Attorneys Working Toward the Tipping Point for Diversity - The Bar ...

Attorneys Working Toward the Tipping Point for Diversity - The Bar ...

Attorneys Working Toward the Tipping Point for Diversity - The Bar ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

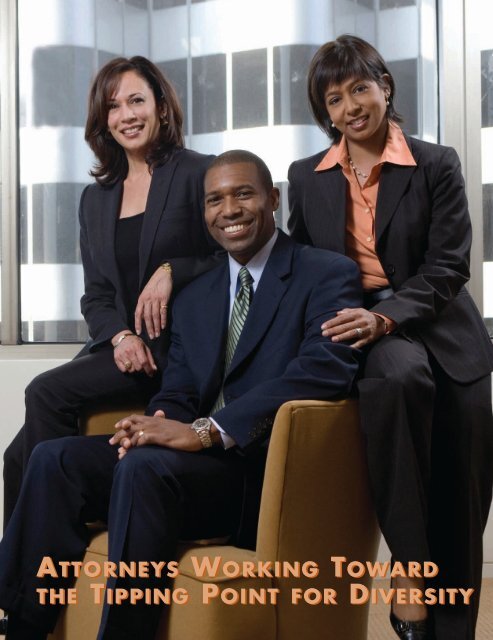

ATTORNEYS WORKING TOWARD<br />

THE TIPPING POINT FOR DIVERSITY

Behind many of <strong>the</strong> legal community’s ef<strong>for</strong>ts to pump up <strong>the</strong> diversity pipeline<br />

are attorneys who have a profound commitment to changing <strong>the</strong> profession.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y hail from large and small firms, solo practices, <strong>the</strong> bench, government<br />

offices, and nonprofits. Some, perhaps not surprisingly, are related, such<br />

as <strong>the</strong> powerhouse of sisters Kamala Harris, San Francisco’s district attorney, and<br />

Maya Harris, executive director of <strong>the</strong> ACLU of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, and her husband,<br />

Morrison & Foerster partner Tony West. What <strong>the</strong>y share in common is a<br />

nearly bottomless resource of energy to work toward what many hope is <strong>the</strong> tipping<br />

point <strong>for</strong> diversity in <strong>the</strong> profession.<br />

MAYA HARRIS<br />

In many ways, Maya Harris, now one year into her tenure as<br />

executive director of <strong>the</strong> ACLU of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, has<br />

been working toward opening <strong>the</strong> pipeline <strong>for</strong> ethnic and<br />

racial minorities <strong>for</strong> her entire legal career.<br />

She and sister Kamala Harris,<br />

<strong>the</strong> city’s district attorney, grew<br />

up in Oakland and Berkeley in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1960s and 1970s. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r was a graduate student<br />

at UC Berkeley during <strong>the</strong> civil<br />

rights movement. “Her activism<br />

was <strong>the</strong> subject of our dinner<br />

conversations,” says Harris. “I<br />

knew <strong>the</strong> law could have a big<br />

impact shaping <strong>the</strong> social playing<br />

field, that lawyers could foster<br />

progressive change.”<br />

Her mo<strong>the</strong>r drilled one thing<br />

into her daughters: “to whom<br />

much is given, much is expected.” Since graduating from<br />

Stan<strong>for</strong>d Law School, she has worked in roles seeking racial<br />

justice, specifically around <strong>the</strong> issues of criminal justice and<br />

educational equity. “When I look at <strong>the</strong> work I have done,<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r it’s focused on policy or litigation, <strong>the</strong> emphasis has<br />

been <strong>the</strong> pursuit of fairness, equality, opportunity, and inclusion,”<br />

Harris says.<br />

“I’ve been <strong>for</strong>tunate to be involved in ef<strong>for</strong>ts which I think<br />

have allowed us to make progress, but I feel like this work is<br />

a marathon. It’s a long road. We are making progress along<br />

<strong>the</strong> way, but we also have setbacks. You need to stay focused<br />

on what it is you are trying to achieve and persevere.”<br />

“If you don’t have kids<br />

of all races and ethnicities<br />

and income levels being<br />

provided with equal<br />

opportunities to succeed<br />

in <strong>the</strong> K–12 level,<br />

we will never solve<br />

this pipeline problem.”<br />

Susan Kostal<br />

<strong>The</strong> ACLU sees pipeline issues as key to personal success,<br />

both inside and outside <strong>the</strong> legal profession, Harris says.<br />

“Our mission and our substantive agenda are very directly<br />

focused on ensuring that those opportunities are available<br />

and that we are able to achieve that diversity. We’ve been concerned,<br />

<strong>for</strong> example, about how kids of color are being<br />

pushed out of school and, sometimes,<br />

into <strong>the</strong> criminal justice<br />

system. We’ve been achieving success<br />

in our ef<strong>for</strong>ts to stem those<br />

practices,” Harris says.<br />

Harris believes that diversity in<br />

<strong>the</strong> legal profession is a special<br />

concern. In tackling <strong>the</strong> issue,<br />

Harris says we need to “look as far<br />

upstream as possible” and focus<br />

on <strong>the</strong> education system. “It is<br />

not just a question of are our law<br />

schools diverse enough, but what<br />

is happening in all institutions of<br />

higher education, our colleges<br />

and universities, and also K–12 education. If you don’t have<br />

kids of all races and ethnicities and income levels being provided<br />

with equal opportunities to succeed in <strong>the</strong> K–12 level,<br />

we will never solve this pipeline problem.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> ALCU won a favorable settlement in Williams v. Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<br />

in 2004. <strong>The</strong> case sought to make amends <strong>for</strong> poorquality<br />

textbooks, facilities, and resources in schools serving<br />

low-income students. After four years of litigation, a landmark<br />

settlement was won; it stipulated that nearly $1 billion<br />

be spent on repairs and updated textbooks <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> state’s<br />

lowest-per<strong>for</strong>ming schools, where <strong>the</strong> students are overwhelmingly<br />

poor and children of color.<br />

Opposite page: from left, Kamala Harris, Tony West, Maya Harris<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 19

