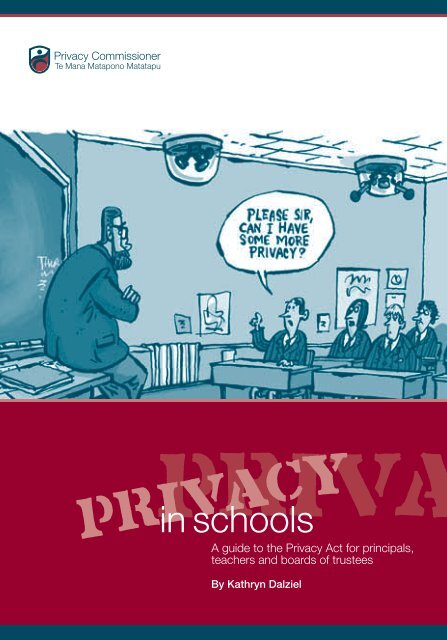

Privacy in Schools - Office of the Privacy Commissioner

Privacy in Schools - Office of the Privacy Commissioner

Privacy in Schools - Office of the Privacy Commissioner

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Priva<br />

<strong>Privacy</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> schools<br />

A guide to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act for pr<strong>in</strong>cipals,<br />

teachers and boards <strong>of</strong> trustees<br />

By Kathryn Dalziel

About <strong>the</strong> author<br />

Kathryn Dalziel is one <strong>of</strong> New Zealand’s lead<strong>in</strong>g privacy lawyers and<br />

works as an associate with Christchurch law fi rm Taylor Shaw<br />

specialis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> privacy law, employment law and civil litigation. Her<br />

publications <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> fi rst edition <strong>of</strong> this work and she has<br />

co-authored <strong>the</strong> chapter on health <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> S P Johnson’s<br />

“Health Care and <strong>the</strong> Law”.<br />

Kathryn presents sem<strong>in</strong>ars and provides privacy advice to a wide<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> agencies <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g schools and universities.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

Published by <strong>the</strong> Offi ce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong><br />

PO Box 10094<br />

Level 4<br />

gen-i Tower<br />

109–111 Fea<strong>the</strong>rston Street<br />

Well<strong>in</strong>gton 6143<br />

© 2009 The <strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong><br />

ISBN 0 478 11728 0<br />

Cartoon © Chris Slane, 2009<br />

Designed by Beetroot Communications, Well<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

www.beetroot.co.nz<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted by Lithopr<strong>in</strong>t Ltd<br />

Well<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

Price: $20<br />

PRIVACY<br />

1

Foreword<br />

Contents<br />

PRIVACY<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> rely on <strong>in</strong>formation about people. The moment a school<br />

collects <strong>in</strong>formation about a student, or a student’s family, <strong>the</strong>re may<br />

be issues about <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is collected, how it is stored,<br />

how it is used and how it is disclosed. Good <strong>in</strong>formation handl<strong>in</strong>g is a<br />

foundation stone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trust that needs to exist between everyone<br />

who participates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school. Of course most schools are<br />

attuned to <strong>the</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir students, <strong>the</strong>ir family or caregivers, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir staff, so handl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation well usually comes naturally to<br />

<strong>the</strong>m. But, as with all personal relationships, situations can arise<br />

where fi nd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ‘right’ answer is not so straightforward.<br />

In 1995 Kathryn Dalziel wrote a book called “The <strong>Privacy</strong> Act for<br />

<strong>Schools</strong>” to help boards <strong>of</strong> trustees, pr<strong>in</strong>cipals and teachers to<br />

understand <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and to apply <strong>the</strong>m to typical<br />

situations <strong>in</strong> schools. The book was popular and proved very useful.<br />

It was obvious, though, from our many calls from schools and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

advisers that <strong>the</strong>re was still a strong need for practical advice about<br />

handl<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> schools.<br />

However, simply repr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> book was no longer go<strong>in</strong>g to address<br />

some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> concerns that schools face. In 2009, mobile technologies<br />

and <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternet (both by students and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> classroom)<br />

have created new challenges for privacy protection. In addition <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are new systems for manag<strong>in</strong>g student enrolment, health records,<br />

and immunisation programmes. <strong>Schools</strong> are tell<strong>in</strong>g us that <strong>the</strong>y need<br />

some help with <strong>the</strong>se issues and <strong>the</strong>y need it now.<br />

So we approached Kathryn to see if she was will<strong>in</strong>g to revise and<br />

update her earlier book – “<strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Schools</strong>” is <strong>the</strong> result. We have<br />

been delighted to work with her on <strong>the</strong> project and hope that you fi nd<br />

<strong>the</strong> book useful.<br />

Marie Shr<strong>of</strong>f<br />

<strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong><br />

Introduction ..........................................................................5<br />

Important def<strong>in</strong>itions ............................................................7<br />

<strong>Privacy</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples ..............................................................10<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 1 – only collect <strong>in</strong>formation that you need to have.............10<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 2 – get <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual concerned .......13<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3 – tell <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual what you are do<strong>in</strong>g ...........................14<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 4 – use lawful, fair and reasonable methods to collect<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation ..................................................................15<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 5 – store and transmit <strong>in</strong>formation securely .......................16<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6 – give people access to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>formation .......................17<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 7 – deal<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>in</strong>correct personal <strong>in</strong>formation .................18<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 8 – check<strong>in</strong>g for accuracy before use ...............................19<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 9 – reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation for as long as necessary .............19<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 10 – use personal <strong>in</strong>formation for its purposes ..................20<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 11 – limits on disclosure <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation ...............20<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 12 – use <strong>of</strong> personal identifi cation numbers ......................22<br />

Relationship between <strong>the</strong> Official Information Act and<br />

<strong>Privacy</strong> Act ..........................................................................24<br />

Application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples .................................26<br />

Appo<strong>in</strong>tment <strong>of</strong> a privacy <strong>of</strong>fi cer ......................................................26<br />

Board meet<strong>in</strong>gs ..............................................................................27<br />

Forms .............................................................................................27<br />

Discipl<strong>in</strong>ary <strong>in</strong>vestigations and hear<strong>in</strong>gs ..........................................29<br />

Report<strong>in</strong>g to parents/guardians ......................................................30<br />

Lawyer for child ..............................................................................31<br />

