PERMANENT PEOPLES' TRIBUNAL, SESSION ON COLOMBIA ...

PERMANENT PEOPLES' TRIBUNAL, SESSION ON COLOMBIA ...

PERMANENT PEOPLES' TRIBUNAL, SESSION ON COLOMBIA ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

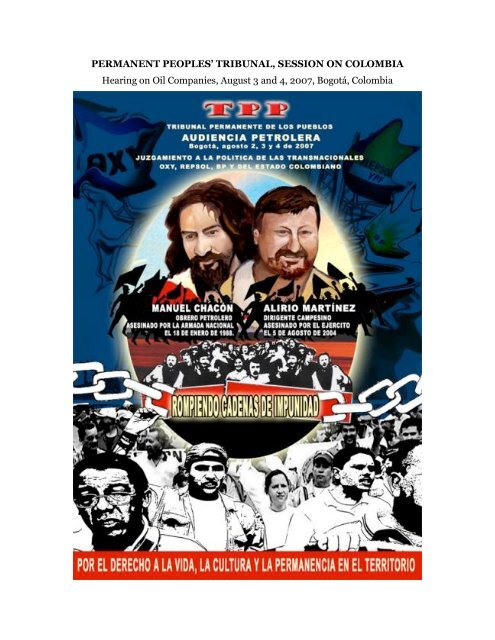

<strong>PERMANENT</strong> PEOPLES’ <strong>TRIBUNAL</strong>, <strong>SESSI<strong>ON</strong></strong> <strong>ON</strong> <strong>COLOMBIA</strong><br />

Hearing on Oil Companies, August 3 and 4, 2007, Bogotá, Colombia

<strong>PERMANENT</strong> PEOPLES’ <strong>TRIBUNAL</strong>, <strong>SESSI<strong>ON</strong></strong> <strong>ON</strong> <strong>COLOMBIA</strong><br />

Hearing on Oil Companies<br />

August 3 and 4, 2007<br />

Bogotá, Colombia<br />

JURY’S DECISI<strong>ON</strong><br />

1. INTRODUCTI<strong>ON</strong><br />

Founded in 1979 as a successor to the Russell Tribunals on Vietnam (1966-1967)<br />

and on the dictatorships in Latin America (1974-1976), the Permanent Peoples’<br />

Tribunal is charged with giving visibility and clarification in legal terms to all<br />

those situations in which the massive violation of fundamental rights is not<br />

institutionally recognized, be they at the national or international level. Spanning<br />

its more than 25-year history and 33 sessions, the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal<br />

has accompanied, anticipated, and supported peoples’ struggles against the<br />

spectre of violations to their fundamental rights, including being denied selfdetermination,<br />

foreign invasions, environmental destruction, and new kinds of<br />

economic dictatorships and slavery.<br />

In August 2007, the trial began of transnationals implicated in the violation of<br />

human rights in Colombia.<br />

To date, hearings have been undertaken on the food and beverage sector (Bogotá,<br />

April 1 and 2, 2006), mining (Medellín, November 10 and 11, 2006), and

iodiversity (Humanitarian Zone of Nueva Esperanza en Dios in the Cacarica<br />

River Basin, Lower Atrato, department of Chocó, February 24 to 27, 2007).<br />

The hearing was preceded by six preliminary hearings, which took place in<br />

Saravena (December 11, 12 and 13, 2006), Barrancabermeja (March 22, 2007), El<br />

Tarra (May 19 and 20, 2007), Cartagena (May 25, 2007), Madrid, Spain (June 15<br />

and 16, 2007) and Glasgow, Scotland (June 21 and 22, 2007). These preliminary<br />

hearings allowed the communities most affected by the acts described herein to<br />

participate directly in the research and testimony gathering process.<br />

The hearing took place in the head offices of the Asociación Distrital de<br />

Educadores, ADE, District Association of Educators, Southern Office, in<br />

accordance with the program detailed in Annex 1. Approximately 1,000 persons,<br />

principally coming from the regions affected by oil transnationals, attended the<br />

hearing. It also had the presence of representatives from the international<br />

network Enlazando Alternativas, Linking Alternatives, which comprises more<br />

than 80 NGOs from Europe and Latin America.<br />

In accordance with the agreement defined with the international foundation Lelio<br />

Basso and the General Secretariat of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, this fourth<br />

hearing has relied on the collaboration of the Observatorio de Trasnacionales,<br />

Megaproyectos y Derechos Humanos, Observatory of Transnationals,<br />

Megaprojects and Human Rights, in the preparation of the indictment’s material<br />

and documentation.<br />

The jury appointed by the PPT included the following judges:<br />

• DALMO DE ABREU DALLARI, professor of Law at the Universidad of Sao<br />

Paulo, member of the International Commission of Jurists, member of the<br />

Defence Council for the Rights of Human Persons (Presidency of the<br />

Republic of Brazil).

