Governor Benjamin Pierce - New Hampshire Historical Society

Governor Benjamin Pierce - New Hampshire Historical Society

Governor Benjamin Pierce - New Hampshire Historical Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

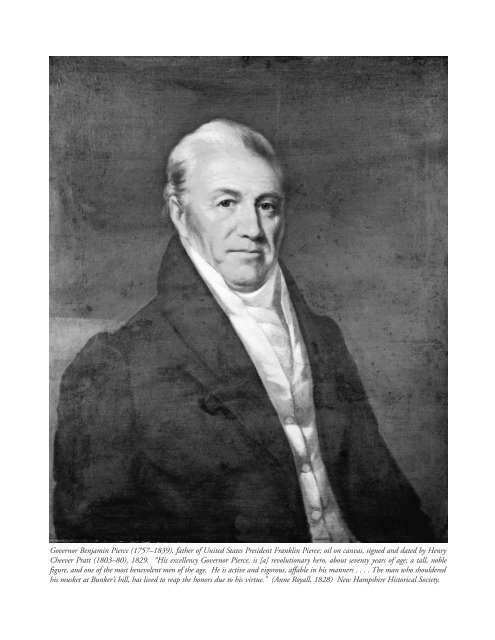

<strong>Governor</strong> <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> (1757–1839), father of United States President Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>; oil on canvas, signed and dated by Henry<br />

Cheever Pratt (1803–80), 1829. “His excellency <strong>Governor</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, is [a] revolutionary hero, about seventy years of age; a tall, noble<br />

figure, and one of the most benevolent men of the age. He is active and vigorous, affable in his manners . . . . The man who shouldered<br />

his musket at Bunker’s hill, has lived to reap the honors due to his virtue.” (Anne Royall, 1828) <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.

7<br />

Inheriting the Revolution: <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World, Ideals, and Legacy<br />

Wesley G. Balla<br />

Contemporary Americans often view their<br />

history as fixed and immutable, an endless<br />

parade of people and events marching<br />

forward across time and space. Nineteenth-century<br />

letters, diaries, account books, and newspapers<br />

surviving in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> indicate that, in reality,<br />

lives then as now were in constant flux, built on a<br />

myriad of relationships and influences. Ties of family<br />

and business, religious beliefs and politics, together<br />

with memories of events and people, great and ordinary,<br />

have helped shape identities and fortunes. Chief<br />

among the influences on Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>’s personality<br />

and values were those of his father <strong>Benjamin</strong>, one<br />

of the leaders of the revolutionary generation in<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>.<br />

“The Glorious Principles of Independence”<br />

On a cold Christmas Day in 1824, General<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> hosted twenty-one veterans of the<br />

Revolutionary War at a dinner in his commodious<br />

tavern situated on the turnpike in the Lower Village<br />

of Hillsborough, <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>. Inspired by the<br />

Marquis de Lafayette’s visits to the United States in<br />

1824 and 1825 in celebration of the fiftieth<br />

anniversary of the nation’s founding, General <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

invited his surviving comrades in the town of<br />

Hillsborough to join him in honoring the heroes,<br />

events, and ideals of the American Revolution.<br />

Although a few Hillsborough veterans were in their<br />

eighties, most were in their sixties and seventies when<br />

they gathered at the <strong>Pierce</strong> home that day. At 11:00<br />

WESLEY G. BALLA is director of collections and<br />

exhibitions at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> and<br />

curator of “Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>: Defining Democracy in<br />

America,” on view at the <strong>Society</strong>’s Tuck Library from<br />

July 2004 to May 2005.<br />

in the morning, after the group had assembled,<br />

General <strong>Pierce</strong> made a short, emotional address<br />

welcoming his guests and encouraging them to<br />

recount the feats and perils they had faced in fighting<br />

the British. Eighty-nine-year-old Ammi Andrews<br />

and eighty-three-year-old John McColley—the two<br />

oldest veterans present—were unanimously elected<br />

president and vice president of the day as a mark of<br />

respect and veneration. The meeting was called to<br />

order and, after Congregational minister Rev. John<br />

Lawton offered a prayer of blessing, the assembled<br />

veterans related a variety of anecdotes about their<br />

revolutionary service. 1<br />

At 1:30, the group moved to the dining room<br />

where they consumed a hearty dinner punctuated by<br />

a succession of thirteen toasts, one for each of the<br />

original states of the Union. The first nine toasts<br />

honored the memory of George Washington and the<br />

heroes, as well as the many hard-won battles, of the<br />

Revolution. In contrast, the final four toasts looked<br />

to the future rather than the past, calling for the<br />

country’s leaders to be patriotic and honest in the<br />

face of adversity, for “National Alliances” never “to<br />

destroy the liberty and happiness of man,” and for<br />

the union of the states to be preserved in the face<br />

of “strong policy or foolish sectional feelings.” As<br />

customary at public gatherings, the spirited exchange<br />

continued with twelve more voluntary toasts. Four of<br />

these praised the United States military forces and<br />

their success against the British during the recent<br />

War of 1812. The group joined in honoring the<br />

Marquis de Lafayette and the Greeks struggling for<br />

liberty in Europe. Near the end of the proceedings,<br />

the youngest veteran, fifty-nine-year-old Nathaniel<br />

Johnston rose to toast his revolutionary comrades<br />

across the nation. Johnston proclaimed them, “first

8 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

in dignity, first among heroes in political rights.”<br />

Mindful of the importance of their democratic<br />

experiment, he concluded with the solemn<br />

injunction, “may they continue firm examples of the<br />

patriotic virtues, and our children maintain the<br />

glorious principles of independence.” 2<br />

The festivities concluded with General <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

addressing his old comrades once more. Wishing his<br />

guests well, <strong>Pierce</strong> then parted the mists of time with<br />

stirring memories of the war, which he described<br />

eloquently as “the cause so expensive in its influence<br />

and so glorious in its termination.” He went on to<br />

praise God for preserving all present—though with<br />

“minds and bodies infirm”—to see the happiness and<br />

prosperity that had emerged within fifty years from<br />

that struggle. General <strong>Pierce</strong> offered thanks for those<br />

present to their Creator for enabling them “to see our<br />

beloved country so rapidly increase in population<br />

[and] to see the progress of the arts and sciences of<br />

agriculture of commerce and manufactures.” Sadly, it<br />

would not be long before these good and faithful soldiers<br />

would join General Washington and their war<br />

comrades in death. 3<br />

The meeting of the revolutionary heroes that day<br />

at <strong>Pierce</strong>’s tavern was more than an exercise in<br />

honoring the dead. In a true embodiment of<br />

patriotism, the veterans focused their listeners’<br />

attention on both the present and the future as they<br />

sought to keep the spirit of the Revolution alive and<br />

to apply its principles in a rapidly changing world. 4<br />

Laying Down the Plough<br />

Born on December 25, 1757, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> was<br />

the seventh of ten children of <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> and<br />

