Boston Symphony Orchestra Charles Munch - International ...

Boston Symphony Orchestra Charles Munch - International ...

Boston Symphony Orchestra Charles Munch - International ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

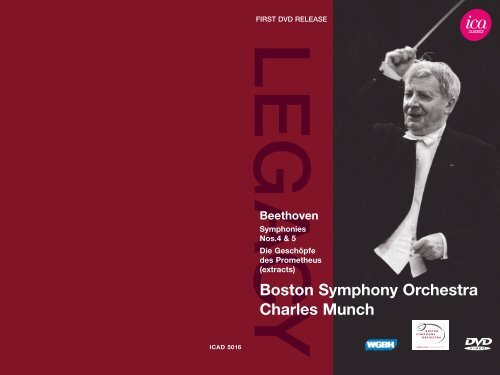

FIRST DVD RELEASE<br />

Beethoven<br />

Symphonies<br />

Nos.4 & 5<br />

Die Geschöpfe<br />

des Prometheus<br />

(extracts)<br />

<strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

<strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong><br />

ICAD 5016<br />

s

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770–1827<br />

Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus, op.43 (extracts)<br />

The Creatures of Prometheus · Les Créatures de Prométhée<br />

1 Ouverture: Adagio — Allegro molto con brio 5.30<br />

2 No.5: Adagio — Andante quasi allegretto 8.43<br />

3 No.16: Finale: Allegretto — Allegro molto 5.47<br />

Directed by David M. Davis<br />

Produced by Jordan M. Whitelaw<br />

Recorded: Sanders Theatre, Harvard University, 8 March 1960<br />

π & © 1960, 2011 <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> & WGBH Educational Foundation<br />

Taken from a broadcast produced by the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> in association<br />

with Seven Arts Associated Corp.<br />

Digitisation by Safe Sound Archive<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No.4 in B flat major, op.60<br />

4 I Adagio — Allegro vivace 10.53<br />

5 II Adagio 9.14<br />

6 III Allegro vivace 4.48<br />

7 IV Allegro ma non troppo 5.39<br />

Directed by David M. Davis<br />

Produced by Jordan M. Whitelaw<br />

Recorded: Sanders Theatre, Harvard University, 18 April 1961<br />

π & © 1961, 2011 <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> & WGBH Educational Foundation<br />

Taken from a broadcast produced by the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> in association<br />

with Seven Arts Associated Corp.<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No.5 in C minor, op.67<br />

8 I Allegro con brio 6.42<br />

9 II Andante con moto 11.37<br />

10 III Allegro — 5.11<br />

11 IV Allegro 8.41<br />

Directed by David M. Davis<br />

Produced by Jordan M. Whitelaw<br />

Recorded: Sanders Theatre, Harvard University, 3 November 1959<br />

π & © 1959, 2011 <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> & WGBH Educational Foundation<br />

Original broadcast produced by the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> in association with the<br />

Lowell Institute Cooperative Broadcasting Council, WGBH TV, <strong>Boston</strong>, and NERTC (National<br />

Educational Radio and Television Center)<br />

Digitisation by Safe Sound Archive<br />

<strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

CHARLES MUNCH<br />

For ICA Classics<br />

Executive Producer: Stephen Wright<br />

Head of DVD: Louise Waller-Smith<br />

Executive Consultant: John Pattrick<br />

Music Rights Executive: Aurélie Baujean<br />

ICA Classics gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Jean-Philippe Schweitzer and Pierre-Martin Juban<br />

For <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Historical:<br />

Music Director: <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong><br />

Manager: Thomas D. Perry<br />

President, Board of Trustees: Henry B. Cabot<br />

2011:<br />

Managing Director: Mark Volpe<br />

Artistic Administrator: Anthony Fogg<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> Manager: Ray Wellbaum<br />

