Expert Recommendations for Optimizing Outcomes ... - Wounds

Expert Recommendations for Optimizing Outcomes ... - Wounds

Expert Recommendations for Optimizing Outcomes ... - Wounds

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

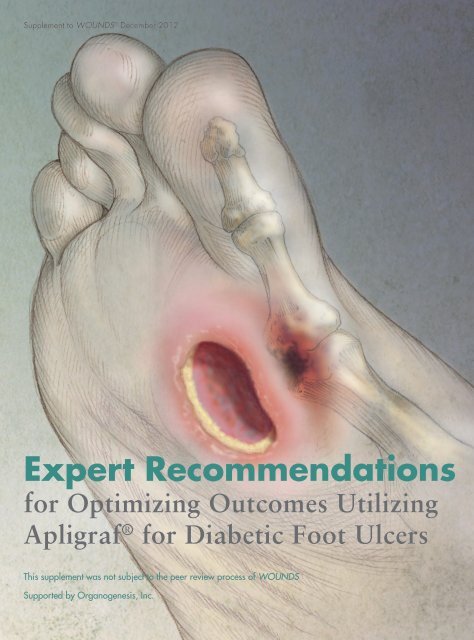

Supplement to WOUNDS ® December 2012<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing<br />

Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers<br />

This supplement was not subject to the peer review process of WOUNDS<br />

Supported by Organogenesis, Inc.

Table of Contents<br />

Purpose of this Supplement............................................................................................................4<br />

PART 1<br />

Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers<br />

1.1 The Challenge of Diabetic Foot Ulcers..................................................................................6<br />

1.2 Pathophysiology of Wound Healing in DFUs. .......................................................................7<br />

1.3 Initial Evaluation of Patients with a DFU... ............................................................................8<br />

1.4 Estimating the Likelihood of DFU Healing..........................................................................10<br />

1.5 Conventional Wound Therapies...........................................................................................11<br />

1.6 Evaluating Response to Conventional Therapy.....................................................................13<br />

Cover Photo Credit<br />

Photo Researchers Picture Number: BH3877<br />

Credit: Michele S. Graham / Photo Researchers, Inc<br />

License: Rights Managed<br />

Images and Text Copyright © 2012 Photo Researchers, Inc. All Rights Reserved.<br />

2 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Table of Contents<br />

PART 2<br />

Advanced Therapy of DFUs with Apligraf ®<br />

2.1 Evidence-Based Selection of Advanced Therapy <strong>for</strong> DFUs.. ...................................................15<br />

2.2 Apligraf: Efficacy and Proposed Mechanism............................................................................17<br />

2.3 Initiating Apligraf Therapy.....................................................................................................18<br />

2.4 Evaluating Response to Apligraf & Reapplications.................................................................19<br />

2.5 Summary...............................................................................................................................20<br />

, LLC<br />

<br />

www.hmpcommunications.com. 130-218<br />

©2012 HMP Communications, LLC (HMP). All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part prohibited. Opinions expressed by authors,<br />

contributors, and advertisers are their own and not necessarily those of HMP Communications, the editorial staff, or any member of the<br />

editorial advisory board. HMP Communications is not responsible <strong>for</strong> accuracy of dosages given in articles printed herein. The appearance<br />

of advertisements in this journal is not a warranty, endorsement, or approval of the products or services advertised or of their effectiveness,<br />

quality, or safety. HMP Communications disclaims responsibility <strong>for</strong> any injury to persons or property resulting from any ideas or products<br />

referred to in the articles or advertisements. Content may not be reproduced in any <strong>for</strong>m without written permission. Reprints of articles are<br />

available. Rights, permission, reprint, and translation in<strong>for</strong>mation is available at: www.hmpcommunications.com.<br />

HMP Communications, LLC (HMP) is the authoritative source <strong>for</strong> comprehensive in<strong>for</strong>mation and education servicing healthcare professionals.<br />

HMP’s products include peer-reviewed and non–peer-reviewed medical journals, national tradeshows and conferences, online programs,<br />

and customized clinical programs. HMP is a wholly owned subsidiary of HMP Communications Holdings LLC. Discover more about HMP’s<br />

products and services at www.hmpcommunications.com.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 3

Purpose of this Supplement<br />

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are one of the most common complications of diabetes mellitus (DM) and are associated<br />

with significant morbidity and mortality. Management of DFUs is complex and requires a systematic approach to<br />

achieve successful outcomes. The care of DFUs has evolved in recent years as new therapeutic options have become<br />

available with varying levels of evidence supporting their use. Education about the latest developments in the evaluation and<br />

treatment of DFUs has sometimes not kept up with the pace of this progress, especially with regards to advanced therapies,<br />

such as cell therapy, growth factors, negative-pressure therapy, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.<br />

Six experienced wound care specialists reviewed the current status of evidence-based evaluation and therapy of DFUs with<br />

a focus on the optimal use of Apligraf ® , an allogeneic bilayered living-cell-based product that has FDA approval <strong>for</strong> treatment<br />

of DFUs.<br />

The objectives of this meeting were two-fold:<br />

(1) To highlight key aspects of the evaluation and evidence-based conventional therapy of DFUs<br />

(2) To make recommendations regarding the optimal use of Apligraf as evidence-based advanced therapy in the<br />

care of DFUs<br />

The overarching goal of both these objectives is to empower clinicians caring <strong>for</strong> patients with DFUs to optimize clinical<br />

outcomes by providing an educational resource that is concise and useful in their clinical practices.<br />

In this supplement, Part 1 | Initial Evaluation of Diabetic Foot Ulcers addresses the first objective and Part 2 | Advanced Therapy<br />

of DFUs with Apligraf addresses the second objective.<br />

Of note, this paper is not intended as an exhaustive review of DFU management. Rather, based on the group discussions<br />

during the meeting and the meeting participants’ extensive clinical experience with DFU management, the intention is to<br />

focus on a select number of issues that the group felt was most critical to achieving optimal clinical outcomes in DFU patients.<br />

The meeting participants provided a variety of perspectives including academic settings, teaching hospitals, and standalone<br />

wound care clinics. Robert Kirsner, MD, PhD, Professor and Vice Chairman of the Department of Dermatology<br />

and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine led the group discussions. Following the<br />

conference, a first draft summary of the group discussions was written and then extensively edited and finalized utilizing<br />

input from all meeting participants.<br />

Meeting Participants<br />

Dr. Robert S. Kirsner (Moderator)<br />

Dr. Kirsner is a tenured professor, Vice Chairman, and<br />

holds the endowed Stiefel Laboratories Chair in Dermatology<br />

in the Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous<br />

Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.<br />

He currently serves as director of the University of<br />

Miami Hospital Wound Center and chief of Dermatology<br />

at the University of Miami Hospital. Dr. Kirsner is also a<br />

recently retired board member of the Wound Healing Society<br />

and is past president of the Association <strong>for</strong> the Advancement<br />

of Wound Care. He co-directed the Symposium <strong>for</strong><br />

Advanced wound Care (SAWC) <strong>for</strong> the past 18 years. In<br />

addition to career development awards and industry sponsored<br />

funding, he is a recipient of NIH, ACS, CDC funding<br />

<strong>for</strong> his research. Independent of books, book chapters and<br />

abstracts, he has published over 350 articles.<br />

Dr. Desmond Bell<br />

Dr. Desmond Bell is the co-founder and executive<br />

director of the “Save A Leg, Save A Life” Foundation, a<br />

multidisciplinary non-profit organization dedicated to the<br />

reduction in lower extremity amputations and improving<br />

wound healing outcomes through evidence-based methodology<br />

and community outreach. He is a board certified<br />

wound specialist (CWS/American Board of Wound Management)<br />

and has served on their Board of Directors since<br />

2009. He serves on the Board of Directors of the Association<br />

<strong>for</strong> the Advancement of Wound Care, the Barbara<br />

Bates-Jensen Wound Reach Foundation, the Communications<br />

Committee of the Jacksonville Chapter of the American<br />

Diabetes Association and the Conference Planning<br />

Committee of the Symposium on Advanced Wound Care.<br />

He is also a member of the Wound Healing Society and<br />

the Vascular Disease Foundation/PAD Coalition. Dr. Bell<br />

has been in private practice in Jacksonville, Florida since<br />

1997 and is on staff at Memorial Hospital of Jacksonville, St.<br />

Vincent’s Medical Center Southside and Specialty Hospital<br />

of Jacksonville.<br />

4 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Dr. Gary Gibbons<br />

Dr. Gibbons is medical director <strong>for</strong> South Shore Hospital<br />

Center <strong>for</strong> Wound Care and Hyperbaric Medicine and Professor<br />

