download baltimore instruction manual

download baltimore instruction manual

download baltimore instruction manual

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

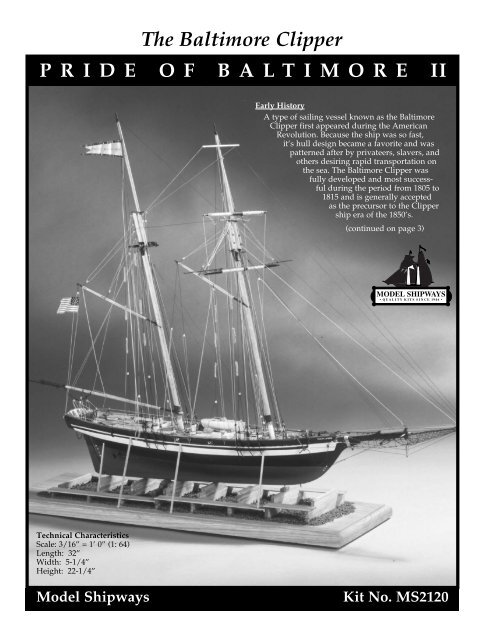

The Baltimore Clipper<br />

PRIDE OF BALTIMORE II<br />

Early History<br />

A type of sailing vessel known as the Baltimore<br />

Clipper first appeared during the American<br />

Revolution. Because the ship was so fast,<br />

it’s hull design became a favorite and was<br />

patterned after by privateers, slavers, and<br />

others desiring rapid transportation on<br />

the sea. The Baltimore Clipper was<br />

fully developed and most successful<br />

during the period from 1805 to<br />

1815 and is generally accepted<br />

as the precursor to the Clipper<br />

ship era of the 1850’s.<br />

(continued on page 3)<br />

Technical Characteristics<br />

Scale: 3/16” = 1’ 0” (1: 64)<br />

Length: 32”<br />

Width: 5-1/4”<br />

Height: 22-1/4”<br />

Model Shipways<br />

Kit No. MS2120

Instruction Manual<br />

The Baltimore Clipper<br />

Pride of Baltimore II<br />

1988<br />

By Ben Lankford, 1994<br />

Built-up Model by Bob Bruetsch, 1994<br />

Detail photos of actual ship by Bob Bruetsch, 1994<br />

The Model Shipways plans for Pride of Baltimore II were prepared in 1993<br />

and 1994. They were developed from the original design drawings for the ship by<br />

Naval Architect Thomas C. Gillmer. Mr. Gillmer was also the designer of the first<br />

Pride of Baltimore, and other replica ships such as the pungy, Lady Maryland, and<br />

the brig, Peggy Stewart.<br />

In addition to the design drawings, the Model Shipways plans incorporate<br />

current as-built details of the ship. A number of modifications were made to the<br />

original design drawings during construction, and even during the period following<br />

construction. Photographs were taken, and detailed measurements were<br />

made to assure an accurate representation of the ship in Baltimore, Maryland. The<br />

plans represent the ship as it appeared from October 1993 to April 1994.<br />

Model Shipways is indebted to Mr. W. Bruce Quackenbush, Jr., Executive<br />

Director of the Pride of Baltimore, Inc. ; Mr. Michael McGeady, Deputy Director;<br />

and Captains Jan Miles and Robert Glover. These people not only encouraged the<br />

project, but assisted with taking measurements off the ship, made numerous<br />

sketches of details, and provided descriptions of the various rigs and operations.<br />

With the ship continually on the move around the world, the project could not<br />

have been completed without their assistance.<br />

Copyright 1994<br />

Model Shipways, a division of Model Expo, Inc.<br />

Tobyhanna, PA 18466-1000<br />

4

(Continued from cover)<br />

It was as a privateer during the War of 1812 that the Baltimore<br />

Clipper became most famous. With sleek lines and few guns, the<br />

Baltimore Clippers were light and exceptionally fast. Their maneuverability<br />

made it possible to wreak havoc on the British; the<br />

speedy privateers could overtake and outrun the enemy with ease,<br />

and this enabled the privateering owners to take large profits from<br />

the many prizes they seized. When the war ended in 1815 with the<br />

Treaty of Ghent, the ship type began to diminish. Many of the<br />

schooners were sold to South American and Caribbean owners. By<br />

1860, the Baltimore Clipper was gone.<br />

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the waterways of the Chesapeake<br />

Bay provided an excellent home and work environment<br />

for the early settlers. The overseas demand for tobacco and new<br />

ships kept the area alive with commerce. Many talented shipwrights<br />

plied their trade at the numerous shipyards located on<br />

the Eastern Shore. One in particular, Thomas Kemp, departed for<br />

Baltimore and Fells Point in 1803 to seek his fortune and avoid<br />

the local competition. Establishing himself as a leader, he built<br />

many fast and notorious Baltimore Clippers. With the newly<br />

independent America’s need to establish itself in European trade,<br />

and develop militarily on the open seas, his success was immediate,<br />

and paved the way for others who migrated north. Because<br />

Baltimore had the investment capital, it could provide the higher<br />

wages that eventually drew the best builders and craftsmen, as<br />

well as the many excellent captains and sailors required to man<br />

the ships. With the turning away from shipping tobacco to the<br />

major export of flour, Baltimore became one of the most productive<br />

shipbuilding and shipping centers of the time.<br />

Although the ship type had been fully developed, the name Baltimore<br />

Clipper was not applied to it until the ship was almost<br />

extinct. The type was once called a Baltimore Flyer, and early<br />

records simply refer to it as a Virginia-Built Boat, or Fast Sailing<br />

Schooner: light and sleek, fast and seaworthy, it was a topsail<br />

schooner with extremely raked masts. It had a wide, flush deck<br />

to allow easy handling of the ship, and when fitted as a privateer,<br />

it had guns. The type seems to have developed from the<br />

Chesapeake Bay sloop, soon found to be too small.<br />

The Baltimore Clipper carved out a place for itself in history. The<br />

schooners facilitated the nation’s ability to win independence,<br />

and they helped the city of Baltimore establish its identity as a<br />

major shipbuilding center.<br />

The First Pride of Baltimore<br />

In 1974, officials from the City of Baltimore wanted to re-create a<br />

Baltimore Clipper as a means of providing public attraction to<br />

the Inner Harbor. They required that the craft be an authentic<br />

replication of an early 19th century Baltimore Clipper, and that it<br />

be built on location at the Inner Harbor waterfront.<br />

Thomas C. Gillmer, a noted author, historian, and former director<br />

of Naval Architecture for the U.S. Naval Academy in<br />

Annapolis, was hired as the designer. The bid for construction<br />

was won by the International Historical Watercraft Society, a corporate<br />

designation of Mr. Melbourne Smith of Annapolis, Maryland.<br />

Mr. Smith is a noted authority on Baltimore Clippers.<br />

The ship’s design was based on early drawings done in Britain<br />

during dockyard surveys after the war of 1812. The plans were of<br />

several original ships that were captured privateers. After reviewing<br />

them, it was decided that Baltimore’s ship would be 90 feet in<br />

overall length with a 23-foot extreme beam, adding up to 140 tons.<br />

In late 1976, the ship was officially<br />

named the Pride of Baltimore,<br />

taking it’s name from the nickname<br />

affectionately given to the<br />

famous Baltimore Clipper, Chasseur.<br />

The Chasseur was built in<br />

1813 at Fells Point in Baltimore<br />

by Thomas Kemp. (Note: the<br />

ship’s boat on the Pride of Baltimore<br />

II carries the name Chasseur.)<br />

Ship’s boat Chasseur<br />

The Pride of Baltimore was launched at Inner Harbor on February 27,<br />

1977 and sailed on May 1, 1977. The ship logged over 150,000<br />

miles sailing to and from such places as the Great Lakes, Spain,<br />

Europe and from Newfoundland to the Florida keys, and many<br />

other ports. On May 14, 1986, the Pride of Baltimore met hurricane<br />

winds on its return home from St. Thomas and was lost at sea<br />

along with four crew members.<br />

Pride of Baltimore II<br />

After a period of mourning, it was decided to replace the Pride<br />

of Baltimore. Late in 1986, Thomas Gillmer once again was<br />

hired as the designer. The contracted builder was G. Peter<br />

Boudreau, a shipwright, crew member, and a captain of the<br />

first Pride of Baltimore.<br />

Pride of Baltimore II was to be a larger ship: 108 feet overall with a<br />

26-foot beam, and weighing 197 tons. Among these and other differences,<br />

this schooner would have a greater cruising radius and<br />

be licensed by the Coast Guard for carrying passengers.<br />

The Pride of Baltimore II keel was laid on May 3, 1987 and the<br />

schooner was launched on April 30, 1988. It was commissioned on<br />

October 23 and on January 3, 1989 received full certification and<br />

put out to sea. Since then, the ship has sailed to many ports. The<br />

schooner’s permanent home is Inner Harbor, Baltimore, Maryland.<br />

While the Pride of Baltimore II is as authentic as possible, a few variations<br />