Senior Archivist: Bridget Carr<br />

For WGBH Educational Foundation<br />

2011:<br />

WGBH Media Library and Archives Manager: Keith Luf<br />

PBS Distribution Counsel: Jeff Garmel<br />

DVD Studio Production<br />

DVD Design & Development: msm-studios GmbH<br />

Producer: Johannes Müller<br />

Screen Design: Hermann Enkemeier<br />

DVD Authoring & Video Encoding: Jens Saure<br />

Audio Postproduction & Encoding: Sven Mevissen<br />

Video Postproduction: Michael Hartl<br />

Project Management: Jakobus Ciolek<br />

DVD Packaging<br />

Product Management: Helen Forey for WLP Ltd<br />

Booklet Editing: Sue Baxter for WLP Ltd<br />

Introductory Note & Translations © 2011 <strong>International</strong> Classical Artists Ltd<br />

Cover Photo: Joe Covello<br />

Art Direction: Georgina Curtis for WLP Ltd<br />

π & ç 2011 <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> & WGBH Educational Foundation under exclusive licence to <strong>International</strong> Classical Artists Ltd<br />

ç 2011 The copyright in the design, development and packaging of this DVD is owned by <strong>International</strong> Classical Artists Ltd<br />

ICA CLASSICS is a division of the management agency <strong>International</strong> Classical Artists Ltd (ICA). The label features archive material<br />

from sources such as the BBC, WDR in Cologne and the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>, as well as performances from the agency’s own<br />

artists recorded in prestigious venues around the world. The majority of the recordings are enjoying their first commercial release.<br />

The ICA Classics team has been instrumental in the success of many audio and audiovisual productions over the years, including<br />

the origination of the DVD series The Art of Conducting, The Art of Piano and The Art of Violin; the archive-based DVD series<br />

Classic Archive; co-production documentaries featuring artists such as Richter, Fricsay, Mravinsky and Toscanini; the creation of<br />

the BBC Legends archive label, launched in 1998 (now comprising more than 250 CDs); and the audio series Great Conductors<br />

of the 20th Century produced for EMI Classics.<br />

WARNING: All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting<br />

prohibited. Licences for public performance or broadcasting may be obtained from Phonographic Performance Ltd.,<br />

1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9DE. In the United States of America unauthorised reproduction of this recording<br />

is prohibited by Federal law and subject to criminal prosecution.<br />

Made in the EU<br />

2<br />

3

CHARLES MUNCH CONDUCTS BEETHOVEN<br />

Between 1955 and 1979, <strong>Boston</strong>’s public television station WGBH televised more than one hundred<br />

and fifty live concerts by the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>. Four music directors were featured in the<br />

series — <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong>, Erich Leinsdorf, William Steinberg and Seiji Ozawa —, as well as a dozen<br />

prominent guest conductors.<br />

More than a hundred of these performances survive in the archives of the station and of the <strong>Boston</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>. Because they exist in several generations of various media and have been surrounded by<br />

legal issues, access has been impossible even for researchers, let alone for the interested musical<br />

public. The present series of DVDs will make many of these performances available for the first time<br />

since they went out on air.<br />

Music director <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong> launched the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> into television in 1955. He<br />

was a charismatic personality well suited to the new medium — with his sturdy build, shock of<br />

white hair and mischievous smile, it is no wonder than some mink-clad musical matrons from<br />

<strong>Boston</strong>’s Back Bay dubbed him ‘le beau <strong>Charles</strong>’.<br />

His appointment to the <strong>Boston</strong> position in 1949 brought him to the summit of his career. He was by<br />

then fifty-eight years old, but only in his seventeenth season as a conductor; <strong>Munch</strong> made his first<br />

appearance on the podium at the age of forty-one, in 1932, after spending many years as a<br />

professional violinist. He studied with two of the most eminent teachers of the era, Lucien Capet in<br />

France and Carl Flesch in Berlin, and served as concertmaster of orchestras in Cologne and Leipzig,<br />

working under such conductors as Wilhelm Furtwängler and Bruno Walter.<br />

During his thirteen years as music director in <strong>Boston</strong>, <strong>Munch</strong> explored a wide range of repertoire<br />

from the Baroque (Bach was a particular passion) to the contemporary. He led sixty-eight world<br />

premieres or American premieres there, the last of them being Leonard Bernstein’s <strong>Symphony</strong> No.3,<br />

