urban regeneration and revitalization in the americas - Woodrow ...

urban regeneration and revitalization in the americas - Woodrow ...

urban regeneration and revitalization in the americas - Woodrow ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Comparative Urban Studies Project<br />

USAID<br />

FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE<br />

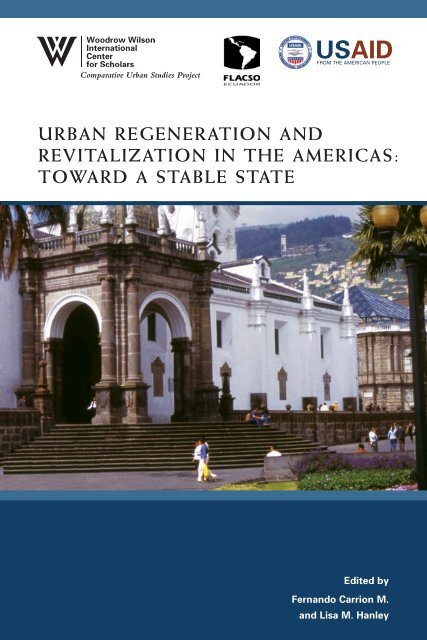

URBAN REGENERATION AND<br />

REVITALIZATION IN THE AMERICAS:<br />

TOWARD A STABLE STATE<br />

Edited by<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrion M.<br />

<strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley

URBAN REGENERATION<br />

AND REVITALIZATION<br />

IN THE AMERICAS:<br />

TOWARD A STABLE STATE<br />

Edited by<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

Comparative Urban Studies Project<br />

<strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson International Center for Scholars

Comparative Urban Studies Project<br />

Urban Regeneration <strong>and</strong> Revitalization<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Americas: Toward a Stable State<br />

Edited by<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

2007 <strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson International Center for Scholars, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C.<br />

www.wilsoncenter.org<br />

ISBN 1-933549-14-9<br />

Cover Photo: Blair A. Ruble

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS<br />

Lee H. Hamilton, President <strong>and</strong> Director<br />

BOARD OF TRUSTEES<br />

Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair<br />

David A. Metzner, Vice Chair<br />

Public Members: James H. Bill<strong>in</strong>gton, The Librarian of Congress; Bruce Cole, Chairman, National<br />

Endowment for <strong>the</strong> Humanities; Michael O. Leavitt, The Secretary, U.S. Department of Health <strong>and</strong><br />

Human Services; Tami Longaberger, designated appo<strong>in</strong>tee with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Federal Government;<br />

Condoleezza Rice, The Secretary, U.S. Department of State; Lawrence M. Small, The Secretary,<br />

Smithsonian Institution; Margaret Spell<strong>in</strong>gs, The Secretary, U.S. Department of Education; Allen<br />

We<strong>in</strong>ste<strong>in</strong>, Archivist of <strong>the</strong> United States Private Citizen Members: Rob<strong>in</strong> Cook, Bruce S. Gelb,<br />

S<strong>and</strong>er Gerber, Charles L. Glazer, Susan Hutchison, Ignacio E. Sanchez<br />

ABOUT THE CENTER<br />

The Center is <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g memorial of <strong>the</strong> United States of America to <strong>the</strong> nation’s twenty-eighth<br />

president, <strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson. Congress established <strong>the</strong> <strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson Center <strong>in</strong> 1968 as an<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>in</strong>stitute for advanced study, “symboliz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> fruitful relationship<br />

between <strong>the</strong> world of learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> world of public affairs.” The Center opened <strong>in</strong> 1970 under<br />

its own board of trustees.<br />

In all its activities <strong>the</strong> <strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson Center is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, supported<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ancially by annual appropriations from Congress, <strong>and</strong> by <strong>the</strong> contributions of foundations,<br />

corporations, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals. Conclusions or op<strong>in</strong>ions expressed <strong>in</strong> Center publications <strong>and</strong><br />

programs are those of <strong>the</strong> authors <strong>and</strong> speakers <strong>and</strong> do not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong> views of <strong>the</strong> Center<br />

staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any <strong>in</strong>dividuals or organizations that provide f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

support to <strong>the</strong> Center.

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

FORWARD<br />

Adrián Bonilla <strong>and</strong> Joseph S. Tulch<strong>in</strong><br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

PREFACE<br />

Urban Renovation <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Project<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

VII<br />

IX<br />

1<br />

PART I: HISTORIC CENTER, PUBLIC SPACE<br />

AND GOVERNMENT<br />

CHAPTER 1<br />

Pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Town Orange: The Role of Public<br />

Space <strong>in</strong> Streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g National States<br />

Blair A. Ruble<br />

CHAPTER 2<br />

The Historic Center as an Object of Desire<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M.<br />

CHAPTER 3<br />

The Relationship between State Stability <strong>and</strong> Urban<br />

Regeneration: The Contrast between Presidential <strong>and</strong><br />

Municipal Adm<strong>in</strong>istrations <strong>in</strong> Large Lat<strong>in</strong> American Cities<br />

Gabriel Murillo<br />

CHAPTER 4<br />

The New Hous<strong>in</strong>g Problem <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America<br />

Alfredo Rodríguez <strong>and</strong> Ana Sugranyes<br />

15<br />

19<br />

37<br />

51<br />

PART II. THE POLITICS OF URBAN IDENTITY:<br />

PATRIMONY AND MEMORY IN THE DEMOCRATIC SYSTEM<br />

CHAPTER 5<br />

Patrimony as a Discipl<strong>in</strong>ary Device <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Banalization of Memory: An Historic Read<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> Andes<br />

Eduardo K<strong>in</strong>gman Garcés <strong>and</strong> Ana María Goetschel<br />

67<br />

| v |

CHAPTER 6<br />

Cultural Strategies <strong>and</strong> Urban Renovation:<br />

The Experience of Barcelona<br />

Josep Subirós<br />

CHAPTER 7<br />

“More City,” Less Citizenship: Urban Renovation<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Annihilation of Public Space<br />

X. Andrade<br />

CHAPTER 8<br />

Cultural Heritage <strong>and</strong> Urban Identity:<br />

Shared Management for Economic Development<br />

Silvia Fajre<br />

CHAPTER 9<br />

Quito: The Challenges of a New Age<br />

Diego Carrión Mena<br />

79<br />

107<br />

143<br />

151<br />

PART III: THE TIES BETWEEN HISTORIC<br />

CENTERS AND SOCIAL PARTICIPATION<br />

CHAPTER 10<br />

The Center Divided<br />

Paulo Orm<strong>in</strong>do de Azevedo<br />

CHAPTER 11<br />

The Symbolic Consequences of Urban<br />

Revitalization: The Case of Quito, Ecuador<br />

Lisa M. Hanley <strong>and</strong> Meg Ru<strong>the</strong>nburg<br />

CHAPTER 12<br />

Participatory Government for <strong>the</strong><br />

Susta<strong>in</strong>ability of Historic Centers<br />

Mónica Moreira<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

159<br />

177<br />

203<br />

223<br />

| vi |

FORWARD<br />

In <strong>the</strong> mid-20th century, scholars <strong>and</strong> policymakers began <strong>the</strong> difficult task<br />

of reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>urban</strong> centers <strong>in</strong> a way that moved beyond <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

focus on architectural concepts <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> conservation of historical monuments.<br />

This new focus seeks to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>urban</strong> processes as essential to<br />

<strong>the</strong> construction of a stable state <strong>and</strong> a susta<strong>in</strong>able economy, based on a collective<br />

<strong>urban</strong> project that can contribute to economic development <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of culture. Here, <strong>the</strong> important issues related to <strong>the</strong> city are,<br />

on <strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong>, political stability, governance <strong>and</strong> economic susta<strong>in</strong>ability,<br />

