knowledge. And they speak with<br />

their voices as they proudly proclaim,<br />

“Teacher, look what I found!”<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 9

References<br />

Anderson, R. (2000). Rediscovering lost<br />

chords. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(5):<br />

402-405.<br />

Bredekamp, S., & Rosegrant, L. (1992).<br />

Reaching potentials: Appropriate<br />

curriculum and assessment for young<br />

children (Vol. 1). Washington, DC:<br />

National <strong>Association</strong> for the Education<br />

of Young Children.<br />

Bruer, J.T. (1999). The myth of the first<br />

three years: A new understanding of early<br />

brain development and lifelong learning.<br />

New York: Free Press.<br />

Curtis, D., & Carter, M. (2003). Designs<br />

for living and learning: Transforming<br />

early childhood environments. St. Paul,<br />

MN: Redleaf.<br />

Chaille, C. (2003). The young child as scientist:<br />

A constructivist approach to early<br />

childhood science education (3rd ed.).<br />

New York: Allyn & Bacon.<br />

Hendrick, J. (1997). First steps toward<br />

teaching the Reggio way. New York:<br />

Merrill.<br />

Lederhouse J.N. (2003). The power of one<br />

on one. Educational Leadership, 60,<br />

69-71.<br />

Meyer, R. (2002). Captives of the script:<br />

Killing us softly with phonics.<br />

Language Arts, 79(6): 452-462.<br />

Musinski, B. (1999). The educator as<br />

facilitator: A new kind of leadership.<br />

Nursing Forum, 34, 23-29.<br />

Ohanian, S. (1999). One size fits few.<br />

Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.<br />

Perry, B. (2004). Curiosity, the fuel of<br />

development. Retrieved on January 28,<br />

2003, from www.scholastic.com.<br />

Rogers, C., & Freiberg, H. (1994).<br />

Freedom to learn. New York: Macmillan.<br />

Senge, P., & Lannon-Kim, C. (1991).<br />

Recapturing the spirit of learning<br />

through a systems approach.<br />

The School Administrator, 48, 8-13.<br />

Sussna, A. (2000). A quest to ban cute—<br />

and make learning truly challenging.<br />

Dimensions, 28(2): 3-7.<br />

Turner, T., & Krechevsky, M. (2003).<br />

Who are the teachers? Who are the<br />

learners? Educational Leadership, 60,<br />

40-49.<br />

van Manen, M. (1995). On the epistemology<br />

of reflective practice. Teachers<br />

and teaching; theory and practice, vol. 1.<br />

London: Oxford Ltd.<br />

Menu for Successful Parent & Family Involvement<br />

written by Paul J. Wirtz and Bev Schumacher<br />

Getting parents involved in an early childhood program takes creativity, great<br />

ideas, and strategies that make it easy for parents to become involved.<br />

This SECA publication explores successful experiences in working with<br />

the families and helps you develop a “menu“ of activities and strategies<br />

that will promote parental involvement. The book includes ideas for all<br />

early childhood programs, including group settings and family homes.<br />

ISBN #0-942388-28-3<br />

$5.50 SECA Members<br />

$6.50 Non-members<br />

Plus S&H<br />

Call 1-800-305-7322<br />

to order today.<br />

Become a Volunteer Reviewer!<br />

Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> is a refereed journal. Three experts review each manuscript we publish. If you<br />

have an advanced degree and expertise in one or more areas of early childhood education, please contact SECA<br />

about serving as a volunteer reviewer.<br />

We will send you a reviewer form and details. Our goal is to send no more than two journal manuscripts to<br />

each person a year. All reviews are conducted anonymously and through e-mail.<br />

Contact SECA today about this valuable, convenient way that you can serve your professional association<br />