Kaddish, while the composer looked on from the balcony. His greatest renown, however, came for<br />

his performances of French music by Berlioz, Debussy, Saint-Saëns and Ravel, as well as such<br />

living composers as Honegger, Roussel, Poulenc and Dutilleux. His activities as a recording<br />

conductor spanned more than three decades (1935–68), and some of the recordings of French<br />

repertoire that he made with the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> have sold steadily for fifty years and<br />

more and remain a permanent standard of reference.<br />

The long-playing record made recording all nine Beethoven symphonies a badge of honour for many<br />

conductors (several of whom, like Herbert von Karajan and Bernard Haitink, have recorded the cycle<br />

over and over again). <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong> was one of the conducting heroes of the LP era, but he<br />

recorded only six Beethoven symphonies with the <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> (Nos.1, 3, 5, 6, 7,<br />

and 9). At various other times between 1947 and 1967 he recorded four symphonies with other<br />

orchestras (Nos.3, 4, 6 and 8), but you still couldn’t assemble a complete set because there doesn’t<br />

seem to be a recording of No.2, a piece <strong>Munch</strong> conducted with the BSO on only one occasion. In<br />

<strong>Boston</strong> he never programmed a full Beethoven symphony cycle.<br />

Various overtures appeared on <strong>Munch</strong>’s programmes with some frequency, but the suite from<br />

Beethoven’s ballet The Creatures of Prometheus on this disc is a rarity, because he conducted it at<br />

the BSO in only one season — four performances in all.<br />

The ballet was a success for Beethoven at first; there were sixteen performances in its initial season.<br />

But the choreographer and his work passed from fashion, and most of the music descended into<br />

oblivion except for the overture, which has always been a concert-hall staple. <strong>Munch</strong> chose to<br />

supplement this with two additional movements that are less often heard (Beethoven wrote sixteen<br />

movements in all). The elegant Andante quasi allegretto served as a showcase for several of his<br />

celebrated BSO principal players — flautist Doriot Anthony Dwyer, cellist Samuel Mayes, bassoonist<br />

Sherman Walt, and harpist Bernard Zighera (this is the only music Beethoven ever composed for<br />

harp). <strong>Munch</strong> encourages his soloists without ever interfering with them.<br />

The jubilant theme of the finale is music that Beethoven returned to on two occasions: in a set of<br />

variations for solo piano with a concluding fugue (op.35) and, of course, the finale of the ‘Eroica’<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>. <strong>Munch</strong> seems to enjoy all the dodgy opera buffa departures from the more familiar<br />

versions of the music.<br />

He gives the Fourth <strong>Symphony</strong> a trim, fiery performance that is a lot of fun. His control of the<br />

transition between the first movement’s Adagio introduction, so full of strange portent, and the main<br />

Allegro vivace, is superbly imaginative, and the whole thing takes wing without ever turning beaty<br />

and bangy. The scherzo is both gracious and exciting, and the finale is exhilarating — Walt handles<br />

the famously tricky bassoon lick with élan.<br />

<strong>Munch</strong> led the iconic Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> with the BSO on thirty-four occasions, but only thirteen of them<br />

were in <strong>Boston</strong> or at Tanglewood — it was a favourite choice for touring. This blazing performance from<br />

Sanders Theatre at Harvard University in 1959 still sounds as exciting as the demonstrative audience<br />

found it then. It offers a superb display of virtuosity on the podium and on the platform. <strong>Munch</strong><br />

conducts with the freedom of a top-flight soloist because he knows the orchestra can and will deliver<br />

anything he asks for. Flexible tempos but unfaltering rhythm and forward momentum characterise his<br />

approach. He is able to redirect rather than sap the flow of energy in the quiet music, which maintains<br />

extraordinary weight and density. And when the climaxes come, they are thrilling not only in and of<br />

themselves but also because they have been prepared, not anticipated — and the effect is one<br />

of spontaneous combustion. <strong>Munch</strong>’s involvement is palpable, and you can hear him growl before<br />

launching the final triumph. What we take away from watching him is the sheer contagious pleasure<br />

he takes in the music and in the very act of conducting. By controlling the music, he sets it free.<br />

