Grades 5 and 6 Writing Units of Study.pdf

Grades 5 and 6 Writing Units of Study.pdf

Grades 5 and 6 Writing Units of Study.pdf

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

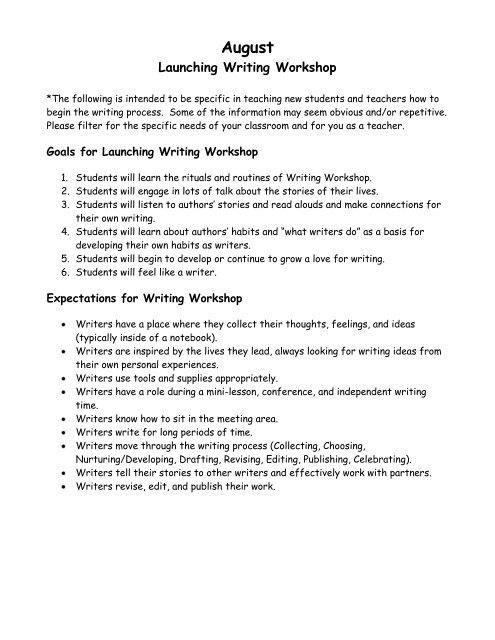

August<br />

Launching <strong>Writing</strong> Workshop<br />

*The following is intended to be specific in teaching new students <strong>and</strong> teachers how to<br />

begin the writing process. Some <strong>of</strong> the information may seem obvious <strong>and</strong>/or repetitive.<br />

Please filter for the specific needs <strong>of</strong> your classroom <strong>and</strong> for you as a teacher.<br />

Goals for Launching <strong>Writing</strong> Workshop<br />

1. Students will learn the rituals <strong>and</strong> routines <strong>of</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Workshop.<br />

2. Students will engage in lots <strong>of</strong> talk about the stories <strong>of</strong> their lives.<br />

3. Students will listen to authors‘ stories <strong>and</strong> read alouds <strong>and</strong> make connections for<br />

their own writing.<br />

4. Students will learn about authors‘ habits <strong>and</strong> ―what writers do‖ as a basis for<br />

developing their own habits as writers.<br />

5. Students will begin to develop or continue to grow a love for writing.<br />

6. Students will feel like a writer.<br />

Expectations for <strong>Writing</strong> Workshop<br />

Writers have a place where they collect their thoughts, feelings, <strong>and</strong> ideas<br />

(typically inside <strong>of</strong> a notebook).<br />

Writers are inspired by the lives they lead, always looking for writing ideas from<br />

their own personal experiences.<br />

Writers use tools <strong>and</strong> supplies appropriately.<br />

Writers have a role during a mini-lesson, conference, <strong>and</strong> independent writing<br />

time.<br />

Writers know how to sit in the meeting area.<br />

Writers write for long periods <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

Writers move through the writing process (Collecting, Choosing,<br />

Nurturing/Developing, Drafting, Revising, Editing, Publishing, Celebrating).<br />

Writers tell their stories to other writers <strong>and</strong> effectively work with partners.<br />

Writers revise, edit, <strong>and</strong> publish their work.

Preparing for <strong>Writing</strong> Workshop<br />

Is there a meeting area in my classroom where I will teach each day‘s mini-lesson<br />

from <strong>and</strong> where I will gather the students at the end <strong>of</strong> the Workshop for the<br />

teaching share?<br />

Is the meeting area large enough so that all my students can fit on the floor <strong>and</strong><br />

be close to where I am sitting?<br />

Can I use the overhead projector in this area? (<strong>of</strong>ten the teacher will use<br />

overheads during the teaching part <strong>of</strong> the mini-lesson – it‘s good to have your<br />

meeting area in a place where you can use the overhead projector)<br />

Do I have all the supplies for teaching a mini-lesson in the meeting area (chart<br />

paper, easel, chart markers, tape, scissors, Post-it notes, blank overhead<br />

transparencies, transparency markers, some books that support the Unit <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Study</strong> you are in, <strong>and</strong> anything else you find necessary)?<br />

Will students take their Writer‘s Notebook home each day or will they be left at<br />

school in a special place? (Sometimes, if students keep their Notebooks in their<br />

desks, they get torn up <strong>and</strong>/or lost. It <strong>of</strong>ten helps to have a tub in the room in<br />

which Notebooks can be kept.)<br />

Where will my students keep their ongoing drafts? (students <strong>of</strong>ten have a writing<br />

folder that is kept in a tub somewhere in the room that contains ongoing work<br />

outside <strong>of</strong> the Writer‘s Notebook)<br />

Will I have wall space in my room designated for an organizer that has kids show<br />

where they are in the writing process? (It has been helpful for teachers to list<br />

out the steps in the writing process where kids can move a clip to the step they<br />

are in at a certain time.)<br />

How will I keep/organize my conferring notes?<br />

What are some things I will do to foster independence? (students sharpen pencils<br />

without asking or keep a tub <strong>of</strong> sharpened pencils in the room / have a writing<br />

center where students can access paper choices, highlighters, scissors, Scotch<br />

tape, correction tape, colored pencils, pens, pencils, dictionaries, thesauruses,<br />

check-lists, etc. / have a system for signing out for the bathroom<br />

Where in my room will I keep charts up that need to stay up all year? (charts like<br />

– ―Where Writers Get Ideas‖ ―How to Collect in you Writer‘s Notebook‖<br />

―Nurturing Strategies‖ ―Revision Strategies‖ & ―Editing Strategies‖ might be left<br />

up all year to encourage independence – Charts specific to a Unit <strong>of</strong> <strong>Study</strong> usually<br />

will come down after the Unit <strong>of</strong> <strong>Study</strong> is over, but these other, more general<br />

charts might stay up all year)<br />

Will I periodically assess each student‘s Writer‘s Notebook? (some teachers<br />

create rubrics that assess the Notebook <strong>and</strong> they share these with students in<br />

the beginning <strong>of</strong> the year)<br />

What are my expectations for the Writer‘s Notebook?

What can I write before school starts that will show my students that I am a<br />

writer too (notebook entries, short stories, poetry)?<br />

Will I start a Writer‘s Notebo<br />

Will I have a catchy phrase or any other way to signal to the kids that it‘s time to<br />

gather in the meeting area for the mini-lesson? (some classrooms have a bell the<br />

teacher rings to let the students know it‘s time for WW – I was in one classroom<br />

where the teacher had a wind chime in the middle <strong>of</strong> the room that she touched,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the kids would just drop everything <strong>and</strong> go to the meeting area – this<br />

definitely isn‘t necessary, but it deserves some thought)<br />

What the Physical Room Looks Like – A CHECKLIST:<br />

1. Is there a meeting area where my students can gather for mini-lessons <strong>and</strong><br />

shares?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

2. Is there a well organized, well stocked writing center with writing tools ready <strong>and</strong><br />

available at the onset <strong>of</strong> every writing workshop?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

3. Are the writing folders in a place where students are able to reach them <strong>and</strong><br />

include spaces for finished <strong>and</strong> unfinished writing?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

4. Are there examples <strong>of</strong> different genres hanging around the room in places that<br />

are clear <strong>and</strong> easy to see (a poem, a song, a recipe, a list, different cards, letters,<br />

a non-fiction article, etc.)?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

5. Are there words that students can copy in meaningful ways (color words, number<br />

words, classmate names, your name, word wall with high frequency words, etc.)?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

6. Are there places to display examples <strong>of</strong> student‘s published <strong>and</strong> unpublished work,<br />

or works in progress?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No

7. Are there places for examples <strong>of</strong> your modeled writing, your works in progress?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

8. Is there an editing checklist the students can refer to all year long?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

9. Is there a large calendar with writing celebration dates/publication deadlines<br />

clearly written in?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

10. Is there a library with books students can read <strong>and</strong> refer to for writing, including<br />

a place to put books that are the genre you are currently studying?<br />

_______ Yes _______ No<br />

Teresa Caccavale & Isoke Nia<br />

Teachers College Reading <strong>and</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Project<br />