Elizabeth Merrill of Chelmsford, Massachusetts.<br />

Young <strong>Benjamin</strong>’s father, a farmer, died when<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> was age six, leaving him in the care of his<br />

uncle Robert <strong>Pierce</strong>, also a Chelmsford farmer.<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong>’s father left a modest estate of land,<br />

buildings, clothes, furniture, a few farm animals, and<br />

notes valued at 153 pounds, 3 shillings, and 4 pence.<br />

The estate had approximately 700 pounds in debts.<br />

In need of a provider, <strong>Benjamin</strong>’s mother remarried.<br />

On January 3, 1769, she became the wife of another<br />

Chelmsford farmer, Oliver Bowers. On December<br />

18, 1770, twelve-year-old <strong>Benjamin</strong> chose his cousin<br />

William <strong>Pierce</strong> as his legal guardian until he reached<br />

twenty-one. William, whose occupation was given as<br />

“Gentleman,” was the son of <strong>Benjamin</strong>’s uncle<br />

Robert. Under his relatives’ care, <strong>Benjamin</strong> grew up<br />

among modest farmers on the northern fringes of<br />

<strong>New</strong> England settlement. When not working in the<br />

fields and practicing farming, he attended school<br />

approximately three weeks each year, learning to<br />

read, write, and cypher. 5<br />

On April 18, 1775, while plowing a field in<br />

Chelmsford, the seventeen-year-old <strong>Pierce</strong> heard that<br />

British troops had fired upon Americans in nearby<br />

Lexington, killing eight men. Displaying the<br />

decisiveness that was to become the hallmark of his<br />

later political career, <strong>Pierce</strong>, according to his own<br />

memoir, “stepped between the cattle, dropped the<br />

chains from the plough, and without ceremony<br />

shouldered my uncle’s fowling piece, swung the<br />

bullet-pouch and powder-horn and hastened to the<br />

place where the first blood had been spilled.” Once<br />

there, however, “finding the enemy had retired, I<br />

pursued my way towards Boston, but was not able to<br />

overtake them till they had effected their retreat to<br />

the garrison.” 6<br />

On June 17, <strong>Pierce</strong> took part in the Battle of<br />

Bunker Hill (also known as Breeds’ Hill). He later<br />

recalled proudly that he was “at Dorchester Heights,<br />

when the British evacuated Boston, and entered<br />

the city with the American army.” <strong>Pierce</strong>’s military<br />

involvement extended from 1775 to 1784. He was<br />

involved mostly with the campaigns in <strong>New</strong> York,<br />

serving at Ticonderoga, Fort Stanwix, and Bemis<br />

Heights. He was among those “quartered for the<br />

winter with the continental army” at Valley Forge<br />

from 1777 to 1778. Later stationed at White Plains<br />

and West Point, he served “in the regiments that<br />

went with Gen Washington to take possession of<br />

<strong>New</strong> York” at the close of the war. 7

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 9<br />

The Revolution, which brought profound change<br />

to every corner of American society, had created a<br />

vocal and assertive citizenry. Republican emphasis on<br />

the virtues of talent and merit unleashed men’s desire<br />

for social and economic advancement. Yet, when<br />

Lieutenant <strong>Pierce</strong> and other soldiers returned to their<br />

rural homes following years of service in<br />

the Continental Army, they faced age-old challenges<br />

of earning a livelihood through farming. Like<br />

generations before him, <strong>Pierce</strong> turned to the frontier<br />

where land was cheap yet provided a foundation for<br />

building family and community. 8<br />

In 1785, <strong>Pierce</strong> found employment “as an agent to<br />

explore the lands” in present-day Stoddard, <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong>, then owned by the heirs of Col.<br />

Sampson Stoddard, Esq. (1709–77), a wealthy<br />

Chelmsford merchant and politician. Through<br />

royal grants and purchases, the Stoddard family<br />

had title to eighty-thousand acres in Acworth,<br />

Dublin, Fitzwilliam, Goffstown, Jaffrey, Rindge, and<br />

Stoddard, which they hoped to develop or sell to<br />

land-hungry farmers pressing northward. 9<br />

In the spring of 1786, <strong>Pierce</strong> joined the steady<br />

stream of <strong>New</strong> England farmers moving northward<br />

“A Correct View of the Late Battle at Charlestown June 17 th 1775,” engraved by Robert Aitken (1734–1802) of Philadelphia and published in<br />

the Pennsylvania Magazine, September 1775. When news of the Battle of Lexington reached young <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, he laid down his plough,<br />

headed for Boston, and joined the militia. He later recorded: “June 17 th I was at the battle on Breed’s Hill.” Courtesy of the American<br />

Antiquarian <strong>Society</strong>.

10 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.<br />

While exploring the Stoddard lands in the wilds<br />

of Hillsborough County, he had discovered an<br />

undeveloped, fifty-acre tract on the northwest branch<br />

of the Contoocook River and, before returning to<br />

Chelmsford, he purchased it. That spring, he hauled<br />

a supply of provisions to Hillsborough and, together<br />

with a friend with whom he had served in the<br />

Continental Army, he moved into the log hut built<br />

by the land’s previous owner. The two men probably<br />

spent the rest of the year cutting and clearing away<br />

trees and brush and beginning to plant crops. 10<br />

Building Family and Community<br />

Family was at the center of society and life in<br />

post-revolutionary <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>. Often, families<br />

moved, either together or consecutively, from<br />

established northern Massachusetts towns to new<br />

communities in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>. They typically<br />

maintained strong connections with their former<br />

town, on which they patterned their settlement and<br />

its institutions.<br />

Within a year of settling in Hillsborough,<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> had started a family. <strong>Pierce</strong> married<br />

Elizabeth, the daughter of Isaac and Lucy (Perkins)<br />

Andrews. Elizabeth’s father, Isaac, who had settled on<br />

a farm on Hillsborough’s Bible Hill in 1765, was a<br />

town selectman, town clerk, and one of the founders<br />

of the Congregational Church. On August 13, 1788,<br />

however, Elizabeth died, four days after giving birth<br />

to the couple’s only child, a daughter also named<br />

Elizabeth. Faced with raising an infant and keeping a<br />

household, <strong>Benjamin</strong> soon remarried. On February<br />

1, 1790, Anna Kendrick, the youngest daughter of<br />

farmer <strong>Benjamin</strong> and Sarah (Harris) Kendrick of<br />

Amherst, became his wife. <strong>Benjamin</strong> Kendrick<br />

(1723–1812) had served as town moderator and<br />

leader of the Congregational Church, since<br />

settling in Amherst in 1770. 11<br />

Marriage into the Kendrick family extended<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>’s ties to Amherst, the shire town of<br />

Hillsborough County. Links to his hometown in<br />

Massachusetts also remained strong. His younger<br />

brother Merrill (1764–1816) followed him to <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong>, where he, too, settled in Hillsborough.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>’s extended family eventually stretched from<br />

Hillsborough across northern <strong>New</strong> England. The<br />

marriage of each member of his family further broadened<br />

the network of his relatives and acquaintances. 12<br />

With other settlers, <strong>Pierce</strong> and his family created<br />

community organizations to serve their social,<br />

economic, and political needs, forging a civic life<br />

in Hillsborough similar to what they had known<br />

previously. A greater decentralization of cultural<br />

authority, new ideas about equality, and a new rhetoric<br />

of liberty—based on the ideals of the American<br />

Revolution—emerged, however, as important characteristics<br />

in the northern <strong>New</strong> England settlement.<br />

Anna Kendrick <strong>Pierce</strong> (1768–1838), oil on wood panel, attributed<br />

to Zedekiah Belknap (1781–1858), c. 1815. In the years following<br />

the war, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> returned to farming, settled in<br />

Hillsborough, and established a family. His second wife, Franklin’s<br />

mother, was a member of the Kendrick family of Amherst, the<br />

Hillsborough County seat. From the collections of The Henry Ford.