<strong>and</strong>, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> creation of identities—all elements that<br />

should be explored <strong>in</strong> order to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>regeneration</strong> of an historic<br />

center with citizen participation.<br />

These topics, perspectives <strong>and</strong> debates animated <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational sem<strong>in</strong>ar<br />

“Urban Regeneration <strong>and</strong> Revitalization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Americas: Toward a Stable<br />

State,” which was organized by <strong>the</strong> Comparative Urban Studies Project of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson International Center for Scholars (WWICS) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Program on <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>the</strong> City at <strong>the</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> American School of Social<br />

Sciences, <strong>the</strong> Facultad Lat<strong>in</strong>oamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO), <strong>in</strong><br />

Ecuador. The sem<strong>in</strong>ar was held on December 16 <strong>and</strong> 17, 2004, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded<br />

<strong>the</strong> participation of architects, sociologists, anthropologists <strong>and</strong> economists,<br />

which allowed for a multidiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary analysis of <strong>urban</strong> development<br />

<strong>and</strong> its relationship to <strong>the</strong> construction of stable states.<br />

With this book, we hope to contribute new ideas for th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about cities<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>urban</strong> development, while recover<strong>in</strong>g historical processes <strong>and</strong> putt<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

human face on renovation so that it can be a platform for <strong>urban</strong> <strong>in</strong>novation.<br />

Adrián Bonilla<br />

Director<br />

FLACSO Ecuador<br />

Joseph S. Tulch<strong>in</strong><br />

Co-Director, Comparative Urban Studies Program<br />

<strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson International Center for Scholars<br />

| vii |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

The sem<strong>in</strong>ar <strong>and</strong> this publication were made possible with <strong>the</strong> support of<br />

<strong>the</strong> United States Agency for International Development’s Urban Programs<br />

Team with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bureau for Economic Growth <strong>and</strong> Trade. The editors<br />

would like to thank Blair A. Ruble <strong>and</strong> Joseph S. Tulch<strong>in</strong> for <strong>the</strong>ir support<br />

<strong>and</strong> academic direction. We are very grateful for <strong>the</strong>ir significant support.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, we want to recognize Karen Towers, Project Assistant at <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson Center, <strong>and</strong> Maria Eugenia Rodríguez at FLACSO, without<br />

whose coord<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> logistical support, this project would never<br />

have been possible.<br />

| ix |

PREFACE<br />

URBAN RENOVATION AND THE NATIONAL PROJECT<br />

FERNANDOCARRIÓN M. AND LISA M. HANLEY<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Comparative Urban Studies Project at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson International<br />

Center for Scholars <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Program on <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>the</strong> City,<br />

FLACSO-Ecuador organized an <strong>in</strong>ternational sem<strong>in</strong>ar on December 16 <strong>and</strong><br />

17, 2004 entitled “Urban Regeneration <strong>and</strong> Revitalization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Americas:<br />

Toward a Stable State.”<br />

There were 14 papers presented by academics, authorities <strong>and</strong> functionaries<br />

from a variety of different professions who focused <strong>the</strong>ir presentations on<br />

local, national <strong>and</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> American examples. A similarly diverse group of<br />

more than 80 people attended <strong>the</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g. These varied approaches to <strong>urban</strong><br />

questions greatly enriched both <strong>the</strong> presentations <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> discussions; <strong>in</strong>deed,<br />

<strong>the</strong> heterogeneity of <strong>the</strong> sem<strong>in</strong>ar was noted as a positive factor.<br />

Today, with <strong>the</strong> publication of this book, <strong>the</strong> results of <strong>the</strong> debates <strong>and</strong><br />

reflections are offered to a wider audience <strong>in</strong> order to share <strong>the</strong> important<br />

<strong>in</strong>formation presented at <strong>the</strong> sem<strong>in</strong>ar, <strong>and</strong> to promote <strong>the</strong> validity <strong>and</strong> importance<br />

of <strong>the</strong> proposal to contribute to <strong>the</strong> social, political <strong>and</strong> economic susta<strong>in</strong>ability<br />

of our countries through an <strong>urban</strong> project. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, with<br />

this publication we want to consolidate <strong>and</strong> share <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> idea beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong><br />

sem<strong>in</strong>ar—that a collective project on <strong>the</strong> city can contribute to <strong>the</strong> stability<br />

of our states <strong>and</strong> to <strong>the</strong> economic <strong>and</strong> social development of our countries.<br />

THE CITY AS PROTAGONIST<br />

The academic proposal of <strong>the</strong> sem<strong>in</strong>ar <strong>and</strong> publication is related to <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

hypo<strong>the</strong>sis: today <strong>urban</strong> processes are very significant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> constitution<br />

of stable states <strong>and</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>able economies. This is an important vision<br />

because until now <strong>urban</strong> issues have been understood more as a result of structural<br />

decisions made by public <strong>in</strong>stitutions than as contributions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

right to economic development, political stability <strong>and</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g a strong culture.<br />

| 1 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

A hypo<strong>the</strong>sis like this leads us to ask how an <strong>urban</strong> project can streng<strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutions. Even more directly related to <strong>the</strong> topic of <strong>the</strong> event, we ask<br />

how an <strong>urban</strong> renovation project can be an important component of a<br />

national project lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> construction of a legitimate <strong>and</strong> stable state.<br />

It is important to discuss <strong>the</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>urban</strong> renovation for public<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istration, governance, economic susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>and</strong> social development.<br />

Previously, <strong>urban</strong> renovation was thought of <strong>in</strong> its <strong>in</strong>verse relationship<br />

to public management <strong>and</strong> governance of <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong> area. It is more <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to underst<strong>and</strong> what <strong>the</strong> city can do for <strong>the</strong> economy, culture, society <strong>and</strong><br />

politics at <strong>the</strong> local, national <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational levels, based on a conception<br />

of <strong>the</strong> city as a solution <strong>and</strong> not as a problem or pathology.<br />

For example, local authorities ga<strong>in</strong> political legitimacy when <strong>the</strong>y focus<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>urban</strong> policies on city centers. This <strong>in</strong>creased legitimacy, <strong>in</strong> turn, allows<br />

for greater stability <strong>and</strong> governability. Here we have <strong>the</strong> illustrative cases of<br />

Quito <strong>and</strong> Bogota. The current mayor of Quito, Paco Moncayo, saw his<br />

popularity rise from <strong>the</strong> moment he advocated <strong>the</strong> relocation of <strong>in</strong>formal<br />

street commerce <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> historic center of Quito. In Bogota, former mayors<br />

Antanas Mockus <strong>and</strong> Enrique Peñalosa forwarded an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g notion of<br />

public space as <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple axis of <strong>the</strong> city. These <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>in</strong> city centers<br />

gave authorities legitimacy, streng<strong>the</strong>ned a pattern of <strong>urban</strong>ization <strong>and</strong><br />

promoted a broad sense of belong<strong>in</strong>g among city residents.<br />

We should not underestimate <strong>the</strong> economic importance of municipal<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> city centers. For example, <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> Puerto Madero <strong>in</strong><br />

Buenos Aires has helped generate economic activity <strong>and</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong><br />

city center. Growth <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> technological <strong>in</strong>frastructure of a neighborhood<br />

<strong>in</strong> Santiago, Chile has helped promote competition. In Guayaquil, <strong>the</strong><br />

