Factors affecting the use of screening mammography among African ...

Factors affecting the use of screening mammography among African ...

Factors affecting the use of screening mammography among African ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Vol. 1, 75-82. November/December 1991 Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 75<br />

<strong>Factors</strong> Affecting <strong>the</strong> Use <strong>of</strong> Screening Mammography <strong>among</strong><br />

<strong>African</strong> American Women1<br />

Joan R. Bloom,2 Kyle Grazier, Felicia Hodge, and<br />

William A. Hayes<br />

University <strong>of</strong> California School <strong>of</strong> Public Health, Berkeley, California<br />

94720 [J. R. B.. K. G., F. H.], and Nor<strong>the</strong>rn California Cancer Center,<br />

Belmont, California 94002 [1. R. B., F. H., W. A. H.]<br />

Abstract<br />

Our objective was to determine <strong>the</strong> influence <strong>of</strong> health<br />

consciousness in <strong>the</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong> in<br />

asymptomatic <strong>African</strong> American women. The sample<br />

consisted <strong>of</strong> 670 women who participated in a<br />

ho<strong>use</strong>hold interview in two cities. Logistic regression<br />

was <strong>use</strong>d to determine <strong>the</strong> independent effects <strong>of</strong><br />

health consciousness, holding constant o<strong>the</strong>r factors<br />

believed to be related to <strong>mammography</strong> utilization.<br />

Health insurance, income below <strong>the</strong> poverty line, and<br />

an annual physical were not significant predictors. The<br />

single most important predidor <strong>of</strong> having a<br />

mammogram was <strong>the</strong> regular practice <strong>of</strong> breast selfexamination;<br />

<strong>the</strong> group <strong>of</strong> women who practiced selfexamination<br />

was almost twice as likely to have a<br />

mammogram.<br />

Introduction<br />

Mammography as an effective means <strong>of</strong> reducing cancer<br />

mortality through early detection is well accepted in <strong>the</strong><br />

medical community, particularly for women oven <strong>the</strong> age<br />

<strong>of</strong> 50 (1-5). National studies indicate that in <strong>African</strong><br />

American women oven 40, 83% had heard <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> procedune,<br />

and 59% had had a mammognam, which is a<br />

doubling <strong>of</strong> estimates made as recently as 1987 (6, 7).<br />

These national figures differ from those <strong>of</strong> regional studies<br />

<strong>of</strong> special populations <strong>of</strong> Hispanic and <strong>African</strong> Amenican<br />

women (8, 9) where <strong>the</strong> rates were half as high.<br />

Recent regional estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se particular populations<br />

indicate less dramatic improvements, perhaps reflecting<br />

greaten numbers <strong>of</strong> poorer women than may have been<br />

reached in telephone surveys. These recent surveys also<br />

indicate that far fewer women have had more than one<br />

mammogram (35%) (7).<br />

Several explanations may account for <strong>the</strong> discrepancy<br />

between what seems desirable for cancer control<br />

and current practice. One is cost, which can range from<br />

$40.00 to $200.00. Insurance usually does not pay for<br />

Received 2/13/91.<br />

, Supported by Grant CA40651 from <strong>the</strong> National Cancer Institute.<br />

2 To whom requests for reprints should be addressed, at University <strong>of</strong><br />

California School <strong>of</strong> Public Health, Department <strong>of</strong> Social and Administralive<br />

Health Sciences, Berkeley, CA 94720.<br />

3 The abbreviation <strong>use</strong>d is: HMO, health maintenance organization.<br />

preventive services beca<strong>use</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir demand is predictable,<br />

although several states now mandate that <strong>screening</strong><br />

<strong>mammography</strong> be covered, and Medicare coverage <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>mammography</strong> is now in effect(10, 11).<br />

A second explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> low utilization <strong>of</strong> mammognaphy<br />

is <strong>the</strong> reluctance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> physician to recommend<br />

it. A decade ago <strong>the</strong> radiological risk posed by<br />

<strong>mammography</strong> was well publicized; this frightened<br />

women away from accepting physicians’ advice that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

be screened and discouraged physicians from recommending<br />

<strong>mammography</strong> to asymptomatic women (12).<br />

While current technology relies on lower doses <strong>of</strong> nadiation,<br />

many women still shy away from radiation exposure<br />

and, in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> symptoms, <strong>the</strong>ir physicians may<br />

be reluctant to recommend it. A recent survey <strong>of</strong> primarycane<br />

physicians by <strong>the</strong> American Cancer Society indicates<br />

that <strong>the</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> physicians reporting that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

completely agree with American Cancer Society guidelines<br />

regarding <strong>mammography</strong> has increased in <strong>the</strong> past<br />

5 years from 41% to 72%. Only 37% indicate that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

actually follow <strong>the</strong>se guidelines. Cost (39%) and radiation<br />

exposure (25%) were <strong>the</strong> previous major sources <strong>of</strong><br />

disagreement, but physicians now cite disagreement with<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> guidelines. Some physicians still feel that<br />

35-39 is too young for a baseline mammogram (35%)<br />

and that annual <strong>screening</strong> after age 50 is too frequent<br />

(29%). Little disagreement was expressed with <strong>the</strong> biennial<br />

<strong>screening</strong> recommendation for ages 40-50 (13).<br />

Since patients rarely reject <strong>the</strong>ir physicians’ recommendation<br />

to have a mammognam, physician factors may play<br />

a major role (14).<br />

A third explanation is based on women’s health<br />

consciousness. Health consciousness is exhibited in behaviors<br />

and in expressions <strong>of</strong> beliefs. Performance <strong>of</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r health behaviors, including breast self-examination,<br />

is positively associated with <strong>mammography</strong> <strong>use</strong> (15). In<br />

this study, <strong>the</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong> was also associated<br />

with increased knowledge <strong>of</strong> cancer detection and treatment<br />

procedures. Within this model, health-conscious<br />

women are assumed to be more aware <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong><br />

breast cancer and more likely to request <strong>mammography</strong><br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r cancer <strong>screening</strong> tests. Closely related to consciousness<br />

about health is <strong>the</strong> perception <strong>of</strong> an individual’s<br />

own risk <strong>of</strong> cancer, specifically personal vulnenability<br />

to breast cancer. One review found that increasing<br />

self-estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> breast cancer are positively<br />

associated with <strong>mammography</strong> <strong>use</strong> (16). Perceptions<br />