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 11<br />

The creation of a new nation was nurturing cultural<br />

change in <strong>New</strong> England, eroding the power of the<br />

church and its leaders, for example. Generations of<br />

<strong>New</strong> Englanders had been born, spent their lives,<br />

and died in a society ruled by the Congregational<br />

Church. Democratic beliefs and revolutionary<br />

spirit, however, permeated northern <strong>New</strong> England<br />

society, which had been created largely by farmers<br />

and artisans. Fanned by evangelical fervor, plainspoken<br />

Methodists and Baptists found a home on the fluid<br />

frontier of northern <strong>New</strong> England. Although the<br />

Congregational Church was not formally disestablished<br />

in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> until the passage of the<br />

Toleration Act by the state legislature in 1819, a<br />

gradual movement toward religious liberty had been<br />

underway since the 1790s. 13<br />

Unpretentious and genuine expressions of faith<br />

found support among the <strong>Pierce</strong>s and other members<br />

of their rural community. In 1813, when the First<br />

Baptist <strong>Society</strong> was organized in Hillsborough, the<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>s were among its early members. Services were<br />

held in private homes, schoolhouses, and barns<br />

until the congregation grew sufficiently to erect a<br />

meetinghouse. In 1823, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> gave land<br />

near his home to the Baptist <strong>Society</strong> for a meeting<br />

house and burying ground. He contributed to the<br />

other Christian denominations in his town as well. 14<br />

In building new communities, townsmen not only<br />

borrowed from their pasts but also looked to the<br />

present and to the future. Some institutions they<br />

founded were intended to ensure that residents could<br />

participate fully in the new republic. An informed<br />

citizenry needed access to knowledge and education.<br />

In 1797, with this in mind, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> joined<br />

Jonathan Barnes, James Eaton, and William Taggart<br />

in petitioning the state legislature to form a “social<br />

Library” in Hillsborough. On December 16, 1797,<br />

the proprietors of the newly incorporated library<br />

were authorized to “receive subscriptions grants and<br />

donations of personal Estate,” so that they could<br />

begin to purchase books and establish a library. For<br />

more than twenty years, the library provided a broad<br />

range of reading matter not otherwise available to the<br />

farming families of Hillsborough. On the library<br />

shelves, community members found an eclectic<br />

mixture of books, tracts, and magazines published in<br />

Europe and America. 15<br />

The library collection was selected with the goal<br />

not only of the dissemination of knowledge, but also<br />

the cultivation of virtue, reflecting the general<br />

recognition at this time of the importance of nurturing<br />

a virtuous, patriotic, and informed citizenry. The<br />

library’s offerings included Doddridge’s Sermons,<br />

educating readers to Christian moral and religious<br />

values; Morse’s Geography, acquainting farmers with<br />

the size and character of the developing United<br />

States; <strong>Benjamin</strong> Franklin’s Works inspiring young<br />

readers with the importance of hard work and<br />

independent thought; and the fictional Arabian<br />

Nights Entertainment, introducing townspeople to<br />

the mysteries of faraway lands. A Jeffersonian, <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

believed that education was vital to developing a<br />

strong national economy based on farming and<br />

commerce, all key ingredients in the success of a free<br />

republic. A member of the Hillsborough County<br />

Agricultural <strong>Society</strong>, the goal of which was to promote<br />

scientific farming and increased productivity, <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

enthusiastically participated in the organization’s<br />

annual cattle show and fair. 16<br />

A Public House and Public Life<br />

In 1804, having lived in Hillsborough for nearly<br />

two decades, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> moved his family<br />

into an elegant, two-story, wood-framed house,<br />

standing on a gentle rise of land along the<br />

Second <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Turnpike in what would<br />

become known as Hillsborough Lower Village.<br />

Chartered by the state in 1799, the Second <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong> Turnpike connected Claremont, on the<br />

Connecticut River, via the Contoocook River<br />

valley with Amherst, where it intersected the<br />

Middlesex Turnpike leading to Boston. People,<br />

produce, and goods moved along this and other<br />

turnpikes to markets in the seaport cities of<br />

Portsmouth and Boston while providing new<br />

communication networks for settlers. 17

12 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> homestead and tavern, Hillsborough Lower Village, built 1804; daguerreotype by James A. Cutting (1813–67), of<br />

Boston, which served as the basis for a popular print of the president’s childhood home, lithographed in 1852 by Nathaniel Currier.<br />

People from all walks of life passed through the <strong>Pierce</strong> tavern, an important center in the social, economic, and political life of the<br />

community. Courtesy of the <strong>Pierce</strong> Brigade.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> supplemented his livelihood by feeding<br />

and refreshing travelers on the turnpike as well as<br />

his neighbors who had formed a small settlement<br />

of twenty houses in the vicinity of the tavern.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>’s was one of a dozen public houses across<br />

Hillsborough strategically located at crossroads.<br />

Town selectmen granted taverns licenses to sell<br />

drink. As early as 1795, <strong>Pierce</strong> had obtained such<br />

a license. 18<br />

Across rural America in the early nineteenth<br />

century, taverns like <strong>Pierce</strong>’s were a vital part of<br />

community life. They became neighborhood<br />

centers for informal socializing, for the exchange<br />

of information and ideas, for community meetings,<br />

and for political activity. Taverns served as community<br />

forums, encouraging participation in local and<br />

state politics. With the decline of a hierarchical society<br />

in late-eighteenth-century America, it became<br />

necessary for candidates to appeal directly to voters,<br />

and the tavern owner proved uniquely qualified to<br />

help candidates do this. The consumption of drink<br />

often facilitated communication between elected<br />

officials and their constituents, as candidates treated<br />

tavern patrons to food and drink at election time. 19<br />

In addition to the village regulars, people<br />

passing through Hillsborough along the turnpike<br />

stopped for refreshment at General <strong>Pierce</strong>’s tavern.<br />

One Dartmouth College student later recalled<br />

spending a pleasant evening “agreeably in conversation<br />

with the General’s daughters” before catching a<br />

stage to his home in Massachusetts. Some of the tavern<br />

guests were drawn as much by the innkeeper’s

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 13<br />

celebrity as a revolutionary soldier and political<br />

leader as by the hospitality he offered. As <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

became increasingly prominent in state politics, the<br />

leaders of the Democratic Party frequently came to<br />

the hostelry to consult with the old patriot on issues<br />

of the day. Even political opponents, such as the<br />

great orator Daniel Webster, stopped at the tavern to<br />

seek General <strong>Pierce</strong>’s counsel and a drink. 20<br />

A tavern keeper’s involvement in extending credit<br />

and disseminating news made him influential in<br />

local affairs. Taverns played a vital role in facilitating<br />

informal exchange of information within rural<br />

communities throughout <strong>New</strong> England. Even the<br />

most illiterate or poor could hear and discuss the<br />

news of the day at the tavern. At the same time,<br />

taverns became important in the distribution of<br />

written communications as regular mail service<br />

extended inland. 21<br />

On April 1, 1803, in response to a petition from<br />

town residents, the United States government<br />

created a post office at Lower Village and, on July 8,<br />

1818, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> received a federal patronage<br />