of Surgery at the Boston University School of Medicine.<br />

Trained as a vascular surgeon, Dr. Gibbons was the first director<br />

of the Joslin-Beth Israel Deaconess Foot Center in Boston<br />

and his career has centered on diabetic patients with lower extremity<br />

wounds, especially those complicated by vascular disease.<br />

He has published and spoken extensively on the subject<br />

and has been honored with the Pecoraro (ADA), Olmos, and<br />

Georgetown Distinguished Achievement awards <strong>for</strong> his work.<br />

Dr. Bill Ennis<br />

Dr. Ennis is a professor of clinical surgery and chief of the<br />

section of wound healing and tissue repair at the University of<br />

Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System. His active areas<br />

of research include healing outcomes measures, microcirculation,<br />

macrophage function and the impact of stem cells on<br />

wound healing.<br />

Dr. Arti Masturzo<br />

Dr. Masturzo is a published educator who has dedicated<br />

her career to the advancement of wound care best practices<br />

and the development of comprehensive wound care programs.<br />

She completed her internal medicine residency at the University<br />

of Cincinnati and went on to pursue a practice focusing<br />

entirely on the care of chronic wounds. She is currently the<br />

Medical Director of Comprehensive Wound Programs <strong>for</strong> Tri-<br />

Health Associates, overseeing inpatient and outpatient wound<br />

care, including hyperbarics, <strong>for</strong> multiple hospitals and clinics<br />

in greater Cincinnati. In addition, she is the Corporate Director<br />

of Medical Affairs of Accelecare Wound Centers. Dr.<br />

Masturzo is board-certified in internal medicine and undersea<br />

hyperbaric medicine.<br />

Dr. Gary Rothenberg<br />

Dr. Rothenberg is a board certified podiatrist, certified diabetes<br />

educator and certified wound specialist who currently<br />

serves as director of resident training and attending podiatrist<br />

at the Department of Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Miami,<br />

Florida. A graduate of the Ohio College of Podiatric<br />

Medicine, he completed 3 years of residency training at the<br />

University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.<br />

His previous private practice experience and now academic<br />

practice have focused on conservative and surgical management<br />

of the diabetic foot.<br />

Conflicts of Interest<br />

Dr. Kirsner indicates advisory board participation with Organogenesis, Shire, Healthpoint, and KCI.<br />

Dr. Bell indicates he is a member of the Speaker’s Bureau of Organogenesis and Cordis and serves as a consultant<br />

with ev3, Cook, and Healiance.<br />

Dr. Gibbons indicates he is a consultant, speaker, and participates in a clinical experience program <strong>for</strong> Organogenesis, and<br />

that he is principal investigator <strong>for</strong> a venous leg ulcer study sponsored by Celleration.<br />

Dr. Ennis indicates he is a consultant to Organogenesis, KCI, and Accelecare wound centers.<br />

Dr. Masturzo indicates she is a member of the Speaker’s Bureau of Organogenesis and KCI. She has also served as a<br />

consultant to Shire.<br />

Dr. Rothenberg indicates he is a member of the Speaker’s Bureau <strong>for</strong> Organogenesis and Healthpoint.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

This article is supported by a grant from Organogenesis. The authors would like to thank Ed Perper, MD, and James Radke,<br />

PhD, <strong>for</strong> editorial and manuscript assistance. This supplement is provided as a courtesy to the readers of WOUNDS. This<br />

supplement was not subject to the peer review process of WOUNDS.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 5

PART 1<br />

Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers<br />

1.1 The Challenge of Diabetic Foot Ulcers<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

DFUs are a common complication in patients with DM.<br />

The lifetime risk of developing a DFU is 15% to 25% and<br />

the prevalence of DFUs among diabetics is 4% to 10%. 1<br />

The morbidity and mortality associated with DFUs is<br />

very high. For example, 85% of leg amputations are preceded<br />

by DFUs 1 and more than 60% of nontraumatic lower<br />

extremity amputations per<strong>for</strong>med in the United States each<br />

year occur secondary to complications of DM. 2 Mortality<br />

rates following amputation are alarmingly high: up to 40%<br />

at 1 year and 80% at 5 years. 1<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, DFUs are notoriously difficult to heal.<br />

The healing rate even with good standard-of-care treatment<br />

is only 31% at 20 weeks 3 (Figure 1). Moreover, DFUs<br />

are frequently inadequately managed due to multiple factors<br />

including blunted signs of infection, limited understanding<br />

of current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches,<br />

and insufficient resources. 4<br />

Group Discussion<br />

The seriousness of DFUs is often underestimated by both<br />

clinicians and patients. A critical first step is <strong>for</strong> everyone involved<br />

to fully understand and explicitly acknowledge that<br />

achieving complete healing represents a significant challenge<br />

in a high-risk patient. This should motivate both the<br />

wound care practitioner and the patient to take all necessary<br />

steps to maximize the probability of success. It is important<br />

to not underestimate this disease as success is typically<br />

harder than many perceive. Educating patients about the<br />

challenge of healing their DFU will ideally motivate them<br />

to strictly comply with all therapeutic interventions; poor<br />

compliance is an important factor that often limits the success<br />

of therapy. Importantly, wound care clinicians should<br />

understand that even with well-delivered standard care of<br />

DFUs, the probability of complete healing is relatively low;<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e from the very start of treatment, clinicians should<br />

anticipate that advanced therapy will be required in many<br />

patients to achieve complete healing.<br />

%<br />

Weighted Mean Healing Rate<br />

100%<br />

75%<br />

25%<br />

0%<br />

24.2%<br />

30.9%<br />

12 Weeks 20 Weeks<br />

N = 4 trials<br />

N = 6 trials<br />

Time Elapsed<br />

Suggested Reading<br />

• Consensus Development Conference on Diabetic Foot Wound<br />

Care: 7-8 April 1999, Boston, Massachusetts. American Diabetes<br />

Association. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(8):1354-1360.<br />

• Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers<br />

in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293(2):217-228.<br />

• Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic neuropathic<br />

foot ulcers receiving standard treatment. Diabetes Care.<br />

1999;22(5):692-695.<br />

Figure 1. Healing rates of control groups from<br />

meta-analysis of 10 randomized clinical trials of<br />

standard DFU care. 3 <br />

Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers<br />

receiving standard treatment. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(5):692-695.<br />