“Malecón 2000” project has streng<strong>the</strong>ned <strong>the</strong> local <strong>and</strong> regional identities<br />

of <strong>the</strong> residents <strong>and</strong> produced an important economic zone. Similarly, a<br />

proposal for <strong>the</strong> development of tourism <strong>in</strong> Old Havana makes <strong>the</strong> historic<br />

center a platform for <strong>in</strong>novation with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sector, <strong>the</strong> city <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Cuban state.<br />

These k<strong>in</strong>ds of development show <strong>the</strong> importance of renovation projects<br />

<strong>in</strong> city centers that seek to contribute to <strong>and</strong> be part of national projects.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong>y demonstrate that such efforts must be based on a social<br />

consensus result<strong>in</strong>g from broad <strong>and</strong> varied forms of participation. This presupposes<br />

a collective project <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>re are public-private <strong>and</strong> publicpublic<br />

mechanisms of cooperation.<br />

| 2 |

Preface<br />

The sem<strong>in</strong>ar sought to reth<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>the</strong> city <strong>and</strong> <strong>urban</strong><br />

areas <strong>in</strong> terms of <strong>the</strong> market, <strong>the</strong> state, <strong>the</strong> private sector <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> public sector,<br />

on both <strong>the</strong> local <strong>and</strong> national levels. It is essential to address <strong>the</strong>se issues<br />

now that <strong>the</strong> market is more important to <strong>urban</strong> development than before,<br />

especially when state public policies control such development. This leads us<br />

to exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> new functions of <strong>the</strong> state related to <strong>the</strong> city <strong>and</strong> how <strong>the</strong> city<br />

can, at <strong>the</strong> same time, streng<strong>the</strong>n state <strong>in</strong>stitutions.<br />

This discussion is even more important <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of state reform<br />

processes through privatization <strong>and</strong> decentralization, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of<br />

globalization, which forces us to conceive of <strong>the</strong> city simultaneously <strong>in</strong> its<br />

supranationality <strong>and</strong> subnationality, 1 with <strong>the</strong> market play<strong>in</strong>g a significant<br />

role. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> city today is experienc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> denationalization of<br />

political dimensions (greater importance of local government), cultural<br />

dimensions (local symbols of identity) <strong>and</strong> economic dimensions (local development)<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of globalization.<br />

It could even be said that we are see<strong>in</strong>g a return to city-states because <strong>the</strong><br />

municipality—<strong>the</strong> level of government closest to civil society—becomes <strong>the</strong><br />

nucleus of social <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> because <strong>urban</strong> area becomes a political <strong>and</strong><br />

economic actor on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational scene (Sassen <strong>and</strong> Patel 1996). Today’s<br />

Lat<strong>in</strong> American municipality is highly competent, has greater economic<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> is more democratic. In this context, cities compete amongst<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves, <strong>the</strong>reby dissolv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> borders of national states.<br />

All of this forces us to reth<strong>in</strong>k <strong>the</strong> state, <strong>the</strong> public sector <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir relationship with <strong>the</strong> market from an <strong>urban</strong> perspective, <strong>and</strong> more<br />

specifically, from <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t of view of <strong>urban</strong> <strong>and</strong> historic centers. In o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

words, we must ask how we can construct a historic center project that contributes<br />

to a national project that, <strong>in</strong> turn, streng<strong>the</strong>ns state stability <strong>and</strong> economic<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ability. Historically this is possible <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America due to <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that <strong>the</strong> demographic transition has produced a decrease <strong>in</strong> rates of<br />

<strong>urban</strong>ization, which makes it possible to th<strong>in</strong>k about <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g city, about<br />

<strong>the</strong> return to <strong>the</strong> built city <strong>and</strong> about a city of quality over quantity. However,<br />

due to <strong>the</strong> process of globalization, <strong>the</strong> city is also positioned as a protagonist<br />

1. Follow<strong>in</strong>g Borja <strong>and</strong> Castells, “it could be said that national states are too small to control <strong>and</strong><br />

direct <strong>the</strong> new system’s global flows of power, wealth, <strong>and</strong> technology <strong>and</strong> too big to represent<br />

<strong>the</strong> plurality of <strong>the</strong> society’s <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>and</strong> cultural identities, <strong>the</strong>refore los<strong>in</strong>g legitimacy at once<br />

as representative <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong> as efficient organziations” (1998: 18).<br />

| 3 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

<strong>in</strong> a global, <strong>urban</strong> network. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, today more than ever a policy on<br />

<strong>urban</strong> <strong>and</strong> historic centers should be part of a national project.<br />

THE CITY AS A COMPONENT OF STABILITY AND SUSTAINABILITY<br />

In <strong>the</strong> last half century <strong>the</strong>re has been a rapid <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong> population<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> number of cities <strong>in</strong> all <strong>the</strong> countries of Lat<strong>in</strong> America, to <strong>the</strong><br />

extent that <strong>the</strong> region is primarily <strong>urban</strong>. In 1950, 41 percent of <strong>the</strong> population<br />

lived <strong>in</strong> cities; it was estimated that for <strong>the</strong> year 2000 it would be 77<br />

percent (Lates 2001). This means that <strong>the</strong> percentage of <strong>the</strong> population concentrated<br />

<strong>in</strong> cities practically doubled <strong>in</strong> half a century <strong>and</strong> that, at <strong>the</strong> same<br />

time, <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong> region’s population lives an <strong>urban</strong> lifestyle.<br />

Currently, more than 300 million people live <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> areas.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong> universe of Lat<strong>in</strong> America is characterized by<br />

hav<strong>in</strong>g two cities with more than 15 million <strong>in</strong>habitants, 28 cities with more<br />

than a million <strong>in</strong>habitants, <strong>and</strong> 35 cities with more than 600,000 <strong>in</strong>habitants.<br />

This means that <strong>the</strong>re are 65 metropolitan areas <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America.<br />

This pattern of <strong>urban</strong>ization leads us to put forward two propositions that<br />

guide this chapter. First, <strong>the</strong> fact that population, economy <strong>and</strong> politics are concentrated<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> areas <strong>in</strong> a context of <strong>in</strong>ternationalization <strong>and</strong> localization, of<br />

globalization (Robertson 1992), makes us th<strong>in</strong>k that cities have become significant<br />

political actors. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, today global cities are a new world actor<br />

<strong>in</strong> addition to national states <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> world economy (Sassen <strong>and</strong> Patel 1996).<br />

In <strong>the</strong> context of globalization—with <strong>the</strong> open<strong>in</strong>g of economies <strong>and</strong> processes<br />

of decentralization tak<strong>in</strong>g place throughout <strong>the</strong> world—<strong>the</strong> functions <strong>and</strong><br />

weight of cities tend to be redef<strong>in</strong>ed, mak<strong>in</strong>g cities <strong>in</strong>to spaces of <strong>in</strong>tegration,<br />

belong<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> social representation. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, cities today are less of a<br />

problem <strong>and</strong> more of a solution <strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong>y contribute significantly to political<br />

stability, 2 <strong>the</strong> reduction of poverty 3 <strong>and</strong> economic susta<strong>in</strong>ability. 4<br />

2. The city is <strong>the</strong> political space (polis) where citizenry is constituted. After <strong>the</strong> decentralization of<br />

<strong>the</strong> state, municipalities have become <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> nucleus of representation, proximity to society,<br />

stability, <strong>and</strong> legitimacy.<br />

3. It is easier to change patterns of gender <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> ra<strong>the</strong>r than rural areas. It is more<br />

feasible to reduce poverty <strong>in</strong> cities through improvements <strong>in</strong> unsatisfied basic needs, employment,<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come.<br />