appointment as postmaster of Hillsborough. Farmers<br />

and artisans from across the town traveled to the tavern<br />

to collect or mail letters as well as to learn the latest<br />

news and exchange ideas. Anna <strong>Pierce</strong> and her<br />

children no doubt assisted the busy tavern<br />

keeper in distributing letters and collecting postage.<br />

In the fall of 1824, the <strong>Pierce</strong>s’ son Franklin, who<br />

had just graduated from Bowdoin College and was<br />

studying law under local attorney John Bingham,<br />

earned a small but steady income assisting his father<br />

in his postmaster duties. 22<br />

All Politics is Local<br />

While the tavern clearly helped his political career,<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s political education probably<br />

began much earlier in his life, in the Chelmsford<br />

meetinghouse where the town’s men gathered on<br />

the first Tuesday of March each year to elect<br />

officials and decide the community’s business.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>’s revolutionary experiences also had a strong<br />

impact on his commitment to public service. As<br />

witness to the struggle on battlefields against the<br />

British and inspired ever afterwards by the ideals of<br />

freedom, <strong>Pierce</strong> saw himself as a patriot defending<br />

the hard-won liberties of farmers from the greed of<br />

aristocrats determined to subvert the Republic.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> arrived in Hillsborough during a turbulent<br />

time in the young lives of the state and the nation. As<br />

an ambitious man who aspired to greater things for<br />

himself, his family, and his country, <strong>Pierce</strong> became<br />

involved in the struggles of post-revolutionary politics.<br />

Fueled by disagreement over issues of religious<br />

liberty, of threats to trade by the English and French,<br />

and of the proper use of state funds, the adherents of<br />

two political factions coalesced into parties by the<br />

late 1790s, becoming known as Federalists and<br />

Jeffersonian Republicans. 23<br />

In the meantime, the people of Hillsborough did<br />

not hesitate to call on the talented newcomer from<br />

Chelmsford to serve in town office. Like his fatherin-law<br />

before him and like two sons later on, <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

served many years as town moderator. Between 1792<br />

and 1813, on the second Tuesday of March and the<br />

first Tuesday in November each year, he presided<br />

eighteen times over the men gathered at the meeting<br />

house to conduct town business and elect officials. 24<br />

A popular community leader, <strong>Pierce</strong> was elected<br />

to the state legislature in 1789 by the towns of<br />

Henniker and Hillsborough. He continued to<br />

represent the latter in Concord for thirteen years.<br />

The times were turbulent, and citizens of the young<br />

republic—plagued by debt, economic depression,<br />

and political turmoil—turned to their representatives<br />

for help. In 1791, <strong>Pierce</strong> served as a member of the<br />

state constitutional convention. In 1803, he was<br />

elected councilor for Hillsborough County, serving<br />

in that office for five years. 25<br />

In 1809, <strong>Governor</strong> John Langdon appointed <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

sheriff of Hillsborough County. As sheriff, he became<br />

an officer of the court, traveling from Amherst across<br />

Hillsborough County, serving writs, securing<br />

prisoners, and maintaining order. During the first<br />

decade of the nineteenth century, <strong>Pierce</strong> became a<br />

strong proponent of Jeffersonian Republicanism. He

14 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

was representative of his rural, inland constituency in<br />

his outspoken opposition to the Federalists and his<br />

promotion of war with Great Britain. <strong>Pierce</strong> held the<br />

office of sheriff until 1813 when he was removed for<br />

refusal to carry out an order of the Federalist<br />

dominated Supreme Judicial Court. 26<br />

Commenting on this episode, <strong>Pierce</strong> wrote: “in<br />

1813, (I) was removed by an address from both<br />

Houses of the Legislature, to make room for Israel<br />

Kelly, whose politicks were better suited to the times:<br />

—it was the reign (of ) Terror. John T. Gilman was<br />

<strong>Governor</strong> of the State at the time. During this<br />

period, no effort was spared by the Federalists to ruin<br />

every prominent Democrat that dared oppose<br />

them.” According to <strong>Pierce</strong>, Federalist judges used<br />

elaborate means, even changing laws, in order to ruin<br />

himself and other Republicans. 27<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> did not remain out of office long. In<br />

response to alleged Federalist manipulation, enraged<br />

Hillsborough County voters re-elected <strong>Pierce</strong> to a<br />

seat on the General Council in 1814, and returned<br />

him annually for the next five years. When the<br />

Republicans gained control of the governorship<br />

again in 1818, William Plumer reappointed <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

sheriff of Hillsborough County. A first-hand witness<br />

to the cruelty of state laws upholding imprisonment<br />

for debt and religious intolerance, <strong>Pierce</strong> became a<br />

strong advocate of economic and religious freedom<br />

for all people. He secured his position as a leader of<br />

the Republicans in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, remaining as<br />

sheriff until 1827. 28<br />

The War of 1812 and the celebrations surrounding<br />

the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the United<br />

States of America fanned the flames of nationalism.<br />

In 1826, the leaders of the emerging Democratic<br />

Party of Andrew Jackson selected as their candidate<br />

for governor <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “the last hero of the<br />

Revolution,” who had strong support among the<br />

voters of southwestern <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>’s farming<br />

communities. <strong>Pierce</strong> lost the election to Dr. David L.<br />

Morrill (1772–1849) of Goffstown, an “Adams”<br />

Republican who won 17,679 out of 29,966 votes<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> State House,<br />

Concord, drawn and engraved<br />

by Abel Bowen (1790–1850)<br />

of Portsmouth and Boston;<br />

published in A Gazetteer of<br />

the State of <strong>New</strong>-<strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

by John Farmer and Jacob B.<br />

Moore, 1823. <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s<br />

long career of political service<br />

culminated in 1827 in his election<br />

as the first Jacksonian<br />

Democratic governor of the state.

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 15<br />

cast, with support from the Federalists. The Democrats<br />

led by Isaac Hill (1788–1851) went to work, laying<br />

the groundwork for the 1827 election. The<br />

Democratic members of the state legislature<br />

nominated <strong>Pierce</strong> as their candidate for governor at<br />

the convention held in Concord on June 20, 1826.<br />

The Adams followers temporarily reunited with the<br />

Jacksonians to support <strong>Pierce</strong> in the March 1827<br />

election. <strong>Pierce</strong> won 23,695 out of 27,411 votes cast<br />

in the election. 29<br />

As the first Jacksonian Democratic governor of<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong> came to Concord wearing a<br />

tricorn hat, the symbol of his revolutionary heritage.<br />

As Jacksonian Democrats and Adams Republicans<br />

in the state legislature struggled for control of<br />

government, <strong>Pierce</strong> invoked the memory of the<br />

founding fathers in his June 1827 message to the<br />

legislature, calling for <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> residents to<br />

preserve the “social virtues” of justice, moderation,<br />

temperance, industry, and frugality necessary to<br />

preserving liberty and good government. He urged<br />

representatives to improve public education through<br />

the uniform distribution of state funds to local<br />

public schools, to support the state militia over a<br />

large standing army, and to promote economic<br />

development. 30<br />

In 1828, the “Jackson” Democrat <strong>Pierce</strong> narrowly<br />

failed to win re-election, receiving only 18,672<br />

compared to 21,149 votes cast for National<br />

Republican John Bell (1765–1836) of Chester. In<br />

this election, Adams Republicans ran Bell as a<br />

prelude to the fall campaign for the presidency<br />

between Jackson and Adams. Although <strong>Pierce</strong> lost<br />

the election, rural farming communities in central<br />

and western <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> remained firm<br />