4 5

Ralph Gomberg is eloquent in the famous little oboe solo, and there are several close-ups of the<br />

third stand of first violins. <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> connoisseurs will recognise the intense, dark-haired<br />

man sitting on the outside — the twenty-seven-year-old Joseph Silverstein, who within three years<br />

would succeed Richard Burgin as concertmaster and assistant conductor, a position Silverstein<br />

would hold with high distinction for twenty-two seasons.<br />

Every summer the BSO sponsors an eight-week academy for advanced musical training. Leonard<br />

Bernstein, Christoph von Dohnányi, Claudio Abbado, Seiji Ozawa, and Lorin Maazel are among the<br />

programme’s alumni. Recently the three members of the 2010 conducting seminar spent an afternoon<br />

watching some of the <strong>Munch</strong> performances. ‘In every piece he is a different conductor’, one of the<br />

fellows exclaimed. Another responded with a question: ‘Isn’t that the way it’s supposed to be?’<br />

CHARLES MUNCH DIRIGE BEETHOVEN<br />

Richard Dyer<br />

Entre 1955 et 1979, la chaîne de télévision publique bostonienne WGBH diffusa plus de cent<br />

cinquante concerts de l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong>. Cette série d’émissions faisait intervenir<br />

quatre directeurs musicaux de l’orchestre — <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong>, Erich Leinsdorf, William Steinberg et<br />

Seiji Ozawa —, ainsi qu’une douzaine de chefs invités de premier plan.<br />

Plus d’une centaine de ces interprétations sont conservées dans les archives de la chaîne et dans<br />

celles de l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong>, mais comme elles se présentent sur plusieurs<br />

générations de supports différents et sont hérissées de problèmes juridiques, il était impossible aux<br />

chercheurs d’y accéder, sans même parler des mélomanes qu’elles étaient susceptibles d’intéresser.<br />

La présente série de DVD met bon nombre de ces documents à la disposition du public pour la<br />

première fois depuis leur retransmission télévisée.<br />

C’est en 1955 que le directeur musical <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong> offrit sa première télédiffusion à l’Orchestre<br />

symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong>. Sa personnalité charismatique semblait faite pour ce nouveau medium :<br />

avec sa robuste stature, sa crinière de cheveux gris et son sourire malicieux, on ne s’étonnera pas<br />

que certaines matrones en fourrure de Back Bay, le quartier huppé de <strong>Boston</strong>, l’aient surnommé “le<br />

beau <strong>Charles</strong>”.<br />

Sa nomination à <strong>Boston</strong> en 1949 fut le couronnement de sa carrière. Il était alors âgé de cinquantehuit<br />

ans, mais n’en était qu’à sa dix-septième saison de chef d’orchestre : <strong>Munch</strong> dirigea pour la<br />

première fois à quarante et un ans, en 1932, après avoir été violoniste professionnel pendant de<br />

nombreuses années. Il avait étudié avec deux des plus éminents professeurs de l’époque, Lucien<br />

Capet en France et Carl Flesch à Berlin, et avait été premier violon dans des orchestres de Cologne<br />

et de Leipzig, travaillant avec des chefs tels que Wilhelm Furtwängler et Bruno Walter.<br />

Pendant les treize années où il fut directeur musical à <strong>Boston</strong>, <strong>Munch</strong> explora les répertoires les plus<br />

divers, du baroque (il avait un faible pour Bach) au contemporain. Il y dirigea soixante-huit créations<br />

mondiales ou américaines, dont la dernière fut la Symphonie n° 3 Kaddish de Leonard Bernstein —<br />

le compositeur y assista, assis au balcon. Toutefois, <strong>Munch</strong> était surtout réputé pour ses<br />

interprétations de musique française, dirigeant des pages de Berlioz, Debussy, Saint-Saëns et Ravel,<br />

ainsi que de compositeurs vivants tels que Honegger, Roussel, Poulenc et Dutilleux. Ses activités de<br />

chef d’orchestre au disque couvrirent plus de trois décennies (1935–1968), et les ventes de certains<br />

enregistrements d’œuvres françaises qu’il réalisa avec l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> se<br />

poursuivent depuis cinquante ans, leur statut de références ne s’étant jamais démenti.<br />