and journal:<br />

editor@southernearlychildhood.org<br />

10 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

Sow SEEDs for success! Examine the Structure of the family, Ethnic and<br />

cultural backgrounds, Economic status, and Differing abilities of children<br />

(SEEDs) to better understand and meet their individual needs.<br />

Drawings on the Wall:<br />

Children’s Insights for Defining Diversity<br />

Diana Nabors and Cynthia G. Simpson<br />

Tomorrow night is Parents’ Night. Ms. Vandroel envisions<br />

that her classroom walls will be filled with children’s art. She<br />

asks children to draw pictures of their families on large<br />

sheets of manila paper.<br />

Twenty 5-year-olds diligently begin drawing. As Ms. Vandroel<br />

walks around the room, several children stop her to<br />

show the beginnings of their creations. Suddenly, a loud discussion<br />

erupts at one table. Sarah is digging in the crayon<br />

basket. “Peach, peach, I can’t find the peach!”<br />

“What do you need a peach for?” Jose asks.<br />

Sara responds, “I need to color in my face. My mom bought<br />

me crayons at home. I use the peach to color me.”<br />

Jose comments, “You need to use white, cuz you’re white<br />

and I’m gunna use brown, cuz I’m brown. See?”<br />

Today’s diverse early childhood classrooms, such as<br />

the one depicted here, have led to new approaches to<br />

teaching. Classrooms are filled with children with not<br />

only ethnic diversity, but also variations in family structure,<br />

religious preferences, and economic status (Olsen<br />

& Fuller, 2003). In addition, with the reauthorization of<br />

the Individuals With Disabilities Act (1997), children<br />

with challenging academic and behavioral concerns are<br />

included in classrooms.<br />

Diversity is a far more complex concept than physical<br />

differences such as skin color. Children enter early childhood<br />

classrooms with many experiences that they have<br />

gained not only from their near environment and their<br />

immediate families, but also from the surrounding environment<br />

and extended families (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).<br />

As a result of these changes, teachers are facing their own<br />

cultural barriers as they strive to accommodate the academic<br />

and social needs of all children they teach. By examining the<br />

Structure of the family, Ethnic and cultural backgrounds,<br />

Economic status, and Differing abilities of students<br />

(SEEDs), teachers are better able to understand and meet the<br />

individual needs of young children.<br />

Each person defines family.<br />

Structure of the Family<br />

As a first step in examining the idea of family structure,<br />

it is helpful to explore one’s personal definitions of<br />

family. Some questions to ask oneself might include:<br />

“Who do I consider to be members of a family?” and<br />

“What functions does a family fulfill?” Teachers’ perceptions<br />

of family may coincide with or expand upon the<br />

definition of family used by the U.S. Bureau of the Census<br />

(2004b): A family is a group of two people or more<br />

(one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage,<br />

or adoption and residing together; all such people<br />

(including related subfamily members) are considered as<br />

members of one family.<br />

Children may watch television and read books that<br />

define family as a two-parent, two- or three-child household<br />

where the father works outside the home and the<br />

Diana Nabors, E.D., is Assistant Professor of <strong>Early</strong><br />

<strong>Childhood</strong> Education, Department of Language, Literacy<br />

and Special Populations, Sam Houston State University,<br />

Huntsville, Texas. She is faculty advisor for the Sam<br />

Houston <strong>Association</strong> for the Education of Young Children<br />

and teaches several courses in the area of family involvement<br />

and collaboration.<br />

Cynthia G. Simpson, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor of<br />

Special Education, Department of Language, Literacy<br />

and Special Populations, Sam Houston State University,<br />

Huntsville, Texas. She is the Treasurer and Vice-President<br />

of Public Policy-Elect for the Texas <strong>Association</strong> for the<br />

Education of Young Children. Simpson has presented<br />

and written several articles.<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 11

Subjects & Predicates<br />

Children are strongly influenced by how they perceive their families’ lifestyles and structures.<br />