• Maderal AD, Vivas AC, Zwick TG, Kirsner RS. Diabetic foot<br />

ulcers: evaluation and management. Hosp Pract (Minneap).<br />

2012;40(3):102-115.<br />

• Ramsey SD, Newton K, Blough D, et al. Incidence, outcomes,<br />

and cost of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes.<br />

Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):382-387. n<br />

6 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

1.2 Pathophysiology of Wound Healing in DFUs<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

Acute wounds heal through a normal highly regulated<br />

process of cell replication, migration, protein synthesis,<br />

matrix deposition, and organization. In an acute wound,<br />

multiple growth factors, cytokines, and cells—including<br />

keratinocytes and fibroblasts—work in concert to heal the<br />

wound completely. 5-7 DFUs are chronic wounds that fail<br />

to heal in a regulated and systematic manner due to multiple<br />

abnormal physiologic, anatomic, and cellular factors:<br />

(1) decreased angiogenic response; (2) neuropathy; (3)<br />

ischemia; (4) endothelial dysfunction; and (5) increased<br />

susceptibility to wound infection 5 (Figure 2).<br />

In addition, in DFUs there is poor and disorganized regulation<br />

of the cytokines, growth factors, proteases, extracellular<br />

matrix components, and cells needed to achieve<br />

complete wound closure 8,9 : (1) keratinocyte migration and<br />

proliferation is impaired 10 ; (2) fibroblast response to growth<br />

factors 9 and the ability to synthesize collagen is impaired 11 ;<br />

and (3) there is a relative deficiency of tissue inhibitors<br />

of matrix metalloproteinases, which results in degradation<br />

of the extracellular matrix. 8,12,13 All these pathophysiologic<br />

factors contribute to the poor healing rates observed in<br />

patients with DFUs.<br />

Group Discussion<br />

All wound care practitioners should understand the<br />

multiple pathophysiologic defects that contribute to poor<br />

healing rates of DFUs. By therapeutically addressing as<br />

many of these factors as possible, the likelihood of wound<br />

healing can be increased. For example, clinicians must<br />

assess and reassess <strong>for</strong> ischemia, infection, and other factors<br />

throughout the course of management that may slow or<br />

prevent healing. If healing stalls, some advanced therapies<br />

may address the growth factor, cytokine, and cellular<br />

abnormalities that interfere with healing of DFUs.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

• Brem H, Young J, Tomic-Canic M, et al. Clinical efficacy<br />

and mechanism of bilayered living human skin equivalent<br />

(HSE) in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Surg Technol Int.<br />

2003;11:23-31.<br />

Figure 2. Pathophysiologic factors contributing to<br />

poor healing rates of DFUs.<br />

• Werner S, Krieg T, Smola H. Keratinocyte–fibroblast<br />

interactions in wound healing. J Invest Dermatol.<br />

2007;127(5):998-1008.<br />

• Ghahary A, Ghaffari A. Role of keratinocyte–fibroblast<br />

cross-talk in development of hypertrophic scar. Wound Repair<br />

Regen. 2007;15(suppl 1):S45-S53. n<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 7

1.3 Initial Evaluation of Patients with a DFU<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

Several published clinical guidelines exist to assist wound<br />

care practitioners with proper evaluation and management of<br />

DFUs, including those from the Infectious Diseases Society<br />

of America, 14 the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons,<br />

15 the Wound Healing Society, 16 and the International<br />

Working Group on the Diabetic Foot Editorial Board. 17<br />

Common to these guidelines is the recommendation <strong>for</strong> a<br />

meticulous initial clinical evaluation of every patient with a<br />

DFU. Particular attention should be on the following issues:<br />

1) peripheral artery disease; 2) neuropathy; 3) nutritional status;<br />

4) wound infection, including osteomyelitis; and 5) hyperglycemia<br />

(Figure 3).<br />

In addition, a wound-specific history must be obtained,<br />

including location, duration, inciting event or trauma,<br />

previous ulcers and recurrences, hospitalization, previous<br />

wound care treatments, off-loading technique, wound response<br />

to treatment, patient compliance, family or social<br />

problems that are interfering with care, previous foot trauma<br />

or surgery, presence of edema, and history of Charcot<br />

foot and its treatment. 15<br />

Classification of DFUs is generally predictive of outcomes<br />

and may facilitate treatment (Figure 4). The most commonly<br />

used classification system is the Wagner system, which divides<br />

foot lesions into 6 grades based on the depth of the wound<br />

and extent of tissue infection and necrosis. However, the<br />

Wagner system does not consider the roles of infection, ischemia,<br />

and other factors. The University of Texas San Antonio<br />

(UTSA) system associates lesion depth with both ischemia<br />

and infection; this system has been validated and is generally<br />

predictive of outcome. 15<br />

If possible, the initial evaluation of the DFU should involve<br />

a multidisciplinary team that includes wound care professionals<br />

and, when indicated, diabetologists or endocrinologists,<br />

surgeons (vascular and podiatric), nurses, nutritionists,<br />

and pedorthotists. 4<br />

Assess Patient<br />

• H & P<br />

• Glycemic control<br />

• Nutritional evaluation<br />

• Immune status<br />

• Neurological evaluation<br />

• Vascular evaluation<br />

• Psychosocial evaluation<br />

Assess DFU<br />

• Duration<br />

• Size (~area in cm 2 Estimate Likelihood of<br />

)<br />

Succesful Closure &<br />

• Depth<br />

Discuss with Patient<br />

• Location<br />

• Charcot<br />

• Soft tissue infection & osteomyelitis<br />

• Consider advanced testing & imaging<br />

Appropriate<br />

Interventions<br />

Standard Therapy<br />

<strong>for</strong> all DFUs<br />

Debridement Infection Control Off-Loading Appropriate Dressing<br />

Figure 3. Clinical algorithm <strong>for</strong> initial assessment of patients with DFUs.<br />

Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline <strong>for</strong> the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis.<br />

2012;54(12):e132-173.<br />

Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al. Diabetic foot disorders. A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot Ankle Surg. 2006;45(5 Suppl):S1-66.<br />

Steed DL, Attinger C, Colaizzi T, et al. Guidelines <strong>for</strong> the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14(6):680-692.<br />

Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC; International Working Group on Diabetic Foot Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011.<br />

Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 Suppl 1:225-231.<br />

8 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Wagner Classification System of DFUs<br />

Grade Lesion<br />

0 No open lesions: may have de<strong>for</strong>mity or cellulitis<br />

1 Superficial ulcer<br />

2 Deep ulcer to tendon or joint capsule<br />

3 Deep ulcer with abscess, osteomyelitis, or joint sepsis<br />

4 Local gangrene – <strong>for</strong>efoot or heel<br />

5 Gangrene of entire foot<br />

University of Texas Classification System of DFUs<br />

Stage<br />

A<br />

Pre- or post-ulcerative<br />

lesions, completely<br />

epithelized<br />

Grade<br />

0 I II III<br />

Superficial wound not<br />

involving tendon,<br />

capsule, or bone<br />

Wound penetrating in<br />

tendon or capsule<br />

Wound penetrating in bone<br />

or joint<br />

B Infected Infected Infected Infected<br />

C Ischemic Ischemic Ischemic Ischemic<br />

D Infected and ischemic Infected and ischemic Infected and ischemic Infected and ischemic<br />

Figure 4. Wagner and University of Texas Classification Systems <strong>for</strong> chronic wounds.<br />

Group Discussion<br />

Published evidenced-based guidelines should provide a<br />

roadmap <strong>for</strong> care <strong>for</strong> DFU. Clinicians should follow the<br />

recommendations of the published clinical guidelines <strong>for</strong><br />

initial evaluation of patients with a DFU. Too often inadequate<br />

evaluation or treatment of peripheral arterial disease<br />

(PAD), or in more severe instances, critical limb ischemia,<br />

is a major factor that slows or prevents complete DFU<br />

healing. Assessment of vascular status is critical prior to<br />

proceeding with other elements of care in patients with a<br />

DFU. Another important issue related to the initial evaluation<br />

of patients with a DFU is precise baseline measurement<br />

of wound size so that the response to treatment<br />

can be reassessed quantitatively and accurately (Section 1.6<br />

below: “Evaluating Response to Conventional Therapy”).<br />

Suggested Reading<br />

• Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious<br />

Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline <strong>for</strong> the<br />

diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect<br />

Dis. 2012;54(12):e132-173.<br />

• Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al. Diabetic foot disorders.<br />

A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot Ankle<br />

Surg. 2006;45(5 Suppl):S1-66.<br />

• Steed DL, Attinger C, Colaizzi T, et al. Guidelines <strong>for</strong> the treatment<br />

of diabetic ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14(6):680-692.<br />

• Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC; International Working<br />