The first unit <strong>of</strong> study should focus on helping students underst<strong>and</strong> the structures <strong>of</strong> writing<br />

workshop, the basic principles <strong>of</strong> writing process, <strong>and</strong> revision strategies that you feel they<br />

could use, based upon your early assessments. Many teachers start with personal narrative<br />

because they find that writing form experience is easiest for students. –Janet Angelillo<br />

Overview <strong>of</strong> Unit<br />

First, introduce Writer‘s Notebooks by sharing your Notebook with students. Create a<br />

chart with the students <strong>of</strong> ways to Collect in the Notebooks (lists, webs, artifacts,<br />

photographs, sketches, etc.) <strong>and</strong> a chart <strong>of</strong> what to Collect in the Notebooks (memories<br />

you don‘t want to forget, special words/phrases, story ideas, fierce wonderings, etc.).<br />

Keep adding to these charts as the students discover new ways to Collect <strong>and</strong> new ideas<br />

for Collecting.<br />

Have kids Collecting in their Notebooks for several days, building stamina as writers <strong>and</strong><br />

developing a sense <strong>of</strong> ―I am a writer.‖<br />

Teach the steps in the writing process <strong>and</strong> the procedures <strong>of</strong> writing workshop. Assign<br />

students the task <strong>of</strong> writing a personal narrative so that they have an authentic<br />

assignment. Teach revision strategies within the context <strong>of</strong> writing those narratives,<br />

choosing strategies that are simple so that students can be successful right from the<br />

start.

<strong>Writing</strong> Notebooks<br />

Start by giving students time to personalize their notebooks. This is really<br />

important. Some teachers have a launching party where they give the notebooks<br />

to the students <strong>and</strong> give them time to personalize with wallpaper, stickers,<br />

construction paper, markers, etc.<br />

As students start collecting inside their notebook, teach them to date each<br />

entry.<br />

It may be good to have 2 starting points inside the notebook: 1 from the front<br />

where students are collecting their thoughts, ideas, <strong>and</strong> stories during<br />

independent writing time <strong>and</strong> another starting point from the back <strong>of</strong> the<br />

notebook. Students can flip the notebook to the back <strong>and</strong> start keeping notes<br />

from mini-lessons. They can also cut down h<strong>and</strong>-outs <strong>and</strong> glue them in this section.<br />

This way they can quickly reference something they learned during a mini-lesson.<br />

Maybe have students put a Post-it in their notebook when they are starting a new<br />

Unit <strong>of</strong> <strong>Study</strong>, so they can quickly turn in their notebooks.<br />

We want to teach strategies for finding things to write about, not give prompts.<br />

Teaching strategies rather than assigning prompts will allow our students to<br />

become more independent as they use the strategy over <strong>and</strong> over.<br />

You want to start a chart <strong>of</strong> all the ways you can collect inside a <strong>Writing</strong><br />

Notebook. You will want to demonstrate each strategy inside your own notebook<br />

or on chart paper so that the students see you being a writer.<br />

Share <strong>Writing</strong> Notebook rubrics with students right from the start. Teachers<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten assess Notebooks for volume, variety, <strong>and</strong> neatness <strong>of</strong> entries. It is good to<br />

share these expectations with students right from the start.<br />

It is too overwhelming to collect all <strong>of</strong> the notebooks at one time for assessment,<br />

so you may want to consider varied collection days. You could have 5 students<br />

leave their notebooks on their desks at the end <strong>of</strong> the day on Monday, 5 on<br />

Tuesday, 5 on Wednesday, etc. Then, you are assessing their notebooks once a<br />

week <strong>and</strong> only doing 5 a day. This will make it more manageable.<br />

You may have kids do Daily Pages to increase their writing stamina <strong>and</strong> fluency.<br />

Some teachers have students write at least 1 full page (no skipping lines, no<br />

starting way down on the page, <strong>and</strong> no writing HUGE so that only a few words fit<br />

on the page) for homework each night or first thing in the morning. Often,<br />

teachers will have students who are not shopping for books in the morning writing<br />

their Daily Page. It can be writing about anything. It can be mundane <strong>and</strong> simple,<br />

but at least they are writing. They can label the page with D.P. for Daily Page, so<br />

you know when you are assessing.

WHAT‘S INSIDE A NOTEBOOK WHAT‘S OUTSIDE A NOTEBOOK<br />

Daily entries<br />

Collecting around <strong>and</strong><br />

nurturing a topic<br />

Revision strategies – trying<br />

out some possibilities<br />

Editing, Grammar notes<br />

Other notes <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>-outs<br />

from mini-lessons<br />

Drafts – the whole piece is<br />

written outside the notebook<br />

Revisions the author wants to use<br />

Editing the actual piece<br />

The final copy<br />

Notebook Expectations<br />

Students are expected to…<br />

Write daily in their notebooks at school<br />

<strong>and</strong> at home three times a week (minimum).<br />

―find‖ topics for their notebook writing<br />

from their life, from reading, <strong>and</strong> from<br />

natural curiosity. Students are expected<br />

to make decisions about their writing<br />

topics on a daily basis.<br />

Try strategies from the mini-lesson before<br />

continuing with their own work for the day.<br />

Respect the integrity <strong>of</strong> the notebook by<br />

taking care <strong>of</strong> it <strong>and</strong> having it in class<br />

every day. Students will respect other<br />

notebooks by only reading entries they are<br />

invited to read by the author.<br />

Students can depend on the<br />

teacher to…<br />

Provide time each day for students to<br />

write during writing workshop.<br />

Teach writing strategies as ways to<br />

discover writing topics. Teachers will also<br />

confer with students to help nudge their<br />

thinking <strong>and</strong> writing when students get<br />

stuck.<br />

Teach a mini-lesson each day to teach<br />

students how to be better writers.<br />

Not write inside <strong>of</strong> the students‘<br />

notebooks.

Collecting Entries<br />

Write about your name – what makes it special, how was it picked, what do you<br />

like about it, what do you not like about it, just think about your name <strong>and</strong> write.<br />

You can use Kevin Henkes‘ book, Chrysanthemum, to illustrate the<br />

power/importance <strong>of</strong> a name <strong>and</strong> how <strong>of</strong>ten times there is a story behind our<br />

name. So that this doesn‘t just become a prompt, you can teach kids that anytime<br />

they are struggling to find something to write about, they can think <strong>of</strong> a person‘s<br />

name, put it at the top <strong>of</strong> a page, <strong>and</strong> write about the name. Names are special <strong>and</strong><br />

usually have a story behind them.<br />

Heart Map: Draw a large heart in your notebook <strong>and</strong> then mark <strong>of</strong>f sections like a<br />

quilt. Write special people, places, <strong>and</strong> things in the sections.<br />

School Walk – jot down memories from places throughout the school<br />

Draw a special place <strong>and</strong> put an X everywhere there is a memory <strong>of</strong> a story (jot<br />

down a few words to remind you <strong>of</strong> the story).<br />

<strong>Writing</strong> from a list – Best life events…jot down the 10 best things that ever<br />

happened to you. Jot down the 7 worst things that ever happened to you. Choose 1<br />

to put at the top <strong>of</strong> a clean page <strong>and</strong> write the story <strong>of</strong> that time. The important<br />

thing about making these lists is that it leads into writing many stories. We don‘t<br />

want kids just to make lists. So, you may give them 5 or 10 minutes to make a list<br />

<strong>and</strong> then have them move to choosing 1 thing from the list to write the story <strong>of</strong><br />

that 1 time. Lists are good, but we want them to lead to long writing.<br />

Other lists –<br />

*make a list <strong>of</strong> emotions (sad, happy, mad, disappointed, <strong>and</strong> jealous). Choose 1,<br />

put it at the top <strong>of</strong> clean page <strong>and</strong> list all <strong>of</strong> the times you felt that emotion.<br />

Choose 1 time to write the story in your notebook.<br />

*make a list <strong>of</strong> things you are an expert <strong>of</strong>, choose 1, put it at the top <strong>of</strong> a clean<br />

page <strong>and</strong> list all the times you‘ve done that thing. Choose 1 time to write the<br />

story.<br />

*make a list <strong>of</strong> first times <strong>and</strong> last times<br />

*make a list <strong>of</strong> all the things you wonder about<br />

Write from a noun. Have students choose any noun, put it at the top <strong>of</strong> a clean<br />

page, <strong>and</strong> write for 15 – 20 minutes. They should write anything that comes to<br />

mind. Tell them that it‘s ok to stray from the original noun. This is a good<br />

strategy to help writers get past writer‘s block. So, it‘s good to teach this at the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> the year, just-in-case it is needed by some later in the year.