mother works within the home<br />

(Fuller, 1992). This view of a family<br />

is embedded in the minds of many<br />

people in the United States as the<br />

“perfect” family. However, it is not<br />

the type of family that most children<br />

will draw in Ms. Vandroel’s classroom<br />

or similar classrooms across the<br />

country. In reality, less than 4% of<br />

families live in this type of traditional<br />

family (Proctor & Dalaker, 2003).<br />

As Ms. Vandroel viewed the<br />

portraits of her children’s families<br />

and remembered the conversations<br />

that took place in her classroom<br />

while the drawings were being<br />

made, her preconceived ideas of<br />

the outcomes of their creativity<br />

were challenged. She realized that<br />

who and what the children included<br />

or excluded in their pictures<br />

were strongly influenced by how<br />

they perceived their families’<br />

lifestyles and structures.<br />

When children were asked to<br />

depict their families, the freedom<br />

to draw led children to discuss<br />

and create their own definition<br />

of their families. A conversation<br />

between Jaylyn and<br />

Bethany revealed one example:<br />

“Well, I’m using brown on my<br />

dog,” insists Jaylyn.<br />

“You can’t draw a dog. You’re supposed<br />

to be drawing your family.<br />

Dogs are not family,” interjects<br />

Bethany.<br />

“My dog lives with me and my<br />

papa. He sleeps with me. Mo is<br />

TOO my family,” insists Jaylyn.<br />

Jaylyn did include his dog, Mo.<br />

Mo has been in his family for as long<br />

as Jaylyn can remember. At times,<br />

Mo has been Jaylyn’s best friend.<br />

Someone else might insist that<br />

Bethany not include her Aunt Beth<br />

in her family portrait, because she<br />

lives a few blocks away. What about<br />

Andy’s Aunt Eliza that he sees every<br />

year at Christmas? Then, there is<br />

Tyler; he lives with his grandma<br />

while his mother is in prison. This is<br />

the reality in Ms. Vandroel’s classroom,<br />

which is filled with children<br />

living in a variety of family structures<br />

that may be very different from<br />

the traditional definition of family.<br />

Each person defines family.<br />

Adults may include dear friends<br />

with whom they have close ties,<br />

even though these people lack connection<br />

to each other via the legal<br />

ties of marriage or adoption. Teachers<br />

may regard students as their class<br />

family. Distinct emotional bonds of<br />

love and support often bring nonrelatives<br />

into a near circle of family.<br />

Could it be time to revise the traditional<br />

definition of family?<br />

The sociological definition of a<br />

family is people who love and support<br />

another throughout the stresses<br />

and joys of life (Olsen & Fuller,<br />

2003). This definition doesn’t necessarily<br />

look at individuals in a family,<br />

but instead views the emotional<br />

bonds shared among people. These<br />

bonds may change in strength over<br />

time and with unique experiences.<br />

The need to consider the sociological<br />

definition of family is clear to<br />

all who toured the gallery of portraits<br />

in Ms. Vandroel’s classroom.<br />

Family portraits created by any<br />

group of children are likely to display<br />

children in two-parent households,<br />

children in single-parent<br />

households, children in multigenerational<br />

families including grandpar-<br />

12 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

ents and aunts, and children living<br />

with parents who have same-gender<br />

partners. However, one similarity<br />

exists in all of these images—each<br />

child is loved and cared for by at<br />

least one adult who has a reciprocal<br />

attachment with the child.<br />

often shared with extended families<br />

and friends. Each person borrows<br />

and adapts new experiences<br />

to add to their own, as they see fit.<br />

Understanding and accepting the<br />

uniqueness of each family can lead<br />

teachers to value and build on children’s<br />

differences and strengths<br />

(Stauss, 1995). The unique experiences<br />

and traditions of children<br />

and their families are what make<br />

them each special.<br />

Ethnic and Cultural<br />

Differences<br />

As each child’s portrait is further<br />

examined, an observant classroom<br />

visitor is likely to notice that there<br />

are also differences in family values,<br />

customs, religions, and beliefs. In the<br />

1700s the United States was thought<br />

of as a great melting pot of the world.<br />

People came from many distant<br />

lands to form a new country with the<br />

people who were already living on<br />

the continent, although not without<br />

much strife and controversy.<br />

Everywhere in the world that<br />

children enter classrooms, they<br />

bring with them the foundations<br />

laid by families who practice their<br />

own beliefs, views, and traditions.<br />

For instance, Maggie’s family portrait<br />

was delicately laced with vines<br />

creating a border around the drawing.<br />

They come to a close with a<br />

small, gold cross neatly centered<br />

above the picture. Maggie stated<br />

that the vines are the plant that her<br />

grandmother sent her last year. She<br />

waters it each day and thinks about<br />

Grandma who lives far away. The<br />

cross of gold is the cross that she will<br />

soon receive. Maggie says that when<br />

she gets “bigger” she will get her<br />

cross necklace on the day of her First<br />

Communion, just like her sister. She<br />

then goes on to explain how Grandma<br />

will get to visit for a whole week<br />

for her First Communion.<br />

As families live and communicate<br />

with each other, their customs,<br />

stories, and celebrations are<br />

Subjects & Predicates<br />

As families live and communicate with each other, their customs, stories, and<br />

celebrations are often shared with extended families and friends. Each person borrows<br />

and adapts new experiences to add to their own, as they see fit.<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 13

