pdf (87kb) - Africa Health

pdf (87kb) - Africa Health

pdf (87kb) - Africa Health

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS<br />

Transient loss of<br />

consciousness (excluding<br />

epilepsy)<br />

Sanjiv Petkar<br />

Adam Fitzpatrick<br />

Paul Cooper<br />

Abstract<br />

Patients are often referred suffering from a ‘Collapse cause’. In some<br />

of these patients, the ‘collapse’ would have been caused by or associated<br />

with loss of consciousness. The three main and common causes<br />

of transient loss of consciousness (T-LOC) are syncope, epilepsy and<br />

non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). The term T-LOC excludes patients<br />

in whom the loss of consciousness is induced by trauma or is prolonged<br />

(e.g. metabolic disorders like hypoglycaemia and hyponatremia). Among<br />

the causes of T-LOC, syncope, which is a symptom with many underlying<br />

causes, is much more prevalent than either epilepsy or NEAD. This article<br />

will deal predominantly with syncope and how it can be differentiated<br />

from epilepsy and NEAD.<br />

Keywords blackouts; collapse; epilepsy; implantable loop recorders;<br />

psychogenic blackouts; syncope; transient loss of consciousness<br />

loss of consciousness or in some instances, even coma (from the<br />

Greek ‘koma’, meaning deep sleep). T-LOC also excludes those<br />

in whom the loss of consciousness occurs as a result of trauma<br />

(e.g. concussion, intracerebral bleed). It is worth mentioning that<br />

transient ischaemic attacks are rarely associated with T- LOC,<br />

being typically characterized by neurological deficit without loss<br />

of consciousness, as opposed to syncope in which patients experience<br />

loss of consciousness without a neurological deficit.<br />

Definitions<br />

The European Society of Cardiology defines syncope as ‘a<br />

transient, self-limited loss of consciousness, usually leading to<br />

collapse. The onset of syncope is relatively rapid, and the subsequent<br />

recovery is spontaneous, complete, and usually prompt.<br />

The underlying mechanism is transient global cerebral hypoperfusion’.<br />

2 Syncope is a symptom, not a diagnosis, the many causes<br />

of which are listed in Table 1.<br />

An ‘epileptic seizure’ is defined by the International League<br />

Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau of Epilepsy<br />

(IBE) as a ‘transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to<br />

an abnormal excessive or asynchronous neuronal activity in the<br />

brain’. 3 A diagnosis of ‘epilepsy’ is reserved for those patients<br />

who have recurrent ‘epileptic seizures’.<br />

NEAD are ‘unintentional paroxysms of altered sensation,<br />

movement, perception, or emotion that clinically resemble<br />

epileptic seizures but are not accompanied by epileptiform neurophysiological<br />

changes’. 4<br />

Introduction<br />

It is common to come across patients referred having had a ‘Collapse<br />

cause’. ‘Collapse’, which has many causes, is a sudden<br />

and often unannounced loss of postural tone, often, but not necessarily<br />

accompanied by loss of consciousness. In those patients<br />

in whom ‘Collapse’ is caused or associated with loss of consciousness,<br />

the duration of this ‘mental state that involves complete<br />

or near-complete lack of responsiveness to people and other<br />

environmental stimuli’ can vary. 1 Transient loss of consciousness<br />

(T-LOC) or blackout is commonly caused either by syncope,<br />

epilepsy or a non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). Intoxication,<br />