What does it mean that <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Cali<strong>for</strong>nia chapter, <strong>the</strong> ACLU’s largest<br />

national affiliate, is led by a woman of<br />

color (Harris’s mo<strong>the</strong>r is Indian American,<br />

having emigrated in 1960, and her<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r is Jamaican American.) “Every<br />

experience you have is in<strong>for</strong>med by so<br />

many things—your gender, your race,<br />

your ethnicity, your upbringing. I bring<br />

all that to <strong>the</strong> ACLU,” Harris says.<br />

“My mom always said you may have a<br />

lot of firsts in life, but make sure you<br />

are not <strong>the</strong> last. It is not about you; it is<br />

about what you do. I think that everyone<br />

who is in a position of authority<br />

and power and decision making has a<br />

responsibility to create opportunities<br />

<strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, especially those who have<br />

not had equal opportunities, who are<br />

underrepresented, those who would<br />

bring different life experiences to <strong>the</strong><br />

workplace and <strong>the</strong> work. Because that matters; it necessarily<br />

impacts <strong>the</strong> workplace and <strong>the</strong> work.”<br />

“I know doors were opened to me by o<strong>the</strong>rs. I don’t take<br />

lightly my responsibility to not just keep those doors open<br />

but to open <strong>the</strong>m wider.”<br />

Harris has mentored law students,<br />

both within and outside <strong>the</strong> ACLU. “I<br />

view that as an important part of my<br />

job and my life’s mission,” she says. “In<br />

every position I’ve had, whe<strong>the</strong>r it’s<br />

been teaching in law school, as an associate<br />

at a law firm, and through various<br />

positions at <strong>the</strong> ACLU, I’ve always<br />

looked <strong>for</strong> ways to both <strong>for</strong>mally and in<strong>for</strong>mally be able to<br />

support <strong>the</strong> development of o<strong>the</strong>r young lawyers.”<br />

Like her sister, Harris does a lot of public speaking, often at<br />

local colleges, and is frequently at press conferences (though<br />

<strong>the</strong>y could be viewed to be on opposite sides of some issues,<br />

it has yet to happen that <strong>the</strong> two women have had to oppose<br />

each o<strong>the</strong>r at press conferences). “<strong>The</strong> running joke in <strong>the</strong><br />

family is people look at us and say, ‘gosh, I can’t imagine what<br />

Thanksgiving is like at your house. <strong>The</strong> DA is at one end of<br />

<strong>the</strong> table, <strong>the</strong> head of <strong>the</strong> ACLU is at <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, and <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

Tony [West, her husband], a <strong>for</strong>mer prosecutor turned defense<br />

attorney, literally in <strong>the</strong> middle.”<br />

TONY WEST<br />

Tony West has always stood out.<br />

Whe<strong>the</strong>r it was his early work in<br />

politics, or his successes early in his<br />

career as an assistant U.S. attorney<br />

or deputy attorney general, or his career<br />

at Morrison & Foerster, where<br />

he is one of <strong>the</strong> protégés of James<br />

Brosnahan, West has had high-profile<br />

cases. And he’s part of a highprofile<br />

family. He is married to<br />

Maya Harris, executive director of<br />

<strong>the</strong> ACLU of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Cali<strong>for</strong>nia,<br />

<strong>the</strong> organization’s largest affiliate.<br />

His sister-in-law is Kamala Harris,<br />

San Francisco’s district attorney.<br />

But his most lasting success may end<br />

up being <strong>the</strong> years he has spent as<br />

hiring partner <strong>for</strong> Morrison &<br />

Foerster’s San Francisco office. (He<br />

spent three years as an official hiring<br />

partner but was active in <strong>the</strong> process be<strong>for</strong>e he was named<br />

partner in January 2004.)<br />

“During those years, we had <strong>the</strong> most diverse summer classes<br />

in MoFo’s memory,” says West. <strong>The</strong> firm’s success casts<br />

doubts on <strong>the</strong> refrain that <strong>the</strong>re are simply not enough minority<br />

candidates coming out of law school to meet <strong>the</strong> demands<br />

of large legal employers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> firm’s National Association <strong>for</strong> Law Placement (NALP)<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms bear this out. This year, 52 percent of <strong>the</strong> office’s<br />

twenty-five summer associates were racial and ethnic minorities<br />

or openly gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT)<br />

lawyers. Some 44 percent of <strong>the</strong> office’s associates this year,<br />

65 out of 145, were ethnic or racial minorities or openly<br />

LGBT attorneys.<br />

Previous years have similar statistics. Last year, 46 percent of<br />

<strong>the</strong> San Francisco office’s summer associates and 36.9 percent<br />

of associates were minority or LGBT attorneys. In 2005,<br />

65 percent of <strong>the</strong> summer associates were minorities or<br />

openly LGBT attorneys, and 40.5 percent of its associates. In<br />

2004, 35 percent of its summer associates were minority or<br />

LGBT students, and 39.7 percent of associates. In 2003, <strong>the</strong><br />

first year West was active in recruiting, half of <strong>the</strong> office’s<br />

summer associates were minorities or LGBT law students,<br />

and 38.2 percent of its associates.<br />

20 WINTER 2007

“<strong>The</strong>re was a very deliberate ef<strong>for</strong>t by those involved in recruiting,”<br />

and a team ef<strong>for</strong>t, says West. “It was certainly why<br />

I wanted to be hiring partner. I wanted it to be a rule that we<br />

hired 50 percent students of color. We are able to make that<br />

an institutional reality.”<br />

West feels confident those numbers will continue. “I know<br />

it is <strong>the</strong> philosophy of our chairman, Keith Wetmore,” he<br />

says. “If we are going to get to <strong>the</strong> point where we really need<br />

to be, which is that <strong>the</strong> profession reflects <strong>the</strong> richness of <strong>the</strong><br />

community we serve, <strong>the</strong>n diversity has to be part and parcel<br />

to any business plan. It has to be so ingrained in <strong>the</strong> way<br />

we think about how we grow <strong>the</strong> profession, how we grow<br />

firms, how we recruit, how we make a profit, that we don’t<br />

think about it. And we are not <strong>the</strong>re yet.”<br />

“If we are going to get<br />

to <strong>the</strong> point where<br />

we really need to be,<br />

which is that <strong>the</strong> profession<br />

reflects <strong>the</strong> richness<br />

of <strong>the</strong> community we serve,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n diversity has to be<br />

part and parcel<br />

to any business plan”<br />

And as <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> claim <strong>the</strong>re are not enough high-quality minority<br />

candidates “That is just not true,” he says. “It is true<br />

that large law firms tend to compete <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> same students<br />

from Boalt, Stan<strong>for</strong>d, Harvard, Yale, and <strong>the</strong> like. But what<br />

that misses is that <strong>the</strong>re are talented students of color in many<br />

places, coming out of many law schools. If your focus is on<br />

talent, as opposed to pedigree, you can be successful in recruiting<br />

talented attorneys of color.”<br />

West and fellow San Francisco partner Walter Conroy did it<br />

by recruiting at schools like Howard University, a historically<br />

black university in Washington, D.C. “One of our star summer<br />

associates from last summer, Michele Thomas, was a<br />

Howard law graduate. We had not been to Howard be<strong>for</strong>e,”<br />

West says. West also met strong candidates through <strong>the</strong> various<br />

organizations and political groups in which he is active.<br />

“You find legal talent in so many different places. One of <strong>the</strong><br />

individuals we had as a summer associate is someone I met<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Charles Houston <strong>Bar</strong> Association. Ano<strong>the</strong>r person,<br />

whom we offered a summer associate position <strong>for</strong> next summer,<br />