Joey’s mom rides in cycling races.<br />

She raced before Joey was born<br />

and continues to ride. Joey has<br />

had the opportunity to travel with<br />

her to races around the country.<br />

This year, his mom is racing in<br />

France. Joey is staying at home<br />

with his dad.<br />

Ms. Vandroel, the class, and Joey<br />

look forward to the e-mails and<br />

pictures that Joey’s mom will send<br />

during her stay in France. The<br />

class has the opportunity to support<br />

Joey through any stresses or<br />

sadness of his Mom being gone as<br />

well as sharing the excitement of<br />

the race.<br />

Ms. Vandroel plans ways to highlight<br />

the special occasions in each<br />

child’s life. She wants children to<br />

have opportunities to share their<br />

experiences of visiting family members,<br />

traditions, and family activities.<br />

The more she learns and understands<br />

about each child, the more<br />

she will be able to assist children in<br />

their learning and growing process.<br />

Economic differences<br />

may affect children’s<br />

self-esteem and<br />

social acceptance.<br />

Economic Diversity<br />

Children’s clothing, their behavior,<br />

and their life experiences are<br />

often linked to their family’s<br />

income. Income has a major impact<br />

on families, their values, and the<br />

experiences that they have. The<br />

poverty rate and number of families<br />

in the United States living in poverty<br />

increased from 9.6% and 7.2<br />

million in 2002 to 10% and 7.6<br />

million in 2003 (U.S. Bureau of the<br />

Census, 2004a).<br />

Single females head many of<br />

these families. Those who have a<br />

limited education struggle to maintain<br />

a job and provide good-quality<br />

care for their children. Individual<br />

states assist with providing job training,<br />

education, child care, and transportation<br />

to help families. But this<br />

assistance is only temporary. The<br />

family must leave the rolls within 5<br />

years and remain economically independent.<br />

Parents struggle as they<br />

seek jobs, knowing that many entrylevel<br />

jobs have been eliminated.<br />

After they find a job, they are also<br />

hit with the fact that waiting lists<br />

exist for child care vouchers to assist<br />

them. Jane O’Leary of the Maryland<br />

Alliance for the Poor said it best,<br />

“Families on welfare are particularly<br />

fragile. They have tenuous housing<br />

and day-care arrangements. They<br />

have no assets to sell.... A sore throat<br />

or a flat tire or a snowstorm can be<br />

devastating” (Otto, 2003).<br />

Single parents face a multitude<br />

of stresses in their lives that can<br />

affect young children. Ms. Vandroel’s<br />

class, like so many across the<br />

United States, includes children<br />

from a variety of economic levels<br />

who work and learn together. Differences<br />

in economic status may<br />

affect children’s self-esteem and<br />

social acceptance. Economic differences<br />

may be demonstrated in children’s<br />

differing knowledge and<br />

problem-solving experiences. It is<br />

all too common to find a child<br />

whose family lives in a vehicle.<br />

Unfortunately, the car doesn’t run<br />

and the family doesn’t travel.<br />

Some teachers may incorrectly<br />

assume that all families who rarely<br />

are involved with their children’s<br />

school lack interest in education. A<br />

family’s ability and willingness to<br />

participate in school activities often<br />

depends on the availability of transportation<br />

and flexibility in work<br />

schedules. Parents who work at<br />

lower-paying, hourly jobs may not<br />

have the flexibility to revise their<br />

work schedules in order to participate<br />

as fully as they wish.<br />

Reaching out to families living in<br />

poverty creates new challenges for<br />

teachers. Understanding the growing<br />

numbers of families living in<br />

poverty, and seeking to assist these<br />

families, can offer hope to children<br />

who may be struggling not because<br />

of cognitive disabilities, but rather<br />

due to lack of experiences that support<br />

their educational growth (Children’s<br />

Defense Fund, 1994).<br />

See human differences<br />

as assets.<br />

Differing Abilities<br />

The early childhood years are a<br />

time of rapid growth and development.<br />

This growth is shaped by children’s<br />

experiences and influenced by<br />

their physical, emotional, and intellectual<br />

abilities. The variety of family<br />

pictures that Ms. Vandroel collected<br />

ranged from simple spiderlike<br />

line drawings of family members<br />

to explicitly detailed representations<br />

of each family member.<br />

The differing levels of representation<br />

found among children’s drawings<br />

remind teachers that children<br />

possess diverse levels of cognitive,<br />

social, and physical abilities. The disconnected<br />

bubble and stick figure<br />

family that Casey drew clearly indicates<br />

the value of further occupational<br />

therapy as specified in Casey’s<br />

Individualized Education Program.<br />

Children’s abilities are displayed<br />

not only through the shapes and<br />

lines they draw, but also in the stories<br />

that their pictures tell. In<br />