<strong>of</strong> vulnerability have also been found to influence<br />

help-seeking, <strong>the</strong> purchase <strong>of</strong> health insurance, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

health-related behavior in multiple plan choice situations<br />

(17-19).<br />

The purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> current study is to evaluate <strong>the</strong><br />

role <strong>of</strong> health consciousness in <strong>the</strong> light <strong>of</strong> two alternative<br />

explanations for <strong>the</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong> by<br />

Downloaded from cebp.aacrjournals.org on December 2, 2011<br />

Copyright © 1991 American Association for Cancer Research

76 Use <strong>of</strong> Screening Mammography <strong>among</strong> <strong>African</strong> American Women<br />

asymptomatic women. Of particular interest is <strong>the</strong> application<br />

<strong>of</strong> this model <strong>of</strong> <strong>screening</strong> behavior to <strong>African</strong><br />

American women.<br />

Methods<br />

Background<br />

This study is part <strong>of</strong> an intervention program to decrease<br />

<strong>the</strong> avoidable mortality from cancer <strong>among</strong> <strong>African</strong> Amenican<br />

residents <strong>of</strong> an urban community in nor<strong>the</strong>rn California.<br />

Prior to <strong>the</strong> initiation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> intervention program,<br />

a ho<strong>use</strong>hold survey was conducted in 1986 in two communities<br />

with large <strong>African</strong> American populations (9).<br />

Survey<br />

Design<br />

A two-stage probability sample was drawn (census blocks<br />

and ho<strong>use</strong>holds within blocks). One hundred randomly<br />

selected blocks were selected from each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two<br />

communities (San Francisco and Oakland, California).<br />

Using <strong>the</strong> Kish (20) procedure, randomly selected mdividuals<br />

from <strong>the</strong> sampled ho<strong>use</strong>holds participated in a<br />

face-to-face interview. If <strong>the</strong> individuals were not at<br />

home during <strong>the</strong> first visit, intensive follow-up efforts<br />

were made to interview <strong>the</strong> selected respondents. Individuals<br />

20 years old or older were eligible to participate.<br />

The response rate was 67.6% in one community, resulting<br />

in 568 completed interviews, and 69.1% in <strong>the</strong> second<br />

community, resulting in 569 completed interviews.<br />

To determine whe<strong>the</strong>r a response bias existed, analyses<br />

were completed to determine <strong>the</strong> nepresentativeness <strong>of</strong><br />

respondents from different geographical areas in <strong>the</strong><br />

target community. Data from <strong>the</strong> 1980 census were<br />

compared by age, income adjusted to 1986 dollars, and<br />

gender. No statistically significant differences were<br />

found. Survey findings from <strong>the</strong> entire sample have already<br />

been reported (9, 21).<br />

Analysis<br />

First, descriptive analyses were performed to examine<br />

<strong>the</strong> bivaniate relationships between ever having had a<br />

mammogram and <strong>the</strong> socioeconomic, attitudinal, and<br />

provider factors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> model. Health consciousness was<br />

<strong>the</strong>n examined using logistic regression. The conceptual<br />

groups <strong>of</strong> variables were forced into <strong>the</strong> model in steps.<br />

Only women in <strong>the</strong> “at risk” sample, over age 35, who<br />

had even had a mammognam (n = 418) were included in<br />

this analysis. This is consistent with <strong>the</strong> American Cancer<br />

Society guidelines, and it recognizes local medical community<br />

practice, which dictates that <strong>screening</strong> should<br />

begin at this earlier age beca<strong>use</strong> younger <strong>African</strong> Amencan<br />

women are at higher risk for breast cancer and have<br />

a higher mortality rate (22). Finally, in order to evaluate<br />

<strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> health consciousness for o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>screening</strong><br />

tests for women, additional analyses were performed<br />

comparing <strong>mammography</strong> to breast physical exams and<br />

Pap test for cervical cancer. To be consistent with <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>screening</strong> guidelines for a physical breast exam, all <strong>the</strong><br />

women over age 20 were included in this analysis.<br />

Measurement<br />

The dependent variable is even having had a mammogram<br />

for <strong>screening</strong> purposes. The cumulative nature <strong>of</strong><br />

this variable recognizes <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> increased age in <strong>the</strong><br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> its occurrence; as such, age is considered a<br />

control ra<strong>the</strong>r than a predictive variable. O<strong>the</strong>r research<br />

on <strong>screening</strong> <strong>mammography</strong> has <strong>use</strong>d such a measure,<br />

as well as <strong>screening</strong> within <strong>the</strong> past year (23). Preliminary<br />

data from o<strong>the</strong>r portions <strong>of</strong> this study revealed that <strong>of</strong><br />

those who reported having had a mammognam, <strong>the</strong> test<br />

had occurred within <strong>the</strong> previous 5 years. However, no<br />

specific questions were asked about <strong>the</strong> pattern <strong>of</strong> <strong>use</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong> prior to <strong>the</strong> study.<br />

The independent variables for <strong>the</strong>se analyses included<br />

patient behaviors and attitudes and physician<br />

behaviors. Respondents’ general health attitudes, beliefs,<br />

and health practices; attitudes and beliefs about cancer;<br />

insurance coverage; and sociodemognaphic descriptors<br />

were collected. Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> provider recommended<br />

<strong>mammography</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>screening</strong> tests during a physical<br />

exam on at any o<strong>the</strong>r time was also ascertained.<br />

Measures <strong>use</strong>d in this analysis are described below.<br />

Health Consciousness. Seven questions explored <strong>the</strong><br />

individual’s health consciousness. The first action-based<br />

variable measured <strong>the</strong> respondent’s frequency <strong>of</strong> breast<br />

self-examination: infrequently (

Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 77<br />

Vulnerability. The respondents’ perceived vulnenability<br />

to cancer was assessed on a 4-point Likert-type<br />

scale. Respondents were asked how likely it was that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y would get cancer. Individuals were “very” or “somewhat<br />

likely” to get cancer (coded as 1) or “not too likely”<br />

on “not likely at all” (coded as 0).<br />

Insurance. The survey probed for <strong>the</strong> existence,<br />

type, and level <strong>of</strong> health insurance within <strong>the</strong> family. Of<br />

importance to <strong>the</strong> study was <strong>the</strong> coverage for <strong>screening</strong><br />

tests, particularly those <strong>use</strong>d for preventive purposes in<br />

asymptomatic individuals. The coverage measure was<br />

tnichotomized: belonging to a health maintenance organization<br />

which covered all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost anchored one end<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> scale; having an indemnity or service benefit plan<br />

on federal entitlements (Medicare on Medicaid) which<br />

covered some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost was <strong>the</strong> intermediate value;<br />

and having no health insurance which covered <strong>the</strong> cost<br />

anchored <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> scale.<br />

Poverty. To enhance understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost implications<br />