Teach the importance <strong>of</strong> rereading the notebook right from the beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

year. Students will get new ideas from reading their old entries. Teach students<br />

to reread with a highlighter in their h<strong>and</strong>. Have them highlight any interesting<br />

lines, words, or ideas that they might want to write more about later.<br />

Lift a line – have students reread their notebooks <strong>and</strong> choose a line they want to<br />

write more about. They can put the line at the top <strong>of</strong> a clean page <strong>and</strong> continue<br />

from there. This helps them see that there can be more than one starting point<br />

for an idea.<br />

Choosing an Idea, Nurturing/Developing that Idea<br />

*You Collect ideas, then Choose a Seed Idea, <strong>and</strong> begin nurturing/developing that Seed<br />

Idea INSIDE <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Writing</strong> Notebook.<br />

Reread the notebook, putting a mark by all <strong>of</strong> the entries that could be<br />

possible seed ideas.<br />

Choose the one idea that holds enough memory to be developed into a full<br />

piece.<br />

Begin nurturing/developing that idea inside the notebook by using multiple<br />

strategies.<br />

Use a photograph from the time your writing about to help you think <strong>of</strong> more<br />

details to include<br />

Interview someone who was there to get another perspective <strong>and</strong> more details<br />

to add to your writing<br />

Sketch to help you remember all the tiny details<br />

Go to the place (if possible) <strong>and</strong> write everything you can about it<br />

Make a web<br />

Make a time-line<br />

Make a quick list <strong>of</strong> everything you can remember<br />

Try out different leads (beginnings)<br />

Make a list <strong>of</strong> words you know you want to use (try for exciting verbs <strong>and</strong><br />

adjectives/specific nouns)<br />

Write questions you have about the time you are writing about <strong>and</strong> try to<br />

answer them

Make a square <strong>and</strong> divide it into 4 boxes - use your senses as titles for each<br />

box - write using your senses<br />

Smell<br />

The smell <strong>of</strong> salt<br />

water filled my<br />

nose.<br />

Hear<br />

I could hear the<br />

waves crashing.<br />

Touch<br />

The rough s<strong>and</strong><br />

scraped the<br />

bottom <strong>of</strong> my<br />

feet.<br />

See<br />

Sea gulls were<br />

flying over my<br />

head.<br />

Write the bones <strong>of</strong> your story (just get it down without all the dialogue <strong>and</strong><br />

wonderful details)<br />

Think about the heart <strong>of</strong> your story (Where is the most action/emotion?) <strong>and</strong><br />

just write the heart in your notebook, stretching it out, writing it in slow motion<br />

Tell your story to someone<br />

Drafting <strong>and</strong> Revising<br />

―If we expect our students to revise, we must provide them with specific strategies<br />

with which to revise. We can teach <strong>and</strong> demonstrate specific revision strategies by<br />

modeling our own <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional writers‘ writing <strong>and</strong> revision processes <strong>and</strong> by<br />

teaching mini-lessons that include specific revision strategies.‖ (Georgia Heard, 2002 –<br />

The Revision Toolbox)<br />

The most effective way to teach these strategies is by modeling them with your writing<br />

or with a child‘s writing.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the following strategies were taken from the book, The Revision Toolbox.<br />

Students reread ALL entries about their idea, close their notebook, <strong>and</strong> begin<br />

drafting their story (skipping lines to save room for later revisions, not writing on<br />

the back).<br />

―Cracking Open Words <strong>and</strong> Phrases‖ – It was a nice day. = The sun peaked its head<br />

up from the edge <strong>of</strong> the earth <strong>and</strong> covered the house with warmth. I swung open<br />

the squeaky, white screen-door <strong>and</strong> stepped onto the porch. The cloudless blue<br />

sky was everywhere. I just knew the fish would be biting today.

―Verbs are the Engines <strong>of</strong> Sentences‖ – Have students check their piece <strong>and</strong><br />

change some tired verbs to more exciting verbs - I walked up the stairs. = I<br />

leaped up the stairs.<br />

―Nouns are the Wheels <strong>of</strong> Sentences‖ – Have students check their nouns <strong>and</strong><br />

change some to more specific - I pulled stuff out <strong>of</strong> my bag. = I pulled sticky gum<br />

wrappers, uncapped lipstick, <strong>and</strong> broken pretzels out <strong>of</strong> my bag.<br />

Change the Lead – Try starting with a Question: How will I ever tell my mom I<br />

broke the lamp? Or start with an Image: My feet crackled over the broken lamp<br />

pieces.<br />

Every time I moved, more crackling. Or start with Dialogue: ―Johnny! Hurry! I<br />

need your help. Mom is going to kill me!‖ Or start with Action – Crack. Crack.<br />

Crack. I tried not to look as I heard the lamp hit the tile floor.<br />

Find the Heart <strong>of</strong> the Piece – Choose one or two sentences that are what the<br />

piece is mostly about. Put those sentences at the top <strong>of</strong> a new page <strong>and</strong> just write<br />

about those sentences.<br />

Rereading – Teach kids to reread right from the start. Model writing a piece,<br />

stopping after every few sentences to reread. We want kids to always do this.<br />

Playing with time – Make a time-line <strong>of</strong> a piece <strong>and</strong> try starting the piece from<br />

different places on the time-line.<br />

Change the Point <strong>of</strong> View – Have students try writing their piece from a different<br />

perspective.

Below is a sample 5 day schedule (easily extended to make a 10 day schedule) for<br />

moving students through the writing process. It is ideal to move students through<br />

the writing process within the first 2 weeks <strong>of</strong> launching <strong>and</strong> actually publish a piece<br />

to share at the end. Then, you can start over <strong>and</strong> move through a 4 week narrative<br />

study <strong>and</strong> slow the process down. It is good for students to feel that sense <strong>of</strong><br />

accomplishment (publishing) quickly in the beginning <strong>of</strong> the year.<br />

Minilesson<br />

Workshop<br />

&<br />

Conferring<br />

Share<br />

Day 1 Day 2<br />

Day 3 Day 4 Day 5<br />

Collecting Revising Editing Management Publishing<br />

One way in<br />

which writers<br />

get ideas for<br />

their work<br />

Students write a<br />

small moment<br />

on paper,<br />

teacher confers<br />

to encourage<br />

One way in One way in<br />

which writers which<br />

revise their writers edit<br />

work their work<br />

Students Students<br />

revise their edit their<br />

work, teacher work,<br />

confers to teacher<br />

encourage confers to<br />

encourage<br />

One thing writers<br />

in our class need to<br />

know about<br />

management<br />

Students rewrite<br />

their work with<br />

their revisions <strong>and</strong><br />

corrections<br />

How writers<br />

celebrate their<br />

work<br />

Students<br />

celebrate their<br />

work as a class<br />

Whatever the teacher deems necessary. Students might share their work or the<br />

teacher may do some management work with them.<br />

The following might be great to write on chart paper or copy for the kids<br />

to keep:<br />

―I Am a Writer When…<br />

I am a writer when I sit alone <strong>and</strong> write down my favorite memories about my<br />

childhood <strong>and</strong> my children; when I take time to write by creating space in my<br />

life; when I wake up in the middle <strong>of</strong> the night <strong>and</strong> fish around to find a pen<br />

<strong>and</strong> paper to capture my thoughts.<br />

I am a writer when I write about things that matter to me most…my parents,<br />

family, special people, places, <strong>and</strong> things in my life; when I access childhood

memories; when I hear things I want to remember <strong>and</strong> take time to write<br />

them down.<br />

I am a writer when I capture thoughts, dreams, noticings, <strong>and</strong> wonderings in<br />

my writer‘s notebook; when I write as a means <strong>of</strong> expressing my emotions;<br />

when I write poetry that stems from my personal experiences.<br />

I am a writer when the words in my notebook float effortlessly <strong>of</strong>f the paper<br />

like a musical composition that lingers in my head; when I have time to really<br />

express my ideas <strong>and</strong> not have to share them with anyone; when I am given<br />

time to reflect upon my personal <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional life.<br />

I am a writer when the words I‘ve created bring me back to the me I should<br />

be; when I allow myself to relax <strong>and</strong> write whatever I am feeling, whatever I<br />

am frustrated by, whatever I am thinking, <strong>and</strong> when I am finished, I feel<br />

cleansed; when I pour out my heart through words.