I first met while working on <strong>Bar</strong>ack Obama’s campaign.”<br />

(West is one of <strong>the</strong> cochairs of Obama’s presidential<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>ts in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.)<br />

West says <strong>the</strong> firm didn’t have any particular reaction to <strong>the</strong><br />

diversity of <strong>the</strong> summer class, “o<strong>the</strong>r than we had a really<br />

good group of students as summer associates<br />

coming through.”<br />

“I feel good about what we have done, but I am not satisfied<br />

where we are,” says West. “I’m excited about <strong>the</strong> challenge of<br />

continuing to do more.”<br />

“Clearly, I always have been cognizant of <strong>the</strong> fact that I am<br />

one of a very few African American partners in a major law<br />

firm. I’ve been very <strong>for</strong>tunate; o<strong>the</strong>rs have paved <strong>the</strong> way <strong>for</strong><br />

me. It has always been uppermost in my mind that <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

perhaps a special responsibility that I carry to make sure<br />

<strong>the</strong> door is open <strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. I don’t want to be <strong>the</strong> exception<br />

to <strong>the</strong> rule. I want to be <strong>the</strong> example of what <strong>the</strong> rule<br />

should be.”<br />

That said, West says he believes he has a special responsibility<br />

to remind o<strong>the</strong>rs “that it [diversity] is everyone’s job.”<br />

KAMALA HARRIS<br />

When you talk with Kamala Harris about diversity in <strong>the</strong><br />

profession, don’t expect her to talk about <strong>the</strong> business case <strong>for</strong><br />

diversity. For <strong>the</strong> city’s district attorney, diversity runs much<br />

deeper than that.<br />

“<strong>Diversity</strong> is critical to good law en<strong>for</strong>cement. We stand up<br />

in <strong>the</strong> courtroom every day and declare we are representing<br />

<strong>the</strong> people, and <strong>the</strong> people means all <strong>the</strong> people. In order <strong>for</strong><br />

us to do that appropriately, we need to be connected with,<br />

accessible to, and in touch with all <strong>the</strong> people in our community.<br />

We have a diverse community, and it’s important that<br />

<strong>the</strong> experiences of those communities are present when <strong>the</strong><br />

people are represented.”<br />

Harris, who was reelected in November, and her sister Maya<br />

Harris, who is executive director of <strong>the</strong> ACLU of Nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, are among <strong>the</strong> highest profile attorneys of color<br />

in <strong>the</strong> city. Since Harris was first elected district attorney in<br />

December 2003 (according to her Wikipedia entry, she’s <strong>the</strong><br />

city’s first woman, <strong>the</strong> state’s first African American woman,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> country’s first Indian American district attorney),<br />

she has been able to increase <strong>the</strong> diversity of <strong>the</strong> office. Some<br />

85 percent of her new hires from 2004 to 2006 have been<br />

women, people of color, or LGBT, she says.<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 21

“While I have been a beneficiary of<br />

affirmative action, <strong>the</strong>se are not affirmative<br />

action hires,” she says. “All <strong>the</strong><br />

people I hire are extremely competent<br />

and competitive and would be valued<br />

in any prosecutor’s office. One of <strong>the</strong><br />

misconceptions is that if you pay attention<br />

to diversity, you are neglecting<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance and competence, and nothing could be fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

from <strong>the</strong> truth.”<br />

Harris says she does feel a special responsibility to continue<br />

to work toward a more diverse profession. “But it is not because<br />

of who I am; it is because of what I do. I am a lawyer;<br />

a prosecutor. I’m a trial lawyer. When you want to make a<br />

decision that has <strong>the</strong> best outcome <strong>for</strong> justice, <strong>the</strong>n part of <strong>the</strong><br />

process is to have people believe it is fair and represents all<br />

people in an even-handed way. One of <strong>the</strong> best ways to make<br />

decisions relative and fair is to take into account all perspectives<br />

and experiences. And that means having a commitment<br />

to diversity, so <strong>the</strong> diverse experiences of human beings will<br />

be present when we make those decisions.”<br />

HELEN SANTANA<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re aren’t enough role models in prominent view of how<br />

a woman of color can achieve success,” Harris says. “When I<br />

was a young prosecutor in Alameda County, it was important<br />

<strong>for</strong> domestic violence or rape victims to be able to see a<br />

woman <strong>the</strong>y perceived as being in control and strong. It was<br />

very empowering, especially when <strong>the</strong>y felt that person identified<br />

with <strong>the</strong>m and saw <strong>the</strong>m <strong>for</strong> who <strong>the</strong>y were.”<br />

Harris firmly believes <strong>the</strong>re are “pipeline issues.” “<strong>The</strong>re are<br />

not enough young people choosing law school over o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

professions. If we are going to make a commitment to diversity<br />

in <strong>the</strong> legal workplace, we need to be committed to outreach<br />

to college students of color, to create meaningful<br />

opportunities <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>m to be accepted into and survive law<br />

school, to <strong>the</strong>n graduate and come into <strong>the</strong> work environment,”<br />

says Harris. Those who interpret <strong>the</strong> Constitution<br />

have a powerful role, Harris says. And if <strong>the</strong>re are fewer<br />

African American and Latino lawyers, that means <strong>the</strong>ir voices<br />

will be lost as <strong>the</strong> law develops.<br />

Harris has launched her own initiative to get nonviolent firstoffense<br />

eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old drug defendants back<br />

in <strong>the</strong> education and work <strong>for</strong>ce system. Called Back on Track,<br />

it’s her flagship “smart on crime” initiative and has been copied<br />

by o<strong>the</strong>r prosecutors. <strong>The</strong> program has reduced <strong>the</strong> recidivism<br />

rate of <strong>the</strong>se defendants considerably (from 50 percent to less<br />

than 10 percent, Harris says). And while she doesn’t know if<br />

any have gone on to law school, some have gone on to fouryear<br />

universities and have <strong>the</strong> potential to go beyond that. “I<br />

think some of those Back on Track participants could be tomorrow’s<br />

lawyers. <strong>The</strong>y are not <strong>the</strong>re because <strong>the</strong>y have a low<br />

IQ. <strong>The</strong>y have <strong>the</strong> capacity; it is just getting <strong>the</strong>m on <strong>the</strong> right<br />

track, which is <strong>the</strong> best way to reduce crime.”<br />

Photo by Martha Bruce Photography<br />

Helen Santana has been opening doors through hard work<br />

and reaching out to o<strong>the</strong>rs since she became a lawyer. <strong>The</strong><br />

first generation in her family to go to graduate school in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States (along with her bro<strong>the</strong>r, who is also an<br />

attorney), Santana has spent much of her career assuring that<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs have <strong>the</strong> same opportunities.<br />