PRIVACY<br />

2<br />

3

<strong>Privacy</strong> at work<br />

Transfer – an <strong>of</strong> records <strong>in</strong>troduction<br />

between schools ..............................................31<br />

Counsellors and health <strong>in</strong>formation .................................................32<br />

Introduction<br />

Classroom activities/exercises and personal <strong>in</strong>formation .................33<br />

Volunteers ......................................................................................33<br />

Information and communications technology ..................................33<br />

Welcome to “<strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Schools</strong>” – a book designed to help New Zealand<br />

primary and secondary schools and <strong>the</strong>ir associated units fi nd solutions to<br />

issues <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g privacy.<br />

Security cameras/CCTV .................................................................35<br />

Enquiries by Police and o<strong>the</strong>r government agencies .......................35<br />

Compla<strong>in</strong>ts procedure ........................................................37<br />

Contact details for <strong>the</strong> Offi ce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong> .............37<br />

Appendix A: <strong>Privacy</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and sections 27 & 29 ......38<br />

The start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t for New Zealand privacy law is <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act 1993, and<br />

at <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> this Act are 12 <strong>in</strong>formation privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. While <strong>the</strong> privacy<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples are law that schools must follow, <strong>the</strong>y are not so much hard and<br />

fast “rules” as basic guidance, with agreed exceptions, on how schools<br />

should handle personal <strong>in</strong>formation. These privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples are based on<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternationally accepted ways <strong>of</strong> how best to protect privacy. For <strong>in</strong>stance,<br />

you’ll fi nd <strong>the</strong> same ideas <strong>in</strong> Australian, Canadian, British, Hong Kong and<br />

South Korean law, to mention only a few.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

Appendix B: Forms .............................................................47<br />

Appendix C: Request for access to <strong>in</strong>formation checklist ....50<br />

To apply <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> your school, fi rst <strong>of</strong> all you need to<br />

understand <strong>the</strong>m. In this book you will fi nd a discussion <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, with examples to help with <strong>the</strong> explanation. The<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples are all reproduced <strong>in</strong> Appendix A, page 38.<br />

Secondly, you need to work out if <strong>the</strong>re is o<strong>the</strong>r relevant law. This is<br />

because you must follow o<strong>the</strong>r legislation fi rst if it requires you to handle<br />

personal <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> a particular way. For example <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation where<br />

a student is expelled, all schools (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g state, private and <strong>in</strong>tegrated)<br />

need to comply with <strong>the</strong> Education Act by notify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong><br />

Education. In this book you will fi nd more examples where o<strong>the</strong>r legislation<br />

takes precedence over <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.<br />

From <strong>the</strong>re, you need to be able to apply <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and any o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

relevant law to a particular situation. So, under <strong>the</strong> head<strong>in</strong>g “Application <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples”, page 26, you will fi nd discussion <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong><br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and o<strong>the</strong>r law applies to common issues such as enrolment<br />

forms, report<strong>in</strong>g to parents, and behaviour modifi cation or discipl<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

processes. While <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act is not about creat<strong>in</strong>g a paper war <strong>of</strong><br />

authorisations and consents, I have also provided some draft forms <strong>in</strong><br />

Appendix B, page 47, to help schools develop <strong>the</strong>ir own forms.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>re are times when mistakes or errors are<br />

made, <strong>the</strong>re is some <strong>in</strong>formation on compla<strong>in</strong>ts and reference to fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

resources.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

4<br />

5

PRIVACY<br />

Of course, I cannot anticipate or answer every privacy question for<br />

schools and this book is not a complete guide to education law. Some<br />

situations may well require more detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> education law and<br />

<strong>in</strong>deed <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act itself and <strong>in</strong> that situation schools should seek<br />

legal advice.<br />

I have also limited <strong>the</strong> discussion on privacy to students and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

families but <strong>of</strong> course schools also need to deal with privacy issues<br />

<strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g staff. For fur<strong>the</strong>r assistance <strong>in</strong> respect <strong>of</strong> employment matters<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a school, please refer to <strong>Privacy</strong> at Work – a guide to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong><br />

Act for employers and employees, Offi ce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong>,<br />

2008, Well<strong>in</strong>gton.<br />

In summary, this book provides a work<strong>in</strong>g knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciples so that some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> guesswork is taken out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues.<br />

Once you are familiar with <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples you will see that reasonableness<br />

can and will prevail and it is only a matter <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g respect for<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual privacy <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school, just as schools have<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporated anti-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation rights under <strong>the</strong> Human Rights Act.<br />

Education and <strong>Privacy</strong>: two fundamental aspects <strong>of</strong> human development<br />

and human dignity. It is a privilege to br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m toge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Acknowledgement<br />

The author acknowledges <strong>the</strong> wonderful assistance and support<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with peer review and contribution from Katr<strong>in</strong>e Evans,<br />

Assistant <strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g, development and<br />

publication <strong>of</strong> this book.<br />

Important defi nitions<br />

Agency<br />

“Agencies” are people or organisations that have to comply with <strong>the</strong><br />

privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. Nearly everyone who handles personal <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

is an agency. There are some exceptions. For <strong>in</strong>stance, Members<br />

<strong>of</strong> Parliament act<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> an <strong>of</strong>fi cial capacity are not agencies and nor<br />

are Courts and Tribunals, or news outlets <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

news activities.<br />

All types <strong>of</strong> schools are agencies and <strong>the</strong>refore must comply with <strong>the</strong><br />

privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.<br />

Collect<br />

A school is not “collect<strong>in</strong>g” personal <strong>in</strong>formation when it receives<br />

unsolicited <strong>in</strong>formation. However, once a school holds unsolicited<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation, it must apply good <strong>in</strong>formation handl<strong>in</strong>g policies to that<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation – <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g proper storage and check<strong>in</strong>g accuracy before<br />

use.<br />

Confi dentiality<br />

It is important to separate <strong>the</strong> concepts <strong>of</strong> privacy and confi dentiality.<br />

Confi dentiality is an obligation <strong>of</strong>ten associated with pr<strong>of</strong>essions such<br />

as teachers, lawyers and doctors. Confi dentiality is <strong>the</strong> duty to protect<br />

and hold <strong>in</strong> strict confi dence all <strong>in</strong>formation concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> person who<br />

is <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional relationship. There are times when<br />

confi dential <strong>in</strong>formation may be disclosed, but those occasions are<br />

limited.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> date <strong>of</strong> publication, <strong>the</strong> New Zealand Teachers Council Code <strong>of</strong><br />