Group on Diabetic Foot Editorial Board. Practical guidelines<br />

on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011.<br />

Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 Suppl 1:225-231.<br />

• Snyder RJ, Kirsner RS, Warriner RA, et al. Consensus recommendations<br />

<strong>for</strong> advancing the standard of care <strong>for</strong> treating<br />

neuropathic foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Ostomy Wound<br />

Manage. 2010;56(suppl 4):S1-S24.<br />

• Gibbons GW, Shaw PM. Diabetic Vascular Disease: Characteristics<br />

of Vascular Disease Unique to the Diabetic Patient. Semin<br />

Vasc Surg. 2012;25:89-92. n<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 9

1.4 Estimating the Likelihood of DFU Healing<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

The likelihood of complete DFU healing is determined<br />

by multiple factors, both patient-related and wound-related.<br />

Important patient-related factors include vascular status,<br />

nutritional status, neurologic status, presence and severity of<br />

soft tissue infection, osteomyelitis, Charcot, and other factors,<br />

including glycemic control. Wound-related factors that have<br />

been demonstrated in prospective studies to have predictive<br />

value include the size, duration, depth, and grade of the<br />

DFU. Larger lesions (>2 cm 2 ), chronic lesions (>6 months<br />

- 12 months), deeper lesions, and higher grade lesions are<br />

associated with reduced likelihood of complete healing despite<br />

continued conventional therapy.<br />

Margolis et al 18 pooled data from the standard care arms<br />

of 5 clinical trials to determine the effect of wound size and<br />

duration on the probability of healing (Figure 5). Healing rates<br />

were lower in patients with larger wounds and longer duration<br />

wounds. For example, wounds 12 months, which had<br />

only a 26% probability of healing (n = 252 patients).<br />

Group Discussion<br />

Many DFUs heal slowly and many will not heal with<br />

standard treatment. Healthcare providers should be keenly<br />

aware of the serious challenges involved in treating any<br />

DFU successfully. Patients and families must be educated<br />

about the poor prognosis <strong>for</strong> healing in general and the<br />

critical importance of strict compliance in order to maximize<br />

the probability of success. The studies above clearly<br />

show that even in patients with DFUs that are small and<br />

of shorter duration, many lesions will not heal with conventional<br />

therapy, eg, in the Margolis trial described above,<br />

even among patients with small DFUs that were present<br />

<strong>for</strong> less than 6 months more than half (57%) did not heal at<br />

20 weeks. Of course, in larger wounds of greater duration<br />

the likelihood of healing is even lower. There<strong>for</strong>e, from the<br />

first day of treatment onwards, all patients need to understand<br />

that DFUs are very difficult to heal with conventional<br />

therapy and that most patients will ultimately need<br />

to receive evidence-based advanced therapy to maximize<br />

their odds of achieving complete healing.<br />

In addition, the group believed that in many cases the<br />

likelihood of successful healing is overestimated by both<br />

clinicians and patients and that greater awareness of the<br />

challenges DFUs present may lead to better clinical decisions<br />

and higher compliance.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

• Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Santanna J, Strom BL, Berlin JA. Risk<br />

factors <strong>for</strong> delayed healing of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers:<br />

a pooled analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1531-1535. n<br />

100%<br />

% Healed Within 20 Weeks<br />

75%<br />

50%<br />

25%<br />

% Healed<br />

0 %<br />

4 12 12<br />

()*+,#-./0# ()*+,#1*234)+# ()*+,#-./0#3+,#<br />

Wound Size 1*234)+#<br />

& Duration<br />

Wound Size<br />

cm 2<br />

Wound Duration<br />

months<br />

cm 2 & months<br />

Sample Size: 347 123 116 202 88 189 120 252<br />

Figure 5. Cumulative healing rates within 20 weeks of care of DFUs.<br />

Adapted from Margolis DJ, et al. Risk factors <strong>for</strong> delayed healing of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: a pooled analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1531-1535.<br />

10 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

1.5 Conventional Wound Therapies<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

Management of DFUs is complex and<br />

requires a systematic approach to achieve<br />

more consistent and successful outcomes. 4<br />

This includes addressing multiple issues: 1)<br />

peripheral artery disease; 2) neuropathy; 3)<br />

nutritional status; 4) ulcer and bone infection;<br />

and 5) glycemic control. Detailed discussion<br />

of these factors is beyond the scope of this<br />

paper. Addressing peripheral artery disease is<br />

particularly important. Depending on the<br />

population being treated, peripheral ischemia<br />

contributes to poor wound healing in 50% to<br />

60% of patients with DFUs.<br />

In addition, the wound itself must be treated<br />

directly. Below is a brief review of the<br />

clinical evidence supporting the administration<br />

of conventional wound therapies that are<br />

mandated in all patients with DFUs:<br />

Be<strong>for</strong>e debridement<br />

After debridement<br />

Offloading.<br />

The main mechanism by which DFUs<br />

develop is due to increased, sustained and/<br />

or repetitive trauma in the setting of peripheral<br />

neuropathy. Distributing and minimizing<br />

pressure in the affected area is crucial<br />

to achieve healing. Pressure offloading can<br />

be achieved with foot inserts, therapeutic<br />

shoes, casts, or by surgical procedures. The<br />

total-contact cast is considered the gold standard<br />

<strong>for</strong> the management of plantar DFUs as<br />

studies have shown the highest healing rates<br />

compared with other offloading devices. 19,20<br />

However, it is recognized that limitations to<br />

use of total-contact casting exist and alternatives<br />

are available which have been shown to<br />

be effective. 21,22 Poor patient compliance often<br />

limits success of offloading due in part to the fact that these<br />

devices limit per<strong>for</strong>mance of daily activities and the stability of<br />

patients’ gaits. 23 There<strong>for</strong>e, the best device is one with high adherence<br />

that best adapts to the patient, permitting continuous<br />

use and effective decrease in pressure.<br />

Figure 6. Examples of DFUs be<strong>for</strong>e and after surgical debridement.<br />

Photo credit: Arti B Masturzo MD ABPM/UHM<br />

Medical Director Advanced Wound Programs<br />

Bethesda North & Good Samaritan Hospitals<br />

Cincinnati, OH<br />

Debridement.<br />

Debridement is considered essential in DFU care although<br />

this is supported by data from secondary analyses of<br />

controlled trials per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>for</strong> reasons other than debridement.<br />

24 When undertaken, appropriate debridement includes<br />

removal of excess callus and necrotic tissue and likely results<br />

in reduction of unresponsive cells in the wound bed and<br />

edge, bacterial biofilms and excess matrix metalloproteinases.<br />

Among the different types of debridement (surgical, enzymatic,<br />

autolytic, mechanical, and biologic), surgical debridement<br />

is preferred. (See Figure 6 <strong>for</strong> examples of DFUs be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

and after surgical debridement.) Steed et al found topical<br />

application of a growth factor with frequent debridement<br />

increased the likelihood of healing as did debridement with-<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 11

out growth factor application, but to a lesser extent. 25 The<br />

“Debridement Per<strong>for</strong>mance Index,” which evaluates the<br />

adequacy of debridement of the wound and wound edges,<br />

was found to be an independent factor of wound closure. 26<br />

Finally, it has been suggested that frequent debridement<br />

of DFUs may increase wound healing and closure rates,<br />

which may be in part due to superior overall care provided<br />

to patients. 27<br />

Dressings.<br />

Important wound bed preparation principles are moisture<br />

balance, minimization of inflammation, infection control, and<br />

epithelial edge advancement. The goal is to promote healing<br />

via epidermal migration, angiogenesis, and connective tissue<br />

synthesis. The type of dressing will be dependent on the<br />

wound size, depth, location, the presence of eschar or slough,<br />

the amount of exudates, the wound margins, the need <strong>for</strong> adhesiveness,<br />

concern <strong>for</strong> infection, and con<strong>for</strong>mability. 5 However,<br />

there is not enough evidence to suggest that one dressing is<br />

more effective than another. Currently, no ideal dressing exists<br />

that possesses all properties ideal <strong>for</strong> all wound types. 4<br />