• MARCELO FERREIRA, professor of Human Rights at the Faculty of<br />

Philosophy and Letters at the Universidad of Buenos Aires (Argentina).<br />

• ANT<strong>ON</strong>IO PIGRAU SOLÉ, professor of International Public Law at the<br />

University Roviria and Virgili (Tarragona, Spain), author of numerous<br />

writings on international law, and member of various academic circles on<br />

the subject.<br />

And the following joint judges:<br />

• NATIVIDAD ALMÁRCEGUI, secondary teacher, member of the<br />

Confederación General del Trabajo, CGT, General Labour Confederation<br />

(Spain), and coordinator for the Political Solidarity Seminar at the<br />

Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain).<br />

• DOMINGO ANKWASH, president of the Confederación de las<br />

Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana, C<strong>ON</strong>FENAIE,<br />

Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities from the Ecuadorean Amazon.<br />

• DEIRDRE GRISWOLD, journalist, representative from the International<br />

Action Centre, and member of the Secretariat for the Bertrand Russell<br />

Tribunal on War Crimes in 1967.<br />

• RALF HÃUSSLER-EBERT, theologian and reverend from the German<br />

Lutheran Church, member of the Board of Directors of the Ecumenical<br />

Initiative for Central America.<br />

• IV<strong>ON</strong>NE YANEZ, Ecuadorian ecologist, South America Coordinator for<br />

OILWATCH Network (a network for resistance to oil exploitation in<br />

tropical countries).<br />

Father Javier Giraldo and Gianni Tognoni, Secretary General of the PPT in Italy,<br />

also attended the hearing.

The Accusations<br />

Given the responsibility of the named companies, it was indicated Occidental,<br />

British Petroleum, and Repsol have adopted common policies in Colombia.<br />

Specifically, these policies have resulted in the ravaging of natural resources and<br />

systematic violence perpetrated against the population. Consequently, this has<br />

entailed the destruction of the social fabric, the carrying out of murders, the<br />

persecution of social leaders, generalised human rights violations, and the<br />

destruction of indigenous groups.<br />

According to the accusations, these enterprises commit violations to gain the<br />

control of the population and shut down all resistance to their activities. In this<br />

regard, several strategies have been combined, including pressure exerted over<br />

the State to implement policies beneficial to these enterprises (for instance, the<br />

minimization of regular work contracts, the broadening of freelance work<br />

contracts, the privatization of energy companies, the granting of fiscal<br />

advantages, and the handing over of additional oil and gas reserves to these<br />

enterprises). Moreover, the life of society has been militarised, which has only<br />

increased through encouraging corruption, the application of Plan Colombia, and<br />

the direct support provided by the oil enterprises to the legal and illegal armed<br />

forces.<br />

According to those experts who back the accusations, these three oil<br />

transnationals share similar objectives, which are based on imperialist policies<br />

that have plundered Colombian oil reserves. Moreover, these enterprises employ<br />

such diverse strategies as the concealing of production test results, signing<br />

contracts on unfavourable terms for the nation, carrying out fraudulent<br />

transactions to evade taxes, using the national budget to provide infrastructure<br />

for exploration and construction, invading the ancestral territories of indigenous<br />

groups, entering into security agreements with private security companies and<br />

the military forces, and –through the effective cooperation of the Stateamending<br />

the legal framework regulating this activity in Colombia. Concerning

the last point, this behaviour is symbolized by the more than 605 million dollars<br />

in profits obtained in 2005.<br />

According to the accusation, these enterprises must first remove their enemies in<br />

order to get the oil, no matter if they are environmentalists, workers, campesinos<br />

or indigenous persons opposing these policies and, in keeping with the words of<br />

neoliberals, “creating restrictions to the efficient functioning of markets.”<br />

As is known, oil and gas are non-renewable natural resources. Therefore, their<br />

extraction is definitive. A country, which depletes its reserves, will not recover<br />

them, unless new deposits are found. If the export of oil is carried out irrationally,<br />

as has been done in Caño Limón, Cusiana, and Cupiagua (oil fields with total<br />

reserves reaching 3.5 billion barrels), then these mega-reserves will finish in less<br />

than fifteen years. For instance, the life of Colombia’s biggest oil reserves will not<br />

last more than 30 years. The exploitation of Cira Infantas, another major drilling<br />

project, presently run by Occidental, could last 100 years.<br />

The rate of extraction has been high. In fact, according to ECOPETROL, up to<br />

2002, Occidental had extracted 750 million barrels of oil from Caño Limón, while<br />

British Petroleum had removed 806 million barrels in Cusiana and Cupiaga. To<br />

date, more than 2.5 billion barrels had been taken from both oil fields with a total<br />

value of more than 60 billion dollars, a sum almost equivalent to Colombia’s<br />

combined national and foreign public and private debt.<br />

The following specific accusations were presented against the oil enterprises and<br />

the Colombian State:<br />

Occidental and Repsol are partners in different business activities. Repsol has<br />

become a complement for Occidental’s activities in Colombia. As has been its<br />

practice, the US multinational, Occidental, sold part of its share to the Caño<br />