Billy’s family picture, the viewer is<br />

drawn to a small corner of the<br />

14 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

home, which is Billy’s room. Sitting<br />

on the nightstand is an<br />

oblong-shaped container with long<br />

tubes coming from it. From the<br />

oversize drawing of the container it<br />

is evident that this fixture represents<br />

a large portion of Billy’s life.<br />

Those who know Billy would<br />

understand that this oblong container<br />

is an oxygen tank similar to<br />

the one Billy uses at school.<br />

Billy is medically fragile. He has<br />

limited use of his left hand and is<br />

confined to a wheelchair. Most of<br />

his time is spent at home. Two days<br />

a week, if the weather is good and<br />

Billy is healthy, Billy comes to<br />

school. Most days are filled with visits<br />

to the hospital and interactions<br />

with nurses and a home-school<br />

teacher. The hospital has been part<br />

of his life since he can remember.<br />

With the reauthorization of the<br />

Individuals With Disabilities Act<br />

of 1997 and the move toward<br />

more inclusive environments, children<br />

with a broad range of intellectual,<br />

social, and physical abilities<br />

are now educated together in<br />

inclusive settings (Couchenour &<br />

Chrisman, 2004).<br />

The activity that Ms. Vandroel<br />

envisioned as a display for Parents’<br />

Night opened the door of opportunity<br />

for her to expand parents and<br />

children’s perceptions about individuality<br />

and the uniqueness of<br />

one’s own experiences, families,<br />

and lives. Her goal was not to single<br />

out individual differences as<br />

negative aspects, but to enable each<br />

person to see those differences as<br />

assets. As a bridge from this activity,<br />

she planed to continue to guide<br />

her students to establish positive<br />

relationships with one another.<br />

Like most teachers, Ms. Vandroel<br />

understands that diversity is leading<br />

Elisabeth Nichols<br />

The differing levels of representation found among children’s drawings remind teachers<br />

that children possess diverse levels of cognitive, social, and physical abilities.<br />

to changes in teaching methods and<br />

in the ways that relationships among<br />

families, children, and teachers are<br />

nurtured. Even so, teachers remain<br />

steadfast in their commitment to<br />

families and children.<br />

• They value and respect each family<br />

and their own views and beliefs<br />

while maintaining professional<br />

responsibilities to each child.<br />

• They promote partnerships<br />

with families that focus on<br />

two-way communication and<br />

encourage participation within<br />

the school.<br />

• And lastly, they link parents and<br />

families to resources that may<br />

assist them as they rear their<br />

children. The most effective<br />

teachers accept children’s individual<br />

differences and establish<br />

relationships among families<br />

with a variety of SEEDs.<br />

Spring/Summer 2005 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Volume 33, Number 2 15

References<br />

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of<br />

human development: Experiments by<br />

nature and design. Cambridge, MA:<br />

Harvard University Press.<br />

Children’s Defense Fund. (1994). Writing<br />

America’s future. Washington, DC:<br />

Author.<br />

Couchenour, D.L., & Chrisman, K.<br />

(2004). Families, schools, and communities:<br />

Together for young children (2nd ed.).<br />

Albany, NY: Delmar Thompson.<br />

Fuller, M.L. (1992). The many faces of<br />

American families: We don’t look like<br />

the Cleavers anymore. PTA Today,<br />

18(1): 8-9.<br />

Olsen, G., & Fuller, M.L. (2003). Homeschool<br />

relations: Working successfully with<br />

parents and families (2nd ed.). Boston:<br />

Pearson Education, Inc.<br />

Otto, M. (2003). Welfare rolls rise in<br />

area as governments confront cuts.<br />

Washington Post, March 10, 2003.<br />

Retrieved February 4, 2005, from<br />

http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/<br />

wpdyn?pagename=article&contentId=<br />

A2659-2003Mar9.html<br />

Proctor, B.D., & Dalaker, J. (2003).<br />

U.S. Census Bureau Current Population<br />

Reports P 60-222: Poverty in the United<br />

States: 2002. Washington, DC: U.S.<br />

Government Printing Office.<br />

Stauss, J.H. (1995). Reframing and<br />

refocusing American Indian family<br />

strengths. In C.K. Jacobson (Ed.),<br />

American families: Issues in race and<br />

ethnicity. New York: Garland.<br />

U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2004). News<br />

Reports: August 26, 2004 (Press<br />

Release). Income stable, poverty up,<br />

numbers of Americans with and without<br />

health insurance rise, Census<br />

Bureau reports. Retrieved January 30,<br />

2005, from http://www.census.gov/<br />

PressRelease/www/releases/archives/<br />

income_wealth/002484.html<br />

U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division,<br />

Fertility & Family Statistics Branch.<br />

(2004). Retrieved January 31, 2005,<br />

from http://www.census.gov/<br />

population/www/cps/cpsdef.html<br />

POSITION ANNOUNCEMENT<br />

Velma E. Schmidt Endowed Chair—<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Education<br />