Born and raised in San Francisco, Santana had an internship<br />

in an insurance office while she was still in high school.<br />

She kept up her ties with <strong>the</strong> company while attending<br />

<strong>the</strong> University of San Francisco and <strong>the</strong>n Golden Gate<br />

University School of Law, where she graduated in 1991.<br />

In 1996, she joined Liberty Mutual, and today Santana is<br />

<strong>the</strong> manager of <strong>the</strong> Liberty Mutual San Francisco field<br />

office, which handles workers’ compensation and civil<br />

litigation in <strong>the</strong> San Francisco Bay Area, supervising a staff<br />

of <strong>for</strong>ty-eight, in cluding twenty attorneys, nine paralegals,<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r support staff. Santana received an MBA from<br />

Golden Gate University in 2005.<br />

22 WINTER 2007

She oversees a diverse staff, and this year Santana and Liberty<br />

Mutual were honored by Golden Gate University School<br />

of Law as its employer of <strong>the</strong> year.<br />

<strong>the</strong> way. This is a good way to give back. It opens up opportunities<br />

to people and diversifies <strong>the</strong> field of candidates to be<br />

considered by different types of companies and law firms.”<br />

About eight years ago, she began to get involved in minority<br />

bar activities and within several years was engaged in leadership<br />

roles, particularly in <strong>the</strong> Hispanic National <strong>Bar</strong> Association<br />

(HNBA), where she serves as regional president <strong>for</strong><br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Cali<strong>for</strong>nia and Hawaii, and she is a key leader in a<br />

mentoring program HNBA rolled<br />

out last year.<br />

Partnering locally with San Francisco<br />

La Raza Lawyers Association (Santana<br />

is on its board, as well), HNBA<br />

currently has <strong>for</strong>ty pairs of mentors<br />

and mentees, most of whom are law<br />

students. “We paired <strong>the</strong>m up to have<br />

someone guide <strong>the</strong>m along a professional<br />

path,” says Santana. “We did<br />

not want to <strong>for</strong>ce anything; it has<br />

been an in<strong>for</strong>mal process. We have<br />

had a couple of events so <strong>the</strong>y can get<br />

to know one ano<strong>the</strong>r.”<br />

Some of <strong>the</strong> pairings have proved very beneficial. “One law<br />

student, who played a vital part in implementing <strong>the</strong> program,<br />

is now working her way up <strong>the</strong> ladder within <strong>the</strong><br />

HNBA’s Law Student Division. <strong>The</strong> law student is a 3L at<br />

Hastings, was elected president of her region, and is now running<br />

<strong>for</strong> national office.”<br />

Santana says <strong>the</strong> pairings have helped <strong>the</strong> law students become<br />

more firmly involved in minority bar associations, an<br />

involvement that provides <strong>the</strong>m with opportunities to practice<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir leadership skills, network, and become more firmly<br />

grounded as professionals.<br />

In her experience, being part of a mentorship program is<br />

often <strong>the</strong> factor that makes or breaks a new lawyer’s early<br />

career. “Some law students and attorneys have wanted to<br />

leave <strong>the</strong>ir jobs at firms that did not have a mentoring<br />

component,” she says. “<strong>The</strong>y do not always see <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

<strong>for</strong> promotional opportunities within <strong>the</strong>ir firms. You<br />

need to know how to maneuver <strong>the</strong> corporate ladder,<br />

network, and seek out those who can assist you to climb to<br />

those aspirations.”<br />

Santana says she is <strong>for</strong>tunate to have found those who could<br />

guide her. “Mentoring is something that really can have an<br />

impact. I was lucky to have people who mentored me along<br />

“Mentoring is<br />

something that<br />

really can have an<br />

impact. I was lucky<br />

to have people<br />

who mentored me<br />

along <strong>the</strong> way.”<br />

HNBA also hosts an annual job fair, which gets strong reviews<br />

from employers. “Employers tell us <strong>the</strong>y are impressed<br />

with <strong>the</strong> overall caliber of students that come out of <strong>the</strong>se job<br />

fairs. <strong>The</strong>y often open doors <strong>for</strong> students who would not o<strong>the</strong>rwise<br />

be able to get an interview with a large firm or large<br />

company. <strong>The</strong> exposure that comes<br />

from that job fair is a once-in-a-lifetime<br />

opportunity. <strong>The</strong>re are some high-quality<br />

candidates out <strong>the</strong>re who have never<br />

had <strong>the</strong> ability to get through <strong>the</strong> door.”<br />

Under <strong>the</strong> leadership of HNBA National<br />

President Victor M. Marquez,<br />

principal of <strong>the</strong> Marquez Law Group,<br />

Santana’s local HNBA region is looking<br />

at expanding <strong>the</strong> mentorship program<br />

to <strong>for</strong>ge tripartite relationships and to<br />

include lawyers in <strong>the</strong>ir first five years of<br />

practice. <strong>The</strong> idea is that <strong>the</strong> three (law<br />

student, associate, senior attorney)<br />

would be able to teach and energize each o<strong>the</strong>r. “<strong>The</strong>re are a<br />

lot of attorneys out <strong>the</strong>re in that middle to junior tier that<br />

are very talented. I do not see why <strong>the</strong>y should not be able to<br />

move into <strong>the</strong> partnership ranks,” Santana says. <strong>The</strong>re is a<br />

lack of minority attorneys in those senior ranks, “but that is<br />

going to change, I am confident of that.”<br />

Santana and HNBA have been able to accomplish much by<br />

harnessing <strong>the</strong> resources of local employers, including Liberty<br />

Mutual, which has been a sponsor <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> last two national<br />

conventions. Liberty Mutual was also one of <strong>the</strong><br />

cohosts, <strong>for</strong> example, of HNBA’s kickoff reception <strong>for</strong> its national<br />

mentoring program last year. Additionally, Liberty<br />

Mutual has supported Santana’s participation in <strong>the</strong> HNBA,<br />

<strong>for</strong> which she is very appreciative.<br />

Santana says numerous BASF contacts have been very helpful<br />

and supportive of her ef<strong>for</strong>ts with La Raza and HNBA, including<br />

Edwin Pra<strong>the</strong>r, a criminal defense lawyer with<br />

Clarence & Dyer and <strong>the</strong> president of <strong>the</strong> Asian American<br />

<strong>Bar</strong> Association and a <strong>for</strong>mer BASF board member; Russell<br />

Roeca, BASF treasurer; and Abby Ginzberg, who helped coordinate<br />

BASF’s diversity projects be<strong>for</strong>e Yolanda Jackson<br />

joined <strong>the</strong> staff.<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 23

Through it all, he has written and spoken regularly on race<br />

and diversity issues and been involved in a range of bar<br />

groups, including BASF and its <strong>Diversity</strong> Task Force, <strong>the</strong> executive<br />

committee of <strong>the</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Minority Counsel Program,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> board of <strong>the</strong> Asian American <strong>Bar</strong> Association.<br />