Ethics records <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g relevant matters <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> confi dentiality<br />

and privacy:<br />

• Teachers’ commitment to learners <strong>in</strong>cludes protect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

confi dentiality <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation about learners obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> course<br />

<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional service, consistent with legal requirements.<br />

• Teachers’ commitments to parents/guardians and family/whānau <strong>of</strong><br />

learners <strong>in</strong>cludes encourag<strong>in</strong>g active <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir children’s<br />

education, acknowledgment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir rights <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g consultation on<br />

PRIVACY<br />

6<br />

7

PRIVACY<br />

<strong>the</strong> care and education <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir children, respect for <strong>the</strong>ir privacy<br />

(author’s note: not confi dentiality), and respect for <strong>the</strong>ir rights to<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>the</strong>ir children, unless that is judged to be not <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> children.<br />

Document<br />

Document is defi ned widely to <strong>in</strong>clude:<br />

• writ<strong>in</strong>g on any material;<br />

• <strong>in</strong>formation on a tape-recorder, computer etc;<br />

• a label;<br />

• a book, map, plan, graph, or draw<strong>in</strong>g; or<br />

• a photograph, fi lm, negative or tape.<br />

Individual<br />

An <strong>in</strong>dividual is a natural person who is alive. The <strong>Privacy</strong> Act does not<br />

govern <strong>in</strong>formation about companies, o<strong>the</strong>r corporate bodies or<br />

deceased people.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>y have no privacy rights under <strong>the</strong> Act, companies and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r corporate bodies are agencies and must comply with <strong>the</strong> Act.<br />

Personal <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

Personal <strong>in</strong>formation means <strong>in</strong>formation about an identifi able <strong>in</strong>dividual.<br />

So obviously anyth<strong>in</strong>g with an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s name attached will be<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation about that <strong>in</strong>dividual. But sometimes <strong>in</strong>formation will clearly<br />

be about a particular <strong>in</strong>dividual even though that <strong>in</strong>dividual is not<br />

named.<br />

Details about an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s circumstances, what that particular<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual said or did, what o<strong>the</strong>rs said or thought about <strong>the</strong>m, or what<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir rights or responsibilities are, would be personal <strong>in</strong>formation about<br />

that person.<br />

Information<br />

‘Information’ is not defi ned <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act or <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Offi cial Information<br />

Act.<br />

This prompted Justice McMull<strong>in</strong> to say:<br />

“From this it may be <strong>in</strong>ferred that <strong>the</strong> draftsman was prepared to adopt<br />

<strong>the</strong> ord<strong>in</strong>ary mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> that word. Information <strong>in</strong> its ord<strong>in</strong>ary dictionary<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g is that which <strong>in</strong>forms, <strong>in</strong>structs, tells or makes aware.”<br />

<strong>Commissioner</strong> <strong>of</strong> Police v Ombudsman [1988] 1 NZLR 385,402<br />

<strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>of</strong>fi cer<br />

All agencies must have a privacy <strong>of</strong>fi cer. A privacy <strong>of</strong>fi cer is <strong>the</strong> person<br />

responsible for handl<strong>in</strong>g privacy issues <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school. The best person to<br />

be a privacy <strong>of</strong>fi cer is someone reasonably senior with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school who<br />

can <strong>in</strong>fl uence <strong>the</strong> school’s policies and practices for handl<strong>in</strong>g personal<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation and who can advise o<strong>the</strong>r staff about what <strong>the</strong>y need to do.<br />

The privacy <strong>of</strong>fi cer will need to:<br />

• be familiar with <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and relevant sections <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

legislation which affects <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong> school manages personal<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation (for example <strong>the</strong> Education Act);<br />

• lead development <strong>of</strong> a privacy policy for <strong>the</strong> school and update that<br />

policy where appropriate;<br />

• deal with compla<strong>in</strong>ts about breaches <strong>of</strong> privacy;<br />

• tra<strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r staff <strong>in</strong> privacy;<br />

• deal with requests for access to personal <strong>in</strong>formation or correction<br />

<strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation; and<br />

• work with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong>, particularly if <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

compla<strong>in</strong>t.<br />

(See chapter on “Application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples”, page 26, for<br />

more <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy <strong>of</strong>fi cer.)<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r legislation<br />

The privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples are subject to all o<strong>the</strong>r legislation. In o<strong>the</strong>r words,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act can be trumped by o<strong>the</strong>r statutes. So, if ano<strong>the</strong>r statute<br />

requires you to handle personal <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> a certa<strong>in</strong> way, <strong>the</strong>n you<br />

must comply with that statute even if it would normally breach <strong>the</strong><br />

privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. This book highlights some relevant examples<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Offi cial Information Act and <strong>the</strong> Education Act.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

8<br />

9

10<br />

PRIVACY<br />

<strong>Privacy</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples<br />

The backbone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act is <strong>the</strong> 12 privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. It is to<br />

<strong>the</strong>se pr<strong>in</strong>ciples that you should turn when deal<strong>in</strong>g with:<br />

• collection <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation;<br />

• storage <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation;<br />

• use <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation;<br />

• disclosure <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation; and<br />

• access to and correction <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

This chapter summarises and expla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> 12 privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. The<br />

full text <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples is set out <strong>in</strong> Appendix A, page 38.<br />

You will see that although <strong>the</strong>re are 12 pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, <strong>the</strong>re are a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> exceptions to <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples which make <strong>the</strong>m guidel<strong>in</strong>es to <strong>the</strong><br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act ra<strong>the</strong>r than rigid statements <strong>of</strong> law.<br />

One important exception to <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples is that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act is<br />

subject to all o<strong>the</strong>r legislation. Therefore your obligations under <strong>the</strong><br />

Education Act must be met before you consider <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act. For<br />

example, all schools are required to comply with <strong>the</strong> requirements for<br />

enrolment records under <strong>the</strong> Education Act and all schools are required<br />

to report any expulsion to <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Education. It is anticipated<br />

that <strong>in</strong> 2010, primary and <strong>in</strong>termediate schools will be required to report<br />

to parents on how <strong>the</strong>ir child is do<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st new National Standards<br />

<strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g, writ<strong>in</strong>g and maths.<br />

If you have any questions about <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples or if you wish to make a<br />

compla<strong>in</strong>t <strong>the</strong>n you should contact <strong>the</strong> Offi ce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong><br />

