Read the magazine online (PDF) - Committee to Protect Journalists

Read the magazine online (PDF) - Committee to Protect Journalists

Read the magazine online (PDF) - Committee to Protect Journalists

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Mission Journal | A Look Back<br />

AP/Oscar Navarrete<br />

caution, however. “We still don’t really know what’s going <strong>to</strong><br />

happen,” he said and asked that we not use his name. The<br />

publisher at ano<strong>the</strong>r paper, Prensa Libre, was more blunt.<br />

“This is war,” he said, noting that his edi<strong>to</strong>r had recently<br />

been kidnapped by guerrillas and was still missing.<br />

The haggling within our delegation followed us home as<br />

we sought <strong>to</strong> hammer out a statement that all could live<br />

with. Don’t ask me how, but Weinstein ended up drafting <strong>the</strong><br />

Nicaragua and El Salvador sections. (He left <strong>the</strong> delegation<br />

before it got <strong>to</strong> Guatemala.) The statement on Nicaragua<br />

contained political commentary that seemed <strong>to</strong> me extraneous<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> press situation <strong>the</strong>re, and I said so at <strong>the</strong> press<br />

conference we held. Some 75 journalists attended <strong>the</strong> event,<br />

and our statement was written up in The New York Times<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r publications.<br />

Did it have any effect I don’t think so. Conditions for<br />

<strong>the</strong> press worsened in all three countries. The investigation<br />

in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> deaths of <strong>the</strong> Dutch journalists stalled. (Soon after<br />

we issued our statement, I got a call from I.F. S<strong>to</strong>ne angrily<br />

upbraiding us for not digging deeper in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> case.) La<br />

Prensa continued <strong>to</strong> publish throughout <strong>the</strong> Contra war but<br />

was largely defanged. In Guatemala, Rios Montt proved<br />

even more brutal than his predecessor, and <strong>the</strong> edi<strong>to</strong>r of<br />

Diario El Gráfico with whom we’d talked, and who had<br />

asked that his name not be used, was murdered several<br />

years later. Throughout, <strong>the</strong> Reagan administration confined<br />

its concerns over press freedom <strong>to</strong> Nicaragua.<br />

For CPJ, however, <strong>the</strong> mission was invaluable, for it<br />

imparted some important lessons. One was <strong>to</strong> keep delegations<br />

small. The larger <strong>the</strong> group, <strong>the</strong> more unwieldy it<br />

becomes. We also learned <strong>to</strong> avoid selecting participants<br />

according <strong>to</strong> some ideological standard. The key is <strong>to</strong> pick<br />

accomplished journalists with an uncompromising commitment<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> cause of press freedom. Finally, in designing<br />

missions, we found that it helps <strong>to</strong> keep <strong>the</strong> scope limited.<br />

Visiting three war-fractured countries in 10 days was<br />

wildly unrealistic.<br />

Fortified by <strong>the</strong>se lessons, CPJ <strong>to</strong>day conducts more<br />

than a dozen missions a year, pulling <strong>the</strong>m off with great<br />

aplomb. For me, however, <strong>the</strong> memories of that first mission<br />

linger, and while I’ve been on several trips since, I’ve<br />

gone mostly solo. As for Allen Weinstein, <strong>to</strong>day he’s <strong>the</strong><br />

direc<strong>to</strong>r of <strong>the</strong> National Archives. ■<br />

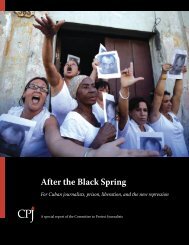

Sandinista soldiers cross a stream during a confrontation with Contras in Las Pinuelas, Nicaragua. Throughout <strong>the</strong> 1980s, <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States expressed concern over press freedom in strife-ridden Nicaragua but not in o<strong>the</strong>r Central American countries.<br />

A Matter<br />

of Commitment<br />

Missions <strong>to</strong> Ethiopia and Eritrea tested CPJ and showed <strong>the</strong> importance of<br />

Washing<strong>to</strong>n’s leadership.<br />

By Josh Friedman<br />

Ethiopia and Eritrea are on <strong>the</strong> frontier of <strong>the</strong> struggle<br />

for press freedom. Isolated in high mountains, <strong>the</strong><br />

two countries test <strong>the</strong> limits of CPJ’s ability <strong>to</strong> aid<br />

endangered journalists. In four missions since 1996 (three<br />

<strong>to</strong> Ethiopia and one <strong>to</strong> Eritrea), we have had mixed success—owing<br />

more <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> changing attitudes of officials in<br />