Limón oil field to Repsol, a Spanish transnational. After reacquiring Shell’s share,<br />

through the purchase of Colcito, which became Occidental Andina, Occidental

sold, through Oxycol, 6.25% of its shares to the transnational Repsol YPF. That<br />

transaction was reported to be worth 150 million dollars. With this agreement,<br />

Repsol began to participate as a minority shareholder in Cravo Norte, made up of<br />

ECOPETROL, holding 50%, and Occidental, represented by its subsidiaries,<br />

Occidental Andina, holding 25%, and Occidental de Colombia, holding 18.75%.<br />

The principal shareholders of Repsol are Spanish financial conglomerates,<br />

including La Caixa, which holds 31%, followed by the Basque-based Bilbao<br />

Vizcaya Argentaria, which holds 9%, and the Castilian energy company Iberdrola,<br />

with 3.5% of the shares. Nonetheless, an increasing amount of US capital is being<br />

invested. One of these US shareholders is an investment firm called Brandes,<br />

which controls 9.4% of the shares. Furthermore, the Spanish oil company has<br />

been developing its partnership with the Occidental Petroleum Corporation.<br />

Repsol, whose principal shareholders are Spanish financial conglomerates<br />

(starting with La Caixa, which controls 31%, followed by the Basque-based Bank,<br />

Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, with 9%, and the Castilian energy company, Iberdrola,<br />

with 3.5% of shares), has a growing amount of investment from US capital. One<br />

of this company’s US-based shareholders is the Brandes Investment Fund, which<br />

controls 9.4% of its ownership. Furthermore, the Spanish-based petroleum<br />

company is developing a growing association with the Occidental Petroleum<br />

Corporation.<br />

After acquiring part ownership of Caño Limón in 2003, Repsol assumed an<br />

enormous responsibility in the genocide committed by the US multinational<br />

against the population in the department of Arauca. Moreover, Repsol became<br />

implicated in the ethnocide perpetrated against the Guahíbos and U’wa<br />

indigenous peoples due the environmental destruction caused from oil<br />

exploitation and the brutal plundering of Colombian natural resources by<br />

multinational corporations. Additionally, a counter-insurgent project has been<br />

developed to wage an extremely aggressive war on the civilian population.

Repsol YPF possesses mining rights over eight blocks in Colombia, seven of<br />

which are for exploration. It has under its control an area of 7,863 square<br />

kilometres. By way of the enterprise Gas Natural, Repsol is also the principal<br />

provider of home heating fuel in the country. This company monopolises the<br />

distribution of natural gas in Bogotá, the Cundinamarca and Boyacá Inter-<br />

Andean Valley, and the Eastern Colombia, to approximately 1.5 million clients.<br />

In the case of Arauca, Repsol has established a strategic alliance with Occidental<br />

and its militarization project. It has also consistently aided in intensifying<br />

conflicts in Arauca. For instance, Repsol’s arrival coincided with the initial<br />

paramilitary actions against the population of Tame (located in Capachos I Block<br />

and one of the municipalities subjected to oil exploration and exploitation) and<br />

the intensification of the armed conflict in the region. In the areas of the Lower<br />

and Middle Atrato and San Juan Rivers (Northwest Colombia), there is also a<br />

significant paramilitary presence where Repsol carries out oil exploration and<br />

exploitation.<br />

Some of its activities are being carried out in the ancestral territory of the U’wa<br />

people. Three drilling operations -Capachos, Caño Limón, and Catleya- are<br />

located very close to indigenous territory, lands divided up by the Colombian<br />

government with the purpose of removing these lands from the reservations in<br />

order to allow these multinationals to carry out the exploitation activities.<br />

1. The Empresa Colombiana de Petróleos, ECOPETROL, Colombian Oil<br />

Enterprise, and the <strong>COLOMBIA</strong>N STATE.<br />

2. OCCIDENTAL, REPSOL, ECOPETROL, and the Colombian State, for the<br />

plundering of natural resources, the destruction of ecosystems, the<br />

contamination of the environment, the destruction of the territory and<br />

culture of the U’wa and Guahiba indigenous communities, and the<br />

genocide against communities and social organizations in the department<br />

of Arauca. Insofar as the latter, this crime is represented by the following

specific cases: the massacres in Santo Domingo, La Cabuya, Tame (the<br />

rural communities of Flor Amarillo, Piñalito, and Cravo Charo), Cravo<br />

Norte, Caño Seco, the murder of Hugo Horacio Hurtado, and the strategy<br />

of systematically implementing the criminal investigation of the region’s<br />

social leaders.<br />

Occidental Petroleum Corporation is a US enterprise founded in 1920. It is<br />

based in the State of California and has operations in several countries<br />

throughout the world, principally in the Middle East and the Americas.<br />

In Colombia, Occidental is accused of encouraging the extermination of<br />

the Unión Sindical Obrera, USO, oil workers trade union for Ecopetrol. In<br />

particular, Occidental is held responsible for the murders of Manuel<br />

Gustavo Chacón, Jorge Orlando Higuita, Auri Sara Marrugo, Enrique<br />

Arellano, and Rafael Jaimes Torra.<br />

In its attempt to hold harmless its exploitation, and with the collusion of<br />

