BANGLADESH: Criminal justice through the prism of capital ... - FIDH

BANGLADESH: Criminal justice through the prism of capital ... - FIDH

BANGLADESH: Criminal justice through the prism of capital ... - FIDH

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

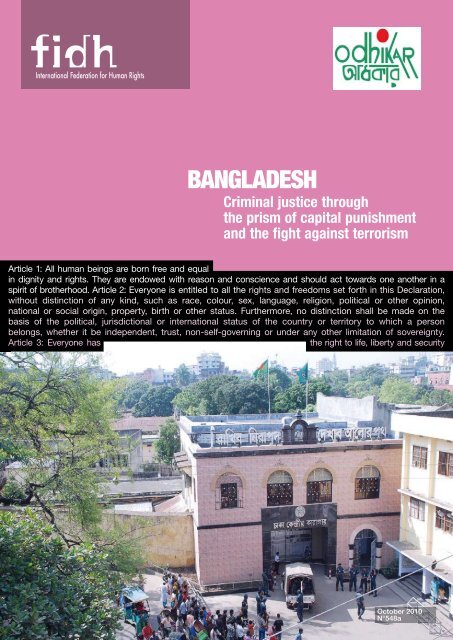

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong><br />

<strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment<br />

and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism<br />

Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal<br />

in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one ano<strong>the</strong>r in a<br />

spirit <strong>of</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>rhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all <strong>the</strong> rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration,<br />

without distinction <strong>of</strong> any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or o<strong>the</strong>r opinion,<br />

national or social origin, property, birth or o<strong>the</strong>r status. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, no distinction shall be made on <strong>the</strong><br />

basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> political, jurisdictional or international status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country or territory to which a person<br />

belongs, whe<strong>the</strong>r it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any o<strong>the</strong>r limitation <strong>of</strong> sovereignty.<br />

Article 3: Everyone has<br />

<strong>the</strong> right to life, liberty and security<br />

October 2010<br />

N°548a

This document has been produced with <strong>the</strong> financial assistance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> European Union.<br />

The contents <strong>of</strong> this documents are <strong>the</strong> sole responsability <strong>of</strong> <strong>FIDH</strong> and Odhikar and can<br />

under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> European Union.<br />

Cover: Dhaka Central Jail 2 / Titre du rapport – <strong>FIDH</strong>

I. Introduction............................................................... 4<br />

Context <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mission ......................................................... 4<br />

Legal History <strong>of</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Law in Bangladesh ....................................... 4<br />

II. Bangladesh and international human rights law................................. 7<br />

Ratification <strong>of</strong> International Human Rights Instruments................................ 7<br />

Cooperation with UN Human Rights Mechanisms.................................... 7<br />

The National Human Rights Commission........................................... 8<br />

III. The death penalty in Bangladesh............................................ 11<br />

Crimes Punishable by Death.................................................... 11<br />

Mandatory Death Sentences .................................................... 12<br />

Available Statistics on <strong>the</strong> Death Penalty - Transparency.............................. 13<br />

IV. The administration <strong>of</strong> criminal <strong>justice</strong>. ...................................... 15<br />

Police Custody and Arrest...................................................... 15<br />

The Trial Phase.............................................................. 18<br />

Bail. .................................................................... 18<br />

Filing <strong>of</strong> false cases......................................................... 18<br />

Courts and <strong>the</strong> judiciary...................................................... 19<br />

Integrity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> judiciary................................................... 20<br />

International crimes Tribunal............................................... 22<br />

Appeals and clemency....................................................... 22<br />

The BDR Case............................................................. 24<br />

Prison Conditions ............................................................ 24<br />

Executions.................................................................. 26<br />

Methods <strong>of</strong> Executions. ..................................................... 26<br />

V. Terrorism................................................................ 27<br />

The questionable compliance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new anti-terrorism legislation<br />

with Bangladesh human rights commitment........................................ 28<br />

Vague terminology in <strong>the</strong> ATA................................................. 28<br />

Length <strong>of</strong> police custody facilitates abuse <strong>of</strong> power. ............................... 29<br />

ATA crimes non-bailable ..................................................... 30<br />

Specially-constituted tribunals invite abuse....................................... 30<br />

Anti-terrorist surveillance legislation violates rights to privacy and fair trial ............. 31<br />

Restriction <strong>of</strong> freedom <strong>of</strong> speech............................................... 32<br />

Mobilisation against <strong>the</strong> Anti-Terrorism Ordinance. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32<br />

VI. Torture................................................................. 34<br />

An Inappropriate Legislation ................................................... 34<br />

A culture <strong>of</strong> Impunity Consecrated by Bangladeshi Law .............................. 35<br />

Impunity for Enforced Disappearances............................................ 36<br />

VII. Conclusion and Recommendations. ........................................ 37<br />

VIII. Appendices<br />

Status <strong>of</strong> Commitment to International Human Rights Treaties <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh. ............ 41<br />

Declarations and/or Reservations <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh on Human Rights Treaties ............... 42<br />

Leading Cases on Death Penalty from 1987 to 2009.................................. 44<br />

Persons met by <strong>the</strong> <strong>FIDH</strong>/Odhikar mission......................................... 50<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 3

Introduction<br />

Context <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mission<br />

The International Federation for Human Rights (<strong>FIDH</strong>) fact-finding mission’s mandate was<br />

to enquire on <strong>the</strong> death penalty and <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> criminal <strong>justice</strong> in Bangladesh, with<br />

a focus on people convicted for so-called terrorist <strong>of</strong>fences. The principal objective was to<br />

assess <strong>the</strong> respect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fair trial guarantees, in particular <strong>the</strong> prohibition <strong>of</strong> torture, in <strong>capital</strong><br />

cases. The mission also attempted to look at <strong>the</strong> specific situation <strong>of</strong> persons suspected <strong>of</strong><br />

having committed so-called terrorist <strong>of</strong>fences, and determine whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re are specificities in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> criminal procedure or practices in <strong>the</strong>ir regard, that contravene international human<br />

rights law.<br />

The mission was composed <strong>of</strong> three representatives: Mr. Mouloud Boumghar (Algeria/France);<br />

Ms. Laurie Berg (Australia) and Ms. Nymia Pimentel Simbulan (Philippines), and was supposed<br />

to take place from 23rd to 31st January 2010. However, <strong>FIDH</strong> and Odhikar decided to delay<br />

it because <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court was expected to deliver a final judgment in a highly sensitive<br />

case involving <strong>the</strong> death penalty. Indeed, on 27 January 2010, <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court upheld <strong>the</strong><br />

death sentences against 15 persons convicted for <strong>the</strong> killing in 1975 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first President <strong>of</strong><br />

Bangladesh. Five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m were executed <strong>the</strong> next day.<br />

The mission eventually took place from 1st to 9 April 2010. In Jessore, Narail and Jhenaidah,<br />

<strong>the</strong> mission met with families <strong>of</strong> death row prisoners. Most meetings took place in Dhaka, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>capital</strong> <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh.The mission met with a range <strong>of</strong> human rights NGOs, academics, judges,<br />

journalists, lawyers, <strong>the</strong> National Human Rights Commission, people prosecuted under <strong>the</strong><br />

Anti-Terrorism Act and families <strong>of</strong> death row inmates. The mission also had <strong>the</strong> opportunity to<br />

meet with several representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authorities, including Mr. Justice Md. Fazlul Karim,<br />