Washing<strong>to</strong>n than <strong>to</strong> leaders in <strong>the</strong> strategically crucial Horn<br />

of Africa.<br />

What are we dealing with <strong>Journalists</strong> in <strong>the</strong>se two<br />

countries face obstacles those of us in free countries can<br />

only imagine. In Ethiopia, joking about <strong>the</strong> prime minister<br />

sent a car<strong>to</strong>onist <strong>to</strong> jail for years. In Eritrea, an edi<strong>to</strong>rial urging<br />

good government led <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> mass roundup and continued<br />

disappearance of virtually every independent journalist<br />

in <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

Ethiopia has a long his<strong>to</strong>ry of jailing journalists, and<br />

since 2001 Eritrea has had more than a dozen journalists<br />

imprisoned in secret locations without charge. As of 2005,<br />

Ethiopia and Eritrea lagged only China and Cuba as <strong>the</strong><br />

world’s <strong>to</strong>p jailers of journalists.<br />

So when CPJ asked me <strong>to</strong> participate in missions <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se two remote countries I jumped at <strong>the</strong> chance. I had<br />

gotten <strong>to</strong> know <strong>the</strong>m as a newspaper reporter in <strong>the</strong> mid-<br />

1980s when <strong>the</strong>y were one country under a murderous<br />

Soviet-backed dicta<strong>to</strong>rship called <strong>the</strong> Derg, headed by<br />

Mengistu Haile Mariam. A free press did not exist. Now, in<br />

1996, on <strong>the</strong> first of two CPJ missions I accompanied, I<br />

would have a chance <strong>to</strong> see how <strong>the</strong> press had developed<br />

after <strong>the</strong> Derg fell in 1991.<br />

Josh Friedman is direc<strong>to</strong>r of international programs at <strong>the</strong><br />

Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. A former<br />

reporter for Newsday, he won <strong>the</strong> 1985 Pulitzer Prize<br />

for international reporting for his coverage of <strong>the</strong> famine in<br />

Ethiopia.<br />

In a word, it was heartrending. In both countries, eager,<br />

optimistic, and mostly inexperienced young people—and<br />

die-hards from <strong>the</strong> previous regime—had become instant<br />

journalists. In Ethiopia, nearly 100 publications, mostly oneor<br />

two-person affairs, poured forth a mixture of real news,<br />

rumor, accidentally fake news, deliberately fake news, and<br />

ad hominem attacks on <strong>the</strong> country’s new leaders.<br />

The hard-bitten guerrilla leaders who had taken over<br />

Ethiopia—and <strong>the</strong>n Eritrea when it seceded—recoiled in<br />

horror at <strong>the</strong> exuberant free press. After all, <strong>the</strong>se were doctrinaire<br />

Marxists who had spent decades fighting from cave<br />

hideouts where <strong>the</strong>y had enforced discipline through selfcriticism<br />

sessions and strict adherence <strong>to</strong> ideology. Determined<br />

<strong>to</strong> maximize pressure on <strong>the</strong> press despite having<br />

signed human rights accords <strong>to</strong> please Western donors, <strong>the</strong><br />

new leaders of Ethiopia and Eritrea found more subtle ways<br />

<strong>to</strong> intimidate <strong>the</strong> media.<br />

In Ethiopia, for example, edi<strong>to</strong>rs routinely have multiple<br />

criminal charges pending under a repressive 1992 press<br />

law, ensuring that <strong>the</strong>y can easily be sent <strong>to</strong> jail. Authorities<br />

also use under-<strong>the</strong>-radar techniques such as putting pressure<br />

on printers.<br />

So what could a CPJ mission do <strong>to</strong> confront this On <strong>the</strong><br />

ground we could ga<strong>the</strong>r facts <strong>to</strong> inform <strong>the</strong> world what was<br />

happening, buck up endangered journalists, comfort <strong>the</strong><br />

families of <strong>the</strong> jailed or missing, rally <strong>the</strong> small network of<br />

diplomats committed <strong>to</strong> a free press—and plead with and<br />

cajole <strong>the</strong> countries’ new leaders <strong>to</strong> be patient with an<br />

embryonic press.<br />

This last was <strong>the</strong> hardest. For millennia, because of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir isolation on high mountain plateaus, Ethiopia and<br />

Eritrea had developed a culture of distrusting outsiders,<br />

whom <strong>the</strong>y called ferengi. Foreign invaders had come and<br />

gone—often meting out cruelty. One of my best sources in<br />

Ethiopia, scion of a long-deposed aris<strong>to</strong>cratic family, was<br />

76 Fall | Winter 2006<br />

Dangerous Assignments<br />

77