in design were required to meet today’s standards of economy<br />

and safety. Interior watertight bulkheads were provided for<br />

safety, and the ship was fitted with auxiliary engines and feathering<br />

props. These were required because of the busy ports the ship<br />

is scheduled to visit. The ship also has a steering wheel instead of<br />

a tiller arm typical of a 19th century ship. If fitted with a tiller arm,<br />

the Coast Guard would require a two-helmsman watch. To do this,<br />

the crew would have to be increased by four which was unacceptable<br />

to officials. Also, it was decided not to include a fore course<br />

on the foremast. Such a sail was probably carried on Baltimore<br />

Clippers of the past, but was only used in light wind conditions.<br />

This sail plan decision was made during the building of the first<br />

Pride of Baltimore.<br />

If fitted as a privateer, the Pride of Baltimore II would have to carry<br />

guns. So, the ship design included ten gun ports with five on each<br />

side. Simply for show, the schooner carries four large cannons and<br />

two small swivel guns.<br />

More History<br />

For a complete history of the Baltimore Clippers, and both the<br />

Pride of Baltimore and Pride of Baltimore II, consult the<br />

bibliography for some excellent books with many good<br />

photographs and drawings.<br />

5

CONSTRUCTION STAGES AND TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Brief History Cover, pg 3<br />

Introduction/Credits Pg 4<br />

Before You Begin Pg 7<br />

What You’ll Need to Start Construction Pg 7<br />

How to Work With the Plans & Parts Pg 8<br />

Painting & Staining the Model Pg 9<br />

Stage A: Framing the Plank-On-Bulkhead Hull Pg 10<br />

1. Bending Wood Pg 10<br />

2. Center Keel Assembly Pg 10<br />

3. Cutting the Rabbet Pg 10<br />

4. Installing the Keel/Stem & Sternpost Pg 11<br />

5. Installing the Bulkheads Pg 11<br />

6. Installing the Transom Framing Pg 12<br />

7. Covering the Mast Slots Pg 12<br />

8. Installing the Planksheer & Bulwark Stanchions Pg 12<br />

9. Installing the Hawse Timbers Pg 13<br />

10. Installing the Main Rail Pg 13<br />

Stage B: Planking the Plank-On-Bulkhead Hull Pg 14<br />

1. Getting Started Pg 14<br />

2. Planking Battens & Belts Pg 14<br />

3. Planking Butts Pg 14<br />

4. Spiling Pg 15<br />

5. Fastening the Planks Pg 15<br />

6. Planking the Outer Hull Pg 15<br />

7. Planking the Transom & Counter Pg 18<br />

8. Planking the Bulwarks Pg 18<br />

9. Planking the Deck Pg 19<br />

Stage C: Completing the Basic Hull Structure Pg 20<br />

1. Correcting & Sanding Pg 20<br />

2. Gunport Lids & Interior Rail Pg 20<br />

3. Swivel Gun Stocks Pg 20<br />

4. Natural Wood/Double Plank Option Pg 20<br />

Stage D: Mounting the Hull Pg 21<br />

1. Building-Ways Pg 21<br />

2. Mounting Board with Two Pedestals Pg 21<br />

Stage E: Adding the Hull Details Pg 21<br />

1. Locating Deck Fittings & Structures Pg 21<br />

2. Bow Fairlead Pg 21<br />

3. Cabin Trunks Pg 21<br />

4. Ventilator Boxes & Mushroom Vents Pg 22<br />

5. Binnacle Pg 22<br />

6. Steering Wheel & Box Pg 22<br />

7. Hatches Pg 22<br />

8. Deck Lockers Pg 24<br />

9. Samson Post & Bitts Pg 24<br />

10. Windlass & Chain Pipes Pg 24<br />

11. Catheads & Anchors Pg 24<br />

12. Pin Rails Pg 25<br />

13. Fife Rails Pg 25<br />

14. Bilge Pumps & Fire Stations Pg 25<br />

15. Deck Prisms Pg 25<br />

16. Rubber Pads Pg 25<br />

17. Steps Pg 26<br />

18. Lifelines Pg 26<br />

19. Life Rings Pg 26<br />

20. Cavels & Mooring Chocks Pg 26<br />

21. Channels Pg 26<br />

22. Eyebolts & Cleats Pg 26<br />

23. Props & Struts Pg 27<br />

24. Rudder Pg 27<br />

25. Swivel Guns Pg 27<br />

26. Cannons Pg 27<br />

27. Ship’s Bell Pg 27<br />

28. Running Lights, Stern Light & Crosstree Spotlights Pg 27<br />

29. Stern Flag Emblem Pg 27<br />

30. Ship’s Name Pg 28<br />

31. Ship’s Boat & Cradles Pg 28<br />

Stage F: Mast & Spar Construction Pg 29<br />

1. The Importance of Scale Pg 29<br />

2. Shaping & Tapering Masts & Spars Pg 29<br />

3. Building & Installing the Masts Pg 29<br />

4. Building & Installing the Bowsprit, Jibboom,<br />

Dolphin Striker & Jibboom Spreaders Pg 31<br />

5. Building the Fore Yards Pg 31<br />

6. Building the Main Boom & Gaffs Pg 32<br />

7. Ringtail & Studding Sail Booms & Yards Pg 32<br />

Stage G: General Rigging & Sailmaking Information Pg 33<br />

Rigging Terms Defined Pg 33<br />

1. Rigging Options Pg 33<br />

2. Using the Rigging Plans Pg 34<br />

3. Rigging Line Sizes & Colors Pg 34<br />

4. Wire vs. Rope Rigging Line Pg 34<br />

5. Treating the Lines Pg 34<br />

6. Belaying Pins & Their Lines Pg 34<br />

7. Rigging Tools Pg 36<br />

8. Blocks & Deadeyes Pg 36<br />

9. Sailmaking Pg 36<br />

10. Rigging the Model Without Sails Pg 37<br />

Stage H: Standing Rigging Pg 38<br />

1. Shrouds Pg 38<br />

2. Backstays Pg 38<br />

3. Running Backstays Pg 38<br />

4. Fore & Aft Stays Pg 39<br />

5. Bowsprit Rigging Pg 39<br />

6. Footropes & Studding Sail/Ringtail Lashings Pg 39<br />

Stage I: Running Rigging Pg 40<br />

1. Jib Topsail, Jib & Fore Staysail Pg 40<br />

2. Foresail Pg 40<br />

3. Mainsail Pg 40<br />

4. Ringtail Pg 40<br />

5. Main Gaff Staysail Pg 41<br />

6. Fore Topsail & Lower Yard Pg 41<br />

7. Studding Sails Pg 42<br />

8. Fore Topgallant Sail Pg 42<br />

9. Miscellaneous Rigging Pg 42<br />

10. Final Touches Pg 43<br />

Bibliography Pg 44<br />

Rigging Line Diameters Pg 44<br />

Scale Conversion Table Pg 44<br />

Millimeter/Inches Conversion Formula Pg 44<br />

6

BEFORE YOU BEGIN<br />

The Pride of Baltimore II is a very beautiful schooner and makes a<br />

splendid model. The plank-on-bulkhead hull construction with<br />

laser-cut parts offers a unique building experience. It assures an<br />

accurate hull form, and develops an understanding of how real ships<br />

are constructed.<br />

The kit is manufactured to a scale of 3/16” = 1’ 0” and reflects the<br />

scale of the plans. The kit is supplied with a set of Britannia, brass,<br />

and wooden fittings to eliminate problems in making or machining<br />

such parts from scratch, which may be beyond the ability or<br />

resources of the average modeler. Many of these fittings, however,<br />

will require final finishing before they are suitable for installation on<br />

the model. This will be especially true for the Britannia fittings and<br />

will be discussed later.<br />

This kit will provide less experienced modelers with the opportunity<br />

to acquire some scratch-building techniques. As an aid, various<br />

techniques will appear throughout the <strong>instruction</strong>s. While the modeling<br />