4. Supply <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> are concentrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> areas <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> city is <strong>the</strong> axis of <strong>the</strong> model of<br />

accumulation on a global scale.<br />

| 4 |

Preface<br />

Second, <strong>the</strong> built city <strong>and</strong> its dist<strong>in</strong>ct centers have acquired greater<br />

weight as a result of <strong>the</strong> demographic transition experienced <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region.<br />

There has been a significant reduction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> rates of <strong>urban</strong>ization as well as<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> growth rates of <strong>the</strong> largest cities (Villa 1994). The rate of <strong>urban</strong>ization<br />

for Lat<strong>in</strong> America was reduced from 4.6 <strong>in</strong> 1950, to 4.2 <strong>in</strong> 1960, to<br />

3.7 <strong>in</strong> 1970, to 2.6 <strong>in</strong> 1990, <strong>and</strong> to 2.3 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> year 2000 (Habitat 1996). It<br />

is estimated that for <strong>the</strong> year 2030, <strong>the</strong> rate of <strong>urban</strong>ization will be around<br />

one percent. This new demographic condition reduces <strong>the</strong> pressure for<br />

<strong>urban</strong> growth <strong>and</strong> redirects focus to <strong>urban</strong> centers. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, we move<br />

from a logic of centrifugal <strong>urban</strong>ization to a logic of centripetal <strong>urban</strong>ization,<br />

where center areas play an important role.<br />

As cities grow less than before, it is possible to beg<strong>in</strong> to th<strong>in</strong>k about <strong>the</strong><br />

quality—not just quantity—of <strong>urban</strong> areas. S<strong>in</strong>ce cities, now have new,<br />

more global functions, it is also possible to th<strong>in</strong>k that <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g city <strong>and</strong>,<br />

more precisely, <strong>the</strong> renovation of city centers, could become a platform for<br />

<strong>urban</strong> <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>and</strong> projects that contribute to economic <strong>and</strong> political<br />

stability at <strong>the</strong> national level.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cities of Lat<strong>in</strong> America <strong>the</strong>re are two related <strong>in</strong>tra<strong>urban</strong><br />

bottlenecks that complicate <strong>the</strong> chances of this occurr<strong>in</strong>g. One has to<br />

do with <strong>the</strong> symbolic universe conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> <strong>and</strong> historic centers,<br />

which are currently subject to permanent social, economic <strong>and</strong> cultural<br />

deterioration. This erosion of memory damages <strong>the</strong> population’s feel<strong>in</strong>gs of<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegration, representation <strong>and</strong> belong<strong>in</strong>g beyond <strong>the</strong> space that conta<strong>in</strong>s<br />

<strong>the</strong>m (supra-spatiality) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> time <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>y were produced (history).<br />

In addition, <strong>the</strong> center, as a public space, suffers due to <strong>the</strong> weight of <strong>the</strong><br />

market <strong>and</strong> <strong>urban</strong> fragmentation, which become an impediment to <strong>urban</strong><br />

development, social <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> a strong citizenry. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong><br />

deterioration of symbolic patrimony <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> erosion of mechanisms of <strong>in</strong>tegration<br />

contribute to factors of social <strong>in</strong>stability.<br />

In addition, poverty has become a typically <strong>urban</strong> problem as <strong>the</strong> number<br />

of poor <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> American cities has <strong>in</strong>creased. At <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> 1990s,<br />

61.7 percent of poor people lived <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> areas while <strong>in</strong> 1970 it was 36.9<br />

percent, which means that <strong>the</strong>re has been an accelerated process of <strong>urban</strong>ization<br />

of poverty. Currently, <strong>the</strong>re are more than 130 million poor people<br />

liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America’s cities. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to CEPAL (2001), 37 percent of<br />

<strong>urban</strong> <strong>in</strong>habitants are poor <strong>and</strong> 12 percent are <strong>in</strong>digent. This k<strong>in</strong>d of<br />

poverty has several effects. First, it significantly reduces <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal mar-<br />

| 5 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

ket. Second, it degrades historic heritage because of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensive use of historic<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure. Lastly, cities of poor people make <strong>the</strong> cities poor.<br />

Ultimately, <strong>the</strong> concentration of <strong>urban</strong> poverty is a source of political <strong>and</strong><br />

economic <strong>in</strong>stability.<br />

In Lat<strong>in</strong> American cities, poverty tends to predom<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> two geographic<br />

areas—<strong>the</strong> center <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> periphery. 5 In both areas, <strong>the</strong>re is a high <strong>in</strong>tensity<br />

of use of historic <strong>in</strong>frastructure, which leads to a decreased quality of life<br />

of those liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>re, creat<strong>in</strong>g a vicious circle, 6 where <strong>the</strong> deterioration of<br />

both <strong>the</strong> natural <strong>and</strong> built <strong>urban</strong> environment becomes <strong>the</strong> cause <strong>and</strong> effect<br />

of <strong>the</strong> existence of poverty <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> population. The growth <strong>in</strong> density <strong>and</strong><br />

overcrowd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> city centers is evidence of this phenomenon because it leads<br />

to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensive use of space. The logic of <strong>the</strong> slum leads to <strong>the</strong> destructive<br />

use of historical heritage <strong>in</strong> city centers. Therefore, central areas of <strong>the</strong> region<br />

have attracted high concentrations of poverty, <strong>and</strong> degradation of <strong>the</strong> city<br />

center has become an impediment to economic development <strong>and</strong> a bottleneck<br />

for social <strong>in</strong>tegration.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, centers have <strong>the</strong> opportunity to overcome <strong>the</strong>se limitations<br />

through <strong>urban</strong> renovation, as long as <strong>the</strong> center is understood as a public<br />

space that determ<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> way of life for local society (<strong>in</strong>tegration, belong<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> representation) <strong>and</strong> a way of organiz<strong>in</strong>g a territory (<strong>urban</strong> structure),<br />

<strong>in</strong>scribed <strong>in</strong> larger <strong>urban</strong> projects that are part of a national proposal. This<br />

k<strong>in</strong>d of approach must focus on historic value (economic, political <strong>and</strong> cultural)<br />

<strong>and</strong> not on conservation.<br />

Renovation can also foster economic growth <strong>and</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>urban</strong> development.<br />

This allows popular sectors to be able to benefit from economic growth<br />

through job creation <strong>and</strong> direct or <strong>in</strong>direct salary <strong>in</strong>creases. In this way, <strong>the</strong><br />

improvement <strong>in</strong> quality of life occurs through social mobility <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> formation<br />

of social capital with networks, solid <strong>in</strong>stitutions <strong>and</strong> social cohesion.<br />

5. “Households <strong>in</strong> neighborhoods <strong>and</strong> consolidated hous<strong>in</strong>g where jobs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come—formal as<br />

well as <strong>in</strong>formal—are qualified as poor. This expression of <strong>urban</strong> poverty has <strong>in</strong>creased significantly<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cities of <strong>the</strong> region. We f<strong>in</strong>d it, on one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> central <strong>and</strong> peri-central neighborhoods<br />

<strong>in</strong> decay <strong>and</strong> stagnantion <strong>and</strong>, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> low-quality residential complexes<br />

which were built to house <strong>the</strong> poorest of <strong>the</strong> poor. Because of <strong>the</strong>ir vulnerability to economic<br />

fluctuations <strong>and</strong> fluctuations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> job market, <strong>the</strong>se families demonstrate today, <strong>in</strong> many<br />

cases, impoverishment associated with <strong>the</strong>ir residential location, <strong>the</strong> deterioration of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ability to afford formal hous<strong>in</strong>g” (MacDonald 2003).<br />

6. “Recent studies (PNUD/CEPAL 1999) demonstrate with data from Montevideo that <strong>the</strong><br />

social level of <strong>the</strong> sector or neighborhood has its own effects on student advancement <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>activity of youth, even after controll<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> educational climate of <strong>the</strong> home” (Arriagada<br />