<strong>Commissioner</strong>. For contact details, see page 37 and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Commissioner</strong>’s<br />

website, www.privacy.org.nz.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 1 – only collect <strong>in</strong>formation that you need to have<br />

When collect<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>formation about students, <strong>the</strong>ir parents,<br />

caregivers, or families, you must be sure you are collect<strong>in</strong>g it for lawful<br />

purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is necessary for those<br />

purposes.<br />

So what are lawful purposes <strong>of</strong> a school<br />

It is perhaps easiest to defi ne lawful purposes as those that are not<br />

unlawful. So, for example, if a purpose is to breach <strong>the</strong> anti discrim<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

obligations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Human Rights Act or <strong>the</strong> purpose is for crim<strong>in</strong>al<br />

activity, <strong>the</strong>n obviously nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se will be a lawful purpose.<br />

The more challeng<strong>in</strong>g aspect to pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 1 is identify<strong>in</strong>g when it is<br />

necessary to collect <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

A good start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t is <strong>the</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>of</strong>ession’s ethical code.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> date <strong>of</strong> this publication, <strong>the</strong> New Zealand Teachers Council Code<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ethics describes <strong>the</strong> goal or purpose <strong>of</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g which is to atta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

highest standards <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional service <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> promotion <strong>of</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The Code also recognises that this complex pr<strong>of</strong>essional task is<br />

undertaken <strong>in</strong> collaboration with colleagues, learners, parents/guardians<br />

and family/whānau, as well as with members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wider community.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r document to consider is <strong>the</strong> school’s charter or strategic plan<br />

that identifi es <strong>the</strong> school’s mission (vision or purpose), aims, objectives,<br />

directions, and targets toge<strong>the</strong>r with its values or pr<strong>in</strong>ciples (kaupapa<br />

and tikanga). From <strong>the</strong>re, <strong>the</strong> school needs to identify what it needs to<br />

know about students and <strong>the</strong>ir families to meet those purposes.<br />

A good approach for schools is to consider whe<strong>the</strong>r or not <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation is needed to complete a process such as enrolment or an<br />

application to attend a school camp. If so, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> school probably<br />

needs to collect <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation. A fur<strong>the</strong>r check is to see if o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

schools are collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> same <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same<br />

circumstances.<br />

An obvious example is a student’s home address. That <strong>in</strong>formation will<br />

be necessary to complete <strong>the</strong> enrolment process and it is <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

collected by o<strong>the</strong>r schools.<br />

To give ano<strong>the</strong>r example, some schools set <strong>the</strong> celebration <strong>of</strong><br />

achievement as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir vision. That value may mean that one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> purposes for collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation is <strong>the</strong> identifi cation <strong>of</strong> a student<br />

(maybe with a photograph) and <strong>the</strong> publication <strong>of</strong> that student’s results<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r success as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> celebration <strong>of</strong> achievement. In that<br />

scenario, can a school ask for a photograph or consent to use<br />

a photograph<br />

PRIVACY<br />

11

12<br />

PRIVACY<br />

To answer that question, a school should ask itself if it is able to<br />

complete enrolment if a parent/guardian or child refuses to provide a<br />

photograph or consent to a photograph be<strong>in</strong>g used. If a school can<br />

complete enrolment <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation sought is probably not<br />

necessary but optional. If a school cannot complete enrolment without<br />

this <strong>in</strong>formation, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation sought must be provided. To<br />

check this position, <strong>the</strong> school should see if <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Education<br />

has set any guidel<strong>in</strong>es or requirements and <strong>the</strong> school should see what<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r schools are do<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Anticipat<strong>in</strong>g when a school must disclose <strong>in</strong>formation is a useful part <strong>of</strong><br />

identify<strong>in</strong>g purposes. Many questions about privacy can be resolved if<br />

schools can anticipate when <strong>the</strong>y need to disclose <strong>in</strong>formation and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n simply identify that disclosure as part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir purposes for<br />

collection. For example, if <strong>the</strong> school needs to report <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>the</strong><br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Education, or needs to forward school records to o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

schools when a student transfers <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>se will be part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school’s<br />

legitimate purposes for collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

With enrolment and <strong>the</strong> mission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, set out below<br />

are some ideas, <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> purposes, that you might like to consider<br />

for your school. Do not forget that just because it is a lawful purpose,<br />

this does not automatically mean that collection is necessary for that<br />

purpose and a school may need to obta<strong>in</strong> consent before <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

can be used for a particular purpose. For <strong>in</strong>stance, it is arguable that<br />

collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation for an alumni association is not a necessary<br />

activity for a school but a useful adjunct to provid<strong>in</strong>g education. On<br />

that basis you would expect to see on a form, “Do you consent to your<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation be<strong>in</strong>g passed onto <strong>the</strong> Alumni Association”<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> purposes:<br />

• meet<strong>in</strong>g curriculum requirements;<br />

• record<strong>in</strong>g and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g student records <strong>of</strong> academic progress;<br />

• report<strong>in</strong>g to parents/guardians;<br />

• ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> school-home partnership;<br />

• celebrat<strong>in</strong>g/record<strong>in</strong>g achievement/success;<br />

• record<strong>in</strong>g and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g accounts;<br />

• provid<strong>in</strong>g services such as health, <strong>in</strong>formation technology (IT), library<br />

and sports/recreation;<br />

• enabl<strong>in</strong>g discipl<strong>in</strong>e/behaviour management programmes;<br />

• report<strong>in</strong>g/disclos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation to government bodies or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

agencies for <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> fund<strong>in</strong>g or to meet contractual/<br />

legislative obligations (eg M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Education, Work and Income,<br />

and Child, Youth, and Family);<br />

• provid<strong>in</strong>g accurate <strong>in</strong>formation to o<strong>the</strong>r education providers to<br />

ensure proper and safe student transfer;<br />

• ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g alumni records (see comment above);<br />

• market<strong>in</strong>g/public relations (although you should always get consent<br />

from an <strong>in</strong>dividual if <strong>the</strong> school wishes to use his/her name/photo for<br />

publicity);<br />

• ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g school websites; or<br />