Le 33 tours a fait de l’enregistrement de l’intégrale des symphonies de Beethoven un point<br />

d’honneur pour de nombreux chefs d’orchestre ; plusieurs d’entre eux, comme Herbert von Karajan<br />

et Bernard Haitink, ont d’ailleurs enregistré le cycle à maintes reprises. <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong> fut l’un des<br />

chefs d’orchestre emblématiques de l’ère du LP, mais il ne grava que six des symphonies<br />

beethovéniennes avec l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> (les N os 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, et 9). À plusieurs<br />

autres époques de 1947 à 1967, il grava quatre symphonies (les N os 3, 4, 6 et 8) avec des<br />

ensembles différents, mais malgré tout il n’enregistra pas la Deuxième et ne la dirigea avec<br />

l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> qu’à une seule occasion. À <strong>Boston</strong>, il ne programma jamais de<br />

cycle intégral des symphonies de Beethoven.<br />

Plusieurs ouvertures figurèrent assez fréquemment sur les programmes de <strong>Munch</strong>, mais la suite tirée<br />

du ballet de Beethoven Les Créatures de Prométhée proposée sur ce disque est une rareté, car le<br />

chef ne la dirigea que lors d’une seule saison de l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> pour un total<br />

de quatre exécutions.<br />

Le ballet fut d’abord un succès pour Beethoven, avec seize représentations lors de sa saison<br />

inaugurale, mais le chorégraphe et son ouvrage passèrent de mode, et la plupart des pages de la<br />

partition sombrèrent dans l’oubli, à l’exception de l’ouverture, qui s’est maintenue au répertoire des<br />

salles de concert. <strong>Munch</strong> choisit de lui adjoindre deux autres mouvements moins connus (au total,<br />

Beethoven en avait écrit seize). L’élégant Andante quasi allegretto était l’occasion de mettre en valeur<br />

les talents de plusieurs des fameux chefs de pupitre de l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> : la<br />

flûtiste Doriot Anthony Dwyer, le violoncelliste Samuel Mayes, le bassoniste Sherman Walt et le<br />

harpiste Bernard Zighera (c’est d’ailleurs la seule page jamais composée pour la harpe par<br />

Beethoven). <strong>Munch</strong> encourage ses solistes et leur laisse toute liberté de s’exprimer.<br />

Beethoven revint à deux reprises au thème jubilatoire du finale, d’abord dans une série de variations<br />

pour piano seul conclue par une fugue (op. 35) et bien sûr, dans le finale de la Symphonie<br />

“Héroïque”. <strong>Munch</strong> semble savourer les différences insolites qui démarquent cette page des<br />

versions plus connues et ne sont pas sans évoquer l’opera buffa.<br />

Il offre de la Quatrième Symphonie une lecture dépouillée et fiévreuse, très divertissante. Sa maîtrise<br />

6 7

de la transition entre l’introduction de l’Adagio du premier mouvement, si pleine d’étranges<br />

pressentiments, et l’Allegro vivace principal, est magnifiquement imaginative, et l’ensemble prend<br />

son envol sans jamais devenir métronomique et cacophonique. Le scherzo est à la fois gracieux et<br />

stimulant, et le finale est grisant — Walt aborde avec élan le solo de basson, notoirement difficile.<br />

<strong>Munch</strong> dirigea l’emblématique Cinquième Symphonie avec l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> à<br />

trente-quatre occasions, mais seulement treize fois à <strong>Boston</strong> ou à Tanglewood; en effet, c’était sa<br />

symphonie préférée pour les programmes de tournée. Captée au Sanders Theatre de l’Université de<br />