2000: 17).<br />

| 6 |

Preface<br />

THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK<br />

The book is organized <strong>in</strong>to three parts. The first part, “Historic Centers,<br />

Public Space <strong>and</strong> Government,” discusses <strong>the</strong> existence of heterogeneous,<br />

fragmented cities with a diversity of spaces hav<strong>in</strong>g explicit functions that<br />

end up prefigur<strong>in</strong>g poli-centered <strong>urban</strong> areas, on <strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong>, on <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r, centers <strong>and</strong> peripheries related <strong>in</strong> a complex way. The equilibrium<br />

between historic <strong>and</strong> modern centers <strong>and</strong> peripheries is essential. This equilibrium<br />

will ensure that <strong>the</strong> renovation of <strong>the</strong> center does not produce an<br />

exodus of <strong>the</strong> population that will exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> degrade <strong>the</strong> peripheries or a<br />

periphery with no <strong>in</strong>frastructure or patrimony. If <strong>the</strong> city is fragmented or<br />

split, its centers <strong>and</strong> peripheries are too. For this reason, <strong>urban</strong>ism should<br />

be understood as a democratic strategy to revitalize <strong>the</strong> center, where poverty<br />

<strong>and</strong> degradation have historically been concentrated, <strong>and</strong> produce central<br />

services <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> periphery. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> fragmented<br />

city must be stitched toge<strong>the</strong>r through a process of social <strong>in</strong>tegration.<br />

In his open<strong>in</strong>g remarks at <strong>the</strong> sem<strong>in</strong>ar, Blair A. Ruble, Co-Director of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Comparative Urban Studies Project at <strong>the</strong> Wilson Center, reflected on<br />

<strong>the</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g of public space <strong>in</strong> streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g national states. In this volume,<br />

Ruble exp<strong>and</strong>s on <strong>the</strong>se remarks us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> case of <strong>the</strong> plaza—or maydan—<strong>in</strong><br />

Ukra<strong>in</strong>e, which became <strong>the</strong> salvation of democratic values <strong>in</strong> that<br />

country recently.<br />

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión, Coord<strong>in</strong>ator of <strong>the</strong> Program on <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>the</strong> City<br />

at FLACSO, discusses “The Historic Center as an Object of Desire” <strong>in</strong><br />

chapter 2, where he develops several hypo<strong>the</strong>ses regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> relationship<br />

between <strong>the</strong> historic center, public space, <strong>and</strong> large <strong>urban</strong> projects, work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

from <strong>the</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> historic center is <strong>the</strong> public space par excellence,<br />

<strong>and</strong>, for that reason, it is an articulat<strong>in</strong>g element of <strong>the</strong> city. This proposal<br />

is developed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> optimistic context of <strong>the</strong> city as a solution <strong>and</strong><br />

considers <strong>the</strong> historic center as an object of desire. Carrión dist<strong>in</strong>guishes <strong>the</strong><br />

model of <strong>the</strong> future city that symbolizes public space as s place for civic<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>in</strong> a way that elevates <strong>the</strong> role of space to one of symbolic centrality<br />

<strong>and</strong> heterogeneity.<br />

In his chapter, “The Relationship between State Stability <strong>and</strong> Urban<br />

Regeneration: The Contrast between Presidential <strong>and</strong> Municipal<br />

Adm<strong>in</strong>istrations <strong>in</strong> Large Lat<strong>in</strong> American Cities,” Gabriel Murillo, from<br />

<strong>the</strong> University of <strong>the</strong> Andes <strong>in</strong> Bogota, Colombia, posits <strong>the</strong>re is an <strong>in</strong>terdependent<br />

relationship between <strong>the</strong> government of large cities <strong>and</strong> state<br />

| 7 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

political stability. There is no doubt that successful management <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

municipal government of a large city can contribute to national political<br />

stability. To fur<strong>the</strong>r his po<strong>in</strong>t, he analyzes <strong>the</strong> case of Bogota <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context<br />

of <strong>urban</strong> primacy <strong>and</strong> national macro-economic limitations. The public<br />

policies of <strong>the</strong> last five adm<strong>in</strong>istrations of <strong>the</strong> city of Bogota serve to show<br />

<strong>the</strong> logic of <strong>in</strong>terdependency between good local adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>and</strong> state<br />

political stability.<br />

In chapter 4, Alfredo Rodríguez, SUR Corporación de Estudios Sociales y<br />

Educación, <strong>and</strong> Ana Sugranyes, Habitat Internacional Coalition (HIC), call<br />

attention to a new hous<strong>in</strong>g problem—not people without hous<strong>in</strong>g, as was <strong>the</strong><br />

situation 20 years ago, but ra<strong>the</strong>r people liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> subst<strong>and</strong>ard hous<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

may negatively impact <strong>the</strong> city. Rodríguez <strong>and</strong> Sugranyes challenge Chilean<br />

hous<strong>in</strong>g policy, considered a successful model for f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g that has sparked<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest throughout <strong>the</strong> region, to <strong>the</strong> extent that some governments are <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ately<br />

copy<strong>in</strong>g it without <strong>the</strong> benefit of analysis. The reality of <strong>the</strong> situation<br />

<strong>in</strong> Santiago shows that successful hous<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g policies can create<br />

new <strong>urban</strong> problems <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> absence of comprehensive hous<strong>in</strong>g policy.<br />

The second part of <strong>the</strong> book, “The Politics of Urban Identity: Patrimony<br />

<strong>and</strong> Memory <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Democratic System,” refers to <strong>the</strong> relationship of history<br />

(memory) <strong>and</strong> culture (identity), which should lead to a streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of democracy, <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>and</strong> social appropriation of <strong>the</strong> symbolic<br />

powers as well as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> socialization of patrimony. The axis of <strong>the</strong> debate<br />

proposed is focused on <strong>the</strong> relationship between history <strong>and</strong> patrimony <strong>and</strong><br />

between public policies of <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>and</strong> conservation. What becomes<br />

clear is that <strong>the</strong>re are different notions of heritage <strong>and</strong> patrimony. Indeed,<br />

patrimony is a cont<strong>in</strong>ual creation that is constantly be<strong>in</strong>g re<strong>in</strong>vented; <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is no one memory but ra<strong>the</strong>r a proliferation of memories.<br />

In chapter 5, “Patrimony as a Discipl<strong>in</strong>ary Device <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Banalization<br />

of Memory: An Historic Read<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> Andes,” Eduardo K<strong>in</strong>gman<br />

Garcés <strong>and</strong> Ana María Goetschel, FLACSO Ecuador, seek to recuperate <strong>the</strong><br />

historical character of <strong>the</strong> patrimony. They try to show <strong>the</strong> arbitrary nature<br />

of <strong>the</strong> notion of memory forwarded by policies of renovation <strong>and</strong> propose,<br />

at <strong>the</strong> same time, that <strong>the</strong> idea of patrimony leads to loss <strong>in</strong>stead of re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

historical mean<strong>in</strong>g. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong>y claim that <strong>the</strong> political<br />

dimension of patrimony is ignored; it is presented as someth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>herent<br />

<strong>and</strong> natural or else def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> a technical, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> this sense, neutral, way<br />

with no political context.<br />

| 8 |

Preface<br />

Josep Subirós, GAO, Idees i Proyectes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Accademia di<br />

Architectura Mendrisio, <strong>in</strong> chapter 6, reflects upon “Cultural Strategies <strong>and</strong><br />

Urban Renovation: The Experience of Barcelona.” He argues that <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong><br />

renovation projects undertaken <strong>in</strong> Barcelona do not respond as much to<br />