Group Discussion<br />

Standard wound management will succeed in healing<br />

only a percentage of DFUs. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, optimal standard<br />

wound care is not always provided to all patients due<br />

to poor adherence to guidelines, diminished compliance,<br />

inadequate education of wound care practitioners, lack of<br />

close follow-up, insufficient resources, and other factors. Offloading<br />

is grossly underutilized, which is un<strong>for</strong>tunate given<br />

the strong evidence supporting its role in promoting wound<br />

healing. Practitioners are encouraged to remember that contact-casting<br />

is the most strongly supported by clinical evidence<br />

and is there<strong>for</strong>e considered the “gold standard.”<br />

Close follow-up with weekly reassessment is the standard<br />

of care; un<strong>for</strong>tunately, not all practitioners follow this guideline.<br />

Early, aggressive, and diligent management of DFUs is not<br />

only in the best interest of the patient but is also cost effective<br />

since it potentially prevents costly complications.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

• Brem H, Sheehan P, Boulton AJM. Protocol <strong>for</strong> treatment of<br />

diabetic foot ulcers. Amer J Surg. 2004;187(suppl):1S-10S.<br />

• Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012 Infectious<br />

Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline <strong>for</strong> the<br />

diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect<br />

Dis. 2012;54(12):e132-173.<br />

• Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al. Diabetic foot<br />

disorders. A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot<br />

Ankle Surg. 2006;45(5 Suppl):S1-66.<br />

• Steed DL, Attinger C, Colaizzi T, et al. Guidelines <strong>for</strong><br />

the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Wound Repair Regen.<br />

2006;14(6):680-692.<br />

• Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC; International Working<br />

Group on Diabetic Foot Editorial Board. Practical guidelines<br />

on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011.<br />

Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 (suppl 1):225-231.<br />

• Snyder RJ, Kirsner RS, Warriner RA, et al. Consensus recommendations<br />

<strong>for</strong> advancing the standard of care <strong>for</strong> treating<br />

neuropathic foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Ostomy Wound<br />

Manage. 2010;56(suppl 4):S1-S24.n<br />

12 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

1.6 Evaluating Response to Conventional Therapy<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

Patients with DFUs should be followed closely with weekly<br />

visits. A 2012 study comparing 206 patients with Wagner<br />

grade 1 or 2 DFUs who had weekly vs every-other-week<br />

visits found that weekly follow-up reduced the median time<br />

to wound closure by more than 50% (28 days vs 66 days). 43<br />

Several studies have shown that re-evaluation 4 weeks after<br />

initiation of standard wound healing therapy is clinically<br />

useful. These studies demonstrate that if wound size has not<br />

decreased by at least 50% by the 4th week of treatment, the<br />

likelihood of complete wound healing using the same treatment<br />

approach is very low. 28-30 For example, in a study of 704<br />

patients, only 18% of DFUs that were not healing adequately<br />

at 4 weeks healed at 12 weeks, whereas 58% of DFUs that<br />

were healing adequately at 4 weeks did so. 28 In another study,<br />

patients with DFUs receiving 4 weeks of conventional therapy<br />

whose wounds did not reduce in size by more than 53%<br />

had a decreased likelihood of healing at 12 weeks. 30 In addition<br />

to percent wound size reduction, Robson et al examined<br />

the data from 11 clinical trials and observed that by week<br />

4, the trajectories of the wounds that eventually would heal<br />

versus those that did not heal could be differentiated. 31 The<br />

Standard Therapy of DFU<br />

Reassess DFU within 4 Weeks<br />

• Wound healing trajectory<br />

• % area reduction<br />

Healing<br />

adequately<br />

Not healing<br />

adequately<br />

Follow-up<br />

Address factors<br />

interfering<br />

with healing<br />

• Ulcer infection<br />

• Osteomyelitis<br />

• Ischemia<br />

• Glycemic control<br />

• Inadequate offloading<br />

• Poor nutrition<br />

• Other factors<br />

Complete<br />

closure<br />

Evidence-based<br />

advanced<br />

therapy<br />

Figure 7. Clinical algorithm <strong>for</strong> initial assessment of patients with DFUs.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 13

Wound Healing Society’s guidelines recommend a change in<br />

treatment if wound size reduction is not observed at 4 weeks<br />

of conventional therapy. 16<br />

Group Discussion<br />

The evidence in favor of following DFU patients weekly<br />

is strong. Once the patient with a DFU is started on standard<br />

wound therapies, response to therapy should be re-evaluated<br />

at no later than 4 weeks. It is mandatory to per<strong>for</strong>m serial<br />

wound size measurements in all cases; but in real-world settings<br />

this is not always done. Although a ≥ 50% reduction<br />

in wound size is desirable and moderately predictive of the<br />

likelihood of healing, the overall trajectory of wound healing<br />

is most important. Other factors such as initial size, presence<br />

of infection, and quality of granulation tissue, in addition to<br />

percentage wound size reduction, should be considered in<br />

assessing the overall trajectory of wound healing. A suggested<br />

algorithm <strong>for</strong> follow-up evaluation is shown in Figure 7.<br />

If the clinician assesses that the wound healing trajectory<br />

is inadequate at 4 weeks, reassessment of the wound should<br />

be per<strong>for</strong>med and evidence-based advanced therapy should<br />

be considered. It is also important to note that the trials described<br />

above indicated that a sizeable proportion of patients<br />

(42% in one study 30 ) who are healing adequately at 4 weeks<br />

will ultimately fail to completely heal; these patients will also<br />

require advanced therapy.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

• Coerper S, Beckert S, Küper MA, Jekov M, Königsrainer<br />

A. Fifty percent area reduction after 4 weeks of treatment<br />

is a reliable indicator <strong>for</strong> healing--analysis of a single-center<br />

cohort of 704 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complications.<br />

2009;23:49-53.<br />

• Margolis DJ, Hoffstad O, Gelfand JM, Berlin JA. Surrogate<br />

end points <strong>for</strong> the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot<br />

ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1696-1700.<br />

• Sheehan P, Jones P, Casselli A, Giurini JM, Veves A. Percent<br />

change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week<br />

period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week<br />

prospective trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1879-1882.<br />

• Robson MC, Hill DP, Woodske ME, Steed DL. Wound healing<br />

trajectories as predictors of effectiveness of therapeutic<br />

agents. Arch Surg. 2000;135(7):773-777. n<br />

14 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

PART 2<br />

Advanced Therapy of DFUs with Apligraf<br />

2.1 Evidence-Based Selection of<br />

Advanced Therapy <strong>for</strong> DFUs<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

In many cases, standard DFU therapy is not sufficient to<br />

heal the wound. The appropriate use of advanced therapies<br />

in chronic, nonhealing wounds, can prevent limb loss,<br />

as well as improve quality of life <strong>for</strong> patients. 4 The use of<br />

advanced therapies is currently included in evidence-based<br />

treatment guidelines and algorithms <strong>for</strong> DFUs. 16<br />

At present there are only three products that are approved<br />

by the FDA <strong>for</strong> treatment of DFUs based on the<br />

results of rigorous clinical studies:<br />

1) Apligraf ® — bilayered (fibroblast/keratinocyte)<br />

cell-based product 32<br />

2) Dermagraft ® — human-fibroblast-derived<br />

dermal substitute 33<br />

3) Regranex ® — platelet-derived growth factor 34<br />

Level 1<br />

RCTs*<br />

Highest Level of Evidence<br />

Level 2<br />

COHORT<br />

StuDies<br />

Level 3<br />

Case-Controlled<br />

Studies<br />

Level 4<br />

Case Series<br />

Level 5<br />

Case Report or<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> Opinion<br />

Lowest Level of Evidence<br />

* RCT = randomized clinical trial<br />

Figure 8. The Centre <strong>for</strong> Evidence-Based Medicine: levels of clinical evidence.<br />

Adapted from Centre <strong>for</strong> Evidence-based Medicine. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspxo=1025. Accessed August 22, 2011.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 15