“<strong>Diversity</strong> in <strong>the</strong> legal profession is very important to me. I<br />

care about it, have invested in it, have a lot of feelings and<br />

opinions on it, and choose to devote my time to it.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>re has been some positive news in <strong>the</strong> local legal community’s<br />

commitment to diversity, Weng says. But despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> good words and sentiments, which are an important first<br />

step, “in terms of what has actually happened, I have some<br />

frustration and impatience, because we are not as far along as<br />

I would have hoped.”<br />

Most firms have commitments to diversity on <strong>the</strong>ir Web<br />

sites, and it’s easy to go on <strong>the</strong> Internet and find corporate<br />

best practices. <strong>Bar</strong> groups continue to host diversity conferences,<br />

which <strong>the</strong> tried and true continue to attend. Weng<br />

says that with all this in<strong>for</strong>mation out <strong>the</strong>re, you would think<br />

it would be easier, but apparently, it is not. He thinks that although<br />

people mean quite well, it’s hard to really implement<br />

measures that make a real change in <strong>the</strong> makeup of law firms<br />

and corporate law offices.<br />

GARNER WENG<br />

Garner Weng is one of those people who seem to defy <strong>the</strong><br />

physical laws that bind <strong>the</strong> rest of us. For one, he juggles a<br />

practice that includes both litigation and transactional work.<br />

With two degrees from Stan<strong>for</strong>d (a BS in computer science<br />

and an MA in education), Weng is a Boalt Hall graduate,<br />

law review editor, and <strong>for</strong>mer class president. When he<br />

joined Hanson Bridgett, he made partner faster than anyone<br />

since <strong>the</strong> firm established a partnership track. He soon became<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> youngest to chair a practice group (emerging<br />

companies) and <strong>the</strong>n one of <strong>the</strong> youngest partners on <strong>the</strong><br />

firm’s management committee.<br />

That’s because, as Weng has found, it comes down to influencing<br />

one person at a time. And that’s a slow process. “I’ve<br />

written things that have gotten a lot of circulation. Perhaps<br />

“<strong>Diversity</strong> in <strong>the</strong> legal<br />

profession is very<br />

important to me. I care<br />

about it, have invested<br />

in it, have a lot of<br />

feelings and opinions<br />

on it, and choose to<br />

devote my time to it.”<br />

you can stop and get people to think and absorb an<br />

additional idea, but overall your impact in that fashion is<br />

still limited. I don’t think that is really changing <strong>the</strong><br />

world. Whereas if you work with an individual, in a smaller<br />

setting, you can see things happen, move that individual<br />

along, move <strong>the</strong> group along in a real and concrete way.<br />

That’s what gets you <strong>the</strong> most traction and allows you to have<br />

<strong>the</strong> most influence. It really is as hard as a person at a time,”<br />

Weng says.<br />

Weng started in his own backyard. “[At Hanson Bridgett]<br />

we’ve gotten some traction in our diversity ef<strong>for</strong>ts,” says<br />

Weng. “<strong>The</strong>re is a general culture here of friendly collaboration<br />

and teamwork that’s not always present in every law<br />

firm. It runs fairly deep here. We bring in work toge<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

work in teams toge<strong>the</strong>r. And that plays into our general atmosphere<br />

of inclusiveness.”<br />

24 WINTER 2007

That means <strong>the</strong>re is no impediment<br />

to Hanson Bridgett’s diversity ef<strong>for</strong>ts,<br />

he says. Since 1989, Hanson Bridgett<br />

has increased its percentage of associates<br />

of color by nearly four times and<br />

its percentage of partners and senior<br />

counsel of color by more than three<br />

times. Weng is on <strong>the</strong> recruiting committee<br />

and says Hanson Bridgett has made strides in its minority<br />

hiring. “<strong>The</strong>re is a greater percentage of minority<br />

partners and associates since I started at <strong>the</strong> firm. <strong>The</strong> firm<br />

has grown, and <strong>the</strong> percentages have gotten better, but not as<br />

fast as I would like to see <strong>the</strong>m change.”<br />

Weng said <strong>the</strong> problem is not finding top candidates. It’s in<br />

convincing <strong>the</strong>m that a small firm like Hanson Bridgett is<br />

where <strong>the</strong>y should be. Weng tries to lure <strong>the</strong>m by showing<br />

<strong>the</strong>m his own career path, illustrating that it’s easier to build<br />

your own career and book of business at Hanson Bridgett than<br />

it might be at a larger firm. “Generally, <strong>the</strong> focus in big firms<br />

is on larger clients and larger matters, so sometimes our size<br />

helps us,” he says.<br />

KELLY DERMODY<br />

Kelly Dermody has had <strong>the</strong> privilege of practicing law in a<br />

firm that has one of <strong>the</strong> most successful gay attorneys in <strong>the</strong><br />

country at its helm.<br />

But Dermody, a partner at Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein,<br />

knows all too well that is not <strong>the</strong> experience of most<br />

LGBT attorneys in <strong>the</strong> city. Dermody, along with Morgan<br />

Lewis & Bockius attorney L. Julius M. Turman, spearheaded<br />

<strong>the</strong> November report from <strong>the</strong> BASF Equality Committee<br />

on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues on LGBT<br />

attorneys in San Francisco, which showed that those attorneys<br />

face both subtle and direct bias, whe<strong>the</strong>r it is personal or<br />

in <strong>the</strong> types of employee benefits firms offer.<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re hasn’t been a huge push from LGBT attorneys to have<br />

numbers studies [similar to <strong>the</strong> bar’s diversity goals and<br />

timetables]. People do not perceive <strong>the</strong> issue as predominantly<br />

about counting numbers,” Dermody says. Indeed, in<br />

at least <strong>the</strong> Bay Area, firms have made “enormous strides” in<br />

hiring and promoting gay and lesbian attorneys into positions<br />

of prominence.<br />

“From my own experience, when I sought out opportunities<br />

to progress in my career, I just never felt like my race was an<br />

issue. It came down to talent, desire, and interest.” Weng says<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Minority Counsel Program (CMCP) played<br />

an important role, providing contacts and <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

to build relationships that ultimately led to work. O<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

have had similar results with CMCP, he says.<br />

Weng believes BASF will play a larger role in advancing <strong>the</strong><br />

careers of minority attorneys now that <strong>the</strong> bar has hired<br />

Yolanda Jackson as its director of diversity programs. “I feel<br />

like <strong>the</strong> bar has a lot of potential. It has a strong, wide membership<br />

base and resources that many o<strong>the</strong>r organizations<br />

don’t have.”<br />

Weng is involved personally in pipeline ef<strong>for</strong>ts. He serves on<br />

<strong>the</strong> advisory committee to Boalt Hall Professor Marjorie<br />

Shultz’s and UC Berkeley Professor Sheldon Zedeck’s Looking<br />

Beyond <strong>the</strong> LSAT project at Boalt Hall, which looks at<br />

how much—or how little—<strong>the</strong> LSAT is a proper measure of<br />

what is a good lawyer. <strong>The</strong> project’s research hopes to identify<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r factors that law firms should consider and to<br />

re<strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong> LSAT itself. Weng also persuaded Hanson Bridgett<br />

to become a funder of <strong>the</strong> research. “This is a direct investment<br />

in <strong>the</strong> future of <strong>the</strong> profession,” he says. “Law<br />

schools serve a gatekeeper function. If we could add ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

level of diversity at <strong>the</strong> law school level, it would be a very<br />

positive thing.”