metabolic abnormalities e.g., hypoglycaemia or hyponatremia,<br />

central nervous system diseases, acute neurologic injuries such<br />

as stroke, and hypoxia are often associated with more prolonged<br />

Sanjiv Petkar MRCP is a Clinical Research Fellow and Honorary Associate<br />

Specialist at the Manchester Heart Centre, Manchester Royal Infirmary,<br />

UK. Competing interests: Dr Petkar’s present position is funded by a<br />

grant to the University from Medtronic Inc.<br />

Adam Fitzpatrick BSc FRCP FACC is Consultant Cardiologist at the<br />

Manchester Heart Centre, Manchester Royal Infirmary, UK. Competing<br />

interests: none.<br />

Paul Cooper FRCP is Consultant Neurologist at the Greater Manchester<br />

Centre for Neurosciences, Hope Hospital, Salford, UK. Competing<br />

interests: none.<br />

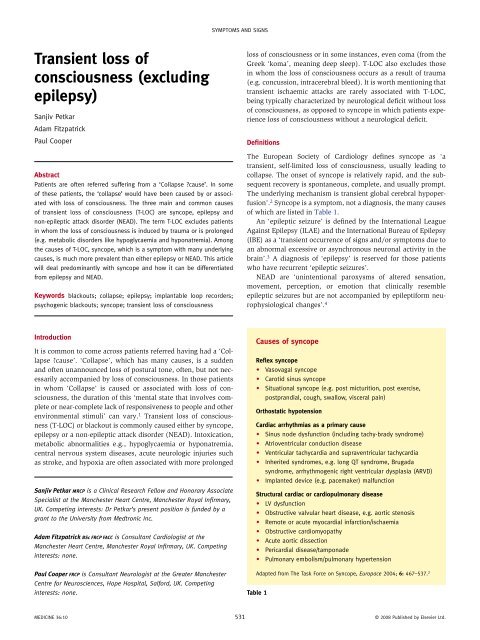

Causes of syncope<br />

Reflex syncope<br />

• Vasovagal syncope<br />

• Carotid sinus syncope<br />

• Situational syncope (e.g. post micturition, post exercise,<br />

postprandial, cough, swallow, visceral pain)<br />

Orthostatic hypotension<br />

Cardiac arrhythmias as a primary cause<br />

• Sinus node dysfunction (including tachy-brady syndrome)<br />

• Atrioventricular conduction disease<br />

• Ventricular tachycardia and supraventricular tachycardia<br />

• Inherited syndromes, e.g. long QT syndrome, Brugada<br />

syndrome, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD)<br />

• Implanted device (e.g. pacemaker) malfunction<br />

Structural cardiac or cardiopulmonary disease<br />

• LV dysfunction<br />

• Obstructive valvular heart disease, e.g. aortic stenosis<br />

• Remote or acute myocardial infarction/ischaemia<br />

• Obstructive cardiomyopathy<br />

• Acute aortic dissection<br />

• Pericardial disease/tamponade<br />

• Pulmonary embolism/pulmonary hypertension<br />

Adapted from The Task Force on Syncope, Europace 2004; 6: 467–537. 2<br />

Table 1<br />

MEDICINE 36:10 531 © 2008 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS<br />

Epidemiology<br />

Syncope is a common problem with an estimated prevalence of<br />

42% during the life of a person living 70 years. 2 It shows a bimodal<br />

age distribution with a high incidence in young populations<br />

(median age 15 years), with a second peak in older patients ≥75<br />

years of age. Females are more prone to syncope than men. The<br />

prognosis of syncope depends on its cause. Reflex syncope, the<br />

commonest cause of syncope, has a mortality which is near to<br />

0%, 2 while cardiac syncope is an independent predictor of mortality<br />

and sudden death. In patients with advanced heart failure<br />

and a mean ejection fraction of 20%, the one-year mortality can<br />

reach as high as 45%. 2<br />

Pathophysiology<br />

A sudden cessation of cerebral blood flow for 6 to 8 seconds, a<br />

decrease in systolic blood pressure to 60 mmHg, or a 20% drop in<br />

cerebral oxygen delivery, has been shown to be enough to cause<br />

complete loss of consciousness. 2 A number of control mechanisms<br />

are critical in maintaining adequate cerebral oxygen delivery:<br />

• cerebral autoregulation<br />

• local metabolic and chemical control<br />

• arterial baroreceptor induced adjustments of heart rate, cardiac<br />

contractility, and systemic vascular resistance<br />

• intravascular volume regulation by salt and water intake, hormones<br />

and the renal system.<br />

Whatever the mechanism, a transient global cerebral hypoperfusion<br />

to critical values induces a syncopal episode. As<br />

opposed to healthy younger individuals, 2 ageing alone has<br />

been shown to be associated with a decrease in cerebral blood<br />

flow, 5 and therefore, the risk of failure of these compensatory<br />

mechanisms is likely to be greatest in the elderly or critically<br />

ill patients.<br />

On standing, 0.5 to 1.0 litre of blood shifts to the venous<br />

capacitance vessels below the diaphragm. On continued standing,<br />

a further 10 to 15% of the plasma volume is lost due to<br />

the higher transmural capillary pressure in the dependent parts<br />

of the body. 6 Both of these mechanisms result in a decrease in<br />

stroke volume and cardiac output. A fall in the mean arterial<br />

pressure is prevented by compensatory mechanisms, including<br />

vasoconstriction of the resistance and capacitance vessels. These<br />

adjustments are mediated entirely by the autonomic nervous system<br />

through, mainly, baroreceptors in the aortic arch and carotid<br />

sinuses and mechanoreceptors in the heart and the lungs. Failure<br />

of the above compensatory mechanisms is thought to result<br />

in syncope. 2 The initial trigger of reflex syncope is unknown,<br />

although the relay in the brainstem and the afferent arc are well<br />

understood. 7<br />

Evaluation<br />

The initial evaluation of a patient with syncope consists of a<br />

careful history, physical examination, including orthostatic<br />

blood pressure measurements, and a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram<br />