• adm<strong>in</strong>istration and plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> human resources (this is relevant to<br />

collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation as part <strong>of</strong> recruitment).<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 2 – get <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

concerned<br />

When collect<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>formation, schools should collect that<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation directly from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual concerned unless one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

exceptions applies. Involv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual from <strong>the</strong> outset and tell<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>m why you need his or her <strong>in</strong>formation and how you are go<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

look after it (see pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3) is all about build<strong>in</strong>g good and honest<br />

communication. This also leads to trust and confi dence which is<br />

essential to all relationships <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> education environment. This pr<strong>in</strong>ciple<br />

is also about accuracy. Usually <strong>the</strong> best person to tell you about him or<br />

herself is <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual concerned.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong> reality is that schools collect signifi cant amounts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation about students from parents or guardians. <strong>Schools</strong> also<br />

collect <strong>in</strong>formation from students about <strong>the</strong>ir families <strong>in</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

circumstances, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g classroom exercises. Sometimes <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual concerned is not <strong>the</strong> best person to give <strong>in</strong>formation about<br />

him or herself – for example, <strong>the</strong> student cannot write or give <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

accurately or you want to <strong>in</strong>vestigate a <strong>the</strong>ft which may <strong>in</strong>volve ask<strong>in</strong>g<br />

one student to reveal what he or she saw ano<strong>the</strong>r student do<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The exceptions cover <strong>the</strong>se situations, although schools should not<br />

lose sight <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> start<strong>in</strong>g idea <strong>of</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g relationships <strong>of</strong> trust, confi dence<br />

and good communication.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

13

14<br />

PRIVACY<br />

A school does not have to collect <strong>in</strong>formation directly from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

when:<br />

• non-compliance would not prejudice <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

concerned for example, collect<strong>in</strong>g enrolment <strong>in</strong>formation from<br />

parents/guardians;<br />

• compliance is not reasonably practicable <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> circumstances <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> particular case, for example, collect<strong>in</strong>g enrolment <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

from parents/guardians;<br />

• compliance would prejudice <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collection, for<br />

example, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> breaches <strong>of</strong> school rules/policies;<br />

• <strong>the</strong> school collects <strong>in</strong>formation from a publicly available publication,<br />

for example, <strong>the</strong> telephone book or <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternet;<br />

• <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual authorises collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation from someone<br />

else, for example, a student authorises a teacher to seek a peer<br />

performance evaluation from ano<strong>the</strong>r student; and<br />

• <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation will not be collated <strong>in</strong> a way that identifi es <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual concerned, for example, statistical <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3 – tell <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual what you are do<strong>in</strong>g<br />

When collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation from an <strong>in</strong>dividual, it is important that <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual should be aware:<br />

• that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is be<strong>in</strong>g collected. For <strong>in</strong>stance, schools should<br />

not, as a general rule (<strong>the</strong>re are exceptions), video or audio tape a<br />

person without that person’s knowledge;<br />

• why it is be<strong>in</strong>g collected and what is go<strong>in</strong>g to be done with it,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> school is go<strong>in</strong>g to disclose it (and, if so, to<br />

whom and why);<br />

• who will see <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation. Only <strong>the</strong> people who need <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation to do <strong>the</strong>ir job should see it (see pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 5);<br />

• who is collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation and where it will be stored;<br />

• if <strong>the</strong> collection is a legal requirement and whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> supply <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation is voluntary or compulsory;<br />

• <strong>the</strong> consequences if <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is not supplied; and<br />

• <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual’s rights <strong>of</strong> access to and correction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>re are situations when a school does not have to comply<br />

with this pr<strong>in</strong>ciple (see Appendix A, page 38), <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school context it is<br />

advisable that all forms used to collect <strong>in</strong>formation conta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation required by pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3. In Appendix B, page 47, <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

some draft forms for consideration.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3 is all about transparency. Individuals cannot control <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation if <strong>the</strong>y do not know it has been collected, why it has been<br />

collected and who has access to it. They need to know that <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

a right to access <strong>the</strong>ir personal <strong>in</strong>formation and request correction, if<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is <strong>in</strong>correct.<br />

Comply<strong>in</strong>g with this pr<strong>in</strong>ciple also creates trust. If a school is open and<br />

transparent about its <strong>in</strong>formation handl<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>the</strong>n people are<br />

more likely to share relevant and accurate <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

The chapter “Application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples”, page 26, has some<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>formation about forms.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 4 – use lawful, fair and reasonable methods to<br />

collect <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> must not collect <strong>in</strong>formation by any unlawful or unfair means.<br />

For example, schools should not, as a general rule, audio or video tape<br />

someone without <strong>the</strong>ir knowledge (see also pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3). Even overt<br />

fi lm<strong>in</strong>g or tap<strong>in</strong>g can cause problems especially <strong>in</strong> areas where <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

a strong expectation <strong>of</strong> privacy like a toilet or chang<strong>in</strong>g area. The<br />

chapter “Application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples”, page 26, has some<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>formation about security cameras/CCTV.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r example <strong>in</strong>volves <strong>the</strong> school <strong>of</strong>fi ce counter. School <strong>of</strong>fi ce/<br />

reception staff need to be careful about ask<strong>in</strong>g questions <strong>in</strong> a public area<br />

that require answers about highly personal and sensitive matters.<br />

The collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation must not unreasonably <strong>in</strong>trude upon <strong>the</strong><br />

personal affairs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> student or <strong>the</strong> student’s family. Care is needed<br />

when approach<strong>in</strong>g matters <strong>of</strong> particular sensitivity (eg health, sexuality,<br />

or matters <strong>of</strong> religious signifi cance). Check that you do need to collect<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation, and, if so, th<strong>in</strong>k about <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual’s needs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

process <strong>of</strong> collect<strong>in</strong>g it. This approach is consistent with a school’s<br />

obligation under <strong>the</strong> Human Rights Act to not ask questions that suggest<br />

<strong>the</strong> school may discrim<strong>in</strong>ate on any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> prohibited grounds.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

15

16<br />

PRIVACY<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 5 – store and transmit <strong>in</strong>formation securely<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> have an obligation to take care <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