<strong>of</strong> having <strong>screening</strong> tests performed, a measure<br />

<strong>of</strong> poverty was also developed. It combines questions on<br />

ho<strong>use</strong>hold size and income. The measure was tnichotomized:<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> family income is more than 200% <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> poverty line (coded as 3), from 100 to 200% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

poverty line (coded as 2), or less than 100% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

poverty line (coded as 1) (24).<br />

Early Detection Tests. The respondents were also<br />

asked whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y had received any early cancer detection<br />

tests as part <strong>of</strong> a routine physical examination on<br />

due to symptoms. The tests assessed in this analysis<br />

included <strong>the</strong> cervical Pap smear, <strong>the</strong> clinical breast exam,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> mammognam.<br />

Willingness to Be Tested. Women were also asked<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y would have a mammognam if it were necommended,<br />

<strong>the</strong> reasons why <strong>the</strong>y would not have one,<br />

and how safe <strong>the</strong>y believed a mammogram to be. These<br />

data are <strong>use</strong>d in <strong>the</strong> descriptive analysis.<br />

Sociodemographic Characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Respondent.<br />

Chronological age, years <strong>of</strong> education, and several<br />

dimensions <strong>of</strong> access to cane were also ascertained.<br />

Physician Behavior. To determine whe<strong>the</strong>r physician<br />

behavior influenced <strong>the</strong> decision, respondents were<br />

asked whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> provider recommended a mammogram<br />

(or “breast X-ray”) during <strong>the</strong> physical exam on at<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r time, ei<strong>the</strong>r due to symptoms or as a <strong>screening</strong><br />

test. Respondents were also asked whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y had had<br />

<strong>the</strong> mammognam. The latter question was <strong>use</strong>d by itself<br />

for descriptive purposes. In calculating rates <strong>of</strong> women<br />

who had even had a mammognam, only women who<br />

were asymptomatic when <strong>the</strong>y had a mammognam were<br />

included. This measure was also developed for <strong>the</strong> dependent<br />

measure in <strong>the</strong> logistic regression model.<br />

Results<br />

The data reported here are for <strong>the</strong> total sample <strong>of</strong> <strong>African</strong><br />

American female adults from <strong>the</strong> two communities (n =<br />

670). Almost 40% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> respondents were under 35,<br />

30% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> respondents were between 35 and 49, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> remainder <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> respondents were 50 and older.<br />

The sample was generally well educated: 8% had had 8<br />

years <strong>of</strong> education or less, 1 6% had had some high school<br />

education, 36% were high school graduates, 30% had<br />

had some college, and 9% reported <strong>the</strong>y had had four<br />

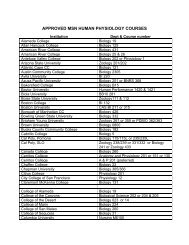

Table 1 Number and percentage <strong>of</strong> women 35 and aver who have<br />

ever had a mammogram (saciodemagraphic variables in <strong>the</strong> model)<br />

In = 415)’<br />

Predictor<br />

Insurance<br />

Age<br />

None<br />

Some<br />

HMO<br />

35-44yr<br />

45-54yr<br />

55-64 yr<br />

>65 yr<br />

Response<br />

Poverty” 100%<br />

101%1a200%<br />

>200%<br />

Education $22,400 for a family <strong>of</strong> four) (24). These<br />

data are representative <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area based on <strong>the</strong> 1980<br />

census.<br />

As seen in Table 1, women belonging to an HMO,<br />

and thus having coverage, are only slightly more likely to<br />

report even having had a mammogram than women who<br />

have some health insurance on none at all.<br />

It was also reasoned that perhaps, due to costs,<br />

physicians would not recommend <strong>mammography</strong> to<br />

women <strong>the</strong>y did not believe could afford it. This would<br />

be evidenced in <strong>the</strong> study in lower rates <strong>of</strong> necommendations<br />

for <strong>mammography</strong> to women at or below <strong>the</strong><br />

poverty line. The data do not support this, as women<br />

whose incomes are at or below <strong>the</strong> poverty line are just<br />

as likely to report ever having had a mammogram as<br />

those whose income is more than twice <strong>the</strong> poverty line.<br />

Finally, cost is cited by only two women as <strong>the</strong> reason<br />

<strong>the</strong>y did not follow <strong>the</strong>ir physicians’ <strong>mammography</strong><br />

recommendations.<br />

With regard to physician behavior, only 31.6% <strong>of</strong><br />

women over 35 stated that <strong>the</strong>ir physician had ever<br />

recommended <strong>the</strong>y have a mammognam. Of this group,<br />

87% indicated that <strong>the</strong>y had actually had <strong>the</strong> mammogram.<br />

When asked if <strong>the</strong>y would have a mammognam (on<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r one) if <strong>the</strong> doctor recommended it, only 30<br />

women said <strong>the</strong>y possibly or definitely would not. Rcasons<br />

given for not having a (ano<strong>the</strong>r) mammogram were<br />

cost (

78 Use <strong>of</strong> Screening Mammography <strong>among</strong> <strong>African</strong> American Women<br />

Table 2 Number and percentage <strong>of</strong> women 35 and o yen who have ever ha d a mammogram (at titude and behavioral variables in <strong>the</strong> model) In = 415)<br />