Harvard en 1959, cette flamboyante exécution fait le même effet à celui qui la visionne qu’au public<br />

d’alors, galvanisé et démonstratif. Elle offre un superbe déploiement de virtuosité, sur l’estrade et<br />

sur la scène. <strong>Munch</strong> dirige avec la liberté d’un soliste de haut vol, car il sait l’orchestre capable de<br />

faire tout ce qu’il lui demande. Son approche se caractérise par des tempos flexibles mais un rythme<br />

immuable. Au lieu de le saper, il parvient à canaliser le flux d’énergie des passages paisibles, qui<br />

conservent un poids et une densité extraordinaires. Et lorsque les points culminants sont atteints, ils<br />

ne sont pas seulement grisants pour et par eux-mêmes, mais aussi parce qu’ils ont été préparés (et<br />

non annoncés), faisant l’effet d’une combustion spontanée. L’engagement de <strong>Munch</strong> est palpable, et<br />

il pousse un grognement avant de déchaîner le triomphe final. À le contempler, nous ressentons le<br />

plaisir contagieux que lui procurent cet ouvrage et le simple fait de diriger l’orchestre. En contrôlant<br />

la musique, il lui laisse toute sa liberté.<br />

Ralph Gomberg se montre éloquent dans le célèbre petit solo de hautbois, et plusieurs gros plans<br />

sur la troisième rangée des premiers violons permettront aux spécialistes de l’Orchestre<br />

symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> de reconnaître sur l’un des bords un jeune homme aux cheveux bruns et<br />

au regard pénétrant : il s’agit de Joseph Silverstein, alors âgé de vingt-sept ans, et qui allait succéder<br />

trois ans plus tard à Richard Burgin en tant que premier violon et chef adjoint. Au fil de vingt-deux<br />

saisons, Silverstein allait se distinguer dans ces fonctions.<br />

Chaque été, l’Orchestre symphonique de <strong>Boston</strong> parraine un stage de perfectionnement musical, qui<br />

a compté Leonard Bernstein, Christoph von Dohnányi, Claudio Abbado, Seiji Ozawa et Lorin Maazel<br />

au nombre de ses participants. Il y a peu, les trois membres du séminaire de direction d’orchestre<br />

de l’été 2010 ont passé un après-midi à visionner certaines des prestations de <strong>Munch</strong>. “À chaque<br />

morceau, il devient un chef différent”, s’est exclamé l’un des trois résidents, et l’un de ses confrères<br />

a répliqué : “N’est-ce pas exactement ce que l’on est censé faire?”<br />

Richard Dyer<br />

Traduction : David Ylla-Somers<br />

CHARLES MUNCH DIRIGIERT BEETHOVEN<br />

In der Zeit von 1955 bis 1979 strahlte in <strong>Boston</strong> (USA) der nicht-kommerzielle Fernsehsender<br />

WGBH über 150 Livekonzerte des <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> aus. Vier Musikdirektoren —<br />

<strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong>, Erich Leinsdorf, William Steinberg und Seiji Ozawa — sowie zahlreiche namhafte<br />

Gastdirigenten kamen zur Geltung.<br />

Mehr als 100 dieser Programme sind uns in den Archiven des Senders und des Orchesters erhalten<br />

geblieben. Die technische Diversität der Aufzeichnungen und rechtliche Probleme haben es bisher<br />

jedoch dem interessierten Publikum, ja selbst der Musikforschung, unmöglich gemacht, auf diesen<br />

Fundus zuzugreifen. Mit der vorliegenden DVD-Reihe werden viele dieser Aufführungen zum<br />

erstenmal seit ihrer ursprünglichen Ausstrahlung wieder zugänglich.<br />

1955 führte <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong> das <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> in die Fernsehwelt ein. Er war eine<br />

charismatische Persönlichkeit, wie für das neue Medium geschaffen, mit einer stämmigen Statur,<br />

weißem Schopf und einem verschmitzten Lächeln, so dass es nicht verwundert, dass ihm einige<br />

nerzbehangene Matronen aus dem <strong>Boston</strong>er Nobelviertel Back Bay den Spitznamen “le beau<br />

<strong>Charles</strong>” gaben.<br />

<strong>Munch</strong> hatte bei zwei der bedeutendsten Lehrer seiner Zeit, Lucien Capet in Frankreich und Carl<br />

Flesch in Berlin, Violine studiert und als Konzertmeister in Köln und Leipzig unter der Leitung von<br />

Dirigenten wie Wilhelm Furtwängler und Bruno Walter gewirkt, als er sich 1932 selber der<br />

Dirigentenlaufbahn zuwandte. Die Ernennung zum Musikdirektor des <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