supporters of the governor. He easily carried<br />

Hillsborough, with 227 votes in comparison to 90<br />

for his opponent. In the election of 1829, with<br />

Jackson now President, Democrats, led by Isaac Hill<br />

and Levi Woodbury (1789–1851), carried the state<br />

against National Republicans and Federalists.<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> was returned to the governorship<br />

with 22,615 to 19,583 votes for John Bell. 31<br />

As <strong>Governor</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> addressed the state legislature<br />

on June 6, 1829, he took particular pride in his son<br />

Franklin, who had been elected a representative from<br />

Hillsborough as a Democrat and was sitting in the<br />

audience. In a ringing statement of republican<br />

principles, the old general urged legislators to put<br />

aside personal ambition and cooperate to support<br />

legislation promoting commerce between the<br />

“seaboard and the interior,” to avoid extravagance<br />

and “return to republican simplicity,” to support<br />

common free schools as the foundation of an<br />

informed electorate, and to secure “full and<br />

impartial” administration of justice. 32<br />

The Citizen Soldier<br />

Friend and political supporter Isaac Hill recalled that<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> was a lifelong advocate for the militia.<br />

As Hill explained, “from principle, believing it to be the<br />

only sure arm of defence: he patronized and encouraged<br />

its continued organization and discipline throughout<br />

life.” Founding father George Washington created<br />

the ideal of the citizen soldier. For Americans, the<br />

ideal of military service as necessary to secure a free<br />

people and as espoused by Washington became<br />

the model of virtue in the young republic. In postrevolutionary<br />

America, periodic service in militia<br />

companies offered every white man between twentyone<br />

and forty-nine years of age the opportunity to<br />

demonstrate his patriotism and citizenship. 33<br />

While still working to clear his farm in the<br />

autumn of 1786, <strong>Pierce</strong> received an appointment<br />

as brigade major of the Hillsborough County militia<br />

from the new state’s president, John Sullivan. A seasoned<br />

soldier with nine years of military experience<br />

in the Massachusetts militia and the Continental<br />

Army, <strong>Pierce</strong> was skilled in handling, training, and<br />

disciplining men. A natural leader, he was an ideal<br />

candidate to help build the state’s military defenses.<br />

Equally important, militia service presented an<br />

opportunity for honor and advancement in a fluid<br />

society. In 1796, <strong>Pierce</strong> was appointed lieutenant<br />

colonel and commandant of the twenty-sixth<br />

regiment of the state militia. All able-bodied men

16 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

“The Militia Muster,” watercolor on paper, by David Claypoole Johnston (1799–1865), 1828. “Gen. P[ierce] was attached to the militia<br />

from principle, believing it to be the only sure arm of defence. He was of those who distrust standing armies as the principal reliance, believing<br />

they might be used here as they have been in other countries as instruments in the hands of arbitrary power to destroy the liberties of the<br />

people.” ( Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839) Courtesy of the American Antiquarian <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

from the towns of Antrim, Bennington, Deering,<br />

Francestown, Greenfield, Hancock, Henniker,<br />

Hillsborough, Lyndeborough, and Windsor served<br />

in the regiment’s two battalions. 34<br />

The fragility of the new nation was never far<br />

from the minds of the revolutionary generation. As<br />

early as 1793, America was caught in the middle of<br />

a succession of wars between France and Great<br />

Britain for dominance of Atlantic maritime trade.<br />

In 1798, the United States government, fearing war<br />

and invasion by France, attempted to raise an army<br />

of thirty thousand troops. On behalf of the<br />

government, Federalist Congressman William Gordon<br />

(1763–1802), an old acquaintance, offered <strong>Pierce</strong> an<br />

appointment as colonel in the United States Army.<br />

Invoking the spirit of the Revolution and true to his<br />

Jeffersonian political principles, <strong>Pierce</strong> recalled in<br />

his autobiography,<br />

I told him that . . . although arms was my<br />

profession, I could not consistently accept an<br />

appointment in an army . . . raised to subvert<br />

those principles for which I had fought in the<br />

Revolution; that I was forbidden by the duty I<br />

owed to myself my country and my God; and . . .<br />

although I was poor rather than (enslave) my<br />

countrymen . . . , I would return to a cave, and eat<br />

potatoes to the last day of my life. 35<br />

For <strong>Pierce</strong>, like many Americans who had fought<br />

during the American Revolution, the creation of a<br />

standing national army was associated with Old

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 17<br />

World corruption, particularly the royal oppression<br />

they had fought so hard to escape. Partisanship was<br />

beginning to characterize American politics. In the<br />

wake of the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in<br />

1798, making it treasonous to criticize the United<br />

States government, Republicans like <strong>Pierce</strong> feared<br />

that such an army would be used to put down dissent<br />

and eventually to destroy hard-won freedoms. On<br />

June 14, 1805, <strong>Governor</strong> Langdon appointed <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

brigadier general of the fourth brigade. In 1807, after<br />

twenty-one years of militia service, the general retired<br />

from his active duty as commander of the<br />

Hillsborough County regiments. 36<br />

Between 1807 and 1812, relations between the<br />

United States and Great Britain deteriorated as the<br />

British Navy blockaded ports and impressed<br />

American seamen. Americans settling on lands along<br />

the northern border of the United States also feared<br />

attack by Indians incited by British officials in<br />

Canada. On December 18, 1807, United States<br />

Senator Nahum Parker wrote to <strong>Pierce</strong> from<br />

Washington that, because of continuous predations<br />

on Americans by the British Navy—“so long the<br />

scourge of the sivilezed world”—the American<br />

people would be forced “to defend our rights by<br />

armies or surrender them.” 37<br />

Inheriting the “Glorious Principles”<br />

Though <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> opposed the undeclared,<br />

Federalist war with France in 1798, he endorsed the<br />

Jeffersonian Republican call to war with Great<br />

Britain in 1812. Two of <strong>Benjamin</strong>’s sons, <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

Kendrick and John Sullivan, joined the United States<br />

Army on the advice of their father. The entire<br />

family recognized the importance of military service<br />

at that time to preserving a strong republic. Each of<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> and Anna <strong>Pierce</strong>’s sons followed his<br />

precedent, embracing military service when<br />

necessary as an important part of their lives. Their<br />

three eldest sons, as well as several other close<br />

relatives, served in the military, but differed in their<br />

choice of whether to remain there during peacetime<br />

or to return to civilian life. 38<br />

John McNeil (1784–1850), <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s son-in-law; oil on canvas,<br />

attributed to Henry Willard (1802–55), c. 1825. The <strong>Pierce</strong>s<br />

believed that a strong military was necessary to the defense of<br />

American liberties. Franklin and his four brothers all served in the<br />

military at one time or another, and two brothers-in-law (both<br />

McNeils) boasted distinguished militia and War of 1812 careers.<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> Kendrick <strong>Pierce</strong>, the eldest son, was born<br />

in Hillsborough on August 29, 1790. Named for his<br />

maternal grandfather, the sturdy settler <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

Kendrick, he was educated at Phillips Academy,<br />

Exeter, and entered Dartmouth College in 1807, where<br />

he pursued a classical course of study for three years.<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> K. began the study of law in the office of<br />