Ever had a mammogram<br />

Predictor<br />

Response<br />

Number <strong>of</strong><br />

responses<br />

In = 1 1 5)<br />

Percentage<br />

responses<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

x2<br />

Preventive behavior<br />

Hasn’t eaten something beca<strong>use</strong> unhealthy<br />

Eat food good for you<br />

Exercised beca<strong>use</strong> healthy<br />

If I take care <strong>of</strong> myself I can avoid getting sick<br />

Agree<br />

Disagree<br />

Agree<br />

Disagree<br />

Agree<br />

Disagree<br />

Agree<br />

Disagree<br />

Former smoker Yes<br />

No<br />

Breast self-exam Frequent<br />

Regular<br />

Rarely<br />

Annual physical exam Yes<br />

No<br />

56<br />

59<br />

90<br />

25<br />

56<br />

59<br />

102<br />

12<br />

25<br />

90<br />

46<br />

43<br />

26<br />

78<br />

36<br />

30. 1 1 . 1 3<br />

25.4<br />

27.8 0.05<br />

26.6<br />

29.3 0.58<br />

26.0<br />

28.4 1.50<br />

20.7<br />

34.3 2.01<br />

26.1<br />

37.1 9.25<br />

25.9<br />

20.3<br />

41.5 5.21<br />

21.3<br />

0.29<br />

0.82<br />

0.45<br />

0.22<br />

0.45<br />

0.01<br />

0.02<br />

Treatment efficacy’<br />

Surgery does mare good than harm More Good<br />

More Harm<br />

Chemo<strong>the</strong>rapy does mare good than harm More Good<br />

More Harm<br />

Radiation <strong>the</strong>rapy does more good than harm More Good<br />

More Harm<br />

60<br />

48<br />

48<br />

54<br />

42<br />

60<br />

29.6 2.67<br />

28.0<br />

23.4 3.41<br />

31.2<br />

25.2 0.84<br />

29.4<br />

0.26<br />

0.18<br />

0.66<br />

Negative attitudes’<br />

Getting cancer is a death sentence Agree<br />

73<br />

28.2 0.16<br />

0.69<br />

Disagree<br />

42<br />

26.4<br />

If you had cancer, you would ra<strong>the</strong>r not know Agree 25 24.5 0.72 0.40<br />

about it Disagree 90 28.9<br />

Surgery can expose cancer to <strong>the</strong> air and ca<strong>use</strong> Agree 94 28.2 0.49 0.49<br />

it to spread Disagree 20 24.4<br />

Getting treated for cancer is <strong>of</strong>ten worse than Agree 77 27.1 0.01 0.93<br />

<strong>the</strong> disease Disagree 35 27.6<br />

Perceived vulnerability Yes<br />

No<br />

a Middle category excluded from table for clarity.<br />

35<br />

79<br />

19.7 10.04<br />

33.8<br />

0.002<br />

b x2 based an 3 categories and 2 degrees <strong>of</strong> freedom.<br />

‘ Six-paint Likert scale dichotomized for this analysis.<br />

directly questioned about <strong>the</strong> safety <strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong>,<br />

28.6% considered it a little risky and less than 5% considered<br />

it very risky. Even though almost one-third <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sample thought a mammognam was risky, only 1% said<br />

<strong>the</strong>y would not have a (ano<strong>the</strong>r) mammognam due to<br />

radiation risk. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, women are likely to have<br />

a mammogram if <strong>the</strong> physician recommends it.<br />

As shown in Table 2, women who have an annual<br />

physical exam (41.5%, compared to 21.3% who don’t)<br />

and those who frequently or regularly examine <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

breasts for lumps (breast self-exam) are more likely<br />

(31.0% compared to 20.3%) to have a mammognam. In<br />

addition, being olden is strongly related to ever having<br />

had a mammognam (mean, 55.78 versus 49.64; t = 4.37;<br />

P< 0.0001).<br />

Multivariate Analysis. To fully evaluate <strong>the</strong> factors <strong>affecting</strong><br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r a woman had even had a <strong>screening</strong> test<br />

for breast cancer, logistic regression was also <strong>use</strong>d. The<br />

first model addresses only <strong>mammography</strong> and thus includes<br />

only women aged 35 and olden (Table 3). The<br />

second model expands <strong>the</strong> sample to include women 20<br />

years old and older. Even though women between 20<br />

and 35 are unlikely to have a <strong>screening</strong> mammognam,<br />

this model provides <strong>the</strong> necessary comparison group to<br />

women described below who report having a clinical<br />

breast exam and/on a cervical Pap smear (Table 5).<br />

To isolate <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> health consciousness,<br />

each group <strong>of</strong> variables was forced into <strong>the</strong> model using<br />

a forward stepwise program with <strong>the</strong> demographic vanables<br />

first, followed by <strong>the</strong> fiscal factors, attitudes toward<br />

treatment, and attitudes toward cancer. The indicators <strong>of</strong><br />

a preventive orientation were put in last. Several interactions<br />

were tested, an age-squared term was added to<br />

examine <strong>the</strong> age relationship, and <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> potential<br />

correlations <strong>among</strong> variables was carefully examined.<br />

Age/attitude interactions (7 items) were added to<br />

each model and <strong>the</strong>n eliminated. The contribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

interaction terms was not statistically significant for any<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> independent variables; <strong>the</strong>refore, <strong>the</strong> remainder<br />

<strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> analysis is based on <strong>the</strong> assumption that interaction<br />

effects are absent and a simple additive (on <strong>the</strong> logistic<br />

scale) model was <strong>use</strong>d.<br />

Age squared was added to each model to explore<br />

<strong>the</strong> improvement in fit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> models. As expected due<br />

to <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dependent variable, <strong>the</strong> model x2<br />

was improved by its addition (65.96, df= 19 versus 46.65,<br />

dl = 18); <strong>the</strong> coefficient on <strong>the</strong> insurance variable also<br />

improved in significance (from P = 0.07 to P = 0.03). The<br />

Downloaded from cebp.aacrjournals.org on December 2, 2011<br />

Copyright © 1991 American Association for Cancer Research

Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 79<br />

Table 3 Effect <strong>of</strong> health consciousness on rouli ne <strong>screening</strong> by mam mography fo r women 35 and older’ In = 380)”<br />