the Colombian State, Occidental has resorted to the most extreme<br />

repressive measures in Arauca, including the mass expulsion of the rural<br />

population through pressure exerted by the military, police, and other<br />

security agencies; directly supporting military actions and encouraging<br />

and waging war to ensure its strategic interests and guarantee the amount<br />

of profit and ongoing flow abroad; US military intervention through Plan<br />

Colombia; the creation of war operation theatres through the<br />

implementation of special legislation (states of internal commotion, states<br />

of exception, states of emergency, areas of recovery and consolidation); the<br />

generalised militarization of Arauca, which involves part of the civilian<br />

population in military programs, institutionalising paramilitary groups<br />

and adapting the judicial system to the interests of the transnational<br />

enterprises; and the breaking up of the social movement.

3. To the British Petroleum Company and the Colombian State, for the<br />

dismemberment of social and campesino movements, the extermination of<br />

the Asociación de Veredas de Cunamá, ASOVEC, Association of Rural<br />

Communities from Cunamá, the Asociación Comunitaria para el<br />

Desarrollo Agroindustrial y Social del Morro, ACDAINSO, Community<br />

Association for Agroindustrial and Social Development in Morro, and the<br />

Asociación Departamental de Usuarios Campesinos, ADUC,<br />

Departmental Association of Campesino Workers, specifically the murders<br />

of Carlos Mesías Arriguí, Daniel Torres, Roque Julio Torres Torres,<br />

Oswaldo Vargas, and Carlos Hernando Vargas Suárez.<br />

The Evidence<br />

Documentary, testimonial and expert-witness evidence was provided to the<br />

Tribunal during the hearing. The amount and wealth of the documentary<br />

evidence was so immense its assessment exceeds the strict margins of this ruling.<br />

Nonetheless, it is annexed separately so it may be included in the deliberative<br />

hearing to be carried out in July 2008.<br />

Testimonial evidence was provided by many persons who were first-hand<br />

witnesses as well as by relatives of the victims who witnessed the murder of their<br />

loved ones. In this respect, as a whole, the testimony was emotional and<br />

unnerving. Some of the witnesses also expressed the chance of reprisals being<br />

carried out after they return to their places of origin due to their testimony.<br />

The expert witness testimony provided a general approach to the situation in<br />

Colombia with respect to the economy, politics, and the social and armed conflict,<br />

and especially the impact of US military policy in the region.

ASSESTMENT OF THE ACTS<br />

The Different Aspects<br />

SPECIFICITY OF THE OIL INDUSTRY<br />

It is important to mention that the oil industry follows a dynamic of capitalist<br />

accumulation and national security for countries highly dependent on energy.<br />

First, due to the strategic character of the hydrocarbon, the most powerful<br />

economic groups in all of history –oil corporations- have been able to consolidate<br />

due to the enormous economic surplus generated by oil activity over the last<br />

decades.<br />

Second, it is publicly known world oil reserves are diminishing in a fast and<br />

irreversible manner, which has made these resources an ever more prized asset.<br />

Access to these reserves has also become a matter of national security for<br />

industrialized nations, especially European states and the United States,<br />

principle consumer and country most dependent on fossil fuels in the world.<br />

In all phases -exploitation, extraction, transport, refining, or consumption-, oil<br />

activities cause catastrophic and irreparable social and environmental impact on<br />

a local and global level. Nonetheless, corporate greed and the increasing demand<br />

for energy has forced the expansion of oil activities into areas of high biodiversity<br />

as well as indigenous territories.<br />

The strategies of oil industry multinationals have no limits. For instance, they<br />

collude with the international financial system, forcing producer countries to<br />

become indebted in order to perpetuate the extraction and exportation of natural<br />

resources. These corporations also pressure governments to ease environmental,<br />

labour and fiscal legislation in order to be able to act more freely and obtain more<br />

revenue. Moreover, oil enterprises force the dismemberment and privatization of

state-owned enterprises. They also reach agreements with international<br />

organisations in order to clean up their image socially and environmentally.<br />

Lastly, they create alliances with local mafias, the regular army, and paramilitary<br />

forces -accused of murdering, torturing, persecuting, or disappearing community<br />

leaders- in order to undertake their operations with total security.<br />

These and other strategies allow them to act with an aura of supposed corporate<br />

social responsibility and respect for human rights. However, public accusations<br />

and evidence continually come to light, describing their direct responsibility for<br />

environmental crimes in polluting land, rivers, and oceans; for the loss of forests<br />

and biodiversity; for attacks on economic, social and cultural rights of the<br />

population where operations are undertaken; for provoking displacement and<br />

thousands of social and environmental refugees; and for destroying sources of<br />

subsistence, affecting their food security, and putting at risk the survival of entire<br />

cultures and peoples.<br />

These oil enterprises violate fundamental, collective and environmental rights.<br />