1949 führte den nunmehr 58-jährigen auf den Gipfel seiner Karriere.<br />

Während seiner 13 Jahre in <strong>Boston</strong> widmete sich <strong>Munch</strong> einem breitgefächerten Repertoire vom<br />

Barock (Bach lag ihm besonders am Herzen) bis zur Moderne. Er leitete dort 68 Welturaufführungen<br />

oder US-Premieren, zuletzt Leonard Bernsteins Sinfonie Nr. 3, Kaddish, in Anwesenheit des<br />

Komponisten. Seinen Namen machte er sich jedoch mit Interpretationen französischer Musik von<br />

Berlioz, Debussy, Saint-Saëns und Ravel sowie lebender Komponisten wie Honegger, Roussel,<br />

Poulenc und Dutilleux. Seine Tätigkeit als Studiodirigent erstreckte sich über mehr als drei<br />

Jahrzehnte (1935–68), und einige der Aufnahmen aus dem französischen Repertoire, die er mit dem<br />

<strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> vorgelegt hat, haben sich über die letzten 50 Jahre hinweg gut verkauft.<br />

Sie besitzen Stellenwert als Referenzstandard.<br />

Nach Entwicklung der Langspielplatte betrachteten viele Dirigenten eine Gesamteinspielung der neun<br />

Beethoven–Sinfonien als eine Art Ehrenzeichen (Herbert von Karajan und Bernard Haitink gehörten<br />

beispielsweise zu denjenigen, die das Projekt immer wieder aufgriffen). <strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong> — obwohl<br />

einer der berühmtesten Dirigenten der LP-Ära — nahm mit dem <strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> aber<br />

nur sechs Beethoven-Sinfonien auf (Nr. 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 und 9), und aus der Zeit von 1947 bis 1967<br />

sind andere Orchester unter seiner Leitung mit vier Sinfonien (Nr. 3, 4, 6 und 8) dokumentiert. Eine<br />

8<br />

9

Einspielung der Zweiten, die er mit dem BSO nur ein einziges Mal aufführte, existiert offenbar nicht.<br />

Er bot dem Publikum in <strong>Boston</strong> nie ein Gesamtprogramm der Beethoven–Sinfonien, und eine<br />

komplette Zusammenstellung ist uns auch im Nachhinein nicht möglich.<br />

Verschiedene Ouvertüren setzte er recht regelmäßig auf das Programm, doch die hier vorliegende<br />

Suite aus Beethovens Ballett Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus hat Seltenheitswert insofern, als er sie<br />

mit dem BSO in nur einer Spielzeit darbot — nicht mehr als vier Mal.<br />

Für Beethoven selbst war das Ballett zunächst ein Erfolg: In der Premierensaison kam es zu<br />

16 Aufführungen. Doch der Choreograph und sein Werk gerieten aus der Mode, und die Musik fiel<br />

weitgehend in Vergessenheit. Lediglich die Ouvertüre konnte sich in den Konzertsälen auf Dauer<br />

durchsetzen. <strong>Munch</strong> stellte dem Stück zwei der insgesamt sechzehn seltener gehörten Sätze zur<br />

Seite. In dem eleganten Andante quasi allegretto konnten einige seiner gefeierten BSO-Solisten<br />

glänzen: Doriot Anthony Dwyer (Flöte), Samuel Mayes (Cello), Sherman Walt (Fagott) und Bernard<br />

Zighera (Harfe, in einer der wenigen Beethoven-Kompositionen für dieses Instrument). <strong>Munch</strong><br />

förderte seine Solisten, ohne je störend auf sie einzuwirken.<br />

Zwei weitere Werke sind von dem jubilierenden Finalthema Beethovens inspiriert: ein Satz von<br />

Klaviervariationen mit abschließender Fuge (op. 35) und natürlich das Finale der “Eroica”. <strong>Munch</strong><br />

scheinen die leicht gewagten Opera buffa-Abwandlungen der aus anderen Fassungen besser<br />

bekannten Musik gefallen zu haben.<br />

Freude, die er sichtlich an der Musik und am Dirigieren hat. Indem er die Musik beherrscht, setzt<br />

er sie frei.<br />

Ralph Gomberg ist in dem berühmten kleinen Oboensolo eloquent, und mehrere Nahaufnahmen<br />

lenken den Blick auf das dritte Pult der ersten Violinen. Freunde des BSO dürften den ernsten,<br />

dunkelhaarigen Mann auf der Außenseite erkennen — es ist der 27-jährige Joseph Silverstein,<br />

der binnen drei Jahren die Nachfolge von Richard Burgin als Konzertmeister und stellvertretender<br />