-<br />

Predictor<br />

. -<br />

Coefficient SE P<br />

Logoddṣ<br />

ratio<br />

95% .<br />

confidence<br />

.<br />

interval<br />

Preventive behavior<br />

Hasn’t eaten something beca<strong>use</strong> unhealthy<br />

Eat food good for you<br />

Exercised beca<strong>use</strong> healthy<br />

If I take care <strong>of</strong> myself I can avoid getting sick<br />

Former smoker<br />

Breast self-exam’<br />

Annual physical exam<br />

-0.151<br />

0.058<br />

0.027<br />

-0.534<br />

0.401<br />

0.396<br />

0.435<br />

0.102<br />

0.1 13<br />

0.093<br />

0.41 5<br />

0.313<br />

0.165<br />

0.265<br />

0.14<br />

0.61<br />

0.77<br />

0.20<br />

0.20<br />

0.02<br />

0.10<br />

0.85<br />

1.06<br />

0.97<br />

0.57<br />

1.49<br />

1.49<br />

1.54<br />

(0.82-1.03)<br />

(0.80-1.25)<br />

(0.83-1.20)<br />

(0.44-2.26)<br />

(0.54-1.85)<br />

(0.72-1.38)<br />

(0.59-1.68)<br />

Treatment efficacy<br />

Surgery does mare good than harm<br />

Chemo<strong>the</strong>rapy does more goad than harm<br />

Radiation <strong>the</strong>rapy does more good than harm<br />

-0.058<br />

0.095<br />

0.040<br />

0.144<br />

0.156<br />

0.158<br />

0.68<br />

0.54<br />

0.80<br />

0.94<br />

1.09<br />

0.96<br />

(0.75-1.33)<br />

(0.74-1.36)<br />

(0.74-1.36)<br />

Negative<br />

altitude<br />

Getting cancer is a death sentence<br />

Ifyou had cancer, you would ra<strong>the</strong>r not know about it<br />

Surgery can expose cancer to <strong>the</strong> air and ca<strong>use</strong> it to spread<br />

Getting treated for cancer is <strong>of</strong>ten worse than <strong>the</strong> disease<br />

-0.010<br />

0.019<br />

-0.001<br />

-0.004<br />

0.069<br />

0.066<br />

0.080<br />

0.073<br />

0.89<br />

0.78<br />

0.99<br />

0.96<br />

0.99<br />

1.02<br />

0.99<br />

1.00<br />

(0.87-1.14)<br />

(0.88-1.14)<br />

(0.85-1.17)<br />

(0.87-1.15)<br />

Perceived vulnerability -0.441 0.265 0.10 0.64 (0.59-1.68)<br />

Insurance” 0.394 0.220 0.07 1.48 (0.65-1.54)<br />

Age#{176} 0.047 0.012 0.00 1.05 10.98-1.02)<br />

Education 0.063 0.054 0.25 1.07 (0.90-1.11)<br />

a -2 log (likelihood ratio) = 395.43; P = 0.002.<br />

b Listwise deletion accounts for 35 missing observations.<br />

‘ Odds ratio from never performing self-exam to frequently performing self-exam is 2.20.<br />

dOdds ratio from no insurance to HMO is 2.199.<br />

#{176} Odds ratio age 35 compared to 65 is 4.096.<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r significant variables in <strong>the</strong> model were not affected.<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> exact fit <strong>of</strong> age in <strong>the</strong> model is unrelated to <strong>the</strong><br />

key variables (i.e., preventive behaviors) and since <strong>the</strong><br />

interpretability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> model is decreased, <strong>the</strong> age ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than <strong>the</strong> age-squared term was <strong>use</strong>d in <strong>the</strong> final model.<br />

With regard to financial barriers to cane, having<br />

health insurance to pay for <strong>screening</strong> tests was expected<br />

to predict increased <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>screening</strong> tests, especially<br />

<strong>mammography</strong>. Closeness to <strong>the</strong> poverty line (a combination<br />

<strong>of</strong> income and family size) was predicted to have<br />

an independent, albeit negative, effect on having a mammognam.<br />

Even though <strong>the</strong> correlation between <strong>the</strong> fiscal<br />

factors (health insurance and <strong>the</strong> poverty index) was<br />

sufficiently low to make <strong>the</strong>m nonmulticolinean, beca<strong>use</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir potential importance <strong>the</strong>y were investigated fun<strong>the</strong>n.<br />

The model was nun with both variables in <strong>the</strong> model,<br />

with each removed separately, and with both removed.<br />

Beca<strong>use</strong> <strong>the</strong>re were incomplete data on income, <strong>the</strong><br />

poverty index could not be constructed for 48 subjects,<br />

although 38 remained in <strong>the</strong> multivaniate model. Thus,<br />

<strong>the</strong> models excluding <strong>the</strong> poverty index include more<br />

subjects. When insurance was removed from <strong>the</strong> model,<br />

<strong>the</strong> significance level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r variables remained<br />

unchanged; <strong>the</strong> likelihood ratio between <strong>the</strong> model including<br />

insurance and excluding it is not significant (x2 =<br />

1 .81 ; df = 1; P > 0.05). The exclusion <strong>of</strong> poverty level is<br />

also not significant (x2 = 0.03; dl = 1; P > 0.05). Since<br />

<strong>the</strong> poverty index is unimportant in <strong>the</strong> model and beca<strong>use</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> missing data, <strong>the</strong> final model was nun without<br />

<strong>the</strong> poverty index, resulting in a sample size <strong>of</strong> 380.<br />

To determine whe<strong>the</strong>r each variable group made a<br />

significant contribution to <strong>the</strong> full model, <strong>the</strong> variable<br />

groups were removed from <strong>the</strong> model separately and<br />

contrasted with <strong>the</strong> full model using <strong>the</strong> likelihood ratio<br />

test. Women’s health consciousness was predicted to be<br />

independently related to having a mammognam (10, 11).<br />

Having a mammognam not only requires a physician- or<br />

patient-initiated request, but also <strong>the</strong> individual’s adherence<br />

to <strong>the</strong> recommendation, which takes place at a<br />

different time and location. The x2 resulting from <strong>the</strong><br />

likelihood ratio test between <strong>the</strong> full model and <strong>the</strong><br />

model without <strong>the</strong> preventive behaviors was 14.17 (df=<br />

7; P < 0.05). When both <strong>the</strong> insurance variable and<br />

poverty variables were removed, none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual<br />

variables in <strong>the</strong> model was affected, and <strong>the</strong> likelihood<br />

ratio for <strong>the</strong> model was not statistically significant (x2 =<br />