Furthermore, they become covert or overt assassins and act under a systematic<br />

impunity by distorting the rule of law and benefiting from the armed conflict.<br />

The governments of the countries where these oil enterprises are based are<br />

equally responsible for allowing the impunity of these enterprises. These<br />

governments are also responsible for encouraging the repression and<br />

militarization of these oil rich areas and for creating conditions encouraging<br />

ongoing fear, invasion and war against persons living in these areas or opposing<br />

the resulting social and environmental impact.<br />

In Colombia, transnational oil enterprises obtain real profits of over 80%. This is<br />

only possible under the militarization of the production facilities. Even though<br />

this hearing has focused only on the previously cited enterprises, all of the major<br />

oil enterprises in the world currently operate in Colombia.

HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATI<strong>ON</strong>S<br />

Given the previously indicated conditions and the context of the social and armed<br />

conflict faced by the Colombian people, and considering the documents and<br />

testimonials gathered, the existence of generalised and systematic violations to<br />

human rights is evident.<br />

First of all, grave violations to the right to life and the physical integrity of many<br />

persons were made clear with cases of murders, massacres (the bombardment of<br />

Santo Domingo, as well as the massacres at Caño Seco, Tame-Piñalito, Flor<br />

Amarillo, Cravo Charo, La Cabuya, and Cravo Norte), torture, and death threats.<br />

During the hearings, several witnesses also provided testimony on the crimes<br />

committed against their family members (mothers, father, siblings, children, and<br />

cousins).<br />

Moreover, an ongoing persecution has been verified against trade union leaders,<br />

to the point it may be claimed Colombia is the country with the greatest risk for<br />

carrying out said activity. More than three thousand trade unionists have been<br />

murdered over the last twenty years. An exemplary case is the persecution<br />

subjected upon the leaders and rank and file members of the Unión Sindical<br />

Obrera, which over the last twenty years has witnessed the murder of 105<br />

members, in addition to other cases of forced disappearances, kidnappings,<br />

physical attacks, internal displacement, and exile.<br />

CRIMINALISATI<strong>ON</strong> OF SOCIAL PROTEST<br />

Furthermore, the evidence provided confirms a panorama of systematic<br />

persecution against all forms of opposition to the interests of the implicated oil<br />

enterprises. Operationally, this persecution is ensured through the<br />

criminalisation of social protest, arbitrary criminal investigations, and mass<br />

detentions, as has occurred on different occasions in Saravena. In some cases,<br />

these proceedings have even convicted the persecuted persons. In this respect,

when a witness, who had been detained and convicted for rebellion, referred to<br />

the moment of her capture, she said: “as an educator, I was worried we were<br />

running out of students since the government required a minimum number of<br />

students […]. We met in spite of the plan announced by the government to close<br />

the schools.” Then, “they came into the room where I was resting and screamed:<br />

Where are the weapons”<br />

RESTRICTI<strong>ON</strong>S TO THE FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT<br />

The Tribunal was also able to verify the violation to the right to the freedom of<br />

movement, recognised in the Colombian constitution and international<br />

legislation (which is a part of the Colombian legislation). Specifically, according<br />

to a witness, so called areas of exclusion have been established in which a virtual<br />

state of war reigns under the direct control of the armed forces and private<br />

security companies at the service of the oil enterprises. The disproportionate<br />

militarization of these areas is demonstrated by the following testimony provided<br />

by a mother describing the murder of her underage child: “my son went to a lake<br />

with a friend to hunt some chigüiros for the festivities and a watchman saw<br />

them and called the army at Caño Limón.” Later, the child was found dead. It is<br />

noteworthy the witness identifies the armed forces as an army belonging to the<br />

transnational enterprise.<br />

Testimony and documents also demonstrated this situation worsened from the<br />

arbitrary nature of the military checkpoints on the roads and the restrictions on<br />

the circulation of food, medicine and other essential goods, bearing in mind the<br />

poverty of these rural communities. According to one witness, “if we were<br />

carrying foodstuff worth more than 150 thousand pesos [approximately 50<br />

euros], it was taken from us, since they said it was meant for the guerrilla […].<br />

We weren’t allowed to have cement or food or nothing of any worth.”