(ECG). 8 Studies have shown that based on this initial<br />

evaluation, a diagnosis of syncope could be made with certainty<br />

in between 50–63% of patients, 9,10 thus avoiding the need for<br />

additional testing.<br />

History alone may be sufficient in arriving at a diagnosis of the<br />

cause of T-LOC. 11,12 Table 2 lists some of the important clinical<br />

features of the different types of syncope. A good history also<br />

helps to differentiate ‘convulsive syncope’, from epilepsy. If the<br />

clinical features of ‘convulsive syncope’ (cerebral hypoperfusion<br />

associated with abrupt T-LOC resulting in myoclonic jerks) are<br />

not appreciated, it can lead to a misdiagnosis of epilepsy. 8 However,<br />

the yield of history-taking may be limited in the presence of<br />

cognitive impairment in the elderly, a feature encountered in 5%<br />

of 65-year-olds and 20% of 80-year-olds. 13<br />

Physical examination: care should be taken to assess the rate<br />

and regularity of the pulse, lying and standing blood pressure,<br />

examination for scars of previous cardiac operations, and auscultation<br />

for heart sounds and any murmurs. Abnormalities in the<br />

physical examination can point towards a diagnosis of syncope<br />

due to orthostatic hypotension, an arrhythmia or structural heart<br />

disease. On the other hand, in reflex syncope, the examination is<br />

likely to be normal.<br />

ECG<br />

The diagnostic yield of electrocardiography and rhythm recordings<br />

is low, ranging from 1 to 11%. 2,14 However, a 12-lead ECG<br />

is a cheap and reliable test and must be done for every patient<br />

who presents with a T-LOC. A normal 12-lead ECG is a good<br />

prognostic indicator. Abnormalities on the ECG which suggest<br />

or confirm the cause of T-LOC or confer higher risk, are given in<br />

Tables 3 and 4.<br />

Other investigations<br />

Basic laboratory tests have only limited value in the investigation<br />

of patients with syncope and are indicated only if a syncope-like<br />

condition with a metabolic cause is suspected. 8<br />

When the mechanism of syncope is not evident from the<br />

above evaluation, further tests e.g. echocardiography, stress<br />

Clinical features suggestive of specific causes of<br />

syncope<br />

Reflex syncope<br />

• Absence of cardiac disease<br />

• Long history of syncope<br />

• T-LOC occurring after unpleasant sight, sound, smell or pain,<br />

after prolonged standing or in crowded, hot places<br />

• Nausea, vomiting associated with syncope<br />

• T-LOC during or in the absorptive state after a meal<br />

• Head rotation or pressure on the carotid sinus precipitating<br />

T-LOC<br />

• T-LOC occurring after exertion<br />

Cardiac syncope<br />

• Presence of severe structural heart disease<br />

• T-LOC during exertion or supine<br />

• T-LOC preceded by palpitation or accompanied by chest pain<br />

• Family history of sudden cardiac death ≤40years of age<br />

Adapted from The Task Force on Syncope, Europace 2004; 6: 467–537. 2<br />

Table 2<br />

MEDICINE 36:10 532 © 2008 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS<br />

ECG abnormalities suggesting an arrhythmic cause<br />

of syncope<br />

• Bifascicular block (left bundle branch block or right bundle<br />

branch block combined with left anterior or left posterior<br />

fascicular block)<br />

• Other intraventricular conduction disturbances (QRS<br />

duration ≥0.12 secs)<br />

• Mobitz I second-degree atrioventricular block<br />

• Asymptomatic sinus bradycardia (

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS<br />

Management<br />

Only about two thirds of patients with a syncopal episode see<br />

a doctor or visit hospital for evaluation. 20 In those who do seek<br />

medical attention and when the initial evaluation leads to a certain<br />

diagnosis, no further evaluation is needed and treatment, if<br />

necessary, can be started. 8<br />

Treatment of patients with syncope depends on its cause. In<br />

all patients with reflex syncope, 8 treatment consists of:<br />

• education and reassurance<br />

• lifestyle measures e.g., volume expansion by salt supplements,<br />

head–up tilt sleeping (>10°), isometric leg and arm<br />

counter pressure manoeuvres to abort an impending attack.<br />

In selected cases, the following may be useful:<br />

• tilt training<br />

• drug therapy e.g. midodrine 21<br />

• permanent pacemaker implantation. 22<br />

Treatment in patients with cardiac syncope, again, depends on<br />

the cause and may include:<br />

• drug treatment<br />

• permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator<br />

implantation<br />

• catheter ablation of arrhythmias<br />

• coronary revascularization, e.g. angioplasty or coronary artery<br />

bypass grafting<br />

• cardiac surgery, e.g. valve replacement.<br />

Conclusion<br />

When managing patients with Collapsecause, in whom one<br />

encounters a history of T-LOC, it is important to remember that<br />

simple tools (a good history, a thorough physical examination<br />

and a 12-lead ECG) can help to differentiate amongst the three<br />

commonest causes of T-LOC i.e., syncope, epilepsy or NEAD. It<br />

is, therefore, of vital importance that one is aware of the clinical<br />

features and presentation of these three conditions. ◆<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1 http://www.stedmans.com/section.cfm/45 (accessed 15 July 2008).<br />