“What has been driving <strong>the</strong> LGBT<br />

community to seek more leadership<br />

from <strong>the</strong> bar, and <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> bar to respond,<br />

is <strong>the</strong> perception among<br />

LGBT attorneys that, in spite of improvements<br />

in firm culture and inclusivity,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re have been institutional<br />

issues in achieving a firm culture that<br />

is truly fair and welcoming to all attorneys,” Dermody says.<br />

<strong>The</strong> goal has been to point out some of <strong>the</strong> subtle biases and<br />

show legal employers ways to rectify that. “<strong>The</strong>re are still benefits<br />

programs that disadvantage LGBT lawyers. <strong>The</strong>re are<br />

still pockets where a lack of com<strong>for</strong>t or familiarity with LGBT<br />

people results in things that are said and done that are very<br />

uncom<strong>for</strong>table. Some clients are still uncom<strong>for</strong>table with<br />

LGBT people.”<br />

Dermody called it “one of those funny truths about San Francisco.”<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> number of LGBT attorneys in <strong>the</strong> city,<br />

“when I talk to friends of mine who work at o<strong>the</strong>r firms, including<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r progressive firms, <strong>the</strong>y describe some pretty un<strong>for</strong>tunate<br />

situations, where <strong>the</strong>y are not mentored, or clients<br />

do not want to work with <strong>the</strong>m. <strong>The</strong>re is a particular culture<br />

that exists in which if you don’t look like a feminine<br />

woman or a masculine man, you are disfavored. It continues<br />

to be a gendered culture at some firms.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> committee’s focus is not a survey of law firm hiring and<br />

promotion statistics, <strong>the</strong>n, but an ef<strong>for</strong>t to in<strong>for</strong>m firms about<br />

<strong>the</strong> experiences of LGBT attorneys and catalogue best practices<br />

in <strong>the</strong> hiring and retention of LGBT attorneys. “Firms<br />

that don’t pay attention to what cultures are being created<br />

run <strong>the</strong> risk of having a whole lot of attorneys perceive <strong>the</strong><br />

firm as being inhospitable to LGBT attorneys.” Dermody<br />

says. And those attorneys, <strong>for</strong> many, are seen as <strong>the</strong> canaries<br />

in <strong>the</strong> coal mines. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> firm’s treatment of<br />

LGBT attorneys sends a message to all.<br />

Complicating matters is new evidence from both state and<br />

local bar surveys that LGBT attorneys are highly reluctant to<br />

complain. According to a recent State <strong>Bar</strong> of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia survey,<br />

“a large number of LGBT attorneys reported experiencing<br />

unfairness in legal organizations, but none reported it to<br />

anyone,” Dermody says.<br />

“Something is happening at firms with LGBT attorneys. If<br />

<strong>the</strong>y perceive something is not working, <strong>the</strong>y don’t say anything.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are leaving” instead. Both Dermody and Turman<br />

said LGBT attorneys believe <strong>the</strong>y won’t be treated appropriately<br />

or seriously if <strong>the</strong>y complain. “<strong>The</strong>y think complaining<br />

will do more harm than good. So firms are not getting <strong>the</strong><br />

message that <strong>the</strong>re is even a problem, much less that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

need to change,” Dermody says.<br />

<strong>The</strong> BASF report, published at <strong>the</strong> end of November, has<br />

concrete recommendations <strong>for</strong> firms that want to improve<br />

conditions <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir LGBT attorneys and, by extension, all<br />

attorneys. “Firms assume that having a policy of fairness<br />

means <strong>the</strong> firm is fair. That is misguided. Passive policies don’t<br />

result in actual fairness. People need to be much more proactive<br />

and self-critical to ensure fairness is actualized.”<br />

It is perhaps not at all ironic that two employment lawyers<br />

head <strong>the</strong> BASF Equality Committee on LGBT Issues. While<br />

Dermody also handles consumer fraud cases, she has been<br />

opposite Turman in at least one high-level employment case.<br />

“Julius defends <strong>the</strong> companies I sue,” Dermody says.<br />

BASF’s Equality Committee on LGBT Issues is just one outlet<br />

<strong>for</strong> Dermody. On <strong>the</strong> BASF board of directors, she is also on <strong>the</strong><br />

board (and has served as past board cochair) of <strong>the</strong> National Center<br />

<strong>for</strong> Lesbian Rights, as well as having served as past board<br />

cochair <strong>for</strong> both <strong>the</strong> Lawyers’ Committee <strong>for</strong> Civil Rights and <strong>the</strong><br />

Pride Law Fund, a nonprofit that promotes <strong>the</strong> legal rights of<br />

<strong>the</strong> lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community, and people<br />

living with HIV and AIDS. Pride Law Fund funds legal services<br />

projects <strong>for</strong> law students and new lawyers, including through<br />

<strong>the</strong> Tom Steel Postgraduate Fellowship, which Dermody helped<br />

launch in 1999. Dermody is currently helping to launch Carver<br />

Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools<br />

(Carver HEARTS), which will fund a <strong>the</strong>rapist at Dr. George<br />

Washington Carver Elementary School in Bayview-Hunter’s<br />

<strong>Point</strong> to assist children process <strong>the</strong>ir exposure to trauma and violence<br />

and to address <strong>the</strong> epidemic of stress and posttraumatic<br />

stress disorder among students and <strong>the</strong>ir families.<br />

“Firms that don’t pay<br />

attention to what cultures<br />

are being created<br />

run <strong>the</strong> risk of having<br />

a whole lot of attorneys<br />

perceive <strong>the</strong> firm<br />

as being inhospitable<br />

to LGBT attorneys.”<br />

26 WINTER 2007

L. JULIUS M. TURMAN<br />

Even though moving his practice here made it much easier to<br />

be openly gay, he has found that San Francisco is not <strong>the</strong> ideal<br />

environment some might believe, or wish, it to be.<br />

“People here have <strong>the</strong> view that we are out <strong>the</strong>re, we are<br />

functioning well, and everything is fine. What I can tell you,<br />

both by anecdotal evidence and survey in<strong>for</strong>mation, is that<br />