VIOLATI<strong>ON</strong> OF THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES<br />

The oil exploration and exploitation has meant internal displacement, expulsion,<br />

or near extinction for a large portion of indigenous communities (U’wa, Sikuane,<br />

Macaguan, Cuiba, Guahibo, Betoye, Bari, Cofan, Nasa, Inga, Embera Chamí,<br />

Siona, Awá, Pasto, Camsá, Yanacona, and Camentzá) through the invasion and<br />

subsequent destruction of their ancestral territories. Likewise, since oil<br />

exploration and exploitation began in these different regions, indigenous persons<br />

have been the victims of murder, massacres, detentions, and torture at the hands<br />

of State or para-State agents, as these enterprises and the State consider these<br />

communities to be an obstacle to oil extraction.<br />

Frequently, these peoples are accused of being terrorists, guerrilla members,<br />

rebels, or subversives, which is meant to weaken indigenous resistance and<br />

encourage them to abandon their land. Paradoxically, these cultures are<br />

traditionally peaceful and have lived and worked the land for thousands of years.<br />

The process of the gradual abandonment of indigenous lands has been carried<br />

out in violation of the ILO Convention No. 169 on indigenous and tribal peoples,<br />

which expressly establishes the right to consultation on the transfer of their lands<br />

and prescribes said peoples should not be removed from the lands they occupy.<br />

This was recently recognised by Constitutional Court ruling T-880 in relation to<br />

the Barí people, but also extending to all indigenous peoples.<br />

ENVIR<strong>ON</strong>MENTAL DETERIORATI<strong>ON</strong><br />

Petroleum exploration and exploitation activities carried out by transnational<br />

companies and the Colombian government have required a significant amount of<br />

infrastructure, including communication routes, buildings, crude oil transport<br />

systems, oil wells, water treatment facilities, stabilisation ponds, military bases,<br />

and airports and heliports. These projects have destroyed vast expanses of forest

and have affected marshes, wetlands, streams, and rivers within the Orinoco<br />

River Basin, which has gravely altered the natural cycles of the ecosystem.<br />

The surrounding plant and animal population –as well as the health of humanshas<br />

been adversely affected by the following: contamination of different bodies of<br />

water, perforation of oil wells, felling of trees, generation of heavy metallic and<br />

gas waste, alteration of water temperature, emission of carbon monoxide and<br />

carbon dioxide, oxidization of nitrogen and sulphur, uncontrolled burning of<br />

petroleum waste, and spilling of oil waste in pools near oil wells (which<br />

contaminates the water table).<br />

Repression has also been carried out against environmental defence work,<br />

including against State environmental officials as is the case of the murder of<br />

Carlos Hernando Vargas Suarez, director of CORPORINOQUÍA.<br />

IMPUNITY<br />

The right to justice forms a part of the obligation of guarantee. In this respect, the<br />

State must organise the entire State structure to bring about and truly make<br />

effective the achievement of all liberties and rights consecrated in international<br />

human rights treaties. Moreover, this obligation entails the duty of the State to<br />

investigate, try, and punish the responsible parties for the human rights<br />

violations recognised in these treaties.<br />

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has defined impunity in the<br />

following manner: “the total lack of investigation, prosecution, capture, trial,<br />

and conviction of those responsible for violations of the rights protected by the<br />

American Convention.” Likewise, the Court has indicated “the State has the<br />

obligation to use all the legal means at its disposal to combat impunity because<br />

it fosters chronic recidivism of such violations, and total defencelessness of<br />

victims and their relatives.”

The Colombian State has not complied with all of said obligations. In this<br />

respect, the few independent judicial investigations have not completed or passed<br />

the stage of the preliminary investigation, since all investigations are usually<br />

blocked –in the best of cases- by a gagged and inoperative administration of<br />

justice. For instance, the Specialised Prosecutor’s Office is headquartered inside<br />

the installations of the 18th Brigade and has even participated in military<br />

operations. In the same sense, it has been demonstrated judicial cases are<br />

arbitrarily transferred to settings other than with the natural judge (as in the<br />

creation of ad-hoc judges established after the fact and specifically for certain<br />

acts).<br />

In this context, it is timely to make reference to the phenomenon of<br />

paramilitarism in Colombia and its relation with politics. According to one expert<br />

witness, “they dress as senators in the morning, traffic cocaine in the afternoon,<br />

and give orders to the paramilitaries in the evening.”<br />

Paramilitarism concerns the development of a State strategy reaching far beyond<br />

a counter-insurgency policy or a purely military response. In fact, this strategy<br />

reaches deeply into the political, economic and social order. Paramilitarism has<br />

been functional to major financial interests, multinationals, the violent<br />

plundering of property, and drug trafficking. It also concerns a clearly defined<br />

model of society and state. In order to achieve this, paramilitarism has counted<br />

on the unrestricted support of the political and economic elite. Fundamentally, its<br />

actions have targeted the civilian population. In particular, its victims have been<br />

communities (especially women, children, and youth), taking on a critical stance<br />

or opposition to the State policies ignoring their rights. To reach their objectives,<br />

paramilitaries have perpetrated massacres, ethnocides, genocides, magnicides,<br />

murder, torture, forced disappearance, and forced displacement. In other words,<br />

there has been an endless chain of crimes against humanity.<br />

Nevertheless, this massive amount of crimes has been covered up by the<br />

impunity of a policy oriented to protecting the victimizers as well as disregarding