Chief Justice <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh ; Mr. Mahbubey Alam Attorney General for Bangladesh ; Barrister<br />

Shafiq Ahmed Minister <strong>of</strong> Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs; Mr. Ashraful Islam Khan,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Inspector General <strong>of</strong> Prisons, and several Members <strong>of</strong> Parliament.<br />

<strong>FIDH</strong> wishes to thank <strong>the</strong> authorities for <strong>the</strong>ir cooperation during <strong>the</strong> mission and <strong>the</strong>ir acceptance<br />

to meet with its members. It regrets that access to prisons was refused though no reason<br />

has been given and hope that this trend could be reversed in <strong>the</strong> future, since it would allow<br />

to have first-hand information on prison conditions, ra<strong>the</strong>r than relying on indirect sources.<br />

<strong>FIDH</strong> also wishes to thank Odhikar, its member organization in Bangladesh, without which<br />

<strong>the</strong> mission and this report would not have been possible.<br />

Legal History <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh: <strong>Criminal</strong> Law<br />

The Indian Subcontinent, comprising <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, has a long history <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment. A stay in this form <strong>of</strong> punishment came at <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> Emperor<br />

Ashoka, who preached peace, Buddhism and non-violence during <strong>the</strong> 2 nd century BC. During<br />

his reign, <strong>capital</strong> punishment was banned. However, this all changed after his reign ended and<br />

by <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 15 th century BC <strong>the</strong> states that made up India were wrought with warfare and<br />

4 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

intrigue and <strong>capital</strong> punishment was extremely common 1 . During <strong>the</strong> Moghul era in <strong>the</strong> early<br />

16 th century, <strong>capital</strong> punishment was retained as <strong>the</strong> highest form <strong>of</strong> punishment and connected<br />

with class and caste. A Chinese visitor to India in <strong>the</strong> 5 th century BC observed that a Sudra 2<br />

who insulted a Bhramin faced death whereas a Bhramin who killed a Sudra was given a light<br />

penalty, such as a fine – <strong>the</strong> same penalty he might have incurred if he had killed a dog. 3<br />

The present legal and judicial system <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh owes its origin mainly to two hundred<br />

years British rule in <strong>the</strong> Indian Sub-Continent although some elements <strong>of</strong> it are remnants <strong>of</strong><br />

Pre-British period tracing back to Hindu and Muslim administration. The legal system <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

present day emanates from a mixed system which has structure, legal principles and concepts<br />

modeled on both Indo-Mughal and English law. The Indian sub-continent has a history <strong>of</strong><br />

over five hundred years with Hindu and Muslim periods which preceded <strong>the</strong> British period,<br />

and each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se early periods had a distinctive legal system <strong>of</strong> its own. The ancient India<br />

was divided into several independent states and <strong>the</strong> king was <strong>the</strong> Supreme authority <strong>of</strong> each<br />

state. So far as <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> <strong>justice</strong> was concerned, <strong>the</strong> king was considered to be <strong>the</strong><br />

fountain <strong>of</strong> <strong>justice</strong> and was entrusted with <strong>the</strong> Supreme authority <strong>of</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> <strong>justice</strong><br />

in his kingdom. The Muslim period starts with <strong>the</strong> invasion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Muslim rulers in <strong>the</strong> Indian<br />

sub-continent in 1100 A.D. The Hindu Kingdoms began to disintegrate gradually with <strong>the</strong><br />

invasion <strong>of</strong> Muslim rulers at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> eleventh and at <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> twelfth century. When<br />

<strong>the</strong> Muslims conquered all <strong>the</strong> states, <strong>the</strong>y brought with <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory based on <strong>the</strong> Holy<br />

Quran. According to <strong>the</strong> Holy Quran, sovereignty lies in <strong>the</strong> hand <strong>of</strong> Almighty Allah. 4<br />

The so-called ‘modernisation’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> legal system began with <strong>the</strong> British and <strong>the</strong>ir Royal<br />

Charters. The East India Company gained control and was ultimately powerful enough to<br />

take part in <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> <strong>justice</strong> with <strong>the</strong> local authorities. The Charter <strong>of</strong> 1726,<br />

issued by King George I, gave Letters Patent to <strong>the</strong> East India Company and was <strong>the</strong> gateway<br />

<strong>through</strong> which o<strong>the</strong>r legal and judicial systems entered India from England. In 1753, ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Charter was issued by King George II to remove <strong>the</strong> defects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> previous Charter. In 1773,<br />

<strong>the</strong> House <strong>of</strong> Commons passed <strong>the</strong> Regulation Act to improve <strong>the</strong> judicial system and under<br />

it, <strong>the</strong> King issued ano<strong>the</strong>r Charter in 1774 establishing <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Judicature at<br />

Calcutta (now Kolkata). On 15 August 1772, Lord Hastings drew up a collection <strong>of</strong> laws that<br />

became <strong>the</strong> first British Indian law code in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The code contained<br />

37 sections addressing both civil and criminal law and a new system <strong>of</strong> courts took over from<br />

<strong>the</strong> slowly defunct Moghul ones. The new court system provided for separate civil (dewani)<br />

and criminal (fowjdari) courts. In 1801, ano<strong>the</strong>r Supreme Court was established in Madras<br />

and one in Bombay in 1824.<br />

Between <strong>the</strong> 1790’s and <strong>the</strong> 1820’s, <strong>the</strong> East India Company promulgated <strong>the</strong> largest number<br />

<strong>of</strong> Regulations that brought about changes in <strong>the</strong> criminal <strong>justice</strong> system in <strong>the</strong> sub continent.<br />

In 1853, <strong>the</strong> Law Commission was established in India and <strong>the</strong> British Crown replaced <strong>the</strong><br />

East India Company in 1859. The Penal Code was enacted in 1860, followed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong><br />

Procedure Code 1898, following <strong>the</strong> efforts <strong>of</strong> Lord Macaulay, an English lawyer, in bringing<br />

1. For more information see Johnson, David T. and Zimrig, Franklin. The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change and <strong>the</strong><br />

Death Penalty in Asia. Oxford University Press 2009.<br />

2. A lower Hindu caste. Bhramins are <strong>the</strong> highest caste.<br />

3. For more information see Johnson, David T. and Zimrig, Franklin. The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change and <strong>the</strong><br />

Death Penalty in Asia. Oxford University Press 2009.<br />

4. www.bangladesh.gov.bd/index.phpoption=com_content&task=view&id=58&Itemid=137.<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 5

toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> ‘native’ and British systems into a single criminal law. With <strong>the</strong>m, laws such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Code <strong>of</strong> Civil Procedure 1908 and <strong>the</strong> Evidence Act 1872 were also enacted.<br />

It took nearly three decades to give final shape to <strong>the</strong> codification <strong>of</strong> criminal law in British<br />

India. This codification is <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> strenuous effort <strong>of</strong> two law commissions. The first<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se commissions was established in 1837 in India and was led by Thomas Babington<br />

Macaulay. The second Commission was established in England in 1853. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> controversial<br />

issues during <strong>the</strong> period was <strong>the</strong> separate dispensation provided to European subjects<br />

in India and <strong>the</strong> Indians. They came under <strong>the</strong> jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> separate sets <strong>of</strong> courts and laws.<br />