<strong>the</strong>y hold. There need to be reasonable measures <strong>in</strong> place to avoid<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation or unauthorised access or use. Nobody wants <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation to end up <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wrong hands or to be tampered with. This<br />

can happen when, for example, an enthusiastic computer studies<br />

student hacks <strong>in</strong>to confi dential school records or student fi les are left<br />

unattended on a teacher’s desk <strong>in</strong> a classroom. <strong>Schools</strong> need to have<br />

secure systems for electronic records as well as paper records.<br />

Obviously mistakes do happen, but <strong>the</strong> key is to take reasonable steps<br />

to prevent those mistakes. <strong>Schools</strong> are busy places with high use<br />

areas which are not just limited to <strong>the</strong> classroom. It is <strong>the</strong>refore important<br />

to have good <strong>in</strong>formation handl<strong>in</strong>g policies that work <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school<br />

environment, based on good practice and which refl ect <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong><br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g education.<br />

The start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t is to identify where <strong>in</strong>formation is held, who has<br />

access to those areas, who has access to <strong>the</strong> computers <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

level <strong>of</strong> access (some systems provide tiered access with access<br />

restricted at different levels), and how <strong>in</strong>formation needs to be shared<br />

across <strong>the</strong> school. You may need to consider <strong>the</strong>se ideas for separate<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school, for example <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fi ce, <strong>the</strong> staffroom, <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fi ces <strong>of</strong><br />

school adm<strong>in</strong>istrators <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>cipals, deputy pr<strong>in</strong>cipals and<br />

assistant pr<strong>in</strong>cipals, counsellors’ <strong>of</strong>fi ces and classrooms.<br />

Some o<strong>the</strong>r matters to th<strong>in</strong>k about <strong>in</strong>clude:<br />

• Physical security: use <strong>of</strong> lockable fi l<strong>in</strong>g cab<strong>in</strong>ets, lock<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>fi ces/<br />

classrooms when not <strong>in</strong> use, host<strong>in</strong>g electronic <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>of</strong>f-site<br />

(eg digital storage), work taken home by staff.<br />

• Operational security: restrict<strong>in</strong>g access to personal <strong>in</strong>formation to<br />

appropriate staff, putt<strong>in</strong>g confi dential/sensitive <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong><br />

separate fi les, us<strong>in</strong>g track and trace systems to identify who has<br />

been access<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

• Security <strong>of</strong> transmission: careful use <strong>of</strong> pigeonholes and<br />

noticeboards, use <strong>of</strong> encryption for emails (th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>of</strong> email as send<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a postcard – it is not secure), <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> pre-programmed email<br />

addresses and fax numbers; not identify<strong>in</strong>g students when seek<strong>in</strong>g<br />

peer support.<br />

• Access and correction<br />

Disposal or destruction <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation: see <strong>the</strong> discussion<br />

under pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 9 which is about how long personal <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

should be held and <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Public Records Act on state<br />

schools. If <strong>in</strong>formation may be destroyed <strong>the</strong>n schools should<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> best approach for disposal. <strong>Schools</strong> need to be<br />

particularly careful with computer records as simply delet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m<br />

does not necessarily mean <strong>the</strong> record is removed from <strong>the</strong> hard<br />

drive <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> computer.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6 – give people access to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

Any person has <strong>the</strong> right to ask a school if it holds <strong>in</strong>formation about<br />

him or her and, <strong>in</strong> most cases, to have access to that <strong>in</strong>formation. This<br />

is an important aspect <strong>of</strong> privacy – people should be able to check<br />

what <strong>in</strong>formation is be<strong>in</strong>g held about <strong>the</strong>m so <strong>the</strong>y have some measure<br />

<strong>of</strong> control over <strong>the</strong>ir personal <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

The request can be <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g or an oral request. The school must:<br />

• provide assistance to <strong>the</strong> requester;<br />

• transfer <strong>the</strong> request to ano<strong>the</strong>r agency if <strong>the</strong> school does not hold<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation but knows someone else does;<br />

• respond with<strong>in</strong> time limits (as soon as practicable but no later than<br />

20 work<strong>in</strong>g days);<br />

• <strong>in</strong>form <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> decision; and<br />

• <strong>in</strong> most <strong>in</strong>stances should make <strong>in</strong>formation available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> form<br />

requested.<br />

State schools cannot charge a person for this request. O<strong>the</strong>r schools<br />

may charge a reasonable fee for provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

There is some personal <strong>in</strong>formation which may be withheld under <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Privacy</strong> Act (see sections 27–29 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act. In Appendix A,<br />

page 38, <strong>the</strong>re are some excerpts from sections 27 and 29). The most<br />

relevant withhold<strong>in</strong>g grounds for schools are set out below. If you are<br />

consider<strong>in</strong>g refus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation, it is recommended that you consult<br />

with your legal advisers.<br />

• Disclosure will mean <strong>the</strong> unwarranted disclosure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affairs <strong>of</strong><br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r person (eg a school may wish to withhold from a student<br />

who is be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vestigated for a breach <strong>of</strong> school rules, <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong><br />

an <strong>in</strong>formant).<br />

PRIVACY<br />

17

18<br />

PRIVACY<br />

• The <strong>in</strong>formation is an evaluation or an op<strong>in</strong>ion compiled solely for <strong>the</strong><br />

purposes <strong>of</strong> award<strong>in</strong>g scholarships or awards, honours or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

benefi ts and <strong>the</strong> evaluation or op<strong>in</strong>ion was given <strong>in</strong> confi dence.<br />

• Disclosure will mean a breach <strong>of</strong> legal pr<strong>of</strong>essional privilege. For<br />

example, <strong>the</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Trustees may withhold its lawyer’s legal<br />

op<strong>in</strong>ion with respect to a student’s expulsion.<br />

• The request is obviously not made for any legitimate reason, or <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formation requested is trivial. While this withhold<strong>in</strong>g ground is<br />

designed to address vexatious requests, which are designed purely<br />

to create trouble, schools should not use this withhold<strong>in</strong>g ground<br />

just because <strong>the</strong> school fi nds <strong>the</strong> request annoy<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

• Disclosure is contrary to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual under <strong>the</strong> age<br />

<strong>of</strong> 16. This does not mean that a student under <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> 16 cannot<br />

access his or her <strong>in</strong>formation. It means a school may withhold a<br />

student’s personal <strong>in</strong>formation, when that student is under <strong>the</strong> age<br />

16, if it is contrary to his or her <strong>in</strong>terests.<br />

When a parent asks a school for <strong>in</strong>formation about him or herself, it is<br />

a request under pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6. When a parent asks a school for <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

about his or her child, it is a different matter. The chapter “Application<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples”, page 26, has some fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>formation about<br />

report<strong>in</strong>g to parents/guardians. In Appendix C, page 50, <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