LBGT attorneys do have issues that come up in <strong>the</strong>ir firms,”<br />

Turman says.<br />

Turman is cochair, along with Kelly Dermody of Lieff<br />

Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein, of BASF’s Equality Committee<br />

on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues,<br />

under <strong>the</strong> rubric of BASF’s Equality Committees. In January<br />

2007 <strong>the</strong> subcommittee began studying what it could do<br />

to improve <strong>the</strong> life of <strong>the</strong> city’s LGBT attorneys. That work<br />

led to local surveys that showed that LGBT attorneys experience<br />

discrimination but do not report it. “<strong>The</strong>y are reluctant<br />

to have those issues addressed,” says Turman. A recent<br />

State <strong>Bar</strong> survey found similar results.<br />

Turman, Dermody, and o<strong>the</strong>rs have worked diligently to<br />

bring those issues to light. In a report that came out in November,<br />

<strong>the</strong> committee highlights <strong>the</strong> sometimes subtle discrimination<br />

LGBT attorneys face and rein<strong>for</strong>ces that <strong>the</strong><br />

needs of LGBT attorneys merit attention.<br />

For years, <strong>the</strong>re has been some discussion that BASF should<br />

track LGBT associates and partners as part of its diversity<br />

goals and timetables. Firms already track such data on<br />

NALP <strong>for</strong>ms.<br />

L. Julius M. Turman did not always practice law in <strong>the</strong> Bay<br />

Area. He began his career on <strong>the</strong> East Coast as an assistant<br />

U.S. attorney in New Jersey and <strong>the</strong>n later worked as corporate<br />

counsel to Ketchum Worldwide Communications.<br />

That he was a black man was clear. That he was gay was not.<br />

“In those days, being LGBT was taboo,” Turman says. “It<br />

was an eye-opening experience to come to San Francisco” and<br />

Morgan Lewis & Bockius, where he is of counsel in <strong>the</strong> firm’s<br />

San Francisco office in <strong>the</strong> labor and employment practice<br />

group. He joined <strong>the</strong> firm in February 2006.<br />

He quickly became involved in a host of local bar activities,<br />

including <strong>the</strong> BASF board of directors, <strong>the</strong> Charles Houston<br />

<strong>Bar</strong> Association, <strong>the</strong> Alice B. Toklas LGBT Democratic Club,<br />

Bay Area Lawyers <strong>for</strong> Individual Freedom, and <strong>the</strong> Magic<br />

<strong>The</strong>atre. He serves on <strong>the</strong> boards or as cochair of most of <strong>the</strong><br />

groups with which he is involved .<br />

<strong>The</strong> report should help rectify that. “I don’t think that people<br />

have been overlooked,” says Turman. “<strong>The</strong>y’ve been sort<br />

of ignored by assumption that things are fine—especially in<br />

San Francisco.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> goal of <strong>the</strong> committee is to empower both LGBT attorneys<br />

and firms to work on eliminating <strong>the</strong> subtle bias and<br />

stereotypes <strong>the</strong> State <strong>Bar</strong> survey shows do exist. “<strong>The</strong>re is so<br />

much a firm can do, with little expense, to improve its culture<br />

by showing it wants to recruit <strong>the</strong> best and brightest, which<br />

include LGBT attorneys,” says Turman. “<strong>The</strong>y want pro bono<br />

projects that reflect an overall commitment to diversity, and<br />

that includes professional development and cultural sensitivities<br />

to <strong>the</strong> life of LGBT attorneys in a large firm.”<br />

For example, Turman says, many firms believe <strong>the</strong>y offer<br />

LGBT attorneys and <strong>the</strong>ir partners <strong>the</strong> same benefits <strong>the</strong>y<br />

offer all employees. “But when you drill down, because <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are no federal protections, a lot of plans don’t treat <strong>the</strong> partners<br />

and families of LGBT attorneys as <strong>the</strong>y treat families of<br />

straight attorneys. <strong>The</strong>y don’t clearly understand <strong>the</strong>ir obliga-<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 27

tions if <strong>the</strong>se families don’t naturally fall under COBRA.”<br />

(<strong>The</strong> Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act—<br />

COBRA—is <strong>the</strong> federal law covering health benefit plans.)<br />

When Turman isn’t working on changing <strong>the</strong> broader environment<br />

<strong>for</strong> LGBT attorneys, he’s working on influencing<br />

<strong>the</strong> careers of individual attorneys, one mentee at a time.<br />

“Mentoring young attorneys, be <strong>the</strong>y black, white, straight,<br />

gay, is something that I live <strong>for</strong>. I love practicing law, I love<br />

<strong>the</strong> firm I am with, and I love sharing what’s good about that<br />

experience with anyone who will listen.”<br />

Turman says <strong>the</strong>re is a misconception about what mentoring<br />

relationships should focus on. “Mentoring is not about going<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re is so much<br />

a firm can do, with<br />

little expense, to improve<br />

its culture by showing<br />

it wants to recruit<br />

<strong>the</strong> best and brightest,<br />

which include<br />

LGBT attorneys.”<br />

Simply put, as <strong>the</strong> population of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia shifts, <strong>the</strong> bench<br />

is falling fur<strong>the</strong>r behind in mirroring <strong>the</strong> people it serves. Statistics<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Administrative Office of <strong>the</strong> Courts (AOC)<br />

show <strong>the</strong> bench is 70 percent Caucasian; Caucasians, however,<br />

are now a minority population in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia. Retiring<br />

ethnic minority judges are not being replaced with ethnic minority<br />

appointees. “Our bench has been in a period of retrenchment,<br />

so to speak, and becoming less and less like <strong>the</strong><br />

population judges are serving,” Harbin-Forte says. Is <strong>the</strong><br />

problem in <strong>the</strong> pipeline or <strong>the</strong> process<br />

It is, Harbin-Forte’s group concluded, both. But in a short<br />

period of time, <strong>the</strong> group, an outgrowth of <strong>the</strong> State <strong>Bar</strong>’s<br />

<strong>Diversity</strong> Pipeline Task Force, has been able to <strong>for</strong>ge strong<br />

working relationships with <strong>the</strong> governor’s office and suggest<br />

concrete changes (some of which have already become law)<br />

in <strong>the</strong> selection process, and Harbin-Forte is optimistic that<br />

<strong>the</strong>se relationships and changes will lead to a shift in statistics.<br />

<strong>The</strong> changes include disclosing aggregate data on <strong>the</strong><br />

ethnicity and gender of all judicial applicants, those that<br />

make it to evaluation by <strong>the</strong> State <strong>Bar</strong>, and appointees. <strong>The</strong><br />

group also suggested that <strong>the</strong> governor’s office, AOC, and <strong>the</strong><br />