Equality <strong>of</strong> protection under <strong>the</strong> same law and a common judicature based on <strong>the</strong> principle <strong>of</strong><br />

rule <strong>of</strong> law became issues <strong>of</strong> paramount importance. This is where Macaulay intervened. He<br />

defined <strong>the</strong> principle on which <strong>the</strong> codification <strong>of</strong> law must be based. He defined <strong>the</strong> principle<br />

as uniformity where it was possible to achieve and diversity where necessary. This was <strong>the</strong><br />

guiding principle which initiated <strong>the</strong> process leading to <strong>the</strong> abolition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dual system <strong>of</strong><br />

judicial administration and <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> a secular legal system.<br />

The process culminated, after much debate, changes and discussion, in <strong>the</strong> enactment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Indian Penal Code (Act XLV <strong>of</strong> 1860) and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Procedure Code (Act XXV <strong>of</strong> 1898).<br />

These two Codes laid <strong>the</strong> foundation <strong>of</strong> criminal law in British India. After 1947(<strong>the</strong> partition<br />

<strong>of</strong> India and Pakistan), <strong>the</strong> title <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Indian Penal Code was changed to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pakistan<br />

Penal Code. Similarly, after 1971 (<strong>the</strong> independence <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh from Pakistan), <strong>the</strong> Pakistan<br />

Penal Code came to be known simply as <strong>the</strong> ‘Penal Code’ in independent Bangladesh. Except<br />

for <strong>the</strong> changes in title <strong>the</strong> Penal Code more or less remained an immutable document with<br />

only minor modifications. The same can be said <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Code <strong>of</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Procedure1898.<br />

6 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

II. Bangladesh and<br />

International Human<br />

Rights Law<br />

Ratification <strong>of</strong> international human rights instruments<br />

The People’s Republic <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh (Bangladesh) has bound itself to upholding human rights<br />

law by committing to a number <strong>of</strong> international human rights treaties 5 . Bangladesh <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

has <strong>the</strong> obligation to take legislative measures in accordance with <strong>the</strong> treaties that it has ratified,<br />

as well as upholding <strong>the</strong>ir implementation on every level.<br />

In a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> international human rights treaties ratified or acceded to by <strong>the</strong> People’s<br />

Republic <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh, however, <strong>the</strong> government had registered some declarations and<br />

reservations to particular articles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> treaties (see table in annex 2). Paramount among <strong>the</strong>se<br />

is <strong>the</strong> reservation to Article 14 paragraph 1 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention Against Torture (CAT), on <strong>the</strong><br />

ground that Bangladesh will apply it “in consonance with <strong>the</strong> existing laws and legislation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> country”. 6 It is to be noted that <strong>the</strong>re is no definition <strong>of</strong> ‘torture’ in <strong>the</strong> domestic legislation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bangladesh.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, Bangladesh has not yet ratified nor has it acceded to a number <strong>of</strong> international<br />

human rights treaties, particularly <strong>the</strong> Optional Protocols to <strong>the</strong> two International Covenants,<br />

i.e. <strong>the</strong> ICESCR and <strong>the</strong> ICCPR. The Second Optional Protocol <strong>of</strong> 15 December 1989 to <strong>the</strong><br />

ICCPR aims at abolishing <strong>the</strong> death penalty. Likewise, it has not yet ratified or acceded to <strong>the</strong><br />

Optional Protocol to <strong>the</strong> Convention against Torture (CAT). This important instrument mandates<br />

State Parties to allow members or experts <strong>of</strong> independent international and national bodies to<br />

conduct regular visits to places like jails, detention centres, state penitentiaries and military<br />

camps, where individuals deprived <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir liberty are kept, to investigate cases <strong>of</strong> torture,<br />

cruel and ill treatment or punishment. 7 Nei<strong>the</strong>r is Bangladesh a State Party to <strong>the</strong> International<br />

Convention for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Moreover, As a<br />

major sending country <strong>of</strong> migrant workers 8 , many <strong>of</strong> whom find <strong>the</strong>mselves exposed to grave<br />

abuse and exploitation, ratification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> International Convention on <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Rights <strong>of</strong> All Migrant Workers and Members <strong>of</strong> Their Families, signed in 1998, would send a<br />

strong signal <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh’s commitment to ensuring <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> its citizens abroad.<br />

Cooperation with UN human rights mechanisms<br />

As a State Party to international human rights instruments, <strong>the</strong> government <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh has<br />

<strong>the</strong> obligation to submit periodic reports to <strong>the</strong> treaty-monitoring bodies established by <strong>the</strong><br />

international human rights instruments. Those reports detail <strong>the</strong> efforts carried out at national<br />

5. See table in annex on ratified human rights instruments.<br />

6. visit www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cat-reserve.htm<br />

7. Optional Protocol to <strong>the</strong> Convention Against Torture and O<strong>the</strong>r Forms <strong>of</strong> Cruel, Degrading or Ill Treatment or Punishment<br />

8. International Migration Guide. http://uk.oneworld.net/guides/migrationgclid=CJSj2Pvsl6MCFcdS6wodc3vKtg (Accessed: 1 August 2010).<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 7

level by <strong>the</strong> authorities in order to implement <strong>the</strong> relevant international conventions. Although<br />

<strong>the</strong> government <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh submitted periodic reports to various treaty bodies over <strong>the</strong><br />

past years, such reports are overdue to <strong>the</strong> Human Rights Committee 9 , <strong>the</strong> Committee on<br />

Economic, Social and Cultural rights 10 and <strong>the</strong> Committee Against Torture 11 . All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m are<br />

initial reports, which means that <strong>the</strong> authorities have not yet submitted a single report under<br />

those conventions. 12<br />

Several requests by Special Rapporteurs have likewise been made to <strong>the</strong> Bangladesh government<br />

to be invited to conduct field visits and ga<strong>the</strong>r data on alleged violations <strong>of</strong> human rights.<br />

Among <strong>the</strong>se were <strong>the</strong> request for an invitation from <strong>the</strong> Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial,<br />

Summary or Arbitrary Executions, made in 2006 and reiterated in 2008 and 2009. 13 In 2007,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Special Rapporteur on Independence <strong>of</strong> Judges and Lawyers requested to visit <strong>the</strong> country<br />

to look into <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s judicial system and <strong>the</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> <strong>justice</strong>. 14<br />

These requests have not been granted by <strong>the</strong> government to this date, in spite <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

accepting those invitations is included in <strong>the</strong> Universal Periodic Review’s recommendations. 15<br />

The government <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh replied to that recommendation as follows: “Bangladesh has<br />

been fully cooperating with <strong>the</strong> special procedure mechanisms. Some special rapporteurs have<br />

visited in recent years. A few requests are pending. We are in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> finalizing <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

requests and we expect <strong>the</strong> visits to begin very soon.” 16<br />

The National Human Rights Commission <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh (NHRC)<br />

In application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Human Rights Commission Ordinance 2007 (Ordinance 40 <strong>of</strong><br />

2007), <strong>the</strong> National Human Rights Commission <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh was established and came into<br />

existence in September 2008. It was created by <strong>the</strong> President on 1 December 2008 and initially<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> a Chairman and two Commissioners, with Justice Amirul Kabir Chowdhury, a<br />

retired judge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Appellate Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh, as Chairman. 17<br />

However, with <strong>the</strong> passage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Human Rights Commission Act 2009 (Act 53 <strong>of</strong><br />

2009) on 14 July 2009, <strong>the</strong> composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Commission was expanded to a maximum <strong>of</strong><br />