1 .79; dl = 2; P > 0.05). When <strong>the</strong> contrast was made<br />

between <strong>the</strong> full model and <strong>the</strong> model resulting from <strong>the</strong><br />

removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> negative attitudes toward cancer, <strong>the</strong><br />

likelihood ratio test was not significant (x2 = 3.51; dl =<br />

4; P > 0.05). Finally, <strong>the</strong> test was not significant when <strong>the</strong><br />

model eliminating attitudes toward treatment efficacy<br />

was compared to <strong>the</strong> full model (x2 = 0.68; dl = 3; P><br />

0.05).<br />

Logistic Model for Mammography. The multiple logistic<br />

model indicates that five factors predict having a mammogram:<br />

(a) Olden women are more likely to have ever<br />

had a mammogram (P < 0.00001). Since <strong>the</strong> outcome<br />

measure is “ever had” a mammogram, it was expected<br />

that age, which was highly significant, would be positively<br />

related to <strong>mammography</strong> <strong>use</strong>. (b) Women who examine<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir breasts are significantly more likely to have a <strong>screening</strong><br />

mammogram (P < 0.02). This was <strong>the</strong> only indicator<br />

Downloaded from cebp.aacrjournals.org on December 2, 2011<br />

Copyright © 1991 American Association for Cancer Research

80 Use <strong>of</strong><strong>screening</strong>Marnmography <strong>among</strong> <strong>African</strong> American Women<br />

Table 4 Probability’ <strong>of</strong> ever having had a mammognam as a function <strong>of</strong><br />

having a routine physical exam, having health insurance, or practicing<br />

breast self-exam for each age group (n = 380)”<br />

Age<br />

40 50 60 70<br />

Insurance<br />

None 0.05 0.08 0.13 0.19<br />

Some 0.08 0.12 0.18 0.26<br />

HMO 0.11 0.17 0.25 0.34<br />

Had a physical exam in <strong>the</strong> last year<br />

Yes 0.08 0.13 0.19 0.27<br />

No 0.05 0.08 0.13 0.19<br />

Perceived vulnerability to cancer<br />

Yes 0.04 0.06 0.09 0.13<br />

No 0.05 0.08 0.13 0.19<br />

Performs breast self-exam<br />

Never 0.05 0.08 0.13 0.19<br />

Regularly 0.08 0.12 0.18 0.26<br />

More frequently 0.1 1 0.17 0.25 0.35<br />

Practices regular breast self-exam’<br />

No health insurance 0.08 0.12 0.18 0.26<br />

Some health insurance 0.11 0.17 0.25 0.34<br />

HMO member 0.16 0.23 0.33 0.44<br />

a Based on estimated values from Table 3.<br />

b Thirty-five missing observations due to listwise deletion in logistic regressian<br />

(Table 3).<br />

‘ For this analysis breast self-exam frequency = 1.<br />

<strong>of</strong> preventive behavior that was significant. Three vanables<br />

were marginally significant. (c) Those with more<br />

insurance coverage are more likely to get a mammognam<br />

(P < 0.07). (d) Women who believe that <strong>the</strong>y are more<br />

likely to get cancer are less likely to have a <strong>screening</strong><br />

mammognam (P < 0.10). (e) Having an annual physical<br />

exam also improves <strong>the</strong> chance <strong>of</strong> having a mammognam<br />

(P < 0.10). The same relationships were reflected for <strong>the</strong><br />

odds ratios presented in <strong>the</strong> table.<br />

The probabilities <strong>of</strong> having a mammognam as a function<br />

<strong>of</strong> several key attributes estimated from <strong>the</strong> model<br />

were also calculated. The probability <strong>of</strong> having a mammognam,<br />

given increasing age, presence <strong>of</strong> health insunance,<br />

perceived vulnerability to cancer, having a routine<br />

physical exam, and self-examination <strong>of</strong> one’s breasts, is<br />

presented in Table 4.<br />

Having insurance which covers <strong>the</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> a mammognam<br />

increases <strong>the</strong> probability <strong>of</strong> having a mammogram<br />

by 2-fold oven no insurance. A 70-year-old woman<br />

with HMO coverage has a 33% chance <strong>of</strong> having a<br />

mammogram, whereas a 40-year-old woman with no<br />

health insurance has only a 5% chance.<br />

Surprisingly, perceiving oneself to be vulnerable to<br />

cancer actually decreases <strong>the</strong> probability <strong>of</strong> having a<br />

mammogram. The differences here, however, are less<br />

marked at <strong>the</strong> earlier ages.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong>re is slightly more than a 2-fold increase<br />

in <strong>the</strong> probability that an individual who tries to examine<br />

her breasts will have a mammognam. Practicing breast<br />

self-exam regularly is as important as having health insurance<br />

on seeing a physician for a yearly physical exam.<br />

A combination <strong>of</strong> practicing breast self-exam regularly<br />

and having health insurance doubles <strong>the</strong> probability <strong>of</strong><br />

having a mammognam (<strong>the</strong> intermediate level, examining<br />

one’s breasts regularly, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> highest level <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> variable is <strong>use</strong>d in this calculation). The strong effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> age is seen in each row <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> table, increasing <strong>the</strong><br />

probability up to 3-fold <strong>of</strong> ever having had a<br />

mammognam.<br />

Logistic Model <strong>of</strong> Screening Tests. Expanding <strong>the</strong> logistic<br />

analysis to include Pap tests and clinical breast exams<br />

indicated that having a routine Pap test in <strong>the</strong> past year<br />

(Table 5) is predicted by having a routine annual physical<br />

exam, being younger, and having no health insurance.<br />

Having a routine clinical breast examination is also predicted<br />

by having a routine physical exam and examining<br />

one’s breasts for lumps. Years <strong>of</strong> education and age (less<br />

so) are also predictors. In addition, disagreeing with <strong>the</strong><br />

attitude that “if you had cancer, you would ra<strong>the</strong>r not<br />

know about it” is positively related to getting an exam.<br />

This final analysis compares <strong>the</strong> predictors <strong>of</strong> ever<br />

having had a routine mammogram with clinical breast<br />

exams and Pap tests. Both age and education are positively<br />

and significantly related to having had a mammogram.<br />

In addition, one measure <strong>of</strong> a preventive onientation<br />

(practicing breast self-examination) also predicts who<br />

will have an exam. In contrast to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>screening</strong><br />

tests, seeing <strong>the</strong> physician for a routine physical exam is<br />

not related to having had a mammogram.<br />

Discussion<br />

These analyses allowed commonly held explanations <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong> to be explored singularly<br />

and with regard to <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> being health conscious.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most widely accepted beliefs is that <strong>the</strong> cost<br />