Department of Counseling, Development, and Higher<br />

Education Program in Development, Family Studies,<br />

and <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Education<br />

Position: Velma E. Schmidt Endowed Chair in<br />

<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Education<br />

This position is a five year renewable contract appointment beginning<br />

fall semester 2005, in the program of Development, Family Studies,<br />

and <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Education.<br />

Rank and Salary: Professor of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Education. Salary<br />

commensurate with background and experience. Research support and<br />

travel will be provided as a part of the appointment.<br />

Responsibilities: This position requires the ability to cooperate<br />

and collaborate across interdisciplinary settings. Responsibilities<br />

include, but are not limited to: (1) Teach and advise graduate and,<br />

teaching undergraduate students (2) Participate in Departmental, Program,<br />

and College committees (3) Mentor junior faculty (4) Collaborate<br />

in a nationally recognized doctoral program in early childhood<br />

education (5) Align personal and professional research and services with<br />

the goals of the University, College of Education, and the Program area.<br />

Academic and Professional Qualifications: (1) A nationally recognized<br />

record of research, scholarly writing, and professional presentations<br />

(2) A strong record of working with doctoral students (3) A commitment<br />

to teaching and mentoring doctoral students preparing for<br />

leadership positions in colleges and universities (4) A demonstrated<br />

ability to obtain external funding for research and program developmental<br />

activities (5) A willingness to work with University and community<br />

agencies in a collaborative fashion (6) An earned doctorate in <strong>Early</strong><br />

<strong>Childhood</strong> Education or appropriate related field.<br />

The University: The University of North Texas is a nationally recognized<br />

metropolitan research institution with over 30,000 students,<br />

one-third of whom are graduate students. UNT is located in the<br />

vibrant and rapidly expanding Denton-Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex.<br />

Application Procedure: Applicants should provide a letter of<br />

application, a complete curriculum vita, official transcripts, and three<br />

letters of reference to:<br />

George S. Morrison, Ed.D. • Linda C. Schertz, Ed.D.<br />

Development, Family Studies, and <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong> Education<br />

University of North Texas • P.O. Box 310829<br />

Denton, TX 76203-0829<br />

Phone: (940) 565-2045 • Fax (940) 369-7177<br />

Application Deadline: Review of applications will continue until<br />

the position is filled.<br />

The University of North Texas is an AA/ADA/EOE and encourages<br />

applications from women and minorities, as it is committed to creating<br />

an ethnically and culturally diverse community. The College of Education<br />

welcomes applications from minority group members, women, and<br />

others whose background may further diversify faculty ideas, attitudes,<br />

and experiences.<br />

16 Volume 33, Number 2 DIMENSIONS OF EARLY CHILDHOOD Spring/Summer 2005

Call for Manuscripts<br />

for<br />

Theme Issue of Dimensions Fall 2006<br />

The Fall 2006 issue of Dimensions of <strong>Early</strong><br />

<strong>Childhood</strong> will be a theme issue. Members and<br />

friends of the <strong>Southern</strong> <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong><br />

<strong>Association</strong> are encouraged to submit proposals<br />

for manuscripts to be published in this issue.<br />

The topic is:<br />

From Biters to Bullies to Bullets:<br />

Guiding Positive Prosocial Behavior<br />

The importance of prosocial behaviors and<br />

positive guidance as an integral part of the early<br />

childhood social/emotional curriculum—from<br />

toddlers who bite, to the older child who bullies—will<br />

be addressed in this theme issue. The<br />

Guest Editors are seeking manuscripts that<br />

address the following topics for toddlers<br />

through 3rd grade:<br />

• <strong>Early</strong> relationships (attachment, trust, etc.) as a<br />

cornerstone for prosocial and positive behaviors.<br />

Brain research and social/emotional development<br />

research that “set the stage” for the emphasis in<br />

early childhood.<br />

• Practical early support for promoting prosocial<br />

and respectful interpersonal relationships<br />

in the early childhood setting.<br />

• Appropriate positive support and guidance<br />

for aggressive behaviors including biting and<br />

bullying.<br />

• Resiliency theory with practical applications.<br />

• Conflict resolution, play therapy, music<br />

therapy, bibliotherapy, and other programs<br />

appropriately addressing the theme.<br />