7 members, i.e. <strong>the</strong> Chairperson and up to six Members. The Act also stipulates that one member<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Commission must be a woman and ano<strong>the</strong>r from an ethnic group. A full-fledged NHRC<br />

under <strong>the</strong> present Act has been reconstituted appointing a new full time chairman and one full<br />

time member and five part time members on 22 July 2010 as per provision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law. The<br />

Selection Committee has <strong>the</strong> authority to recommend <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> NHRC<br />

to <strong>the</strong> President for appointment, who <strong>the</strong>n appoints <strong>the</strong> members. 18<br />

9. HRC, <strong>the</strong> body established under <strong>the</strong> ICCPR to monitor its implementation.<br />

10. Established under <strong>the</strong> ICESCR.<br />

11. Under <strong>the</strong> Convention Against Torture, or CAT.<br />

12. www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/NewhvVAllSPRByCountryOpenView&Start=1&Count=250&Expand=14.2#14.2 (Accessed: 7 August 2010).<br />

13. www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/chr/special/countryvisitsa-e.htm#bangladesh (Accessed: 8 August 2010).<br />

14. Ibid.<br />

15. A/HRC/11/18, 5 October 2009, Recommendation n° 12.<br />

16. A/HRC/11/18/Add.1, 9 June 2009.<br />

17. National Human Rights Commission. National Human Rights Commission Marches Ahead. (Brochure).<br />

18. The Act provides for a selection procedure <strong>of</strong> members to <strong>the</strong> National Human Rights Commission by a seven- member Selection<br />

Committee. The Selection Committee will be headed by an Appellate Division Judge nominated by <strong>the</strong> Chief Justice and will also include<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cabinet Secretary; Attorney General; Comptroller and Auditor General; Chairman, Public Service Commission; and <strong>the</strong> Law Secretary<br />

as members. In particular, <strong>the</strong> Act provides that <strong>the</strong> selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Commission is made by a committee predominantly<br />

made up <strong>of</strong> Government <strong>of</strong>ficials.<br />

8 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

Consistent with <strong>the</strong> Paris Principles on national human rights institutions, <strong>the</strong> NHRC is<br />

mandated to: 19<br />

– investigate complaints on human rights violations filed by any individual or any person on<br />

behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> victim/s;<br />

– visit places where persons deprived <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir liberty are detained and make recommendations<br />

for <strong>the</strong> improvement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se places;<br />

– review laws and legislations if consistent with human rights treaties and standards, conduct<br />

studies on laws and international human rights instruments and provide advise to <strong>the</strong><br />

Government;<br />

– coordinate with human rights NGOs and institutions; and<br />

– take concrete actions like mediation and arbitration to address human rights violations.<br />

Former Chairman Justice Amirul Kabir Chowdhury told <strong>the</strong> <strong>FIDH</strong>/Odhikar delegation in an<br />

interview that as <strong>of</strong> March 2010, <strong>the</strong> NHRC had received 112 complaints, mostly against <strong>the</strong><br />

police forces, 20 and claimed that 65 have been “disposed <strong>of</strong>.” O<strong>the</strong>r sources, however, assert<br />

that <strong>the</strong> NHRC has failed to make a single field visit, initiate an investigation <strong>of</strong> a complaint,<br />

or provide legal assistance to a victim <strong>of</strong> a human rights violation. 21<br />

The cases <strong>of</strong> human rights violations handled by <strong>the</strong> NHRC involved misuse <strong>of</strong> power by<br />

police authorities, torture <strong>of</strong> detainees or under trial prisoners, killing <strong>of</strong> civilians under police<br />

custody, abduction allegedly perpetrated by Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) 22 , killing in “cross<br />

fire”, and illegal arrest and detention. 23<br />

Yet, in addressing <strong>the</strong>se complaints, <strong>the</strong> most common action taken by <strong>the</strong> NHRC was to<br />

refer <strong>the</strong> case to ano<strong>the</strong>r government agency, usually <strong>the</strong> law enforcement <strong>of</strong>fice that ranks<br />

above and oversees <strong>the</strong> accused <strong>of</strong>ficers. The ranking law enforcement <strong>of</strong>ficers are expected to<br />

conduct an investigation and submit a report on <strong>the</strong>ir findings. The problem with this process<br />

is <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> partiality and conflict <strong>of</strong> interest. The people expected to conduct <strong>the</strong> enquiries<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ficers belonging to <strong>the</strong> very agencies to which <strong>the</strong> alleged human rights violators<br />

are attached. There is an obvious risk that <strong>the</strong> higher authorities may protect <strong>the</strong>ir ranks and<br />

institution ra<strong>the</strong>r than unveil <strong>the</strong> truth.<br />

An example <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conflict <strong>of</strong> interest that this practice enmeshes is that <strong>of</strong> referring human<br />

rights violation complaints against members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> police forces with <strong>the</strong> rank <strong>of</strong> Inspector<br />

primarily to <strong>the</strong> Office <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Inspector General <strong>of</strong> Police (IGP). This referral procedure is<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r mandated by The Police Officers (Special, Provisions) Ordinance, 1976 (Ordinance<br />

No. LXXXIV <strong>of</strong> 1976) 24 Clearly, <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> independent investigation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> claims is likely<br />

to result in a dismissal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> claim, or at best in a highly questionable finding.<br />

19. Ibid. pp. 2-3.<br />

20. Interview with NHRC Chair Justice Amirul Kabir Chowdhury. Dhaka, Bangladesh, 6 April 2010. Dhaka.<br />

21. Manpozer shortage cripples NHRC, The Daily Star, 21 April 2010, www.<strong>the</strong>dailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.phpnid<br />

=151605.<br />

22. The RAB, an elite force created by <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi government in March 2004, is in operating since June 2004. The objective is<br />

supposedly to curb organised crime. However, RAB is responsible for a number <strong>of</strong> extrajudicial executions (“death in crossfire”) and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is also an alarming number <strong>of</strong> deaths in RAB custody.<br />

23. Ibid. pp. 5-8.<br />

24. The Police Officers (Special, Provisions) Ordinance, 1976Ordinance No. LXXXIV <strong>of</strong> 1976. www.police.gov.bd/index5.phpcategory=23<br />

(Accessed: 8 August 2010).<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 9

For <strong>the</strong> NHRC to maintain its independence and impartiality, improvements in <strong>the</strong> conduct <strong>of</strong><br />

its work are necessary. Streng<strong>the</strong>ning its investigative functions and enhancing <strong>the</strong> capabilities<br />

<strong>of</strong> its staff are essential to more effectively fulfil its mandate <strong>of</strong> advancing and promoting<br />

human rights, especially <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impoverished and marginalized sections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population.<br />

In response to a UNDP-funded study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fledgling NHRC in 2008 that recommended a<br />

workforce <strong>of</strong> 128 members, six workers were hired. Recently, approval has been granted to<br />

hire 28 more staff members. 25<br />

25. Ibid., note 13.<br />

10 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

III. The Death Penalty<br />

in Bangladesh<br />

Crimes punishable by death<br />

A broad range <strong>of</strong> crimes are currently subject to <strong>the</strong> death penalty. These include crimes set<br />

out in <strong>the</strong> Penal Code 1860, such as:<br />

– waging war against Bangladesh (s.121),<br />

– abetting mutiny (s.132),<br />

– giving false evidence upon which an innocent person suffers death (s.194),<br />