State <strong>Bar</strong> begin tracking <strong>the</strong> appointments of judges who are<br />

LGBT or have a disability.<br />

out to lunch and talking about how you are fitting in. Mentoring<br />

takes place in <strong>the</strong> work. Let’s look at your work product,<br />

let’s see how to improve it, what you are doing right, and<br />

what we need to work on.”<br />

More LGBT attorneys are asking <strong>for</strong> LGBT mentors, Turman<br />

says. “I have a special obligation, and <strong>the</strong> firm supports<br />

me in that,” Turman says. “Your firm never changes if you<br />

back away from those obligations. Being black and gay probably<br />

shut me out of so many things in <strong>the</strong> past. I embrace<br />

who I am in all aspects today and use it to open doors <strong>for</strong> me<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>rs.”<br />

BRENDA HARBIN-FORTE<br />

For years, Alameda County Superior Court Judge Brenda<br />

Harbin-Forte has spoken out about <strong>the</strong> need to diversify <strong>the</strong><br />

bench in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia. She was given that role officially when<br />

<strong>the</strong> State <strong>Bar</strong> appointed her in March 2007 as chair of <strong>the</strong><br />

Council on Access and Fairness, which advises <strong>the</strong> board of<br />

governors on diversifying <strong>the</strong> legal profession.<br />

28 WINTER 2007

“It’s not just a pipeline issue, a numbers<br />

issue,” says Harbin-Forte. “It’s a<br />

process issue. We realized that while<br />

we want to get more women and minorities<br />

to put in applications to <strong>the</strong><br />

bench, <strong>the</strong>y would not if <strong>the</strong>y didn’t<br />

feel <strong>the</strong>y had a chance.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> result has been a steady whittling away of minorities on<br />

<strong>the</strong> bench. Harbin-Forte’s group collected <strong>the</strong>ir own statistics,<br />

and some were glaring. Of <strong>the</strong> 1,498 superior court<br />

judges in <strong>the</strong> state, only 262, or 17.5 percent, are ethnic minorities.<br />

Some 46 Cali<strong>for</strong>nia counties had no African American<br />

judges on <strong>the</strong> bench at all. Of Orange County’s 109<br />

judicial seats, ethnic minority judges held only 17. <strong>The</strong> appellate<br />

courts fared even worse. For example, <strong>the</strong>re are only<br />

3 African American judges on <strong>the</strong> 112-justice appellate<br />

bench, including <strong>the</strong> state Supreme Court.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r counties had statistics more in line with <strong>the</strong> county<br />

populations. In Alameda, <strong>for</strong> instance, where Harbin-Forte<br />

sits, 20 percent of <strong>the</strong> judgeships are held by African<br />

Americans; 13 percent of <strong>the</strong> county population is African<br />

American.<br />

<strong>The</strong> council was concerned that <strong>the</strong> selection procedure and<br />

processes needed to be revised and, most importantly, become<br />

more transparent. “We wanted a clearer understanding<br />

of <strong>the</strong> methods by which judges are selected,” says<br />

Harbin-Forte. <strong>The</strong> group also felt <strong>the</strong> members of <strong>the</strong> Commission<br />

on Judicial Nominees Evaluation (JNE—nicknamed<br />

<strong>the</strong> Jenny Commission) could use some training in identifying<br />

hidden biases that may be reflected in <strong>the</strong> ratings and<br />

comments provided by <strong>the</strong> evaluators and in <strong>the</strong> final rating<br />

given a candidate by <strong>the</strong> JNE Commission itself.<br />

“When I became a judge, I was very concerned about <strong>the</strong> appearance<br />

of fairness and that people feel that, when <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir day in court, <strong>the</strong>y have been listened to, heard, and<br />

treated fairly. I have been very active in my community, and<br />

when I talked to numerous people on <strong>the</strong> street, <strong>the</strong>y felt like<br />

<strong>the</strong>y weren’t getting a fair shake. <strong>The</strong>y thought it was due to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir race or ethnicity, but that wasn’t always <strong>the</strong> case. But<br />

<strong>the</strong>y thought no one in <strong>the</strong> court system really cared about<br />

<strong>the</strong>m,” she said.<br />

Harbin-Forte said Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has<br />

been open to <strong>the</strong> Council on Access and Fairness’s concerns<br />

and is making a “genuine ef<strong>for</strong>t” to improve <strong>the</strong> diversity<br />

of <strong>the</strong> bench. She pointed in particular to his appointment<br />

of Sharon Majors Lewis, his judicial appointments secretary.<br />

“She has made dramatic inroads in increasing diversity.<br />

Judge Harbin-Forte with her collection of stuffed animals, which she presents<br />

to newly adopted children.<br />

Her presence, in terms of <strong>the</strong> outreach she is doing, is<br />

just remarkable.”<br />

“A confluence of events” is leading to possibilities of real<br />

change, she says, including outreach activities by <strong>the</strong> ethnic<br />

bar associations, <strong>the</strong> State <strong>Bar</strong>’s <strong>Diversity</strong> Pipeline Task Force<br />

Report of February 2007, which highlighted <strong>the</strong> barriers and<br />

made concrete recommendations <strong>for</strong> change, and <strong>the</strong> Summit<br />

on <strong>Diversity</strong> in <strong>the</strong> Judiciary in June 2006, which gained<br />

increased attention through <strong>the</strong> support of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<br />

Supreme Court Chief Justice Ronald George.<br />

Harbin-Forte said that her group found what o<strong>the</strong>rs have<br />

highlighted—that <strong>the</strong> “weak link” in <strong>the</strong> pipeline extends to<br />

even <strong>the</strong> elementary school level. “We are losing children that<br />

early,” she says.<br />

As <strong>for</strong>mer dean of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia’s Judicial College (she was <strong>the</strong><br />

first African American woman to serve in that role), and as a<br />

frequent instructor <strong>for</strong> judicial education programs around<br />

<strong>the</strong> state, Harbin-Forte has <strong>the</strong> opportunity to teach about<br />

bias and fairness. “I try to teach ways <strong>the</strong>y [judges on <strong>the</strong><br />

bench] can communicate fairness, can create an atmosphere<br />

of fairness. I try to help educate <strong>the</strong>m about <strong>the</strong> perceptions<br />

that members of <strong>the</strong> community leave <strong>the</strong> courthouse with.”<br />

Harbin-Forte said <strong>the</strong> judiciary is a key focal point <strong>for</strong> fairness<br />

and diversity. “If we can’t do it right in our justice system,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n every o<strong>the</strong>r branch of government is at risk. <strong>The</strong><br />

courts are supposed to be about justice and fairness. If we<br />

can’t achieve some ideals here, <strong>the</strong>n our entire democracy is<br />

at risk.”<br />

All photos by Jim Block, except as noted.<br />

THE BAR ASSOCIATION OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO ATTORNEY 29