September<br />

Literary Essay<br />

Overview <strong>of</strong> the Unit<br />

This unit aims to make reading a more intense, thoughtful experience for children<br />

<strong>and</strong> to equip them to write expository essays that advance an idea about a piece <strong>of</strong><br />

literature. In order to write about reading in this way, you will need to decide which<br />

piece(s) <strong>of</strong> literature your children will study in the unit. If your children are reading<br />

novels <strong>and</strong> talking about the deeper meanings <strong>of</strong> those novels in book clubs, you could<br />

use literary essays as a way to harvest their interpretations <strong>of</strong> these books.<br />

However, students can also write literary essays about a short story or picture<br />

book. Cynthia Rylant‘s book, Every Living Thing, has some wonderful examples you could<br />

use. Also, Ever Bunting‘s pictures books are provide excellent opportunities for literary<br />

essays. You can create a small collection <strong>of</strong> stories for students to read <strong>and</strong> respond to.<br />

Likewise, you could begin the unit with the entire class reading the same short<br />

text <strong>and</strong> responding to it in their notebooks. Then you could do a quick publish <strong>of</strong> this<br />

as a model for a more in depth literary essay about the book they are reading in<br />

reader‘s workshop. If you start your reader‘s <strong>and</strong> writer‘s workshop unit at the same<br />

time, doing a quick publish <strong>of</strong> a short text will <strong>of</strong>fer you time during reader‘s workshop<br />

to collect entries about the characters in their stories. By the time you have completed<br />

your quick publish, students will have completed work during reader‘s workshop about<br />

their characters. This will give them information <strong>and</strong> ideas to use during writer‘s<br />

workshop as they begin a more in-depth study <strong>of</strong> their character for their second<br />

literary essay.<br />

During the first few days <strong>of</strong> the unit, you will want to demonstrate a way <strong>of</strong><br />

reading <strong>and</strong> writing <strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> a story. Invite children to look closely at a text <strong>and</strong> to write,<br />

―I see..‖ <strong>and</strong> then write what they notice. Encourage them to write long about this,<br />

extending their observations by adding, ―The surprising thing about this is…, The<br />

important thing about this is…, The thought This gives me is…, or I wonder if…<br />

Once they have the short story/novel that they will write a literary essay for,<br />

they will collect entries about the text. The process <strong>of</strong> choosing a seed idea in this unit<br />

becomes double pronged. First, a child chooses a story. Then, the child lives wit that<br />

one story <strong>and</strong> gathers entries about it. Eventually, the child will also reread those<br />

entries to choose a seed idea – a claim- about their story.<br />

Remind students to observe their lives <strong>and</strong> create thought patches in their<br />

notebooks. They can use prompts like, ―The thought I have about this is… or This makes<br />

me realize that…‖ They can pause as they read to observe what is happening to a<br />

character <strong>and</strong> then grow an idea using the same sentence starters. They can also<br />

extend their thought patches by using thought prompts to grow their thinking. As<br />

students give examples to grow their thinking, remind them that they can linger on<br />

these ideas too. Teach them to record an idea using new words by saying, ―that is..‖ or

―in other words…‖ <strong>and</strong> then rephrasing the idea. Teach them to entertain possibilities<br />

by writing, ―could it be that…‖ or ―perhaps…‖ or ―some may say that..‖ Phrases like<br />

―furthermore…‖ , ―this connects with…‖, ―on the other h<strong>and</strong>…‖, ―but you might ask…‖,<br />

―this is true because…‖, or ―I am realizing that..‖ This will help them to elaborate upon<br />

their ideas. Growing these sorts <strong>of</strong> ideas will allow children to write literary essay that<br />

articulate the lessons they believe a character learns in a story or essays that name the<br />

theme/idea a text teaches.<br />

Children can look for a seed idea that is central to the story <strong>and</strong> provocative. You<br />

can help them generate possible seed ideas. Some children will benefit from writing<br />

inside this general structure: ―This is a story about… (someone), who is…(how?) at the<br />

start <strong>of</strong> the story, but then ends up…(how?).‖ It could also be written, ―This is a about<br />

___, who learns ___. Early in the text…Later in the text…‖ Some children will find<br />

success if they try writing a sentence or two in which they lay out what the character<br />

was like at the start <strong>of</strong> the story, contrasting this with how the character turned out at<br />

the end.<br />

Some children may want to write a thesis statement within this structure: ―When<br />

I first read…, I thought it was about (the external plot driven story) but now, rereading<br />

it, I realize it is about (the internal story).‖ This thesis would lead a writer to first<br />

write about the plot, the external story, <strong>and</strong> then write about the theme, or the under<br />

story.<br />

Children will need to revise their seed idea so that it is a clear thesis, making sure<br />

it is a claim or an idea, not a fact, phrase or a question. Help children to imagine how<br />

they can support the thesis in a few paragraphs. Each paragraph shows how the claim is<br />

true, citing specific reasons.<br />

Children will plan their essays using boxes <strong>and</strong> bullets. They will need to collect<br />

the information <strong>and</strong> insights needed to build the case. They can make a file for each<br />

topic sentence/supporting paragraph <strong>and</strong> collecting examples to support their reasons.<br />

On the other h<strong>and</strong>, children could bypass the process <strong>of</strong> gathering information into files<br />

by using a rough form <strong>of</strong> an outline. They can plan each part <strong>of</strong> their essay by labeling<br />

the top <strong>of</strong> separate pieces <strong>of</strong> drafting paper. Separate sheets <strong>of</strong> paper would be<br />

labeled introduction, reason/evidence 1, reason/evidence 2, reason/evidence 3, <strong>and</strong><br />

conclusion.<br />

You will need to teach writers how to cite references from a text <strong>and</strong> how to<br />

unpack these citations. You may want to teach children that writers <strong>of</strong> literary essays<br />

use literary terms such as narrator, point <strong>of</strong> view, <strong>and</strong> scenes.<br />

You may also want to teach students to write introductory paragraphs that<br />

include a tiny summary <strong>of</strong> the story. Closing paragraphs should link the story‘s message<br />

to the writer‘s own life – the ending is a good place for a Hallmark moment. ―This story<br />

teaches me that I, too…‖ An alternative is to link this story to another story or to an<br />

issue in the world.

Alignment to the St<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

5.3.3 Contrast the actions, motives, <strong>and</strong> appearances <strong>of</strong> characters in a work <strong>of</strong><br />

fiction <strong>and</strong> discuss the importance <strong>of</strong> the contrasts to the plot or theme.<br />

5.3.4 Underst<strong>and</strong>s that theme refers to the central idea or meaning <strong>of</strong> a selection<br />

<strong>and</strong> recognize themes, whether they are implied or stated directly.<br />

5.3.5 Describe the function <strong>and</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> common literary devices, such as imagery,<br />

metaphor, <strong>and</strong> symbolism.<br />

5.4.1 Discuss ideas for writing, keeping a list or notebook <strong>of</strong> ideas, <strong>and</strong> use graphic<br />

organizers to plan writing.<br />

5.4.3 Write informational pieces with multiple paragraphs that: present important<br />

ideas or events in sequence or in chronological order; provide details <strong>and</strong><br />

transitions to link paragraphs; <strong>of</strong>fer a concluding paragraph that summarizes<br />

important ideas <strong>and</strong> details.<br />

5.4.8 Review, evaluate, <strong>and</strong> revise writing for meaning <strong>and</strong> clarity.<br />

5.4.9 Pro<strong>of</strong>read one‘s own writing, as well as the writing <strong>of</strong> others, using an editing<br />

checklist or set or rules, with specific examples <strong>of</strong> corrections <strong>of</strong> specific<br />

errors.<br />

5.4.10 Edit <strong>and</strong> revise writing to improve meaning <strong>and</strong> focus through adding, deleting,<br />

combining, clarifying, <strong>and</strong> rearranging words <strong>and</strong> sentences.<br />

