Montgomery Canal Conservation Management Strategy (1.2MB PDF)

Montgomery Canal Conservation Management Strategy (1.2MB PDF)

Montgomery Canal Conservation Management Strategy (1.2MB PDF)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

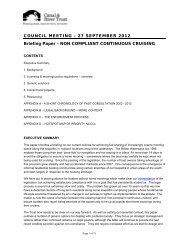

viii. The Shropshire Union Railways and <strong>Canal</strong> Company<br />

In 1847 and 1850, the Eastern and Western Branches amalgamated with the Shropshire Union Railways and <strong>Canal</strong><br />

Company (SURCC), which thereafter controlled them until 1922. The SURCC balanced its canal and railway interests in<br />

such a way that the <strong>Montgomery</strong> <strong>Canal</strong> survived as a working waterway into the second quarter of the 20th century,<br />

receiving the final additions to its buildings and character. A colourful commercial enterprise of this period was the shortlived<br />

flyboat passenger service from Newtown to Rednal. It is claimed that the unique brick and timber warehouse at<br />

Rednal was made use of for this service, but there is no proof of this. It is an example of a vernacular type of<br />

construction found usually in the late 18th century, and it is possible that the warehouse predates the canal, like Heath<br />

House on the opposite bank. Associated with the canal’s only turnover bridge, and the nearby 19th century railway<br />

bridge, this building forms the centre of a particularly noteworthy waterside settlement, showing continuity with an earlier<br />

period.<br />

During the last quarter of the century, there seems to have been a swing to animal husbandry and dairying. The canal’s<br />

management responded to this by providing new warehouses suitable for what were usually powders and grains in<br />

sacks. Queen’s Head was the largest of these, with facilities for storing a variety of goods, and a basement tunnel linking<br />

it with a nearby sandpit. This warehouse, along with that at Brynderwen and a smaller example at Tyddyn, have<br />

corrugated roofs and cladding above a blue-brick basement. Other warehouses, like the recently restored example at<br />

Brithdir, were simply sheds. They were built of wood and corrugated iron, in a typically railway style. Even the grandest<br />

industrial buildings are normally built of expedient materials; in the late 19th century, they included corrugated iron.<br />

Carreghofa aqueduct, built in 1866-1870, to accommodate the railway, has a slope-sided trough in wrought iron<br />

supported on cast iron columns and bracing struts, and is one of the most advanced engineering structures on the canal.<br />

Blue engineering brick was used extensively in the late 19th century, with little regard to local style. This is at its extreme<br />

in Brithdir lock house that was rebuilt in the 1890s, entirely in blue brick.<br />

ix. Welshpool Wharf<br />

As the only town on the canal between Frankton and Newtown, Welshpool became the canal’s principal trading centre.<br />

During the early 19th century Aqueduct warehouse was the principal building. By 1884 the building that now dominates<br />

Town Wharf was fully developed. The new and substantial canal maintenance yard, now Travis Perkins, was also<br />

established.<br />

It is a particularly noteworthy survival, in view of its date and its completeness, and further study would be justifiable. The<br />

lock mill wheelpit and buildings on Hollybush Wharf survived as late as 1981, but have now been lost, although some of<br />

the small buildings, including the canal office and warehouses at the rear of the wharf, still survive. The remains of<br />

another of the town’s wharves, associated with a bank of limekilns and including a dry dock, was recently uncovered<br />

during excavations further north, although no visible structures now survive.<br />

x. Limestone Economy<br />

Carrying limestone, and the coal to burn it, was the canal’s main purpose for most of its history, with 98 limekilns along<br />

its length in its heyday. The industrial heritage area complex at Llanymynech was the first destination of the canal, and<br />

boasts numerous important archaeological and building remains, including incline tramways to the wharves and the<br />

exceptional Hoffman limekiln, whose chimney dominates the area. The complex is arguably the most significant historic<br />

site along the canal and is of national importance and a rare industrial survival, illustrating not only developments in the<br />

lime industry, but also its impact on the wider landscape. Although many of the other canalside limekilns have now been<br />

lost, the remains of around 35 kilns can still be readily identified, with particularly good examples at Llanymynech, Belan<br />

and Pant. The limekilns are some of the most impressive features of the canal’s built heritage and they are of particular<br />

importance where they are associated with other notable features, as at Belan, Garthmyl, and Brithdir, as well as<br />

Llanymynech. One of the greatest concentrations of canalside limekilns in the United Kingdom was built on the very<br />

extensive Newtown Wharves where some of the kilns survive.<br />

32