<strong>urban</strong> conceptions as to political strategies of re<strong>in</strong>vention, normalization,<br />

<strong>and</strong> democratic consolidation after three years of civil war <strong>and</strong> 36 years of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Franco dictatorship. An important characteristic of <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong> renovation<br />

that took place <strong>in</strong> Barcelona between 1979 <strong>and</strong> 1997 is <strong>the</strong> marriage<br />

of <strong>urban</strong> <strong>and</strong> civic concerns, <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>urban</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g as an <strong>in</strong>strument of<br />

civility, as a tool with which to contribute to <strong>the</strong> construction of a certa<strong>in</strong><br />

civic identity <strong>and</strong> new forms of br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g toge<strong>the</strong>r an <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ite variety of<br />

groups, <strong>in</strong>terests, attitudes, values, <strong>and</strong> memories <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> a large city. In<br />

this chapter, he addresses <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong> renovation process <strong>in</strong> Barcelona <strong>in</strong><br />

terms of <strong>the</strong> political <strong>and</strong> cultural dimensions of <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> architectonic <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>urban</strong> operations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> period analyzed <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir connection with <strong>the</strong> general<br />

process of reestablish<strong>in</strong>g democracy <strong>in</strong> Spa<strong>in</strong> after <strong>the</strong> death of Franco.<br />

In chapter 7, “‘More City,’ Less Citizenship: Urban Renovation <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Anihilation of Public Space,” X. Andrade, New School University, draws<br />

upon ethnographic research conducted between 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2004 to analyze<br />

<strong>the</strong> “<strong>urban</strong> renewal” of Guayaquil. He uses two case studies to make his<br />

argument. The first addresses <strong>urban</strong> reforms <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> city’s center that lead to<br />

a strictly discipl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> privatized public space. The second case study is<br />

related to a case of social hysteria about gang violence <strong>and</strong> provides a clear<br />

example of <strong>urban</strong> polarization <strong>and</strong> its expression <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> construction of a<br />

market of fear. In <strong>the</strong> background, <strong>the</strong> municipality’s “More Security” plan<br />

promotes <strong>the</strong> privatization of public space by conced<strong>in</strong>g polic<strong>in</strong>g control of<br />

<strong>the</strong> streets to private security companies. This chapter describes what can<br />

happen when communities close <strong>the</strong>mselves off <strong>and</strong> limit <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>r sectors of society.<br />

Silvia Fajre, Government of Buenos Aires, discusses “Cultural Heritage<br />

<strong>and</strong> Urban Identity: Shared Management for Economic Development” <strong>in</strong><br />

chapter 8. The chapter beg<strong>in</strong>s with a discussion of <strong>the</strong> concept of cultural heritage<br />

as be<strong>in</strong>g charged with content by <strong>the</strong> community. Therefore, patrimony<br />

requires a community-based def<strong>in</strong>ition not a purely technical one. Beyond<br />

that, it is important to underst<strong>and</strong> cultural heritage as an economic value that<br />

generates resources <strong>and</strong> employment <strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong>refore, contributes to susta<strong>in</strong>ability.<br />

Policies concern<strong>in</strong>g cultural heritage should support <strong>the</strong> supply of cul-<br />

| 9 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

tural events <strong>and</strong> assets, which, <strong>in</strong> turn, <strong>in</strong>crease social capital <strong>and</strong> make patrimony<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> framework of <strong>the</strong> market economy.<br />

In chapter 9, Diego Carrión Mena, Municipality of <strong>the</strong> Metropolitan<br />

District of Quito, reflects on “Quito: The Challenges of a New Age.”<br />

Carrión outl<strong>in</strong>es a series of projects for <strong>the</strong> city <strong>and</strong> notes <strong>the</strong> importance of<br />

convok<strong>in</strong>g citizen participation <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se plans. He also discusses<br />

<strong>the</strong> challenges fac<strong>in</strong>g Quito—<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r cities—<strong>in</strong> terms of coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> carry<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>urban</strong> projects that lead to more efficient, democratic,<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusive cities.<br />

The third part, “The Ties between Historic Centers <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Participation,” leads us directly to <strong>the</strong> topic of <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

space <strong>and</strong> power, where historic centers become disputed territories where<br />

some actors dom<strong>in</strong>ate o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>and</strong> where <strong>the</strong> image of power is permanently<br />

present. In sum, it could be said that power is not expressed <strong>in</strong> just one center,<br />

just as <strong>the</strong>re is not only one power <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> center.<br />

In his chapter, “The Center Divided,” Paulo Orm<strong>in</strong>do de Azevedo,<br />

Universidade Federal da Bahía, develops <strong>the</strong> idea of <strong>the</strong> divided city that<br />

Milton Santos <strong>and</strong> Aníbal Quijano have discussed. In historic centers <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is a predom<strong>in</strong>antly poor population <strong>and</strong> a series of important monuments.<br />

The importance of this center is disputed by <strong>the</strong> central bus<strong>in</strong>ess district,<br />

where <strong>the</strong> most dynamic activities of <strong>the</strong> city are located. In this way, <strong>the</strong><br />

center is divided <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> city itself is a series of fragments.<br />

In chapter 11, Lisa M. Hanley <strong>and</strong> Meg Ru<strong>the</strong>nburg, <strong>Woodrow</strong> Wilson<br />

Center, <strong>in</strong>vestigate <strong>the</strong> “The Symbolic Consequences of Urban Revitalization:<br />

The Case of Quito,” <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>y take a historical approach to <strong>the</strong> policies<br />

developed s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> city was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO to<br />

<strong>the</strong> present day, try<strong>in</strong>g to evaluate <strong>the</strong> impacts of such policies on <strong>the</strong> population<br />

<strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> city. The authors suggest that with <strong>the</strong> growth of <strong>the</strong> city <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 1970s due to <strong>the</strong> oil boom, <strong>the</strong>re was a significant deterioration of <strong>the</strong><br />

center, which is only beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g to be reversed now. They focus on <strong>the</strong> process<br />

of formalization of <strong>in</strong>formal street commerce <strong>and</strong> how it has achieved important<br />

results <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r areas, such as citizen security, transportation, municipal<br />

resources, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> legitimacy of authority. The authors conclude by not<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporation of public participation <strong>in</strong> local governance could provide<br />

a certa<strong>in</strong> level of local <strong>and</strong> national stability.<br />

Mónica Moreira, White March for Security <strong>and</strong> Life Foundation, reflects<br />

on “Participatory Government for <strong>the</strong> Susta<strong>in</strong>ability of Historic Centers” <strong>in</strong><br />

| 10 |

Preface<br />

chapter 12. She bases her study on <strong>the</strong> case of Quito <strong>and</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts out <strong>the</strong> particularities<br />

<strong>and</strong> difficulties of participation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> historic center. For example,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a great diversity of actors or subjects, some from <strong>the</strong> historic center<br />

itself <strong>and</strong> some from outside, each with its own <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

expressions. She discusses different forms of participation <strong>and</strong> concludes with<br />

a series of important recommendations.<br />

Despite at least 50 years of <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> American historic<br />

centers, <strong>the</strong>se centers cont<strong>in</strong>ue to have concentrations of poverty. When<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are not high levels of poverty, it has been due to <strong>the</strong> expulsion of <strong>the</strong><br />

resident population through processes of residential <strong>and</strong> commercial gentrification.<br />