Hillsborough attorney David Starrett. But, at the<br />

outbreak of the War of 1812, he obtained a commission<br />

as a lieutenant in the Third Regiment of Artillery,<br />

United States Army. After the war, he remained in<br />

the army, eventually retiring with the rank of colonel<br />

after a distinguished career defending American<br />

interests on the frontiers in Michigan and Florida. 39

18 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

John Sullivan <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Benjamin</strong>’s second son, was<br />

born in Hillsborough on November 5, 1796.<br />

Named for his father’s friend and political mentor<br />

Revolutionary General John Sullivan (1740–95), John<br />

S. was probably educated in local schools. Like his<br />

older brother, he received a commission as lieutenant<br />

in the United States Army in 1814. After the war, he<br />

remained in the army stationed at Fort Mackinac and<br />

died at Detroit, Michigan, on September 28, 1824. 40<br />

Charles Grandison <strong>Pierce</strong>, the third son, was<br />

born in Hillsborough in 1803 and named for the<br />

morally virtuous character of a popular English<br />

novel, Sir Charles Grandison, written by Samuel<br />

Richardson and published in 1753. Charles received<br />

an appointment to the United States military<br />

academy at West Point in 1818. He later moved to<br />

Utica, <strong>New</strong> York, where he died on June 25, 1828. 41<br />

The future United States president Franklin<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>, born in Hillsborough on November 23,<br />

1804, joined a military company that was drilling on<br />

the Bowdoin College campus, while he was studying<br />

there. He was elected their captain. On June 10,<br />

1831, shortly after Franklin’s election to the state<br />

legislature, he was appointed captain general’s aide in<br />

the militia. He was discharged June 6, 1834, after<br />

serving on the governor’s military staff, but later<br />

served with distinction as a brigadier general in the<br />

United States Army during the Mexican War. 42<br />

Henry Dearborn <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Benjamin</strong>’s youngest son,<br />

was born in Hillsborough on September 19, 1812.<br />

Named for his father’s friend and political confidant<br />

General Henry Dearborn (1751–1829), he was<br />

educated in local schools and eventually took over<br />

the family farm. Henry D. began service in the state<br />

militia with an appointment as a cavalry lieutenant<br />

in the twenty-sixth regiment on January 27, 1836.<br />

He was promoted to the rank of captain on<br />

December 8, 1838. In 1842, he was appointed<br />

aid-de-camp to <strong>Governor</strong> Henry Hubbard’s staff with<br />

the rank of colonel. A popular orator, Henry D.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> also represented Hillsborough in the legislature<br />

in 1841 and 1842. Town voters elected him moderator<br />

twenty-one times between 1845 and 1868. 43<br />

Finally, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s eldest daughter<br />

Elizabeth was the wife of War of 1812 hero John<br />

McNeil (1784–1850), whom she had married on<br />

December 25, 1811. Of Scots descent, McNeil was<br />

the son of one of her father’s revolutionary comrades.<br />

Both had served at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Not long<br />

afterward, Solomon McNeil (1782–1863), the elder<br />

brother of John McNeil, further cemented the family<br />

connections by marrying Nancy, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s<br />

second eldest daughter. John and Solomon McNeil<br />

each served valiantly against the British on the<br />

Niagara frontier during the War of 1812. John McNeil<br />

remained in the United States Army, rising to the rank<br />

of brigadier general before he resigned in 1830 to<br />

accept the post of Surveyor of the Port of Boston. 44<br />

A “Firm Example of Patriotic Virtues”<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s last official duty was casting a vote<br />

as an elector for Andrew Jackson in 1832. He remained<br />

a steadfast Democrat to the end of his life. Although<br />

retired from government, the aged veteran continued<br />

to work to preserve the memory and ideals of the<br />

Revolution to his dying day. In 1836, he was elected<br />

vice president of the Massachusetts Chapter of the<br />

<strong>Society</strong> of Cincinnati, a hereditary association of former<br />

Order of the <strong>Society</strong> of<br />

Cincinnati medal, owned<br />

by the <strong>Pierce</strong>s, c. 1850.<br />

Both <strong>Benjamin</strong> and<br />

Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong> belonged<br />

to the hereditary organization<br />

of revolutionary<br />

officers formed in 1783<br />

and named after Lucius<br />

Quinctius Cincinnatus.<br />

The Roman general, like<br />

the majority of revolutionary<br />

soldiers, had left his<br />

farm to bear arms and had<br />

returned to agriculture as<br />

soon as the enemy was<br />

defeated. <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

<strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 19<br />

officers of the Continental Army. On April 1, 1839,<br />

after suffering for two years from paralysis caused by<br />

a stroke, General <strong>Pierce</strong> died quietly in the bedroom<br />

of his house at Hillsborough Lower Village<br />

surrounded by members of his family, including his<br />

son Franklin, then a United States senator. At his<br />

funeral in Hillsborough on April 3, hundreds of<br />

men, women, and children from across <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong> assembled to pay last respects to their<br />

link with the American Revolution. Neither they nor<br />

the future president would ever forget the fervor with<br />

which this patriot had struggled first to help create a<br />

nation and then, ever afterwards, to uphold the ideals<br />

and principles of the republic and its constitution,<br />

keeping the spirit alive in the minds and lives of the<br />

next generation. 45<br />

Notes<br />

1. <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Patriot and State Gazette, Concord,<br />

January 10, 1825; Andrew Burstein, America’s<br />

Jubilee, July 4, 1826: A Generation Remembers the<br />

Revolution After Fifty Years of Independence (<strong>New</strong><br />

York: Vintage Books, 2001), 8–33; Walter<br />

<strong>New</strong>man Dooley, “Lafayette in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>”<br />

(master’s thesis, University of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>,<br />

1941); George David Browne, The History of<br />

Hillsborough, <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, 1735–1921, 2 vols.<br />

(Manchester, N. H.: John B. Clarke Co., 1921),<br />

1:218, 465; 2:367; Sarah J. Purcell, Sealed with<br />

Blood: War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary<br />

America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania<br />

Press, 2002),173.<br />

2. <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Patriot, January 10, 1825; John<br />

Resch, Suffering Soldiers: Revolutionary War<br />

Veterans, Moral Sentiment, and Political Culture in<br />

the Early Republic (Amherst: University of<br />

Massachusetts Press, 1999), 3–6, 10.<br />

3. Transcript of a speech delivered by General<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> at his home in Hillsborough, <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong>, December 25, 1824, folder 17,<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers, <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

<strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Library.<br />

4. Aware of his and the revolutionary generation’s<br />

place in history, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> wrote an<br />

autobiography for his family and future<br />

generations sometime during the late 1810s.<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography of <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>” (typed transcript), <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

<strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Library; Purcell, Sealed with<br />

Blood, 6–7, 93–94, 150, 173–209.<br />

5. Frederic Beech <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong> Genealogy, Being the<br />

Record of the Posterity of Thomas <strong>Pierce</strong>, An Early<br />

Inhabitant of Charlestown . . . (Worcester, Mass.:<br />

Charles Hamilton, 1882), 55–57; Farmer’s<br />

Monthly Visitor, Concord, N.H., vol. 1, no. 4<br />

(April 15, 1839):49–51.<br />

6. <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography.” Characteristics<br />

of self-reliance, courage, and patriotism—similar to<br />

those seen in Andrew Jackson, the popular leader of<br />

the Democratic Party—were ascribed to <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> by some of his contemporaries. John William<br />