5.4.11 Use logical organizational structures for providing information in writing, such<br />

as chronological order, cause <strong>and</strong> effect, similarity <strong>and</strong> difference, <strong>and</strong> stating<br />

<strong>and</strong> supporting a hypothesis with data.<br />

5.5.2 Write responses to literature that: demonstrate an underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> a<br />

literary work; support statements with evidence from the text; develop<br />

interpretations that exhibit careful reading <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing.<br />

5.5.5 Use varied word choices to make writing interesting.<br />

5.5.6 Write for different purposes <strong>and</strong> to a specific audience or person, adjusting<br />

tone <strong>and</strong> style as appropriate.<br />

5.6.2 Use transitions <strong>and</strong> conjunctions to connect ideas.<br />

5.6.5 Use a colon to separate hours <strong>and</strong> minutes <strong>and</strong> to introduce a list; use<br />

quotation marks around the exact words <strong>of</strong> a speaker <strong>and</strong> titles <strong>of</strong> articles,<br />

poems, songs, short stories, <strong>and</strong> chapters in books; use semi-colons <strong>and</strong><br />

commas for transitions.<br />

5.6.6 Use correct capitalization.<br />

5.6.7 Spell roots or bases <strong>of</strong> words, prefixes, suffixes, contractions, <strong>and</strong> syllable<br />

constructions correctly.<br />

5.6.8 Use simple sentences <strong>and</strong> compound sentences in writing.<br />

5.7.11 Deliver oral responses to literature that: summarize important events <strong>and</strong><br />

details; demonstrate an underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> several ideas or images<br />

communicated by the literary work; use examples from the work to support<br />

conclusions.

6.3.2 Analyze the effect <strong>of</strong> the qualities <strong>of</strong> the character on the plot <strong>and</strong> the<br />

resolution <strong>of</strong> the conflict.<br />

6.3.3 Analyze the influence <strong>of</strong> the setting on the problem <strong>and</strong> its resolution.<br />

6.3.6 Identify <strong>and</strong> analyze features <strong>of</strong> themes conveyed through characters,<br />

actions, <strong>and</strong> images.<br />

6.3.7 Explain the effects <strong>of</strong> common literary devices, such as symbolism, imagery, or<br />

metaphor, in a variety <strong>of</strong> fictional <strong>and</strong> nonfictional texts.<br />

6.3.9 Identify the main problem or conflict <strong>of</strong> the plot <strong>and</strong> explain how it is<br />

resolved.<br />

6.4.1 Discuss ideas for writing, keep a list or notebook <strong>of</strong> ideas, <strong>and</strong> use graphic<br />

organizers to plan writing.<br />

6.4.2 Choose the form <strong>of</strong> writing that best suits the intended purpose.<br />

6.4.3 Write informational pieces <strong>of</strong> several paragraphs that: engage the interest <strong>of</strong><br />

the reader; state a clear purpose; develop the topic with supporting details<br />

<strong>and</strong> precise language; conclude with a detailed summary linked to the purpose<br />

<strong>of</strong> the composition.<br />

6.4.4 Use a variety <strong>of</strong> effective organizational patterns, including comparison <strong>and</strong><br />

contrast, organization by categories, <strong>and</strong> arrangement by order <strong>of</strong> importance<br />

or climatic order.<br />

6.4.8 Review, evaluate, <strong>and</strong> revise writing for meaning <strong>and</strong> clarity.<br />

6.4.9 Edit <strong>and</strong> pro<strong>of</strong>read one‘s own writing, as well as that <strong>of</strong> others, using an editing<br />

checklist or set or rules, with specific examples <strong>of</strong> corrections <strong>of</strong> frequent<br />

errors.<br />

6.4.10 Revise writing to improve the organization <strong>and</strong> consistency <strong>of</strong> ideas within <strong>and</strong><br />

between paragraphs.<br />

6.5.2 Write descriptions, explanations, comparison <strong>and</strong> contrast papers, <strong>and</strong> problem<br />

<strong>and</strong> solution essays that: state the thesis or purpose; explain the situation;<br />

organize the composition clearly; <strong>of</strong>fer evidence to support arguments <strong>and</strong><br />

conclusions.<br />

6.5.3 Write responses to literature that: develop an interpretation that shows<br />

careful reading, underst<strong>and</strong>ing, <strong>and</strong> insight; organize the interpretation around<br />

several clear ideas; support statements with evidence from the text.<br />

6.5.6 Use varied word choice.<br />

6.5.7 Write for different purposes <strong>and</strong> to a specific audience or person, adjusting<br />

tone <strong>and</strong> style as necessary.<br />

6.5.8 Write summaries that contain the main ideas <strong>of</strong> the reading selection <strong>and</strong> the<br />

most significant details.<br />

6.6.1 Use simple, compound, <strong>and</strong> complex sentences; use effective coordination <strong>and</strong><br />

subordination <strong>of</strong> ideas, including both main ideas <strong>and</strong> supporting ideas in single<br />

sentences, to express complete thoughts.<br />

6.6.3 Use colons after the salutation, semicolons to connect main clauses, <strong>and</strong><br />

commas before the conjunction in compound sentences.

6.6.4 Use correct capitalization.<br />

6.6.5 Spell correctly frequently misspelled words.<br />

6.6.12 Deliver oral responses to literature that: develop an interpretation that<br />

shows careful reading, underst<strong>and</strong>ing, <strong>and</strong> insight; organize the presentation<br />

around several clear ideas, premises, or images; develop <strong>and</strong> justify the<br />

interpretation through the use <strong>of</strong> examples from the text.<br />

Teaching Points for Literary Essay:<br />

For this unit, teaching points created <strong>and</strong> shared at our collaboration meetings<br />

have been compiled together. The following teaching points are divided into the<br />

different steps <strong>of</strong> the writing process. There are more teaching points listed for each<br />

step than will be used in your unit <strong>of</strong> study. As a result, read through <strong>and</strong> choose those<br />

teaching points that will work best for your classroom. Don‘t forget to use the Lucy<br />

Calkin‘s book about literary essays for specific examples <strong>and</strong> additional ideas.<br />

Immersion<br />

Writers read literary essays in partnerships or small groups that others have<br />

written. They jot down what they notice, share with the class, <strong>and</strong> create a chart<br />

<strong>of</strong> noticings for everyone to use.<br />

Writers reread examples <strong>of</strong> literary essays. They choose their favorite as a<br />

mentor essay.<br />

Collecting<br />

Writers use text that they are reading to collect ideas for their writing. They<br />

react to their text by say, ―I can‘t believe that…It surprises me that…‖<br />

Writers use empathy to collect ideas for their writing. They empathize with the<br />

character <strong>and</strong> say, ―I feel sorry for…I‘m angry that….I‘m happy for… I feel<br />

hopeful for…‖<br />

Writers use their reading to get ideas for their writing. They read a little bit,<br />

stopping, <strong>and</strong> thinking about a line. They write, ―This line makes me think about…‖<br />

or ―This line seems important because…‖<br />

Writers use details in their reading to get ideas for their writing. They think<br />

about the details we see <strong>and</strong> hear <strong>and</strong> our thoughts about those details. We<br />

write entries like: I see… The thought I have about this…(or I think) To add on…<br />

This reminds me <strong>of</strong>…. My idea is…<br />

Writers use images from their reading to get ideas for their writing. They pick<br />

out an image that makes them think <strong>and</strong> wonder. They read a little bit, stopping,<br />

<strong>and</strong> writing: This image makes me think about…This image seems important<br />

because…I‘m picturing ___ in my mind <strong>and</strong> I‘m thinking…

Writers use the character‘s actions in their reading to get ideas for their writing.<br />

They pay attention to how the character acts or what the character does. They<br />

think about how they would act or what they would do in a similar situation. They<br />

write: This part makes me think ___ is a good person because…If it were me, I<br />

would…I‘m really annoyed at ___ when he does this because…<br />

Writers use ideas about their character to collect ideas for their writing. They<br />

think about a character‘s traits, motivations, struggles, <strong>and</strong> changes.<br />