“Request for access to <strong>in</strong>formation checklist”.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 7 – deal<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>in</strong>correct personal <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

Any person has <strong>the</strong> right to ask a school to correct any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

held about him or her. If <strong>the</strong> school does not th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is<br />

wrong <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> person has <strong>the</strong> right to have a statement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> required<br />

correction/s placed with <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

For example, a school pr<strong>in</strong>cipal might record <strong>the</strong> behaviour <strong>of</strong> a student<br />

<strong>in</strong> a meet<strong>in</strong>g, describ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> student as angry. The student might disagree<br />

with this assessment and ask for <strong>the</strong> record to be corrected. This does<br />

not mean <strong>the</strong> school pr<strong>in</strong>cipal has to change <strong>the</strong> record, if he or she is<br />

satisfi ed that <strong>the</strong> statement was correct. The school need only hold <strong>the</strong><br />

student’s view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> behaviour alongside <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipal’s view.<br />

If <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>in</strong>accurate material, a school does not have to wait for a<br />

request for correction. If <strong>the</strong> school is aware that a record is <strong>in</strong>correct<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> school must amend it.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 8 – check<strong>in</strong>g for accuracy before use<br />

Before us<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>formation, a school must take reasonable<br />

steps to check that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is:<br />

• current;<br />

• relevant;<br />

• complete;<br />

• accurate; and<br />

• not mislead<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

For example, throughout <strong>the</strong> year, schools might like to put rem<strong>in</strong>der<br />

notices <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school newsletter ask<strong>in</strong>g parents/guardians to update<br />

any change <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir contact details.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r example might be when a school receives unsolicited<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation like a compla<strong>in</strong>t about <strong>the</strong> after-school behaviour <strong>of</strong> a<br />

student. Before rely<strong>in</strong>g on this <strong>in</strong>formation, <strong>the</strong> school should check for<br />

accuracy, not only by mak<strong>in</strong>g enquiries <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r witnesses, but also by<br />

ask<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> student concerned.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 9 – reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation for as long as necessary<br />

Personal <strong>in</strong>formation must not be held for longer than is necessary for<br />

<strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, once a school no longer<br />

needs <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>the</strong>n it should not be reta<strong>in</strong>ed.<br />

This pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, like o<strong>the</strong>r pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, is subject to o<strong>the</strong>r legislation.<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> need to keep records for certa<strong>in</strong> periods <strong>of</strong> time to comply<br />

with legal requirements, for example tax adm<strong>in</strong>istration legislation.<br />

Under <strong>the</strong> Public Records Act, state schools also have broader<br />

responsibilities to reta<strong>in</strong> some school records for archival purposes,<br />

and schools cannot destroy or dispose <strong>of</strong> any school records without<br />

Archives New Zealand’s authorisation.<br />

The M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Education toge<strong>the</strong>r with Archives New Zealand has<br />

prepared <strong>the</strong> School Records Retention/Disposal Information Pack<br />

(available at www.m<strong>in</strong>edu.govt.nz/NZEducation/EducationPolicies/<br />

<strong>Schools</strong>/SchoolOperations/Plann<strong>in</strong>gAndReport<strong>in</strong>g/SchoolRecords<br />

Schedule.aspx), which identifi es school records that can be<br />

discharged or destroyed, and those which must eventually be<br />

sent to Archives New Zealand.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

19

20<br />

PRIVACY<br />

These guidel<strong>in</strong>es will also be <strong>of</strong> benefi t to private schools as <strong>the</strong>y set<br />

<strong>the</strong> standard for record retention/disposal.<br />

Apart from keep<strong>in</strong>g records as required by law, schools may want to<br />

reta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> order to provide references, answer requests for<br />

academic records and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> an alumni record long after <strong>the</strong> student<br />

has left <strong>the</strong> school as a service to former students. Reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

digitally makes this less <strong>of</strong> a paper war, but it is over to <strong>the</strong> school to<br />

decide how long it keeps <strong>in</strong>formation for this purpose, as long as this<br />

is with <strong>the</strong> knowledge and consent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> former student.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 10 – use personal <strong>in</strong>formation for its purposes<br />

<strong>Schools</strong> should only use personal <strong>in</strong>formation for <strong>the</strong> purpose for which<br />

it was collected.<br />

For example, if a student consents to be<strong>in</strong>g photographed for a school<br />

project, <strong>the</strong> school may not subsequently use <strong>the</strong> photograph for<br />

promotional advertis<strong>in</strong>g without consent.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r example would be where parents/caregivers have provided <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

contact names and addresses to <strong>the</strong> school, a member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Board <strong>of</strong><br />

Trustees may not use this database to promote his or her bus<strong>in</strong>ess.<br />

Aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>re are exceptions to this pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, namely where <strong>the</strong> alternative<br />

use is:<br />

• directly related to <strong>the</strong> reasons for which <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation was<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed; or<br />

• authorised by <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual; or<br />

• necessary for <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> prevention,<br />

detection, <strong>in</strong>vestigation, prosecution and punishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences; or<br />

• necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imm<strong>in</strong>ent threat to<br />

public health or safety, or <strong>the</strong> life or health <strong>of</strong> any o<strong>the</strong>r person; or<br />

• <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation is publicly available; or<br />

• <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation will not identify <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 11 – limits on disclosure <strong>of</strong> personal <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

The start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t is that a school must look after students’ <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

and not release that <strong>in</strong>formation to third parties.<br />

This pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, like o<strong>the</strong>r pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, is subject to o<strong>the</strong>r legislation. For<br />

example, under <strong>the</strong> Education Act schools are required to collect<br />

essential <strong>in</strong>formation on enrolment and to pass this <strong>in</strong>formation on to<br />

any school to which <strong>the</strong> student transfers.<br />

Under <strong>the</strong> Children, Young Persons and <strong>the</strong>ir Families Act, if a care and<br />

protection co-ord<strong>in</strong>ator from Child Youth and Family seeks <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

<strong>in</strong> relation to care and protection matters, <strong>the</strong>n this <strong>in</strong>formation must be<br />

released.<br />

Courts also have <strong>the</strong> power to order schools to release <strong>in</strong>formation. The<br />

most common example is a search warrant under <strong>the</strong> Summary<br />

Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs Act. A search warrant is a document issued by a Judge,<br />