Ward, Andrew Jackson: Symbol for an Age (<strong>New</strong><br />

York: Oxford University Press, 1975); Andrew<br />

Burstein, The Passions of Andrew Jackson (<strong>New</strong> York:<br />

Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), 21–25, 219–37. Isaac Hill,<br />

who supported and encouraged <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s<br />

candidacy for the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> governorship,<br />

knew both <strong>Pierce</strong> and Jackson and seems to have<br />

been the source of this comparison. Farmer’s<br />

Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Donald B. Cole,<br />

Jacksonian Democracy in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>,<br />

1800–1851 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard<br />

University Press, 1970), 28, 30, 59–60, 70–73.<br />

7. <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography”; Massachusetts<br />

Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, 17 vols.<br />

(Boston, Mass.: Secretary of the Commonwealth,<br />

1904), 12:364.<br />

8. Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American<br />

Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill, N. C.:<br />

Published for the Institute of Early American<br />

History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by<br />

the University of North Carolina Press, 1998),<br />

397–403, 476–83; David W. Conroy, In Public<br />

Houses: Drink and the Revolution of Authority in<br />

Colonial Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, N. C.:<br />

Published for the Institute of Early American<br />

History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by<br />

the University of North Carolina Press, 1995),<br />

310; Resch, Suffering Soldiers, 47–48.<br />

9. Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Wilson<br />

Waters, History of Chelmsford, Massachusetts<br />

(Lowell, Mass.: Courier-Citizen Co., 1917), 774;<br />

Isaiah Gould, History of Stoddard, Cheshire County,

20 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

N.H., From the time of its Incorporation in 1774 to<br />

1854, A period of Eighty Years (Marlboro, N.H.:<br />

Published for Maria A. Giffen by W. L. Metcalf,<br />

1897), 7–9; The History of the Town of Stoddard,<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, Formerly Known as Monadnock<br />

No. 7 and Limerick, From Its Incorporation on<br />

November 4, 1774 to 1974 (Published by the<br />

History Committee of the Stoddard <strong>Historical</strong><br />

<strong>Society</strong>, 1974), 3.<br />

10. David Jaffee, People of the Wachusett: Greater <strong>New</strong><br />

England in History and Memory, 1630–1860<br />

(Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999),<br />

163–64; <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography”;<br />

Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839.<br />

11. Jere R. Daniell, Colonial <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>: A History<br />

(Millwood, N.Y.: KTO Press, 1981), 166–70;<br />

Stephanie Coontz, The Social Origins of Private<br />

Life: A History of American Families, 1600–1900<br />

(<strong>New</strong> York: Verso Books, 1988), 116–60;<br />

Christopher Clark, The Roots of Rural Capitalism:<br />

Western Massachusetts, 1780–1860 (Ithaca, N.Y.:<br />

Cornell University Press, 1990); Jaffee, People of the<br />

Wachusett, 200–202; Browne, History of<br />

Hillsborough, 2:21; Daniel F. Secomb, History of the<br />

Town of Amherst, Hillsborough County, <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong> (1883; reprint, Somersworth: <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong> Publishing Co., 1972), 200, 204, 242,<br />

256, 259, 365, 366, 376, 656.<br />

12. Frederic <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong> Genealogy, 91, 100.<br />

13. Jaffee, People of the Wachusett, 200–238; Nathan O.<br />

Hatch, The Democratization of American<br />

Christianity (<strong>New</strong> Haven, Conn.: Yale University<br />

Press, 1989), 9–11; Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of<br />

Faith: Christianizing the American People<br />

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990),<br />

170–74, 195, 259, 267; Nancy Coffey Heffernan<br />

and Ann Page Stecker, <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>: Crosscurrents<br />

in Its Development (Hanover, N.H.: University<br />

Press of <strong>New</strong> England, 1996), 119–20; Jaffee,<br />

People of the Wachusett, 235; Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A<br />

Religious History of the American People (<strong>New</strong> Haven,<br />

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1972), 403–28.<br />

14. Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Browne,<br />

History of Hillsborough, 1:333–39; <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>, probate record, 1839, Hillsborough County<br />

Probate Court, Nashua, N.H., docket no. 07333.<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>’s estate inventory lists one and one-half pews<br />

and a horse shed at the Baptist Meeting House<br />

as assets.<br />

15. Browne, History of Hillsborough,1:390–91.<br />

16. Robert E. Shalhope, The Roots of Democracy: American<br />

Thought and Culture, 1760–1800 (Boston, Mass.:<br />

Twayne Publishers, 1990), 112–13. The establishment<br />

of social libraries dated back to the mid-eighteenth<br />

century in colonial America. The number of social<br />

libraries incorporated in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> grew during<br />

the 1790s along with the population and the desire for<br />

self-improvement. See Jim Piecuch, “‘Of Great<br />

Importance Both to Civil & Religious Welfare’: The<br />

Portsmouth Social Library, 1750–1786,” <strong>Historical</strong><br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> 57 (fall/winter 2002): 67–84; Browne,<br />

History of Hillsborough, 1:391; Farmer’s Monthly Visitor,<br />

April 15, 1839; Secomb, History of the Town of<br />

Amherst, 129–32; Tamara Plakins Thornton,<br />

Cultivating Gentlemen: The Meaning of Country Life<br />

among the Boston Elite, 1785–1860 (<strong>New</strong> Haven,<br />

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1989), 120–30.<br />

17. Donna-Belle Garvin and James L. Garvin, On the<br />

Road North of Boston: <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Taverns and<br />

Turnpikes, 1700–1900 (Concord: <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

<strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, 1988), 48–61; Browne, History<br />

of Hillsborough, 1:302–14, 403, 465; George<br />

Rogers Taylor, The Transportation Revolution,<br />

1815–1860 (<strong>New</strong> York: Harper and Row, 1951),<br />

15–26; Jaffee, People of the Wachusett, 220–21.<br />

18. Browne, History of Hillsborough, 1: 402, 465.<br />

19. Ibid., 1:401–3, 464–65; 2:456; Conroy, In Public<br />

Houses, 189–240.<br />

20. William Stickney, ed, Autobiography of Amos<br />

Kendall (Boston, Mass.: Lee and Shepard, 1872),<br />

43; Browne, History of Hillsborough, 2:459.<br />

21. Garvin and Garvin, On the Road North of Boston;<br />

list of notes due to the estate of <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>,<br />

1839, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers.<br />

22. Taylor, Transportation Revolution, 149–51; Browne,<br />

History of Hillsborough, 1:385–86; <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

to Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>, July 22, 1824, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

Papers, <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>; Peter<br />

A. Wallner, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>: <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>’s<br />

Favorite Son (Concord, N.H.: Plaidswede<br />

Publishing, 2004), 28.<br />

23. Waters, History of Chelmsford, 600; <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>,<br />

“Autobiography”; Resch, Suffering Soldiers, 81, 177;<br />

Alan Taylor, William Cooper’s Town: Power and<br />

Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American<br />

Republic (<strong>New</strong> York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 154–55,<br />

241–43; Jere R. Daniell, Experiment in Republicanism:<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Politics and the American Revolution,<br />

1741–1794 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University<br />

Press, 1970), ix–x, 199–200, 205–7.