progresses, you will see where you may want to substitute<br />

some of the kit fittings with your own creations. By all means try<br />

them, especially if you think you can improve the model. The worst<br />

that can happen is a little lost time. But, the experience gained will be<br />

most valuable for future projects.<br />

If you are a beginner, take your time. This model has a considerable<br />

amount of detail and small parts. Make sure you complete one<br />

stage before moving to the next. When things go awry, consider<br />

doing it over.<br />

WHAT YOU’LL NEED TO START CONSTRUCTION<br />

The following tools and supplies are recommended for the construction<br />

process. Modelers who have built before may have their<br />

own favorites.<br />

A. Knives<br />

1. Hobby knife<br />

2. No. 11 blades<br />

B. Files<br />

Set of needle files<br />

C. Clamps<br />

1. A few small C-clamps<br />

2. Wooden clothespins<br />

3. Rubber bands, #16 and #33<br />

D. Tool Set<br />

A small carving tool set or individual gouges and chisels for carving<br />

center keel rabbets, stern filler pieces, tapering the keel/stem,<br />

and carving the ship’s boat.<br />

E. Sharpening Stone<br />

Necessary to keep tools razor sharp<br />

F. Boring Tools<br />

1. Set of miniature drills: #60 to #80<br />

2. 1/16”, 3/32”, and 1/8” drills<br />

3. Pin vise<br />

G. Miscellaneous<br />

1. Tack hammer<br />

2. Tweezers (a few)<br />

3. Small fine-pointed scissors<br />

4. Miniature pliers (small round and flat nose)<br />

5. Bench vise (small)<br />

6. Soldering iron or torch, solder and flux<br />

7. Sewing thread (black and tan for seizing)<br />

8. Beeswax block (for treating rigging lines)<br />

9. 1/2” or 3/4” masking tape<br />

10. Wire cutters (for cutting fine wire and strip metal)<br />

H. Sandpaper<br />

Fine and medium grit garnet or aluminum oxide sandpaper<br />

(#100 to #220)<br />

I. Sail cloth<br />

Light weave cotton, linen, or balooner cloth, if you intend to<br />

add sails. Model Expo carries a suitable fine weave 100% cotton<br />

muslin which is unbleached and doesn’t need dyeing.<br />

J. Finishing<br />

1. Paint Brushes<br />

a. fine point for details<br />

b. 1/4” to 1/2” flat square for hull<br />

K. Supplies<br />

(will be covered in detail in the Painting & Staining section<br />

and throughout the <strong>instruction</strong>s)<br />

1. Paints<br />

2. Primer<br />

3. Stains and varnish<br />

4. White or Carpenter’s (yellow) wood glue<br />

5. Super glue<br />

6. Five-minute epoxy glue<br />

7. Wood filler<br />

Note about glues: White glue, or Carpenter’s wood glue (yellow<br />

in color; also available in tan), will suffice for most of the model.<br />

Five-minute epoxy provides extra strength for gluing fittings.<br />

Cyanoacrylate glue (super glue), such as Jet, can be used for quick<br />

adhesion and is ideal for adding a touch to a rigging seizing to<br />

hold it in place. The best super glue for most applications is a<br />

medium viscosity gap-filling type. The watery thin type is recommended<br />

to fill a narrow crack by capillary action, and for quickly<br />

securing hull planking to the bulkheads.<br />

7

HOW TO WORK WITH THE PLANS & PARTS<br />

Before starting model construction, examine the kit and study the<br />

plans carefully. Familiarizing yourself with the kit will serve two<br />

purposes. First, it will let you determine that all parts have been<br />

supplied as listed. And second, you’ll be surprised at just how<br />

quickly handling the parts allows you to better understand the kit<br />

requirements. Try to visualize how every part will look on the<br />

completed model. Also, determine ahead of time what must be<br />

done first. The <strong>instruction</strong>s will help you in this regard, but a thorough<br />

knowledge of the plans at the outset is essential.<br />

It is suggested that all small fittings and hardware be sorted into<br />

labeled boxes or compartments to avoid loss during the building<br />

process.<br />

1. The Plans<br />

Six Plan Sheets are provided:<br />

1. Plank-On-Bulkhead Hull Patterns - Sheet 1 of 6<br />

2. Plank-On-Bulkhead Hull Construction - Sheet 2 of 6<br />

3. Hull Plan and Profiles - Sheet 3 of 6<br />

4. Hull and Spar Details - Sheet 4 of 6<br />

5. Rigging and Sails - Sheet 5 of 6<br />

6. Rigging Sections and Details - Sheet 6 of 6<br />

In addition, a set of sketches appears throughout the <strong>instruction</strong><br />

<strong>manual</strong> to further illustrate the various stages of construction.<br />