– murder (s.302),<br />

– assisting <strong>the</strong> suicide <strong>of</strong> a child or insane person (s.305),<br />

– attempted murder by life-convicts (s.307),<br />

– kidnapping <strong>of</strong> a child under <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> ten (with intent to murder, grievously hurt, rape or<br />

enslave <strong>the</strong> child) and<br />

– armed robbery resulting in murder (s.396).<br />

In addition, o<strong>the</strong>r legislative regimes enumerate <strong>of</strong>fences punishable by death. The Special<br />

Powers Act 1974, which establishes emergency police powers to maintain national security,<br />

makes provision for <strong>the</strong> death penalty for <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences <strong>of</strong>:<br />

– sabotage (s.15),<br />

– hoarding <strong>of</strong> goods or dealing on <strong>the</strong> black market (s.25),<br />

– counterfeiting (s.25A), smuggling (s.25B), and<br />

– poisoning or contamination <strong>of</strong> consumables (s.25C) or attempt <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>of</strong>fences<br />

(s.25D).<br />

A range <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences related to firearms and explosives also attract <strong>the</strong> death penalty, 26 as do<br />

<strong>of</strong>fences under <strong>the</strong> Anti-Terrorism Ordinance 2008.<br />

Finally, a range <strong>of</strong> laws designed to prevent violence against women and children prescribe death<br />

as punishment. Under legislation known as <strong>the</strong> Women and Children Repression Prevention<br />

Act, passed in 2000, <strong>the</strong> death sentence is available for:<br />

– murder or attempted murder involving burning, poison or <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> acid (s.4),<br />

– causing grievous hurt by <strong>the</strong> above substances if eyesight or hearing capacity or face or<br />

breast or reproductive organs are damaged (s.4(2)(ka)),<br />

– trafficking <strong>of</strong> women and children for illegal or immoral acts (s.5 and 6),<br />

– kidnapping (s.8),<br />

– sexual assault <strong>of</strong> women or children occasioning death (s.9(2)),<br />

– committing dowry murder (s.11), and<br />

– maiming <strong>of</strong> children for begging purposes.<br />

26. The Arms Act 1878, s 20A (use <strong>of</strong> unlicensed firearms for murder); <strong>the</strong> Explosives Act 1884, s 12 (abetment or attempt to commit<br />

<strong>of</strong>fences punishable by death); <strong>the</strong> Explosive Substances Act 1908, s 3 (causing explosion likely to endanger life or property).<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 11

In total, twelve <strong>of</strong>fences under this law are punishable by <strong>the</strong> death sentence, <strong>of</strong> which two<br />

are simply attempted crimes. The Acid Crime Control Act 2002 makes <strong>the</strong> following crimes<br />

punishable by death: causing death by acid (s.4), causing hurt by acid in a way which totally<br />

or partially destroys eyesight, hearing capacity or defacing or destroying face, breasts or<br />

reproductive organs (s.5(ka)).<br />

The ICCPR expressly states in Article 6(2) that a sentence <strong>of</strong> death may be imposed only for<br />

<strong>the</strong> most serious crimes. The Human Rights Committee has stated that “<strong>the</strong> expression ‘most<br />

serious crimes’ must be read restrictively to mean that <strong>the</strong> death penalty should be a quite<br />

exceptional measure.” 27 In addition, <strong>the</strong> UN Safeguards guaranteeing protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights<br />

<strong>of</strong> those facing <strong>the</strong> death penalty state that crimes punishable by death should “not go beyond<br />

intentional crimes with lethal or o<strong>the</strong>r extremely grave consequences” (emphasis added). 28<br />

The UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions has fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

stated that “<strong>the</strong> death penalty should be eliminated for crimes such as economic crimes and<br />

drug related <strong>of</strong>fences.” 29 Following this line <strong>of</strong> statutory interpretation, <strong>the</strong> shocking breadth<br />

<strong>of</strong> crimes that attract <strong>the</strong> death penalty under Bangladeshi law breaches <strong>the</strong> ICCPR due to <strong>the</strong><br />

economic and non-lethal nature <strong>of</strong> several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crimes, such as dealing goods on <strong>the</strong> black<br />

market or counterfeiting.<br />

A General Comment on Article 6 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ICCPR, adopted in 1982, by <strong>the</strong> Human Rights<br />

Committee established that this article “refers generally to abolition [<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> death penalty] in<br />

terms which strongly suggest (...) that abolition is desirable. The Committee concludes that<br />

“all measures <strong>of</strong> abolition should be considered as progress in <strong>the</strong> enjoyment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right to<br />

life.” 30 One may consequently consider that <strong>the</strong> adoption <strong>of</strong> legislation providing for <strong>capital</strong><br />

punishment after signature and accession by Bangladesh to <strong>the</strong> ICCPR in 2000 goes against<br />

<strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Covenant, which is particularly <strong>the</strong> case for <strong>the</strong> Acid Crime Control Act <strong>of</strong><br />

2002 and <strong>the</strong> Anti-Terrorism Act <strong>of</strong> 2009.<br />

Mandatory Death Sentences<br />

Under <strong>the</strong> Women and Children Repression Prevention Act <strong>of</strong> 2000, causing death for dowry<br />

(s11(ka)) is a crime punishable with mandatory death penalty, in o<strong>the</strong>r words no o<strong>the</strong>r sentence<br />

is available.<br />

Mandatory death sentences are cause for grave concern as <strong>the</strong>y deprive <strong>the</strong> judiciary <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> discretion to consider extenuating circumstances relating to <strong>the</strong> crime or <strong>the</strong> accused.<br />

The obvious in<strong>justice</strong> that can result from a mandatory death sentence is illustrated in <strong>the</strong> case<br />

<strong>of</strong> State vs. Shukur Ali, decided in 1995, where <strong>the</strong> High Court Division confirmed <strong>the</strong> death<br />

sentence <strong>of</strong> a minor boy who was 14 years old when he committed <strong>the</strong> rape and murder <strong>of</strong> a<br />

7 year old girl, under s.6 <strong>of</strong> an earlier version <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Women and Children Repression Prevention<br />

Act, 1995. The Court noted that it was compelled to confirm <strong>the</strong> death sentence:<br />

“No alternative punishment has been provided for <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fence that <strong>the</strong> condemned prisoner<br />

has been charged and we are left with no o<strong>the</strong>r discretion but to maintain <strong>the</strong> sentence if we<br />

27. Human Rights Committee General Comment 6, para. 7.<br />

28. UN Economic and Social Council, 45th plenary meeting. Resolution 15 (1996) [Safeguards guaranteeing protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong><br />

those facing <strong>the</strong> death penalty]. (E/RES/1996/15). 23 July 1996.<br />

29. Report <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, UN Doc: E/CN.4/1996/4, at para. 556.<br />

30. UN Human Rights Committee General Comment 6 on <strong>the</strong> right to life (art. 6, par. 6), 30/04/1982.<br />