the rights of society and victims to know the truth, achieve justice, and receive<br />

comprehensive reparation. Even though international bodies have repeatedly<br />

recommended for concrete and effective actions to be taken to overcome<br />

impunity, the State has yet to comply.<br />

DETERMINATI<strong>ON</strong> OF RESP<strong>ON</strong>SIBILITIES<br />

Due to the preceding, the Tribunal accuses:<br />

1. The transnational oil enterprises British Petroleum, Occidental Petroleum<br />

Corporation, Repsol YSP, and ECOPETROL:<br />

• For oil exploration and exploitation policies, which result in the<br />

forced displacement of the local populations.<br />

• For oil exploration and exploitation policies lacking any evaluation<br />

of the environmental impact and entailing the destruction of forests<br />

and other natural spaces. (These policies have also resulted in the<br />

grave and increasing contamination of water sources, such as the<br />

Arauca River, which presumes a forced restriction on the ways of<br />

living of the affected population.)<br />

• For the creation of authentic areas of exclusion, which deny citizens<br />

access to large areas surrounding the fields being exploited (areas<br />

characterized by a virtual state of war and a disproportionate<br />

militarization), This has been accomplished by resorting to regular<br />

armed forces, private security companies, and even paramilitary<br />

groups.<br />

• For tolerance of -as well as collusion and coordination with- these<br />

armed groups, directly through subcontracted enterprises, in the<br />

persecution of those persons or collectives showing any kind of<br />

opposition to oil industry activity or the conditions in which these<br />

activities are carried out. This persecution is carried out through<br />

false accusations, death threats, kidnappings, physical aggression,

torture, and even murder, as has been widely documented before<br />

this Tribunal.<br />

• In particular, for the systematic and generalised persecution of<br />

trade unionists, as is the case of the leaders and rank and file<br />

members of the Unión Sindical Obrera, USO, in violation of labour<br />

rights recognised internationally and constitutionally.<br />

2. The Colombian Government:<br />

The Colombian State has not fulfilled its legal obligations with action and /<br />

or omission in at least the following most important aspects:<br />

• The State did not provide the necessary protection to political<br />

activists, social organisers, and trade unionists, who were victims of<br />

threats due to their work carried out peacefully and in favour of the<br />

achievement of human rights and respect for human dignity.<br />

• The State did not carry out the necessary investigations or impose<br />

the due punishment for the murders and other acts of grave<br />

violence perpetrated against persons and human groups, even<br />

though many of the authors could have been easily identified and in<br />

many cases were even members of the armed forces.<br />

• In the use of the public force in the repression of supposed<br />

insurgent groups, the State did not make the necessary distinction<br />

between combatant persons and groups and the peaceful civilian<br />

population, which was respectful of the current legal order.<br />

• In non-compliance with the obligations acquired in ILO Convention<br />

169 concerning the rights of the indigenous populations, by<br />

imposing the exploitation of natural resources within the lands of<br />

said communities without their consent.<br />

• In non-compliance with its obligation to prosecute crimes against<br />

humanity and in particular the violation of the right to effective<br />

legal recourse and the rights internationally recognised for the

victims of said crimes, due to the absence of a truly independent<br />

judicial power.<br />

3. The Governments of the States whose nationals possess significant capital<br />

in the previously mentioned enterprises:<br />

• For allowing said enterprises to not comply with international<br />

standards relating to human rights and the environment (which in<br />

their countries of origin they would be obliged to respect) as regards<br />

their economic activity in other countries, as in the case of<br />

Colombia.<br />

4. In particular, the government of the United States:<br />

• For defending a supposed right to intervene in any country in order<br />

to preserve US security interests, including access to oil resources,<br />

and decisively contributing to the extreme militarization<br />

surrounding oil exploitation in Colombia (through specific plans,<br />

human resources, training, and financing), as it has done in other<br />

parts of the world and with atrocious consequences for the civilian<br />

population.<br />

5. The Tribunal considers there to be reasonable grounds to classify a huge<br />

amount of specific acts of murder, massacre, torture, persecution, and the<br />

forced displacement of persons, as has been presented, as crimes against<br />

humanity, in as much as they have been committed in a systematic and<br />

generalised manner against a civilian population. In this context, the<br />

Tribunal wants to recognise the fact that, notwithstanding the previously<br />

stated and without exception, all persons, with or without the<br />

consideration of a State agency, also bear individual criminal<br />

responsibility for the crimes against humanity in which they may have<br />

participated as an author or accomplice. Furthermore, this responsibility

may be made effective through the Colombian court system or through<br />

other national tribunals operating with universal jurisdiction or, for crimes<br />

committed in Colombia after November 2, 2002, through the<br />

International Criminal Court.<br />

C<strong>ON</strong>CLUSI<strong>ON</strong>S<br />

Given the aforementioned reasons, appealing to the Algiers Declaration on the<br />