The Pride of Baltimore II kit is manufactured to a scale of 3/16” = 1’ 0”.<br />

Each plan sheet is drawn to the exact scale that the model is to be<br />

built, except where some details have been enlarged for clarity.<br />

Most often, a clarifying detail is twice as large as the model scale;<br />

3/8” = 1’ 0”. Most dimensions can be lifted directly off the plans by<br />

using a set of draftsman dividers or by using a “tick” strip, which<br />

is simply a piece of paper used to “pick up” the dimensions (a roll<br />

of calculator tape works very well). Lay your paper strip over the<br />

plan and mark the lengths of items carefully with a sharp pencil.<br />

Then use the strip to transfer the marks to the wood or item to be<br />

made to scale. When ticking the larger scale details, just cut the<br />

measurement in half.<br />

It is handy to have a triangular architect’s scale. Measuring and<br />

cutting parts using the 3/16” scale gives you a better feel for real<br />

ship sizes. You would need this scale for building a model with full<br />

ship sizes shown on the plans. However, the Pride of Baltimore II<br />

plans have already been converted and show only actual model<br />

sizes. Actual sizes were converted to the nearest 1/64”, or 1” full<br />

scale. Consequently, you will be working in increments of 1/64”.<br />

For example, if the actual size was 2-1/2” (or 5/128” model scale)<br />

it has been rounded up to 3/64”; close enough at this scale and it<br />

better fits the standard basswood sizes.<br />

2. Making Allowances Along the Way<br />

Try to be exact when following the plans, but use common sense<br />

along the way. You may need to make adjustments or allow for<br />

small differences in how your model is shaping up; perhaps your<br />

mast has too much rake (the angle at which it sits). When lines go<br />

to belaying points they should not drape over parts or conflict with<br />

other lines. If necessary, move a belaying point or a fairlead. In<br />

other words, put yourself on the ship and use your judgement.<br />

3. Understanding Hull Lines<br />

Beginners may not be familiar with hull lines. Buttock lines are vertical<br />

longitudinal planes cut through the hull. Waterlines are horizontal<br />

planes, and sections are transverse vertical planes. All of<br />

these lines define the hull shape and are used by the draftsman to<br />

fair the hull form (create regular even curves).<br />

A complete set of hull lines is not shown on the plans because they<br />

are not needed for this particular model. With the plank-on-bulkhead<br />

construction, the laser-cut bulkheads and center keel define<br />

the hull form. These are based on the Pride of Baltimore II designer<br />

hull lines to the outside of the planking, but are made smaller to<br />

allow for the thickness created by adding the planks. The Hull<br />

Planking Layout on Sheet 2 shows all the bulkhead lines together<br />

which are similar to a lines drawing body plan that shows the sections.<br />

Consult these lines when it is necessary to determine the<br />

hull form slopes. This will be necessary when installing the bulwarks<br />

since the bulwark stanchions are built separately from the<br />

lower bulkheads.<br />

4. Using Basswood Lumber<br />

Standard cut basswood is available in sheets and strips. Normally,<br />

thicknesses are available in 1/32”, 1/16”, 3/32”, 1/8”, 5/32”,<br />

3/16”, 1/4”, and 1/2”. Widths of strips are available in the same<br />

increments. Sheets may be 1”, 2”, 3”, or 4”. A thickness of 3/64” is<br />

a manufactured thickness, but not found in many catalogs. It is<br />

being supplied in this kit because it is needed for full-size ship<br />

thicknesses of 3”, as is the case for the main rail.<br />

Note: Your kit will contain either U. S. grown basswood or European<br />

limewood. Lime is similar to and just as good a model wood<br />

as our well-known basswood. In fact, it has superior steam bending<br />

qualities to basswood. Both woods are a similar species from<br />

trees called lime and linden. Limewood is often called basswood<br />

in Europe.<br />

For the model scale 3/16” = 1’ 0”, 1/64” is equal to 1” full ship<br />

size. 1/32” is equal to 2”, and so on. Generally, the available sizes<br />

of basswood fit the full ship size quite well and the strips or sheets<br />

can be used directly. Occasionally, you will find a size where the<br />

strip must be thinner than the basswood size supplied. In order to<br />

use a correct thickness, you will need to sand down a certain<br />

thickness of basswood. This is easily done with a sanding block<br />

before making a part.<br />

If you are fortunate enough to own a powered sanding thickness<br />

planer for models, all the better. These can be purchased commercially.<br />

You can also make your own, using a drum sander in a<br />

drill press. Clamp a block alongside the sander so the wood can<br />

be inserted between the block and sander. It’s a makeshift deal,<br />

but it works quite well.<br />

A thickness of 1/64” is required for many parts in this kit. Birch<br />

aircraft three-ply plywood could be used for this thickness. However,<br />

since it is birch, not basswood, it will not stain exactly the<br />

same as basswood. There is a lot of staining to be done, so it is<br />

preferable to stick with basswood so that the color will be uniform.<br />

Just bite the bullet and sand a 1/32” piece down to 1/64”.<br />

It is a good idea to sort the wood contained in the kit by thickness.<br />

When building a certain part, select a suitable size from the proper<br />

thickness pile. After cutting what you need, return the remaining<br />

piece to that thickness pile. This saves a lot of time looking for<br />

a given thickness. Don’t worry about using a piece for one item<br />

that was intended for another. It will all come out in the wash.<br />

There is enough extra wood in the kit so you should not run out<br />

before you complete the model.<br />

5. Cast-Metal Fittings<br />

The kit is supplied with Britannia metal castings. The Britannia<br />

metal is a great improvement over the white metal that was used<br />

in some older kits. Unlike white metal and pewter, Britannia does<br />

not contain lead, so there are no possible corrosion problems.<br />

Many of these fittings, however, will require final finishing before<br />

they are suitable for installing on the model.<br />

8

Before painting the cast-metal fittings, clean them up by<br />

removing all the mold-joint flash. To do this, use a No. 11<br />

hobby blade to cut the flash, then file or sand with fine sandpaper.<br />

It is also suggested that you clean the fittings thoroughly<br />

with warm soapy water before applying primer.<br />

Make sure they are rinsed thoroughly and allowed to dry<br />

before painting.<br />

6. Soldering & Working with Brass<br />

The Pride of Baltimore II is a replica ship of a period that had<br />

very little iron fittings. Consequently, you will not be<br />

required to do much soldering. Many of the fittings are cast<br />

Britannia. However, some items are difficult to cast or would<br />

be too soft, so these items must be made from brass strip and<br />

wire. Here are a few tips on soldering those or items you<br />

decide to scratch build.<br />

Brass sheet and strips can be cut with a small pair of tin snips<br />

or heavy scissors. Heavier brass will require the use of a jeweler’s<br />

saw. After cutting, all edges should be smoothed with<br />

needle files and fine wet-or-dry sandpaper. When cutting<br />

slivers from the brass sheet, you may notice that shears tend<br />

to bend the sheet sideways, as well as curl the piece. To<br />

straighten the edges in both directions, grip them with a pair<br />

of small pliers.<br />

Drilling holes in brass can be accomplished using small drills<br />

and a pin vise, which is a slow process. A Dremel Moto-Tool<br />

mounted on a Dremel drill press is ideal. This tool is worth<br />

the cost. Prior to drilling, use a small centerpunch to start;<br />

otherwise, these small drills tend to wander. Lubricate with a<br />

light oil and drill very slowly to avoid breakage. When using<br />

the Dremel, clamp the pieces in place or hold them down<br />

with a stick of wood. The brass will be very hot, so keep your<br />

fingers off!<br />

Soldering: The key here is to keep all brass parts clean. Use a<br />

solvent, or lightly sand, or both. Keep your fingers off to<br />

avoid grease spots. Soldering is easy if care is taken to set up<br />

your work area properly first. Use jigs or other holding<br />

devices, so the parts do not move around. Soldering can be<br />

done with a small torch or pencil soldering iron. First, add<br />

flux to the joint; just enough to do the job. The solder will flow<br />

where the flux is applied. Next, heat the joint.<br />

This sequence is important. The larger the parts, the longer it<br />

will take to heat the brass before the solder will flow. If you<br />

get too much solder on the joint, file it off with needle files.<br />

You’ll want the joint to look like the real thing, not a big glob<br />

of fillets.<br />

Solder: Today, there are many lead-free solders available and<br />

they are very strong. There is not much need to use pure silver<br />

solder. It is much more difficult to use because of the high<br />

melting temperature. Some of the lead-free solders have a<br />

small percentage of silver in the composition but the melting<br />

temperature is low.<br />

PAINTING & STAINING THE MODEL<br />

It may seem strange to begin an <strong>instruction</strong> <strong>manual</strong> with directions<br />