12 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

elieve that <strong>the</strong> prosecution has been able to prove <strong>the</strong> charge beyond reasonable doubt. This<br />

is a case, which may be taken as ‘hard cases make bad laws”. 31<br />

The Court proceeded to note that <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> convicted person, who was only 16 at <strong>the</strong> time<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> trial, would have meant that his sentence would have been commuted to life imprisonment<br />

had he been charged under <strong>the</strong> Penal Code which provides alternatives to <strong>the</strong> death<br />

sentence.<br />

On 16 May 2010, <strong>the</strong> High Court Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh declared<br />

unconstitutional such a provision providing for a mandatory death sentence. 32 The Court ruled<br />

that, regardless <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fence, legislation may not require that <strong>the</strong> death penalty<br />

is <strong>the</strong> only punishment available. This would impermissibly constrain <strong>the</strong> judiciary’s discretion<br />

under <strong>the</strong> constitution to consider <strong>the</strong> individual circumstances <strong>of</strong> each case, including<br />

<strong>the</strong> credibility <strong>of</strong> evidence and witnesses.<br />

<strong>FIDH</strong> and Odhikar welcome this landmark ruling, which contributes to restricting <strong>the</strong> scope<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> death penalty in <strong>the</strong> domestic legal system, as prescribed by international human rights<br />

standards. As a consequence, <strong>the</strong> legislator should amend all <strong>the</strong> laws establishing mandatory<br />

death sentences in order to provide for an alternative prison sentence when <strong>the</strong>re are extenuating<br />

circumstances. However, if it fails to do so, it remains to be seen how <strong>the</strong> courts <strong>of</strong> law <strong>of</strong><br />

Bangladesh will give effect to this ruling in practice.<br />

Available statistics on <strong>the</strong> death penalty<br />

Executions are not publicly reported in Bangladesh, unless it is related to a ‘sensational’ or<br />

‘political’ case. For example, <strong>the</strong> February 2010 hanging <strong>of</strong> 5 persons accused and tried for<br />

<strong>the</strong> murder <strong>of</strong> Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was widely reported; <strong>the</strong> same holds true <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 2007<br />

hanging <strong>of</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JMB who were accused in <strong>the</strong> 2005 bomb attacks on two judges<br />

at Jhalakathi.<br />

No <strong>of</strong>ficial statistics are available concerning <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> death sentences handed down,<br />

or <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> executions carried out. The <strong>FIDH</strong>/Odhikar mission was not able to obtain<br />

statistics regarding <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> condemnations and executions in Bangladesh from <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials met.<br />

According to a prison <strong>of</strong>ficial interviewed, <strong>the</strong>re are about 75,000 prisoners all over Bangladesh<br />

and 40-45 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m are convicted prisoners. In one district jail outside Dhaka, out <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> 2,300-2,400 estimated total prison inmates, 90 prisoners are on death row. 33<br />

31. Case name State vs Sukur Ali [9 (2004) BLC (HCD) 238].<br />

32. Writ Petition No. 8283 <strong>of</strong> 2005. BLAST vs State (Not yet reported)<br />

33. <strong>FIDH</strong>/Odhikar interviewed <strong>the</strong> IG Prisons on 07/04/2010<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 13

The following table includes <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> death sentences and executions reported in Amnesty<br />

International’s annual reports for <strong>the</strong> past five years, as well as <strong>the</strong> numbers reported by Hands<br />

Off Cain.<br />

Number <strong>of</strong> Executions, Bangladesh, 2005-2010 34<br />

Year Executions Convictions<br />

AI* HOC** AI HOC<br />

2005 7 5 120 218<br />

2006 - 4 - 197<br />

2007 6 6 93 94<br />

2008 5 4 185 175<br />

2009 5 3 65 86<br />

2010 - 5 - 29<br />

*AI = Amnesty International; ** HOC = Hands Off Cain.<br />

- = no statistics available.<br />

The scarcity <strong>of</strong> information and its contradictory nature according to <strong>the</strong> source illustrate <strong>the</strong><br />

lack <strong>of</strong> transparency <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> government <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh concerning <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> death penalty<br />

in <strong>the</strong> country. <strong>FIDH</strong> considers that <strong>the</strong> authorities <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh should guarantee transparency<br />

<strong>of</strong> data regarding <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> prisoners detained and those on death row. Bangladesh<br />

must also report <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> death sentences pronounced and executed every year, differentiated<br />

by gender, age, charges, etc. in order to allow for an informed public debate on <strong>the</strong><br />

issue. These statistics must be made public in order to allow both international and domestic<br />

scrutiny <strong>of</strong> compliance with international law.<br />

34. Amnesty International annual reports, searchable at www.amnesty.org/en/library and Hands Off Cain statistics on Bangladesh,<br />

searchable at www.hands<strong>of</strong>fcain.info/. Accessed 7 September 2010.<br />

14 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

IV. Administration<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Justice<br />

Police custody and arrest<br />

There are two kinds <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fences in Bangladesh criminal law: non-cognizable and cognizable.<br />

Cognizable <strong>of</strong>fences, as enumerated in Section 4(f) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Code <strong>of</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Procedure, 1898<br />

(Cr.P.C.), are those in which a police <strong>of</strong>ficer may arrest without a warrant and include crimes<br />

such as murder, robbery, <strong>the</strong>ft, rape, rioting and assault. Non-cognizable <strong>of</strong>fences, which<br />

include bribery and sedition, require a police <strong>of</strong>ficer to first obtain a warrant before making an<br />

arrest. Section 54 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Code <strong>of</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Procedure, 1898 (Cr.P.C.) enumerates nine grounds<br />

in which a police <strong>of</strong>ficer may arrest without a warrant.<br />

As stated by many human rights activists and lawyers met by <strong>the</strong> <strong>FIDH</strong>/Odhikar delegation<br />

in Bangladesh, police very <strong>of</strong>ten abuse this power <strong>of</strong> unwarranted arrest under Section 54.<br />

Several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nine circumstances enumerated in Section 54 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C. are drafted with<br />

such nebulous wording that <strong>the</strong>y facilitate this abuse <strong>of</strong> power. The Supreme Court itself has<br />

called for a revision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> code, especially Section 54(a), which allows unwarranted arrest<br />

upon “reasonable suspicion,” “reasonable complaint,” or “credible information” against “any<br />

person who has been concerned in any cognizable <strong>of</strong>fence.” This section is a virtual carte<br />

blanche for <strong>the</strong> police to abuse <strong>the</strong>ir power <strong>of</strong> arrest without a warrant due to <strong>the</strong> nebulous<br />

phrases “concerned in any cognizable <strong>of</strong>fence” and “reasonable suspicion.”<br />

As in o<strong>the</strong>r common law countries, statutory “reasonable suspicion” wording has been<br />

interpreted by <strong>the</strong> High Court Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bangladesh Supreme Court into an articulable<br />

standard, that <strong>the</strong> arresting <strong>of</strong>ficer had “actual knowledge <strong>of</strong> underlying facts that lead to <strong>the</strong><br />

suspicion.” 35 Unfortunately, however, this standard has not been enforced or applied by local<br />

courts or authorities, which has rendered <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court’s power <strong>of</strong> statutory interpretation<br />

impotent. The rules <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C. dealing with <strong>the</strong> investigation and arrest by police <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

facilitate <strong>the</strong> misuse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> arrest without a warrant.<br />

In Bangladesh, every criminal action commences with a First Information Report (FIR), lodged<br />

by <strong>the</strong> victim, relatives, or a witness. The FIR is a written or oral complaint to <strong>the</strong> investigating<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer who must lodge <strong>the</strong> complaint in writing in <strong>the</strong> police records per Section 154 <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C. In a case <strong>of</strong> a cognizable <strong>of</strong>fence, any <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> a police station may, without <strong>the</strong><br />

order <strong>of</strong> a Magistrate, investigate <strong>the</strong> matter. According to Mr. Arafat Amin, Advocate to <strong>the</strong><br />

Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh 36 , as well as several <strong>FIDH</strong> interlocutors, when a FIR is lodged<br />

in <strong>the</strong> police station, describing a cognizable <strong>of</strong>fence, <strong>the</strong> common practice is that <strong>the</strong> police<br />

immediately seek out and arrest <strong>the</strong> persons named in <strong>the</strong> FIR, regardless <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> suspects’<br />

involvement in <strong>the</strong> crime. Following <strong>the</strong> arrest, <strong>the</strong> suspect must be produced in front <strong>of</strong> a<br />

magistrate within 24 hours, per section 61 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C.<br />

35. BLAST and o<strong>the</strong>rs v. Bangladesh, 55 (2003) DLR (HCD) 363., accessible at www.blast.org.bd/index.phpoption=com_content&vi<br />

ew=article&id=214&Itemid=105.<br />

36. <strong>Criminal</strong> Responsibility for Torture: An Urgent Human Safeguard in Bangladesh, in <strong>Criminal</strong> Responsibility for Torture. A South Asian<br />

Perspective, Odhikar, Research Report 2004, p. 19 [11-25].<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 15

Several human rights activists and lawyers have told <strong>the</strong> <strong>FIDH</strong> that naming a person in a FIR is<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten a way for people to strike back at <strong>the</strong>ir enemies or perpetuate neighbourly squabbles. This<br />

practice <strong>of</strong> false, vengeful reporting is particularly common in acid throwing cases and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

cases falling under <strong>the</strong> laws protecting women and children, <strong>FIDH</strong> has been told. The nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> FIR and <strong>the</strong>ir accompanying improper police practices allow citizens to “manipulate”<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>justice</strong> system and to involve it in private conflicts.<br />

The newly elected President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court Bar Association, for example., stressed<br />

that “<strong>the</strong> investigation is not sufficient in criminal matters”, and that <strong>the</strong>re are many cases<br />

with fabricated evidences. It also appears that <strong>the</strong> investigating <strong>of</strong>ficers are understaffed, and<br />

not properly trained in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> criminal investigation. Several interlocutors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mission<br />

also regretted <strong>the</strong> political influence within <strong>the</strong> police.<br />

After <strong>the</strong> FIR has been submitted and an arrest is made, according to Article 33 (2) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Constitution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> People’s Republic <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh, Every person who is arrested and detained<br />

in custody shall be produced before <strong>the</strong> nearest magistrate within a period <strong>of</strong> twenty-four<br />

hours <strong>of</strong> such arrest, excluding <strong>the</strong> time necessary for <strong>the</strong> journey from <strong>the</strong> place <strong>of</strong> arrest to<br />

<strong>the</strong> court <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> magistrate, and no such person shall be detained in custody beyond <strong>the</strong> said<br />

period without <strong>the</strong> authority <strong>of</strong> a magistrate. Section 61 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C. requires that <strong>the</strong> defendant<br />

is brought in front <strong>of</strong> a magistrate within 24 hours <strong>of</strong> incarceration in order to determine<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r fur<strong>the</strong>r detention is necessary. Under Section 167 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C., however, magistrates<br />

can allow remand <strong>the</strong> case for a period not exceeding 15 days at <strong>the</strong> request <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficer.<br />

This infamous remand process has widely been denounced as ano<strong>the</strong>r vehicle for <strong>the</strong> abuse <strong>of</strong><br />

police power. In order to ask for fur<strong>the</strong>r detention in police custody, police must demonstrate<br />

that <strong>the</strong>re are grounds for believing that <strong>the</strong> accusation or information upon which <strong>the</strong> arrest is<br />

based is well-founded. However, as stated inter alia by Pr<strong>of</strong>. Shahdeen Malik, “it is common<br />

knowledge that Magistrates routinely allow this request for remand“. 37<br />

The remand period is critical because it opens <strong>the</strong> door to severe human rights violations.<br />

Ill-treatment, torture and extra-judicial killings in custody are commonplace. Much <strong>of</strong> this<br />

torture and abuse takes place because police hope to extract bail money from <strong>the</strong> accused<br />

during <strong>the</strong> detention period. This issue was addressed in <strong>the</strong> BLAST (Bangladesh Legal Aid<br />

and Services Trust, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest legal services NGOs in <strong>the</strong> country) judgement 38 <strong>of</strong><br />

2003, in which <strong>the</strong> High Court Division <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Supreme Court <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh called for <strong>the</strong><br />

strict adherence to Constitutional guarantees <strong>of</strong> due process and condemned <strong>the</strong> systematic<br />

police practices <strong>of</strong> torture and extortion.<br />

The Court in BLAST attempted to narrow <strong>the</strong> ambiguity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> terms “reasonable suspicion”<br />

and “concerned in any cognizable <strong>of</strong>fence” as requirements for arrest. The Court required <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer to record his suspicion and personal knowledge <strong>of</strong> facts implicating <strong>the</strong> accused <strong>of</strong><br />

criminal involvement. In order to curb excessive force, <strong>the</strong> police <strong>of</strong>ficer must also record <strong>the</strong><br />

existence and reason for any marks <strong>of</strong> injury on <strong>the</strong> person arrested, and take <strong>the</strong> person to<br />

<strong>the</strong> nearest hospital or government doctor for treatment. In order to comport with due process,<br />

if <strong>the</strong> person is not arrested from his residence or place <strong>of</strong> business, <strong>the</strong> police <strong>of</strong>ficer shall<br />

inform <strong>the</strong> nearest relation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> person over phone or <strong>through</strong> a messenger within one hour<br />

37. Shahdeen Malik, “Arrest and Remand: Judicial Interpretation and Police Practice“, Bangladesh Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Special Issue, p. 277.<br />

38. BLAST and o<strong>the</strong>rs, 55 (2003) DLR (HCD) 363.<br />

16 / <strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism

<strong>of</strong> bringing him to <strong>the</strong> police station. The police <strong>of</strong>ficer must also allow <strong>the</strong> person arrested to<br />

consult a lawyer <strong>of</strong> his choice if he so desires or to meet any <strong>of</strong> his nearest relations.<br />

As for <strong>the</strong> remand process, <strong>the</strong> court in <strong>the</strong> BLAST case condemned <strong>the</strong> police practice <strong>of</strong><br />

trying to “extort information or confession from <strong>the</strong> person arrested by physical or mental<br />

torture” as violating Article 35 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Constitution’s right to life and right to be free from selfincrimination.<br />

39 Magistrates must also take all three subsections <strong>of</strong> Section 167 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C.<br />

on remand into consideration when deciding if remand is proper, which include whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

investigation requires more than 24 hours, if <strong>the</strong>re are grounds for believing that <strong>the</strong> accusation<br />

or complaint is well founded, and if <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficer has submitted his “diary,” which must include<br />

<strong>the</strong> time and place <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> occurrence and <strong>the</strong> articulated reasons for <strong>the</strong> arrest.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> BLAST judgement is a very positive step towards a more effective right to liberty<br />

and a police custody without ill-treatment, torture and death custody, it is not sufficient to<br />

reform <strong>the</strong> law enforcement agencies and foster a culture <strong>of</strong> respect for human rights amongst<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir members.<br />