The FDA differentiates between wound dressings,<br />

which are intended to manage wounds and are classified<br />

as “non-interactive,” and cell-based wound care therapies,<br />

which are intended to heal wounds and are classified as<br />

“interactive.” To gain FDA approval <strong>for</strong> the treatment of<br />

DFUs, each of the above products was evaluated in large<br />

randomized multicenter clinical trials per<strong>for</strong>med in a DFU<br />

patient population.<br />

In contrast, many wound dressings and human tissue<br />

products receive a “510(K) Clearance,” which does not require<br />

clinical data and <strong>for</strong> which even preclinical efficacy<br />

studies are typically not per<strong>for</strong>med. 38<br />

The Centre <strong>for</strong> Evidence-Based Medicine published<br />

a “Levels of Evidence” document to help define a process<br />

<strong>for</strong> determining the value of clinical evidence-based on its<br />

source 35 (Figure 8). This pyramid ranks evidence from the<br />

highest (Level 1: randomized controlled trials) to the lowest<br />

(Level 5: expert opinion or case report). This process provides<br />

a guide to clinicians in their decision making to determine<br />

the merits of published clinical data.<br />

Group Discussion<br />

DFUs are a serious complication of DM associated with<br />

high morbidity, including limb loss and increased risk of mortality.<br />

Practitioners owe it to their patients to utilize the most<br />

proven therapies to maximize the likelihood of achieving successful<br />

healing, thereby potentially preventing additional complications.<br />

This commitment requires using evidence-based<br />

therapies that are supported by the highest level of scientific<br />

evidence, ie, randomized clinical trials. In real-world settings<br />

evidence-based medicine is sometimes delayed or not used as<br />

well as it should be. 39<br />

When a patient with a DFU fails to show wound progression<br />

with standard care (Section 1.6 above Evaluating Response<br />

to Therapy), transition to an evidence-based advanced therapy<br />

is appropriate. Three wound healing products have received<br />

FDA or postmarketing approval by the FDA <strong>for</strong> the treatment<br />

of DFUs: Apligraf, Dermagraft, and Regranex. Discussion of<br />

each of these products is beyond the scope of this paper. The<br />

main point here is that when new wound products become<br />

available, clinicians should inquire what level of clinical evidence<br />

supports their use. In the “hierarchy of scientific evidence,”<br />

randomized clinical trials represent the highest level of<br />

evidence while expert opinion and case reports represent the<br />

lowest level.<br />

Suggested Reading<br />

• Apligraf [prescribing in<strong>for</strong>mation].<br />

Canton MA: Organogenesis Inc; December 2010.<br />

• Dermagraft [prescribing in<strong>for</strong>mation]. Westpoint CT: Advanced<br />

Biohealing;2012.<br />

• Regranex (becaplermin) [prescribing in<strong>for</strong>mation].Fort<br />

Worth, TX: Healthpoint Biotherapeutics; 2012.<br />

• Veves A, Falanga V, Armstrong DG, Sabolinski ML, Apligraf<br />

Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study. Graftskin, a human skin equivalent,<br />

is effective in the management of noninfected neuropathic<br />

diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective randomized multicenter<br />

clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):290–295.<br />

• Marston WA, Hanft J, Norwood P, Pollak R, Dermagraft<br />

Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. The efficacy and safety<br />

of Dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic<br />

foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1701–1705.<br />

• Wieman TJ, Smiell JM, Su Y. Efficacy and safety of a topical<br />

gel <strong>for</strong>mulation of recombinant human platelet-derived<br />

growth factor-BB (becaplermin) in patients with chronic<br />

neuropathic diabetic ulcers: a phase III randomized<br />

placebo-controlled double-blind study. Diabetes Care.<br />

1998;21(5):822–827.<br />

• Centre <strong>for</strong> Evidence-based Medicine. http://www.cebm.<br />

net/index.aspxo=1025. Accessed August 22, 2011.<br />

• Maderal AD, Vivas AC, Zwick TG, Kirsner RS. Diabetic foot<br />

ulcers: evaluation and management. Hosp Pract (Minneap).<br />

2012;40(3):102-115. n<br />

16 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

2.2 Apligraf: Efficacy and Proposed Mechanism<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

Apligraf is a bioengineered allogeneic bilayered living-cellbased<br />

product that is FDA-approved <strong>for</strong> treatment of DFUs of<br />

greater than 3 weeks duration. It consists of an epidermal layer<br />

of human keratinocytes overlying a dermal layer of human fibroblasts<br />

in a collagen matrix. Although the precise mechanism<br />

by which Apligraf promotes wound healing is not known, the<br />

mechanism of action is believed to be primarily related to its<br />

ability to modulate the healing response through the delivery of<br />

cytokines and growth factors (Figure 9).<br />

Apligraf was evaluated <strong>for</strong> treatment of DFUs in a randomized<br />

controlled trial by Veves et al 36 in which patients with chronic<br />

neuropathic DFUs (plantar, medial and lateral aspects of the foot)<br />

were randomized to receive up to 5 weekly applications of Apligraf<br />

(n=112) plus standard care or standard care alone (n=96).<br />

Standard care consisted of saline moistened gauze, wound debridement<br />

and offloading. Patients in the Apligraf group had<br />

higher rates of complete healing than those in the control group<br />

by 12 weeks (56% Apligraf, 38% control, P=0.0042). In addition,<br />

the median time to complete closure was reduced in the<br />

Apligraf group (65 days vs 90 days, P=0.0026).<br />

Similar results were observed in a second randomized controlled<br />

trial by Edmonds et al, 37 a multicenter randomized<br />

controlled trial in which patients with DFUs received Apligraf<br />

(n=33) or standard wound care (n=39). While this study was<br />

terminated prematurely <strong>for</strong> non-scientific reasons, at 12 weeks<br />

twice as many Apligraf subjects had achieved complete wound<br />

closure compared to conventional therapy subjects (52% vs 26%,<br />

P=0.049). Rates of adverse events were similar in the Apligraf<br />

and control groups in both of these trials.<br />

Group Discussion<br />

Use of Apligraf as an advanced treatment <strong>for</strong> DFUs is supported<br />

by two randomized clinical trials, which provides a high<br />

level of evidence <strong>for</strong> its use. Overall healing rates and the time<br />

to complete healing were substantially improved compared to<br />

standard wound therapy. From a pathophysiologic standpoint,<br />

this clinical response is understandable since Apligraf provides<br />

the cells (fibroblasts and keratinocytes), growth factors, and cytokines<br />

that are believed to play important roles in wound healing.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

• Apligraf [prescription in<strong>for</strong>mation]. Canton MA: Organogenesis<br />

Inc; December 2010.<br />

• Veves A, Falanga V, Armstrong DG, Sabolinski ML, Apligraf<br />

Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study. Graftskin, a human skin equivalent, is<br />

effective in the management of noninfected neuropathic diabetic<br />

foot ulcers: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical trial.<br />

Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):290–295.<br />

• Edmonds M; European and Australian Apligraf Diabetic Foot<br />

Ulcer Study Group. Apligraf in the treatment of neuropathic<br />

diabetic foot ulcers. Int J Low Extrem <strong>Wounds</strong>. 2009;8(1):11-18.<br />

• Kirsner RS. The science of bilayer cell therapy. <strong>Wounds</strong>. 2005<br />

(suppl):6-9. n<br />

Function 1<br />

Angiogenesis<br />

Growth, development,<br />

and differentiation<br />

Inflammation<br />

Proliferation<br />

Growth Factor or<br />

Cytokine*<br />

PDGF-A‡<br />

PDGF-B‡<br />

VEGF‡<br />

IGF-1<br />

IGF-2<br />

TGF-ß1<br />

TGF-ß3<br />

IL-1a‡<br />

IL-6‡<br />

IL-8‡<br />

IL-11‡<br />

FGF-1<br />

FGF-2<br />

FGF-7<br />

TGF-a‡<br />

Human 2<br />

Human 2<br />

Apligraf 2<br />

Keratinocytes † Fibroblasts †<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