on applying the finishes to the model. Not so! Much time<br />

and effort can be saved, and a more professional result can be<br />

obtained, if the finishing process is carried out during construction.<br />

Proper timing in application of finishes and the use of masking<br />

tape to define painted edges should eliminate unsightly glue<br />

marks and splotchy stained surfaces. In the end, following these<br />

general suggestions will be to your advantage.<br />

Paint:<br />

Use a flat-finish paint such as the excellent model paints made<br />

by Model Shipways. You could<br />

also use artist’s paints by Jo Sonja (used by many bird carvers)<br />

or Holbein Acryla Gouache. These paints are a combination<br />

acrylic-gouache.<br />

Paint colors:<br />

The color scheme used for the Pride of Baltimore II is given on the<br />

plans. You will see color notes such as “color A.” In a notes column<br />

on plan sheet 3, the color A is described. In order to convey<br />

a more accurate color, commercial Floquil ship model or railroad<br />

model colors and stains, and Minwax stains are referenced. A<br />

color was selected as close as possible to the real ship colors.<br />

If you use a paint other than Model Shipways, match the Model<br />

Shipways color referenced on the plans with the paint you select,<br />

or get as close as you can.<br />

Primer:<br />

Use a grey primer. Model Shipways brand is excellent. The grey<br />

color will highlight sanding scratches and other defects better<br />

than white primer. Prime all woodwork to be painted, and prime<br />

all metal fittings. Lightly sand the primed items. Use a spackling<br />

compound, such as Pic-n-Patch brand, to fill any scratches and<br />

defects, then re-prime. Careful! Do not prime parts to be stained<br />

or varnished.<br />

Stains & Finishes:<br />

For natural finished wood, use a protective coating after staining,<br />

such as low sheen polyurethane varnish or the Floquil coatings.<br />

You can also use an oil-resin mix such as natural Minwax. Model<br />

Shipways stain, or Minwax stains can be used to tone the wood.<br />

Brushes & Procedures:<br />

Use good quality soft sable or synthetic hair artist brushes. A<br />

small pointed brush is good for details. For the main hull areas,<br />

use a 1/4 to 1/2 inch flat brush.<br />

Before painting, clean the model with a tack rag. Apply your<br />

paint in smooth even strokes, overlapping the strokes as you go.<br />

Thin the paint enough to eliminate brush strokes, but not run.<br />

You will need four or five coats of the light colors to cover the<br />

grey primer, and maybe only two coats of the dark. Check your<br />

finish between coats, and sand or add spackle as necessary to get<br />

rid of any blemishes.<br />

You will be told how to mark the load waterline location later.<br />

At this line, and anywhere else two colors meet, use masking<br />

tape. Electrician’s black plastic tape is ideal. It leaves a nice edge<br />

and is not overly sticky. Do not use drafting tape. The edges are<br />

wrinkled and paint may run under the edge.<br />

9

STAGE A<br />

FRAMING THE PLANK-ON-BULKHEAD HULL<br />

1. Bending Wood<br />

Building a P-O-B hull requires some wood bending<br />

and twisting, and the wood must remain in the<br />

desired position so as not to put too much stress on<br />

glue joints and fasteners. The term “steam-bent” will<br />

be used throughout the text whenever such a process<br />

is necessary. However, here are three ways to do it.<br />

Steam-bending–For actual steam-bending, hold the<br />

piece over a kettle of steaming water and bend. Hold<br />

the wood in position until it cools. It should remain<br />

nearly in that position, but may spring back slightly.<br />

Soaking–Another method is to soak the piece in<br />

warm water for several hours. Try adding a little<br />

household ammonia to the water. You can also use<br />

pure ammonia. This speeds up the soaking process<br />

and makes the wood fibers slippery so the wood is<br />

easily bent. Hold the wood in position with a form<br />

after soaking and let it dry completely.<br />

Hot iron–You may also bend wood quickly over a<br />

soldering iron, but don’t let it get too hot. A large soldering<br />

iron with a tubular end is ideal. The tube near<br />

the handle is not as hot as the very end. It is also possible<br />

to purchase model plank bending irons commercially.<br />

They are designed for controlled heat.<br />

2. Center Keel Assembly<br />

The first step in constructing the hull is to assemble<br />

the two laser-cut center keel pieces. First, use a sharp<br />

pencil and mark the bulkhead locations below the<br />

slots and the WL reference lines. One line is used to<br />

locate Bulkheads “A” through “L” and another for<br />

locating Bulkhead “M”. Mark on both sides of each<br />

center keel piece. Be especially critical in locating the<br />

reference lines. Measure from several points from the<br />

plans. The reference lines are a key to proper alignment.<br />

Place the two parts, 1 and 2, over a sheet of wax<br />

paper or plastic wrap, on a flat building board or<br />

table. Glue the joint with white or carpenter’s wood<br />

glue. Use a steel or aluminum straight edge to align<br />

the WL reference lines. Place a weight on each piece<br />

to hold it down while the glue dries. Let the glue dry<br />

at least overnight, preferably 24 hours (see figure 1).<br />

3. Cutting the Rabbet<br />

Cut the rabbet in the center keel. The bearding line is<br />

the intersection of the center keel and the inside face<br />

of hull planks. After the center keel is ready, mark the<br />

bearding line on both sides. The bearding line<br />

appears along the sternpost and the keel/stem. Measure<br />

from the P-O-B plans. Using a chisel, start the<br />

rabbet cut at the bearding line and cut toward the<br />

edge of the center keel. When the planking is<br />

installed, the planks will lie flush on the cut portion<br />

from bearding line to rabbet (see figure 2).<br />

10

4. Installing the Keel/Stem & Sternpost<br />

The ship has no real point of change between the keel<br />

and stem, so we will call it a keel/stem. The laser-cut<br />

keel/stem, and sternpost can now be added. Taper<br />

the keel/stem according to the plans before gluing in<br />

place or do it later. Dowels can be used to help align<br />

and hold the pieces. Remove any glue squeeze-out<br />

from the rabbet before it sets (see figure 3).<br />

An Option: If you like, you can glue the sternpost and<br />

keel/stem onto the center keel before cutting the rabbet.<br />

This makes cutting the rabbet a little more difficult,<br />

but on the other hand, it makes the installation<br />

of the sternpost and keel/stem easier since there is<br />

more gluing surface.<br />

5. Installing the Bulkheads<br />

The bulkheads are labeled “A” through “M”. Compare<br />

the laser-cut bulkheads with the plans to determine<br />

which is which, and label each bulkhead. Check<br />

each bulkhead to make sure it will slide into the center<br />

keel slots. Machine tolerances during laser cutting<br />

may provide a too tight fit. Sand the slots, if necessary,<br />

until the bulkheads slip on. The fit should be<br />

snug, allowing a little tolerance for glue.<br />

On each bulkhead, mark the location of the WL reference<br />

lines in pencil. This mark should line up with<br />

the WL mark on the center keel. It will assure that the<br />

hull form is accurate and that each bulkhead is correctly<br />

related to the others. There are two WL marks.<br />

One is for Bulkhead “A” through “L”, and the other<br />

is a higher mark for Bulkhead “M”.<br />

Next, mark the bevels on the bulkheads. Use a tick strip<br />

to transfer the bevel line as shown on the plans, or cut<br />

the bulkhead patterns from the plan and glue onto the<br />

bulkheads. You can also lay the pattern over the bulkhead<br />

and use a pin prick to locate the bevel. Cut the<br />

bevels with a #11 blade as shown (see figure 4).<br />

Some of the bevels are very slight, especially the deck<br />

bevels and the side bevels near amidships. These can<br />

be sanded after the bulkheads are installed instead of<br />

pre-cutting them.<br />

Glue the bulkheads in place, making sure that the<br />

WL marks on the bulkheads and the center keel line<br />

up. Use a square to make each bulkhead perpendicular<br />

to the center keel, then tack a temporary strip to<br />

the top to hold the bulkhead in place while the glue<br />

dries (see figure 5).<br />

After all bulkheads are in place, tack a temporary batten<br />

on each side of the hull just below the deck as<br />

shown. (see figure 6). This is a critical step. Measure<br />

the spacing between bulkheads and retack the battens<br />

until the hull is aligned. Even though the center<br />

keel was assembled flat, it could warp out of line. The<br />

result could be that you end up with a bananashaped<br />

hull. Check the spacing between bulkheads,<br />

and the port against starboard spacing. Look at the<br />

the hull to see if it is properly aligned.<br />

When you are satisfied that the hull is aligned, check<br />

to see that the bottom of each bulkhead feathers out<br />

and lies precisely on the bearding line. Trim as necessary<br />

to line up. Also, check to make sure that the<br />

top of each bulkhead at the centerline is flush or<br />

slightly higher than the center keel. Since all alignment<br />

is based on the WL marks, there could be some<br />

slight errors. If the center keel is below the top of the<br />

bulkheads, that’s OK. If above, trim the center keel<br />

until it is flush with the bulkheads (see Figure 7).<br />

FIG. 5 – Squaring the Bulkheads<br />

Reference<br />

lines must<br />

line up<br />

Glue<br />

FIG. 6 – Applying Battens<br />

Check spacings<br />

Bulkheads<br />

REF.<br />

FIG. 7 – Aligning the Bulkheads<br />

Sand flush with top of<br />

bulkheads if necessary<br />

REF.<br />

Check alignment<br />

visually in all<br />

directions<br />

REF.<br />

Smooth flow<br />

into rabbit<br />

Tack temporary<br />

strip until glue dries<br />

Check 90°<br />

with square<br />

Check straightness of center<br />

keel with straight edge<br />

Bearding line<br />

Tack temporary<br />

batten on hull<br />

Line up with reference<br />

line on center keel<br />

Trim if neccessary to line<br />

up on the bearding line<br />

11

Next, check the fairness of the hull form and sand in<br />

the slight bevels that were not pre-cut. To do this, use<br />

a stiff basswood batten about 3/32” thick and lay it<br />

across the bulkhead edges and deck in various locations<br />

(see figure 8). If not fair, sand the bevels that<br />

stick out, or add shim material if there are dips. This<br />

is an important check. The planks must lie flat<br />

against the bulkheads without incurring any bumps<br />

and dips on the surface. A model like the Pride of Baltimore<br />

II has many bulkheads, so it is possible for<br />

manufacturing or assembly errors to creep in.<br />

Critical Area: Planks from Bulkhead “K” to the sternpost<br />

rabbet take a severe bend. The bevel on Bulkhead<br />

“L” is critical. Check this area thoroughly so a<br />

batten curves smoothly from “K” over “L” and into<br />

the sternpost rabbet. Trim “L” if necessary. This area<br />

will require steam-bending. Otherwise, the planks<br />

may break or buckle as they pass over Bulkhead “L”.<br />

Option: To avoid the possibility of a break at “L”, you<br />

could fill the space from bulkhead “L” to the rabbet<br />

with a solid wood block, carved to the hull curvature.<br />

6. Installing the Transom Framing<br />

The transom framing is composed of a filler block<br />

port and starboard that is glued to the aft side of<br />

Bulkhead “M” and to the center keel. On top of the<br />

blocks you will glue six laser-cut inboard knees and<br />

two outboard knees. The outboard knees should<br />

slope inboard and curve on the outboard side to<br />

catch the bulwark planking which will require a lot<br />

of tumblehome aft near the transom.<br />

First, carve the two rectangular blocks provided in<br />

the kit in accordance with the plans (see also figure<br />

9). The top will need to be curved to the deck camber.<br />

The aft side of the blocks indicate the slope and curvature<br />