Indeed, according to Odhikar figures, 68 persons have been tortured in 2009 by members <strong>of</strong><br />

law enforcing agencies, and <strong>the</strong> BLAST decision itself cites <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> 38 people in custody. 40<br />

The case <strong>of</strong> Mr. Mahmudur Rahman, <strong>the</strong> Acting Editor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> daily Amar Desh, unfortunately<br />

illustrates <strong>the</strong> abuse <strong>of</strong> power by <strong>the</strong> police on remand. Mr. Rahman, with whom <strong>the</strong> <strong>FIDH</strong><br />

mission met during its stay in Bangladesh, was arrested by <strong>the</strong> police on 2 June 2010, after<br />

<strong>the</strong> daily’s publisher filed a fraud case against him allegedly at <strong>the</strong> instigation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Security Intelligence (NSI). When he was produced before a court at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> his remand,<br />

Mr. Mahmudur Rahman alleged he has been tortured in detention. 41 Subsequently, Mr. Rahman<br />

has been charged with sedition for allegedly meeting with people attempting to overthrow <strong>the</strong><br />

government in 2006, which allows for indefinite remand. Writers and reporters, detained for<br />

sedition, report that mistreatment, malnutrition and torture are common. 42 He has also been<br />

charged under section 6 (1) <strong>of</strong> Anti Terrorism Act 2009.<br />

Every month, <strong>the</strong> Bangladeshi newspapers report cases <strong>of</strong> extra-judicial killings and custodial<br />

deaths in Dhaka. End <strong>of</strong> June 2010, three persons – Mizanur Rahman, Mujibur Rahman and<br />

Babul Kazi – died while in police custody. In <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Mizanur Rahman, police allegedly<br />

shot and killed him upon failure to produce money that police had demanded from him. 43 It is<br />

clear, <strong>the</strong>refore, that torture and custodial deaths are facilitated not only by <strong>the</strong> provisions <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Cr.P.C. but also by <strong>the</strong> widespread corruption in <strong>the</strong> ranks <strong>of</strong> law enforcing agencies.<br />

After <strong>the</strong> three custodial deaths mentioned above, <strong>the</strong> High Court asked <strong>the</strong> Dhaka Metropolitan<br />

Police Commissioner to submit inquest reports on <strong>the</strong>se cases and to turn in a report by <strong>the</strong><br />

end <strong>of</strong> July on measures to prevent lock-up deaths. The High Court also asked <strong>the</strong> Government<br />

to explain, within two weeks, why it does not take punitive action against <strong>the</strong> police <strong>of</strong>ficers<br />

39. Art 35(4) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Constitution <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh: “No person accused <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong>fence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself”.<br />

40. Odhikar, Human Rights Report 2009, p. 17.<br />

41. See “Mahumudur alleges torture in remand”, bdnews24.com, 12 June 2010, available at www.bdnews24.com/details.phpid<br />

=164100&cid=2.<br />

42. “Detained editor Mahmudur Rahman now facing sedition charge”, IFEX, 10 June 2010, available at www.ifex.org/bangladesh/<br />

2010/06/10/rahman_sedition_charge.<br />

43. See Odhikar Human Rights Monitoring Report, 1st August 2010, p. 2 and “Cops slammed for custodial deaths“, The Daily Star,<br />

6 July 2010, available on www.<strong>the</strong>dailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.phpnid=145551<br />

<strong>BANGLADESH</strong>: <strong>Criminal</strong> <strong>justice</strong> <strong>through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>prism</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>capital</strong> punishment and <strong>the</strong> fight against terrorism / 17

esponsible for <strong>the</strong> custodial deaths. When this report was not submitted, <strong>the</strong> police commissioner<br />

Md Muniruzzaman was charged with contempt <strong>of</strong> court, but was subsequently cleared <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> contempt charges after <strong>of</strong>fering an “unqualified apology” and suspending <strong>the</strong> investigating<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer suspected <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> custodial deaths. 44<br />

The trial phase and violations <strong>of</strong> due process<br />

Bail<br />

The important procedural safeguard <strong>of</strong> bail is denied for many <strong>of</strong>fences which could lead to <strong>the</strong><br />

death penalty. Section 497 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Code <strong>of</strong> <strong>Criminal</strong> Procedure provides that an accused shall<br />

not be released on bail if <strong>the</strong>re appears reasonable grounds for believing that he is guilty <strong>of</strong><br />

an <strong>of</strong>fence punishable with death. The special laws for <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> women and children<br />

provide that all <strong>of</strong>fences under those Acts are non-bailable, which means that bail is per se<br />

unavailable unless, at <strong>the</strong> judge’s discretion, <strong>the</strong> court decides to grant bail. 45<br />

As discussed fur<strong>the</strong>r below, criminal trials in Bangladesh regularly last for months or years.<br />

As a result, <strong>the</strong> presumption against bail for <strong>of</strong>fences which involve <strong>the</strong> death penalty can<br />

result in a de facto pre-trial conviction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> accused who may spend months or years in jail<br />

before ultimately being acquitted at trial.<br />

Filing <strong>of</strong> false cases<br />

Perhaps because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> presumption against bail for <strong>the</strong>se serious <strong>of</strong>fences, laws which specify<br />

crimes punishable by death penalty appear to be regularly abused by <strong>the</strong> filing <strong>of</strong> false cases.<br />

Both government and academics have recognised that <strong>the</strong> Women and Children Repression<br />

Prevention Act <strong>of</strong> 2000 is <strong>of</strong>ten misused by falsely implicating <strong>the</strong> relatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> husband. 46<br />

Such cases may be filed out <strong>of</strong> a desire to take revenge for a personal grievance or for property<br />

gain. The Bangladesh Law Commission, established by Parliament in order to revise <strong>the</strong> civil<br />

and criminal codes, has recommended amending <strong>the</strong> law so that relatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> husband cannot<br />

be arrested if <strong>the</strong>re is no prima facie case against <strong>the</strong>m. In our view, this recommendation has<br />

merit in that an articulable reasonable suspicion must always exist for a proper arrest to occur<br />

under international and Bangladeshi guarantees <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> right fair trial and to due process.<br />

All relatives <strong>of</strong> persons condemned to death stressed <strong>the</strong> following elements: when someone is<br />

named in a FIR, s/he is automatically prosecuted. The relatives generally believe that revenge<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten behind those FIR. They also denounce that political connections play an important<br />

role at local level in criminal cases: people with relevant connections in political parties at<br />

local level can avoid conviction. Those who are able to bribe can also benefit from a more<br />

favourable outcome.<br />

Media pressure can also introduce an element <strong>of</strong> arbitrariness into Bangladesh’s sentencing<br />

regime, in violation <strong>of</strong> international law: judges sometimes feel obliged to condemn to death<br />

due to such pressure, as reported by several persons interviewed by <strong>the</strong> mission, including<br />

44. “Enough with custodial deaths, says HC”, bdnews24, 1 June 2010, available at www.bdnews24.com/details.phpid=<br />

163013&cid=2.<br />

45. See section 19 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Women and Children Repression Prevention Act <strong>of</strong> 2000 and section 15 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Acid Crime Control Act 2002.<br />

46. Report <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Law Commission on amendment <strong>of</strong> certain sections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nari O Shishu Nirjaton Daman Ain 2000, SI No 77; Sharmin<br />

Jahan Tania, ‘Special <strong>Criminal</strong> Legislation for Violence Against Women and Children – A Critical Examination’ (2007) Bangladesh Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> Law 199.<br />