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>’s World 21<br />

24. Browne, History of Hillsborough, 1:460, 506;<br />

Charles S. Grant, Democracy in the Connecticut<br />

Frontier Town of Kent (<strong>New</strong> York: W. W. Norton<br />

and Co., 1972), 152; Daniell, Colonial <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong>, 183–86.<br />

25. <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography”; Stanley Elkins<br />

and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism:<br />

The Early American Republic, 1788–1800 (<strong>New</strong><br />

York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 21–25,<br />

263–65; Daniell, Experiment in Republicanism,<br />

206, 217–18, 222, 228, 233–37; <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

to Isaac Brooks, December 26, 1802, <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> Papers.<br />

26. Drew R. McCoy, The Elusive Republic: Political<br />

Economy in Jeffersonian America (Chapel Hill:<br />

Published for the Institute of Early American<br />

History and Culture by the University of North<br />

Carolina Press, 1980), 10, 48–49, 233–52;<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography”; Farmer’s<br />

Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Richard P.<br />

McCormick, The Second American Party System:<br />

Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era (Chapel Hill:<br />

University of North Carolina Press, 1966), 55;<br />

Cole, Jacksonian Democracy, 17–22; Nahum Parker<br />

to <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, December 18, 1807, <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> Papers.<br />

27. <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography”; Farmer’s<br />

Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Cole, Jacksonian<br />

Democracy, 26–27.<br />

28. Secomb, History of the Town of Amherst, 346–51;<br />

Samuel Dinsmoor to <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, Keene,<br />

N.H., December 16, 1822; N. Lord to <strong>Benjamin</strong><br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>, Amherst, N.H., May 27, 1825; and Henry<br />

Hubbard to <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, Charlestown, N.H.,<br />

January 21, 1826, in <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers.<br />

29. Despite the difference in name, Jackson’s new<br />

Democratic party inherited the ideals of<br />

Jeffersonian Republicanism. Committee of the<br />

Bunker Hill Association to <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>,<br />

Boston, Massachusetts, July 1823, and Fabius<br />

Whiting to <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, May 19, 1826, in<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers; Donald R. Hickey, The<br />

War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (Urbana:<br />

University of Illinois Press, 1995), 300–309;<br />

Burstein, America’s Jubilee, 142; <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

Patriot, January 10, June 27, 1825; February 13,<br />

March 13, 1826; Harriet S. Lacy, et al, “<strong>Governor</strong>s<br />

of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>: Biographical Sketches” (<strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, Concord, 1977,<br />

typescript), 63; Caleb Keith, John Brodhead and<br />

Isaac Hill to <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, June 23, 1826,<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers; Cole, Jacksonian<br />

Democracy in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, 63.<br />

30. Cole, Jacksonian Democracy in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, 64;<br />

Nathaniel Bouton, The History of Concord from Its<br />

First Grant in 1725 to the Organization of the City<br />

Government in 1853 (Concord: McFarland and<br />

Jenks, 1856), 525; Message from the <strong>Governor</strong> of <strong>New</strong>-<br />

<strong>Hampshire</strong> to the Legislature, June 8, 1827 (Concord:<br />

N.H. House of Representatives, 1827), 4–7.<br />

31. Proceedings and Address of the <strong>New</strong>-<strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

Republican State Convention . . . June 11 and 12,<br />

1828 (Concord: <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Patriot, 1828);<br />

Cole, Jacksonian Democracy, 68–73; Browne, History<br />

of Hillsborough, 1:452–53; Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong> to<br />

Elizabeth McNeil, January 28, 1828, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

Papers; Lacy, et al., “<strong>Governor</strong>s of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>,”<br />

39–40; Cole, Jacksonian Democracy, 81.<br />

32. Wallner, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>, 35; Message from His<br />

Excellency <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> to the <strong>New</strong>-<strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

Legislature, June 6, 1829 (Concord: N.H. House of<br />

Representatives, 1829), 3–7.<br />

33. Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Elkins<br />

and McKitrick, Age of Federalism, 717; Lawrence<br />

D. Cress, Citizens in Arms: The Army and the<br />

Militia in American <strong>Society</strong> to the War of 1812<br />

(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,<br />

1982), 19; Barry Schwartz, George Washington: The<br />

Making of an American Symbol (Ithaca, N. Y.:<br />

Cornell University Press, 1987), 13–89.<br />

34. Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839; Daniell,<br />

Experiment in Republicanism, 97, 194–95; Browne,<br />

History of Hillsborough, 1:243.<br />

35. <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, “Autobiography.”<br />

36. David Waldstreicher, In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes:<br />

The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820<br />

(Chapel Hill, N.C.: Published for the Omohundro<br />

Institute of Early American History and Culture by<br />

the University of North Carolina Press, 1997),<br />

156; Elkins and McKitrick, Age of Federalism,<br />

700–711; Chandler E. Potter, The Military History<br />

of the State of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong>, From its Settlement,<br />

in 1623, to the Rebellion, in 1861 (1866; reprint,<br />

Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co.,<br />

1972), part 1, p. 386; Browne, History of<br />

Hillsborough, 2:455.<br />

37. Hickey, War of 1812, 5–28; Nahum Parker to<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong>, Washington, D.C., December<br />

18, 1807, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers.<br />

38. Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839.

22 <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong><br />

39. Browne, History of Hillsborough, 1:415; 2:461;<br />

Secomb, History of the Town of Amherst, 201, 204,<br />

242, 256, 259, 365, 367, 377, 656; Frederic <strong>Pierce</strong>,<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> Genealogy, 100, 165–66; Potter, Military<br />

History of the State, 2:289–99.<br />

40. Browne, History of Hillsborough, 2:461; Frederic<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong> Genealogy, 100, 166.<br />

41. Browne, History of Hillsborough, 2:461; Franklin<br />

<strong>Pierce</strong> to <strong>Benjamin</strong> and Anna <strong>Pierce</strong>, June 9, 1828,<br />

Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers; Frederic <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

Genealogy, 100; Register of the Officers and Cadets of<br />

the U. S. Military Academy, June, 1822 (n.p.).<br />

42. Wallner, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>, 25; Scott Lanzendorf,<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Militia Officers, 1820–1850:<br />

Division, Brigade, and Regimental Field and Staff<br />

Officers (Bowie, Md: Heritage Books, 1995), 151;<br />

Wallner, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong>, 133–55.<br />

43. Potter, Military History of the State, part 2, p. 307;<br />

Browne, History of Hillsborough, 1:506; 2: 470.<br />

44. Frederic <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong> Genealogy, 95, 98, 100;<br />

Browne, History of Hillsborough, 1:247; 2:390–94;<br />

<strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> to John McNeil, Hillsborough,<br />

February 18, 1814, <strong>Benjamin</strong> <strong>Pierce</strong> Papers.<br />

45. Browne, History of Hillsborough, 2:455–56;<br />

Frederic <strong>Pierce</strong>, <strong>Pierce</strong> Genealogy, 97; Purcell,<br />

Sealed with Blood, 86–91; Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong> to<br />

General John McNeil, April 1839, Franklin <strong>Pierce</strong><br />

Papers; Farmer’s Monthly Visitor, April 15, 1839;<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Hampshire</strong> Patriot, April 8, April 22, 1839.