of the transom, and the counter below should<br />

be a curve, but straight across. Note that the front of<br />

each block will be exactly the same as the aft side of<br />

Bulkhead “M”.<br />

Add the laser-cut frame knees atop the carved blocks<br />

(see figure 10). The inboard knees are straight, but the<br />

outboard knees must be sanded to the hull curvature.<br />

The transom will be planked later. For now, you may<br />

want to tack a strip along the top of the knees so you<br />

won’t accidentally break them off as you proceed.<br />

7. Covering the Mast Slots<br />

On both sides of the mast slots in the center keel, add<br />

the pieces shown on the P-O-B plan. Cut from scrap<br />

wood. Glue them securely, because you can’t get to<br />

them after the decking is installed. The mast slots are<br />

slightly larger than the actual mast. The mast will be<br />

wedged in the hole when installed.<br />

8. Installing the Planksheer<br />

& Bulwark Stanchions<br />

The Pride of Baltimore II has a single planksheer (or<br />

call it a waterway). Inboard of the planksheer is a nibbing<br />

strake running parallel to the planksheer. The<br />

planksheer is provided laser-cut with holes for each<br />

bulwark stanchion. The planksheer is 1/16” thick like<br />

the deck planks. On the real ship, the planksheer is<br />

slightly thicker than the deck planks (about 3/8” to<br />

1/2”) but at 3/16” model scale this variance is not<br />

necessary. The planksheer will be painted, so the difference<br />

will not be seen.<br />

FIG. 8 – Fairing the Hull Form<br />

Needs shim<br />

(gap)<br />

FIG. 9 – Installing the Transom Framing<br />

Stern block<br />

P/S<br />

Transom slope<br />

P/S = Port & Starboard<br />

Needs trimming<br />

(bump)<br />

FIG. 10 – Adding the Frame Knees<br />

Knee (vertical)<br />

Deck camber curve<br />

Glue<br />

Stern block<br />

Good<br />

Good<br />

Heavy batten across<br />

several bulkheads to<br />

check fairness<br />

Counter curve<br />

Glue to “M”<br />

BHD”M”<br />

Temporary strip<br />

to hold knees<br />

Outboard knee<br />

angled inboard<br />

BHD “M”<br />

12

Glue the two-piece planksheer together, then glue it<br />

to the top of the bulkheads, port and starboard. The<br />

planksheer should extend beyond the edge of the<br />

bulkheads by 3/32”. After the hull planking is<br />

added, the planksheer will protrude out from the<br />

planks by 1/32”.<br />

The planksheer across the stern must be fitted<br />

between the stern knees as shown on the plans.<br />

The bulwark stanchions on the real ship are not<br />

extensions of the hull frames, but separate timbers set<br />

between frames. For the model, you will proceed in a<br />

similar manner except that the stanchions will go<br />

only to the bottom of the planksheer. The stanchions<br />

are provided laser-cut in the kit. Notice that the stanchion<br />

at the cathead is 1/8” wide while all others are<br />

3/32”. If for some unknown reason this particular<br />

stanchion was laser-cut like the others, simply add a<br />

piece of 1/32” sheet to the side to make the stanchion<br />

1/8” wide.<br />

The trick now is to install the bulwark stanchions so<br />

that they are properly angled and follow the hull<br />

form. Using the Hull Planking Layout drawing as a<br />

guide, and also paying attention to the shape of the<br />

bulkheads, install and glue a bulwark stanchion<br />

about every three or four inches. Check the angle and<br />

make sure it is exact. Next, insert the remaining stanchions<br />

in the planksheer holes, but before gluing<br />

these in place, add the inboard stringer at the top of<br />

the stanchions. This stringer will act as a guide for<br />

fairing the other stanchions. You may need to put<br />

some temporary strips between the port and starboard<br />

stringer to hold them to the correct shape.<br />

When satisfied with the alignment, add a touch of<br />

super glue at each stanchion to secure them in the<br />

holes (see figure 11).<br />

A stringer is also required at the inboard top of the<br />

stern knees. Glue this on at this time.<br />

Notice on the plans that each stanchion has chamfered<br />

edges on the inboard side. At 3/16” scale, it<br />

may be overkill to try to add these chamfers on the<br />

model. They would be more effective if the stanchions<br />

were made from a harder wood, such as cherry,<br />

and the scale were a little larger.<br />

9. Installing the Hawse Timbers<br />

The hawse timbers will be glued to the top of the<br />

planksheer. Fit the hawse timbers as shown on the<br />

plans (see also figure 12). Drill the hawse holes<br />

through the lower section as shown.<br />

10. Installing the Main Rail<br />

Cut the main rail from 3/64” x 1/2”-wide stock provided<br />

in the kit and according to the plans. Use several<br />

scarf joints in the main rail. Cut each section so<br />

the grain of the wood follows the rail. Fit the rail carefully<br />

on top of the bulwark stanchions. Drill some<br />

holes for alignment pins or dowels before gluing as<br />

shown (see figure 13).<br />

Most of the basic framing is now complete and you<br />

will begin the planking next. First, take a moment to<br />

look over what you have done so far. Re-check the<br />

fairness of the hull. Making corrections now will<br />

allow the planking process go smoothly.<br />

13

14<br />

STAGE B<br />

PLANKING THE PLANK-ON-BULKHEAD HULL<br />

Before getting started, it is a good idea to know some<br />

of the more common shipbuilding terms that apply<br />

to the planking process. Consider the following few<br />

key words as you work:<br />

1. A plank is a single length of wood used for planking<br />

a hull or deck. A planking strake is a continuous<br />

line of planks, butted end to end from bow to stern,<br />

or wherever the strake begins and ends.<br />

2. A garboard strake is that strake of planking adjacent<br />

to the keel.<br />

3. The sheer strake is the uppermost main hull strake.<br />

4. The wale is a heavy layer of strakes below the sheer<br />

strake along the length of the hull’s side.<br />

5. When discussing planking belts, we are talking<br />

about a group of planks along the hull. Belts are laid<br />

out using battens, which are temporary strips of flexible<br />

wood used to locate the belt. A ribband is also a<br />

batten, used on boats and ships to hold the frames in<br />

place while the planking is being added. Ribbands<br />

are removed as the planking is completed.<br />

6. Spiling is a term used to describe a process for<br />

marking and cutting a plank to a given shape.<br />

7. Edge-bending, also called springing, is when you<br />

bend a plank edgewise.<br />

8. When planking, the use of the word fair refers to<br />

smooth, gradual curves.<br />

9. Nib or nibbing is where one plank runs into another<br />

at a sharp angle. In order to eliminate the feathered<br />

edge, the plank is cut off on the end and it is fitted<br />

into a similar cut in the other plank. Nibbing is generally<br />

applied to decks, but hull planks are also<br />

nibbed.<br />

10. A stealer is a plank inserted into another plank, or<br />

notched in between two adjacent planks when the<br />

spacing between the planks gets too wide. Or, when<br />

two planks are tapering toward a narrow end, it may<br />

be necessary to cut off both planks, then substitute a<br />

wider plank to continue so there will be enough<br />

wood left for fastening the end of the plank. I’m at a<br />

loss for the proper term for this. One model publication<br />

calls it a joggle plank, but I’m not sure about that.<br />

Stealer is a common term , but joggle plank is not.<br />

11. The counter is the underside of the overhanging<br />

portion of a ship’s stern.<br />

1. Getting Started<br />

The planking process is tedious and you should plan<br />

on spending some time doing the job. Work on each<br />

plank as a project unto itself. Rushing will only result<br />

in frustration and a poor result.<br />

Since both sides of the hull will be identical, you can<br />

cut two planks the same shape at once. Fit the plank<br />

on one side, then the other. Before starting, place the<br />

hull upside down and secure it in a vise or cradle.<br />

Something portable would be ideal so you can rotate<br />

the hull easily.<br />

2. Planking Battens & Belts<br />

It is easier to plank a hull by first dividing the hull<br />

into a series of “belts”. The belts flow along the hull<br />

in smooth curves. Each belt is designed so the planks<br />

lay against the hull without having to excessively<br />

edge bend them. They sweep up at the ends like the<br />

deck sheer. Within each belt, the planks are usually<br />

spaced evenly, tapered, and fitted as required. The<br />

belts help accomplish the planking job without accumulating<br />

errors as you work.<br />

When selecting a belt width and the number of<br />

planks within each belt, you need to consider how<br />

the planks will lay against the frames and how they<br />

will taper. If the planks are too wide, they will not lay<br />

flat on the bulkheads. Also, you don’t want them to<br />

taper so much that there is no width left for fasteners.<br />

This would require substituting a larger plank for<br />

two to increase width. Also, in some areas, the planks<br />

may get wider rather than taper. If they get too wide,<br />

a stealer plank must be cut into the plank. While<br />

these alterations are acceptable and are used on<br />

many ships, it is best to design the run of planking to<br />

limit the number of such inserts (see figure 14 which<br />

illustrates some of these inserts).<br />

For the Pride of Baltimore II model, a planking layout<br />

has already been developed for you. The layout is<br />

taken from the actual ship and is shown on the P-O-B<br />

plans. The belts are not necessarily related to how the<br />

real ship was planked, but were selected for the convenience<br />

of the model maker. The real ship planking<br />

has been followed as closely as possible and was<br />

based on photographs and several key measurements<br />

of planking widths. Stealers have been placed<br />

where they were found on the real ship.<br />

3. Planking Butts<br />

Before you start, consider the planking butts. Since<br />

the lengths of wood cut from trees are generally<br />

shorter than the overall lengths of real ships, shipbuilders<br />

generally have to work with planks only 20<br />

or 30 feet long. Some modelers think it is easier to use<br />

a plank length the full length of the model. Fake butts<br />

can be scribed in later or omitted. Granted, this can<br />

be done. It’s really up to the modeler. By using shorter<br />

pieces, however, there are some advantages. Since<br />

all planks taper to some degree, using the shorter<br />

piece will let you mark the taper quick, and the plank<br />

will be easier to fasten in place. And with a short<br />

piece, only one hand is necessary to hold it down.<br />

Also, if you make a mistake, you only have a small<br />

piece to do over. So, the following is based on the use<br />

of the shorter lengths.<br />

Planking butts will not be exactly like the real ship.<br />

Because the model is designed to be built on the bulkhead<br />

system, no attempt was made to identify all the<br />

butts,so a deviation from the real ship planking butts<br />

was necessary.<br />

A plank length approximately 6 inches will cover<br />

four bulkhead spaces. This is a comfortable length to<br />

handle for this model. To scale, it is a plank 32 feet<br />

long. However, to avoid having very short pieces at<br />

the bow and stern, you may need to use a longer<br />

plank to complete the run.<br />

To follow real ship rules, you should stagger the butts<br />

on the model (see figure 15 for a sequence that is similar<br />

to that of a real ship). The stagger also applies to<br />

the deck planking. The 6-inch long plank works well<br />

with the rules. With this length you can meet the rule<br />

for three full plank-widths between butts on a single<br />

frame. If you use a plank length to cover only three<br />

bulkhead spacings, this would not be possible. Since<br />

the butts occur on bulkheads, you would wind up<br />

with only two full planks between the butts.

