Spring 2007 - College of Education - Michigan State University

Spring 2007 - College of Education - Michigan State University

Spring 2007 - College of Education - Michigan State University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

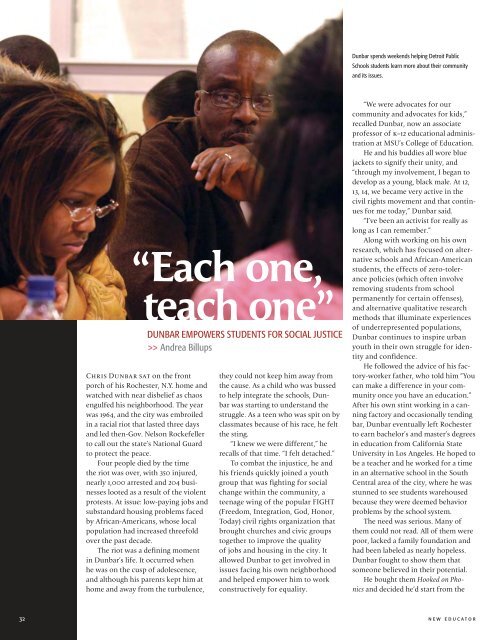

Dunbar spends weekends helping Detroit Public<br />

Schools students learn more about their community<br />

and its issues.<br />

“Each one,<br />

teach one”<br />

DUNBAR EMPOWERS STUDENTS FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE<br />

>> Andrea Billups<br />

Chris Dunbar sat on the front<br />

porch <strong>of</strong> his Rochester, N.Y. home and<br />

watched with near disbelief as chaos<br />

engulfed his neighborhood. The year<br />

was 1964, and the city was embroiled<br />

in a racial riot that lasted three days<br />

and led then-Gov. Nelson Rockefeller<br />

to call out the state’s National Guard<br />

to protect the peace.<br />

Four people died by the time<br />

the riot was over, with 350 injured,<br />

nearly 1,000 arrested and 204 businesses<br />

looted as a result <strong>of</strong> the violent<br />

protests. At issue: low-paying jobs and<br />

substandard housing problems faced<br />

by African-Americans, whose local<br />

population had increased threefold<br />

over the past decade.<br />

The riot was a defining moment<br />

in Dunbar’s life. It occurred when<br />

he was on the cusp <strong>of</strong> adolescence,<br />

and although his parents kept him at<br />

home and away from the turbulence,<br />

they could not keep him away from<br />

the cause. As a child who was bussed<br />

to help integrate the schools, Dunbar<br />

was starting to understand the<br />

struggle. As a teen who was spit on by<br />

classmates because <strong>of</strong> his race, he felt<br />

the sting.<br />

“I knew we were different,” he<br />

recalls <strong>of</strong> that time. “I felt detached.”<br />

To combat the injustice, he and<br />

his friends quickly joined a youth<br />

group that was fighting for social<br />

change within the community, a<br />

teenage wing <strong>of</strong> the popular FIGHT<br />

(Freedom, Integration, God, Honor,<br />

Today) civil rights organization that<br />

brought churches and civic groups<br />

together to improve the quality<br />

<strong>of</strong> jobs and housing in the city. It<br />

allowed Dunbar to get involved in<br />

issues facing his own neighborhood<br />

and helped empower him to work<br />

constructively for equality.<br />

“We were advocates for our<br />

community and advocates for kids,”<br />

recalled Dunbar, now an associate<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> k–12 educational administration<br />

at MSU’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong>.<br />

He and his buddies all wore blue<br />

jackets to signify their unity, and<br />

“through my involvement, I began to<br />

develop as a young, black male. At 12,<br />

13, 14, we became very active in the<br />

civil rights movement and that continues<br />

for me today,” Dunbar said.<br />

“I’ve been an activist for really as<br />

long as I can remember.”<br />

Along with working on his own<br />

research, which has focused on alternative<br />

schools and African-American<br />

students, the effects <strong>of</strong> zero-tolerance<br />

policies (which <strong>of</strong>ten involve<br />

removing students from school<br />

permanently for certain <strong>of</strong>fenses),<br />

and alternative qualitative research<br />

methods that illuminate experiences<br />

<strong>of</strong> underrepresented populations,<br />

Dunbar continues to inspire urban<br />

youth in their own struggle for identity<br />

and confidence.<br />

He followed the advice <strong>of</strong> his factory-worker<br />

father, who told him “You<br />

can make a difference in your community<br />

once you have an education.”<br />

After his own stint working in a canning<br />

factory and occasionally tending<br />

bar, Dunbar eventually left Rochester<br />

to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees<br />

in education from California <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> in Los Angeles. He hoped to<br />

be a teacher and he worked for a time<br />

in an alternative school in the South<br />

Central area <strong>of</strong> the city, where he was<br />

stunned to see students warehoused<br />

because they were deemed behavior<br />

problems by the school system.<br />

The need was serious. Many <strong>of</strong><br />

them could not read. All <strong>of</strong> them were<br />

poor, lacked a family foundation and<br />

had been labeled as nearly hopeless.<br />

Dunbar fought to show them that<br />

someone believed in their potential.<br />

He bought them Hooked on Phonics<br />

and decided he’d start from the<br />

32<br />

new educator