All of this is based on a conservationist discourse that tends to<br />

reify heritage <strong>and</strong> memory.<br />

It is time to put a human face on <strong>urban</strong> renovation, so that it can be a<br />

platform for <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> city, a mechanism for <strong>the</strong> re<strong>in</strong>vention of local<br />

government, <strong>and</strong> a contribution toward social <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> economic<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ability.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Arraigada, Camilo. 2000. Pobreza en América Lat<strong>in</strong>a: nuevos escenarios y<br />

desafíos de política para el hábitat <strong>urban</strong>o. Santiago: Ed. CEPAL.<br />

Borja, Jordi <strong>and</strong> Manuel Castells. 1998. Local y Global. Madrid: Ed.<br />

Taurus, Madrid.<br />

Carrión, Fern<strong>and</strong>o, ed. 2001. Centros Históricos de América Lat<strong>in</strong>a y El<br />

Caribe. Quito: Ed. UNESCO-BID-SIRCHAL.<br />

Castells, Manuel. 1999. La era de la <strong>in</strong>formación. Barcelona: Ed. Siglo XXI<br />

CEPAL. 2001. Panorama social. Santiago: UNESCO Publish<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

United Nations.<br />

HABITAT. 1996. La pobreza <strong>urban</strong>a: un reto mundial. La declaración de<br />

Recife. Recife: Editorial Habitat.<br />

Lates, Alfredo. 2001. “Población <strong>urban</strong>a y <strong>urban</strong>ización en América<br />

Lat<strong>in</strong>a” en Carrión, Fern<strong>and</strong>o, La ciudad construida. Quito: Ed. FLACSO.<br />

MacDonald, Joan. 2003. Expresión de la pobreza en la ciudad. Mimeo.<br />

Santiago: CEPAL.<br />

Quijano, Aníbal. 1970. Redef<strong>in</strong>ición de la dependencia y marg<strong>in</strong>alidad en<br />

América Lat<strong>in</strong>a. Santiago: Facultad de Ciencias Económicas,<br />

Universidad de Chile.<br />

| 11 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M. <strong>and</strong> Lisa M. Hanley<br />

Robertson, Rol<strong>and</strong>. 1992. Globalization: Social Theory <strong>and</strong> Global Culture.<br />

London: Sage.<br />

Santos, Milton. 1967. O espaço dividido: os dois circuitos da economia<br />

<strong>urban</strong>a dos países sub-desenvolvidos. Rio de Janeiro: Liviraria<br />

Francisco Alves .<br />

Sassen, Saskia <strong>and</strong> Sujata Patel. 1996. Las ciudades de hoy: una nueva<br />

frontera. Era <strong>urban</strong>a, Vol 4, Número 1. Quito: Ed. PGU, Quito.<br />

Villa, Miguel <strong>and</strong> Jorge Martínez. 1994 “Las fuentes de la <strong>urban</strong>ización y<br />

del crecimiento <strong>urban</strong>o de la población de América Lat<strong>in</strong>a” <strong>in</strong> La Era<br />

Urbana, Vol. 2, No. 3. Quito: Ed. PGU.<br />

| 12 |

PART I: HISTORIC CENTERS, PUBLIC<br />

SPACE, AND GOVERNMENT

CHAPTER 1<br />

PAINTING THE TOWN ORANGE:<br />

THE ROLE OF PUBLIC SPACE IN<br />

STRENGTHENING NATIONAL STATES<br />

BLAIR A. RUBLE<br />

Thous<strong>and</strong>s of protestors took up residence on Kyiv’s central Maydan<br />

Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), <strong>and</strong> premier street, <strong>the</strong> Khreshchtyk,<br />

throughout November <strong>and</strong> December 2004, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>to January 2005. Their<br />

numbers swelled <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> tens <strong>and</strong> even hundreds of thous<strong>and</strong>s at times,<br />

perhaps surpass<strong>in</strong>g one-<strong>and</strong>-a-half million at pivotal moments over <strong>the</strong><br />

course of <strong>the</strong>se cold w<strong>in</strong>ter weeks. The demonstrations <strong>and</strong> negotiations<br />

unfold<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> city’s streets <strong>and</strong> beh<strong>in</strong>d closed doors followed massive<br />

election fraud <strong>in</strong> a November 21, 2004 presidential runoff. They would lead<br />

eventually to <strong>the</strong> annulment of <strong>the</strong> disputed election results <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ratification<br />

of far-reach<strong>in</strong>g constitutional reforms. These events became known<br />

as Ukra<strong>in</strong>e’s “Orange Revolution.” The election campaign had reached full<br />

fury as summer came to an end, by which time 26 c<strong>and</strong>idates were registered<br />

officially to run for <strong>the</strong> post of president of Ukra<strong>in</strong>e. The contest narrowed<br />

quickly around two large oppos<strong>in</strong>g political positions represented by<br />

<strong>the</strong> c<strong>and</strong>idacies of Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister Viktor Yanukovich <strong>and</strong> former Prime<br />

M<strong>in</strong>ister Viktor Yushchenko. Both men emerged as symbols for deep philosophical<br />

divisions with<strong>in</strong> Ukra<strong>in</strong>e. Yanukovich, <strong>and</strong> his “party of power,”<br />

stood for a cont<strong>in</strong>uation of <strong>the</strong> status quo; Yushchenko, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>,<br />

stood for a more “modern” approach to governance <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> state<br />

served citizens who would <strong>the</strong>mselves become <strong>the</strong> primary autonomous<br />

actors with<strong>in</strong> society.<br />

Kyiv literally shaped events firstly by its physical form. The city’s ma<strong>in</strong><br />

street—<strong>the</strong> Khreshchatyk—was rebuilt as one of <strong>the</strong> Soviet Union’s premier<br />

examples of Stal<strong>in</strong>ist <strong>urban</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g follow<strong>in</strong>g its total destruction dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

World War II. The avenue arose refreshed by huge, florid examples of totalitarian<br />

architecture matched <strong>in</strong> scale <strong>and</strong> extent only <strong>in</strong> parts of Moscow<br />

<strong>and</strong> East Berl<strong>in</strong>. Approximately one-third of <strong>the</strong> way along its route from<br />

what was once Komsomol (Young Communist League) Square <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> east<br />

to Bessarabskaya Square <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> west, <strong>the</strong> Khreshchatyk explodes outwards<br />

| 15 |

Blair A. Ruble<br />

<strong>in</strong>to a large square to be used for appropriately gr<strong>and</strong> official Communist<br />

Party demonstrations. This square was renamed Maydan Nezalezhnosti, or<br />

Independence Square, follow<strong>in</strong>g 1991. Mayor Omelchenko sponsored <strong>the</strong><br />

construction of underground shopp<strong>in</strong>g malls along <strong>the</strong> Khreshatyk both at<br />

Maydan Nezalezhnosti <strong>and</strong> under Bessarabskaya Square. President<br />

Kuchma <strong>and</strong> Mayor Omelchenko oversaw a simultaneous tacky tart<strong>in</strong>g up<br />

of <strong>the</strong> above ground areas to mark <strong>the</strong> 10th anniversary of Ukra<strong>in</strong>ian<br />

Independence <strong>in</strong> 2001. Overtime, Omelchenko’s city government built a<br />

“temporary” stage for rock concerts that was outfitted with stadium-size television<br />

screens <strong>and</strong> sound systems. The mayor sponsored clos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

Khreshchatyk <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Maydan to vehicular traffic on Sundays, creat<strong>in</strong>g an<br />

enormous outdoor space for promenad<strong>in</strong>g. Kyvians adopted <strong>the</strong> entire area<br />

as <strong>the</strong>ir own, with upwards of half-a-million people stroll<strong>in</strong>g about, shopp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> listen<strong>in</strong>g to music on any given Sunday.<br />

The Maydan was a perfect location for such a central public space.<br />

Nestled <strong>in</strong> a small valley among various fragments of <strong>the</strong> overall city<br />