Writers use thought prompts to push our thinking about our reading <strong>and</strong> help us<br />

write longer <strong>and</strong> deeper about our first ideas. They write a thought, use a prompt<br />

to push their idea further, <strong>and</strong> they extend/revise it. (Thought prompts can be<br />

found in the Lucy Calkin‘s book on page 53 <strong>of</strong> the essay book.)<br />

Writers elaborate on their thoughts/theories about their character. They give<br />

examples <strong>of</strong> when this happened (in the beginning, middle, <strong>and</strong> end). They use the<br />

words for example <strong>and</strong> another example <strong>of</strong> this is…<br />

Writers find important ideas in stories. They reread their text <strong>and</strong> ask, ―What‘s<br />

the story all about?‖ They pinpoint the main idea <strong>of</strong> the story <strong>and</strong> write long<br />

about it. Writers use in-depth thought prompts to help them write long. Some<br />

prompts include the following: The thing that surprises me about this is…, This<br />

connects to…, This reminds me…, When I think about this part <strong>of</strong> the text, I<br />

think…, I wonder about this part <strong>of</strong> the text, I think…, I wonder about this part<br />

because…, I‘m realizing…, This whole story makes me think…, Some people<br />

think…but I think…, I used to think…But this text makes me think…, This is<br />

important because…, This fits with the whole text because…, On the other h<strong>and</strong>…,<br />

I think this because…, Also…, <strong>and</strong> However… (Refer to chart on page 79 in the<br />

Calkin‘s book has some too.)<br />

Writers find issues that connect to their own lives. They reread a text <strong>and</strong> ask,<br />

―How does this relate to things that have happened in my own life?‖ <strong>and</strong> ―Can this<br />

story help me with my issues?‖ Also, they read their notebook, looking for topics<br />

<strong>and</strong> themes that reoccur. They ask, ―Why does this entry matter to me? What<br />

does this reveal about me? <strong>and</strong> How does the text connect to my life?‖<br />

Writers get ideas for their writing from their character. They notice changes<br />

their character has gone through. They can ask, ―Have I changed how I think <strong>of</strong><br />

my character?‖ In their notebooks, they can write I used to think ___ was ___<br />

but now I realize…, In the beginning the character ___ but in the middle/end…,<br />

or The character seemed ___ at first, but now he‘s…<br />

Writers collect ideas for their writing. They summarize bits <strong>of</strong> the text. They<br />

tell about the main character <strong>and</strong> their traits <strong>and</strong> motivations. They can<br />

summarize an episode or a few examples that support a character trait.<br />

(Summarizing steps are on page 140 in the Calkin‘s book.)<br />

Choosing

Writers carefully choose a piece to write about. They ask themselves, ―Which do<br />

I have the most to say about? Which one matters the most to me? <strong>and</strong> Which<br />

one do I have at least 3 supporting examples for?‖<br />

Writers use their notebooks to find thesis statements. They read their entries,<br />

revising them to fit the whole text, <strong>and</strong> find supporting ideas using boxes <strong>and</strong><br />

bullets.<br />

Nurturing/Developing<br />

Writers revise their thesis statements <strong>and</strong> supporting details. They reread them<br />

<strong>and</strong> decide if the thesis statement will present problems or if it can truly be<br />

supported with the text. They ask themselves questions to help with their<br />

decision. (Refer to page 112 in the Calkin‘s book for a list <strong>of</strong> the questions.)<br />

Writers use their writing partner to help with the revision <strong>of</strong> their thesis<br />

statement <strong>and</strong>/or supporting details. They talk with their partner about their<br />

ideas <strong>and</strong> evidence <strong>and</strong> ask them for their thoughts or suggestions.<br />

Writers support their thesis statement. They make a timeline <strong>of</strong> events that<br />

occurred in the text that support the thesis statement.<br />

Writers structure their literary essay with boxes <strong>and</strong> bullets. They write a<br />

thesis that makes a claim or <strong>of</strong>fers <strong>and</strong> idea about the text in the box. Then<br />

each <strong>of</strong> their bullets represents a body paragraph that supports the thesis.<br />

Writers support their thesis statement. They find evidence from the text to<br />

support each <strong>of</strong> their ideas.<br />

Writers extend an idea or claim. They list times, places, or reasons to support it.<br />

Writers can make a thesis statement more memorable <strong>and</strong> powerful. They repeat<br />

it <strong>and</strong> then add a supporting idea from the list as evidence each time they create<br />

a new paragraph. For example:<br />

Gabriel is a lonely boy.<br />

* Gabriel is lonely when he eats his s<strong>and</strong>wich at school.<br />

* Gabriel is lonely when he sits on the stoop outside his house.<br />

* Gabriel is lonely when he walks the dark street.<br />

Writers polish their essay with their leads. They write leads that contain broad<br />

statements about literature, life, stories, or about the essay topic. They do this<br />

to prepare the reader for the thesis they want to prove <strong>and</strong> to put it into a<br />

context to be better understood. (Examples given in the Calkin‘s book on pages<br />

189 <strong>and</strong> 190.)<br />

Drafting<br />

Writers draft their literary essay on lined paper, skipping lines, <strong>and</strong> not writing on<br />

the back. They label the top <strong>of</strong> each sheet <strong>of</strong> paper. The sheets are labeled<br />

introduction, evidence 1, evidence 2, evidence 3, <strong>and</strong> conclusion. Having separate<br />

sheets allows us to reorder <strong>and</strong> rearrange our paragraphs as we draft <strong>and</strong> revise.<br />

Writers draft an introduction for their essay. They mention the title <strong>and</strong> author<br />

from the text they are writing about. They give a brief, angled retelling <strong>of</strong> the

story – telling only the significant parts <strong>of</strong> the story that pertain to their idea<br />

<strong>and</strong> gives the reader a general idea <strong>of</strong> what the story is about. They state the<br />

thesis.<br />

Writers think about the order <strong>of</strong> their supporting paragraphs. They consider<br />

ordering their paragraphs from the least powerful to the most powerful.<br />

Writers use a similar structure for writing each <strong>of</strong> their support paragraphs.<br />

Each paragraph includes a topic sentence. It also states the example(s) for<br />

support. Writers include thought prompts to help them say more (elaborate)<br />

about an idea. They explain how their example(s) prove the text part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

thesis.<br />

Writers draft a conclusion for their essay. They restate the thesis statement.<br />

They quickly remind the reader <strong>of</strong> the examples they gave to prove the thesis.<br />

They write a final wrap-up thought that touches on the whole essay <strong>and</strong> leaves<br />

the reader thinking. Writers can make a connection to their own life, to the<br />

world, or to another text.<br />

Writers consider how they want to end their essays. They think about how a text<br />

has impacted their thinking about their own lives, the world, or another text.<br />

Revising<br />

Writers revise their literary essay. They look at their ideas/supporting evidence<br />

<strong>and</strong> decide what goes together. They may rearrange sentences, paragraphs, or<br />

remove/add information to strengthen their argument. They may look to see that<br />

their evidence follows the sequence <strong>of</strong> the text – their first example from the<br />

beginning <strong>of</strong> the text <strong>and</strong> the last from the end.<br />

Writers think about transition words to connect each part <strong>of</strong> their essay. They<br />

use transitional words/phrases like: for example, another example, furthermore,<br />

In one <strong>of</strong> the first scenes, we see this.., On the other h<strong>and</strong>…, however, In<br />

addition, And yet, One reason/another reason, also, next, <strong>and</strong> although.<br />

Writers <strong>of</strong>ten refer to the text for support. They quote the text <strong>and</strong> explain<br />

how it relates to their idea. After they quote the text, they may comment on it<br />

by saying, ―This scene particularly shows us… or This part is significant because…‖<br />

Writers make our essays engage. They vary the way they begin their supporting<br />

paragraphs.<br />

Writers show how a text has moved them. They reread their writing <strong>and</strong><br />

comment on their thoughts or feelings about the idea <strong>of</strong> their essay. They can<br />

make statements like, ―After reading this book, I now think/feel…‖<br />

Writers analyze their writing. They ask themselves questions like: Does my<br />

writing make sense? Have I used strong examples? Does my evidence refer back<br />

to my thesis? Then they read their essay with their partner, asking the same<br />

questions <strong>and</strong> revising as needed.<br />

Editing

Writers edit their essays. They make sure what they read is on the page, not<br />

omitting words they meant to write.<br />

Writers edit their essays. They reread their essay to make sure their writing<br />

makes sense.<br />

Writers edit their essays. They make sure their punctuation follows grammar<br />

rules learned.<br />

Writers edit their essays. They reread their essay to make sure their<br />

information is grouped in a way that makes sense.<br />

Writers read their essays backwards looking for misspelled words to change or<br />

look up.