Court Registrar or Justice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Peace authoris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Police to enter a<br />

specifi ed property to seize goods or documents. If Police have a search<br />

warrant you must let <strong>the</strong>m execute <strong>the</strong> warrant, without <strong>in</strong>terference.<br />

There are exceptions to pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 11. For <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>the</strong> school may<br />

release <strong>in</strong>formation if <strong>the</strong> school has reasonable grounds to believe:<br />

• It is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> purposes for which <strong>in</strong>formation was collected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

fi rst place, for example, report<strong>in</strong>g to parents.<br />

• The <strong>in</strong>formation is <strong>in</strong> a publicly available publication.<br />

• The disclosure is to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual, for example a student r<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>the</strong><br />

school ask<strong>in</strong>g for a result <strong>in</strong> a test. The school should be reasonably<br />

satisfi ed that it is <strong>the</strong> student who is seek<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation about him<br />

or herself.<br />

• The disclosure is authorised by <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual.<br />

• The disclosure is necessary for <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> prevention, detection, <strong>in</strong>vestigation, prosecution and punishment<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences. This can <strong>in</strong>clude provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>the</strong> Police and<br />

to court appo<strong>in</strong>ted “lawyer for child”. The chapter “Application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

privacy pr<strong>in</strong>ciples”, page 26, has some fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>formation about<br />

releas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>the</strong> Police and o<strong>the</strong>r government agencies as<br />

well as <strong>in</strong>formation about releas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation to “lawyer for child”.<br />

• The disclosure is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious and imm<strong>in</strong>ent<br />

threat to public health or safety, or <strong>the</strong> life or health <strong>of</strong> any o<strong>the</strong>r person,<br />

for example, <strong>the</strong> release <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>the</strong> Police or Child Youth and<br />

Family about suspected child abuse.<br />

• The disclosure will not identify <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual.<br />

PRIVACY<br />

21

22<br />

PRIVACY<br />

Keep<strong>in</strong>g You can see <strong>the</strong> word <strong>in</strong>formation “may” is emphasised. Just safe because <strong>the</strong> school<br />

may release <strong>in</strong>formation does not mean it must. For example, many<br />

parents/caregivers will have <strong>the</strong>ir telephone and address <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> local<br />

telephone directory, which is a publicly available publication. This<br />

means that if a person rang <strong>the</strong> school and asked for <strong>the</strong> home phone<br />

number <strong>of</strong> a parent, <strong>the</strong> school may be able to release that <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

However, it does not have to release <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation. As a matter <strong>of</strong><br />

policy most agencies do not provide home phone numbers upon<br />

request, even if <strong>the</strong> phone number is <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> telephone directory.<br />

Before releas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation, schools should ensure <strong>the</strong>y are not <strong>in</strong><br />

breach <strong>of</strong> a school policy or ano<strong>the</strong>r law or legal obligation, for example<br />

breach <strong>of</strong> confi dentiality under a pr<strong>of</strong>essional code <strong>of</strong> ethics (see<br />

“Important defi nitions”, page 7).<br />

• statistical purposes;<br />

• research purposes; and<br />

• ensur<strong>in</strong>g that students’ educational records are accurately<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed.<br />

An example <strong>of</strong> an agency that has access to <strong>the</strong> NSNs is <strong>the</strong> New<br />

Zealand Qualifi cations Authority that uses NSNs to record credits and<br />

qualifi cations ga<strong>in</strong>ed by learners on <strong>the</strong> National Qualifi cations<br />

Framework.<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> limited purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> NSN, schools may want to give<br />

students a separate number or identifi er for <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> school<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istration but should only do if this is necessary.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 12 – use <strong>of</strong> personal identification numbers<br />

A school cannot create a unique identifi er – that is a serial number or<br />

PIN – for a student unless it is necessary to <strong>the</strong> effi ciency <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> school.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> school does apply a number to a student because it is necessary,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n this number must be unique and not <strong>the</strong> same as ano<strong>the</strong>r agency’s<br />

unique identifi er for that person, for example, a public library card<br />

number or IRD number. The school cannot <strong>in</strong>sist that this number be<br />

revealed to anyone else.<br />

An automatic number<strong>in</strong>g system by a computer on enter<strong>in</strong>g enrolment<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation or a school library code number is not a breach <strong>of</strong> this<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>ciple as long as <strong>the</strong> student’s name is clearly identifi able from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>put <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> code number.<br />

In 2006, <strong>the</strong> Education Act was amended to empower <strong>the</strong> M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong><br />

Education to create a unique National Student Number (NSN) for every<br />

student.<br />

Part 30 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Education Act 1989 sets out that <strong>the</strong> NSN can only be<br />

used for <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g purposes:<br />

• monitor<strong>in</strong>g and ensur<strong>in</strong>g student enrolment and attendance;<br />

• ensur<strong>in</strong>g education providers and students receive appropriate<br />

resourc<strong>in</strong>g;<br />

PRIVACY<br />

23

24<br />

PRIVACY<br />

Relationship between <strong>the</strong> Offi cial<br />

Information Act and <strong>Privacy</strong> Act<br />

State sector schools <strong>in</strong> New Zealand are subject to both <strong>the</strong> Offi cial<br />

Information Act (OIA) and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act. This means that <strong>the</strong>y have some<br />

additional obligations to provide <strong>in</strong>formation on request.<br />

If a person asks a school for <strong>in</strong>formation about him or herself, this is<br />

governed by pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Privacy</strong> Act (see <strong>the</strong> earlier discussion<br />

on pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6, page 17).<br />

If a person asks a school for <strong>in</strong>formation about someone else (or about<br />

school policies, facilities, or o<strong>the</strong>r th<strong>in</strong>gs that do not <strong>in</strong>volve <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

about a human be<strong>in</strong>g), <strong>the</strong> OIA applies. The most common example is<br />

a parent ask<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>formation about a child – <strong>the</strong> parent is ask<strong>in</strong>g for<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation about someone o<strong>the</strong>r than him or herself, and you <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

need to th<strong>in</strong>k about that request under <strong>the</strong> OIA.<br />

There are three th<strong>in</strong>gs you have to consider:<br />

1. The start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t under <strong>the</strong> OIA is that <strong>the</strong> school should presume<br />

it has to make <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation available.<br />

2. However, <strong>the</strong>re are good reasons not to provide <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> some<br />

circumstances. Protect<strong>in</strong>g privacy is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reasons why a<br />

school might choose not to release <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> response to a<br />

request.<br />