4. Spiling<br />

Edge-bending planks on a real ship is done, but it is<br />

limited. The wood is very stiff, so many planks must<br />

be cut to shape. Spiling is the term used for laying out<br />

the cuts (see figure 16). It’s simply a matter of transferring<br />

curves to a straight plank, then sawing the<br />

plank to shape. For the Pride of Baltimore II model, the<br />

wide planks landing at the sternpost should be the<br />

only strakes you need to spile. For narrow planks, the<br />

basswood strips are flexible enough so they can be<br />

edge-bent in place.<br />

5. Fastening the Planks<br />

There are some fancy plank clamps on the market,<br />

but they are more trouble than they are worth. They<br />

must be screwed into the edge of the bulkheads, leaving<br />

big holes to contend with when doing subsequent<br />

planks. With short pieces, you can hold or pin the<br />

planks in place. Be careful not to split the plank with<br />

the pins. If necessary, drill a small pilot hole first.<br />

Glue each plank to the bulkheads, and edge-glue<br />

them together. For the edges, use white or carpenter’s<br />

wood glue so that setting will not occur too fast. At<br />

the bulkheads, it is good to use thin super glue to<br />

quickly secure the plank in place. Be careful not to<br />

glue your fingers.<br />

While glue alone will hold the planks, you may wish<br />

to use small brass brads or wooden treenails for additional<br />

holding power, or just for looks. Using fine<br />

brass brads, cut off and discard the heads, then hammer<br />

them into place. If treenails are desired, you can<br />

buy them commercially. Better yet, get some long<br />

bamboo skewer sticks, strip off small pieces, then pull<br />

them through a draw plate until you have very small<br />

dowels. Drill holes for the treenails, add a touch of<br />

glue, and drive them into place. Treenails are good if<br />

you want to add them for each frame. While there are<br />

no frames, only bulkheads, use the bulwark stanchions<br />

for locating where a frame would be.<br />

6. Planking the Outer Hull<br />

Belt Layout: Now the fun begins! The hull is divided<br />

as follows: a single strake below the planksheer, a<br />

wale below that strake, then four belts A through D.<br />

The wale is a thick band of planking which cannot be<br />

varied from the real ship. The lower planking, on the<br />

other hand, could be slightly different and would not<br />

be noticed. The wale will be painted a light color.<br />

From the Hull Planking Layout drawing, use a tick<br />

strip along each bulkhead location and mark the wale<br />

location and the belt seams below. Using a tick strip,<br />

transfer the location of the seams on each bulkhead<br />

and mark them with a pencil. Now, using 1/16” x<br />

3/32” temporary basswood battens, lay the battens<br />

along the marks and temporarily tack them in place.<br />

The purpose of the battens is to assure an accurate<br />

flow of the planking belts. Although the Hull Planking<br />

Layout was developed to provide an accurate<br />

flow of belts, errors in drafting and tick strip marking<br />

and transferring may occur. With the battens actually<br />

in place, these errors can be corrected.<br />

With all the battens in place, visually check their<br />

flow. Look at the model from the side and from the<br />

bow and stern. Do the battens have nice smooth<br />

curves Adjust the battens if necessary (see figure<br />

17). The plans show what they should look like from<br />

the side and ends. When everything seems okay,<br />

remark the belt seam lines on the bulkheads, making<br />

sure they are clearly indicated. You do not want to<br />

15

FIG. 17 – Batten Layout<br />

Look for smooth flow<br />

of battens<br />

Planksheer<br />

Bottom wale<br />

Main rail<br />

“A”<br />

“B”<br />

“C”<br />

“D”<br />

Battens<br />

lose them. You could now remove the temporary battens<br />

or leave them in place until they need to be<br />

removed in order to add a plank.<br />

Sloping Plank Edges: As you proceed with the planking,<br />

you may need to slope the edges of a particular<br />

plank so it butts flush against the adjacent plank. This<br />

is especially true for a plank adjacent to another<br />

member intersecting at an angle. For example, the<br />

first plank below the planksheer at the bow butts<br />

against the planksheer at an angle. The edges of these<br />

planks must be trimmed so they fit against the<br />

planksheer (see figure 18).<br />

To begin with, all of the planks on the hull have<br />

square edges. When butted against each other on a<br />

round hull form, a small gap will appear between<br />

each plank. Most of the gaps eventually will be filled<br />

with glue, or you can fill them with wood filler. On a<br />

real ship, the gaps are caulked. In fact, the edges of<br />

the planks are often sloped to increase gapping. This<br />

measure assures that the inside of the planks butt<br />

against each other, while on the outside there are sufficient<br />

gaps for caulking. If you want a perfectly<br />

smooth hull without the gapping, you must trim the<br />

edge of each plank as you fit it. It’s a lot of work, but<br />

your decision.<br />

First strake below the planksheer: This is a single<br />

strake that is 1/16” thick by 3/32” wide from bow to<br />

stern. You will not taper it. Edge-cut the plank so it fits<br />

flush to the underside of the planksheer. Note that at<br />

the bow, the wale rides up to the planksheer. Run the<br />

plank forward, then when doing the wale, just add a<br />

doubler over the plank so that it will be the same thickness<br />

as the wale (see figure 19).<br />

Wale: The wale is made up of three planks that are<br />

3/32” thick. The planks will need to taper toward the<br />

stern since the overall wale should taper. Make each<br />

plank equal in width. On the real ship the wale is<br />

thicker than the hull planking, but not quite as much<br />

as you will get using a 1/16” hull plank and a 3/32”<br />

wale plank (a 2” difference on the real ship). If you<br />

desire, sand the wale down a little so it is not so thick.<br />

At this model scale, however, it is probably not necessary.<br />

The aft end of the wale and the counter planks intersect<br />

in a miter joint. See the expanded counter view<br />

on P-O-B plan sheet 2.<br />

FIG. 18 – Sloping the Plank Edges<br />

FIG. 19 – First Strake Below the Planksheer<br />

Wale planks<br />

FIG. 21 – Stealers in Belt D<br />

First plank strake<br />

(Bow area)<br />

Planksheer<br />

Edge must be<br />

sloped and fitted<br />

Doubler at bow to<br />

match wale thickness<br />

Sternpost<br />

Stealers<br />

16

Laying the Planks in Belt A: Each belt of planking<br />

should be done separately. Consequently, you can<br />

start with any belt. For discussion, let’s start at the<br />

top and work down. Belt A has six 1/16”–thick plank<br />

strakes below the wale. The maximum plank width is<br />

at Bulkhead G and is roughly a 9” real ship width (a<br />

little over 1/8” model scale). The planks should taper<br />

both forward and aft to about 3/32”. On the real ship,<br />

the planks taper to no less than 5-1/2”. Use the 1/16”<br />

x 3/16” strips for the planking in this belt.<br />

Use a tick strip and lift the plank widths from the<br />

Hull Planking Layout on Sheet 2. If you have<br />

changed the locations of the battens, simply divide<br />

the space into six equal plank widths at each bulkhead.<br />

A set of proportional dividers would help.<br />

Mark these lines on the bulkheads with a pencil. You<br />

will then have a completely marked area for Belt A.<br />

The next step is to cut planks to fit between the<br />

marks. Belt A will not require spiling, so a straight<br />

tapered plank can be made. Start at Bulkhead G. Use<br />

four planks, one from Bulkhead G to Bulkhead K,<br />

another from K to the transom, Bulkhead G to Bulkhead<br />

C, and Bulkhead C to the stem. First, lay a piece<br />

of planking material over the bulkheads and mark<br />

the length. Mark the plank in pencil at each of the<br />

bulkheads. Next, use a set of dividers or a tick strip<br />

and lift the plank widths from the marks on the bulkheads<br />

and transfer to the plank. Draw a line through<br />

the points and cut the plank. You now have a tapered<br />

plank. Trace this plank to obtain another one for the<br />