October/November<br />

<strong>Writing</strong> Fiction<br />

(Historical Fiction, Fantasy, <strong>and</strong> Science Fiction)<br />

Overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>Writing</strong> Fiction<br />

This unit also <strong>of</strong>fers a nice parallel to the reading unit at this time, where<br />

students are in class-wide genre studies in book clubs. For this round <strong>of</strong> fiction, you will<br />

teach your students to write the same kind <strong>of</strong> fiction that they are reading in their<br />

book clubs. By partnering this writing unit with the same genre in their reading work, we<br />

can provide students many opportunities to carry strengths from one discipline to<br />

another. For example, in their book clubs, students will be talking about important<br />

moments in their stories, moments that are windows into characters, moments <strong>of</strong> choice<br />

<strong>and</strong> change, moments when characters bump into social issues, historical conflicts,<br />

magical forces, or clues depending on the kinds <strong>of</strong> stories they are reading. The mind<br />

work <strong>of</strong> interpretation in book clubs is clearly tied to the work <strong>of</strong> putting forth a<br />

central meaning, not just retelling events, in writing. Then too, readers will notice<br />

moments when they have strong emotional responses to their books. During writing, they<br />

can create their own such moments. Of course this will mean that writers need to read<br />

with the eyes <strong>of</strong> insiders, attending to not only being moved, but also the craft moves<br />

the writer utilized in order to affect them.<br />

Trust that your students will make discoveries from their own reading. Some <strong>of</strong><br />

them may be better at talking about fantasy or science fiction than we are! Fantasy<br />

readers will notice how the authors <strong>of</strong> their books control time <strong>and</strong> they can then think<br />

about manipulating time in their own drafts through foreshadowing, flashbacks, <strong>and</strong><br />

dream sequences. No matter the genre, we will be deepening our knowledge in writing<br />

fiction.<br />

Teach Students to Build On What They Know As Readers <strong>and</strong> Writers:<br />

Lessons That Are Key to Any Genre<br />

In this unit, you can choose to lead a whole study class on one <strong>of</strong> the three fiction<br />

options. You will no doubt first want to look through this section, which builds upon the<br />

work <strong>of</strong> your first narrative units, earlier in the year, <strong>and</strong> list out the teaching points<br />

<strong>and</strong> unit bends that match <strong>and</strong> build on the strengths <strong>of</strong> your students. Then you will<br />

want to spend some time carefully reading the three options below, adding to your plan<br />

the points that will help your students craft within that specific genre.

One <strong>of</strong> the most exciting aspects <strong>of</strong> this unit is that our reading <strong>and</strong> writing units<br />

will perfectly align. Whichever genre our students are reading <strong>and</strong> discussing in their<br />

book clubs during reading workshop will be the same genre they are writing. It is also<br />

important to note that although the genre makes the unit feel fresh <strong>and</strong> engaging to our<br />

students, as teachers we know that at the heart <strong>of</strong> this unit is the reinforcement <strong>of</strong><br />

skillful narrative writing. Some lessons <strong>and</strong> methods for teaching the craft <strong>of</strong> story<br />

writing will be common to all the genres. You may want to look at where your children‘s<br />

writing falls on the narrative writing continuum <strong>and</strong> think about how independent they<br />

are in their use <strong>of</strong> the writing cycle to decide which <strong>of</strong> the following reminders you need<br />

to spend more time on, no matter which subgenre <strong>of</strong> fiction your students are<br />

practicing.<br />

To remind your young writers that they know a lot about stories based on their<br />

reading lives, you could set up partnerships or small groups to do a quick inquiry in which<br />

they chart qualities <strong>of</strong> fiction stories that they have enjoyed. They will no doubt list<br />

traits such as how the characters are likeable, have strong emotions <strong>and</strong> interesting<br />

relationships. Depending on what you‘ve taught them to notice <strong>and</strong> talk about in the<br />

books they are reading <strong>and</strong> how <strong>of</strong>ten they‘ve had opportunities for talk they might also<br />

say how sometimes characters are complicated, face tough problems, desire things <strong>and</strong><br />

sometimes teach us lessons. They‘ll sometimes mention that writers use dialogue, detail,<br />

<strong>and</strong> inner thinking <strong>and</strong> that they give details about place, people, <strong>and</strong> objects. Next,<br />

teach your students to look across this chart <strong>of</strong> writer‘s craft, <strong>and</strong> decide which <strong>of</strong><br />

those they want to tackle this time as they write fiction. Don‘t let them choose too<br />

many. They should choose a couple they already do, <strong>and</strong> add one or two they‘ll focus on in<br />

this story. This way, you are teaching your writers to set writing goals, <strong>and</strong> to imagine<br />

outgrowing themselves as writers.<br />

You may also remind students <strong>of</strong> what they‘ve already learned in fiction writing.<br />

Partners can review their writing process from writing fiction <strong>and</strong> make a quick plan<br />

about how this unit will progress for them. They might jot down how they started by<br />

developing a main character, particularly by describing what that character wants <strong>and</strong><br />

struggles with. They might recall they had multiple tries at creating timelines for their<br />

stories or told them in many ways across mini-books <strong>and</strong> began writing some <strong>of</strong> those<br />

scenes or moments that took place within a clear setting. They will remember how they<br />

used their notebook to develop their character <strong>and</strong> to reflect on the issues their<br />

character faced. They may have rehearsed their stories by telling them to a partner or<br />

through dramatic storytelling with a small group.<br />

You may also teach students to use their notebook <strong>and</strong> any charts in the room to<br />

come up with ideas for writing. In their notebooks are probably a lot <strong>of</strong> small personal<br />

moments. You can remind them that in fiction they can change the endings <strong>of</strong> these<br />

moments, or use characters <strong>and</strong> issues they have real experience with, in their fiction

stories. So they can look through their notebooks for possible ideas. Even in fantasy,<br />

science fiction, <strong>and</strong> historical fiction, the characters need to be interesting, <strong>and</strong> have<br />

visible relationships, desires, <strong>and</strong> struggles. Otherwise you end up with too much<br />

attention to the trappings <strong>of</strong> the genre, such as a historical or fantastical setting, <strong>and</strong><br />

characters that aren‘t compelling enough. By taking students on this walk through past<br />

learning you are not only gently reviewing important teaching, but you are also adding to<br />

their budding feelings <strong>of</strong> confidence. ―This may be a new genre for you,‖ you‘ll say to<br />

your students, ―but you already know so much about writing fiction.‖<br />

Our writers will no doubt be so enthralled with the idea <strong>of</strong> writing fiction—<br />

especially writing the genres <strong>of</strong> fiction they are reading—that they will immediately<br />

begin to write long <strong>and</strong> complex plots. You will no doubt want to bottle this excitement,<br />

<strong>and</strong> remind them <strong>of</strong> how their thoughtful, paced work during the first unit led them to<br />

uncover things they never expected. Remind students that they will be writing short<br />

stories, <strong>and</strong> that their stories need to begin <strong>and</strong> end within a short time frame, to have<br />

one central problem that needs to be solved <strong>and</strong> to involve just two or perhaps three<br />

compelling characters.<br />

Teach students they can rehearse ideas for their stories in their notebooks by<br />

writing some scenes <strong>and</strong> then trying them again in multiple ways. All through the unit,<br />

you will use your own writing to model how you rehearse, experiment <strong>and</strong> revise your<br />

ideas. Show how you use what you know about good storytelling to try to create a vivid<br />

setting, a character the reader knows intimately, <strong>and</strong> a problem we care about. Don‘t<br />

feel you have to be fantastic at the particular genre though, as students benefit from<br />

seeing their teacher learn <strong>and</strong> get better as a writer as well. This <strong>of</strong>ten gives them<br />

more confidence in taking on new writing tasks. While demonstrating your own writing<br />

during a mini-lesson you might say, ―You know, my first attempts at writing fantasy, have<br />

been really tough, but I am learning a lot as a writer, like I discovered that if I try out<br />

the same scene in multiple ways I almost always find the perfect one.‖<br />

Next, you may find it helpful to teach or review with students how to tell their<br />

story across a mini-book or storyboard before they draft out <strong>of</strong> their notebook. You<br />

may, for instance, start with 3 scenes, one where the characters are introduced, one<br />

where the problem becomes visible, <strong>and</strong> one where it is solved. That makes the story<br />

manageable, <strong>and</strong> they can draft those scenes or moments first. Naturally, some <strong>of</strong> these<br />

will develop into more than one moment. If you teach your students that each <strong>of</strong> these<br />

scenes needs a convincing setting, that there is a balance <strong>of</strong> dialogue, action, <strong>and</strong> inner<br />

thinking, so we can see both what the character does as well as feels, they‘ll make a<br />

good start on their stories <strong>and</strong> their drafts will develop story tension <strong>and</strong> strong<br />

characters right from the start.