(Pechersk, “Old Kyiv,” Bessarabka, etc.), <strong>the</strong> Maydan exerts a central gravitational<br />

force, giv<strong>in</strong>g form <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition to Kyiv’s <strong>urban</strong> life. As many as<br />

a dozen streets flow down <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> Maydan <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Khreshchatyk from various<br />

angles. Nearly all of <strong>the</strong> city’s major <strong>in</strong>stitutions are located nearby.<br />

The Parliament (Verkhovna Rada), Presidential Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, St. Sophia’s<br />

Ca<strong>the</strong>dral, offices of <strong>the</strong> Central Election Commission, City Hall, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

headquarters build<strong>in</strong>g of Ukra<strong>in</strong>e’s trade unions are all with<strong>in</strong> a brisk fifteen<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ute walk of Omelchenko’s sound stage. Apartment houses first built for<br />

prom<strong>in</strong>ent members of <strong>the</strong> Soviet regime similarly are close by, many occupied<br />

with residents ready to cook a warm meal to feed demonstrators<br />

camped on <strong>the</strong>ir doorsteps. Connected to <strong>the</strong> entire city by several subway<br />

<strong>and</strong> major bus l<strong>in</strong>es, <strong>the</strong> Maydan had become <strong>the</strong> focal po<strong>in</strong>t for civic life<br />

well before demonstrators turned it orange. Protestors naturally headed<br />

straight for <strong>the</strong> Maydan on <strong>the</strong> night of November 21–22 as it appeared<br />

that someone was try<strong>in</strong>g to steal <strong>the</strong> country’s presidential election. The<br />

Orange Revolution represents a classic <strong>in</strong>stance <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> form <strong>and</strong> function<br />

of <strong>the</strong> physical <strong>urban</strong> space can determ<strong>in</strong>e a city’s history.<br />

The political city jo<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>the</strong> physical city <strong>in</strong> support of efforts to<br />

br<strong>in</strong>g Viktor Yushchenko to power. As noted above, <strong>the</strong> Kyiv City Council<br />

was among <strong>the</strong> first to reject <strong>the</strong> results of <strong>the</strong> November 21 presidential<br />

run-off be<strong>in</strong>g released by <strong>the</strong> Central Election Commission. Mayor<br />

| 16 |

Pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Town Orange<br />

Omelchenko immediately rejected <strong>the</strong> use of force to disperse <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

throngs of demonstrators <strong>and</strong> protestors. The mayor went fur<strong>the</strong>r, pay<strong>in</strong>g<br />

back Kuchma for <strong>the</strong> president’s various attempts to drive him from office,<br />

by literally keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lights on <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Maydan. City officials kept <strong>the</strong> subways<br />

<strong>and</strong> busses runn<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> sound stage volume turned up high, <strong>the</strong> enormous<br />

stadium-sized television screens switched on. City officials spurred<br />

on revolution merely by operat<strong>in</strong>g as if all were normal. Omelchenko chose,<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> end, to treat <strong>the</strong> presence of well over a million protestors as if it were<br />

just a particularly large turn out for <strong>the</strong> annual City Day celebrations held<br />

each fall. The city streets of a once totalitarian city better known for its<br />

Stal<strong>in</strong>ist architecture have become symbols of democratic national rebirth<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ukra<strong>in</strong>ian word for plaza, maydan, has now become synonymous<br />

with democracy.<br />

| 17 |

CHAPTER 2<br />

THE HISTORIC CENTER AS AN OBJECT OF DESIRE<br />

FERNANDO CARRIÓN M.<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

In this chapter, I present several hypo<strong>the</strong>ses about <strong>the</strong> relationship<br />

between historic centers, public space, <strong>and</strong> large <strong>urban</strong> projects, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> historic center is <strong>the</strong> public space par<br />

excellence. This proposal will be developed <strong>in</strong> an optimistic context<br />

that views <strong>the</strong> city as a solution <strong>and</strong> considers <strong>the</strong> historic center an<br />

object of desire. It is necessary to overcome <strong>the</strong> stigma <strong>and</strong> pessimism<br />

often associated with <strong>the</strong> city. This pessimism is two-fold. On one<br />

h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> city is often seen as a source of anomie <strong>and</strong> chaos expressed,<br />

for example, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> idea of a cement jungle. This neo-Malthusianist<br />

view of <strong>the</strong> city is of someth<strong>in</strong>g that creates violence <strong>and</strong> poverty. On<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> city has been periodically declared dead. 1 From<br />

<strong>the</strong>se negative conceptions of <strong>the</strong> city came <strong>the</strong> notion that <strong>the</strong><br />

process of rural to <strong>urban</strong> migration had to be stopped to halt <strong>the</strong><br />

growth of cities <strong>and</strong>, consequently, halt <strong>the</strong> growth of <strong>urban</strong> problems.<br />

However, we now see after a period of accelerated <strong>urban</strong>ization<br />

<strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America 2 that poverty is greatly reduced <strong>in</strong> cities. 3<br />

1. “Has <strong>the</strong> city died Now it is globalization that kills it. Before, it was <strong>the</strong> metropolization<br />

that developed with <strong>the</strong> Industrial Revolution. And before it was <strong>the</strong> baroque city,<br />

which extended outside medieval boundaries. Periodically, when historic change appears<br />

to accelerate <strong>and</strong> is perceptible <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> expansive forms of <strong>urban</strong> development, <strong>the</strong> death<br />

of <strong>the</strong> city is declared” (Borja 2003: 23).<br />

2. “Tak<strong>in</strong>g note of <strong>the</strong> high degree of <strong>urban</strong>ization reach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> region, <strong>the</strong> Regional<br />

Action Plan proposed <strong>the</strong> challenge of mak<strong>in</strong>g this characteristic an advantage, <strong>in</strong>stead<br />

of cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to consider it a problem as had been <strong>the</strong> usual discourse <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> previous<br />

decade” (Mac Donald <strong>and</strong> Simioni 1999: 7).<br />

3. “In all countries, poverty tends to be greater <strong>in</strong> rural areas than <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> areas, <strong>and</strong> it<br />

tends to be lesser <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> larger cities than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>termediate <strong>and</strong> small cities…. On <strong>the</strong><br />

contrary, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority of countries <strong>urban</strong> concentration has not been a negative factor,<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce it has allowed for access to goods <strong>and</strong> services to a greater measure than what<br />

prevailed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> time of rural dom<strong>in</strong>ance” (Jordan <strong>and</strong> Simioni 2002: 15).<br />

| 19 |

Fern<strong>and</strong>o Carrión M.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cities it is easier to change patterns of gender<br />

<strong>in</strong>equality than <strong>in</strong> rural areas (Arboleda 1999). 4<br />

A second po<strong>in</strong>t that guides this chapter is related to revalu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> built<br />

city <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> two types of city centers—<strong>the</strong> historic <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>urban</strong>. In<br />

some cases, <strong>the</strong> historic <strong>and</strong> <strong>urban</strong> centers are <strong>the</strong> same. This revalu<strong>in</strong>g<br />

has to do with two explicit determ<strong>in</strong>ants—<strong>the</strong> processes of globalization<br />

<strong>and</strong> demographic transition. In 1950, 41 percent of <strong>the</strong> population <strong>in</strong><br />

Lat<strong>in</strong> America lived <strong>in</strong> <strong>urban</strong> areas. Today, that percentage has almost<br />

doubled to 80 percent. This demographic transition also means that size<br />

of <strong>the</strong> population migrat<strong>in</strong>g to cities has significantly been reduced. In<br />

1950, it was 60 percent; today it is only 20 percent. This demographic<br />