other side of the hull.<br />

Install the planks on the hull, butting them up against<br />

the wale. Then, do the same process for the next<br />

strake below. Stagger the butts for this strake. Install a<br />

plank from Bulkhead F to B, B to the stem, F to J, and<br />

J to the transom. You should have four planks making<br />

up each strake from bow to stern (see figure 20).<br />

At the stern, some planks will need to be twisted into<br />

place. You may need to steam bend the twist if it is<br />

severe.<br />

Now move down to the next planking strake and<br />

work it the same way as you did the previous one.<br />

Stagger the plank butts, starting at Bulkhead E. Continue<br />

until this strake is finished, then complete the<br />

strakes in Belt A.<br />

For now, let the aft ends of the planks that rest on the<br />

counter extend just beyond the counter. When you<br />

plank the counter, the counter and hull planks should<br />

meet in a miter like the wale noted previously.<br />

Laying the Planks in Belt B: This belt is very similar to<br />

Belt A. It has six plank strakes about the same width<br />

as those in Belt A. If you have not removed the temporary<br />

batten, do it now. Then you may start the<br />

process for Belt B. Remember to stagger the butts.<br />

Laying the Planks in Belt C: This belt is also similar to<br />

Belt A except that the planks do not get tapered as<br />

abruptly at the stern. Also, there are seven, rather<br />

than six, strakes. As mentioned when you were checking<br />

the fairness of the bulkheads, the area near the<br />

sternpost takes a severe bend. Steam-bending this<br />

area is essential, otherwise the planks may break or<br />

knuckle as you lay them over Bulkhead L. You can<br />

also use the filler block as an option.<br />

Laying the Planks in Belt D: This belt will contain the<br />

garboard strake (next to the keel) and two other<br />

strakes. It will also contain three stealers in order to<br />

reduce the width aft as shown (see figure 21). All the<br />

planks in this belt will be very wide (about 13” fullship<br />

size) and must be spiled. You will need to use the<br />

wide planking strips provided in the kit. There will<br />

also be some severe twist to the forward part of the<br />

planks. The twist should be steam-bent.<br />

Toward the bow, the planks will feather out at the<br />

rabbet rather sharply. This is fine for the model, but<br />

on the real Pride of Baltimore II, four of the lower<br />

planks have nibs in them as shown (see figure 22).<br />

You may do this if you desire.<br />

P-O-B plan sheet 2 has a complete planking profile as<br />

shown. Use this drawing to determine the plank<br />

widths in Belt D. The sections, Hull Planking Layout<br />

drawing , cannot show all the planks aft so the profile<br />

view is necessary.<br />

Plank Variations within a Belt: Suppose you are working<br />

within a belt, and have five planks the same<br />

width, and then find that the last plank in the belt<br />

needs to be made slightly wider to complete the<br />

belt...should you worry Certainly not. No planking<br />

job, even on real ships, is that precise. You are dealing<br />

with hand-cut planks. The important thing is to keep<br />

the flow of planks smooth. A variation in widths is of<br />

no great concern. Even though this kit tries to duplicate<br />

the planking on the real Pride of Baltimore II, you<br />

must be realistic. There are going to be some slight<br />

variances as you proceed.<br />

17

7. Planking the Transom & Counter<br />

For the model, the side hull planks can be extended<br />

past the counter (bottom curved portion of the stern<br />

overhang), and the 1/16”-thick counter planks<br />

butted into the hull planks or vice versa. On the real<br />

ship, however, the counter plank meets the hull<br />

plank in a miter joint. If you elect to do this, first cut<br />

the ends of the hull plank that you left hanging over,<br />

then add the counter planks. Cut the miter on each<br />

plank, then glue them in place (see figure 23). You<br />

could also cut the miter as you add each side plank.<br />

Add a strip to the upper edge of the counter planking<br />

so it covers the end grain. Round this edge like the<br />

molding above it.<br />

Plank the outside of the transom with 1/32”-thick<br />

planks (see figure 24). The section below the molding<br />

strip can be made from 1/32”-wide material. On the<br />

real ship, the upper part is mahogany and the planks<br />

can be seen. The lower section should either be<br />

planked or you may use a wide sheet (It was not possible<br />

to decipher this detail from photographs taken<br />

of the transom). Over top of the 1/32” planks, add<br />

the 1/32”-thick fancy piece and the molding strip.<br />

Leave a little gap in the upper horizontal molding for<br />

inserting the Maryland flag emblem.<br />

The inside of the transom will not be planked, so<br />

make sure you remove any glue squeeze-out<br />

between the outer plank seams and along the stern<br />

knees.<br />

8. Planking the Bulwarks<br />

The planks between the planksheer and main rail<br />

will be in two thicknesses. There are five planks that<br />

are 1/32”-thick, and a 3/64”-thick plank at the top.<br />

Check the width of the inboard stringer, the head of<br />

the bulwark stanchions, and the outboard thick<br />

strake. The total width must be correct since these<br />

pieces must fit under the main rail. If any one part is<br />

oversize it won’t fit. You should not have to make the<br />

rail wider to cover a mistake. The rail would look<br />

bulky and be out of scale.<br />

The bulwark planks are fairly uniform and will not<br />

require any severe tapering forward or aft. If you do<br />

not want to use the five planks, you may use only<br />

two, or even a solid piece. The real ship, however,<br />

was planked as described. Simplification is up to you<br />

and it is certainly justified if you intend to paint the<br />

model.<br />

As you plank the bulwarks, remember that there will<br />

be no planking inboard so you should clean up any<br />

glue squeeze-out on the inside as you plank. If left to<br />

harden, it would be difficult to remove.<br />

Note that there will be a continuous scupper along<br />

the side, so the lowest bulwark plank should not<br />

touch the planksheer from gunport 2 to 5 (see figure<br />

25). There is a real ship gap of 1” at the deck. For the<br />

model, you could cheat a little and use about a 1/32”<br />

gap rather than 1/64” so it shows up better. Forward<br />

and aft of the two gunports, small drilled scuppers<br />

are used.<br />

18

The top 3/64” plank should continue across the gunports.<br />

Apply a 1/32”-square vertical strip of wood on<br />

each side of the gunport, simply to cover the end<br />

grain of the bulwark plank (you could omit this on<br />

the model).<br />

Next, fit a fashion piece on each side of the transom<br />

as shown (see figure 26).<br />

9. Planking the Deck<br />

Hatch & Trunk Coamings: Before planking the deck,<br />

you must decide how you want to treat the hatch and<br />

trunk coamings. A recommended approach for doing<br />

it the way it was done on the real ship, is to install all<br />

coamings first. You can then plank around the coamings.<br />

This saves some planking work and material.<br />

On the underside of the coamings, insert some scrap<br />

wood so the deck planks have support for gluing (see<br />

figure 27).<br />

If you elect not to install the coamings now, they<br />

must be included in the construction of the hatches<br />

and trunks and glued down on top of the deck.<br />

Deck Planks: The deck planks should be 1/16” thick<br />

x 3/32” wide except for a 1/16” x 3/16” plank port<br />

and starboard at the centerline. On the real ship, the<br />

two center wide planks are just slightly thicker than<br />

the other planks. It is not necessary to indicate this<br />

variation in size at this 3/16” model scale.<br />

Prepare the strips by painting one edge black or dark<br />

brown. When the planks are glued together, this will<br />

simulate caulking in the seams. You can also use a<br />

brown colored carpenter’s wood glue on the edges of<br />

the planks. When dry, this glue is dark enough to<br />

simulate the caulking.<br />

Thick Pads: There are some thick pads that must be<br />

put on the deck around the windlass (used on the<br />