3<br />

*As measured by mRNA levels † Cells were grown in monolayer cultures ‡ Cytokines and growth factors were also detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.<br />

1<br />

Barrientos S, et al. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:585-601 2<br />

Brem H, et al. Surg Technol Int. 2003;11:23-31<br />

Figure 9. Growth factors and cytokines identified in human keratinocytes, human fibroblasts, and Apligraf.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 17

2.3 Initiating Apligraf Therapy<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

The technique used to apply various wound therapies, including<br />

Apligraf, varies among different practitioners. However,<br />

since the goal of evidence-based therapy is to replicate<br />

the results of clinical studies in real-world clinical care, below<br />

is a summary of selected study entry criteria and application<br />

techniques employed in the 2 randomized controlled trials<br />

of Apligraf:<br />

Veves et al study (2001). 36 Study patients included patients<br />

with a full-thickness neuropathic DFU on the plantar, lateral<br />

or medial surface of the foot of ≥3 weeks duration and a<br />

post-debridement ulcer size between 1 and 16 cm 2 ; without<br />

signs of clinical infection at the ulcer site or active Charcot’s<br />

disease; and, with a good vascular supply as indicated by an<br />

audible dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis pulses and ABI<br />

>0.65. The ulcer was debrided and irrigated with saline prior<br />

to initial application of Apligraf, which was placed directly<br />

over the ulcer site. Any excess edge was trimmed to fit the<br />

ulcer. The site was covered with a saline moistened non-adherent<br />

primary dressing (Tegapore) and secured with hypoallergenic<br />

tape. The wound was then covered with a layer of<br />

dry gauze, a layer of petrolatum gauze, and Kling ® .<br />

Edmonds et al study (2009). 37 Study patients had a full-thickness<br />

DFU of at least 4 weeks duration; with a surface area between<br />

1 and 16 cm 2 ; limited to the plantar <strong>for</strong>efoot region;<br />

with no signs of infection; and, with an adequate vascular<br />

supply to the target extremity. All patients received standard<br />

care therapies, including sharp debridement, saline-moistened<br />

dressings, and nonweight-bearing regimen. Apligraf<br />

was applied directly on the ulcer and Mepitel ® , a porous<br />

wound contact layer, was applied as a primary non-adherent<br />

dressing. Secondary dressings were also applied.<br />

Group Discussion<br />

What types of DFUs are appropriate <strong>for</strong> Apligraf Apligraf is<br />

appropriate <strong>for</strong> treatment of neuropathic DFUs, including<br />

large and deep ulcers (partial- and full-thickness ulcers). Ulcers<br />

at any location on the foot—including the plantar surface—are<br />

appropriate <strong>for</strong> Apligraf. Although Charcot disease<br />

was excluded in the clinical trials, with appropriate offloading<br />

this is not a contraindication to treatment with Apligraf.<br />

There is insufficient evidence to make recommendations<br />

regarding the use of Apligraf in patients with exposed bone<br />

or tendon, despite reports of clinical success. Frankly infected<br />

ulcers should not be treated and significant bioburden<br />

reduced, but optimization of granulation should not delay<br />

needed treatment.<br />

How should the wound be prepared Careful and complete<br />

sharp debridement followed by irrigation is essential. This<br />

may provide <strong>for</strong> a healing milieu and reduce bacterial load.<br />

How should Apligraf be applied to the ulcer Apligraf should<br />

be applied directly to the ulcer bed leaving a border (~5<br />

mm) beyond the edge of the ulcer. No evidence exists to<br />

suggest differences in outcomes between different types of<br />

dressings. Detailed directions regarding the application of<br />

Apligraf are beyond the scope of this paper.<br />

What post-Apligraf application measures are recommended<br />

Adhering Apligraf is critical, which is typically achieved<br />

with Steri-Strips TM , but other methods can be utilized. Negative<br />

pressure wound therapy may augment Apligraf wound<br />

bed interaction in highly exudative wounds. It is extremely<br />

important that offloading be continued.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

•Apligraf [prescription in<strong>for</strong>mation]. Canton MA: Organogenesis<br />

Inc; December 2010.<br />

• Veves A, Falanga V, Armstrong DG, Sabolinski ML, Apligraf<br />

Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study. Graftskin, a human skin equivalent,<br />

is effective in the management of noninfected neuropathic diabetic<br />

foot ulcers: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical<br />

trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):290–295.<br />

• Zaulyanov L, Kirsner RS. A review of a bi-layered living cell<br />

treatment (Apligraf) in the treatment of venous leg ulcers and<br />

diabetic foot ulcers. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(1):93-98.<br />

• Graftskin (Apligraf) in neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. <strong>Wounds</strong>.<br />

2000;12(5 suppl A):33A-36A.<br />

• Steinberg JS. Putting bilayered cell therapy to use. <strong>Wounds</strong>.<br />

2005 (Suppl):10-14. n<br />

18 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

2.4 Evaluating Response to Apligraf & Reapplications<br />

Review of Evidence<br />

In the randomized controlled trial of Apligraf by Veves et<br />

al, 36 DFU patients in the treatment group could have Apligraf<br />

reapplied at 4 weekly follow-up visits following the initial<br />

application, up to 5 applications. If Apligraf appeared to cover<br />

the wound at these follow-up visits, no reapplication was per<strong>for</strong>med.<br />

The average number of Apligraf applications was 3.9<br />

(range: 1 to 5); 9% of patients required one application, 10%<br />

two applications, 13% three applications, 15% four applications,<br />

and 53% five applications.<br />

In the randomized controlled trial of Apligraf by Edmonds<br />

et al, 37 all patients were followed weekly <strong>for</strong> clinical assessment<br />

of the target ulcer and, if necessary, debridement of the wound.<br />

The Apligraf group could have additional monthly applications<br />

of Apligraf at week 4 and week 8 if the wound was judged to<br />

not be healing, <strong>for</strong> a maximum of 3 applications. In the treatment<br />

group, 13 of the 33 subjects required only 1 application,<br />

15 received 2 applications, and 5 received 3 applications.<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, in these controlled studies a majority of patients<br />

required multiple applications of Apligraf. This is<br />

consistent with findings from several small studies with different<br />

wound types that showed limited persistence. DNA<br />

evidence of Apligraf was short-lived, typically 3 weeks to 6<br />

weeks after application. 40-42<br />

Reassess<br />

Weekly<br />

Apligraf Application Healing #1<br />

adequately<br />

Application #2<br />

in 1 to 3 weeks<br />

H<br />

E<br />

Application #3<br />

in 1 to 3 weeks<br />

A<br />

Address factors<br />

interfering with healing<br />

No<br />

Wound<br />

healing<br />

progressing<br />

L<br />

• Ulcer infection<br />

• Osteomyelitis<br />

• Ischemia<br />

• Glycemic control<br />

• Inadequate offloading<br />

• Poor nutrition<br />

• Other factors<br />

Factors above<br />

addressed<br />

Yes<br />

Yes<br />

Application #4<br />

in 1 to 3 weeks<br />

Application #5<br />

in 1 to 3 weeks<br />

E<br />

D<br />

Figure 10. Clinical algorithm <strong>for</strong> Apligraf management of patients with DFUs.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 19

