You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

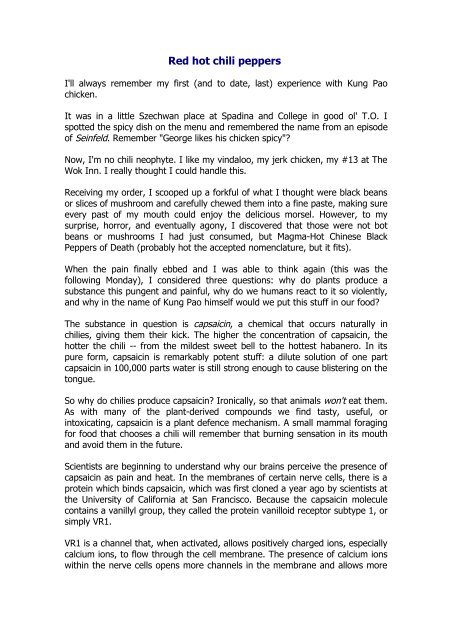

<strong>Red</strong> <strong>hot</strong> <strong>chili</strong> <strong>peppers</strong><br />

I'll always remember my first (and to date, last) experience with Kung Pao<br />

chicken.<br />

It was in a little Szechwan place at Spadina and College in good ol' T.O. I<br />

spotted the spicy dish on the menu and remembered the name from an episode<br />

of Seinfeld. Remember "George likes his chicken spicy"<br />

Now, I'm no <strong>chili</strong> neophyte. I like my vindaloo, my jerk chicken, my #13 at The<br />

Wok Inn. I really thought I could handle this.<br />

Receiving my order, I scooped up a forkful of what I thought were black beans<br />

or slices of mushroom and carefully chewed them into a fine paste, making sure<br />

every past of my mouth could enjoy the delicious morsel. However, to my<br />

surprise, horror, and eventually agony, I discovered that those were not bot<br />

beans or mushrooms I had just consumed, but Magma-Hot Chinese Black<br />

Peppers of Death (probably <strong>hot</strong> the accepted nomenclature, but it fits).<br />

When the pain finally ebbed and I was able to think again (this was the<br />

following Monday), I considered three questions: why do plants produce a<br />

substance this pungent and painful, why do we humans react to it so violently,<br />

and why in the name of Kung Pao himself would we put this stuff in our food<br />

The substance in question is capsaicin, a chemical that occurs naturally in<br />

<strong>chili</strong>es, giving them their kick. The higher the concentration of capsaicin, the<br />

<strong>hot</strong>ter the <strong>chili</strong> -- from the mildest sweet bell to the <strong>hot</strong>test habanero. In its<br />

pure form, capsaicin is remarkably potent stuff: a dilute solution of one part<br />

capsaicin in 100,000 parts water is still strong enough to cause blistering on the<br />

tongue.<br />

So why do <strong>chili</strong>es produce capsaicin Ironically, so that animals won't eat them.<br />

As with many of the plant-derived compounds we find tasty, useful, or<br />

intoxicating, capsaicin is a plant defence mechanism. A small mammal foraging<br />

for food that chooses a <strong>chili</strong> will remember that burning sensation in its mouth<br />

and avoid them in the future.<br />

Scientists are beginning to understand why our brains perceive the presence of<br />

capsaicin as pain and heat. In the membranes of certain nerve cells, there is a<br />

protein which binds capsaicin, which was first cloned a year ago by scientists at<br />

the University of California at San Francisco. Because the capsaicin molecule<br />

contains a vanillyl group, they called the protein vanilloid receptor subtype 1, or<br />

simply VR1.<br />

VR1 is a channel that, when activated, allows positively charged ions, especially<br />

calcium ions, to flow through the cell membrane. The presence of calcium ions<br />

within the nerve cells opens more channels in the membrane and allows more

calcium in, which, in turn opens still more channels. This positive feedback is<br />

the basis of the nerve impulse.<br />

So, when capsaicin is around, nerves fire. But, why does it feel <strong>hot</strong><br />