Dirigent antreten sollte — eine Verantwortung, die er dann über 22 Spielzeiten hinweg mit großer<br />

Ehre erfüllte.<br />

Jedes Jahr im Sommer fördert das BSO eine achtwöchige Akademie für die höhere musikalische<br />

Fortbildung, mit früheren Teilnehmern wie Leonard Bernstein, Christoph von Dohnányi, Claudio<br />

Abbado, Seiji Ozawa und Lorin Maazel. Drei Mitglieder des Dirigentenseminars 2010 sahen sich<br />

eines Nachmittags einige von <strong>Munch</strong> geleitete Konzertaufnahmen an. “In jedem Werk ist er ein<br />

anderer Dirigent”, bemerkte einer der Drei, woraufhin ein anderer erwiderte: “Ist das nicht so,<br />

wie es sein sollte?”<br />

Richard Dyer<br />

Übersetzung: Andreas Klatt<br />

Also available from ICA Classics:<br />

Der Vierten gibt er eine schmucke, feurige Gestalt, an der man Freude hat. Seine Überleitung von<br />

dem einleitenden Adagio des Kopfsatzes mit seinen bösen Vorahnungen zu dem anschließenden<br />

Allegro vivace ist blendend phantasievoll kontrolliert, und das Gebilde setzt zu seinem Höhenflug an,<br />

ohne ins Scheppern zu geraten. Das Scherzo ist kultiviert und aufregend zugleich, bevor uns das<br />

hinreißende Finale erfasst — Walt meistert die berühmt–berüchtigte Fagottpassage mit Elan.<br />

Mit der symbolträchtigen Fünften dirigierte <strong>Munch</strong> das BSO bei 34 Gelegenheiten, obwohl nur<br />

13 dieser Konzerte in <strong>Boston</strong> oder Tanglewood stattfanden: Er nahm die Sinfonie mit Vorliebe in<br />

seine Tourneeprogramme auf. Diese feurige Aufführung von 1959 aus dem Sanders Theatre der<br />

Universität Harvard klingt auch heute noch so aufregend, wie sie dem demonstrativen Publikum<br />

damals erschien. Sie ist ein Zeugnis überragender Virtuosität auf Podium und Plattform<br />

gleichermaßen. <strong>Munch</strong> dirigiert mit der Freiheit eines Solisten ersten Ranges, weil er weiß, dass<br />

das Orchester all seinen Forderungen nachkommen kann und wird. Flexible Tempi bei unbeirrbarem<br />

Rhythmus und treibender Kraft charakterisieren seinen Ansatz. In stilleren Momenten vermag er<br />

es, die Energie umzuleiten, anstatt sie zu schwächen, so dass eine außergewöhnliche Wucht und<br />

Dichte gewahrt bleiben. Wenn dann die Höhepunkte erreicht werden, sind sie packend nicht nur<br />

in sich, sondern auch, weil sie vorbereitet, nicht erahnt worden sind — das Ergebnis ist spontane<br />

Verbrennung. <strong>Munch</strong>s Engagement ist spürbar, und man kann ihn grollen hören, bevor er zum<br />

endgültigen Triumph ansetzt. Was uns als Zuschauern davon bleibt, ist die reine, ansteckende<br />

ICAD 5014<br />

Debussy: La Mer · Ibéria<br />

Ravel: Ma Mère l’Oye Suite<br />

<strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

<strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong><br />

ICAD 5015<br />

Wagner: <strong>Orchestra</strong>l excerpts<br />

from Die Meistersinger<br />

Franck: <strong>Symphony</strong> in D minor<br />

Fauré: Pelléas et Mélisande Suite<br />

<strong>Boston</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

<strong>Charles</strong> <strong>Munch</strong><br />

10<br />

11