2 The Task Force on Syncope, European Society of Cardiology.<br />

Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncopeupdate<br />

2004. Europace 2004; 6: 467–537.<br />

3 Fisher RS, Boas W, Blume W, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy:<br />

definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy<br />

(ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia<br />

2005; 46: 470.<br />

4 Gumnit RJ, Gates JR. Psychogenic seizures. Epilepsia 1986; 27<br />

(suppl 2): S124–29.<br />

5 Scheinberg P, Blackburn I, Rich M, et al. Effects of aging on cerebral<br />

circulation and metabolism. Arch Neurol Psychiatr 1953; 70: 77–85.<br />

6 Smit AAJ, Halliwill JR, Low PA, et al. Topical review.<br />

Pathophysiological basis of orthostatic hypotension in autonomic<br />

failure. J Physiol 1999; 519: 1–10.<br />

7 Thomson HL, Wright K, Frenneaux M. Baroreflex sensitivity in<br />

patients with vasovagal syncope. Circulation 1997; 95: 395–400.<br />

8 The Task Force on Syncope, European Society of Cardiology.<br />

Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope –<br />

update 2004. Executive Summary. Eur Heart J 2004; 25: 2054–72.<br />

9 Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes 3rd NA, Wang P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN.<br />

Diagnosing syncope. Part I: Value of history, physical examination,<br />

and electrocardiography. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126: 989–96.<br />

10 van Dijk N, Boer KR, Colman N, et al. High diagnostic yield and<br />

accuracy of history, physical examination, and ECG in patients with<br />

transient loss of consciousness in FAST: the Fainting Assessment<br />

Study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2008; 19: 48–55.<br />

11 Sheldon R, Rose S, Ritchie D, et al. Historical criteria that distinguish<br />

syncope from seizures. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40: 142–48.<br />

12 Sheldon R, Rose S, Connolly S, Ritchie D, Koshman ML, Frenneaux M.<br />

Diagnostic criteria for vasovagal syncope based on a quantitative<br />

history. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 344–50.<br />

13 Shaw FE, Kenny RA. Overlap between syncope and falls in the<br />

elderly. Postgrad Med J 1997; 73: 635–39.<br />

14 Grubb NR, Boon N. Dizzy spells and syncope: evaluation and<br />

management. Medicine 2006; 34: 245–50.<br />

15 Sander JW, Hart YM, Johnson AL, Shrovon SD. National General<br />

Practice Study of Epilepsy: newly diagnosed epileptic seizures in a<br />

general population. Lancet 1990; 336: 1267–71.<br />

16 Stokes T, Shaw EJ, Juarez-Garcia A, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Baker R.<br />

Clinical guidelines and evidence review for the epilepsies: diagnosis<br />

and management in adults and children in primary and secondary<br />

care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2004.<br />

17 Petkar S, Cooper P, Fitzpatrick A. How to avoid a diagnosis in<br />

patients presenting with transient loss of consciousness. Postgrad<br />

Med J 2006; 82: 630–41.<br />

18 All Party Parliamentary Group on Epilepsy. Wasted money, wasted<br />

lives. The human and economic cost of epilepsy in England. July<br />

2007. Joint Epilepsy Council of the UK and Ireland.<br />

19 Mellers JDC. The approach to patients with ‘non-epileptic seizures’.<br />

Postgrad Med J 2005; 81: 498–504.<br />

20 Colman N, Nahm K, Ganzeboom KS, et al. Epidemiology of reflex<br />

syncope. Clin Auton Res 2004; 14(Suppl1): 9–17.<br />

21 Perez-Lugones A, Schweikert R, Pavia S, et al. Usefulness of midodrine<br />

in patients with severly symptomatic neurocardiogenic syncope: a<br />

randomized control study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001; 12: 935–38.<br />

22 Brignole M, Sutton R, Menozzi C, et al. for the International<br />

Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology 2 (ISSUE 2) Group. Early<br />

application of an implantable loop recorder allows effective specific<br />

therapy in patients with recurrent suspected neurally mediated<br />

syncope. Eur Heart J 2006; 26: 1085–92.<br />

MEDICINE 36:10 534 © 2008 Published by Elsevier Ltd.