<strong>of</strong> a mammognam prohibits women from getting one. If<br />

this explanation is valid, <strong>the</strong>n women who have health<br />

insurance should be more likely to receive a mammogram.<br />

This study shows that having health insurance that<br />

covers <strong>screening</strong> services is strongly associated with,<br />

although it does not by itself predict, <strong>mammography</strong>.<br />

The physician may also play a significant role in<br />

determining who gets a mammogram. It is plausible that<br />

<strong>the</strong> physician screens female patients for <strong>the</strong>ir ability to<br />

pay for <strong>mammography</strong>. Thus, if a woman is not believed<br />

to be able to afford a mammognam and/on is uninsured,<br />

<strong>the</strong> test is not recommended unless she is symptomatic.<br />

If this is true, one might expect that women at on below<br />

<strong>the</strong> poverty line would be less likely to have undergone<br />

<strong>mammography</strong>. However, as indicated, <strong>the</strong> poverty indcx<br />

variable does not have a strong effect on <strong>the</strong> probability<br />

<strong>of</strong> having a mammogram.<br />

Finally, <strong>the</strong> model posits that women who are<br />

“health conscious” are more likely to have a mammogram<br />

than are women in general. As indicated in Table 3, only<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> seven indicators <strong>of</strong> health-conscious behavions,<br />

examining one’s breasts, is significantly related to<br />

having a mammognam. Women who routinely practice<br />

breast self-exam are twice as likely to get a mammogram.<br />

Examining one’s breasts increases <strong>the</strong> probability <strong>of</strong> haying<br />

a mammognam to an extent equivalent to that <strong>of</strong> full<br />

insurance coverage and more than that <strong>of</strong> undergoing a<br />

physical exam (Table 4).<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r explanation, not examined in <strong>the</strong> logistic<br />

regression, is <strong>the</strong> physician’s reluctance to recommend<br />

<strong>mammography</strong>. The descriptive data from this study support<br />

this explanation. The data suggest that <strong>mammography</strong><br />

is not widely recommended to asymptomatic<br />

women. Only 31.6% <strong>of</strong> women over 35 and 38.8% <strong>of</strong><br />

Downloaded from cebp.aacrjournals.org on December 2, 2011<br />

Copyright © 1991 American Association for Cancer Research

cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 81<br />

Table 5 Effect <strong>of</strong> preventive behavior, attitudes regarding canc er, and sociademographic fa ctars an routine <strong>screening</strong> fa r women 20 years old and<br />

older In = 604)’<br />

Predictor<br />

Coefficient<br />

Mammography<br />

SE<br />

Caefficient<br />

Breast<br />

exam<br />

SE<br />

Coefficient<br />

Pap<br />

smear<br />

SE<br />

Preventive<br />

behavior<br />

Hasn’t eaten something beca<strong>use</strong> unhealthy<br />

Eat food good for you<br />

Exercised beca<strong>use</strong> healthy<br />

If I take care <strong>of</strong> myself I can avoid getting sick<br />

Former smoker<br />

Breast self-exam<br />

Annual physical exam<br />

-0.1 12 0.095<br />

0.040 0.106<br />

0.014 0.088<br />

-0.455 0.395<br />

0.461 0.291<br />

0.447 0. 1 56b<br />

0.307 0.247<br />

-0.087 0.073<br />

0.030 0.078<br />

0.044 0.067<br />

0.371 0.270<br />

-0.207 0.233<br />

0.253 0. 1 1 7’<br />

0.872 0,180d<br />

-0.061 0.076<br />

-0.006 0.081<br />

-0.046 0.070<br />

-0.475 0.274<br />

0.078 0.243<br />

0. 1 1 8 0.122<br />

0.860 0190d<br />

Treatment efficacy<br />

Surgery does mare good than harm<br />

Chemo<strong>the</strong>rapy does more goad than harm<br />

Radiation <strong>the</strong>rapy does more goad than harm<br />

-0.126 0.135<br />

-0.018 0.143<br />

-0.031 0.144<br />

0.032 -0.101<br />

0.086 0.105<br />

-0.149 0.106<br />

-0.091 0.106<br />

0.069 0.110<br />

0.034 0.111<br />

Negative attitudes<br />

Getting cancer is a death sentence<br />

If you had cancer, you would ra<strong>the</strong>r not know about it<br />

Surgery can expose cancer to <strong>the</strong> air and ca<strong>use</strong> it to spread<br />

Getting treated for cancer is <strong>of</strong>ten worse than <strong>the</strong> disease<br />

-0.022 0.065<br />

-0.008 0.063<br />

-0.055 0.074<br />

-0.036 0.069<br />

0.045 0.048<br />

-0. 1 55 0,049b<br />

-0.014 0.052<br />

-0.067 0.051<br />

0.063 0.050<br />

-0.069 0.050<br />

0.064 0.054<br />

-0.027 0.053<br />

Perceived vulnerability -0.385 0.246 -0.021 0.178 -0.059 0.187<br />

Insurance 0.317 0.206 0.134 0.143 -0.303 0.149’<br />

Age 0.063 0,009” 0.01 1 0.006 -0.055 0,007”<br />

Education 0.087 0.051’ 0.112 0,042” 0.015 0.44<br />

-2 log (likelihood ratio)<br />

47403d 76363d 71457d<br />

a Sixty-six observations missing due to Iistwise deletion.<br />

bp

82 Use <strong>of</strong> Screening Mammography<strong>among</strong><strong>African</strong> American Women<br />

self-exam precedes and is instrumental to having a mammogram.<br />

Before such a conclusion is warranted, longitudinal<br />

data would be necessary to test for a causal<br />

relationship.<br />

Conclusion. For <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> women, cancer control<br />

efforts for this decade are directed toward encouraging<br />

re<strong>screening</strong>. However, since so few minority women<br />

have heeded <strong>the</strong> message to get a mammognam for <strong>the</strong><br />

first time, efforts will have to be made to increase <strong>the</strong><br />

number <strong>of</strong> women who get a first mammogram as well<br />

as to encourage repeat <strong>screening</strong>.<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Appreciation is extended to Dr. Steve Selvin for his assistance on <strong>the</strong><br />

analytic techniques and to Drs. S. Leonard Syme and Patrick Romano for<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir critical review <strong>of</strong> an earlier draft. The technical assistance <strong>of</strong> Joan<br />

