The SAA Archaeological Record - Society for American Archaeology

The SAA Archaeological Record - Society for American Archaeology

The SAA Archaeological Record - Society for American Archaeology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ARTICLE<br />

DEVELOPMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY AND<br />

LONG-TERM PARTNERSHIPS WITH<br />

THE CHILEAN MAPUCHE<br />

Tom D. Dillehay and Jose Saavedra<br />

Tom D. Dillehay is Professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and José Saavedra is Professor at the Universidad ARCIS-Chile, Santiago, Chile.<br />

In recent years, archaeologists have engaged in much discussion<br />

and debate concerning the role that local community<br />

awareness and participation should have in archaeological<br />

research, particularly in remote indigenous areas where people<br />

do not always understand the objectives and activities of archaeology.<br />

Partnerships with these communities<br />

can promote archaeology and make<br />

people aware of the potential benefits of<br />

archaeological research. For the purpose<br />

of bringing more attention to this topic,<br />

we report here on more than three<br />

decades of archaeological and anthropological<br />

research that the first author and<br />

his colleagues have conducted with<br />

Mapuche communities in south-central<br />

Chile. This research has led to a productive<br />

working partnership, mutual respect<br />

and understanding, and the employment<br />

of archaeological research to foster community-level<br />

developmental projects.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mapuche are the most numerous of<br />

the indigenous peoples living in Chile at<br />

the present time. Numbering nearly<br />

700,000 persons, they represent almost<br />

three percent of the total population of the<br />

country. In the Araucania region of southcentral<br />

Chile, they constitute roughly 40<br />

percent of the total rural population. A<br />

much smaller number live in Argentina<br />

near the Andean border with Chile. Until<br />

the late 1800s, the Mapuche were independent<br />

people. For centuries, they had<br />

halted the Spanish conquest and kept<br />

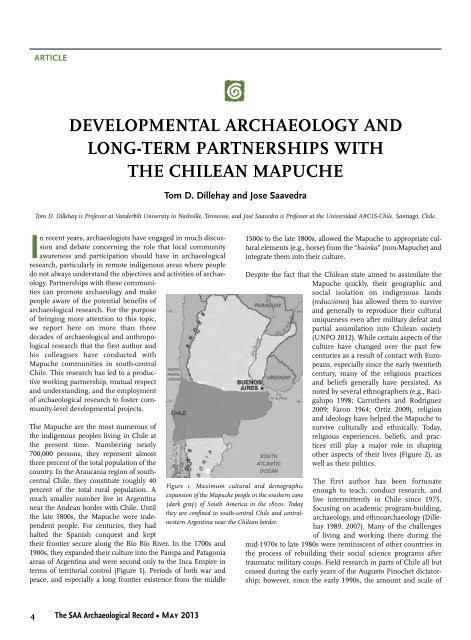

their frontier secure along the Bío Bío River. In the 1700s and<br />

1900s, they expanded their culture into the Pampa and Patagonia<br />

areas of Argentina and were second only to the Inca Empire in<br />

terms of territorial control (Figure 1). Periods of both war and<br />

peace, and especially a long frontier existence from the middle<br />

Figure 1. Maximum cultural and demographic<br />

expansion of the Mapuche people in the southern cone<br />

(dark gray) of South America in the 1800s. Today<br />

they are confined to south-central Chile and centralwestern<br />

Argentina near the Chilean border.<br />

1500s to the late 1800s, allowed the Mapuche to appropriate cultural<br />

elements (e.g., horse) from the “huinka” (non-Mapuche) and<br />

integrate them into their culture.<br />

Despite the fact that the Chilean state aimed to assimilate the<br />

Mapuche quickly, their geographic and<br />

social isolation on indigenous lands<br />

(reducciones) has allowed them to survive<br />

and generally to reproduce their cultural<br />

uniqueness even after military defeat and<br />

partial assimilation into Chilean society<br />

(UNPO 2012). While certain aspects of the<br />

culture have changed over the past few<br />

centuries as a result of contact with Europeans,<br />

especially since the early twentieth<br />

century, many of the religious practices<br />

and beliefs generally have persisted. As<br />

noted by several ethnographers (e.g., Bacigalupo<br />

1998; Carruthers and Rodriguez<br />

2009; Faron 1964; Ortiz 2009), religion<br />

and ideology have helped the Mapuche to<br />

survive culturally and ethnically. Today,<br />

religious experiences, beliefs, and practices<br />

still play a major role in shaping<br />

other aspects of their lives (Figure 2), as<br />

well as their politics.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first author has been <strong>for</strong>tunate<br />

enough to teach, conduct research, and<br />

live intermittently in Chile since 1975,<br />

focusing on academic program-building,<br />

archaeology, and ethnoarchaeology (Dillehay<br />

1989, 2007). Many of the challenges<br />

of living and working there during the<br />

mid-1970s to late 1980s were reminiscent of other countries in<br />

the process of rebuilding their social science programs after<br />

traumatic military coups. Field research in parts of Chile all but<br />

ceased during the early years of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship;<br />

however, since the early 1990s, the amount and scale of<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> <strong>SAA</strong> <strong>Archaeological</strong> <strong>Record</strong> • May 2013