Once your students have begun drafting, you can start teaching revision. Revision<br />

lessons could include going back to the first scene <strong>and</strong> introducing hints about the<br />

problem characters will face by showing some <strong>of</strong> what they want, or what may get in the<br />

way. You might demonstrate by saying, ―In my piece I want to start building tension<br />

right from the start, so I‘m going to go back <strong>and</strong> show what she is thinking as she<br />

watches all the other kids crowding around. Maybe she can think something like, ‗I have<br />

to do something about this, <strong>and</strong> I can‘t just do anything! But who would listen to me?‘ or<br />

maybe...‖ You can also teach students to revise the first scene to develop relationships<br />

more – showing who has power, for instance. Or they could revise to give more details<br />

about time or place in every scene, <strong>and</strong> how that changes. In the scene where the<br />

problem arises, you could teach them to revise to really elaborate how their character<br />

responds to trouble. Or to focus on vivid imagery, so that readers will see pictures as<br />

they read <strong>and</strong> remember them when they finish the story. Finally, students could revise<br />

by looking at mentor text <strong>and</strong> saying: ‗What‘s a part I like <strong>and</strong> why? What specifically<br />

did the author do that I could do too? Where could I try that in my piece?‖<br />

Fiction writing is also a great place to teach conventions. One <strong>of</strong> the things you<br />

can teach students is to pay attention to tense. You can, using your own writing as a<br />

model, try the first scene <strong>of</strong> your story in past tense versus present, <strong>and</strong> notice how the<br />

tone is different. Then show them how once you commit to a tense, you have to make<br />

your verb endings match this tense. You may choose to teach your students some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most common irregular verbs, the ones that turn up a lot in their writing, such as<br />

say/said, go/went, are/were, bring/brought, etc.<br />

You could teach your writers how to use short or long sentences to have a rapid,<br />

intense tone, or a more contemplative tone, <strong>and</strong> then you could show them how to<br />

punctuate some <strong>of</strong> those longer sentences. Teaching students first how to use commas<br />

in lists, ―In her bag she had a comb, a mirror, <strong>and</strong> a green stone.‖ <strong>and</strong> then how to<br />

elaborate those lists by describing the objects, ―In her bag she had a golden comb that<br />

had belonged to Princess Stargiver, a mirror that showed the future, <strong>and</strong> a green stone<br />

that made you invisible,‖ will show them how to exp<strong>and</strong> their powers at the sentence<br />

level.<br />

*The teaching points for each genre are specific for that genre. They do<br />

not contain all <strong>of</strong> the teaching points necessary to teach fiction. General<br />

teaching points for fiction can be found in the Lucy Calkins‘ book for<br />

writing fiction or in your resources from collaboration meetings.<br />

Alignment with the St<strong>and</strong>ards:<br />

5.4.1 Discuss ideas for writing, keep a list or notebook <strong>of</strong> ideas, <strong>and</strong> use graphic<br />

organizers to plan writing.

5.4.2 Write stories with multiple paragraphs that develop a situation or plot,<br />

describe the setting, <strong>and</strong> include an ending.<br />

5.4.8 Review, evaluate, <strong>and</strong> revise writing for meaning <strong>and</strong> clarity.<br />

5.4.9 Pro<strong>of</strong>read one‘s own writing, as well as that <strong>of</strong> others, using an editing<br />

checklist or set <strong>of</strong> rules, with specific examples <strong>of</strong> corrections with specific<br />

errors.<br />

5.4.10 Edit <strong>and</strong> revise writing to improve meaning <strong>and</strong> focus through adding, deleting,<br />

combining, clarifying, <strong>and</strong> rearranging words <strong>and</strong> sentences.<br />

5.5.1 Write narratives that: establish a plot/point <strong>of</strong><br />

view/setting/conflict <strong>and</strong> show, rather than tell, the events <strong>of</strong> the story<br />

5.5.5 Use varied word choices to make writing interesting.<br />

5.5.6 Write for different purposes <strong>and</strong> to a specific audience or person, adjusting<br />

tone <strong>and</strong> style as appropriate.<br />

5.6.5 Use a colon to separate hours <strong>and</strong> minutes <strong>and</strong> to introduce a list;<br />

use quotation marks around the exact words <strong>of</strong> a speaker <strong>and</strong><br />

titles <strong>of</strong> articles, poems, songs, short stories, <strong>and</strong> chapters in books; use<br />

semi-colons <strong>and</strong> commas for transitions.<br />

5.6.6 Use correct capitalization.<br />

5.6.7 Spell roots or bases <strong>of</strong> words, prefixes, suffixes, contractions, <strong>and</strong> syllable<br />

constructions correctly.<br />

5.6.8 Use simple sentences <strong>and</strong> compound sentences in writing.<br />

5.6.9 Identify <strong>and</strong> correctly use appropriate tense for verbs that are <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

misused.<br />

5.7.9 Deliver narrative (story) presentations that: establish a<br />

situation/plot/point <strong>of</strong> view/setting with descriptive word/phrases <strong>and</strong><br />

show, rather than tell, the listener what happens<br />

6.4.1 Discuss ideas for writing, keep a list or notebook <strong>of</strong> ideas, <strong>and</strong> use graphic<br />

organizers to plan writing.<br />

6.4.8 Review, evaluate, <strong>and</strong> revise writing for meaning <strong>and</strong> clarity.<br />

6.4.9 Edit <strong>and</strong> pro<strong>of</strong>read one‘s own writing, as well as that <strong>of</strong> others, using <strong>and</strong><br />

editing checklist or set <strong>of</strong> rules, with specific examples <strong>of</strong> corrections <strong>of</strong><br />

frequent errors.<br />

6.4.10 Revise writing to improve the organization <strong>and</strong> consistency <strong>of</strong> ideas within <strong>and</strong><br />

between paragraphs.<br />

6.5.1 Write narratives that: establish <strong>and</strong> develop a plot <strong>and</strong> setting <strong>and</strong> present a<br />

point <strong>of</strong> view that is appropriate to the stories; include sensory details <strong>and</strong><br />

clear language to develop plot <strong>and</strong> character; use a range <strong>of</strong> narrative devices,<br />

such as dialogue or suspense.<br />

6.5.6 Use varied word choices to make writing interesting.<br />

6.5.7 Write for different purposes <strong>and</strong> to a specific audience or person, adjusting<br />

tone <strong>and</strong> style as necessary.

6.6.1 Use simple, compound, <strong>and</strong> complex sentences; use effective coordination <strong>and</strong><br />

subordination <strong>of</strong> ideas, including both main ideas <strong>and</strong> supporting ideas in single<br />

sentences, to express complete thoughts.<br />

6.6.2 Identify <strong>and</strong> properly us indefinite pronouns, present perfect, <strong>and</strong> future<br />

perfect verb tenses; ensure that verbs agree with compound subjects.<br />

6.6.3 Use colons after the salutation, semicolons to connect main clauses, <strong>and</strong><br />

commas before the conjunction in compound sentences.<br />

6.6.4 Use correct capitalization.<br />

6.6.5 Spell correctly frequently misspelled words.<br />

6.7.10 Deliver narrative presentations that: establish a context, plot, <strong>and</strong> point <strong>of</strong><br />