Chamberlain is gratefully acknowledged.<br />

References<br />

1. Seidman, A., GeIb, S. K., Silverbeng, F., et al. Survival experience in<br />

<strong>the</strong> breast cancer detection demonstration project. Cancer (Phila.), 37:<br />

258-290, 1987.<br />

2. Shapiro, S. Evidence on <strong>screening</strong> far breast cancer from randomized<br />

trial. Cancer (Phila.), 39: 2772-2782, 1977.<br />

3. Shapiro, S., Venet, W.. Strax, P., Venel, L., and Roesner, R. Ten to<br />

fourteen year effect <strong>of</strong> <strong>screening</strong> on breast cancer mortality. I. NaIl.<br />

Cancer Inst., 69: 349-355, 1982.<br />

4. Tabar, L., Fagerberg, C. J. G., Gad, A., et al. Reduction in mortality<br />

from breast cancer after mass <strong>screening</strong> with mammograph: randomized<br />

trial from <strong>the</strong> Breast Cancer Screening Working Group <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Swedish<br />

National Board <strong>of</strong> Health and Welfare. Lancel, 1: 829-832, 1985.<br />

5. Greenwald, P., and Sondik, E. J. (eds,(. Cancer control objectives for<br />

<strong>the</strong> nation: 1985-2000. NaIl. Cancer Inst. Manogn., 2: 3-74, 1986.<br />

6. Centers for Disease Control. Provisional estimates from <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Health Interview Survey Supplement on Cancer Control-United States.<br />

January-March, 1987. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep., 37: 417-419,<br />

1988.<br />

7, Marchant, D. J., and Sultan, S. M. Use <strong>of</strong> <strong>mammography</strong>-United<br />

States, Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep., 39: 629-630, 1990.<br />

8. Richardson, J., Marks, G., Solis, J. M., Collins, L. M., Birba, L., and<br />

Hissenich, J. C. Frequency and adequacy <strong>of</strong> breast cancer <strong>screening</strong><br />

amang elderly Hispanic women. Prey. Med., 16: 761-774, 1987.<br />

9. Bloom, I. R., Hayes, W. A., Saunders, F., and FlaIl, S. Cancer awarene’ss<br />

and early cancer detection practices <strong>of</strong> Black Americans. Fam. Communily<br />

Health, 10: 19-30, 1987.<br />

10. Woolhandler, S., and Himmelstein, D. V. Re’verse targeting <strong>of</strong> preventive<br />

care due to lack <strong>of</strong> health insurance. AMA, 259: 2872-2874,<br />

1988.<br />

11. Gluck, M. F., Wagner, I. L., and Duffy, B. M. The Use <strong>of</strong> Preventive<br />

Services by <strong>the</strong> Elderly, pp. 77-101. Washington, D.C.: Office <strong>of</strong> Technology<br />

Assessment, Congress <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Slates, 1989.<br />

12. Bailar, J. C., III. Mammography: a contrary view. Ann. Intern. Med.,<br />

84: 77-84, 1976.<br />

13. American Cancer Society. Survey <strong>of</strong> physicians’ attitudes and practices<br />

in early cancer detection. CA Cancer J. Clin., 40: 1990.<br />

14. Reeden, S., Berkanovics, E., and Marcus, A. L. Breast cancer detection<br />

behavior <strong>among</strong> urban women. Public Health Rep., 95: 276-281, 1980.<br />

15. Hobbs, P., Smith, A., George, W. D., and Sallisod, R. D. Acceptors<br />

and rejectors <strong>of</strong> an invitation to undergo breast <strong>screening</strong> compared with<br />

those that referred <strong>the</strong>mselves. I. Epidemiol. Community Health, 34: 19-<br />

22, 1980.<br />

16. Howard, I. Using <strong>mammography</strong> for cancer control: an unrealized<br />

potential. CA Cancer I. Clin., .37: 33-48, 1987.<br />

17. Becker, M. H., and Rosenstock, I. M. Social-psychological research<br />

on <strong>the</strong> determinants <strong>of</strong> preventive health behavior. Behav. Sci. Prey.<br />

Behav., 4: 25-36, 1974.<br />

18. Berki, S. F., Ashcraft, M. L. F., and Penchansky, R. S. Enrollment in a<br />

multi-HMO setting: <strong>the</strong> roles <strong>of</strong> health risk, financial vulnerability and<br />

access to care. Med. Care, 1 5: 682-697, 1977.<br />

19. Crazier, K. L., Richardson, W. C., Martin, D. P., and Diehr, P. <strong>Factors</strong><br />

<strong>affecting</strong> choice <strong>of</strong> health cane plans. Part I. Health Services Res., 20:<br />

659-682, 1986.<br />

20. Kish, L. Procedure for objective respondent selection within <strong>the</strong><br />

ho<strong>use</strong>hold. I. Am. Statist. Assoc., 44: 380-387, 1949.<br />

21. Bloom, I. R., Hayes, W. A., Saunders, F., and Flatt, S. Physician<br />

induced and patient induced utilization <strong>of</strong> early cancer detection tests<br />

<strong>among</strong> black Americans. In: P. Engstrom led.), Advances in Cancer<br />

Control: Innovations and Research. New York: Alan R. Liss, Inc., 1989.<br />

22. Ragland, K., Merrill, D., and Selvin, S. Black-white differences in stage<br />

specific cancer survival: analysis <strong>of</strong> seven selected sites. Am. I. Epidemiol.,<br />

133: 672-682, 1991.<br />

23. Zapka, I. C., Stoddard, A. M., Costanza, M. F., and Creene, H. L.<br />

Breast cancer <strong>screening</strong> by <strong>mammography</strong>: utilization and associated<br />

factors. Am. I. Public Health, 79: 1499-1502, 1989.<br />

24. U.S. Bureau <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Census Current Population Reports Series, P.60<br />

N 147. Popul. Bull., 1783:6-11, 1985.<br />

25. Lerman, C., Rimer, B., Trock, B., Belshem, A., and Engstrom, P. F.<br />

<strong>Factors</strong> associated with repcat adherence to breast cancer <strong>screening</strong>.<br />

Prey. Med., 19: 279-290, 1990.<br />

Downloaded from cebp.aacrjournals.org on December 2, 2011<br />

Copyright © 1991 American Association for Cancer Research