Rights of Peoples, considering proven the totality of accusations against all and<br />

everyone of the enterprises as well as the responsibility of the Colombian State,<br />

and with the conviction that the violation of their rights constitutes an attack on<br />

the common conscience of humanity and concerns all peoples, the Tribunal<br />

resolves:<br />

1. To send the accusations and evidence produced to the final deliberative<br />

hearing of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, session on Colombia.<br />

2. To disseminate the ruling to labour organisations, indigenous peoples, and<br />

urban and rural communities, who have suffered from the impact of the<br />

destructive actions of these transnationals, and to organisations in<br />

solidarity with the former, as well as to academic and student<br />

organisations, the Office of the Prosecutor General, the High Courts,<br />

Colombian Control Agencies, Alternative and Mass Media Outlets, the<br />

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the Inter-American Court<br />

of Human Rights, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human<br />

Rights, the United Nations Special Representative on Human Rights, the<br />

International Criminal Court, the Accused Enterprises, their corporate<br />

head offices, and the governments of their home states.<br />

3. To express the Tribunal’s solidarity and recognition of the victims’ pain.

4. To actively support the struggle for truth, justice, and comprehensive<br />

reparation, the reestablishment of the violated rights, and the guarantee<br />

these crimes will not be repeated.<br />

RECOMMENDATI<strong>ON</strong>S<br />

At the conclusion of this hearing, the delegates present for Permanent Peoples<br />

Tribunal –as well as the joint judges participating in the jury- express their utter<br />

admiration for the profoundness and courage of the work relating to cultural<br />

resistance and the defence of their dignity and right to a life with justice. In this<br />

regard, we appreciate the representatives and witnesses from the communities<br />

who have come before this hearing. These women and men have suffered so<br />

much –yet continue on the path for the construction of a future with peace and<br />

self-determination- not only deserve our solidarity, but also our equally<br />

important and coherent commitment to a just society. The following<br />

recommendations mean to be an expression of this commitment and one more<br />

way to accompany the communities we have come to know and will remain in our<br />

memory and actions.<br />

1. The jury calls upon intellectuals and members of social organisations from<br />

Latin America -and other parts of the world- to devise proposals for the<br />

regulatory legislation of transnational enterprises and the classification of<br />

their economic and environmental crimes within effective coercive<br />

frameworks. Moreover, the United Nations should be pressured to adopt<br />

this in order to safeguard the rights of peoples.<br />

2. The jury also calls upon the shareholders of the oil transnational<br />

enterprises in their countries of origin in order for them learn about the<br />

behaviour of their subsidiaries and subject them to an ethical control.<br />

3. The jury also calls upon the international community to be critical of the<br />

information produced daily on Colombia. In country where so many

atrocities have occurred as has been presented before this and previous<br />

hearings, it should be remembered official sources -or those allowing to<br />

silence these crimes- cannot be considered reliable.<br />

4. Likewise, as the jury, we call upon social organisations and movements<br />

from Latin America, which share the same problems and suffer from<br />

similar acts of aggression by oil enterprises so we may become ever more<br />

supportive of each other in speaking out and searching for solutions.<br />

5. We address the International Criminal Court so it does not further delay<br />

its decision to admit the case of Colombia, since the different hearings of<br />

the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal have proven the existence of several<br />

crimes against humanity.<br />

6. The Tribunal also considers it necessary and timely to urge Colombian<br />

lawyers, prosecutors, judges, and magistrates to take on an active role in<br />

the search for real justice, which is a prerequisite for peace. In this regard,<br />

we also consider it important to stress that, in addition to recognising the<br />

protection of an independent judicial power as indispensable in making<br />

effective human rights, the humanist concept of the right is becoming<br />

more universal. In modern jurisprudence, there is no place for the<br />

overcome legal positivism, which, conceiving right as a mere formalism,<br />

allowed the degradation of legal institutions and the perverse use of law as<br />

a shield for procedures contrary to ethics, for the use of violence to favour<br />

immoral privileges and give the appearance of legitimacy to acts of<br />

aggression against life, fundamental rights, and the dignity of the weakest<br />

and most fragile human beings. Humanism and right must complement<br />

each other and, in the practice, jurists are responsible for promoting this<br />

complementation.<br />

7. Lastly, we express our profound concern for the unprotected situation of<br />

those fighting for human rights in Colombia and in particular for those

who have appeared as witnesses in this and other PPT hearings. The jury<br />

considers all acts affecting the representatives and witnesses in these<br />

hearings to be the direct responsibility of the Colombian government.<br />

DALMO ABREU DALLARI (President)<br />

MARCELO FERREIRA<br />

ANT<strong>ON</strong>I PIGRAU<br />

NATIVIDAD ALMÁRCEGUI<br />

DOMINGO ANKWASH<br />

DEIRDRE GRISWOLD<br />

RALF HÄUSSLER-EBERT<br />

IV<strong>ON</strong>NE YÁÑEZ<br />

Presented in Bogotá D.C. on August 4, 2007.