I recently spoke to Gerald Morris, Queen's professor and head of the<br />

department of biology. He explained that there is still more to learn about the<br />

relationship between capsaicin and the VR1 receptor. To explain, he drew an<br />

analogy between capsaicin and another group of compounds which have a<br />

remarkable effect on humans: drugs derived from opium, such as morphine and<br />

heroin, collectively called the opioids. "The obvious comparison is the opioids<br />

and the opioid receptors, where there are the drugs opium and its related<br />

compounds. When people looked in humans they found the endorphins."<br />

Endorphins are part of our natural pain suppression mechanism and are<br />

chemically similar to opium derivatives. Endorphins are the natural trigger, the<br />

endogenous ligand, for the opioid receptor, but opioid drugs will work too.<br />

But as Morris pointed out to me, "there is no known endogenous ligand for the<br />

capsaicin receptor." So, it seems that we react to a completely non-toxic<br />

compound, produced by certain plants -- with nothing chemically similar in our<br />

own bodies -- as if our gums are on fire. Something doesn't quite add up.<br />

"One idea," explained Morris, "is that this receptor is not only activated by<br />

capsaicin, it's [also] activated by heat." Indeed, the UCSF study showed that<br />

VR1 is sensitive to rapid increases in temperature, as well as to capsaicin. That<br />

would explain why spicy foods taste "<strong>hot</strong>" -- both capsaicin and heat trigger the<br />

same receptor.<br />

Incidentally, capsaicin doesn't just affect the tongue and lips. Any part of the<br />

body that has nerve endings is sensitive, including the entire skin surface, the<br />

length of the gut, and the eyes. Morris tells a story confirming that there are<br />

capsaicin receptors in our most delicate tissues. I won't recount the story here;<br />

let's just say that, for graduate students working with capsaicin, it is much more<br />

important to wash their hands before using the washroom than after.<br />

All of this still doesn't explain why we subject ourselves to suicide wings and<br />

prairie fires. There has been some suggestion that capsaicin and other spices<br />

have some preservative properties, which would explain why so much of the<br />

spicy fare originates in tropical countries where, until recently, no method of<br />

refrigeration was available. Morris, however, favours the explanation that we<br />

use spices because they enhance flavours. And it's not just humans who think<br />

so.<br />

"The was an animal study," Morris said, "where they gave rats plain food and...<br />

food which had quite a high dose of capsaicin in it. After a period [of a week],<br />

the rats were then given a choice. the ones that had had the spicy food --<br />

which was enough to cause them discomfort initially -- preferred it."

Certainly, capsaicin adds another dimension to an eating experience. Being<br />

odourless and tasteless, it stimulates parts of our mouths, and our brains, that<br />

blander food don't.<br />

Of course, no article on spicy food would be complete without the antidotes.<br />

What do you do if you've had too many Guatemalan Insanity Peppers<br />

You've probably heard that water will do more harm than good, and other than<br />

the cooling sensation of the water, it's true. Capsaicin isn't very soluble in<br />

water, so the best it can do is spread the heat around. Each spicy-food culture<br />

has its own remedy. The Thais suggest sugar and the Chinese prescribe rice.<br />

Carbohydrates do seem to absorb capsaicin or mask its effects. Indian<br />

restaurants offer a selection of yogurt-based drink and condiments to cool you<br />

down, and <strong>chili</strong> con carne and beer go very well together. Capsaicin is very<br />

soluble in both fats and alcohol.<br />

Theoretically, then, the best remedy for too many <strong>chili</strong>es would be a very rich,<br />

very strong white Russian, made with whole milk or heavy cream.<br />

I'll have to try that next time I dare to take on Kung Pao.<br />

John Bowman's mom doesn't like how all of his science articles end up<br />

mentioning booze.