Group Discussion<br />

As with standard care of DFUs, patients treated with<br />

Apligraf should continue to be followed up on a weekly<br />

basis. Based on the available data and clinical experience,<br />

dosing of Apligraf should be undertaken as follows (Figure<br />

10): Initial Apligraf application (Apligraf #1) can be<br />

followed by reapplication (Apligraf #2) 1 to 3 weeks later.<br />

After an additional 1 to 3 weeks, Apligraf reapplication can<br />

be considered again (Apligraf #3). Apligrafs #2 and #3 can<br />

be applied even if healing is not progressing because the<br />

trajectory of healing may not become evident during the<br />

initial phase of therapy. However, if after 3 applications the<br />

wound is not progressing, reevaluate the patient <strong>for</strong> factors<br />

that may be interfering with healing, especially ischemia,<br />

ulcer infection, osteomyelitis, inadequate off-loading, poor<br />

nutritional status, and poor glycemic control. If these factors<br />

are under control, the patient should be considered <strong>for</strong><br />

2 additional applications (Apligraf #4 and Apligraf #5) to<br />

maintain the trajectory of healing. If these factors are not<br />

under control, they should be addressed be<strong>for</strong>e proceeding<br />

with additional applications. A maximum of 5 Apligraf applications<br />

is considered one course of therapy. The goal of<br />

treatment is complete closure of the DFU.<br />

Suggested Readings<br />

• Marston WA; Dermagraft Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study<br />

Group. Risk factors associated with healing chronic diabetic<br />

foot ulcers: the importance of hyperglycemia. Ostomy<br />

Wound Manage. 2006;52(3):26-32.<br />

• Apligraf [prescribing in<strong>for</strong>mation]. Canton MA:<br />

Organogenesis Inc; December 2010. n<br />

2.5 Summary<br />

The care of patients with a DFU requires careful attention to critical elements to optimize the potential <strong>for</strong> successful<br />

treatment. Thorough assessment of the patient, especially vascular status and the presence of soft tissue and bone infection,<br />

will lead to accurate staging of patients. Once peripheral arterial disease and infection have been either excluded or<br />

addressed, vigilance in offloading is the most important aspect of standard care. Coupled with debridement and appropriate<br />

dressing selection, conscientious weekly evaluation is recommended. Should a patient fail to improve by 4 weeks<br />

of care, reassessment is warranted as is consideration of advanced therapy.<br />

Three products have received FDA approval <strong>for</strong> the treatment of DFUs that have not responded to conventional therapy,<br />

Apligraf, Dermagraft and Regranex. Apligraf, a bilayered living-cell-based product, is supported by two randomized<br />

clinical trials showing benefit and effectiveness data demonstrating clinical utility. Optimally, wounds should be debrided<br />

and fastidious offloading continued as serial applications every 1 to 3 weeks of Apligraf are applied. If the wound has not<br />

responded after three applications, reassess factors that may be interfering with healing be<strong>for</strong>e proceeding with the two<br />

additional applications.<br />

Patients with DFUs are at risk <strong>for</strong> limb loss and death. The seriousness of this problem cannot be overstated and the<br />

best results are achieved with a thorough evidenced-based process of care. n<br />

20 <strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers

References<br />

1. Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing<br />

foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA.<br />

2005;293(2):217-228.<br />

2. American Diabetes Association. Data from the<br />

2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet (released Jan.<br />

26, 2011). http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/diabetes-statistics/.<br />

Accessed August 22, 2011.<br />

3. Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic<br />

neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard<br />

treatment. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(5):692-695.<br />

4. Maderal AD, Vivas AC, Zwick TG, Kirsner RS.<br />

Diabetic foot ulcers: evaluation and management.<br />

Hosp Pract (Minneap). 2012;40(3):102-115.<br />

5. Brem H, Young J, Tomic-Canic M, et al. Clinical<br />

efficacy and mechanism of bilayered living human<br />

skin equivalent (HSE) in treatment of diabetic<br />

foot ulcers. Surg Technol Int. 2003;11:23-31.<br />

6. Werner S, Krieg T, Smola H. Keratinocyte–fibroblast<br />

interactions in wound healing. J Invest<br />

Dermatol. 2007;127(5):998-1008.<br />

7. Ghahary A, Ghaffari A. Role of keratinocyte–fibroblast<br />

cross-talk in development of hypertrophic<br />

scar. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(suppl<br />

1):S45-S53.<br />

8. Lobmann R, Schultz G, Lehnert H. Proteases<br />

and the diabetic foot syndrome: mechanisms<br />

and therapeutic implications. Diabetes<br />

Care.2005;28(2):461-471.<br />

9. Harding KG, Moore K, Phillips TJ. Wound chronicity<br />

and fibroblast senescence-implications <strong>for</strong><br />

treatment. lnt Wound J. 2005;2(4):364-368.<br />

10. Martin P. Wound healing--aiming <strong>for</strong> perfect skin<br />

regeneration. Science. 1997;276(5309):75-81.<br />

11. Herrick SE, Ireland GW, Simon D, McCollum<br />

CN, Ferguson MW. Venous ulcer fibroblasts compared<br />

with normal fibroblasts show differences<br />

in collagen but not fibronectin production under<br />

both normal and hypoxic conditions. J Invest Dermatol.<br />

1996;106(1):187-193.<br />

12. Vaalamo M, Leiva T, Saarialho-Kere U. Differential<br />

expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases<br />

(lIMP-I. -2, -l, and -4) in normal and aberrant<br />

wound healing. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(7):795-802.<br />

13. Muller M, Trocme C, Lardy B, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases<br />

and diabetic foot ulcers: the ratio<br />

of MMP-1 and TlMP-1 is a predictor of wound<br />

healing. Diabet Med. 2006;25(4):419-426.<br />

14. Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, et al. 2012<br />

Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical<br />

practice guideline <strong>for</strong> the diagnosis and treatment<br />

of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis.<br />

2012;54(12):e132-173.<br />

15. Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al.<br />

Diabetic foot disorders. A clinical practice guideline<br />

(2006 revision). J Foot Ankle Surg. 2006;45(5<br />

Suppl):S1-66.<br />

16. Steed DL, Attinger C, Colaizzi T, et al. Guidelines<br />

<strong>for</strong> the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Wound Repair<br />

Regen. 2006;14(6):680-692.<br />

17. Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC; International<br />

Working Group on Diabetic Foot Editorial Board.<br />

Practical guidelines on the management and prevention<br />

of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabetes Metab<br />

Res Rev. 2012;28 Suppl 1:225-231.<br />

<strong>Expert</strong> <strong>Recommendations</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Optimizing</strong> <strong>Outcomes</strong> Utilizing Apligraf ® <strong>for</strong> Diabetic Foot Ulcers 21

18. Margolis DJ, et al. Risk factors <strong>for</strong> delayed healing<br />

of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: a pooled analysis.<br />

Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1531-1535.<br />

19. Ali R, Qureshi A, Yagoob MY, Shakil M. Total contact<br />

cast <strong>for</strong> neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. J Coll<br />

Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18(11):695-698.<br />

20. Hanft JR, Surprenant MS. Is total contact casting<br />

the gold standard <strong>for</strong> the treatment of diabetic foot<br />

ulcerations Abstract presented at American College<br />

of Foot and Ankle Surgeons Joint Annual Meeting<br />

and Scientific Seminar; February 9, 2000; Miami, FL.<br />

21. Faglia E, Caravaggi C, Clerici G, et al. Effectiveness of<br />

removable walker cast versus nonremovable fiberglass<br />

off-bearing cast in the healing of diabetic plantar foot<br />

ulcer: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care.<br />

2010;33(7):1419-1423.<br />

22. Armstrong DG, Short B, Espensen EH, Abu-Rumman<br />

PL, Nixon BP, Boulton AJ. Technique <strong>for</strong> fabrication<br />

of an “instant total-contact cast” <strong>for</strong> treatment<br />

of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. J Am Podiatr Med<br />

Assoc. 2002;92(7):405-408.<br />

23. van Deursen R. Footwear <strong>for</strong> the neuropathic patient:<br />

offloading and stability. Diabetes Metab Res Rev.<br />

2008;24(suppl 1):S96-100.<br />

24. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the<br />

development and progression of long-term complications<br />

in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the<br />

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research<br />

Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977-986.<br />

25. Steed DL, Donohoe D, Webster MW, Lindsley L.<br />

Effect of extensive debridement and treatment on the<br />

healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetic Ulcer Study<br />

Group. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183(1):61-64.<br />

26. Saap LJ, Falanga V. Debridement per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

index and its correlation with complete closure<br />

of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen.<br />